DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES

IZA DP No. 15304

María Padilla-Romo

Cecilia Peluffo

Mariana Viollaz

Parents’ Effective Time Endowment and

Divorce:

Evidence from Extended School Days

MAY 2022

Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may

include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA

Guiding Principles of Research Integrity.

The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics

and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the

world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our

time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society.

IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper

should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author.

Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9

53113 Bonn, Germany

Phone: +49-228-3894-0

Email: [email protected] www.iza.org

IZA – Institute of Labor Economics

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES

ISSN: 2365-9793

IZA DP No. 15304

Parents’ Effective Time Endowment and

Divorce:

Evidence from Extended School Days

MAY 2022

María Padilla-Romo

University of Tennessee

Cecilia Peluffo

University of Florida

Mariana Viollaz

CEDLAS, IIE-FCE, Universidad Nacional de La Plata and IZA

ABSTRACT

IZA DP No. 15304 MAY 2022

Parents’ Effective Time Endowment and

Divorce:

Evidence from Extended School Days

*

Policies that extend the school day in elementary school provide an implicit childcare

subsidy for families. As such, they can affect parents’ time allocation and family dynamics.

This paper examines how extending the school day affects families by focusing on

marriage dissolution. We exploit the staggered adoption of a policy that extended the

availability of full-time elementary schools across different municipalities in Mexico. Using

administrative data on divorces, we find that the extension in the school day by 3.5 hours

leads to a significant increase in divorce rates. Moreover, the effect grows with every year

of municipalities’ exposure to full-time schooling. Increased female employment due to the

availability of childcare is likely to be one of the mechanisms that relaxed restrictions to

marriage dissolution.

JEL Classification: J12, J13, J18

Keywords: divorce, childcare, full-time schools

Corresponding author:

Mariana Viollaz

CEDLAS-FCE-UNLP

Calle 6 Nº 777 e/47 y 48

3º Piso

Of. 312

CP(1900) La Plata

Buenos Aires

Argentina

E-mail: [email protected]

* We thank Germán Bet, Celeste Carruthers, Seema Jayachandran, Jason Lindo, David Sappington, and Marianne

Wanamaker for helpful comments and suggestions. Any remaining errors are our own.

1 Introduction

Childcare availability a↵ects families’ time allocation and family members’ opport u n i t i es to

conduct activities outside their households. Limited access to childcare coupled with gender

norms limiting female labor force participation restricts women’s opportunity to allocate their

time to market activities. Because the opportunity to earn income tends to be correlated

with intra-household bargainin g power, this situation directly a↵ects families’ dynamics.

This paper sheds light on the connection between childcare availability and divorce, an

important and unexplored issue given that ear l y family environments are strong predictors

of short and long-run students’ outcomes (Heckman, 2006). Specificall y, we ex a mi n e how

extending the school day by 3.5 hours in public elementary schools in Mexico a↵ects divorce.

In doing so, we provide the first evidence on the e↵ects of access to full-time schools (FTS

hereafter) on marriage dissolut i o n and, to our knowledge, the first causal evidence regarding

the impact of the avail a bi l i ty of subsi d i zed childcare on divorce.

FTS a↵ect families’ decisions due to the implicit childcare subsi d y they provide. A di-

mension in which FTS can a↵ect famil i es is their e↵ect on family structure, speci fi cal ly

through marriage dissolution . Most of the literature on FTS has focused on examining th e

e↵ect of extensions in the school day on students’ learning, finding mixed results.

1

Recent

studies have found tha t the avai l a b i l i ty of FTS has signifi ca nt intra-household e↵ects, in-

creasing the labor force partici p at i o n of mothers and extended family members (Contreras

and Sep´ulveda, 2017; Padilla-Romo and Cabrera-Hern´andez, 2019; Cabrera-Hern´andez and

Padilla-Romo, 2020; Kozhaya and Mart´ınez Flores, 2020).

2

However, litt l e is known about

how the increase in the availability of FTS a↵ects other dimensions of household dynamics.

Considering a simple two-good model of labor supply decisio n s in which caregivers choose

1

See, for example, Cerdan -In fantes and Vermeersch (2007), Bellei (2009), Arzola Gonz´alez (2010), Pires

and Urzua (2010), Dias Mendes (2011), Xerxenevsky (2012), Llamb´ı (2013), Orkin (2013), Almeida et al.

(2016), Hincapie (2016), Cabrera-Hern´andez (2020), Ag¨uero et al. (2021), and Padilla-Romo (2022). For a

discussion on the e↵ects for Latin American and Caribbean countries, see Holland et al. (2015).

2

Other important outcomes that have been studied are teenage pregnancy (Kruger and Berthelon, 2009)

and child labor (Kozhaya and Mar t´ınez Flor es , 2020).

1

between home time (that includes time spent caring for children) and consumpt i o n goods,

extensions in the school day provide school-age children’s main caregivers with a higher

e↵ective time endowment, by freeing time that was previously spent providing child care.

3

Given that children’s main caregivers tend to be mothers or other female family members,

this allows for a highe r female labor force participation.

4

As intra-household bargaining

models suggest, the position of women in bargaining can inc re ase if the level of utili ty they

can independently achieve increases. In this case, women’s outside option can increase either

because of a hi gh e r female individual income (for women who increase their labor suppl y )

or due to the potential of increasing their income (for those women who do not adjust their

labor supply but can do so beca u se o f th ei r ex p an d e d ti m e endowment).

5

From a theoretical perspective, the direction of the expected e↵ect of changes in barg a i n -

ing power and female economic indepe n d en ce that may result from the extension in FTS

on marriage stability is inconclusive. In line with the independence e↵ect hypothesis (Ross

et al., 1975), divorce can increase due to the potential increase in independent sources of

income for women.

6

Moreover, female employment may lead to within househol d conflict or

higher intimate partner violence (Eswaran and Malhotra, 2011; Heath, 2014; Krishnan et al. ,

3

The simplifying assumption is that the consumption good s bundle doe s not inclu de childcare services

due (for example) to lack of availability. Supp os e we as su me that alternative paid sources of childcare are

available. In that case, the school day extension can be interpreted as in line with a model in which the

price of childcare services (included in the consumption bundle) declines.

4

For the particular case of the FTS program implemented in Mexico, there is evidence that this pol-

icy significantly increased female employment (Padilla-Romo and Cabrera-Hern´andez, 2019; Kozhaya and

Mart´ınez Flores, 2020; Cabrera-Hern´andez and Padilla-Romo, 2020). The connection between childcare and

female labor forc e participation (in countries di↵erent from Mexico) has been studied by Gelbach (2002),

Berlinski and Galiani (2007), Lefebvre and Merrigan (2008), Goux and Maurin (2010), Bauernschust e r an d

Schlotter (2015), Nollenberge r and Rodriguez-Planas (2015), Carta and Rizzica (2018), Eckho↵ Andresen

and Havnes (2019), and Berthelon et al. (2022), amon g others.

5

Increases in labor force p ar t ic i pat i on (and improvements in the type of emp l oyment) have been iden-

tified as positively associated with women’s bargaining power (Anderson and Eswaran, 2009; Heath and

Jayachandran, 2018). Importantly, increasing women’s labor force participation is not a necessary condition

for hi gh er bargai n i ng power. For examp le , Majlesi (2016) shows that higher employment opportunities for

women in Mexico lead to inc r ease s in women’s bargaining power .

6

In the same direction, Becker (1981) explains that the gain s from marriage are reduced, and divorce

becomes more attractive when the re is an incre ase in fe mal e earn i ngs . An important related dimension that

may a↵ect marriage dissol u ti on is the relat i ve earnings of the spouses. In their analysis for the United States,

Bertrand et al. (2015) find that marriages in which the husband earns less than t h e wife are more likely to

get a divorce. Using variation in manufacturing plant openings in Mexico, Estefan D´avila (2018) shows that

a reducti on in the male-female earnings inequality increases divorce rates.

2

2010; Luke and Munshi, 2011; Guarnieri and Rainer, 2018)whicharelikelytoa↵ect divorce

rates.

7

Yet, the increase in labor force participati on of women can lead to lower economic

stress for th e family and r ed u c e marital conflict, or to lower intimate partner violence due

to a reduction in exposure to the abusive partner (Chin, 2012).

8

Moreover, if childcare has

adeterrencee↵ect on divorce due to the burden it imposes on the parent receiving custody

of children (Ch er li n, 1977), the implicit reduction in childcare costs originated by this policy

can a↵ect divorce rates directly.

9

Given the comp lex i ty of the mechanisms i n place and the

lack of con sen su s on their expected e↵ect on divorce, empirical evidence is crucial to shed

light on the potential e↵ects of access to subsidized childcare on d i vorce. In this paper, we fill

this gap in the literatur e by studying a policy that provides a large impli ci t childcar e subsidy

by extending the school day from 4.5 to 8 hours for students enrolle d in public elementary

schools in Mexico.

Our empirical approach relies on leveraging plau si b l y exogenous variation from a large-

scale expansion in FTS across Mexican municipalities from 2007 to 2016. To id e ntify the

dynamic e↵ects of the extension in the school day on divorce rates over time, we combine

administrative records from all divorces in Mexico with annual school-level census data

on enrollment and participa ti o n in the FTS progra m . Our estimates are obtained using

the estimation method for intertemporal treatment e↵ects proposed by de Chaisemart i n

and D’Haultfœuill e (2020) which prod u ces estimates that are robust to heterogeneous and

dynamic treatment e↵ects across municipalities and years. We find that, as a result of

an average increase in FTS availability of 24 percentage points, the divorce rate incr ea sed

by 0.046 di vorces per 1,000 individuals (a 15% increment relative to divorces in treated

municipalitie s in the year prior to the openin g of the first FTS). The e↵ect rises over time,

reaching an increase of 0.105 in the divorce rate after the municipalities provided extended

7

Domestic violence can also be a↵ected by the gender wage gap. For the United States, Aizer ( 2010)

finds that declines in the gender wage gap lead to the reduction of violence against women.

8

See He at h and Jayachandran (2018) for an excellent discussion of the literature on female labor force

participation in developing countries, its causes, and consequences.

9

Cherlin (1977)describesthise↵ect for families with children in prescho ol in the United States.

3

school days for seven years (when the expansion i n FT S re ached 32 percentage points).

To assess the validity o f the estimated e↵ects on divorce rates, we estimate placebo e↵ects

by com p a r i n g the evolution of divorce rates in municipalities not exposed to the FTS pro g ra m

and municipalities implementing this program before the roll-out took place. We find that

the outcome variables for these two groups of municipalities evolved in a parallel way prior

to the program’s implementation, which supports our identification strategy. We also show

that our results are robust to using the interaction-weighted estimator developed by Sun and

Abraham (2021)andtheimputationestimatorproposedbyBorusyak et al. (2021). Finally,

we show that our estimates are robust to controlling for the state-level implementation of

unilateral divorce laws, which allow fo r non-fault un i l a t er a l divorce and have been shown to

increase divorce rates i n Mex i co (Ag u i rr e, 2019; Hoehn-Velasco and Penglase, 2021).

The ext en si o n in the avail a b i l i ty of childcare does not a ↵ect divorce homogeneously acr oss

areas. The increased number of hours elementary school students spend in school leads

to a more pronounced rise in divorce rates in areas with higher initial divorce rates and

higher baseline fema l e employment. These results suggest t h a t women’s increased bargaining

power is likely to result in marriage dissolution in areas where social norms were initially

more favor a b l e to divorce and women’s economic independence. Con si st ent with t h e short-

term labor supply responses to FTS in Mexico do cu m ented in Padilla-Romo and Cabrera-

Hern´andez (2019), we find that childcare availability through extended school days leads

to a rise in female employment in the longer run. This finding indicates that the higher

e↵ective ti me endowment women get due to the introducti on of full-time schooling is used

in the labor market, resulting in hi g h er fem a l e econ o m i c in d ependence.

We contribute to several strands of th e literature. We add to the literature on female eco-

nomic independence and divorce, which in cl u d es studies examining the connection between

female non-labor income, labor income, and potential earnings and marriage st ab i l i ty (Ross

et al., 1975; Becker et al., 1977; Ho↵man and Duncan, 1995; Weiss and Willis, 1997; Jalovaara,

2003; Bobonis, 2011; Ha n ki n s and Hoekstra, 2011; Bergolo and Galv´an, 2018; Berniell et al.,

4

2020). We also contribute to the literature on the intra-household e↵ects of (public) full-

time schools (Contreras and Sep´ulved a, 2017; Padilla-Romo and Cabrera-Hern´andez, 2019;

Kozhaya and Mart´ınez Flores, 2020; Cab r er a -Her n ´andez and Padilla-Romo, 2020; Berthelon

et al., 2022) and, more generally, to the literature on the conn ect i o n between public ex-

penditure and family outcomes (Dickert-Conlin, 1999; Halla et al., 2016; Dahl et al., 2016;

Bastian, 2017).

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the institutional features related to

divorce in Mexico and the FTS progra m we study. Section 3 presents the data. Section

4 discusses the identification strategy. Section 5 presents the estimated results. Section 6

examines the robustness of our estimates and Sect i on 7 concludes.

2 Background

The FTS pr o gr a m expan s i on tha t we analyze extended the school day for students enrolled

in public Mexica n elementary schools from 4.5 to 8 hours. This federally funded program was

launched sta r t i n g in the 2007-2008 academic year, and it was aimed at improving education

quality by expanding learning opportunities through an extended school schedule. Each state

assigned schools to this program following broad guidelines established by the Secretariat of

Public Education. These guidelines include the requ i r em ent that the schools operate only

in one shift and provide serv i ces for vulnerable students.

10

The FTS program represents one

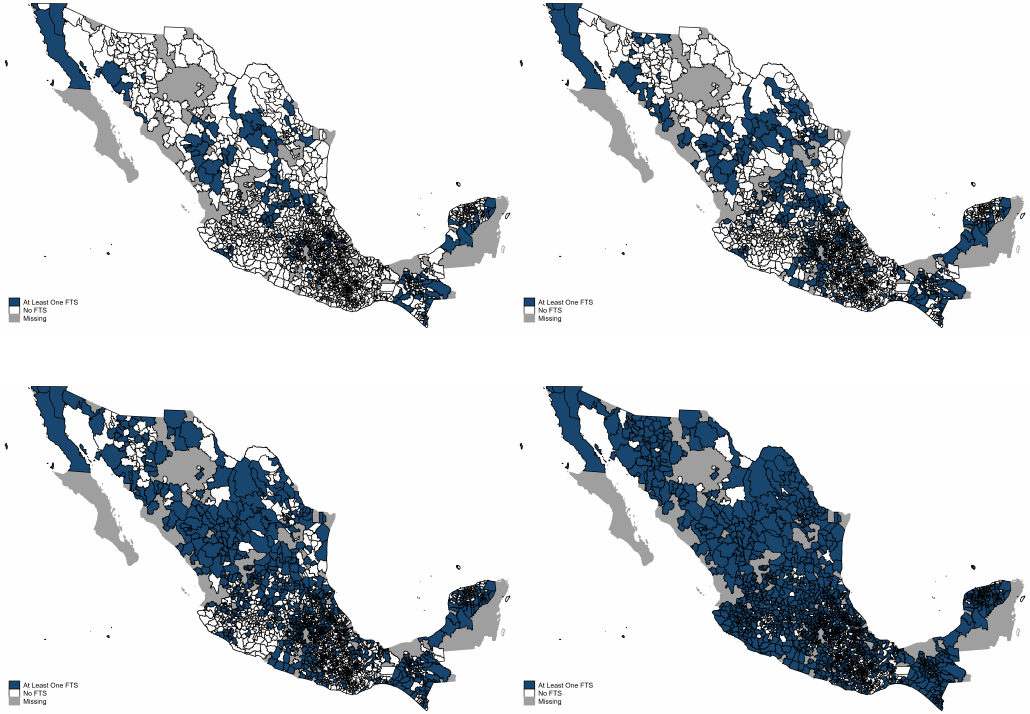

of the largest investments in education i n the past decad es in Mexico. In Figure 1, we show

the timing of implementation, considering the first year in which the first school in each

municipality was incorporated in the FTS program. In 2007, the pr og r am only covered 500

schools. Over time, the coverage increased , reaching m or e tha n 25 % of pu bl i c elem e ntary

schools in more than 80% of th e municipalities in Mexico.

The extension in the length of school days may a↵ect marriage stability by impacting

10

See Padilla-Romo and Cabrera-Hern´andez (2019), Cabrera-Hern´andez (2020), Cabrera-Hern´andez and

Padilla-Romo (2020), and Padilla-Romo (2022) for a detailed description of the program.

5

female employment. How fem a l e labor market decisions and women’s independence more

generally evolve depends on the gender norms prevailing in society. Social norms a↵ect female

labor mar ket participation because of their influence in the intra-household distribution

of time spent in childcare (Jayachandran, 2021). Like many developing countries, Mexico

exhibits signi ficant gender di↵erences in the prevalence of unpaid work. By 2019, women

spent 67% of their time carrying out unpaid work while men allocated 28% of their s. Looki n g

specifically at gender di↵erences in the time allocated to domestic work, women spent (on

average) 30.8 hours per week, and men spent 11. 6 hours in the same acti v i t i es. When

focusing on the care of children, women spent 24.1 hours per week and men spent 11.5 per

week taking care of children aged 14 years or younger.

11

The absence of a↵ordable and high-

quality formal childcare options can exacerbate this issue since it often results in relying on

care by mothers and other female family members (Padilla-Romo and Cabrera-Hern´andez,

2019; Cabrera-Hern´an d ez a n d Padilla-Romo, 2020; Talamas, 2020).

Gender nor m s in terms of care are al so reflected in individuals’ views about female labor

force partici p at i o n . According to the World Values Survey 2017-2020 (Haerpfe r et al., 2020),

31.5% (21.4%) of individuals in Mexico agree (strongly agree) with the statement “When

a mother works for pay, the children su↵er.” To put this inform a t i o n in context, the level

of agreement (strong agreement) in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K. is 17.4%, 16.6%, and

19.9% (3.3%, 4.4%, and 3.4%) respectively. In terms of intra-household dynamics, 28.8%

(24.2%) of individuals in Mexico agree (strongly agree) with the statement indicating “If a

woman earns more money than her husband, it’s almost certain to cause problems. ” In the

case of t h e United States, only 10% (0%) of agreement (stro n g agreement) with the same

statement is reported. To examine how prevalent soc i al norms interact with the impact on

divorce, in Section 5.3, we separately examine how access to FTS a↵ected divorces in areas

with di↵erent degrees of baseline female employment.

Before the implementation of the FTS progr a m , elementary schoo l days of 4.5 hours

11

Data from the 2019 Mexican Time Use S ur vey.

6

imposed additional constraints to the possibility that primary caregivers participate in the

labor market. While in Mexico, women’s labor force participation remains relat i vely low,

it has increased as a response to childcar e subsidies (Padilla-Romo and Cabrera-Hern´andez,

2019; Calderon, 2014).

12

Given the relevan ce of t h e wi t h in household income distribution

as a potential source of conflict, in Section 5.3, we analyze how th e reform a↵ected female

employment in the long run.

Considering divorce regulation, Mexic o h a s l e ga l i zed divorce relatively earlier than other

Latin American countries, allowing for mutual consent divorce and divorce with a cause in

1917 (Brazil, Argentina, and Chile legalized divorce in 1977, 1987, and 2004, respect i vely).

Over time, the country implemented reform s that extended the possible causes for divorce

and allowed for non-fault unilateral divorce.

13

In Section 6, we show that our estima t es are

robust to control for the state-level implementation of unilateral divorce laws.

3Data

Data on divorce filings come from th e National Institute of Statistics and Geography (IN-

EGI). These administ r at i ve data contain individual divorce records and cover all divorces in

Mexico. We calculate divorce rates per 1,000 people using municipality-level popu l at i on pro-

jections from the National Population Council (CONAPO) for each academi c year (August

to July) and municipality.

To measure access to FTS , we rely on school-level census data on enrollment and partic-

ipation in the FTS program from the Secretariat of Publ i c Education. For each academic

year, we match the availability of FTS in each municipality with information on the munic-

ipality of residence of the divorcing wife to capture exposure to the extension in the school

day.

14

To examine long-run e↵ ect s on female econ om ic independence, we combine ad m i n is-

12

By 2016, only 43.92% of women older than 15 were economically active in Mexico (ILO S TAT).

13

For the case of Mexico, Aguirre (2019) and Hoehn-Velasco and Penglase (2021) describe the legal changes

over time and analyze the e↵e ct of unilateral divorce laws on divorce.

14

Information on the municipality in which marriages took place is also available. Given that the average

7

trative records on enrollment and school participation in the FTS prog ra m with census data

on female employment from IPUMS-International for years 2000, 2010, and 2015 for women

aged 15-65.

We restrict our sampl e to municipalities that h ave existed and maintained their geo-

graphic boundaries from 2000 to 2016. We also drop from the analysis municipalities that

experienced the first FTS expansion in the 2007/2008 academic year because many of the

500 school s that adopted the program were already full-time before 2007.

15

Table 1 shows

descriptive statistics for municipali t i es that by 2016 had implemented the FTS program

(Ever Treated)andmunicipalitiesthathadnotimplementedtheprogram(Never Treated).

Ever-treated municipalities had higher divorce rates than never-treated municipalities prior

to the roll-out of the FTS program. On average 58.3% of the municipalities that implemented

the FTS program by 2016 had pre-intervention divorce rat es above th e cross-municipalities

median. The percentage of women employed in 2000 is not significantly di↵erent between

ever-treated and never-treated municipalities. Still, the percentage of municipalities with

high female employment in 2000 (above the cross-municipalities median) is larg er among

the ever-treated. Ever-treated municipalities had (on average) more population than never

treated municipalities. Moreover, they ar e more likely to be located i n a state that allows

for unilateral divorce by 2016.

4 Identification Strategy

To identify the e↵ects of FTS on divorce, we exploit municipality-level variati o n in the

availabil i ty of elementary FTS. We e st i m at e th e fol l owing fixe d e↵ects model:

length of marriages in our sample is 13 years (with a median of 11 years), the municipality of residence is

likely t o provide a more accurate measure of e x posur e to the program than the municipality of marriage .

We provide evidence on the absence of endogenous migratory respon ses to t h e p rogr am in t h e popu l at ion of

individuals filing for divorce in Section 6.

15

After imposing these restrictions, our analytical sample includes 2, 178 out of the 2,456 existing munici-

palities in 2016.

8

DR

mt

= ↵

m

+

t

+

7

X

k=0

k

FTS

m,tk

+

m

t + u

mt

(1)

where DR

mt

is the divorce rate in municipality m in academic year t, ↵

m

are municipality

fixed e↵ects,

t

are academic year fixed e↵ects, and u

mt

is an error term that we allow to

be correlated wit h i n municipalit i es. Our variable of interest, FTS

m,tk

is an indicator equal

to one k years after the municipality open ed its first FTS, and zero otherwise. To allow for

the possibility of di↵erential divorce trends across municipalities, we include municipality-

specific linear time-trends as controls (

m

t). The coefficients

k

identify the avera g e e↵ect of

k + 1 years of imple m entation of the FTS program on municip a l i ti e s’ d i vorce rates.

Our empirical approach exploits the staggered adoption of the FTS program across munic-

ipalities. Estimation of Equation 1 using two-way-fixed-e↵ects (TWFE) under ordinary least

squares (OL S ) including leads and lags of the implementation of the FTS pol i cy produces

estimates that are not robust to heterogeneous an d dynamic e↵ects over time and across

groups (Goodman-Bacon, 2021; Sun, 2021; de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœui l l e, 2020). To

overcome this concern, we estimate the regression in Equation 1 foll owing the methodology

developed by de Chaisemartin and D’Hau l t fœu i l l e (2020). This method produces estimates

that are robust to heterogeneous and dynamic treatment e↵ects acro ss municipaliti es and

years under standard common-trends assump t i o n s. The estimates are computed by com-

paring the t k 1tot evolution of divorce rates in municipalities implementing the FTS

program for the first time in tk and municipalities that have not implemented the program

yet in period t.

16

Before presenting our m a i n r es u l ts , and to put our m ai n estimates in context, we examine

how the availability of FTS in a municip al i ty evolves over time once th e municipality s ta r t s

implementing the program. To do so, we follow Padilla-Romo and Cabrera-Hern´andez (2019)

and define ou r outcome variable as th e predicted capacity of FTS in municipali ty m and

16

Weighted averages of those di↵erence-in-di↵erences estimators across years are unbiased estimators for

the average e↵ect of having changed treatment for the first time k periods ago (de Chai se mar t i n and

D’Haultfœuille, 2020).

9

academic year t using Equation 2:

FTS

mt

=

P

s2m

¯e

s

FT

st

P

s2m

¯e

s

(2)

where ¯e

s

is the average enrol l m ent at school s fr om 2001 to 2006 (prior to program imple-

mentation) and FT

st

is equal to one if elementary school s participates in the FTS p r o gr am

at academic year t and zero otherwise.

5 Results

5.1 Main Estimates

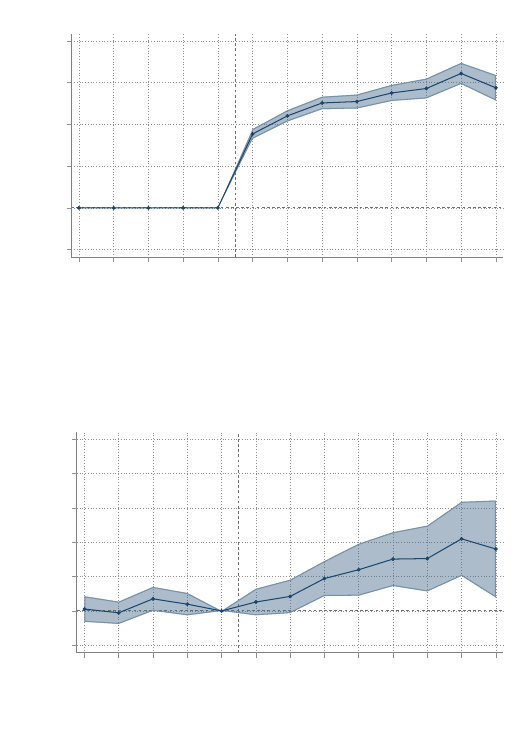

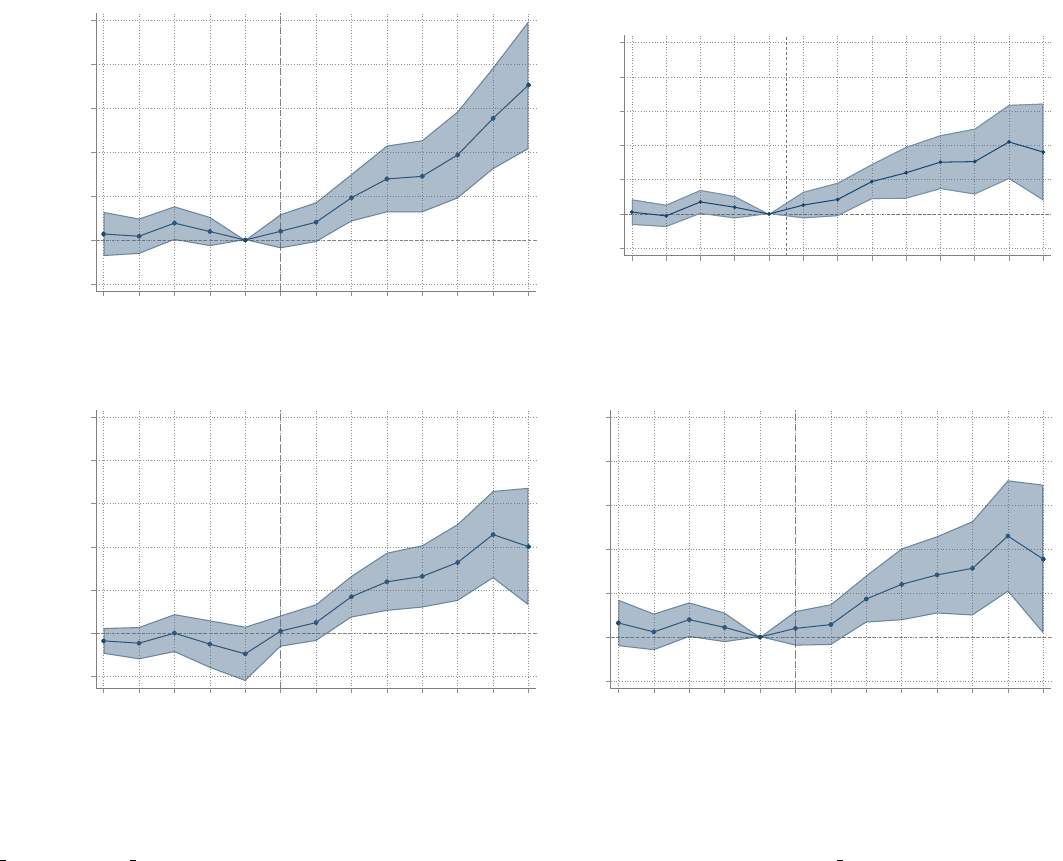

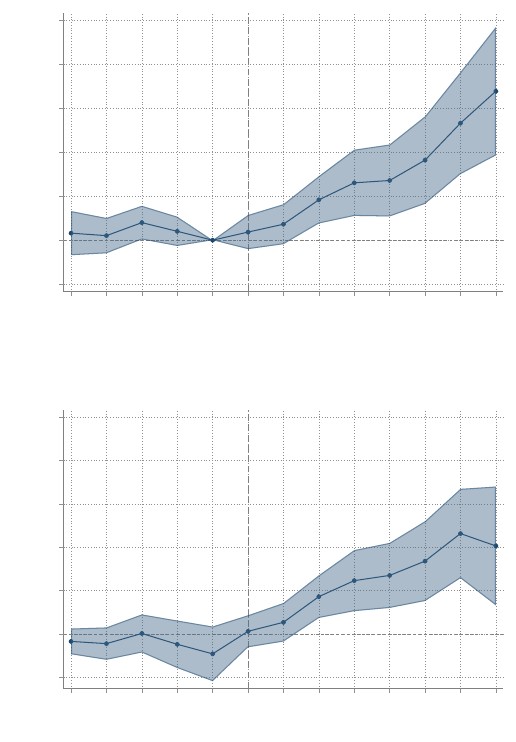

Panel (a) of Fi gu r e 2 presents the evolution of the predicted capacity of FTS in a municipal i ty

during the first year in which the first FTS was opened (k = 0) and for subsequent years

(k 2 [1, 7]). On average, during the first year in which a municipality implements the

program, the predicted FTS availability increases by 18 percentage points. The e↵ect reaches

its maximum of 32 percentage points six years after, when the municipality had implemented

the program for seven years.

Panel (b) of Figure 2 shows the estimated results of FTS on the aver a ge divorce rate .

In the first year of program implementation, the divorce rate is not a↵ected by the (first)

expansion of the FTS program relative to municipalitie s that did not implement it yet; th e

estimated e↵ect is close to zero and statistically insignificant. However, one year after (k =1)

the divorce rate significantly increases by 0.021 per 1,000 ind i v i d u als. The e↵ects on divorce

increase with every year of municipalities’ exposure to the FTS program. This increasing

e↵ect reflects a combination of increased length of exposure ( i n years since the first opening

of an FTS in a municipality) an d the expansion in the capacity that occurs over t i m e within

municipalitie s implementing this program, as shown in Panel (a). After the municipalities

have been providing extended school days for seven years and FTS avail a b i l i ty i n c re ase d (on

10

average) by 32 percentage points, this large expansion in the availability of implicit childcare

subsidies translates into an average incr eas e in the divorce rate of 0.105 divorces per 1,000

individuals.

To examine the validity of the underlying assumptions for identification, to the left of

zero, Figure 2 shows estimates of placebo e↵ects. In Panel (a), estimates of placebo e↵ects

are zero by construction because they measure the e↵ects on the predicted capacity of FTS

in a municipali ty before the program rollout. Considering the estimates of the e↵ects of the

extension in the school day on divorce, i n Panel (b), we fin d that placebo estimates are close

to zero and statistically insignificant, which provides support to our identification strategy

(we cannot reject the null hypothesis that all placebos are statistically insignificant).

17

5.2 Marriage Dissolution and the Role of Social Norms

Our main estimates show that the divorce rate significantly increases due to the availability

of implicit childcare subsidies. In this section, we analyze the extent to which lack of access

to free childcare constitutes a restriction on marriage dissolution in areas with di↵erent social

norms.

In particul ar, we examine how the e↵ects on divorce vary by pre-intervention divorce

rates (i.e., average divorce rates for 2000-2007), which we consider as a proxy for social norms

about divorce. We group municipalities above and below the cross-municipality median of

the divorce rate over 2000-2007. Table 2 shows that extensions in the school day did not

result in an increase in divorces in areas with low initia l divorce rates (point estimates are

close to zero and statistically insignificant). In contrast, in areas where divorces were more

common prior to the roll-out of the FTS p r og r am , the implicit childcare subsidy positively

and significantly a↵ects marriage dissolution. Our estimates suggest that while financial

constraints can impose sub stantial restrictions on divorce in municipalities where marriage

17

We estimate long-di↵erence placebos. While first-di↵erence placebo estimates test if common trends

hold over pairs of consecutive periods, long-di↵erence placebos test for the presenc e of common tr en ds

along several periods, where (if present) divergent trends in divorce rates are more likely to be detected

(de Chaise mar ti n and D’Haultfœuille, 2020).

11

dissolution is more accepta b l e to society, childcare subsidies are unlikely to a↵ect marria g e

stability in areas where social norms agains t di vorce are mor e p r evalent.

Aseconddimensionweanalyzeishowthee↵ects vary with the prevalence of pre-

interventi on female employment (measured with 2000 census data from IPUMS). Intuitively,

gender norms may a↵ect the participation of women in t h e labor market, makin g it difficult

for women to increase their labor supply on ce their e↵ect i ve ti m e endowment has i n cr eased

due to the availability of extended scho ol days. In Table 3, we estim a t e our ma i n regression

for the sub-samples of municipalities where female empl oyment was above and below the

cross-municipality median before the implementation of the imp l i ci t childcare subsidy. The

estimated results show that the overall increase in divorces is mainly explained by the avail-

ability of childcare in municipalities with higher baseline female employment. This indicates

that gender roles and their potential e↵ect on labor force partici p ation (and earnings) shape

how childcare subsidies a↵ect mar r i a g e di sso l u t i o n .

18

5.3 Childcare Availability and Female Economic Independence

Availability of childcare subsi d i es can translate into in cr ea sed bargaining power and economic

independence of women, who are typically the pri m a ry caregivers for children. Increased fe-

male labor supply can ease couples’ financial restrictions and facilitate divorce when partner s

cooperatively make decisions. Higher female labor force participation can also lead to di -

vorce du e to within househol d conflict. Impo r ta ntly, highe r divorce risk can also lead to an

increase in the l a bor force participation of women (Bargain et al., 2012). This implies that

increases in labor force particip a t i o n ca n act as a mechanism that faci l i ta t es d i vorce and as

aresponsetoincreasesintheriskofdivorceanddivorcerates.

Using h o u seh o l d survey data, previous stud i es have documented a short - ru n increase in

18

Even though baseline divorce and employment rates are likely to be related to how traditional social

norms are, th ey exhibit a weak positive correlati on in the data (the correlation coefficient between the

indicator var i abl es for being above the median of the baseline fe mal e employment rate and for bein g above

the median of the baseline divorce rate is 0.0657), which suggests they are capturing di↵erent dimensions

that shape how lack of childcare availability a↵ects divorce rates.

12

labor supply as a response to the extension in FTS availability in Mexico (Padilla-Romo and

Cabrera-Hern´an d ez, 2019; Cabrera-Hern´andez and Padilla-Romo, 2020). We complement

this literature by providing evidence on longer-term e↵ects on female employment relying

on census data. Focusing on the long-term also allows us to examine the impacts on fe-

male employment as an out co m e t h a t accompanies (and in some instances can med i a t e) the

estimated increase in divorce rates due to the extension in the school days.

We use census data on female employment for 2000, 2010, and 2015 from IPUMS. We

proceed by estimating TWFE models. In Tab l e 4, Co l u m n (1), we show that consist ent with

findings in other studies, longer school days lead to an increase in femal e employment (Contr-

eras an d Sep´ulveda, 2017; Padilla- Ro m o and Cabrera-Her n ´andez, 2019; Cabrera-Hern´and ez

and Padilla-Romo, 2020; Kozhaya and Mart´ınez Flores, 2020; Berthelon et al., 2022). Our

estimate indicates that the extension in t he scho ol day by 3.5 hours gen er ated a long-run

average increase of 1.8 percentage points in the share of employed women (6.8% relative to

the baseline in the ever-treated municipalities). However, th i s estimate masks substantial

heterogeneity across municipalities. The e↵ects are close to zero and statistically insignif-

icant when restricting the sam p l e to municipalities with low baseline female employment

rates (female employment rate below the cross-municipality median in 2000). In contrast,

in municipalities where women were more likely to be employed prior to the intervention

(female employment rate above the cross-municipality median in 2000), the e↵ects are large

and statistically significant, with an increase in female employment of 3.6 percentage points

(10.7% relative to the baseline).

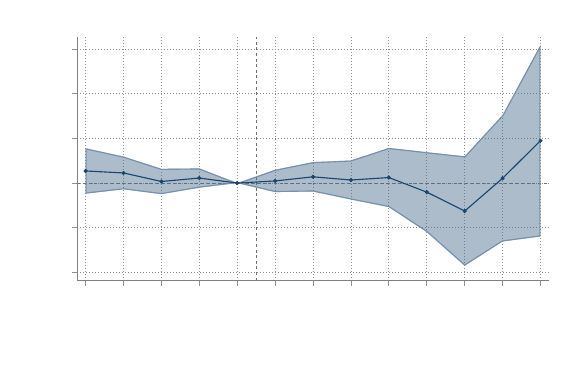

Goodman-Bacon (2021) shows that standard TWFE models recover a variance-weighted

average of all two-by-two comparisons in the data. In our setting, in which im p l em entation

of the FTS was staggered, this implies that municipalities in which the policy starts being

implemented in year t are compared with other municipalities that adopted this program

earlier, leading to potentially biased estimates. We eval uat e the severity of this concern

by implementing a decomposition suggested by Goodman-Bacon (2021). Figure 3 sh ows

13

the di↵erence-in-di↵erences (DD) esti mates for di↵erent comparison groups (ever t r ea t ed

vs. never treated, early treated vs. later treated, and later treated vs. early treated)

in the vertical axi s and the associated weights in th e horizontal axis. In Panel (a), we

report estimates for the overall sample. In Panels (b) and (c), we show estimates for the

sub-samples of municipalities wit h baseline female employment rates below and above the

median, respectively. The results of the decomposi t i on suggest that our main conclusions

remain valid. When comparing ever-treated and never-treated municipalities, we find an

e↵ect close to zero for municipalities w i th low initial female employment and positive and

large for the rest of the municipalities.

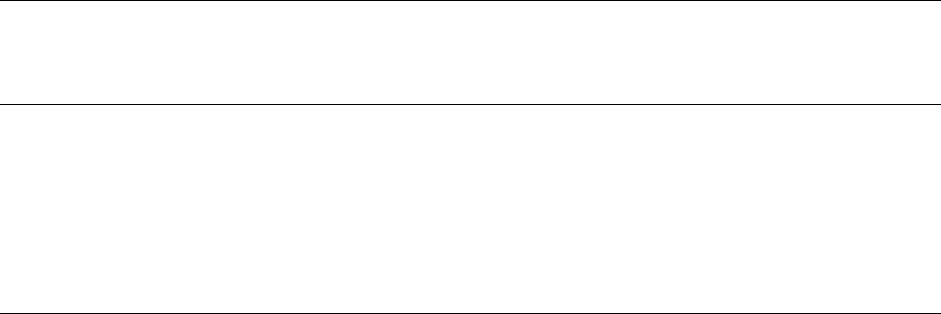

6 Robustness

Our main results rely on the estimatio n method proposed in de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuil l e

(2020), which is one of several estimators available to address issues related to staggered

treatments and heterogeneous e↵ects. However, each method relies on di↵erent sources of

variation and set of identifying assumptions. To examine th e robustness of our estimates

to alternative estimators, i n Panels (a) th r o u gh (d) of Figure 4, we compa r e the estimated

e↵ects of FTS availab i l i ty on divorce rates using de Ch a i sem a rt i n and D’Haultfœu i l l e (2020)

with other three estimatio n methods: the OLS-TWFE estimator, the interaction-weighted

estimator (Sun and Abraham, 2021), and the imputation estimator ( Borusyak et al., 2021).

Overall, the estimated e↵ects across all four methods increase with every year of exposure

to FTS wi t h point est i m a t es of between 0 . 1 05 and 0. 13 8 after seven years of implementation

of the extension in the school day. Moreover, in all cases, the estimates for the years prior

to treatment are close to zero and statistically insignificant, supporting the parallel trends

assumption.

Because Mexico implemented state-level reforms introdu cin g unilateral divorce laws, we

also examine the robustness of our results (that leverage municipality-level variation in the

14

extension of the FTS program) to controlling for state-level changes in divorce l aws. Becaus e

controlling for addition al treatments imposes empir ical challenges, we star t by stu d y in g

this issue relying on a traditi o n al fixed e↵ects model, which provides more flexibility in

terms of empirical implementation. In Panel (a) of Figure A.1, we show the estimated

e↵ects on divorce using a tradition al OLS fix ed -e↵ect s model adding an indicator for the

implementatio n of unilateral divorce laws as control.

19

A caveat for these resu l t s is that in

TWFE with multi p l e treatment i n d i cat o r s, the estimated coefficient in a particul ar treatment

(i.e., availability of FTS in our context) is contaminated by a weighted sum of the e↵ects of

the other treatments in each municipality and year (de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfoeui l l e,

2020). Considering this concern, in Panel (b), we control for the implementation of unilateral

divorce laws using the imputation estimator developed by Borusyak et al. (2021). The

estimated results on divorce rates are robust to using this altern at ive approach.

Finally, because the average duration of marriages in the sam p l e of divorcing individuals

is 13 years (with a median durat i o n of 11 years), we use the municipali ty of residence of

the wife to capture exposur e to the FTS program. A potential concern is that endogenous

migratory responses induced by the program may a↵ect our estimates. We examine the

extent to which FTS explain s the share of divorces in which the municipality of residence of

the wife di↵ers from the municipality of marriage in total divorces (in the municipality of

residence). In Figure 5 we show that FTS expansion is not corr el a te d with changes in this

share, indicating that endogenous mig r at i o n i s u n l ikely to bi a s ou r e st i m at es.

7 Conclusion

This study provides the first causal evidence on the e↵ects of implicit childcare subsidies,

through longer school days, on marriage dissolution. We find that the availa b i l i ty of FTS in

amunicipalityincreasesthedivorcerateper1,000peopleby0.021twoyearsafterthefirst

19

For most of the states, we rely on informati on from Garc´ıa-Ramos (2021) to identify the timing of the

introduction of these laws. In addition, we combine information from Hoehn-Velasco and Penglase (2021)

with information from alternative sources for the cases in wh i ch the date is mi s si ng in Garc´ıa-Ramos (2021).

15

FTS opened and that the e↵ect increases over time, reaching 0.105 divorces per 1,000 people

after seven years. Our main estimates su gg est that the ava i l a b i l i ty of FTS led to 23 , 3 14

additional divorces between 2009 and 2016, or approximately 5 percent of the total number

of divorces filed during this time frame.

20

Mothers and other female family members spend a disp r oportionate fraction of their time

caring for children. Longer school days provided them with an increase in their e↵ective time

endowment that resulted in improved opportunities to acquire individual income. As a result,

the intra-household barg a i n i n g p osi t i o n s are likely to b e mo d i fi ed . Our results sugges t that

these changes in bargaining power translated into h i gh er divorce rates in areas with social

norms more favorable to divorce and to female employment, where lack of access to childcare

was more likely to impose restrictions on marriage dissolution.

20

These numbers are calculated using the est im at ed e↵ects in Column 1 of Table 2.

16

References

Ag¨uero, J., Favara, M., Porter, C. , and S´anchez, A. (2021). Do More School Resourc es

Increase Learning Outcomes? Evidence from an Extended School-Day Reform.

Aguirre, E. (2019). Do Changes in Divorce Legislation Have an Impact on Divorce Rates?

The Case of Unilateral Divorce in Mexico. Latin American Economic Review, 28(1):1–24.

Aizer, A. (2010). The Gender Wage Gap and Domestic Viol en ce . American Economic

Review,100(4):1847–59.

Almeida, R., Bresol i n , A., Pugialli Da Silva Borges, B., Mendes, K., and Menezes-Filho,

N. A. (2016). Assessing the Impacts of Mais Educacao on Educational Ou t com e s: Evidence

between 2007 and 201 1 . World Bank Policy Research Working Paper,(7644).

Anderson, S. and Eswaran, M. (2009). What Determin es Female Autonomy? Evidence from

Bangladesh. Journal of Development Economics,90(2):179–191.

Arzola Go n z´alez, M. (20 10) . Impacto de la Jornada Escolar Completa en el Desempe˜no de los

Alumnos, Medido con la Evoluci´on en sus Pruebas SIMCE. Santiago: Pontificia Univer-

sidad Catolica de Chile. Obtenido de http://www. economia. puc. cl/docs/tesis mparzola.

pdf.

Bargain, O., Gonz´alez, L., Keane, C., and

¨

Ozcan, B. (2012). Female Labor Supply and

Divorce: New Evidence from Ireland. European Economic Review,56(8):1675–1691.

Bastian, J. (2017). Unintended Consequences? More Marriage, More Children, an d the

EITC. In Proceedings. Annual Conference on Taxation and Minutes of the Annual Meeting

of the National Tax Association, volume 110, pages 1–56.

Bauernschuster, S. and Schlotter, M. (2015). Public Child Care and Mothers’ Labor Sup-

ply—Evidence from Two Quasi-Experiments. Journal of Public Economics, 123(C):1–16.

17

Becker, G. (1981). A Treatise on the Family. National Bureau of Economic Res ear ch, Inc.

Becker, G. S., Landes, E. M., and Michael, R. T. (1977). An Economic Analysis of Marit al

Instability. Journal of Political Economy,85(6):1141–1187.

Bellei, C. (2009). Does Lengthening the School Day Increase Students’ Academic Achieve-

ment? Results from a Natural Experiment in Chile. Economics of Education Review,

28(5):629–640.

Bergolo, M. and Galv´an, E. (2018). Intra-household Behavioral Responses to Cash Trans-

fer Programs. Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design. World Development,

103:100–118.

Berlinski, S. and Galiani, S. (2007). The E↵ect of a Large Expansion of Pre-Primary

School Facilities on Preschool Attendance and Maternal Employment. Labour Economics,

14(3):665–680.

Berniell, I., de la Mata, D., and Pinto Machado, M. (2020) . The Impact of a Permanent

Income Shock on the Situation of Women in the Hou seh o l d : The Case of a Pension Reform

in Argentina. Economic Development and Cultural Change,68(4):1295–1343.

Berthelon, M., Kruger, D., an d Oyarz´un, M. (2022). School Schedules and Mothers’ Em-

ployment: Evidence from an Education Reform. Review of Economics of the Household,

pages 1–41.

Bertrand, M., Kamenica, E., and Pan, J. (2015). Gender Identity and Relative Income

within Households. The Quarterly Journal of Economics,130(2):571–614.

Bobonis, G. J. (2011). The Impact of Conditi on al Cash Tran sfe rs on Marriage and Divorce.

Economic Development and Cultural Change,59(2):281–312.

Borusyak, K., Jaravel, X., and Spiess, J. (2021). Revisiting Event Study Designs: Robust

and Efficient Estimation.

18

Cabrera-Hern´an d ez, F. (2 0 20 ) . Does Lengthening the School Day Increase Scho o l Value-

Added? Eviden c e from a Mid-Inco m e Country. The Journal of Development Studies,

56(2):314–335.

Cabrera-Hern´an d ez, F. and Padilla-Romo, M. (2020). Women as Caregivers: Full-Time

Schools and Gr an dm o t h er s’ Labor Sup p l y .

Calderon, G. (2014). The E↵ects of Ch i ld Care Provision in Mexico. Working Paper, Banco

de Mexico.

Carta, F. and Rizzica, L. (2018). Early Kindergarten, Maternal Labor Supply and Children’s

Outcomes: Evidence from Italy. Journal of Public Economics, 158(C):79–102.

Cerdan-Infantes, P. an d Vermeersch, C. (2007). More Time is Better: An Evaluation of

the Full Time School program in Uruguay. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper,

(4167).

Cherlin, A. (1977). The E↵ect of Children on Mar i t al Dissolution. Demography,14(3):265–

272.

Chin, Y.-M. (2012). Male Backlash, Bargaining, or Exposure Reduction?: Women’s Work-

ing Status and Physical Spou sa l Violence in India. Journal of Population Economics,

25(1):175–200.

Contreras, D. and Sep´ulveda, P. (2017). E↵ect of Len gt h en i ng the School Day on Mother’s

Labor Supply. World Bank Economic Review,31(3):747–766.

Dahl, G. B., Løken, K. V., Mogstad, M., and Vea Salvanes, K. (2016). What Is the Case for

Paid Maternity Leave? The Review of Economics and Statistics,98(4):655–670.

de Chai sem a rt i n , C. and D’Hault fœ u i l l e, X. (2020). Di↵eren ce-i n-D i↵er en ces Estimators of

Intertemporal Treatment E↵ects. Available at SSRN 3731856.

19

de Chaisemartin, C. and D’Haultfoeuille, X. (2020). Two-way Fixed E↵ects Regressions with

Several Treatments. Papers 2012.10077, arXi v. o rg.

Dias Mende s, K. ( 2 01 1) . O Impacto do Programa Mais Educa ca o no Desmpenho dos Alunos

da Rede Publica Brasileira. S˜ao Paulo: Universidad de S˜ao Paulo.

Dickert-Conlin, S. (1999). Taxes and Transfers: Their E↵ects on the Decision to End a

Marriage. Journal of Public Economics,73(2):217–240.

Eckho↵ Andresen, M. and Havnes, T. (2019). Child Care, Parental Labor Supply and Tax

Revenue. Labour Economics,61:101762.

Estefan D´avi l a, M. A. (2018). Male-Female Earnings Inequality and Di vorce Decisions.

Unpublished Manuscript.

Eswaran, M. and Malhotra, N. (2011) . Dom est i c Violence and Women’s Autonomy in De-

veloping Countries: Theory and Evidence. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue cana-

dienne d’´economique,44(4):1222–1263.

Garc´ıa-Ramos, A. (2021). Divorce Laws an d Intimate Partner Vio l en ce : Evidence from

Mexico. Journal of Development Economics,150:102623.

Gelbach, J. B. (2002). Publ i c School i n g for Young Children and Matern a l Labor Supp l y .

American Economic Review,92(1):307–322.

Goodman-Bacon, A. (2021). Di↵erence-in-Di↵erences with Variation in Treatment Timing.

Journal of Econometrics, 225(2):254–277. Themed Issue: Treatment E↵ect 1.

Goux, D. and Maurin, E. (2010). Publ i c School Availability for Two-Year Ol d s and Mothers’

Labour Supply. Labour Economics,17(6):951–962.

Guarnieri, E. and Rainer, H. (2018). Female Empowerment an d Male Backlash. CESifo

Working Paper Seri es.

20

Haerpfer, A., Inglehart, R., C., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J.,

Lagos, M., Norris, P., Ponarin, E., and et al. (eds.), B. P. (2020). World Values Survey:

Round Seven - Cou ntry-Pooled Datafile. Madrid, Spain & Vienna, Austria: JD Systems

Institute & WVSA Secretariat. doi:10.14281 / 18 24 1 . 13 .

Halla, M., Lackner, M., and Scharler, J. (2016). Does the Welfare State Destroy the Fam-

ily? Evidence from OECD Member Countries. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics,

118(2):292–323.

Hankins, S. and Hoekstra, M. (2011). L u cky in Life, Unlucky in Love? The E↵ect of Random

Income Shocks on Marr i age and Divorce. The Journal of Human Resources, 46(2):403–426.

Heath, R. (2014). Women’s Access to Labor Market Opportuniti es, Control of House-

hold Resources, and Domestic Violence: Evidence from Bangladesh. World Development,

57(C):32–46.

Heath, R. and Jayachandran, S. (2018). The Cau ses and Consequences of Increased Female

Education and Labor Force Participation in Developing Countries. In S. Averett, L. A.

and Ho↵man, S., editors, , Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy.

Heckman, J. J. (2006). Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged

Children. Science,312(5782):1900–1902.

Hincapie, D. (2016) . Do Longer School Days Improve Student Achievement? Evidence from

Colombia. IDB Working Paper Seri es.

Hoehn-Velasco, L. and Penglase, J. (2021). T h e impact of no-fault unilateral divorce laws

on divorce rates in mexico. Economic Development and Cultural Change,70(1):203–236.

Ho↵man, S. D. and Duncan, G. J. (1995). The E↵ect of Incomes, Wag es, and AFDC Benefits

on Marital Disruption. Journal of Human Resources,30(1):19–41.

21

Holland, P. A., Alfaro, P., and Evans, D. (2015). Extending the School Day in Latin America

and the Caribbean. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper,(7309).

Jalovaara, M. (2003). The Joint E↵ects of Marriage Partners’ Socioeconomic Positions on

the Risk of Divorce. Demography,40(1):67–81.

Jayachandran , S. (2021). Social Norms as a Barri e r to Women’s Employment in Developing

Countries. IMF Economic Review,69:576–595.

Kozhaya, M. and Mart´ınez Flores, F. (2020). Schooling and Child Labor: Evidence from

Mexico’s Full-Time School Program. Ruhr Economic Papers 851, RWI - Leibniz-Institut

f¨ur Wirtschaftsforschung, Ruhr-University Bochum, TU Dortmund University, University

of Duisburg-Essen.

Krishnan, S., Rocca, C. H., Hubbard, A. E., Subb i ah , K., Edmeades, J., and Padian, N. S.

(2010). Do Changes in Spousal Employment S t at u s Lead to Domestic Violence? Insights

from a Prospective Study in Bangalore, India. Social Science & Medicine,70(1):136–143.

Kruger, D. and Berthelon, M. (2009). Delaying t h e Bell: The E↵ects of Longer School

Days on Adolescent Mo t h er h ood in Chile. IZA D i scu s si on Paper s 4553, Ins ti t u t e of Labor

Economics (IZA).

Lefebvre, P. and Merrigan, P. ( 2 00 8 ). Child-Care Policy and the Labor Supply of Mothers

with Young Children: A Natural Experiment from Ca n ad a . Journal of Labor Economics,

26(3):519–548.

Llamb´ı, M. C. (2013). El Efecto Causal de la Pol´ıtica de Tiempo Completo sobre los Resulta-

dos Educativos en la Ense˜nanza Media: Aplicaci´on de Cuatro M´et odos no Experimentales

eIdentificaci´ondePosiblesSesgos.Unpublished working paper.

Luke, N. an d Mun sh i , K. (2011). Women as Agents of Change: Female Income and Mobil i ty

in India. Journal of Development Economics,94(1):1–17.

22

Majlesi, K. (2016). Labor Market Opportunities an d Women’s Decision Making Power within

Households. Journal of Development Economics, 119(C):34–47.

Nollenberger , N. and Rodriguez-Planas, N. (2015). Full-Time Universal Childcare in a Con -

text of Low Maternal Employment: Qua si -Ex perimental Evidence from Spain. Labour

Economics, 36(C):124–136 .

Orkin, K. (2013). The E↵ect of Lengthening the School Day on Children’s Achievement in

Ethiopia. Working Paper.

Padilla-Romo, M. (2022). Full-Tim e Schools, Policy-Induced S chool Switching, and Aca -

demic Performance. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization,196:79–103.

Padilla-Romo, M. and Cabrera-Hern´andez, F. (2019). Easing th e Constraints of Motherhood:

The E↵ects of All-Day Schools on Mothers’ La bor Supp l y . Economic Inquiry,57(2):890–

909.

Pires, T. and Urzua, S. (2010). Longer School Days, Better Outcomes? Northwestern

University.

Ross, H., Sawhill, I., and MacIntosh, A. ( 19 7 5) . Time of Transition: The Growth of Families

Headed by Women. Th e Urb an Institute.

Sun, L. (2 02 1 ). Eventstudyinteract: Stata module to implement the interaction weighted

estimator for an event study.

Sun, L. and Abraham, S. (2021). Estimating Dynamic Treatment E↵ects in Event Studies

with Heterogeneous Treat m ent E↵ects. Journal of Econometrics,225(2):175–199.

Talamas, M. (2020). Grandmothers and the Gender Gap in the Mexican Labor Market. IDB

Working Paper Seri es.

Weiss, Y. and Willis, R. J. (1997). Match Quality, New Information, and Marital Dissolution.

Journal of Labor Economics,15(1):S293–S329.

23

Xerxenevsky, L. L. (2012). Programa Mai s Educa¸c˜ao: Avalia¸c˜ao do Impacto da Educa¸c˜ao

Integral no Desempenho de Alunos no Ri o Gr an d e do Sul.

24

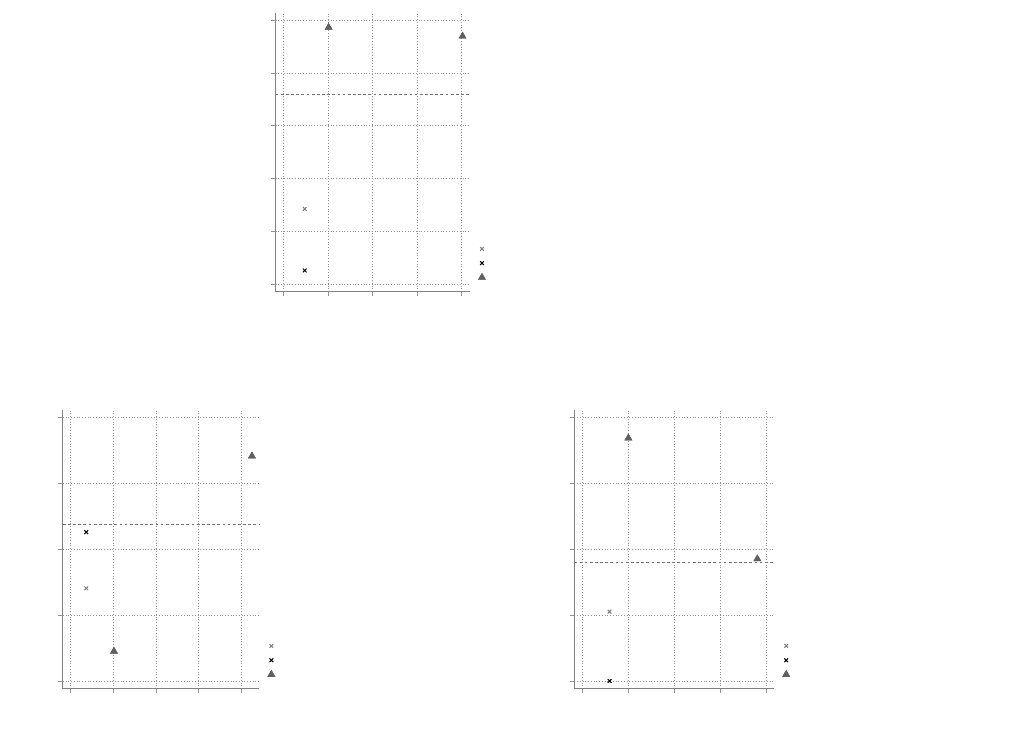

Figure 1: Municipalities with and without Full-time Schools by Academic Year

(a) 2008/09 (b) 2010/11

(c) 2012/13 (d) 2015/16

Notes: Each panel shows all 2,456 municipalities in Mexico and the staggered adoption of the Full-time Schools program. Overall, 220 municipalities

had FTS in 2008/09, 495 in 2010/11, 891 in 2012/13, and 1527 in 2015/16.

25

Figure 2: Estimated E↵e ct s on Municipalities’ Predicted Full-time Schools Availability and Divorce Rate

(a) Average E↵e ct s on Predicted Full-time Schools Avail-

ability

(b) Average E↵ects on Divorce Rate

Notes: Panel (a) shows the evolution of the predicted share of Full-time Schools seats in a municipality

after its first expansion of the Full-time Schools program. Panel (b) shows the estimated e↵ects of the

availability of Full-time Schools on divorce rates. All estimates are obtained using the de Chaisemartin

and d’Haultfoeuille (2020)’s estimator and include municipality fi x ed e↵ects, academic year fixed e↵ects,

and municipality-specific linear time trends. Standard errors for confide nc e intervals are clustered at the

municipality level and bootstrapped based on 1,000 repetit i on s.

26

Figure 3: Bacon Decompositi on : E↵ects on Female Employment

(a) Overall

(b) Municipali t i es with Low Female Employment

(c) Municipalit i es with High Female Employment

Notes: Panel (a) shows the resu l t s of a decomposition of the e↵ect of the availability of Full-time Schools

on female employment considering all municipalities. Panel (b) and (c), present estimates for municipalities

with fem ale employment below and above the median in 2000, respectively. Estimates are obtained using

the method developed by Goodman-Bacon (2021) . In each panel, the das he d line shows the ATT from the

TWFE estimation and each triangl e corresponds to a di↵erent 2x2 TWF E estimate (treated in 2010 or 2015

versus never treated).

27

Figure 4: Alternative Estimation M et hods for the E↵ects of Full-time Schools on Divorce Rate

(a) OLS-TWFE

(b) de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille (2020)

(c) Borusyak et al. (2021)

(d) Sun and Abraham (2021)

Notes: All estimates include municipality fixed e↵ects, academic year fixed e↵ects, and municipality-specific time trends. St an dar d errors for confidence

intervals are clustered at the municipality level. Coefficients and confidence intervals in panels (a) through (d) are estimated using the Stat a commands

reghdfe, did multiplegt, did imputation, and eventstu dy in teract, respectively, and are plotted using the event plot command.

28

Figure 5: E↵ects on Migration

Notes: Estimated e↵ects on the share of divorces in a municipality and academic year in which the munici-

pality of marriage is di↵erent from the municipality of residence of the wife relative to the overall number of

divorces in the municipality of residence. Estimates come from a single regression that includes municipality

fixed e↵ects, academic year fixed e↵ects, and municipality-specific linear time trends, and are es ti m ate d

using the de Chaisemartin and d’Haultfoeuille (2020)’s method. Standard errors for confidence intervals are

clustered at the municipality level and bootstrapped based on 1,000 repetitions.

29

Table 1: Descript i ve Statistic s by Treatment Intensity

Ever Treated Never Treated Di↵erence

Mean Std Dev Mean Std Dev

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

Divorce Rate (pre-intervention) 0.258 (0.359) 0.123 (0.262) -0.135***

Municipality with High (pre-2008) Di vorce Rate 0.583 (0.493) 0.306 (0.461) -0.277***

Femal e Labor Force Participation (2000) 0.265 (0.108) 0.266 (0.133) 0.000

Municipality with High FLFP (2000) 0.509 (0.500) 0.477 (0.500) -0.033***

Population (in 1,000) 41.788 (112.352) 7.964 (11.185) -33.825***

Municipality with Unilateral Divorce Law 0.454 (0.498) 0.344 (0.475) -0.110***

Notes: The table shows descriptive statistics at the municipality level. Divorce rates are reported for 2000-

2007, prior implementation of the Full-time Schools Program. Municipality with High (pre-2008) Divorce

Rate is an indicator equal to one if the municipality divorce rate in 2000-2007 is above t h e cross-municipalities

median. Female employment is reported for 2000. Municipality with High female employment (2000) is an

indicator equal to one if the municipality female employment in 2000 is above the cross-municipalities median.

Municipality with Unilateral Divorce Law is an indicator equal to one if the municipality is l ocat e d in a State

that passed unilateral divorce l aws by 2016. Never Treated are municipalities that were not covered by the

FTS program by 2016 (N=651). Ever Treated are municipalities that implemented the program by 2016

(N=1,527). Data sources: divorce data from INEGI; Population from CONAPO; and female employment

from 2000 Mexican Population Census (IPUMS). *, **, *** Signi fic ant at the 10%, 5%, and 1% l evels,

respectively.

30

Table 2: Estimated E↵ects on Divorce Rate by Pre-Intervention Divorce Rates

Overall Low Pre-2008 High Pre-200 8

Divorce Rates Divorce Rates

(1) (2) (3)

Initial E↵ect 0.013 0.013 0.016

(0.010) (0.010) (0.016)

Years After = 1 0.021

⇤

0.009 0.040

⇤

(0.012) (0.012) (0.021)

Years After = 2 0.047

⇤⇤⇤

0.022 0.075

⇤⇤⇤

(0.013) (0.015) (0.022)

Years After = 3 0.060

⇤⇤⇤

0.008 0.099

⇤⇤⇤

(0.019) (0.014) (0.031)

Years After = 4 0.076

⇤⇤⇤

0.024

⇤

0.122

⇤⇤⇤

(0.020) (0.014) (0.035)

Years After = 5 0.076

⇤⇤⇤

0.020 0.126

⇤⇤⇤

(0.024) (0.018) (0.043)

Years After = 6 0.105

⇤⇤⇤

0.025 0.177

⇤⇤⇤

(0.028) (0.022) (0.048)

Years After = 7 0.090

⇤⇤

0.016 0.172

⇤⇤⇤

(0.036) (0.028) (0.061)

Average E↵ect 0.046

⇤⇤⇤

0.015 0.077

⇤⇤⇤

(0.012) (0.010) (0.021)

Notes: All estimates in each column come from the same regression that includes municipality fixed e↵ects,

academic year fixed e↵ects, and municipality-specific linear time trends. All specifications are estimated using

the de Chaisemartin and d’Haultfoeuille (2020)’s est i mat or . Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at

the municipality level and bootstrapped based on 1,000 repetitions. Columns ( 2) and (3) show the estimated

e↵ects of the availability of Full Time Schools on divorce rates for municipalities with pre- intervention divorce

rates below and above the cross-municipality median, respectively. *, **, *** Significant at the 10%, 5%,

and 1% levels, respectively.

31

Table 3: Estimated E↵ects on Divorce Rate by Pre-Intervention Female Employment

Overall Low Femal e High Female

Employment Employment

(1) (2) (3)

Initial E↵ect 0.013 0.012 0.014

(0.010) (0.013) (0.015)

Years After = 1 0.021

⇤

0.013 0.028

(0.012) (0.017) (0.018)

Years After = 2 0.047

⇤⇤⇤

0.022 0.071

⇤⇤⇤

(0.013) (0.018) (0.019)

Years After = 3 0.060

⇤⇤⇤

0.011 0.103

⇤⇤⇤

(0.019) (0.021) (0.029)

Years After = 4 0.076

⇤⇤⇤

0.015 0.128

⇤⇤⇤

(0.020) (0.026) (0.029)

Years After = 5 0.076

⇤⇤⇤

0.032 0.116

⇤⇤⇤

(0.024) (0.033) (0.036)

Years After = 6 0.105

⇤⇤⇤

0.049 0.151

⇤⇤⇤

(0.028) (0.033) (0.042)

Years After = 7 0.090

⇤⇤

0.020 0.154

⇤⇤⇤

(0.036) (0.047) (0.055)

Average E↵ect 0.046

⇤⇤⇤

0.018 0.071

⇤⇤⇤

(0.012) (0.015) (0.018)

Notes: All e st i mat es from each column come from the same regression that includes municipality fixed e↵ects,

academic year fixed e↵ects, and municipality-specific linear time trends. All specifications are estimated using

the de Chaisemartin and d’Haultfoeuille (2020)’s est i mat or . Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at

the municipality level and bootstrapped based on 1,000 repetitions. Columns ( 2) and (3) show the estimated

e↵ects of the availability of Full Time Schools on divorce r at es for municipalities with female employment

below and above the median in 2000, respec t i vely. *, **, *** Significant at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels,

respectively.

32

Table 4: Estimated E↵ects on Female Employment - Census Data

(1) (2) (3)

Overall Low Female High Female

Employment Employment

Full Time Schools availability 0.018*** 0.004 0.036***

(0.003) (0.003) (0.005)

N6,5283,2643,262

Municipality FE yes yes yes

Year FE yes yes yes

Baseline Female Employment:

All Ever Treated Municipalities 0.266

(0.107)

Ever Treated Mun i ci pal i t i es with Low Female Employment 0.195

(0.066)

Ever Treated Mu n i ci p a l i t i es with High Female Employment 0.336

(0.092)

Notes: Each column represents a di↵erent regress i on. All estimations include year and municipality fixed

e↵ects. FTS is an indicator for the presence of Full Time Schools in the municipality. Standard errors

in parentheses are clustered at the municipality level. Information from IPUMS for years: 2000, 2010, and

2015. Baseline female employment is reported for Treated Municipalities in each group prior implementation

of the Full Time S cho ol s Program.

*, **, *** Significant at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

33

Appendix A Additional Results

Figure A.1: Estimated E ↵ec t s on Divorce Rate- Controlling for Unilateral Divorce Laws

(a) OLS -TWFE controlling for unilateral divorce laws

(b) Borusyak et al. (2021)’s estimator

Notes: Panel (a) shows the estimated e↵ects using TWFE-OLS regression incorporating an indicator for

the implementation of unilateral divorce laws. In Panel (b), we control for the implementation of u n il at e ral

divorce laws using the imputation estimator developed by Borusyak et al. (2021). All estimates from each

panel come from the same regression that includes municipality fixed e↵ects, academic year fixed e↵ects,

and municipality-specific linear time trends. Standard errors for confide nc e intervals are clustered at the

municipality level and bootstrapped based on 1,000 repetit i on s.

34