4 e Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

e Impact of

Social Media on

Lodging Performance

Chris K. Anderson

, Ph.D., is an associate professor at the Cornell School of Hotel Administration (cka9@

cornell.edu). Formerly on faculty at the Ivey School of Business in London, Ontario, his main research focus is

on revenue management and service pricing. He actively works with numerous industry types in the application

and development of RM, having worked with a variety hotels, airlines, rental car, and tour companies as well as

numerous consumer packaged good and financial services firms. He serves on the editorial board of the Journal of

Revenue and Pricing Management and is the regional editor for the International Journal of Revenue Management.

by Chris K. Anderson

About the Author

Cornell Hospitality Report • November 2012 • www.chr.cornell.edu 5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

S

ocial media has been touted as having an increasingly important role in many aspects of the

hospitality industry, including guest satisfaction and process improvement. However, one of

the more intriguing aspects of social media is their potential to move markets by driving

consumers’ purchasing patterns and inuencing lodging performance. In the absence of a

comprehensive attempt to quantify the impact of social media upon lodging performance as measured

by bookings, occupancy, and revenue, this report uses the unique position of Cornell’s Center for

Hospitality Research to combine data from three CHR research partners (ReviewPro, STR, and

Travelocity), and two other data providers (comScore and TripAdvisor) in a rst attempt at determining

ROI for social-media eorts. e analysis nds the following. First, the percentage of consumers

consulting reviews at TripAdvisor prior to booking a hotel room has steadily increased over time, as

has the number of reviews they are reading prior to making their hotel choice. Second, transactional

data from Travelocity illustrate that if a hotel increases its review scores by 1 point on a 5-point scale

(e.g., from 3.3 to 4.3), the hotel can increase its price by 11.2 percent and still maintain the same

occupancy or market share. ird, to measure the impact of user reviews on hotel pricing power,

consumer demand, and revenue performance the study uses matched-sample data from ReviewPRO

and STR. By matching ReviewPRO’s Global Review IndexTM with STR’s hotel sales and revenue data,

a regression analysis nds that a 1-percent increase in a hotel’s online reputation score leads up to a

0.89-percent increase in price as measured by the hotel’s average daily rate (ADR). Similarly this

1-percent increase in reputation also leads to an occupancy increase of up to 0.54 percent. Finally, this

1-percent reputation improvement leads up to a 1.42-percent increase in revenue per available room

(RevPAR).

Executive Summary

6 e Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

CORNELL HOSPITALITY REPORT

H

otel industry executives and managers have seen much anecdotal evidence that

social media inuence guests’ booking behavior—and thereby rate and occupancy.

However, so far I am aware of no comprehensive analysis of the extent to which

social media postings move markets. e cooperation of three Cornell Center for

Hospitality Research partners makes such an analysis possible, as presented in this report. ose

partners, ReviewPro, STR, and Travelocity, make data available on a non-disclosure basis for aggregate

analysis, in this case, an estimate of return on investment for social-media activities. For this report,

comScore and TripAdvisor also provided data.

e Impact of Social Media on

Lodging Performance

by Chris K. Anderson

Cornell Hospitality Report • November 2012 • www.chr.cornell.edu 7

In this CHR Report, I analyze the eect of social media

upon consumers’ purchase decisions and hotels’ top-line

performance. Using online consumer panel data from

comScore, the study illustrates the upstream impact of

TripAdvisor on online hotel reservations. In this portion of

the study, I show that the percentage of consumers consulting

reviews at TripAdvisor prior to booking a hotel room has

steadily increased over time, as has the number of reviews

they are reading prior to making their hotel choice. Using

transactional data from Travelocity, I illustrate the impact

of user reviews upon consumers’ hotel choice at the time of

purchase. Data from purchased and non-purchased hotels

illustrate that if a hotel increases its review scores by 1 point

on a 5-point scale (e.g., from 3.3 to 4.3), the hotel can increase

price by 11.2 percent and still maintain the same occupancy

or market share. Last I measure the impact of user reviews

on hotel pricing power, consumer demand, and revenue

performance using matched-sample data from ReviewPRO

and STR. By matching ReviewPRO’s Global Review IndexTM

with STR’s hotel sales and revenue data, I estimate the impact

of hotels’ online reputation in social-media channels upon

hotel performance. I demonstrate that a 1-percent increase

in a hotel’s online reputation score leads up to a 0.89-percent

increase in price as measured by the hotel’s average daily rate

(ADR). Similarly this 1-percent increase in reputation also

leads to demand creation with up to a 0.54-percent increase

in occupancy. Finally, this 1-percent reputation improvement

leads up to a 1.42-percent increase in revenue per available

room (RevPAR).

is research is the rst to perform an assessment of the

inuence of social media upon hotel performance by illustrat-

ing the increasing role of social media in the research phase

and how this ultimately leads to hotel pricing power and

revenue generation. is is a step beyond earlier eorts that

focused more on the use of social media rather than its

impact on performance.

1

Similar to the early days of elec-

tronic distribution,

2

social media and user-generated con-

tent are of increasing importance in the eyes of hospitality

companies as consumers become more engaged across

numerous platforms during the decision process. One of

the aims of this study is to help shed light on why some

hotel companies are able to achieve price and occupancy

premiums in this new environment.

3

User Generated Content During Consumers’

Hotel Search

TripAdvisor is by far the dominant source for online

reviews in the hospitality space, with more than 75 million

reviews generated by some 32 million users.

4

In terms of

the hotel choice process, as reported by Market Metrix,

5

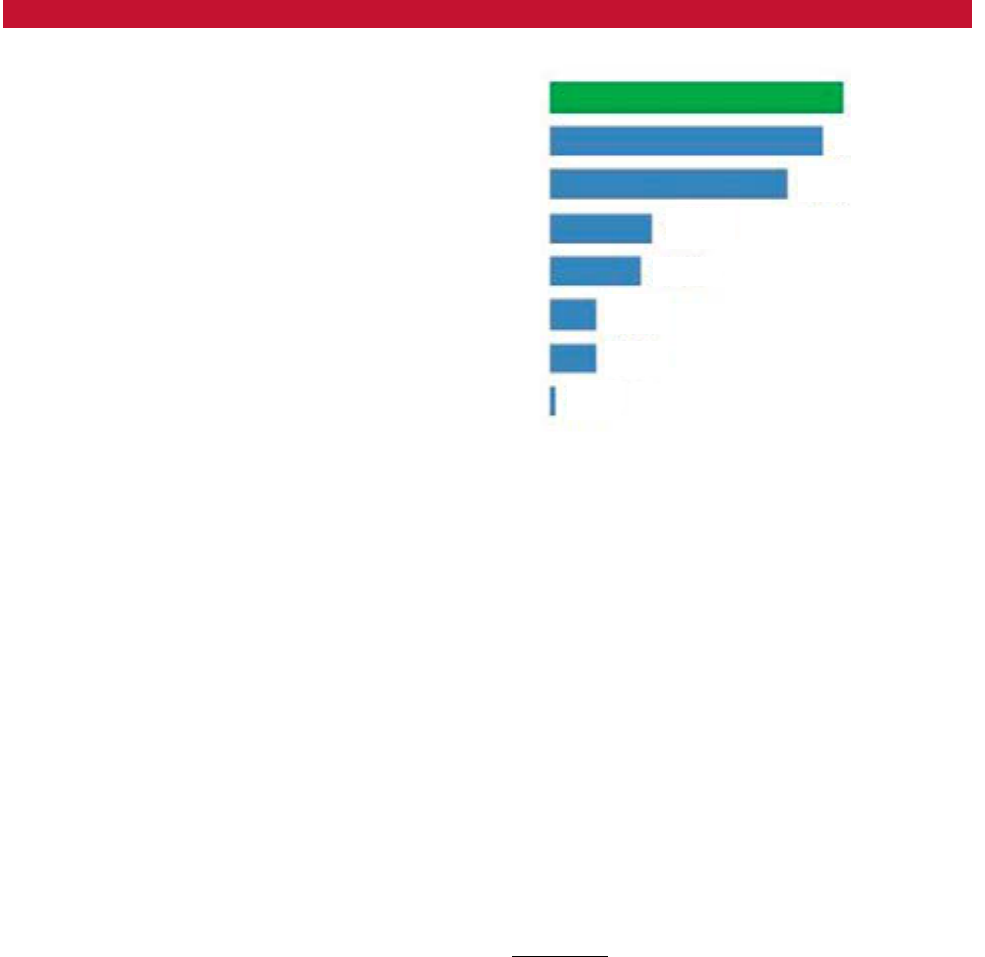

the tipping point came in 2010, as shown in Exhibit 1. At

this point, the guest experience mentioned in customer re-

views became the dominant factor in hotel selection, with

51 percent of survey respondents indicating they factored

1

Rohit Verma and Ken McGill, “Travel Industry Benchmarking: Mar-

keting ROI, Opportunities, and Challenges in Online and Social Media

Channels for Destination and Marketing Firms,” Cornell Hospitality

Report, Center for Hospitality Research, Vol. 11 No. 9 (2011).

2

Judy Siguaw and Bill Carroll, “Evolution in Electronic Distribution: Ef-

fects on Hotels and Intermediaries,” Cornell Hospitality Report, Cornell

Center for Hospitality, Vol. 3 No 5 (2005).

3

Cathy A. Enz, Linda Canina, and Mark Lomanno, Competitive Hotel

Pricing in Uncertain Times,” Cornell Hospitality Report, Center for

Hospitality Research, Vol. 9 No. 10 (2010).

4

TripAdvisor.com, viewed October 2012.

5

Jonathan Barsky and Lenny Nash, “What Is More Important than

Location in Selecting a Hotel?,” Hotel & Motel Management, January 13,

2010 (www.marketmetrix.com/en/default.aspx?s=research&p=MoreImp

ortantanLocation).

E

xhibit

1

Factors in hotel selection

Guest Experience Factors

Location

Price

Loyalty Program Points

Promotions

Amenities

Convention

Green Program

51%

48%

42%

18%

16%

8%

8%

1%

Study by Market Metrix. Hotel &

Motel Management, January 13, 2010.

reviews in the hospitality space, with more than 75 million reviews

generated by some 32 million users.4 In terms of the hotel choice

process, as reported by Market Metrix,5 the tipping point came in

2010, as shown in Exhibit 1. At this point, the guest experience

mentioned in customer re- views became the dominant factor in hotel

selection, with 51 percent of survey respondents indicating they

factored guest experience factors into their hotel selection decision.

Given TripAdvisor’s dominance in the generation of user reviews I

focused on how often consumers consult TripAd- visor prior to

booking a room using publicly available data from comScore.

8 e Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

guest experience factors into their hotel selection decision.

Given TripAdvisor’s dominance in the generation of user

reviews I focused on how oen consumers consult TripAd-

visor prior to booking a room using publicly available data

from comScore.

TripAdvisor Trac Prior to Brand.com

Reservation

Using online consumer panel data from comScore I tracked

TripAdvisor.com utilization during consumers’ hotel re-

search phase. e comScore panel measures how consumers

behave in the digital environment, specically their internet

browsing, buying, and other activity. e rm does this by

continuously measuring the online site visits made by ap-

proximately 2 million worldwide consumers.

is comScore dataset consists of 1,720 purchase events

(hotel reservations) at InterContinental Hotels Group’s

HolidayInn.com site during nine months: June, July, and

August of 2008, 2009, and 2010. is is an example of a

brand’s website that has come to be generically known as

Brand.com. Owing to the nature of the comScore data I have

all travel-related website visits (e.g., TripAdvisor.com, Orbitz.

com, LasVegas.com) and travel-related searches (i.e., Google,

Yahoo, and Bing) for 60 days prior to each of these reserva-

tions. us I can track the clickstream where consumers

went online prior to making a reservation at the suppliers’

Brand.com website, and determine what sort of travel-relat-

ed research they performed. As one would expect; consum-

ers who make reservations online also spend a great deal of

time online researching those transactions.

I focused on TripAdvisor reviews in this study. For a

more generalized look at online behavior, please see my

CHR Report, “Search, OTAs, and Online Booking: An

Expanded Analysis of the Billboard Eect.”

6

Exhibit 2 sum-

marizes TripAdvisor behavior of guests who book directly at

the Brand.com website. As shown, an increasing proportion

of guests over the three years are visiting TripAdvisor prior

to booking with the hotel directly. Not only is the fraction of

consumers increasing, but those consumers that do visit are

visiting more oen (that is, visits per reservation are increas-

ing) and they view more pages overall (although pages per

visit and time per visit dropped slightly). I believe the drop

in time per visit may be due to a more ecient TripAdvi-

sor experience and faster connections (and computers) or

simply the increase in consumers’ search abilities.

Exhibit 3 summarizes customer activity in terms of

when they visit TripAdvisor prior to booking their hotel at

6

C.K. Anderson, “Search, OTAs, and Online Booking: An Expanded

Analysis of the Billboard Eect,” Center For Hospitality Research Report,

Vol 11 No 8 (2011).

E

xhibit

2

TripAdvisor visitation prior to Brand.com booking

Year

% of Brand.com

visiting TripAdvisor

Visits per

reservation Pages per visit

Time per visit

(minutes)

2008 28% 3.71 6.89 4.52

2009 26% 3.78 6.19 4.27

2010 36% 4.72 5.51 3.44

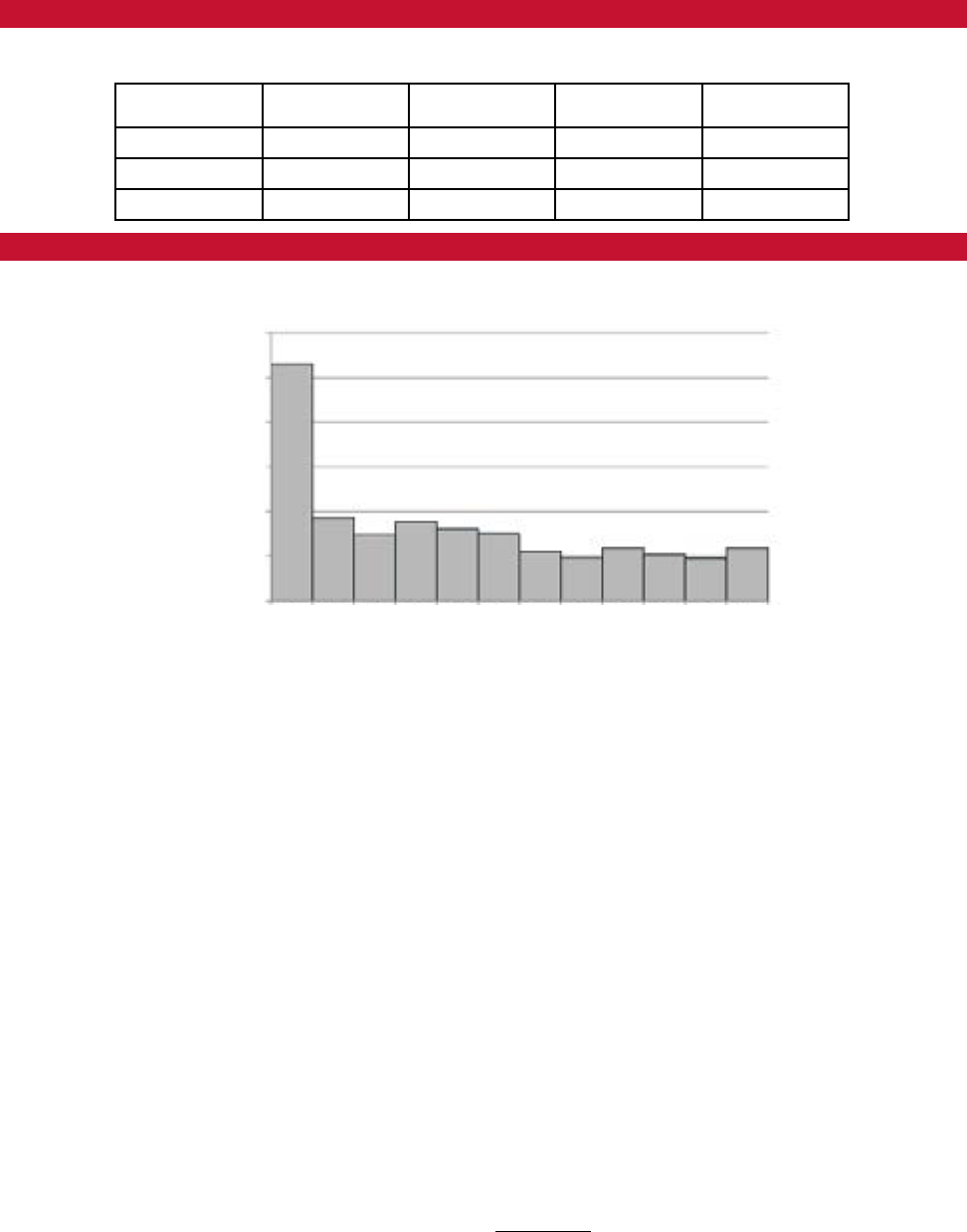

E

xhibit

3

Distribution of when guests visit TripAdvisor.com

Percentage of TripAdvisor Visits

Days Before Reservation

0.3

0.25

0.2

0.15

0.1

0.05

0

5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60

Cornell Hospitality Report • November 2012 • www.chr.cornell.edu 9

the hotel’s website. A little more than one-fourth (26.5%) of

TripAdvisor visits occur in the last ve days prior to the res-

ervation, with the remaining three-quarters roughly equally

spread out over the other 55 days. is may be an indication

of how guests’ research intensies just prior to making the

purchase decision. e close proximity (to the purchase) of

consumer visitation to TripAdvisor perhaps indicates that

user reviews are some of the nal and potentially pivotal

criteria in the hotel selection process.

Point of Purchase Impact

Moving away from Brand.com, let’s look at the impact

of user reviews at a dierent point of purchase, in this

case, at an online travel agency. I analyzed the impact of

user reviews at Travelocity.com upon the purchases made

through that site. e data consist of 13,341 reservations

made during July 2012 in nine major U.S. cities.

7

For each

of these 13 thousand-plus reservations, I have information

(as provided by a typical OTA display) for the property

purchased, as well as all other properties not purchased on

the nal page the customer looked at prior to selecting the

property in question.

Using these data we can gain insight into some of the

key attributes that drive hotel selection decisions. Speci-

cally, I estimate the probability a customer would purchase

a given hotel as a function of price, user review ratings, and

the number of user reviews. Because the outcome variable is

binary (1 or 0; 1 for purchase, 0 for non-purchase), regu-

lar linear regression can’t be used to estimate the impacts

of these attributes upon the purchase decision. However,

logistic regression can be applied. Using logistic regression

I model the probability that a customer would purchase a

listed hotel given its attributes (e.g., price, star rating). e

logistic regression model given here:

Probability of Purchase | X =

7

Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, New York,

Orlando, and Phoenix.

is similar to linear regression where outcomes are mod-

eled as a function of a constant (α) and some attributes (X),

which are weighted by parameters (β) modied with the

use of Euler’s number or e, a mathematical constant equal

to about 2.71828. Please contact me if you would like a

discussion of the technical issues behind why we need such a

model. For this purpose, what is important to realize is that

the βs in logistic regression, as in regular regression, indicate

the impact of the attribute upon the outcome.

Exhibit 4 summarizes parameter estimates from a

logistic regression model of purchase decisions. To account

for the hotel’s position on the screen, I added a variable,

Position, to the independent variables. Position describes

the placement of the hotel in the list of hotels (e.g., 1st, 2nd,

or 3rd, from the top and so forth). Position takes values of

1-25 with 1 being the top position and 25 at the bottom of

the list. Owing to the dierences in prices across chain scales

I use a relative price measure. e Price variable is a hotel’s

price divided by the average price of all same star hotels co-

listed with the subject hotel. I also control for chain scale by

adding an indicator variable for each star level. Of particular

interest are the remaining two variables, review scores and

review volume and their impacts upon price. Using the

regression I estimate how much higher the hotel could price

if it had better review scores.

Given the nature of logistic regression, the parameter

estimates (the βs) are not as easily interpreted as in regu-

lar regression. Instead of using the parameter estimates,

we focus on the odds ratio. e odds ratio represents the

change in the odds of an option being chosen (in this case,

that is the odds of the hotel being booked) given a one-unit

change in the attribute. e odds are the probability of being

selected divided by probability of not being selected ( ).

e Position value of 0.885 demonstrates the negative

eect of being ever lower on the search results. If a hotel is

listed at spot 2 versus 1 (or 10 versus 9) its odds of being

selected decrease to 0.885 of the odds of being selected when

in position 1. at equates to an 11.5-percent decrease in its

chances for every notch it drops (all else being equal).

α+βX

1+e

α+βX

e

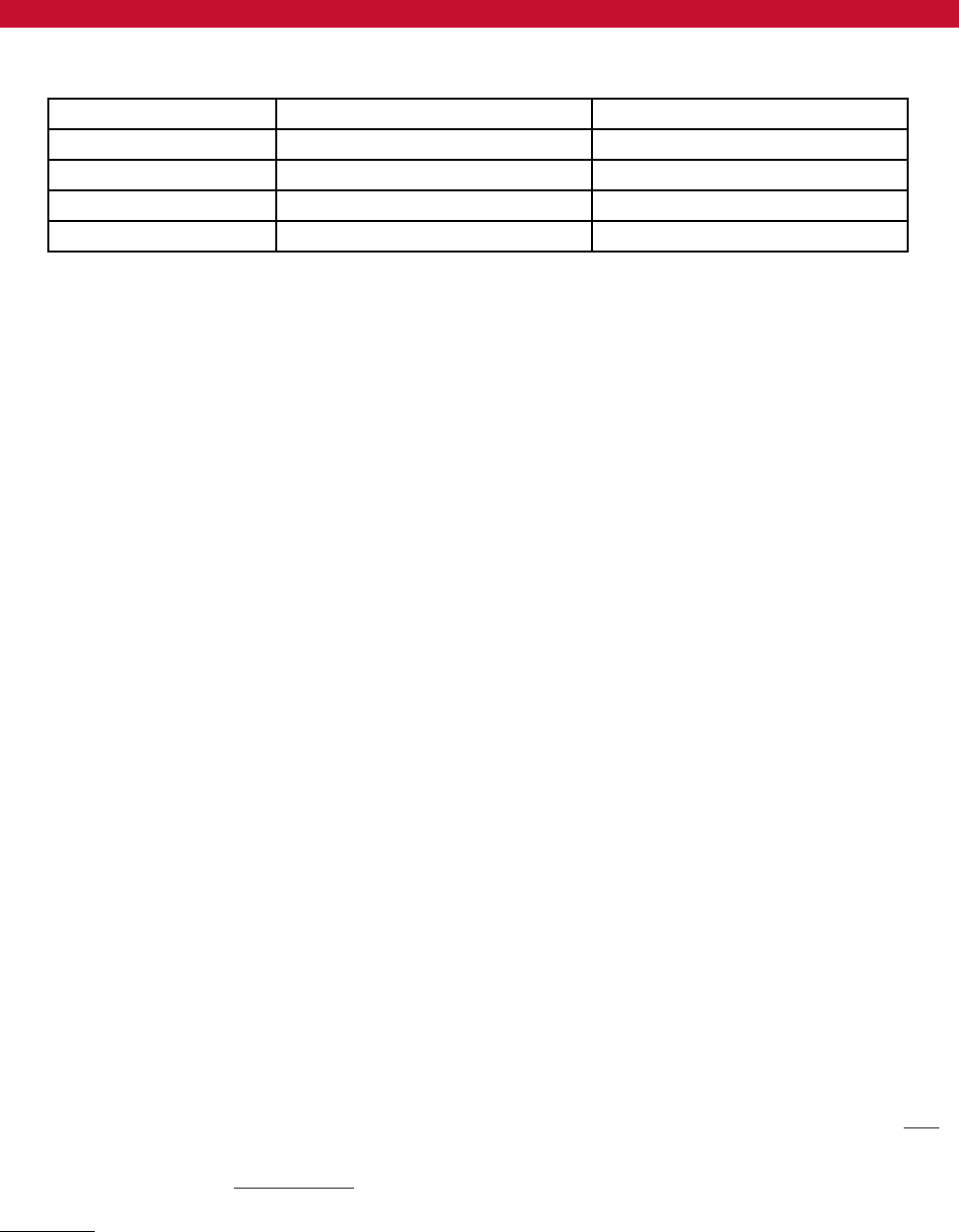

Parameter Estimates* Odds Ratio

Position

-0.1218 0.885

User review score

0.133 1.142

Number of reviews

0.0025 1.002

Relative price

-1.192 0.304

*All significant at 0.001 level.

E

xhibit

4

Logistic regression results: position, reviewer score, number of reviews, and relative room price

P

1-P

Given the nature of logistic regression, the parameter estimates (the βs)

are not as easily interpreted as in regular regression. Instead of using the

parameter estimates, we focus on the odds ratio. The odds ratio

represents the change in the odds of an option being chosen (in this case,

that is the odds of the hotel being booked) given a one-unit change in the

attribute. The odds are the probability of being P selected divided by

probability of not being selected (P divided by 1 minus P). The Position

value of 0.885 demonstrates the negative effect of being ever lower on the

search results. If a hotel is listed at spot 2 versus 1 (or 10 versus 9) its

odds of being selected decreases to 0.885 of the odds of being selected

when in position 1. That equates to an 11.5 - percent decrease in its

chances for every notch it drops (all else being equal).

10 e Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

e results of review scores move in the other direc-

tion. Using Travelocity’s 5-point score for user reviews, the

Review Score odds ratio means that increasing one point

increases the odds of being selected by 14.2 percent Using

the example of a hotel that goes from a review score of, say,

3.3 to one of 4.3, that property has increased its odds of be-

ing selected by 1.142 times the odds when its review score

was 3.3. A similar result is found for Number of reviews.

e 1.002 indicates that for each new review a hotel adds, it

increases its odds of being selected increase by 1.002 or 0.2

percent.

It is a little harder to interpret the odds ratio of price in

this equation because this variable is actually relative price.

Price is perhaps best understood by combining the eects

of price and review scores. Say that the average price of all

competing hotels (those with the same star rating) that ap-

pear on the list page with our hotel was $100 and our hotel’s

price was $100. If we were to increase our review score from

3.3 to 4.3 we could increase our price about 11.2 percent and

maintain the same probability of being selected. e posi-

tive eect of the review score change on the odds of being

chosen would oset the presumably negative odds caused by

a price increase.

Impact on Hotel Performance

Taking the analysis one step further, I analyze the eect of

social presence on overall hotel performance, again using

matched samples of performance data and online reputation

data. Performance data are monthly revenue, demand, and

supply data from STR for 2½ years (January 2010 through

June 2012) for each subject property. I also compared each

hotel with its specied list of competitors, to gain a sense of

relative performance in an eort to control for seasonality.

I have these data for 11 major markets (6 European and 5

North American cities).

8

I use ReviewPro’s Global Review Index (GRI) for the

subject hotels as well as each hotel within its STR listed com-

petitive set as a measure of online reputation. ReviewPro

aggregates hundreds of millions of social media mentions,

in over 35 languages, from Online Travel Agencies (OTAs),

review websites and social media platforms. eir GRI is

an aggregate online reputation score for an individual hotel,

group of hotels, or chain. It is based on scores given by re-

viewers on major online review sites and online travel agen-

cies (OTAs). e GRI is calculated by analyzing quantitative

scores on these sites, using a proprietary algorithm.

9

With this matched data set we look at the impact of GRI

on three typical industry metrics: ADR (average daily rate),

8

Berlin, Chicago, London, Madrid, Miami, Milan, Los Angeles, New

York, Prague, Rome, and San Francisco.

9

More details on the Global Review Index can be found at www.review-

pro.com/product/global-review-index.

occupancy, and RevPAR (revenue per available room). In all

cases, I am using an index. us the measurements are the

eect of GRI against a hotel’s pricing power as measured by

its ADR Index, which is a hotel’s average daily rate divided

by the average of its competitors’ ADRs; the GRI’s impact

upon demand as measured by the occupancy index, and on

overall performance as measured by GRI upon a RevPAR

index. Likewise, the GRI Index is calculated as the subject

hotel’s GRI divided by the average GRI of its competitive set

hotels. is GRI Index is the independent variable. Similar

to many marketing actions

(e.g., advertising and pricing)

we can anticipate decreasing marginal returns.

10

at is, as

the GRI score increases the additional impact upon per-

formance decreases. To incorporate decreasing marginal

returns, I use a multiplicative model of impact oen referred

to as a constant elasticity model. Using price and demand as

an example I illustrate this approach as follows.

Price elasticity of demand is dened as the percentage

change in demand for a given percentage change in price. So,

for example, if price increased by1 percent, and as a result

demand fell 2 percent, then elasticity is -2 (-2%/1%). Price

elasticity (ε) can be expressed as:

where ε is the price elasticity, P is the price, and Q is the

quantity demanded.

If we propose decreasing marginal returns, a demand

model might look like Q=aPb. If we take the natural loga-

rithm (the inverse of Euler’s number) of each side of this

equation we get a log-linear demand model of the following

form:

lnQ = a + b·lnP

where Q and P are dened as before, and a and b are pa-

rameters to be estimated. e log-linear demand function

implies that the price elasticity of demand is constant:

Using data from over 50,000 monthly observations

from the eleven global cities, we can look at the impact of

GRI upon performance in this log linear framework where

I model the impact of ln(GRI Index) upon ln(ADR Index),

ln(Occupancy Index), and ln(RevPAR Index), using three

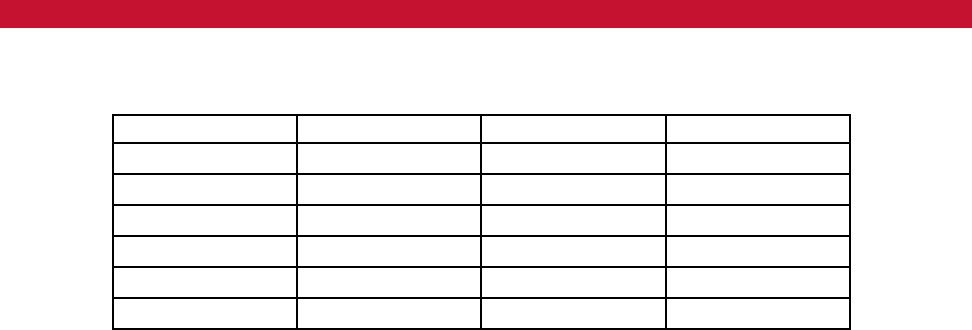

log linear models. Exhibit 5 summarizes the elasticities

for GRI upon these three performance metrics. e table

indicates a stronger impact of GRI upon pricing power

10

For an example of the diminishing marginal returns principle, see:

Joseph omas, “Linear Programming Models for Production-Adver-

tising Decisions,” Management Science, Vol. 17, No. 8 (April 1971), pp.

B-474–B-484.

ε =

dlnQ

=

%∆Q

%∆P

∂Q

∂P

ε =

P

Q

dlnP

b

=

Cornell Hospitality Report • November 2012 • www.chr.cornell.edu 11

(ADR) than on demand (Occupancy). is indicates rms

are pricing consistent with their value proposition. Better re-

views lead to higher prices, while lower reviews force prices

lower for hotels to achieve similar occupancies under both

settings. As the impacts of GRI upon demand and pricing

power are both positive, the impact upon performance or

RevPAR is even stronger. e rst row in Exhibit 5 looks at

all chain scales together, with the subsequent rows looking

at online reputation impact by chain scale. e table entries

represent the percentage impact upon pricing, demand, and

performance given a 1-percent change in online reputation

as measured by GRI. Looking at the rst row, a 1-percent

increase in a hotel’s GRI score, say from 80 to 80.8 aligns

with a 0.96-percent increase in RevPAR. It is interesting to

compare the RevPAR elasticity across chain scales, as the

eect of online reputation is stronger for lower-end chain

scales. us, the gain from online reputation improvement is

much more profound for a midscale property (1.42%) than

for a luxury hotel (.49%). Given the vast diversity of service

levels in midscale hotels, would-be guests may experience

more uncertainty in the level of service in lower chain scales.

us, it makes sense that reviews in the form of the GRI

have a much stronger eect on lower chain scales. e im-

provement in online reputation represented by a strong GRI

reduces the level of service quality uncertainty in the eyes

of consumers. As a result those highly rated rms have in-

creased pricing power compared to those with lower ratings.

Summary

Hotel operators have suspected that the eect of social

media and user generated content on hotel performance

has been strengthening. is paper provides a numerical

conrmation and estimate of those eects. Reviews and

review sites continue to be in the forefront when consumers

are planning a hotel room purchase. Our comScore sample

indicates that the percentage of consumers consulting online

review sites prior to their purchase is increasing with time,

and the number of visits per person also has grown notice-

ably. With regard to online reviews, TripAdvisor continues

to play an increasing role in the eyes of consumers, and with

its marketing options this site has the potential to aect

hotel performance as it acts as a portal to brand sites. More

generally, OTA reviews, their quality and numbers, lead to

increased conversion rates and improved pricing power at

the OTA, as evidenced by our investigation of transactions

at Travelocity. Using logistic regression to model purchase

incidence I estimate that a 1-point increase in user review

score (on an OTA’s 5-point scale) would allow a property

to increase price by 11.2 percent and maintain the same

purchase probability or market share. Last, the cumulative

impact of user reviews across all channels shows a positive

relationship with overall hotel performance. We see that

improved online reputation, as measured by ReviewPRO’s

GRI, results in increased pricing power and occupancy for a

hotel. e model estimates that a 1-percent increase in GRI

leads to as much as a 0.89-percent increase in ADR, and a

0.54-percent increase in occupancy. Combining these eects,

a 1-percent increase in GRI results in up to a 1.42-percent

increase in RevPAR.

As a note of caution this study has focused on the

impact of user generated content and hotel performance.

Needless to say, many factors contribute to hotel perfor-

mance that are not measured here. at said, these results

are generalizable to the extent that the factors that are not

measured are random across the rms in our samples. As I

attempted to collect a sample across a wide spectrum loca-

tions, it is reasonable to say that these results do apply to

hotels generally.

n

E

xhibit

5

GRI elasticity

Pricing Power (ADR) Demand (Occupancy) Performance (RevPAR)

All

0.80 0.20 0.96

Luxury

0.44 0.09 0.49

Upper Upscale

0.57 0.30 0.74

Upscale

0.67 0.19 0.83

Upper MidScale

0.74 0.42 1.13

MidScale

0.89 0.54 1.42

12 e Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

Cornell Center for Hospitality Research

Publication Index

www.chr.cornell.edu

Cornell Hospitality Quarterly

http://cqx.sagepub.com/

2012 Reports

Vol. 12 No. 14 HR Branding How

Human Resources Can Learn from

Product and Service Branding to Improve

Attraction, Selection, and Retention, by

Derrick Kim and Michael Sturman, Ph.D.

Vol. 12 No. 13 Service Scripting and

Authenticity: Insights for the Hospitality

Industry, by Liana Victorino, Ph.D.,

Alexander Bolinger, Ph.D., and Rohit

Verma, Ph.D.

Vol. 12 No. 12 Determining Materiality in

Hotel Carbon Footprinting: What Counts

and What Does Not, by Eric Ricaurte

Vol. 12 No. 11 Earnings Announcements

in the Hospitality Industry: Do You Hear

What I Say?, Pamela Moulton, Ph.D., and

Di Wu

Vol. 12 No. 10 Optimizing Hotel Pricing:

A New Approach to Hotel Reservations,

by Peng Liu, Ph.D.

Vol. 12 No. 9 e Contagion Eect:

Understanding the Impact of Changes in

Individual and Work-unit Satisfaction on

Hospitality Industry Turnover, by Timothy

Hinkin, Ph.D., Brooks Holtom, Ph.D., and

Dong Liu, Ph.D.

Vol. 12 No. 8 Saving the Bed from

the Fed, Levon Goukasian, Ph.D., and

Qingzhong Ma, Ph.D.

Vol. 12 No. 7 e Ithaca Beer Company:

A Case Study of the Application of the

McKinsey 7-S Framework, by J. Bruce

Tracey, Ph.D., and Brendon Blood

Vol. 12 No. 6 Strategic Revenue

Management and the Role of Competitive

Price Shiing, by Cathy A. Enz, Ph.D.,

Linda Canina, Ph.D., and Breni Noone,

Ph.D.

Vol. 12 No. 5 Emerging Marketing

Channels in Hospitality: A Global Study of

Internet-Enabled Flash Sales and Private

Sales, by Gabriele Piccoli, Ph.D., and

Chekitan Dev, Ph.D.

Vol. 12 No. 4 e Eect of Corporate

Culture and Strategic Orientation on

Financial Performance: An Analysis of

South Korean Upscale and Luxury Hotels,

by HyunJeong “Spring” Han, Ph.D., and

Rohit Verma, Ph.D.

Vol. 12 No. 3 e Role of Multi-

Restaurant Reservation Sites in Restaurant

Distribution Management, by Sheryl E.

Kimes and Katherine Kies

Vol. 12 No. 2 Compendium 2012

Vol. 12 No. 1 2011 Annual Report

2012 Tools

e Hotel Reservation Optimizer, by Peng

Liu

Vol. 3 No. 3 Restaurant Table Simulator,

Version 2012, by Gary M. ompson,

Ph.D.

Vol. 3 No. 2 Telling Your Hotel’s

“Green” Story: Developing an Eective

Communication Strategy to Convey

Environmental Values, by Daphne A.

Jameson, Ph.D., and Judi Brownell, Ph.D.

Vol. 3 No. 1 Managing a Hotel’s

Reputation: Join the Conversation, by

Amy Newman, Judi Brownell, Ph.D. and

Bill Carroll, Ph.D.

2012 Proceedings

Vol. 4, No. 6 Fostering Ethical Leadership:

A Shared Responsibility, by Judi Brownell,

Ph.D.

Vol. 4 No. 5 Branding Hospitality:

Challenges, Opportunities, and Best

Practices, by Chekitan Dev, Ph.D., and

Glenn Withiam

Vol. 4 No. 4 Connecting Customer Value

to Social Media Strategies: Focus on India,

by Rohit Verma, Ph.D., Ramit Gupta, and

Jon Denison

Vol. 4 No. 3 e International Hospitality

Industry: Overcoming the Barriers to

Growth, by Jan Hack Katz and Glenn

Withiam

Vol. 4 No. 2 e Intersection of

Hospitality and Healthcare: Exploring

Common Areas of Service Quality,

Human Resources, and Marketing, by

Brooke Hollis and Rohit Verma, Ph.D.

Vol. 4 No. 1 e Hospitality Industry

Confronts the Global Challenge of

Sustainability, by Eric Ricaurte

2012 Industry Perspectives

Vol. 2 No. 3 Energy University: An

Innovative Private-Sector Solution to

Energy Education, by R. Sean O’Kane and

Susan Hartman

Vol. 2 No. 2 Engaging Customers:

Building the LEGO Brand and Culture

One Brick at a Time, by Conny Kalcher

Vol. 2 No. 1 e Integrity Dividend: How

Excellent Hospitality Leadership Drives

Bottom-Line Results, by Tony Simons,

Ph.D.

Cornell Hospitality Report

Vol. 12, No. 15 (November 2012)

© 2012 Cornell University. This report may

not be reproduced or distributed without the

express permission of the publisher.

Cornell Hospitality Report is produced for

the benet of the hospitality industry by The

Center for Hospitality Research at Cornell

University.

Robert J. Kwortnik, Academic Director

Jennifer Macera, Associate Director

Glenn Withiam, Director of Publications

Center for Hospitality Research

Cornell University

School of Hotel Administration

489 Statler Hall

Ithaca, NY 14853

Phone: 607-255-9780

Fax: 607-254-2922

www.chr.cornell.edu

Advisory Board

Niklas Andréen, Group Vice President Global Hospitality & Partner

Marketing, Travelport GDS

Scott Berman, Principal, Real Estate Business Advisory Services, Industry

Leader, Hospitality & Leisure, PricewaterhouseCoopers

Raymond Bickson, Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer, Taj

Group of Hotels, Resorts, and Palaces

Stephen C. Brandman, Co-Owner, Thompson Hotels

Raj Chandnani, Vice President, Director of Strategy, WATG

Eric Danziger, President & CEO, Wyndham Hotel Group

Benjamin J. “Patrick” Denihan, Chief Executive Officer,

Denihan Hospitality Group

Chuck Floyd, Chief Operating Officer–North America, Hyatt

RJ Friedlander, CEO, ReviewPro

Gregg Gilman, Partner, Co-Chair, Employment Practices, Davis &

Gilbert LLP

Tim Gordon, Senior Vice President, Hotels, priceline.com

Susan Helstab, EVP Corporate Marketing,

Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts

Paul Hineman, Executive Director, National Restaurant Association

Steve Hood, Senior Vice President of Research, STR

Jeffrey A. Horwitz, Chair, Lodging & Gaming Group and Head, Private

Equity Real Estate, Proskauer

Kevin J. Jacobs, Executive Vice President & Chief of Staff, Head of Real

Estate, Hilton Worldwide

Kenneth Kahn, President/Owner, LRP Publications

Keith Kefgen, Chief Executive Officer, HVS Executive Search

Kirk Kinsell, President, The Americas, InterContinental Hotels Group

Radhika Kulkarni, VP of Advanced Analytics R&D,

SAS Institute

Gerald Lawless, Executive Chairman, Jumeirah Group

Steve Levigne, Vice President, U.S. Strategy & Insights, McDonald’s

Corporation

Mark V. Lomanno Executive Board Member, newBrandAnalytics

David Meltzer, Chief Commercial Officer, Sabre Hospitality Solutions

William F. Minnock III, Senior Vice President, Global Operations

Deployment and Program Management, Marriott International, Inc.

Mike Montanari, VP, Strategic Accounts, Sales - Sales Management,

Schneider Electric North America

Shane O’Flaherty, President, Global Inspections and Ratings, Forbes Travel

Guide

Brian Payea, Head of Industry Relations, TripAdvisor

Chris Proulx, CEO, eCornell & Executive Education

Cyril Ranque,

SVP, Global Market Management,

Expedia, Inc.

Umar Riaz, Senior Executive, Accenture

Carolyn D. Richmond, Partner, Hospitality Practice, Fox Rothschild LLP

Susan Robertson, CAE, EVP of ASAE (501(c)6) & President of the ASAE

Foundation (501(c)3), ASAE Foundation

Michele Sarkisian, Senior Vice President, Maritz

Janice L. Schnabel, Managing Director and Gaming Practice Leader,

Marsh’s Hospitality and Gaming Practice

Trip Schneck, Managing Partner, District Hospitality Partners

K. Vijayaraghavan, Chief Executive, Sathguru Management Consultants

(P) Ltd.

Adam Weissenberg, Vice Chairman, Global and U.S. Travel, Hospitality &

Leisure Leader, Deloitte & Touche USA LLP

Thank you to our generous Corporate Members

Senior Partners

Friends

4Hoteliers.com • Berkshire Healthcare • Center for Advanced Retail Technology • Cleverdis • Complete

Seating • Cruise Industry News • DK Shifet & Associates • ehotelier.com • EyeforTravel • The Federation of

Hotel & Restaurant Associations of India (FHRAI) • Gerencia de Hoteles & Restaurantes • Global Hospitality

Resources • Hospitality Financial and Technological Professionals • hospitalityInside.com • hospitalitynet.org •

Hospitality Technology Magazine • HotelExecutive.com • International CHRIE • International Hotel Conference

• International Society of Hospitality Consultants • iPerceptions • JDA Software Group, Inc. • J.D. Power and

Associates • The Leading Hotels of the World, Ltd. • Lodging Hospitality • Lodging Magazine • LRA Worldwide,

Inc. • Milestone Internet Marketing • MindFolio • Mindshare Technologies • PhoCusWright Inc. • PKF Hospitality

Research • Questex Hospitality Group • Resort and Recreation Magazine • The Resort Trades • RestaurantEdge.

com • Shibata Publishing Co. • UniFocus • Vantage Strategy • WIWIH.COM

Partners

Davis & Gilbert LLP

Deloitte & Touche USA LLP

Denihan Hospitality Group

eCornell & Executive Education

Expedia, Inc.

Forbes Travel Guide

Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts

Fox Rothschild LLP

HVS

Hyatt

InterContinental Hotels Group

Jumeirah Group

LRP Publications

Maritz

Marriott International, Inc.

Marsh’s Hospitality Practice

McDonald’s USA

newBrandAnalytics

priceline.com

PricewaterhouseCoopers

Proskauer

ReviewPro

Sabre Hospitality Solutions

Sathguru Management Consultants (P) Ltd.

Schneider Electric

Thayer Lodging Group

Thompson Hotels

Travelport

TripAdvisor

WATG

Wyndham Hotel Group

Accenture

ASAE Foundation

Carlson Rezidor Hotel Group

Hilton Worldwide

National Restaurant Association

SAS

STR

Taj Hotels Resorts and Palaces

The Center for Hospitality Research

Hospitality Leadership Through Learning

ASAE Foundation, Carlson

Rezidor Hotel Group, Hilton

Worldwide, National

Restaurant Association, SAS,

STR, Taj Hotels Resorts and

Palaces

Davis & Gilbert LLP, Deloitte & Touche

USA LLP, Denihan Hospitality Group,

eCornell & Executive Education,

Expedia, Inc., Forbes Travel Guide,

Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts, Fox

Rothschild LLP, HVS, Hyatt,

InterContinental Hotels Group,

Jumeirah Group, LRP Publications,

Maritz, Marriott International, Inc.,

Marsh’s Hospitality Practice,

McDonald’s USA, newBrandAnalytics,

priceline.com,

PricewaterhouseCoopers, Proskauer,

ReviewPro, Sabre Hospitality

Solutions, Sathguru Management

Consultants (P) Ltd., Schneider

Electric, Thayer Lodging Group,

Thompson Hotels, Travelport,

TripAdvisor, WATG, Wyndham Hotel

Group