An Overview of the

U.S. Tax System

for Australian Expats

More than one million Australians lived and worked abroad by

2013, with the majority relocating to New Zealand, the U.K. and the

U.S.

1

Today, thousands of Australian citizens move to the U.S. each

year and are immediately subject to the U.S. tax system, yet many

Aussie expats either do not understand how the U.S. tax code will

affect their overall nancial holdings, or do not have an effective tax

strategy in place to gain the most advantageous tax position.

If you have recently arrived in the U.S. or are considering relocation,

you likely have a number of questions. For example, how will the

Internal Revenue Service (IRS) view your holdings in Australia—

especially your Superannuation funds? Are you aware of tax

reporting deadlines, and penalties for noncompliance?

By reading this book, you will better understand:

How relocating to the U.S. will affect your tax liability

Tax reporting requirements for worldwide assets, including

income from foreign accounts

Why Superannuation funds must be addressed

Elements of the U.S. tax reporting system that affect

Australian expats

While not intended to be a comprehensive review of every U.S.

tax requirement, this book highlights some of the most important

U.S. tax principles for Australian expats to understand. As you

will discover, the U.S tax system requires complex reporting with

signicant penalties for noncompliance. With advance preparation,

you can plan your move strategically and position yourself for

nancial success.

Introduction

1.

C ontents

U.S. Individual Income

Tax Principles

PAGE 02

The Australian – U.S.

Tax Treaty

PAGE 04

Sale of Assets and the

Capital Gains Tax

PAGE 06

Reporting Requirements:

Banks, Financial

Accounts and Assets

PAGE 07

The Superannuation

Tax Conundrum

PAGE 09

Conclusion

PAGE 12

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

1

Advance Research

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

1 An Overview of the U.S. Tax System for Australian Expats

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

Generally speaking, if you are considered a tax

resident in the U.S., you will be subject to tax

on your worldwide income, including income

generated from a tax-deferred account in

another country. This can present challenges

for Australians moving to the U.S. who still have

assets that earn income in Australia, especially

when those assets don’t quite match up with

similar instruments in the U.S.

Taxes can be complex anywhere, so the best

place to start is with an understanding of the

various levels of taxation in the U.S.

Four Levels of U.S. Taxation

Australians working in the U.S. should be aware

of four levels of taxation in the U.S. Federal

Income Tax.

1. Federal Income Tax

The U.S. government imposes a federal income

tax that is based on income levels. The federal

government recently enacted tax reform, which

retained seven tax brackets but changed the

rates, ranging from 10% to 37%.

2. State Income Tax

It is important to determine how state taxation will

factor into where you decide to live. Most states

impose personal income tax, with the exception

of Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas,

Washington and Wyoming. State income taxes

vary, but are generally in the range of 0-12.3%.

3. Social Security Tax and Medicare/FICA

This tax is based on “earned” income such as

salary paid to an employee or a sole proprietor’s

earnings. The U.S. Social Security tax of 6.2%

is paid on wages up to a maximum of $142,800

(for 2021). The Medicare tax is 1.45% on wages

(in which there is no maximum). Combined, this

tax is commonly referred to as FICA, Social

Security or Self-employment tax. If you are an

employee, the employer pays FICA tax of 6.2%

and Medicare tax of 1.45% on wages. If you are

a sole proprietor, you pay both the employee and

employer portion which is 12.4% for FICA and

2.9% for Medicare.

4. Local Income Tax

Local income tax, which generally refers to

additional city or county tax, depends on your

work location. Generally speaking, local taxes

are not higher than 1-2%, with the exception of

New York City.

CHAPTER 1

U.S. Individual Income Tax Principles

2 EFPRgroup.com 800.546.7556

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

Income Tax Year for Filing

Purposes

The U.S. income tax year is based on the calendar

year. Tax returns and payment must generally

be led by April 15 of the following year. While

extensions may be led, interest and penalty may

be charged on any tax paid after April 15.

As previously mentioned, the U.S. taxes its

citizens and individuals, who are residents for

income tax purposes, on their worldwide income.

When income is sourced in a foreign country, the

U.S. generally allows a credit for the tax paid on

that same taxed income.

Tax Filing Options

In the U.S., married couples have the option to

le jointly or separately on their federal income

tax returns. By ling a joint tax return, you can

benet from several tax breaks compared to ling

separately. In some cases, it could make more

sense to le separate returns.

Taxpayer Identication Numbers

All individuals ling tax returns must have a U.S.

Social Security number (SSN) or an individual tax

identication number (ITIN). ITINs are important

for selling residences, obtaining driver’s licenses,

opening certain bank accounts and more.

Differences Between Australian –

U.S. Business Structures

Australians planning to work in the U.S. should be

aware that the U.S. has different business entities.

Australia generally has six main structures: sole

trader, company, partnership, trust, unlimited

proprietary (Pty) and proprietary limited (Pty Ltd).

The U.S. business structures also include several

entities, including limited liability companies

(LLCs), partnerships, C corporations, S

corporations and single-member LLCs.

For U.S. tax purposes, a C corporation pays

income tax at the corporate level separate from

its owners. Conversely, the income of a pass-

through entity (S corporation, LLC, partnership,

and single-member LLC) ows through to its

individual owner’s personal income tax return.

A pass-through entity generally does not pay

federal income tax on its own.

Keep in mind that the business structure you have

in Australia may be treated differently in the U.S.

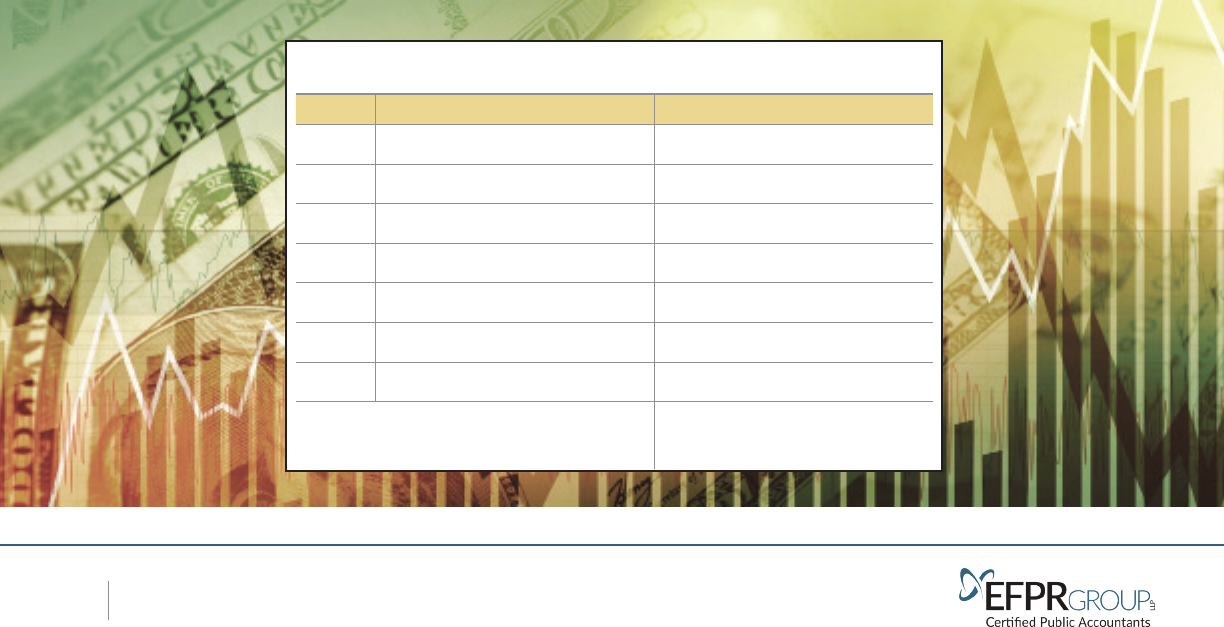

2021 U.S. Tax Brackets

Rate Individuals Married Filing Jointly

10%

Up to $9,875 Up to $19,750

12%

$9,875 – $40,125 $19,750 – $80,250

22%

$40,125 – $85,525 $80,250 – $171,050

24%

$85,525 – $163,300 $171,050 – $326,600

32%

$163,300 – $207,350 $326,600 – $414,700

35%

$207,350 – $518,400 $414,700 – $622,050

37%

Over $518,400 Over $622,050

Standard Deduction: $12,400

Personal Exemption: Eliminated

Standard Deduction: $24,800

Personal Exemption: Eliminated

3 An Overview of the U.S. Tax System for Australian Expats

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

A formal bilateral agreement between two

countries, a tax treaty — commonly known as a

double tax agreement (DTA) — exists mostly for

the purpose of preventing double taxation. A tax

treaty fosters cooperation between countries and

allows each to enforce its respective tax laws.

DTAs also exist to specify rules to resolve dual

claims in relation to the residential status of a

taxpayer and the source of income.

For Australians, tax treaties relate to their

residency status and how tax applies to the

income and business prots they earn, or tax

relief they receive, in the U.S. Of particular interest

for Australian individuals living in the U.S.:

If you are considered to be an Australian

resident for tax purposes (under Australian

domestic law) and a U.S. resident for U.S.

tax purposes (under U.S. domestic law), the

tax treaty provides rules to ensure you are

only a tax resident of one country.

If you are earning income from both

countries, the tax treaty allocates taxing

rights over certain categories of income

between Australia and the U.S.

Foreign Tax Credit Example

If you earned $140,000 of income in Australia

and pay $42,000 of income tax as a nonresident

Australian, you may qualify to claim a FTC of up

to $42,000. In this example, you would make a

claim for a Foreign Tax Credit (Form 1116) on your

U.S. tax return. A foreign tax credit is generally

offered by countries with income tax systems that

tax residents on worldwide income. These tax

credits mitigate double taxation.

Australian Dividend Income

A common question for Australian expats in the

U.S. is how to treat Australian dividend income for

U.S. tax purposes. The franked amount should

be reported as qualied dividends in the U.S.

The imputation credit is

not income and is not

considered a credit on

the U.S. tax return.

Treaty Tiebreaker

The treaty tiebreaker

is a provision meant to

prevent an individual

from being deemed a

resident in both treaty

countries. Typically, a

multistep procedure will be applied to resolve the

problem of dual residence. In most cases, the

location of a permanent home will be the critical

determinant in resolving residency.

The treaty tiebreaker only applies to the

calculation of U.S. income tax by treating the

taxpayer as a nonresident of the U.S., but only

CHAPTER 2

The Australian – U.S. Tax Treaty

Australia’s tax

treaty with the

U.S. dates back

to the 1950s, and

has been amended

through the years.

It was one of the

rst DTAs.

4 EFPRgroup.com 800.546.7556

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

for income tax purposes. Any informational forms

that would be required of a resident will still need

to be led.

The Substantial Presence Test

What happens when you leave Australia halfway

through the year? Are you a resident or a

nonresident for individual tax purposes? The

Substantial Presence Test (SPT) is a criterion

that the IRS uses to ensure that an individual

qualies as either a resident or nonresident for

tax purposes.

To meet this test, you must be physically present

in the U.S. on at least:

31 days during the current year, and

183 days during the three-year period that

includes the current year and the two years

immediately before that, counting:

3 All the days you were present in the

current year, and

3 1/3 of the days you were present in the

rst year before the current year, and

3 1/6 of the days you were present in the

second year before the current year

Under the U.S. tax code, a First-Year Election can

be used by nonresident individuals who arrive in

the U.S. after the midway point of the tax year

and do not obtain a green card in that year, but

do qualify as a resident individual in the following

year under the SPT.

Therefore, an individual who makes the First-Year

Election will be treated as a nonresident individual

for part of the tax year and a resident individual

for the other part of the tax year. To make the

First-Year Election, the individual generally must

satisfy ve requirements:

1. Must have been a nonresident in the

prior year

2. Must not meet the SPT or Green Card Test

in the current year

3. Must satisfy the 31-consecutive-day

requirement

4. Must satisfy the period of continuous

presence requirement

5. Must meet the SPT in the subsequent year

There are also additional elections for individuals

who are married and want to le jointly.

The Substanal Presence Test (SPT) is a

criterion that the IRS uses to ensure that

an individual qualies as either a resident

or nonresident for tax purposes.

5 An Overview of the U.S. Tax System for Australian Expats

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

Australian residents receive a full exemption

from capital gains tax on the sale of a home that

has served as their main residence throughout

ownership. Until recently, they beneted from an

“absence rule,” which allowed them to treat a

dwelling as their main residence for capital gains

tax (CGT) purposes for an unlimited period of time,

as long as they kept it empty and didn’t rent it out.

Under recent reform, Australian homeowners who

sell their main residence while they’re working

overseas will lose the CGT exemption. The new

law was specically intended to exclude foreigners

from obtaining the capital gains exemption, and

expats were included in this measure. This means

Australian homeowners had until June 30, 2019,

to sell their homes without being subject to the

capital gains tax.

Sale of Principal Residence

Because the U.S. taxes worldwide income, some

of the proceeds from the sale of your home may

be included in that amount. As earlier stated, there

is no tax in the U.S. if you resided in the Australian

residence for two of the past ve years. The capital

gain exclusion is $250,000 for a single person and

$500,000 for married persons ling jointly.

If you pay tax on the transaction in Australia, those

taxes can potentially be claimed as a Foreign Tax

Credit on your U.S. return. However, if you sell your

Australian home before the June 2019 deadline,

you will need to include the income from the sale

on your U.S. tax return, as part of your worldwide

income, even though there is no capital gains tax

prior to June 2019 in Australia. You may or may not

owe taxes on this overall sale in the U.S.

Also, if you own rental property in Australia, you

must report any income on that property in the

U.S. You are entitled to the same deductions you

would normally receive in Australia, plus you are

entitled to depreciation over a 40-year period—an

added benet that the IRS allows in its tax code.

Sale of Other Assets

You’ll also want to give careful consideration to

the disposal of your Australian assets and the

potential tax ramications of doing so. As a U.S.

resident for tax purposes, any sale of Australian

assets would be subject to U.S. taxation. Any

Australian taxes paid would be subject to the

foreign tax credit calculations.

You will want to be strategic about the timing of

paying off a mortgage as it could trigger ordinary

income from a mortgage disposition exchange

gain. Other considerations include managed fund

or other trust distributions.

You will want to work with your tax advisor to

ensure that your Australian investment assets are

managed and structured in the most advantageous

way. The income generated from those assets will

affect your U.S. taxes and must be reported on the

appropriate forms to avoid any penalties.

CHAPTER 3

Sale of Assets and the Capital Gains Tax

6 EFPRgroup.com 800.546.7556

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

As we addressed in Chapter 2, Australia has an

international tax law treaty with the U.S. and has

signed a FATCA (Foreign Asset Tax Compliance

Act) agreement. The type of assets, investments

and income you maintain overseas will dictate

the layers of complexity for the reporting

requirements you will have in the U.S. The

information in this chapter provides a guide

to what these reports are, and how they may

apply to you.

FinCEN 114 (FBAR)

FBAR is a “Report of Foreign Bank and

Financial Accounts,” or more simply, a foreign

bank account report. The FBAR form is

led electronically with the Financial Crimes

Enforcement Network, a division of the U.S.

Department of Treasury, when a person owns or

has signature authority of an account or accounts

with an annual aggregate balance that exceeds

$10,000 in foreign and overseas accounts on any

given day during the calendar year.

It is important to note that taxpayers who must

le this report in the U.S. include legal permanent

residents (green card holders), individuals

claiming a treaty tie breaker and U.S. part-year

tax residents. Foreign accounts include bank,

investment and nancial accounts and insurance

policies with a combined value of more than

$10,000. Note: Superannuation funds, which we

will address in Chapter 5, must be reported on an

FBAR form each year.

The penalty for failing to le an FBAR is $10,000

and can be levied in cases of willful violation.

FATCA

FATCA is intended to prevent tax evasion by

U.S. taxpayers using offshore accounts. FATCA

requires certain U.S. taxpayers who hold foreign

nancial assets with an aggregate value of more

than the reporting threshold (at least $50,000) to

report information about those assets on Form

8938, which must be attached to the taxpayer’s

annual income tax return.

CHAPTER 4

Reporting Requirements:

Banks, Financial Accounts and Assets

IMPORTANT: The penalty for not ling

each one of these informaon returns

is $10,000.

7 An Overview of the U.S. Tax System for Australian Expats

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

The type of assets, investments and income you maintain

overseas will dictate the layers of complexity for the reporng

requirements you will have in the U.S.

Statement of Foreign Financial Assets

(FATCA Form 8938)

As mentioned above, this form is used to report

specied foreign nancial assets if the total value

of all the specied foreign assets in which you

have an interest is more than the appropriate

reporting threshold.

Passive Foreign Investment Company

(PFIC) – Form 8621

Generally, if a Australian citizen who becomes a

tax resident of the U.S. and owns a mutual fund in

a non-U.S. account, this would be considered a

PFIC. The IRS requires that anyone with an interest

in a PFIC le an annual disclosure and indicate

any growth in this investment and any income

generated. It is important to disclose PFICs in your

initial year of U.S. residency as certain elections

can only be made in the rst year.

Other Asset Filing Requirements

Do you own an Australian mutual fund and plan

to live in the U.S.? What about foreign trusts,

partnership or a Pty Ltd?

Disposal of any Australian assets must be

carefully planned with regard to both Australian

and U.S. capital gains laws. Of course, any of

these assets will be factored into the worldwide

income calculations with regard to U.S. taxation

and ling requirements.

For example, there are a host of international

reporting requirements, which include, but are not

limited to:

Foreign Gift Form (3520)

Foreign Corporation or Foreign Partnership

(5471 or 8865)

Foreign Trust (3520-A)

Passive Foreign Investment Companies

(Form 8621)

Your requirement to le certain forms will depend

on what percentage of ownership you have in

a business.

8 EFPRgroup.com 800.546.7556

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

As you know, Superannuation funds (“Supers”)

are required of most individuals working in

Australia. In most cases, both the employer

and employee deposit funds into the Super,

which offers preferential tax rates on future

investment earnings.

More specically, the Super is funded by

mandatory employer contributions, which are

generally tax-deductible contributions made by

the employer as a percentage of the employee’s

salary. They can also contain concessional

voluntary employee pretax contributions and

nonconcessional voluntary pretax contributions,

which are not tax-deductible but can include

contributions from take-home pay, inheritances

and proceeds from asset sales.

In our earlier discussion about tax treaties, we

addressed how the U.S. and Australia resolve tax

conicts in a cooperative fashion to avoid double

taxation. That works well when dealing with

similar nancial instruments. Supers, which are

generally run as trusts, do not have an exact U.S.

counterpart and are more of a hybrid of several

U.S. savings and retirement accounts.

Currently there is no denitive guidance from the

IRS on how to treat these accounts for U.S. tax

purposes. As a result, opinions vary on how the

income from these accounts should be taxed on

your U.S. income tax return. Typically, a Super is

treated as an employee benets trust or a foreign

grantor trust.

The IRS looks at the contributions made into

the Super to determine grantor trust status. If an

employee’s contribution is equal or less than the

employer’s, then

it’s an employee

trust considered

owned by the foreign

employer. If the

individual personally

funded more than

50% of the Super, it

is more likely to be a

grantor trust.

Foreign

Grantor Trust

The Super may

be considered a grantor trust in the U.S. under

certain conditions, such as when the relevant

grantor individual directly or indirectly made a

transfer to the trust within ve years of becoming

a U.S. resident. This matters from a U.S. tax

perspective because the grantor will be taxed on

their income and capital gains from trust assets

regardless of whether those amounts are actually

distributed.

If the Super is treated as a “foreign grantor

trust”, additional reporting is required. Account

ownership and annual income from the account

is required to be reported on Forms 3520 and

3520A. Contributions and any other growth in the

CHAPTER 5

The Superannuation Tax Conundrum

Supers, which

are generally run

as trusts, do not

have an exact

U.S. counterpart

and are more of a

hybrid of several

U.S. savings

and rerement

accounts.

9 An Overview of the U.S. Tax System for Australian Expats

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

account are taxed on the U.S. Form 1040. PFIC investments within the account also require the ling of

Form 8621 each year. As with the employee benet trusts, Form 8938 and the FinCEN 114 form may also

be required if you meet the reporting requirements.

Those are the general parameters in the U.S. taxation of Supers, but given the complexity and lack of good

guidance in the area, you should work with your tax advisor to determine the proper tax treatment.

Employee Benets Trust

If the account is categorized as an “employee benets trust,” where the foreign employer is considered the

owner, any contributions to the account are taxable in the U.S. in the year of contribution even if Australian

tax is deferred. Income deemed to be taxable in the U.S. needs to be reported on your U.S. tax return and

the account ownership is required to be reported on Form 8938 if you meet the ling requirements.

Examples

U.S. treatment of Supers vary on a case-by-case basis. Here are two examples of how contributions and

fund growth would be treated under the U.S. tax system.

EXAMPLE A

Background:

An Australian/U.S. citizen is living and working in Australia. They are self-employed and operate a

self-directed and self-funded Super.

Likely U.S. Tax Filings:

The Super would be considered a grantor trust

and would face the following U.S tax treatment:

Employer contributions, made on behalf of the

employee, are 100 percent taxable

Employee contributions are not considered

tax deferred in the U.S.

Growth attributable to the employer is fully

taxable as ordinary income.

Growth attributable to the employee is taxed as a grantor trust on form 3520-A

Distributions are tax-free in the U.S. to the extent of basis

PFIC reporting is required if the fund holds mutual fund-type investments

10 EFPRgroup.com 800.546.7556

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

EXAMPLE B

Background:

An Australian individual and spouse relocate to the U.S. on a three-year assignment, arriving on

March 1, 2017. Later that year, the spouse acquires a U.S. job. Their children remain at home in

Australia attending university.

The couple has joint ownership over a non-U.S. bank checking account, and each has a

Superannuation fund in their name. The combined growth in value of the funds is $4,000 during

the U.S. tax year with no fund distributions. The majority of contributions were funded by each

individual’s employer throughout their careers so far.

Likely U.S. Tax Filings:

The couple elect to le as full-year U.S. tax residents on a joint tax return as it results in a

lower overall U.S. federal and state tax liability

Their children are not eligible to be claimed as dependents as they are not considered

residents in the U.S.

Both spouses are not considered “highly compensated” individuals under U.S. tax law

(i.e., earned less than $120,000 in the preceding year)

Both spouses report their share of interest income earned on their non-U.S. savings account

Both spouses report their interest in non-U.S. bank accounts and the Superannuation

accounts on Form 8938

Both spouses report their interest in non-U.S. bank accounts and the Superannuation

accounts on FinCEN 114 (FBAR)

The $4,000 growth in value of the

Superannuation fund is not reported as

income during the tax year

The Super funds are considered non-

U.S. trusts “owned” by the Australian

employers — so there is no additional U.S.

information reporting (i.e., Form 3520-A)

Neither individual is considered a “highly

compensated” individual resulting in

deferred taxation of the unrealized gains

(i.e., subject to tax upon distribution)

11 An Overview of the U.S. Tax System for Australian Expats

Please consult your tax advisor who may conrm the applicability of the U.S. tax law to your U.S. tax situation.

The last thing you want when you relocate from Australia to the U.S. is to pay extra taxes or penalties that

could be avoided with pre-departure planning. The information presented in our book provides you with an

overview of the issues you should be aware of and raises questions that could merit further discussion.

As we discussed, tax treaties are useful instruments for two countries to determine fair taxation of an

individual. However, given complexities that don’t neatly t the tax treaty framework, it is best to learn how

to prociently navigate the process and ensure that you comply with all required ling rules.

The International Tax team at EFPR Group works closely with their clients to arrive at the best approaches

for your particular set of circumstances. Ideally, we work with individuals and businesses pre-departure

and upon arrival—advanced planning is critical to attain maximum tax savings for you.

CONCLUSION

Helping You Navigate the Process

585.340.5121

iTax@EFPRgroup.com

EFPRgroup.com

Richele Emich-Sharn, CPA, Partner

Kevin C. Hill, CPA, Partner

Scott Buckley, CPA, EA, Manager

Richard Mather, EA, MSA, CAA, Manager

EFPR Group

International Tax Team

12 EFPRgroup.com 800.546.7556