125

VOLUME 45 : NUMBER 4 : AUGUST 2022

ARTIC LE

This article is peer-reviewed© 2022 NPS MedicineWise

Helen K Reddel

Research leader and

Director, Australian Centre

for Airways Disease

Monitoring

1

Honorary visiting physician

2

Gloria J Foxley

Clinical trials coordinator

1,2

Sharon R Davis

Postdoctoral research

fellow, Australian Centre for

Airways Disease Monitoring

1

1

Woolcock Institute of

Medical Research and The

University of Sydney

2

Royal Prince Alfred

Hospital

Sydney

Keywords

asthma, drug dose

calculation, inhaled

corticosteroids, metered

dose inhalers

Aust Prescr 2022;45:125–9

https://doi.org/10.18773/

austprescr.2022.033

How to step down asthma preventer

treatment in patients with well-controlled

asthma – more is not always better

SUMMARY

Most of the benefit of asthma preventer inhalers is seen with low doses. However, many Australian

patients are prescribed doses of inhaled corticosteroids that are higher than necessary to control

their asthma.

Prescribing unnecessarily high preventer doses increases the patient’s risk of adverse effects.

Theymay also increase the patient’s out-of-pocket costs.

Asthma guidelines recommend considering a step-down in preventer treatment after asthma has

been well controlled for two to three months in adults and for six months in children. The step-

down process should be individualised for each patient.

Preventive therapy should not be stopped completely.

LABA.

4

There are several possible explanations for this

deviation from the recommendations. Some patients

with frequent symptoms at diagnosis may have

been prescribed a high-dose preventer, without the

dose being reviewed after the symptoms improved.

Many patients have their preventer dose increased

during a flare-up, but few return for review after

they have recovered, so they remain indefinitely on

unnecessarily high doses.

5

In some cases, clinicians,

given the substantial pressures on their time, feel that

switching asthma treatment may not be a worthwhile

use of their time, especially if there is a risk that

asthma control will be worse after the switch.

6

Why consider stepping down

asthmatreatment?

Most of the benefits of ICSs are achieved with low

doses which are associated with very little risk of

adverse effects. Long-term treatment with high doses

is associated with a small increase in the background

risk of conditions such as cataract and osteoporosis.

7

Some patients are concerned about any type of

corticosteroid treatment,

8

with some concerns

mistakenly driven by information about anabolic

steroids. Patients may not be aware that the risks

described in Consumer Medicines Information are

seen only with high ICS doses taken for a long period

of time, or with oral corticosteroids. When starting

treatment, prescribers should emphasise to the patient

that one of the goals of asthma management is to first

achieve good control and then find the lowest dose for

them that will keep the asthma well controlled.

Introduction

Asthma management is not a case of ‘one size fits all’.

A key goal is to customise treatment for the needs

of each patient. This involves finding the lowest dose

that will keep asthma symptoms well controlled and

reduce the risk of severe attacks (also called severe

flare-ups or exacerbations), while minimising the risk

of adverse effects.

Inhaled corticosteroids

Australian asthma guidelines recommend that most

adult and adolescent patients should be prescribed

a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) or an

as-needed combination of low-dose ICS and low-dose

formoterol.

1

Only some patients need daily treatment

with a combination of low-dose ICS with a long-acting

beta

2

agonist (LABA). Few patients require medium or

high doses of the ICS–LABA combination, or add-on

treatment (for ICS doses for adults and adolescents,

see Table 1).

2

For children 6–11 years, regular ICS is

recommended for those who have symptoms more

than once weekly, or frequent or moderately severe

exacerbations. Few children require high doses (for

ICS doses for children, see Table 2).

3

Guidelines

recommend the consideration of stepping down

the dose of therapy when asthma has been stable

and well controlled for 2–3 months in adults, and six

months in children.

1

Despite these guidelines, a recent study found

that 71% of Australian adults and adolescents with

asthma who were prescribed preventer inhalers had

been dispensed a high-dose combination of ICS–

126

ARTIC LE

VOLUME 45 : NUMBER 4 : AUGUST 2022

Full text free online at nps.org.au/australian-prescriber

An additional reason for considering stepping down

the dose is that it may substantially reduce out-of-

pocket costs for patients. This may improve their

adherence to therapy.

9,10

Which patients should be

consideredfor a step-down?

Evidence shows that preventer treatment can be

stepped down safely. Systematic reviews of studies in

properly selected patients found no overall increase

in the risk of exacerbations.

11

However, the dose of ICS

that will keep asthma well controlled varies between

patients, so consider each step-down as a treatment

trial and monitor the patient closely afterwards. There

is much less evidence about stepping down treatment

in children.

11

Consider stepping down therapy when asthma

has been well controlled by a stable dose of ICS

or ICS–LABA for at least 2–3 months in adults

and adolescents and after six months in children,

particularly if the ICS dose is medium or high by

age group (see Tables 1 and 2).

2,3

All patients should

have a written asthma action plan before starting a

step-down.

To assess symptom control, use a tool such as the

Asthma Control Test. This evaluates symptoms,

reliever use and perceived control over four weeks.

12

Also ask patients if they have had any flare-ups in

the last 12 months, as these increase the risk of future

exacerbations. A flare-up more than three months ago

that was triggered by an isolated upper respiratory

infection would not necessarily be a contraindication

to stepping down the dose, provided symptoms had

been well controlled since then.

Poor adherence is not necessarily a barrier to stepping

down, provided the patient has well-controlled

asthma and no exacerbations. A greater reduction in

the prescribed dose may be considered if the patient

has been using their preventer infrequently. However,

if a patient notices more symptoms after missing

only one or two doses of their current preventer, they

are likely to need their current dose, so it should not

bereduced.

During pregnancy, consider stepping down only if

the woman has well-controlled asthma and is taking

a high-dose preventer. Otherwise, postpone stepping

down until after delivery.

13

Stepping down in patients with

severeasthma

For patients with severe asthma, careful step-down

ofinhaled therapy can be considered if symptom

control and exacerbations respond to add-on

biologic therapy such as benralizumab, dupilumab,

mepolizumab or omalizumab. The highest priority

is to gradually reduce and stop oral corticosteroids.

Reducing the ICS dose can be considered after

3–6months, but not to below a medium dose.

14

In

severe asthma, any dose reduction should be in

consultation with a specialist.

A step-by-step guide to

steppingdown

Depending on the patient’s current therapy, there are

several step-down options (see Table 3). The step-

down process is individualised for each patient.

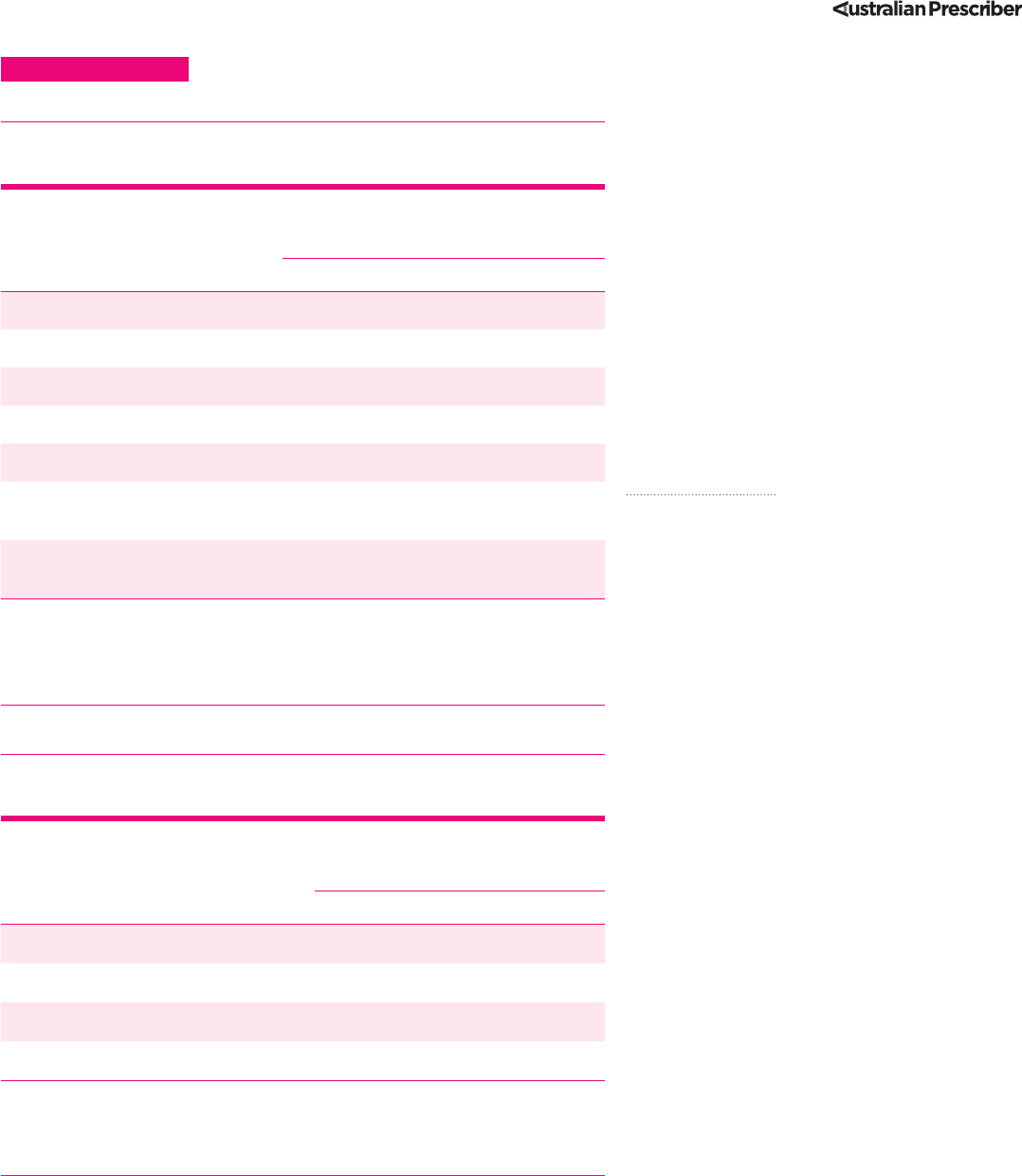

Table 1 Inhaled corticosteroid dose levels for adults

andadolescents

2

Inhaled corticosteroid Total daily metered dose (micrograms)

foradults and adolescents 12 years and

over with asthma

Low Medium High

Beclometasone dipropionate 100–200 250–400 >400

Budesonide 200–400 500–800 >800

Ciclesonide 80–160 240–320 >320

Fluticasone furoate – 100 200

Fluticasone propionate 100–200 250–500 >500

Mometasone furoate* in combination

with indacaterol

62.5 127.5 260

Mometasone furoate*† in combination

with indacaterol and glycopyrronium

– 68 136

This is not a table of equivalence, but instead it shows the doses of inhaled

corticosteroid that are classified as low, medium or high for each drug.

* Delivered doses not metered doses

† Approved only for adults 18 years and over

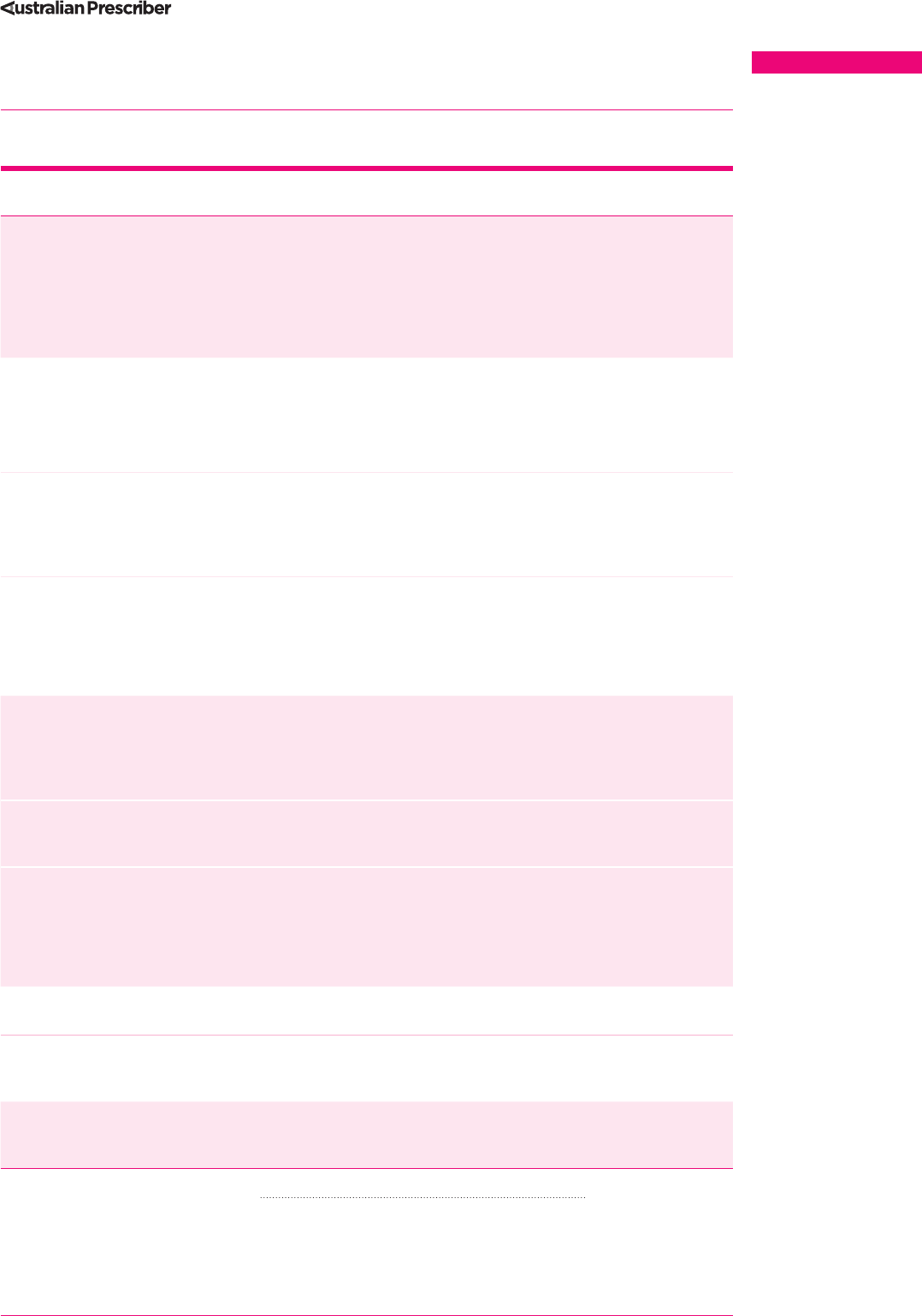

Table 2 Inhaled corticosteroid dose levels for children

6–11years

3

Inhaled corticosteroid Total daily metered dose

(micrograms) for children 6–11 years

with asthma

Low High

Beclometasone dipropionate 100–200 >200 (maximum 400)

Budesonide 200–400 >400 (maximum 800)

Ciclesonide 80–160 >160 (maximum 320)

Fluticasone propionate 100–200 >200 (maximum 500)

This is not a table of equivalence, but instead it shows the doses of inhaled

corticosteroids that are classified as low or high for each drug. The only dose of

fluticasone furoate indicated for children (50 micrograms/day) is not available

inAustralia.

How to step down asthma preventer treatment in patients with well-controlled asthma – more is not always better

127

ARTIC LE

VOLUME 45 : NUMBER 4 : AUGUST 2022

Full text free online at nps.org.au/australian-prescriber

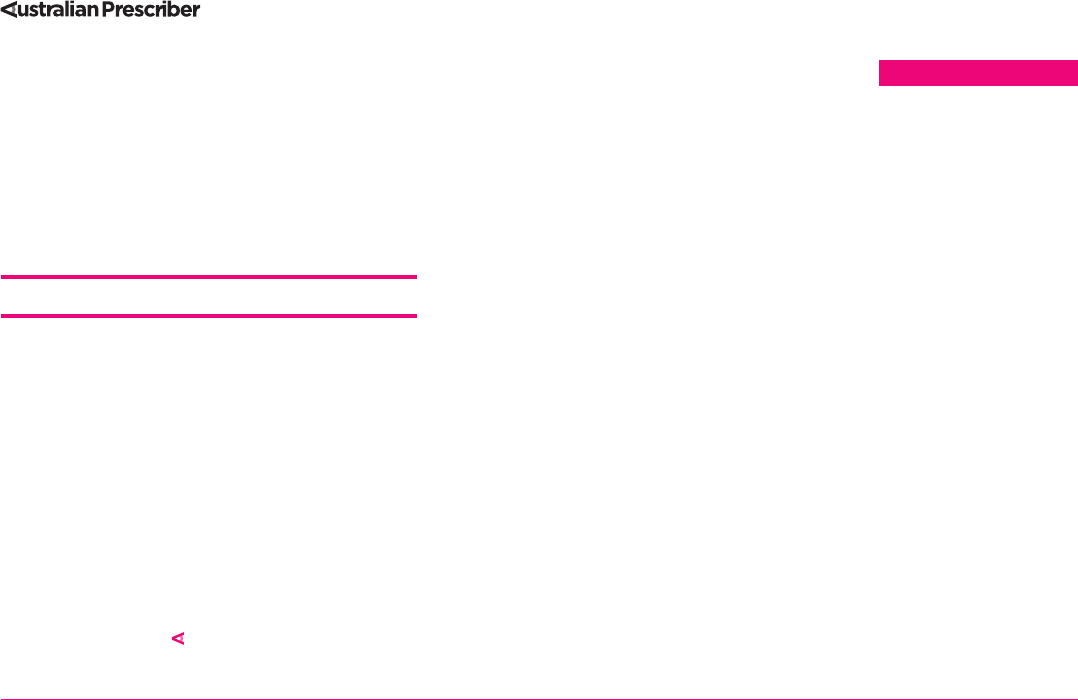

Table 3 Step-down options for preventer therapy in adults and adolescents who

have had well-controlled asthma for at least 2–3 months

1

Treatment

level

Current preventer treatment Suggested step-down options

5 High-dose combination ICS–LABA plus

add-on therapy such as biologic therapy or

oral corticosteroids for severe asthma

Discuss with the specialist who prescribed the add-on

treatment. Once asthma is well controlled, the highest

priority for stepping down is to gradually reduce and

then cease oral corticosteroids (if prescribed); check for

adrenal suppression. Advise patients not to stop their

combination ICS–LABA treatment. Do not reduce ICS–

LABA below a medium dose.

4 Medium- or high-dose ICS–LABA–LAMA

maintenance, plus as-needed SABA

Consider ceasing the LAMA, and continuing the same

dose of ICS–LABA.

OR

If the ICS dose is high, consider reducing to a medium

dose (but not to low dose) while continuing LAMA.

4 Medium-dose MART, i.e. 2 inhalations

twice daily of budesonide/formoterol

200/6micrograms or beclometasone/

formoterol 100/6 micrograms, plus 1

inhalation taken as needed for symptom relief

Low-dose MART, i.e. 1 inhalation twice daily of

budesonide/formoterol 200/6 micrograms or

beclometasone/formoterol 100/6 micrograms, plus 1

inhalation taken as needed for symptom relief.

4 Medium- or high-dose ICS–LABA

maintenance, plus as-needed SABA

Continue ICS–LABA, reducing the ICS dose by 25–50% by:

• prescribing a lower dose ICS-LABA formulation

OR

• for ICS–LABA combinations prescribed more than once

daily, by reducing the number of inhalations per day.

3 Low-dose MART, 1 inhalation twice daily of

budesonide/formoterol 200/6micrograms

or beclomethasone/formoterol

100/6micrograms, plus 1 inhalation taken

as needed for symptom relief

As-needed only low-dose budesonide/formoterol

200/6micrograms.

[Note: as-needed only treatment has not been studied

with beclometasone/formoterol]

3 Low-dose fluticasone furoate vilanterol

(a once-daily ICS–LABA) plus as-needed

SABA

Consider stepping down to once-daily fluticasone

furoate (ICS alone) plus as-needed SABA.

3 Low-dose combination ICS–LABA

maintenance (twice-daily formulations),

plus as-needed SABA

Reduce ICS–LABA dose by 25–50% by:

• reducing from twice-daily to once-daily

OR

• for patients prescribed 2 pus per dose, reducing to

1pu per dose.

2 Maintenance low-dose ICS plus as-needed

SABA

Continue daily low-dose ICS (with a lower dose if

available), plus as-needed SABA.

2 As-needed low-dose budesonide/

formoterol 200/6 micrograms taken as

needed for symptom relief

Reduce to as-needed low-dose budesonide/formoterol

100/6 micrograms per dose.

1 As-needed SABA alone (not a preventer) SABA-only treatment is not recommended, except for

the very few patients who have symptoms less than

twice a month and no risk factors for exacerbations.

Treatment levels in the table correspond to Australian asthma guidelines for adults andadolescents.

1

ICS inhaled corticosteroid

LABA long-acting beta

2

agonist

LAMA long-acting muscarinic antagonist, as separate inhaler or in triple ICS–LABA–LAMA combination

MART maintenance and reliever therapy with budesonide/formoterol or beclometasone/formoterol. In this regimen, the

patient takes ICS/formoterol combination as both their maintenance treatment and as their reliever (instead of a SABA)

SABA short-acting beta

2

agonist

128

ARTIC LE

VOLUME 45 : NUMBER 4 : AUGUST 2022

Full text free online at nps.org.au/australian-prescriber

How to step down asthma preventer treatment in patients with well-controlled asthma – more is not always better

Use shared decision making

Explain the rationale and the process for stepping

down the dose, and understand the patient’s or

parent’s willingness or concerns. Discuss how the

dose required for the prevention of flare-ups will be

individualised for them.

Timing

Choose an appropriate time to reduce the dose. For

example, do not step down if the patient is developing

a cold, or about to travel, or just before a holiday

period. For patients who are allergic to rye grass

and live in an area where thunderstorm asthma may

occur, it would not be advisable to step down their

treatment during the pollen season. Step down before

the previous inhaler is completely empty, so the

patient can resume their previous dose promptly if

asthma worsens.

Assess the patient’s risk factors

Risk factors include a history of previous

exacerbations and allergen exposure in sensitised

patients.

Record the patient’s baseline asthma status

Use the Asthma Control Test or document how many

days each week the patient has asthma symptoms,

or needs to use their inhaler to relieve symptoms.

Document lung function if available.

Make small dose adjustments gradually

The ICS dose can be reduced by 25–50%, by

prescribing a lower dose formulation or reducing

thefrequency of use. Consider reducing in two

steps of 25% rather than a single 50% reduction. For

example, if the patient is taking two puffs twice a

day, suggest they drop one of the evening puffs. If

they remain stable after one month, drop the other

evening dose so they would then be taking two puffs

once a day.

Self-monitoring

Ask the patient to monitor symptoms and reliever

use,and record the date of the step-down in their

diary or calendar. Advise them that if, over a few

weeks, they experience an overall increase in

symptoms or reliever use, or start waking at night

due to asthma, they should resume their previous

dose. For patients who are anxious, or about whom

one is concerned, consider asking for two weeks of

peak expiratory flow monitoring as a baseline, then

mark the step-down date and continue recording

for another 3–4 weeks. The Woolcock peak flow

chart makes it easy to detect exacerbations and

gradual changes.

15

Monitoring peak expiratory

flow isparticularly useful given reduced access to

spirometry during the COVID-19 pandemic. The

National Asthma Council has information to assist

with self-monitoring.

Action plan

Make sure the patient’s written asthma action plan is

up to date, so that they know what to do and who to

contact if they have a flare-up.

Review

Book a follow-up visit for two or three months

afterstepping down (or earlier if there is concern)

and prompt the patient to contact their GP sooner

iftheir asthma worsens. At the follow-up visit, assess

symptom control, adherence, reliever use and lung

function (if test available). If the patient’s asthma is still

stable, consider stepping down by another 25–50%.

Do not completely stop inhaled

corticosteroids

In adults or adolescents, completely stopping

preventive therapy increases the risk of severe

exacerbations.

New step-down options in

mildasthma

For adults and adolescents with well-controlled

asthma on a low-dose ICS or low-dose ICS–LABA,

with an as-needed short-acting beta

2

agonist (SABA)

reliever, one option is to continue daily treatment

indefinitely.

16

However, patients with few symptoms

are often poorly adherent to therapy, increasing their

risk of severe exacerbations.

A new step-down option available in Australia since

2020 is to switch to an as-needed combination of

low-dose budesonide with formoterol. The patient

uses the low-dose budesonide/formoterol inhaler

whenever needed for symptom relief, instead of

a SABA. This option is supported by three large

studies including step-down in mild asthma, that

showed symptom control and lung function were

similar, and the risk of severe exacerbations was the

same or lower, compared with continuing regular

daily ICS with as-needed SABA.

17-20

Importantly, the

risk of severe exacerbations was reduced by more

than 60% compared with switching to SABA-only

treatment.

17

Patients took an average of three to four

doses of budesonide/formoterol 200/6 micrograms

per week, so in clinical practice, one inhaler would

last an average of six months. Although the initial

out-of-pocket cost to the patient would be higher, the

average daily cost to the patient over the life of the

inhaler would be much lower than with daily ICS or

daily ICS–LABA, plus an as-needed SABA.

Smaller studies in adults and children have found

that it is possible to step down from daily ICS to

129

ARTIC LE

VOLUME 45 : NUMBER 4 : AUGUST 2022

Full text free online at nps.org.au/australian-prescriber

taking low-dose ICS only when the patient takes their

SABA for symptom relief. This is more effective than

SABA alone at preventing exacerbations.

21,22

This

approach is not currently recommended in Australian

asthmaguidelines.

Conclusion

A key goal of asthma management is to customise

the treatment to the patient’s needs, by first

achievinggood asthma control and then finding

the minimum effective dose that, together with an

asthmaaction plan, will minimise the patient’s risk

of severe exacerbations. This approach optimises

the benefit for patients, reduces the risk of adverse

effects, and reduces costs for the patient and

the healthcare system. With shared decision-

making anda careful plan, many patients are

keen to engage in the process of optimising their

asthmamanagement.

Conflicts of interest:

In the last three years, Helen Reddel’s institute has

received independent research funding from AstraZeneca,

GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis.She or her institute has

received honoraria for participation in advisory boards

for AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and

Sanofi-Genzyme; honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer

Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Genzyme and

Teva for independent medical educational presentations;

consulting fees from AstraZeneca and Novartis. Helen

Reddel is Chair of the Global Initiative for Asthma(GINA)

Science Committee, and a member ofthe Australian

Asthma Handbook Guidelines Committee.

In the last three years, Gloria Foxley’s institute

has received independent research funding from

AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis.

In the last three years, Sharon R Davis’s institute

has received independent research funding from

AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis.

1. National Asthma Council Australia. Figure – Selecting and adjusting

medication for adults and adolescents. In: Australian asthma handbook.

Version 2.2. Melbourne: National Asthma Council Australia; 2022.

https://www.asthmahandbook.org.au/management/adults [cited 2022 Jul 1]

2. National Asthma Council Australia. Table - Definitions of ICS dose levels in

adults. In: Australian asthma handbook. Version 2.2. Melbourne: National

Asthma Council Australia; 2022. https://www.asthmahandbook.org.au/

management/adults/initial-treatment/preventers/ics-based-preventers

[cited

2022 Jul 1

]

3. National Asthma Council Australia. Table - Definitions of ICS dose levels in

children. In: Australian asthma handbook. Version 2.2. Melbourne: National

Asthma Council Australia; 2022. https://www.asthmahandbook.org.au/

management/children/6-years-and-over/reliever-and-preventer [cited 2022

Jul 1]

4. Hew M, McDonald VM, Bardin PG, Chung LP, Farah CS, Barnard A, et al.

Cumulative dispensing of high oral corticosteroid doses for treating asthma in

Australia. Med J Aust 2020;213:316-20. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50758

5. Yawn BP, Wollan PC, Bertram SL, Lowe D, Butterfield JH, Bonde D, et al.

Asthma treatment in a population-based cohort: putting step-up and step-

down treatment changes in context. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:414-21.

https://doi.org/10.4065/82.4.414

6. Tudball J, Reddel HK, Laba TL, Jan S, Flynn A, Goldman M, et al. General

practitioners’ views on the influence of cost on the prescribing of asthma

preventer medicines: a qualitative study. Aust Health Rev 2019;43:246-53.

https://doi.org/10.1071/AH17030

7. Leone FT, Fish JE, Szefler SJ, West SL; Expert Panel on Corticosteroid Use.

Systematic review of the evidence regarding potential complications of

inhaled corticosteroid use in asthma: collaboration of American College of

Chest Physicians, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology,

and American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Chest

2003;124:2329-40. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.124.6.2329

8. Horne R, Chapman SC, Parham R, Freemantle N, Forbes A, Cooper V.

Understanding patients’ adherence-related beliefs about medicines

prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the Necessity-

Concerns Framework. PLoS One 2013;8:e80633. https://doi.org/10.1371/

journal.pone.0080633

9. Davis SR, Tudball J, Flynn A, Lembke K, Zwar N, Reddel HK. “You’ve got

to breathe, you know” - asthma patients and carers’ perceptions around

purchase and use of asthma preventer medicines. Aust N Z J Public Health

2019;43:207-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12865

10. Laba TL, Jan S, Zwar NA, Roughead E, Marks GB, Flynn AW, et al. Cost-related

underuse of medicines for asthma-opportunities for improving adherence.

JAllergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:2298-2306.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.jaip.2019.03.024

11. Gionfriddo MR, Hagan JB, Rank MA. Why and how to step down chronic

asthma drugs. BMJ 2017;359:j4438. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4438

12. Ko FW, Hui DS, Leung TF, Chu HY, Wong GW, Tung AH, et al. Evaluation of the

asthma control test: a reliable determinant of disease stability and a predictor

of future exacerbations. Respirology 2012;17:370-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/

j.1440-1843.2011.02105.x

13. National Asthma Council Australia. Managing asthma actively during

pregnancy. In: Australian asthma handbook. Version 2.2. Melbourne: National

Asthma Council Australia; 2022. https://www.asthmahandbook.org.au/

populations/pregnant-women/pregnancy/asthma-care [cited 2022 Jul 1]

14. Global Initiative for Asthma. Difficult-to-treat and severe asthma in adults

and adolescents. In: Global strategy for asthma management and prevention.

Fontana, WI, USA: GINA; 2022. https://ginasthma.org/reports [cited 2022

Jul1]

15. Jansen J, McCaffery KJ, Hayen A, Ma D, Reddel HK. Impact of graphic format

on perception of change in biological data: implications for health monitoring

in conditions such as asthma. Prim Care Respir J 2012;21:94-100.

https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00004

16. Reddel HK. Updated Australian guidelines for mild asthma: what’s

changed and why? Aust Prescr 2020;43:220-4. https://doi.org/10.18773/

austprescr.2020.076

17. Bateman ED, O’Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, Barnes PJ, Zheng J, Lamarca R,

etal. Positioning as-needed budesonide-formoterol for mild asthma: effect of

prestudy treatment in pooled analysis of SYGMA 1 and 2. Ann Am Thorac Soc

2021;18:2007-17. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202011-1386OC

18. Bateman ED, Reddel HK, O’Byrne PM, Barnes PJ, Zhong N, Keen C, etal.

As-needed budesonide-formoterol versus maintenance budesonide in

mild asthma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1877-87. https://doi.org/10.1056/

NEJMoa1715275

19. Hardy J, Baggott C, Fingleton J, Reddel HK, Hancox RJ, Harwood M, et al.;

PRACTICAL study team. Budesonide-formoterol reliever therapy versus

maintenance budesonide plus terbutaline reliever therapy in adults with

mild to moderate asthma (PRACTICAL): a 52-week, open-label, multicentre,

superiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019;394:919-28.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31948-8

20. O’Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, Barnes PJ, Zhong N, Keen C,

etal. Inhaled combined budesonide-formoterol as needed in mild asthma.

NEnglJMed 2018;378:1865-76. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1715274

21. Martinez FD, Chinchilli VM, Morgan WJ, Boehmer SJ, Lemanske RF Jr,

MaugerDT, et al. Use of beclomethasone dipropionate as rescue treatment for

children with mild persistent asthma (TREXA): a randomised, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:650-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/

S0140-6736(10)62145-9

22. Papi A, Canonica GW, Maestrelli P, Paggiaro P, Olivieri D, Pozzi E, et al.; BEST

Study Group. Rescue use of beclomethasone and albuterol in a single inhaler

for mild asthma. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2040-52. https://doi.org/10.1056/

NEJMoa063861

REFERENCES