Journal of Economic Geography (2008) pp. 1–25 doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn007

Value chains, networks and clusters: reframing

the global automotive industry

Timothy Sturgeon*

,y

, Johannes Van Biesebroeck** and Gary Gereffi***

Abstract

In this article, we apply global value chain (GVC) analysis to recent trends in the global

automotive industry, with special attention paid to the case of North America. We use

the three main elements of the GVC framework—firm-level chain governance, power

and institutions—to highlight some of the defining characteristics of this important

industry. First, national political institutions create pressure for local content, which

drives production close to end markets, where it tends to be organized nationally or

regionally. Second, in terms of GVC governance, rising product complexity combined

with low codifiability and a paucity of industry-level standards has driven buyer–supplier

linkages toward the relational form, a governance mode that is more compatible with

Japanese than American supplier relations. The outsourcing boom of the 1990s

exacerbated this situation. As work shifted to the supply base, lead firms and suppliers

were forced to develop relational linkages to support the exchange of complex

uncodified information and tacit knowledge. Finally, the small number of hugely

powerful lead firms that drive the automotive industry helps to explain why it has been

so difficult to develop and set the industry-level standards that could underpin a more

loosely articulated spatial architecture. This case study underlines the need for an

open, scalable approach to the study of global industries.

Keywords: Automobiles, global value chains, networks, clusters, governance, institutions

JEL classifications: L23, L62, F15, R11

Date submitted: 6 November 2007 Date accepted: 11 February 2008

1. Introduction

1

Making sense of how the global economy is evolving is a difficult task. Better

theoretical and methodological tools are urgently needed to analyze the complex web of

influences, actions and feedback mechanisms at work. As national and local economies,

and the firms and individuals embedded in them have come into closer contact through

trade and foreign direct investment, the complexity of the analytical problem has

increased. The classic tools of economics, especially theories of supply and demand

and national comparative advantage, while powerful and astonishingly predictive,

y

MIT.

**University of Toronto

***Duke University

1 This article is based, in part, on research funded by Doshisha University’s ITEC 21st Century COE

(Centre of Excellence) Program (Synthetic Studies on Technology, Enterprise and Competitiveness

Project). Comments provided by Peter Dicken and two anonymous reviewers were extremely helpful. All

responsibility for the content lies with the authors.

ß The Author (2008). Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: [email protected]

Journal of Economic Geography Advance Access published April 2, 2008

have always been too thin and stylized to explain all of the richness of industrial

development and economic life, and correctives have been coming from fields such as

economic sociology, management, economic geography and political science for many

decades.

Institutions—labor unions, industry associations, legal and cultural norms, industry-

specific standards and conventions, etc.—matter. The rules set by states and

multilateral organizations matter. Firms can have substantial power within their

respective industries, and wield it to advance their positions in a variety of ways.

Managers, workers and consumers have agency and can act individually or in groups to

change outcomes. Individuals are not simply managers, consumers and workers, but

men and women with complex identities and a wide variety of motivations and roles in

society. To make matters even more complex, both the tug and flow of place and

history continually shape and reshape what can be observed on the ground at any given

moment. Events are almost always, to some degree, constrained by path dependence

and determined by feedback loops of both the positive and negative kind.

Debates about what, precisely, shapes outcomes in the spatial economy are ongoing

and very useful, but we appear to be a critical juncture where rising complexity from

global integration has begun to overwhelm the slow and partial analytical progress that

has been made in the past 25 years. As researchers begin to probe the most recent

aspects of global integration, such as how American, Japanese, Korean and Taiwan-

based firms interact with each other and with local firms to produce Apple iPods in

southern China for export to world markets (Linden et al., 2007), then some of the core

assumptions of mainstream economics—that demand begets supply, that nations draw

only on their own resources to compete with other nations, that exports reflect the

industrial performance of the exporter, that national and international institutions do

not matter, that firms and individuals act independently, rationally and at arms-length,

and so on—appear as quaint reminders of simpler times. But if the tools of mainstream

economics are being blunted by global integration, so too are those offered by other

social science disciplines, which typically assume levels of institutional, cultural and

geographic cohesiveness and autarky that no longer exist.

How, then, are we to wade through the morass of influences, tendencies and causes

that structure empirical outcomes in the global economy? If global integration will lead

to institutional and strategic convergence, as some believe it will, then seeking larger

patterns could be a waiting game. However, the specificities of institutions, culture and

industry are clearly not eliminated by globalization, but brought into intensified

contact, triggering a process of accelerated change that leads to increasing diversity over

time (Sturgeon, 2007). The result is a rich and roiling stew of causation and outcome

that is extremely difficult to penetrate, both analytically and methodologically.

The concept of global value chains (GVCs) provides a pragmatic and useful

framework as we seek answers to questions about the dynamic economic geography of

industries.

2

GVC analysis highlights three features of any industry: (i) the geography

and character of linkages between tasks, or stages, in the chain of value added activities;

(ii) how power is distributed and exerted among firms and other actors in the chain

and (iii) the role that institutions play in structuring business relationships and

2 See www.globalvaluechains.org for more detail on this approach and a list of publications and researchers

that directly engage with it.

2of25

.

Sturgeon et al.

industrial location. Each of the three elements can contribute to explanations of how

industries and places evolve, and provide insight into how they might evolve in the

future. The chain metaphor is purposely simplistic. It focuses us on the location of work

and the linkages between tasks as a single product or service makes its way from con-

ception to end use, not because this chain of activity occupies the whole of our interest,

but because it provides a systematic and parsimonious way to begin the research process.

In this article, we use GVC analysis to explore trends in the automotive industry, with

special attention paid to the case of North America. In Section 2, we trace debates in

economic geography that have progressed from cluster-centered analysis of social,

industrial and institutional development, to a vision of global-scale networks of

interlinked clusters. In Section 3, we sketch a broad overview of the organizational and

spatial structure of the global automotive industry. In subsequent sections, we use the

three main elements of the GVC framework—inter-firm governance, power and

institutions—to explain a few of the key competitive and geographic features of this

important industry.

2. On clusters, networks and value chains

While the tension between the centrifugal and centripetal tendencies of capitalism has

been theorized as a fundamental characteristic of economic development (Storper and

Scott, 1988; Storper and Walker, 1989), the central focus of geographers has been the

structuring role of place. For geographers, the industrial histories, social organization

and institutions of specific places matter. They enable and set limits on what is possible

and help to structure what comes next through the processes of agglomeration,

increasing returns and path dependence. Path dependence is accentuated in dense social

networks because actors are likely to deepen ties with partners that they have the most

interactions with, especially if those ties are diverse in character and involve trust

(Glu

¨

ckler, 2007, 625).

As Martin and Sunley (2006) argue, such network features are created and reinforced

by geographic proximity and as a result, economic activity often has an important local

dimension. Firms tend to discount distant resources, even when access to them might be

beneficial, and gravitate toward the network and governance structures they inherit

from the local environment. Specialized labor markets and exchanges of tacit

knowledge are especially dense, efficient and vibrant when it is possible for agents to

meet face to face (Storper, 1995). Localization is important in the creation of new

knowledge because innovative work necessarily involves the generation and exchange of

knowledge that has not been rendered portable through codification. Since change in

spatially embedded networks is slow, history matters, as well as geography, and this

further ties sector-specific knowledge and innovative activity to particular places

(Malmberg and Maskell, 1997, 27).

While these are important arguments, one is led to question if economic geography’s

focus on the local has hobbled the field in its analysis of globalization. The processes of

dispersal are not confined to the re-location of economic activity to some newly dynamic

center where the agglomeration process can begin anew (Storper and Walker, 1989), but

also include the unfolding—and perhaps historically novel—dynamics that are presently

driving deep functional integration across multiple clusters (Dicken, 2003, 12), a process

we refer to as global integration.

Value chains, networks and clusters

.

3of25

As important as agglomeration and localized innovation remain, the forces of

dispersal and global integration are also on the march, and this exposes the weak

analytical and methodological tools that economic geographers have developed to

tackle the important questions posed by global integration.

3

More recently, the field of

economic geography has begun to address these questions with greater balance and

sophistication. Instead of continuing to argue for the primacy of clustering and

agglomeration over fragmentation and footlooseness, the focus has shifted to

reconciling the apparently contradictory forces of clustering and dispersal. A number

of recent papers, such as Wolfe and Gertler (2004) and Hansen (2008), focus on how

long distance linkages can work to strengthen clusters and how cluster-based firms

exploit locality-derived advantages when they expand overseas.

A starting point for this strand of the geography literature has been the simple yet

powerful—and quite venerable—notion that tacit information and knowledge are best

developed and exchanged locally, while codified information and knowledge can be

transferred and linked in national- or international-scale networks (Scott, 1988;

Malmberg and Maskell, 1997). In this vision, clusters can be quite specialized if linked

to other specialized clusters through the exchange of codified information and

knowledge. While this resonates with the empirical evidence, more recent work has

begun to move beyond the local–tacit/global-codified dichotomy by pointing out that

tacit knowledge is not always created and exchanged locally. Gertler (2003) began this

discussion by ‘unpacking’ the ‘problem’ of tacit knowledge into three challenges that

firms face: (i) creating it, (ii) finding and appropriating it and (iii) moving it once it has

been appropriated. His argument is that the first problem is best solved with proximity

and the supporting institutions of place, and that the second and third problems are

extremely difficult, time-consuming and costly to achieve because they inevitably

involve the long distance transfer of tacit knowledge.

Bathelt et al. (2004) point out that companies and individuals actively seek solutions

to these problems by building ‘pipelines’ to transmit uncodified information and tacit

knowledge across clusters. In this view, tacit and codified information can be exchanged

locally or globally, although the more spontaneous and serendipitous linking of tacit

information—the ‘buzz’ of the industrial district—tends to remain highly localized.

External pipelines can have an organizational dimension, in the establishment of

subsidiaries or through the build-up of trust- or performance-based inter-firm

relationships, as well as an interpersonal dimension, embodied by the routine travel

and relocation of engineers and managers (Saxenian, 2006), and increasingly, though

the use of advanced communications technologies such as ‘telepresence’ or ‘rich

teleconferencing’ systems. Pipelines can also have an institutional dimension, in

‘communities of interest’ that convene online, or in person at regularly planned

professional meetings and conferences. The firms that create or tap into such pipelines

feed their home clusters with fresh ideas, which tend to spill over to firms that may not

have direct external linkages. The best performing clusters are those that are well

connected to critical outside technical and market information, but not so densely

linked that local networks become diluted and ineffective.

3 Indeed, Dicken (2004) has gone so far as to suggest that globalization constitutes a ‘missed boat’ for the

field. Who, if not geographers, should be shaping our collective notions of globalization?

4of25

.

Sturgeon et al.

As we can see, the field of economic geography has begun to enlarge its analysis of

spatial clustering to encompass questions related to global integration. Economic

activity is organized as a web of more or less specialized industrial clusters that are

becoming increasingly interlinked over time. As new clusters arise and old clusters

create global linkages, the variety, density and geographic scope of functionally linked

economic activity is increasing in scale and scope. Linkages within clusters, because of

social and spatial proximity, are extremely rich and efficient, while linkages between

clusters are worth the effort because they provide access to novel information and

resources not available within the cluster.

While this seems straightforward enough, an imbalance remains in the realm of

theory. Cluster dynamics have been deeply theorized, but the linkages between clusters

have only begun to be examined and discussed in any detail. Local actors can forge

external linkages, and these can carry both tacit and codified information; however, the

focus remains on how these linkages play out within the cluster, not on the larger

economic structures that are created when clusters are woven together. Like Dicken

(2005), we find the local–global dichotomy that lies at the heart of the economic

geography literature useful but ultimately unsatisfactory. What is needed is an open

analytical framework that can accommodate the full range of forces, actors and spatial

scales at work. A comprehensive theory of economic geography should be spatially

scalable and comprised of a set of complementary, interlocking, non-exclusive

predictive models that can shed light on specific issues.

We hope to accelerate this process of theory building by offering the GVC perspective

as a framework for theorizing external linkages that is compatible with the deep

theoretical work that has been accomplished by economic geographers in the realm of

localization. At this point, most serious research on global integration has been carried

out by a diverse, interdisciplinary network of scholars, especially those engaged in direct

observational research of a set of global, or globalizing industries, such as electronics,

furniture, apparel, horticulture, motor vehicles and commodities such as coffee a cacao

(Gereffi, 1994; Borrus et al., 2000; Dolan and Humphrey, 2000; Sturgeon, 2002; Fold,

2002; Kaplinsky et al., 2002; Talbot, 2002; Gibbon, 2003; Gibbon and Ponte, 2005;

Berger and the MIT Industrial Performance Center, 2005; Kaplinsky, 2005, 2006), and

more recently, services (Dossani and Kenney, 2003). As industry after industry has

developed intensifying and often divergent patterns of global integration, such ‘industry

studies’ scholars have found themselves, sometimes quite unintentionally, engaged in

the study of global integration. Because these researchers have allowed themselves to be

led first and foremost by the empirical evidence, not by theory, a search has emerged for

a unifying, open, industry-independent theoretical framework to help identify larger

patterns and account for divergent findings.

This work has generated several important insights that bear on themes in the

economic geography literature. First, the development, maintenance and transfer of

codified information may also require the exchange of baseline tacit information as

codification schemes are created, a process that typically occurs in key industry clusters

(Sturgeon, 2003). Second, the exchange of codified information is rarely perfect,

especially when transactions are very complex, and significant ancillary tacit

interactions are commonly required as problems arise. Finally, and perhaps most

importantly, locally forged relationships are often projected globally through a process

described by Humphrey and Memedovic (2003) as follow sourcing, where large suppliers

follow their customers’ investments abroad. Such global suppliers can even act as

Value chains, networks and clusters

.

5of25

proxies for their customers in new locations (Sturgeon and Lester, 2004). Thus, we are

reminded that capabilities are bundled within firms, as well as localities, and that local

and distant linkages are not mutually exclusive, but part of a nested and increasingly

integrated spatial economy that involves cohesion at all spatial scales, local, national,

continental and global.

There have been several sustained efforts to systemize observed patterns in global

industries, most notably the global production networks (Coe et al., this issue; Dicken

et al., 2001; Henderson et al., 2002; Dicken, 2005; Yeung et al., 2006), and GVCs

(Gereffi and Kaplinsky, 2001; Gereffi et al., 2005; Sturgeon, forthcoming), approaches.

In our view, the value chain metaphor is the more useful heuristic tool for focusing

research on complex and dynamic global industries. The chain metaphor is not literal or

exclusive. It does not assume a unidirectional flow of materials, finance or intellectual

exchange, although a focus on buyer power does encourage researchers to be on the

lookout for top-down governance and power asymmetries. A value chain can usefully

be conceptualized as a subset of more complex and amorphous structures in the spatial

economy, such as networks, webs and grids (Pil and Holweg, 2006). Value chains

provide a snapshot of economic activity that cut through these larger structures, while

at the same time clearly identifying smaller scale entities and actors, such as workers,

clusters, firms, and narrowly defined industries (Sturgeon, 2001). This ‘meso-level’ view

of the global economy provides enough richness to ground our analysis of global

industries, but not so much that it becomes bogged down in excessive difference and

variation, or is forced into overly narrow spatial, analytic or sectoral frames in response

to the overwhelming complexity and variation that researchers inevitably encounter in

the field.

As Humphrey and Schmitz (2002) have pointed out, cluster research and theory have

focused almost exclusively on the internal governance of localities while conceptualizing

external linkages simplistically as either contained within multi-locational firms or

made through arms-length trading relationships. GVC research and theory, by contrast,

has the opposite geographic focus, but posits a range of governance structures that go

beyond the vertically integrated transnational corporations and arms-length cross-

border market transactions envisioned by the cluster literature. The theory of

governance contained in the GVC framework identifies three intermediate modes of

value chain coordination (modular, relational and captive) that are, in part, determined

by variables that have been identified by cluster researchers as being important: (i) the

complexity of information exchange; (ii) the codifiability of knowledge and (iii) the

capabilities resident in the supply-base (Gereffi et al., 2005). The complementary nature

of the two streams of scholarship represents an opportunity that we will explore

through the case of the automotive industry.

3. GVCs in the automotive industry: a nested structure

From a geographic point of view, the world automotive industry, like many others, is in

the midst of a profound transition. Since the mid-1980s, it has been shifting from a

series of discrete national industries to a more integrated global industry. In the

automotive industry, these global ties have been accompanied by strong regional

patterns at the operational level (Lung et al., 2004; Dicken, 2005, 2007). Market

saturation, high levels of motorization, and political pressures on automakers to

6of25

.

Sturgeon et al.

‘build where they sell’ have encouraged the dispersion of final assembly, which now

takes place in many more places than it did 30 years ago. While seven countries

accounted for about 80% of world production in 1975, 11 countries accounted for

the same share in 2005 (Automotive News Market Data Books, various years). The

widespread expectation that markets in China and India were poised for explosive

growth generated a surge of new investment in these countries.

Consumer preferences sometimes require automakers to alter the design of their

vehicles to fit the characteristics of specific markets.

4

In other places, automakers want

their conceptual designers to be close to ‘tuners’ to see how they modify their

production vehicles. These motivations have led automakers to establish a series of

affiliated design centers in places such as China and Southern California. Nevertheless,

the heavy engineering work of vehicle development, where conceptual designs are

translated into the parts and sub-systems that can be assembled into a drivable vehicle,

remain centralized in or near the design clusters that have arisen near the headquarters

of lead firms.

5

The automotive industry is therefore neither fully global, consisting of a set of linked,

specialized clusters, nor is it tied to the narrow geography of nation states or specific

localities as is the case for some cultural or service industries. Global integration has

proceeded at the level of design and vehicle development as firms have sought to

leverage engineering effort across products sold in multiple end markets. As suppliers

have taken on a larger role in design, they in turn have established their own design

centers close to those of their major customers to facilitate collaboration.

On the production side, the dominant trend is regional integration, a pattern that has

been intensifying since the mid-1980s for both political and technical reasons. In North

America, South America, Europe, Southern Africa and Asia, regional parts production

tends to feed final assembly plants producing largely for regional markets. Political

pressure for local production has driven automakers to set up final assembly plants in

many of the major established market areas and in the largest emerging market

countries, such as Brazil, India and China. Increasingly, lead firms demand that their

largest suppliers have a global presence as a precondition to be considered for a new

part. Because centrally designed vehicles are manufactured in multiple regions, buyer–

supplier relationships typically span multiple production regions.

Within regions, there is a gradual investment shift toward locations with lower

operating costs: the U.S. South and Mexico in North America; Spain and Eastern

Europe in Europe and South East Asia and China in Asia. Ironically, perhaps, it is

primarily local firms that take advantage of such cost-cutting investments within

regions (e.g. the investments of Ford, GM and Chrysler in Mexico), since the political

pressure that drives inward investment is only relieved when jobs are created within the

largest target markets (e.g. the investments of Toyota and Honda’s in the US and

Canada). Automotive parts, of course, are more heavily traded between regions than

4 Examples include right hand versus left hand drive, more rugged suspension and larger gas tanks for

developing countries, and consumer preferences for pick-up trucks in Thailand, Australia and the United

States.

5 The principal automotive design centers in the world are in Detroit, USA (GM, Ford and Chrysler, and

more recently Toyota and Nissan); Cologne (Ford Europe), Ru

¨

sselsheim (Opel, GM’s European

division), Wolfsburg (Volkswagen) and Stuttgart (Daimler-Benz), Germany; Paris, France (Renault); and

Tokyo (Nissan and Honda) and Nagoya (Toyota), Japan.

Value chains, networks and clusters

.

7of25

finished vehicles. Within countries, automotive production and employment are

typically clustered in one or a few industrial regions. In some cases, these clusters

specialize in specific aspects of the business, such as vehicle design, final assembly or the

manufacture of parts that share a common characteristic, such as electronic content or

labor intensity. Because of deep investments in capital equipment and skills, regional

automotive clusters tend to be very long-lived.

To sum up the complex economic geography of the automotive industry, we can say

that global integration has proceeded the farthest at the level of buyer–supplier

relationships, especially between automakers and their largest suppliers. Production

tends to be organized regionally or nationally, with bulky, heavy, and model-specific

parts production concentrated close to final assembly plants to assure timely delivery,

and lighter, more generic parts produced at distance to take advantage of scale economies

and low labor costs. Vehicle development is concentrated in a few design centers. As a

result, local, national and regional value chains in the automotive industry are ‘nested’

within the global organizational structures and business relationships of the largest firms,

as depicted in Figure 1. While clusters play a major role in the automotive industry, and

have ‘pipelines’ that link them, there are also global and regional structures that need to

be explained and theorized in a way that does not discount the power of localization.

4. The outsourcing boom and rise of the global supplier

One of the main drivers of global integration has been the consolidation and

globalization of the supply base. In the past, multinational firms either exported parts

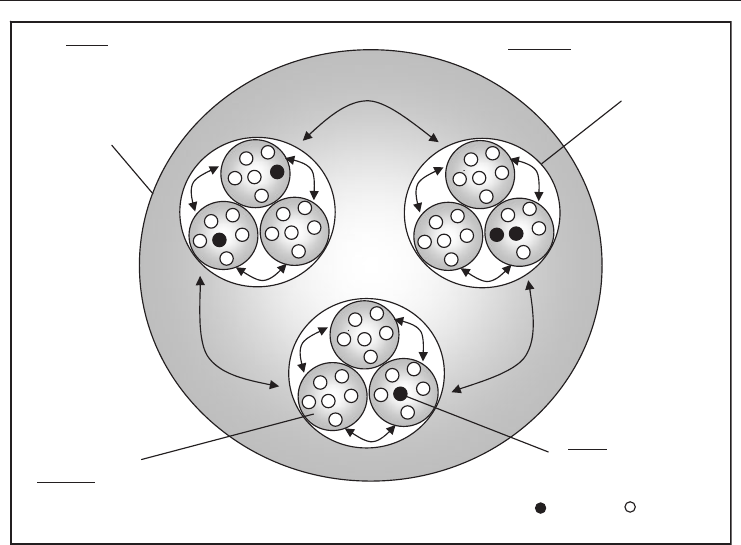

Regional production systems:

Intra-regional finished vehicle and

parts flows are the dominant

operational pattern in this industry.

A global industry:

Automakers and global suppliers

form buyer-supplier relationships

on a global scale. Inter-regional

vehicle and parts trade is

substantial, but capped by political

and operational considerations

National production systems:

Domestic production is still very strong in

this industry, and still dominates many

national markets.

Local clusters:

Activities tend to be

concentrated within clusters of

specialized activity, such as

design and assembly

Figure 1. The nested geographic and organizational structure of the automotive industry.

8of25

.

Sturgeon et al.

to offshore affiliates or relied on local suppliers in each location, but today global

suppliers have emerged in a range of industries, including motor vehicles (Sturgeon and

Lester, 2004). Since the mid-1980s and through the 1990s, suppliers took on a much

larger role in the industry, often making radical leaps in competence and spatial

coverage through the acquisition of firms with complementary assets and geographies.

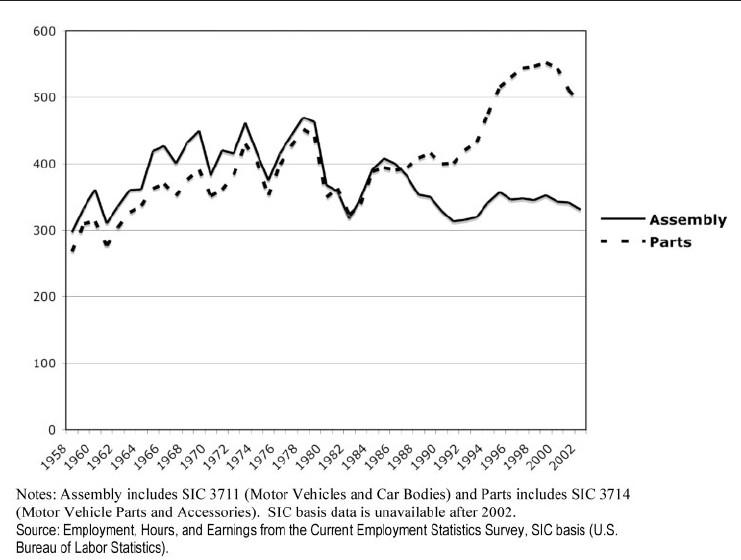

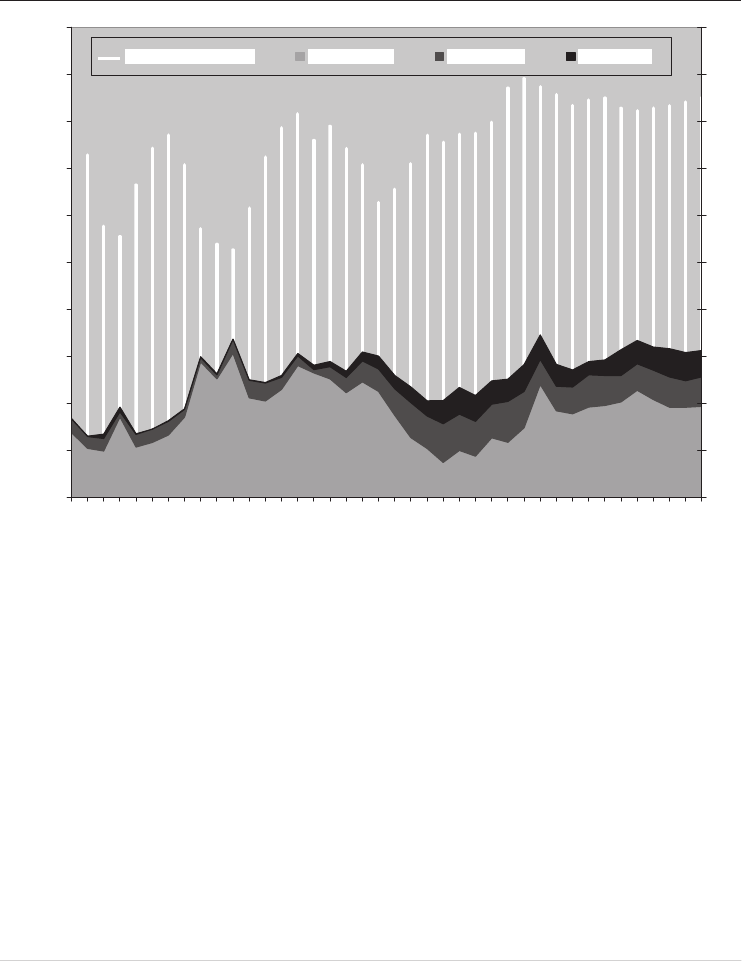

This trend has been most pronounced among US-based suppliers. Figure 2, which

traces the history of parts and assembly employment in the US from 1958 through 2002,

clearly shows this structural shift. Until 1985, parts and assembly employment were

roughly equal. After 1985, employment shifted into the supply base as automakers

made fewer sub-assemblies such as cockpit assemblies, rolling chassis and seats

in-house, purchasing them instead from outside suppliers. This drove rapid growth

among the largest suppliers as well as consolidation, as firms engaged in mergers and

acquisitions to gain the capability to make larger and more complex sub-systems. At the

end of the 1990s, GM and Ford fully embraced the outsourcing trend by spinning off

their respective internal parts divisions, creating what were at the time the world’s two

largest automotive parts suppliers, Delphi and Visteon. Because they were spun out of

huge parent firms with strong international operations, these ‘new’ suppliers were born

with a global footprint and the capability to supply complete automotive subsystems.

6

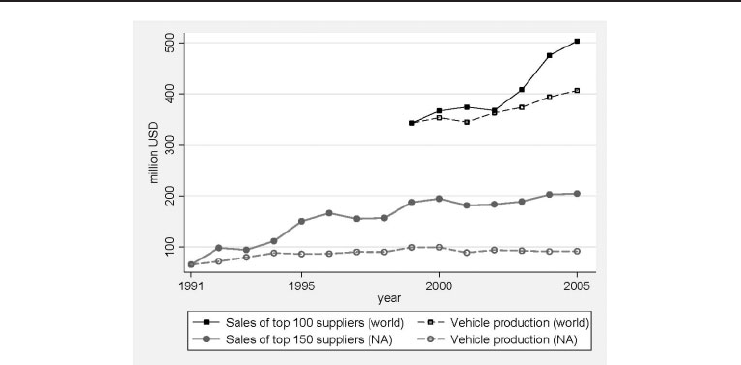

A comprehensive overview of the largest suppliers in the automotive industry is

regularly published by the main trade journal for the North American industry,

Automotive News. Each year, a list is compiled of the top 150 parts suppliers in North

America, the top 30 in Europe and the top 100 in the world. The addresses of

headquarters, areas of specialization and sales are reported for each company.

7

The

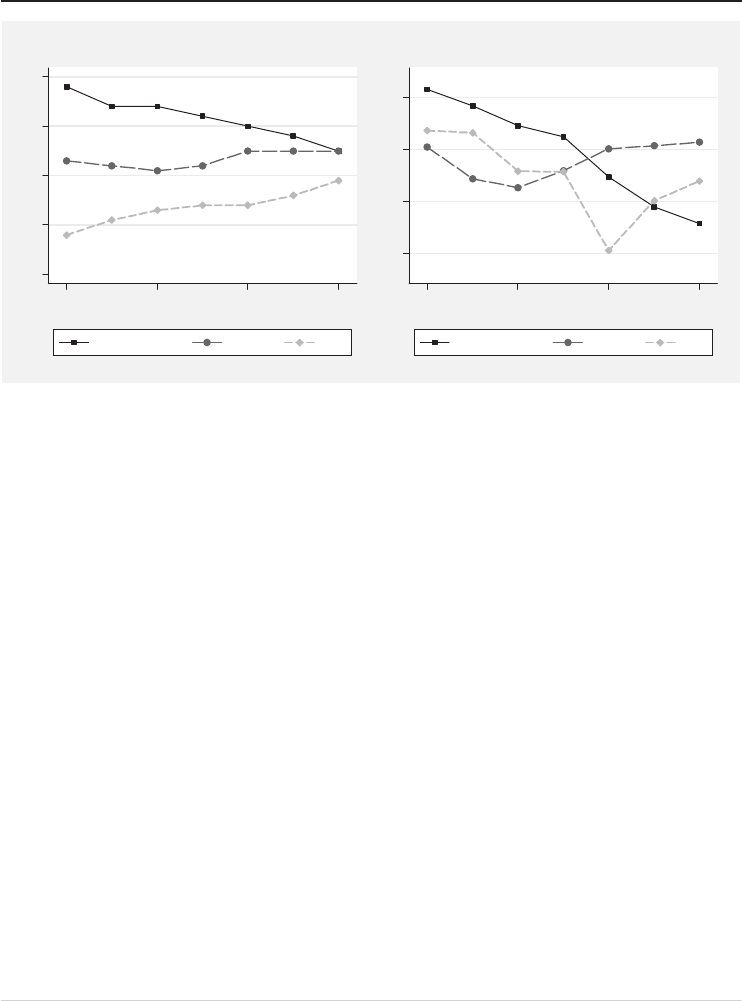

changing composition of the list reveals the emergence of global suppliers. Figure 3

shows the rising importance, in terms of sales, of large suppliers relative to lead firms.

8

In North America (the two grey lines at the bottom of Figure 3), vehicle production

grew by 40% between 1991 and 2005, from 11.6 million to 16.3 million, while the

combined sales of the largest 150 suppliers in North America nearly tripled. At the

global level (the black lines at the top of Figure 3), vehicle production increased by

18.4% from 1999 to 2005, while supplier sales grew at more than twice that pace.

Supplier consolidation at the worldwide level has not progressed as far as in North

America, but it has picked up speed in recent years as the formation of new global lead

firms and groups, such as DaimlerChrysler in 1999 (a deal that was undone in 2007),

Nissan-Renault in 1998, Hyundai-Kia in 1999 and GM and Ford’s purchase of several

smaller companies, has led to the consolidation and integration of formerly distinct

supply bases.

6 For example, according to company reports, Visteon has broad capabilities in chassis, climate, electronics,

glass and lighting, interior, exterior trim and power trains. In 2000, the company operated 38

manufacturing plants in the US and Canada; 23 in West Europe; 21 in Asia; nine in Mexico; six in East

Europe and four in South America. System and module engineering work was carried out in one facility in

Japan, three in Germany, three in England, and four in the US.

7 The list for North America was first published in 1992 and with the exception of 1994 it has appeared each

year since. The European and worldwide lists have been published since 1999.

8 The only output measure we observe for firms on the list is nominal sales, but it is useful to keep in mind

that the price per vehicle (controlling for quality) has remained almost flat over the last 15 years. The CPI

index for new vehicles in the US saw a cumulative increase from 1992 to 2005 of 4.3%; between 1997 and

2005 it even recorded a decline of 5.5%.

Value chains, networks and clusters

.

9of25

As automakers set up final assembly plants in new locations and tried to leverage

common platforms over multiple products and in multiple markets, they pressured their

existing suppliers to move abroad with them. Increasingly, the ability to produce in all

major production regions has become a precondition to be considered for a project.

However, what is emerging in the automotive industry is more complex than a seamless

and unified global supply base, given the competing pressures of centralized sourcing

(for cost reduction and scale) and regional production (for just-in-time and local

content). The need for full co-location of parts with final assembly varies by type of

component, or even in stages of production for a single complex component or sub-

system. Suppliers with a global presence can concentrate volume production of specific

components in one or two locations and ship them to plants close to their customer’s

final assembly plants where modules and sub-systems are built up and sent to nearby

final assembly plants as needed.

What should be clear from this discussion is that the economic geography of the

automotive industry cannot be reduced to a simple network of clusters. Business

relationships now span the globe at several levels of the value chain. Automakers and

first tier suppliers have certainly forged such relationships, and as the fewer, larger

suppliers that have survived have come to serve a wider range of customers, these

relationships have become very diverse. With consolidation, we must question the

Figure 2. Outsourcing in the U.S. automotive industry, assembly and parts employment,

1958–2002.

10 of 25

.

Sturgeon et al.

staying power of smaller, lower tier, local suppliers, however well supported they are by

local institutions and inter-firm networks, especially since many upstream materials

suppliers, such as the automotive paint supplier PPG, are huge companies that have set

up global operations as well.

5. GVC governance in the automotive industry: dealing with

the ‘problem’ of relational linkages

GVC theory identifies five ways that firms coordinate, or govern the linkages between

value chain activities: (i) simple market linkages, governed by price; (ii) modular

linkages, where complex information regarding the transaction is codified and often

digitized before being passed to highly competent suppliers; (iii) relational linkages,

where tacit information is exchanged between buyers and highly competent suppliers;

(iv) captive linkages, where less competent suppliers are provided with detailed

instructions and (v) linkages within the same firm, governed by management hierarchy.

These five linkage patterns can be associated with predictable combinations of three

distinct variables: the complexity of information to be exchanged between value chain

tasks; the codifiability of that information; and the capabilities resident in the supply

base (Gereffi et al., 2005).

In the automotive industry, a paucity of robust, industry-wide standards and

codification schemes limits the rise of true value chain modularity. Why are there so few

open standards and industry-level codification schemes in the automotive industry? We

see two main reasons, the first technical and the second structural. On the technical side,

vehicle performance characteristics such as noise, vibration and handling are deeply

interrelated and it is difficult to quantify their interactions in advance (Whitney, 1996).

Source: Information for the top suppliers is taken from Automotive News (various years).

Information on vehicle production is from Ward’s Automotive Yearbook (2006).

Notes: The scale is for the sales numbers in millions of current U.S. dollars.

The vehicle production series has been scaled to coincide with the relevant sales

number in the initial

y

ear.

Figure 3. The increasing importance of suppliers in the automotive industry.

Value chains, networks and clusters

.

11 of 25

Because of the integral nature of vehicle design architecture, changes in one component

often have an impact on other components (Novak and Wernerfelt, 2006). Rising

vehicle complexity has continued to overwhelm efforts to fully codify vehicle designs or

the design process. The industry has historically relied on inter-personal interaction and

proprietary standards, mostly within the boundaries of vertically integrated firms, to

manage the flow of tacit information from one stage of the chain to the next. As a

result, information exchange between suppliers of complex parts and sub-systems and

lead firms is necessarily very intensive. Suppliers are often the sole source for a myriad

of vehicle- and platform-specific parts, which raises the costs of serving multiple

customers. On the structural side, the extremely concentrated structure of the industry

gives a small number of lead firms an extraordinary amount of power over suppliers. In

GVC parlance, value chains in the automotive industry are strongly ‘driven’ by a small

number (around 11) of producers (Gereffi, 1994). Their huge purchasing power means

that each lead firm can force suppliers to accommodate its idiosyncratic standards,

information systems and business processes.

Because the largest suppliers in the industry have also undergone a massive wave of

consolidation of their own, they have taken on much larger roles in the areas of design,

production, and foreign investment. As the competence to design complex parts and

sub-systems has shifted from automakers to suppliers, the need for co-design has meant

that captive and pure market GVC linkages have become harder to maintain. At the

same time, the lack of open, industry-level standards for vehicle parts and sub-systems

(low codifiability) has blocked the development of industry-wide

codification schemes needed to support modular GVC linkages, heightened the need

for close collaboration, tied suppliers more tightly to lead firms, and limited economies

of scale in production and economies of scope in design.

9

As a result, linkages between

lead firms and suppliers in the automotive industry require tight coordination,

especially in the areas of design, production and logistics (Humphrey, 2003).

American and Japanese lead firms have tended to respond differently to this pressure

to forge deep relational linkages, based in large part on their historical ties to suppliers.

American lead firms have tended to develop market linkages and have used the ability

to switch suppliers to engage in predatory purchasing practices (Helper, 1991). As the

acceleration of outsourcing in the 1990s bundled more value chain functions in supplier

firms, supplier relations did not change. American automakers tend to systematically

break relational ties after the necessary collaborative engineering work has been

accomplished. The result is an oscillation between relational GVC linkages, driven by

the engineering requirements of vehicle development in the context of increased

outsourcing, and market linkages, which are adopted once lead firms put co-developed

parts, modules and sub-systems out for open re-bid after a year or so of production in

an effort to lower input costs. Switching the sourcing of a part, or a sub-system

consisting of many parts, from a supplier that engaged in co-design to a supplier that

did not is only possible once the specifications have been fully developed and stabilized

in the context of high volume production. Reversion to market linkages may keep

9 Lead firms have been trying to decrease the design effort required for vehicle development by sharing

vehicle platforms across a family of vehicle models, but this has its limits. First, platforms are only shared

across brands owned by the same lead firm. Second, to avoid product homogenization and to achieve

performance goals, most parts that are visible to consumers and many that are not, remain model-specific.

12 of 25

.

Sturgeon et al.

supplier power in check, but it wreaks havoc on the accumulated trust needed for

relational linkages function effectively (Granovetter, 1985; Adler, 2001).

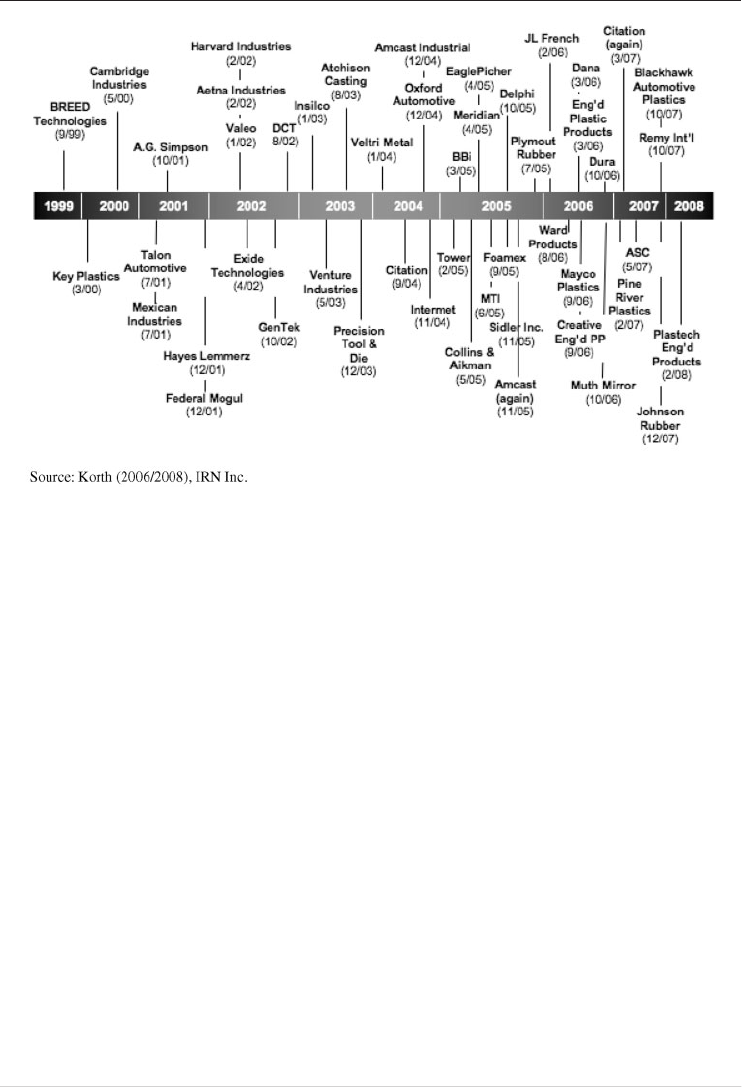

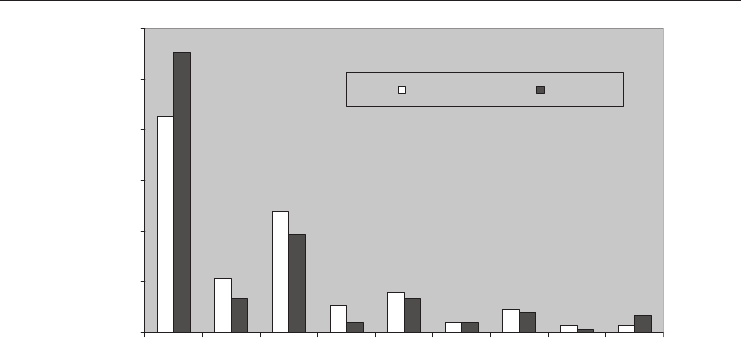

As Herrigel (2004) has shown, this has created deep tensions in the automotive

components industry. Especially relevant here is the fact that suppliers are often

expected to recover the cost of design services as part of winning the initial contract.

For suppliers, the costs of these purchasing practices are extremely high. In fact, high

design costs, which are often only partially compensated because of predatory

purchasing practices and the declining sales volumes of the Big 2, combined with

unexpected rises in the price of raw materials, also uncompensated by the Big 2, are

major factors behind a recent spate of bankruptcies among large automotive suppliers

based in the US (Figure 4).

It is notable that no Japanese suppliers appear in Figure 4. In post-World War II

Japan, lead firms were starved for capital and needed to rely more on suppliers. This

often involved equity ties and suppliers dedicating themselves to serving their largest

customer, in a classic ‘captive’ relationship that became more relational over time as

supplier competence increased. Relative to what American automakers have recently

and quite suddenly asked their suppliers to contribute, Japanese lead firms have limited

co-design with suppliers. Predatory supplier switching is almost unheard of, and long-

term trust-based relationships have been allowed to develop. Paternalistic ‘captive’

linkages to suppliers have been partly maintained, especially when these relationships

have been projected outside of Japan. While Japanese automakers have a higher level of

acceptance of relational GVC linkages than American automakers, Japanese auto-

makers have asked less of their suppliers in the realm of co-design, and this has

provided an alternative mechanism to attenuate supplier power.

The adversarial relationships between American lead firms and their suppliers shows

up clearly in Table 1, which presents an annual ‘working relations index’ calculated by

the consultancy Planning Perspectives. Japanese automakers rely on many locally based

suppliers in North America, and have achieved much better working relationships with

them than the American Big 3. In 2007, 52% of North American suppliers

participated in the survey. They clearly rate their relationships with Japanese lead firms

as better than their relationships with American automakers. Chrysler tended to have

better relationships with suppliers than its American competitors, but recent financial

difficulties have driven the company to predatory buying practices. While ‘bad’ working

relationships are to some extent symptomatic of declining sales volumes, which leads

American automakers to overestimate future sales and makes it harder for suppliers to

recover fixed costs, Japanese lead firms clearly have brought their customary relational

approach to buyer–supplier linkages with them as they have located production in

North America.

In short, place-based institutions are being projected outward as global integration

unfolds. The case of the automotive industry reveals the complexity of social and

institutional embeddedness as the largest firms have established global operations.

When firms set up operations in new places, they rarely abandon their home bases

completely, but remain rooted there in significant ways. Most typically, this involves

command and control functions, the development and deployment of corporate

strategy, and the functions of product conception and design. Even manufacturing

plants are commonly left in operation, both to serve the home market and to

supplement offshore production through exports. In this way, the institutions of

localities and countries continue to influence the behavior of firms at home as well as in

Value chains, networks and clusters

.

13 of 25

the new institutional environments they find offshore (Berger and the MIT Industrial

Performance Center, 2005). Thus, it is not surprising that we find Japanese automakers

behaving like Japanese firms in North America. On the other hand, globalization

is more than the simple offshore projection of national ‘varieties of capitalism’ (Hall

and Soskice, 2001). Firms adapt to, and in some cases actively embrace, different

institutional environments when they move offshore, especially when home institutions

have been perceived as constraints on management action.

10

6. Explaining the strength of regional production

in the automotive industry

Since the late 1980s, trade and foreign direct investment have accelerated dramatically

in many industries. Specifically, a combination of real and potential market growth

with a huge surplus of low-cost, adequately skilled labor in the largest countries in the

developing world, such as China, India and Brazil, has attracted waves of investment,

both to supply burgeoning local markets and for export back to developed economies.

The latter has been enabled and encouraged by the liberalization of trade and

investment rules under an ascendant World Trade Organization (WTO). Yet, regional

production has remained very durable in the automotive industry. As we argued

Figure 4. Major Automotive Supplier Bankruptcies, 1 January 1999 to 10 February 2008.

10 For example, GM and Volkswagen have both used their plants in Brazil and Eastern Europe to

experiment with new production models, work organization practices and supplier relations (Sturgeon

and Florida, 2004).

14 of 25

.

Sturgeon et al.

previously, lead firms in the automotive industry have the power to drive supplier

co-location at the regional, national, and local levels for operational reasons, such as

just-in-time production, design collaboration, and the support of globally produced

vehicle platforms. But politics also motivates lead firms to locate production close to

end markets, and this also creates pressure for supplier co-location.

While consumer tastes and purchasing power, driving conditions, and the nature of

personal transportation can vary widely by country, local idiosyncrasies in markets and

distribution systems are common in many industries, and it is possible to feed

fragmented and variegated distribution systems from centralized production platforms,

as long as product variations are relatively superficial. The continued strength of

regional production in the automotive industry, then, is one of its most striking features

(Lung et al., 2004).

11

The regional organization of vehicle production stands in stark

contrast to other important high-volume, consumer-oriented manufacturing industries,

especially apparel and electronics, which have developed global-scale patterns of

integration that concentrate production for world markets in a few locations.

Why is political pressure for local production felt so acutely in the automotive

industry? The high cost and visibility of automotive products, especially passenger

vehicles, among the general population can create risks of a political backlash if

imported vehicles become too large a share of total vehicles sold. This situation is

heightened when local lead firms are threatened by imports. The case of Japanese

exports to the US in instructive. In the 1960s and 1970s, Japanese (and to a lesser extent

European) automakers began to gain substantial market share in the US market

through exports. Motor vehicle production in Japan soared from a negligible 300 000

units in 1960 to nearly eleven million units in 1982, growing on the strength of Japan’s

largely protected domestic market of about five million units plus exports (Dassbach,

1989). Excluding intra-European trade, Japan came to dominate world finished

Table 1. Index of working relations between lead firms and suppliers

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2002–07 Change (%)

Toyota 0.76 0.80 0.99 1.00 0.98 1.00 32.2

Honda 0.72 0.76 0.93 0.90 0.89 0.92 27.9

Nissan 0.55 0.62 0.73 0.72 0.72 0.70 27.3

Chrysler 0.42 0.43 0.45 0.47 0.53 0.48 13.7

Ford 0.40 0.39 0.39 0.38 0.42 0.39 3.0

GM 0.39 0.38 0.36 0.27 0.32 0.42 8.1

Industry Mean 0.54 0.56 0.64 0.62 0.64 0.65 20.7

Note: The Working Relations Index (WRI) ranks OEMs’ supplier working relations based on 17 criteria across five (5)

areas: OEM-Supplier Relationship, OEM Communication, OEM Help, OEM Hindrance and Supplier Profit Opportunity.

A score below 0.60 is considered to represent very poor to poor supplier working relations; a score between 0.60–0.84

indicates adequate relations and above 0.84 indicates good to very good supplier working relations.

Source: Planning Perspectives, Inc. web site (4 June 2007, press release) http://www.ppi1.com/news/?image¼news

11 Of the three major vehicle-producing regions, regional integration is the most pronounced in North

America. In 2004, 75.1% of automotive industry trade was intra-regional there, in contrast to 71.2% in

Western Europe, and 23% in Asia (Dicken, 2007, 305).

Value chains, networks and clusters

.

15 of 25

vehicle exports by a wide margin, with the bulk of exports going to the U S (Dicken,

2007).

The remarkable success of Japanese automakers’ export strategy resulted in a gain in

market share in the US that came at the direct expense of the American Big 3, sparking

a political backlash that resulted in the setting of ‘voluntary’ limits to market-share

expansion via exports. A stark reality added fuel to the fire: American automakers had

been, and continue to be, unable to penetrate Japan’s domestic market in any

meaningful way. In response to these so-called voluntary quotas, Japanese automakers

embarked on a wave of plant construction in the US during the 1980s, and by 1995 were

locally manufacturing two-thirds of the passenger vehicles they sold in the US

(Sturgeon and Florida, 2004).

12

As Japanese ‘transplant’ production in North America ramped up after 1986,

Japanese exports began a long decline. Table 2 lists existing and planned assembly

plant investments in North America by ‘‘foreign’’ firms. By 2009, transplants in North

America will have the capacity to assemble more than six million units, more than

one-third of projected U.S. demand in 2011, and will employ 90 000 workers,

just under one-third of North American assembly employment in 2005 (Sturgeon

et al., 2007).

Figure 5 shows how U.S. vehicle demand has been satisfied by a combination of

overseas imports, regional imports from Mexico and Canada, and domestic production

during the period 1972–2006 (with 2007–2011 forecast). After an initial build up of

imports from countries outside of NAFTA over the 1972–1982 period, especially Japan,

overseas vehicle imports declined dramatically as Japanese and subsequently European

lead firms established final assembly operations in North America. Since then, overseas

imports have increased as demand, mainly for Japanese vehicles, outstripped installed

capacity in North America. The announced North American assembly plants planned

by Japanese and Korean firms will largely offset the increase in overseas imports

between 1995 and 2006. As a result, we expect that imports from these countries will

again decline, as projected by JD Power. Because of the high cost, large scale, and

long life of assembly plant investments, this cyclical variation in finished vehicle imports

(and assembly plant investments) can be expected in the future if market share

continues to shift in favor of non-US-based firms. Plants will only be added if and when

these firms are confident that market share gains in North America will be long

standing.

This pattern reveals the sensitivity to high levels of imports, especially of finished

vehicles, in places where local lead firms are present, as they are the US. In our view, the

willingness of governments to prop up or otherwise protect local automotive firms is

comparable to industries such as agriculture, energy, steel, utilities, military equipment

and commercial aircraft. As a result, lead firms in these industries have to adjust their

sourcing and production strategies to include a measure of local and regional

production that firms in other industries do not. This explains why Japanese, German

and Korean automakers in North America have not concentrated their production

in Mexico, despite lower operating costs and a free trade agreement with the US

12 Around the same time, starting with Nissan in 1986 in the UK, Japanese firms constructed assembly

plants in Europe to avoid import quotas in France and Italy and import tariffs in most other E.U.

countries.

16 of 25

.

Sturgeon et al.

(Sturgeon et al., 2007).

13

Japanese automakers have also shifted European production

to Eastern Europe later and less aggressively than American and European lead firms,

and have even moved to China later than their European and American competitors.

14

Despite the rise of a more integrated global supply base, described earlier, the

continued strength of regional structures in the automotive industry is still reflected in

the relationship between supplier headquarters and regional sales. As recently as 1999,

almost half of the 100 largest suppliers were based in North America, as this was the

largest regional market. At the same time, regional sales were 70% of total sales for

suppliers based in North America, and 65% for suppliers based in Europe and Japan.

Table 2. Existing and announced foreign assembly plant investment in North America

Company Location Employment

(as of 2004 or

planned)

Investment

($M, through 2005

or planned)

Capacity

(2005 or

planned)

Opening date

(first major

expansion)

Kia Troup County, GA 2500 1200 300,000 2009

Honda Greensburg, IN 2000 550 200,000 2008

Toyota Woodstock, ON 2000 950 150,000 2008

Toyota San Antonio, TX 2000 850 200,000 2006

Hyundai Hope Hull, AL 2000 1100 300,000 2005

Toyota Tecate, MX 460 140 50,000 2005

Nissan Canton, MS 4100 1430 400,000 2003

Honda Lincoln, AL 4300 1200 300,000 2001

Volkswagen Puebla, MX 15,000 NA 380,000 1966 (1998)

Daimler-Benz Vance, AL 4000 2200 160,000 1997

Toyota Princeton, IN 4659 2600 300,000 1996

BMW Spartenburg, SC 4600 2200 200,000 1994

GM/Suzuki Ingersoll, ON 2775 500 250,000 1989

Honda East Liberty, OH 2230 920 240,000 1989

Subaru Lafayette, IN 1315 1350 262,000 1989

Toyota Georgetown, KY 6934 5310 500,000 1988

Mitsubishi Normal, IL 1900 850 240,000 1988

Toyota Cambridge, ON 4342 2400 250,000 1988

Honda Alliston, ON 4375 1500 250,000 1987

GM/Toyota Fremont, CA 5715 1300 370,000 1984

Nissan Smyrna, TN 6700 1600 550,000 1983

Honda Marysville, OH 4315 3200 440,000 1982

Nissan Aguascalientes, Mx NA NA 200,000 1966 (1982)

Total 88,220

33,350

6,292,000

Notes:NA¼ data not available. Dates in brackets indicate major capacity expansions.

Sources: Compiled from Automotive News, Ward’s Automotive, McAlinden (2006) and company websites.

Missing employment from Nissan, Aguascalientes.

Missing investment in Volkswagen, Puebla, Nissan, Aguascalientes, and GM, Spring Hill plants.

13 Volkswagen is exceptional in that it has concentrated all of its North American production in Mexico,

and Nissan is the sole Japanese automaker that has build up large scale, export-oriented final assembly

there.

14 The large U.S. trade deficit with China might have influenced Honda’s decision to export the Honda

Jazz to the European Union from China, while the almost identical Honda Fit for North America is

shipped from Japan.

Value chains, networks and clusters

.

17 of 25

However, Figure 6 illustrates that this situation changed in the following years,

as global sourcing by lead firms increased extra-regional sales by Tier 1 suppliers.

First, global sourcing has caused the list of top suppliers to become more regionally

balanced. The number of top suppliers coming from each of the three regions, in the left

panel, now reflects the worldwide production share of the lead firms of the respective

regions. Second, by 2005 average sales in home regions declined from 68.6% to 61.6%

for the 100 largest suppliers, which are shown broken down by region in the right panel.

The decline has been particularly pronounced for North American-based suppliers.

Asian headquartered suppliers’ increased extra-regional sales modestly and European

suppliers’ extra-regional sales remained flat during the same period. Nevertheless,

examples abound of suppliers from Germany and Japan following their largest

customers offshore as extra-regional final assembly has grown.

15

0

2,000,000

4,000,000

6,000,000

8,000,000

10,000,000

12,000,000

14,000,000

16,000,000

18,000,000

20,000,000

1972 1974 1976 1978 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

sales USA (left scale) from overseas from Canada from Mexico

Source: Ward’s Infobank (1972–2002), Automotive News Data Center (2003–2006), JD Power Automotive Forecasting (2007–2011)

Figure 5. Net vehicle imports in the US from Mexico, Canada and countries outside of North

America, 1972–2011 (forecast).

15 An example of a small Japanese firm that has set up a global operational footprint is F-Tech, a Honda

supplier headquartered in Saitama Prefecture, north of Tokyo. The company produces engine and rear

suspension parts, engine supports, rear axles, pedal and clutch assemblies and bumper beams. The

company began supplying Honda in 1956, and in 1967 established the first of several plants in

Kameyama, a few minutes away from Honda’s assembly complex in Suzuka. Honda and F-Tech engage

in a classic ‘captive’ relationship. Honda provides close guidance in terms of planning, purchasing and

production methods, and accounts for most of F-Tech’s output, especially for offshore plants, which are

typically 100% dedicated to Honda. Over time, F-tech has broadened its customer base in Japan beyond

its lead customer; the company began serving Nissan in 1995, Isuzu in 1997, Daihatsu in 1999 and

18 of 25

.

Sturgeon et al.

7. The persistence of Motor City: the greater Detroit vehicle

development cluster

At the same time that lead firm consolidation and dispersal is being reflected in the

consolidation and dispersion of the supply-base, the increased involvement of suppliers

in design and purchasing has led to the spatial concentration of supplier design

engineering facilities, especially in North America, where lead firms have been the most

aggressive in demanding that suppliers contribute to design efforts. Because the Detroit,

Michigan area has been a center of vehicle design and engineering for nearly 100 years,

the cluster boasts specialized labor markets and a host of institutions to support the

field of automotive engineering. As a result, the regional headquarters of foreign

automakers and global suppliers—typically the site of regional sales, program

management, design and engineering—have gravitated to the Detroit area.

Even though Japanese automakers have built many assembly plants in the U.S.

South, their design and R&D activities tend to be among the most northerly points of

their U.S. operations. In 2005, Toyota consolidated much of its design and R&D

activities in Ann Arbor, Michigan (a 45 min drive from Detroit), even though its North

American manufacturing headquarters are located in Kentucky. In 2006, Nissan moved

its North American headquarters from Los Angeles, California to the Nashville,

Tennessee area. Nissan’s conceptual design center is in San Diego, California, but the

10 20 30 40 50

1999 2001 2003 2005

year

North America Europe Asia

Number of firms (in top 100)

0.55 0.60 0.65 0.70

1999 2001 2003 2005

year

North America Europe Asia

Share of sales in home region

Source: Automotive News top supplier list (various years)

Figure 6. Regional organization of the automotive supply base.

Suzuki in 2001. Outside Japan, however, F-tech’s plants remain tightly linked to Honda’s offshore

assembly plants. In 1986, F-Tech followed Honda offshore, establishing the subsidiary F & P Mfg., Inc.

in Tottenham, Ontario, a few miles from Honda’s Alliston assembly plant, which opened the same year.

In 1993, the company opened F&P America in Troy, Ohio, less than an hour’s drive from Honda’s East

Liberty assembly complex. A technical center and North American headquarters followed in 2001. In

addition to these closely linked facilities, F-tech has several high-volume plants in low cost locations that

are not tied to any one assembly plant, including a plant in Laguna State, the Philippines, established in

1996; a plant in Wuhan, China, near Shanghai, established in 2004; and a plant in Ayutthaya, Thailand,

opened in 2006.

Value chains, networks and clusters

.

19 of 25

8-fold larger engineering-oriented technology center is in Farmington Hills, a Detroit

suburb. Honda’s North American automotive R&D operations are split between

California, near Los Angeles, responsible for market research, concept development

and vehicle styling, and Raymond, Ohio (about 150 miles south of Detroit), responsible

for complete vehicle development, testing and the support of supplier and

manufacturing operations.

As the global consolidation of the supply base has proceeded, suppliers based in

Europe and Asia, such as Yazaki (Japan), Bosch (Germany), Autoliv (Sweden) and

many others, have established major design centers in the Detroit region to support

their interactions with American, and increasingly, Japanese automakers. The head-

quarters location of the largest 150 suppliers in the region, which includes regional

headquarters for some transnational firms, is documented in Figure 7. The importance

of Detroit is striking: by 2005, the majority of the largest suppliers were located in the

Detroit Metropolitan Region. This fraction increased from 43% in 1995 to 55% in

2005. The concentration is even more striking for the 50 largest suppliers: by 2005, 34 of

those were located in the Detroit area, up from 29 in 1995. As regional headquarters

have multiplied in Detroit, the number has fallen in the rest of Michigan and other

Midwestern states, and has dropped to near zero in the Northeast. Even the U.S. South,

which has attracted many new assembly plants in the last decade, has lost supplier

headquarters.

As the largest suppliers locate engineering work near lead firm design facilities, it

places pressure on smaller suppliers to locate engineering work close to their biggest

clients. This is a classic agglomeration dynamic that is strengthening the Detroit

automotive design cluster, even as final assembly is gradually shifting away from the

area. As Bathelt et al. (2004) point out, co-location is by no means an absolute

requirement for transfer of tacit knowledge, nor is it sufficient. In the automotive case,

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Detroit MSA

Michigan

Midwest

North-East

South

West

Canada

Mexico

Overseas

Fraction of top-150 suppliers

1995 2005

Source: Author calculations based on Automotive News top 150 ranking (various years).

Figure 7. Location of (regional) headquarters of top 150 suppliers to the North American

automotive industry.

20 of 25

.

Sturgeon et al.

however, co-location has a strong temporal component. Vehicle programs take shape

over several months or even years, and any lead firm has dozens of programs in

the pipeline at any point in time. Getting involved in these projects would be

extremely difficult for suppliers without a presence in the cluster. Thus in terms of the

development, maintenance, and exchange of tacit knowledge in the automotive

industry, the assumptions of the clusters literature ring true.

8. Conclusions

In this article, we have used the three main elements of the GVC approach—power,

institutions and inter-firm governance—to help to explain some of the distinctive

characteristics of the global automotive industry. One of our goals has been to highlight

several features that set the automotive industry apart from other global goods-

producing industries, such as electronics and apparel. First, the automotive industry is

similar to these others in that the geographic scope of both lead firms and their largest

suppliers expanded in a wave of offshore investments, mergers, acquisitions and equity-

based alliances in the 1990s. In industry after industry, giant firms have arisen in many

vertical segments of the value chain, and these firms are building relationships with one

another at the global level (Sturgeon and Lester, 2004).

Second, the automotive industry, especially firms based in the US, embraced

outsourcing without a robust set of industry standards in place for specifying the

technical characteristics of products and processes. To some extent, this reflects the

difficulty of codifying tacit knowledge about mechanical processes but it also reflects

the strong competition between a tight oligopoly of very powerful lead firms unwilling

to work together to develop robust industry-level standards. Because parts and sub-

systems tend to be specific to vehicle platforms and models, suppliers have been forced

to interact closely with lead firms, which has driven up transaction costs, and limited the

economies of scale in production and economies of scope in design afforded by value

chain modularity. The different approaches that lead firms have taken toward solving

such GVC governance challenges have helped to shape competitive outcomes, for lead

firms and for the supply base as a whole.

Third, in the automotive industry, technical necessity, political sensitivities and

market variation have kept final vehicle assembly, and by extension much of parts

production, close to end markets. Powerful lead firms and industry associations, large-

scale employment and relatively high rates of unionization, and the iconic status of

motor vehicles in the minds of consumers (and policy-makers) in many countries

increase the political clout of the automotive industry. So even where import tariffs and

local content rules are not present or are scheduled to decline under WTO rules, foreign

assemblers have chosen to ‘voluntarily’ restrict exports and set up local production to

forestall political backlash. As a result, regional and national production structures

remain surprisingly strong and coherent in comparison to other volume good producing

industries where global sourcing of parts and materials is the norm and worldwide

demand for finished goods can be met from a handful of giant production clusters. As a

result, political pressures go a long way toward explaining patterns of direct investment

in the automotive industry.

Fourth, the economic geography of the automotive industry is playing out differently

in different segments of the value chain. We see the concentration of design engineering

Value chains, networks and clusters

.

21 of 25

in existing clusters, dispersal of some conceptual design to gain access to ‘lead users’,

regional integration of production, and for some categories of parts, global sourcing.

In all instances, however, it is automakers that drive locational patterns; the influence

that lead firms have on the economic geography of the industry is rooted in their

enormous buying power.

The automotive industry is clustered and dispersed, rooted and footloose. The

industry can be usefully conceived of as a network of clusters, but our conceptual and

methodological tools should not blind us to the importance and durability of structures

that function at the level of continental-scale regions. A theory of economic geography

must be fully scalable to accommodate and account for these variations. It must seek to

accommodate and offer explanation for what appear to be contradictory tendencies in

the spatial organization of capitalism without setting up false contests, for example,

between the relative importance of clustering and dispersal. The value chain perspective,

first and foremost, draws our attention to the division of labor in an industry, especially

its vertical dimension, for the simple reason that various business functions along the

chain have different requirements, and these requirements help to structure the

geography of the chain, and by extension, global industries.

As Ann Markusen (2003) points out, we should be wary of ‘fuzzy concepts’ that are

difficult to operationalize, measure, or feed into policy. It is fair to ask if concepts such

as global value chains and global production networks suffer from such drawbacks. In

our view, the simplicity of the chain metaphor increases its usefulness as a research

methodology and policy input. While we recognize the inherent limits of the GVC

framework, scalable conceptual tools that can help researchers and policymakers move

easily from local to global levels of analysis demand some degree of parsimony. As

global integration continues to drive the complexity of the analytical problem upward,

the need for such guideposts will only grow. While debates over the relative merits of

terms and metaphors, such as commodity chains, value chains, production networks,

and the meaning of terms such as ‘value’ and ‘governance’ will certainly continue, what

this signifies is the emergence of a coherent interdisciplinary intellectual community

with a shared focus on the organizational and spatial dynamics of industries, the

strategies and behavior of major firms and their suppliers, and the structuring roles of

institutions, power, and place. These commonalities, in our view, define a core research

and theory building agenda that cuts across these chain and network paradigms. As we

have pointed out elsewhere (Sturgeon, forthcoming), this theoretical project is at an

early stage of development.

References

Adler, P. (2001) Market, hierarchy, and trust: the knowledge economy and the future of

capitalism. Organization Science, 12(2): 215–234.

Automotive News Market Data Books, various years. Available online at: http://www.autonews.

com/section/DATACENTER, Automotive News Data Center (accessed 13 March 2008).

Automotive News. (Various years) Top 150 North American Suppliers. http://www.autonews.-

com, Automotive News Data Center, accessed March 13, 2008.

Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A., Maskell, P. (2004) Clusters and knowledge: local buzz, global

pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Progress in Human Geography, 28(1): 31–56.

Berger, S. and the MIT Industrial Performance Center (2005) How We Compete. New York:

Doubleday.

22 of 25

.

Sturgeon et al.

Borrus, M., Ernst, D., Haggard, S. (eds) (2000) International Production Networks in Asia:

Rivalry or Riches? London: Routledge.

Dassbach, C. (1989) Global Enterprises and the World Economy: Ford, General Motors, and IBM,

the Emergence of the Transnational Enterprise. New York: Garland Publishing.

Dicken, P. (2003) Global Shift: Reshaping the Global Economic Map in the 21st Century, 4th edn.

London: Sage.

Dicken, P. (2004) Geographers and globalization: (yet) another missed boat? Transactions of the

Institute of British Geographers, 29: 5–26.

Dicken, P. (2005) Tangled webs: transnational production networks and regional integration.

SPACES 2005-04, Phillips-University of Marburg: Germany.

Dicken, P. (2007) Global Shift: Reshaping the Global Economic Map in the 21st Century, 5th edn.

London: Sage Publications.

Dicken, P., Kelly, P. F., Olds, K., Yeung, H. W-C. (2001) Chains and networks, territories and

scales: towards a relational framework for analysing the global economy. Global Networks,1:

89–112.

Dolan, C. and Humphrey, J. (2000) Governance and trade in fresh vegetables: the impact of UK

supermarkets on the African horticulture industry. Journal of Development Studies, 37(2):

147–76.

Dossani, R. and Kenney, M. (2003) Lift and shift; moving the back office to India work in

progress (Sept.). Information Technologies and International Development, Vol. 1, No. 2.

Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 21–37.

Fold, N. (2002) Lead firms and competition in ‘Bi-Polar’ commodity chains: grinders

and branders in the global cocoa-chocolate industry. Journal of Agrarian Change, 2(2):

228–247.

Gereffi, G. (1994) The organization of buyer-driven global commodity chains: how U.S. retailers

shape overseas production networks. In G. Gereffi and M. Korzeniewicz (eds) Commodity

Chains and Global Capitalism. Westport: Praeger, 95–122.

Gereffi, G. and Kaplinsky, R. (eds) (2001) The value of value chains: spreading the gains

from globalisation. Special issue of the IDS Bulletin, Vol. 32, No. 3. Brighton: University of

Sussex.

Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., Sturgeon, T. (2005) The governance of global value chains. Review of

International Political Economy, 12(1): 78–104.

Gertler, M. (2003) Tacit knowledge and the economic geography of context, or the undefinable

tacitness of being (there). Journal of Economic Geography, 3: 75–99.

Gibbon, P. (2003) Value-chain governance, public regulation and entry barriers in the

global fresh fruit and vegetable chain into the EU. Development Policy Review, 21(5–6):

615–625.

Gibbon, P. and Ponte, S. (2005) Trading Down: Africa, Value Chains, and the Global Economy.

Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Glu

¨

ckler, J. (2007) Economic geography and the evolution of networks. Journal of Economic

Geography, 7(5): 619–634.

Granovetter, M. (1985) Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness.

American Journal of Sociology, 91: 481–510.