83

ATOMIC BOMBS

The War in the Pacific

LESSON PLAN

The Most Terrible Thing, but Possibly the Most Useful:

Evaluating the US Decision to Drop the Atomic Bombs

Atomic bombs

INTRODUCTION

Shortly after the first successful atomic bomb test in July 1945, President Harry S. Truman wrote in his

diary that “this atomic bomb . . . seems to be the most terrible thing ever discovered, but it can be made

the most useful.” The president’s conflicted feelings about the bomb captured the divergent poles in a

debate that has raged since he authorized its use against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki in August 1945. While some historians contend that the use of atomic weapons saved

American and Japanese lives by speeding the war’s end, others maintain that the bombs were neither

necessary nor justified since other means may have been available to end the war. In this lesson,

students engage in this debate by examining primary and secondary sources—and the evidence

contained within them—in order to determine which interpretation of the decision to use atomic bombs

they find most convincing.

OBJECTIVE

By analyzing a range of primary and secondary source materials, students will develop an interpretation

of the US use of atomic weapons against Japan and provide evidence to support their conclusion.

GRADE LEVEL

7–12

TIME REQUIREMENT

1–2 class periods

MATERIALS

This lesson plan uses evidence strips included

as inserts with the printed guide and online at

ww2classroom.org.

(Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ds-05458.)

LESSON PLAN:

ONLINE RESOURCES

ww2classroom.org

The primary source images and evidence

strips referenced in this lesson plan are

available online.

Lawrence Johnston Oral History

The Bomb Video

Operation Downfall Map

Recording of Harry S. Truman’s Atomic Bomb

Address, August 9, 1945

84

ATOMIC BOMBS

The War in the Pacific

LESSON PLAN

STANDARDS

COMMON CORE STANDARDS

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.1

Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such

features as the date and origin of the information.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.8

Assess the extent to which the reasoning and evidence in a text support the author’s claims.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.9

Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.7

Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media

(e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in order to address a question or solve a problem.

NATIONAL STANDARDS FOR HISTORY

CONTENT ERA 8, STANDARD 3B

The student is able to evaluate the decision to employ nuclear weapons against Japan and assess later

controversies over the decision.

HISTORICAL THINKING STANDARD 3

The student is able to compare competing historical narratives and evaluate major debates among

historians concerning alternative interpretations of the past.

HISTORICAL THINKING STANDARD 4

The student is able to support interpretations with historical evidence in order to construct closely

reasoned arguments rather than facile opinions.

HISTORICAL THINKING STANDARD 4

The student is able to interrogate historical data by uncovering the social, political, and economic

context in which it was created; testing the data source for its credibility, authority, authenticity, internal

consistency, and completeness; and detecting and evaluating bias, distortion, and propaganda by

omission, suppression, or invention of facts.

HISTORICAL THINKING STANDARD 5

The student is able to evaluate alternative courses of action, keeping in mind the information available at

the time, in terms of ethical considerations, the interests of those affected by the decision, and the long-

and short-term consequences of each.

TEACHER

85

ATOMIC BOMBS

The War in the Pacific

LESSON PLAN

PROCEDURE

1. Use the Overview Essay to introduce your students to the US development and use of atomic weapons

and to the debate among historians over the reasons for dropping the bombs, the alternatives that

existed at the time, and whether the bombs were necessary to end the war.

2. Introduce the two interpretations from historians Sadao Asada and Barton Bernstein regarding the use

of atomic weapons during World War II (page 87), informing students that they will be examining

multiple primary and secondary sources in order to determine which interpretation they find most

convincing. As you introduce the interpretations, have students identify the similarities and differences

between them and clarify difficult vocabulary.

3. Distribute copies of the Evidence Collection Worksheets (pages 91–92) to students and explain that

they will use the worksheets to gather and organize evidence according to the interpretation that the

evidence best supports. Inform students that they will also be responsible for explaining how individual

pieces of evidence support a particular interpretation. You may need to give each student multiple

copies of the worksheet.

4. Divide the class into groups and distribute one set of the images (pages 88–90 and online at

ww2classroom.org) and the evidence strips (available as an insert with the printed guide and at

ww2classroom.org) to each group. Alternatively, you may want to have students work in pairs, assigning

each pair a single evidence strip or image to examine and discuss before rotating to analyze additional

sources.

5. Instruct students to assign each image and evidence strip to at least one interpretation and to record

that evidence and an explanation of how it supports the interpretation on the appropriate Evidence

Collection Worksheet. Remind students to be attentive to the date, origin, and type of each source they

are examining and to consider how those features affect the source’s reliability. To model this exercise,

you may want to highlight evidence from one of the strips and/or images that supports each

interpretation and provide explanations for each of those pieces of evidence before students practice

independently.

6. After students have assigned each source to an interpretation, have them identify the interpretation

for which they have compiled the most convincing supporting evidence and explanations.

7. Have students engage in a historical debate about their preferred interpretations, drawing upon the

evidence they gathered to support their claims.

ASSESSMENT

You will be able to assess students’ understanding of the relevant standards through the notes they take

on their Evidence Collection Worksheets, their discussion, and their homework assignment.

EXTENSION/ENRICHMENT

• For homework, have students write a 250-word text panel for a museum display about the US use of

atomic bombs during World War II. Emphasize to students that, given space limitations, they will need

to choose an argument or point of view in order to frame their narrative.

• Have students learn more about the atomic bombs through the oral histories and photographs that are

part of the Museum’s Digital Collections. Students can find relevant oral histories and photographs

by searching the Collections at http://www.ww2online.org/advanced and entering either “atomic bomb,”

“Hiroshima,” or “Nagasaki” in the search field. Of particular note are the photos of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki after the bombing as well as the oral-history interviews with Enola Gay navigator Theodore

“Dutch” Van Kirk and Manhattan Project scientist Lawrence Johnston. An excerpt from Johnston’s

interview is also included in the online materials accompanying this curriculum volume.

TEACHER

86

ATOMIC BOMBS

The War in the Pacific

LESSON PLAN

“I was a twenty-one-year-old second lieutenant of infantry leading a rie platoon

. . . When the atom bombs were dropped and news began to circulate that ‘operation

Olympic’ would not, after all, be necessary, when we learned to our astonishment

that we would not be obliged in a few months to rush up the beaches near Tokyo

assault-ring while being machine-gunned, mortared, shelled, for all the practiced

phlegm of our tough facades we broke down and cried with relief and joy. We were

going to live. We were going to grow to adulthood after all. The killing was all

going to be over, and peace was actually going to be the state of things.”

Paul Fussell, “Thank God for the Atomic Bomb,” The New Republic, August 26–29, 1981.

“A year after the bomb was dropped, Miss Sasaki was a cripple; Mrs. Nakamura

was destitute; Father Kleinsorge was back in the hospital; Dr. Sasaki was not

capable of the work he once could do; Dr. Fujii had lost the thirty-room hospital

it took him many years to acquire, and had no prospects of rebuilding it; Mr.

Tanimoto’s church had been ruined and he no longer had his exceptional vitality.

The lives of these six people, who were among the luckiest in Hiroshima, would

never be the same. What they thought of their experiences and of the use of the

atomic bomb was, of course, not unanimous. One feeling they did seem to share,

however, was a curious kind of elated community spirit, something like that of the

Londoners after the blitz—a pride in the way they and their fellow-survivors had

stood up to a dreadful ordeal.”

John Hersey, Hiroshima (1946).

“War has grown steadily more barbarous, more destructive, more debased. Now,

with the release of atomic energy, man’s ability to destroy himself is nearly

complete.”

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb,” Harper’s, February 1947.

EXTENSION/ENRICHMENT

• In order to have students explore the ethical dimensions of the atomic bombs and the responsibility

of historians to weigh ethical considerations when interpreting the past, ask them to compare the

following statements:

87

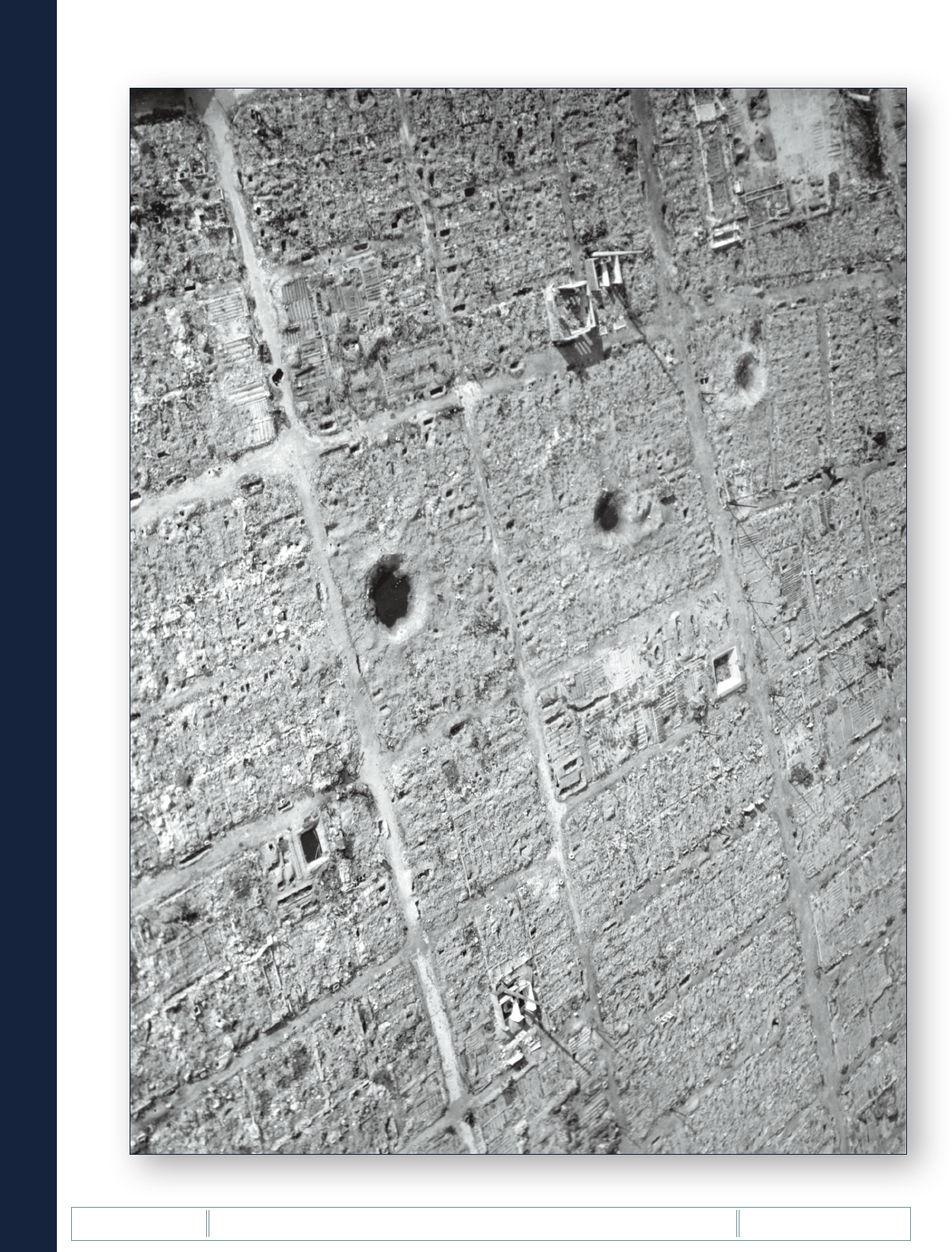

Osaka, Japan, following American firebombing, June 1, 1945.

(Image: National Archives and Records Administration, 342-FH-3A-3773.)

ATOMIC BOMBS

The War in the Pacific

LESSON PLAN

TWO INTERPRETATIONS OF THE ATOMIC BOMB

INTERPRETATION 1

“This essay suggests that, given the intransigence of the Japanese military, there

were few ‘missed opportunities’ for earlier peace, and that the alternatives available

to President Truman in the summer of 1945 were limited. In the end, Japan needed

‘external pressure’ in the form of the atomic bombs for its government to decide

to surrender.”

Sadao Asada, “The Shock of the Atomic Bomb and Japan’s Decision to Surrender: A Reconsideration,” Pacic Historical

Review 67, no. 4 (1998): 477–512.

INTERPRETATION 2

“The choices for the Truman administration in 1945 were not simply the A-bomb

versus invasion, or even the A-bomb and invasion. There were other strategies,

both diplomatic and military, that the administration—had it desired—might have

chosen instead of the atomic bombing. It was important to realize that the

administration had felt no desire to avoid using the A-bomb and thus did not seek

ways by early August to end the war without the atomic bombing.”

Barton J. Bernstein, “Introducing the Interpretive Problems of Japan’s 1945 Surrender: A Historiographical Essay on Recent

Literature in the West,” in The End of the Pacic War: Reappraisals, ed. Tsuyoshi Hasegawa (Stanford: Stanford

University Press, 2007).

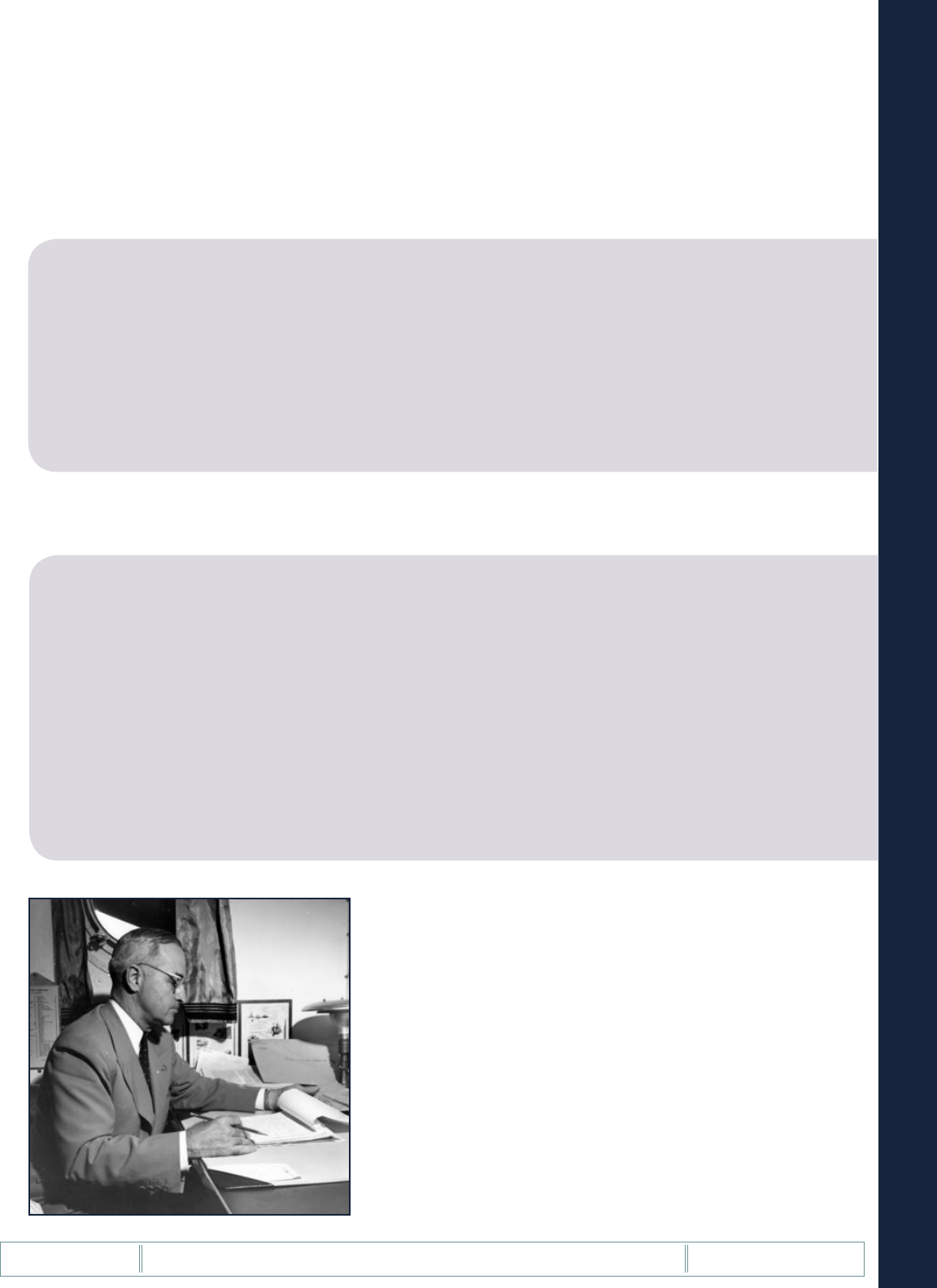

Returning from the Potsdam Conference, President Harry S.

Truman prepares his “report to the nation” aboard the USS

Augusta, August 6, 1945.

(Image: United States Army Signal Corps. Harry S. Truman Library & Museum, 63-1453-47.)

88

ATOMIC BOMBS

The War in the Pacific

LESSON PLAN

Osaka, Japan, following American firebombing, June 1, 1945.

(Image: National Archives and Records Administration, 342-FH-3A-3773.)

89

ATOMIC BOMBS

The War in the Pacific

LESSON PLAN

This map, produced after the war, shows the extent of the damage inflicted upon Japanese cities as a result of US B-29

firebomb attacks. For comparison, each Japanese city is paired with a US city of approximately the same size.

(Image: Oce of War Information.)

90

ATOMIC BOMBS

The War in the Pacific

LESSON PLAN

As the United States prepared for Operation Downfall, the largest amphibious operation ever planned, Japan initiated a massive troop buildup to

defend its home islands. (Image: The National WWII Museum.)

91

ATOMIC BOMBS

The War in the Pacific

LESSON PLAN

INTERPRETATION 1

Directions: For each primary or secondary source that you examine, record any evidence that you

believe supports the interpretation below. For each piece of evidence you record, write a brief

explanation of how or why it supports the interpretation. Ask for an additional copy of this sheet if

you run out of space.

Interpretation: “This essay suggests that, given the intransigence of the Japanese military, there were

few ‘missed opportunities’ for earlier peace and that the alternatives available to President Truman

in the summer of 1945 were limited. In the end, Japan needed ‘external pressure’ in the form of the

atomic bombs for its government to decide to surrender.”

Sadao Asada, “The Shock of the Atomic Bomb and Japan’s Decision to Surrender: A Reconsideration,” Pacic Historical Review 67, no. 4 (1998): 477–512.

EVIDENCE

1:

Explanation:

2:

Explanation:

3:

Explanation:

4:

Explanation:

5:

Explanation:

STUDENT WORKSHEET

YOUR NAME: DATE:

92

ATOMIC BOMBS

The War in the Pacific

LESSON PLAN

INTERPRETATION 2

Directions: For each primary or secondary source that you examine, record any evidence that you

believe supports the interpretation below. For each piece of evidence you record, write a brief

explanation of how or why it supports the interpretation. Ask for an additional copy of this sheet if

you run out of space.

Interpretation: “The choices for the Truman administration in 1945 were not simply the A-bomb

versus invasion, or even the A-bomb and invasion. There were other strategies, both diplomatic and

military, that the administration—had it desired—might have chosen instead of the atomic bombing.

It was important to realize that the administration had felt no desire to avoid using the A-bomb and

thus did not seek ways by early August to end the war without the atomic bombing.”

Barton J. Bernstein, “Introducing the Interpretive Problems of Japan’s 1945 Surrender: A Historiographical Essay on Recent Literature in the West,”

in The End of the Pacic War: Reappraisals, ed. Tsuyoshi Hasegawa (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007).

EVIDENCE

1:

Explanation:

2:

Explanation:

3:

Explanation:

4:

Explanation:

5:

Explanation:

STUDENT WORKSHEET

YOUR NAME: DATE: