Berklee College of Music Berklee College of Music

Research Media and Information Exchange Research Media and Information Exchange

ABLE Articles ABLE Resource Center Formats

2014

Statewide Assessment of Professional Development Needs Statewide Assessment of Professional Development Needs

Related to Educating Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder Related to Educating Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder

Matthew E. Brock

Heartley B. Hubbard

Erik W. Carter

A. Pablo Juarez

Zachary E. Warren

Follow this and additional works at: https://remix.berklee.edu/able-articles

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Brock, M. E., Hubbard, H. B., Carter, E. W., Juarez, A. P., & Warren, Z. E. (2014). Statewide Assessment of

Professional Development Needs Related to Educating Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Retrieved from https://remix.berklee.edu/able-articles/73

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the ABLE Resource Center Formats at Research Media

and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in ABLE Articles by an authorized administrator of

Research Media and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected].

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273939696

Statewide Assessment of Professional Development Needs Related to

Educating Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder

ArticleinFocus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities · May 2014

DOI: 10.1177/1088357614522290

CITATIONS

27

READS

102

5 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Putting Faith to Work View project

Optimizing Health and Well-Being in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders View project

Matthew Brock

The Ohio State University

37 PUBLICATIONS800 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Heartley Huber

Vanderbilt University

12 PUBLICATIONS135 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Erik Carter

Vanderbilt University

164 PUBLICATIONS3,204 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Matthew Brock on 20 December 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Focus on Autism and Other

Developmental Disabilities

2014, Vol. 29(2) 67 –79

© Hammill Institute on Disabilities 2014

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1088357614522290

focus.sagepub.com

Article

Over the past two decades, the field of special education has

encountered two important trends: the increasing presence

of students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in schools

and the proliferation of research focused on meeting the

multifaceted needs of this group of students. The estimated

prevalence of ASD increased 78% between 2002 and 2012

and as many as 1 in 88 children have now been diagnosed

with ASD (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

2012). The more than 400,000 students with ASD who are

currently enrolled in schools in the United States possess a

wide range of social, academic, behavioral, and other needs.

Meeting the diverse instructional and support needs of this

growing population of students presents unique challenges

for educators.

To identify instructional practices and educational sup-

ports effective for this growing number of students with

ASD, many systematic reviews of the intervention literature

have been completed. Although most of these reviews have

focused on individual interventions or specific educational

domains (e.g., Hendricks & Wehman, 2009; Pennington &

Delano, 2012), two broader efforts have served to map the

range of educational practices currently considered to have

compelling research support. In 2009, the National Autism

Center published a review of 775 research articles in which

they identified 11 established treatments and 22 emerging

treatments for use with students with ASD. More recently,

Odom, Collet-Klingenberg, Rogers, and Hatton (2010) con-

ducted a systematic review of the literature and identified 24

evidence-based practices or strategies practitioners could

use to teach specific educational targets (e.g., skills and con-

cepts) to students with ASD. Collectively, these reviews pro-

vide the field with important guidance on the array of

research-based practices that hold particular promise for use

with students with ASD.

Despite growing understanding in the field about which

educational practices may be effective for students, the in-

and post-school outcomes for students with ASD continue

to be less than optimal. Descriptive studies indicate large

numbers of children and youth with ASD struggle in areas

such as academic performance, social relationships, com-

munication, challenging behavior, and self-determination

(e.g., Carter et al., 2013; Sanford, Levine, & Blackorby,

522290FOA

XXX10.1177/1088357614522290Focus on Autism and Other Developmental DisabilitiesBrock et al.

research-article2014

1

Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA

Corresponding Author:

Matthew E. Brock, Department of Special Education, Vanderbilt

University, 230 Appleton Place, PMB 228, Nashville, TN 37203, USA.

Email: [email protected]

Statewide Assessment of Professional

Development Needs Related to Educating

Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder

Matthew E. Brock, MA

1

, Heartley B. Huber, MEd

1

, Erik W. Carter, PhD

1

,

A. Pablo Juarez, MEd

1

, and Zachary E. Warren, PhD

1

Abstract

Preparing teachers to implement evidence-based practices for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a pressing

need. We surveyed 456 teachers and administrators in a southern state about professional development related to

educating students with ASD. Specifically, we were interested in confidence in implementation of evidence-based practices,

interest in accessing training on these topics, perceived benefit of different avenues of professional development, and

interest in accessing these avenues. Overall, teachers were not very confident in their ability to implement evidence-

based practices and address important issues for students with ASD. Surprisingly, lower confidence was not related to

increased interest in training. In addition, teachers and administrators perceived workshops to be a more beneficial and

attractive avenue of professional development compared with coaching, despite empirical evidence to the contrary. We

offer possible explanations for these findings and share implications for administrators, technical assistance providers, and

policy makers who make decisions about professional development opportunities.

Keywords

professional development, training needs, training methods, autism spectrum disorder

68 Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 29(2)

2008). Longitudinal and follow-up studies further suggest

many young adults with ASD are leaving school without the

skills they need for adulthood. For example, relatively small

percentages of young people with ASD are employed,

attend college, or live independently in the early years after

leaving high school (Shattuck et al., 2012; Wagner,

Newman, Cameto, Garza, & Levine, 2005).

One factor that may contribute to these outcomes is the

extent to which practices known to be effective for students

with ASD are actually implemented in schools. The field’s

expanding efforts to identify evidence-based educational

practices do not, by themselves, ensure educators are pre-

pared to accurately implement these practices. Indeed, the

enduring gap between research and practice continues to be

highlighted in the literature (e.g., Cook & Odom, 2013).

Unfortunately, evidence suggests prevailing approaches

for training and professional development may be insuffi-

cient for preparing practitioners to implement evidence-

based practices for students with ASD. Many teachers leave

their pre-service training poorly prepared to meet the com-

plex needs of students with ASD. In their survey of practic-

ing teachers, Morrier, Hess, and Heflin (2011) found that

most educators reported not having received instruction on

evidence-based practices for students with ASD during

their pre-service preparation. Although increasing numbers

of teacher preparation programs now offer coursework

related to students with ASD, the quality of these efforts and

the extent to which classes address evidence-based prac-

tices appear to be quite variable (Barnhill, Polloway, &

Sumutka, 2011; Barnhill, Sumutka, Polloway, & Lee,

2013). Widely used professional development approaches

may also have limited impact on the capacity of practicing

teachers to implement evidence-based practices for students

with ASD. For example, one of the most common avenues

of professional development—stand-alone workshops

without follow-up training and support—has been shown to

have limited impact on improving accurate implementation

of evidence-based practice (e.g., Hall, Grundon, Pope, &

Romero, 2010; Smith, Parker, Taubman, & Lovaas, 1992).

However, more effective models of professional develop-

ment (e.g., individualized coaching and mentoring; Kretlow

& Bartholomew, 2010) are not used widely in schools

(Russo, 2004). Given the shortcomings of pre-service and

in-service teacher training, it remains unclear how well pre-

pared teachers feel they are to implement evidence-based

practices for students with ASD.

To date, relatively little research has focused on the

training needs of teachers responsible for educating stu-

dents with ASD. In her study of 498 special educators,

Hendricks (2011) found that teachers reported very modest

levels of knowledge and implementation of skill competen-

cies (e.g., characteristics of autism, social skills, behavior,

etc.) related to ASD. Morrier and colleagues (2011) sur-

veyed 90 teachers of students with ASD and found that

neither past training experiences nor teacher characteristics

predicted self-reported use of assorted teaching strategies

(e.g., social stories, cognitive behavioral modification,

auditory integration training, etc.) for students with ASD. In

addition, results indicated that less than 5% of teachers sur-

veyed used evidence-based practices in their classrooms.

Additional survey studies have explored the types of inter-

ventions and treatments used by teachers (Hess, Morrier,

Heflin, & Ivey, 2008), attitudes of teachers toward inclusion

(Hart & Malian, 2013), and perspectives on teacher prepa-

ration and professional development programs as well as

ASD-related topics (Segall & Campbell, 2012).

Collectively, these initial survey studies indicate profes-

sional development needs may be both substantial and

highly variable across practitioners who educate students

with ASD. However, several important questions about the

focus and format of professional development related to

educating students with ASD remain unanswered. First,

prior studies have not examined the professional develop-

ment needs of educators in relation to those focused inter-

vention practices identified as evidence-based for students

with ASD (Odom et al., 2010). Knowing the extent to which

educators feel confident implementing each of these

practices—as well as their interest in receiving additional

training—could inform the work of districts, state agencies,

and other entities charged with designing professional

development for teachers. Adopting a more data-driven

approach for discerning the training needs of educators

could increase the relevance of training opportunities in a

particular district or state.

Second, it is unclear whether different professionals

working within schools share similar or divergent views

about which training topics should be prioritized for educa-

tors who work with students with ASD. School- and

district-level administrators typically play a prominent role

in determining which educational interventions and strate-

gies receive primary attention within ongoing professional

development. The extent to which the training priorities of

administrators and educators align has not been examined.

Third, little is known about the factors that may influ-

ence teachers’ desire for additional training on evidence-

based practices. The confidence teachers possess related to

implementing specific practices may be one salient factor.

For example, a teacher who already feels certain of her abil-

ity to effectively implement time delay procedures may be

less likely to seek out additional training on this practice.

The specific roles staff members assume within their

schools may be another influence on professional develop-

ment preferences. For example, a general education teacher

who has students with ASD enrolled in his classroom may

be more interested in professional development on inclu-

sive practices than a special educator working within a self-

contained setting. In addition, the educational experiences

of teachers may also impact their desire for additional

Brock et al. 69

training. For example, prior access to related trainings, or

extensive experience working with students with ASD may

influence interest in further professional development.

Fourth, the avenues through which professional devel-

opment is offered is as important to consider as the content

addressed within those trainings. Although certain training

avenues (e.g., one-to-one coaching) have more research

support than others (e.g., “one-shot” workshops), it is

unclear whether these avenues are viewed by practitioners

as either beneficial or ones they would be likely to access.

Preferences regarding professional development avenues

may be further influenced by the format, length, and scope

of the training, as well as the ease with which trainings can

be accessed. For example, the availability of certain types

of training may be more limited in rural areas. Furthermore,

the needs of educators in rural areas and the ability of

administrators in those rural areas to respond to educator

needs may vary significantly due to availability of resources.

Purpose and Research Hypotheses

The purpose of this project was to examine the perspectives

of a statewide sample of teachers and administrators on the

professional development needs of staff working with stu-

dents with ASD. Specifically, we explored four related

aspects of professional development for teachers. First, we

asked teachers and administrators about (a) their (or their

staff’s) confidence implementing evidence-based practices

for students with ASD and (b) their desire for additional

training related to these topics. We hypothesized teachers

and administrators would be most interested in training

focused on those practices for which teachers expressed the

lowest levels of implementation confidence. Second, we

examined whether teacher role (i.e., general educator vs.

special educator) and years of experience were associated

with confidence in implementation and desire to access

training related to evidence-based practices for students

with ASD. We anticipated special educators, whose initial

training and daily responsibilities may be more directly

related to educating students with ASD, would report

greater confidence, and desire more training in implement-

ing and addressing ASD-related training topics compared

with general educators. In addition, we predicted teachers

with more experience would express more confidence

related to practice implementation and would thus be less

interested in professional development.

Third, we queried teachers and administrators about the

potential benefits of different avenues of professional

development and the likelihood teachers would access these

various training possibilities. Expecting administrators and

teachers would desire high-quality training, we hypothe-

sized that the avenues each rated as most beneficial would

be the same avenues that each said would most likely be

accessed. Fourth, we were interested in whether interest in

different avenues of professional development would differ

by geographic region. Because centralized trainings often

require disproportionately more travel for teachers in rural

areas, we anticipated these teachers might be more inter-

ested in online or in-district avenues of training requiring

little or no travel.

Method

Participants and Recruitment

We sought to recruit a representative sample of teachers,

special education supervisors, and school administrators

working with students with ASD in the state of Tennessee.

Using a comprehensive list of school principals in the state

and a Department of Education database of all school-based

special education supervisors, we e-mailed a survey descrip-

tion and electronic survey link to everyone on these two

lists. We indicated the purpose of the survey was to gather

input from teachers, administrators, and related service pro-

viders so The Treatment and Research Institute for Autism

Spectrum Disorders (TRIAD), a state-funded autism tech-

nical assistance provider, could more closely align their

support with the needs identified by practitioners. We

invited principals to complete the survey themselves as well

as to forward the link to teachers and related service provid-

ers who work with students with ASD. Similarly, we asked

special education supervisors to complete the survey and to

forward it to other district- or school-level personnel who

work with students with ASD. Our initial dissemination of

survey information resulted in 1,577 successful emails (200

emails were returned as undeliverable). A follow-up email

was sent to the same list of potential respondents approxi-

mately 3 weeks later. We provided no financial incentives

for participation.

Our sample included 456 participants who completed

the survey and identified themselves as teachers or admin-

istrators, including 241 special education teachers, 33 gen-

eral education teachers, 126 school administrators (e.g.,

principal, assistant principal), 10 school-level special edu-

cation supervisors, and 36 district-level special education

administrators responsible for overseeing services for stu-

dents with ASD. Demographics for each group are dis-

played in Table 1. We aggregated these respondents into

two groups: teachers (n = 274) and administrators (n = 172).

We excluded from this analysis related service providers

and paraprofessionals who responded to the survey.

Teachers. On average, teachers reported having 8.7 (SD =

7.6) years of experience in their current position, 15.4 (SD =

9.8) years of total experience in the field of education, and

10.0 (SD = 7.7) years of experience working with students

with ASD. Teachers had an average of 2.8 (SD = 2.6) stu-

dents with ASD on their current caseload. In terms of

70 Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 29(2)

school level, 13.6% primarily served preschool students,

49.3% elementary students, 23.0% middle school students,

13.5% high school students, and 1.1% served students

across multiple levels. Most teachers (58.4%) held a mas-

ter’s degree as their highest level of education, while 39.8%

held a bachelor’s degree and 1.8% held a doctoral degree.

On average, they reported having attended 3.9 (SD = 1.4)

total hours of professional development over the past year.

More than one third (37.4%) reported having attended a

training by the state’s ASD technical assistance provider in

the past year.

Administrators. On average, administrators had 7.7 (SD =

6.6) years of experience in their current position, 24.6 (SD =

9.2) years of total experience in the field of education, and

14.9 (SD = 8.7) years of experience working with students

with ASD. In terms of school level, 4.1% primarily served

preschool students, 54.4% elementary students, 12.2% mid-

dle school students, 8.7% high school students, and 18.6%

served students across multiple levels. The highest level of

education for 78.5% of administrators was a master’s

degree, while 1.2% held a bachelor’s degree and 20.3%

held a doctoral degree.

Schools. Teachers and administrators came from 89 public

school districts and one private school, representing 65% of

all districts in the state. These school districts were diverse

in size, with 7 serving fewer than 1,000 students; 46 serving

1,000 to 2,000 students; 18 serving 5,000 to 10,000 stu-

dents; 15 serving 10,000 to 50,000 students; and 3 districts

serving more than 50,000 students. Student demographics

also were diverse across these districts. The percentage of

students identified as European American ranged from

7.3% to 99.3% (M = 81.7%; SD = 18.0% across schools). In

4 districts, the majority of students were African American.

The percentage of students qualifying for free and reduced-

price meals ranged from 12.4% to 85.1% (M = 60.6%; SD =

11.7%); in 86.5% of these districts, more than half of stu-

dents were economically disadvantaged. The percentage of

students with disabilities ranged from 9.8% to 25.0% across

districts (M = 15.8%; SD = 3.0%). Based on metro-centric

locale codes assigned by the National Center for Education

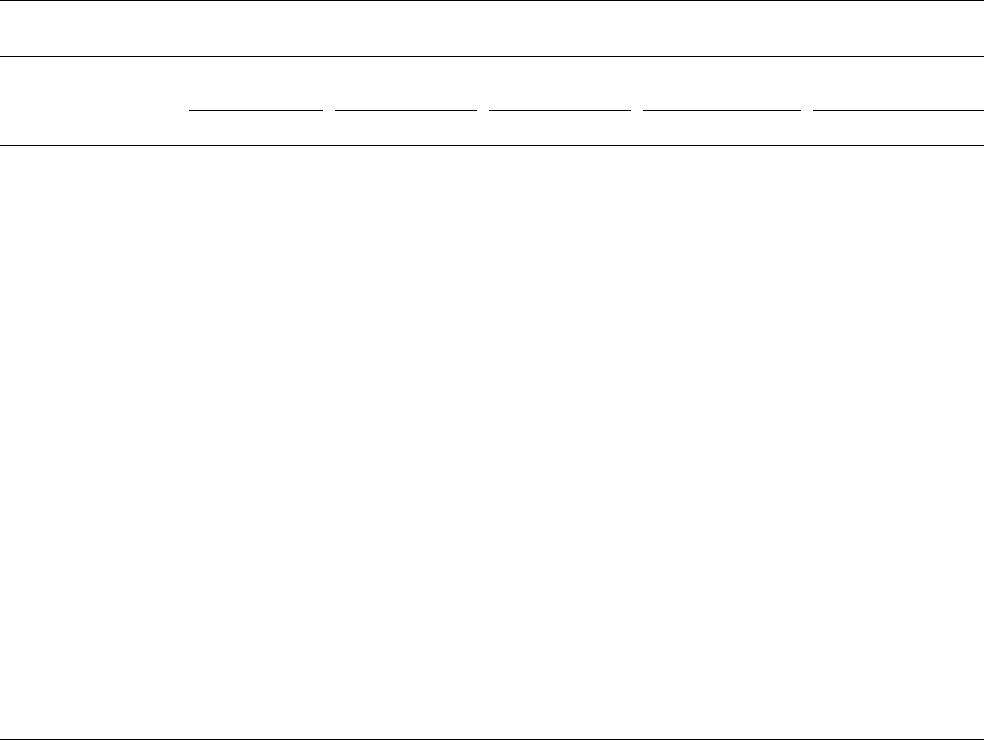

Table 1. Respondent Demographics by Stakeholder Group.

Special education

teacher (n = 241)

General education

teacher (n = 33)

School administrator

(n = 126)

School-level special ed.

supervisor (n = 10)

District-level special ed.

administrator (n = 36)

M SD % M SD % M SD % M SD % M SD %

Years of experience

In current position 8.79 7.74 7.73 6.43 7.16 6.10 8.50 8.92 9.56 7.18

In field of education 15.45 9.99 4.85 8.70 23.81 9.13 26.80 8.04 26.92 9.58

Working with students

with ASD

10.63 7.65 5.03 6.62 13.11 7.87 21.00 9.83 19.28 8.83

Students with ASD on

current caseload

3.90 1.36 3.61 1.54 NA NA NA NA NA NA

Professional development

hours in past year

2.97 2.67 1.67 2.09 NA NA NA NA NA NA

Level of students with ASD served

Pre-K 14.1 6.1 4.0 10.0 2.8

Elementary 48.5 54.5 70.6 40.0 11.1

Middle 21.2 36.4 13.5 10.0 8.3

High 14.9 3.0 11.9 0.0 0.0

Across levels 1.2 0.0 0.0 40.0 77.8

Highest level of education

Bachelor’s degree 40.7 33.3 0.0 20.0 0.0

Master’s degree 57.7 63.6 79.4 70.0 77.8

Doctoral degree 1.7 3.0 20.6 10.0 22.2

School district locale

a

Urban 14.5 12.2 26.4 11.1 22.2

Urban fringe 54.3 39.4 32.8 33.3 19.5

Town 5.4 24.2 8.8 22.2 11.1

Rural 25.7 24.3 32.0 33.3 47.2

Attended state-funded training provided by TRIAD in past year

Yes 23.7 6.1 NA NA NA

No 70.1 90.9 NA NA NA

Not sure 6.2 3.0 NA NA NA

Note. NA = not applicable; TRIAD = Treatment and Research Institute for Autism Spectrum Disorders, a state-funded technical assistance provider.

a

Based on metro-centric locale codes assigned by the National Center for Education Statistics (Institute of Educational Sciences, 2012).

Brock et al. 71

Statistics (Institute of Educational Sciences, 2012), respon-

dents came from a diversity of geographic regions that gen-

erally mirrored the distribution of teachers working in these

regions. Specifically, 18.2% of respondents worked in dis-

tricts in urban areas (vs. 31.2% of educators statewide),

43.9% worked in districts in urban fringes (vs. 24.8%),

8.6% worked in districts located in towns (vs. 10.9%), and

29.2% worked in districts in rural areas (vs. 33.2%).

Survey Instrument

Teachers and administrators were asked to complete a 129-

item web-based survey using the REDCap platform (Harris

et al., 2009). The survey included four major topics: (a)

respondent demographics, (b) confidence implementing

evidence-based practices and related topics, (c) desire for

training on these practices, and (d) views on professional

development avenues related to identified training needs.

Although we designed two separate versions of the survey

for teachers and administrators, questions on each version

mirrored the other and wording differences are noted below.

Confidence implementing practices. We presented respon-

dents with 36 different evidence-based practices and train-

ing topics related to educating students with ASD (see

Table 2 for a complete list). The first 24 items were

evidence-based intervention practices for students with ASD,

as identified by the National Professional Development Cen-

ter on Autism Spectrum Disorders (Odom et al., 2010). Each

of these interventions was accompanied by a brief, one- to

two-sentence description to ensure respondents held a com-

mon understanding of what each meant. For example, “Task

analysis” included the description, “The process of breaking

a skill into smaller, more manageable steps in order to teach

the skill.” The remaining 12 items were additional topics fre-

quently addressed as part of professional development

efforts. For each item, we asked teachers to rate their level of

confidence implementing or addressing each topic for stu-

dents with ASD. Administrators rated their confidence in

how well their staff implements or addresses each topic for

students with ASD. Teacher and administrators rated each

item using a 5-point, Likert-type scale (1 = not at all confi-

dent, 2 = a little confident, 3 = somewhat confident, 4 = quite

confident, 5 = very confident).

Desire for training. We were also interested in gauging the

extent to which training was desired in relation to each of

these 36 topics. We asked teachers how interested they were

in participating in training on each topic. Similarly, we

asked administrators how interested they were in having

their staff participate in training. Both respondents rated

each item using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all

interested, 2 = a little interested, 3 = somewhat interested,

4 = quite interested, 5 = very interested). In addition, we

asked respondents to identify the top three items for which

they most desired training for themselves (teachers) or their

staff (administrators). Only three could be selected, and an

option for “other topics” was offered.

Professional development avenues. We were interested in learn-

ing how school staff viewed each of 11 different avenues of

professional development (see Table 3). These avenues were

drawn from our review of the common avenues described in

the literature (e.g., Garet, Porter, Desimone, Birman, & Yoon,

2001; Penuel, Fishman, Yamaguchi, & Gallagher, 2007).

First, we asked teachers to indicate how likely each avenue of

training would be to benefit them; administrators were asked

the extent to which each avenue would benefit their staff.

Ratings were provided on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not

at all, 2 = a little, 3 = somewhat likely, 4 = quite likely, 5 =

very likely). Second, we asked teachers how likely they

would be to access each avenue of training (assuming its

availability) in the current year. We asked administrators to

provide ratings in reference to their staff. Ratings were pro-

vided on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little,

3 = somewhat likely, 4 = quite likely, 5 = very likely).

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics (i.e., means, standard devia-

tions) to summarize all teacher and administrator ratings.

To summarize overall perspectives on evidence-based prac-

tice, we calculated average ratings of overall confidence

and overall training interest across only the 24 evidence-

based practices. We used Pearson’s product–moment cor-

relations to quantify relations among (a) ratings of

confidence and training interest, (b) perceived benefits of

and interest in various professional development avenues,

(c) educational experience and overall training interest, and

(d) geographic locale code and interest in professional

development avenues. To gauge alignment among partici-

pants’ perspectives, we used one-way ANOVA to compare

ratings between teachers and administrators.

Results

Confidence Implementing Evidence-Based and

Related Topics

Overall, teachers expressed only moderate levels of confi-

dence implementing the 24 evidence-based practices (over-

all M = 3.07; individual item means ranged from 2.12-3.54;

see Table 2). The evidence-based practices for which the

highest percentage of teachers said they had no or little con-

fidence implementing were pivotal response training

(64.2%), speech-generating devices (64.2%), parent-

implemented intervention (51.8%), time delay (51.8%), and

peer-mediated interventions (51.5%). The percentage of

72 Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 29(2)

Table 2. Teacher and Administrator Ratings of Interest in Training and Confidence in Teachers Addressing Training Topics.

Teacher ratings (n = 274) Administrator ratings (n = 172)

ANOVA of teacher/

administrator ratings

Interest in

training

Confidence

r

Interest in

training

Confidence

r

Interest in

training

Confidence

Items M SD M SD M SD M SD F(1, 444) F(1, 444)

Evidence-based practices

a

Computer-aided instruction 3.62 1.10 2.81 1.06 .04 3.47 1.09 3.22 1.10 −.13 1.87 14.68**

Functional communication

training

3.57 1.15 2.80 1.11 .06 3.71 0.97 2.93 0.96 −.15* 1.86 1.54

Antecedent-based

interventions

3.55 1.12 3.14 0.99 −.09 3.81 0.89 3.02 0.82 −.16* 6.30* 1.91

Self-management 3.54 1.14 2.71 0.99 .09 3.72 1.02 2.72 1.05 .02 2.80 .00

Differential reinforcement 3.46 1.10 3.07 1.08 .00 3.54 1.02 3.01 1.02 −.06 .60 .36

Task analysis 3.45 1.12 3.41 0.96 −.05 3.60 0.93 3.27 0.91 −.23** 2.32 2.08

Naturalistic interventions 3.43 1.21 2.56 1.11 .10 3.43 1.07 2.56 1.06 .11 .00 .00

Parent-implemented

interventions

3.41 1.22 2.19 1.12 .09 3.55 1.18 2.15 1.09 .10 1.46 .13

Extinction 3.40 1.20 2.77 1.08 .10 3.50 1.01 2.67 1.02 −.01 .80 .87

Pivotal response training 3.39 1.23 2.12 1.05 .09 3.45 1.17 2.21 1.03 .17* .21 .70

Peer-mediated intervention 3.38 1.21 2.51 1.07 .09 3.35 1.20 2.49 1.12 .05 .09 .02

Reinforcement 3.38 1.13 3.54 0.99 −.08 3.71 0.95 3.40 0.85 −.26** 9.86** 2.21

Response interruption/

redirection

3.37 1.20 2.66 1.11 .00 3.44 1.14 2.99 1.06 −.06 .37 9.60**

Social stories 3.36 1.17 3.09 1.08 −.01 3.53 1.10 3.14 1.08 −.14 2.27 .21

Social skills training groups 3.32 1.22 2.74 1.17 .07 3.47 1.17 2.95 1.14 −.16* 2.68 3.68

Functional behavior

assessment

3.31 1.22 3.01 1.14 −.10 3.55 1.16 3.24 1.09 −.28** 4.46* 4.76*

Video modeling 3.30 1.21 2.40 1.12 .06 3.45 1.06 2.03 1.07 .07 1.67 11.73**

Structured work systems 3.24 1.18 2.72 1.15 .04 3.48 1.07 2.70 1.04 .02 4.38* .02

Prompting 3.22 1.19 3.39 1.06 −.06 3.41 1.04 3.19 1.06 −.14 3.21 3.93*

Discrete trial training 3.19 1.26 2.97 1.20 .12* 3.51 1.09 2.86 1.12 −.05 7.13** .88

Time delay 3.03 1.21 2.43 1.16 .06 3.19 1.10 2.44 1.08 .11 2.14 .00

Visual supports 3.00 1.26 3.21 1.18 .06 3.37 1.12 3.28 1.05 −.04 9.48** .42

Speech-generating devices 2.97 1.32 2.19 1.16 .20* 3.05 1.21 2.37 1.23 .04 .39 2.50

Picture exchange

communication system

2.95 1.29 2.91 1.27 .08 3.22 1.20 2.88 1.25 .06 4.76* .05

Average evidence-based

practice rating

3.33 0.93 3.07 1.35 .14* 3.48 0.86 2.82 0.74 −.01 2.98 .04

Other training topics

Inclusive practices 3.57 1.20 2.97 1.08 −.02 3.58 1.10 3.40 1.02 −.24** .00 17.28**

Technological supports/

accommodations

3.47 1.15 2.73 1.00 .02 3.52 1.12 3.06 0.98 −.06 .18 12.00**

Assessment for instructional

programming

3.43 1.20 2.73 1.11 −.01 3.52 1.19 2.97 1.01 −.29** .56 5.18*

Alternate Assessment 3.34 1.25 2.47 1.16 .01 3.37 1.22 3.01 1.11

−.08 .07 23.03**

Special education laws,

regulations, and policies

3.28 1.26 2.89 1.08 −.01 3.40 1.17 3.47 1.04 −.21** 1.02 31.04**

ASD diagnostic methods 3.24 1.31 2.14 1.10 .19** 3.17 1.24 2.82 1.24 −.07 .28 36.44**

Transition planning strategies 3.07 1.35 2.28 1.10 .20** 3.41 1.19 2.85 1.00 .05 9.81** 29.64**

Program evaluation 3.05 1.25 2.31 1.07 .24** 3.38 1.15 2.76 0.97 .06 7.69** 19.84**

Characteristic of ASD 3.01 1.31 3.10 1.17 −.11 3.49 1.12 3.16 1.00 −.15* 15.85** .32

Community-based instruction 2.96 1.34 2.23 1.20 .39** 3.05 1.22 2.38 1.14 .12 .50 1.89

Career development

strategies

2.79 1.39 1.99 1.11 .44** 2.98 1.36 2.19 1.09 .25** 1.91 3.51

Note. r = Pearson’s product−moment correlation.

a

Based on review by Odom, Collet-Klingenberg, Rogers, and Hatton (2010).

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Brock et al. 73

teachers saying they were quite or very confident was high-

est for reinforcement (55.1%), task analysis (49.3%),

prompting (48.5%), visual supports (43.4%), and anteced-

ent-based interventions (37.6%). For other training topics,

teacher ratings reflected the lowest confidence for address-

ing career development and highest confidence related to

the characteristics of students with ASD.

Descriptively, the overall confidence expressed by admin-

istrators in their staff was slightly lower than teachers (over-

all M = 2.82; individual item means ranged from 2.03-3.40;

see Table 2). The evidence-based practices for which the

highest percentage of administrators said they had no or little

confidence their staff could implement well were video mod-

eling (68.0%), parent-implemented interventions (65.1%),

pivotal response training (62.2%), speech-generating devices

(57.0%), and time delay (53.5%). The percentage of adminis-

trators saying they were quite or very confident was highest

for functional behavioral assessment (45.9%), reinforcement

(44.2%), computer-based instruction (44.2%), task analysis

(42.4%), and prompting (41.9%). For other topics, adminis-

trators expressed the lowest confidence in the area of career

development and the highest confidence in addressing spe-

cial education laws, regulations, and policies.

Interest in Professional Development

Overall, interest among teachers in accessing training on

the 24 evidence-based practices was moderate (overall M =

3.33; individual item means ranged from 2.95-3.62; see

Table 2). The interventions for which the highest percent-

age of teachers indicated they were quite or very interested

in participating in training were computer-aided instruction

(58.8%), functional communication training (57.7%),

antecedent-based interventions (56.6%), self-management

(55.8%), and pivotal response training (52.2%). No or little

interest was most often reported for speech-generating

devices (39.8%), Picture Exchange Communication System

(PECS; 38.7%), visual supports (37.6%), time delay

(32.8%), and discrete trial training (29.6%). In terms of

other topics, teachers were most interested in inclusive edu-

cation (55.5% indicated they were quite or very interested)

and least interested in career development (46.0% indicated

no interest or little interest).

Descriptively, overall interest among administrators in

having their staff access training on evidence-based prac-

tices was slightly higher than teachers (overall M = 3.48;

individual item means ranged from 3.05-3.81; see Table 2).

The interventions for which the highest percentage of admin-

istrators indicated they were quite or very interested in hav-

ing their staff receive training were antecedent-based

interventions (65.7%), reinforcement (60.5%), functional

communication training (59.3%), self-management (58.7%),

and task analysis (53.5%). Ratings of no interest or little

interest in staff training were highest for speech-generating

devices (31.4%), PECS (27.3%), time delay (26.7%), peer-

mediated interventions (24.4%), and visual supports

(20.3%). As with teachers, the other topic for which admin-

istrators most wanted staff training was inclusive education

(54.1% indicated they were quite or very interested); the

least interest was related to career development (36.0% indi-

cated no interest or little interest).

When asked to select their top three priorities for train-

ing, the highest percentage of teachers prioritized training

related to self-management (22.3% of teachers ranked in

top three priorities), computer-aided instruction (18.1%),

and social skills groups (15.5%). However, administrators

prioritized training for their staff on functional behavior

assessment (23.6% of administrators ranked in top three

priorities), self-management (23.0%), and response inter-

ruption/redirection (18.6%).

Relations Among Confidence and Training

Interest

For teachers, lower confidence in implementing or address-

ing a topic was never associated with significantly higher

interest in training on that topic (see Table 2). For adminis-

trators, however, lower confidence in their staff was associ-

ated with significantly higher interest in professional

development for 10 of the topics, including 6 evidence-

based practices (i.e., antecedent-based interventions, func-

tional behavior assessment, functional communication

training, reinforcement, social skills training groups, and

task analysis) and four other topics (i.e., characteristics of

ASD, inclusive practices, assessment for instructional pro-

gramming, and special education laws and policies). The

unexpected findings of positive correlations among confi-

dence ratings and training interest may be influenced in part

by the fact that some topics are less relevant in younger

grades, leading respondents to have both low confidence

and low interest in training. For example, 18.4% of middle

and high school teachers were quite or very interested in

career development compared with only 8.2% of preschool

and elementary.

Relations Among Teacher and Administrator

Ratings of Topics

For 24 of the 36 evidence-based practices and training topics,

we found no statistically significant differences between

teachers and administrators’ ratings of confidence. For 2

practices (i.e., prompting, video modeling), teachers’ ratings

of their own confidence were higher than the ratings admin-

istrators expressed for their staff. For the remaining 10 topics

(i.e., computer-aided instruction, functional behavior assess-

ment, response interruption/redirection, alternate assessment,

ASD diagnostic methods, inclusive practices, assessment for

instructional programming, special education laws and

74 Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 29(2)

policies, program evaluation, technological supports/accom-

modations, transition planning strategies), administrator rat-

ings were significantly higher.

Similarly, somewhat few significant differences were

found between teacher and administrator ratings of training

interest. Although teacher ratings never exceeded those of

administrators, administrators had significantly higher rat-

ings for 10 topics (i.e., antecedent-based interventions, dis-

crete trial training, functional behavior assessment, picture

exchange communication system, reinforcement, structured

work systems, visual supports, characteristics of ASD, pro-

gram evaluation, transition planning strategies).

Factors Associated With Teacher Ratings

In terms of overall ratings of evidence-based practices, spe-

cial educators expressed more confidence, r(272) = .27, p <

.001, and more interest in training, r(272) = .22, p < .001,

than did general educators. Although teachers with more

experience in their current positions tended to be less inter-

ested in training on evidence-based practices, r(272) =

−.186, p < .01, they did not have higher ratings of confi-

dence implementing those interventions, r(272) = .04, p =.49.

Benefits of Professional Development Avenues

Overall, teachers reported they were only somewhat likely to

benefit from various professional development avenues

included on the survey (item means ranged from 2.41-3.78;

see Table 3). The avenues of training for which the highest

percentage of teachers indicated they would quite likely or

very likely benefit from accessing were workshops (64.2%),

week-long summer institutes (47.1%), websites (41.6%),

printed materials (40.9%), and state conferences (37.2%). The

training avenues for which the highest percentage of teachers

said they were not at all or only a little likely to benefit from

accessing were on-campus college course (55.1%), national

conferences (47.4%), online college courses (40.5%), study

groups (33.2%), and coaching (32.5%).

Administrator ratings were also modest (item means

ranged from 2.31-3.37). The avenues of training for which

the highest percentage of administrators perceived their

staff would quite likely or very likely benefit from accessing

were workshops (61.6%), coaching (48.8%), summer insti-

tutes (47.7%), webinars (44.2%), and websites (41.9%).

The highest percentage of administrators indicated their

staff were not at all or only a little likely to benefit from

accessing the following training avenues: on-campus col-

lege course (61.0%), national conference (51.7%), online

college course (45.3%), study groups (34.3%), and state

conference (27.3%).

Accessing Professional Development Avenues

Teachers generally reported being only somewhat likely to

access most professional development avenues in the next

year (item means ranged from 1.96-3.46; see Table 3). The

avenues of training for which the highest percentage of

Table 3. Teacher and Administrator Ratings of Training Benefits and Likelihood of Access.

Professional development

avenues

Teacher ratings (n = 274) Administrator ratings (n = 172)

ANOVA of teacher/

administrator ratings

Benefit Access

r

Benefit Access

r

Benefit Access

M SD M SD M SD M SD F(1, 444) F(1, 444)

On campus college course 2.41 1.32 1.96 1.11 .72** 2.31 1.12 1.97 0.92 .64** .61 .01

One-to-one coaching or

mentoring

3.07 1.25 2.89 1.22 .84** 3.45 1.19 3.16 1.16 .78** 9.87** 5.11*

National conference 2.58 1.34 2.17 1.21 .75** 2.42 1.25 2.00 1.14 .69** 1.44 2.21

Online college course 2.81 1.37 2.58 1.34 .82** 2.66 1.17 2.42 1.09 .76** 1.41 1.56

Printed materials (books,

practice guides, etc.)

3.23 1.18 3.32 1.20 .87** 3.19 1.03 3.21 1.09 .78** .15 1.04

State conference 3.02 1.26 2.78 1.27 .86** 3.19 1.09 2.99 1.15 .80** 2.22 3.11

Teacher study groups 2.90 1.12 2.76 1.13 .85** 2.97 1.08 2.77 1.10 .78** .35 .00

Summer institute (week

long)

3.25 1.28 2.98 1.31 .80** 3.40 1.03 3.05 1.11 .70** 1.54 .34

Webinar (web-based

presentation)

3.07 1.21 3.11 1.25 .87** 3.36 1.06 3.36 1.11 .82** 6.70* 4.76*

Website 3.30 1.11 3.38 1.17 .87** 3.35 1.04 3.44 1.11 .84** .22 .26

Workshop 3.78 0.90 3.46 1.07 .71** 3.73 0.89 3.31 1.02 .68** .31 2.21

Note. r = Pearson’s product−moment correlation.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Brock et al. 75

teachers indicated they were quite likely or very likely to

access this year were workshops (51.8%), printed materials

(47.1%), websites (47.1%), summer institutes (39.4%), and

webinars (39.1%). They were not at all likely or only a little

likely to access on-campus college courses (70.8%),

national conferences (65.7%), online college courses

(48.9%), state conferences (40.1%), and coaching (39.4%).

For most avenues, administrators had fairly low expecta-

tions regarding the likelihood their staff would attend train-

ings. The highest percentage of administrators indicated

their staff would be quite or very likely to access websites

(47.7%), webinars (45.3%), workshops (43.0%), printed

materials (41.3%), and coaching (38.4%) in the next year.

They reported their staff were not at all or a little likely to

access on-campus college courses (75.6%), national confer-

ences (69.2%), online college courses (54.7%), study

groups (41.3%), and state conferences (39.0%).

Relations Among Teacher and Administrator

Views of Professional Development

For 9 of the 11 avenues of training, ratings of potential ben-

efit and the likelihood teachers would access an avenue of

training did not differ between teachers and administrators.

Administrator rated one-to-one mentoring or coaching as

more beneficial, F(1, 444) = 9.87; p < .01, and indicated

teachers would be more likely to access this type of training

relative to teacher ratings, F(1, 444) = 5.11; p = .02.

Similarly, administrators rated webinars as more beneficial,

F(1, 444) = 6.70; p = .01, and more likely to be accessed

compared with teachers, F(1, 444) = 4.76; p = .03.

Relationship between perceived benefit and likelihood to

access. For both teachers and administrators, ratings of the

potential benefit were significantly associated with their

interest in every avenue of training, r = .64 to .87; for all

relationships, see Table 3.

Moderators of Teacher Perspectives on Interest

in Training

Geographic region. Relative to teachers from other geo-

graphic regions, teachers and administrators from urban

areas expressed significantly more interest in accessing

national conferences, r(444) = .24, p < .001, online college

courses, r(444) = .15, p = .001, on-campus college courses,

r(444) = .15, p = .001, state conferences, r(444) = .12, p <

.01, and week-long summer institutes r(444) = .11, p < .02.

Descriptively, teachers from urban areas expressed more

interest in all avenues of training relative to the mean,

r(444) = .02 to .24. Teachers from rural areas (combined

rural metropolitan and non-metropolitan census area)

expressed significantly less interest in attending national

conferences, r(444) = .11, p = .02. Descriptively, teachers

from rural areas expressed less interest in most (8 of the 11)

avenues of training, r(444) = −.11 to −.01, with the excep-

tion of state conferences, webinars, and websites.

Discussion

Preparing practitioners to implement evidence-based prac-

tices confidently and effectively requires strategic profes-

sional development. To better understand practitioner

perceptions of professional development needs in the state

of Tennessee, we surveyed 456 administrators and teachers

representing 89 school districts. Specifically, we were inter-

ested in gauging practitioner confidence in implementing

evidence-based practices and addressing related training

topics for school-age children and youth with ASD, deter-

mining their interest in accessing training in these areas,

and identifying the extent to which practitioners would

access various professional development avenues for

receiving this training. To date, relatively little is known

about the preferred focus and format of efforts to prepare

educators to meet the diverse needs of students with ASD.

Several of our findings extend the professional develop-

ment literature in important ways.

First, practitioners were generally not highly confident

in their ability to implement and address many evidence-

based practices and training topics related to students with

ASD. On average, teacher ratings suggested most were only

a little to somewhat confident in their abilities to implement

15 of the 24 evidence-based practices and 10 of the 11 other

training topics. Such findings align with those from a state-

wide survey in Virginia in which special education teachers

self-reported low to intermediate knowledge of skill com-

petencies related to educating students with ASD

(Hendricks, 2011). Low ratings of confidence may stem

from limited opportunities to acquire information about the

implementation of evidence-based practices (Odom, Cox,

Brock, & National Professional Development Center,

2013). In the present study, most teachers had not recently

accessed ASD-related professional development from the

statewide technical assistance center.

Given these findings, modest interest among respon-

dents in accessing additional professional development was

surprising. On average, fewer than half of all teachers in

this study indicated they were quite or very interested in

accessing professional development related to these evi-

dence-based practices. Contrary to our expectations, teach-

ers who expressed less confidence in implementing a

particular evidence-based practice did not express more

interest in professional development related to the practice.

Such findings may be attributable in part to how practitio-

ners think about educational interventions. Cook, Cook,

and Landrum (2013) suggested that for many practitioners,

evidence from scientific research alone might not be a com-

pelling reason to adopt and implement a particular practice.

76 Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 29(2)

For example, findings from teacher focus groups conducted

by Stahmer, Collings, and Palinkas (2005) revealed that

many practitioners do not have a clear understanding of

what makes a practice evidence-based. Instead, teachers

might weigh other factors more heavily in their decisions

about which practices to implement, including the feasibil-

ity of the practice (Cook, Tankersley, Cook, & Landrum,

2008), the ease with which the practice can be adapted to fit

within ongoing classroom routines (Klingner, Boardman, &

McMaster, 2013), and/or whether other teachers endorse

the practice and attribute implementation to positive out-

comes for students (Cook et al., 2013). Alternatively, some

descriptive studies suggest that when educators have low

views of their own self-efficacy, they may actually be less

enthusiastic about pursuing professional development, as

they do not envision additional training as a path to more

effective teaching (Han & Weiss, 2005; Stein & Wang,

1988). Another possible explanation is that teachers con-

sider some interventions to be more useful and important

than others. In a survey of teachers, practitioners, and

administrators, Callahan, Hughes, and Ma (2013) found

that ratings of social validity varied widely across these 24

evidence-based practices. In addition, it is possible that

teachers have sought, and continue to seek, professional

development about specific practices they believe are more

relevant to their work. They may already feel most confi-

dent about implementing these specific practices, but still

desire additional training. It is likely a combination of these

factors—along with others not measured in this study—

might coalesce to explain the patterns of teacher interest in

professional development reflected in this study.

Second, we found key differences in the ratings of teach-

ers and administrators that may suggest they hold different

priorities for training topics. For nearly all of the topics on

our survey (i.e., 32 of 35 topics), administrators expressed

higher levels of interest in their staff accessing training than

reflected in the ratings of teachers themselves. In particular,

administrators in this survey tended to prioritize evidence-

based practices used to address problem behaviors, such as

functional behavioral assessment and response interruption/

redirection. This interest in strategies to address challenging

behavior may stem from the nature of administrator roles,

which often include responding to and managing crises

related to severe behavior problems. In contrast, teachers

tended to prioritize instructional practices for targeting

functional skills, such as computer-aided instruction or

social skill groups.

Third, we found that interest among practitioners in

ASD-related training was different for general and special

education teachers and was associated with years of experi-

ence. As expected, special educators reported greater confi-

dence in their ability to implement evidence-based practices

and were more interested in professional development

related to autism compared with general educators. This is

not surprising, as the work of special educators focuses cen-

trally on students with disabilities and general educators

have many other competing priorities for professional

development beyond disability-specific instructional inter-

ventions. However, a survey from another state found that

similar numbers of general educators and special educators

self-reported implementing evidence-based practices for

students with ASD (Morrier et al., 2011). Taken together,

available research suggests that although general and spe-

cial educators are both taking steps to implement evidence-

based practices for students with ASD, special educators are

more confident in their implementation and consider pro-

fessional development related to ASD to be a higher priority

than general educators.

As we expected, educators with more experience teach-

ing students with ASD were less interested in professional

development. Contrary to our hypothesis, teachers with

more experience did not report greater confidence in their

ability to implement evidence-based practices. This finding

is similar to that of Ruble, Usher, and McGrew (2011) who

found that teachers of students with ASD with more years

of experience did not report higher levels of self-efficacy.

Factors other than teacher confidence must explain why

more experienced teachers are less interested in profes-

sional development. One possibility is that particular school

districts may tend to offer the same kinds of professional

development opportunities over time. Experienced teachers

may quickly exhaust opportunities to access new training

topics and eventually perceive professional development to

be a less productive use of their time.

Fourth, the views of teachers and administrators regard-

ing the relative benefits of various avenues of professional

development were not aligned with evidence from the

research literature. Specifically, both groups of respondents

perceived workshops to be markedly more beneficial than

one-to-one coaching or a college course. Yet, a number of

experimental studies indicate single-event training work-

shops have a very limited impact on practitioner behavior

(e.g., Brock & Carter, 2013; Hall et al., 2010; Smith et al.,

1992). This disconnect may stem in part from the paucity of

high-quality professional development avenues accessible

to most school staff. Teachers report that workshops are the

most readily available venue to access information about

evidence-based practices for students with ASD (Morrier

et al., 2011). Although one-to-one coaching has been shown

to improve the instructional capacity of educators and out-

comes for students with ASD (e.g., Howlin, Gordon, Pasco,

Wade, & Charman, 2007; Odom et al., 2013), this quality

and intensity of professional development is rarely avail-

able to most practitioners. Similarly, high-quality college

courses in instructional strategies for students with ASD are

both scarce and expensive. Less than 15% of teachers report

receiving training to implement evidence-based practices

for students with ASD from a teacher preparation program

Brock et al. 77

or college coursework (Morrier et al., 2011). Even universi-

ties offering ASD-specific training may not emphasize

implementation of evidence-based practice. Less than one

fourth (21.2%) of universities offering ASD-specific train-

ing spend more than six instructional hours addressing the

24 evidence-based practices identified by the National

Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum

Disorders (Barnhill et al., 2013). Training is sometimes lim-

ited to a single-class session or assigned reading, and is not

directly linked to hands-on experiences with students with

ASD (Barnhill et al., 2011). The few practitioners who actu-

ally experience high-quality hands-on training with one-to-

one coaching perceive one-to-one coaching as being more

effective than stand-alone workshops (Brock & Carter,

2013; Odom et al., 2013). Without actual exposure to these

professional development avenues, teachers and adminis-

trators are unlikely to be convinced that these more expen-

sive and time-consuming options are better alternatives to

workshops. Indeed, our findings indicate teachers are most

likely to continue accessing the avenues of professional

development they already perceive to be the most beneficial

based on past experience.

Fifth, geographic region was associated with teacher

interest in different avenues of professional development,

but in a somewhat different way than we anticipated. As

expected, teachers from rural areas were less interested in

avenues of training requiring them to travel long distances

(e.g., on-campus college course; national conference), but

they were also less interested in avenues of training that

required little or no travel (e.g., online college course;

printed materials) relative to teachers from other geographic

regions. Although the underlying reasons for these differ-

ences are unclear, it is apparent that interest in different

avenues of professional development can be varied within

even a single state. For technical assistance providers and

other entities charged with providing professional develop-

ment in states serving geographically diverse communities,

it may be instructive to reflect on whether and how profes-

sional development opportunities may need to be adapted to

meet varied preferences.

Implications for Practice

Findings from this study have implications for administra-

tors, universities, technical assistance providers, and policy

makers who make decisions about the design and delivery

of professional development related to educating students

with ASD. First, professional development related to serv-

ing students with ASD is sorely needed. Although such a

statement could perhaps be made about serving many other

subgroups of students, the relatively low confidence among

teachers for implementing and addressing evidence-based

practices and related topics coupled with the rise in num-

bers of students with ASD served in schools makes this a

particularly pressing area of need. Second, consideration of

ASD-related training needs should occur at the local level.

Our findings suggest professional development needs and

interests may not be uniform across a state. In light of the

high variability we found across teachers, it is prudent to

ask teachers within a particular school or district how they

view their own instructional capacities and which different

professional development opportunities they would most

highly prioritize.

Third, teachers and administrators should carefully

examine professional development priorities by consider-

ing (a) current skill levels of practitioners and (b) how dif-

ferent evidence-based practices might help meet the needs

of specific students. Our survey findings suggest the profes-

sional development interests of teachers may be unrelated

to how they perceive their own confidence in implementing

evidence-based practice and addressing related training top-

ics. Therefore, it remains unclear exactly what factors they

consider when prioritizing professional development top-

ics. Also, administrators may be more likely to focus on

practices that address problem behavior even though teach-

ers are more interested in everyday instructional strategies

to target functional skills. Professional development topics

should not be selected based on personal preference, but

rather should be strategically chosen to enhance practitioner

skills and improve student outcomes. However, it may be

appropriate to consider teacher preference in some cases.

Johnson and colleagues (2013) found that allowing teachers

to choose between training topics, even when the choices

are limited to two evidence-based interventions that address

the same student outcome, may contribute to faster adop-

tion of the practice and higher quality of implementation.

Fourth, both administrators and teachers should learn

about high-quality alternatives to single-event training

workshops. One-to-one coaching and mentoring is a prom-

ising professional development practice that has been

shown to improve teaching and student outcomes (Wilson,

Dykstra, Watson, Boyd, & Crais, 2012). Development and

evaluation of other innovative approaches are also needed

to expand the repertoire of available professional develop-

ment pathways.

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations to this study raise possibilities for future

research. First, our statewide professional development

needs assessment drew only on the perceptions of practitio-

ners and administrators, which may or may not align well

with more objective measures of training needs. Future

studies should incorporate observational data to document

how well teachers actually implement these practices in the

classroom and how such practices impact student outcomes.

Second, while our survey captured a diverse sample of

teachers and administrators across the state of Tennessee,

78 Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 29(2)

we did not obtain a random sample. Third, although we

obtained data from both administrators and teachers across

the state, we were not able to align the ratings of administra-

tors with those of teachers who worked in the same school

or district. Exploring the alignment of administrator and

teacher views on professional development needs would be

enhanced by directly comparing responses from the same

school teams. Fourth, our intention was not to collect

nationally representative data, but rather to identify training

needs specific to the state of Tennessee. Although we rec-

ommend other states draw on these findings as they seek to

pinpoint their own professional development priorities, we

also stress the importance of replicating these findings in

their own state.

Conclusion

Professional development on evidence-based practice for

students with ASD is a critical need. This study highlights a

concerning gap between research and practice. Although

practitioners indicate they are not very confident imple-

menting evidence-based practices, their interest in pursuing

professional development related to these strategies is

underwhelming. Furthermore, practitioners perceive stand-

alone training workshops as the most effective avenue of

professional development, despite mounting empirical evi-

dence to the contrary. Needs assessments are only a first

step in understanding practitioner views on these issues.

Leaders in special education must take additional steps to

educate practitioners about evidence-based practice and

provide high-quality avenues of professional development

that have the potential to improve educational outcomes for

students with ASD.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with

respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this

article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support

with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this

article: Partial support for this research was provided by a grant

from the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational

Research grant support (UL1 TR000445) from NCATS/NIH. The

Treatment and Research Institute for Autism Spectrum Disorders

(TRIAD) is supported in part by grants from the Tennessee

Department of Education.

References

Barnhill, G. P., Polloway, E. A., & Sumutka, B. M. (2011). A

survey of personnel preparation practices in autism spec-

trum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental

Disabilities, 26, 75–86. doi:10.1177/1088357610378292

Barnhill, G. P., Sumutka, B., Polloway, E. A., & Lee, E. (2013).

Personnel preparation practices in ASD: A follow-up analy-

sis of contemporary practices. Focus on Autism and Other

Developmental Disabilities. Advanced online publication.

doi:10.1177/1088357612475294

Brock, M. E., & Carter, E. W. (2013). Effects of a professional

development package to prepare special education para-

professionals to implement evidence-based practice. The

Journal of Special Education. Advance online publication.

doi:10.1177/0022466913501882

Callahan, K., Hughes, H. L., & Ma, P. S. (2013, May). ABA,

TEACCH, and the social and empirical validation of

evidence-based practices for students with ASDs: Research-

supported interventions for schools, homes, & clinics. Poster

presented at International Meeting for Autism Research, San

Sebastian, Spain.

Carter, E. W., Lane, K. L., Cooney, M., Weir, K., Moss, C. K., &

Machalicek, W. (2013). Parent assessments of self-determina-

tion importance and performance for students with autism or

intellectual disability. American Journal on Intellectual and

Developmental Disabilities, 88, 16–31. doi:10.1352/1944-

7558-118.1.16

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Prevalence

of autism spectrum disorders—Autism and developmen-

tal disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61(3), 1–19.

Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6103.pdf

Cook, B. G., Cook, L., & Landrum, T. J. (2013). Moving research

into practice: Can we make dissemination stick? Exceptional

Children, 79, 163–180.

Cook, B. G., & Odom, S. L. (2013). Evidence-based practices

and implementation science in special education. Exceptional

Children, 79, 135–144.

Cook, B. G., Tankersley, M., Cook, L., & Landrum, T. J. (2008).

Evidence-based special education and professional wisdom:

Putting it all together. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44,

105–111. doi:10.1177/1053451208321452

Garet, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., &

Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes professional develop-

ment effective? Results from a national sample of teach-

ers. American Educational Research Journal, 38, 915–945.

doi:10.3102/00028312038004915

Hall, L. J., Grundon, G. S., Pope, C., & Romero, A. B. (2010).

Training paraprofessionals to use behavioral strategies

when educating learners with autism spectrum disorders

across environments. Behavioral Interventions, 25, 37–51.

doi:10.1002/bin.294

Han, S. S., & Weiss, B. (2005). Sustainability of teacher imple-

mentation of school-based mental health programs. Journal

of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 665–679. doi:10.1007/

s10802-005-7646-2

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N.,

& Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture

(REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and work-

flow process for providing translational research informatics

support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42, 377–381.

doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Hart, J. E., & Malian, I. (2013). A statewide survey of special edu-

cation directors on teacher preparation and licentiate in autism

Brock et al. 79

spectrum disorders: A model for university and state collabo-

ration. International Journal of Special Education, 28, 1–10.

Hendricks, D. R. (2011). A descriptive study of special educa-

tion teachers serving students with autism: Knowledge, prac-

tices employed, and training needs. Journal of Vocational

Rehabilitation, 35, 27–50. doi:10.3233/JVR-2011-0552

Hendricks, D. R., & Wehman, P. (2009). Transition from

school to adulthood for youth with autism spectrum disor-

ders: Review and recommendations. Focus on Autism and

Other Developmental Disabilities, 24, 77–88. doi:10.1177/

1088357608329827

Hess, K. L., Morrier, M. J., Heflin, L. J., & Ivey, M. L. (2008).

Autism treatment survey: Services received by children

with autism spectrum disorders in public school classrooms.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 961–

971. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0470-5

Howlin, P., Gordon, R. K., Pasco, G., Wade, A., & Charman, T.

(2007). The effectiveness of Picture Exchange Communication

System (PECS) training for teachers of children with autism:

A pragmatic, group randomised controlled trial. Journal of

Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 473–481. doi:10.1111/

j.1469-7610.2006.01707.x

Institute of Educational Sciences. (2012). Locale education

agency (school district) universe survey data for 2011-2012.

Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/pubagency.asp

Johnson, L. D., Wehby, J. H., Symons, F. J., Moore, T. C.,

Maggin, D. M., & Sutherland, K. S. (2013). An analysis of

preference relative to teacher implementation of intervention.

The Journal of Special Education. Advance online publica-

tion. doi:10.1177/0022466913475872

Klingner, J. K., Boardman, A. G., & McMaster, K. L. (2013).

What does it take to scale up and sustain evidence-based prac-

tices? Exceptional Children, 79, 195–211.

Kretlow, A. G., & Bartholomew, C. C. (2010). Using coaching to

improve the fidelity of evidence-based practices: A review of

studies. Teacher Education and Special Education, 33, 279–

299. doi:10.1177/0888406410371643

Morrier, M. J., Hess, K. L., & Heflin, L. J. (2011). Teacher train-

ing for implementation of teaching strategies for students with

autism spectrum disorders. Teacher Education and Special

Education, 34, 119–132. doi:10.1177/0888406410376660

National Autism Center. (2009). National standards report.

Retrieved from http://www.nationalautismcenter.org/nsp/

reports.php

Odom, S. L., Collet-Klingenberg, L., Rogers, S. J., & Hatton, D. D.

(2010). Evidence-based practices in interventions for children

and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Preventing School

Failure, 54, 275–282. doi:10.1080/10459881003785506

Odom, S. L., Cox, A. W., Brock, M. E., & National Professional

Development Center. (2013). Implementation science,

professional development, and autism spectrum disorders.

Exceptional Children, 79, 233–251.

Pennington, R. C., & Delano, M. E. (2012). Writing instruction for

students with autism spectrum disorders: A review of litera-

ture. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities,

27, 158–167. doi:10.1177/1088357612451318

Penuel, W. R., Fishman, B. J., Yamaguchi, R., & Gallagher, L.

P. (2007). What makes professional development effective?

Strategies that foster curriculum implementation. American

Educational Research Journal, 44, 921–958. doi:10.3102/

0002831207308221

Ruble, L. A., Usher, E. L., & McGrew, J. H. (2011). Preliminary

investigation of the sources of self-efficacy among teach-

ers of students with autism. Focus on Autism and Other

Developmental Disabilities, 26, 67–74. doi:10.1177/

1088357610378292

Russo, A. (2004). School-based coaching. Harvard Education

Letter, 20(4), 1–4.

Sanford, C., Levine, P., & Blackorby, J. (2008). A national profile

of students with autism. Menlo Park, CA: SRI International.

Segall, M. J., & Campbell, J. M. (2012). Factors relating to

education professionals’ classroom practices for the inclu-

sion of students with autism spectrum disorders. Research

in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 1156–1167. doi:10.1016/

j.rasd.2012.02.007

Shattuck, P. T., Narendorf, S. C., Cooper, B., Sterzing, P. R.,

Wagner, M., & Taylor, J. L. (2012). Postsecondary education

and employment among youth with an autism spectrum disor-

der. Pediatrics, 12, 1042–1049. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2864

Smith, T., Parker, T., Taubman, M., & Lovaas, O. I. (1992). Transfer

of staff training from workshops to group homes: A failure

to generalize across settings. Research in Developmental

Disabilities, 13, 57–71. doi:10.1016/0891-4222(92)90040-D

Stahmer, A. C., Collings, N. M., & Palinkas, L. A. (2005). Early

intervention practices for children with autism: Descriptions

from community providers. Focus on Autism and Other

Developmental Disabilities, 20, 66–79. doi:10.1177/108835

76050200020301

Stein, M. K., & Wang, M. C. (1988). Teacher development and

school improvement: The process of teacher change. Teaching

and Teacher Education, 4, 171–187. doi:10.1016/0742-

051X(88)90016-9

Wagner, M., Newman, L., Cameto, R., Garza, N., & Levine,

P. (2005). After high school: A first look at the postschool

experiences of youth with disabilities. Menlo Park, CA: SRI

International.

Wilson, K. P., Dykstra, J. R., Watson, L. R., Boyd, B. A., & Crais,

E. R. (2012). Coaching in early education classrooms serving

children with autism: A pilot study. Early Childhood Education

Journal, 40, 97–105. doi:10.1007/s10643-011-0493-6

View publication statsView publication stats