© 2020 International Monetary Fund

IMF Country Report No. 20/40

JAPAN

SELECTED ISSUES

This Selected Issues paper on Japan was prepared by a staff team of the International

Monetary Fund as background documentation for the periodic consultation with the

member country. It is based on the information available at the time it was completed on

January 14, 2020.

Copies of this report are available to the public from

International Monetary Fund • Publication Services

PO Box 92780 • Washington, D.C. 20090

Telephone: (202) 623-7430 • Fax: (202) 623-7201

E-mail: publications@imf.org Web: http://www.imf.org

Price: $18.00 per printed copy

International Monetary Fund

Washington, D.C.

February 2020

JAPAN

SELECTED ISSUES

Approved By

Asia and Pacific

Department

Prepared by a team led by Paul Cashin and Todd Schneider,

with individual chapters authored by Mariana Colacelli,

Takuma Hisanaga, Gee Hee Hong (all APD), Anh Thi Ngoc

Nguyen, Takuya Kamoshida, Siegfried Steinlein (all OAP),

Adrian Peralta-Alva (AFR), Mehdi Raissi (FAD), Niklas

Westelius (FIN), Yuko Hashimoto, Cyril Rebillard (both RES),

Sandra Lizarazo Ruiz (SPR), Kamiar Mohaddes, Xiaoxiao

Zhang (both University of Cambridge) and Yuki Yao

(University of Minnesota).

DISAPPEARING CITIES: DEMOGRAPHIC HEADWINDS AND THEIR IMPACT ON

JAPAN’S HOUSING MARKET ________________________________________________________ 5

A. Motivation ___________________________________________________________________________ 5

B. Demographics and Housing Prices in Japan __________________________________________ 6

C. Modeling Population Growth and Housing Prices ___________________________________ 8

D. Why are Japanese Moving to Large Cities? ________________________________________ 11

E. Policy Implications _________________________________________________________________ 12

References ____________________________________________________________________________ 15

BOX

1. Recent Developments in Residential Property Prices in Japan ______________________ 14

FIGURES

1. Population Change by Prefectures Between 1996-2015 ______________________________ 6

2. Household Statistics__________________________________________________________________ 7

3. House Price Change by Prefecture ___________________________________________________ 8

4. Population Growth and Housing Price Change _______________________________________ 9

5. Changes in House Price and Net Migration Flows __________________________________ 10

6. Education and House Prices ________________________________________________________ 12

CONTENTS

January 14, 2020

JAPAN

2 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

TABLE

1. Empirical Analysis of Land Price and Population Changes __________________________ 11

IS AUTOMATION THE ANSWER TO JAPAN’S DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES? ___ 16

A. Motivation _________________________________________________________________________ 16

B. Framework of Analysis _____________________________________________________________ 17

C. Main Findings ______________________________________________________________________ 19

D. Conclusions ________________________________________________________________________ 21

References ____________________________________________________________________________ 23

JAPAN’S FERTILITY RATE ___________________________________________________________ 24

A. Introduction _______________________________________________________________________ 24

B. Overview of Japan’s Fertility Rate __________________________________________________ 25

C. Empirical Analysis: Data and Methodology_________________________________________ 27

D. Results _____________________________________________________________________________ 29

E. Policy Implications and Conclusions ________________________________________________ 30

References ____________________________________________________________________________ 32

FIGURE

1. Japan’s Fertility Rate–Stylized Facts ________________________________________________ 25

TABLE

1. Estimation Results of Total Fertility Rate by Prefecture, 2001–15 ___________________ 31

TWENTY YEARS OF INDEPENDENCE: LESSONS AND WAY FORWARD FOR THE

BANK OF JAPAN ____________________________________________________________________ 34

A. Evolution of the Bank of Japan’s Policy Objectives and Goal _______________________ 34

B. Unconventional Strategies to Reflate the Economy ________________________________ 35

C. Communication Strategies and Inflation Expectations _____________________________ 40

D. Lessons Learned and Way Forward ________________________________________________ 42

E. Conclusions ________________________________________________________________________ 46

References ____________________________________________________________________________ 48

FIGURES

1. Inflation and GDP Growth, 1998–2019 _____________________________________________ 36

2. Monetary Policy Operations, 1998–2019 ___________________________________________ 36

TABLES

1. Monetary and Financial Stability Objectives and Goals of Selected Central Banks __ 44

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

2. Publication of Forecasts and Risk Assessments by Selected Central Banks _________ 47

JAPAN’S BOOM IN INBOUND TOURISM ___________________________________________ 50

A. Introduction _______________________________________________________________________ 50

B. Development and Impact of Inbound Tourism _____________________________________ 50

C. Tourism Promotion Policies ________________________________________________________ 57

D. Determinants of Inbound Tourism _________________________________________________ 57

E. Conclusions and Policies ___________________________________________________________ 59

References ____________________________________________________________________________ 61

FIGURES

1. International Arrivals _______________________________________________________________ 51

2. Tourism Expenditure _______________________________________________________________ 52

3. Tourism Contribution, Growth and Jobs ____________________________________________ 53

4. Overnight Stays of Inbound Visitors in Prefectures _________________________________ 56

5. Tourism Impact at Regional and Prefectural Level __________________________________ 56

6. Government Efforts to Boost Tourism ______________________________________________ 58

TABLE

1. Determinants of Tourist Arrivals to Japan, 1996-2018 ______________________________ 59

ANNEXES

I. Tourists’ Spending and Composition (2018) ________________________________________ 62

II. 2016 Tourism Strategy _____________________________________________________________ 63

JAPAN’S FOREIGN ASSETS AND LIABILITIES: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE EXTERNAL

ACCOUNTS __________________________________________________________________________ 64

A. What Has Driven the Increase in Japan’s Income Balance? _________________________ 64

B. How Does Japan’s Income Balance Compare to Peers? ____________________________ 66

C. Interconnectedness Between the Trade and Income Balances _____________________ 69

D. Does the Change in Current Account Composition Towards Income Balance Affect

its Responsiveness to the Real Exchange Rate? _______________________________________ 71

E. Conclusions ________________________________________________________________________ 73

References ____________________________________________________________________________ 75

FIGURES

1. Japan’s Increasing Income Balance and its Drivers _________________________________ 65

2. Geographical Allocation of FDI Assets, and Impact on Yields _______________________ 68

3. Negative Correlation Between Trade and Income Balances ________________________ 70

JAPAN

4 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

TABLES

1. Japan and G6 Income Balance – Contributions of Stocks and Yields _______________ 67

2. Theoretical Effects of REER Appreciation on Trade and Income Balances __________ 72

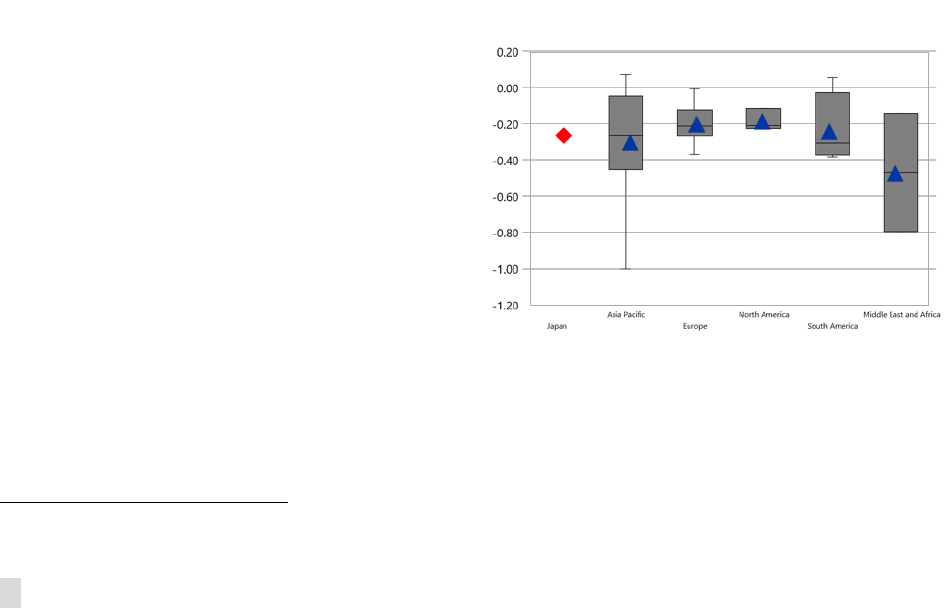

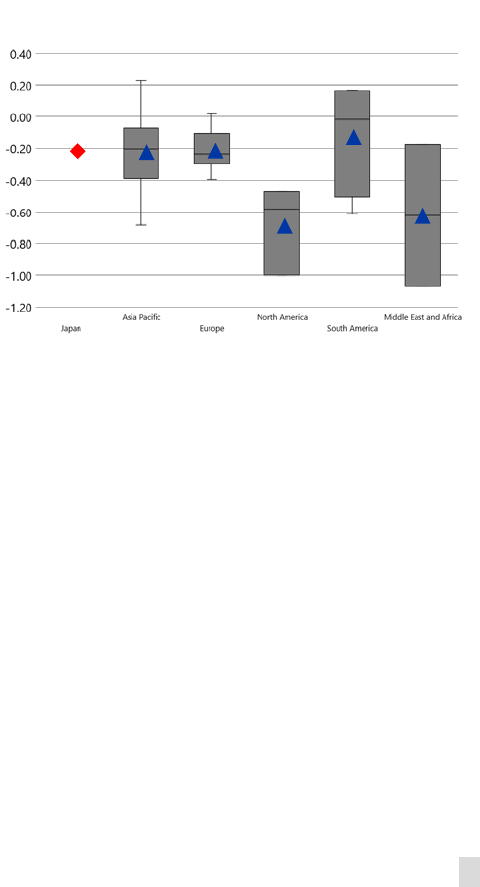

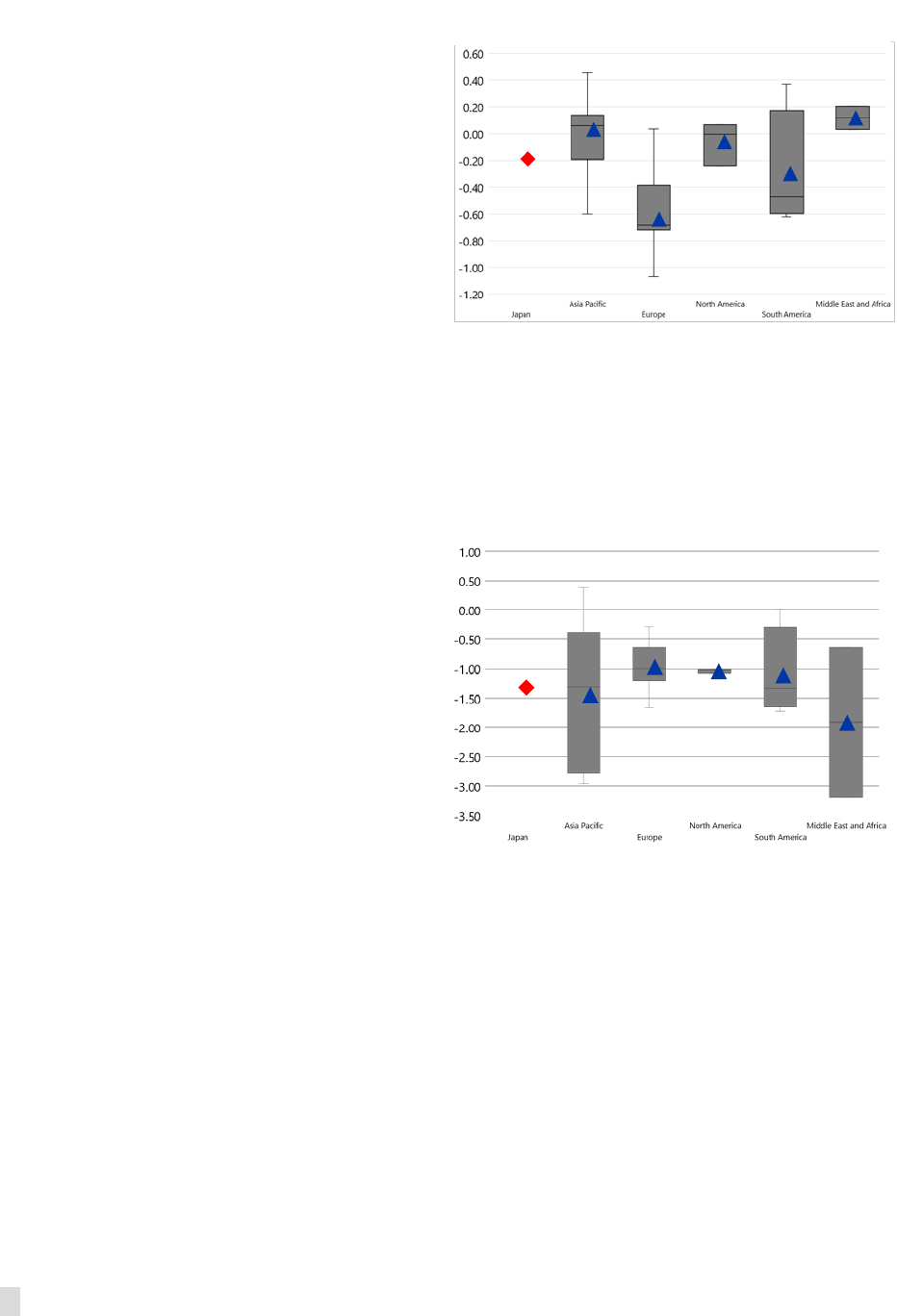

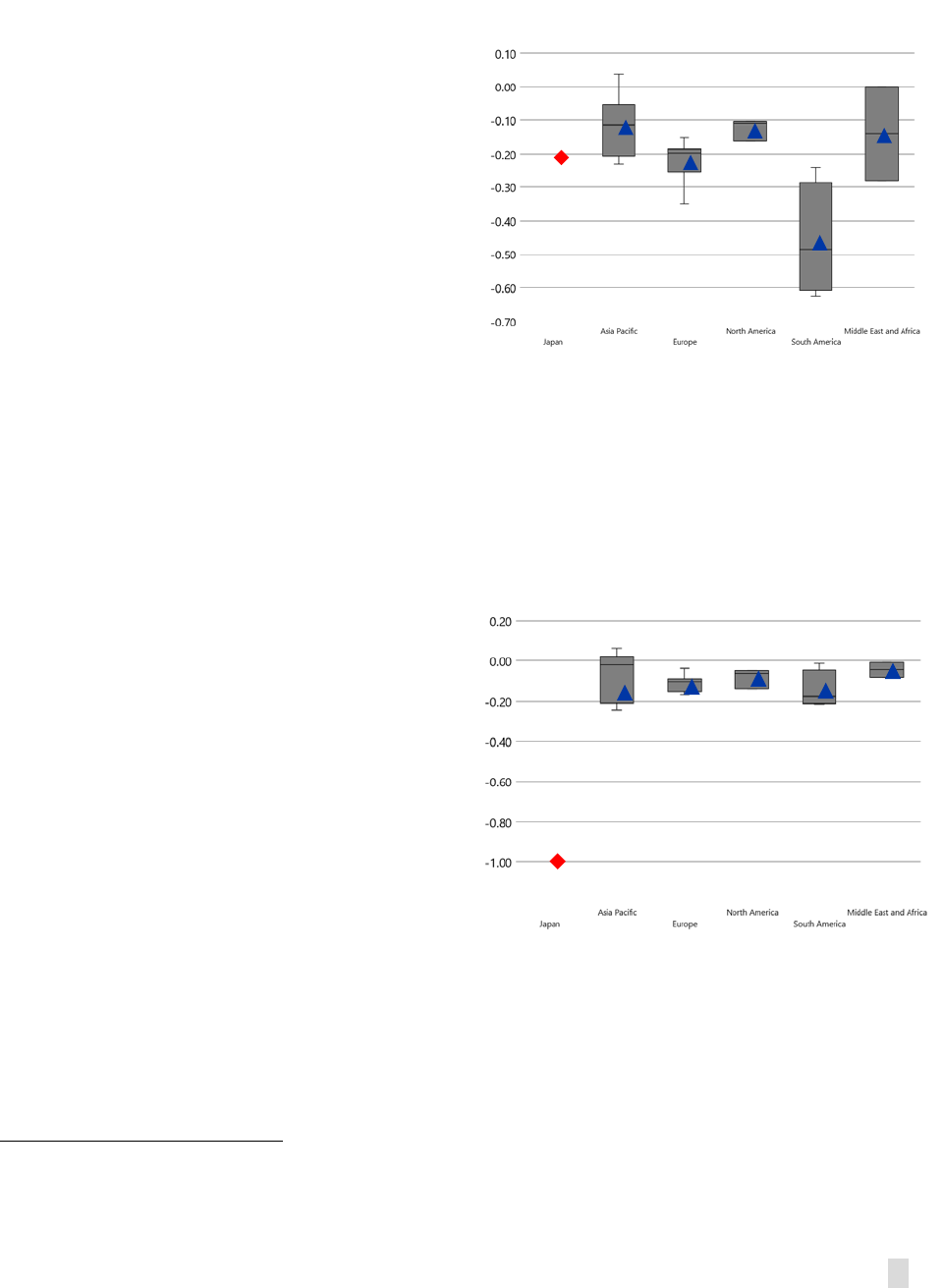

JAPANESE BUSINESS CYCLES, EXTERNAL SHOCKS, AND SPILLOVERS ___________ 77

A. Introduction _______________________________________________________________________ 77

B. Modelling the Global Economy ____________________________________________________ 78

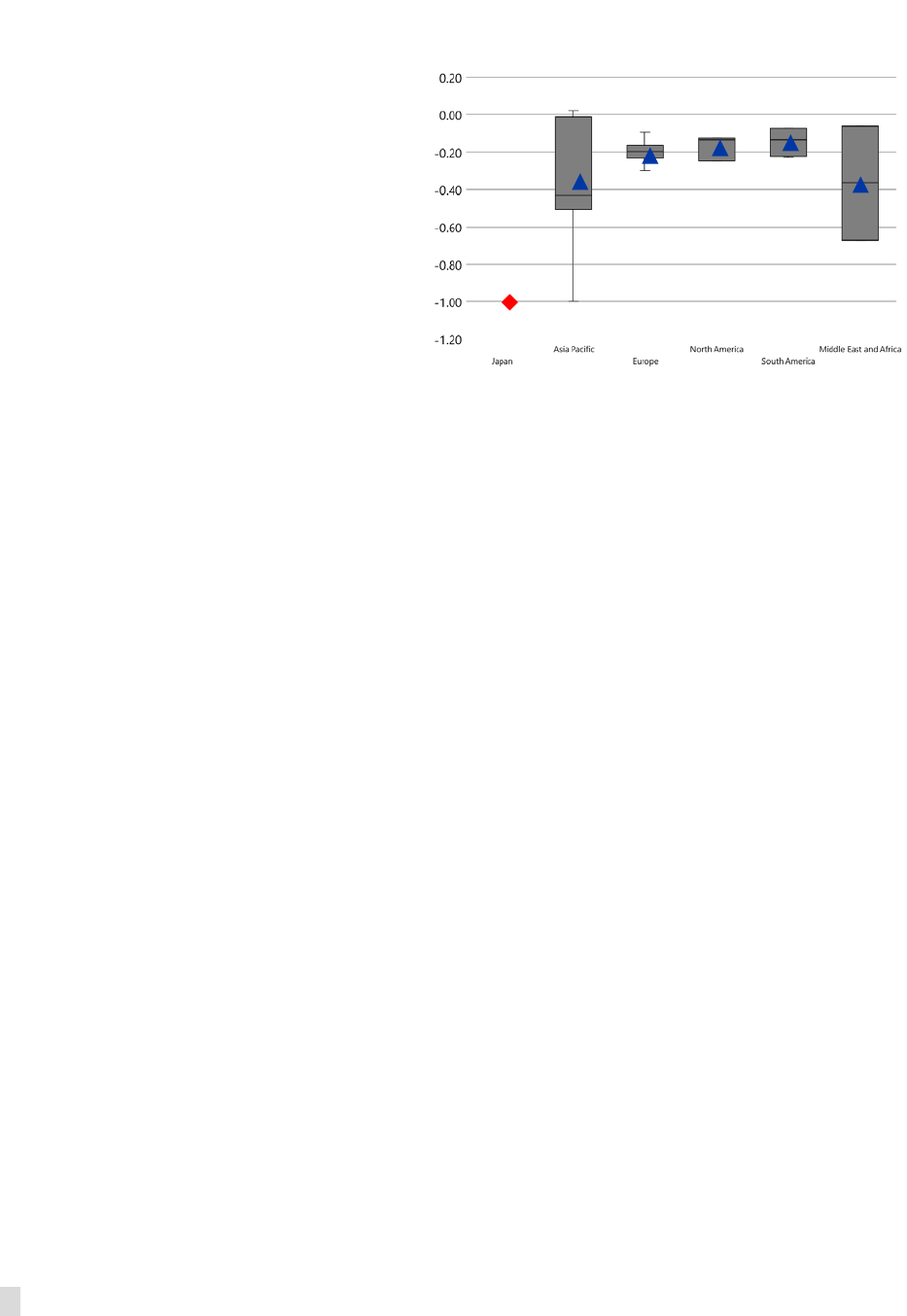

C. Spillover Analysis __________________________________________________________________ 80

References ____________________________________________________________________________ 85

TABLE

1. Countries in the GVAR Model ______________________________________________________ 79

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 5

DISAPPEARING CITIES: DEMOGRAPHIC HEADWINDS

AND THEIR IMPACT ON JAPAN’S HOUSING MARKET

1

Japan’s population is rapidly aging and shrinking, and doing so unevenly across regions. Large cities,

notably the Greater Tokyo area, are experiencing net migration inflows, while other regions are

experiencing net migration outflows. In this chapter, we assess the regional differences in population

dynamics and their implications for house price developments in Japan. Due to the durability of housing

compared to other forms of investment, the magnitude of house price declines associated with

population losses is larger than that of house price increases associated with population gains. These

model-based predictions are likely to underestimate the actual fall in house prices associated with future

population losses, as expectations of lower housing prices in the future could trigger more population

outflows and disposal of houses, especially in rural areas. We suggest policy measures to help close

regional disparities and avoid potential over-investment by taking account of demographic trends for

housing supply.

A. Motivation

1. Japan is at the leading edge of global demographic change, facing not only a

shrinking, but also a rapidly aging population. According to official projections, Japan’s total

population will continue to decline, after reaching a peak in 2010. In addition to its shrinking

population, another demographic challenge for Japan is its aging population. The old age

dependency ratio (measured as old-age population as a share of working-age group) has been on

the rise—the ratio exceeded 40 percent in 2014 and is expected to accelerate, reaching above

70 percent in the next 50 years.

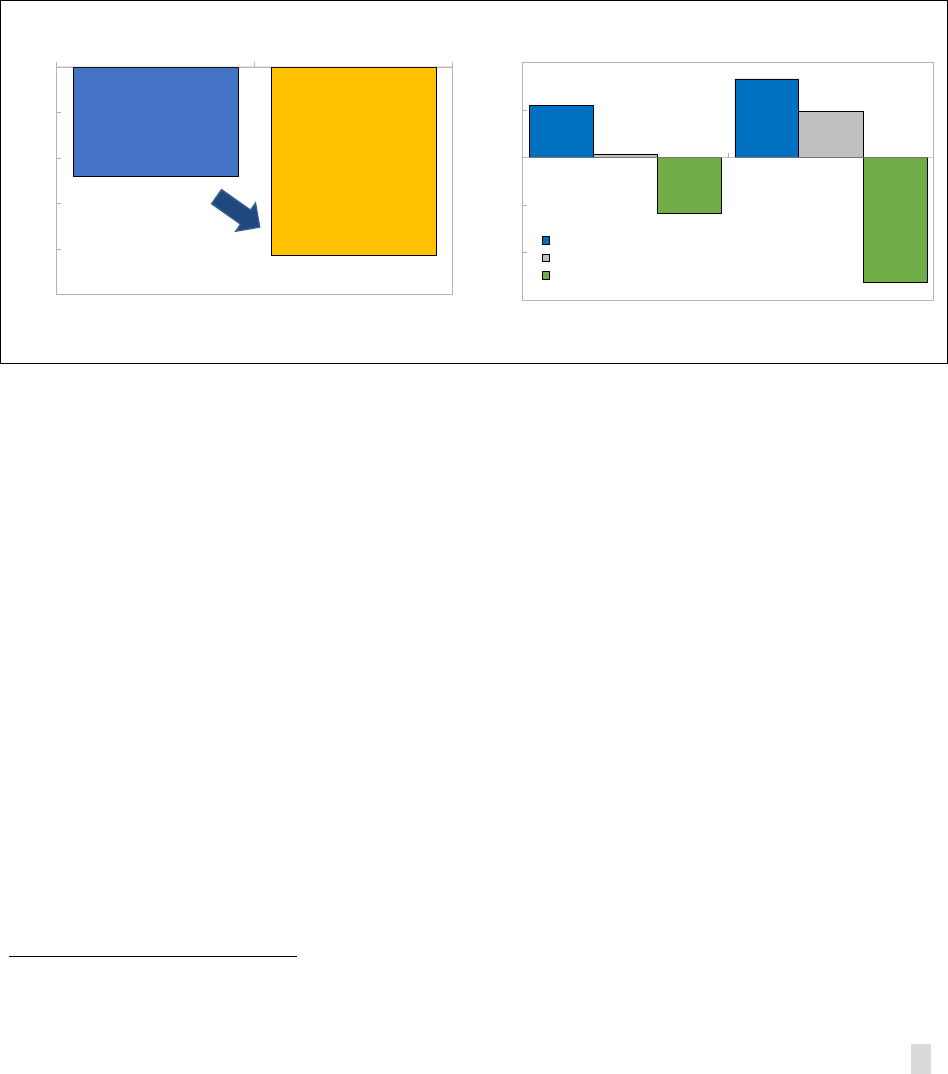

2. Rural areas are facing more adverse population trends than urban areas. Different

regions in Japan are experiencing the demographic transition (an aging and shrinking population) at

a different pace. Large cities, particularly the Greater Tokyo area, are experiencing net migration

inflows, driven by younger Japanese seeking education and jobs. For other regions of Japan,

population is declining and aging rapidly, as low fertility and outflows of the young exacerbate

adverse demographic trends. Altogether, the regional disparities are growing, led by the divergence

of demographic trends across regions.

3. Housing market and real estate prices are one important channel through which

demographics affect the macroeconomy. According to Japan’s National Survey of Family Income

and Expenditure of 2014, dwelling-related liabilities (purchase of house and/or land) consists of

about 75 to 90 percent of total household liabilities. In addition, land and real estate are strong

collateral for household and business lending. Therefore, a fall in housing prices has important

implications for household wealth and the health of household and bank balance sheets.

1

Prepared by Yuko Hashimoto (RES), Gee Hee Hong (APD), and Xiaoxiao Zhang (University of Cambridge).

JAPAN

6 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

4. This chapter assesses the relationship between demographic trends and housing prices

in Japan. Among various issues in the context of regional disparities, we focus on regional

differences in population dynamics to try and understand to what extent demographic trends have

influenced housing market prices in Japan in the past twenty years. First, we document how

demographic trends and housing prices have evolved over time across Japanese regions. Second,

we ask to what extent demographic trends are drivers of housing price dynamics in Japan and how

this relationship has evolved over time. We then look at the potential drivers of uneven population

growth across regions and offer policy recommendations to help address regional disparities in

housing price developments.

B. Demographics and Housing Prices in Japan

5. Japan’s declining and aging population generates an oversupply of houses,

particularly in rural areas. According to the Ministry of Infrastructure, Land, and Transportation,

nearly 13 percent of Japan’s total dwellings are vacant. These unoccupied houses are referred to as

“Akiya” and are sold for free (or at a negative price). In the next 15 years, the number of vacant

houses will increase to a staggering 21.7 million houses, or about one-third of total dwellings in

Japan. This phenomenon is observed in all parts of Japan, but particularly in rural areas, where the

population is shrinking at a faster pace than in urban areas.

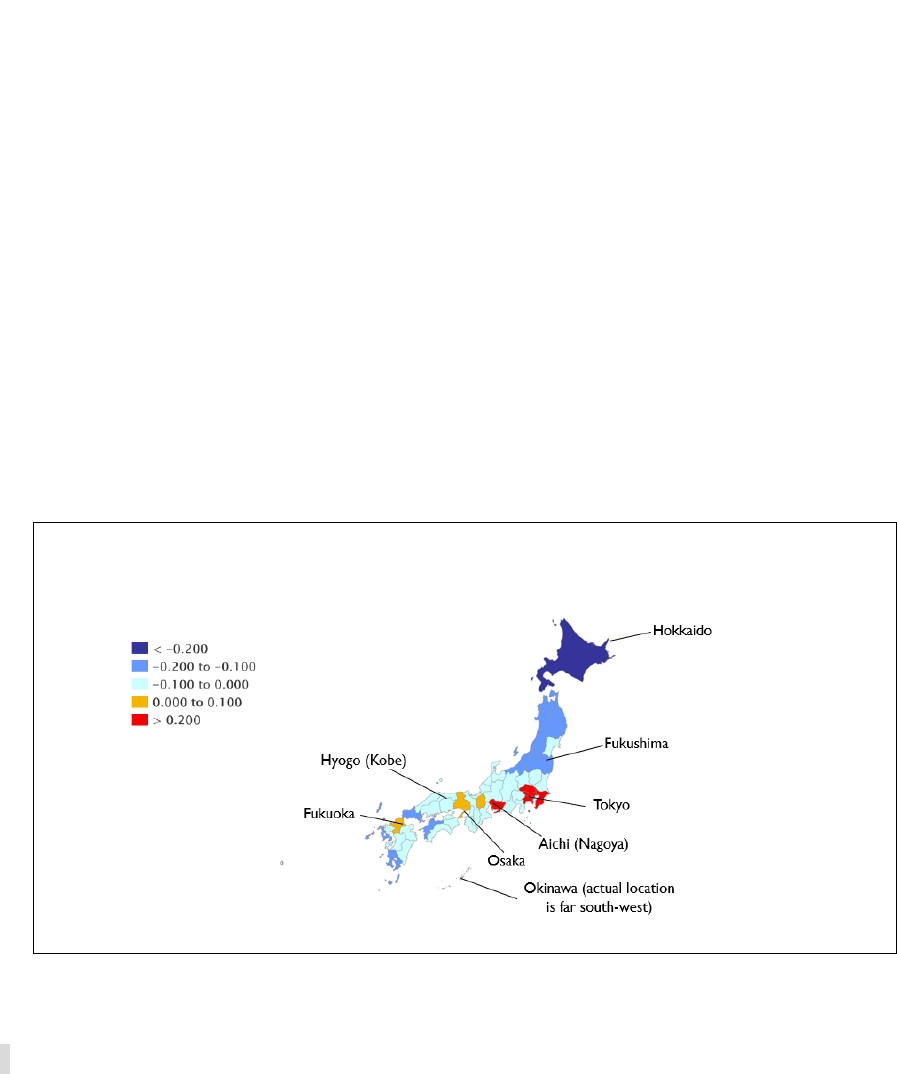

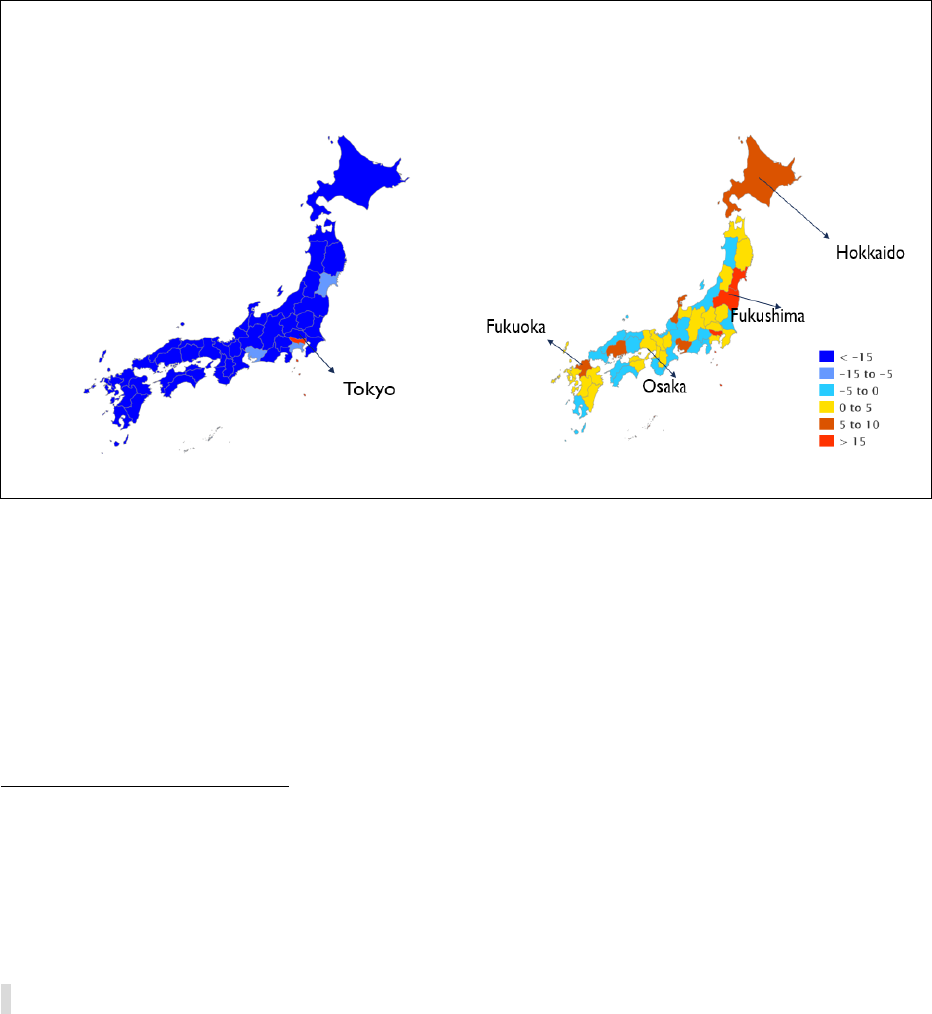

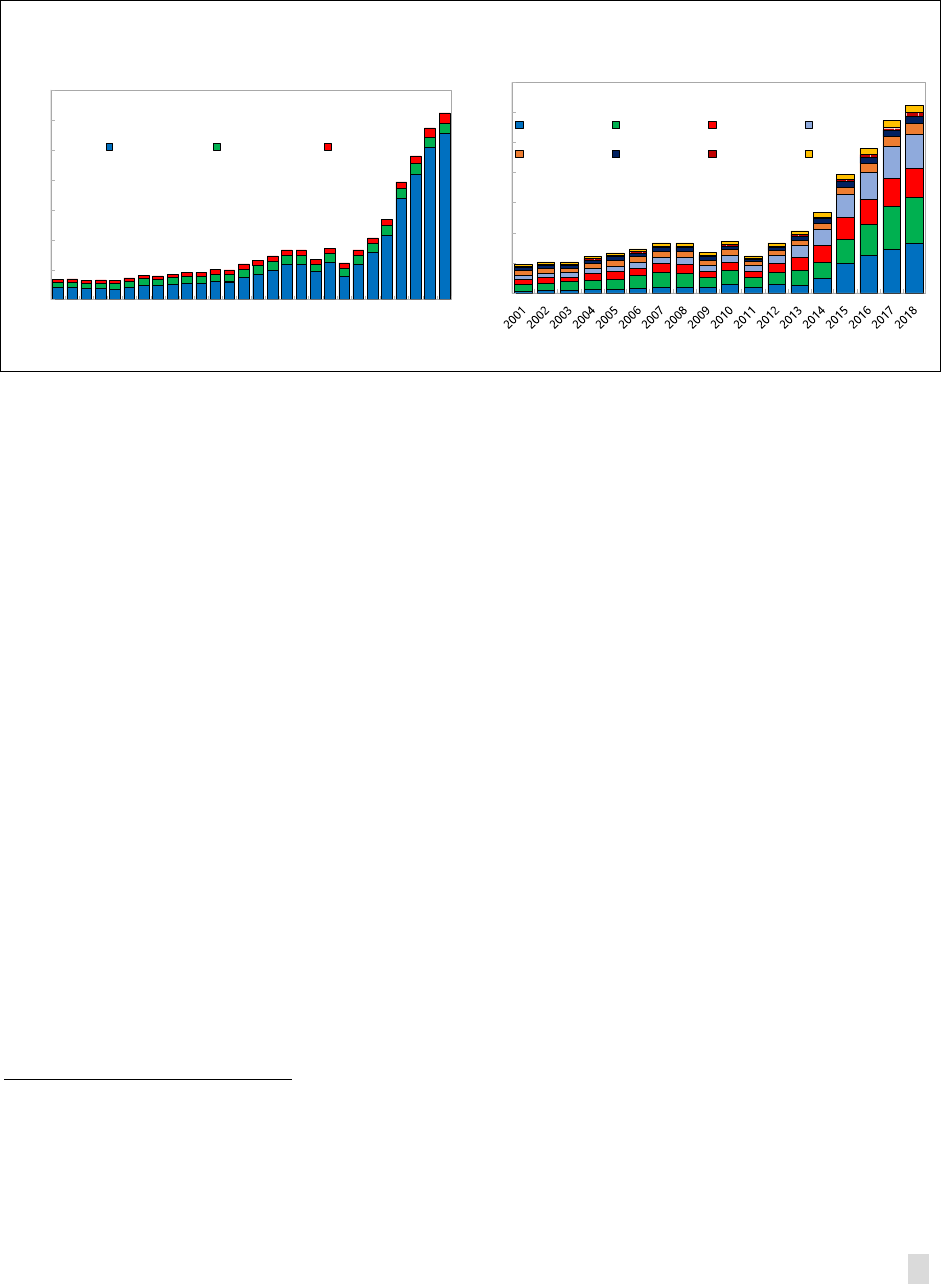

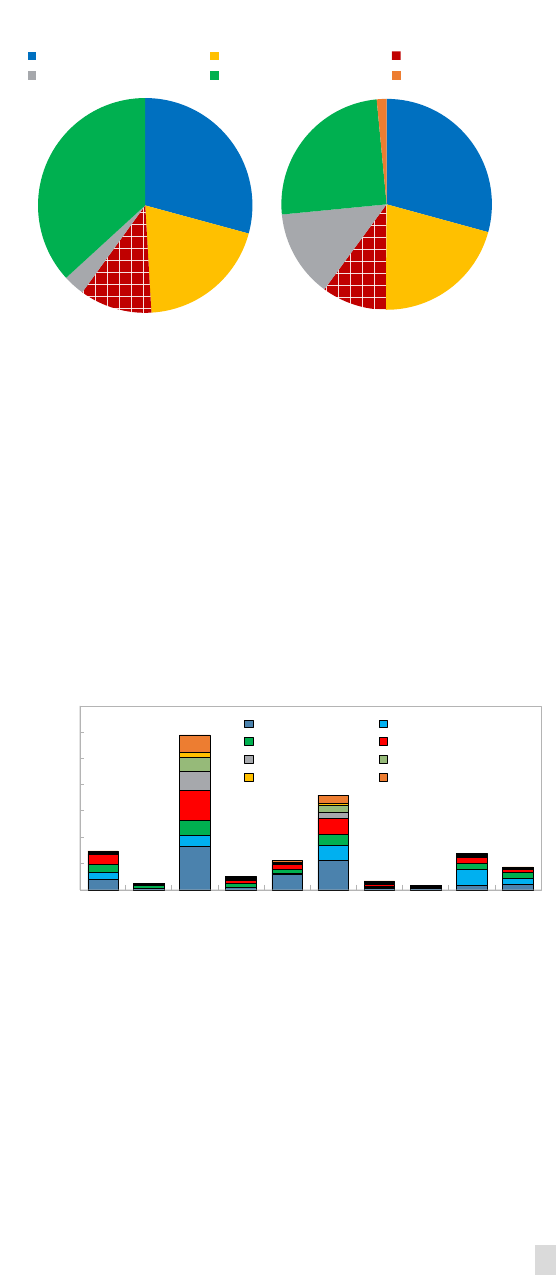

6. Japanese are moving to the four largest cities—Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya and Fukuoka.

Population change at the prefecture-level can be characterized by inflows of people into these cities.

In the past two decades, the population of the Greater Tokyo area, including Tokyo, Saitama, Chiba

and Kanagawa prefectures, grew by about 10 percent, while Hokkaido lost about 6 percent of its

population (Figure 1). As a result, prefecture-level population concentration increased in the four

cities, with Tokyo’s population increasing by the largest magnitude of 1.3 percentage points, and

Hokkaido decreasing by the largest magnitude of 0.3 percentage points.

Figure 1. Japan: Population Change by Prefectures Between 1996-2015 (in percent)

In the past two decades, population declined in rural areas, but concentrated in large cities.

Sources: Statistics Bureau of Japan, Cabinet Office

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

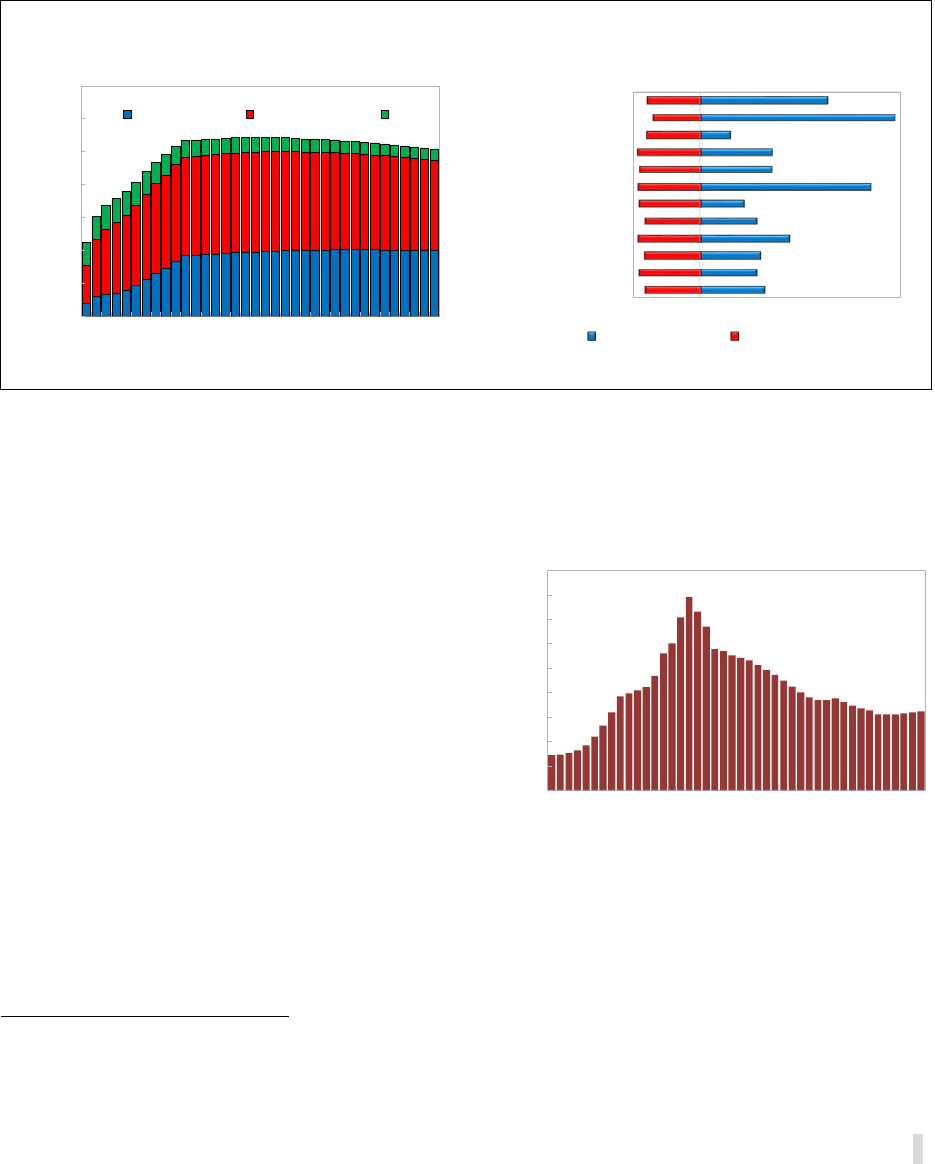

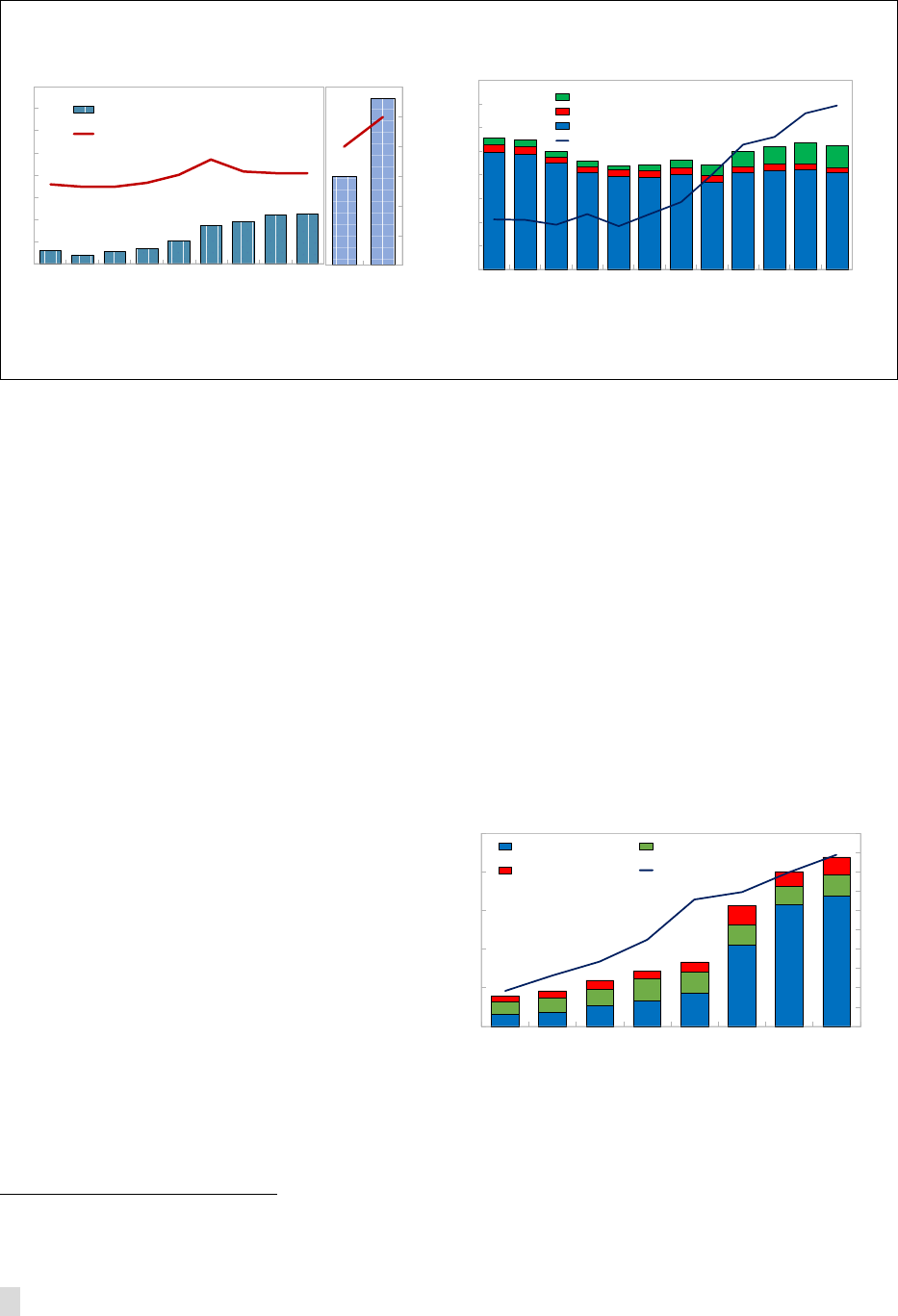

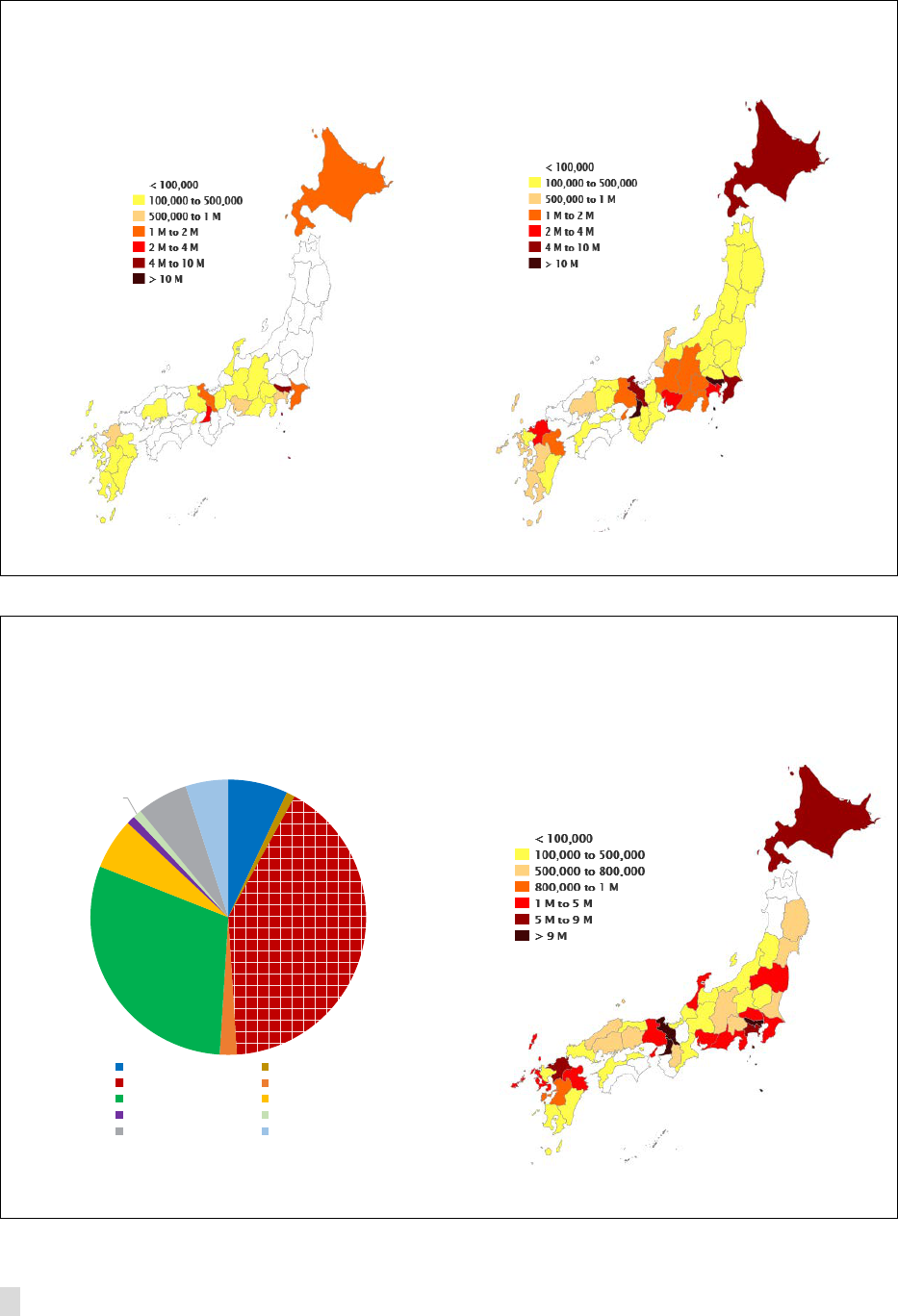

7. Despite the shrinking population, the total number of households in Japan has not

declined (see Figure 2). The number of households increased by 76 percent from 1970 to 2015.

During this period, the increase was greater for large cities (which increased by 116 percent) than for

rural areas (which increased by 18 percent). As a result, the total number of households in 2018

stands at around 50 million. However, the average size of a family has declined steadily, with an

increase in both the shares of the nuclear family and one-person family.

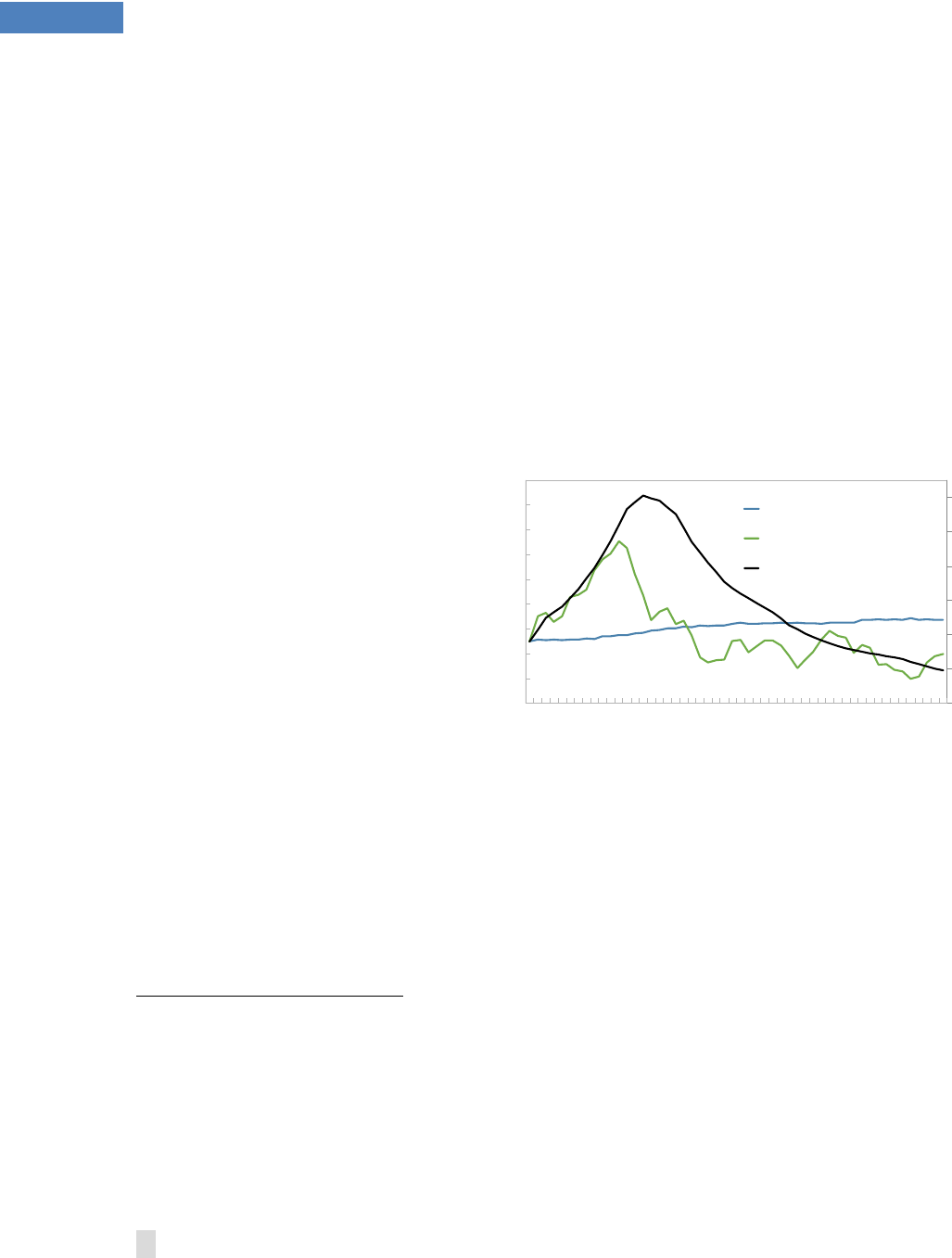

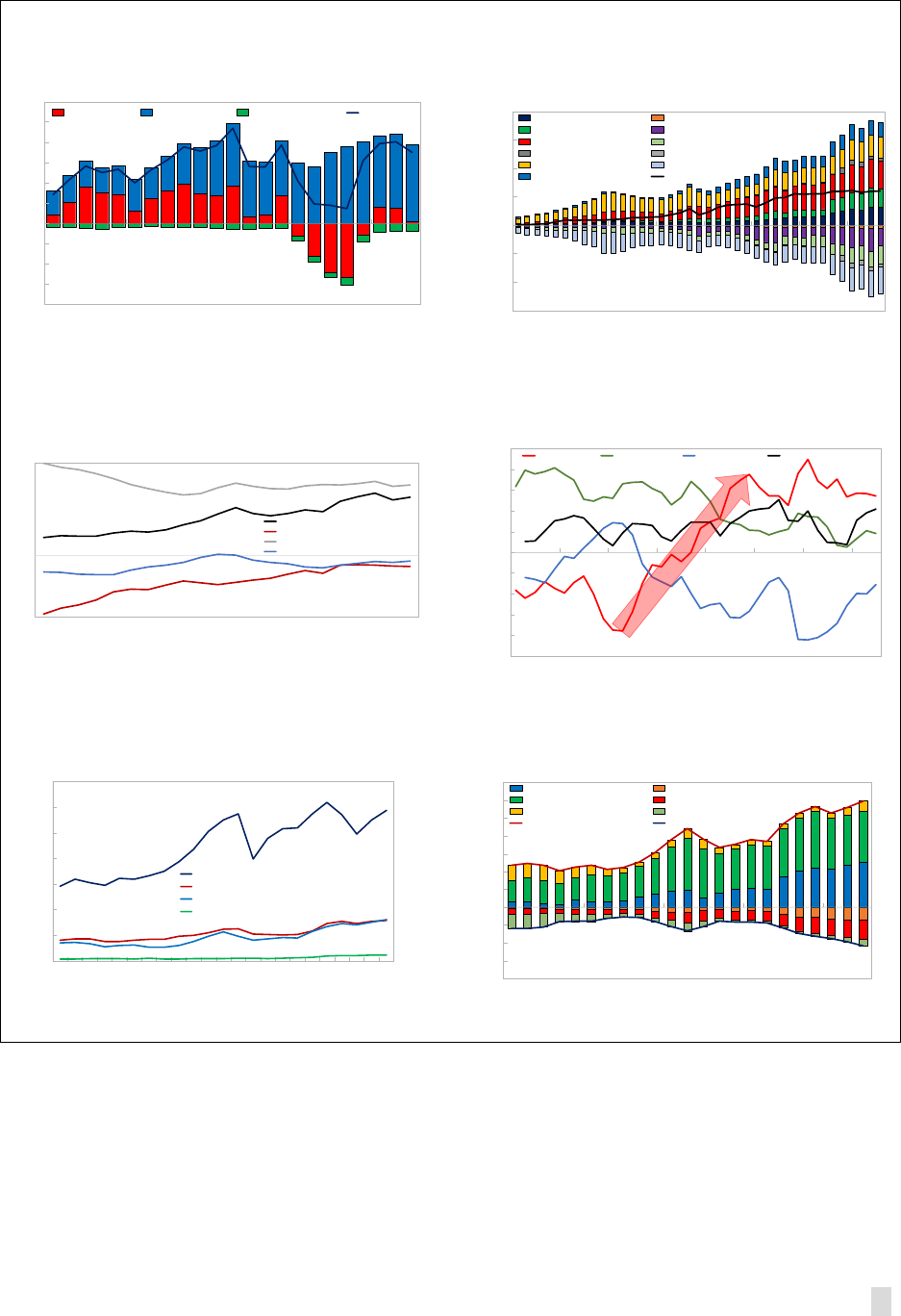

Figure 2. Japan: Household Statistics

8. Japan’s housing prices have gone through a large swing since the early 1990s.

2

Housing price movements in Japan can be grouped into five time periods: (1) pre-bubble period, (2)

post-bubble period until 2001, (3) mini-bubble between 2002–08, (4) pre-Abenomics and (5)

Abenomics period. With the economic expansion

experienced in the 1970s and 1980s, housing

prices in Japan increased until the years leading

up to the so-called ‘Bubble Period’ of the early

1990s. Beginning in 1988, price appreciation

intensified, increasing by 6 percent annually on

average. The bubble collapsed with a sharp

decline in housing prices until 1994. The price has

been on a declining trend since then, with a short-

lived period of a “Mini bubble (2002–08)”, and a

recent minor recovery in housing prices after

2014. Since the beginning of Abenomics, prices

have started to increase gradually (increasing by 2.7 percent since 2014 and by 0.7 percent in 2018).

With the recent increase in housing prices, they have recovered to the level last observed in 2013.

2

Throughout the chapter, with the exception of Box 1, residential land prices are used as a proxy for housing prices.

-40 -20 0 20 40 60 80 100 120

Japan average

Population concentrated area

Other areas

Aomori-ken

Iwate-ken

Miyagi-ken

Akita-ken

Yamagata-ken

Fukushima-ken

Yamaguchi-ken

Nagasaki-ken

Kagoshima-ken

Number of Households Family Members per Household

Japan: Households and Family Members

(Percent change between 1970 and 2015)

Source: Statistics Bureau of Japan.

0

10,000,000

20,000,000

30,000,000

40,000,000

50,000,000

60,000,000

70,000,000

1960 1980 1995 2010 2017 2020 2023 2026 2029 2032 2035 2038

One-person Nuclear family Other

Japan: Number of Households

Source: Statistics Bureau of Japan.

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

140,000

160,000

180,000

1975

1979

1983

1987

1991

1995

1999

2003

2007

2011

2015

Japan: Residential Land Price

(Yen/m

2

, Average Across Prefectures, Public Assessment Value)

Source: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism.

2018

JAPAN

8 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

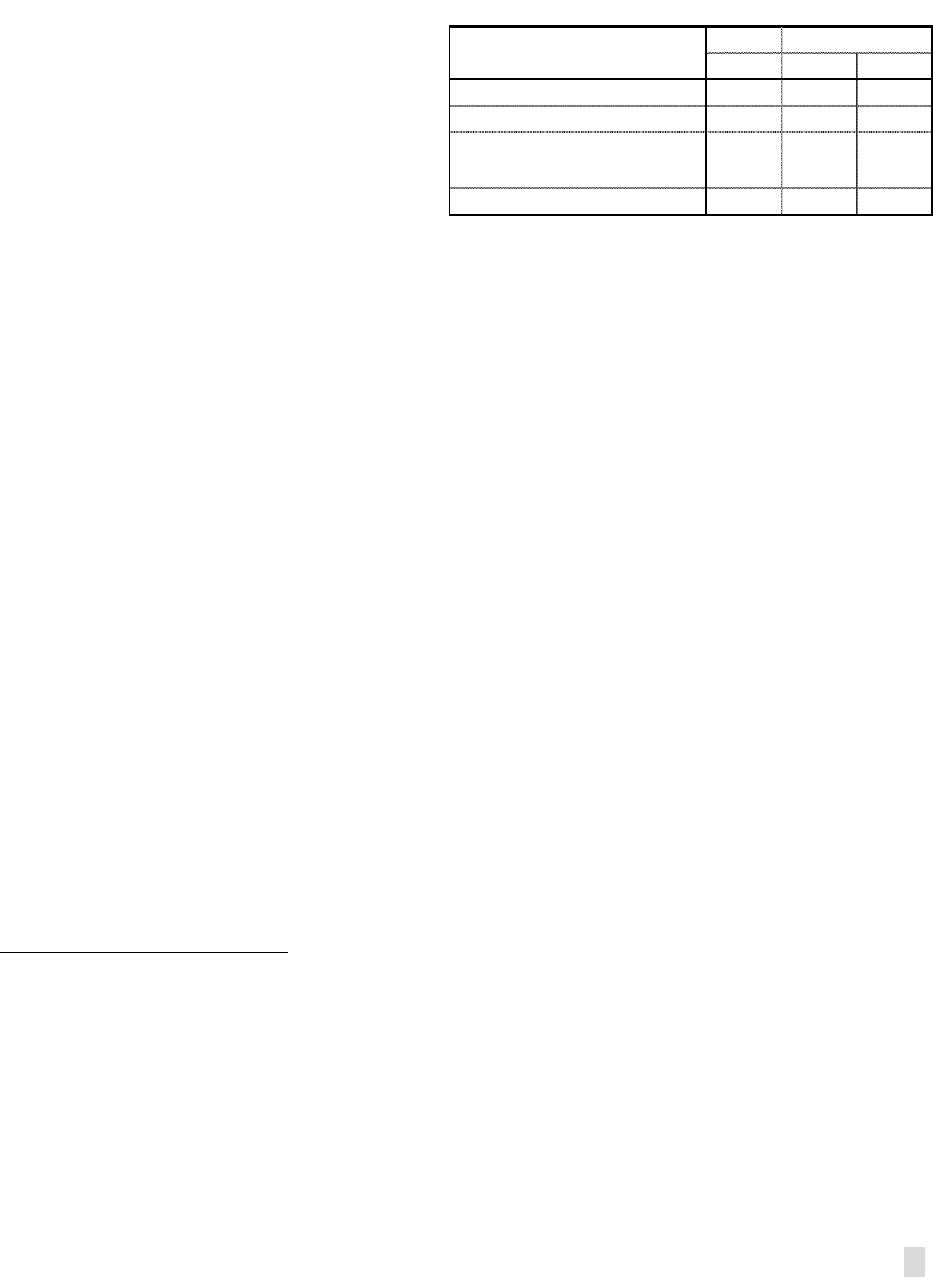

9. There is a clear regional dispersion in terms of housing price changes since the Bubble

Period burst in the early 1990s.

3

Figure 3 shows the growth rate of housing prices across

prefectures. The map on the left shows the price change since 2002, demonstrating that all

prefectures, except for Tokyo, experienced a decline in housing prices (by between -5 to -15

percent). The map on the right shows prefecture-level house price changes since 2014. Compared to

the left map, numerous prefectures experienced house price appreciation in recent years (average

1.9 percent nationwide since the beginning of Abenomics in 2013). The range, however, varies

greatly: largest gains are seen in Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures by 18 percent (likely related to

the reconstructions after the earthquake), followed by Tokyo (16 percent), while large losses are

seen in Akita (-6.5 percent), Shimane (-5.5 percent) and Yamanashi (-4.8 percent) prefectures. See

Box 1 for recent developments in housing prices in Japan and their potential drivers.

Figure 3. Japan: House Price Change by Prefecture

(in percent)

2002–2018: Tokyo-to is the only prefecture with an increase

in house prices since 2002.

2014–2018: Since 2014, an increase in house prices is

observed for other prefectures.

Source: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism.

C. Modeling Population Growth and Housing Prices

In this section, we assess the long-term relationship between population growth and housing prices

using prefecture-level data, motivated by the ‘durable housing’ model developed by Glaeser and

Gyourko (2005).

3

According to the National Survey of Family Income and Expenditure (2014, for two-person households), there is

great variation across prefectures as to how much household wealth can be explained by housing. With housing

accounting for an average of 66 percent of household wealth (nationwide, likely exaggerated as it focuses on two-

person households, who are likely to have a house), this is somewhat lower than other advanced economies – United

States about 70 percent, Spain, Greece, Italy around 80 percent. For Japanese prefectures, this ranges from 52

percent (Shinamane prefecture) to Tokyo (80 percent), and Okinawa (above 90 percent).

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

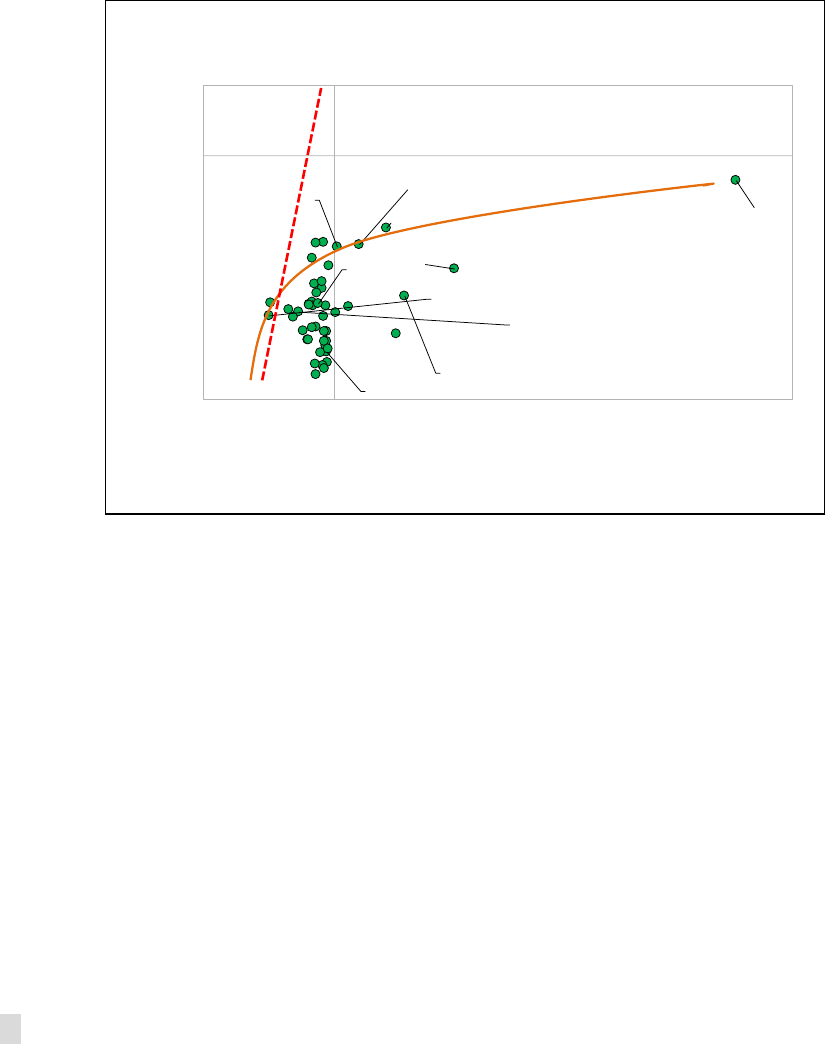

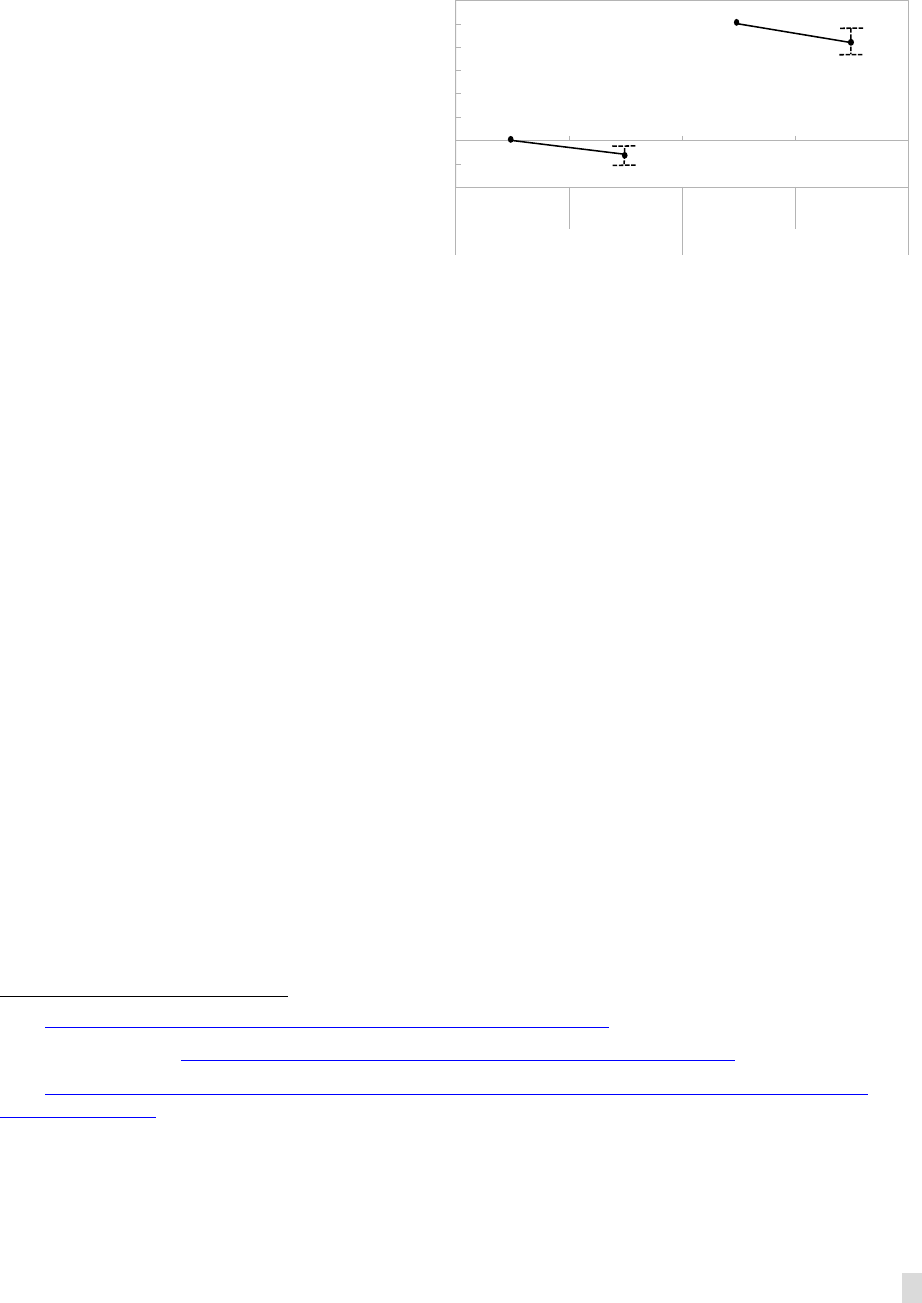

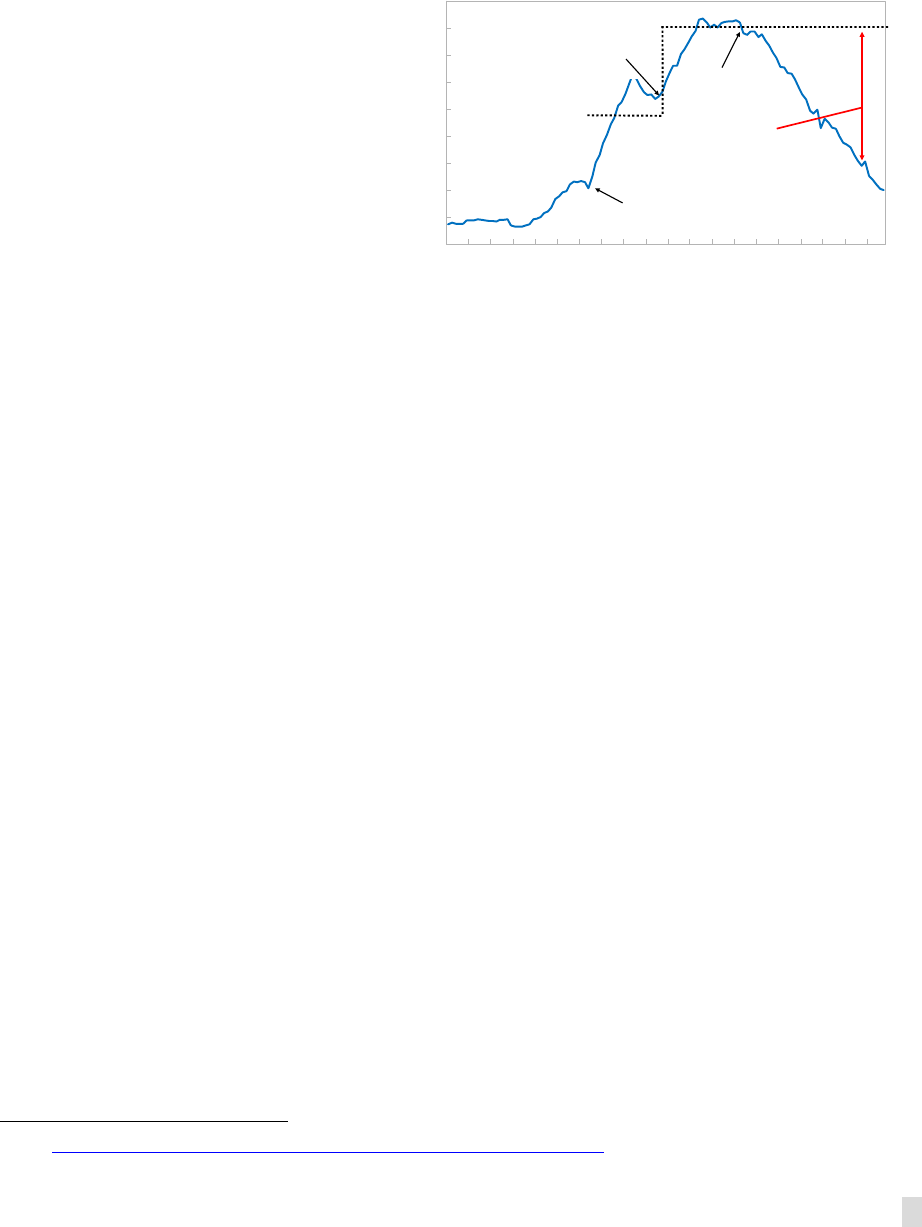

10. A simple durable housing model proposes a nonlinear relationship between changes in

housing prices and population growth. The non-linear relationship is that the magnitude of the

fall in housing price associated with population decline is larger than that of housing price rise from

population increase of the same magnitude. The ‘durable housing’ model by Glaeser and Gyourko

(2005) suggests that such an asymmetric relationship is due to the durability of housing, where

housing supply is elastic when new houses are built, while not elastic when houses need to be

demolished. This leads to a kinked supply-curve of housing. In this model, net inflows of population

increase demand for houses, and housing prices increase (P

2

). On the other hand, population

outflows of the same magnitude lower the demand for houses (P

3

), where the change in housing

price is larger than that with net inflows. If at the same time the supply of houses increases due to

sales by owners who move out from the region, a further decline in housing prices can be expected

(P

4

) (Figure 4).

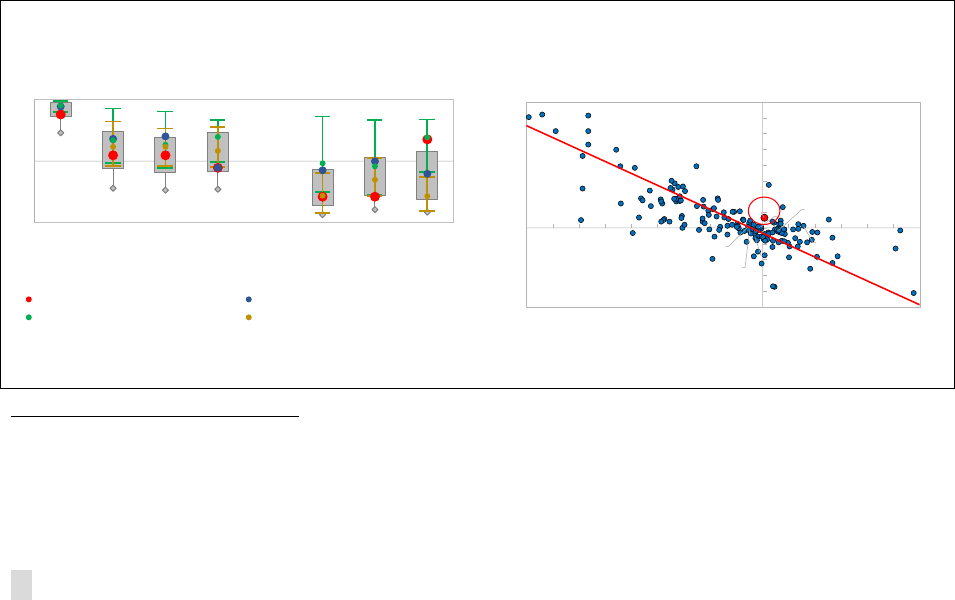

Figure 4. Japan: Population Growth and Housing Price Change

(Glaeser and Gyourko (2005))

D3

D1

Q

Source: Glaeser and Gyourko (2005).

Note: MPPC is minimum profitable production costs.

11. The theoretical model predicts that cities with negative population growth experience

a large decline in housing prices. Following Glaeser and Gyourko (2005), we run the following

regression:

∆P

i,t

= α+ β * POPLOSS

i,t-1

+ γ * POPGAIN

i,t-1

+ ε

it

,

where P is the publicly-assessed residential land price adjusted for inflation (in Yen/meter

) as a

proxy for housing prices; POPLOSS variable takes on a value of zero if prefecture i’s population grew

during period t and equals the prefecture’s actual percentage decline in population if the prefecture

lost population during the period. Similarly, POPGAIN variable takes on a value of zero if prefecture i

experienced population loss during period t, and equals the actual population growth rate if the

prefecture gained population. The expected signs of coefficients of β and γ are positive, and that β >

Population decline

Population growth

P* = MPPC

P

Q*

D2

P

3

P

2

S

S2

P

4

JAPAN

10 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

γ. This implies that a price decline is larger (β) for a given loss of population (POPLOSS <0) than a

price increase (γ) for a given population increase (POPGAIN >0). In order to account for the lagged

impact of population on housing price, we use POPLOSS and POPGAIN of t-1 in the regressions. We

also add the variables “old dependency ratio” and “vacancy rate” (both in percentage change with

one lag) to control for other factors that might affect demand for and supply of houses. Figure 5

shows a simple correlation between housing price change and net migration flows over the period

of 1996–2018. This simple correlation supports the prediction of non-linearity (orange line), as

housing price growth in Tokyo-to is much lower than what is predicted by the relationship between

the two variables in other prefectures (dotted red line).

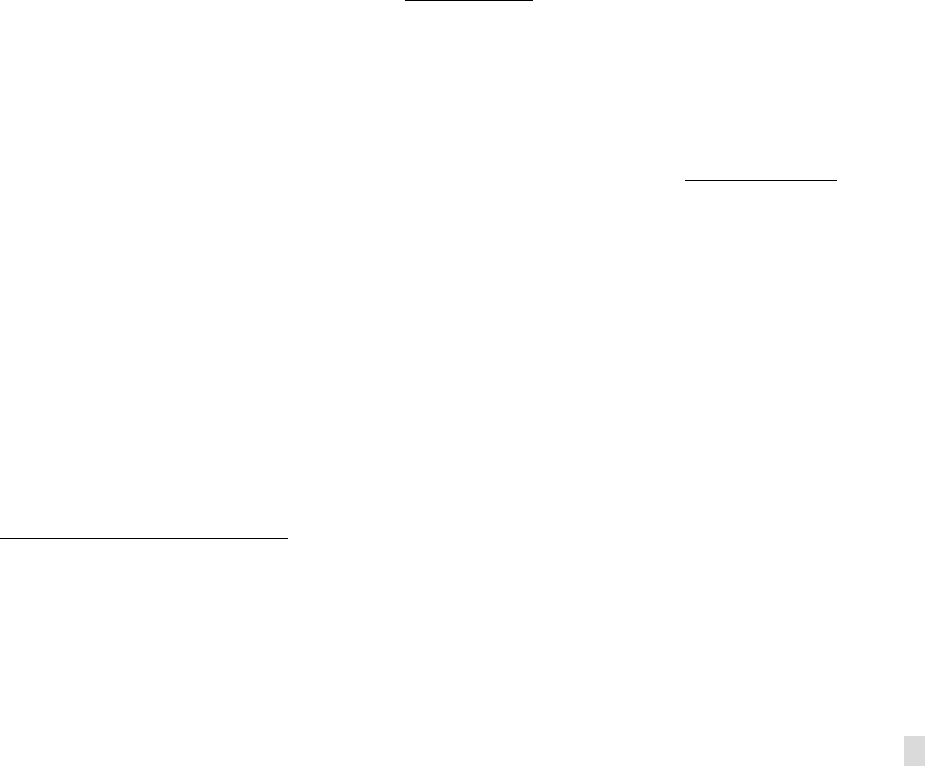

Figure 5. Japan: Changes in House Price and Net Migration Flows

(x-axis: thousands of persons, y-axis: percent, 1996-2018)

12. Panel regressions using prefecture-level housing prices and population dynamics

confirm this non-linear relationship. Table 1 shows regression results based on panel data of the

annual change in population and real land prices across three different time periods: (i) 1970–2015,

(ii) the past two decades since the collapse of the asset bubble, covering 1996-2015, and (iii) more

recent periods over 2010–15. Results show that during 1970–2015 (column 1), the estimated

coefficient for population loss is higher than that of population gain, confirming the prediction by

Glaeser and Gyourko (2005) that housing prices fall faster with declining population than they

increase with a growing population. However, in more recent periods, while the correlation between

housing price decline and population decline stays robust, the relationship between housing price

increase and population increase disappears. This confirms the overall decline in housing prices

across regions since the early-1990s bubble burst, regardless of the extent of population growth.

13. In reality, negative effects on housing prices from population decline may be even larger

than the model-based predictions. The results suggest a larger decline in housing prices associated

Hokkaido

Aomori-ken

Akita-ken

Gumma

-ken

Saitama-ken

Chiba-ken

Tokyo

-to

Kanagawa-ken

Aichi

-ken

Kyoto-fu

Osaka-fu

Fukuoka-ken

Okinawa-ken

-70

-60

-50

-40

-30

-20

-10

0

10

20

-20 -10 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

Change in House Prices

Average net migration flows (thousands of persons)

Source: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism.

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

with population loss than a housing price increase with the same size of population gain. The model,

however, does not factor in households’ expectations on future house price developments and their

potential impact on house prices. In fact, residents expecting a housing price decline may sell their

houses and have less incentive to own houses, which will add to already-existing oversupply of houses

and create further downward pressures on housing prices. This vicious cycle may lead to a larger decline

in house prices in regions with declining population more than the model-based predictions.

D. Why are Japanese Moving to Large Cities?

The proximate cause of regional disparities in population dynamics and related housing price

dynamics is the continuous inflow of population into large cities. This section explores several factors

that influence population concentration in large cities.

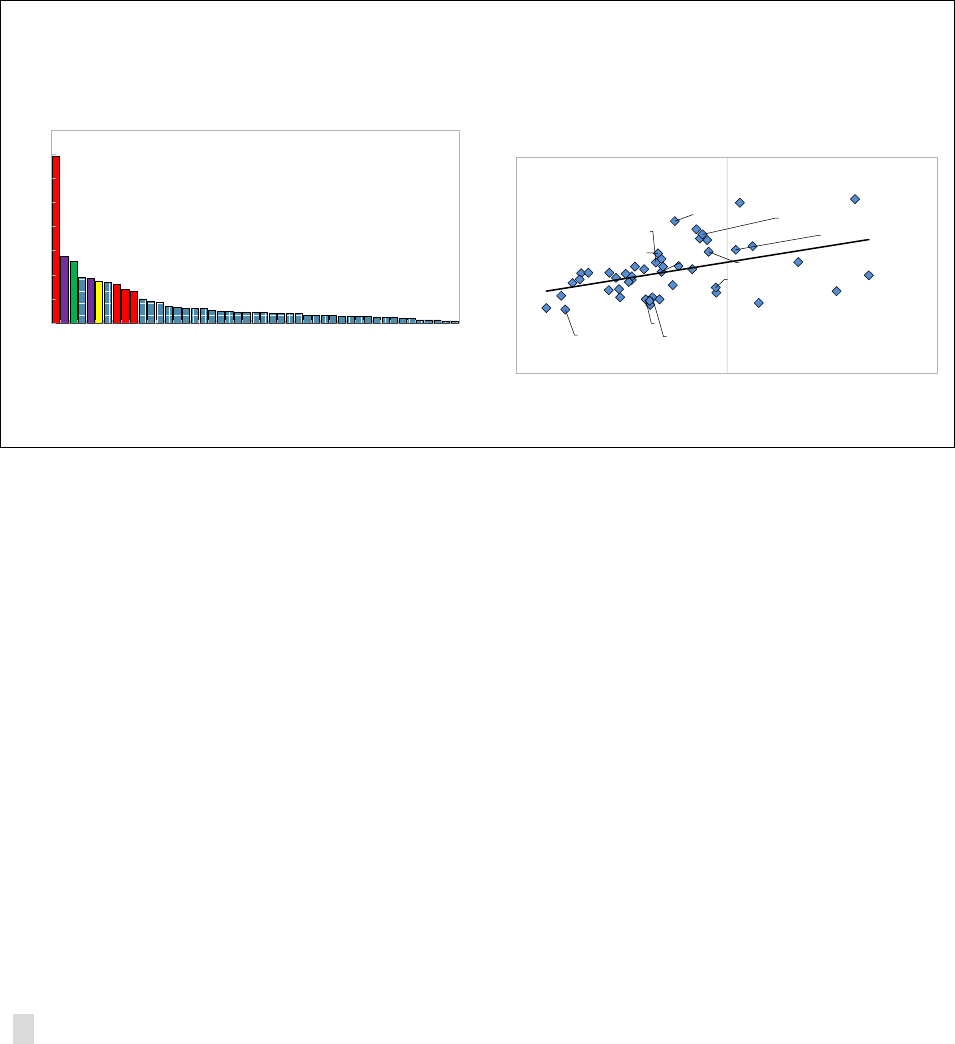

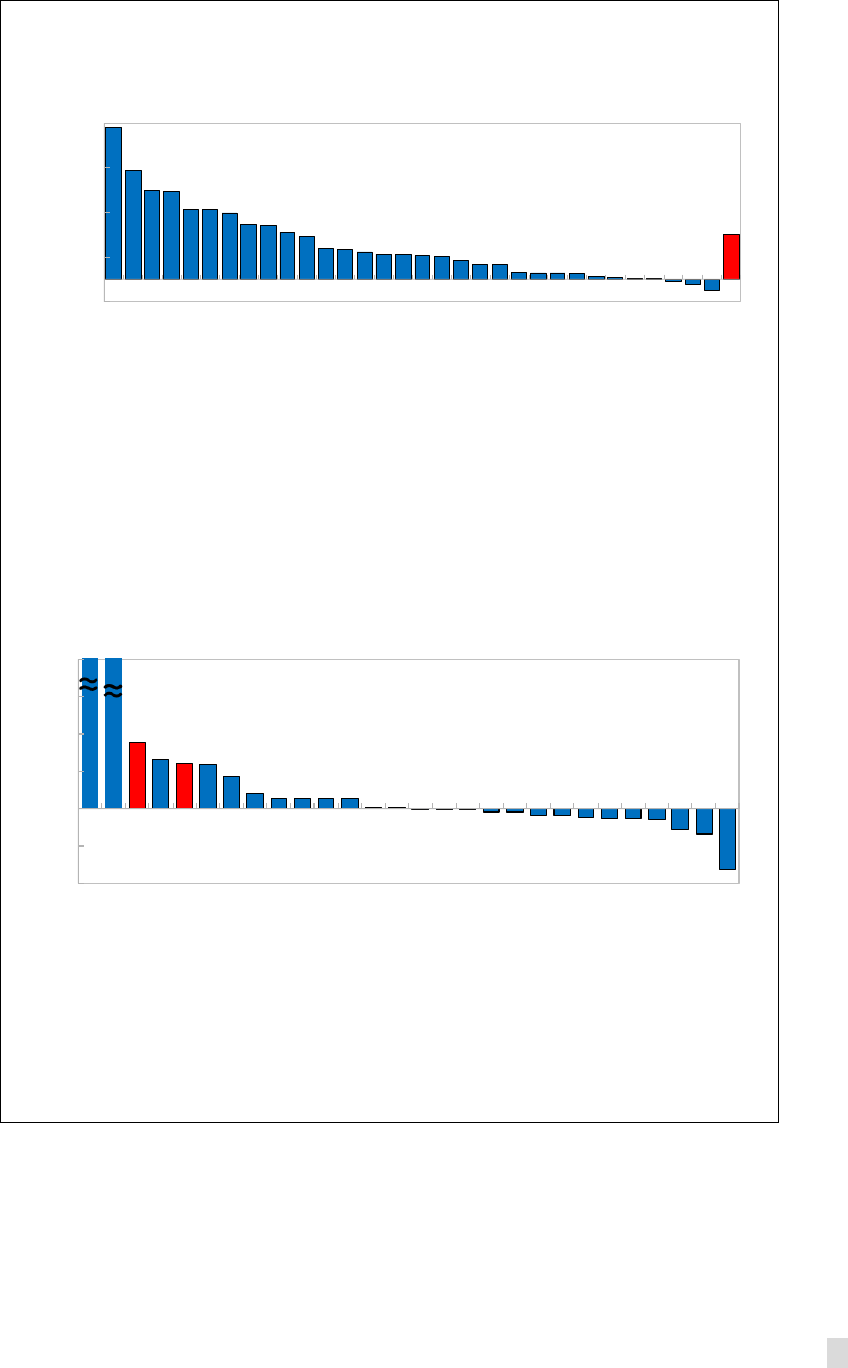

14. Large cities offer jobs and education for younger Japanese. There exists a large variation

across prefectures in terms of the share of population with higher education—for rural prefectures

such as Akita and Aomori, the share of population with university degrees or higher make up about

5 percent of the population. This contrasts with Tokyo or Kanagawa (a prefecture in the suburbs of

Tokyo) that has close to 20 percent of its total population with higher education (university degree

or above). The chart below shows that higher education opportunities are also far greater in large

cities (colored bars) than in others: this is one factor that underpins the younger generation moving

out from their home prefectures (Figure 6, left chart).

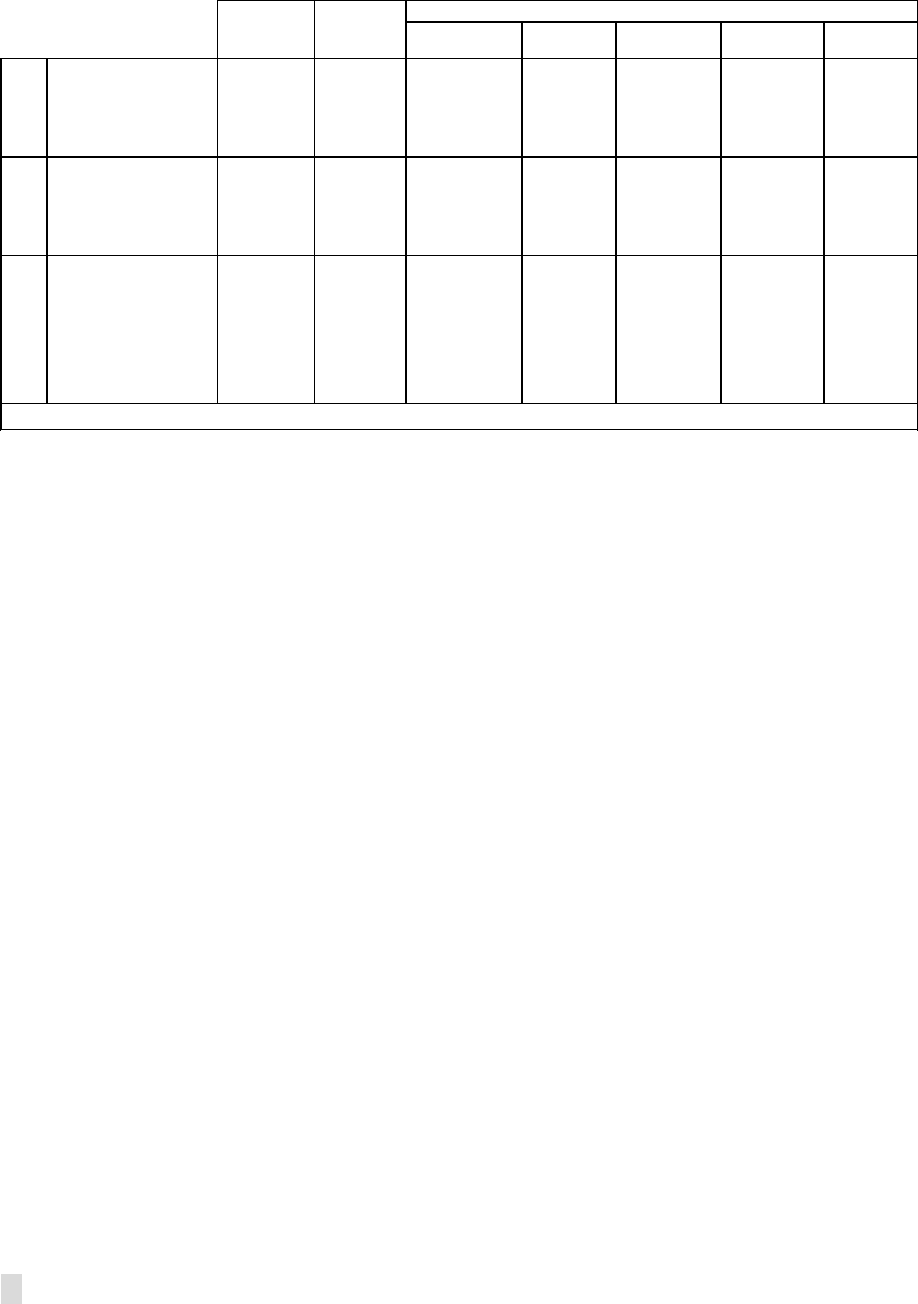

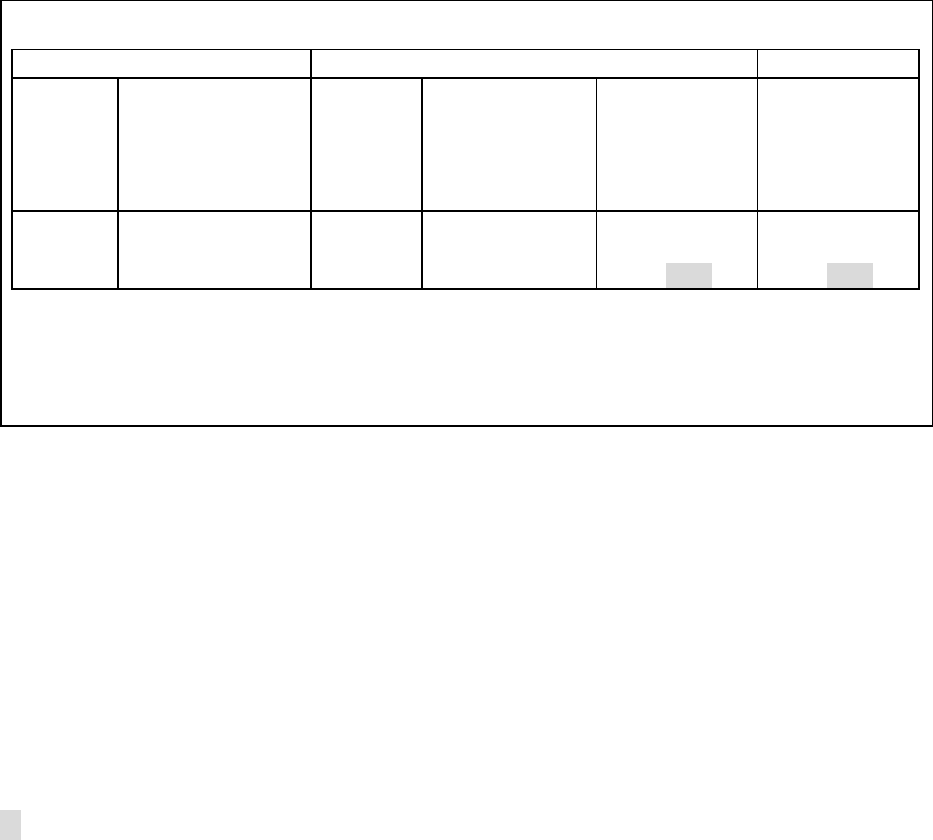

Table 1. Japan: Empirical Analysis of Land Price and Population Changes

VARIABLES

HHLOSS 5.961 12.44 15.77* - - - 24.01*** 23.85*** 23.92***

(4.446) (7.504) (8.005) (4.410) (4.235) (4.252)

HHGAIN 3.091*** 1.818** 3.011*** 7.004*** 3.785 7.700** 0.357 0.443 0.567

(0.783) (0.819) (1.097) (1.559) (2.321) (3.203) (0.797) (0.851) (0.809)

Δ ln OLDDEP -1.516*** -1.721*** -3.047** -5.279* -0.177 -0.165

(0.355) (0.391) (1.438) (2.641) (0.298) (0.317)

Δ ln Vacancy rate -0.305* -0.425 0.0400

(0.153) (0.268) (0.196)

Constant -0.145** 0.165* 0.727*** -0.427*** 0.244 0.938** -0.216*** -0.188*** -0.200***

(0.0606) (0.0961) (0.0984) (0.116) (0.356) (0.460) (0.0375) (0.0495) (0.0714)

Observations 376 376 329 188 188 141 141 141 141

R-squared 0.703 0.720 0.747 0.647 0.663 0.720 0.340 0.342 0.343

Number of code 47 47 47 47 47 47 47 47 47

Fixed effects Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y

Time effects Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y

Source: Authors' estimations.

Robust standard errors in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Dependent variable: %Δ real land price

1970-2015

1970-2000

2000-2015

JAPAN

12 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

15. Some studies show that skilled workers are better at generating growth in

endogenous amenities, increasing the value of housing (Shapiro, 2006; Glaeser and Saiz, 2004).

Service amenities, including health care and retail stores, are also concentrated in large cities. These

factors compose a core part of the local standard of living, and it is natural that people would prefer

to live in areas which have easy access to these amenities. For example, according to 2016 data of

social indicators by Statistics Bureau of Japan, the number of general hospitals (per 100 square

kilometers of habitable area) was 6 for Japan on average, of which the largest was 42.4 for Tokyo

and the lowest was 1.7 for Akita prefecture. Demand for amenities can explain the positive

correlation between housing price changes and the share of the educated population (Figure 6,

right chart), as affordability of these services increases with income.

Figure 6. Japan: Education and House Prices

Higher-education facilities are concentrated in four major

cities.

Housing price growth is positively correlated with the share of

the population with higher education qualifications.

E. Policy Implications

16. Policies to address regional disparities are crucial to prevent an excessive fall in

housing prices in rural areas. In 2014, the Abe administration established the headquarters for

regional revitalization in the Cabinet Office to promote even growth between rural and urban areas,

and help retain population and talents in rural areas. To assist rural areas, the government

introduced tax incentives for companies that either shifted their core functions or expanded the

operations of their headquarters already located in other parts of the country. Also, tax incentives

were provided to households who moved outside the capital area.

17. Forward-looking policies on housing supply and real estate investment that

incorporate demographic trends are necessary to prevent a further decline in housing prices.

Vacant houses create various social issues, but also have negative externalities in terms of prices, as

Hokkaido

Aomori-ken

Iwate-ken

Miyagi-ken

Akita-ken

Yamagata-ken

Fukushima-ken

Ibaraki-ken

Gumma-ken

Saitama

-

ken

Chiba-ken

Tokyo-to

Kanagawa-ken

Toyama-ken

Gifu-ken

Aichi-ken

Shiga-ken

Kyoto-fu

Osaka-fu

Hyogo-ken

Nara-ken

Shimane-ken

Okayama-ken

Hiroshima-ken

Kochi-ken

Fukuoka-ken

Nagasaki-ken

Kumamoto-ken

Okinawa-ken

0

5

10

15

20

25

-30 -20 -10 0 10 20 30

Japan: Human Capital and Housing Price Change

(X-axis: Change of Housing Prices Between 2011-2018, Y-axis: Share of University

and Graduate Degrees)

Source: Statistics Bureau of Japan; and IMF Staff Calculations.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

Tokyo-to

Osaka-fu

Aichi-ken

Hokkaido

Hyogo-ken

Fukuoka-ken

Kyoto-fu

Kanagawa-ken

Saitama-ken

Chiba-ken

Hiroshima-ken

Niigata

-ken

Okayama-ken

Miyagi-ken

Gumma

-ken

Ishikawa-ken

Gifu-ken

Shizuoka

-ken

Nara-ken

Aomori

-ken

Yamaguchi-ken

Ibaraki-ken

Toc h i gi -ken

Nagano-ken

Kumamoto-ken

Fukushima

-ken

Shiga-ken

Nagasaki-ken

Okinawa-ken

Akita-ken

Yamanashi

-ken

Mie-ken

Miyazaki-ken

Iwate

-ken

Yamagata

-ken

Fukui-ken

Kagoshima-ken

Toyama-ken

Ehime-ken

Oita-ken

Tokushima-ken

Kagawa-ken

Wakayama-ken

Tottori-ken

Kochi-ken

Shimane-ken

Saga-ken

Japan: Number of Colleges and Universities by Prefecture

Source: Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2017

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

the presence of vacant houses tends to bring down the value of other houses in the neighborhood.

4

A regional supply of housing that factors in future demographic trends would help avoid potential

over-investment in real estate, decrease the number of vacant houses, and help place upward

pressure on housing prices.

4

It used to be that the tax rate on land is reduced to one sixth of the appraised value if there remains a residential

structure on the land. The initial motivation for this regulation was to accelerate the high utilization of land by giving

an incentive to home construction during the years when the population grew. However, this tax incentive is one of

the causes of the high vacancy rate in Japan, as the owner of the property had an incentive to leave the property as

is, without demolishing the structure, to benefit from the lower property tax rate. New legislation was enacted in

2014 to accelerate the demolition of vacant houses.

JAPAN

14 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

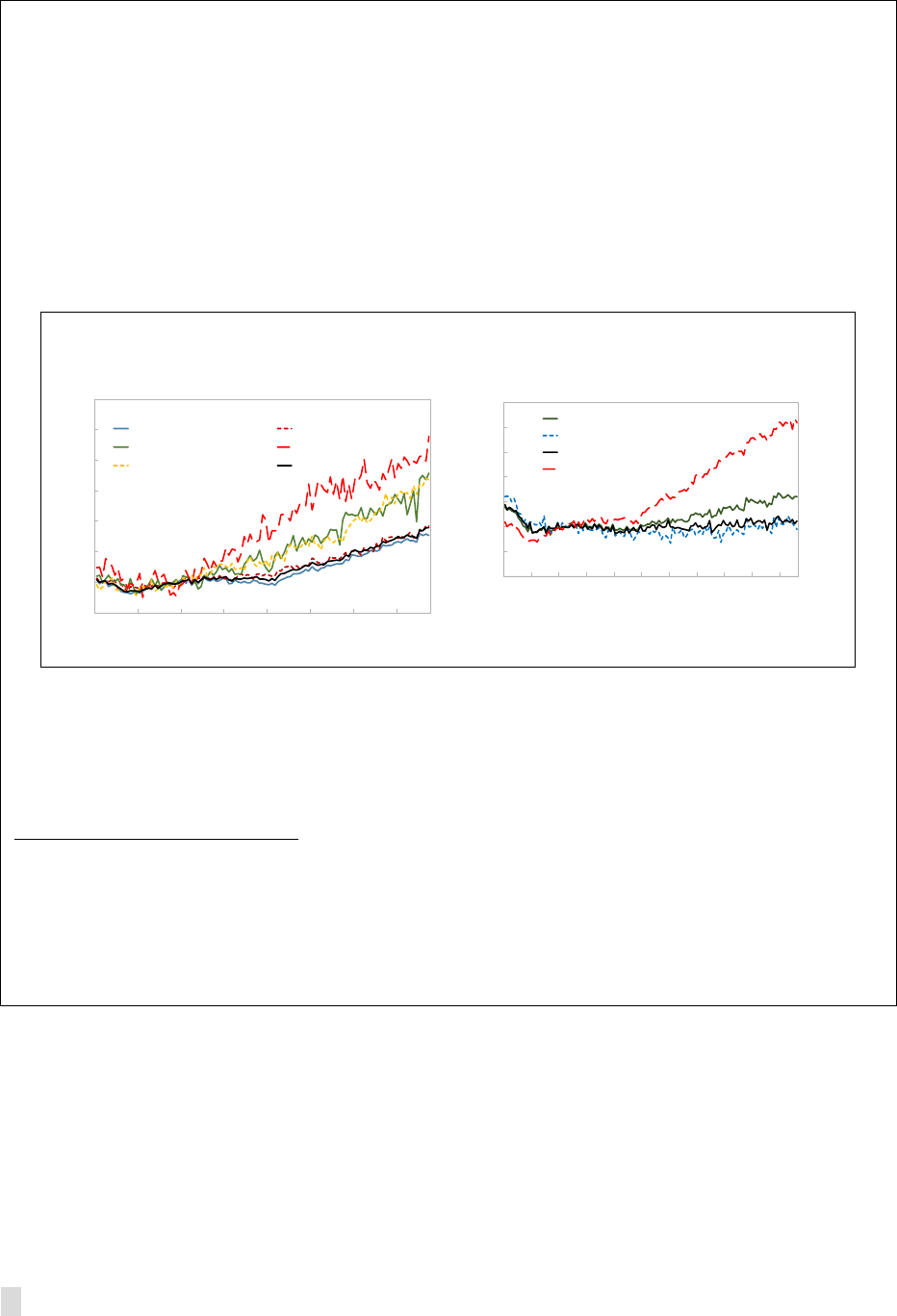

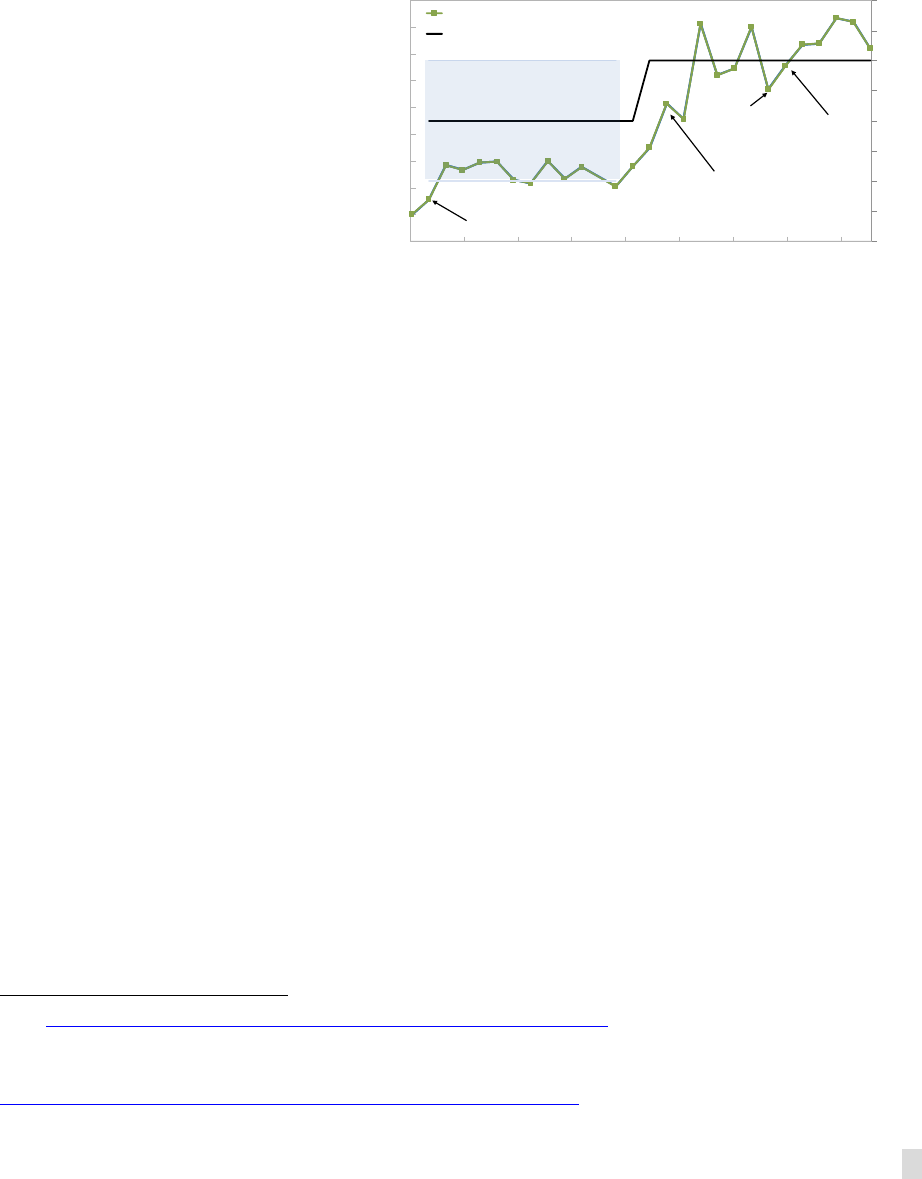

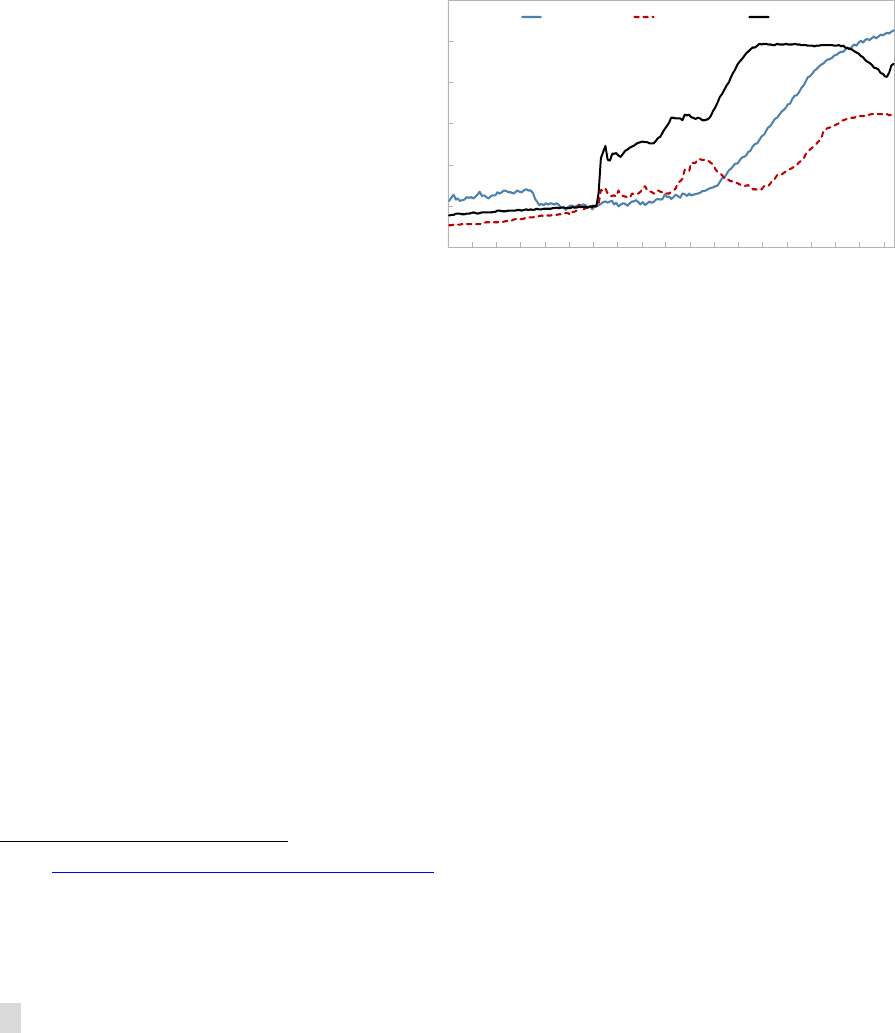

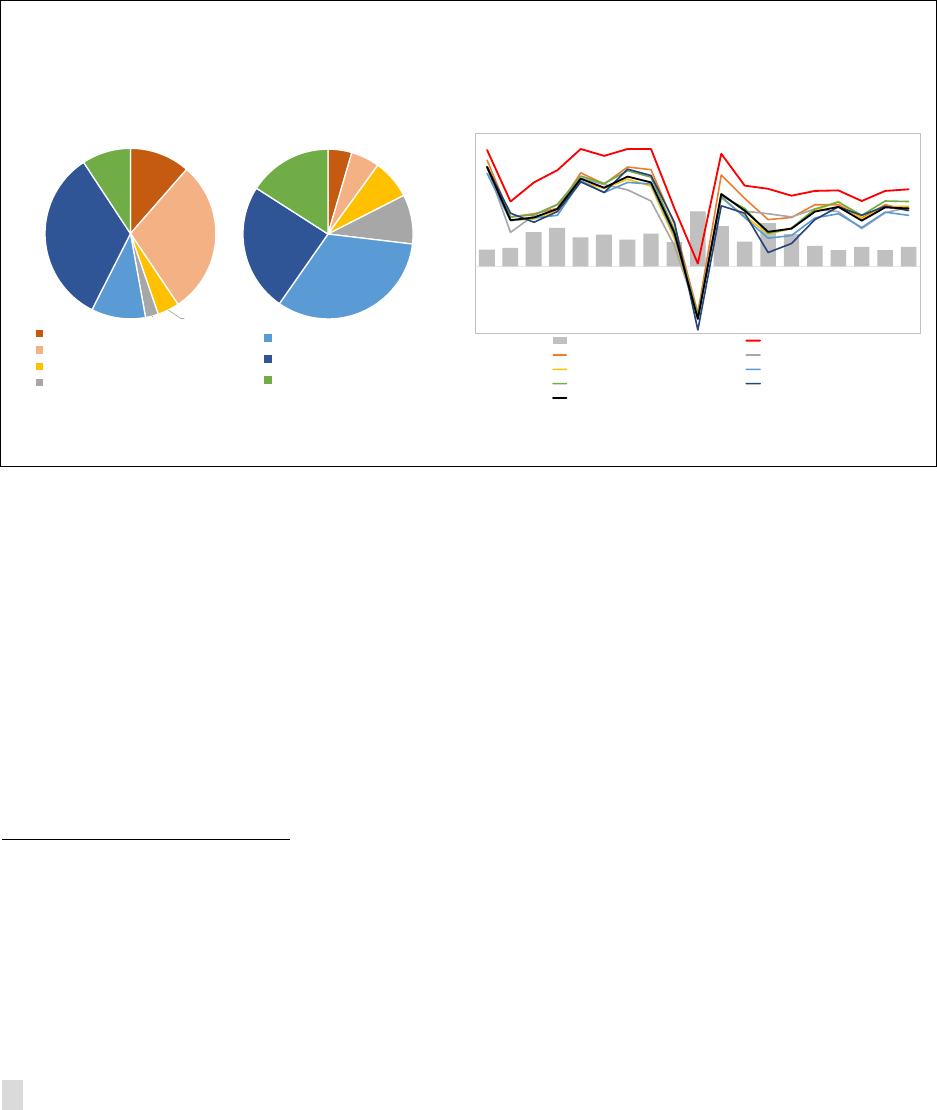

Box 1. Recent Developments in Residential Property Prices in Japan

Prices of high-rise condominiums in some Japanese cities have risen notably in recent years.

According to the annual survey of commercial and residential land price by the Ministry of Land,

Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, which was released in July, the national average of residential land

prices declined by 0.1 percent. However, prices rose in Tokyo, Osaka and Nagoya by 0.9 percent on the back

of solid demand for condominiums and offices.

Condominium prices have appreciated since the beginning of Abenomics in 2013. Prices of certain

types of housings in large cities and some tourist destinations have appreciated rapidly (text figure).

Condominium prices have increased by 23 percent at the national level since 2013. Prices for new

condominiums in the Greater Tokyo area in 2018 averaged ¥71.4 million (about $650,000), according to data

from the Real Estate Economic Institution.

1

Recent Developments in Japan’s Residential Property Prices

Potential drivers of property price appreciation are the ultra-low interest rate environment, an

increase in tourism, and the inheritance tax. The prolonged low interest rate environment incentivizes

Japanese banks, mostly serving domestic clients, to increase real estate lending. An influx of foreigners in

tourist destinations has also led to increased investment in real estate. Finally, demand for condominiums to

avoid the inheritance tax is also generating upward price pressures.

2

1

IMF (2017) concluded that condominium prices appear to be moderately overvalued in Tokyo, Osaka, and several outer regions,

exceeding the values predicted by fundamentals by 5 to 10 percent.

2

There is anecdotal evidence that valuations for tax assessment purposes make condominiums an attractive bequest compared

to financial assets, as condominium prices are evaluated below market value and financial assets are evaluated at market value.

So, there is a strong tax incentive for Japanese households to hold real estate and take out housing loans, since the latter is tax

deductible at market value if one is to carry out a bequest.

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

220

Apr-08 Jun-09 Aug-10 Oct-11 Dec-12 Feb-14 Apr-15 Jun-16

Tokyo including suburbs Osaka including suburbs

Hokkaido Tohoku

Kyushu-Okinawa Japan (nationwide)

Condominium Prices

(2010=100, NSA)

Source: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

150

2008 - Apr

2009 - Apr

2010 - Apr

2011 - Apr

2012 - Apr

2013 - Apr

2014 - Apr

2015 - Apr

2016 - Apr

2017 - Apr

2018 - Apr

Residential Property

Residential Land

Detached House

Condominiums

Residential Property Price Index

(2010=100, NSA)

Source: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

References

Glaeser, Edward and Joseph Gyourko, 2005, “Urban Decline and Durable Housing,” Journal of

Political Economy, Vol. 113 (2), pp. 345-75.

Glaeser, Edward and Albert Saiz, 2004, “The Rise of the Skilled City,” Brookings-Wharton Papers on

Urban Affairs: 2004, pp. 95-103.

International Monetary Fund, 2017, “Japan: Financial System Stability Assessment,” IMF Country

Report No. 17/244, Washington DC.

Shapiro, Jesse, 2006, “Smart Cities: Quality of Life, Productivity, and the Growth Effects of Human

Capital,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 88 (2), pp. 324-35.

JAPAN

16 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

IS AUTOMATION THE ANSWER TO JAPAN’S

DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES?

1

Japan’s demographic transition will pose grave challenges for fiscal sustainability under the current

social security system. At the same time, Japan’s shrinking and aging population is expected to worsen

inequality in terms of market income. Automation and artificial intelligence technology have been

seen as a potential answer to the macroeconomic issues generated by population aging, though it is

not clear to what extent the new technology will mitigate the impact of demographic change on

growth and income distribution. Simulation results from a calibrated multi-sector general equilibrium

overlapping generations model suggest that automation can potentially offset the impact of

population aging on real output, but cannot fully eliminate fiscal pressures arising from demographic

transition. Nonetheless, for an aging society such as Japan, automation may improve distributional

outcomes.

A. Motivation

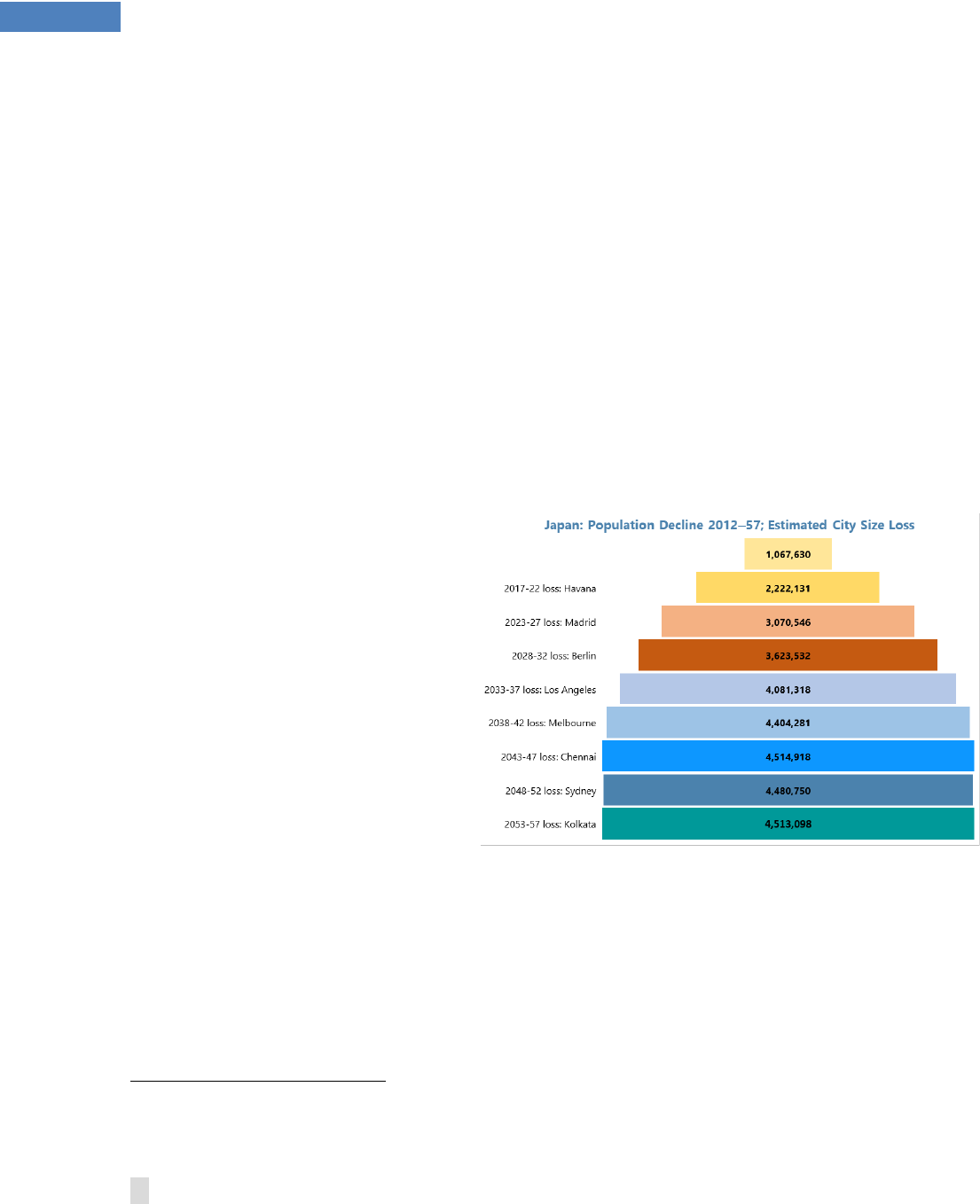

1. Adverse demographic trends in Japan have serious implications for its long-term

growth prospects and fiscal sustainability. Official projections anticipate that Japan’s population

will decline by 25 percent in the next 40

years. A rapidly shrinking and aging

population and labor force constitute

severe demographic headwinds to

future productivity and growth. IMF staff

simulations estimate that under current

policies, the level of Japan’s real GDP

will decline by over 25 percent in about

40 years due to demographics relative

to a projection for real GDP where

productivity and population grow at

their recent pace (Colacelli and

Fernandez-Corugedo, 2018). Adverse

demographic trends place significant

pressures on fiscal sustainability, as age-

related public expenditures rise while tax revenues shrink with the declining labor force (IMF 2018,

Kitao, 2015 and McGrattan et al. 2018).

2. Income inequality in Japan has been increasing, and population aging might

exacerbate this trend. As in other advanced economies, inequality in Japan, especially income

inequality, has been rising (Colacelli and Le, 2018). Intergenerational inequality is an important

1

Prepared by Gee Hee Hong (APD), Sandra Lizarazo Ruiz (SPR), Adrian Peralta-Alva (AFR) and Yuki Yao (University of

Minnesota).

Sources: Japan National I nstitute of Population and Social Security Research; United Nations Statistics

Division, IMF (2018)

2012-2017 Japan population loss:

equivalent to Stockholm

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

aspect of growing inequality in Japan. Pre-tax and transfers income inequality is higher among older

generations than among younger generations. Elderly Japanese are wealthier than younger

Japanese, where the old have more saving and benefit more from fiscal redistribution (via taxes and

transfers). Such intergenerational inequality may be worsened in the context of an aging population.

3. The Japanese government envisages automation and artificial intelligence (AI)

technology as offsetting its declining population and labor force. The Japanese government’s

2014 “Japan Revitalization Strategy,” envisaged a “New Industrial Revolution Driven by Robots.” The

Japanese government launched the ‘Society 5.0’ initiative in 2019, with the aim to better utilize and

disseminate robots across Japan.

2

The initiatives highlighted several sectors that will benefit from

greater usage of robots and AI technology. These sectors include health care, transportation,

infrastructure, and FinTech.

4. This chapter aims to quantitatively assess the macroeconomic and distributional

implications of automation in Japan. Labor saving technologies—automation and AI

technology—change the way production takes place and by so doing can potentially increase

productivity levels in the economy. At the same time, these technologies can disrupt labor market

dynamics and displace labor in certain productive sectors, while expanding labor demand in other

sectors. As the impact of automation and AI technologies is expected to differ for different types of

workers, the widespread adoption of these technologies might further increase market income

inequality and can result in increased income polarization. A proper assessment and quantification

of the macroeconomic and distributional outcomes requires a general equilibrium framework that

can account for the direct and indirect effects that these new technologies have on labor demand,

labor incomes, private investment and aggregate economic activity.

B. Framework of Analysis

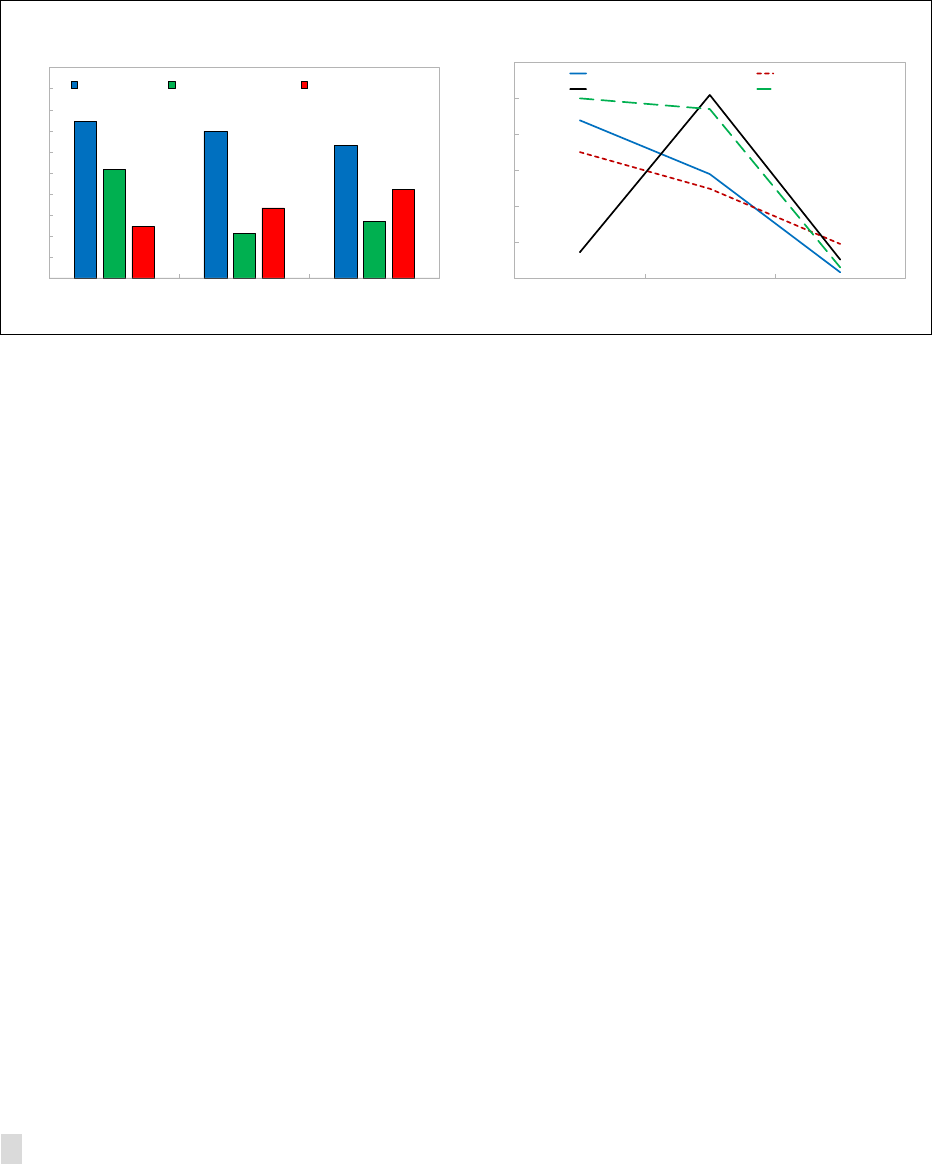

5. The analysis is based on a multi-sector general equilibrium overlapping generations

model developed for the quantitative analysis of the macroeconomic and distributional

effects of aging.

3

This model has a rich production structure that encompasses manufacturing, low

tech-services and the high-tech services sector.

4

We assume that goods in these sectors are

produced using different combinations of factors (tangible and intangible capital, as well as low-,

mid- and high-skill labor)—see text figures below. Households vary by generation and skill level, and

face different levels of taxation and transfers. On the spending side, households receive age-

dependent transfers—pension benefits as well as health and long-term care. On the other hand,

financing instruments include time-varying progressive labor income taxation (including social

security contributions), consumption or value-added tax (VAT), corporate income tax, and

2

The ‘Society 5.0’ initiatives are to create a society that address various social challenges that Japan faces by

incorporating the innovations of the fourth industrial revolution into every industry and social life

(https://www.japan.go.jp/abenomics/_userdata/abenomics/pdf/society_5.0.pdf).

3

For details on such a model tailored to Japan, see McGrattan et al. (2018) and Hong, Lizarazo Ruiz, Peralta-Alva and

Yao (forthcoming).

4

The sectorial structure assumed for this model is similar to Lizarazo Ruiz et al. (2017).

JAPAN

18 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

government debt. These instruments and related parameters are tailored to Japan’s data at the

macro and micro level, building upon McGrattan et al. (2018). In addition, the model’s assumed

demographic transition closely follows the Japanese authorities’ own projections to capture the

dynamics of age-related costs. The analysis considers a baseline steady-state scenario that

corresponds to the period 2000–11, before Japan’s population started to decline, which began in

2012. This period is used to calibrate the model to Japan.

6. The first scenario (labeled as ‘Aging’) considers a long-term scenario in which annual

population growth is shrinking by 1 percent. Under this scenario, social security system (transfers,

pensions and health expenditures), tax rates (except for VAT rates), and the public debt-to-GDP ratio

are anchored at their 2019 levels; age-related fiscal costs of supporting the social security system are

financed through permanent VAT rate increases. A comparison of this scenario with the baseline

scenario permits an assessment of the macroeconomic and distributional impact of aging.

7. The second scenario (labeled as ‘Aging + Robots’) allows for the introduction of

automation and technological change in addition to aging. This scenario has the same

underlying assumptions about negative population growth, the social security and taxation system,

and public debt-to-GDP ratio as the ‘aging’ scenario. In addition, we introduce a higher elasticity

substitution of low- and mid-skilled labor by capital in manufacturing and the high-tech services

sector. This allows some tasks that had to be previously undertaken using labor can now be done

using capital. We also introduce a reduction in the relative price of capital to wages to represent the

fact that with technological change, capital (robots) becomes more affordable. As the exact pace of

technological progress in the future is unknown, we assume that this process will be such that in the

next 40 years, Japan’s share of labor income in GDP will fall by the same amount it fell between 1980

and 2012 (approximately 5 percentage points) and that the relative price of capital goods (robots) to

average wages will fall at an average of 0.5 percent per year. The latter corresponds to the average

decline in the relative price of all private fixed assets to wages between 2000 and 2012 in the United

States.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Low Tech Services Manufacturing High Tech Services

Labor intensity Share of Employment Share of Consumption

Japan: Industry Characteristics in Three Sectors

(in percent)

Sources: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, IMF Staff calculations.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

High School and less College Above College

Low Tech Service Manufacturing

High Tech Service Japan Population

Japan: Skill distribution by Sector

(in percent)

Source: IMF Staff calculations.

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 19

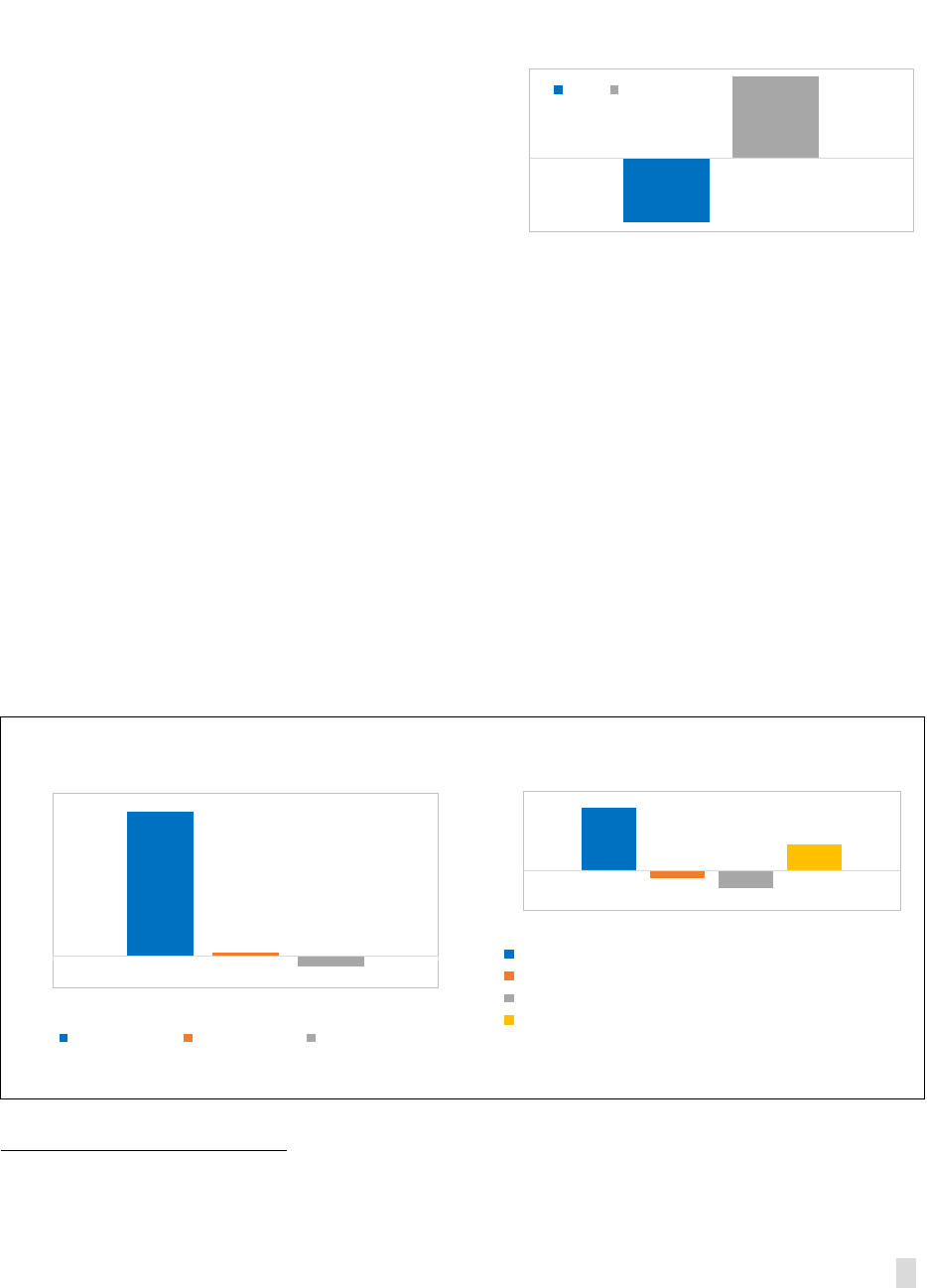

C. Main Findings

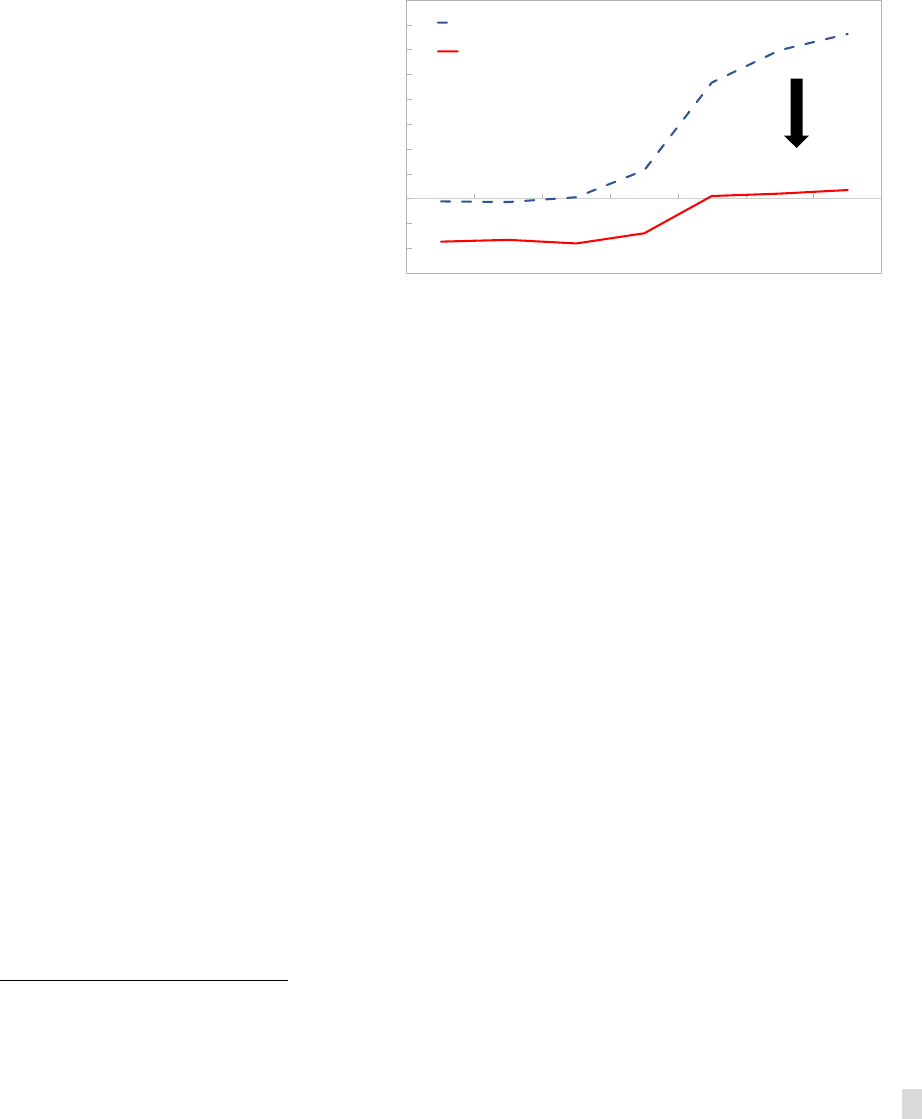

8. In the baseline scenario, the long-term

macroeconomic costs of Japan’s declining and

shrinking population are substantial. Even if we

assume that total factor productivity growth is not

affected by a decline in population growth, the level

of GDP will fall by 8 percent with respect to the

levels observed between 2000 and 2010. Less

workers and less demand due to an aging and

shrinking population will lead to a decline in total

output. On the other hand, fiscal spending will

increase largely due to age-related spending. VAT

rates (or consumption tax rates) will have to increase permanently by 10 percentage points to

maintain the debt-to-GDP ratio at the level observed in 2019 (that is, at about 230 percent).

9. The distributional effects of the demographic transition are troublesome. Our analysis

shows that even though the wages of low-skilled workers increase with aging, market income

inequality rises dramatically, with the Gini coefficient rising by five points (see text charts below).

5

The increase in market income inequality is the net result of two opposing forces: on the one hand,

labor income becomes slightly more equally distributed, but on the other hand, the share of those

whose total income is mainly determined by labor income (young households) falls, while the share

of those whose total income is mainly determined by asset and wealth (older households) increases.

As the distribution of wealth is much more unequal than the distribution of wages (as period by

period differences in wages compound through time), market income distribution becomes much

more unequal as a result of the demographic transition.

5

According to the OECD, Japan’s last observed (2015) market income Gini coefficient was 50.4—almost identical to

the market Gini coefficient for the United States in 2015 (50.6).

2.2

0.0

-0.2

-0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

Aging

Low skill wage Mid skill wage High skill wage

Source: IMF Staff calculations.

Japan: Wages by Skill Level (Aging Scenario)

(Percent change)

-7.9

10.0

-9

-7

-5

-3

-1

1

3

5

7

9

11

Aging

GDP VAT rate

Source: IMF Staff calculations.

Japan: Impact of Aging on GDP Level and VAT rate

(Percent change and percentage point change)

4.8

-0.6

-1.3

2.0

-3.0

-1.0

1.0

3.0

5.0

Aging

Gini market income

Share of market income bottom 20 percent

Share of market income middle segement of population

Share of market income top 20 percent

Source: IMF Staff calculations.

Japan: Distribution of Income (Aging Scenario)

(Percentage point changes)

JAPAN

20 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

10. If technological change continues at its current speed, automation could offset the

impact of population aging on per-capita GDP. Automation (“aging + robots” scenario) might

raise per-capita GDP by 4 percentage points above the average level seen during the period 2000–

11 (see left panel of text chart below). However, automation will not suffice to eliminate fiscal

pressures. Higher aggregate levels of age-related fiscal expenditures will still require an increase in

VAT rates, though the necessary VAT rate increase is half that without automation, rising by 10

percentage points (Aging scenario) and by only 5 percentage points (Aging + Robots scenario).

11. In an aging society, automation could reduce market income inequality. While the

direct impact of automation implies the replacement of workers with robots, the indirect effects of

automation—between-industry shift effects and final demand effects—allow for an important

increase in labor demand that pushes up wages for all workers (Autor and Salomons, 2018). In our

analysis, automation leads to a reduction in market income inequality (see left panel in text chart

below). This is due to the differentiated increase in wages by skill levels. With automation, the share

of market income for the top 20 percent of the population increases, but the increase is smaller than

in the aging-only scenario. The share of market income for middle segment declines with

automation, but the decline is smaller than in the aging-only scenario (see right panel in text chart).

-10

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

Aging Aging + Robots

Japan: GDP Levels - Different Scenarios

(In percent)

Source: IMF Staff calculations.

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Aging Aging + Robots

Japan: Increase in VAT Rate Needed for Fiscal Sustainability

(Percentage point change)

Source: IMF Staff calculations.

3.6

3.8

4

4.2

4.4

4.6

4.8

5

Aging Aging + Robots

Japan: Changes in the Gini Index (Market Income)

(Percentage point change compared to the baseline)

Source: IMF Staff calculations.

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

Aging Aging + Robots

Share of market income bottom 20 percent

Share of market income middle segement of population

Share of market income top 20 percent

Japan: Changes in the Share of Market Income by Income Group

(Percentage point change compared to the baseline)

Source: IMF Staff calculations.

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 21

12. Through its impact in facilitating the financing of the social security system,

automation can help reduce disposable income (and consumption) inequality. As automation

improves market income and makes possible the financing of the social security system with a

smaller increase in VAT tax rates (making the impact of such increases less regressive), automation

improves the distribution of consumption, with the Gini index using disposable income falling by 2

percentage points (see left panel of text chart below).

6

The share of consumption for the bottom 20

percent and middle-segment of the population increases in the aging scenario, but the increases are

larger with automation (see right panel of text chart).

D. Conclusions

13. The extent to which automation can help mitigate the challenges brought by the

demographic transition in Japan depends on whether or not technological change occurs at

its current speed of progress and breadth of reach. Our analysis hinges critically on the

assumptions made on the nature and speed of future technological progress. There is a great deal

of uncertainty as to how this progress will unfold, but recent studies show that our assumption that

technological progress will be as fast as past years may be an upper bound. Nordhaus (2015)

discusses that in recent periods, technological change—measured by the rate of decline of capital

prices to labor wage rate—does not seem to be accelerating and may even be slowing. In a similar

fashion, IMF (2017) finds that the growth rate of cyclically-adjusted total factor productivity for

advanced economies between 2008–14 is about half the rate of growth observed between 2003–07,

and approximately one fifth the rate of growth observed between 1990 and 2002.

14. To reap the maximum benefits from automation to offset the adverse impact of a

declining population, investment in technology, innovation and education will need to have a

high rate of return. If the future growth rate of technological change is only one half that observed

between 2000–12 (also half the assumed rate underlying our analysis), automation would not suffice

6

According to the OECD, Japan’s disposable income Gini was 33.9 in 2015.

-2.5

-2

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

Aging Aging + Robots

Japan: Changes in the Gini Index (Consumption)

(Percentage Point Change Compared to the Baseline)

Source: IMF Staff calculations.

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

Aging Aging + Robots

Share of consumption bottom 20 percent

Share of consumption middle segement of population

Share of consumption top 20 percent

Japan: Changes in the Share of Consumption by Income Group

(Percentage Point Change Compared to the Baseline)

Source: IMF Staff calculations.

JAPAN

22 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

to prevent the fall of per-capita GDP caused by the demographic transition in Japan. This suggests

that measures that help ensure that technological innovation is successful will have a large

economic dividend. Efforts should be made to encourage spending on research and development,

and improve education levels, to help familiarize workers with new technologies and enhance their

labor productivity.

15. At the same time, policies to address the distributional consequences of automation

are important. One aspect not yet considered in this analysis, which deserves further attention, is

the impact of automation on gender inequality and inequality across generations. Hamaguchi and

Kondo (2018) estimate that female workers in Japan are exposed to higher risk of being replaced by

‘computerization’ than male workers. Similarly, elderly workers often enter the work force as part-

time workers in sectors that require low-skills, and are thus more likely to be replaced by

automation. Strong and effective social safety nets will be crucial to protect these workers, since

disruptions of some traditional labor and social contracts due to automation are highly likely during

Japan’s demographic transition.

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 23

References

Autor, David and Anna Salomons, 2018, “Is Automation Labor-Displacing? Productivity Growth,

Employment, and the Labor Share,” Brookings Paper on Economic Activity.

Colacelli, Mariana and Emilio Fernandez-Corugedo, 2018, “Macroeconomic Effects of Japan’s

Demographics: Can Structural Reforms Reverse Them?” IMF Working Paper 18/248.

Colacelli, Mariana and Anh Le, 2018, “Inequality in Japan: Generational, Gender and Regional

Considerations,” in “Japan: Selected Issues,” IMF Country Report 18/334.

Hamaguchi, N. and K. Kondo, 2017, “Regional Employment and Artificial Intelligence,” RIETI

Discussion Paper, 17-K-023. Research Institute of Economy, Trade, and Industry, Tokyo.

Hong, G., A. Le, and T. Schneider, 2018, “Land of the Rising Robots,” Finance & Development, June

2018, Vol. 55 (2), pp. 28–31.

Hong, G., S. Lizarazo Ruiz, A. Peralta-Alva, and Y. Yao, forthcoming, “Is Automation the Answer to

Japan’s Demographic Challenges?”, IMF Working Paper.

International Monetary Fund, 2017, “Gone with the Headwinds: Global Productivity,” IMF Staff

Discussion Note, SDN/17/04.

International Monetary Fund, 2018, “Japan: Article IV Consultation – Staff Report,” IMF Country

Report 18/333.

Kitao, Sagiri, 2015, “Fiscal Cost of Demographic Transition in Japan, “Journal of Economic Dynamics

and Control, Vol. 25, pp. 37–58.

Lizarazo Ruiz, S., A. Peralta-Alva, and D. Puy, 2017, “Macroeconomic and Distributional Effects of

Personal Income Tax Reforms: A Heterogeneous Agent Model Approach for the U.S.” IMF Working

Paper 17/192.

McGrattan, E., K. Miyachi, and A. Peralta-Alva, 2018, “On Financing Retirement, Health, and Long-

Term Care in Japan,” IMF Working Paper 18/249.

Nordhaus, William, 2015, “Are We Approaching an Economic Singularity? Information Technology

and The Future of Economic Growth,” Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper No. 2021, New Haven:

Yale University.

JAPAN

24 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

JAPAN’S FERTILITY RATE

1

Japan’s population is projected to decline by more than 25 percent in the next 40 years, if the current

low fertility rate persists. This overwhelming demographic challenge ahead of Japan leads to

consideration as to whether there are policies the authorities can implement to affect the fertility rate.

This chapter takes stock of recent developments with respect to Japan’s fertility rate, and argues that a

combination of policies could raise the fertility rate if implemented in a coordinated and sustained

manner.

A. Introduction

1. Japan’s population is projected to decline by more than 25 percent in the next 40

years, if the current low fertility rate persists. Japan’s total fertility rate (sum of the age-specific

birth rates of women aged 15 to 49) stood at 1.4 children per woman in 2018, which is well below

the population replacement level of 2.1.

2

In addition,

a large gap remains between the actual fertility rate

and the “desired” rate of 1.8—the latter being the

rate expected if people had their desired number of

children. This gap raises the question as to whether

public policies can help increase Japan’s fertility rate

by removing potential obstacles. A higher fertility

rate could have positive impacts on aggregate GDP

over the long-run, by increasing the size of the labor

force and helping stabilize public debt (as a share of

GDP). At the same time, this policy objective needs

to be mutually consistent and reinforcing with other

public policy objectives. For example, the IMF has

stressed the need to promote female labor force

participation—see IMF (2018), Colacelli and

Fernandez-Corugedo (2018). However, if not

accompanied by sufficient support for working couples with small children, higher FLFP could

potentially increase the opportunity cost of giving birth and thereby lower the fertility rate. The

Japanese government has stepped up its support for households with children, with notable

measures being increasing the availability of childcare facilities and making preschool and childcare

free. This chapter takes stock of recent developments in Japan’s fertility rate, and discusses whether

public policy can help increase the fertility rate.

1

Prepared by Takuma Hisanaga (APD).

2

The total fertility rate in a specific year is defined as the total number of children that would be born to each woman

if she were to live to the end of her child-bearing years and give birth to children in alignment with the prevailing

age-specific fertility rates. This indicator is measured in children per woman. See OECD (2019).

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 25

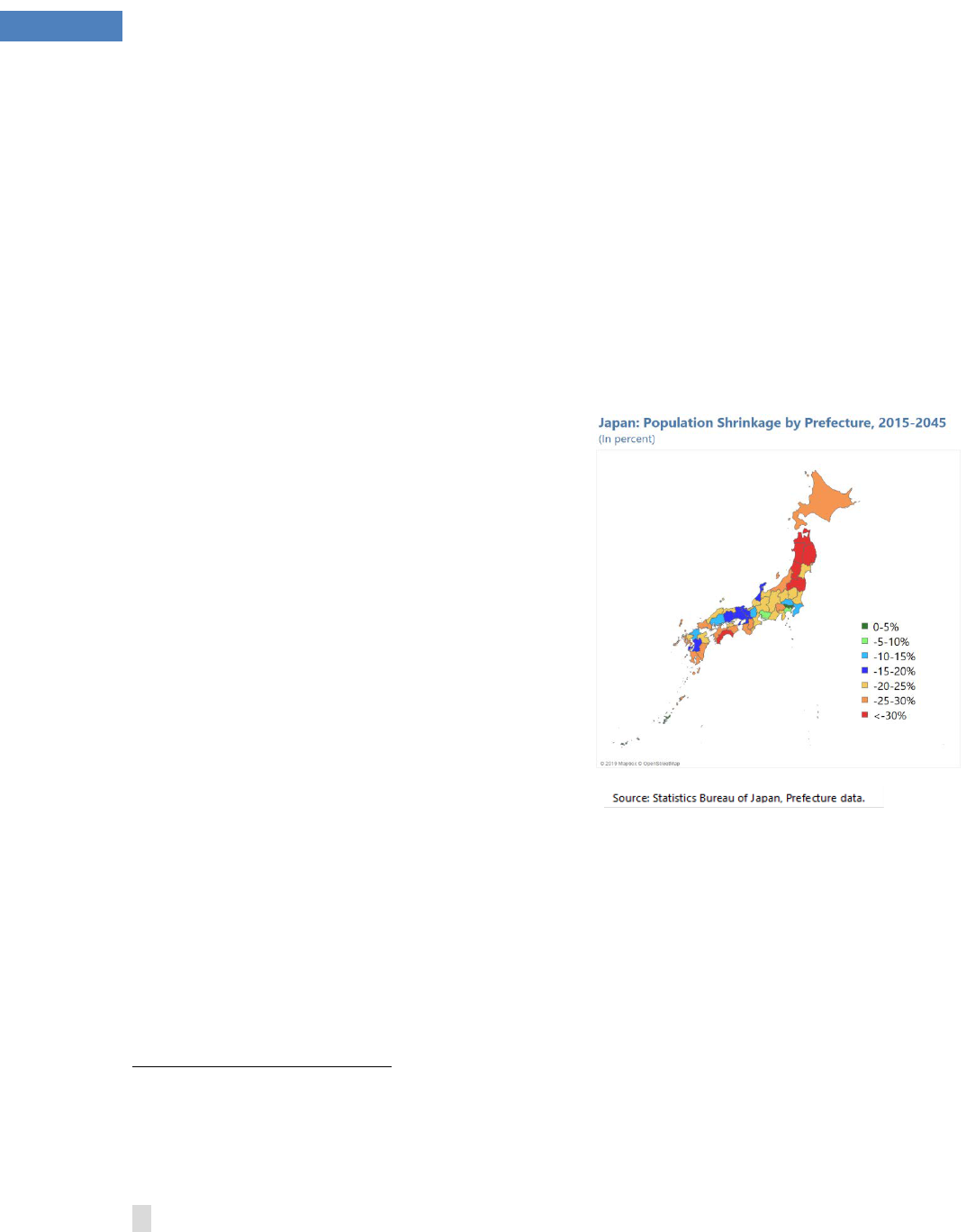

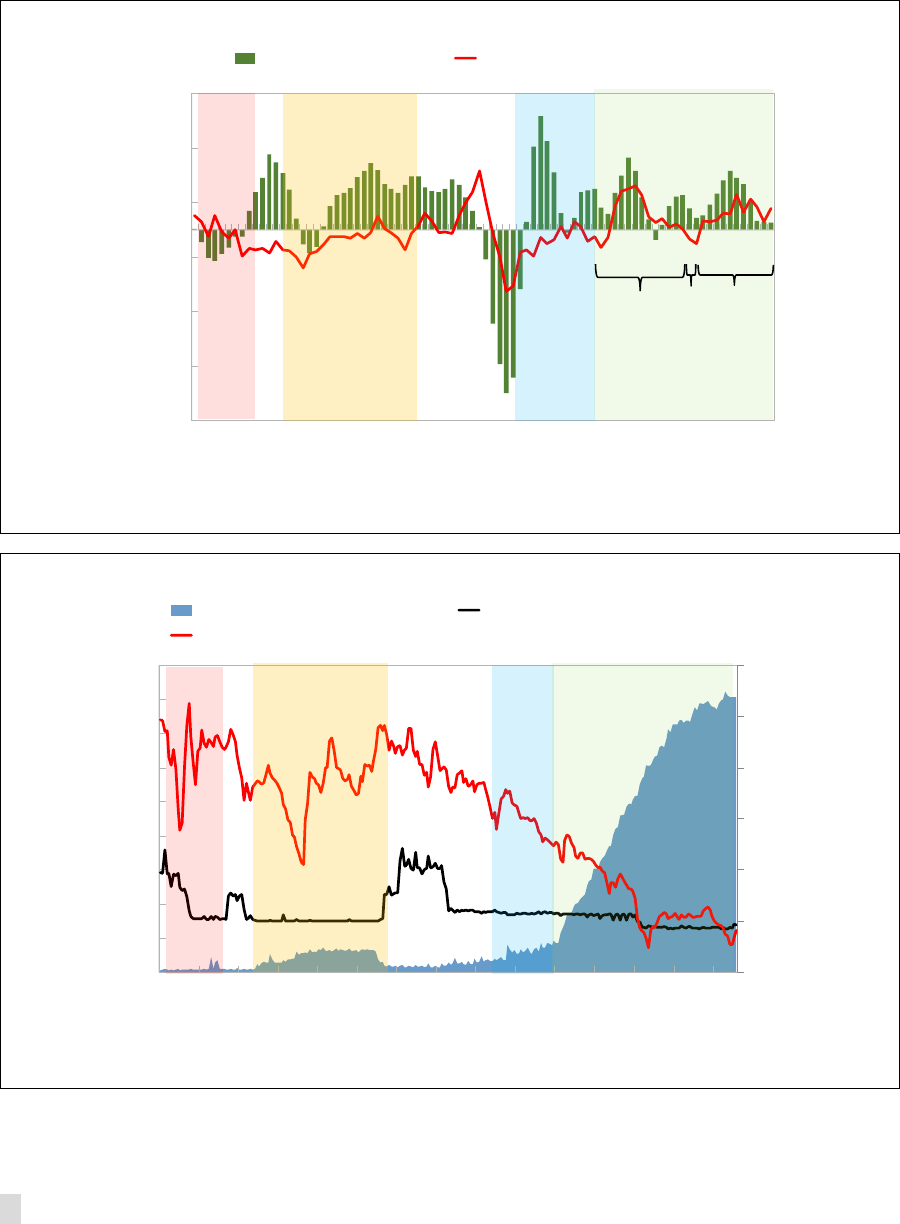

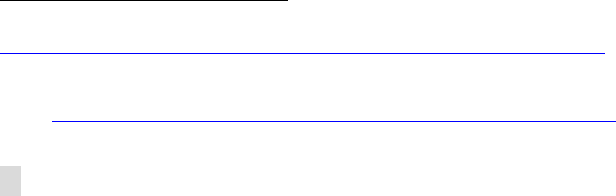

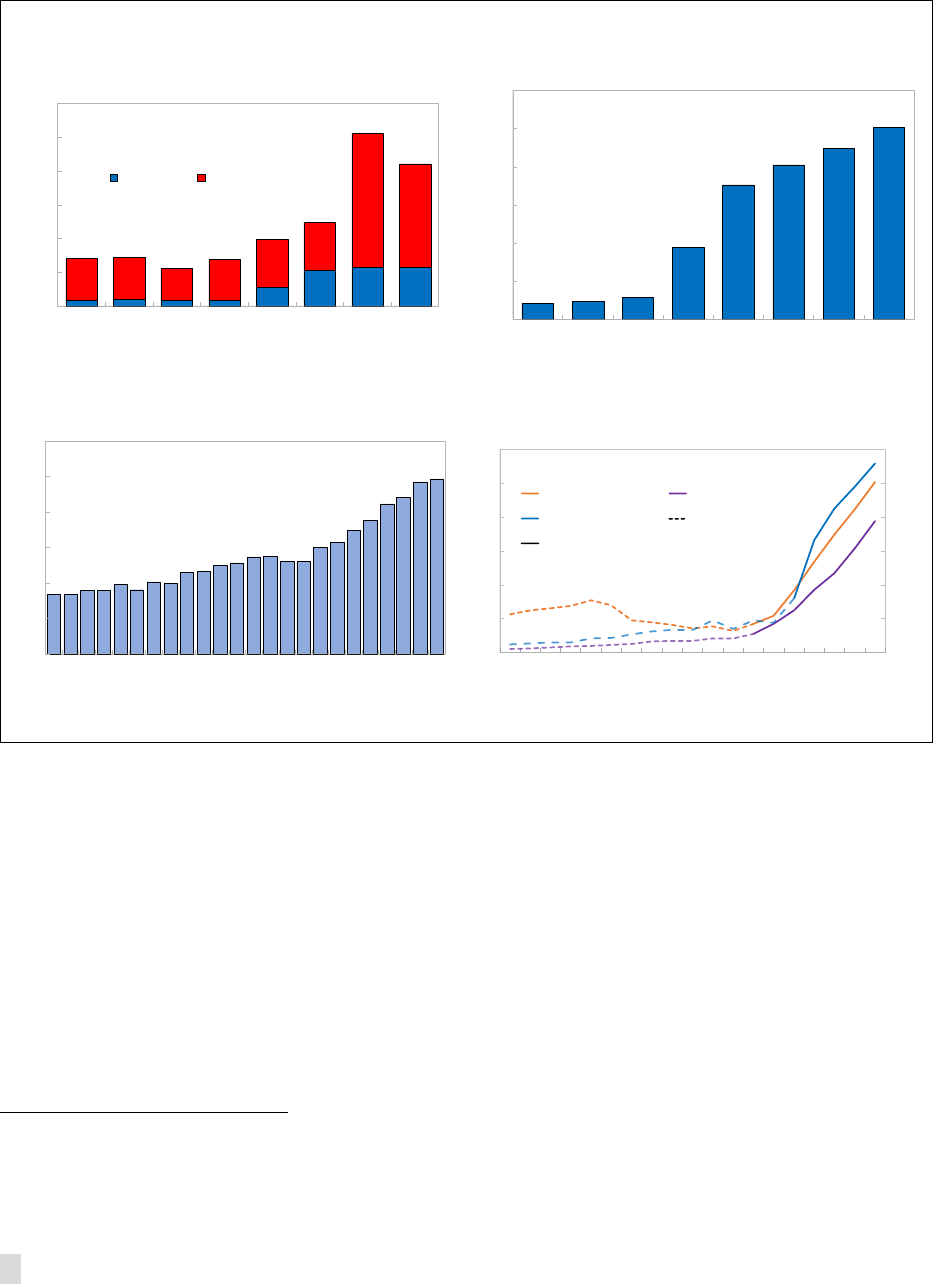

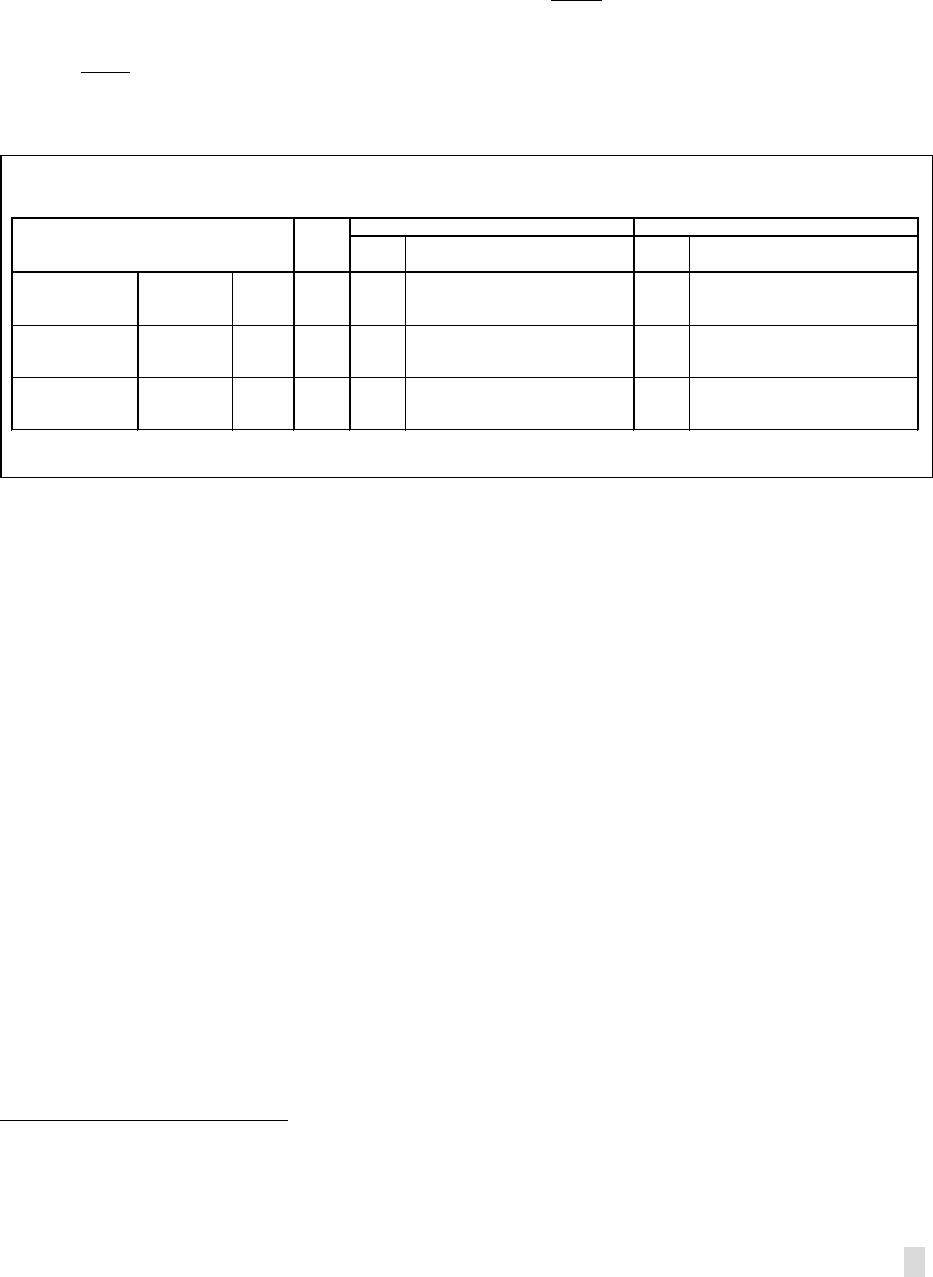

B. Overview of Japan’s Fertility Rate

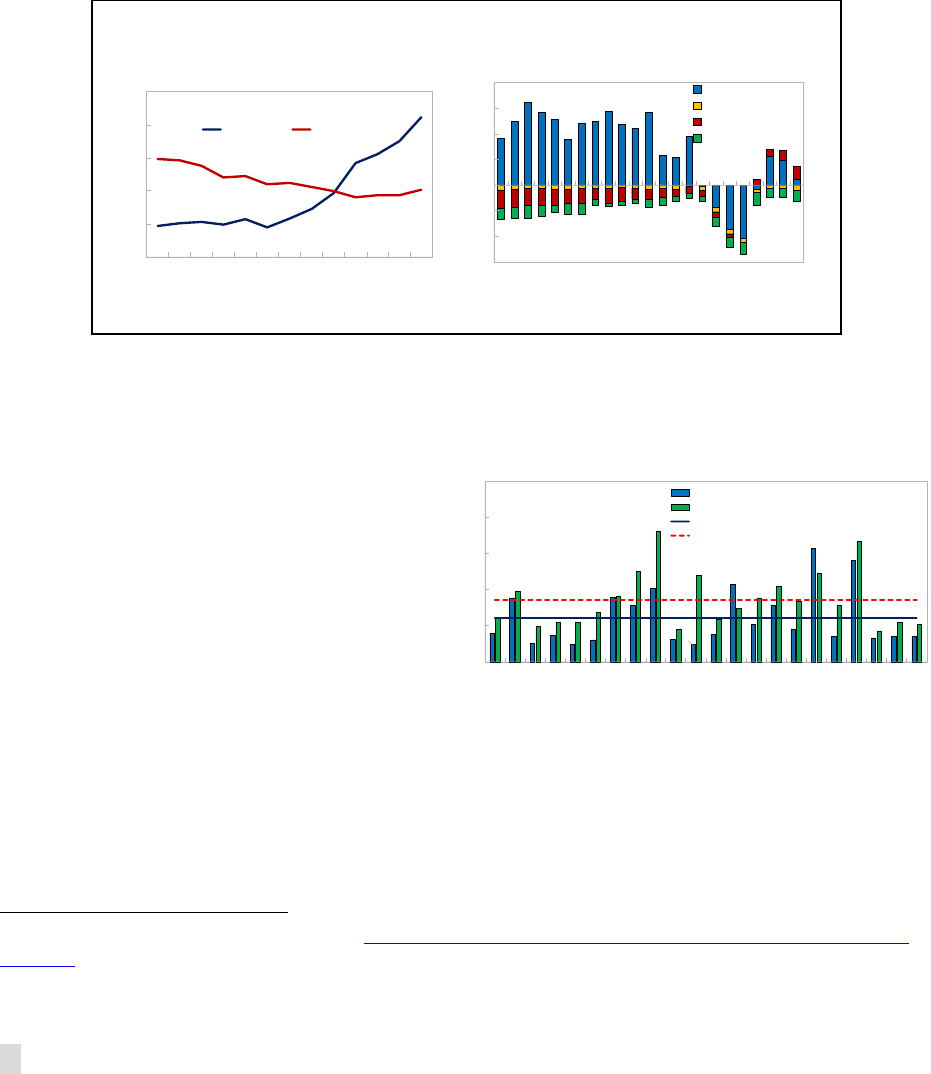

2. Japan’s fertility rate has improved in recent years but remains low at 1.4 children per

woman. After the second baby boom in the early 1970s, Japan’s fertility rate declined until it

bottomed out at 1.26 in 2005 (see top-left chart of Figure 1). This declining trend of fertility mirrors

the trend increase in the percentage of late-married and non-married (see the bottom two charts of

Figure 1). The marriage rate (the number of marriages per population of 1,000 persons) in Japan

halved from around 10 in the early 1970s to around 5 in 2015. In more recent years, Japan’s fertility

rate has marginally recovered, but remains low at around 1.4 children per woman—well below the

population replacement rate of 2.1, and lower than all other G7 countries except Italy (see the top-

right chart of Figure 1).

3. A gap exists between the actual and desired number of children per couple. According

to a survey by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (the NIPSSR), an

ideal number of children for a couple is 2.32 on average.

3

However, those couples plan to have on

average 2.01 children—the sum of the number of children already born (1.68) and the number of

3

See NIPSSR (2015).

Figure 1. Japan’s Fertility Rate–Stylized Facts

JAPAN

26 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

additional children the couple plans to have (0.33). On the other hand, while the unmarried rate of

females aged 30–34 has risen to about 35 percent, 90 percent of unmarried females aged 18–34

intend to marry in the future. Based on the NIPSSR survey and other data, the government estimates

the “desired” fertility rate of 1.8

4

that could be achieved through closing the gap between the actual

and desired number of children, and removing obstacles to higher fertility rates.

4. The direct cost of childbearing

seems to be the most important factor

which prevents couples from attaining

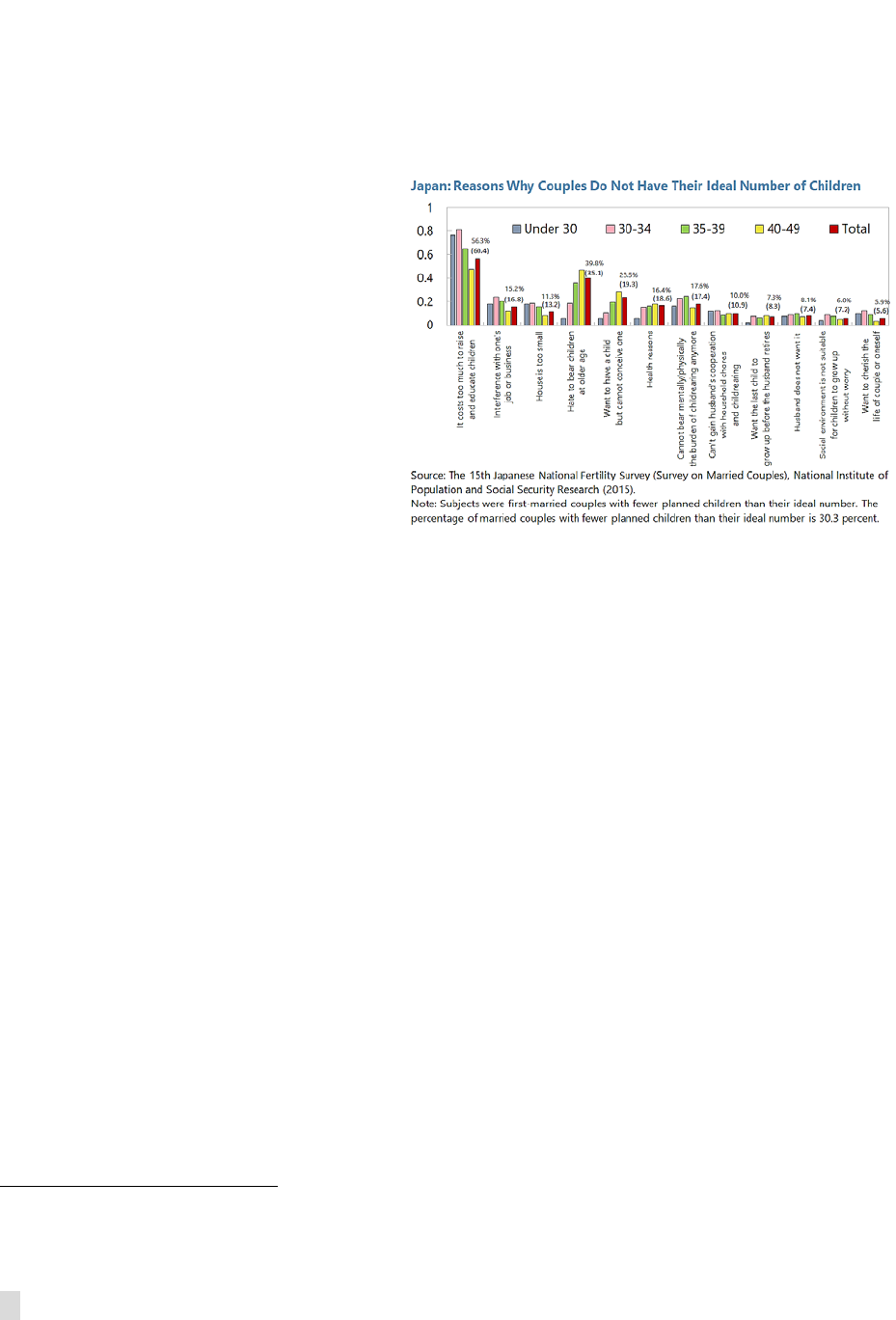

their ideal number of children. The

NIPSSR 2015 survey summarizes the

reasons why couples do not have their

ideal number of children. The top reason

cited by 56 percent of couples is the cost

of childbearing; this is followed by the

reluctance to bear a child at an advanced

age (40 percent).

5. The opportunity cost of

childbearing also matters. During the period of Abenomics, Japan’s female labor force

participation rates (FLFP) have substantially increased from 63 percent in 2012 to 71 percent in 2018

(for those aged 15 to 64), according to OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics. A higher

FLFP could increase household incomes and make the cost of childbearing affordable (i.e., the

income effect). On the other hand, higher FLFP could increase the opportunity cost of having

children as females typically need to leave their workplaces for a certain period of time (i.e., the

substitution effect). In fact, according to the NIPSSR (2015) survey, about 15 percent of couples

responded that their jobs/businesses are one of the main reasons for the gap between the actual

and desired number of children, which can be seen as a measure of the opportunity cost of having

children.

4

This rate is based on the planned number of children for a couple, as well as other statistics including the share of

single people who hope to marry and the desired number of children of single people.

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 27

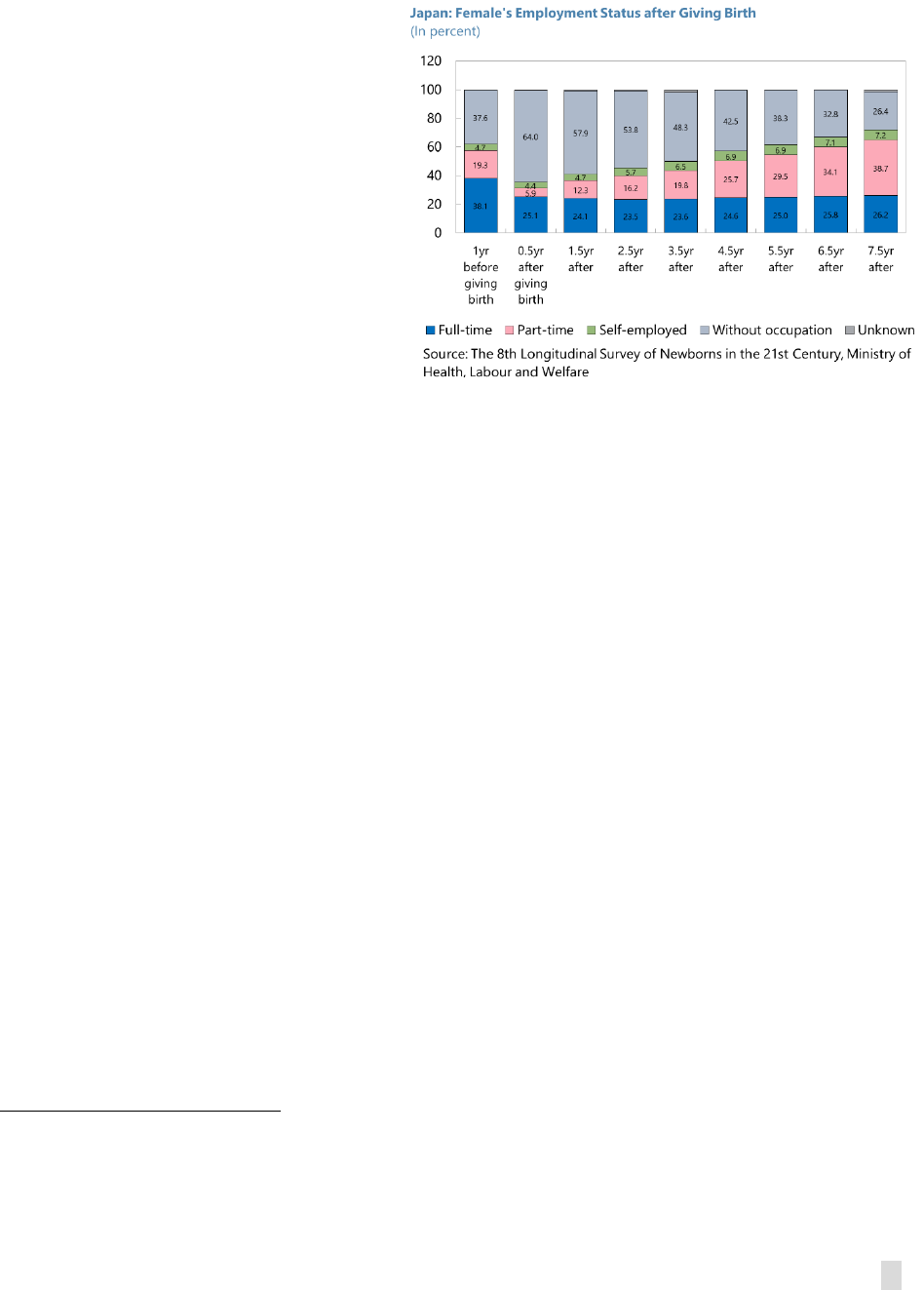

6. The opportunity cost of having children is high for full-time workers. According to a

longitudinal survey of Japanese newborns

in 2010, the total share of female workers

sharply dropped after giving birth from 62

percent to 35 percent (see Ministry of

Health, Labour and Welfare (2019)). The

total share of female workers gradually

recovered to the level before childbirth (61

percent) about 5.5 years after giving birth.

However, as illustrated in the text chart on

the right, most of the female workers re-

entered the job market as part-time

workers. The share of full-time workers

dropped from 38 percent to 25 percent

after childbirth and remained low at

around 26 percent even 7.5 years after giving birth. The MHLW survey suggests that a number of

full-time female workers give up full-time status after childbirth, which has enduring implications for

their lifetime income and employment benefits.

C. Empirical Analysis: Data and Methodology

7. This section provides a simple empirical analysis to study the possible drivers of

Japan’s fertility rate. D'Addio and Mira d'Ercole (2005) discussed the historical development of

fertility rates across OECD countries and showed that, based on a static cross-section analysis,

fertility rates are lower when the direct costs of childbearing are higher. Regarding the impact of

increased FLFP, they calculated that the correlation between female employment rates and total

fertility rates in OECD countries turned from negative to positive in the late 1980s. Using a dynamic

panel data model, they observed that the fertility rate is higher when (i) female employment rates

are higher, and/or (ii) the ratio of female to male wages is lower. In this section, an approach similar

to D'Addio and Mira d'Ercole (2005) is applied to Japan’s prefecture-level panel data to study Japan

specific features.

5

8. A panel dataset was constructed that covers data for 47 prefectures for the period

2001 to 2015. In the panel regression analysis, the dependent variable is the prefecture-level total

fertility rate, and five variables that might affect the total fertility rate are included as explanatory

variables:

• Education costs. The share of education expenses in total expenditures for non-single households

is derived from the Family Income and Expenditure Survey conducted by the Ministry of Internal

5

Among the previous studies of the fertility rate in Japan, Abe and Harada (2008) observed that, based on a cross-

section analysis of municipal-level data, a rise in female wages had a negative impact on the fertility rate, and that the

impact of improved availability of childcare facilities on the fertility rate was positive. Kato (2018) also analyzed

municipal-level data to find a positive impact of the female labor participation rate on the total fertility rate.

JAPAN

28 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Affairs and Communications. As this could be viewed as a proxy for the direct cost of child-

rearing, the expected sign is negative for the relationship between the total fertility rate and

education costs.

• Female labor force participation rate. The prefectural labor force participation rates (ratios of

labor force over the population) for women between 15 and 64 years old are derived from data

of the National Census.

6

Based on the findings by D'Addio and Mira d'Ercole (2005), the

expected sign is positive for the relationship between the FLFP rate and the total fertility rate.

• Wage gap. Ratios of female to male monthly wages (a higher ratio indicates a smaller wage gap

between male and female) are used to measure the gap. The wage is average monthly

contractual cash earnings in the MHLW’s Basic Survey on Wage Structure. D'Addio and Mira

d'Ercole (2005) find that a smaller wage gap (i.e., a higher ratio of female to male wages) implies

a larger opportunity cost due to foregone income during maternity leave, leading to lower

fertility rates. However, in the case of Japan, female workers often give up their full-time status

after childbirth, as discussed in the previous section. Hence, a large wage gap could reflect

changes in women’s employment status after childbirth in Japan. Provided that the observed

large wage gap (i.e., a low ratio of female to male wages) is attributable to a large share of

female part-time workers after childbirth, the opportunity cost of giving birth would increase

over the long-run, which could lower the fertility rate. Furthermore, a smaller wage gap is

expected to yield better income prospects after childbirth, which increases the affordability of

childbearing. In light of these factors, the expected sign of the wage gap-total fertility rate

relationship could be positive, which would run contrary to the findings of D'Addio and Mira

d'Ercole (2005).

• Availability of childcare facilities. The capacity (sum of authorized quotas of children) of childcare

facilities for each prefecture is obtained from the MHLW’s Survey of Social Welfare Institutions.

Following Unayama (2009), the capacity is divided by the female population between 20 and 44

years old to make it comparable across prefectures. This variable can be viewed as an indication

of commitment to child-friendly policies by prefectural governments. The expected sign of the

relationship between total fertility rate and childcare facilities is positive.

• Unemployment rate. Prefecture-level unemployment rates are obtained from the Statistics

Bureau’s model-based estimates, based on data from the Labor Force Survey. This variable is

introduced to factor in macroeconomic conditions, and the expected sign of the unemployment

rate-total fertility rate relationship is negative.

9. The Pooled-Mean Group estimator is the preferred model. The simple pooled OLS

regression model does not allow for prefecture-specific effects. A commonly-used alternative, the

fixed effects estimator, takes account of prefecture-specific effects, but fails to deal with the issue of

the endogeneity of explanatory variables with respect to the total fertility rate. In order to deal with

the endogeneity issue, the PMG (Pooled Mean Group) estimator proposed by Pesaran et al. (1999) is

6

As the National Census is a quinquennial survey, values for gap years are filled by linear interpolation.

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 29

used here, following the approach of D'Addio and Mira d'Ercole (2005). The PMG estimator

distinguishes long-run and short-run dynamics. Coefficients for long-run effects are assumed to be

identical across prefectures, while those for short-run effects are allowed to differ. The other model

used in D'Addio and Mira d'Ercole (2005), a GMM (Generalized Method of Moments)-System

estimator developed by Arellano and Bover (1995) and Blundell and Bond (1998), is a less preferred

option here, because the post-estimation Sargan test rejected the null hypothesis that over-

identifying restrictions are valid, indicating a potential misspecification (see Table 1). Therefore, the

discussion hereafter is based on the PMG estimates, with a focus on the long-run dynamics, while

turning to the GMM estimates as a complementary reference.

D. Results

10. Every explanatory variable has a statistically-significant impact on the prefectural

fertility rate in the long-run. Table 1 shows the results:

• Wage gap. A rise in the female wage relative to the male wage (a smaller gap between male and

female wages) has a positive impact on fertility rates in the long-run. This supports the argument

that a smaller wage gap could indicate lower opportunity costs of childbirth over the long-run,

and make childbearing more affordable. On the other hand, the sign is negative in the short-run.

A possible interpretation of this negative short-run effect is that a smaller wage gap could lower

the fertility rate in the short-run due to a larger foregone income during maternity leave.

• Female labor force participation rate. A higher female labor force participation rate has a positive

impact on the fertility rate in the long-run, in line with the findings of D'Addio and Mira d'Ercole

(2005). The long-run result indicates that a one-percentage point increase in the FLFP rate is

associated with a 0.04 increase in the fertility rate (see Table 1). Meanwhile, the sign is negative

in the short-run, possibly pointing to a negative impact of opportunity costs on the fertility rate,

as discussed above.

• Education costs. A reduction in education costs has a positive impact on the fertility rate in the

long run, though this was not confirmed in the GMM estimates. The short-run coefficient is not

statistically significant.

• Childcare facilities. An increase in childcare facilities has a positive impact on the fertility rate

both in the short run and long run, demonstrating the potential effectiveness of child-friendly

policies in raising the total fertility rate.

• Unemployment rate. The sign of the long-run coefficient is positive, while it is negative in the

short run. The coefficient is statistically insignificant in the GMM estimates. This positive

correlation could imply a low opportunity cost of childbearing when unemployment rates are

high, though further analysis is warranted on this point.

JAPAN

30 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

E. Policy Implications and Conclusions

11. The Japanese government’s Work Style Reform, which has intensified since 2016,

could have a positive impact on the fertility rate.

7

Introduction of public policies to reduce the

unwilling exclusion of female workers from the labor market following childbirth could raise the

fertility rate over the long-term. It is of particular importance to nurture a working and social

environment where female regular workers can retain regular-worker status after childbirth, if they

wish to. Potential measures the authorities could undertake to achieve this goal include: (i) further

increasing childcare availability; (ii) rewarding firms with high retention rates of female employees

after childbirth; and (iii) eliminating disincentives to regular and full-time work embedded in the tax

and social security systems (see IMF (2019)). The impact on the fertility rate could be reinforced by

measures to alleviate the direct cost of childbearing, such as lowering education and childcare costs.

12. Public policies supporting fertility should be implemented in a coordinated and

sustained manner. Since the impact of each policy on the fertility rate is relatively small, a wide

array of policies needs to be put in place in a coordinated, mutually-reinforcing manner in order to

make a meaningful impact on the fertility rate. Lastly, the negative short-run effects of female labor

force participation and the wage gap on the total fertility rate point to a need for the authorities to

be persistent—sustaining public policies to support fertility even if the fertility rate is negatively

affected in the short-run.

7

See also Box 2 of International Monetary Fund (2019) Japan: Article IV Consultation—Staff Report, for a case study of

the experience of Nagi-town in Okayama Prefecture.

JAPAN

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 31

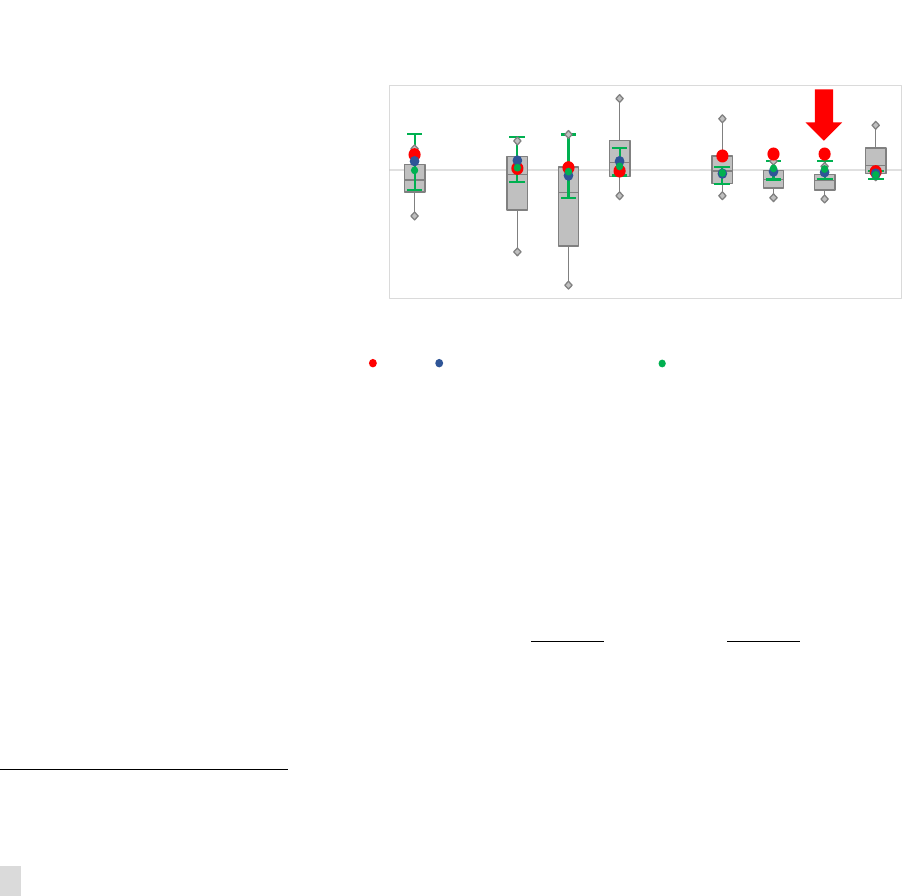

Table 1. Japan: Estimation Results of Total Fertility Rate by Prefecture, 2001–15

(1)

(2) (3)

PMG PMG

(long-run

coefficients)

(short-run

coefficients)

Wage gap 1.039*** 0.402***

(0.198) (0.0815)

FLFP 4.003*** 0.787***

(0.583) (0.214)

Education costs -1.170** -0.0518

(0.507) (0.226)

Childcare facilities 3.153*** 1.151***

(0.811) (0.211)

Unemployment rate 4.442*** -0.116

(0.655) (0.266)

Lag of total fertility rate 0.438***

(0.0340)

Error correction term -0.385***

(0.0353)