2023 Landscape

2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authored by Amba Kak and Dr. Sarah Myers West.

With research and editorial contributions from Alejandro Calcaño, Jane Chung, Dr. Kerry McInerney and

Meredith Whittaker.

Copyediting by Caren Litherland.

Design by Partner & Partners.

Special thanks to all those that provided feedback on sections in the report including Veena Dubal,

Ryan Gerety, Sara Geoghegan, Ellen Goodman, Alex Harman, Daniel Leufer, Estelle Masse, Fanny

Hidvegi, Tamara Kneese, J. Nathan Mathias, Julia Powles, Daniel Rangel, Gabrielle Rejouis, Maurice

Stucke, Charlotte Slaiman, Lori Wallach, Ben Winters, and Jai Vipra.

Cite as: Amba Kak and Sarah Myers West, “AI Now 2023 Landscape: Confronting Tech Power”, AI Now

Institute, April 11, 2023, https://ainowinstitute.org/2023-landscape.

2023 Landscape

3

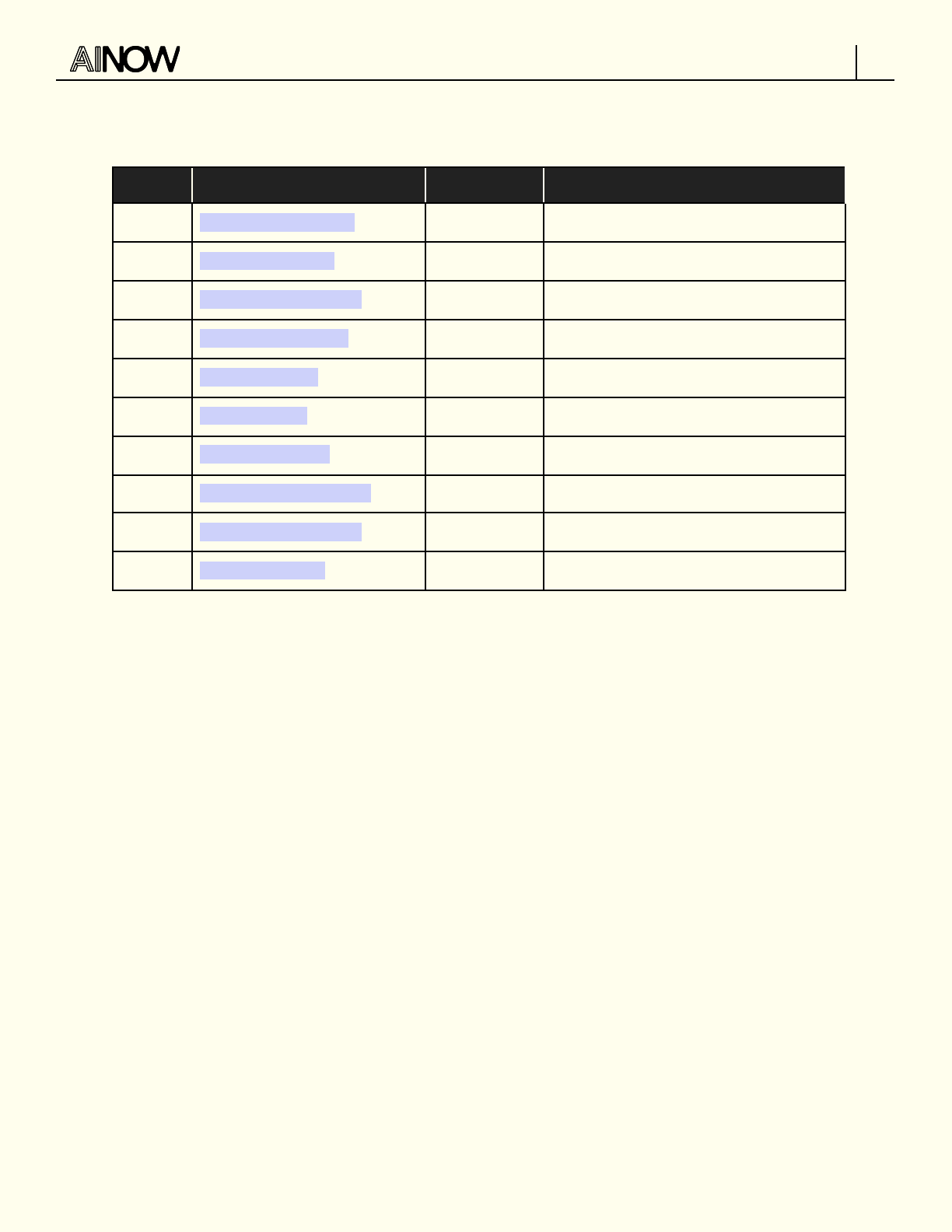

Table of Contents

Executive Summary............................................................................................................................................................5

chatGPT And More: Large Scale AI Models Entrench Big Tech Power.................................................................16

Toxic Competition: Regulating Big Tech’s Data Advantage....................................................................................24

Algorithmic Accountability: Moving beyond audits..................................................................................................35

SPOTLIGHT: Data Minimization as a Tool for AI accountability............................................................................. 44

Algorithmic Management: Creating Bright-Line Rules to Restrain Workplace Surveillance.........................48

SPOTLIGHT: Tech and Financial Capital...................................................................................................................... 58

Antitrust: It’s Time for Structural Reforms to Big Tech........................................................................................... 64

Biometric Surveillance Is Quietly Expanding: Bright-Line Rules Are Key........................................................... 75

International “Digital Trade” Agreements: The Next Frontier.................................................................................80

US-China Arms Race: AI Policy as Industrial Policy.................................................................................................86

SPOTLIGHT: The Climate Costs of Big Tech............................................................................................................. 100

2023 Landscape

4

Executive Summary

Artificial intelligence

1

is captivating our attention, generating both fear and awe about what’s coming

next. As increasingly dire prognoses about AI’s future trajectory take center stage in the headlines

about generative AI, it’s time for regulators, and the public, to ensure that there is nothing about

artificial intelligence (and the industry that powers it) that we need to accept as given. This watershed

moment must also swiftly give way to action: to galvanize the considerable energy that has already

accumulated over several years towards developing meaningful checks on the trajectory of AI

technologies. This must start with confronting the concentration of power in the tech industry.

The AI Now Institute was founded in 2017, and even within that short span we’ve witnessed similar hype

cycles wax and wane: when we wrote the 2018 AI Now report, the proliferation of facial recognition

systems already seemed well underway, until pushback from local communities pressured government

ocials to pass bans in cities across the United States and around the world.

2

Tech firms were

associated with the pursuit of broadly beneficial innovation,

3

until worker-led organizing, media

investigations, and advocacy groups shed light on the many dimensions of tech-driven harm.

4

These are only a handful of examples, and what they make clear is that there is nothing about

artificial intelligence that is inevitable. Only once we stop seeing AI as synonymous with progress

can we establish popular control over the trajectory of these technologies and meaningfully confront

their serious social, economic, and political impacts—from exacerbating patterns of inequality in

housing,

5

credit,

6

healthcare,

7

and education

8

to inhibiting workers’ ability to organize

9

and incentivizing

content production that is deleterious to young people’s mental and physical health.

10

In 2021, several members of AI Now were asked to join the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to advise

the Chair’s oce on artificial intelligence.

11

This was, among other things, a recognition of the growing

centrality of AI to digital markets and the need for regulators to pay close attention to potential harms

11

Federal Trade Commission, “FTC Chair Lina M. Khan Announces New Appointments in Agency Leadership Positions,” press release, November 19,

2021.

10

See Zach Praiss, “New Poll Shows Dangers of Social Media Design for Young Americans, Sparks Renewed Call for Tech Regulation,” Accountable

Tech, March 29, 2023; and Tawnell D. Hobbs, Rob Barry, and Yoree Koh, “‘The Corpse Bride Diet’: How TikTok Inundates Teens with Eating-Disorder

Videos,” Wall Street Journal, December 17, 2021.

9

Ibid.

8

Rashida Richardson and Marci Lerner Miller, “The Higher Education Industry Is Embracing Predatory and Discriminatory Student Data Practices,”

Slate, January 13, 2021.

7

Ziad Obermeyer, Brian Powers, Christine Vogeli, and Sendhil Mullainathan, “Dissecting Racial Bias in an Algorithm Used to Manage the Health of

Populations,” Science 366, no. 6464 (October 25, 2019): 447–53.

6

Christopher Gilliard. “Prepared Testimony and Statement for the Record,” Hearing on “Banking on Your Data: The Role of Big Data in Financial

Services,” House Financial Services Committee Task Force on Financial Technology, 2019.

5

Robert Bartlett, Adair Morse, Richard Stanton, and Nancy Wallace, “Consumer-Lending Discrimination in the FinTech Era,” Journal of Financial

Economics 143, no. 1 (January 1, 2022): 30–56.

4

Varoon Mathur, Genevieve Fried, and Meredith Whittaker, “AI in 2019: A Year in Review,” Medium , October 9, 2019.

3

See Jenna Wortham, “Obama Brought Silicon Valley to Washington,” New York Times, October 25, 2016,; and Cecilia Kang and Juliet Eilperin, “Why

Silicon Valley Is the New Revolving Door for Obama Staers,” Washington Post, February 28, 2015.

2

Meredith Whittaker, Kate Crawford, Roel Dobbe, Genevieve Fried, Elizabeth Kaziunas, Varoon Mathur, Sarah Myers West, Rashida Richardson, Jason

Schultz, Oscar Schwartz, AI Now 2018 Report, AI Now Institute, December 2018.

Tom Simonite, “Face Recognition Is Being Banned—But It’s Still Everywhere,” Wired, December 22, 2021.

1

The term ‘artificial intelligence’ has come to mean many dierent things over the course of its history, and may be best understood as a marketing

term rather than a fixed object. See for example: Michael Atleson, “Keep your AI Claims in Check”, Federal Trade Commission, February 27, 2023,;

Meredith Whittaker, “Signal, and the Tech Business Model Shaping Our World”, Conference on Steward-Ownership 2023,, Annie Lowery, “AI Isn’t

Omnipotent. It’s Janky”, The Atlantic, April 3, 2023.

2023 Landscape

5

to consumers and competition. Our experience within the US government helped clarify the path for

the work ahead.

ChatGPT was unveiled during the last month of our time at the FTC, unleashing a wave of AI hype that

shows no signs of letting up. This underscored the importance of addressing AI’s role and impact, not

as a philosophical futurist exercise but as something that is being used to shape the world around us

here and now. We urgently need to be learning from the “move fast and break things” era of Big Tech;

we can’t allow companies to use our lives, livelihoods, and institutions as testing grounds for novel

technological approaches, experimenting in the wild to our detriment. Happily, we do not need to draft

policy from scratch: artificial intelligence, the companies that produce it, and the aordances required

to develop these technologies already exist in a regulated space, and companies need to follow the

laws already in eect. This provides a foundation, but we’ll need to construct new tools and

approaches, built on what we already have.

There is something dierent about this particular moment: it is primed for action. We have

abundant research and reporting that clearly documents the problems with AI and the companies

behind it. This means that more than ever before, we are prepared to move from identifying and

diagnosing harms to taking action to remediate them. This will not be easy, but now is the

moment for this work. This report is written with this task in mind: we are drawing from our experiences

inside and outside government to outline an agenda for how we—as a group of individuals,

communities, and institutions deeply concerned about the impact of AI unfolding around us—can

meaningfully confront the core problem that AI presents, and one of the most dicult challenges of our

time: the concentration of economic and political power in the hands of the tech industry—Big

Tech in particular.

There is no AI without Big Tech.

Over the past several decades, a handful of private actors have accrued power and resources that rival

nation-states while developing and evangelizing artificial intelligence as critical social infrastructure. AI

is being used to make decisions that shape the trajectory of our lives, from the deeply impactful, like

what kind of job we get and how much we’re paid; whether we can access decent healthcare and a

good education; to the very mundane, like the cost of goods on the grocery shelf and whether the route

we take home will send us into trac.

Across all of these domains, the same problems show themselves: the technology doesn’t work as

claimed, and it produces high rates of error or unfair and discriminatory results. But the visible problems

are only the tip of the iceberg. The opacity of this technology means we may not be informed when AI

is in use, or how it’s working. This ensures that we have little to no say about its impact on our lives.

2023 Landscape

6

This is underscored by a core attribute of artificial intelligence: it is foundationally

reliant on resources that are owned and controlled by only a handful of Big Tech firms.

The dominance of Big Tech in artificial intelligence plays out along three key dimensions:

1. The Data Advantage: Firms that have access to the widest and deepest swath of behavioral

data insights through surveillance will have an edge in the creation of consumer AI products.

This is reflected in the acquisition strategies adopted by tech companies, which have of late

focused on expanding this data advantage. Tech companies have amassed a tremendous

degree of economic power, which has enabled them to embed themselves as core

infrastructure within a number of industries, from health to consumer goods to education to

credit.

2. Computing Power Advantage: AI is fundamentally a data-driven enterprise that is heavily

reliant on substantial computing power to train, tune, and deploy these models. This is

expensive and runs up against material dependencies such as chips and the location of data

centers that mean eciencies of scale apply, as well as labor dependencies on a relatively small

pool of highly skilled tech workers that can most eciently use these resources.

12

Only a

handful of companies actually run their own infrastructure – the cloud and compute resources

foundational to building AI systems. What this means is that even though “AI startups” abound,

they must be understood as barnacles on the hull of Big Tech – licensing server infrastructure,

and as a rule competing with each other to be acquired by one or another Big Tech firm. We are

already seeing these firms wield their control over necessary resources to throttle competition.

For example, Microsoft recently began penalizing customers for developing potential

competitors to GPT-4, threatening to restrict their access to Bing search data.

13

3. Geopolitical Advantage: AI systems (and the companies that produce them) are being recast

not just as commercial products but foremost as strategic economic and security assets for the

nation that need to be boosted by policy, and never restrained. The rhetoric around the

US-China AI race has evolved from a sporadic talking point to an increasingly institutionalized

stance (represented by collaborative initiatives between government, military, and Big Tech

companies) that positions AI companies as crucial levers within this geopolitical fight. This

narrative conflates the continued dominance of Big Tech as synonymous with US economic

prowess, and ensures the continued accrual of resources and political capital to these

companies.

To understand how we got here, we need to look at how tech firms presented themselves in their

incipiency: their rise was characterized by marketing rhetoric promising that commercial tech would

serve the public interest, encoding democratic values like freedom, democracy, and progress. But

what’s clear now is that the companies developing and deploying AI and related technologies are

motivated by the same things that—structurally and necessarily—motivate all corporations: growth,

profit, and rosy market valuations. This has been true from the start.

13

Leah Nylen and Dina Bass, “Microsoft Threatens to Restrict Data in Rival AI Search,” March 24, 2023.

12

For example, Microsoft is even rationing access to server hardware internally for some of its AI teams to ensure it has the capacity to run GPT-4.

See Aaron Holmes and Kevin McLaughlin, “Microsoft Rations Access to AI Hardware for Internal Teams,” The Information.

2023 Landscape

7

Why “Big Tech”?

In this report, we pay special attention to policy interventions that target large tech companies.

The term “Big Tech” became popular around 2013

14

as a way to describe a handful of US-based

megacorporations, and while it doesn’t have a definite composition, today it’s typically used as

shorthand for Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft (often abbreviated as GAFAM), and

sometimes also includes companies like Uber or Twitter.

It’s a term that draws attention to the unique scale at which these companies operate: the

network eects, data, and infrastructural advantages they have amassed. Big Tech’s financial

leverage has allowed these firms to consolidate this advantage across sectors from social media

to healthcare to education and across media (like the recent pivot to virtual and augmented

realities), often through strategic acquisitions. They seek to protect this advantage from regulatory

threats through lobbying and similar non-capital strategies that leverage their deep pockets.

15

Following on from narratives around “Big Tobacco,” “Big Pharma,” and “Big Oil,” this framing draws

upon lessons from other domains where consolidation of power in industries has led to

movements to reassert public accountability. (As one commentator puts it, “society does not

prepend the label ‘Big’ with a capital B to an industry out of respect or admiration. It does so out of

loathing and fear – and in preparation for battle.”

16

) Recent name changes, like Google to Alphabet

or Facebook to Meta, also make Big Tech helpful terminology to capture the sprawl of these

companies and their continually shifting contours.

17

Focusing on Big Tech is a useful prioritization exercise for tech policy interventions for several

reasons:

● Tackling challenges that either originate from or are exemplified by Big Tech

companies can address the root cause of several key concerns: invasive data

surveillance, the manipulation of individual and collective autonomy, the consolidation of

economic power, and exacerbation of patterns of inequality and discrimination, to name a

few.

● The Big Tech business and regulatory playbook has a range of knock-on eects on

the broader ecosystem, incentivizing and even compelling other companies to fall in

line. Google and Facebook’s adoption of the behavioral advertising business model that

eectively propelled commercial surveillance into becoming the business model of the

internet is just one example of this.

17

Kean Birch Kean and Kelly Bronson, “Big Tech,” Science as Culture 31, no. 1 (January 2, 2022): 1–14.

16

Will Oremus, “Big Tobacco. Big Pharma. Big Tech?” Slate, November 17, 2017.

15

Zephyr Teachout and Lina Khan, “Market Structure and Political Law: A Taxonomy of Power,” Duke Journal of Constitutional Law & Public Policy 9,

no. 1 (2014): 37–74.

14

Nick Dyer-Witheford and Alessandra Mularoni, “Framing Big Tech: News Media, Digital Capital and the Antitrust Movement,” Political Economy of

Communication 9, no. 2 (2021): 2–20.

2023 Landscape

8

● Growing dependencies on Big Tech across the tech industry and government make

them a single point of failure. A core business strategy for these firms is to make

themselves infrastructural, and much of the wider tech ecosystem relies on them in one

way or another, from cloud computing to advertising ecosystems and, increasingly, to

payments. This makes these companies both a choke point and a single point of failure.

We’re also seeing spillover into the public sector. While a whole spectrum of vendors for AI

and tech products sells to government agencies, the dependence of government on Big

Tech aordances came into particular focus during the height of the pandemic, when

many national governments needed to rely on Big Tech infrastructure, networks, and

platforms for basic governance functions.

Finally, this report takes aim not just at the pathologies associated with these

companies, but also at the broader narratives that justify and normalize them. From

unrestricted innovation as a social good to digitization, to data as the only way to see and interpret

the world, to platformization as necessarily beneficial to society and synonymous with

progress—and regulation as chilling this progress—these narratives pervade the tech industry (and,

increasingly, government functioning as well).

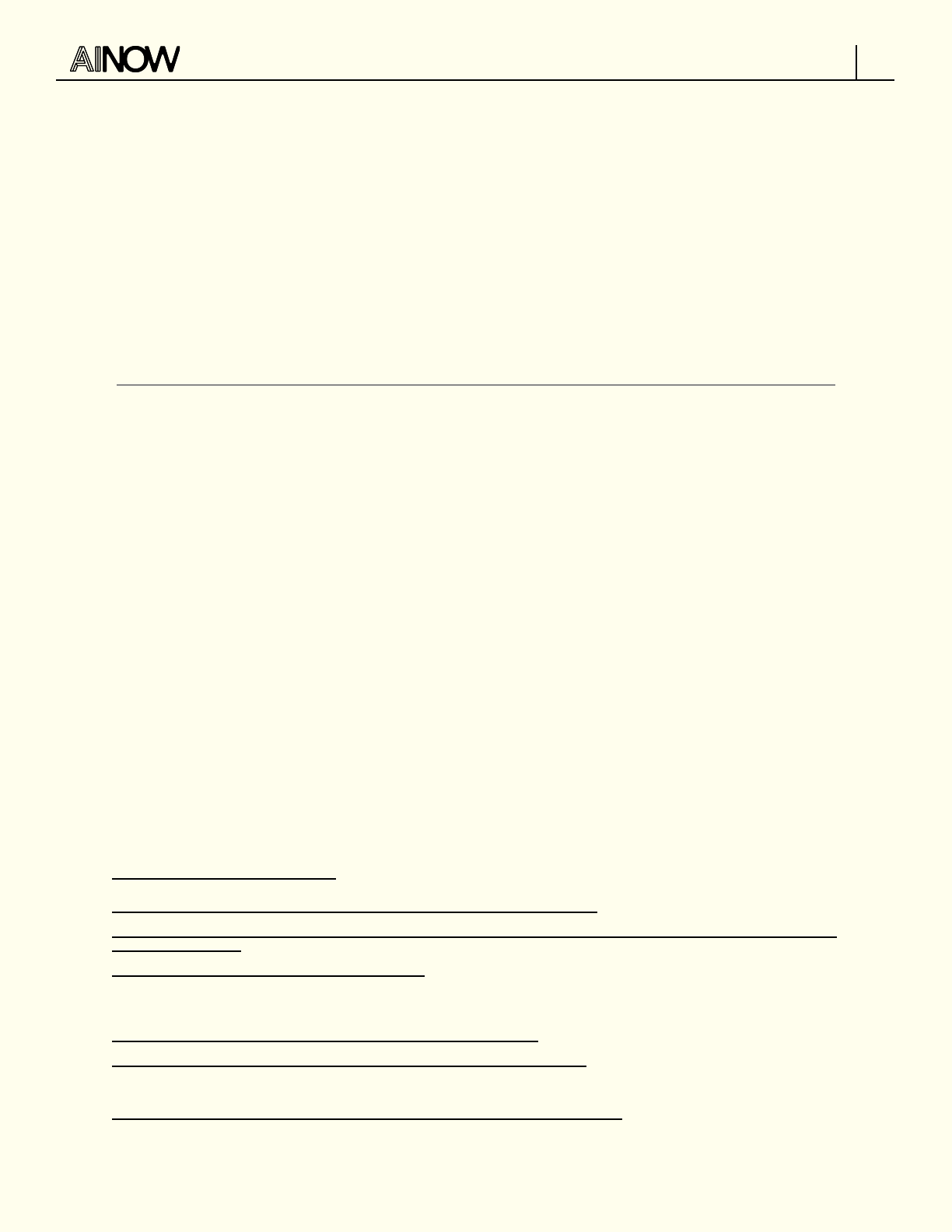

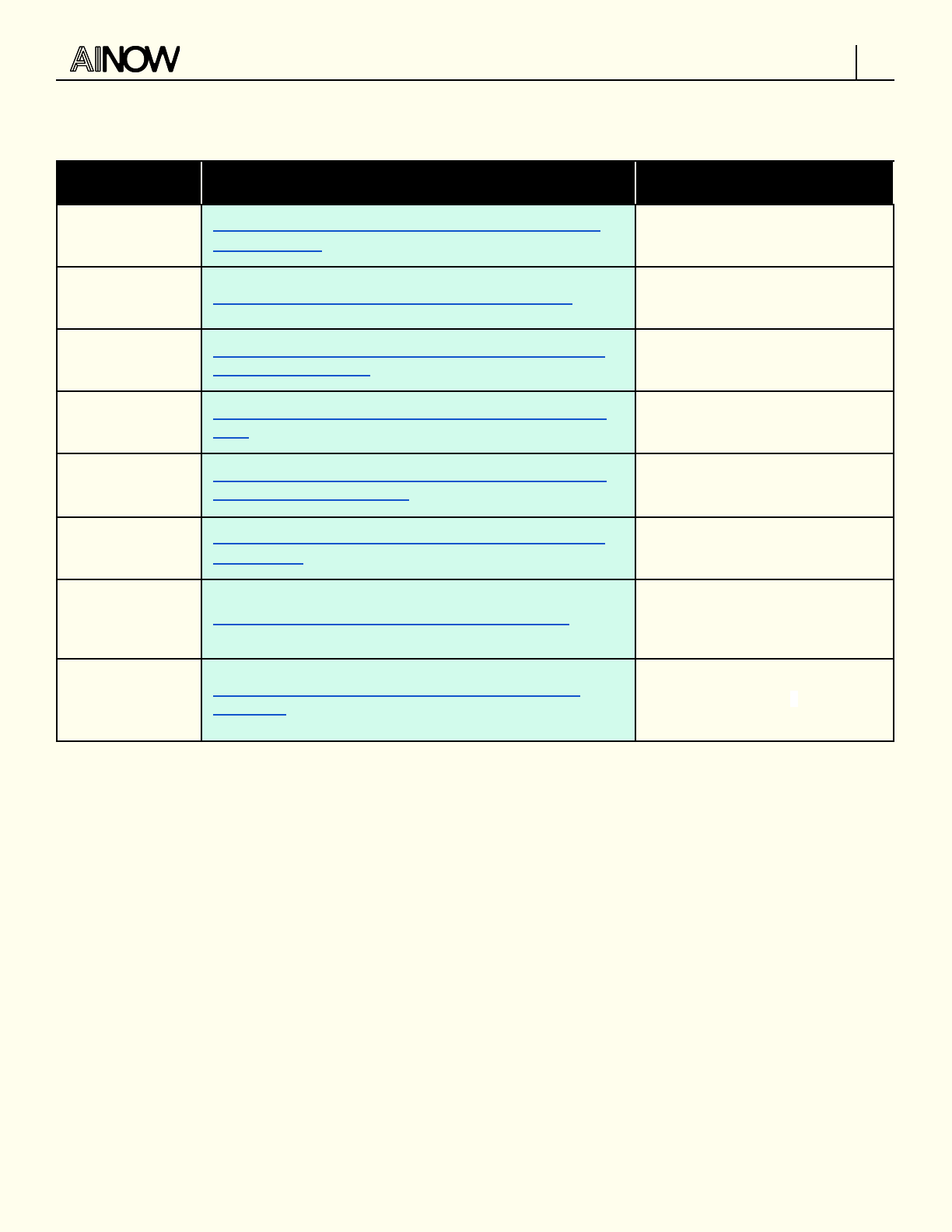

Strategic priorities

Where do we go from here? Across the chapters of this report, we oer a set of approaches that, in

concert, will collectively enable us to confront the concentrated power of Big Tech. Some of these are

bold policy reforms that oer bright-line rules and structural changes. Others aren’t in the traditional

domain of policy at all, but acknowledge the importance of non regulatory interventions such as

collective action, worker organizing, while acknowledging the role public policy can play in bolstering or

kneecapping these eorts. We also identify trendy policy responses that seem positive on their surface,

but because they fail to meaningfully address power discrepancies should be abandoned. The primary

jurisdictional focus for these recommendations is the US, although where relevant we point to policy

windows or trends in other jurisdictions (such as the EU) with necessarily global impacts.

Four strategic priorities emerge as particularly crucial for this moment:

1. Employ strategies that place the burden on companies to demonstrate that they are

not doing harm, rather than on the public and regulators to continually investigate,

identify, and find solutions for harms after they occur.

Investigative journalism and independent research has been critical to tech accountability: the hard

work of those testing opaque systems has surfaced failures that have been crucial for establishing

evidence for tech-enabled harms. But, as we outline in the section on Algorithmic Accountability, as a

policy response, audits and similar accountability frameworks dependent on third-party evaluation play

2023 Landscape

9

directly into the tech company playbook by positioning responsibility for identifying and addressing

harms outside of the company.

The finance sector oers a useful corollary for thinking this through. Much like AI, the actions taken by

large financial firms have diuse and unpredictable eects on the broader financial system and the

economy at large. It’s hard to predict any particular harm these may cause, but we know the

consequences can be severe, and the communities hit hardest are those that already experience

significant inequality. After multiple crisis cycles, there’s now widespread consensus that the onus

needs to be on companies to demonstrate that they are mitigating harms and to comply with

regulations, rather than on the broader public to root these out.

The tech sector, likewise has diuse and unpredictable eects not only on our economy, but our

information environment and labor market, among many other things. We see value in a due-diligence

approach that requires firms to demonstrate their compliance with the law rather than turn to

regulators or civil society to show where they haven’t complied—similar in orientation to how we already

regulate many goods that have significant public impact, like food and medicine. And we need

structural curbs like bright lines and no-go zones that identify types of use and domains of

implementation that should be barred in any instance, as many cities have already established by

passing bans on facial recognition. For example, in the chapter on Algorithmic Management we identify

emotion recognition as a type of technology that should never be deployed, but particularly in the

workplace: aside from the clear concerns about its use of pseudoscience and accompanying

discriminatory eects, it is fundamentally unethical for employers to seek to draw inferences about

their employees’ inner state to maximize their profit. And in Biometric Surveillance, we identify the

absence of such bright-line measures as the animating force behind a slow creep of facial recognition

and other surveillance systems into domains like cars and virtual reality.

We also need to lean further toward scrutiny of harms before they happen rather than waiting to rectify

harms after they’ve already occurred. We discuss what this might look like in the context of merger

reviews in the Toxic Competition section, advocating for an approach to merger reviews that looks to

predict and prevent abusive practices before they manifest, and in Antitrust, we break down how

needed legal reforms would render certain kinds of mergers invalid in the first place, and put the onus

on companies to demonstrate they aren’t anti-competitive.

2. Break down silos across policy areas, so we’re better prepared to address where

advancement of one policy agenda impacts others. Firms play this isolation to their

advantage.

One of the primary sources of Big Tech power is the expansiveness of their reach across markets, with

digital ecosystems that stretch across vast swathes of the economy. This means that eective tech

policy must be similarly expansive, attending to how measures adopted in the advancement of one

policy agenda ramify across other policy domains. For example, as we underscore in the section on

Toxic Competition, legitimate concerns about third-party data collection must be addressed in a way

that doesn’t inadvertently enable further concentration of power in the hands of Big Tech firms.

Disconnection between the legal and policy approaches to privacy on the one hand and competition on

the other have enabled firms to put forward self-regulatory measures like Google’s Privacy Sandbox in

2023 Landscape

10

the name of privacy that ultimately will lead to the depletion of both privacy and competition by

strengthening Google’s ability to collect information on consumers directly while hollowing out its

competitors. These disconnects can also prevent progress in one policy domain from carrying over to

another. Despite years of carefully accumulated evidence on the fallibility of AI-based content filtration

tools, we’re seeing variants of the magical thinking that AI tools will be able to scan eectively for illegal

content, crop up once again in encryption policy with the EU’s recent “chat control” client-side

scanning proposals.

18

Policy and advocacy silos can also blunt strategic creativity in ways that foreclose alliance or

cross-pollination. We’ve made progress on this front in other domains, ensuring for example that

privacy and national security are increasingly seen as consonant, rather than mutually exclusive,

objectives. But AI policy has been undermined too often by a failure to understand AI materially, as a

composite of data, algorithmic models, and large-scale computational power. Once we view AI this

way, we can understand data minimization and other approaches that limit data collection not only as

protecting consumer privacy, but as mechanisms that help mitigate some of the most egregious AI

applications, by reducing firms’ data advantage as a key source of their power and rendering certain

types of systems impossible to build. It was through data protection law that Italy's privacy regulator

was the first to issue a ban on ChatGPT

19

and, the week before that, Amsterdam's Court of Appeal ruled

automated firing and opaque algorithmic wages to be illegal.

20

FTC ocials also recently called for

leveraging antitrust as a tool to enhance worker power, including to push back against worker

surveillance.

21

This opens up space for advocates working on AI-related issues to form strategic

coalitions with those that have been leveraging these policy tools in other domains. This multivariate

approach has the added advantage of necessitating that those focused on AI-related issues form

strategic coalitions with those that have been leveraging these policy tools in other domains.

Throughout this report, we attempt to establish links between related, but often siloed domains: data

protection or competition reform as AI policy (see section on Data Minimization); Antitrust]), or AI policy

as industrial policy (see section on Algorithmic Accountability).

3. Identify when policy approaches get co-opted and hollowed out by industry, and

pivot our strategies accordingly.

The tech industry, with its billions of dollars and deep political networks, has been both nimble and

creative in its response to anything perceived as a policy threat. There are relevant lessons from the

European experience around the perils of shifting from a “rights-based” regulatory framework, as in the

GDPR, to a “risk-based” approach, as in the upcoming AI Act and how the framing of “risk” (as opposed

to rights) could tip the playing field in favor of industry-led voluntary frameworks and technical

standards.

22

Responding to the growing chorus calling for bans on facial recognition technologies in sensitive social

domains, several tech companies pivoted from resisting regulation to claiming to support it, something

they often highlighted in their marketing. The fine print showed that what these companies actually

22

Fanny Hidvegi and Daniel Leufer, “The EU should regulate AI on the basis of rights, not risks”, Access Now, February 17, 2021.

21

Elizabeth Wilkins, “Rethinking Antitrust“, March 30, 2023

20

Worker Info Exchange, “Historic Digital Rights Win for WIE and the ADCU Over Uber and Ola at the Amsterdam Court of Appeals“, April 4, 2023

19

Clothilde Goujard, “Italian Privacy Regulator Bans ChatGPT” Politico, March 31, 2023.

18

Ross Anderson, “Chat Control or Child Protection?”, University of Cambridge Computer Lab, October 13, 2022.

2023 Landscape

11

supported were soft moves positioned to undercut bolder reform. For example, Washington state’s

widely critiqued facial recognition law passed with Microsoft’s support. The bill prescribed audits and

stakeholder engagement, a significantly weaker stance than banning police use which is what many

advocates were calling for (see section on Biometrics).

For example, mountains of research and advocacy demonstrate the discriminatory impacts of AI

systems and the fact that these issues cannot be addressed solely at the level of code and data. While

the AI industry has accepted that bias and discrimination is an issue, companies have also been quick

to narrowly cast bias as a technical problem with a technical fix.

Civil society responses must be nimble in responding to Big Tech subterfuge, and we must learn to

recognize such subterfuge early. We draw from these lessons when we argue that there is

disproportionate policy energy being directed toward AI and algorithmic audits, impact assessments,

and “access to data” mandates. Indeed, such approaches have the potential to eclipse and nullify

structural approaches to curbing the harms of AI systems (see section on Algorithmic Accountability).

In an ideal world, such transparency-oriented measures would live alongside clear standards of

accountability and bright-line prohibitions. But this is not what we see happening. Instead, a steady

stream of proposals position algorithmic auditing as the primary policy approach toward AI.

Finally, we also need to stay on top of companies’ moves to evade regulatory scrutiny entirely: for

example, firms have been seeking to introduce measures in global trade agreements (see section on

Global Digital Trade) that would render regulatory eorts seeking accountability by signatory countries

presumptively illegal. And companies have sought to use promises of AI magic as a means of evading

stronger regulatory measures, such as by clinging to the familiar false argument that AI can provide a

fix for unsolvable problems, such as in content moderation.

23

4. Move beyond a narrow focus on legislative and policy levers and embrace a

broad-based theory of change.

To make progress and ensure the longevity of our wins, we must be prepared for the long game, and

author strategies that keep momentum going in the face of inevitable political stalemates. We can learn

from ongoing organizing in other domains, from climate advocacy (see section on Climate) that

identifies the long-term nature of these stakes, to worker-led organizing (see section on Algorithmic

Management) which has emerged as one of the most eective approaches to challenging and

changing tech company practice and policy. We can also learn from shareholder advocacy (see section

on Tech & Financial Capital), which uses companies’ own capital strategies to push for accountability

measures - one example is the work of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Peace using shareholder proposals

to hold Microsoft to account for human rights abuses. The Sisters also used such proposals to seek a

ban on the sale of facial recognition to government entities, and to require Microsoft to evaluate how

the company’s lobbying aligns with its stated principles.

24

Across these fronts, there is much to learn

from the work of organizers and advocates well-versed in confronting corporate power.

24

See Chris Mills Rodrigo, “Exclusive: Scrutiny Mounts on Microsoft’s Surveillance Technology,” The Hill, June 17, 2021; and Issie Lapowsky, “These

Nuns Could Force Microsoft to Put Its Money Where Its Mouth Is,” Protocol, November 19, 2021,

23

Federal Trade Commission, “Combatting Online Harms Through Innovation”, Federal Trade Commission, June 2022.

2023 Landscape

12

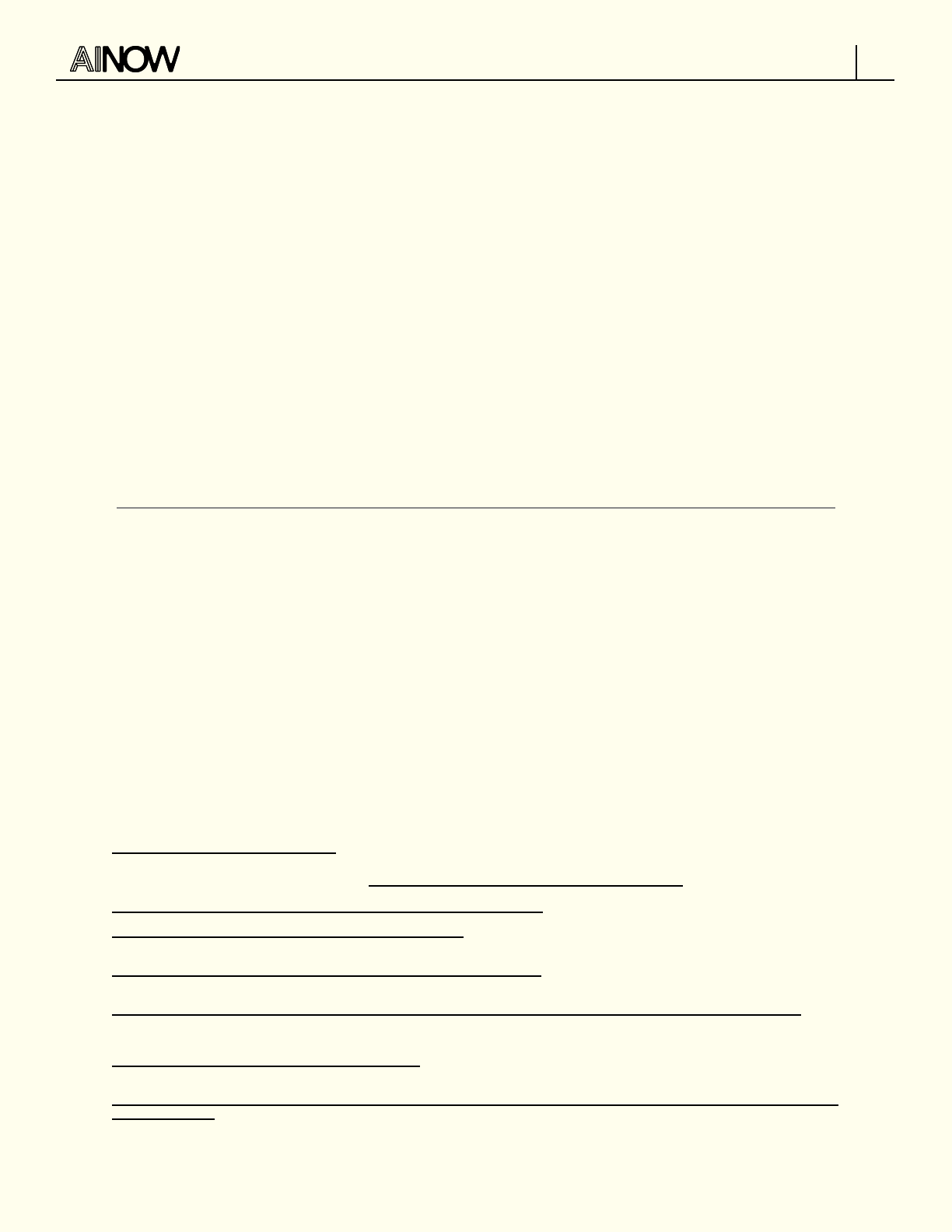

Windows for policy movement

These strategic priorities are designed to take advantage of current windows for action. We summarize

them below, and review each in more detail in the body of the report.

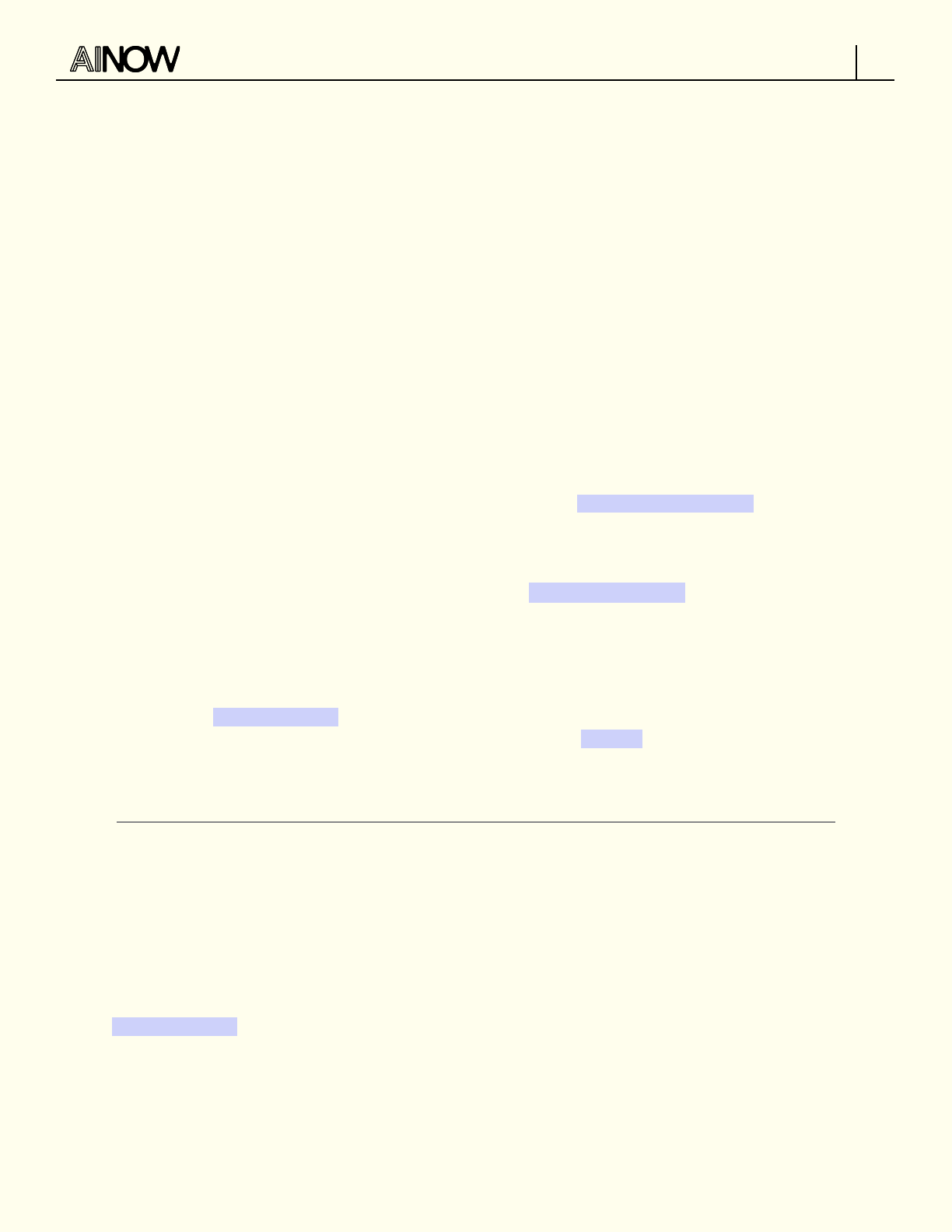

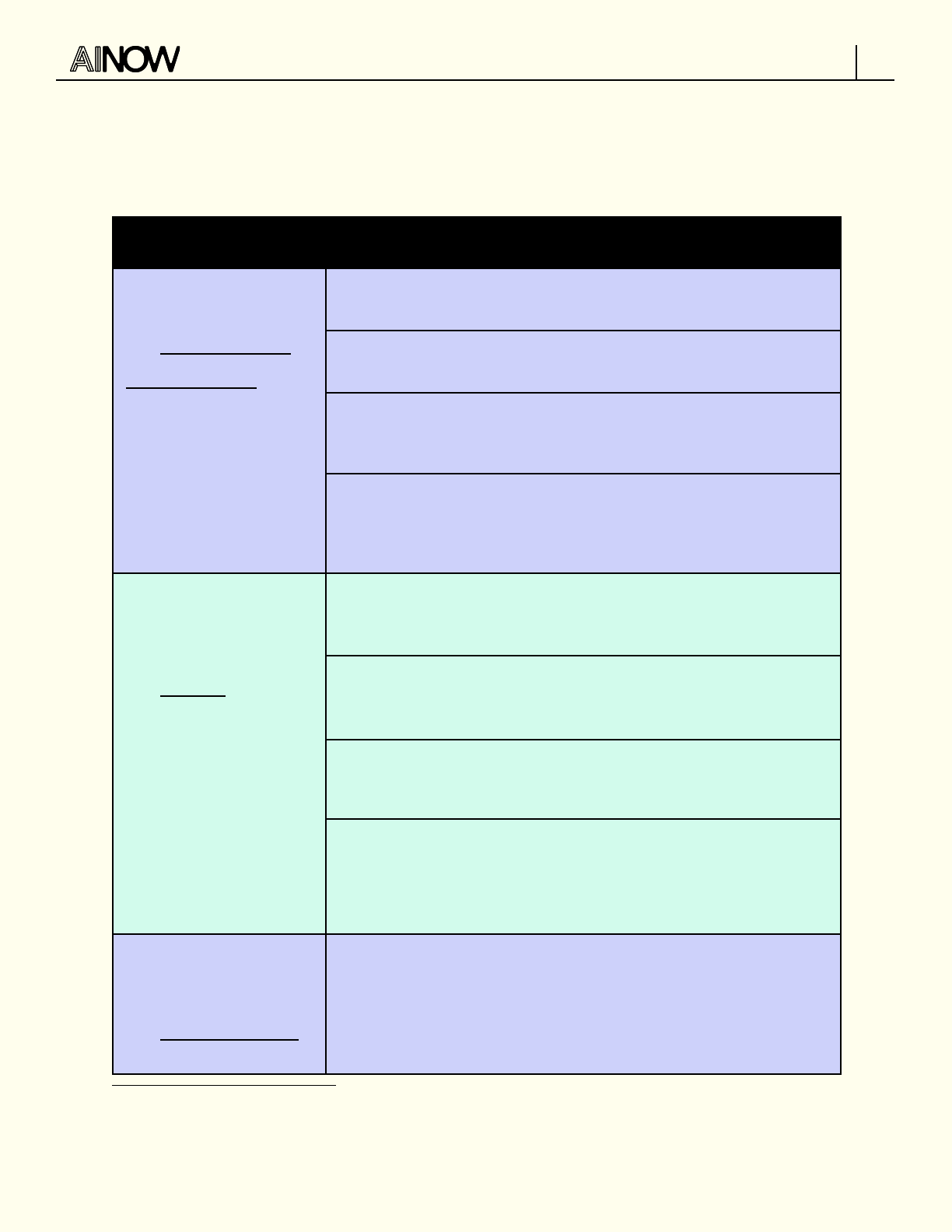

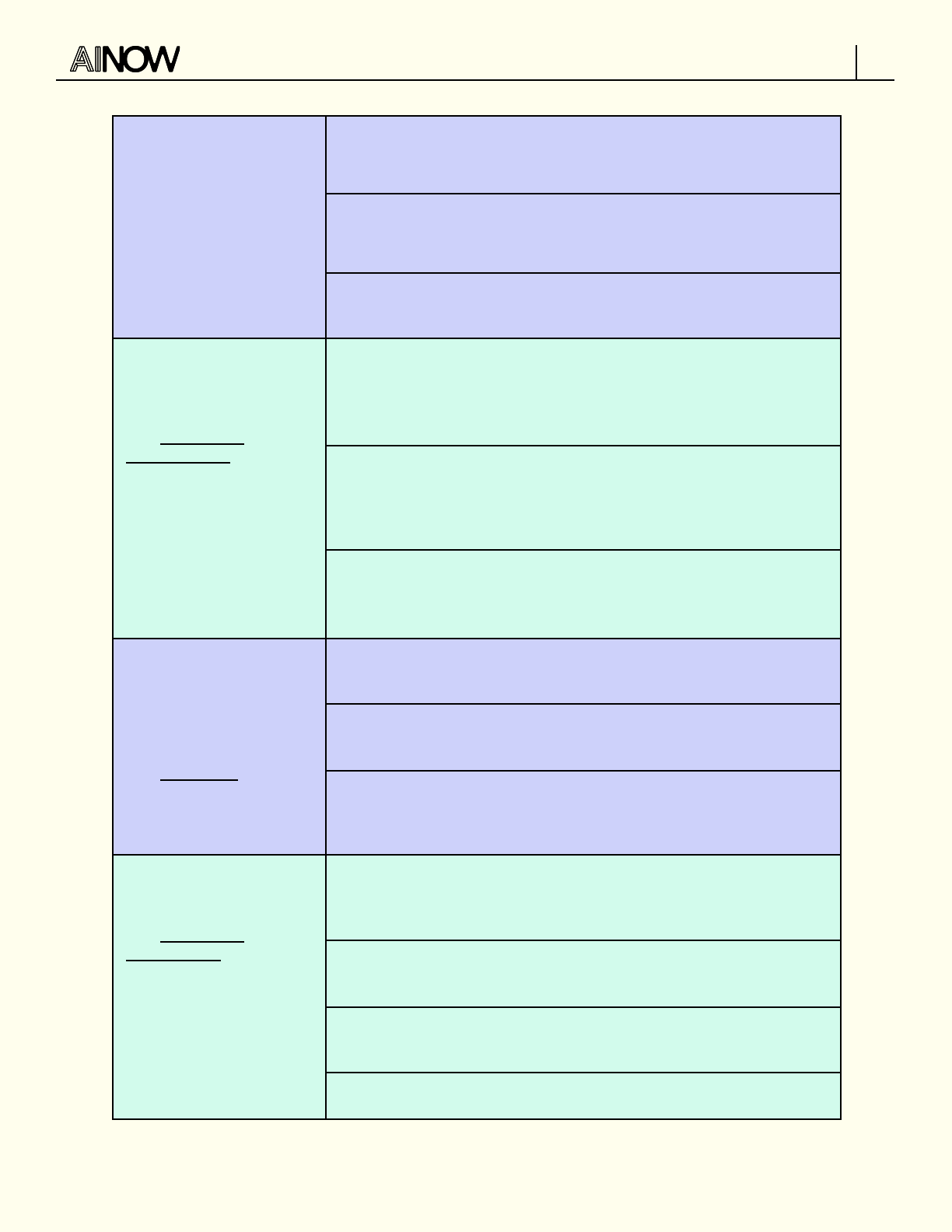

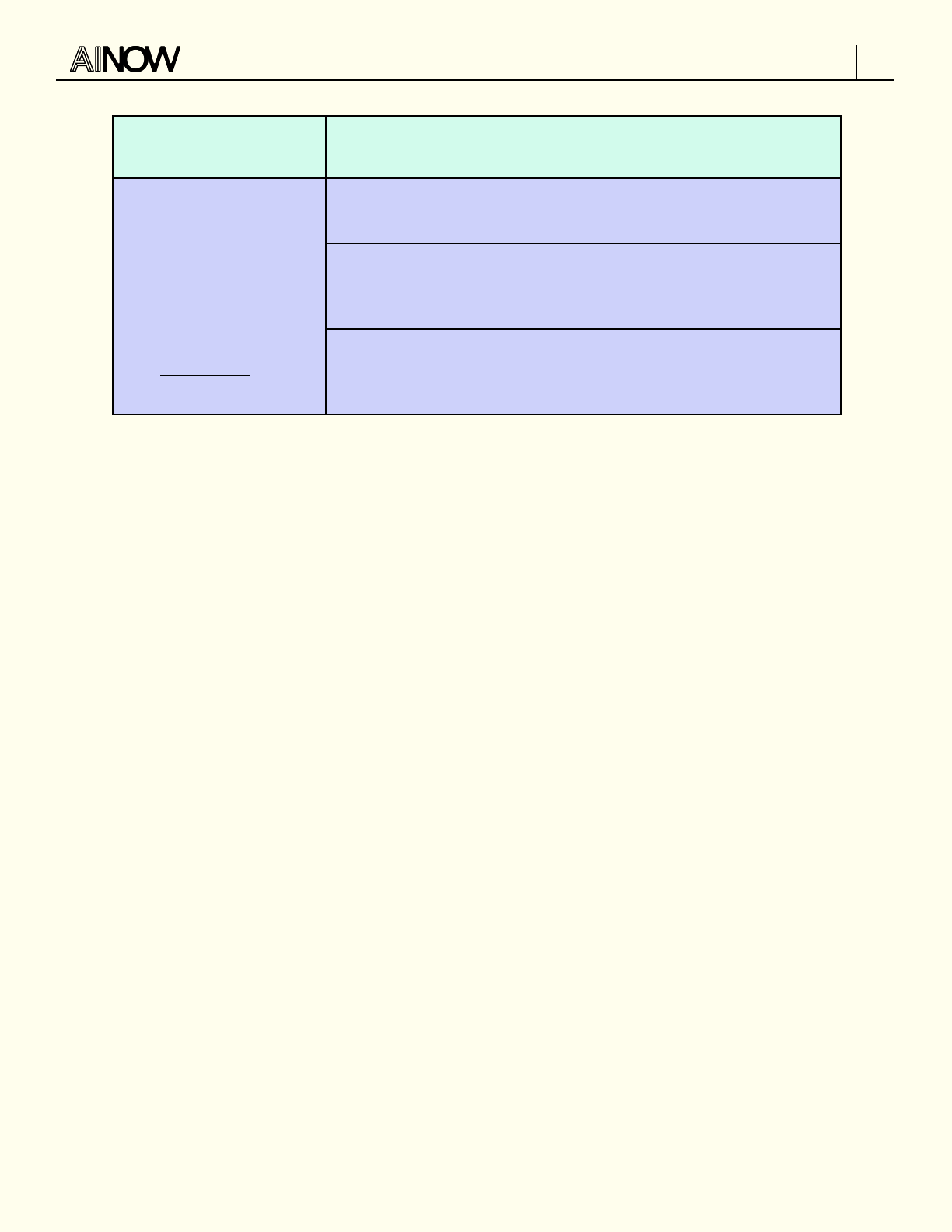

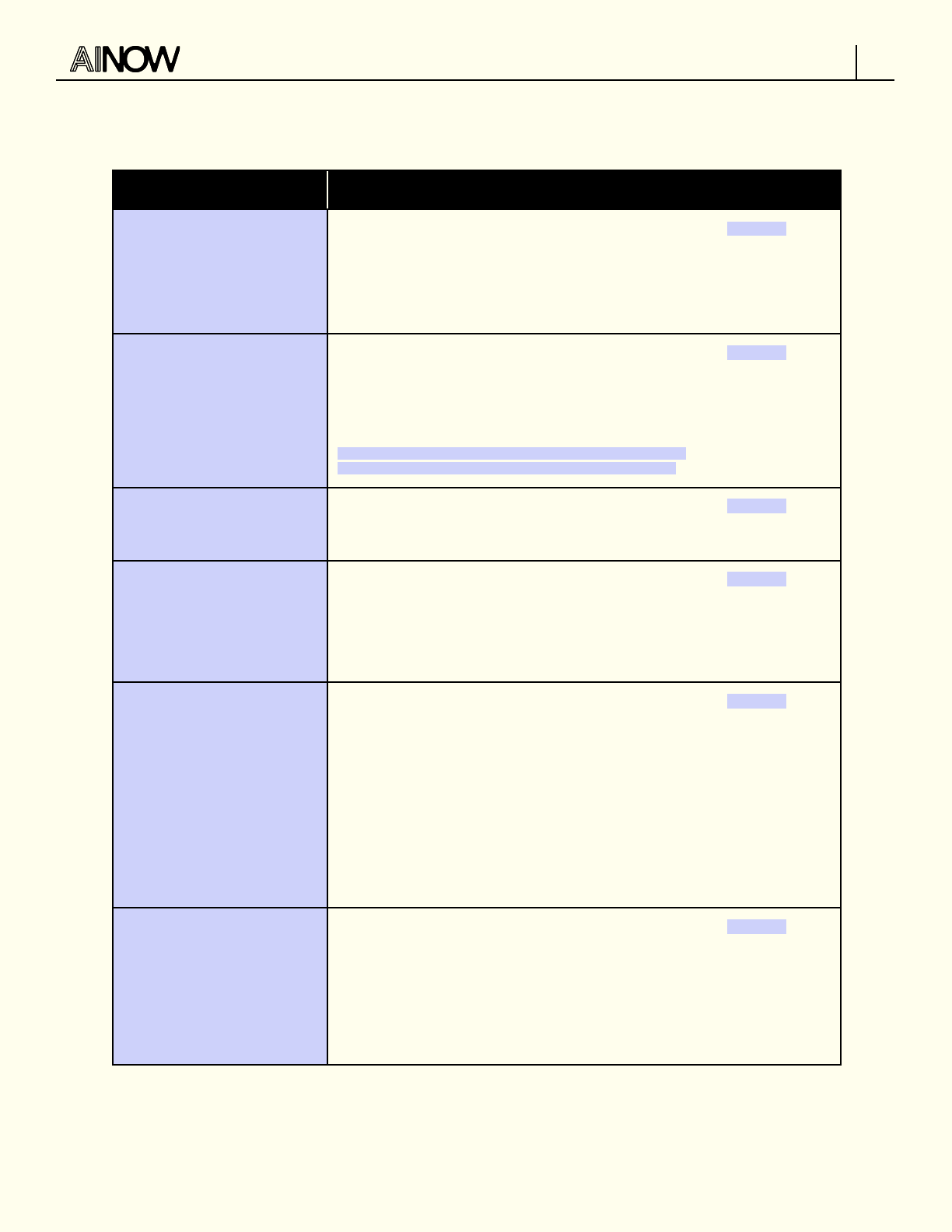

WINDOWS FOR ACTION: THE AI POLICY LANDSCAPE

Contain tech firms’ data

advantage.

See: Toxic Competition

Data minimization

Data policy is AI policy, and steps taken to curb companies’ data

advantage are a key lever in limiting concentration.

Create bright-line rules that limit firms’ ability to collect data on

consumers or produce data about them (also known as data minimization).

Connect privacy and competition law both in enforcement and in the

development of AI policy. Firms are using these disjuncts to their own

advantage.

Reform the merger guidelines and enforcement measures such that

consolidation of data advantages receives scrutiny as part of determining

whether to allow a merger, and enable enforcers to intervene to stop

abusive practices before the harms take place.

Build support for

competition reforms as

a key lever to reduce

concentration in tech.

See: Antitrust

Enforce competition laws by aggressively curbing mergers that expand

firms’ data advantage and investigating and penalizing companies when

they engage in anti-competitive behaviors.

Be wary of US versus China “AI race” rhetoric used for deregulatory

arguments in policy debates on competition, privacy, and algorithmic

accountability.

Pass the full package of antitrust bills from th e 117th Congress to give

antitrust enforcers stronger tools to challenge abusive practices specific

to the tech industry.

Integrate competition analysis across all tech policy domains – identifying

places where platform companies might take advantage of privacy

measures to consolidate their own advantage, for example, or how

concentration in the cloud market has follow-on eects for security by

distributing risk systemically.

25

Regulate ChatGPT and

other large-scale

models.

See: General Purpose AI

Apply lessons from the ongoing debate on the EU AI Act to prevent

regulatory carveouts for “general-purpose AI”: large language models

(LLMs) and other similar technologies carry systemic risks; their ability to

be fine-tuned toward a range of uses requires more regulatory scrutiny,

not less.

25

For example, a 2017 outage in Amazon Web Service’s S3 server took out several healthcare and hospital systems: Casey Newton, “How a typo took

down S3, the backbone of the internet”, The Verge, March 2, 2017,

2023 Landscape

13

Regulate ChatGPT and

other large-scale

models. (CONT.)

Mandate documentation requirements that can provide the evidence to

ensure developers of these models are held accountable for data and

design choices.

Enforce existing law on the books to create public accountability in the

rollout of generative AI systems and prevent harm to consumers and

competition.

Closely scrutinize claims to ‘openness’; generative AI has structural

dependencies on resources available to only a few firms.

Displace audits as the

primary policy response

to harmful AI.

See: Algorithmic

Accountability

Audits and data-access proposals should not be the primary policy

response to harmful AI. These approaches fail to confront the power

imbalances between Big Tech and the public, and risk further entrenching

power in the tech industry.

Closely scrutinize claims from a burgeoning audit economy with

companies oering audits-as-a-service despite no clarity on the

standards and methodologies for algorithmic auditing, nor consensus on

their definitions of risk and harm.

Impose strong structural curbs on harmful AI, such as bans, moratoria,

and rules that put the burden on companies to demonstrate that they are

fit for public and/or commercial release.

Future-proof against

the quiet expansion of

biometric surveillance

into new domains like

cars.

See: Biometrics

Develop comprehensive bright-line rules to future-proof biometric

regulation from changing forms and use cases.

Make sure biometric regulation addresses broader inferences, beyond just

identification.

Impose stricter enforcement of data minimization provisions that exist in

data protection laws globally as a way to curb the expansion of biometric

data collection in new domains like virtual reality and automobiles.

Enact strong curbs on

worker surveillance.

See: Algorithmic

Management

Worker surveillance is fundamentally about employers gaining and

maintaining control over workers. Enact policy measures that even the

playing field.

Establish baseline worker protections from algorithmic management and

workplace surveillance.

Shift the burden of proof to developers and employers and away from

workers.

Establish clear red lines around domains (e.g., automated hiring and firing)

2023 Landscape

14

and types of technology (e.g., emotion recognition) that are inappropriate

for use in any context.

Prevent “international

preemption” by digital

trade agreements that

can be used to weaken

national regulation on

algorithmic

accountability and

competition policy.

See: Digital Trade

Nondiscrimination prohibitions in trade agreements should not be used to

protect US Big Tech companies from competition regulation abroad.

Expansive and absolute-secrecy guarantees for source code and

algorithms in trade agreements should not be used to undercut eorts to

enact laws on algorithmic transparency.

Upcoming trade agreements like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework

should instead be used to set a more a progressive baseline for digital

policy.

It’s time to move: years of critical work and organizing has outlined a clear diagnosis of the problems we

face, regulators are primed for action, and we have strategies ready to be deployed immediately for this

eort. We’ll also need more: those engaged in this work are out-resourced and out-flanked amidst a

significant uptick in industry lobbying and a growing attack on critical work, from companies firing AI

Ethics teams to universities shutting down critical research centers. And we face a hostile narrative

landscape. The surge in AI hype that opened 2023 has moved things backwards, re-introducing the

notion that AI is associated with ‘innovation’ and ‘progress’ and drawing considerable energy toward

far-o hypotheticals and away from the task at hand.

We intend this report to provide strategic guidance to inform the work ahead of us, taking a bird’s eye

view of the landscape and of the many levers we can use to shape the future trajectory of AI - and the

tech industry behind it - to ensure that it is the public, not industry, that this technology serves – if we

let it serve at all.

2023 Landscape

15

Large Scale AI Models

chatGPT And More: Large

Scale AI Models Entrench

Big Tech Power

Industry is attempting to stave o regulation, but large-scale AI

needs more scrutiny, not less.

1. Large-scale general purpose AI models (such as GPT-3.5 and its user-facing

application chatGPT) are being promoted by industry as “foundational” and a major

turning point for scientific advancement in the field. They are also often associated

with slippery definitions of “open source.”

These narratives distract from what we call the “pathologies of scale” that become

more entrenched every day: large-scale AI models are still largely controlled by Big

Tech firms because of the enormous computing and data resources they require, and

also present well-documented concerns around discrimination, privacy and security

vulnerabilities, and negative environmental impacts.

Large-scale AI models like Large Language Models (LLMs) have received the most hype, and

fear-mongering, over the past year. Both the excitement and anxiety

26

around these systems serve to

reinforce the notion that these models are 'foundational' and a major turning point for advancement in

the field, despite manifold examples where these systems fail to provide meaningful responses to

26

Future of Life Institute. “Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter.” Accessed March 29, 2023.

https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/.; Harari, Yuval, Tristan Harris, and Aza Raskin. “Opinion | You Can Have the Blue Pill

or the Red Pill, and We’re Out of Blue Pills.” The New York Times, March 24, 2023, sec. Opinion.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/24/opinion/yuval-harari-ai-chatgpt.html.

2023 Landscape

16

prompts.

27

But the narratives associated with these systems distract from what we call the 'pathologies

of scale' that this emergent framing serves to both highlight and distract from. The term “foundational,”

for example, was introduced by Stanford University when announcing a new center of the same name

in early 2022,

28

in the wake of the publication of an article listing the many existential harms associated

with LLMs.

29

In notably fortuitous timing, the introduction of these models as “foundational’’ aimed to

equate them (and those espousing them) with unquestionable scientific advancement, a stepping

stone on the path to “Artificial General Intelligence”

30

(another fuzzy term evoking science-fiction

notions of replacing or superseding human intelligence) thereby making their wide-scale adoption

inevitable.

31

These discourses have since returned to the foreground following the launch of Open AI’s

newest LLM-based chatbot, chatGPT.

On the other hand, the term “general purpose AI” (GPAI) is being used in policy instruments like the EU’s

AI Act to underscore that these models have no defined downstream use and can be fine-tuned to

apply in specific contexts.

32

It has been wielded to make arguments such as because these systems

lack clear intention or defined objectives, they should be regulated dierently or not at all - eectively

creating a major loophole in the law (more on this in Section 2 below).

33

Such terms deliberately obscure another fundamental feature of these models: they currently require

computational and data resources at a scale that ultimately only the most well-resourced companies

33

Alex C. Engler, “To Regulate General Purpose AI, Make the Model Move,” Tech Policy Press, November 10, 2022,

https://techpolicy.press/to-regulate-general-purpose-ai-make-the-model-move.

32

The EU Council’s draft or “general position” on the AI Act text defines General Purpose AI (GPAI) as an AI system that “that – irrespective of how it

is placed on the market or put into service, including as open source software – is intended by the provider to perform generally applicable functions

such as image and speech recognition, audio and video generation, pattern detection, question answering, translation and others; a general purpose

AI system may be used in a plurality of contexts and be integrated in a plurality of other AI systems.” See Council of the European Union, “Proposal

for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act)

and Amending Certain Union Legislative Acts – General Approach,” November 25, 2022,

https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-14954-2022-INIT/en/pdf; see also Future of Life Institute and University College London’s

proposal to define GPAI as an AI system “that can accomplish or be adapted to accomplish a range of distinct tasks, including some for which it was

not intentionally and specifically trained.” Carlos I. Gutierrez, Anthony Aguirre, Risto Uuk, Claire C. Boine, and Matija Franklin, “A Proposal for a

Definition of General Purpose Artificial Intelligence Systems,” Future of Life Institute, November 2022,

https://futureoflife.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/SSRN-id4238951-1.pdf.

31

See National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource Task Force, “Strengthening and Democratizing the U.S. Artificial Intelligence Innovation

Ecosystem: An Implementation Plan for a National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource,” January 2023,

https://www.ai.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/NAIRR-TF-Final-Report-2023.pdf; and Special Competitive Studies Project, “Mid-Decade

Challenges to National Competitiveness,” September 2022,

https://www.scsp.ai/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/SCSP-Mid-Decade-Challenges-to-National-Competitiveness.pdf.

30

See Sam Altman, “Planning for AGI and beyond”, March 2023, https://openai.com/blog/planning-for-agi-and-beyond.

29

Emily Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, Shmargaret Shmitchell, “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too

Big?” FAccT ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, March 2021,

https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

28

See the Center for Research on Foundation Models, Stanford University, https://crfm.stanford.edu; and Margaret Mitchell (@mmitchell_ai),

“Reminder to everyone starting to publish in ML: ‘Foundation models’ is *not* a recognized ML term; was coined by Stanford alongside announcing

their center named for it; continues to be pushed by Sford as *the* term for what we’ve all generally (reasonably) called ‘base models’,” Twitter, June

8, 2022, 4:01 p.m., https://twitter.com/mmitchell_ai/status/1534626770820792320.

27

See Greg Noone, “‘Foundation models’ may be the future of AI. They’re also deeply flawed,” Tech Monitor, November 11, 2021 (updated February 9,

2023), https://techmonitor.ai/technology/ai-and-automation/foundation-models-may-be-future-of-ai-theyre-also-deeply-flawed; Dan McQuillan,

“We Come to Bury ChatGPT, Not to Praise It,” danmcquillan.org, February 6, 2023, https://www.danmcquillan.org/chatgpt.html; Ido Vock, “ChatGPT

Proves That AI Still Has a Racism Problem,” New Statesman, December 9, 2022,

https://www.newstatesman.com/quickfire/2022/12/chatgpt-shows-ai-racism-problem; Janice Gassam Asare, “The Dark Side of ChatGPT,” Forbes,

January 28, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/janicegassam/2023/01/28/the-dark-side-of-chatgpt; and Billy Perrigo, “Exclusive: OpenAI Used

Kenyan Workers on Less Than $2 Per Hour to Make ChatGPT Less Toxic,” Time, January 18, 2023,

https://time.com/6247678/openai-chatgpt-kenya-workers.

2023 Landscape

17

can aord to sustain.

34

For a sense of the figures, some estimates suggest it will cost 3 million dollars a

month to run chatGPT

35

and 20 million dollars in computing costs to train Pathways Language Model

(PaLM), a recent LLM from Google.

36

Currently only a handful of companies with incredibly vast

resources are able to build them. That’s why the majority of existing large-scale AI models have been

almost exclusively developed by Big Tech, especially Google (Google Brain, Deepmind), Meta, and

Microsoft (and its investee OpenAI). This includes many o-the-shelf, pretrained AI models that are

oered as part of cloud AI services, a market already concentrated in Big Tech players, such as AWS

(Amazon), Google Cloud (Alphabet), and Azure (Microsoft). Even if costs are lower or come down as

these systems are deployed at scale (and this is a hotly contested claim

37

), Big Tech is likely to retain a

first mover advantage, having had the time and market experience needed to hone their underlying

language models and to develop invaluable in-house expertise. Smaller businesses or start ups may

consequently struggle to successfully enter this field, leaving the immense processing power of LLMs

concentrated in the hands of a few Big Tech firms.

38

This market reality cuts through growing narratives that highlight the potential for “open-source” and

“community or small and medium enterprise (SME)-driven” GPAI projects or even the conflation of GPAI

as synonymous with open source (as we’ve seen in discussions around the EU’s AI Act).

39

In September

2022, for example, a group of ten industry associations led by the Software Alliance (or BSA) published

a statement opposing the inclusion of any legal liability for the developers of GPAI models.

40

Their

headline argument was that this would “severely impact open source development in Europe” as well as

“undermine AI uptake, innovation, and digital transformation.”

41

The statement leans on hypothetical

examples that present a caricature of both how GPAI models work and what regulatory intervention

would entail—the classic case cited is of an individual developer creating an open source

document-reading tool and being saddled by regulatory requirements around future use cases it can

neither predict nor control.

41

BSA, “BSA Leads Joint Industry Statement on the EU Artificial Intelligence Act and High-Risk Obligations for General Purpose AI.”

40

See BSA | The Software Alliance, “BSA Leads Joint Industry Statement on the EU Artificial Intelligence Act and High-Risk Obligations for General

Purpose AI,” press release, September 27, 2022, ; and BSA, “Joint Industry Statement on the EU Artificial Intelligence Act and High-Risk Obligations

for General Purpose AI,” September 27, 2022, https://www.bsa.org/files/policy-filings/09272022industrygpai.pdf.

39

Ryan Morrison, “EU AI Act Should ‘Exclude General Purpose Artificial Intelligence’ – Industry Groups,” Tech Monitor, September 27, 2022,

https://techmonitor.ai/technology/ai-and-automation/eu-ai-act-general-purpose.

38

Richard Waters, “Falling costs of AI may leave its power in hands of a small group”, Financial Times, March 9, 2023,

https://www.ft.com/content/4fef2245-5559-4661-950d-6eb803fea329?accessToken=zwAAAYbcxVeYkc9P7yJFVVlGYdOVDW64A_6jKQ.MEUCIGlMq

MvMjHTpGNJ0wUPHEfszGIyW0kEj4nsjoDxiv6kAAiEAlqOLnI5WWEh8Yc9lLndBenSTWlzX4rs1T45XIQ3LEgs&sharetype=gift&token=e4fcef47-71f7-4e8

d-8958-b51acc82d2b8.

37

Andrew Lohn and Micah Musser, “AI and Compute”, Center for Security and Emerging Technology,

https://cset.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/AI-and-Compute-How-Much-Longer-Can-Computing-Power-Drive-Artificial-Intelligence-Progre

ss_v2.pdf

36

Lennart Heim, “Estimating PaLM's training cost,” April 5, 2022, https://blog.heim.xyz/palm-training-cost; Peter J. Denning and Ted G. Lewis,

“Exponential Laws of Computing Growth,” Communications of the ACM 60, no. 1 (January 2017):54–65,

https://cacm.acm.org/magazines/2017/1/211094-exponential-laws-of-computing-growth/abstract.

35

See Tom Goldstein (@tomgoldsteincs), “I estimate the cost of running ChatGPT is $100K per day, or $3M per month. This is a

back-of-the-envelope calculation. I assume nodes are always in use with a batch size of 1. In reality they probably batch during high volume, but

have GPUs sitting fallow during low volume,” Twitter, December 6, 2022, 1:34 p.m.,

https://twitter.com/tomgoldsteincs/status/1600196995389366274; and MetaNews, “Does ChatGPT Really Cost $3M a Day to Run?” December 21,

2022, https://metanews.com/does-chatgpt-really-cost-3m-a-day-to-run.

34

See Ben Cottier, “Trends in the dollar training cost of machine learning systems”, Epoch, January 31, 2023,

https://epochai.org/blog/trends-in-the-dollar-training-cost-of-machine-learning-systems; Jerey Dastin and Stephen Nellis, “For tech giants, AI

like Bing and Bard poses billion-dollar search problem”, Reuters, February 22, 2023,

https://www.reuters.com/technology/tech-giants-ai-like-bing-bard-poses-billion-dollar-search-problem-2023-02-22/; Jonathan Vanian and Kif

Leswing, “ChatGPT and generative AI are booming, but the costs can be extraordinary”, CNBC, March 13, 2023,

https://www.cnbc.com/2023/03/13/chatgpt-and-generative-ai-are-booming-but-at-a-very-expensive-price.html?utm_term=Autofeed&utm_me

dium=Social&utm_content=Main&utm_source=Twitter#Echobox=1678712441; Dan Gallagher, “Microsoft and Google Will Both Have to Bear AI’s

Costs”, WSJ, January 18, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/microsoft-and-google-will-both-have-to-bear-ais-costs-11674006102; Christopher

Mims, “The AI Boom That Could Make Google and Microsoft Even More Powerful,” Wall Street Journal, February 11, 2023,

https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-ai-boom-that-could-make-google-and-microsoft-even-more-powerful-9c5dd2a6; and Diane Coyle,

“Preempting a Generative AI Monopoly,” Project Syndicate, February 2, 2023,

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/preventing-tech-giants-from-monopolizing-artificial-intelligence-chatbots-by-diane-coyle-2023-

02.

2023 Landscape

18

The discursive move here is to conflate “open source,” which has a specific meaning related to

permissions and licensing regimes, with the intuitive notion of being “open” in that they are accessible

for downstream use and adaptation (typically through Application Programming Interfaces, or APIs).

The latter is more akin to “open access,” though even in that sense they remain limited since they only

share the API, rather than the model or training data sources.

42

In fact, in OpenAI’s paper announcing its

GPT-4 model, the company said it would not provide details about the architecture, model size,

hardware, training compute, data construction or training method used to develop GPT-4, other than

noting it used its Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback approach, asserting competitive and

safety concerns. Running directly against the current push to increase firms’ documentation

processes,

43

such moves compound what has already been described as a reproducibility crisis in

machine learning-based science, in which claims about the capabilities of AI-based models cannot be

validated or replicated by others.

44

Ultimately, this form of deployment only serves to increase Big Tech firms’ revenues and entrench their

strategic business advantage.

45

While there are legitimate reasons to consider potential downstream

harms associated with making such systems widely accessible,

46

even when projects might make their

code publicly available and meet other definitions of open source, the vast computational requirements

of these systems mean that dependencies between these projects and the commercial marketplace

will likely persist.

47

47

See Coyle, “Preempting a Generative AI Monopoly.”

46

Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor, “The LLaMA is Out of the Bag. Should We Expect a Tidal Wave of DIsinformation?” Knight First Amendment

Institute (blog), March 6, 2023. https://knightcolumbia.org/blog/the-llama-is-out-of-the-bag-should-we-expect-a-tidal-wave-of-disinformation

45

A report by the UK’s Competition & Markets Authority (CMA) points to how Google’s “open” approach with its Android OS and Play Store (in

contrast to Apple’s) proved to be a strategic advantage that eventually led to similar outcomes in terms of revenues and strengthening its

consolidation over various parts of the mobile phone ecosystem. See Competition & Markets Authority, “Mobile Ecosystems: Market Study Final

Report,” June 10, 2022,

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1096277/Mobile_ecosystems_final_report_-

_full_draft_-_FINAL__.pdf.

44

Sayash Kapoor and Arvind Narayanan. “Leakage and the Reproducibility Crisis in ML-based Science.” arXiv, July 14, 2022.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2207.07048

43

Margaret Mitchell, Simone Wu, Andrew Zaldivar, Parker Barnes, Lucy Vasserman, Ben Hutchinson, Elena Spitzer, Inioluwa Deborah Raji, Timnit

Gebru, “Model Cards for Model Reporting, arXiv, January 14, 2019, https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.03993; Emily Bender and Batya Friedman, “Data

Statements for Natural Language Model Processing: Toward Mitigating System Bias and Enabling Better Science”, Transactions of the Association

for Computational Linguistics, 6 (2018): 587-604. https://aclanthology.org/Q18-1041/; Timnit Gebru, Jamie Morgenstern, Briana Vecchione, Jennifer

Wortman Vaughan, Hanna Wallach, Hal Daumé Iii, and Kate Crawford, "Datasheets for Datasets." Communications of the ACM 64, no. 12 (2021):

86-92. https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.09010

42

Peter Suber, Open Access (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019), https://openaccesseks.mitpress.mit.edu.

2023 Landscape

19

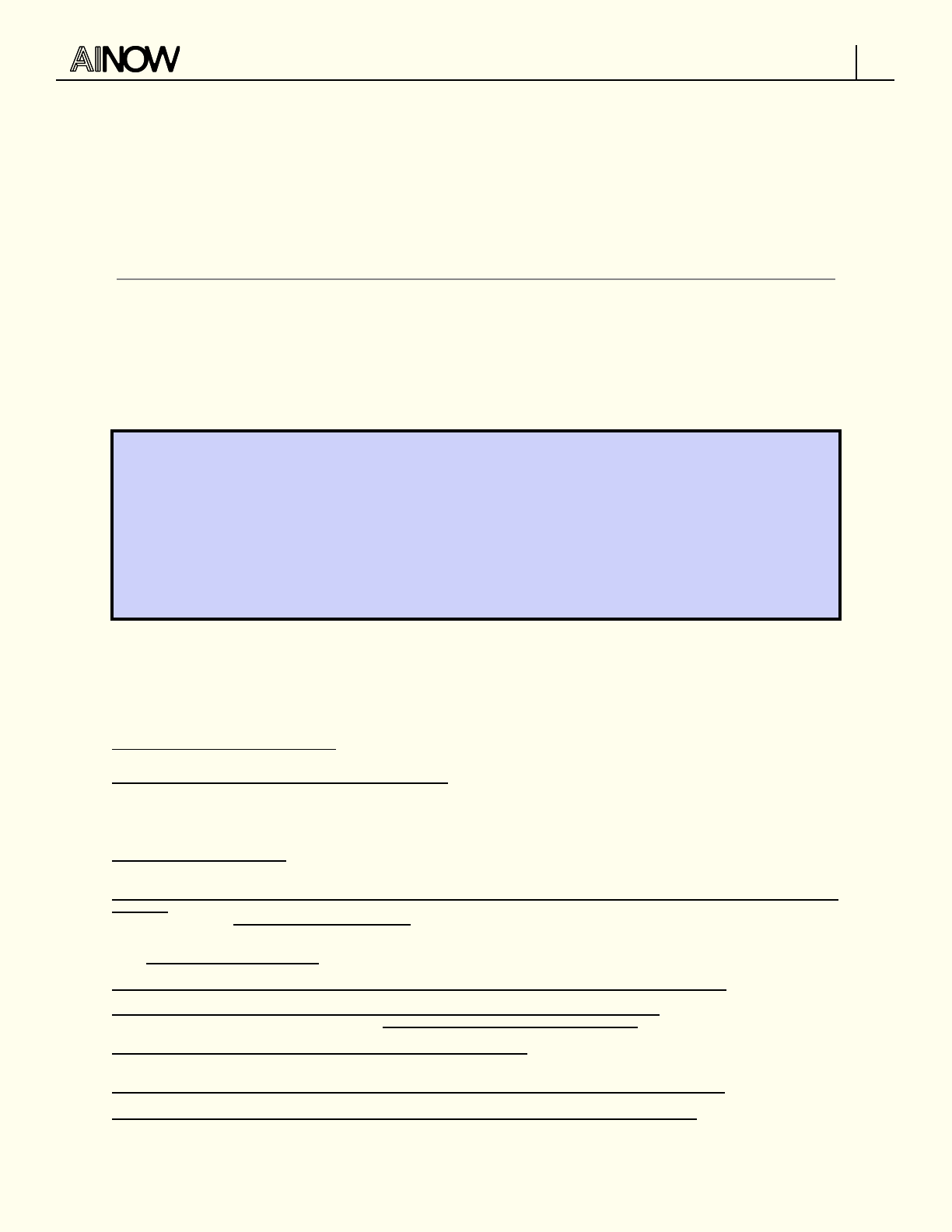

On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be

Too Big? By Dr. Emily M. Bender, Dr. Timnit Gebru, Angelina

McMillan-Major, and Dr. Margaret Mitchell

“Are ever larger LMs inevitable or necessary? What costs are associated with this

research direction and what should we consider before pursuing it?”

In 2021, Dr. Emily M. Bender, Dr. Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Dr. Margaret Mitchell

warned against the potential costs and harms of large language models (LLMs) in a paper titled On

the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?.

48

The paper led to Google

forcing out both Gebru and Mitchell from their positions as the co-leads of Google’s Ethical AI

team.

49

This paper could not have been more prescient in identifying pathologies of scale that aict

LLMs. As public discourse is consumed by breathless hype around chatGPT and other LLMs as an

unarguable advancement in science, this research oers sobering reminders of the serious

concerns that aict these kinds of models. Rather than uncritically accept these technologies as

synonymous with progress, the arguments advanced in the paper raise existential questions to if,

not how, society should be building them at all. The key concerns raised in the paper are as

follows:

Environmental and Financial Costs

LLMs are hugely energy intensive to train and produce large CO

2

emissions. Well-documented

environmental racism means that marginalized people and people from the Majority World/Global

South are more likely to experience the harms caused by heightened energy consumption and

CO

2

emissions even though they are also least likely to experience the benefits of these models.

Additionally, the high cost of entry and training these models means that only a small global elite

is able to develop and benefit from LLMs. They argue that environmental and financial costs

should become a top consideration in Natural Language Processing (NLP) research.

Unaccountable Training Data

“In accepting large amounts of web text as ‘representative’ of ‘all’ of humanity we

risk perpetuating dominant viewpoints, increasing power imbalances, and further

reifying inequality.”

The use of large and uncurated training data sets risks creating LLMs that entrench dominant,

hegemonic views. The large size of these training data sets does not guarantee diversity, as they

49

Metz, Cade, and Daisuke Wakabayashi. “Google Researcher Says She Was Fired Over Paper Highlighting Bias in A.I.” The New York Times, December

3, 2020, sec. Technology. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/03/technology/google-researcher-timnit-gebru.html.

48

Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language

Models Be Too Big? .” In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 610–23. FAccT ’21. New York,

NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

2023 Landscape

20

are often scraped from websites that exclude the voices of marginalized people due to issues

such as inadequate Internet access, underrepresentation, filtering practices, or harassment. These

data sets run the risk of ‘value-lock’ or encoding harmful bias into LLMs that are dicult to

thoroughly audit.

Creating Stochastic Parrots

Bender et al. further warn that the pursuit of LLM benchmarks may be a misleading direction for

research, as these models have access to form, but not meaning. They observe that “an LM is a

system for haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms it has observed in its vast

training data, according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any

reference to meaning: a stochastic parrot”. As stochastic parrots, these models are likely to absorb

hegemonic worldviews from their training data and produce outputs that contain both subtle

forms of stereotyping and outright abusive language. They can also lead to harms based on

translation errors, and through their misuse by bad actors to create propaganda, spread

misinformation, and deduce sensitive information.

2. Large scale AI models must be subject to urgent regulatory scrutiny, particularly

given the frenzied speed of rollout to the public. Documentation and scrutiny of data

and related design choices at the stage of model development is key to surfacing and

mitigating harm.

It’s not a blank slate. Legislative proposals on Algorithmic Accountability must be

expanded and strengthened and existing legal tools should be creatively applied to

introduce friction and shape the direction of innovation.

There is growing exceptionalism around generative AI models that underplays

inherent risks and justifies their exclusion from the purview of AI regulation. We

should draw lessons from the ongoing debate in Europe on the inclusion of General

Purpose AI under the “high risk” category of the upcoming AI Act.

Along with breathless hype around the future potential of AI, the release of chatGPT (and its

subsequent adaptation into Microsoft’s search chatbot) immediately surfaced thorny legal questions,

such as, who owns and has rights over the content generated by these systems?

50

Is generative AI

protected from lawsuits relating to illegal content they might generate under intermediary liability

protections like Section 230?

51

What’s clear is that there are already existing legal regimes that apply to large language models, and we

aren’t building them from the ground up. In fact, rhetoric that implies this is necessary works mostly to

industry’s best interests, by slowing the paths to enforcement and updates to the law.

51

Electronic Frontier Foundation, “Section 230”, Electronic Frontier Foundation, n.d., https://www.e.org/issues/cda230.

50

James Vincent, “The scary truth about AI copyright is that nobody knows what will happen next”, The Verge, November 15, 2022,

https://www.theverge.com/23444685/generative-ai-copyright-infringement-legal-fair-use-training-data

2023 Landscape

21

A blog post recently published by the FTC outlined several ways the Agency’s authorities already apply

to generative AI systems: if they’re used for fraud, cause substantial injury, or make false claims about

the system’s capabilities the FTC has cause to step in. There are many other domains where other legal

regimes are likely to apply: intellectual property law, anti-discrimination provisions, and cybersecurity

regulations are among them.

There’s also a forward looking question of what norms and responsibilities should apply to these

systems. The growing consensus around recognized harms from AI systems (particularly inaccuracies,

bias, and discrimination) has led to a flurry of policy movement over the last few years centering around

greater transparency and diligence around data and algorithmic design practices (See also: Algorithmic

Accountability). These emerging AI policy approaches will need to be strengthened to address the

particular challenges these models bring up, and the current public attention on AI is poised to

galvanize momentum where it’s been lacking.

In the EU, this question is not theoretical. It is at the heart of a hotly contested debate about whether

the original developers of so-called “general purpose AI” (GPAI) models should be subject to the

regulatory requirements of the upcoming AI Act.

52

Introduced by the European Commission in April

2021, the Commission’s original proposal (Article 52a) eectively exempted the developers of GPAI from

complying with the range of documentation and other accountability requirements in the law.

53

This

would therefore mean that GPAI that ostensibly had no predetermined use or context would not qualify

as ‘high risk’ – another provision (Article 28) confirmed this position, implying stating that developers of

GPAI would only become responsible for compliance if they significantly modified or adapted the AI

system for high-risk use. The European Council’s position took a dierent stance where original

providers of GPAI will be subject to certain requirements in the law, although working out the specifics

of what these would be delegated to the Commission. Recent reports suggest that the European

Parliament, too, is considering obligations specific to original GPAI providers.

As the inter-institutional negotiation in the EU has flip-flopped on this issue the debate seems to have

devolved into an unhelpful binary where either end users or original developers take on liability,

54

rather

than both having responsibilities of dierent kinds at dierent stages.

55

And a recently leaked unocial

US government position paper reportedly states that placing burdens on original developers of GPAI

could be “very burdensome, technically dicult and in some cases impossible.”

56

56

Luca Bertuzzi, “The US Unocial Position on Upcoming EU Artificial Intelligence Rules,” Euractiv, October 24, 2022,

https://www.euractiv.com/section/digital/news/the-us-unocial-position-on-upcoming-eu-artificial-intelligence-rules.

55

The Mozilla Foundation’s position paper on GPAI helpfully argues in favor of joint liability. See Maximilian Gahntz and Claire Pershan, “Artificial

Intelligence Act: How the EU Can Take on the Challenge Posed by General-Purpose AI Systems,” Mozilla Foundation, 2022,

https://assets.mofoprod.net/network/documents/AI-Act_Mozilla-GPAI-Brief_Kx1ktuk.pdf.

54

An article by Brookings Fellow Alex Engler, for example, argues that regulating downstream end users makes more sense because “good

algorithmic design for a GPAI model doesn’t guarantee safety and fairness in its many potential uses, and it cannot address whether any particular

downstream application should be developed in the first place.” See Alex Engler, “To Regulate General Purpose AI, Make the Model Move”, Tech Policy

Press, November 10, 2022, https://techpolicy.press/to-regulate-general-purpose-ai-make-the-model-move/; See also Alex Engler, “The EU’s

attempt to regulate general purpose AI is counterproductive”, Brookings, August 24, 2022,

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2022/08/24/the-eus-attempt-to-regulate-open-source-ai-is-counterproductive/

53

European Commission, “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial

Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and Amending Certain Union Legislative Acts,” April 21, 2021,

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52021PC0206.

52

Creative Commons, “As European Council Adopts AI Act Position, Questions Remain on GPAI”, Creative Commons, December 13, 2022,

https://creativecommons.org/2022/12/13/as-european-council-adopts-ai-act-position-questions-remain-on-gpai/; Corporate Europe Observatory,

“The Lobbying Ghost in the Machine: Big Tech’s covert defanging of Europe’s AI Act”, February 2023, ‘

https://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/2023-02/The%20Lobbying%20Ghost%20in%20the%20Machine.pdf; Gian Volpicelli, ‘ChatGPT broke

the EU plan to regulate AI’, Politico, March 3, https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-plan-regulate-chatgpt-openai-artificial-intelligence-act/

2023 Landscape

22

These accounts lose sight of the two most important reasons that large-scale AI models require

oversight:

1. Data and design decisions made at the developer stage determine many of the model’s most

harmful downstream impacts, including the risks of bias and discrimination.

57

There is mounting

research and advocacy that argues for the benefits of rigorous documentation and

accountability requirements on the developers of large-scale models.

58

2. The developers of these models, many of which are Big Tech or Big Tech-funded, commercially

benefit from these models through licensing deals with downstream actors.

59

Companies

licensing these models for specific uses should certainly be accountable for conducting

diligence within the specific context in which these models are applied, but to make them

wholly liable for risks that emanate from data and design choices made at the stage of original

development would result in both unfair and ineective regulatory outcomes.

59

See for example Madhumita Murgia, “Big Tech companies use cloud computing arms to pursue alliances with AI groups”, Financial Times, February

5, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/5b17d011-8e0b-4ba1-bdca-4fbfdba10363?shareType=nongift; Leah Nylen and Dina Bass, “Microsoft

Threatens Data Restrictions In Rival AI Search”, Bloomberg, March 25, 2023,

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-25/microsoft-threatens-to-restrict-bing-data-from-rival-ai-search-tools; OpenAI, Pricing,

https://openai.com/api/pricing; Jonathan Vanian, “Microsoft adds OpenAI technology to Word and Excel”, CNBC, March 16, 2023,

https://www.cnbc.com/2023/03/16/microsoft-to-improve-oce-365-with-chatgpt-like-generative-ai-tech-.html; and Patrick Seitz, “Microsoft

Stock Breaks Out After Software Giant Adds AI To Oce Apps”, Investor’s Business Daily, March 17, 2023,

https://www.investors.com/news/technology/microsoft-stock-fueled-by-artificial-intelligence-in-oce-apps/.

58

See Timnit Gebru, Jamie Morgenstern, Briana Vecchione, Jennifer Wortman Vaughan, Hanna Wallach, Hal Daumé III, and Kate Crawford,

“Datasheets for Datasets,” arXiv:1803.09010, December 2021, ; Mehtab Khan and Alex Hanna, “The Subjects and Stages of AI Dataset Development:

A Framework for Dataset Accountability,” Ohio State Technology Law Journal, forthcoming, accessed March 3, 2023, ; and Bender, Gebru,

McMillan-Major, and Shmitchell, “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots.”

57

Sasha Costanza-Chock, Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. Cambridge: MIT Press.

2023 Landscape

23

Toxic Competition

Regulating Big Tech’s Data

Advantage

One of the key sources of tech firms' power is their data

advantage. Privacy and competition law are two tools that, used

in concert, can eectively curb this source of some of tech

firms' most harmful behavior. Doing so requires strategic

calibration of the eects of each on digital markets and on the

broader public, implementing a policy approach that takes in to

account the benefits firms seek to take advantage of via

information asymmetries.

In this section we identify two domains in which these

dynamics are currently playing out: data mergers and adtech.

These provide an illustrative example for analysis of the tech

industry playbook and a path forward.

2023 Landscape

24

Privacy and competition law are too often siloed from one another, leading to

interventions that easily compromise the objectives of one issue over the other. Firms

are taking advantage of this to amass information asymmetries that contribute to

further concentration of their power. Rather than accept the silos of legal expertise and

precedent, it’s clear that privacy and competition regulators need to work in concert to

regulate an industry that draws on invasive surveillance for competitive benefit.

60

Considered in isolation, traditional antitrust and privacy analyses could indeed lead in divergent

directions. But, as Maurice Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi underscore in their work, competition can be toxic.

61

As Stucke puts it, “in the digital platform economy, behavioral advertising can skew the platforms’, apps,

and websites’ incentives. The ensuing competition is about us, not for us. Here firms compete to exploit

us in discovering better ways to addict us, degrade our privacy, manipulate our behavior, and capture

the surplus.”

62

Scholars in the EU have taken this line of thinking as far as to explore how competition

law could be enforced as a substitute for data protection law given the endemic nature of such

practices within digital markets.

63

And though privacy measures that aim to curb data collection are in

some instances a significant step toward curbing tech firms’ data advantage, they only go so far —for

example, some proposals that focus on third-party tracking in isolation oer a giant loophole that

enables tech firms to entrench their power.

64

Bringing privacy and competition policy into closer consideration can, at best, oer a complementary

set of levers for tech accountability that work in concert with one another to check the power of big

tech firms.

65

If left unattended, pursuing privacy and competition in isolation will enable corporate

actors to “resolve” critiques through self-regulatory moves that ultimately expand and entrench, rather

than limit, concentrated tech power.

66

We see this playing out in two domains in particular: data mergers and adtech.

66

See Cudos, “The Fable of Self-Regulation: Big Tech and the End of Transparency,” n.d.,

https://www.cudos.org/blog/the-fable-of-self-regulation-big-tech-and-the-end-of-transparency-%F0%9F%8C%AB%EF%B8%8F; and Rys Farthing

and Dhakshayini Sooriyakumaran, “Why the Era of Big Tech Self-Regulation Must End,” Australian Quarterly 92 no. 4 (October–December 2021): 3–10,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27060078.

65

Peter Swire, “Protecting Consumers: Privacy Matters in Antitrust Analysis,” Center for American Progress, October 19, 2007,

https://www.americanprogress.org/article/protecting-consumers-privacy-matters-in-antitrust-analysis.

64

Maurice E. Stucke, “The Relationship between Privacy and Antitrust,” Notre Dame Law Review Reflection 97, no. 5 (2022): 400–417,

https://ndlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Stucke_97-Notre-Dame-L.-Rev.-Reflection-400-C.pdf

63

Giuseppe Colangelo and Mariateresa Maggiolino “Data Protection in Attention Markets: Protecting Privacy Through Competition?”, Journal of

European Competition Law & Practice, April 3, 2017, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2945085

62

Maurice E. Stucke, “The Relationship between Privacy and Antitrust,” Notre Dame Law Review Reflection 97, no. 5 (2022): 400–417,

https://ndlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Stucke_97-Notre-Dame-L.-Rev.-Reflection-400-C.pdf

61

Maurice E. Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi, Competition Overdose: How Free Market Mythology Transformed Us from Citizen Kings to Market Servants

(New York: HarperCollins, 2020)

60

Jacques Crémer, Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye and Heike Schweitzer, “Competition policy for the digital era”, European Commission, 2019,

https://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/reports/kd0419345enn.pdf; Autorité de la concurrence and Bundeskartellamt, “Competition Law and

Data”, Bundeskartellamt, May 10, 2016,

https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Publikation/DE/Berichte/Big%20Data%20Papier.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2; Competition &

Markets Authority and the Information Commissioner’s Oce, “Competition and Data Protection in Digital Markets: A Joint Statement between the

CMA and the ICO,” May 19, 2021,