Building BC

Economic

Development Element

04

I. Introduction

According to the 2019 Brown County Workforce Profile, through November 2019 Brown

County had experienced over 120 months of economic expansion, dating back to 2007

1

.

Even with the 2008 economic downturn and home sales declining, Brown County economic

conditions remained relatively stable

2

. The 2019 Brown County Workforce Profile indicated

that job numbers were still climbing, and that the primary long-term challenge for Wisconsin’s

economic future is its workforce quantity. Brown County has fared better than many other

Wisconsin counties, led by a diverse manufacturing sector, but will also need to be able to

adapt, and especially to connect workers with the evolving education and skills to secure

future opportunities.

Economic development is the process by which a community organizes and then applies its

energies to the task of creating the type of business climate that will foster the retention and

expansion of existing businesses, attract new businesses, develop new business ventures, and

revitalize underutilized assets. Economic development efforts to create jobs are important

beyond generating additional income for the county residents. These efforts can help to

generate additional tax base for the provisions of local services and assist in establishing an

environment for long-term economic vitality.

Success in economic development today requires a significant change in how economic

development is done. Communities have come to realize that it is critically important to

retain and attract smart, talented, entrepreneurial people who can create employment

opportunities. Also, more people understand that a community and region’s physical and

cultural amenities are critical to attracting and retaining entrepreneurs. Creating

communities that foster sustainable economic growth will come only through partnerships

and collaboration among government, businesses, and nonprofit organizations. Finally, a

community cannot fully realize its economic potential without a shared prosperity for all.

Shared prosperity is a hallmark of a competitive economy, because an economy cannot

compete globally if it doesn’t strengthen its own workforce

3

. Shared prosperity allows

workers to invest in their families, their communities, and in new entrepreneurial opportunities.

Wisconsin and Brown County have experienced significant economic changes over the last decade. The

first started with the housing market collapse and economic crisis of 2008, the subsequent recovery through

the middle to the end of the decade, and the uncertainty and difficult economic conditions brought on by

the novel coronavirus pandemic.

Building BC 4-2

Economic Development Goals

Goal I. Continue to strengthen the connection between creating livable communities and

economic development to attract and support entrepreneurial talent.

Objective 1. Partner with other local entities to develop the region’s brand and showcase the area’s

strengths and attributes, specifically the six target industries for growth opportunity.

Objective 2. Continue to promote community livability concepts and tie them to a broader economic

development approach.

Objective 3. Continue to encourage local communities to ensure visually attractive commercial and

industrial building designs with high-quality materials, and site layouts with easy access to amenities.

Goal II. Ensure that Brown County is well-positioned to support future changes and trends in

industry and business to strengthen its economy.

Objective 1. Continue to work and partner with other local organizations, industries, and governments to

assess future trends and identify future business needs.

Objective 2. Coordinate with educational partners to address industry needs, specifically with the Brown

County STEM Innovation Center on the UW-Green Bay campus.

Objective 3. Identify partnerships and opportunities to help connect local industries and agriculture with

new technology to diversify agricultural products to new and expanding markets.

Objective 4. Continue working to ensure that Brown County has the necessary communications and digital

infrastructure to cultivate technological innovation.

Objective 5. Work with economic development and educational partners to continue to establish business

accelerator and incubator facilities.

Goal III. Build local community partnerships in Brown County to broaden and strengthen the

County’s tax base.

Objective 1. Explore the possibility of intercommunity revenue sharing to encourage economic

development cooperation between units of government.

Objective 2. Use the future land use map to prioritize and coordinate future business and industrial

development.

II. Goals and Objectives

Building BC 4-3

Labor Force Analysis

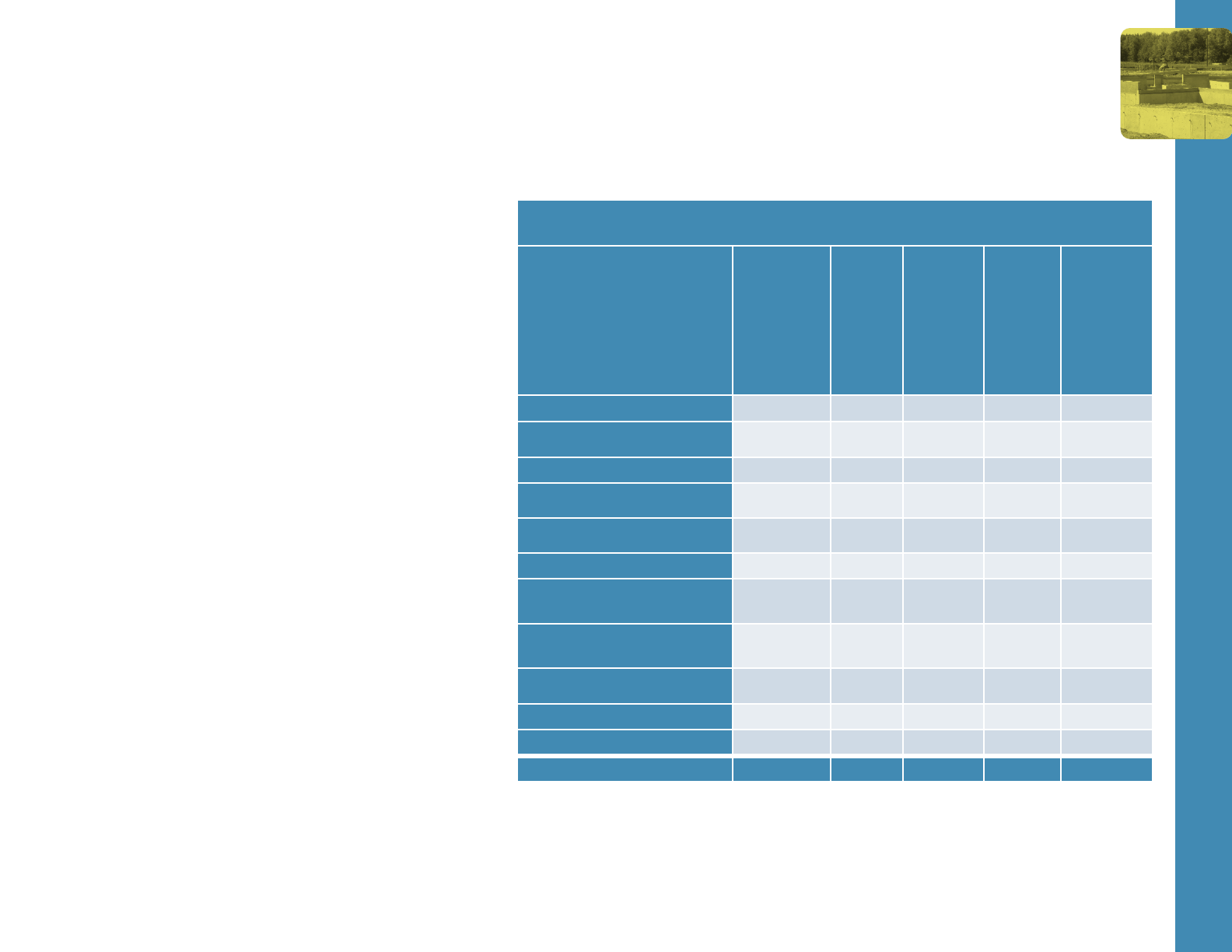

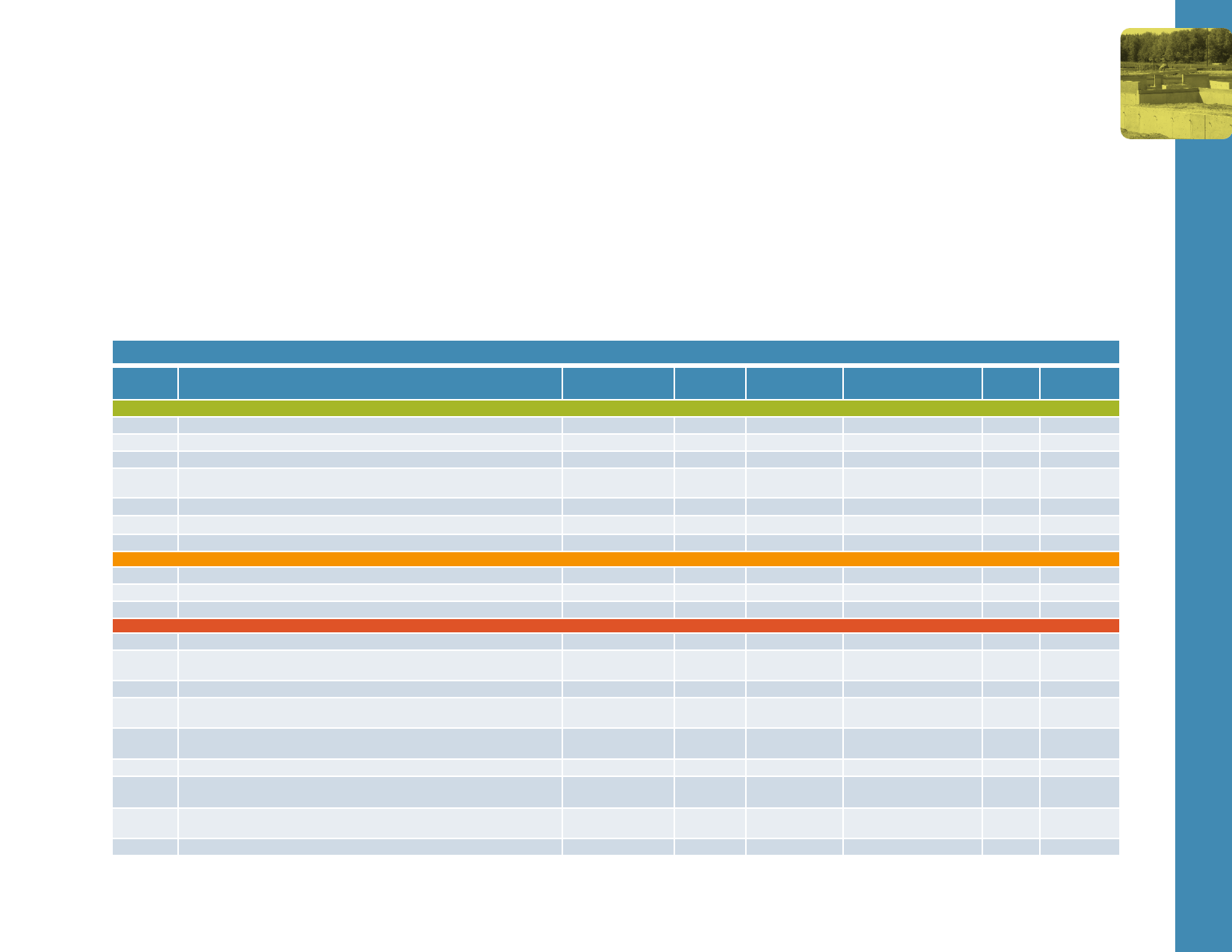

Figure 4-1 compares 2010 – 2018 labor force percentages

in Wisconsin and Brown County. While labor force totals

have continued to increase, the labor force percentage

relative to the general population has decreased.

Economists and demographers have attributed this to

greater numbers leaving the workforce than are being

replaced by new workers and indicates an aging state

population

4

. The Wisconsin Department of Workforce

Development’s 2019 Workforce Profile notes that labor

force participation rates for workers over 55 years of age

have risen significantly, and for whatever reasons people

might have to remain, this has helped hold off more

severe worker shortages.

Through 2018 local employers were having trouble filling

positions

5

because of low unemployment, and right up

until the novel coronavirus outbreak spread across the

U.S., the unemployment rate across the country was at a

historic low

6

.

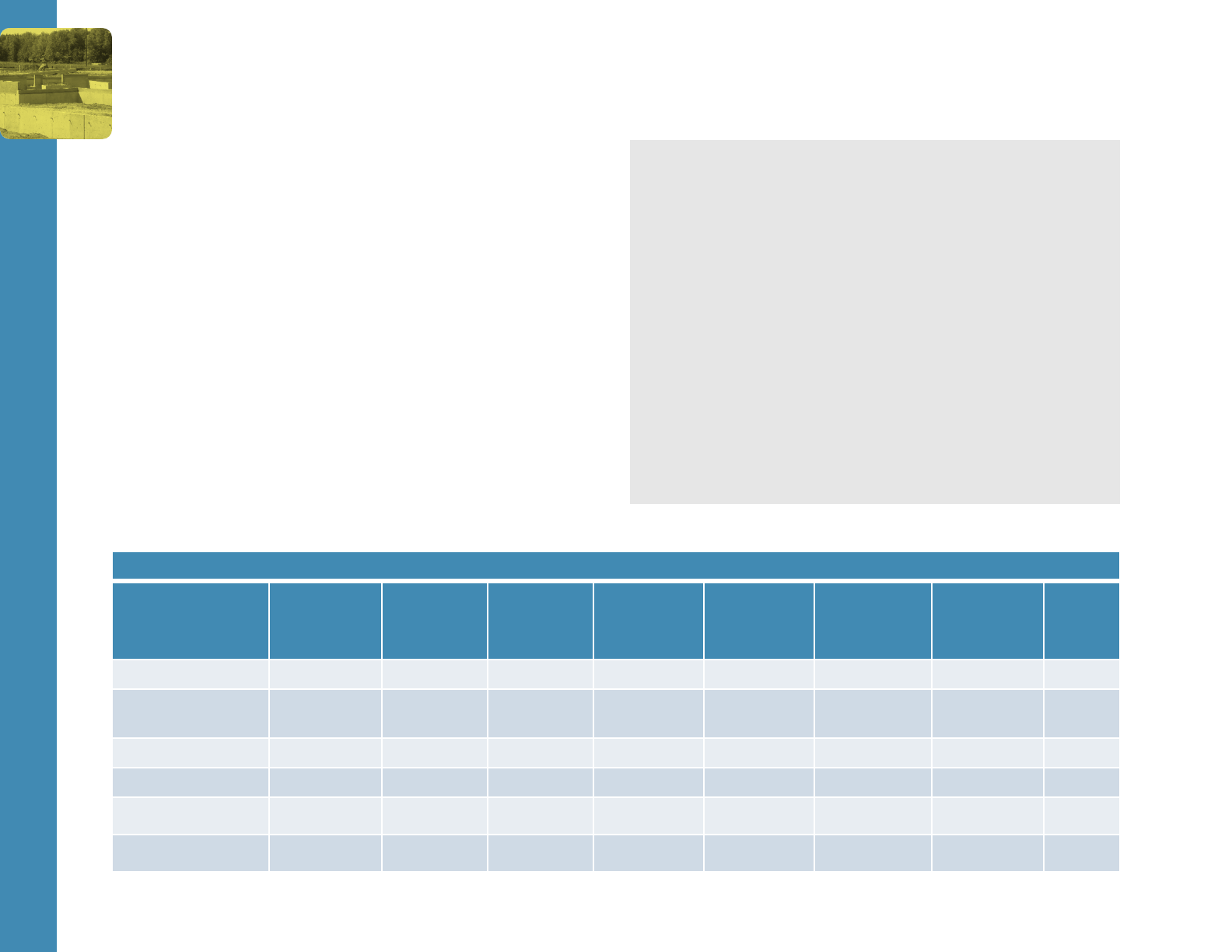

III. Existing Economic Conditions

Figure 4-1: Employment Status by Percentage of Population 16 Years and Above

Status

2010 WI

Population

2010 WI

Population

%

2018 WI

Population

2018 WI

Population

%

2010 Brown

County

Population

2010 Brown

County %

2018 Brown

County

Population

2018

Brown

County

%

In labor force 3,081,674 68.3% 3,096,515 66.0% 134,010 69.2% 141,160 67.9%

Civilian labor

force

3,081,674 68.3% 3,091,944 65.9% 133,623 69.0% 141,160 67.9%

Employed 2,806,444 62.2% 2,993,716 63.8% 124,287 63.2% 138,055 66.4%

Unemployed 275,230 6.1% 98,228 2.1% 16,267 5.8% 3,105 1.5%

Armed Forces 4,511 0.1% 4,571 0.1% 194 0.1% 0 0.0%

Not in labor force 1,430,293 31.7% 1,596,983 34.0% 59,646 30.8% 66,813 32.1%

Source: 2010 and 2018 U.S. Census American Community Surveys (ACS) 1-Year Estimates

Covid-19 and the Economy

This chapter has been drafted during the novel

coronavirus pandemic, which has dramatically altered

economic conditions in Brown County, Wisconsin, and

the U.S. However, annual data through 2018-2019 is still

the most current available and will be presented here,

recognizing that economic conditions will probably

change, and in ways not fully realized yet.

This chapter will outline some possible future economic

and industry trends that might happen during or

following the recovery or were already happening.

Since experts do not anticipate a “return to normal”

until after a vaccine is widely available, this chapter will

avoid any specific timelines and expectations, or any

sort of analysis around the pandemic’s impact.

Building BC 4-4

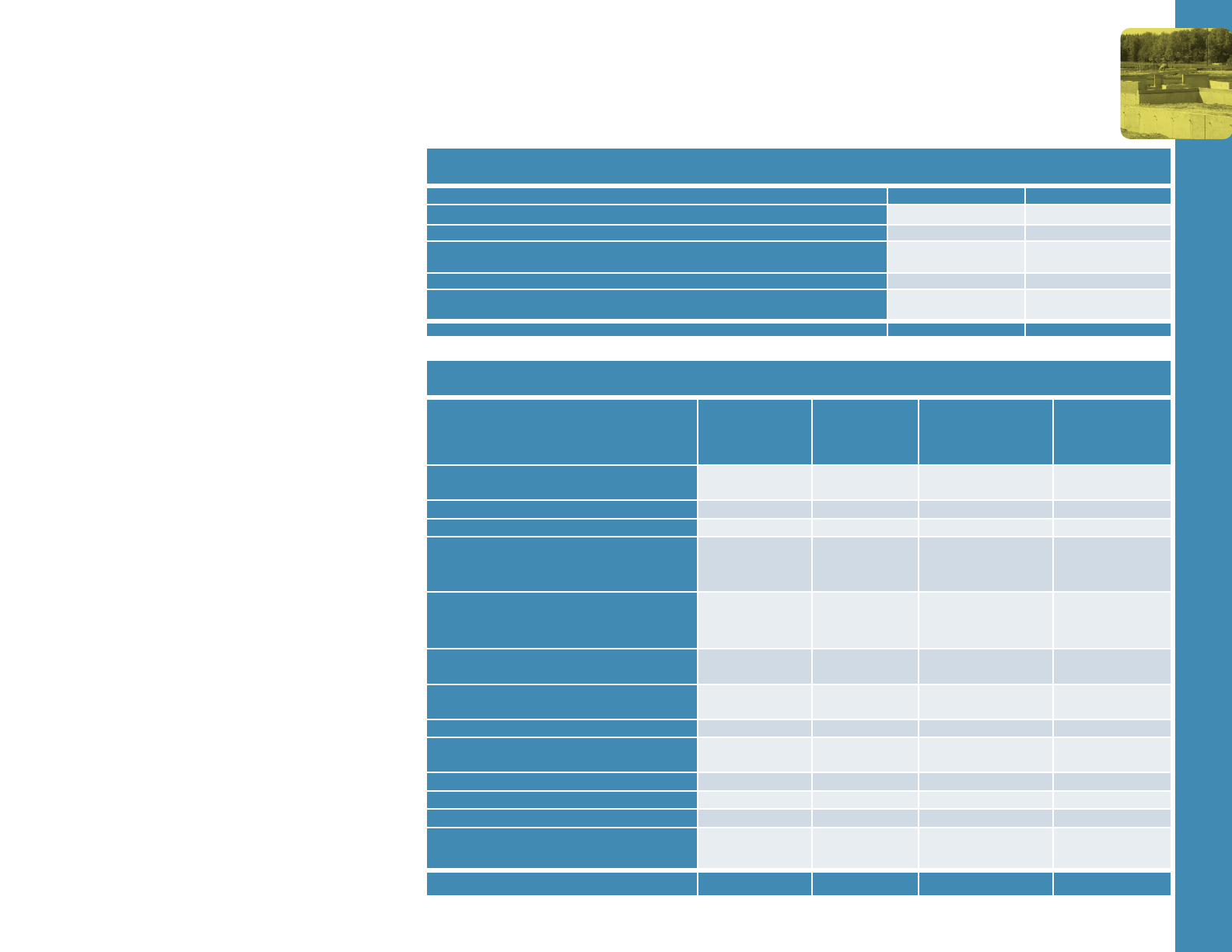

Figures 4-2 and 4-3 identify the

occupations and employment

categories for people 16 years and

older in Brown County and

Wisconsin. The largest industry

sector is educational, health, and

social services, reflecting Brown

County’s identity as a hub for

education and health-related

institutions. Manufacturing has

long been a mainstay in Brown

County’s economy and based on

the data in Figure 4-3,

manufacturing continues to be a

major employment sector with

16.3% of Brown County’s

population employed in it.

Brown County and the State of

Wisconsin are generally

comparable in terms of industry

employment. Educational

services, health care, and social

assistance have increased in both

the state and Brown County.

However, in the transportation and

warehousing and utilities sector,

Brown County businesses employ a

higher percentage of the

workforce, and that has increased

more in Brown County compared

to the state. Brown County has

seen a decrease in public

administration, information, and

agriculture/natural resources jobs.

III. Existing Economic Conditions

Figure 4-3: Employed Civilian Population 16 Years and Above as a Percentage by Industry Sector

Industry

2010 Wisconsin

Percentage of

Total

2018 Wisconsin

Percentage of

Total

2010 Brown

County

Percentage of

Total

2018 Brown

County

Percentage of

Total

Educational services, and health care

and social assistance

23.0% 23.7% 21.3%

22.4%

Manufacturing

17.9% 18.3% 18.2%

16.3%

Retail trade

11.6% 10.8% 11.4%

10.8%

Arts, entertainment, and recreation,

and accommodation and food

services

9.1% 8.2% 10.5%

9.6%

Professional, scientific, and

management, and administrative and

waste management services

7.9% 8.4% 7.5%

8.7%

Finance and insurance, and real estate

and rental and leasing

6.1% 6.0% 7.6%

7.1%

Transportation and warehousing, and

utilities

4.4% 4.8% 5.5%

6.4%

Construction

5.4% 5.9% 4.3%

5.2%

Other services, except public

administration

4.0% 4.2% 2.7%

4.4%

Wholesale trade

2.9% 2.5% 3.3%

3.4%

Public administration

3.6% 3.4% 3.6%

2.9%

Information

1.7% 1.6% 2.3%

1.9%

Agriculture, forestry, fishing and

hunting, and mining

2.5% 2.2% 1.7%

0.9%

Total 100% 100% 100% 100%

Source: 2010 and 2018 U.S. Census American Community Surveys (ACS)

Figure 4-2: Employed Civilian Population as a Percentage of People 16 Years and Above

Occupation

Wisconsin Brown County

Management, business, science, and arts occupations

36.1%

35.3%

Sales and office occupations 21.0%

22.7%

Production, transportation, and material moving occupations

17.7%

17.9%

Service occupations 16.7%

15.9%

Natural resources, construction, and maintenance occupations

8.5%

8.2%

Total 100% 100%

Source: 2010 and 2018 U.S. Census American Community Surveys (ACS)

Building BC 4-5

Economic Base Analysis

Brown County’s employer diversity is reflected in the listing of

the 30 largest private employers in the county, compiled by

the Greater Green Bay Chamber. Key industry groups in Brown

County include healthcare; paper and related products;

insurance, financial services, and government offices;

hospitality; food processing; and logistics (trucking,

warehousing, and related services). Figure 4-4 identifies the 30

largest employers in Brown County.

III. Existing Economic Conditions

Figure 4-4: 30 Largest Private Employers in Brown County, 2019

Company Type of Business Employees

1. Bellin Health Acute care hospital specializing in

cardio, neuro, and critical care

3,140

2. Humana Health insurance and related services 2,846

3. Oneida Nation Tribal enterprise and government of

the Oneida Tribe of Indians

2,789

4. Schneider One of the nation’s largest truck load

carriers

2,626

5. Aurora Health Care Full-service medical care facility 2,470

6. Georgia-Pacific Multinational manufacturer of paper

and tissue products

1,937

7. United Healthcare Markets and administers health and

life insurance plans

1,823

8. HSHS St. Vincent Hospital Acute care hospital and regional

center

1,668

9. American Foods Group Meat distributors 1,592

10. Prevea Health Regional health care provider 1,299

11. JBS Green Bay Beef slaughterer and processor 1,238

12. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. Retail shopping store chain 1,232

13. Green Bay Packaging,

Inc.

Corrugated and solid fiber box

manufacturing

1,187

Source: 2019 Greater Green Bay Fact Book

14. Associated Banc-Corp. Diversified bank holding

company

1,185

15. Festival Foods Grocery chain operating 32

grocery stores

1,102

16. Wisconsin Public Service An electric and natural gas

utility company serving NE

and Central WI

930

17. Ameriprise Auto & Home

Ins.

Personal lines property

casualty company

846

18. KI Manufacturer of contract

furniture

840

19. Belmark, Inc. Manufacturer of packaging 812

20. Schreiber Foods Manufacturer and marketer

of processed and natural

cheeses and dairy

750

21. Paper Converting

Machine Co.

Manufacturer of paper

converting machinery

700

22. Procter & Gamble Paper Paper products

manufacturer

593

23. RR Donnelly Printing, mailing, and direct

mailing services

575

24. St. Norbert College Private religious,

educational institution

554

25. Nsight & Cellcom Wireless

telecommunications carriers

551

26. Nature’s Way Medicinal and botanical

manufacturing; herbal

supplements

503

27. Tweet-Garot

Mechanical, Inc.

Mechanical contractor 468

28. ProAmpac Flexible packaging

producer

452

29. Salm Partners Cooked meats made from

purchased meats

450

30. HSHS St. Mary’s Hospital

Medical Center

Acute care hospital 432

Total 37,590

Building BC 4-6

III. Existing Economic Conditions

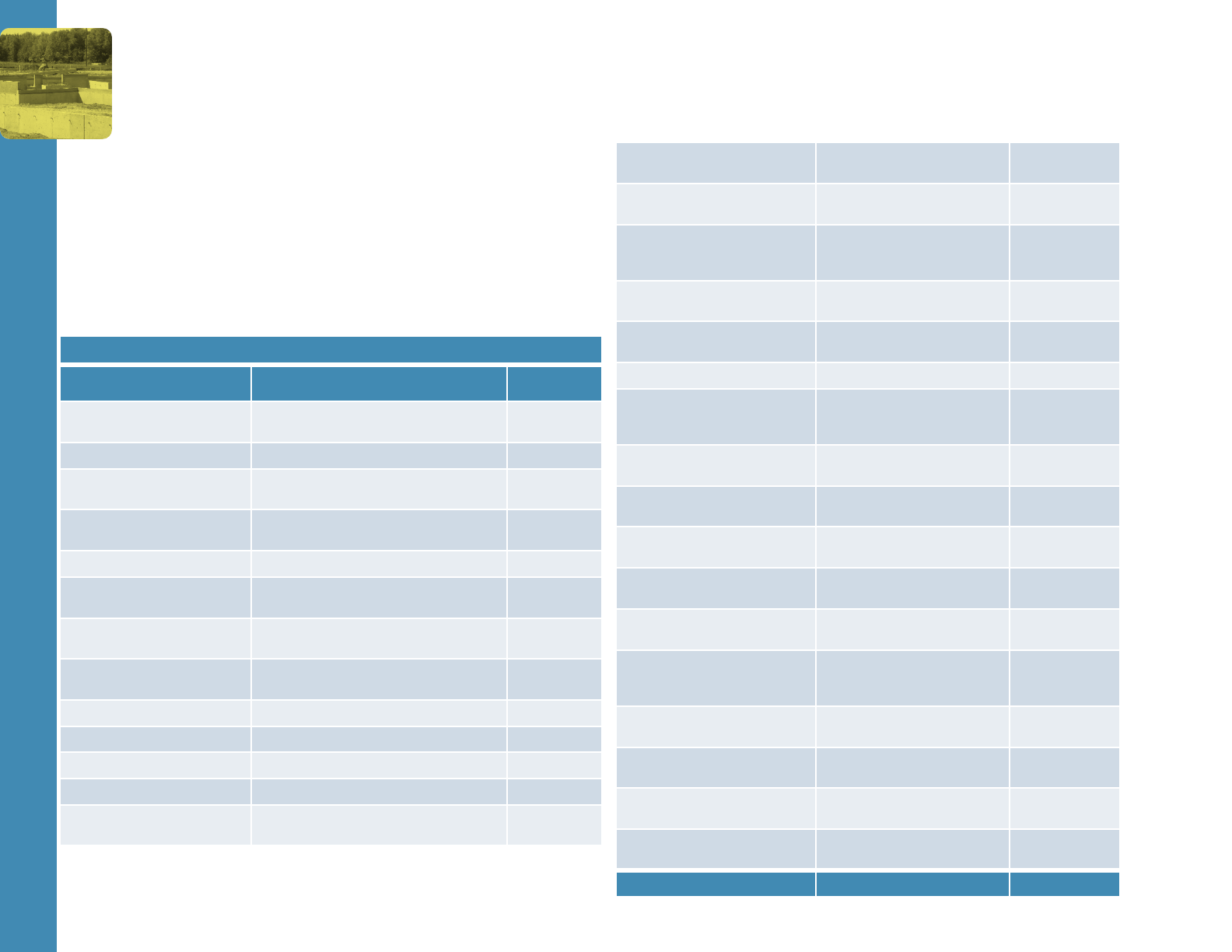

Figure 4-5 identifies the annual average

employment and wage by industry division

for Brown County in 2019. The

manufacturing, trade, transportation, and

utilities, and education and health services

industries comprised the three largest

divisions in Brown County with a total of

82,842 employees, comprising more than

half of the county’s workforce. Two of

these divisions (trade, transportation and

utilities; education and health services)

have generally higher average wages in

Brown County than the state. However,

the trade, transportation, and utilities

industry has one of the lower annual

average wages when compared to the

other industry sectors. Financial activities

has the highest annual average wage in

Brown County at $65,856, as compared to

information activities, which has the

highest annual average wage in the state

at $82,514. All divisions saw increases in

annual average wages between 2015 to

2019, with the largest increases in natural

resources and mining, leisure and

hospitality, and financial activities.

In general, wages are comparable to the

state as a whole, except for the leisure and

hospitality industry division, which is

significantly higher in Brown County

because of the wages associated with the

Green Bay Packers football team.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics QCEW

Figure 4-5: 2019 Brown County Annual Average Wage by High-level Industry

Annual

Average

Employment

Brown

County

Average

Annual

Wage

Wisconsin

Annual

Average

Wage

2019 BC %

of

Wisconsin

Wages

Brown

County

Change in

Annual

Average

Wage, 2015-

2019

Natural resources and mining

992 $40,251 $40,228

100.1% 20.9%

Construction

7,006 $60,780 $63,887

95.1% 9.6%

Manufacturing

27,304 $56,142 $59,083

95.0% 7.9%

Trade, transportation, and

utilities 31,002 $43,777 $42,645

102.7% 13.3%

Information

1,443 $58,908 $82,514

71.4% 12.8%

Financial activities

11,459 $65,856 $74,066

88.9% 14.6%

Professional and business

services

18,442 $64,084 $63,190

101.4% 6.2%

Education and health services

24,536 $54,669 $50,957

107.3% 5.1%

Leisure and hospitality

15,332 $32,187 $18,759

171.6% 22.6%

Other services

4,280 $25,418 $31,906

79.7% 13.7%

Public Administration

3,477 $49,179 $45,330

108.5% 12.6%

All Industries

141,796 $51,630 $50,525

102.2% 9.7%

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment and Wages from Occupational Employment Statistics

(OES) Survey, 2015 and 2019.

Building BC 4-7

Industry Clusters and Location Quotient Analysis

Industry clustering is an important idea for regional

economic development, and happens when different firms,

specialized suppliers, and service industries from

interconnected companies are located near each other or

concentrated in a region

7

.

Regional economies depend on how well they develop

specialized high-value industries, and then how those

specializations grow over time. Industry clustering helps firms

increase productivity through three key factors:

1. Sharing specialized facilities, infrastructure, and suppliers;

2. Matching workers through a robust labor pool; and

3. Learning accrued industry knowledge through the area’s

clus

tered professional networks

8

.

One method to potentially identify industry clusters is through

using a location quotient analysis. Computing the location

quotient of a given economic activity helps determine

whether that activity is a basic or non-basic employment

sector.

The location quotient analysis compares the local economy

to the United States and identifies basic and non-basic

sectors of the local economy. If the location quotient (LQ) is

less than 1.0, all employment is considered non-basic, which

means that local industry is not meeting local demand for

certain goods or services and may be more subject to

downturns in the local economy. An LQ equal to 1.0

suggests that the local economy is exactly sufficient to meet

the local demand for given goods or services. However, the

employment is still considered to be non-basic. An LQ of

greater than 1.0 suggests that the local employment industry

produces more goods and services than the local economy

can consume, and therefore, these goods and services are

exported to non-local areas and are basic sector

employment.

Basic sector employment typically produces goods or

services that are exported out of the local economy and

into the larger national economy. These goods, services

and employment are thus less likely to be affected by a

downturn in the local economy. For occupations that

provide services, such as healthcare, the “export” in this

instance may be the patient that lives somewhere else and

travels to Green Bay for an appointment or procedure. Non-

basic sector employment includes industries that produce

goods or services consumed at the local level or are not

produced at a sufficient level to be exported out of the

local market.

Harvard business economist Michael Porter has put forth an

increasingly popular method for using LQs to identify

possible industry clusters. In addition to looking at the

industry LQ, the LQ trend over time is considered

9

. Graphing

the industries can show whether they are basic or non-basic,

and whether over time they are growing or declining. This

information is more insightful when the individual industry

sector’s local employment proportion is considered . An

increase or decrease of a small employment sector may not

be cause for concern. A larger employment share could

mean that the industry represents a cluster that should be

nurtured, or that it is in decline and warrants further

monitoring and action.

III. Existing Economic Conditions

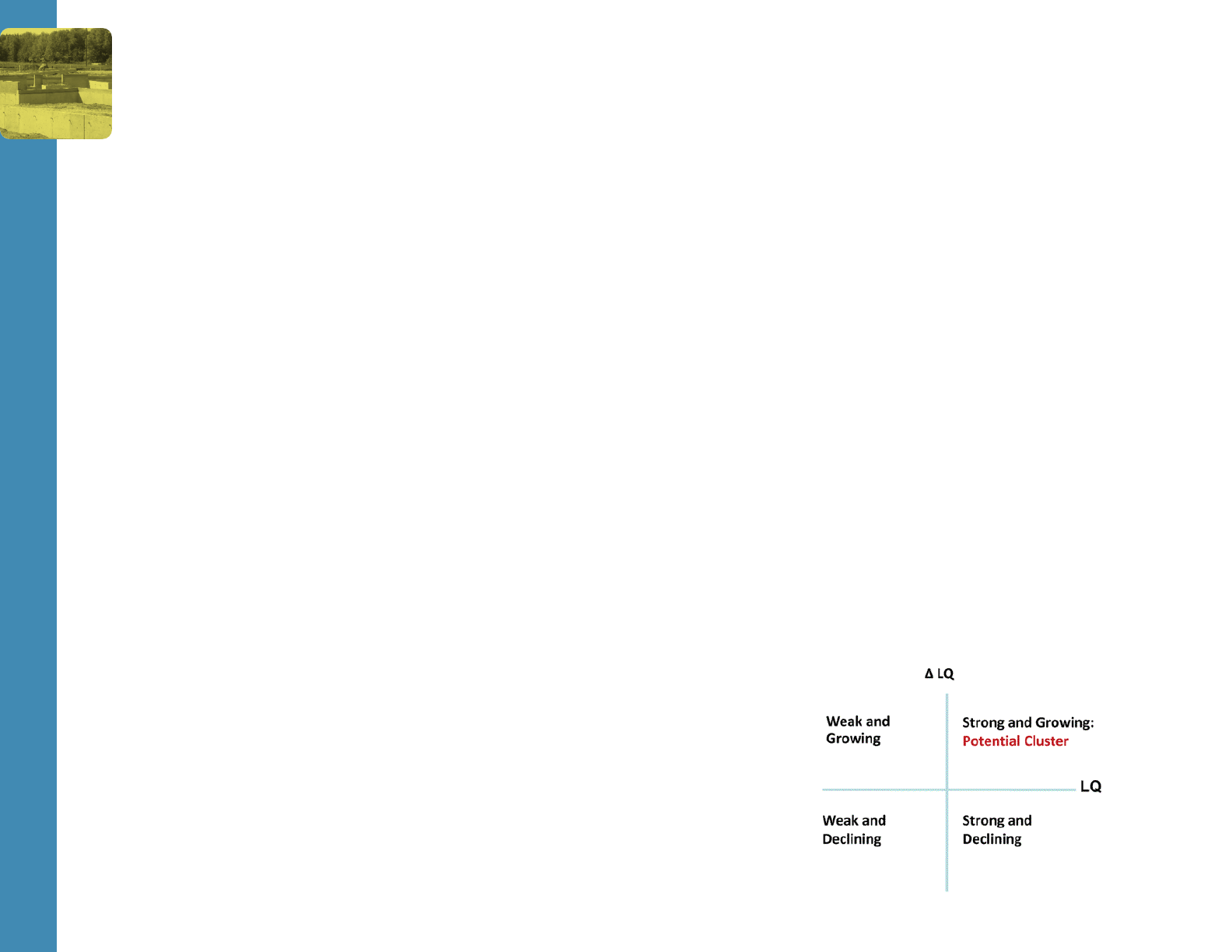

Figure 4-6: Porter’s

Identification of Clusters.

Industries that have an LQ that

exceeds the national LQ and is

also increasing over time might

be considered a cluster.

However, the cluster’s status

could always change, and

likewise for the other categories.

This analysis helps identify trends

and inform where businesses,

governments, and economic

development organizations

want to focus their resources.

Source: Steven Deller

9

.

Building BC 4-8

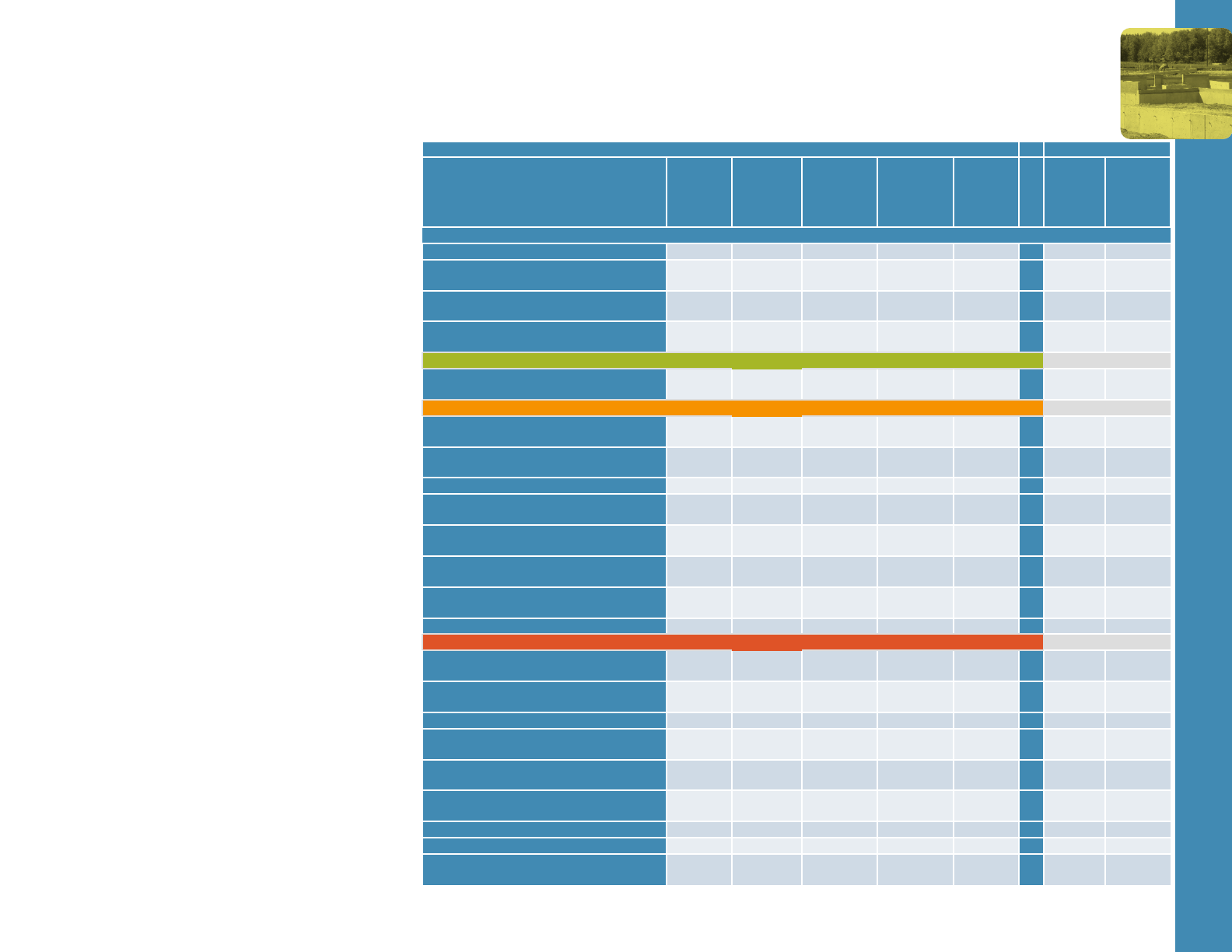

Figure 4-7 analyzes industrial

clusters in the Green Bay MSA by

occupational sector (the Green

Bay MSA includes Brown,

Kewaunee, and Oconto counties;

this data was only available down

to the MSA level, not to the county-

level). Figure 4-7 is the tabular

display of data, the same analysis

which Figure 4-6 on the previous

page.

The four different categories show

which sectors are considered basic

and non-basic, and which have

increased or decreased since

2015. Taken together, the four

sectors identified as a local

“strength and growing”

accounted for 36.4% of the

metropolitan area’s employment

share.

The 2019 statewide LQ and

change in LQ from 2015-2019 for

the same industries are shown to

the far right (the industry statuses,

“strength and growing”, etc., are

not analyzed for the state LQ

values . The Green Bay MSA has a

greater concentration of

production occupations

compared both statewide and

nationally. The Green Bay MSA is

generally comparable with

Wisconsin across the other

occupations and mirrors the same

decline in the “weakness and

declining” category.

III. Existing Economic Conditions

Figure 4-7: Green Bay MSA Cluster Analysis WI Statewide LQ

Occupational Title

May 2015

Green

Bay MSA

Total Emp.

May 2019

Green

Bay

MSA Total

Emp.

Share of

Total Emp.

2019 Green

Bay MSA

Location

Quotient

LQ

Change

2015 -

2019

2019 WI

LQ

WI LQ

Change

2015-2019

Strength and Growing

Production Occupations 18,290 21,800 12.5%

2.00

0.33 1.87 0.95

Installation, Maintenance, and Repair

Occupations 6,870 7,170 4.1%

1.06

0.05 1.01 0.09

Healthcare Practitioners and Technical

Occupations 8,470 10,860 6.2%

1.05

0.11 1.04 0.12

Office and Administrative Support

Occupations 26,110 23,780 13.6%

1.02

0.01 .96 0.04

Strength and Declining

Transportation and Material Moving

Occupations 12,700 16,310 9.3%

1.09

-0.06 1.02 0.10

Weakness and Growing

Architecture and Engineering

Occupations 2,270 3,030 1.7%

0.98

0.10 1.08 0.16

Construction and Extraction

Occupations 5,880 6,920 4.0%

0.94

0.01 .91 -0.01

Healthcare Support Occupations 4,340 7,120 4.1%

0.92

0.16 1.08 0.16

Community and Social Service

Occupations 1,600 2,370 1.4%

0.89

0.11 .90 -0.02

Educational Instruction and Library

Occupations 8,460 9,110 5.2%

0.86

0.02 .96 0.04

Building and Grounds Cleaning and

Maintenance Occupations 4,770 4,240 2.4%

0.80

0.02 .93 0.01

Life, Physical, and Social Science

Occupations 790 1,180 0.7%

0.77

0.06 .93 0.01

Legal Occupations 790 610 0.3%

0.45

0.10 .65 -0.27

Weakness and Declining

Personal Care and Service

Occupations 5,060 3,820 2.2%

0.97

-0.32 .87 -0.05

Business and Financial Operations

Occupations 7,530 9,040 5.2%

0.93

-0.03 .95 0.03

Sales and Related Occupations 16,680 15,830 9.1%

0.93

-0.07 .94 0.02

Food Preparation and Serving Related

Occupations 14,690 14,430 8.3%

0.90

-0.03 .92 0.00

Computer and Mathematical

Occupations 4,140 4,760 2.7%

0.88

-0.03 .88 -0.04

Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports, and

Media Occupations 2,190 1,870 1.1%

0.78

-0.22 .92 -0.11

Management Occupations 7,430 7,220 4.1%

0.75

-0.11 .78 -0.14

Protective Service Occupations 3,110 2,980 1.7%

0.72

-0.15 .77 -0.15

Farming, Fishing, and Forestry

Occupations 290 170 0.1%

0.29

-0.15 .61 -0.31

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment and Wages from Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) Survey,

2015 and 2019. Occupational sectors with a declining LQ from 2015-2019 shown in red. Employment shares greater

than 5% are highlighted in the far-right column.

Building BC 4-9

Figure 4-8.1 displays an analysis of Green Bay MSA

production-related occupations, which is the

occupational group with the highest LQ value in the

Green Bay area. Production-related occupations are

more highly concentrated in the Green Bay MSA

compared to other U.S. metropolitan areas. This table

shows the positively trending production strengths in the

Green Bay MSA. Compared to both the rest of the state

and the U.S., the Green Bay MSA has a much higher share

of workers in the paper goods production field. Brown

County and the Green Bay MSA has several production

occupations that have been growing, and that is a good

regional economic trend.

Because these are regional strengths, Brown County’s

focus should be to support and nurture these industries.

Additionally, these are important industries to consider

when thinking about how future production techniques,

consumer preferences, and labor force needs might

change, and how to address those changes in these

industries.

III. Existing Economic Conditions

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment and Wages from Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) Survey, 2015 and 2019. Occupational sectors with a declining LQ from 2015-

2019 shown in red. Occupations listed by 2019 LQ rank (highest-lowest). State values corresponded with GB MSA rank and may be out of order relative to state rank.

Figure 4-8.1: Green Bay MSA Production-Related Occupations Cluster Analysis – Growing Strengths

SOC

Code

Occupation

2019

Employment

2019 LQ

Change 2015

to 2019

Share of

Production

Employment

WI 2019

WI

Change

2015-2019

Strength and Growing

51-9196

Paper Goods Machine Setters, Operators, and Tenders

1,770

14.85

13.74

8.12%

4.73

0.42

51-2051

Fiberglass Laminators and Fabricators

180

7.38

3.54

0.83%

0.98

0.98

51-3099

Food Processing Workers, All Other

350

6.84

4.91

1.61%

1.04

0.21

51-5111

Prepress Technicians and Workers

220

6.11

3.64

1.01%

2.65

0.24

51-3091

Food and Tobacco Roasting, Baking, and Drying Machine Operators

and Tenders

130

5.4

4.03

0.60%

3.64

1.79

51-3022

Meat, Poultry, and Fish Cutters and Trimmers

970

5.3

4.17

4.45%

1.27

0.4

51-5112

Printing Press Operators

990

4.81

1.42

4.54%

2.77

0.47

51-9111

Packaging and Filling Machine Operators and Tenders

2,230

4.8

2.58

10.23%

3.19

1.0

51-2041

Structural Metal Fabricators and Fitters

420

4.57

3.66

1.93%

3.35

0.77

51-9081

Dental Laboratory Technicians

170

4.03

0.4

0.78%

1.8

0.61

51-3023

Slaughterers and Meat Packers

340

3.86

0.4

1.56%

1.84

-0.42

51-7021

Furniture Finishers

70

3.58

2.11

0.32%

1.38

0.76

51-9023

Mixing and Blending Machine Setters, Operators, and Tenders

350

2.33

2.33

1.61%

2.13

0.19

51-7011

Cabinetmakers and Bench Carpenters

270

2.26

1.53

1.24%

1.76

0.66

51-1011

First

-Line Supervisors of Production and Operating Workers

1,570

2.1

0.5

7.20%

2.02

0.31

51-9162

Computer Numerically Controlled Tool Programmers

50

1.74

0.11

0.23%

2.4

2.4

51-4121

Welders, Cutters, Solderers, and Brazers

840

1.71

1.36

3.85%

1.96

0.13

51-9083

Ophthalmic Laboratory Technicians

50

1.49

1.49

0.23%

0.91

-0.19

51-9198

Helpers

--Production Workers

510

1.43

1.43

2.34%

1.19

-0.25

51-4031

Cutting, Punching, and Press Machine Setters, Operators, and Tenders,

Metal and Plastic

300

1.28

0.67

1.38%

2.75

0.64

51-4041

Machinists

580

1.27

0.61

2.66%

1.56

-0.32

51-2090

Miscellaneous Assemblers and Fabricators

2,000

1.23

0.03

9.17%

1.79

1.79

Building BC 4-10

Figure 4-8.2 displays the other three categories of

production-related clusters in the Green Bay MSA. The

occupations in 4.8.2 do not generally have as many

employees as in 4.8.1 and are generally declining in

employment share. The decline could be for different

reasons, possibly including changing consumer

preferences, business conditions, and/or regulatory

requirements.

The Strength and Declining category employs the most

workers of these three categories, and still have a greater

concentration of workers compared to the U.S., and to all

but two occupations compared to Wisconsin. All these

occupations provide an opportunity to consider future

changes, impacts, and trends.

III. Existing Economic Conditions

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment and Wages from Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) Survey, 2015 and 2019. Occupational sectors with a declining LQ from 2015-

2019 shown in red. Occupations listed by 2019 LQ rank (highest-lowest). State values corresponded with GB MSA rank and may be out of order relative to state rank.

Figure 4-8.2: Green Bay MSA Production-Related Occupations Cluster Analysis – Declining Strengths and Weaknesses

SOC

Code

Occupation

2019

Employment

2019 LQ

Change 2015

to 2019

Share of Production

Employment

WI 2019

WI Change

2015-2019

Strength and Declining

51

-5113

Print Binding and Finishing Workers

320

5.96

-

2.09

1.47%

3.86

0.11

51

-9161

Computer Numerically Controlled Tool Operators

740

4.11

-

6.18

3.39%

4.62

4.62

51

-3092

Food

Batchmakers

660

3.48

-

0.66

3.03%

2.69

-

0.12

51

-9124

Coating, Painting, and Spraying Machine Setters, Operators,

and Tenders

310

1.76

-

1.13

1.42%

2.26

2.26

51

-9061

Inspectors, Testers, Sorters, Samplers, and

Weighers

1,170

1.7

-

0.89

5.37%

1.59

0.22

51

-7041

Sawing Machine Setters, Operators, and Tenders, Wood

80

1.3

-

0.96

0.37%

1.85

-

0.04

51

-6093

Upholsterers

40

1.13

-

2.02

0.18%

0

-

0.46

Weakness and Growing

51

-8031

Water and Wastewater Treatment Plant and System Operators

90

0.65

0.65

0.41%

0.92

-

0.29

51

-4111

Tool and Die Makers

60

0.73

0.08

0.28%

2.71

0.41

51

-2031

Engine and Other Machine Assemblers

40

0.79

0.06

0.18%

1.65

0.52

Weakness and Declining

51

-6031

Sewing Machine Operators

110

0.7

-

0.23

0.50%

1.18

0.29

51

-2028

Electrical, Electronic, and Electromechanical Assemblers,

Except Coil Winders, Tapers, and Finishers

240

0.7

-

0.48

1.10%

1.94

0.05

51

-3021

Butchers and Meat Cutters

120

0.76

-

0.53

0.55%

0.67

-

0.06

51

-4023

Rolling Machine Setters, Operators, and Tenders, Metal and

Plastic

30

0.81

-

0.56

0.14%

0

-

0.6

51

-4072

Molding,

Coremaking, and Casting Machine Setters,

Operators, and Tenders, Metal and Plastic

200

0.95

-

0.82

0.92%

2.85

0.21

51

-9011

Chemical Equipment Operators and Tenders

40

0.38

-

2.34

0.18%

1.29

0.66

51

-4033

Grinding, Lapping, Polishing, and Buffing Machine Tool Setters,

Operators, and Tenders, Metal and Plastic

50

0.54

-

2.47

0.23%

2.91

-

0.05

51

-9012

Separating, Filtering, Clarifying, Precipitating, and Still Machine

Setters, Operators, and Tenders

50

0.88

-

4.12

0.23%

1.55

-

0.62

51

-6011

Laundry and Dry

-Cleaning Workers

220

0.89

-

4.98

1.01%

0.86

-

0.11

Building BC 4-11

SWOT Analysis

Through the Economic Development Strategic

Plan, the Greater Green Bay Chamber

developed a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses,

Opportunities, and Threats) analysis of the

area

10

.

• Strengths. Advan

tages that can be built on

to grow and strengthen the regional

economy.

• Weaknesses. Liabil

ities and obstacles to

economic development that could limit the

region’s growth potential.

• Opportunities. Assets

and positive trends

that hold significant potential for increased

regional prosperity and the attraction of new

businesses, investments, and people.

• Threats. Unfavorable external factors and

tren

ds that could negatively impact the

regional economy.

Area Strengths

The largest category for the Green Bay SWOT

analysis is the strengths. Many of those can be

attributed to Brown County’s location, being a

regional employment center, and having a

growing population. All these factors are

intertwined and provide a solid foundation.

The affordable housing and low-cost living

(relative to other regional metro areas), range

of businesses, industries, and corporate

headquarters help make the area a desirable

place to locate to.

IV. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities,

and Threats

Source: Greater Green Bay Chamber Economic Development Strategic Plan

Building BC 4-12

Transportation Network

Brown County has access to a multi-modal

transportation network that includes air, rail,

port, and the interstate to move goods across

the country and the globe. With Interstates 41

and 43, and State Highways 172 and 29, Brown

County has excellent freeway service

connecting to the Fox Valley, Milwaukee,

Chicago, and Minneapolis/St. Paul.

Higher Education

Another strength is Brown County’s higher

educational institutions, and the different

educational opportunities offered for people

at all career stages. These educational

resources are especially important as the

economy continues to change and become

more high-skilled.

Leadership and National Recognition

The Brown County LIFE Study

11

also examined

strengths and opportunities in Brown County.

The study identified the following economic

development strengths:

• Community and leader support for

econo

mic development and revitalization.

• Variety of new projects underway that will

attrac

t tourists and spur economic growth.

Brown County and Green Bay are also unique

among cities its size by being nationally, and

even internationally, recognized as the home

of the Green Bay Packers.

IV. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities,

and Threats

Source: Greater Green Bay Chamber Economic Development Strategic Plan

This allows for a national spotlight

on the area that would probably

not otherwise occur to this degree.

The Packers organization and the

local communities have capitalized

on this with the creation of the

Titletown District development.

Area Weaknesses

Intergovernmental Competition

Brown County faces a challenge in

attracting or retaining business and

industry because of intense

competition among Brown County

communities for any proposed

large economic development

project. While competition can be

healthy, in economic development

it often pits one community against

another to see which can offer the

most financial incentives for a

business to locate in their

community. Although this provides

immediate tax base and jobs to the

“winning” community, it can create

a drain on the community’s funding

mechanisms (tax-increment

financing, infrastructure

improvements, employment

incentives, etc.)and heightened

expectations for the next business

looking to locate in the community.

The “losing” community may have

spent time and resources trying to

attract the business. In the case

where it was trying to retain an

existing business by offering new

incentives to stay, the community is

potentially left with a vacant

building and an unemployment

increase if the business moves

outside of commuting distance

from its previous location.

Building BC 4-13

Skills, Opportunities, and Educational Gap

Another weakness is that prior to the Covid-19

pandemic, coupled with low unemployment, some

employers struggled to fill professional and skilled-

trade positions.

Area Opportunities

Brown County and local municipalities have an

opportunity to collaborate to promote economic

development regionally. The area has already

seen leadership come from people and

organizations in the county, and the county should

continue to support those efforts.

Building Regional and National Connections

While the Covid-19 pandemic has changed travel

in the short-term, Brown County is geographically

located near several of the Midwest’s important

regional centers. The Green Bay Austin Straubel

International Airport has also more recently

established seasonal connections with Denver and

Orlando.

Bridging Skills, Opportunities, and Educational Gaps

The Brown County LIFE Study identified three

specific economic opportunities for improvement:

• How to attract and maintain high-payin

g jobs.

• Retention of young professionals in the area.

• Ensuring a match between area jobs and

educ

ation/training opportunities.

The last point may be one of the most important to

help spread prosperity in the area, and to ensure

that the entire community moves forward more

evenly.

Attracting New Businesses

The top ten site selection factors table (right) shows

how those factors have changed for corporate

executives over the last 30 years. Labor cost was

considered the most important factor in 1986. In

2015, the availability of skilled labor was the most

important factor for site selection.

IV. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities,

and Threats

Source: Greater Green Bay Chamber Economic Development Strategic Plan

The relevance of quality of life

has also increased in that time.

All these factors represent

opportunities for Brown County to

improve on because they can

help with business attraction.

4-14

Target Specific Industries

The Greater Green Bay Chamber Strategic

Economic Development Plan lists specific

target industries (below) in its strategies and

actions to fulfill Initiative 3: Recruit New

Businesses and Investments. The six target

industries listed below represent opportunities

that could maximize a community return on

investment. While other industries may be

investment-worthy, these represent the best

community investment opportunities for the

Green Bay area because they are

established industry clusters, and because

they align with current technology and

growth trends.

Target Early Trends

In August 2020, the Bay Area Community

Council’s Signals Team reported early signals

of emerging economic trends. From

collecting trend information, the team

highlighted the following

12

:

• Entrepreneurship and innovation – With a

ll

the uncertainty around COVID-19, fast-

moving entrepreneurs will have

opportunities to develop new products,

services, and business models.

• Women in the workplace – Compan

ies

with diverse, inclusive cultures gain a

competitive edge over their competitors,

and when women can achieve their first

leadership position in an organizational

leadership track, they progress well.

• Workforce availability – Aging w

orkforces

will require new workers, and there are

gaps to bridge in terms of education and

skills/training to ensure enough future

workers.

IV. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities,

and Threats

Source: Greater Green Bay Chamber, 2018 Greater Green Bay Strategic Plan

Greater Green Bay’s Six Target Industries (Part of Initiative 3: Recruit New Businesses and

Investments).

3.1. Focus Greater Green Bay’s business attraction and marketing efforts on six target industries, which

represent the best opportunities for new investment and employment growth.

3.1.1. Advanced Manufacturing: paper products, food processing, industrial machinery, industrial

design.

3.1.2. Digital Media and Entertainment: sports & sports technology, digital media (including

virtual/augmented reality).

3.1.3. Health Care and Medical Technology: medical specialties, medical training, sports medicine,

health software and IT.

3.1.4. Logistics and Distribution: truck transportation, water-based transportation, logistics

consulting services.

3.1.5. Corporate HQs: national HQs, regional/divisional HQs, corporate supply chain (professional

services).

3.1.6. Financial Services: bank HQs, regional banks and credit unions, insurance services.

Source: Greater Green Bay Chamber, 2018 Greater Green Bay Strategic Plan

• Technological advances –

Advances in blockchain and 5G

technology will expand the

development of the Internet of

Things systems.

4-15

Area Threats

Employee Attraction and Retention

The Chamber’s Greater Green Bay

Economic Development Strategic Plan

identified different threats to the area.

In the plan, based on survey responses

from Brown County employers, the most

important factor identified for business

success was the “ability to attract and

retain qualified employees.” That factor

was given the highest priority for

improvement by the study and is

something that the Green Bay area had

below-average performance.

Lack of Equitable Opportunities

The LIFE Study lists 25 concerns in the key

findings that were raised during the

study process. The economic- and

work-related findings include:

• Constant pressure on arts and cultural

orga

nizations to fundraise.

• Child poverty rate has remained high

in Br

own County.

• Sizable number of people reported

being

unable to obtain affordable

childcare.

• More pronounced achievement gap

in Br

own County compared to the

state.

• Concern about the disproportionate

suspensi

ons of minority students.

• Rising costs of higher education.

IV. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities,

and Threats

Source: Greater Green Bay Chamber Economic Development Strategic Plan

• Concern the local workforce

can’t keep pace with growth in

tourism in the coming years.

• Housing cost burden.

• Increase in the number of

childr

en identified as homeless in

local public schools.

• Disparities in hunger by income

level.

• L

ittle improvement to poverty

rate ov

er time.

• Wages lower than the state

aver

age within some sectors of

the economy.

• Need to continue to innovate to

ensu

re economic growth and

development.

Some ways to change this that are

in the LIFE Study include education

for community members at all life

stages, and that adults (young and

returning) can obtain affordable

higher education leading to

improved career development, and

that learning matches area

employment and opportunities.

While the industrial sector in Green

Bay makes up an important share of

the economy, it could always be

subject to market forces and/or

technological changes. One way

to buffer against these changes is to

ensure that industries and workers

can adapt and change, and that

companies have the foresight and

vision to see those threats.

Building BC 4-16

An economic opportunity area is an

existing or future location that

contributes to or will contribute to the

community’s tax base and overall

identity. The area may be as small as a

grouping of local businesses or as large

as a downtown or business park.

Because this is a county comprehensive

plan update, the economic

development opportunity areas are

more county-focused on large,

commercial/industrial drivers of the

county economy, or specific

opportunities for Brown County to

participate in economic development

initiatives.

Central Business Districts

Central business districts in Brown

County include the traditional

downtowns of the Cities of Green Bay

and De Pere, and the small downtowns

in the Villages of Denmark, Pulaski, and

Wrightstown. These downtowns are

home to industry, business, government,

and residential neighborhoods. They

serve as the economic and social

hearts of the communities.

Downtowns can provide a central

space where people can gather, like

on Green Bay’s CityDeck and De Pere’s

Riverwalk and Wildlife Viewing Pier.

Downtowns can also have public

facilities, such as the Brown County

Central Library and the Neville Public

Museum. Downtowns also provide the

backdrop for many outdoor events,

such as weekly farmers’ markets, the

Bellin Run, the Tall Ships event, annual

parades, and festivals such as Art Street

in downtown Green Bay, Celebrate De

Pere, and Pulaski Polka Days. Many

historic places of worship, which

contribute to the cultural and social

fabric of Brown County, are also

located in the downtowns.

Downtowns have available land for

redevelopment and expansion, and

local government should continue to

make land available through the

environmental assessment and

remediation of polluted or potentially

polluted (brownfield) sites. Brown

County has successful brownfield

redevelopment examples in both

downtown Green Bay and De Pere. In

Green Bay, the former Port Plaza Mall

was demolished, the site assessed and

remediated, and is now the location for

the new Schreiber Cheese corporate

headquarters. The city is also working

on the Shipyard project on the Fox

River, just north of Mason Street.

Voyageur Park in downtown De Pere

was a bulk storage site for coal and salt

but is now a nationally-renowned

fishing location.

Central business districts are also seeing

new residential development infill.

Recent trends have seen a renewed

interest in city living, particularly among

young people and empty-nesters as

they look for vibrant places to live.

Residential uses, including apartments,

condominiums, and dense, mixed-use

developments provide core customers

for downtown businesses during non-

work hours. As communities evaluate

opportunities for downtown

development, including residential uses

are important to the mix.

V. Economic Development Opportunity

Areas

Downtown Green Bay residential living. Source:

Brown County Planning Commission.

Building BC 4-17

Business and Industrial Parks

Business and industrial parks are

generally created through assembling

and subdividing land, and then

developing it according to a master

plan. This includes providing street

layout, railroad tracks, and installed

utilities prior to selling sites. The

development of business parks

emphasizes the importance of physical

land use planning details to achieve

efficiency and compatibility and

stresses operational responsibility and

maintenance standards to protect the

park’s value to the occupants.

These facilities are often sited with

convenient access to the highway

network and rail access. On the

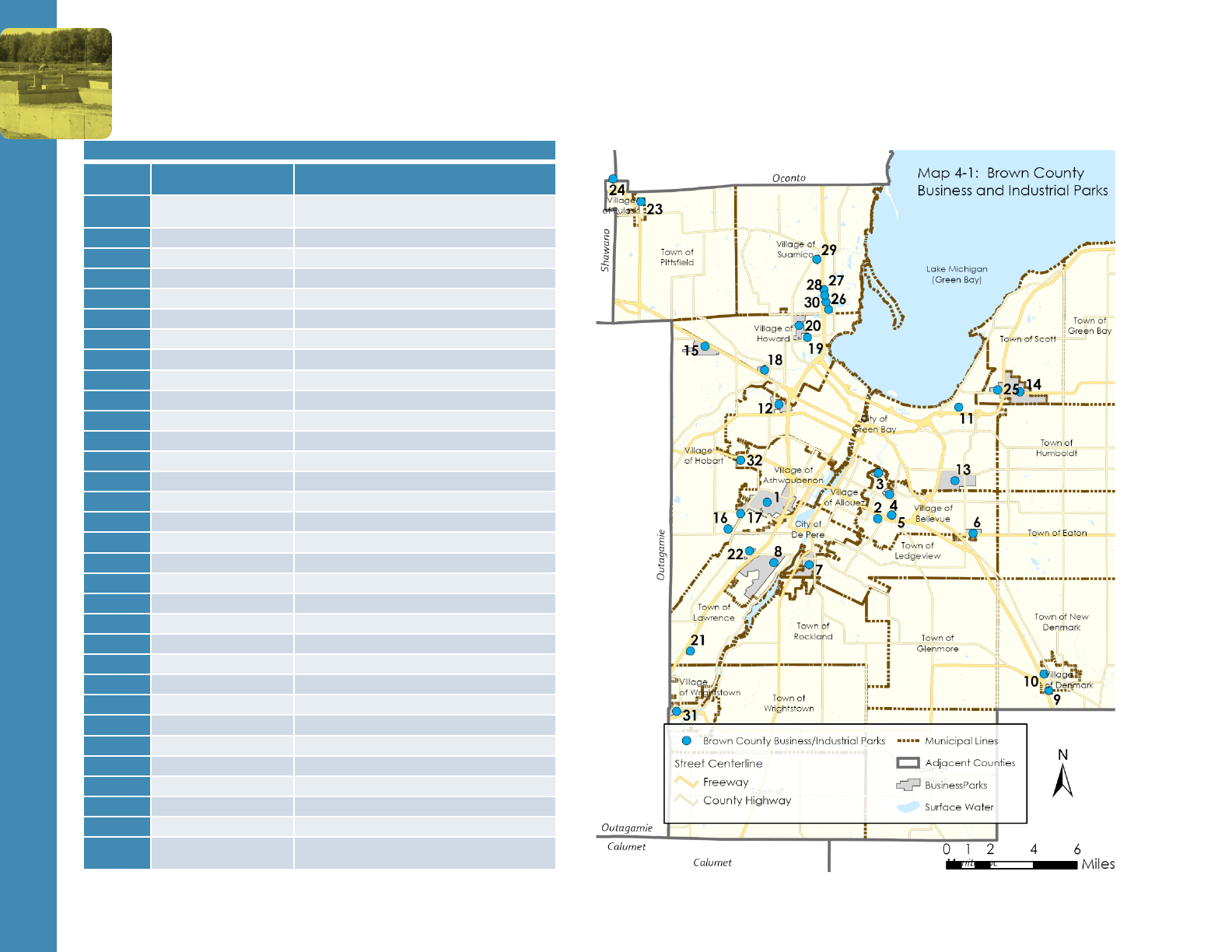

following page, Figure 4-9 identifies the

municipality and the name of business

and industrial parks within Brown

County, and Map 4-1 shows the

corresponding map number location.

While a few business parks in Brown

County have been developed

privately, municipalities have

developed most of them. Examples of

municipally-developed business parks

include the I-43 Business Center on

Green Bay’s east side, the West De Pere

Business Park located in southwest De

Pere, the Ashwaubenon Business Center

/ Industrial Park, and the Howard

Industrial Park.

Within the listed business and industrial

parks in Figure 4-9 (following page), a

variety of space is available throughout

Brown County. The Brown County Land

Information Office maintains a web-

based application that identifies

available acreage within the business

and industrial parks in Brown County. A

web link on the site provides additional

detail from the local municipalities

including such characteristics as

contact person, utility capacity and

availability, zoning, and available

incentives.

Green Bay Austin Straubel International

Airport

The Green Bay Austin Straubel

International Airport (GRB) is located

approximately five miles southwest of

downtown Green Bay in the Villages of

Ashwaubenon and Hobart. GRB is the

third largest airport in Wisconsin and is a

24-hour, 365-day a year operation. A

2017 WisDOT economic impact study

indicated that the airport provided

$265.3 million in economic output,

supported 1,719 jobs, and contributed

$77.2 million in labor income to the

state and local economy

13

.

Phoenix Innovation Park

In addition to the identified business

and industrial parks, Brown County, in

partnership with the University of

Wisconsin – Green Bay and the City of

Green Bay, is developing the Phoenix

Innovation Park on approximately 200

acres of land, immediately south of the

university on Green Bay’s east side. The

research and business park is being

developed to fill a need for an area

dedicated to encouraging

entrepreneurs to expand their

businesses beyond the initial start-up

phase. The research and business park

will provide linkages to UW-Green Bay

resources, while also supporting the

businesses already existing within Brown

County.

The first phase of this was realized with

the Brown County STEM Innovation

Center, completed in 2019 on the UW-

Green Bay Campus. The 63,730 square-

foot facility is the home of the UW-

Green Bay’s Richard J. Resch School of

Engineering, along with the Einstein

Project, Extension Brown County, and

Brown County Land and Water

Conservation. The engineering

program was started in 2019 to address

Northeast Wisconsin’s educational

training and skills gap of qualified

employees, and to support regional

manufacturing growth and

entrepreneurship.

V. Economic Development Opportunity

Areas

Brown County STEM Innovation Center. Source:

Brown County Planning Commission.

Building BC 4-18

Brown County Resource Recovery Park

Brown County owns approximately

1,500 acres of land in southern Brown

County for development of a future

landfill as Brown County’s contribution

to the Tri-County Solid Waste

Agreement with Outagamie and

Winnebago counties. All 1,500 acres

will not be needed for the landfill, and

in identifying opportunities for use of the

some of the remaining acreage, the

Brown County Waste Stream

Committee identified the excess

acreage as a potential site for a

resource recovery or resource

management park.

A resource recovery park provides

waste landfilling options to

homeowners, businesses, and industries

by diverting economically valuable

products from the waste stream. The

recovered items can then be

reprocessed, repurposed, and sold as

either finished products, such as

compost, or raw materials for new

products. The raw materials produced

from a resource and recovery park

could further diversify our local

economy by creating a new

“recoverable materials” sector while

also furthering the lifespan of the

landfill, and addressing environmental

issues associated with landfilling these

materials.

Port of Green Bay

The Port of Green Bay is a critical

component of the greater Green Bay

and Northeastern Wisconsin economy.

According to the 2017 Port of Green

Bay Economic Impact Study, the Port

contributes $147 million to the economy

while supporting 1,289 jobs.

The Port, Brown County, and the City of

Green Bay are currently looking at the

former WPS Pulliam Site as a possible

port development opportunity. The

Brown County Planning Commission is

drafting a Port Opportunity Study as

part of this effort.

The Port may have a regional

opportunity to add an intermodal

transportation facility. The 2013 Brown

County Port/Rail “White Paper”

demonstrated sufficient transportation

volume to justify and sustain intermodal

service. The viability of this will be

examined in greater detail in 2021

when Brown County, New North, Inc.,

and the East Central Regional Planning

Commission conduct an intermodal

freight facility study for Northeast

Wisconsin.

In addition to importing and exporting

commodities via the Great Lakes, the

Port of Green Bay operates Foreign

Trade Zone #167, which was

established in 1990. Within foreign

trade zones (FTZs), foreign and

domestic merchandise may be moved

into foreign trade zones for operations

not otherwise prohibited by law,

generally including storage, exhibition,

assembly, manufacturing, and

processing. Within a foreign trade zone

(or sub zone) typical customs and

border patrol entry procedures and

payments of duties are not required on

foreign merchandise unless and until it

exits the Foreign Trade Zone for

domestic consumption. Trade Zone

#167 consists of 4,001 acres, located in

Brown and Winnebago counties, with

five sites in Brown County.

The established FTZ and the existing and

future subzones could provide a unique

business incentive to work with the Port

of Green Bay. Within Wisconsin, only

Milwaukee and Dane Counties also

have an active Foreign Trade Zone

program. As Northeastern Wisconsin’s

economy becomes more global, the

Port’s FTZ designation provides a

locational advantage to businesses.

V. Economic Development Opportunity

Areas

Ship unloading in the Port of Green Bay. Source:

Brown County Planning Commission.

Building BC 4-19

V. Economic Development Opportunity

Areas

Source: Brown County Planning Commission.

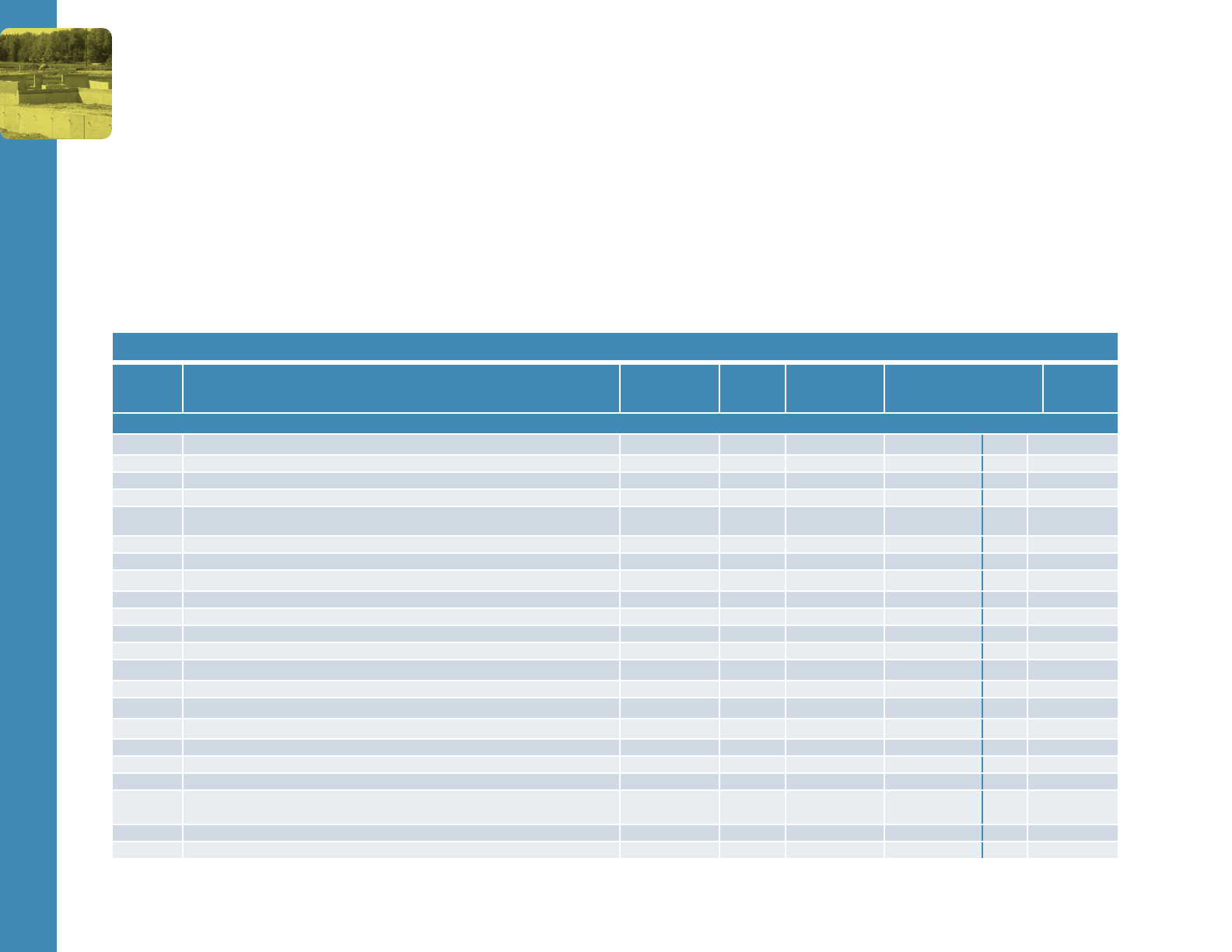

Figure 4-9: Brown County Business and Industrial Parks

Map

Number

Municipality Business / Industrial Park

1

Village of

Ashwaubenon

Ashwaubenon Business Center / Industrial

Park

2

Village of Bellevue Millennium Park

3

Village of Bellevue Bellevue Street Industrial Area

4

Village of Bellevue Lime Kiln Road Industrial Area

5

Village of Bellevue GV-172 Business Park

6

Village of Bellevue Hwy 29 Commercial Park

7

City of De Pere De Pere Industrial Park

8

City of De Pere West Business Center

9

Village of Denmark Norse Business Park

10

Village of Denmark Viking Business Center

11

City of Green Bay UWGB Phoenix Innovation Park

12

City of Green Bay Packerland Industrial Park

13

City of Green Bay I-43 Business Center

14

City of Green Bay University Heights Commerce Center

15

Village of Hobart Centennial Centre at Hobart

16

Village of Hobart Hobart Industrial Park

17

Village of Hobart Plane Site Industrial Park

18

Village of Howard AMS/Lancaster Creek Business Park

19

Village of Howard Brookfield Industrial Area

20

Village of Howard Howard Industrial Park

21

Town of Lawrence Granite Rock Industrial Park

22

Town of Lawrence Lawrence Business / Industrial Park

23

Village of Pulaski Pulaski Industrial Park

24

Village of Pulaski Pulaski North Industrial Park

25

Town of Scott Scott Industrial Park

26

Village of Suamico Deerfield Business Park

27

Village of Suamico North Deerfield Business Park

28

Village of Suamico South Deerfield Business Park

29

Village of Suamico Suamico Industrial Park

30

Village of Suamico Woodfield Business Park

31

Village of Wrightstown

Wrightstown Industrial Park

32

Village of

Ashwaubenon

Green Bay Austin Straubel International

Airport

Source: Brown County Planning Commission.

Building BC 4-20

Regional Commercial Centers

Commercial shopping centers in Green

Bay and across the United States have

seen a rise and fall in fortunes.

Traditionally, these centers are a

grouping of retail stores or service

businesses planned and designed for

the site on which they are built and are

often located away from the central

business district, serving suburban and

exurban shopping needs. While they

grew in size and number since their

arrival in the 1950s, they also drew

shoppers away from downtowns and

main streets. These centers proliferated

because of suburban growth and the

increased role of the automobile. They

required large sites, often previously

undeveloped, and could be difficult to

get to without a car. They also relied on

large anchor tenants to draw

customers. These shopping centers

offered a large amount of surface

parking space and were usually

oriented toward highways or major

arterials.

Examples of commercial shopping

centers in Brown County include the

Bay Park Square Mall on Oneida Street

in Ashwaubenon, the Green Bay Plaza

Shopping Center on West Mason Street

in Green Bay, and the Urban Edge

development in the Village of Suamico.

In addition to the large shopping

centers, there are numerous other

smaller retail/service shopping centers

located throughout Brown County,

including the rural villages. As these

shopping centers age and ownership

changes, they may experience higher

vacancy rates and become more

challenging to fill. Many large national

retail chains have also closed

underperforming stores, and for a

variety of reasons, have not opened

new ones.

Nationally, many former auto-oriented

shopping centers are being

redeveloped to be more pedestrian-

friendly. The large parking lots are

being moved behind or to the side of

the stores and buildings are being

moved to the street with adequate

space for outside dining and seating

areas. A 2013 study prepared by Gary

Hack, Ph.D. for the Robert Wood

Johnson Foundation found among

others

14

:

• There is great enthusiasm for

walkab

le shopping areas among

retail experts, developers, and many

residents of urban and suburban

areas.

• Walkable shopping areas have a

poten

tial to prosper as a result of

demographics, increased gas prices,

public policies encouraging higher

densities, and changing lifestyle

preferences.

• Businesses can be successful if such

areas reac

h a critical mass, cater to

diverse needs, are in higher densities,

or have good mass transit service,

and have a supermarket as an

anchor.

• With success, enterprises in walkable

shop

ping areas can pay higher rents

for their space, and housing near

walkable commercial areas

commonly sells for higher prices than

more distant areas.

Redevelopment of shopping centers in

this manner should be encouraged to

create a livelier and more interesting

streetscape and sustainable

development pattern.

Another recent trend is converting

vacant malls and retail space into

residential units such as apartments, or

even senior housing. This approach

could help address both vacant

commercial space, and the need for

more housing

15

.

V. Economic Development Opportunity

Areas

Belmar is an open-air shopping district in Lakewood

CO, built on the site of a former Villa Italia Mall.

Source: Google Earth.

Building BC 4-21

Brick-and-Mortar Stores

Recent commercial trends have shifted

towards more online shopping, creating

competitive challenges for brick-and-

mortar storefronts. Also, commercial

leasing terms and lease rates have

made some commercial spaces less

attractive with the competition from e-

commerce

16

.

Some brick-and-mortar stores have

adapted to these changes by offering

amenities that can’t be replicated

through the online shopping

experience. Some of these include:

• Showrooming – The r

etailer turns the

store into a “showroom” floor for

product marketing, keeping limited

inventory. Customers purchase

products online (in the store or off-

site), and products are warehoused

and distributed from more cost-

effective locations.

• Experience-Driv

en Retail – Retailers

use more floor space for in-store

experiences such as product

demonstrations, personalization, and

entertainment opportunities. The

experiences are a way to further

market the product/brand in a way

that cannot be done online.

• Restaurant Integration – Anothe

r

experience-based strategy, food

and drink retailers have added

restaurants and food/drink service

into their stores, which helps drive

store traffic, and provides additional

revenue.

• On-Site and In-Stor

e Co-Tenancy –

Online and specialty retailers can

benefit from a physical presence,

and larger retailers like department

stores can lease space to these

specialty retailers to offer

complementary products, attract

new customers, and have sublease

income.

• Convenience Everlasting – Peopl

e

will still need to be able to purchase

daily and staple products near where

they live and work from time to time.

Smaller-footprint stores with a

neighborhood-orientation can serve

this need and could have

opportunities to partner with delivery

companies and e-commerce brands

as place to pickup and drop off

orders.

While these approaches may help

retailers with physical locations, there

are also ways that local communities

can support them too.

Managed Expectations and Careful

Planning

Not all communities can, or maybe

even want to, land a national retailer or

chain. Especially with the shift to online

shopping, communities may not be

able to realistically support as much

commercial space as they think they

can. Communities can better

understand community desires through

ongoing conversations happening

during things such as comprehensive

planning updates and planning

commission discussions. The provided

insights can help a community better

understand what it thinks it wants versus

what it can realistically support.

Flexible Uses and Spaces

Zoning that allows more uses (whether

in residential or commercial zones)

provides more flexible space options.

Flexibility for smaller commercial spaces

can help local businesses keep costs

down and can help facilitate new

startups. When concerns arise around

mixing commercial in residential areas,

better commercial design standards

can mitigate and offset many potential

perceived nuisances. Neighborhood

and convenience retail can still provide

for people’s daily shopping needs and

be more resilient to e-commerce.

Discouraging large-format and

irregularly shaped customized

commercial spaces can make these

spaces more easily reusable for future

users and can also help limit

incompatible uses. Coupled with

flexible uses, some of these spaces

could be attractive for future live-work

residences, especially for someone who

works from a home office, but still needs

to accommodate occasional visitors.

Another new zoning trend is allowing

accessory commercial units (ACUs),

that function like accessory dwelling

units (ADUs). A municipality would

modify the zoning code would allow

accessory commercial uses in certain

areas, and the commercial space

would be an accessory use to the

primary residence. This could

potentially reduce startup costs for a

small-business and provide more

affordable commercial space for

someone starting out (like the role of

food trucks for aspiring restaurateurs).

V. Economic Development Opportunity

Areas

Building BC 4-22

Local Programs

Tax Incremental Financing (TIF)

TIF is a financing option that allows

municipalities to fund infrastructure and

other improvements through property

tax revenue on newly developed

property. TIFs are only allowed to be

used for projects that would otherwise

not happen without this financing tool.

The municipality creates a Tax

Increment District (TID), a geographical

area within the municipality identified

for development using a TIF and

assessed for general property tax

purposes.

According to the Wisconsin

Department of Revenue, “The tax

incremental finance law (TIF) was

approved by the Wisconsin Legislature

in 1975 as a financial tool that cities,

villages and towns could use to

promote tax base expansion. It is

targeted toward eliminating blighted

areas, rehabilitating areas declining in

value, and promoting industrial

development.” Recently the law was

amended to include allowing “mixed

use” (typically a mixture of commercial

and residential) development. Towns

that have a boundary agreement with

a city or village may create a

Cooperative TID and access additional

TID types not usually available to towns.

Multijurisdictional TIDs may also be

created to allow two or more cities to

collaborate on development needs.

Within a TID, property tax rates for the

school, county, technical college, and

municipality are based on the taxable

value of the TID on January 1 of the

year that it is created (base year). The

property taxes shared with the

overlaying jurisdictions from within the

TID stay the same as it was in its base

year. However, as new development or

redevelopment takes place within the

TID, the increased valuation and

associated property taxes (the

“increment”) is captured by the local

community to pay off capital

improvements related to development

in the TID. Typically, communities have

up to 27 years to pay off improvements

within the TID, until the district is closed

and the increase in property tax

valuation is then shared by all taxing

jurisdictions.

Brown County

Greater Green Bay Chamber

The Green Bay Area Chamber of

Commerce is committed to improving

and diversifying the economy of Brown

County. The Chamber’s economic

development arm provides confidential

site selection assistance, in-depth

statistical and demographic data, and

manages the Startup Hub, the front

door to all entrepreneurial resources in

Greater Green Bay, located on the

edge of the Northeast Wisconsin

Technical College (NWTC) campus.

Additionally, the Startup Hub has on-site

business partners like on the NWTC Small

Business Initiative and the UWGB Small

Business Development Center. It

provides support services (clerical,

legal, accounting, mentoring, etc.)

within a flexible space for business and

non-profit start-ups. Information

regarding Advance and the business

incubator may be found at:

http://www.titletown.org/programs/eco

nomic-development.

Advance is also part of the Brown

County Culinary Kitchen, which is a

non-profit collaborative effort among

NEW Curative Rehabilitation, The Farm

Market Kitchen, and NWTC. The Brown

County Culinary Kitchen provides a fully

equipped, commercially-licensed,

shared use kitchen for food-based

business start-ups. Additional assistance

includes classes, an on-site manager,

technical assistance, business

coaching, classroom space, and

Internet access. Information regarding

the Brown County Culinary Kitchen may

be found at:

http://bcculinarykitchen.org/

.

VI. Local, County, Regional, and State

Economic Development Programs

Building BC 4-23

Regional

The New North, Inc.

According to the New North website, “New

North, Inc. is 501 (c) 3 nonprofit, regional

marketing and economic development

organization fostering collaboration among

private and public sector leaders

throughout the 18 counties of Northeast

Wisconsin, known as the New North region.”

New North, Inc. represents a strong

collaboration between the 18 counties that

have come together behind the common

goals of job growth and economic viability

for the region. The power of the New North

region working together is far greater than

one county or one business alone. Players

gain more through regional cooperation

rather than competing for resources and

growth.

The New North’s vision is “to be recognized

as nationally and globally competitive for

personal and economic growth.” Its mission

is to be a “catalyst for regional prosperity

through collaboration” and has six key

initiatives to achieve this:

• Attract, develop and retain diverse

talent

• Fo

ster targeted industry clusters and new

markets

• S

upporting an entrepreneurial climate

and s

mall business

• Encouraging educational attainment

• Elevate sustainability as an economic

driver

• Pr

omote the regional brand

Additio

nal information on the New North

can be found at www.thenewnorth.com

.

Wisconsin Public Service

Wisconsin Public Service Corporation (WPS)

also contributes several economic

development services. WPS maintains an

online searchable database for available

commercial and industrial properties. The

WPS economic development page is

located at

https://accel.wisconsinpublicservice.com/b

usiness/economic/businesses.aspx

.

State

Wisconsin Department of Administration

(DOA) Community Development Programs

The Community Development Block Grant

(CDBG) program is a federal formula-

allocated grant program under the U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban

Development (HUD). The DOA administers

the state CDBG program and provides

funding to units of general local

government that do not receive an annual

allocation directly from HUD. For more

information, please see the DOA’s website

for additional details:

https://doa.wi.gov/Pages/LocalGovtsGrant

s/CommunityDevelopmentPrograms.aspx

.

Wisconsin Economic Development

Corporation (WEDC)

The WEDC offers several different programs

to help Wisconsin businesses realize their

goals through funding, resources, and

training. WDEC’s community development

programs include brownfield grants and site

assessment, capacity building grants, idle

sites program, minority business

development program, the Wisconsin Main

Street Program, and the Community

Development Investment (CDI) Grant

Program. For more information see the

WEDC’s website at https://wedc.org/

.

Wisconsin Housing and Economic

Development Authority (WHEDA)

WHEDA offers programs and services that

support business development within the

state, including loan guarantees,

participation lending and small business

credit initiatives.

Federal

The federal government has a variety of

grant opportunities (including community

development) to municipalities. The best