Manhattan Project

National Park Service

U.S. Department of Interior

Manhattan Project National

Historical Park– Oak Ridge

Tennessee

U.S. Involvement in World War II Through the Lens of the

Manhaan Project Naonal Historic Park in Oak Ridge, TN

Grades: 9-12

Stage 1: Desired Results:

Understandings:

Students will understand that…

Students will understand that the Manhaan Project in Oak Ridge was a secret city that help enrich uranium

used in the bomb on Hiroshima.

Students will understand that the story of Oak Ridge and the work people did there during the war impacted

the course of the war, world history, and US history.

Essenal Quesons:

What impacts did the Manhaan Project in Oak Ridge have locally?

How did the development of nuclear weapons inuence history aer WWII?

What was the role of the Manhaan project in the U.S. and the world?

What were the experiences of women in the Manhaan Project? How does this relate to experiences of

women all over the US?

What where the experiences of African-Americans in the Manhaan Project? How does this relate to

experiences of African-Americans all over the US? How were the experiences of African-American’s inuenced

by the locaon of the Manhaan Project in Oak Ridge within the context of the south at that me?

1

Stage 2 – Assessment Evidence:

Performance tasks:

Pre-Assessment:

Teachers may want to use their own pre-assessment based on their students’ abilies and needs.

Stage 3—Learning Plan:

Learning Acvies:

Preparaon:

Materials: This learning unit consists of 7 learning acvies and is organized around dierent aspects of the

Manhaan Project based on primary documents, photos, excerpts, war posters, and other sources. Learning

goals for each acvity as well as suggested acvies and suggested sources will be provided at the beginning

of each secon.

Acvity 1: Entering the War

Acvity 2: Choosing Oak Ridge

Acvity 3: Displacement from Communies

Acvity 4: Women in the Manhaan Project at Oak Ridge

Acvity 5: African-Americans in the Manhaan Project in Oak Ridge

Acvity 6: Sacrice in the Secret City

Acvity 7: Dropping the Bombs

2

Acvity 1—Entering the War:

Objecves:

Students will understand movaon for starng the Manhaan Project was spurred by fears that Germany

was developed atomic weapons.

Direcons:

Have students read the background informaon about possible reasons that lead to the implementaon of

the Manhaan Project. Have students also reach the primary document, a leer from Albert Einstein to US

President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Suggested Acvity:

Think-pair-share. Give students think me to read and annotate the leer and start to answer quesons.

The leer can be also read together as a class. Have students pair and answer quesons. Share out answers

in a whole group discussion.

Sources:

Foundaon Document: Manhaan Project Naonal Historical Park, Tennessee, New Mexico, Washington,

January 2017 (pages 8-9). Access online: hps://www.nps.gov/mapr/foundaon-document.htm

Other Suggested Sources:

The Manhaan Project, Part 1, Department of Energy podcast, Direct Current.

hps://energy.gov/podcasts/direct-current-energygov-podcast/s2-e2-manhaan-project-part-1

Kelly’s, The Manhaan Project is organized into secons and within the secons shorter experts that

relate to specic topics. Each part is around 1-4 pages and could be used in a high school classroom

seng. For background on sciensts pushing for the project see “Thinking No Pedestrian Thoughts”

on p. 19, “Enlisng Einstein” on p. 38, and “Albert Einstein to F.D. Roosevelt” on p. 42.

Kelley, Cynthia C., The Manhaan Project: The Birth of the Atomic Bomb in the Words of Its

Creators, Eyewitnesses, and Historians. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. 2009.

3

Read This: Background Informaon

Science Background Leading to the Manhaan Project (excerpts from The Foundaon Document, p. 8-9)

“The road to the atomic bomb began with revoluonary discoveries in physics. In the early 20th century, physicists

conceived of the atom as a miniature solar system, with extremely light negavely charged subatomic parcles, called

electrons, in orbit around a much heavier posively charged nucleus.

In 1919, Ernest Rutherford, working in the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge University, detected a high-energy

parcle with a posive charge being ejected from the nucleus of an atom. He named this subatomic parcle the

proton. The number of protons in the nucleus of the atom denes the element. Hydrogen, with one proton and an

atomic number of one, came rst on the periodic table and uranium, with ninety-two protons, last. However, many

elements existed at dierent weights even while displaying idencal chemical properes. This discovery would have

important implicaons for nuclear physics, as these isotopes of the same element could have markedly dierent

nuclear properes.

A third subatomic parcle, rst idened in 1932 by James Chadwick at Cambridge University, explained this

dierence in mass. Named the neutron because it has no charge, the number of neutrons could vary among nuclei of

atoms of the same element. Atoms of the same element but with varying numbers of neutrons are called isotopes.

For instance, all uranium atoms have 92 protons in their nuclei and 92 electrons in orbit. Uranium–238, which

accounts for more than 99% of natural uranium, has 146 neutrons in its nucleus. Uranium–235 has 143 neutrons in its

nucleus, and this isotope makes up less than 1% of naturally occurring uranium.

An unexpected discovery by researchers in Nazi Germany in late 1938 radically changed the direcon of both

theorecal and praccal nuclear research. The radiochemists Oo Hahn and Fritz Strassmann found that when they

bombarded uranium with neutrons emied from a mixed radium-beryllium source, the products of the experiment

weighed less than that of the original uranium atom. Albert Einstein’s formula, E=mc2, which states that mass and

energy are equivalent, suggested the loss of mass resulng from this process must have been converted into energy.

Hahn communicated these ndings to Lise Meitner, a former colleague who ed to Sweden to escape the Nazis.

Meitner and her nephew, Oo Frisch, calculated that the nucleus of the uranium atom had been split, creang two

lighter elements. They concluded that so much energy had been released that a previously undiscovered process

must be at work. Borrowing the term for cell division in biology, Frisch named the process ssion.

Fission of the uranium atom had another important characterisc besides the immediate release of energy. This was

the emission of neutrons. When ssion occurred in uranium, spling the atom, several neutrons were also emied.

Physicists speculated that these secondary neutrons might collide with other uranium atoms and cause addional

ssion, creang a self-sustaining “chain reacon” if the mass of uranium was of appropriate size, shape, and density,

which would emit a connuously increasing amount of energy. Such a reacon could generate a large amount of

energy, and if uncontrolled could create an explosion of huge force.

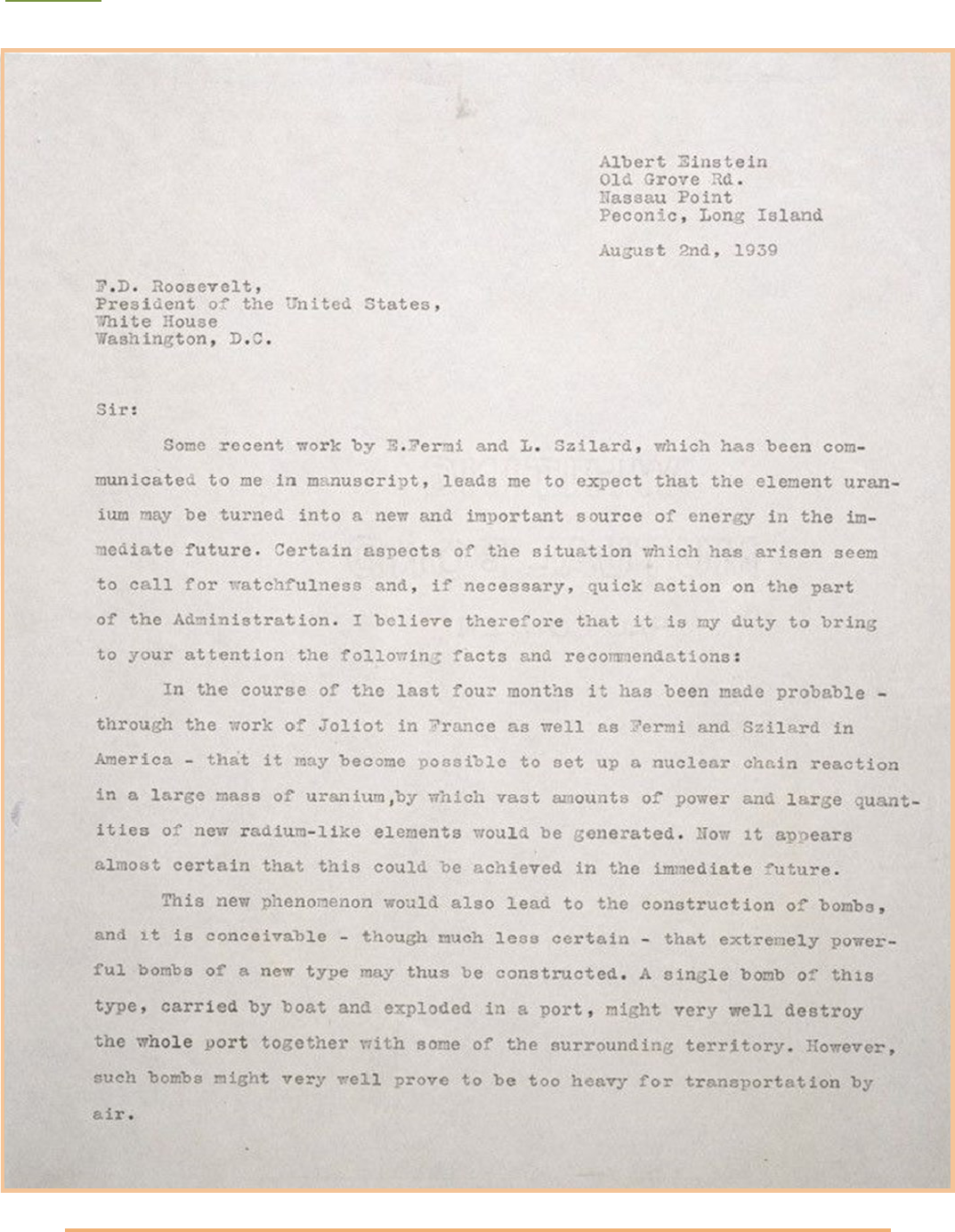

The possible military uses for uranium ssion were apparent to the world’s leading physicists. In August 1939, Albert

Einstein and physicist Leo Szilard wrote a leer to President Franklin D. Roosevelt to warn him that recent uranium

ssion research suggesng a chain reacon in a suciently large mass of uranium could conceivably lead to the

construcon of “extremely powerful bombs.” A single bomb, Einstein warned, could potenally destroy an enre

seaport. Einstein called for government support of uranium research, nong ominously that German physicists were

engaged in uranium research and that Germany had stopped the export of uranium.”

4

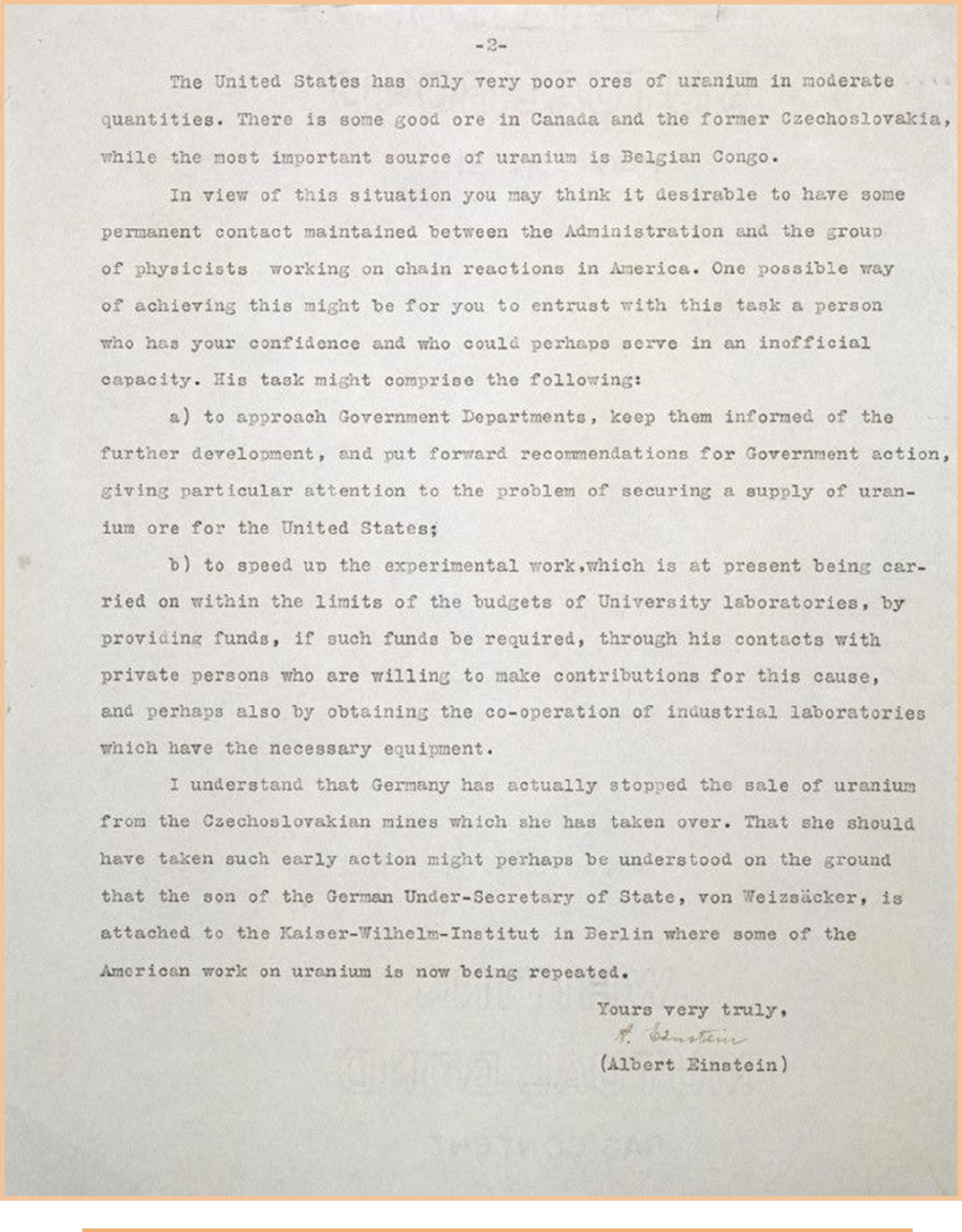

Read This: Leer from Albert Einstein Below is copy of the Einstein-Szilard leer to President Franklin Delano

Roosevelt. Annotate the leer for important informaon. Then answer the quesons that follow.

5

6

Answer it: Einstein-Szilard leer to President FDR Quesons.

Answer the quesons below.

1. Einstein menons the work of (E.) Fermi, (L.) Szilard and (Frederic Joliot-Curie) Joliot. State who each of these

people are and why they might be notable or important within the context of this leer.

2. Einstein was not the sole writer of this this leer. The idea to send a leer came from mulple. It was also

composed by Leo Szilard. Why did you suppose they did not write their own leers and sign them? Why ask

Albert Einstein to sign and send the leer?

3. What does the leer warn of?

4. How does Einstein imagine such a weapon will be used? Why?

5. Why does he menon where to nd uranium sources?

6. What is the signicance of uranium in the former Czechoslovakia?

7. Who does he suggest geng in contact with?

8. What acons does he recommend taking? Name at least two acons.

9. What does he menon that Germans have done with the Czechoslovakian uranium mines?

10. What do you think the leer implies about possible German intenons and acons? Explain.

11. Speculate to how President Roosevelt might have felt upon receiving and reading the leer.

7

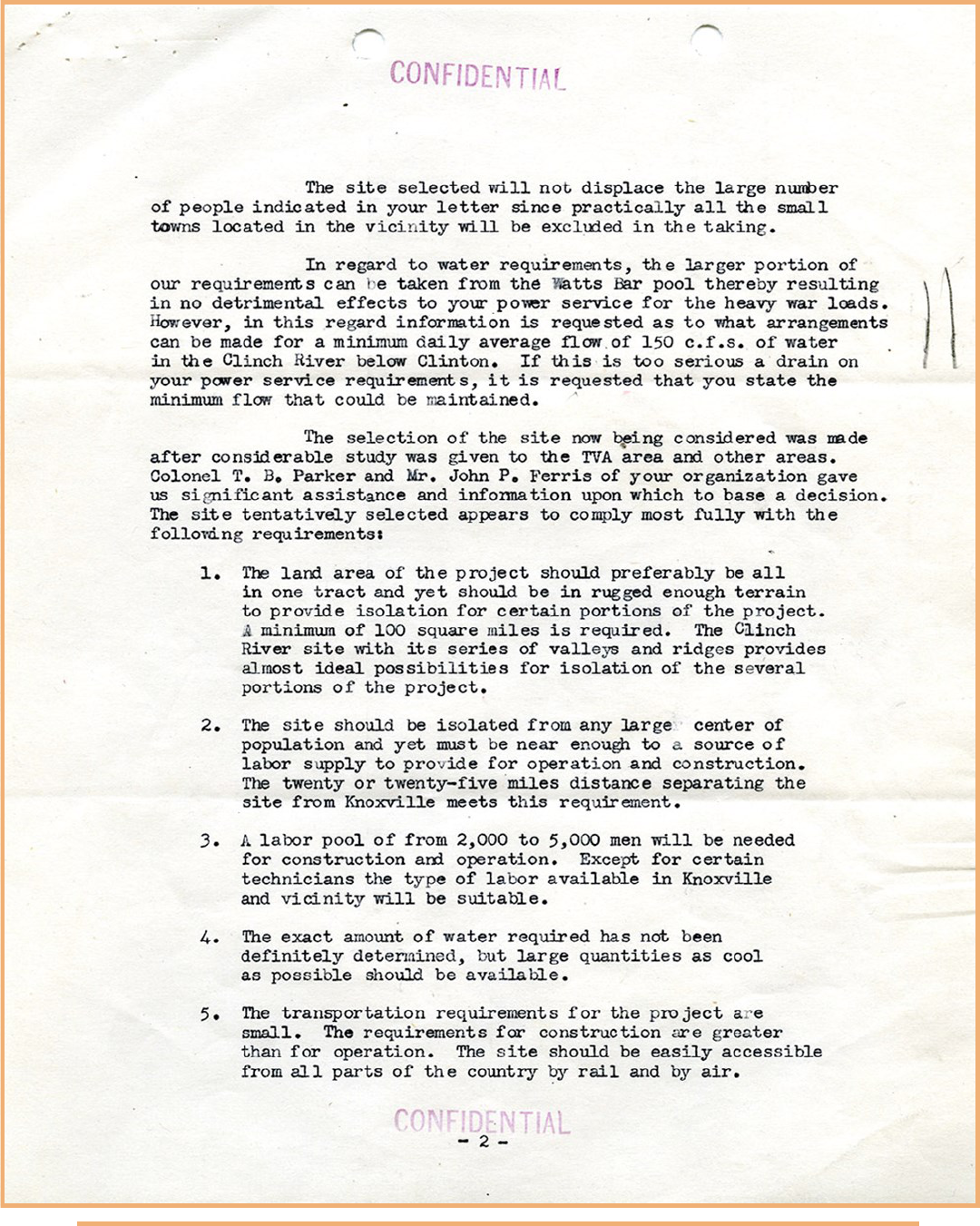

Acvity 2—Choosing Oak Ridge:

Objecves:

Students will be able to state reasons why the Oak Ridge locaon was chosen as the site for one of the

Manhaan Project secret cies.

Direcons:

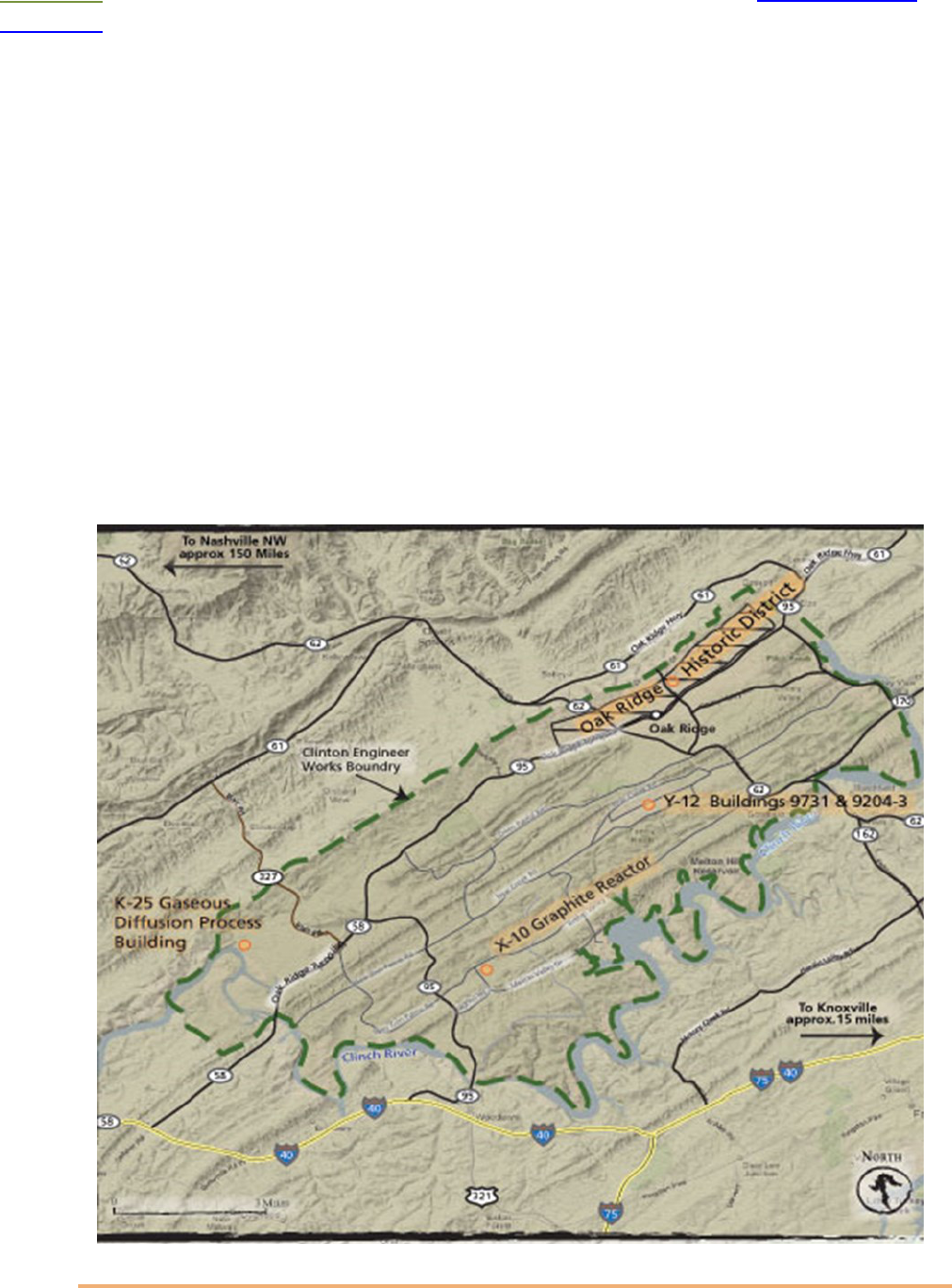

Have students read the excerpt from the NPS website, analyze map, and read primary document, a leer

from the War Department to the TVA. Then students will ll out a Venn diagram and answer quesons.

Suggested Acvity:

Have students read the documents individually or whole group. Give student me to annotate the texts.

Have students work in groups of 2-4 to ll in the Venn diagram and answer the quesons.

Sources:

Map and selected text about the Oak Ridge tract of land was taken from the NPS website.

Oak Ridge site – Manhaan Project Naonal Historic Park webpage, Accessed September 2, 2017.

www.nps.gov/mapr/oakridge.htm

Historic document from the War Department to the TVA was accessed thought the Atlanta Naonal

Archives.

Selecon of the Oak Ridge Site, Naonal Archives Atlanta, Accessed September 2, 2017.

hps://www.archives.gov/atlanta/exhibits/item91_exh.html

Other Suggested Sources:

“City Behind a Fence” is about Oak Ridge from 1942-1946. For short excerpts about choosing the Oak

Ridge locaon and early city planning see chapter 1 and pages 3-10.

Johnson, Charles W. and Jackson, Charles O.. City Behind a Fence. The University of Tennessee Press.

1981.

8

Read This: excerpt from the Manhaan Project Naonal Historical Park website www.nps.gov/mapr/

oakridge.htm Read the informaon, analyze the map, read the leer aer, then answer the quesons.

The Clinton Engineer Works, which became the Oak Ridge Reservaon, was the administrave and military

headquarters for the Manhaan Project and home to more than 75,000 people who built and operated the

city and industrial complex in the hills of East Tennessee.

The Oak Ridge Reservaon included three parallel industrial processes for uranium enrichment and

experimental plutonium producon.

The Oak Ridge site includes

X-10 Graphite Reactor Naonal Historic Landmark, a pilot nuclear reactor which produced small

quanes of plutonium;

Buildings 9731 and 9204-3 at the Y-12 complex, home to the electromagnec separaon process for

uranium enrichment;

K-25 Building site, where gaseous diusion uranium enrichment technology was pioneered. Buildings

9731, 9204-3 and K-25 together enriched a poron of the material for the uranium bomb.

9

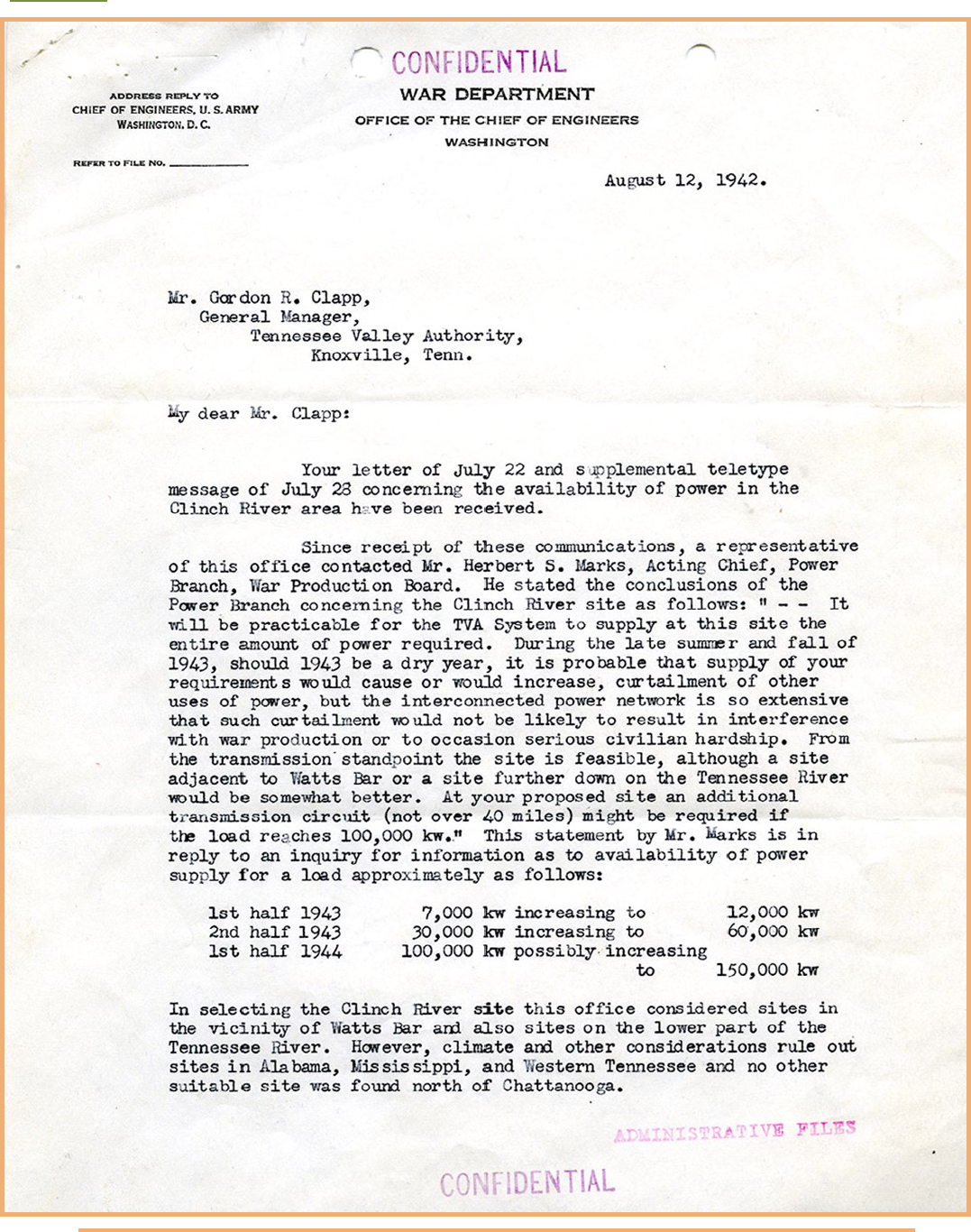

Read This: War Department—TVA Leer Choosing Clinch River Site

10

11

12

Fill in the Venn diagram with reasons why the Oak Ridge locaon was chosen. Then answer the quesons.

1.

Geographic/Natural Consideraons

Civilian/Man

-

Made Consideraons

2. What two types of natural land features create the boarders of secret city?

3. In the leer refers to the “Clinch River site,” what would this site become?

4. Why do you think it would be important to choose a semi-secluded area?

5. What is the Tennessee Valley Authority? How does this e to earlier U.S. history? Explain.

6. What is unique about the Clinch River area relave to the following areas

Power water, land requirement?

7. What city is far enough away for some seclusion but close enough to recruit labor?

13

Acvity 3—Displacement from Communies:

Objecves:

Students will understand that the Manhaan Project site at Oak Ridge was composed of several small rural

communies. Students will understand that the people living there were displaced and sacriced a great deal for the

war eort.

Direcons:

Have students read the excerpt from the Foundaon Document. Students may work in groups of 2-4. Students will

answer the quesons and write capons for each of the photos. Show students the photos with the actual capons

aer they have shared their capons with the whole group. Have students choose 2+ photos to make more inferences

from. Then read the displacement leer.

Suggested Acvity:

Read expert about the communies in class. Have students use the crop method for analyzing photos. And share out

to the whole group. Have students read the displacement leer and compose a leer to a relave or friend about

what is happening and how the feel.

Sources:

Text excerpts from the Foundaon Document on the NPS Manhaan Project website.

Foundaon Document: Manhaan Project Naonal Historic Park, Tennessee, New Mexico, Washington, January

2017. (page 5) Access online: hps://www.nps.gov/mapr/foundaon-document.htm

Photos are from the Department of Energy in Oak Ridge Flicker webpage and it appropriate for students to

explore.

Before Oak Ridge, Department of Energy Flicker page. Accessed September 2, 2017. www.ickr.com/photos/doe-

oakridge/albums/72157669441168194

Other Suggested Sources:

“City Behind a Fence” is about Oak Ridge from 1942-1946. For wring about displacement of communies that is

appropriate for classroom use see pages 39-43.

Johnson, Charles W. and Jackson, Charles O.. City Behind a Fence. The University of Tennessee Press. 1981.

Reba Holmberg’s Interview with the Voices of the Manhaan Project. Reba grew up the in community of

Robertsville her family was displaced by the Manhaan Project. She later worked at the Y-12 analycal labs.

hp://manhaanprojectvoices.org/oral-histories/reba-holmbergs-interview

Capon Key

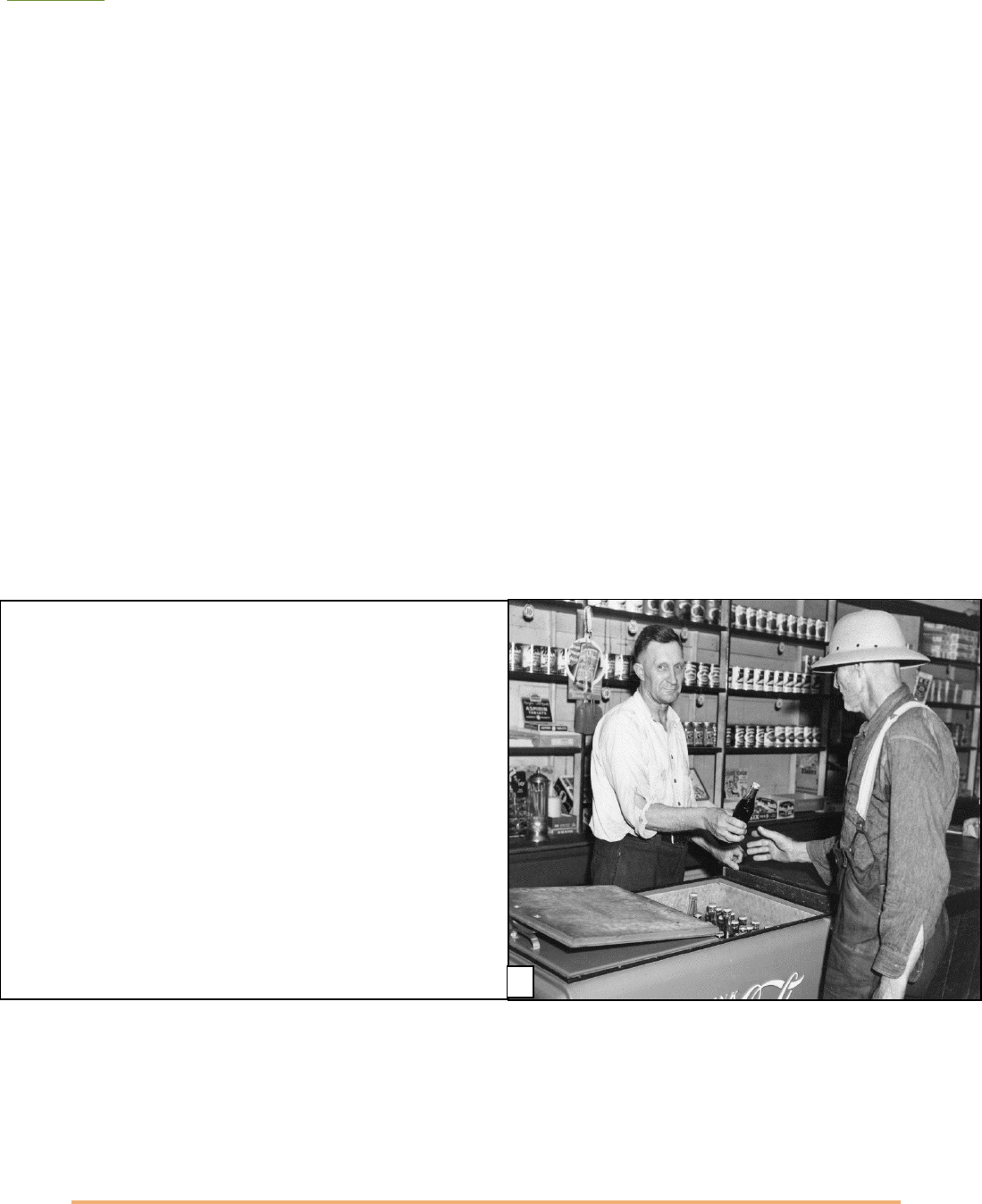

Photo 1: 6-25-1938 McKinney Cross-roads Store in the Wheat Community, Tennessee

Photo 2: Uncle Charlie McKinney with mules 1938, Wheat

Photo 3: Ina Lee Gallaher, Wheat Tennessee

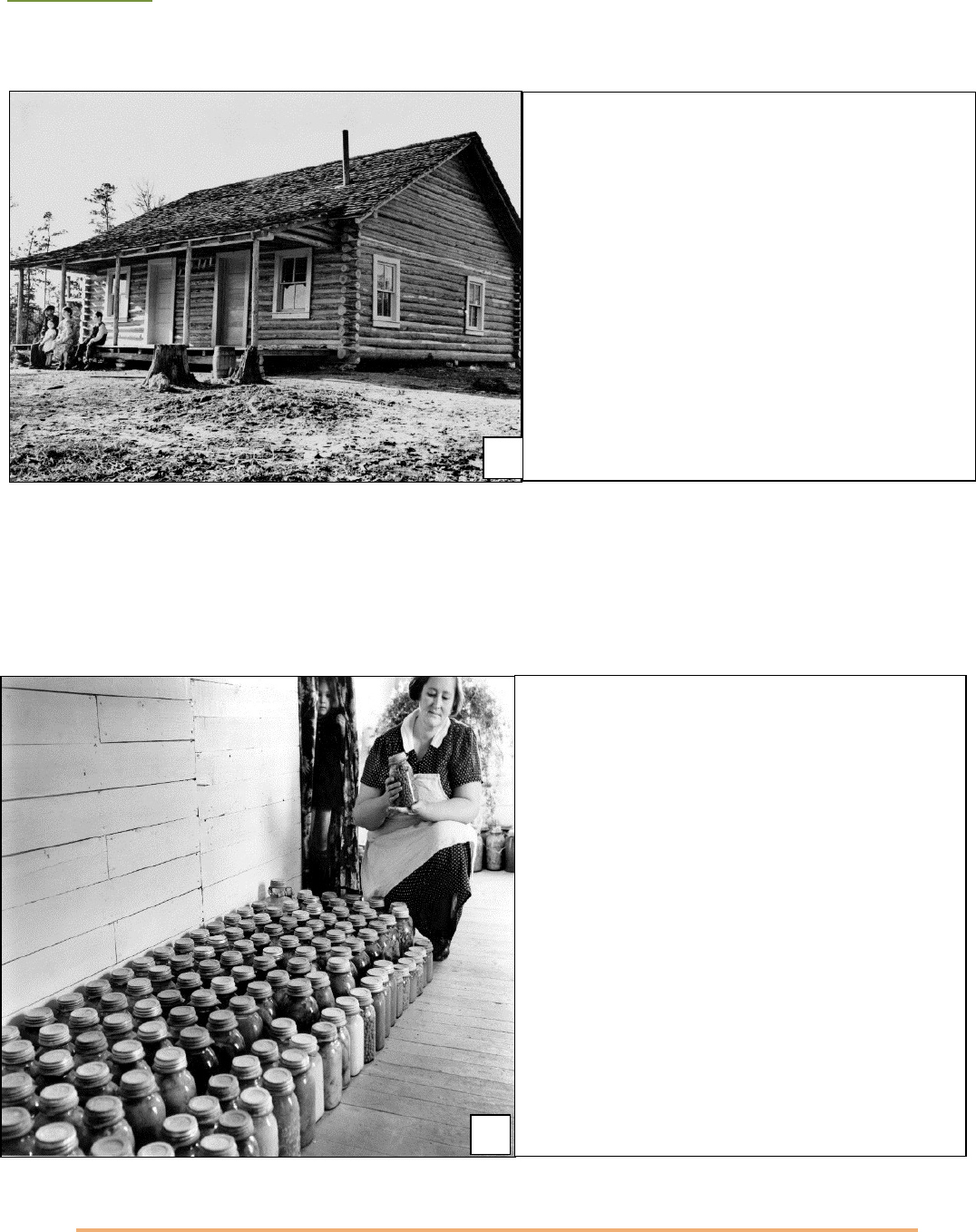

Photo 4: Edmonds Home 1939 Wheat Tennessee

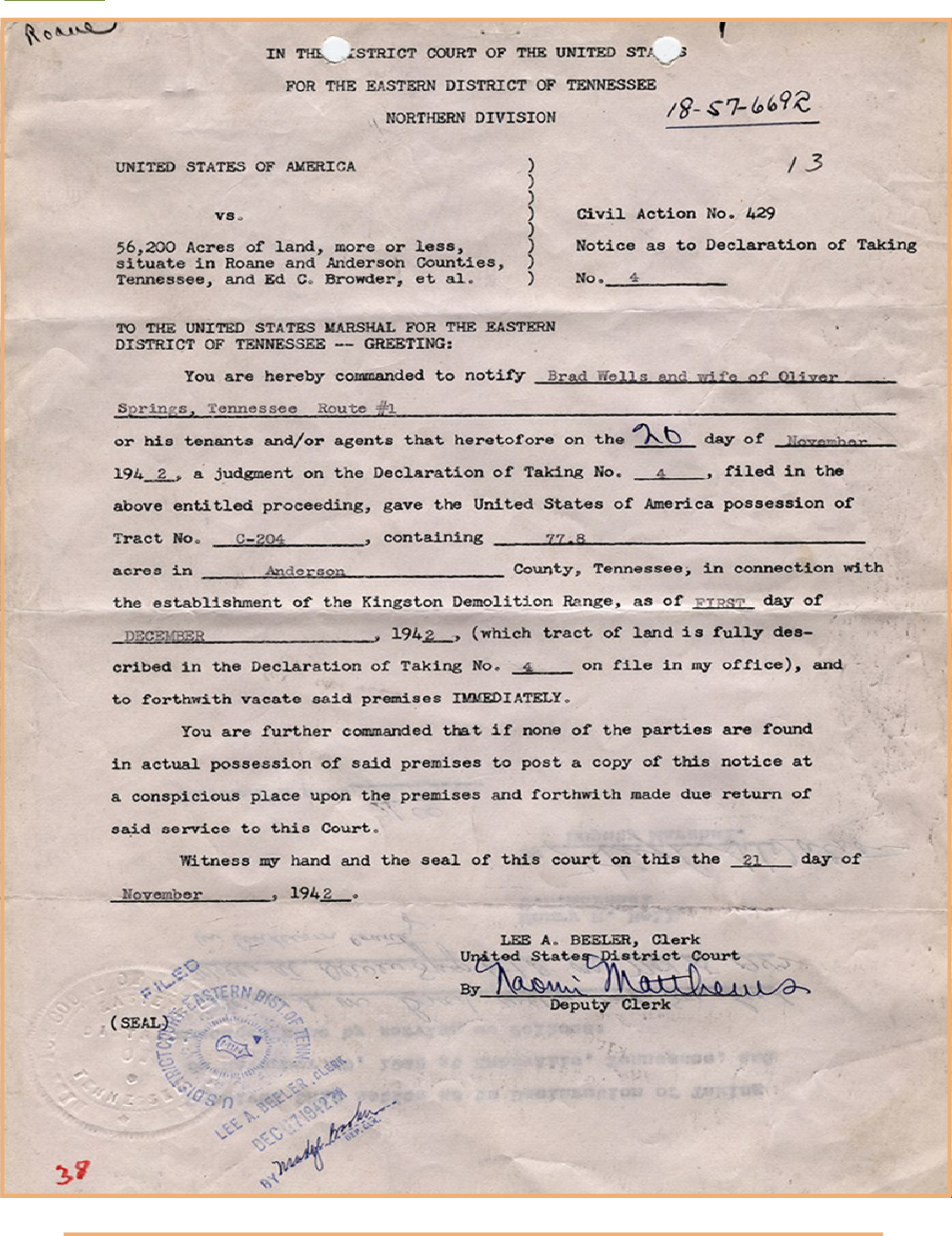

Photo 5: Woman canning in Wheat 1939

14

Read This: Excerpt from the Manhaan Project Naonal Historical Park Foundaon document.

Analyze the pictures of Wheat residents taken by Ed Westco, then read the displacement leer and

answer the quesons.

“The area making up the Oak Ridge Reservaon includes evidence of human selement dang back at least 14,000

years, long prior to the creaon of the Clinton Engineer Works. Various American Indian tribes seled the area.

European selement began in what is now East Tennessee when the Long Hunters arrived in the second half of the

1700s. Subsequently, waves of selers followed, including many Scots-Irish. By 1942, the nearly 60,000 acres along

the north bank of the Clinch River taken for the Manhaan Project were occupied by a few sparsely populated

farming communies in three valleys only a few tens of miles west of Knoxville. These communies included

Scarborough (known as Scarboro by 1942), the Wheat community, Robertsville, New Bethel, New Hope, and Elza.

The Tennessee Valley Authority completed the Norris Dam in 1936 on the Clinch River, providing electricity and ood

control to the area and the project. In November 1942, approximately 3,000 people were required to be displaced in

very short order to make way for construcon of the Clinton Engineer Works. For a variety of reasons the locaon of

the Clinton Engineer Works was considered at the me ideal, and when General Leslie Groves was put in charge of the

Manhaan Project he selected the site as the locaon of the project’s rst plant. Interesng to note, Tennessee

Governor Prence Cooper inially declined to cede sovereignty over the land to the federal government, which gained

the Clinton Engineer District a military restricted area designaon rather than a military reservaon.”

Analyze the photos taken of the Wheat community. Answer the quesons and write detailed capons for each

Photo 1

Who is in the photo?

What is the seng?

What acvies are happening?

Capon:

1

15

Analyze These: Historic Photos

2

Photo 2

Who is in the photo?

What is the seng?

Capon:

3

Photo 3

Who is in the photo?

What is the seng, what is happening?

Capon:

16

Analyze These: Historic Photos

4

Photo 4

Who is in the photo?

What is the seng?

Capon:

5

Photo 5

Who is in the photo?

What is the seng?

What happen earlier that day?

Capon:

17

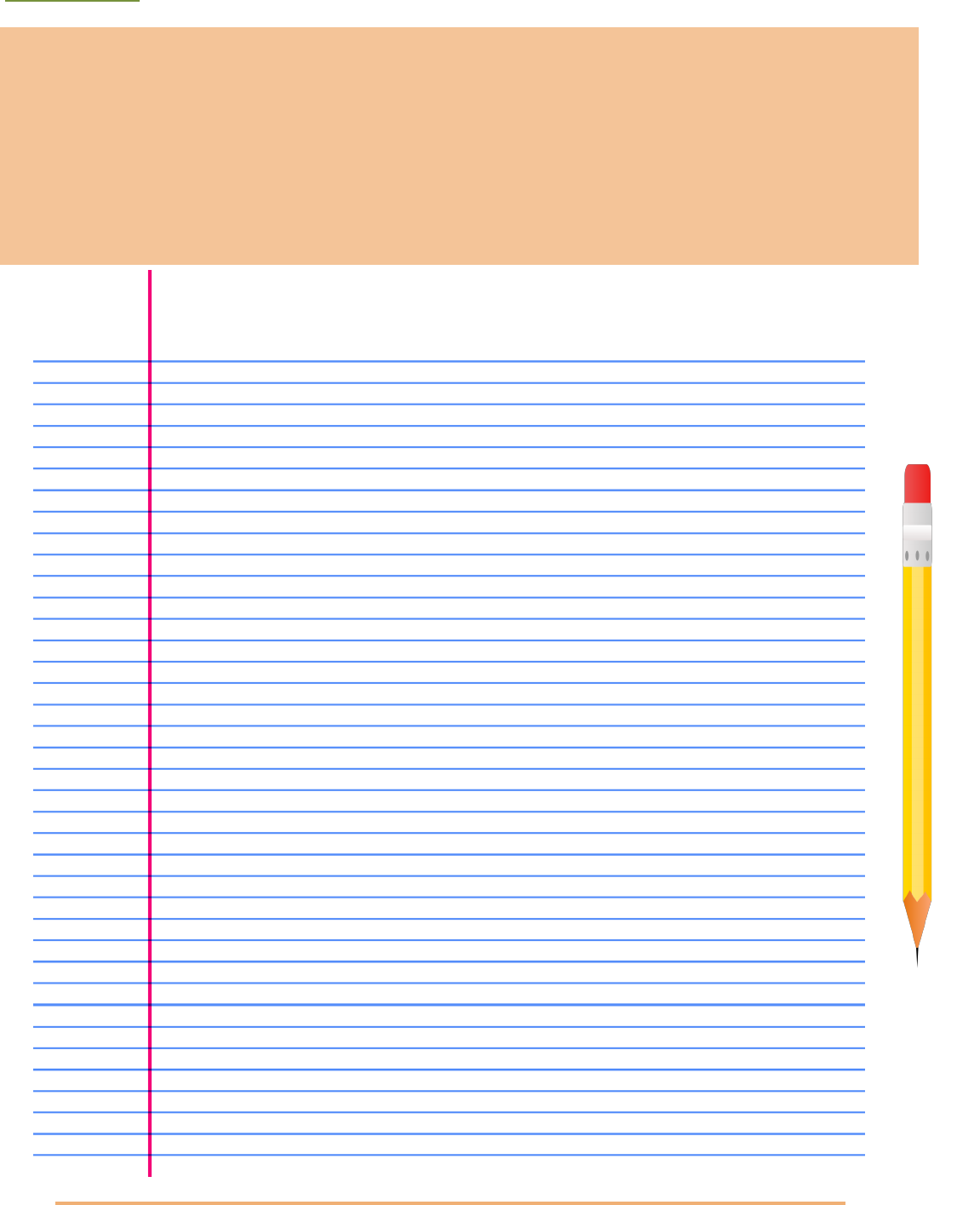

Read This: Displacement Leer

18

Write about it: Personal Leer

Imagine you are the head of household receiving this leer. You provide for your family from running your farm. You

have been told that the government needs the land for a project that will help end the war. Everyone wants to end

the war and bring their boys back home. Everyone in the community has been aected by the war and many people

have husbands, sons, brothers, and fathers that are away ghng. Your enre town is displaced.

Imagine that you will have to nd a place to stay for you and your family while you look for a new residence.

Compose a leer to a relave explaining what is happening to you and your family. What plans will have to make?

Where will you live? How will you move? What emoons is your family experiencing?

19

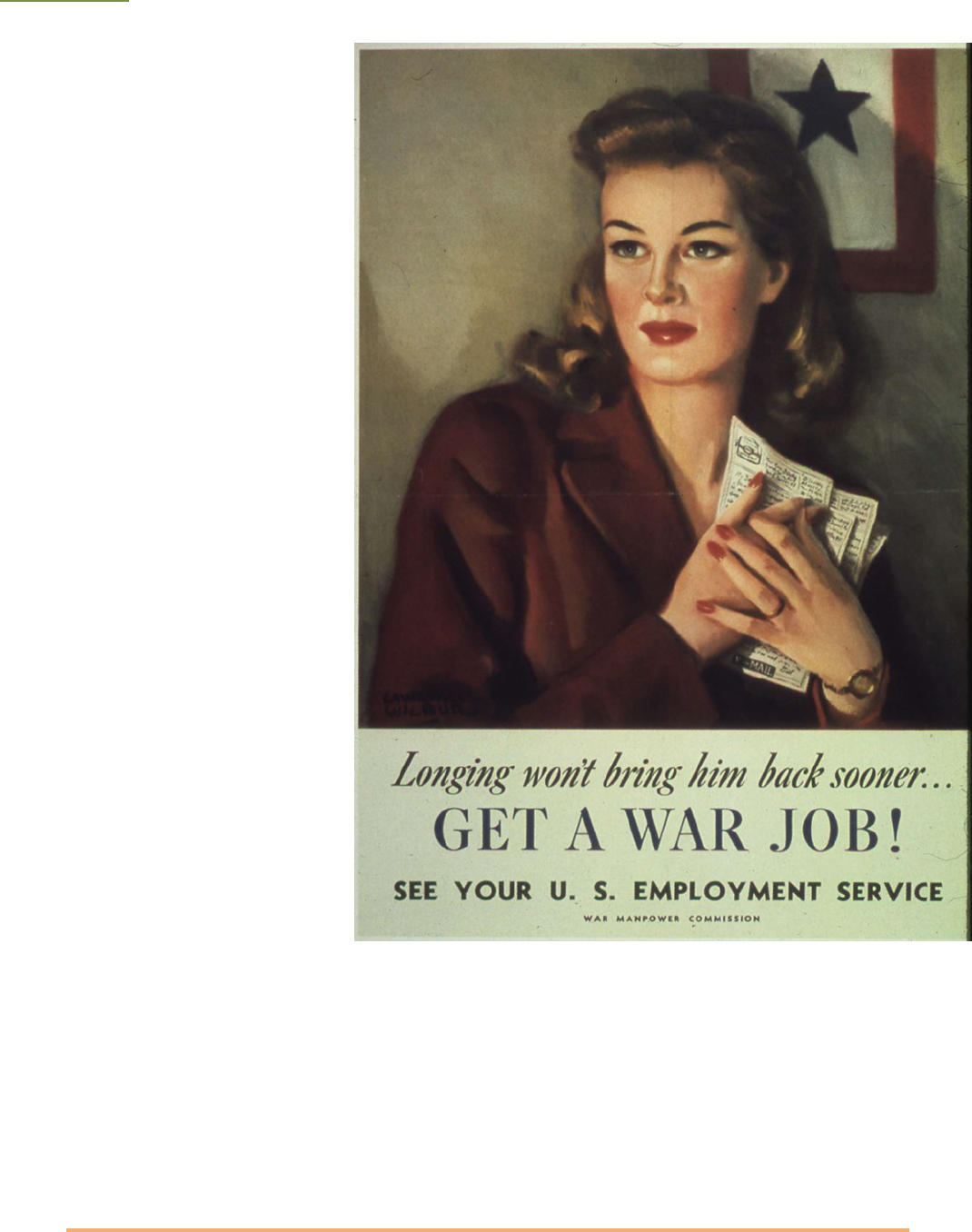

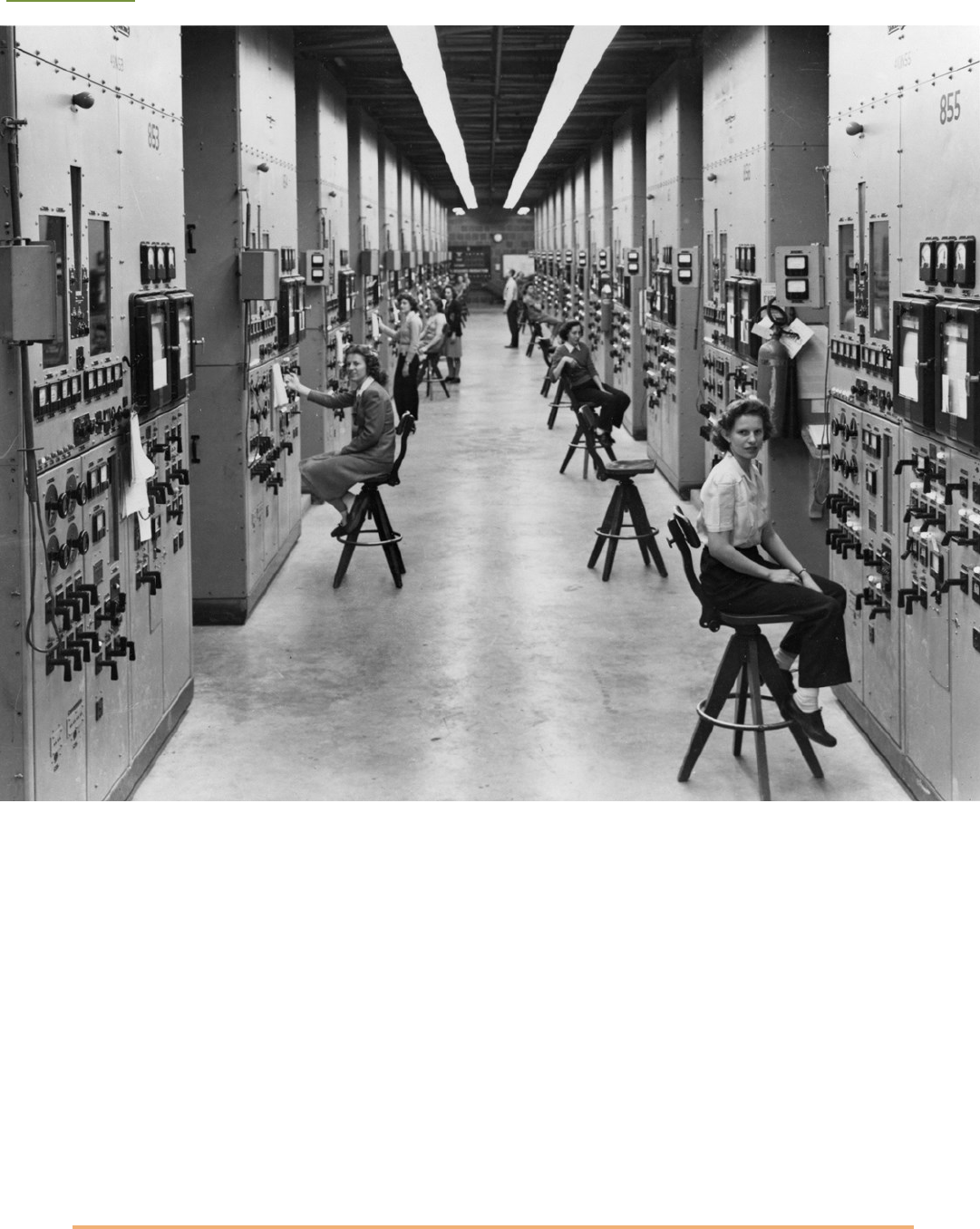

Acvity 4—Women in the Manhaan Project at Oak Ridge:

Objecves:

Students will understand that there was a shortage of manpower during the war and that women moved into jobs

that men typically held. There were many government and industry supported messages encouraging women to get

jobs and serve in roles that also supported the military.

Direcons:

Have students analyze the war message, and the photo of women working the Calutons at the Y-12 plant. Then have

students answer the quesons in groups of two, and then share out whole group.

Suggested Acvity:

Have students use the crop technique to analyze the image of the war poster. Students can answer quesons in pairs.

There are also video interviews from the Voices of the Manhaan Project to watch in class and discuss. The interview

with Colleen Black is under 40 minutes and she give details about living in Oak Ridge. She worked as a leak detector in

the K-25 gaseous diusion plant.

Sources:

Poster 44-PA-389; Get A War Job!; 1941 - 1945; World War II Posters, 1942 - 1945; Records of the Oce of

Government Reports, Record Group 44; Naonal Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. www.docsteach.org/

documents/document/get-a-war-job, July 5, 2017

Photos are from the Department of Energy in Oak Ridge Flicker webpage. Y-12 Oak Ridge 1940’s. Department of

Energy in Oak Ridge Flicker webpage www.ickr.com/photos/doe-oakridge/albums/72157669169100644/

with/9067043071/

Other Suggested Sources:

Colleen Black’s Interview with the Voices of the Manhaan Project Video in 2013. hp://

manhaanprojectvoices.org/oral-histories/colleen-black-interview-0

Evelyn Ellingson’s Interview. Voices of the Manhaan Project. hp://manhaanprojectvoices.org/oral-histories/

evelyn-ellingsons-interview

The Girls of Atomic City explores what it was like for women working in Oak Ridge during the Manhaan Project.

Kiernan, Denise. The Girls of Atomic City. Touchstone. 2013.

Female Sciensts of the Manhaan Project, Manhaan Project Naonal Historic Park webpage accessed

September 2, 2017. www.nps.gov/mapr/learn/historyculture/female-involvement-in-the-manhaan-project.htm

American Army Women Serving on All Fronts, a news real that is (not specically about Oak Ridge, but) about

women working for the war eort. American Army Women Serving on All Fronts, United News, news reel that is 9

min 17 sec. www.docsteach.org/documents/document/american-army-women

You’re Going to Employ Women, a government pamphlet to help employers learn how to employ and train

women. You’re Going to Employ Women, The War Department. 1943. www.docsteach.org/documents/

document/youre-going-to-employ-women

20

Analyze This: Warme message

1. Who is the adversement targeng?

2. Who is pung out this message?

3. What is the signicance of the ag

with the blue star?

4. What can we infer about the woman in

the adversement? Give evidence for

each statement. (Provide at least 3

things).

5. What do you think the poster is trying to accomplish?

6.Do you think this is an eecve message? Explain why or why not.

21

Analyze This: Historic Photo

1. Who is in the photo?

2. What is the seng?

3. What acvies are happening?

4. What else can you infer from the photo?

22

Acvity 5—African-Americans in the Manhaan Project:

Objecves:

Students will understand that African Americans came to work at Oak Ridge for beer paying jobs. However, African

Americans were restricted in the kinds of jobs they could get. They also lived under segregated condions.

Direcons:

Have students complete the photo analysis. Then have students read the excerpt from the Naonal Park website.

Suggested Acvity:

Students can use the crop technique to analyze photos.

Sources:

Photos are from the Department of Energy in Oak Ridge Flicker webpage. African American History Oak Ridge.

www.ickr.com/photos/doe-oakridge/albums/72157674674051596/with/7128930793/

African-American Involvement in the Manhaan Project webpage www.nps.gov/mapr/learn/historyculture/african-

american-involvement-in-manhaan-project.htm

Other Suggested Sources:

Kelly’s, The Manhaan Project is organized into secons and within the secons shorter experts that relate to

specic topics. Each part is around 1-4 pages and could be used in a high school classroom seng. For reading

about the experience of African Americans see “An answer to their prayers” on p. 210, and “All-black crews with

white foreman” on p. 214.

Kelley, Cynthia C., The Manhaan Project: The Birth of the Atomic Bomb in the Words of Its Creators,

Eyewitnesses, and Historians. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. 2009.

“City Behind a Fence” is about Oak Ridge from 1942-1946. For wring about African Americans look for references

to Scarboro, also see an excerpt on pages 210-215

Johnson, Charles W. and Jackson, Charles O.. City Behind a Fence. The University of Tennessee Press. 1981.

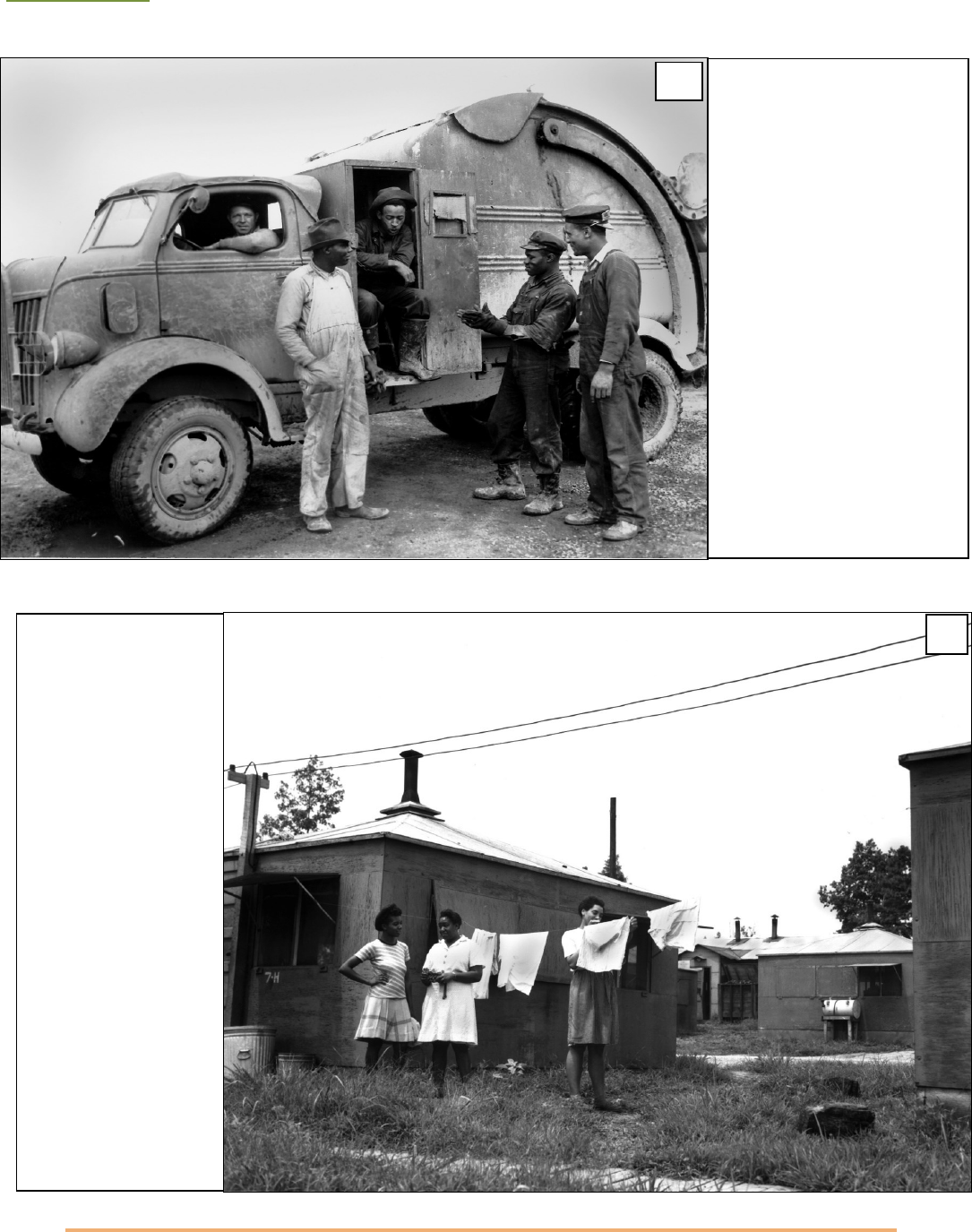

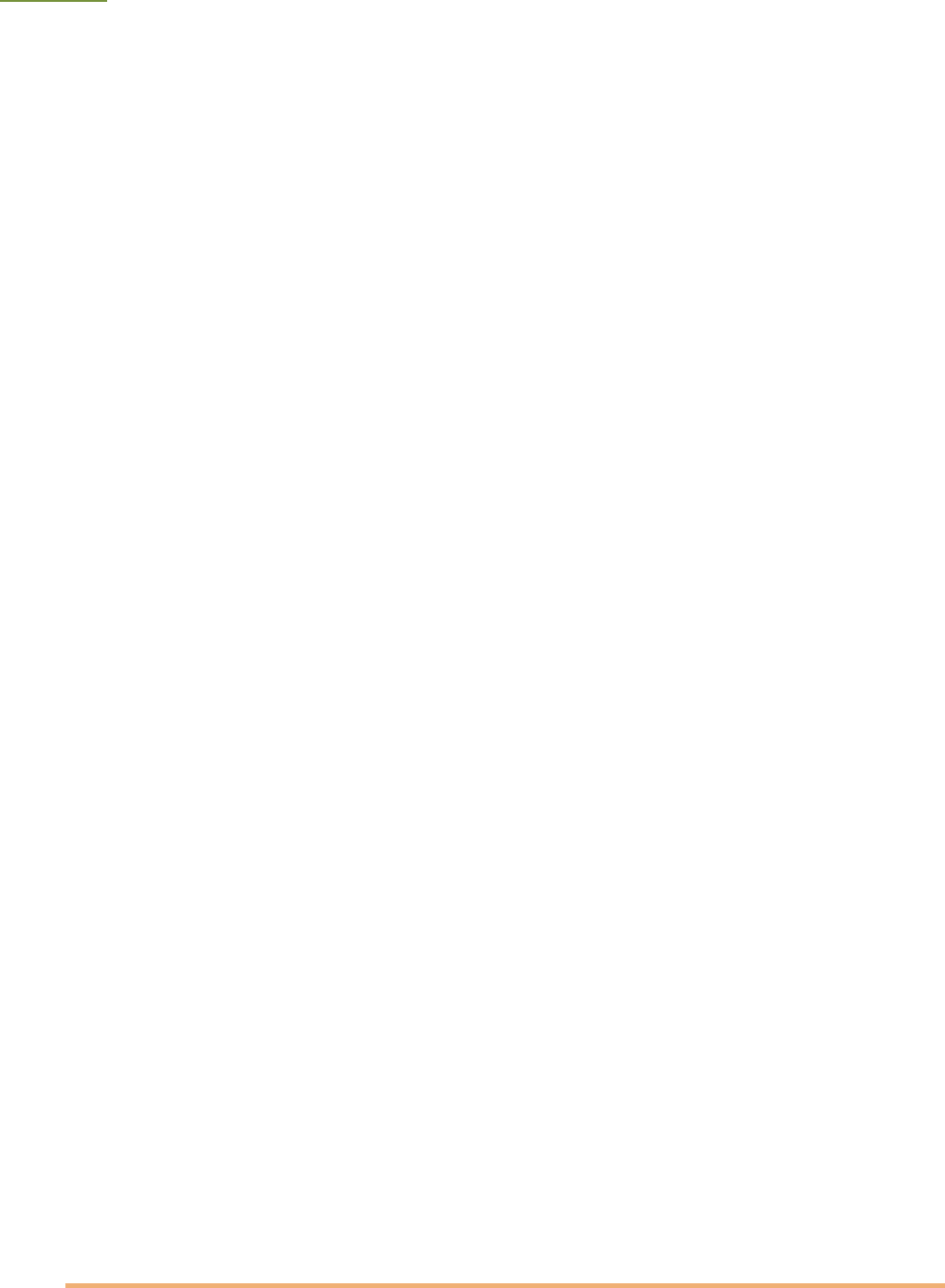

Photo 1: Men working garbage collecon at Oak Ridge. Driving jobs were reserved for

whites.

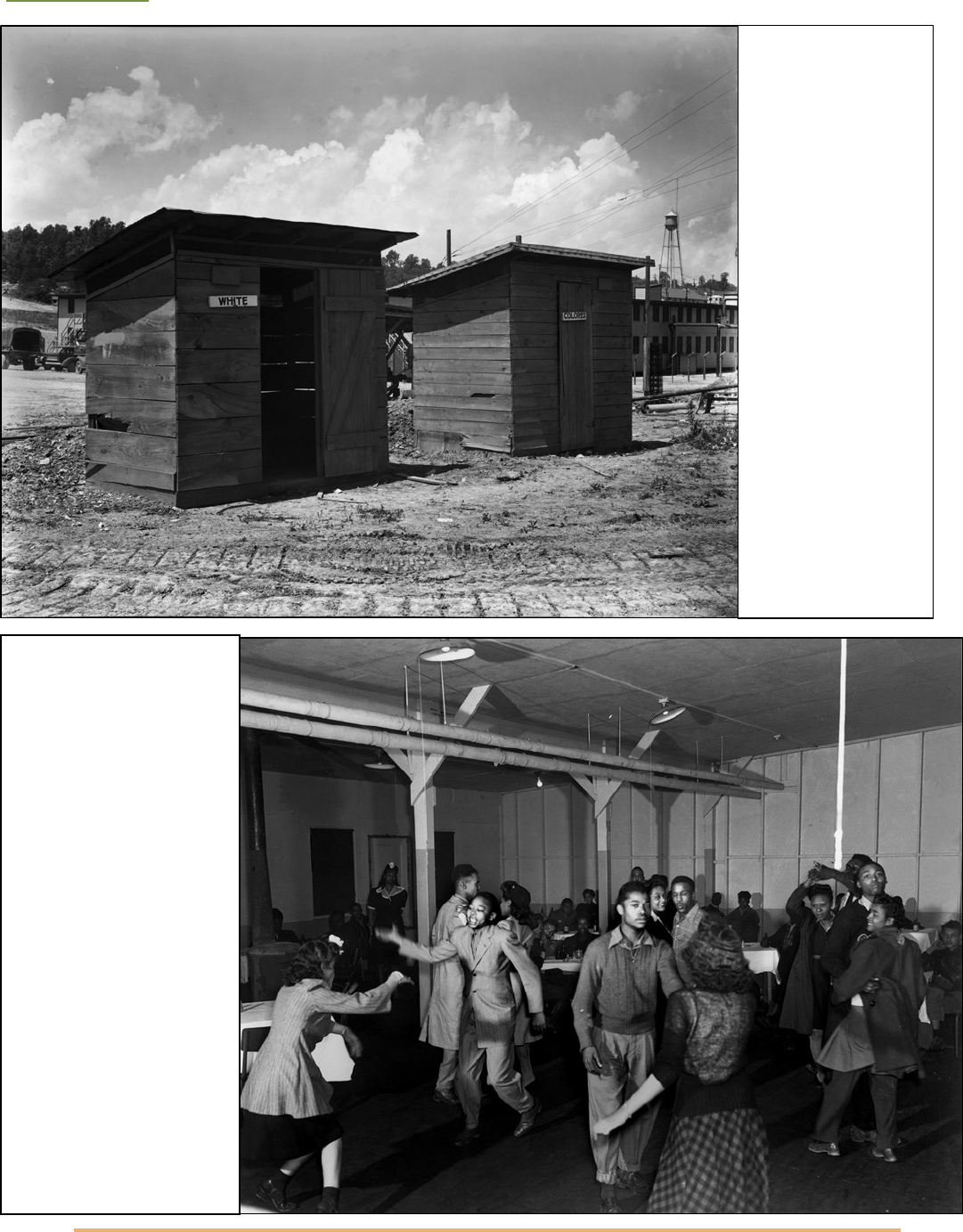

Photo 2: Women outside Hutments in Oak Ridge

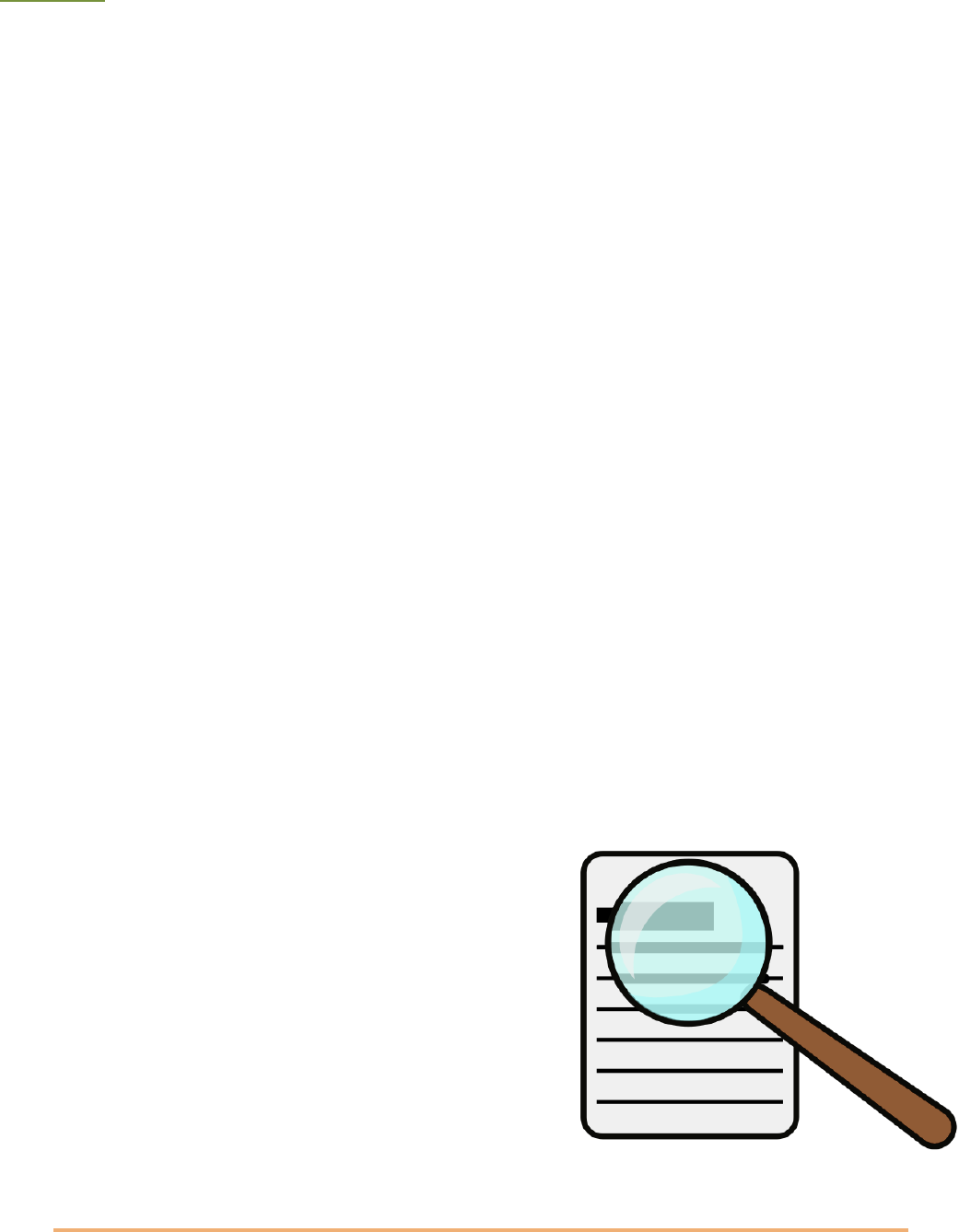

Photo 3: X10-14 DOE photo by Ed Westco Outdoor Privies Oak Ridge Tennessee 1943

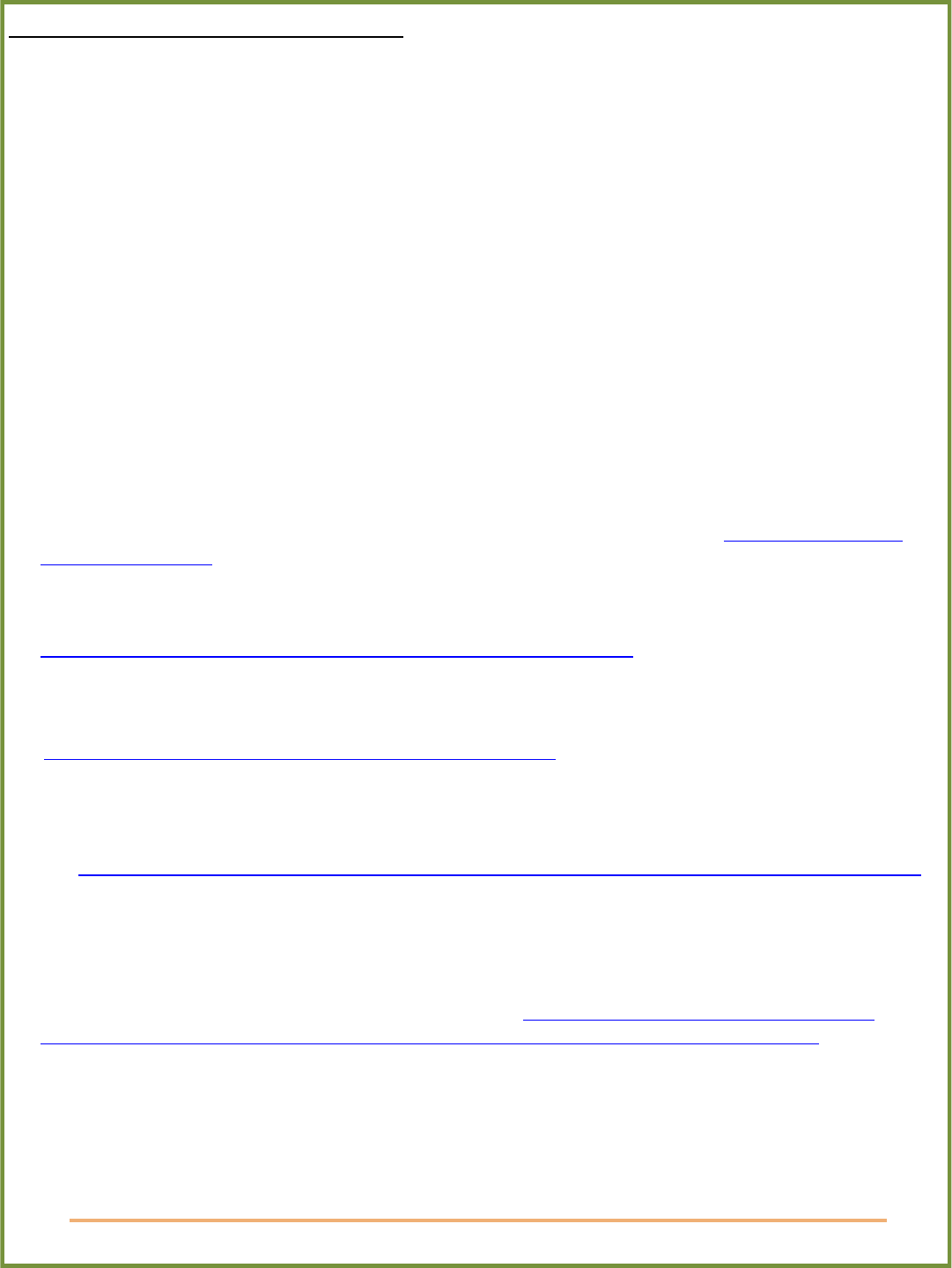

Photo 4: Teen Dance Oak Ridge Tennessee 1945

23

Analyze These: Historic Photos

1

Photo 1:

Who is in the photo?

What jobs do they have?

Write a capon:

2

Photo 2:

Who is in the photo?

What is the seng?

Write a capon:

24

Analyze These: Historic Photos

Photo 3:

What is the seng?

Write your observa-

ons?

What can you infer?

Write a capon:

Photo 4:

What is the seng?

Write your observaons?

What can you infer?

Write a capon:

25

Read This: Excerpt from NPS website

“President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Execuve Order 8802 stated: “I do hereby rearm the policy of the United States

that there shall be no discriminaon in the employment of workers in defense industries of government because of

race, creed, color or naonal origin, and I do hereby declare that it is the duty of employers and of labor organizaons,

to provide for the full and equitable parcipaon of all workers in defense industries, without discriminaon...” Even

though the president had wrien this execuve order, things did not always go as planned.

African-American workers within Oak Ridge lived in a community located near today’s Illinois Avenue. Residents within

that community lived in small wooden shacks called hutments, unlike housing in other communies. At 14 feet by 14

feet, hutments were roughly the size of a storage shed and were shared by 5-6 people.

Amenies were sparse, with a coal-burning stove, dirt oor, one door and no bathroom. Married couples were not

allowed to live together. Instead, women lived in their own guarded, and fenced-o community called the “pen,”

enclosed by a 5-foot fence with barbed wire lining the top. Their children were not permied to live in Oak Ridge unl

1946. Original plans for a “Negro Village” on the east end of town, with housing and a shopping center, were

abandoned as Oak Ridge grew.

For many people the wages and living condions were beer than back home, and transportaon was provided;

nevertheless, discriminatory pracces and Jim Crow laws were an ever-present barrier to prosperity in day-to-day life.

Despite the many challenges that African-Americans faced during this point in me in American history, many went on

to become prominent cizens; doctors, teachers, principals, city counsel members, leaders within their communies,

and some became sciensts within the Manhaan Project.

African-Americans also faced much of the same discriminaon at the Hanford, Washington site. There are no records of

African-American workers in Los Alamos, New Mexico, during the Manhaan Project.”

26

Acvity 6—Sacrice in the Secret City :

Objecves:

Students will understand that the war eort meant shortages of many material and consumable goods. Students will

be able to state ways these shortages aected people’s daily lives and ways they coped. Students will also understand

that workers were not allowed to talk about their jobs and mainly did not know exactly what they were working on

much of the me. Students will understand that maintaining secrecy and security was important to the success of the

Manhaan Project

Direcons:

Read the excerpt about raoning. Then have students analyze the photos.

Suggested Acvity:

Use the crop technique to analyze photos and discuss in groups of 2-4. Then have students create a war poster about

raoning or conservaon in small groups.

Sources:

Sacricing for the Common Good: Raoning in WWII arcle about the WWII Memorial www.nps.gov/arcles/

raoning-in-wwii.htm

Photos are from the Department of Energy in Oak Ridge Flicker webpage. People Oak Ridge 1940’s.

www.ickr.com/photos/doe-oakridge/albums/72157671325827802/page1

Photos are from the Department of Energy in Oak Ridge Flicker webpage. Billboards Oak Ridge 1940’s.

www.ickr.com/photos/doe-oakridge/sets/72157672128427296

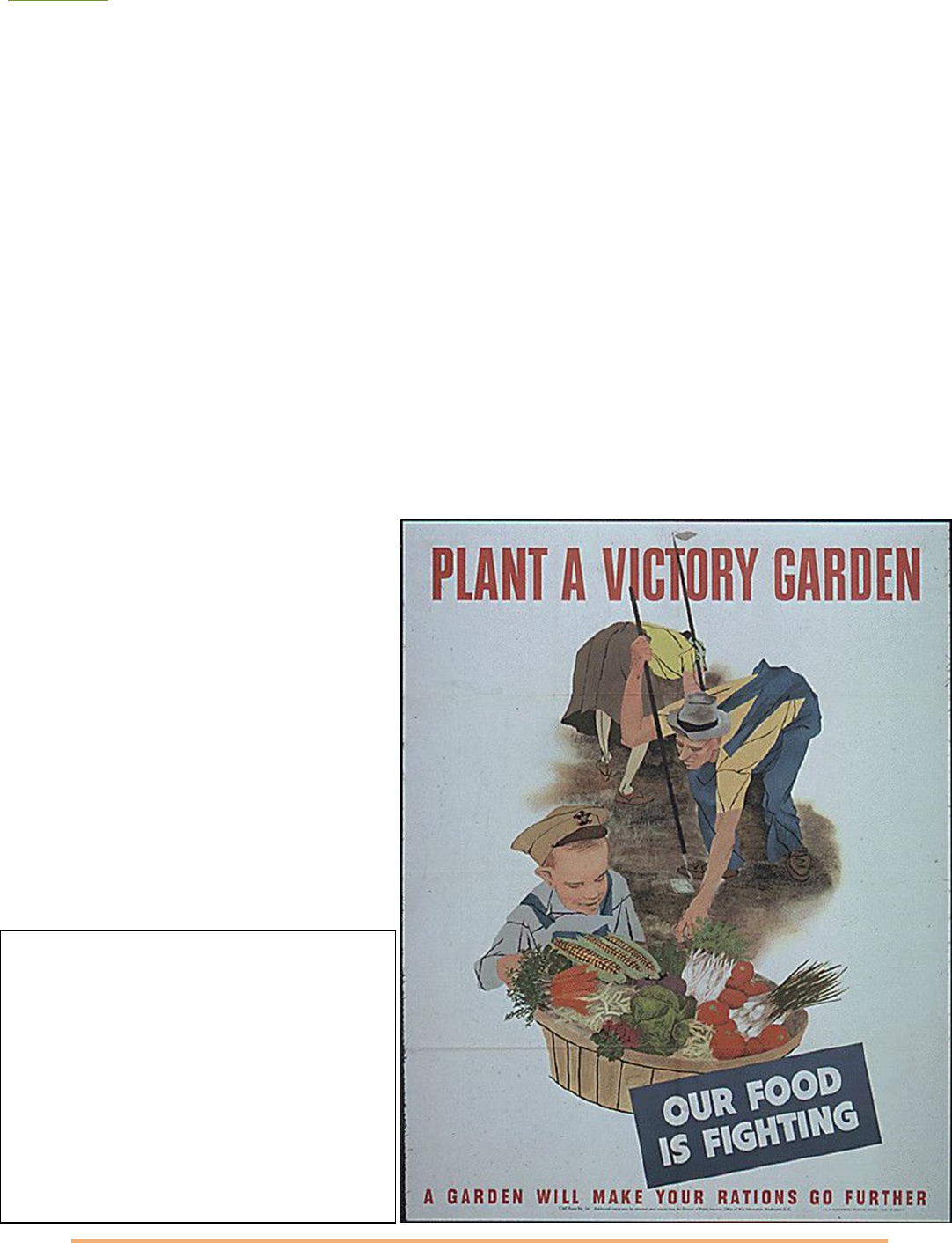

Poster 44-PA-368; Plant A Victory Garden. Our Food Is Fighng.; 1941-1945; World War II Posters, 1942 - 1945;

Records of the Oce of Government Reports, Record Group 44; Naonal Archives at College Park, College Park,

MD. www.docsteach.org/documents/document/plant-a-victory-garden-our-food-is-ghng, September 3, 2017

Other Suggested Sources:

Dickson, Peggy. Memories of Oak Ridge During World War II. www.atomicheritage.org/sites/default/les/

resources/Memories%20of%20Oak%20Ridge%20During%20WWII%20by%20Peggy%20Dickson.pdf

27

Read This: Excerpt from Sacricing for the Common Good, NPS Website

During the Second World War, Americans were asked to make sacrices in many ways. Raoning was not only one of

those ways, but it was a way Americans contributed to the war eort.

When the United States declared war aer the aack on Pearl Harbor, the United States government created a system

of raoning, liming the amount of certain goods that a person could purchase. Supplies such as gasoline, buer, sugar

and canned milk were raoned because they needed to be diverted to the war eort. War also disrupted trade,

liming the availability of some goods. For example, the Japanese Imperial Army controlled the Dutch East Indies

(today’s Indonesia) from March 1942 to September 1945, creang a shortage of rubber that aected American

producon.

On August 28, 1941, President Roosevelt’s Execuve Order 8875 created the Oce of Price Administraon (OPA). The

OPA’s main responsibility was to place a ceiling on prices of most goods, and to limit consumpon by raoning.

Americans received their rst raon cards in May 1942. The rst card, War Raon Card Number One, became known as

the “Sugar Book,” for one of the commodies Americans could purchase with their raon card. Other raon cards

developed as the war progressed. Raon cards included stamps with drawings of airplanes, guns, tanks, aircra, ears of

wheat and fruit, which were used to purchase raoned items.

The OPA raoned automobiles, res, gasoline,

fuel oil, coal, rewood, nylon, silk, and shoes.

Americans used their raon cards and stamps to

take their meager share of household staples

including meat, dairy, coee, dried fruits, jams,

jellies, lard, shortening, and oils.

Americans learned, as they did during the Great

Depression, to do without. Sacricing certain

items during the war became the norm for most

Americans. It was considered a common good for

the war eort, and it aected every American

household.

Analyze the photos and answer the quesons.

What does the ad communicate?

What is the objecve of the ad?

28

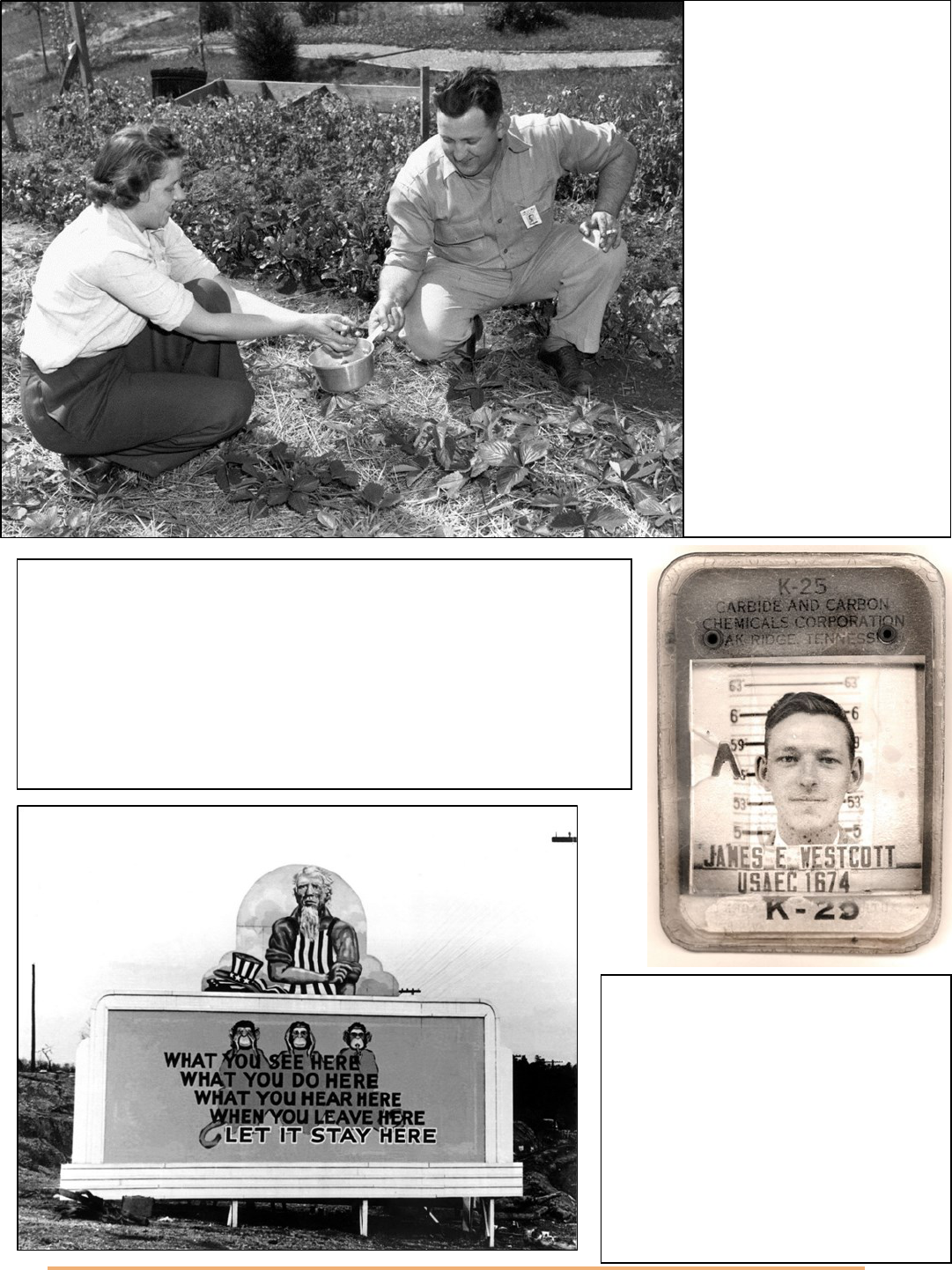

Who is in the photo?

What is the seng?

What is the acvity?

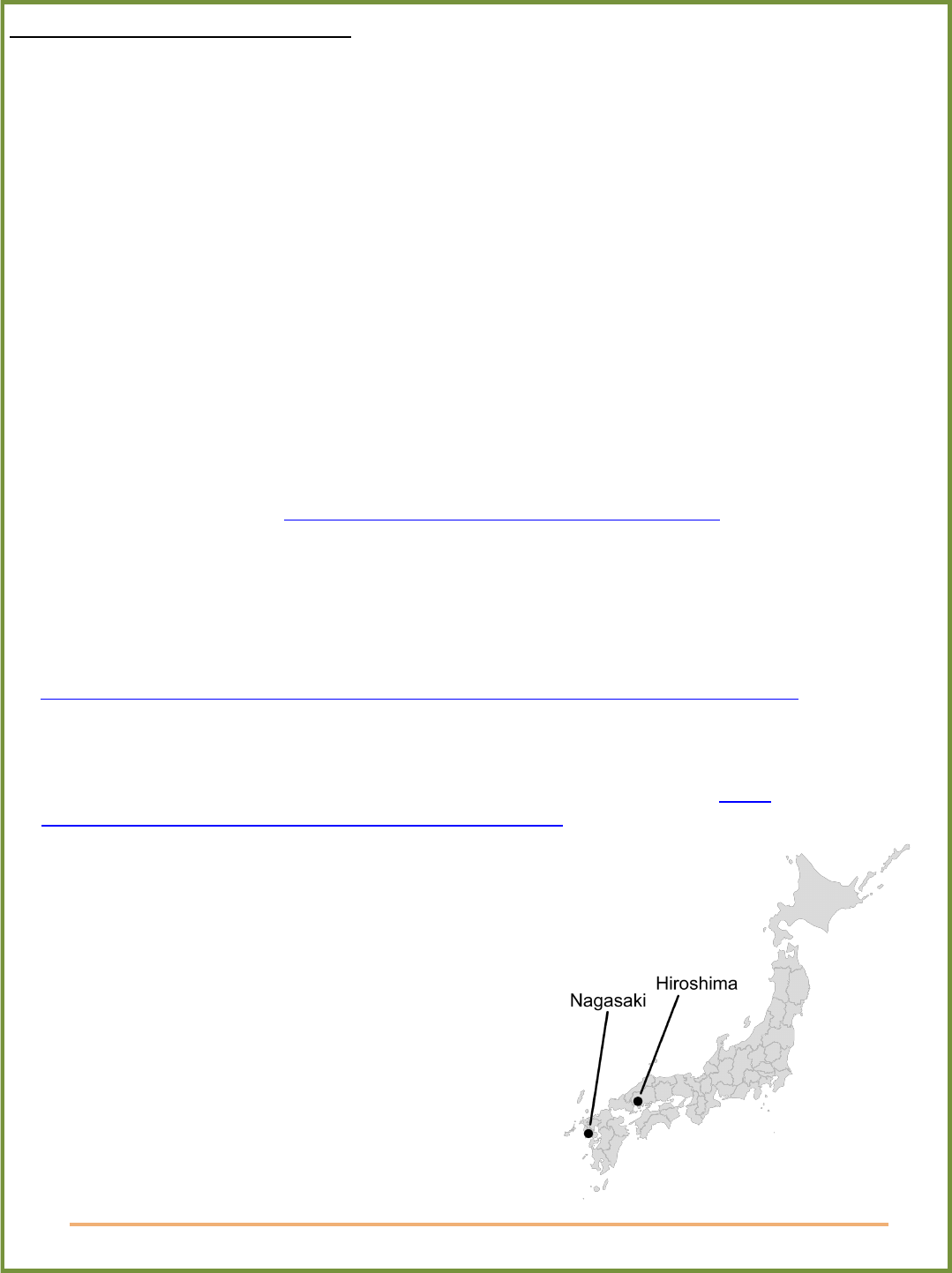

What is in the photo?

What is the object for?

Describe the billboard?

Is the message eecve?

29

Acvity 7—Dropping the Bombs :

Objecves:

Students will be able to think crically about the reasons for using the bomb and reasons against using the bomb.

Students can idenfy ways in which using the bomb impacted the naons involved and world history to follow.

Direcons:

Have students read the excerpt from the Foundaon Document. Give students background assign research into

reason for and against using the bomb.

Suggested Acvity:

Students will write an essay arculang reasons the U.S. decided to use the bomb. Students will examine the human

cost of this decision through independent research. It is suggested to organize a debate between students, for or

against the bomb.

Sources:

Foundaon Document: Manhaan Project Naonal Historic Park, Tennessee, New Mexico, Washington, January

2017. (page 12) Access online: hps://www.nps.gov/mapr/foundaon-document.htm

Other Suggested Sources:

The Manhaan Project, Part 2, Department of Energy podcast, Direct Current.

hps://energy.gov/podcasts/direct-current-energygov-podcast/s2-e3-manhaan-project-part-2

Tennessee Virtual Achieve, Knoxville News Sennel newspaper dated August 6, 1945. hp://

teva.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collecon/p15138coll18/id/439

30

Read This: Excerpt from the Foundaon Document

“The Manhaan Project owed its existence to fear that Nazi Germany was developing an atomic weapon, but the

surrender of Germany in spring 1945 turned the focus of the program to perfecng a device that could be used

against Japan in the ongoing war in the Pacic. American strategists thought that an invasion of the Japanese Home

Islands might be required to end the conict, and planning and preparaon for the invasion, codenamed Operaon

Downfall, began more than a year before the Trinity test. Esmates of casuales resulng from an invasion and

defeat of Japan varied widely, with the upper range numbering in the millions for the United States, its allies, and the

Japanese military and civilians.

President Harry S Truman and his advisors were well aware that successful development and deployment of an

atomic weapon could alter strategic calculaons for ending the war. Plans were made for launching an aack with

these weapons from recently captured Tinian Island (now part of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana

Islands) in the Pacic, within striking distance of Japan by B-29 bombers. Truman formed an Interim Commiee of

top ocials charged with recommending the proper use of atomic weapons. The group considered whether a

demonstraon of the bomb might possibly convince the Japanese to surrender. This was rejected, however, out of

fear that the bomb could malfuncon, the Japanese might put U.S. prisoners of war in the area, or they might

manage to shoot down the plane. In addion, the shock value of the new weapon could be lost. These reasons and

others convinced the group that the bomb should be dropped without warning on a “dual target”—a war plant

surrounded by workers’ homes.

On August 6, 1945, just three weeks aer the Trinity test, the United States dropped the “Lile Boy” uranium bomb

on Hiroshima, Japan. A B-29 bomber named Enola Gay lied o in the predawn hours from Tinian Island and released

the rst atomic weapon in history over Hiroshima. “Lile Boy” detonated with a yield of 13 kilotons at nearly 2,000

feet above the city, to maximize its destrucve eects.

The eects of the explosion were both devastang and indiscriminate, a lethal combinaon of blast overpressure,

extreme heat, and radiaon eects that killed between 90,000 and 166,000 people. Half of the fatalies came from

the inial blast and restorm, and those who did not perish immediately in the blast suered for days or weeks

before nally succumbing to gruesome burn injuries or acute radiaon sickness. More than one-third of Hiroshima’s

people died, and two-thirds of its buildings were completely destroyed.

Three days later, on August 9, 1945, another B-29 bomber named Bock’s Car lied o from Tinian Island carrying the

“Fat Man” plutonium implosion-type bomb. Unable to aack its primary target of Kokura due to poor visibility, the

crew released “Fat Man” over its secondary target, the city of Nagasaki. “Fat Man” detonated 1,700 feet above the

city with a yield of 22 kilotons. The explosion was contained by the steep hills that surrounded ground zero; sll,

between 60,000 and 80,000 people were killed by the combined eects of the bomb. Those who survived the

bombings faced the loss of family members, destroyed livelihoods, and a lifeme of signicantly increased risk of

leukemia and other cancers due to radiaon exposure.

The destrucve eects of the two atomic bombs, combined with the Soviet invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria

on August 9, led Japan to surrender on August 14. The United States and its allies began their occupaon of Japan on

August 28, the rst foreign occupaon in the history of the Japanese naon.”

31

Organizing Bomb Research and Quesons to Consider

1. Why did Truman decide to use the bomb?

2. How did this benet civilians? Armed service personnel?

3. What other opons where available to the U.S.? What was the outlook?

4. What was the esmated death toll in Hiroshima? Nagasaki?

5. How does the death and destrucon compare other bombings in Japan, for instance, the re-bombing of Tokyo?

6. What where the lasng eects of dropping a nuclear weapon on Japan in the cies?

7. What are the environmental impacts of dropping the bomb as well as keeping supplies of nuclear weapons?

8. How did the development of atomic weapons inuence the course of history aer the war?

32

Objecves/Standards: These are just some of the standards that may be used for this lesson. Please

add to, or delete, as you the teacher need for your students with this lesson. These are chosen for use

with high school students with emphasis on standards in English/Language Arts & US History.

ENGLA

11-12.RI.KID.1 Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw inferences; support an interpretaon of a text by cing and

synthesizing relevant textual evidence from mulple sources.

9-10.RI.KID.1 Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw inferences; cite the strongest, most compelling textual evidence to

support conclusions.

11-12.RI.KID.2 Determine mulple central ideas of a text or texts and analyze their development; provide a crical summary. 9-

10.RI.KID.2 Determine a central idea of a text and analyze its development; provide an objecve or crical summary.

11-12.RI.IKI.7 Evaluate the topic or subject in mulple diverse formats and media.

9-10.RI.IKI.7 Evaluate the topic or subject in two diverse formats or media.

11-12.W.TTP.3 Write narrave con or literary noncon to convey experiences and/or events using eecve techniques, well-

chosen details, and well-structured event sequences. a. Engage and orient the reader by seng out a problem, situaon, or

observaon and its signicance, establishing point of view, and introducing a narrator/speaker and/or characters. b. Sequence

events so that they build on one another to create a coherent whole and build toward a parcular tone and outcome. c. Create a

smooth progression of experiences or events. d. Use narrave techniques, such as dialogue, pacing, descripon, reecon, and

mulple plot lines to convey experiences, events, and/or characters. e. Provide a conclusion that follows from and reects on

what is experienced, observed, or resolved over the course of the narrave. f. Use precise words and phrases, telling details, and

sensory language to convey a vivid picture of the experiences, events, seng, and/or characters. g. Use appropriate language and

techniques, such as metaphor, simile, and analogy. h. Establish and maintain an appropriate style and tone.

9-10.W.TTP.3 Write narrave con or literary noncon to convey experiences and/or events using eecve techniques, well-

chosen details, and well-structured event sequences. a. Engage and orient the reader by seng out a problem, situaon, or

observaon, establishing point of view, and introducing a narrator/speaker and/or characters. b. Sequence events so that they

build on one another to create a coherent whole.

US History

US.48 Explain the reasons for American entry into World War II, including the aack on Pearl Harbor. G, H, P

US.49 Idenfy the roles and the signicant acons of the following individuals in World War II: H, P · Winston Churchill · Dwight

Eisenhower · Adolph Hitler · Douglas MacArthur · George C. Marshall · Benito Mussolini · Franklin D. Roosevelt · Joseph Stalin ·

Hideki Tojo · Harry Truman

US.52 Examine and explain the entry of large numbers of women into the workforce and armed forces during World War II and

the subsequent impact on American society. C, E, H

US.53 Examine the impact of World War II on economic and social condions for African Americans, including the Fair

Employment Pracces Commiee and the eventual integraon of the armed forces by President Harry Truman. (T.C.A. § 49-6-

1006) C, E, H, P, TCA

US.55 Describe the war’s impact on the home front, including: raoning, bond drives, propaganda, movement to cies and

industrial centers, the Bracero program, conversion of factories for warme producon, and the locaon of prisoner of war

camps in Tennessee. C, E, G, H, P, T

US.56 Describe the Manhaan Project, and explain the raonale for using the atomic bomb to end the war. H, P, T

US.64 Explain the fears of Americans surrounding nuclear holocaust and debates over stockpiling and the use of nuclear

weapons, including: · Atomic tesng C, H, P · Civil defense · Fallout shelters · Impact of Sputnik · Mutual assured destrucon

33