1

Submission relating to Australia’s tax treaty network: updating

the Australia-U.S. tax treaty

Introduction

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on issues related to Australia’s tax treaty network.

The fact that a submission of this nature is once again necessary, following the 2021 consultation on

Australia’s tax treaty network, serves to underscore the continuation of the particularly unsatisfactory

state of affairs in relation to the Australia-U.S. tax treaty.

If anything has changed in the past 12 months, it is only that the calls for treaty reform have become

more strident as more people have realised how the current bilateral tax treaty works to disadvantage

them. These include Australians who live and work in the United States, and United States citizens

who have lived and worked in Australia for many years and whose connections with the U.S. may be

extremely limited.

I believe that there are two broad problems with the current tax treaty: the way it is allowed to

operate as a tool of U.S. citizenship-based taxation policy (which only the U.S. can change),

allowing the U.S. to impose its tax regime on residents and citizens of Australia; and a number of

specific provisions in the treaty which can and should be revised, notwithstanding the U.S. taxation

framework.

Background

Australia has long employed a tax treaty framework with the United States, underpinning important

economic, taxation, and business aspects of the relationship with a major trading partner and key

ally. However, the current bilateral tax agreement -- the Convention between the Government of the

United States of America and the Government of Australia for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and

the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with Respect to Taxes on Income (“the treaty”) -- was originally

signed in the early 1980s and has not received attention since 2001.

The treaty includes a number of serious omissions, anomalies and confusing provisions resulting in

punitive and double taxation. For example, it fails to appropriately address the taxation of

superannuation or take account of the modern investment environment with structures such as

managed funds and exchange traded funds. Key provisions of the treaty do not align with the more

recent thinking as reflected in more recent bilateral Australian treaties and with the provisions of the

OECD and U.S. Model Tax Treaties.

The present invitation to consider issues relating to Australia’s tax treaty network provides an important

opportunity to modernise and improve the tax treaty framework between the U.S. and Australia.

The United States’ unique practice of citizenship-based taxation means that reforming the treaty is

particularly important to individual taxpayers, including dual Australian-U.S. citizens living and

working in Australia, and Australians who live and work in the U.S. It is also important to Australia

as a whole, for trade, investment and employment reasons.

2

I was born in the U.S. and left there to live overseas in the 1970s. I have lived in Australia since 1989

and acquired Australian citizenship in 1993. I have been personally and significantly adversely

impacted, over many years, by provisions of the current U.S-Australia bilateral tax treaty. My life

has been in Australia for more than 30 years. I own no U.S. property and have no U.S. residence.

However, none of this matters under the current treaty. For U.S. citizens in Australia, the current tax

treaty (combined with the virtually unique U.S. policy of citizenship-based taxation) is financially

disadvantageous in many ways. For example, under the current treaty, Australia allows the U.S. to

tax Australian superannuation contributions and income, Australian investment earnings, and capital

gains on the sale of an Australian house.

U.S. citizens who find themselves with U.S. tax obligations also face difficult, complex, and costly

compliance with the various intricate U.S. tax rules. Even the process of renouncing U.S. citizenship

can involve confiscatory U.S. taxes on Australian-owned assets.

What is clearly needed is for the Australian Government to take the initiative to open a dialogue

aimed at rectifying the problems with the current treaty. A few of these are noted below.

See also Fix the Tax Treaty!’s 2021 submission at Attachment 1 for further comments on these and

other issues. I support the analysis and recommendations in that submission and would draw

particular attention to the useful Table of specific improvement opportunities.

A number of international tax experts have commented on issues relevant to the pressing need for

reform of the current treaty. Some selected comments are at Attachment 2, including recent

comments by citizenship and tax treaty policy expert John Richardson.

Superannuation

The current U.S.-Australia tax treaty does not address, and so is unclear about, whether the United

States can impose tax on contributions, earnings and distributions from Australian superannuation

funds that are owned by US citizens residing in Australia. It is not just the imposition of U.S. tax

that is at stake, but also the filing of a multitude of U.S. tax reporting forms which may or may not be

required in relation to Australian superannuation.

This means that there is a U.S. tax on Australian superannuation accounts held by Australian citizens

living in Australia, who also happen to be U.S. citizens. This is the case regardless of how long the

U.S. citizen has lived and worked in Australia and even if the person has no U.S. residence.

Because the current treaty does not mention superannuation, there is serious and costly confusion

about how superannuation should be treated for U.S. tax purposes. There are no clear answers and no

consensus within the tax/legal community about these issues. The estimated 200 000 - 300 000

American taxpayers in Australia, including those who also have Australian citizenship, as well as

Australian citizens residing in the United States, are left confused about where they stand.

The systemic differences between Australian superannuation and U.S. retirement schemes have

inhibited the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) from reconciling a U.S. citizen’s Australian

superannuation as what it actually is: a privatised national pension program which forms a key

component of Australia’s overall national pension scheme.

3

A common view is that the U.S. tax treatment of Australian superannuation includes the U.S. having

taxing authority over vested Australian superannuation benefits, under Article 18, and the U.S. retains

the right, under Article 1, to tax superannuation contributions and accumulated earnings. Not even a

defined benefits retirement plan such as the Public Sector Superannuation Scheme, which is paid to

former Australian government employees, is safe from U.S. tax. Although one might argue that the

PSS is a government pension, Article 19 of the treaty reveals that Australian government pensions are

not exempt from U.S. taxation where the recipient is a U.S. citizen at the time that the government

employment began.

As one leading U.S. expat tax expert points out:

“When you couple the worldwide taxation of U.S. persons with the global nature of the various

US attribution regimes, it becomes clear that it is difficult for U.S. persons (who are also residents

of Australia) to utilise Australian trusts or funds for tax planning. This includes Australian

superannuation funds” (P Harper, https://asenaadvisors.com/knowledge-

centre/whitepapers/taxation-of-foreign-pensions/ ).

The impact of these arrangements is that U.S. citizens who also happen to live in Australia, including

those who are also Australian citizens, are taxed on their retirement funds without regard to the

domestic tax laws of Australia.

Australians are encouraged to save for their own retirement, with incentives for maximising voluntary

contributions to their superannuation accounts, including non-concessional contributions. However,

for Australians who also have a U.S. tax obligation, voluntary contributions which exceed employer

contributions can result in the account being regarded by the U.S. as a grantor trust, resulting in

punitive taxation and costly and burdensome reporting requirements. Was that Australia’s intention in

encouraging participation in superannuation?

To quote one U.S. citizen in Australia:

“It was an absolute shocker to learn that the US government could make tax claims on my

Australian superannuation. Normal reasoning is that Australian superannuation is Australia’s plan

to facilitate retirement of Australian workers, and it has nothing to do with the US government.

The next normal reasoning was that even [if] the US government would make such outrageous

claims, surely the Australian government would not let those US claims be legal in Australia.

Surprise! Why the Australian government would ‘authorise’ US tax claims on Australian

superannuation beggars belief. To top off this surreal situation . . . someone could find

themselves entrapped with US tax on 100% of their Australian superannuation withdrawals upon

retirement. How bizarre is that?” (https://fixthetaxtreaty.org/2016/08/31/entrapment/)

How bizarre indeed.

It has also been suggested that movements between superannuation accounts, including simple rollovers,

could be considered as a distribution or ‘tax event’ by the U.S. Moving superannuation assets from a

pension account back to an accumulation account, to meet the $1.6m balance cap, may therefore have

adverse tax consequences for U.S. citizens under the U.S. tax doctrines of economic performance and

constructive receipt (see Dungog, How the super reforms impact US expats, 12 May 2017,

https://www.smsfadviser.com/strategy/15482-how-the-super-reforms-impact-us-expats). It has also been

suggested that in some circumstances, the U.S. may tax the growth within a superannuation account.

4

Due to the significant financial impacts of the U.S. tax treatment of Australian superannuation, U.S.

citizens in Australia are now advised to avoid making non-concessional superannuation contributions –

thereby increasing the likelihood of needing to draw on an Australian Government pension.

So why not simply renounce U.S. citizenship? For U.S. citizens in Australia who wish to renounce

their U.S. citizenship – a difficult and costly exercise -- the issue of how Australian superannuation is

regarded under U.S. tax rules is particularly relevant. The U.S. imposes an ‘exit tax’ on expatriating

U.S. citizens whose financial assets total more than US$2 million (an amount which has not been

adjusted for inflation). For these purposes, financial assets include all giftable assets including your

residence and, according to most interpretations, the entire balance of superannuation accounts on the

day before expatriation. Whether superannuation is or is not included in the exit tax base is therefore a

significant concern. Is it a ‘deferred compensation plan’? Another type of financial asset? Is it a form

of social security? The financial stakes are very high when it comes to the proper characterisation of

Australian superannuation.

There are currently no references in Article 18 of the treaty to the taxation of contributions and

earnings derived by a pension plan prior to an individual being in receipt of their benefits.

Consequently, the treaty does not provide effective protection against double taxation of contributions

and income accumulating within a pension plan.

I have seen differing interpretations – all from international legal and financial experts – about the

operation of the saving clause in the current treaty and what it means for superannuation contributions,

earnings and withdrawals. If the experts find this confusing, what hope is there for anyone else?

These problems could and should be resolved by updating the treaty to clarify that Australian

superannuation is taxable only in Australia. This could be achieved by providing that each country

has exclusive taxation rights on retirement accounts which are set up under that country’s tax rules.

Non-US investments

The treaty should also be updated to reform the punitive U.S. tax on Australian-domiciled Passive

Foreign Investment Corporations (PFICs), which are passive investment structures such as mutual

funds and ETFs.

The treaty does not recognise that U.S. citizens who are also long-term residents and/or citizens of

Australia should be able to adopt financial strategies which include Australian investments, without

incurring high levels of U.S. taxes on these investments.

Saving clause

Article 1(3) of the treaty, known as the ‘saving clause’, allows the U.S. to impose taxation on its

citizens without allowing them any benefits of the treaty. This sweeping provision allows the U.S. to

impose taxation on U.S. citizens (including dual citizens) who are resident in Australia as though the

treaty does NOT exist.

The saving clause allows the U.S. to tax the Australian source income of Australian resident

taxpayers. This erodes their ability to take utilise Australian public policy and tax arrangements

which encourage retirement savings and local investment.

5

The saving clause, and the U.S. practice of citizen-based taxation more generally, frustrates

Australian domestic policy by allowing a foreign government to apply its own peculiar tax rules to

income earned on Australian soil by Australian residents.

For the purposes of taxation, individuals should be treated as only citizens of one country. A

reformed treaty should provide that Australian citizens who reside in Australia could not also be

deemed U.S. citizens under U.S. tax law.

Necessary reforms

At the heart of any treaty reforms should be the interests of Australia as a sovereign country, and the

interests of U.S. citizens who reside and work in Australia, often with Australian citizenship.

Australia’s position with respect to treaty negotiations must be to consider the effect of the treaty on

dual citizens living in Australia and on Australian citizens living in the U.S.

As Dr Karen Alpert, from the group Fix The Tax Treaty!, has noted that the overriding concern

should be that, “Our Australian government has a responsibility to make sure that its international tax

agreements are fit for purpose and are not contrary to domestic policy.”

(https://fixthetaxtreaty.org/2016/08/31/entrapment/ )

Many facets of the recent critique by tax treaty expert John Richardson regarding the new U.S.-

Croatia tax treaty could apply equally to the U.S.-Australia tax treaty. According to Richardson, “the

extension of US tax laws into other countries (1) is a clear assault on the sovereignty of other nations

and (2) allows the United States to syphon capital out of those other nations.”

What Richardson says about the saving clause and how it prevents U.S citizens in Croatia from

beneficial participation in tax-favoured programs in that country could also be said about U.S.

citizens in Australia and their inability to participate in certain financial/retirement planning

programs in Australia – simply because Australia has agreed to allow the U.S. to extend the reach of

its taxes so that they operate to the significant disadvantage of U.S. citizens who also live, work, and

pay taxes in Australia.

Australia should not be agreeing to provisions which disadvantage its residents and citizens and

which are contrary to Australia’s national interest by reducing available retirement income, and

increasing reliance on government pensions, for individuals who find themselves subject to the long

arm of the U.S. tax regime.

The U.S.-Australia tax treaty was signed in 1982, which pre-dated a number of key developments in

the U.S., as well as the establishment of the Australian superannuation system and recent legislation

highlighting its role in Australia’s pension system:

- creation of PFICs by the U.S. in 1986 tax reforms

- 1986 amendments to the U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act making the scope of U.S.

citizenship more evident

- U.S. creation of the ‘tax citizen’ in 2004

- U.S. creation of the ‘exit tax’ in 2008

- creation of FATCA and enhanced reporting requirements in 2010.

6

According to the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), superannuation was far from

widespread in the 1980s and was not transferable between different employers. As a result, until the

mid-1980s, superannuation was generally limited to public servants and white-collar employees of

large corporations. In 1992, the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) was introduced, requiring

employers to make contributions into a super fund on their employees’ behalf.

In 1993, the World Bank endorsed Australia’s ‘three pillar’ system of retirement pensions:

compulsory superannuation, the age pension, and voluntary retirement savings, as world’s best

practice for the provision of retirement income. The superannuation reforms which passed the

Parliament in 2016 further clarified the role of superannuation: ‘to provide income in retirement to

substitute or supplement the Age Pension’.

A major underlying problem with U.S.-Australia bilateral tax arrangements is that U.S. citizens are

taxed on their worldwide income regardless of the source of the income. However, an updated treaty

could modify some of the rules and mitigate some of the major disadvantages faced by U.S. citizens

(including U.S.-Australia dual citizens) who live and work in Australia and have superannuation

accounts.

The best way to ‘future-proof’ the treaty is to ensure that it explicitly states that Australian-source

income of Australian residents is taxable only in Australia.

Superannuation should be treated in a way that is consistent with (and therefore taxed similarly to)

social security – i.e., excluded from U.S. taxation under Article 18(2) of the treaty. (At an absolute

minimum, there should be no doubt that employers’ Superannuation Guarantee contributions should

be treated as social security.)

My understanding – which may or may not be correct – is that the 2016 U.S. Model Tax Treaty

(https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/treaties/documents/treaty-us%20model-

2016.pdf) provides a framework for excluding superannuation contributions and earnings from U.S.

taxation. The Model Treaty provides that contributions attributable to employment paid to a pension

fund by or on behalf of the individual during the employment period are deductible or excludable in

determining the individual’s U.S. tax. Also, any accrued pension benefits or employer contributions

attributable to employment made by the U.S. person’s employer are not treated as taxable to the

individual for U.S. tax purposes. These Model Treaty provisions are also exempted from the saving

clause.

Although I have seen differing interpretations of this, Article 17 of the Model Treaty appears to

exempt both pensions and social security from U.S. taxation. Sections 2, 3 and 6 are not affected by

the saving clause. The most recent intention of the U.S. appears to be that treaties should exempt

Australian pensions and social security from U.S. taxation. This, and much else, needs to be made

explicit in the U.S.-Australia treaty.

Margo Saunders

22 December 2022

Attachment 1: Update Proposal for the Outdated Australia-US Tax Treaty --

Submission to Treasury by Fix the Tax Treaty! - 30 October 2021

Attachment 2: Expert commentaries on the U.S.-Australia tax treaty - selected quotes from

supporting material

7

Attachment 1

Update Proposal for the Outdated

Australia-US Tax Treaty

Submission to Treasury by Fix the Tax Treaty!

30 October 2021

8

Update Proposal for the Outdated

Australia-US Tax Treaty

Submission to Treasury by Fix the Tax Treaty!

30 October 2021

Introduction

We are pleased to provide this submission to Treasury recommending updates to the Australia-US tax treaty.

These updates are aligned with the plans recently announced by the Australian Treasurer, the Hon Josh

Frydenberg MP, to enter into a number of new and updated tax treaties by 2023.

Targeted Australia–US tax treaty reform will enhance labour mobility between our countries, preserve

Australian sovereignty and intent over domestic policies, minimise unwarranted tax leakage and, most

importantly, provide the same fair go for all Australians.

Australia has long employed a tax treaty framework with the US, underpinning important economic, taxation,

and business aspects of our relationship with our third largest trading partner and key ally. However, the current

Australia-US tax treaty is over two decades old

1

and fails to appropriately address the taxation of superannuation

or take account of the modern investment environment with structures such as managed funds and exchange

traded funds. The present invitation to consider issues relating to Australia’s tax treaty network provides an

important opportunity to modernise and improve the tax treaty framework between our two countries.

Although treaty modernisation and update will no doubt enhance foreign investment and trade opportunities,

the focus of this submission is on much-needed improvements which will positively impact individuals,

specifically taxpayers with tax obligations in both countries. The United States’ unique practice of citizenship-

based taxation means that reforming the Australia-US tax treaty is particularly important to individual taxpayers

– including dual Australian-US citizens living in Australia.

The current tax treaty has numerous gaps and anomalies resulting in punitive and double taxation. For brevity’s

sake, this submission focuses on a few of the most critical issues, some of which would be effectively addressed

by updating the treaty to reflect the current OECD and US model tax treaty framework. Please see the Appendix

to this submission for a table detailing a more extensive improvement opportunity list. These issues are also

widely discussed on the Fix the Tax Treaty! website.

2

Let’s Fix the Tax Treaty! (FTT) is an Australian focused advocacy group representing individuals, including

dual Australian-US citizens, who are adversely impacted by inadequate tax treaty protection for Australian-

sourced income under the current Australia-US tax treaty. We advocate for changes to the Treaty to seek relief

from the considerable cost of compliance complexity, as well as penalties and discrimination against a subclass

of Australian citizens and tax residents while also reducing the resulting negative impacts and costs to the

Australian economy and therefore to all Australians.

FTT currently has nearly 1,500 directly affiliated members with our efforts undertaken on behalf of a large and

diverse stakeholder group of impacted Australians, estimated to be in excess of 400,000 persons, including dual

citizens, permanent residents and their dependants living in both countries.

Why the Australia US Tax Treaty needs to be updated

Tax treaties are intended to prevent double taxation, improve cross-border tax efficiencies and eliminate tax

evasion. Many of the failings of the current treaty are due to the unique

3

US practice of taxing on the basis of

citizenship, rather than country of residence, which is the convention accepted by the rest of the world. This

1

While the treaty was originally ratified in 1983, it was updated via a protocol ratified in 2001 (and negotiated in the late

1990s).

2

www.fixthetaxtreaty.org

3

Some would cite Eritrea as also practicing citizenship-based taxation. However, unlike the US, Eritrea does not impose

its full domestic tax code on its diaspora as if they were resident in Eritrea.

9

leads to instances of double taxation, considerable compliance complexity and material financial risks that

directly impact most dual-country taxpayers. In fact, the current treaty guarantees unfair taxation by the US of

some Australian source income, including superannuation. The excessive compliance burden is felt particularly

by low- and middle-income individuals who are less able to afford the cost of both tax preparation and the

sophisticated financial planning required to effectively save for retirement while simultaneously subject to two

different tax systems.

This submission focuses on four material areas requiring reform: 1) Retirement savings, most importantly US

tax treatment of superannuation; 2) US tax treatment of Australian domiciled managed fund investments;

3) non-alignment of capital gains taxation on the sale of a personal residence; and 4) the inclusion of a “saving

clause” in the treaty which guarantees the ability of the US to collect US tax on the Australian income of

Australian residents. Improvement opportunities are identified in this discussion and summarised again in the

recommendations.

Key Reform Issues

Retirement Savings

Labour mobility is impeded when the destination country can tax funds that are invested in source country

retirement savings that are not currently accessible due to preservation requirements. The current OECD and

US model tax treaties address this problem, both during the accumulation phase and the drawdown (post-

retirement) phase. Essentially, the treaty should require each country to respect the tax-deferred accounts

available in the other country, align taxation of retirement savings and defer any individual taxation until funds

are withdrawn. Pragmatically, it is in neither country’s interest to permit inter-country tax leakage from key

retirement saving programs.

For internationally mobile workers, the current tax treaty framework discourages use of tax advantaged

retirement savings schemes as the promised tax benefits may not be available once they have moved to a

different country. Guaranteeing that these workers will receive the tax benefits promised will better incentivise

prudent retirement planning and reduce reliance on government funded programs such as the Age Pension.

Superannuation

The 2001 Australia-US Tax Treaty does not even mention superannuation, despite it being widely mandated in

Australia since 1992. As superannuation is not addressed in the existing tax treaty, nor has either country issued

any formal taxation guidance, there has been, and continues to be, much uncertainty about the “correct” way

to include superannuation on a US tax return, even among IRS agents.

4

This uncertainty affects not only US citizens and green-card holders living in Australia, but also any Australian

citizen or former resident currently living in the US who accumulated superannuation while resident in

Australia, thereby discouraging labour mobility. Retirement savings taxation is recognised in more

contemporary treaties; with the more recent US Tax Treaties containing provisions that respect the tax deferral

of “foreign” retirement plans. See, for example, Articles 17 and 18 of the 2016 US Model Tax Treaty. With

regard to retirement plans, both the UK and Canada have more favourable US tax treaties than Australia.

In the case of Australian residents, US tax on Australian superannuation of Australian residents is contrary to

the interests of Australia as it reduces the ability of Australians to save to fund their retirement and increases

the probability that the affected Australian citizens will be reliant on the Australian government for Age Pension

once they retire. The US should have no claim on super – especially of Australian residents.

Given the lack of tax treaty clarity or IRS guidance on the taxation treatment of superannuation, it has been left

to the individual taxpayers and the compliance industry to classify superannuation based on the US foreign

entity classification regulations for federal tax purposes. This complex task is made even more difficult by the

range of permitted superannuation types, including industry, retail, public sector (including defined benefit

plans) and self-managed super funds (SMSFs).

4

Internal IRS correspondence obtained under Freedom of Information is available at

https://www.bragertaxlaw.com/files/lbi_responsive_docs.pdf.

10

While most US tax professionals include superannuation contributions in the US taxable income of the

individual recipient, there is uncertainty around whether contribution taxes paid by the fund are available as

foreign tax credits to offset US tax on the contributions. As well, certain types of superannuation arrangements

require extensive information reporting because they are treated by the US as “foreign” grantor trusts. There

are also a small number of US tax professionals who argue that Superannuation is equivalent to US Social

Security,

5

and therefore some or all of the contributions and subsequent withdrawals are excluded from US

taxation under Article 18 paragraph 2 of the tax treaty. Finally, since superannuation is not a qualified US

retirement plan, any movement of super balances between funds may be treated as a taxable distribution. This

includes consolidation of fund balances or rollovers when changing employment, all of which are tax free

transactions under Australian tax law.

Any US tax owing on superannuation contributions, earnings, rollovers, or distributions will not be offset by a

tax credit for Australian tax paid because these are either tax-free transactions in Australia (for transactions

arising from an account in pension mode), or any tax on investment income or realised gains has been paid

directly by the superannuation fund and not by the individual. Thus, US taxpayers with superannuation accounts

are guaranteed to pay double tax on those accounts – once for income taxed inside their superannuation fund

and once by the US.

Arguably, the major frustration of US taxpayers currently or previously resident in Australia is the uncertainty

of the US tax treatment of superannuation. It would be preferable for this uncertainty to be resolved even before

a new treaty is negotiated. As the competent authority with respect to the current treaty, the ATO should be

actively lobbying the IRS to agree that the superannuation guarantee (at a minimum) is exempt from US tax

under Article 18 paragraph 2 of the current treaty. Given the pension provisions in the current US model treaty,

Australia should adopt a strong position that Australian superannuation not be subject to tax by the US.

In summary, the tax treaty should clarify the treatment of Superannuation commensurate with Australian

domestic public policy and not selectively disadvantage those Australian residents who are also US taxpayers

from the benefit of funding their retirement through the superannuation system, as provided by Australian

domestic tax law.

US retirement accounts

For Australians who spend some time working in the US, the opposite situation also poses tax problems which

can discourage labour mobility. For lower income workers, the US has created what are known as “Roth”

accounts (available both as Individual Retirement Accounts and in a 401(k) account). Taxpayers deposit after-

tax funds into the Roth account with the promise that withdrawals in retirement will be tax free. This contrasts

with “Traditional” retirement accounts where funds are deposited tax free (either exempt from taxation or

deducted from taxable income) while withdrawals in retirement are included in taxable income.

Australian tax rules, however, do not recognise the difference between the Roth and Traditional variants of US

retirement accounts, treating both as foreign trusts where the originally deposited funds are withdrawn tax free,

but the appreciation earned since that initial deposit is taxed as current income. This treatment makes US Roth

retirement accounts toxic for returning Australians who must either pay an early withdrawal penalty to wind up

the Roth account prior to moving back to Australia or pay Australian tax on what they had thought was a tax-

free investment. Incorporation of the retirement provisions in the OECD and US model treaties will go a long

way towards fixing this problem. The treaty should also address the specific types of retirement accounts

available in each country and ensure that the tax benefits promised when and where the accounts were

established will be available to those who move between the US and Australia.

Managed Fund Investments: Passive Foreign Investment Companies

For middle class savers, the most efficient savings vehicle is often a managed fund or exchange traded fund.

For internationally mobile individuals and those Australian residents taxed by the US, the US tax treatment of

certain types of Australian domiciled investments is exceptionally punitive. The US Internal Revenue Code

generally treats many “foreign” investments as if their only purpose were to avoid or defer US tax, with no

ownership distinction made between US and overseas residents. One example of this is the Passive Foreign

Investment Company (PFIC) regulations. PFICs are defined in Section 1297

6

of the Internal Revenue Code as

5

http://fixthetaxtreaty.org/2016/09/10/is-super-equiv-to-social-security/

6

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/1297

11

any foreign (non-US) corporation with either more than 75% passive income or holding more than 50% of assets

for the production of passive income. This is a broad definition and encompasses most managed funds,

exchange traded funds (ETFs), real estate investment trusts and listed investment companies. Start-up

companies with little revenue and large cash holdings can also be classified as PFICs.

Once a company has been classified as a PFIC, the tax consequences for US taxpayers are punitive. The US-

taxpayer shareholder of a PFIC can elect to be taxed annually on any unrealised gain from their investment,

essentially marking the investment to market on an annual basis. This unrealised gain is taxed as ordinary

income, no capital gain concession is allowed. If this election is not made in the first year that the investment

is classified as a PFIC, or the year the investment is purchased by the taxpayer, then a more complex set of rules

applies. Under these rules, not only are capital gains concessions denied on the investment, but any realised

gain is allocated pro-rata over the entire holding period and taxed at the highest available marginal rate

applicable in the year the gain is allocated to (even if the taxpayer’s actual marginal tax rate in that year was

much lower). While foreign tax credit is allowed against this tax, due to the combination of phantom exchange

rate gains and the use of the highest possible US tax rate, foreign tax credit may offset only a small portion of

the gain. On top of this, daily compound interest is computed on this deemed “deferral” over the whole holding

period of the investment. All these gain computations are done in US dollars adding exchange rate risk.

Furthermore, any distributions in excess of 125% of the 3-year rolling average are treated as excess distributions

subject to the same imputation of deferred tax and daily compound interest. No surprise that many tax

professionals describe the PFIC regime as “confiscatory in nature”.

Clearly, it is not tax-effective for a US taxpayer to own a PFIC. However, while the PFIC rules have been in

the Internal Revenue Code since 1986, they were obscure, and anecdotal evidence suggests that PFIC rules have

only been regularly applied to non-US domiciled public managed fund investments since around 2009. This

means that many long-term US expats have been caught with Australian managed investments purchased years

or decades before this new interpretation took hold, leaving them unable to exit their investments without

punitive US taxes being applied. The US tax reporting form for PFICs is also notoriously complex and time-

consuming, adding greatly to compliance costs.

One of the policy objectives of the PFIC provisions was to prevent deferral of US tax through investment in

foreign entities that were not subject to the same rules as US managed funds regarding the distribution of current

income. Clearly this is not a problem with any Australian managed fund that is available to retail investors.

We suggest adding to the Non-Discrimination article in any new treaty a clause that prohibits discrimination

against investments available to retail investors in the other country. This clause would not override securities

law regarding marketing of investments but would provide relief to a mobile workforce who may have assets

in place in one country when they move to the other.

Alternatively, the treaty should include a clause in Article 10, Dividends, that states that Australian investment

structures that are sold to retail investors are not to be considered “foreign corporations” under the PFIC rules.

That is, the treaty should stipulate that retail investments domiciled in one country should not be more punitively

taxed by the other country than their own similar domestic investments.

Gain on sale of personal residence

For individuals in Australia with US tax obligations, capital gain on the sale of a personal residence is taxable

in the US (with a US$250,000 exemption per person). This gain is computed as if the purchase and sale were

in US dollars, potentially leading to currency “phantom gains”. In addition, since US tax rules assume that the

US dollar is the functional currency of all individual taxpayers, discharge of an AUD denominated mortgage

can result in taxable foreign currency gains. When exchange rates have changed since home purchase,

individuals selling a home with a mortgage will have taxable currency related gains on either the home itself,

or the mortgage with an offsetting currency loss on the other side of the transaction. Furthermore, since the

residence is a personal use asset, losses are not allowed, so only the gain side of the currency transaction will

be recognised and taxed.

These rules are particularly problematic for US citizens and green card holders residing in Australia, where no

capital gains tax is paid on the sale of a primary personal residence. Allowing the US to tax capital gains on

Australian real estate owned by Australian residents is contrary to the economic interests of Australia. The Tax

Treaty should:

12

• seek to align treatment of the sale of a personal residence with Australian taxation policy, particularly

as extremely high housing costs in Australia force many to tie up a large proportion of their net assets

in their primary residence;

• stipulate that real property located in one country and owned by a resident of that country cannot be

taxed by the other country. This provision should be included in the list of saving clause exemptions

in Article 1 paragraph 4 of the treaty.

Saving Clause

All US tax treaties contain some form of “Saving Clause” that guarantees the right of the US to tax its citizens

as if the treaty did not exist.

7

In the current Australia-US Tax Treaty, the Saving Clause is found in Article 1

paragraph 3, with a limited list of exceptions in Article 1 paragraph 4. As we have noted, no other developed

country asserts tax jurisdition based on citizenship alone. The Saving Clause allows the US to reach into the

Australian tax base and tax the Australian source income of Australian resident taxpayers. This erodes the ability

of the affected US Persons to take advantage of Australian public policy and legislated tax concessions designed

to encourage retirement savings and local investment.

The Saving Clause, and the US practice of citizenship-based taxation more generally, frustrates Australian

domestic policy by allowing a foreign government to apply its own idiosyncratic tax rules to income earned on

Australian soil by Australian residents. This disadvantages the affected US Persons and increases the likelihood

that they will require Australian government assistance in the form of the Age Pension and other Australian

social safety net programs.

It is a matter for the US Government to determine its own domestic laws, and it is unlikely that the US will

agree to completely remove the Saving Clause from an amended treaty. However, Australia should insist that

the Australian tax base is respected under the treaty. The Australian source income of Australian residents

should be taxable only by Australia.

Summary

There are many other taxation areas that should be addressed, such as taxation of Australian benefits and issues

with business legal structures. These areas are listed in the Appendix to this submission.

The exceptional US practice of citizenship-based taxation mandates tax reporting and compliance from all US

Persons within Australia, of which many are dual citizen, long-term Australian residents of only modest means.

Citizenship-based taxation exposes them, unlike citizens of any other developed country in the world, to the

Sisyphean task of reconciling two complex and disparate domestic tax systems, frequently leading to instances

of double taxation, high compliance costs and increasingly unreasonable penalties and fines. These are exactly

the sorts of issues that a well-crafted tax treaty can help mitigate and an important driver as to why the Australia-

US tax treaty should be prioritised by Treasury and the Morrison Government for reform and update.

Key Recommendations

To summarise, we believe that the Australia-US tax treaty is in urgent need of updating and improvement and

that the current program of tax treaty negotiations provides an important opportunity to positively address a

number of significant issues.

We propose the following key recommendations:

1. The treaty should be updated to reflect the retirement account provisions in the current OECD and US

model treaties. Each country should recognise the tax deferred nature of retirement accounts and ensure

that moving between countries does not materially alter the tax benefits promised when and where the

accounts were established. Contributions to and benefits from any form of pension or retirement plan

should be exempt from the saving clause. At a minimum, SG contributions made on behalf of Australian

residents should be taxable only by Australia and excluded from US taxation.

7

The Saving Clause is explained in detail in this blog post: http://fixthetaxtreaty.org/2017/01/12/explaining-the-saving-

clause-i/

13

2. The treaty should stipulate that retail investments in one country should not be more punitively taxed

in the other country than their own similar domestic investments.

3. The treaty should include a provision that real property located in one country and owned by a resident

of that country cannot be taxed by the other country.

4. The treaty should specify that the Australian source income of Australian residents is taxable only by

Australia.

We appreciate the opportunity to address the areas in which the US-Australia tax treaty can be modernised and

updated to provide more certainty and reduce double taxation for individual taxpayers subject to tax by both

countries. The US practice of taxing based on citizenship rather than residence is particularly harmful to

Australian residents with US citizenship, most of whom are Australian citizens.

Respectfully submitted on behalf of Fix the Tax Treaty! by

Dr Karen Alpert

Founder and Chairperson, Fix the Tax Treaty!

14

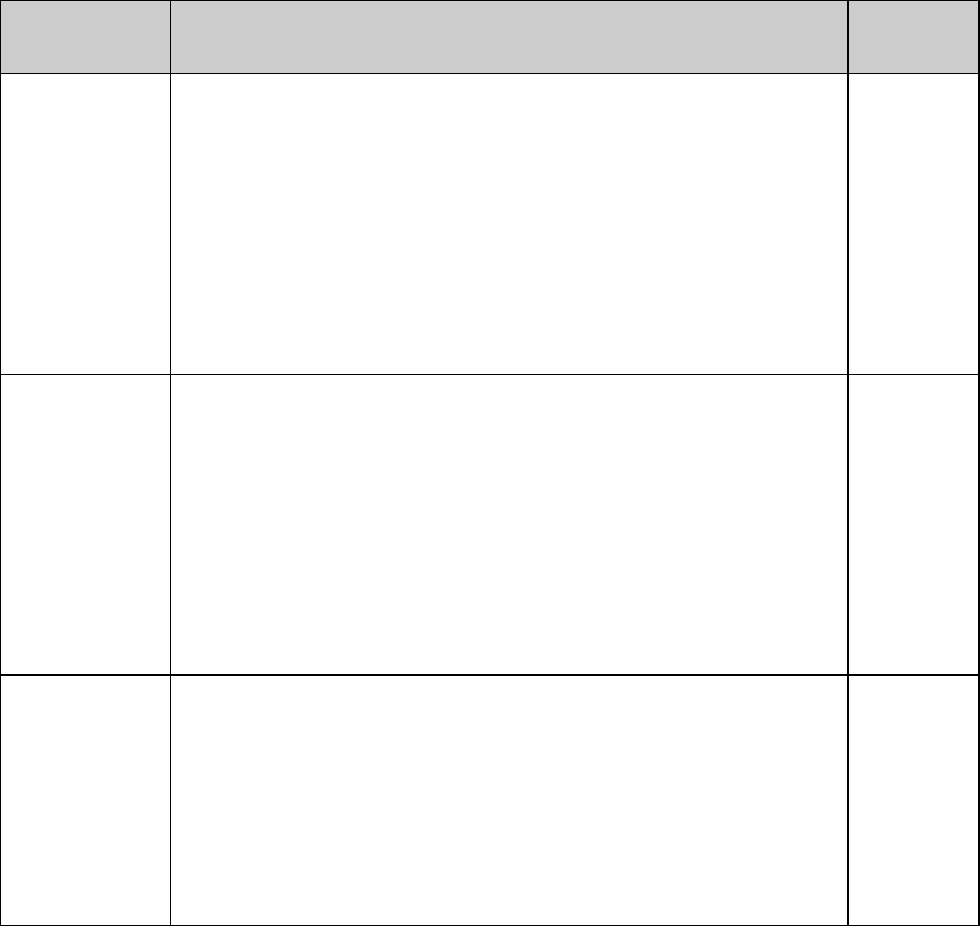

Appendix – Comprehensive Improvement Opportunity List

The following table provides comprehensive detail on identified Tax Treaty issues, listing the specific

items that require change, including associated priorities.

Issue

Detailed Description

Importance

(H/M/L)

Superannuation

Taxation treatment of Superannuation is unclear and not addressed in the

current tax treaty or in formal IRS rulings. There are a variety of ways that

Superannuation can be reported on a US tax return. These range from

completely tax free (as the equivalent of Social Security) to fully taxable

including appreciation inside the fund (as a foreign grantor trust).

Indications are that the IRS is currently pushing the unfavourable grantor

trust interpretation, at least in some circumstances.

The Treaty should clarify the treatment of Superannuation commensurate

with Australian domestic public policy and in such a way not to

disadvantage those who have a mandatory obligation to invest into Super.

High

Retirement

Account

Portability

Labour mobility is impeded when the destination country can tax funds that

are invested in source country retirement savings that are not currently

accessible. The current OECD and US model tax treaties contain articles

that address this problem, both during the accumulation phase and the

drawdown (post-retirement) phase.

Essentially, the treaty should require each country to respect the tax-

deferred accounts available in the other country and defer any individual

taxation until funds are withdrawn. Further simplicity can be attained by

assigning sole taxing rights to the source country with a provision that non-

residents are taxed no more punitively than residents.

High

Sale of principal

residence

Capital gain on the sale of a personal residence is taxable in the US (with a

US$250,000 exemption per person). This gain is computed as if the

purchase and sale were in US dollars, potentially leading to currency

“phantom gains”. In addition, the US will tax any US$ gain on the

discharge of a mortgage on the property. Note that, since the residence is

a personal use asset, losses are not allowed. The Tax Treaty should seek to

align treatment of the sale of a personal residence with Australian taxation

policy, particularly as the high housing cost in Australia forces many to tie

up a large proportion of their net assets in their primary residence.

High

15

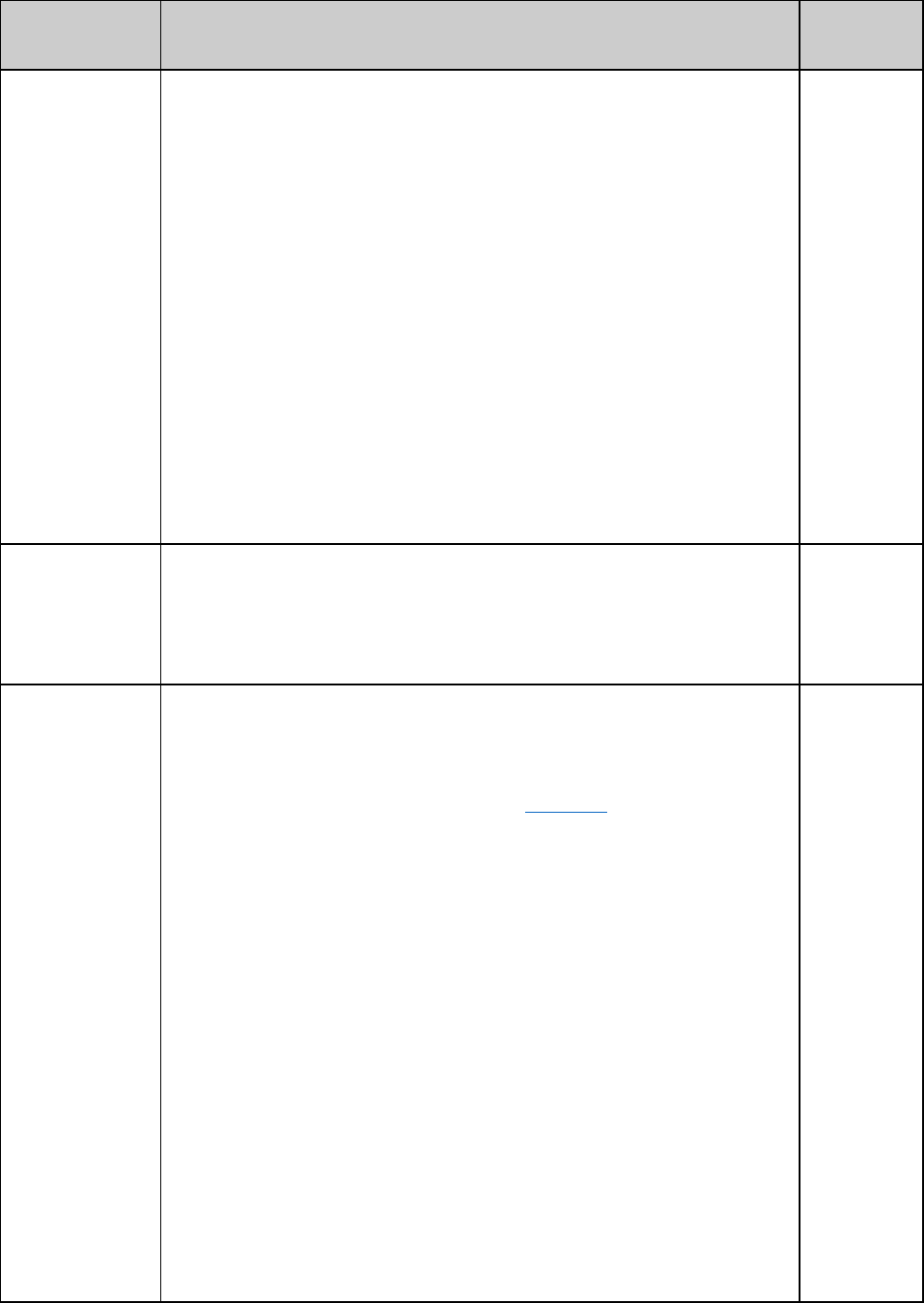

Issue

Detailed Description

Importance

(H/M/L)

PFICs

Australian managed funds, listed investment companies (LICs), real estate

investment companies (A-REITs), and exchange traded funds (ETFs) are

all treated as Passive Foreign Investment Companies (PFICs) for US

taxpayers. PFIC treatment results in punitive taxation of these investment

vehicles, up to the point of being confiscatory in application. PFIC

legislation was enacted prior to the huge growth in managed funds both in

the US and worldwide. Part of the rationale behind this punitive treatment

was to prevent US resident taxpayers from using poorly regulated “foreign”

investments to defer taxable income. But any of these investments that is

registered for sale to retail investors will be required by Australian law to

distribute all income and realised gains currently, just like the American

equivalent.

The treaty should include a clause that states that Australian investment

structures that are sold to retail investors are not to be considered “foreign

corporations” under the PFIC rules. Furthermore, the treaty should

stipulate that retail investments in one country should not be more

punitively taxed in another country than their own similar domestic

investments.

High

Saving Clause

The saving clause allows the US government to impose direct taxation on

some Australian citizens and residents. It denies those who are US citizens

the use of the majority of treaty provisions except for a limited set of

specified provisions. Due to the action of the saving clause, an individual

can be taxed under resident tax rules by both the US and Australia.

High

Transition Tax

and GILTI

The 2017 US tax reform bill (Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, Pub. Law 115-97)

imposed a one-time transition tax on the retained earnings of foreign

corporations owned by US Persons. While Congress never considered the

impact of this tax on tax-residents of other countries, the compliance

industry is busy looking for victims. See this video for an explanation of

the transition tax.

Tax reform also imposed an ongoing tax (starting in 2018) on Global

Intangible Low Taxed Income (GILTI). The way GILTI has been defined,

most controlled foreign corporations will find that some of their active

Australian-source business income has now been re-defined as US-source

income, immediately taxable in the US whether distributed to shareholders

or not. While Australia’s high corporate tax rate may insulate affected

Australian corporations somewhat, the complexity of the associated foreign

tax credit rules could create a US tax liability on top of Australian taxes

paid. Where the US taxes undistributed income of Australian corporations,

they are draining capital from Australia due to the resulting double taxation.

Note that small Australian businesses owned by Australian-resident US

taxpayers are often treated under the US tax code as controlled foreign

corporations subject to these provisions.

The treaty should specify that the undistributed income of Australian

corporations cannot be deemed distributed to US shareholders and that this

provision will not be invalidated by the saving clause.

High

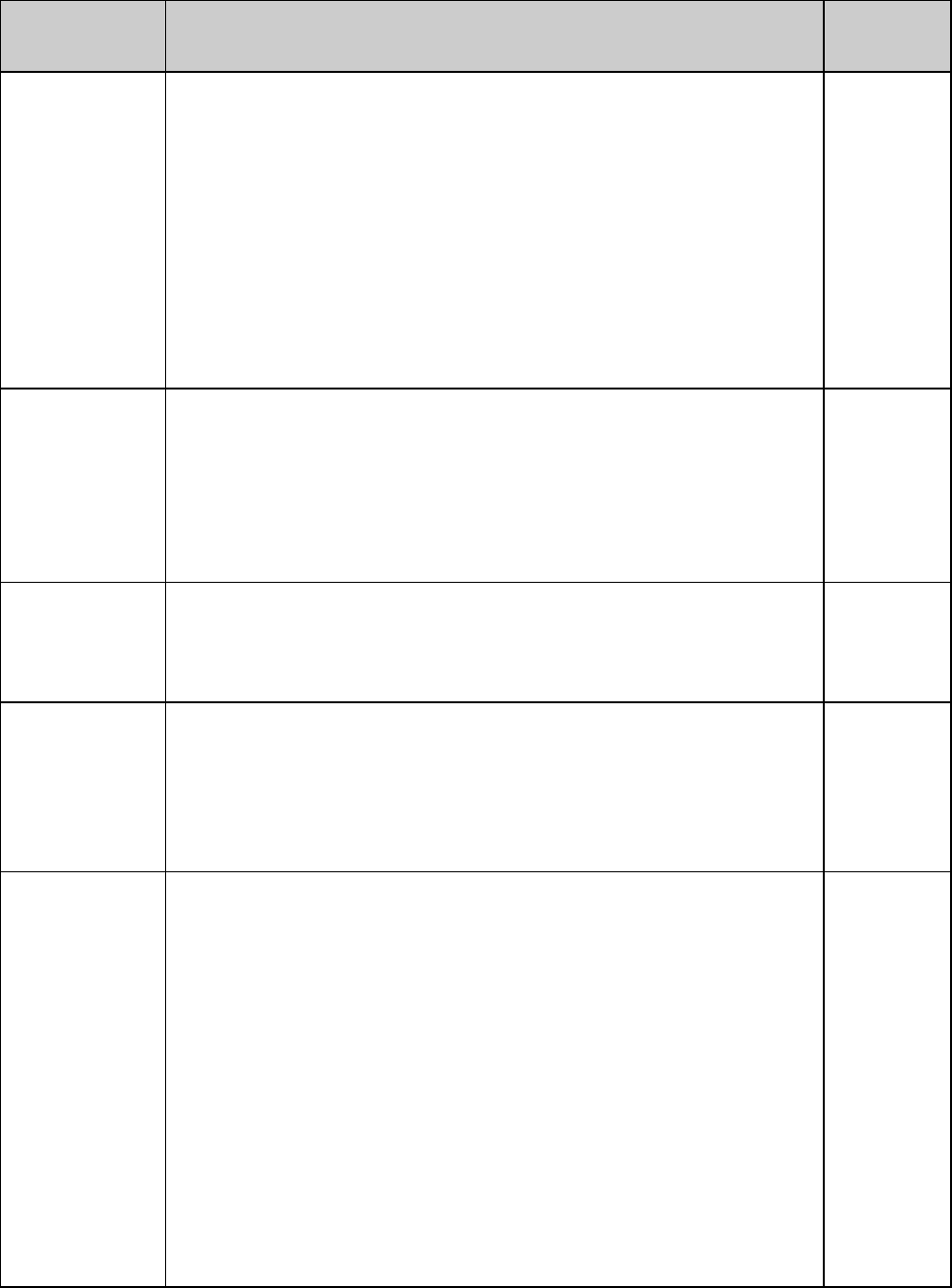

16

Issue

Detailed Description

Importance

(H/M/L)

Effective

nationality /

Accidental

Americans

There is a principle under international law that dual citizens have an

“effective nationality.” Where a dual citizen has closer ties to Australia than

the US, this principle should limit the extraterritorial reach of US tax law.

The case of Accidental Americans illustrates this principle in the extreme.

Accidental Americans were born in the US to Australian parents and

returned to Australia as young children. They have no ties to the US; they

may not even have a US passport or social security number.

Yet, due to their place of birth, the US insists on the right to tax them for

the rest of their life or until they pay US$2,350 to renounce their US

citizenship (the highest fee for renunciation by any country by a factor of

six) and to pay an exit tax in some circumstances.

Medium

Impediments to

using Australian

legal structures

(trusts and

companies)

SMSFs, Family trusts, Australian Corporations and other legitimate

Australian legal structures require complex and extensive disclosure under

US tax law, with punitive penalties (generally starting at US$10,000) for

failure to file information forms. Furthermore, structures that are effective

for Australian tax planning may be disregarded for US tax. The Tax Treaty

should provide for “effective nationality” and limit the US tax treatment of

these structures for Australian nationals.

Medium

Unemployment

and other

Government

benefits

The US taxes Australian unemployment benefits, redundancy and other

Centrelink benefits (except the Age Pension and Disability Pension) as

ordinary income. The Tax Treaty should seek exemptions to US taxation

of Australian domestic social welfare and support payments.

Low

NIIT (Net

Investment

Income Tax)

Enacted as part of Obamacare, NIIT is a flat 3.8% tax on investment income

for US taxpayers whose income exceeds a threshold determined by filing

status. NIIT applies to all investment income, regardless of source, and

cannot be offset by foreign tax credits. For those affected (generally high-

income earners), this is a clear case of double taxation. The treaty should

seek a claw-back provision.

Low

Gift and

Inheritance Tax

While Australia currently has no inheritance or gift taxes, the US does. For

US citizens, worldwide wealth is taxed on death (with an exclusion of about

US$5.5million). For estate tax purposes, it does not matter where in the

world the asset is located, or whether it was owned prior to becoming a US

taxpayer. Tax is based on the value of all assets at death.

While the current exclusion for US citizens is quite high, this could change.

For US citizens residing in Australia, the estate tax will be levied on

Australian assets as well as US assets (even if the decedent has not lived in

the US for decades). For non-US citizens holding US assets at death, the

exclusion is only US$60,000, though there is a 1954 US-Australia Estate

and Gift Tax Treaty that increases the exclusion for US-situs property from

US$60,000 to a pro-rata share of the US$11.5million available to US

citizens. For non-US citizens with more than US$60,000 in US-situs assets,

the compliance cost of preparing a US estate tax return to show zero balance

due could be excessive.

Low

17

Attachment 2

Expert commentaries on the U.S. - Australia tax treaty - selected quotes from

supporting material

1) This article explains how 1 July 2017 legislative reforms to Australian Superannuation laws

further complicate the US tax filing obligations for US expats:

“[For U.S. citizens] Complying with Australian superannuation reforms by 1 July will trigger not just

double, but triple, taxation by the U.S. on their superannuation contributions, earnings and

distributions.”

“Absent bilateral treaty renegotiations, US expats, who are obligated to pay US taxes on their

worldwide income, have no other recourse except to trundle through the byzantine tax laws of both

countries in order to arrive at a defensible (though uncertain) position on why Australian

superannuation funds should not subject to US taxation. Thus far, the certainty and clarity of that

solution has remained elusive. US expats who become fully compliant with their US tax obligations

have done so at a price so steep that many have decided to renounce their US citizenship.”

“While the need for clarity on the US tax treatment of superannuation funds is needed, recent [2017]

changes to Australian taxation and superannuation law significantly raise the need for this

clarification.”

“The U.S. tax laws generally do not recognize concessional employer and employee contributions to

a superannuation fund as non-taxable income to a US expat. On the contrary, both concessional

contributions and earnings accrued on such amounts are treated as a gross income to a US expat,

subject to US tax at ordinary income rates. . . .

- Marsha-Laine Dungog, 2017, How the super reforms impact US expats, 12 May. At:

https://www.smsfadviser.com/strategy/15482-how-the-super-reforms-impact-us-expats

1a) Comment on the above article by Canadian attorney John Richardson, Citizenship Solutions,

Toronto, Canada:

“It is inconceivable that the Government of Australia would have signed a tax treaty with the United

States, that would make it impossible for Australian citizen/residents to have the full benefits of the

Australian Superannuation, for the sole reason that they were born in the United States. The notion

that Australian citizen residents, (born in the United States), could not use the Super to save for

retirement is ridiculous. Contributions to the Super are required by law in Australia.

. . . Case law makes it clear that the treaty is to be interpreted in accordance with the expectations of

BOTH treaty partners. Assuming that the treaty has any relevance, the issue of U.S. taxation of the

Superannuation is NOT something that can be decided ONLY by U.S. lawyers and U.S. Treasury.”

2) “The super fund most susceptible to adverse U.S. tax treatment as a foreign grantor trust is . . . an

SMSF that has a U.S. grantor and a U.S. beneficial owner. When it does, it is most prone to

18

treatment as a foreign grantor trust, which would mean that all contributions and earnings in the

SMSF, including its assets, are attributed directly as owned by its U.S. beneficial owner. Assets that

are foreign equities would be further subject to burdensome treatment as PFICs, which would require

annual tax filings and at worse, payment of PFIC taxes. Preparing a U.S. tax return to disclose

income, gains, and assets held by the SMSF as if the SMSF did not exist poses a substantial financial

burden to the U.S. taxpayer. The SMSF’s unique structure lends itself to this diabolical outcome.”

- Marsha Laine Dungog, 2021, Dixon: A cautionary case of U.S.-Australian tax issues,

22 Feb. At: https://www.withersworldwide.com/en-gb/insight/article/pdf/10025

3) “The Australian and U.S. governments did not address, through the negotiation process for the

[treaty] protocol, the issue regarding the double taxation of retirement saving plans of many

individuals moving between the U.S. and Australia. Had the Australia-U.S. tax treaty been

amended in more recent years, it would be able to address the taxation of cross-border retirement

plans, as other newer treaties have done. Specifically, if the Australia-U.S. tax treaty were

amended to incorporate article 18 of the 2006 and 2016 U.S. model income tax conventions, then

neither the SMSF itself, employee or employer contributions, nor earnings accrued thereafter,

would be subject to U.S. taxes.”

- Marsha Laine Dungog, 2021, Dixon: A cautionary case of U.S.-Australian tax issues, 12 March.

At: https://www.rigbycooke.com.au/dixon-a-cautionary-case-of-u-s-australian-tax-issues/

4) A series of IRS emails obtained under Freedom of Information laws in the US reveals some

confusion about the treatment of Australian superannuation. These emails indicate that at least

through early 2015 some IRS personnel, including those who were presumably in the best

position to understand the intricacies of foreign retirement plans still had many questions. The

emails also make clear that unless there is ‘something specific’ in a treaty exempting the

retirement account from U.S. tax, then it will be taxed by the U.S.

From IRS internal emails obtained under FOI by Brager Tax Law Group:

“The general rule is that we don’t recognize retirement accounts in other countries unless there is

something specific in the treaty with the country that the taxpayer lives and sets up the account that

says we will not tax the income in the account. . . . If it is a country we have a treaty with you have

to research the treaty to see if there is anything that addresses it. Canada has such an item in their

treaty and the UK does too (with restrictions). . . .You need to look at each treaty carefully.

Remember, for a U.S. citizen, you also may need to refer to the so-called ‘saving clause’ . . . for

special rules that allow the United States to tax in some cases as if the treaty had not entered into

force.”

- https://www.bragertaxlaw.com/files/lbi_responsive_docs.pdf

5) This article recognises that both Australia and the U.S. are strong advocates of self-funded

retirement and of the important role that superannuation funds and pension funds have on the

economic development of each country. Each country also recognises the importance of

accommodating a globally mobile workforce.

The article notes that:

19

“In its current form, Art 18 of the Australian treaty has the potential to significantly hinder the free

flow of human capital. Under the current rules:

1. any contribution made to an Australian superannuation fund while an Australian citizen is living

in the US (or US citizen living in Australia) is income taxable in the US; and

2. it is unclear as to the precise manner in which accumulated earnings and vested pension benefits

may be taxed. …”

. . .

- Peter Harper, Taxation of foreign pensions. At:

https://asenaadvisors.com/knowledge-centre/whitepapers/taxation-of-foreign-pensions/

6) Attorney John Richardson explains how the U.S. tax treaty (and, specifically, the ‘saving clause’)

prevents Australia from establishing tax-advantaged retirement programs which benefit all

Australian residents.

It should be noted that these criticisms apply not only to U.S. citizens who are Australian

residents, but also to dual U.S.-Australian citizens!

By virtue of Australia and New Zealand’s bilateral U.S. tax treaties:

“US citizens are disabled from full participation in retirement planning schemes that a country

creates for its residents. Examples include but are NOT limited to the: the Australian

Superannuation, the New Zealand KiwiSaver, and the Canadian TFSA. There are certainly other

countries that have created similar programs (example UK ISA). These programs are all based on the

principle that money is contributed to one of these plans. The income earned in the plan is always

treated tax favourably under the law of the country that created the plan. Either the income earned

inside the plan is not taxed at all (TFSA or ISA) or is taxed at a preferential rate (Australian

Superannuation or New Zealand KiwiSaver). Because US citizens are subject to US tax laws they do

NOT generally (subject to treaty exceptions) receive the tax benefits available to other residents of

their country. (I acknowledge that a variant of the Australian Superannuation is treated as 402(b)

plan under the US Internal Revenue Code).

Q. How can such a perverse state of affairs exist?

A. The injustice is created by US tax treaties!

It’s because of the “saving clause” that is included in all US tax treaties

All US tax treaties contain a “saving clause” pursuant to which the treaty partner agrees that:

(1) US citizens do NOT presumptively receive benefits from the tax treaty; and

(2) the treaty partner agrees that the US may tax its own citizens according to US tax law.

This has unforeseeable effects. One of the effects is that when a country creates a new tax

incentivized plan to encourage its residents to save for retirement, some of its residents are NOT

permitted – because of the disability of US citizenship – to take advantage of that plan!!!

This is the result of a combination of US tax laws (which recognize ONLY US retirement plans), US

citizenship-based taxation (US citizens are subject to US tax laws regardless of where they live), the

“saving clause” found in all US tax treaties (their country of residence agrees that the US may tax US

citizens according to US tax laws) and a failure to anticipate the possibility of developing new

retirement planning programs when negotiating tax treaties with the United States (the Australian

20

Superannuation, New Zealand Kiwisaver and Canadian TFSA were all created AFTER the most

recent tax treaties).

To put it simply:

By entering into tax treaties with the United States, countries are impeding their ability to develop

tax advantaged retirement/savings plans for their residents!!!!!! The USA will generally NOT allow

US citizens to benefit from these plans!

The crippling of part of the population of (at least) three countries ….

Australia – US/Australia tax treaty entered into in 1982 – Australian Superannuation created in 1992

. . .

- John Richardson, ‘How US Tax Treaties and The “Saving Clause” Prevent Countries From

Establishing Retirement Programs For US Citizen Residents’, 22 October 2022. At:

https://citizenshipsolutions.ca/2022/10/28/how-us-tax-treaties-and-the-saving-clause-prevent-

countries-from-establishing-retirement-programs-for-us-citizen-residents/

7) Attorney John Richardson highlights how the U.S. continues to use bilateral tax treaties to

subject U.S. citizens (and even ‘former citizens’!) to punitive tax treatment, to the detriment of

the countries in which these citizens reside.

The overall concerns apply equally to the US-Australia tax treaty – for example: “The extension

of US tax laws into other countries (1) is a clear assault on the sovereignty of other nations and

(2) allows the United States to syphon capital out of those other nations.” The expansion of the

‘saving clause’ is also a particular concern:

This [the saving clause in the new bilateral tax treaty with Croatia] confirms the intentions

(expressed in the August 29, 2022) letter to the Dutch Embassy that the United States fully

intends to impose the terms of the Internal Revenue on code on tax residents of other countries

which happen to be US citizens. The terms of the Internal Revenue Code: (1) a system of US

taxation that is more punitive that the system imposed on resident Americans (2) substantial

reporting requirements (some of which apply even if no tax return is required) and (3) an

aggressive penalty regime.

I emphasize that Croatia has agreed to allow the USA to impose tax on tax residents who are

either (1) currently US citizens or residents and (2) who were US citizens or residents!

Q. What country in its right mind would sign a treaty like this?

A. Only one that didn’t understand what it was signing.

Croatia didn’t understand the impact of US citizenship taxation and how it allows the United

States to extend its tax laws into other countries. The extension of US tax laws into other

countries (1) is a clear assault on the sovereignty of other nations and (2) allows the United States

to syphon capital out of those other nations. (Think the 877A Exit Tax, Transition

Tax, GILTI, PFIC, phantom capital gains and more.) Furthermore, as previously explored: the

“saving clause” will make it impossible for Croatia residents who are US citizens to participate in

certain financial/retirement planning programs in Croatia.

21

The “Saving Clause” And Citizenship Taxation

The United States is the only country that imposes full force of its domestic tax code on its

citizens who live outside the country. For this reason the “saving clause” has a different meaning

to the United States than it does for other countries.

To put it simply:

– For countries that employ residence-based taxation the “saving clause” operates to ensure that

residents of the country do NOT benefit from treaty provisions that are intended to apply to cross

border activities; but

– For the United States (the only country that employs citizenship taxation) the “saving clause”

NOT ONLY prevents US residents from benefiting from treaty provisions, but IN ADDITION

(because of the treaty right to tax its US citizens) it extends US tax jurisdiction and rules

into other countries.

- John Richardson, ‘Croatia Agrees to Allow the US to Impose Tax, Forms and penalties On

Its US Citizen Residents’, 19 December 2022. At:

https://citizenshipsolutions.ca/2022/12/18/croatia-agrees-to-allow-the-us-to-impose-tax-

forms-and-penalties-on-its-us-citizen-

residents/?fbclid=IwAR2wPVusrOdXVKsR7ymvBSEjhzdcw4CK_RxgE2N7hJbGnqxl4mL

mDTGJ2jI