Professional Practice Board

Conducting research with people not having

the capacity to consent to their participation

A practical guide for researchers

Prepared by Catherine Dobson on behalf of the

Mental Capacity Act Working Party

December 2008

ISBN 978 1 85433 485 5

Printed and published by the British Psychological Society.

© The British Psychological Society 2008.

The British Psychological Society

St Andrews House, 48 Princess Road East, Leicester LE1 7DR, UK

Telephone 0116 254 9568 Facsimile 0116 247 0787

E-mail [email protected] Website www.bps.org.uk

Incorporated by Royal Charter Registered Charity No 229642

If you have problems reading this document and would like it in a

different format, please contact us with your specific requirements.

Tel: 0116 252 9523; E-mail: [email protected].

About the Author

Catherine Dobson is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist working with people with learning

disabilities in Lancashire, England. She has conducted research about services for people

with learning disabilities and mental health problems and is a member of Lancashire Care

Foundation Trust’s Research Governance Committee. Catherine has contributed to

regional implementation of the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) and has both organised and

presented papers on aspects of MCA at conferences.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Beverley Lowe and members of the Lancashire Care Trust’s

Research Governance Committee, in particular the Service User and Carer Subcommittee,

for sowing the seed of an idea about guidance for researchers. Secondly, thanks must be

extended to Catherine Dooley, Glynis Murphy, Nigel Atter and other members of the

Mental Capacity Act Working Party of the British Psychological Society for their

encouragement and oversight of methodology and structure of the practice guide.

A practical guide for researchers 1

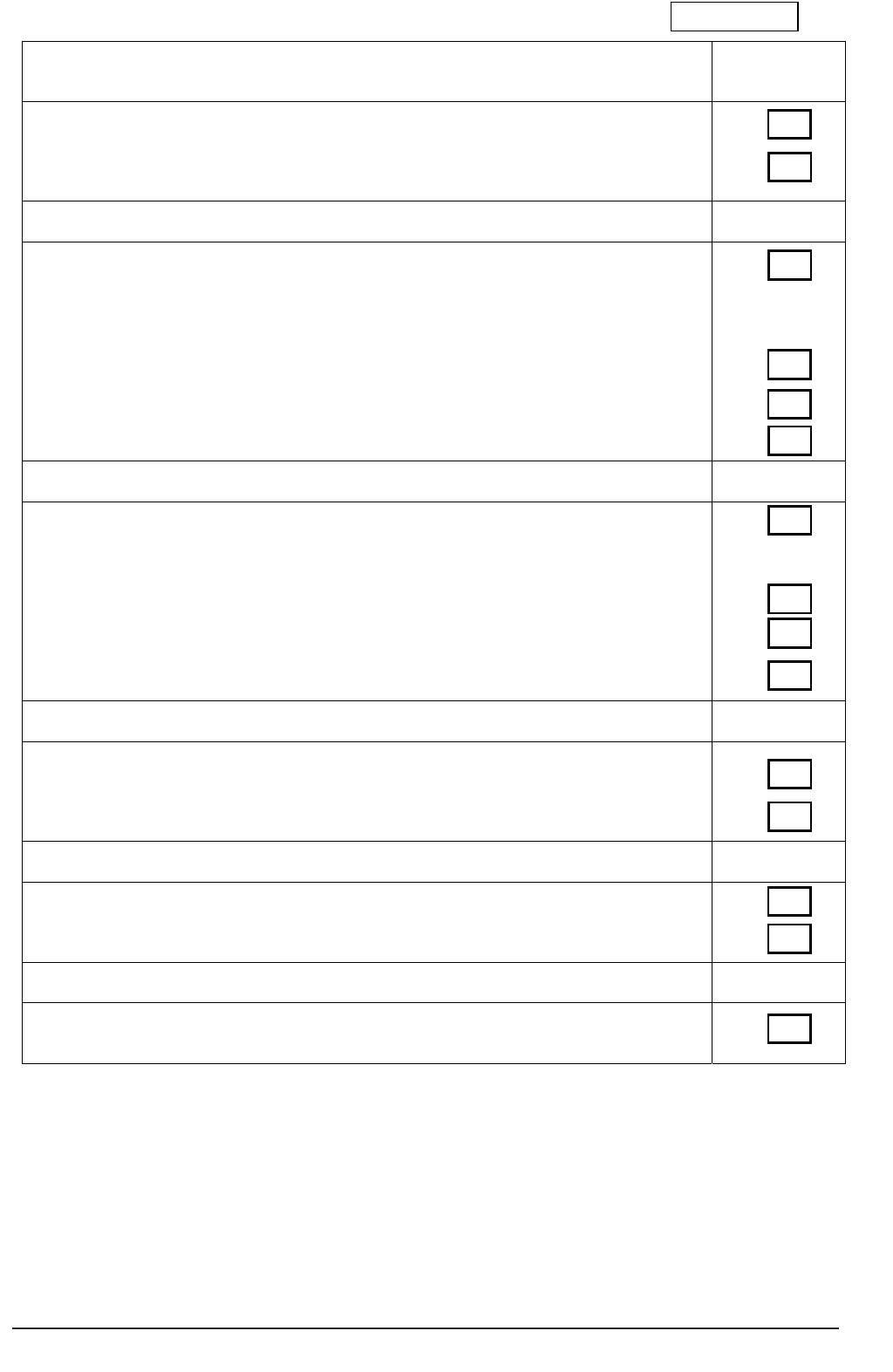

Contents

Page

Foreword: Julie Jones, CEO, Social Care Institute for Excellence 3

Introduction 4

Section 1: Legal requirements for conducting research with people not having capacity to consent

1.1 The research process 6

Section 2: Ethical scrutiny

2.1 Principles of ethical scrutiny 8

2.2 Procedure for ethical review 9

2.3 Intrusive research 9

2.4. Research that does not require consent 10

2.5 Seeking consent to participation in research 10

Section 3: Assessing capacity to consent

3.1 Recruitment of participants 13

3.2 Assessing capacity to consent to participation in research 13

3.3 Applying the Five Statutory Principles of the MCA to judge whether 14

a (prospective) participant has the capacity to consent

3.4 Principle 1 16

3.5 Principle 2 16

3.6 Principle 3 17

3.7 Reaching a judgment about whether a participant lacks the capacity

to consent to research 17

3.8 Loss of capacity during a project 18

Section 4: Consulting with others

4.1 Consulting with others as a way of safeguarding the inclusion of people

who lack the capacity to consent to their participation 20

4.2 Role of Research Consultee 21

4.3 Consulting with a Research Consultee 23

4.4 Personal Consultee 24

4.5 Nominated Consultee 24

Section 5: Appraising participant involvement

5.1 Appraising whether to include or exclude a participant 25

5.2 Reviewing continuing participation in a project 25

5.3 Recommendations for good practice 27

Section 6: Case studies 28

Section 7: Concluding comments 32

Appendices

1 References 34

2 NHS Research Ethics Committees which have been ‘flagged’ to scrutinise

projects involving participants who do not have the capacity to consent 36

3 Roles and responsibilities in the research process 38

4 Additional questions and ethical implications 40

5 Contributors 41

Part 2

Checklists, sample letters and proformae 44

2 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

A practical guide for researchers 3

Foreword

I am very pleased to welcome and commend the research guidance as part of the

supporting materials for implementation of the Mental Capacity Act (2005).

One concern following on from the Act and its Code of Practice was that researchers might

be deterred from conducting research using people who lack capacity as participants,

because of the additional requirements. This could deny people who might wish to take

part in research projects from being included, going against the spirit of the Act and also

potentially limiting fields of enquiry and development. This guidance helps to address

these concerns by supplying practical advice and operational procedures.

This material is impressive in that it summarises the implications of the MCA for

researchers, highlights procedural changes that need to be introduced, and flags up the

ethical issues and responsibilities for researchers being mindful of the underlying

principles of the Act. It also identifies areas where further development work is required.

Of particular value are the various forms that the author has developed; these will be an

invaluable resource for researchers in helping them to construct a framework for their

approach to research and can be tailored to local circumstances.

Julie Jones

Chief Executive Officer, Social Care Institute for Excellence

4 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

Introduction

The practical guide is one of a series of documents commissioned by the Social Care

Institute for Excellence, addressing different aspects of the implementation of the Mental

Capacity Act (2005) and has been prepared for researchers conducting research with

human participants in the United Kingdom. The majority of researchers will be members

of professional bodies and/or be employed by academic or research organisations. Some

researchers may be independent practitioners commissioned to undertake research. The

guidance will also be of relevance to members of research ethics committees and service

user and carer organisations.

Participants of research projects may be members of the general public or be in receipt of

health or social care services.

Professional organisations contributing to the development of the guidance included:

■ The British Psychological Society;

■ The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists; and

■ The Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Rationale for the preparation of the practical guide

The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005 in England and Wales and the Incapacity Act (ICA)

2000 in Scotland have established legal frameworks within Great Britain for people lacking

the capacity to make decisions for themselves.

Sections 30–34 of MCA 2005 and Section 51 of ICA 2000 (Scotland) refer to decisions

concerning participation in research. In general, for all research, researchers should

assume that a participant or potential participant does have the capacity to decide whether

to consent or not to their participation, unless there is evidence that questions the person’s

capacity to reach this decision. The Acts and relevant Codes of Practice outline safeguards

for individual participants, carers and researchers when research projects do involve non-

consenting participants. The Code of Practice for the Mental Capacity Act was published

by the Department for Constitutional Affairs in 2007. Throughout this guide the Code of

Practice will be referred to as the MCA Code of Practice.

This practical guide offers advice and examples of good practice in connection with

conducting research with people lacking the capacity to consent to their participation.

Reference is made throughout the document to guidance produced by different

professional and research organisations within the United Kingdom.

The guidance refers primarily to changes in the research process arising from the MCA

(2005), which applies to England and Wales, with some reference to the Adults with

Incapacity Act (Scotland). At present the Mental Capacity Act does not apply to research

conducted in Northern Ireland, where the legal framework concerning decision-making

for or on behalf of people lacking capacity remains within common law and case law.

The practical guide will be disseminated to professional groups, service user and carer

groups, research organisations, university and NHS research ethics committees via

The practical guide

■ provides a number of flowcharts to assist researchers in deciding between different

courses of action when undertaking research with participants who may lack capacity

to consent;

■ offers suggestions for enhancing the decision-making capability of potential research

participants;

■ assists researchers in establishing whether a participant can or cannot consent to their

participation in research;

■ offers suggestions of who researchers can consult, how and under what circumstances,

when undertaking research with people not having the capacity to consent; and

■ provides sample letters, information sheets and declaration forms.

A practical guide for researchers 5

publications and conference presentations. The document is also available for download

from www.scie.org.uk.

This practical guide is in two parts:

Part 1 is the professional guidance and covers

■ modifications to the research process in order that a project can comply with

MCA;

■ procedures for ethical scrutiny;

■ application of the principles of the Mental Capacity Act to assess whether a

participant can consent to their participation; and

■ safeguards afforded by the Mental Capacity Act, in particular the process of

consultation with others and the appraisal of an individual’s involvement with

a project.

Part 2 provides proformas, sample correspondence and information sheets which could be adapted

by researchers as required for specific projects.

General ideas,

conduct literature review

Complete application

for ethical review

Gain favourable

ethical opinion

Recruit participants

Conduct project

Analyse data Disseminate findings

Prepare protocol

Seek consent

6 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

Section1: Legal requirements for conducting research with

people not having the capacity to consent

1.1 The research process

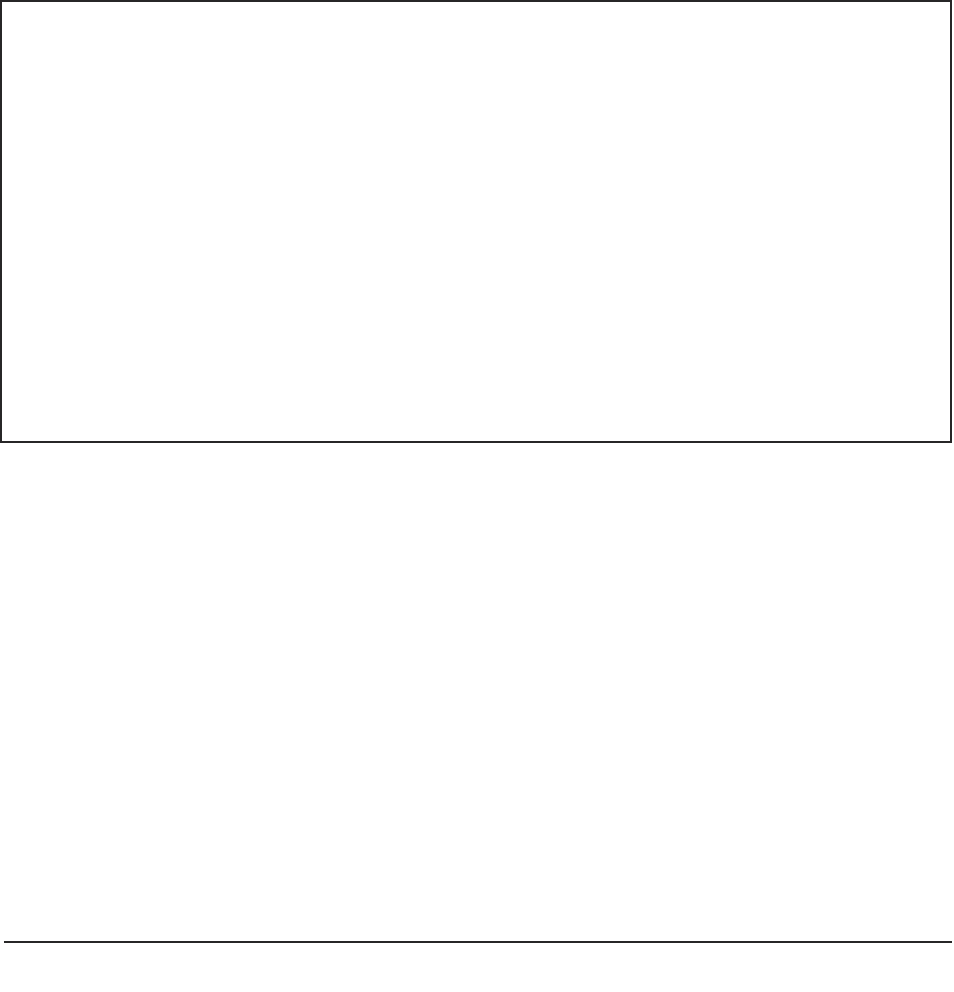

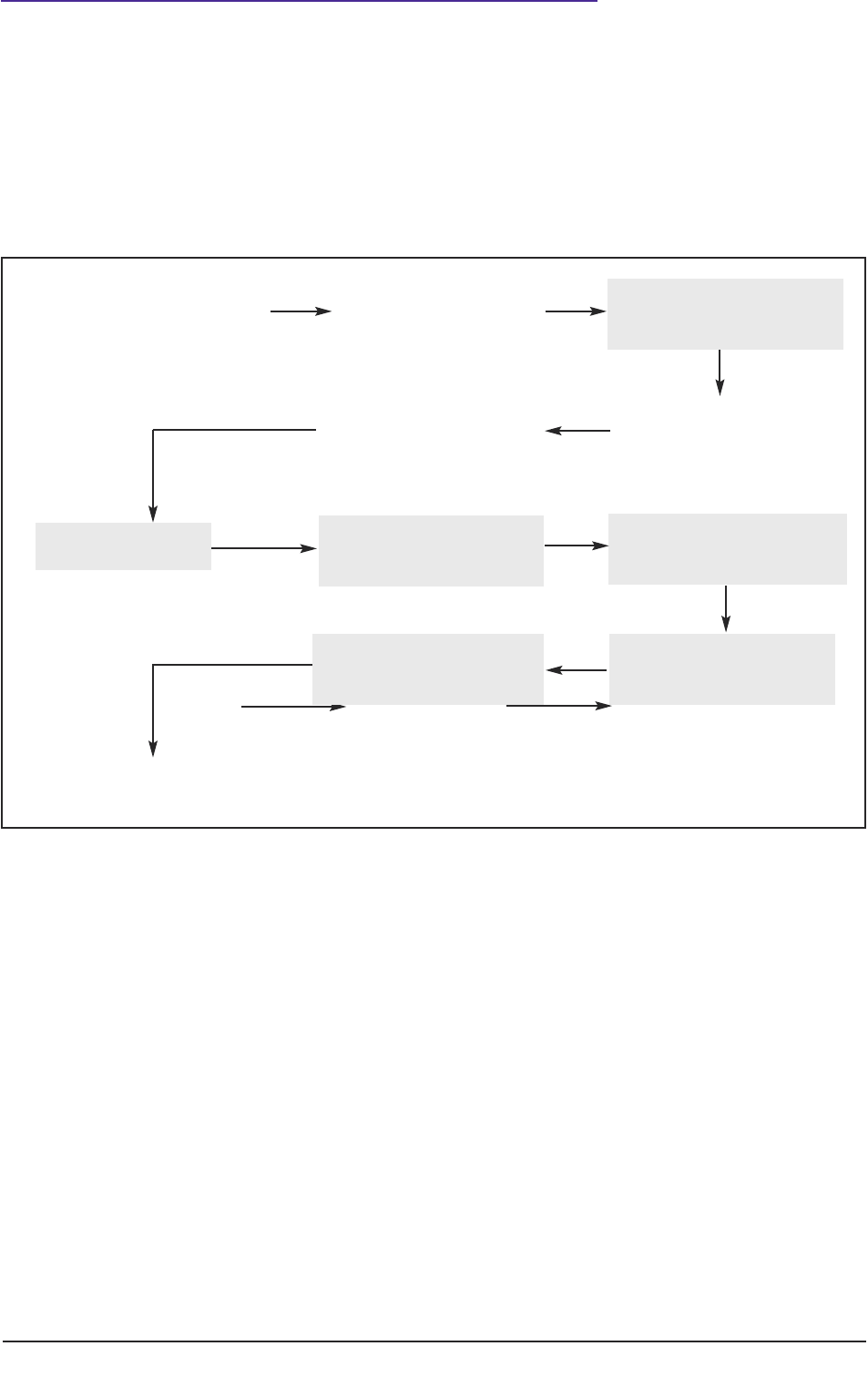

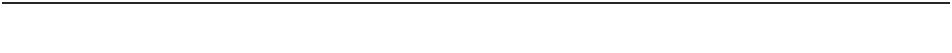

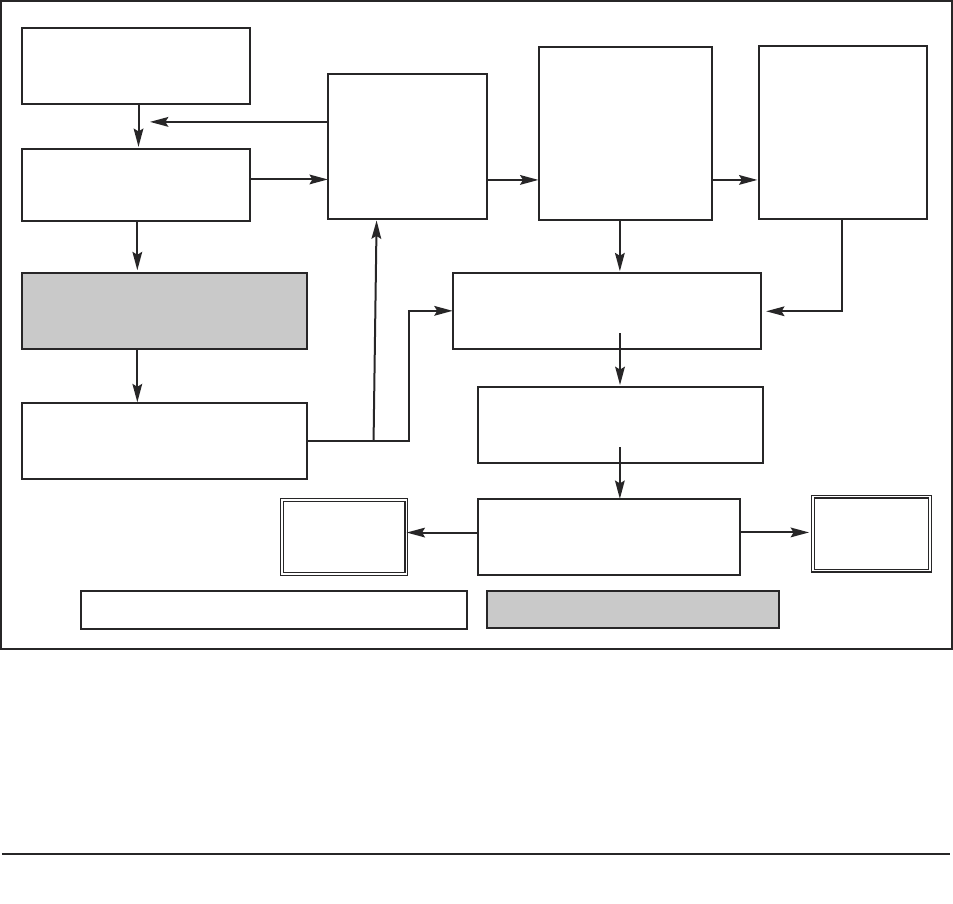

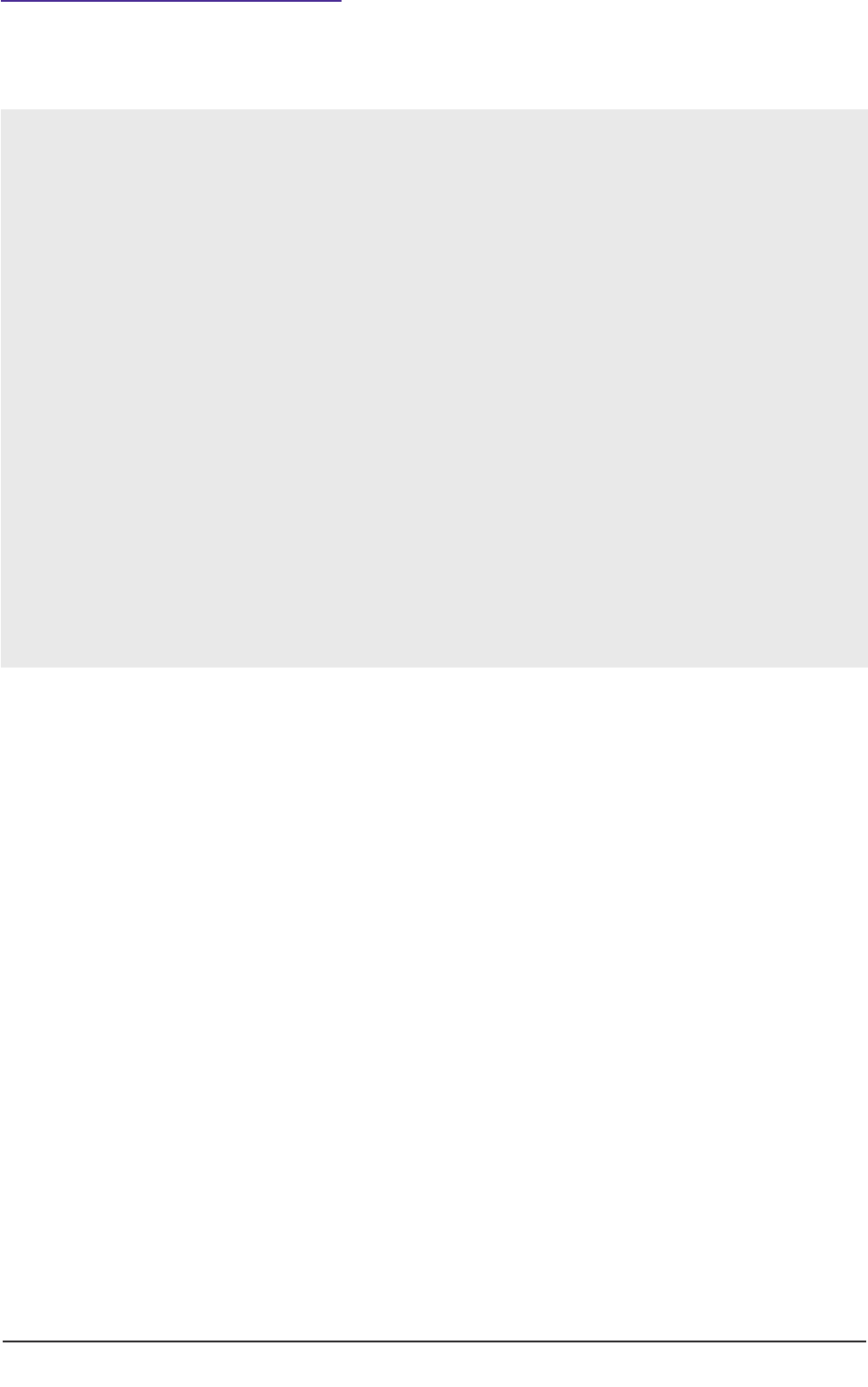

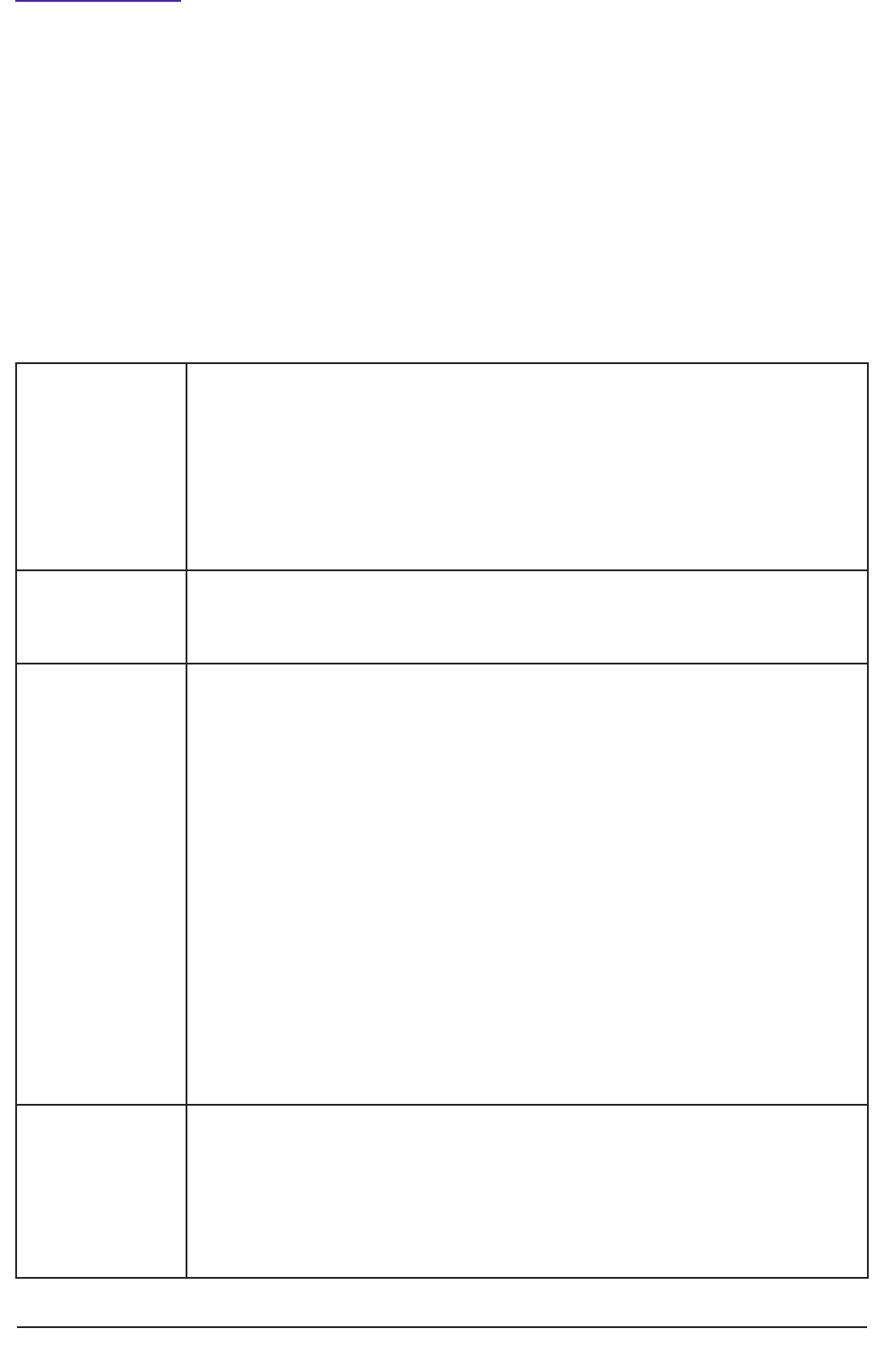

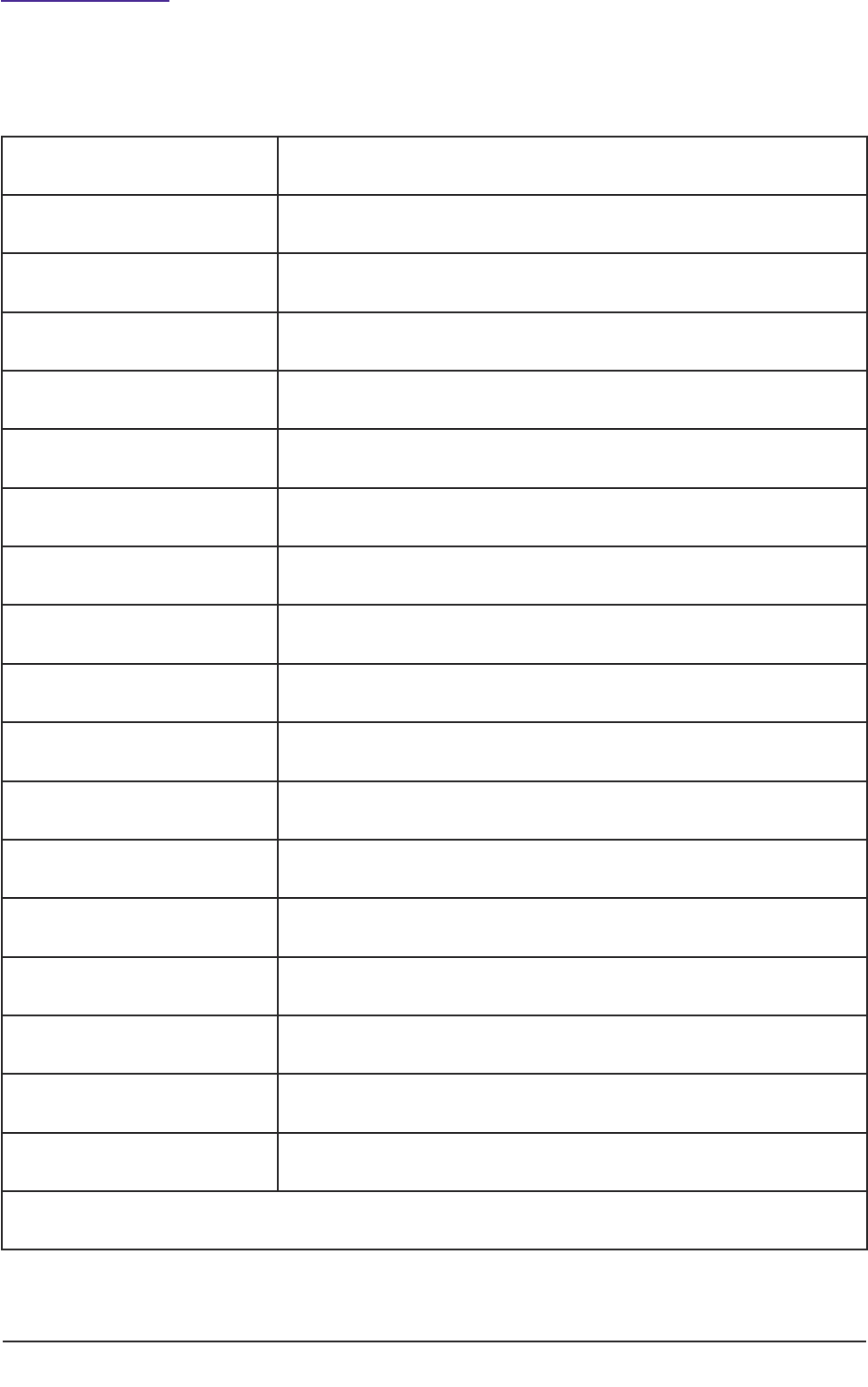

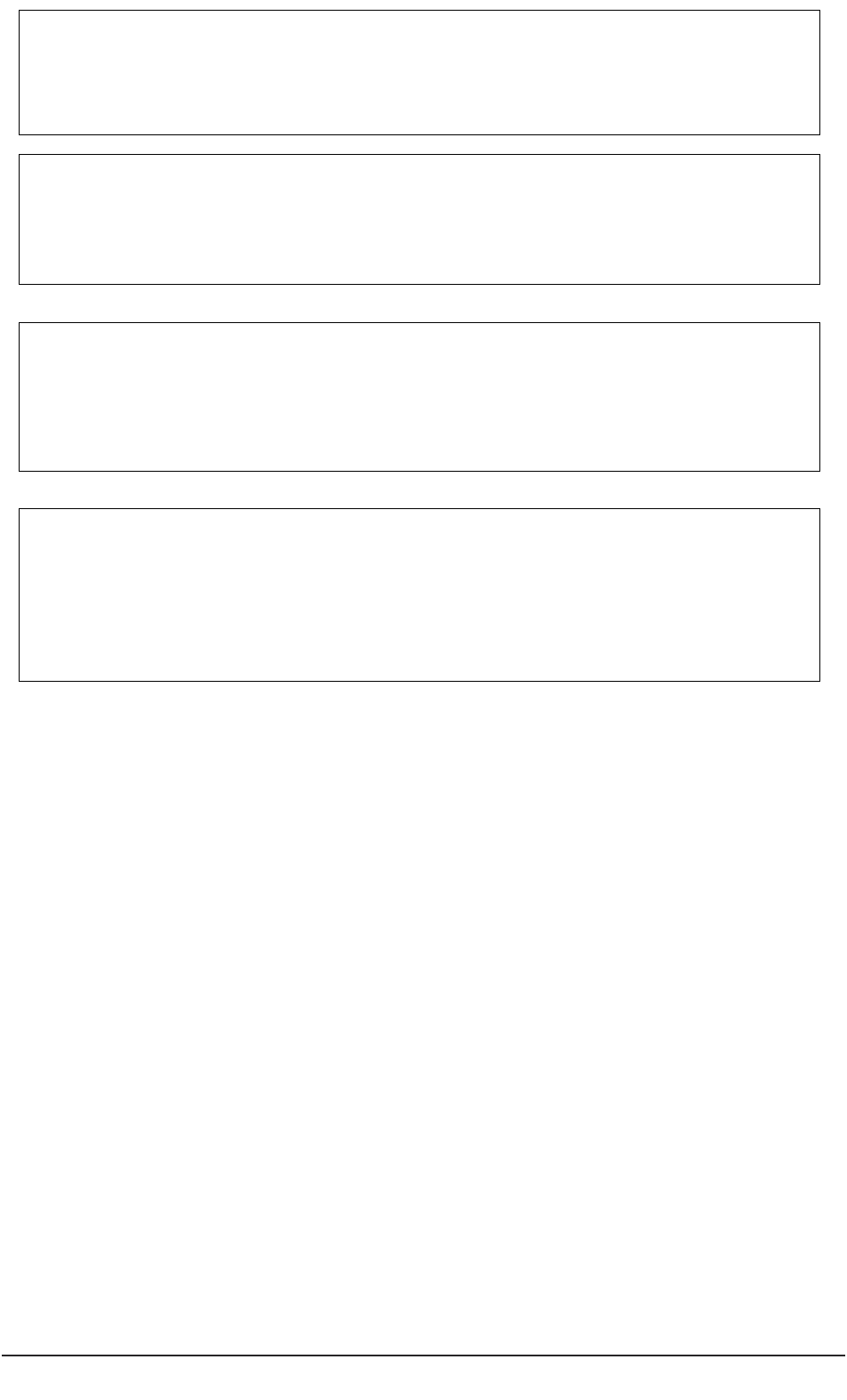

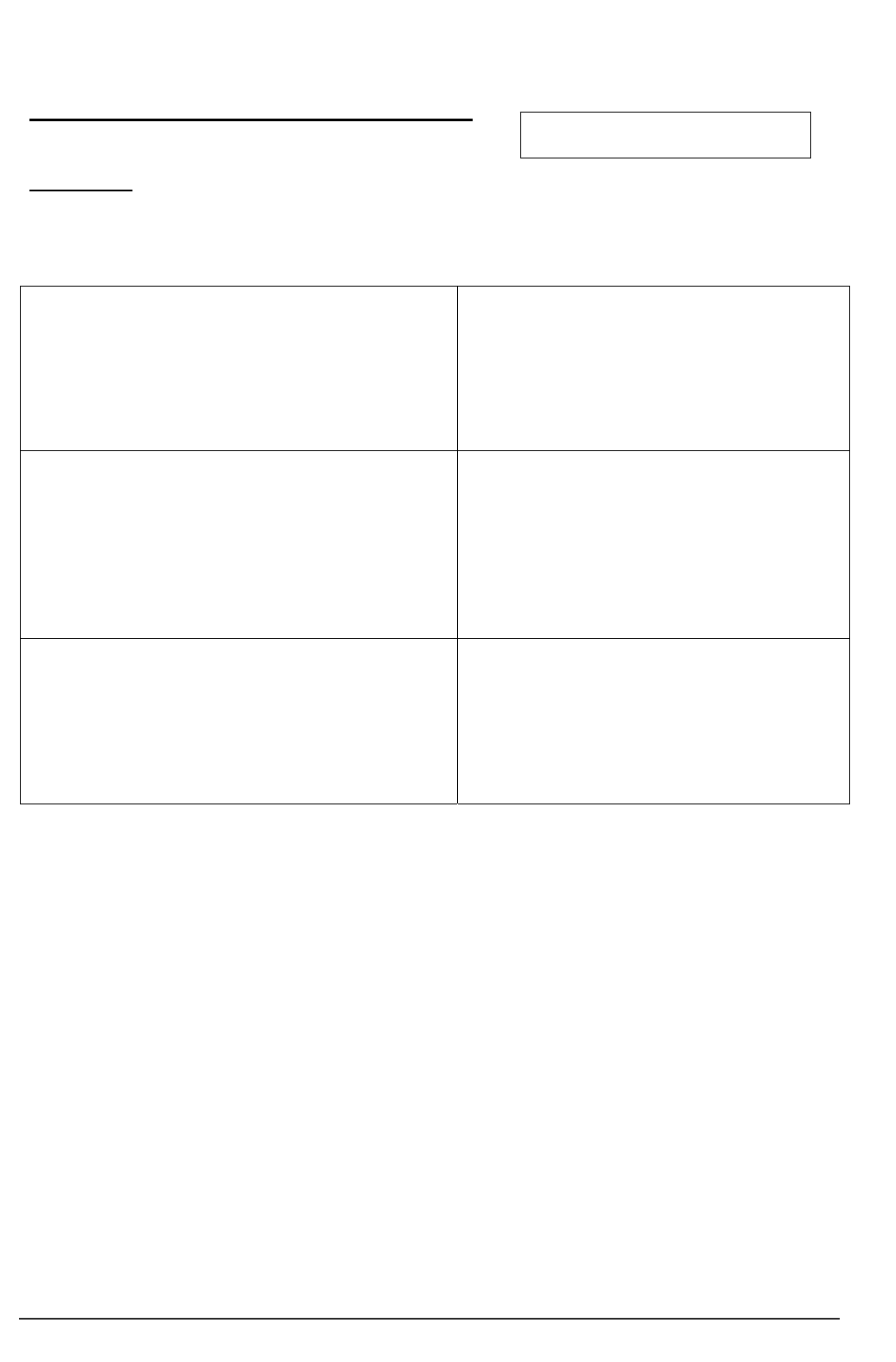

Taking stages of the ‘research process’ as a starting point (see figure 1), the practical guide

works through the detail of necessary modifications in order that projects meet the

requirements of the Mental Capacity Act.

In the United Kingdom, the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care

(DH, 2004b) provides a broad definition of research ‘as the attempt to derive generalisable

new knowledge by addressing clearly defined questions with systematic and rigorous methods’.

The definition is intended to cover different methodologies of research (quantitative and

qualitative) conducted in a wide range of settings with people who may be members of the

public, recipients of health or social care services or employees of such agencies.

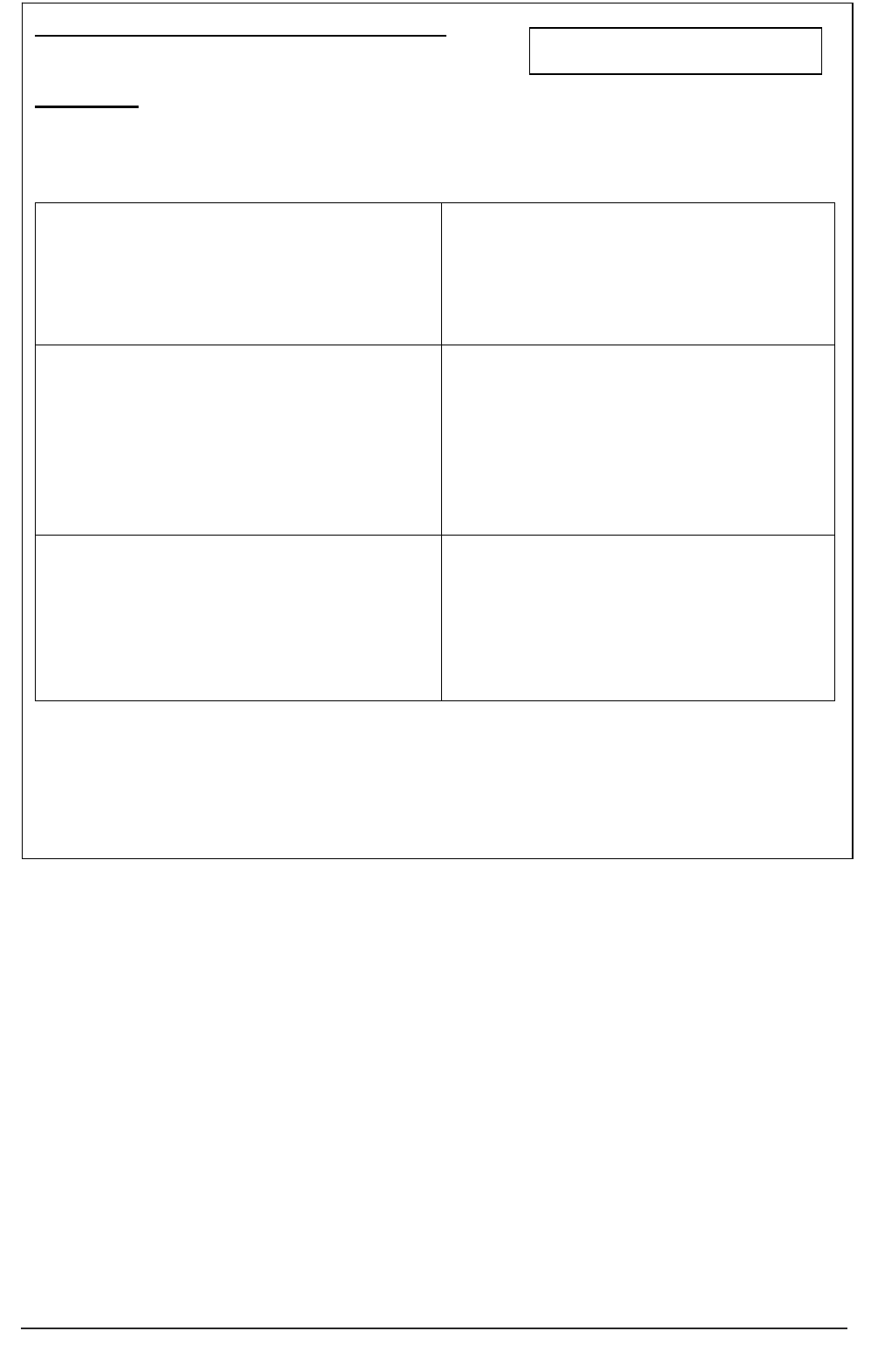

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the research process for conducting research with human

participants.

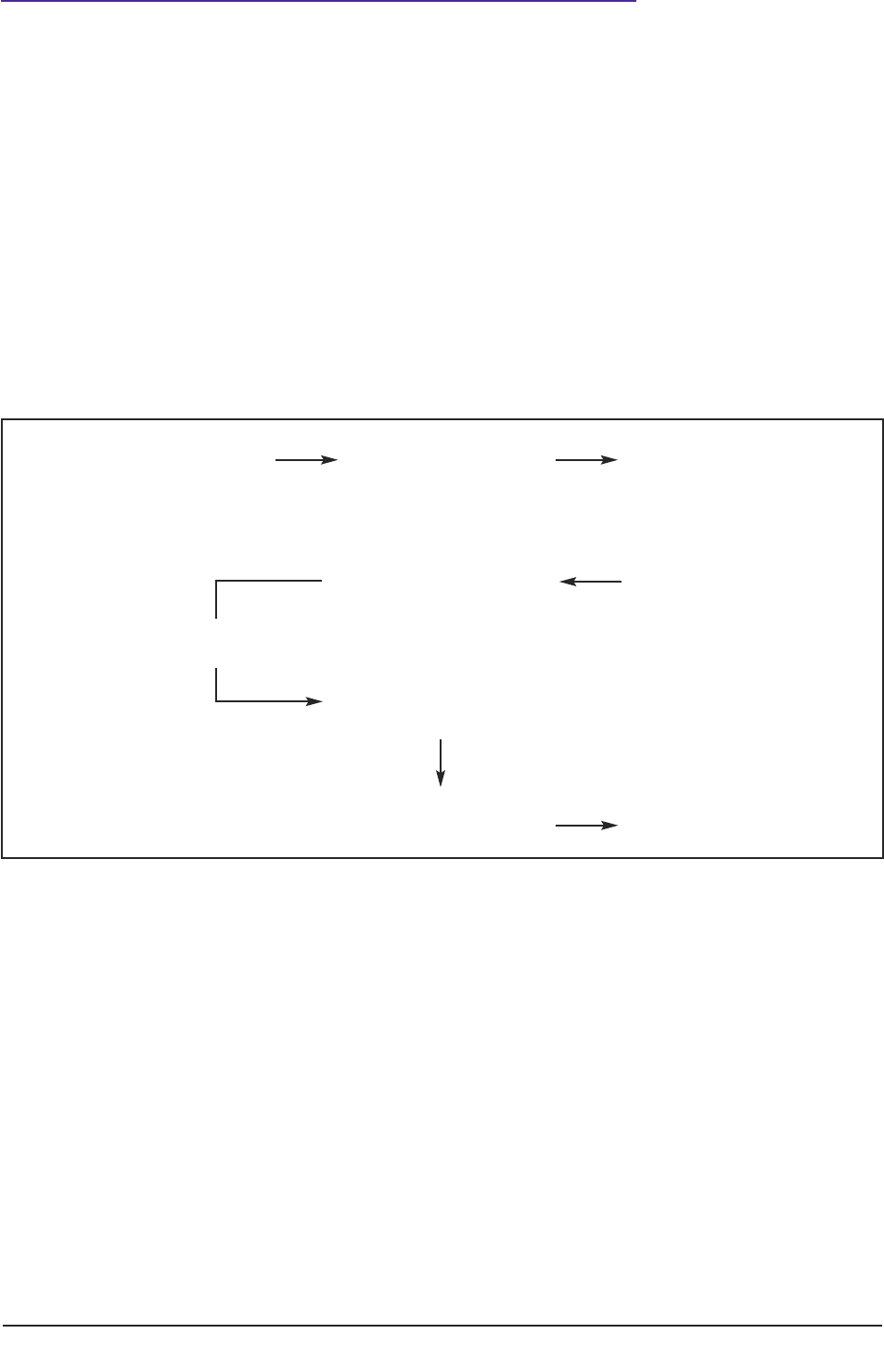

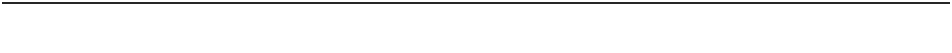

Figure 1 depicts a schematic representation of the ‘research process’ whilst Figure 2 (page

4) indicates key modifications to that process so that the study meets legal requirements of

the Mental Capacity Act (2005), when conducting research with participants not having the

capacity to consent to their participation.

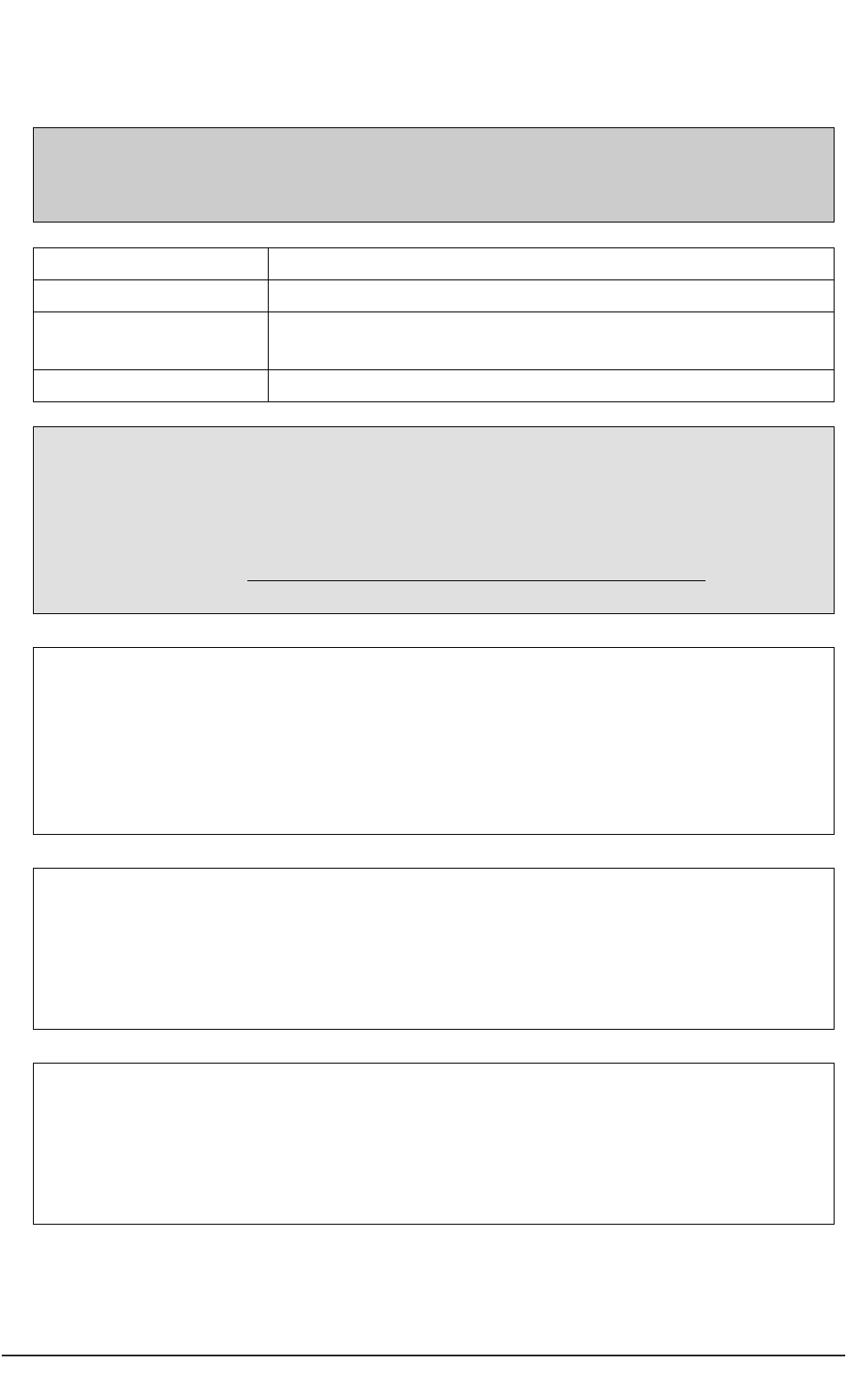

Key modifications to the research process entail:

■ changes to the process of gaining ethical approval, for example by the completion

of supplementary forms and submission to ‘flagged’ NHS Research Ethics

Committees (see 2.2);

■ explicit assessment of the capacity to consent (see 3.1–3.7);

General ideas,

conduct literature review

Complete application

for ethical review

Gain favourable

ethical opinion

Recruit participants

Enhance capacity

to decide

Establish lack

of capacity

Conduct project

Analyse data

Disseminate findings

Prepare protocol

Seek consent

Consult with others

Appraise participant

involvement with project

A practical guide for researchers 7

■ procedures for ensuring consultation with others (see 4.1–4.5);

■ thorough consideration of benefit and risk to the participant; and

■ appraisal of an individual participant’s involvement with the project (see 5.1).

Figure 2: Modifications to the research process to meet requirements of the Mental Capacity Act.

Shaded areas in Figure 2 represent actions by a researcher which are different from or

additional to those required when conducting research with participants who can consent

to their participation.

8 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

Section 2: Ethical scrutiny

2.1 Principles of ethical scrutiny

Guidance and standards for the ethical conduct of research within medical and health care

settings have developed significantly over the past ten to 15 years (DH, 2005). Similar

standards of governance have been extended to ‘student research’, which apply to research

conducted as part of educational or professional training (Doyal, 2005; BPS, 2004a). Most

universities have established systems for the ethical review of research at departmental,

faculty, school or pan-university level. The equivalent systems for scrutiny within social care,

until recently, have been less well-developed (DH, 2005). From January 2009 a national

Social Care Research Ethics Committee (SCREC) will operate within the framework of the

National Research Ethics Service. (See

http://www.scie.org.uk/networks/screc/index.asp.)

A fundamental principle underlying ethical practice is ‘informed consent’. This principle

has been embedded in medical research for some time and has been extended to other

kinds of research. The Nuremberg Code and the subsequent World Medical Association

Declaration of Helsinki promoted ethical standards for the conduct of medical and

biomedical research with human participants. The two most important standards were:

■ voluntary informed consent of subjects; and

■ scientifically-valid research design that could produce fruitful results for the good

of society. (USA DH, 2004; BPS, 2004a, 2004b, 2005, 2008).

Ideally all participants of research projects should be capable of providing well-informed

and considered consent. However, the exclusion of participants who cannot decide for

themselves could deprive many people of access to the opportunity of active participation

in research and potentially of access to innovative interventions and procedures. Herring

(2006) in Medical Law and Ethics suggests

‘The Mental Capacity 2005 … establishes the right balance between the need for research to

bring benefit or information and the need for protection against exploitation and abuse. It

also seeks to ensure that any increased risk of the research, over and above that risk associated

with the condition or treatment itself, is either proportionate to the potential benefit to that

individual, or, in the case of research to provide knowledge, the risk is minimal.’

The researcher’s role, in addition to reaching a judgement about the ability of a

participant to give consent, is also to consider the balance of the benefit of participation

with an evaluation of ‘proportionate risk’.

The following paragraphs of this practice guide describe how a researcher could begin to

ensure these ethical standards are met at the project design phase of the research process.

A practical guide for researchers 9

2.2 Procedure for ethical review

All projects intending to recruit participants lacking capacity to consent must meet the

ethical approval of ‘appropriate bodies’ (MCA, Section 30(4)). As of 2008, projects can be

submitted to one of a small number of ‘flagged’ NHS research ethics committees (NHS

RECs). (See Appendix 2 for details and additional information.) The procedure of

submission to ‘flagged’ RECs applies to any project involving patients or clients of health

or social care services, and members of the public recruited via university or other research

centres. Scrutiny by a ‘flagged’ NHS REC would be in addition to ethical scrutiny internal

to the university or research organisation.

In addition to the standard online application, applicants also need to complete

supplementary forms. Supplementary forms can be downloaded from the website of the

National Research Ethics Service and are also provided in Part 2 of this practical guide.

There are three key questions on the supplementary forms requiring information

additional to that on the standard application form:

■ Can the project be as effectively undertaken with participants who have the

capacity to consent?

■ Is the research about an impairing condition that affects the person?

■ Does the research concern treatment or care of that condition?

During the course of conducting a project, researchers may become aware that

participants who initially had given valid consent have lost that capability in later stages of

the project. In order legally to conduct the research, the usual research process would

need to be halted, the protocol revised and ethical opinion re-sought before non-

consenting participants could again participate (MCA, Section 34 (2)). The Act makes

provision for such research via the Loss of Capacity During Research Project Regulations.

The relevant supplementary form is reproduced in Part 2(2) and is available on the NRES

website.

2.3 Intrusive research

The Mental Capacity Act (2005) applies in respect of research that is defined as

‘intrusive’, that is, research that would normally require the consent of a person with

capacity. It applies to clinical trials of treatments and procedures but does not apply (at

present) to trials, of medicinal products (known as CTiMPs) for which there are separate

regulations (The Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations, 2004).

The MCA Code of Practice, published in 2007, provides examples of research relating

mainly to treatment and care. However, the list is followed by the statement

‘…the Act can cover more than just medical and social care research. Intrusive research which

does not meet the requirements of the Act cannot be carried out lawfully in relation to people

who lack capacity.’

The definition of ‘intrusive research’ in the Mental Capacity Act is deliberately wider than

health or medical research as it includes social care research. The following types of

research were listed in the Act’s Draft Code of Practice (DH, 2006), but omitted from the

10 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

published Code of Practice (the primary audience for the Code are those who are under a

duty to have regard to its provisions):

■ clinical research into new types of treatments (except clinical trials of medicines

that are covered by separate regulations);

■ health or social care services research to evaluate the effectiveness of a policy

intervention or service innovation;

■ research in other fields, (e.g. criminal justice, psychological studies, lifestyle or

socio-economic surveys);

■ research on tissue samples (i.e. blood or spare tissue removed during surgical or

diagnostic procedures) – also covered by the Human Tissue Act, 2004;

■ research on health and other personal data collected from records; and

■ observations, photography or videoing of people without capacity some of which is

done covertly so as not to distract the person

The above types of research are examples of ‘intrusive research’. Not all of them are

invasive, in the sense of physically taking something to or from a person’s body.

This meaning of ‘intrusive’ therefore leads to a broadening of the range of research which

would be unlawful if conducted with people who have the capacity to consent, but without

their consent (MCA Section 30 (2)). This also potentially applies to research which

hitherto may have been considered as not requiring the participant’s explicit consent, for

example observational studies conducted within care settings or studies using data

obtained from internet-based surveys (BPS, 2007).

Where adults lack the capacity to consent, the legal position in England and Wales is that

no other person can be authorised to give proxy consent. The sole exception at present

concerns research in connection with clinical trials of medicinal products, which require

that a legal representative give ‘informed consent’ (The Medicines for Human Use

(Clinical Trials) Regulations, 2004). For all other types of research likely to involve

participants not having the capacity to consent, researchers must demonstrate that they

have procedures in place to consult others about the involvement of prospective

participants.

2.4 Research that does not require consent

Some types of research do not require consent: this applies to all persons whether or not

they have the capacity to consent. Section 11.7 of the MCA Code of Practice lists the

following types of research:

■ Research involving data that has been anonymised and cannot be traced back to

individuals.

■ Research on human tissue that has been anonymised (Human Tissue Act 2004).

The research must have ethical approval.

■ Research using confidential patient information (Health Service (Control of

Patient Information) Regulations 2002 Section 1.2002/1438). This requires an

application to the Patient Information Advisory Group (PIAG), which can

A practical guide for researchers 11

determine ‘whether the common law duty of confidentiality can be lifted for

activities that fall within defined medical purposes, (including research) where

anonymised information will not suffice and consent is not practicable’.

In contrast to healthcare research requiring access to health and clinical records,

research using material derived from records held by social care organisations requires

the explicit consent of the individual, on the basis of the common law duty of

confidentiality. However, supplementary guidance (DH and WAG, 2008) to the MCA

Sections 30–34 states:

‘secondary legislation made under Schedule 3 (Data Protection Act, 1998) permits processing

of sensitive data where that is necessary for research, provided that the processing is in the

substantial public interest, that it does not support measures or decisions that affect

individual’s care or treatment and does not and is not likely to cause substantial damage or

distress to the subject or anyone else.’

Whilst access to NHS patient information is covered by the Act and the Code of Practice,

use of confidential information from other sources is not. The main issue is how to gain

access to partially anonymised records rather than to the full record. One respondent to

the consultation phase of this practice guide reported ‘records may be released under

special licence, the mechanism being specific to government departments/agencies; this

does not require the consent of the individual’.

In the course of preparing this practical guide, the author has encountered variation

between local authorities in the interpretation of the Data Protection Act, 1998 in relation

to the release of material for research purposes.

2.5 Seeking consent to participation in research

A critical step in the research process is the researcher seeking the consent of participants

to take part or to refuse. The process of obtaining voluntary and informed consent involves

two complementary and reciprocal decisions:

1. The participant makes a decision about whether to take part or to refuse to be

involved in a research project.

2. The researcher judges the quality of that decision. If the quality of that decision

meets certain ethical standards, the person is considered to have consented to

participate or to have refused.

Ethical standards framing this decision are:

■ freedom of choice and absence of coercion;

■ having general understanding of the research and its intentions; and

■ understanding of possible risks and benefits.

In terms of decision-making under the Mental Capacity Act, the key question for the

researcher is, does the person have the capacity to consent (or refuse) at the time the

decision needs to be made?

The National Research Ethics Service recommends that researchers allow the prospective

participant ‘sufficient time to reflect on the implication of participation in the study’

12 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

(NRES, 2007). This practical guide suggests that in judging the time lag between providing

information about a project and seeking consent, the researcher may need to take heed of

the nature of the project and the particular requirements of the project participants.

General ideas,

conduct literature review

Complete application

for ethical review

Gain favourable

ethical opinion

Recruit participants

Enhance capacity

to decide

Establish lack

of capacity

Conduct project

Analyse data

Disseminate findings

Prepare protocol

Seek consent

Consult with others

Appraise participant

involvement with project

A practical guide for researchers 13

Section 3: Assessing capacity to consent

3.1 Recruitment of participants

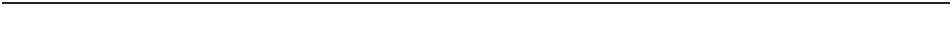

With reference to Figure 2 reproduced below, having secured a favourable ethical opinion,

the next stage in the research process is the recruitment of participants.

Figure 2: Modifications (shaded areas) to the research process to meet requirements of the Mental

Capacity Act.

In the course of prearing the project protocol the researcher will have specified criteria for

inclusion and for exclusion of participants, together with a description of procedures for

the recruitment of participants. For prospective participants who lack the capacity to

consent, the most likely recruitment methods will be via clinical or care teams, care

agencies, or service user and carer organisations. Such ‘intermediaries’ play a significant

role in the research process because of their knowledge of the sample of people from

which participants may be selected.

3.2 Assessing capacity to consent to participation in research

What is ‘mental capacity’?

Mental capacity is the ability to make a decision (MCA, Code of Practice, 2007). This

includes the ability to make a decision that affects daily life as well as the ability to make

decisions that may have legal consequences.

14 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

What is ‘lack of capacity’?

Section 2 (1) Mental Capacity Act 2005 states:

‘For the purposes of the Act, a person lacks capacity in relation to a matter if at the material

time he is unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter, because of an

impairment of, or disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain.’

Key indicators in judging whether a person lacks capacity are:

■ the presence of an impairment or disturbance (disability, condition) that affects

the way the person is able to think;

■ whether the impairment is permanent, temporary or fluctuating;

■ the nature of the decision – the person may be able to make decisions about some

things but not others; and

■ the timing of the decision – the person may be able to make a decision on the

matter in question if the decision is delayed for another time.

In many research projects, the person who seeks consent is also the person who judges

whether or not the prospective participant has the capacity to reach this decision

themselves. This person is usually the researcher who is directly undertaking the research

activity. Researchers may need to assess the capacity of participants at different stages of the

project (if the project is to be conducted over a span of time) and possibly in connection

with different research questions.

Large-scale projects may involve teams of researchers on different sites with a Chief

Investigator taking overall responsibility for the governance of the project. The Chief

Investigator may not be the person who routinely seeks participant consent but needs to

ensure that systems are in place to safeguard the welfare of all prospective participants,

whether or not they have capacity to consent.

Responsibilities of different parties in the research process are outlined in Appendix 3.

3.3 Applying the Five Statutory Principles of the MCA to judge

whether a (prospective) participant has the capacity to

consent

The Mental Capacity Act provides a decision-making framework that researchers could

adopt to enable them to have a ‘reasonable belief’ that a person lacks capacity to consent

to participation in research. In most circumstances, researchers will be able to undertake

the assessment of capacity themselves and it is unlikely that an expert professional opinion

about capacity will be required.

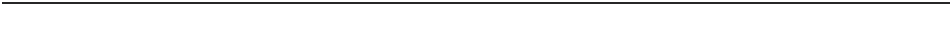

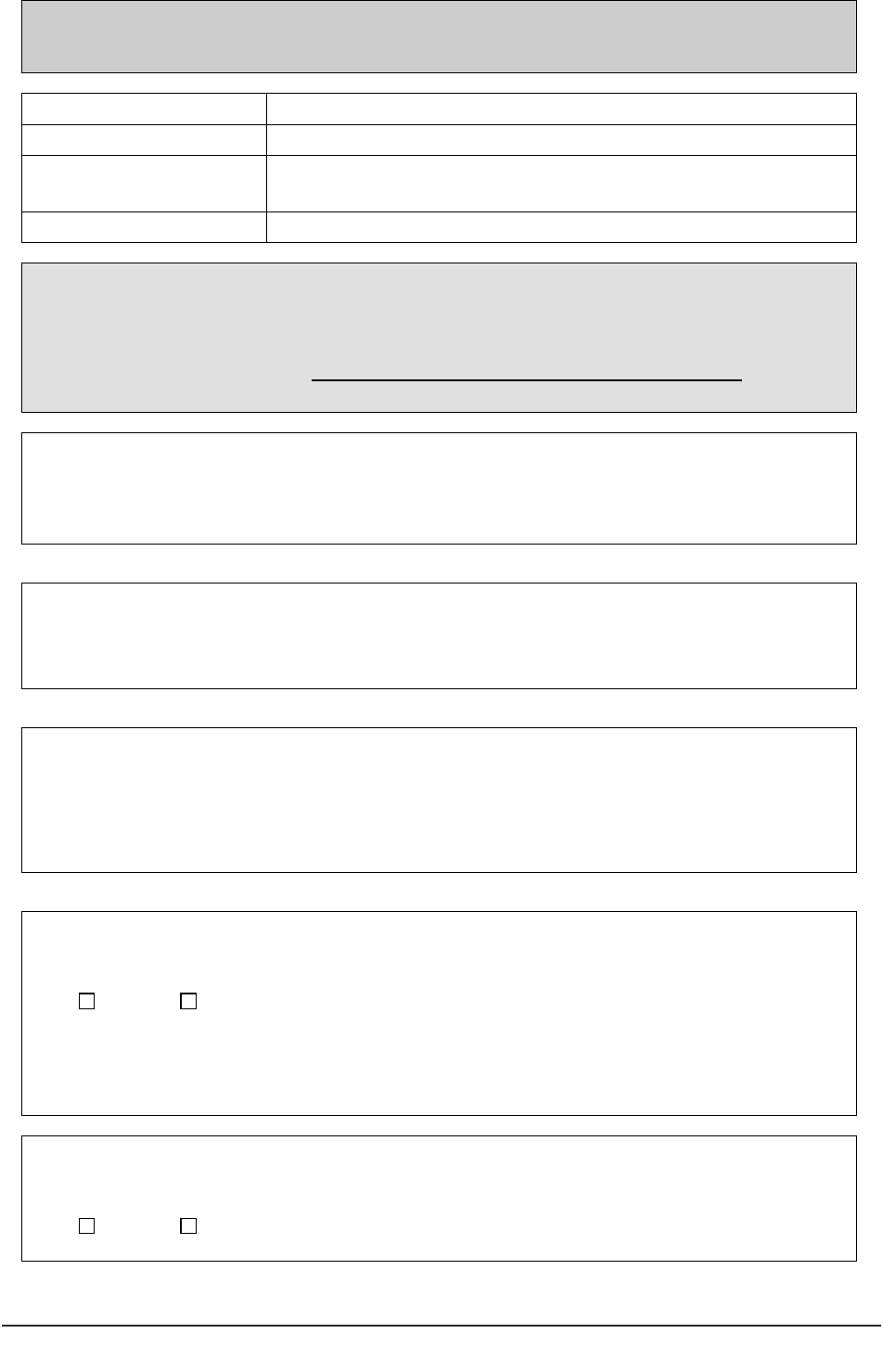

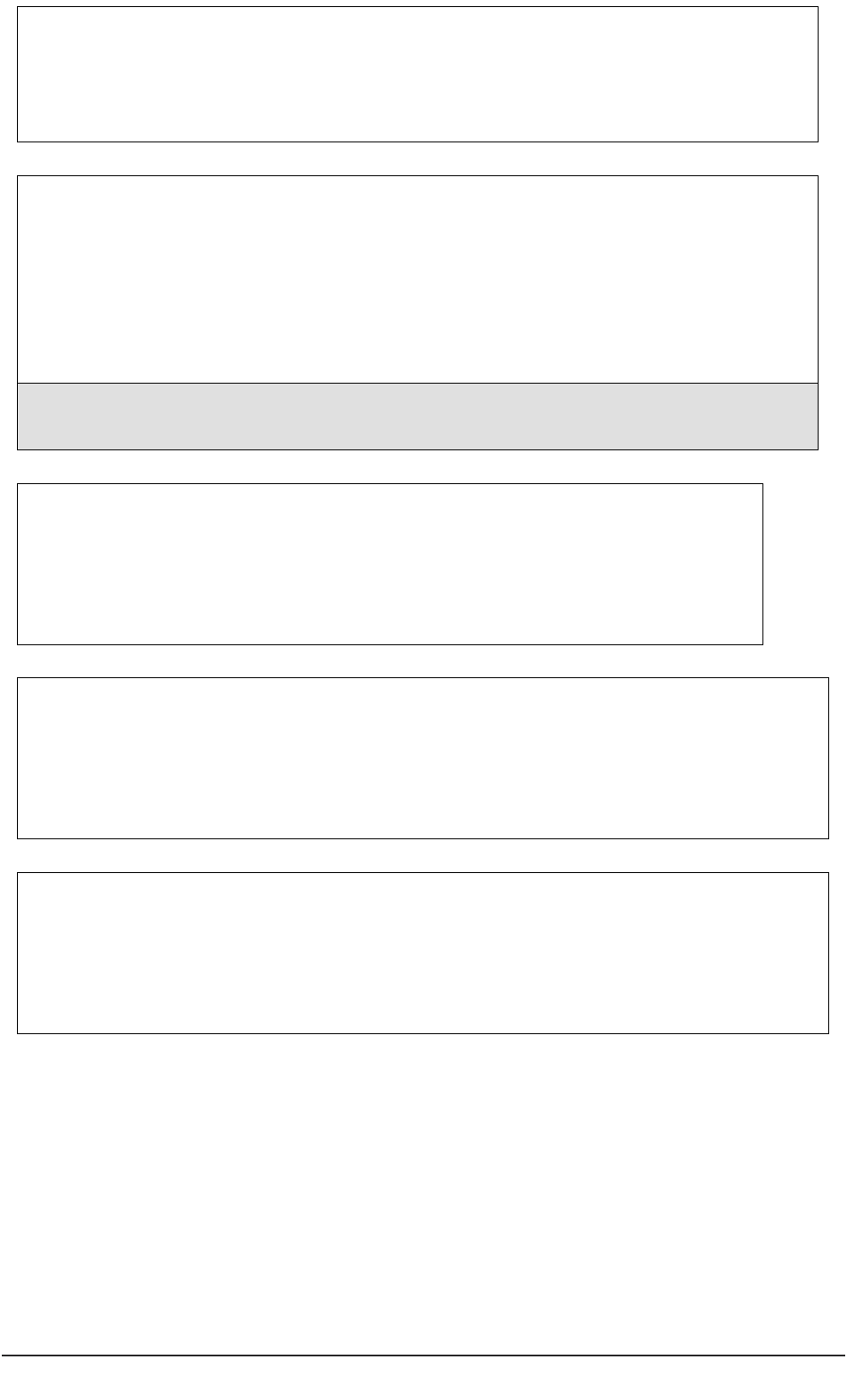

In the following sections, (3.4–3.7) the five principles of the MCA 2005 are stated,

examined in some detail and applied to the research context. The reader may wish to bear

in mind the key question or decision: ‘Does the person have the capacity to consent, at the

time that the decision needs to be made?’

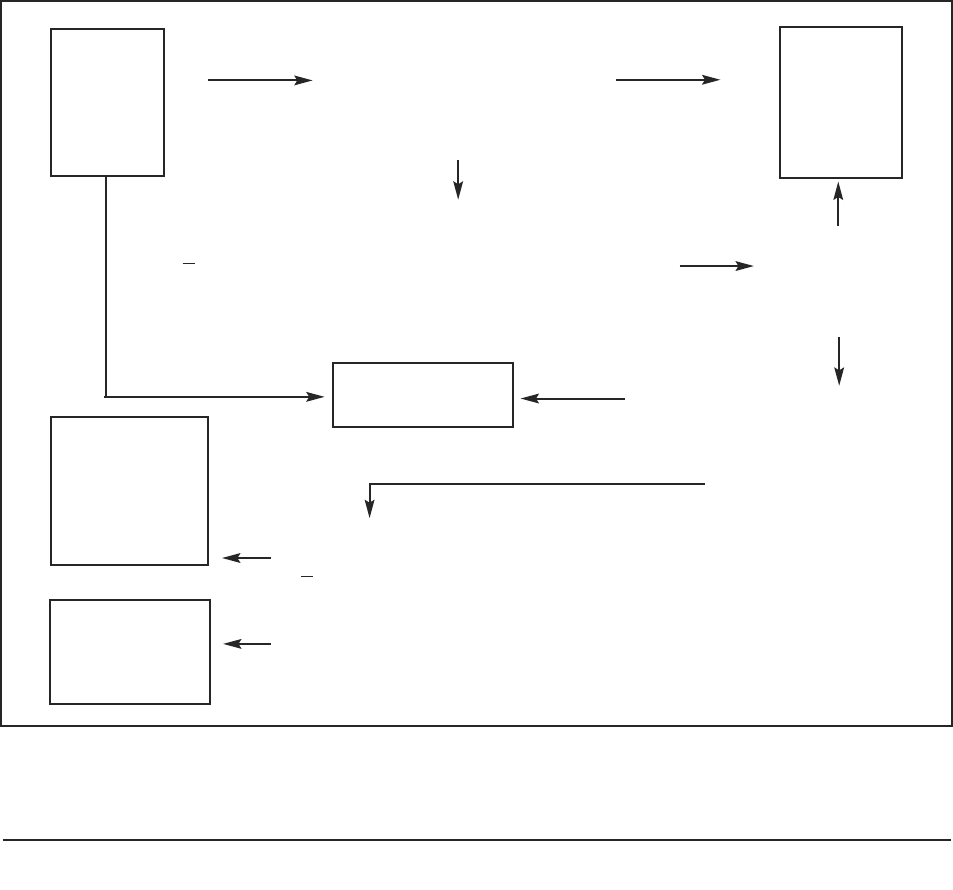

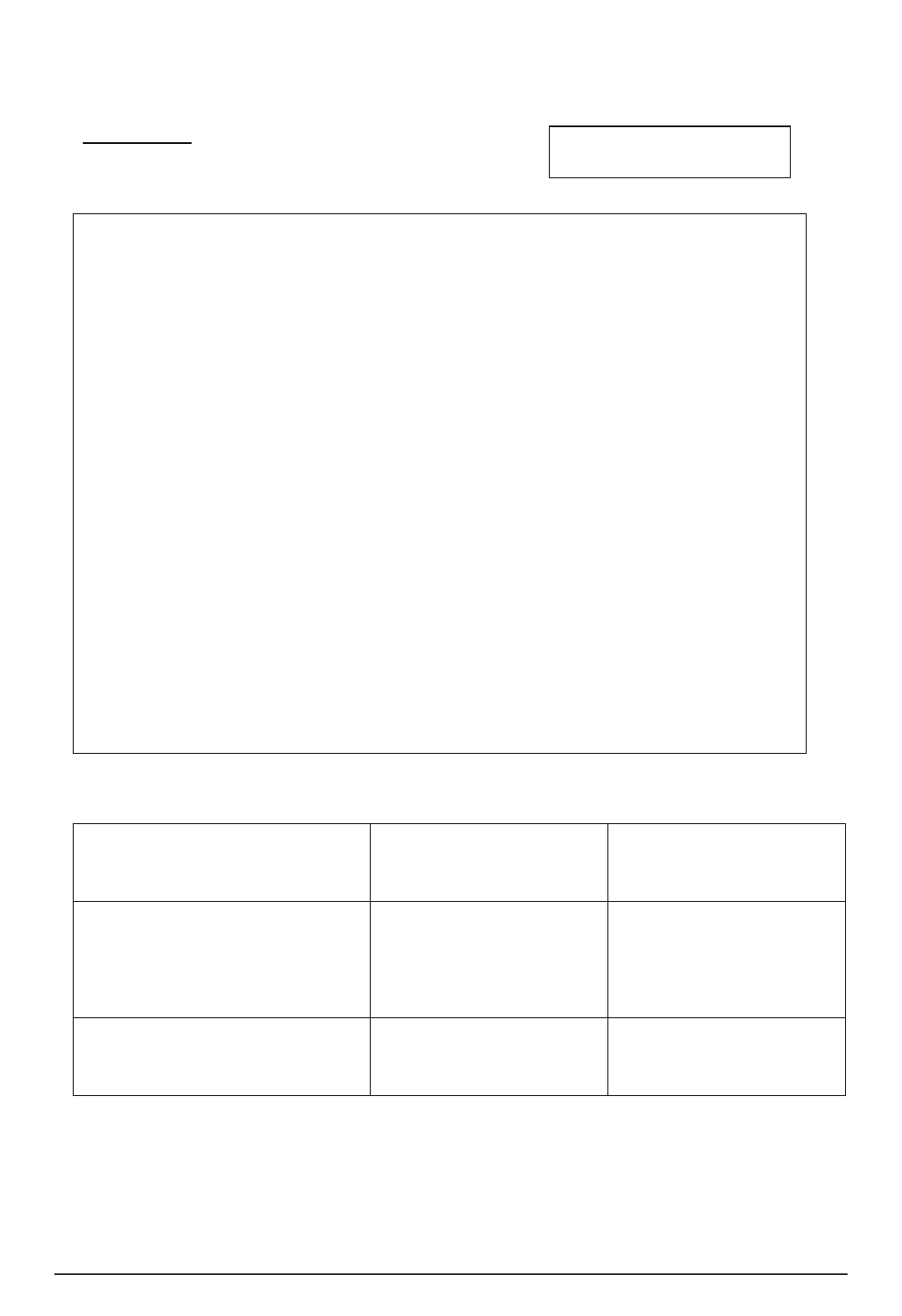

Figure 3: Decision-tree for researchers in assessing capacity to consent to participate in research.

The person

does not have

the capacity

to consent

The person

can consent

Researcher

accepts

person’s

decision

Can the

person reach

a decision?

Does the person have an

impairment affecting their

ability to reach the decision?

(see 3.7)

Can the person reach a

decision themselves to

agree or to refuse to

participate? (see 3.4)

EXCLUDE

Could the person’s decisional capacity be enhanced by

◆ Providing ‘accessible’ information about project

◆ Changing the timing and location of decision

◆ Providing education about research (see 3.5)

Does the person

◆ Understand about research?

◆ Understand consequences of taking part of refusing?

◆ retain, weigh up and use the information about the project?

◆ Communicate the decision?

(see 3.7)

yes

yes

yes

yes

no

yes

no

no

no

no

Is the

person

aged 18

or over?

A practical guide for researchers 15

The process in summary is:

1. The researcher presumes that the participant has the capacity to consent or to

refuse.

2. The prospective participant decides whether to participate or to refuse.

3. The researcher judges the quality of that decision and considers whether the

participant has agreed or refused to participate on the basis of

● freedom of choice and absence of coercion;

● having general understanding of the research and its intentions; and

● understanding of possible risks and benefits.

4. If the researcher is certain that the decision reached by the participant meets these

standards, the researcher can judge that the person has consented to or refused

participation.

5. If not certain, the researcher can use the following steps (Sections 3.4–3.7) which

are represented diagrammatically (Figure 3) as a flowchart of questions to consider

when planning and conducting this phase of the research project. By asking these

questions the researcher can reach a judgement about the nature of a participant’s

consent. A checklist based on these questions is provided in Part 2 of this guide.

The capability of a prospective participant to reach a decision themselves may be

enhanced by:

■ Amending the Information Sheet about the project, such as by the use of

‘accessible language’, using an interpreter or reader of written information,

providing only essential information about the project.

■ The National Research Ethics Service has provided extensive guidance on

improving the language and presentation of information sheets and consent

forms in order for them to be better understood by participants. (see

http://www.nres.npsa.nhs.uk/ rec-community/guidance/#informedConsent).

■ Organisations such as Connect and Medicines for Children Research Network

have produced suggestions about format and structure of information sheets.

■ Providing information in alternative formats, such as aurally for people with

visual disabilities, as well as in written formats. Consider conveying information

with diagrams and use of colour.

■ Breaking down complicated information into smaller points.

■ Altering the timing or location that consent is sought – would capacity to

consent be improved if the decision were delayed, sought at a different time of

day or in a different location?

■ Allowing the person time to reach the decision.

■ Encouraging discussion with others, such as family or friends about the project.

■ Providing education about research. Some people may not have any previous

experience of research – would training or discussion about the general idea of

research help the person to reach a decision about a particular project?

■ Responding to questions about the project.

16 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

3.4 Principle 1 of the MCA

A person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that he lacks capacity.

A researcher must assume that prospective participants for a research study have the

capacity to consent, even when they may have a condition that may question that capacity.

The researcher needs to ascertain that the person does not have capacity, and not assume

that they don’t on the basis of their condition, age, appearance or behaviour.

Proof of lack of capacity: the researcher would need to show that, on the balance of

probabilities, the individual lacks the capacity to consent to participation in the research at

the time that the consent is required to be made. See 3.7 below for detail of how this

judgement is reached.

3.5 Principle 2 of the MCA

A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to

help him to do so have been taken without success.

Practical support could enable a potential participant to make their own decision about

their involvement in a research project. Some examples of ways of doing this are provided

in the box below.

■ Being clear about the possible risks of participation as well as advantages and

benefits.

■ Being clear about what is actually required of the participant in conducting the

research.

■ Being clear whether the researcher is seeking consent about research that is

about to take place or is due to take place at some time in the future.

Considering systems for communicating with the prospective participant

■ Use of augmented communication or symbols or ‘talking mats’ (Cameron and

Murphy 2006)

■ Can others assist the person in communicating, whilst at the same time not

influencing the person in reaching a decision?

A person is unable to consent to their involvement if they cannot:

1. Understand information – does the person understand what the research

is about?

Does the person have a general understanding of the research project?

Can the person indicate what is expected of them (section 3.5)?

Have attempts as described above (section 2.2) to enable the participant to

make decisions for himself not been successful?

3.6 Principle 3 of the MCA

A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because he makes an

unwise decision.

Consenting to participate in research that, for example, may involve taking risks, may not

be an unwise decision even if the research is viewed by many as bizarre or unusual.

Potential examples could include studies involving sleep deprivation, extreme cold or the

effects of taking financial risks or hallucinogenic substances. Such research should be

subject as a matter of course, to ethical scrutiny within university or other research

organisations; the greater the degree of risk, the higher the level of scrutiny.

3.7 Reaching a judgment about whether a participant lacks the

capacity to consent to research

Proof of lack of capacity: the researcher would need to show that, on the balance of

probabilities, the individual lacks the capacity to consent to participation in the research at

the time that the consent is required to be made.

The researcher would have to prove that

a) the person has an impairment of the mind or brain that affects how the mind or

brain works; and

b) the impairment affects the person’s ability to consent at the time the consent is

required.

A practical guide for researchers 17

2 Retain information – can the person hold the information in their mind long

enough to use it to make a decision?

Can the person recall information about the research?

Having a poor memory per se is not sufficient grounds for saying that the

participant cannot consent.

3 Use or weigh up the information

Does the (prospective) participant consider the benefits and risks of taking part

in the research?

Can the person identify any consequences of participating or refusing to take

part?

4 Communicate their decision

Is the person unable to communicate their decision in any way, taking into

account any specific language or communication difficulties.

Fluctuating capacity

Can the decision to participate be taken at a time when capacity may have been

regained?

If the answers are NO to the first three of the above questions, then, on the balance of

probabilities, the person cannot reach a decision themselves and cannot consent to

their participation in research.

18 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

The researcher will need to document their judgment and consider whether to exclude

the person from the study or to include them by taking account of the safeguards provided

in the Mental Capacity Act.

A checklist for the researcher is provided in Part 2 of this guide.

3.8 Loss of capacity during a project

Some projects may be designed to include participants who are likely to lose capacity for

shorter or longer intervals during the course of a project.

In general, under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Loss of Capacity During Research

Project) (England) Regulations 2007 (SI2007/679) and The Mental Capacity Act 2005

(Loss of Capacity during Research Project) (Wales) Regulations 2007 (SI2007/837 (W.72),

if a person had given consent at some time in the past and that loss of capacity had not

been anticipated, the researcher would need to judge:

■ whether to make use only of data collected over the period of time that the person

had given consent;

■ whether to continue to collect data, even though the person no longer can give

consent, providing the loss of consent had not been anticipated. In this case, the

A practical guide for researchers 19

researcher would need to seek advice from a personal or nominated consultee and

appraise the participant’s involvement in the project, as described in Section 4

below. The researcher may need to re-apply for approval from a ‘flagged’ Research

Ethics Committee.

Studies designed since the MCA came into effect, would need to anticipate the possibility

of loss of capacity to consent and the researcher would need to take action as described in

earlier sections of this guide, such as the completion of supplementary forms as part of the

procedure for gaining ethical approval.

20 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

Section 4: Consulting with others

4.1 Consulting with others as a way of safeguarding the inclusion

of people who lack the capacity to consent to their

participation

Principle 4 of the Mental Capacity Act states that decisions made for or on behalf of the

person (are) to be made in the person’s best interests.

Principle 5 states that before the act is done, or the decision is made, regard must be had

to whether the purpose for which it is needed can be as effectively achieved in a way that is

less restrictive of the person’s rights and freedom of action

In contrast with many decisions under the remit of the Mental Capacity Act, the decision to

participate in research is not an area where consideration of an individual’s ‘best interests’

applies as described in the MCA (MCA Code of Practice, Section 5.4). The reasoning

during parliamentary debates on the MCA was that sometimes research may not be of

actual benefit to the person. If the principle of ‘best interests’ were rigorously applied,

then persons not having the capacity to consent would be restricted from opportunities for

involvement in research. However, if the research is contrary to the interests of the person

(such as if it were unduly burdensome, restrictive, etc.) then it would not gain ethical

approval and could not legally proceed.

The Mental Capacity Act provides special safeguards for the conduct of research with

participants not having the capacity to consent, which include:

■ scrutiny by an ‘appropriate body’ such as NHS Research Ethics Committee that

projects meet enhanced standards for ethical approval (as discussed in Section 2);

■ consultation with others not involved in the project about the involvement of a

person lacking capacity;

■ assurance that the interests of the participant are considered as having greater

importance than any potential benefit to others; and

■ acknowledgement of signs of objection by the participant, or contravention to an

advance decision or other form of advance statement.

The above safeguards could be considered as variations of Principle 4, the ‘best interests’

principle of the MCA and Principle 5, the ‘least restrictive’ principle.

If considering the inclusion of participants lacking the capacity to consent, the process of

consulting with others and reappraising the participant’s involvement in the light of that

consultation would have been anticipated in the course of seeking approval from a

Research Ethics Committee, prior to the recruitment of participants. However, some

projects may include participants who lose capacity during later stages of a project. In this

case researchers would still need to appraise the individual’s involvement and re-apply for

ethical approval if the project were to continue with the inclusion of non-consenting

participants (The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Loss of Capacity during Research Project)

(England) Regulations 2007 (SI2007/679) and The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Loss of

Capacity during Research Project) (Wales) Regulations 2007 (SI2007/837 (W.72)) .

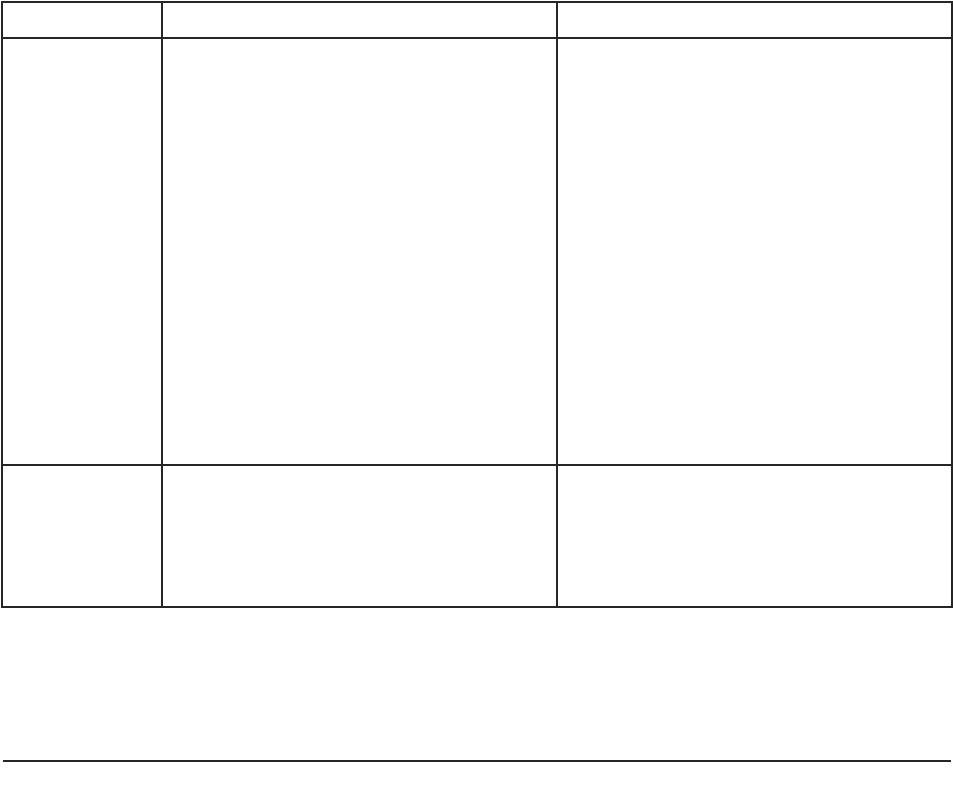

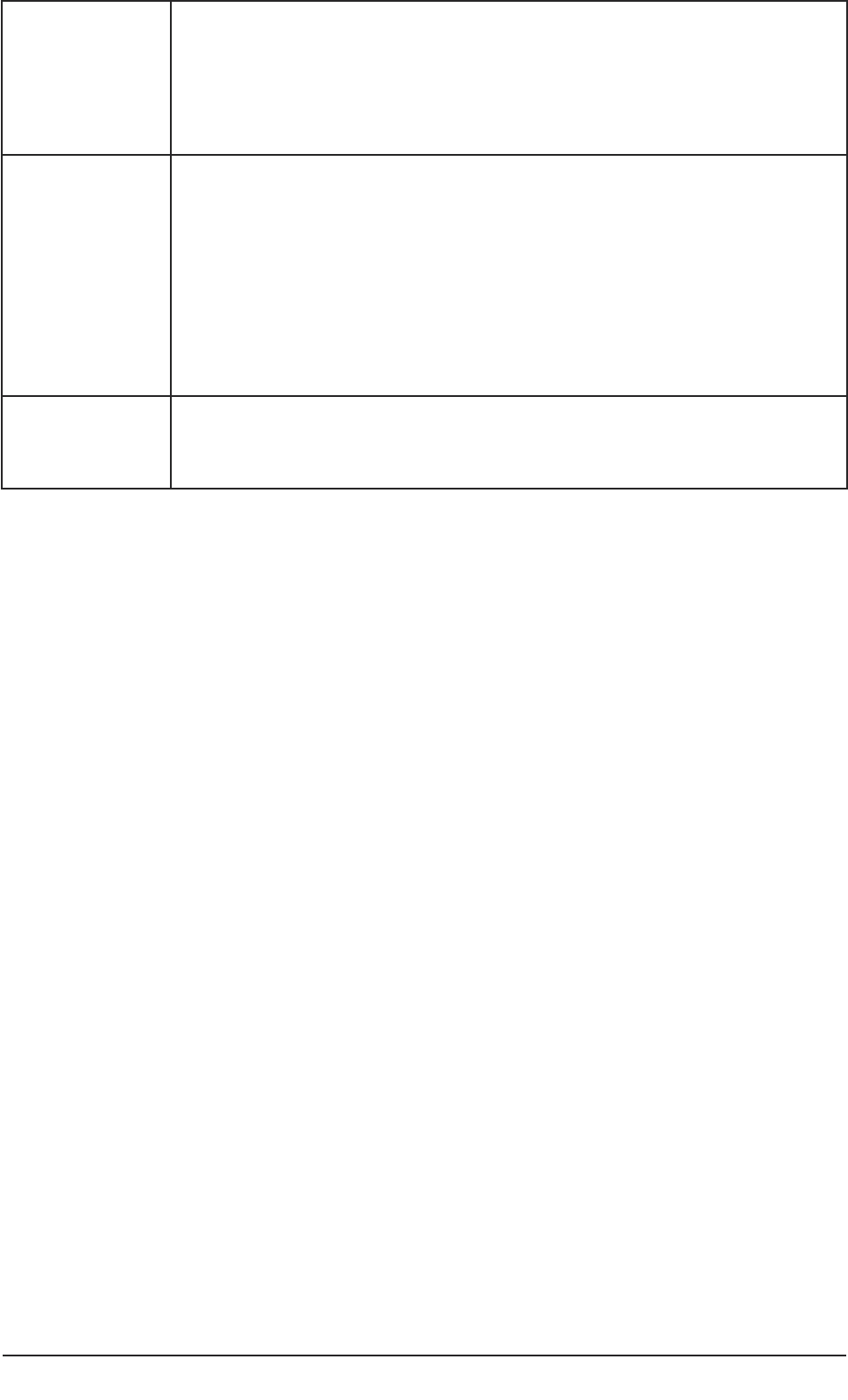

Personal Consultee Nominated Consultee

What is the

consultee’s

relationship

with the

(prospective)

participant)?

The Personal Consultee is someone the

person knows and trusts with important

decisions about their welfare and who

- is not paid to provide care to the

person;

- could be a family member, carer,

friend;

- could be an attorney or a deputy

appointed by the Court of

Protection.

The Nominated Consultee is someone

who

- may be known to the person;

- may be paid to provide care, such as

a member of staff in a care home in

which the person lives;

- may provide professional services,

such as a solicitor or a doctor;

- may not be known to the person;

- may act as a consultee for several

prospective participants.

How does the researcher decide who to

contact?

How does a

researcher

decide who to

contact?

See flow chart (Figure 4) See flow chart (Figure 4)

A practical guide for researchers 21

4.2 Role of Research Consultee

The Mental Capacity Act requires that a researcher take ‘reasonable steps’ to identify

others who could be consulted about a prospective participant’s involvement in research

(MCA para 32 (2)). The researcher is required to identify a person (someone who is

interested in that person’s welfare) who can be consulted about what the prospective

participant’s wishes and feelings about participation in the project would be if the person

had capacity. In circumstances where the prospective participant has little contact with

other than paid or professional carers, the researcher can nominate a person who can be

consulted providing they have no direct involvement with the project.

Guidance produced by the Department of Health and Welsh Assembly Government

creates roles for ‘personal’ and ‘nominated’ consultees as those consulted by the

researcher. Of particular importance the research consultee does NOT give consent on

behalf of a participant, but rather the researcher seeks advice from the consultee. The

researcher, not the consultee, makes the decision about whether to include the person as a

participant, though has to abide by information the consultee provides that suggests that

the person may object to inclusion in the project.

The following paragraphs provide further description of the roles and responsibilities of

consultees, suggest a process by which the researcher seeks advice from consultees and how

such advice can be made use of within the overall research process. The roles of personal

and nominated consultees in the research process are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Roles of personal and nominated consultees in the research process.

22 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

Who initiates

contact with a

consultee?

The clinical/care team, health or social

care agency contact the personal

consultee. Contact details are known to

the care/clinical team, health or social

care agency.

See sample letter in Part 2(4b).

The researcher contacts the Nominated

Consultee.

See sample letter in Part 2(5b) of this

guide.

What

information

does the

consultee

receive?

The researcher provides information

about the project and about the role of

a Personal Consultee.

See suggested information sheet in

Part 2 (4c).

The researcher provides information

about the project and about the role of

a Nominated Consultee.

See suggested information sheet in

Part 2 (5c).

What advice

does the

researcher seek

from the

Consultee?

Consultee’s general understanding of

the project.

Whether the participant may be

interested in taking part in the project

or whether they would object.

Whether the person may benefit in

any way by taking part.

Whether the person has previously

expressed views about involvement in

research, assuming they had such

capacity in the past.

Whether the person has made any

advance statements or has a written

advance decision for refusal of life-

sustaining treatment.

Whether participation would cause

any inconvenience or any other

difficulty for the person.

Whether the person would give any

signs, and if so, what these would be,

to indicate they were not happy

about continuing with the project.

Whether the consultee would wish to

be approached again for their views.

Whether the consultee could suggest

an alternative consultee.

Whether, from their understanding of

the person and the project, on

balance the person should or should

not take part.

Consultee’s general understanding of

the project.

Whether the consultee has any

personal or professional connections

with the project or an interest in its

outcome.

What knowledge of the person, and if

so, in what capacity.

Whether the consultee has discussed

involvement in the project with the

person.

Consultee’s views about whether the

participant may benefit from taking

part.

Consultee’s views about whether the

person may object, be upset in any

way or want to stop being involved,

and if so, how this would be shown.

Consultee’s views about whether

participation may cause any problems

or inconvenience.

Whether, from their understanding of

the person and the project, on

balance the person should or should

not take part.

A practical guide for researchers 23

yes

yes

yes

yes

yes

yes

no

no

no

no

no

no

Does the person have

capacity to consent?

Does the person have

family or friends?

Care/clinical team contacts

family or friends

Should the person be a

participant?

EXCLUDE

INCLUDE

Does the

person know

someone else?

Does the care

organisation

have a panel of

Nominated

Consultees?

Does the

research sponsor

have a panel of

Nominated

Consultees?

Key:

Questions for and action by researcher

Action by care/clinical team

Researcher discusses with

Principal/Chief Investigator

Researcher contacts

Consultee

Do family or friends

respond to invitation?

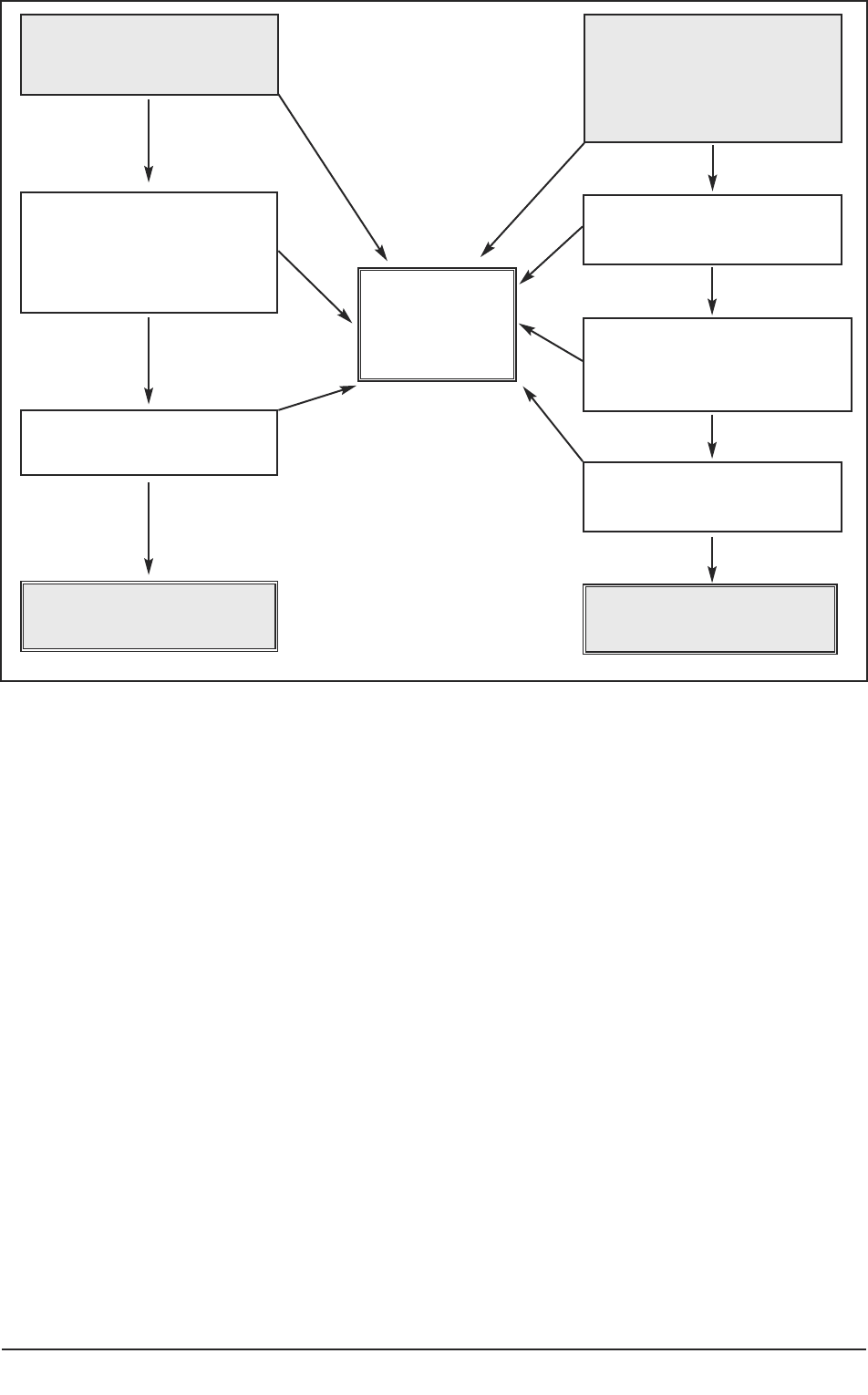

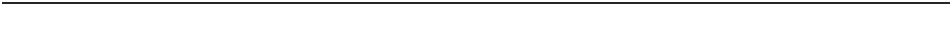

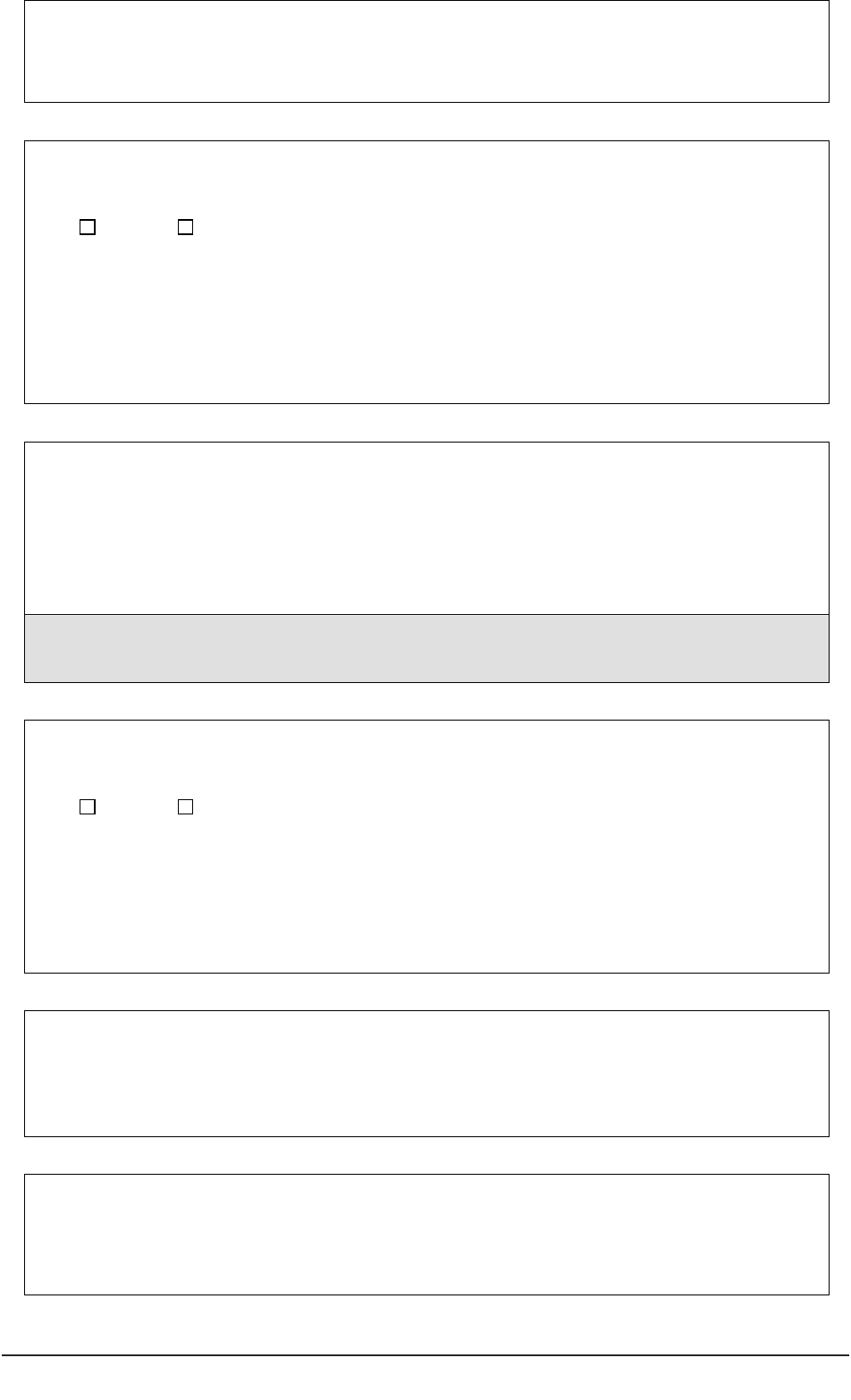

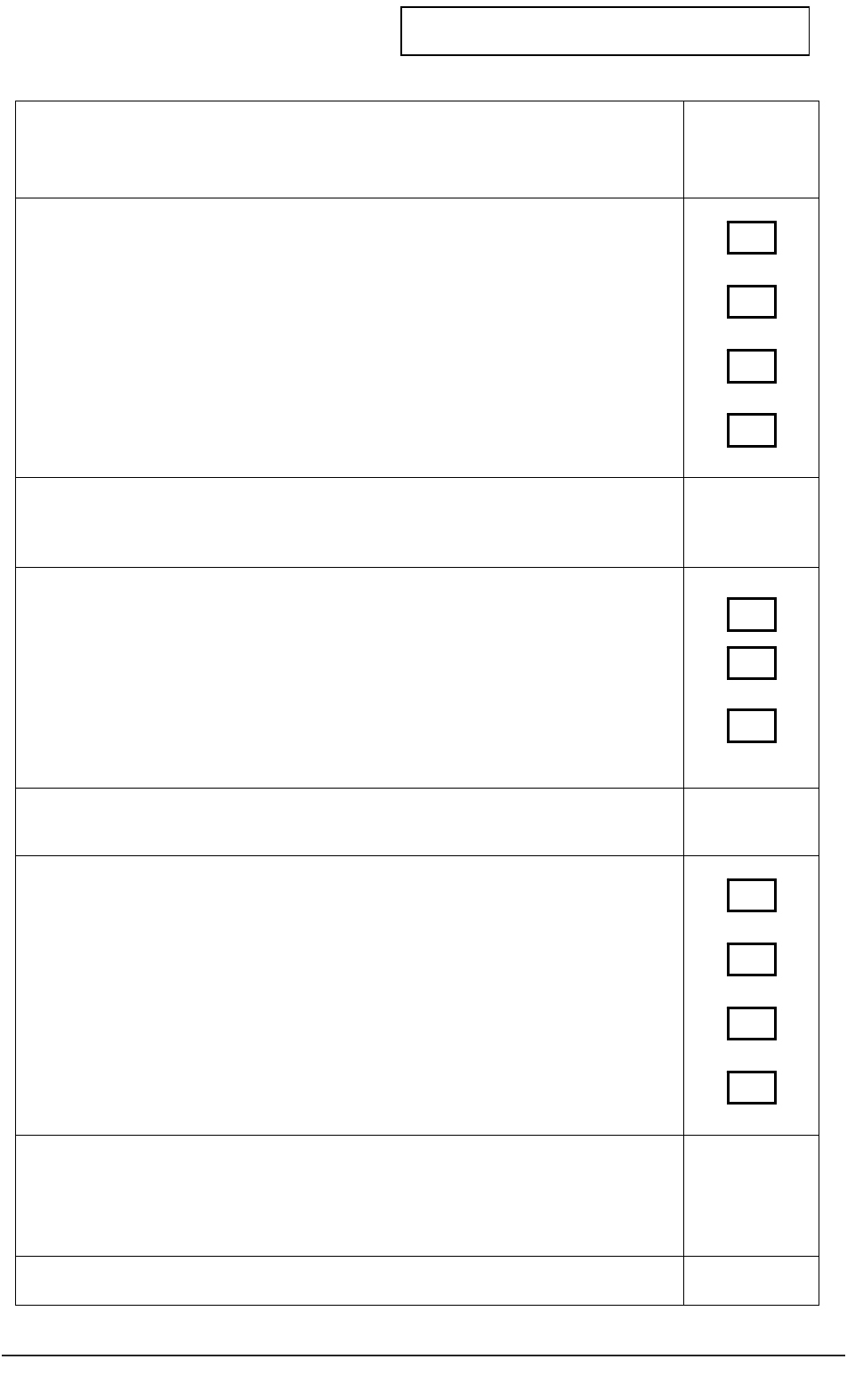

4.3 Consulting with a Research Consultee

The process of consultation starts with the clinical/care team contacting someone known

to the prospective participant and inviting them to be consulted about their relatives or

friend’s involvement in the project (see Figure 4). See Part 2 (4b) for a sample letter

together with preliminary information about the project. If the relative or friend accepts

the invitation to be a Personal Consultee, the Care/Clinical Team contacts the Personal

Consultee to make arrangements to discuss the project with the researcher. The researcher

needs to make clear that they are seeking the Personal Consultee’s views about whether or

not the prospective participant may wish to take part, not their own views about the

project. The views and opinion of the consultee will need to be documented by the

researcher for later reference. A suggested proforma is provided in Part 2 – Forms.

There is limited research about the extent to which family members are prepared to be

consulted. A study in Australia (Iacano & Murray, 2003) demonstrated that 50 per cent of

families who were approached declined to offer information about prospective participants.

The researcher may also need to approach the Personal Consultee at later stages in the

research process to confirm whether the participant would wish to continue with or to

decline taking part in the project.

Figure 4: Seeking advice from a consultee.

4.4 Personal Consultee

The Personal Consultee is someone who the (prospective) participant knows and whom

they trust with important decisions about their welfare. The Personal Consultee could be a

relative, a friend or someone having a Lasting Power of Attorney for personal welfare

(including healthcare and consent to medical treatment) or a deputy appointed by the

Court of Protection. The Personal Consultee could NOT be someone who is a paid carer

or who has a professional relationship with the prospective participant.

The researcher seeks an opinion from the Personal Consultee about

■ whether the person should take part in the research;

■ what the person’s wishes and feelings would be about such a project;

■ whether it is likely that the person would decline to take part, had they the capacity

to decide.

If the consultee advises the researcher that the person would not wish to take part, then

the person should be withdrawn from the project

Given that Section 32(2) of the Mental Capacity Act (2005) suggests that ‘reasonable steps’

should be taken to identify a Personal Consultee and has also proposed the appointment of

Nominated Consultees, the researcher appears to have a choice about who to approach. A

flowchart (Figure 4) is offered as a means of assisting the researcher in deciding whether to

seek consultation from a Personal or a Nominated Consultee.

4.5 Nominated Consultee

A Nominated Consultee may be a paid carer or someone who has a professional

relationship with the person, such as a solicitor or a doctor, but who has no financial or

other interest in the outcome of the project.

Guidance prepared by the Department of Health and the Welsh Assembly Government

(2008) suggests that Nominated Consultees could be drawn from a list of potential

Consultees, convened by a research active care organisation, such as a NHS Trust, research

sponsors, such as the Wellcome Foundation, or universities. Research networks which have

evolved as part of the NHS Research Strategy, Best Research for Best Health, may also

provide a convenient host for panels of Research Consultees. Alternatively, Independent

Mental Capacity Advocates may be in a position to contribute to consultation about the

involvement of participants in research, depending on local arrangements.

During the course of discussions for the preparation of this guide, a number of

respondents expressed concern about inviting an opinion from consultees who were not

known to the prospective participant.

Suggestions for good practice therefore are that a consultee adopts an approach similar to

that of an advocate, in which the consultee meets the prospective participant, carers,

relatives and friends (if available) in order to gain relevant information on which to base

advice to the researcher.

24 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

Section 5: Appraising partipant involvement

5.1 Appraising whether to include or exclude a participant

Section 31 of MCA states that the researcher must ensure that the project meets the

following five requirements.

1. The research project is associated with the condition which impairs the participant

and/or any treatment of the condition. An ‘impairing condition’ is one which

causes or contributes to any disturbance of the mind or brain (and on which the

assessment of lack of capacity is based).

2. The research project could not be undertaken as effectively solely with participants

who have capacity to consent.

3. The research must be intended to provide knowledge of the causes, treatment or

care of people affected by the same or similar impairing condition or that it

concerns treatment or care of the condition.

The MCA Code of Practice provides further examples of ‘similar’ conditions or

impairments that may not have the same cause, such as cognitive impairment

associated with brain injury acquired in adulthood and intellectual impairment

consequential to a genetic disorder.

4. The participant is likely to benefit from undertaking the research and that the

benefit is not disproportionate to any burden in taking part.

5. If there are no benefits to the person and if the research concerns the gaining of

knowledge about the condition, then there should be negligible risk to the

participant. In addition, participation in the project should not interfere with the

participant’s freedom of action or privacy in a significant way, or be unduly invasive

or restrictive.

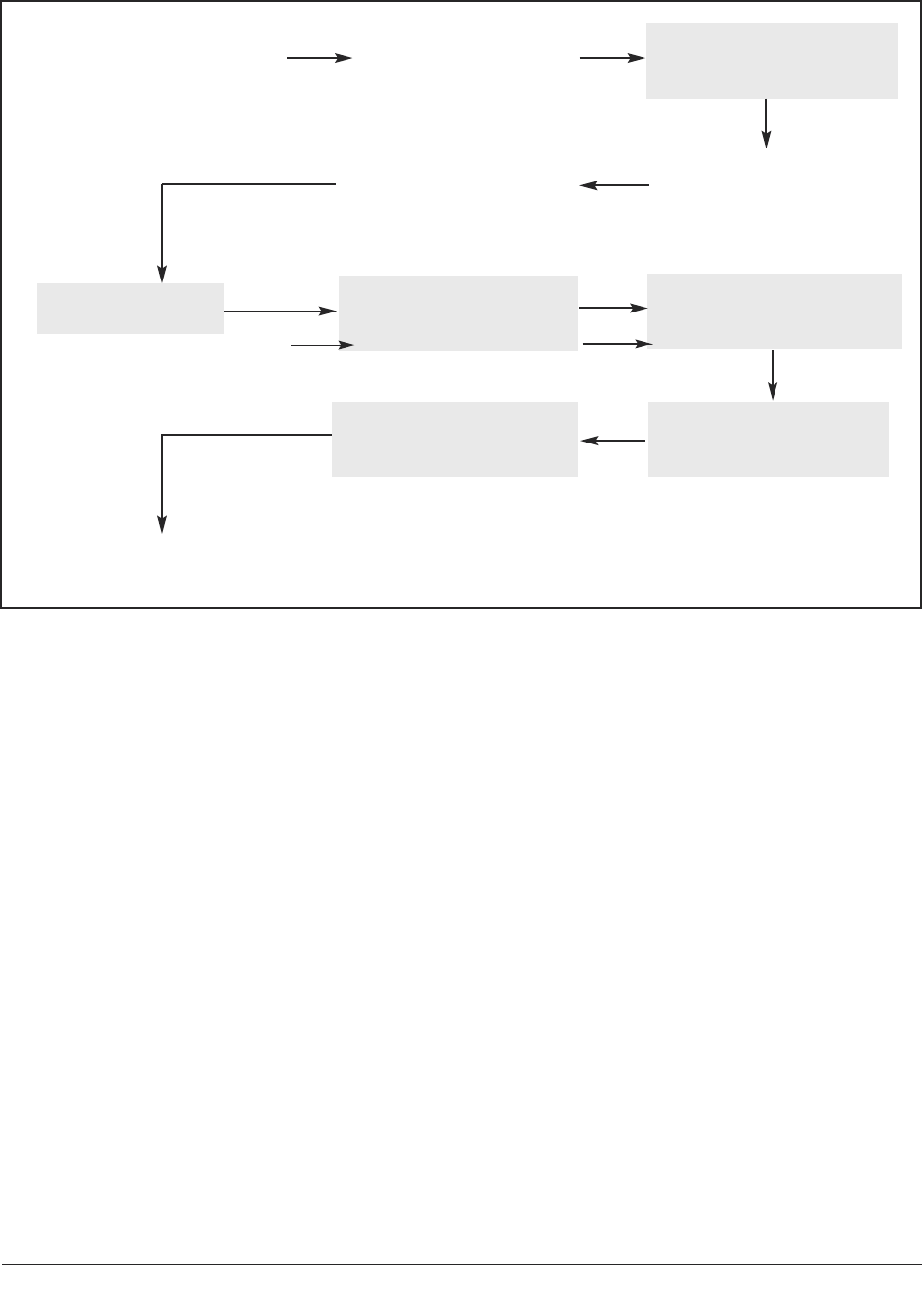

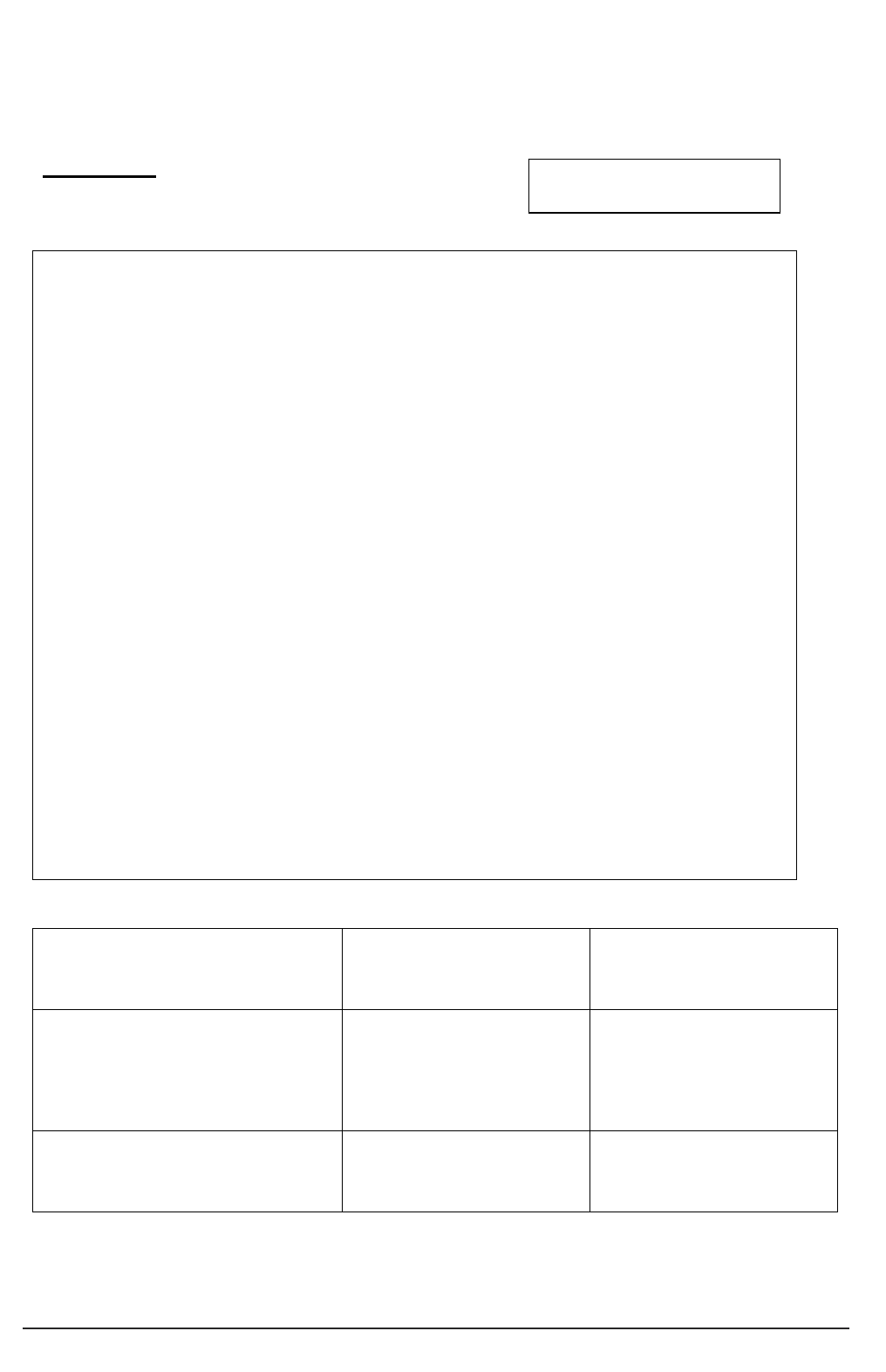

Figure 5 provides a diagrammatic representation of the decisions or judgments the

researcher needs to make. Requirements 1–4 above can be debated in principle in the

study protocol and in the application for ethical approval (shaded boxes). The fifth

requires information about the impact of involvement in the project for the individual

participant, information which could only be obtained in the course of consultation with

others.

A practical guide for researchers 25

Figure 5: Appraising an individual’s involvement in a project.

Figure 5 summarises questions the researcher needs to consider. A checklist for researchers

is available in Part 2(6) of the practice guide.

5.2 Reviewing continuing participation in a project

A key feature of consent to participate is the freedom to continue or to withdraw from a

study. Participants having significant cognitive impairment (language, memory and

problem-solving abilities) may be susceptible to influence as a result of pressure from

researcher or carer or by merely being in the ‘research environment’ (Gudjonsson, 2002).

Researchers may need to become aware of potential behaviour, both verbal and non-verbal

which indicates that the person may wish to withdraw (MCA, Section 33(4) and Code of

Practice 11.31). Examples may be that in addition to a clear expression of no longer

wishing to participate, the person pushes the equipment away or takes themselves away

from the researcher. In research based on observational methods, identifying behaviour

that is non-consenting to research may be difficult to distinguish from other behaviour or

activities being observed. Such matters would also have been addressed in the application

for ethical approval.

26 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

Is there negligible risk

to the participant?

Can research be undertaken

as effectively with

participants having

capacity to consent?

Is the research about

knowledge of causes,

treatment or care of persons

with an impairing condition?

Is the research about

treatment or care of an

impairing condition?

INCLUDE the person

EXCLUDE

the person

INCLUDE the person

Do benefits of participation

outweigh burden?

Does doing the research affect

the participant’s freedom of

action or privacy?

Is the research unduly

invasive or restrictive?

yes

no

no

yes

yes

yes

no

no

yes

yes

no

no

no

yes

If in doubt, the researcher may need to seek additional advice from a Personal or

Nominated Consultee. If the consultee advises that the person should be withdrawn, then

this must be respected by the researcher (MCA, Section 32 (5)). The researcher may find it

helpful to refer to Figure 5 (Appraising an individual’s involvement with a project)

together with checklist 6 in Part 2 of the Guide

Finally, if any of the requirements of the Act are no longer met, the individual must be

withdrawn from the project (Code of Practice, 11.31).

5.3 Recommendations for good practice

1. The researcher appraises the project in relation to each individual participant

lacking consent, even though these matters would have been anticipated in

principle during the process of gaining ethical approval. The benefits, burdens

and risks cannot be assumed to be similar for all participants.

2. Relevant evidence and decisions are documented.

3. The appraisal or re-appraisal of a participant’s involvement with the project is

conducted by means of a discussion between the researcher (who has collected

information from a consultee) and the Principal or Chief Investigator. A major

responsibility of the Principal or Chief Investigator is the overall welfare of

participants. Documentation recording aspects of the discussion is included in

Part 2(6) of the guide.

A practical guide for researchers 27

Section 6: Case studies

Case study 1 demonstrates how a researcher could undertake an assessment of capacity

and an appraisal of the involvement of an individual in a study.

Questions below offer the researchers a step-by-step examination of Susan’s capacity to

consent and consideration of whether she should be included in the study. See Figures 3,

4 and 5 and checklists provided in Part 2. (Additional material is provided for purposes of

illustration).

Q: Can Susan consent to her participation in research?

If yes – Susan can decide whether or not to participate.

If no or unsure – the researcher needs to assess Susan’s capacity to consent.

Whether Susan indicates her willingness to participate is a separate matter from

her capacity to consent to participation.

Q: Does Susan have a condition impairing her ability to make decisions?

A: A Susan suffers from psychosis which impairs her capability in making decisions,

including about participating in the research study.

28 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

Susan, aged 25, married with two children, has been experiencing some mental health

problems since the age of 16. She has been experiencing low mood, anxiety and low

levels of paranoia but has been able to cope with her problems to date. She has been

treated by her GP who has prescribed anxiolytics and anti-depressants and at times she

has also been receiving input from the Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) in the

area. Susan’s marriage recently broke down and her ex-husband has been making threats

to take the children away from her because of her mental health condition. Her mother

died when she was still very young, her father is an alcoholic, and she has no brothers and

sisters. Her friends have rejected her due to her mental health problems and Susan has

no one to talk to and feels isolated.

As a result of these experiences her mental health problems have now become

unmanageable and Susan has experienced a mental breakdown. She is now on a female

ward and her ability to reason and make judgements is significantly impaired. After a

detailed assessment of her symptoms by the psychiatrist Susan is diagnosed with a first

episode of psychosis. Susan fulfils the necessary criteria to participate in your first episode

study. The study involves participation in lengthy questionnaires that could take up to

three hours to complete some of which need to be videotaped.

Would Susan participate in the research study?

Q: Does Susan have the capacity to consent to participation in the ‘first episode’

study?

A: The researcher determines whether Susan

■ can retain information about the study;

■ understand the intentions of the project;

■ weigh up information about the project and the consequences of

participating or not;

■ convey her response.

Susan can describe some aspects of what the project is about. She understands she

has to answer some questions. Susan cannot describe how taking part or not taking

part would affect her.

The researcher kept notes of the discussion with Susan.

In discussion with the Principal Researcher, the Principal Researcher considered

that Susan did not have the capacity to consent to her involvement with the

research project at the time consent was sought, as she was not able to weigh up

information about the project or the consequences of her involvement. Susan was

unlikely to regain capacity in relation to making decisions about her involvement

with the current project.

A: Susan suffers from psychosis which may impair her capability in making decisions.

The researcher determines whether she can retain and understand the intentions

of the project, weigh up that information and the consequences of participating or

otherwise and convey her response.

If still no – then Susan does not have the capacity to consent

Whether Susan states her willingness to participate is a separate matter from her

capacity to consent.

Q Who can the researcher consult with?

A Susan is described as being isolated from family and friends. Her children are

under the age of 18, so no family member may be appropriate to act as a Personal

Consultees.

Susan is known to members of the Community Mental Health Team; hence the

researcher could contact the team to identify someone who would be willing to act

as a Nominated Consultee, providing the team did not have an interest in the

outcome of the project. If team members were connected in any way with the

project, the researcher would need to contact a different Nominated Consultee

who was independent of the project.

A practical guide for researchers 29

Q Is the research about treatment or care or about knowledge of a condition, care or

treatment?

A The study appears to be about knowledge of psychosis or its treatment or care.

Q Does Susan have an advance statement?

A The Nominated Consultee has advised that Susan has not prepared an advance

statement.

Q Would participation in the study

a) Be of negligible risk to Susan?

A The researcher uses information gained from the Nominated Consultee about

whether the interviews would potentially be of harm to Susan, perhaps, for

example, because of the nature of the interview questions.

b) Affect Susan’s freedom of action or privacy?

A The interviews could be conducted in a private room; however, the Nominated

Consultee advised that Susan participates in therapy sessions which would clash

with the intended timing of the interviews with the researcher.

c) Be unduly invasive or restrictive?

A The interviews require in-depth discussions about Susan’s family life. The

Nominated Consultee has advised that Susan has difficulty in talking about her

family life.

A conclusion could be reached that Susan may experience distress in participating in the

research interview – hence she should not be included as a participant. Of particular

importance is the key distinction between ‘research of the treatment’ and research which is

knowledge about the condition, treatment or care of persons’; if the latter, the research

may not necessarily be of benefit to the person, but would still need to meet the criterion

of ‘interests of the person outweighing those of science and society’.

Consideration of whether research is unduly invasive or restrictive may also be different for

different people. The MCA Code of Practice suggests that ‘unduly invasive’ research is that

which does not go beyond ‘the experience of daily life. Routine medical examination or

psychological assessment is considered as not being ‘unduly invasive’ (MRC, Code of

Practice, 11.19).

30 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

Case study 2

Case study 2 is an appraisal of the overall ethical stance of a project rather than that of the

involvement of individual participants.

In this case study, published in the Medical Research Council Ethics Guide (2007), the

Blandfordshire REC decided that the health hazard (harm) to participants was equivalent

to ‘risk’ encountered in normal daily life and approved the study. The case study also

demonstrates an approach to consultation with others which appraises the participants as a

group rather than as individuals.

A practical guide for researchers 31

The Blandfordshire REC was asked to review a proposal to study whether electronic

tagging was beneficial to the care of older people with varying degrees of dementia who

lived in residential homes. The hypothesis was that the tagging would allow the residents

more freedom while minimising their risk of getting lost. There was some discussion

about whether the tagging was an invasion of privacy when the individuals concerned

were unable to provide informed consent. However, the results of an independent

consultation, commissioned by the researchers, of relatives and carers suggested that the

benefits to the residents were perceived to outweigh this concern. The tagging device was

very small and not noticeable when worn. When the project was reviewed by the REC, it

was questioned whether the radio frequencies used constituted a health hazard in this

age group. A decision on whether the study might go ahead was deferred until the

researchers provided an updated analysis of the literature on this issue, in light of new

scientific evidence. This analysis suggested that the radio frequency risk was similar to

that of mobile telephones.

Section 7: Concluding comments

The Mental Capacity Act (2005) has opened up the possibilities that people not able to

consent should no longer be excluded from participation in research, enabling access to

experiences and potential treatments and care for which they may not hitherto have been

considered. The MCA has sought to balance such access with safeguards applying at

different stages of the research process.

Preparation of the practice guide has brought into focus a number of ethical,

philosophical and political matters, such as the nature of ‘informed consent’, the range of

decisions a researcher may need to take at different stages of the research process and

stark differences between conducting research in ‘health’ rather than in ‘social care’

settings.

The practice guide was originally envisaged as a compendium of resources, references and

‘good ideas’ for conducting research with people not having the capacity to consent to

their participation, prepared from the perspective of different parties in the research

process. After much deliberation, the author considered that taking a systemic view of the

research process would provide a meaningful structure for materials that a researcher may

find useful.

The extent to which researchers find the materials of assistance will depend on whether

researchers, sponsors and funders consider the additional safeguards feasible to

incorporate within research projects, given tight timescales and restricted budgets. An

audit of the use of the guidance materials, together with a review of experience in Scotland

and other jurisdictions, may in the future help to identify the kinds of research questions

which could not be addressed by other means.

32 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

Appendices

Appendix 1 References

Appendix 2 NHS Research Ethics Committees which have been

‘flagged’ to scrutinise projects involving

participants who do not have the capacity to

consent

Appendix 3 Roles and responsibilities in the research process

Appendix 4 Additional questions and ethical implications

Appendix 5 Contributors

A practical guide for researchers 33

Appendix 1

References

Article 17 of the Protocol to the Convention on Human Rights in Biomedicine or

Biomedical Research (2005).

British Psychological Society (2004a). Guidance for the minimum standards of ethical approval

for psychological research. Leicester: Author

British Psychological Society (2004b). Code of conduct, ethical principles and guidelines.

Leicester: Author.

British Psychological Society (2005). Good practice guidelines for the conduct of psychological

research in the NHS. Leicester: Author.

British Psychological Society (2008) Generic Professional Practice Guidelines (2nd edn.)

Leicester: Author.

Cameron, L. & Murphy, J. (2006). Obtaining consent to participate in research: The issues

involved in including people with a range of learning and communication disabilities.

British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35, 113–120.

British Psychological Society (2007). Report of the working party on conducting research on the

internet: Guidelines for ethical practice in psychological research online. Leicester: Author.

Department for Constitutional Affairs (2006). The Mental Capacity Act (2005): Draft Code of

Practice. London. The Stationery Office

Department for Constitutional Affairs (2007). The Mental Capacity Act (2005): Code of

Practice. London. The Stationery Office.

Department of Health (2004a). Information about patients: An introduction to the Patient

Advisory Group for health professionals and researchers. Retrieved from

http://www.advisorybodies.doh.gov.uk/piag/InformationAboutPatients.pdf.

Department of Health (2004b). The research governance framework for health and social care –

Implementation plan for social care. London: Department of Health.

Department of Health (2005). Research governance framework for health and social care.

London: Department of Health. Retrieved 25 November 2008 from

http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/ Publicationsandstatistics/ Publications/

PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4122427.

Department of Health (2006). Consultation on regulations made under the Mental

Capacity Act (2005). Retrieved on 27 November 2008 from http://www.dh.gov.uk/

en/ Consultations/Closedconsultations/DH_4138699.

Department of Health and Welsh Assembly Government (2008). The Mental Capacity Act

and consent for research: What research does the Act cover? . Retrieved on 27 November

2008 from http://new.wales.gov.uk/dhss/publications/health/mentalhealth/

mentalcapacityact/2117019/mcaconsente.pdf?lang=en.

34 Conducting research with people without the capacity to consent

Department of Health and Welsh Assembly Government (2008). Guidance on nominating a

consultee for research involving adults who lack capacity to consent. London: Department of

Health.

Doyle, L. (2005). The ethical governance and regulation of student projects: A proposal. Retrieved

on 25 November 2008 from http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Researchanddevelopment/

A-Z/Researchgovernance/ index.htm/DH_4120898.

Gudjonsson, G. (2002). The psychology of interrogations and confessions: A handbook. London:

Wiley.

Herring, J. (2006). Medical law and ethics. OUP

Iacano, T. & Murray, V. (2003). Issues of informed consent in conducting medical research

involving persons with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual

Disabilities,16, 41–51.

Medical Research Council (2007). MRC ethics guide 2007: Medical research involving adults

who cannot consent. London: Author. Retrieved from http://www.mrc.ac.uk/Utilities/

Documentrecord?index.htm?d=MRC004446.

The Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004. London: The Stationery

Office.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Loss of Capacity during Research Project) (England)

Regulations 2007.

Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Appropriate Body) (England) Regulations 2006. London: The

Stationery Office.

Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Appropriate Body) (Wales) Regulations 2006. London: The

Stationery Office.

Mental Capacity Act (2005) Chapter 9. London: Office of Public Sector Information.

National Research Ethics Service (2007). Information sheets and consent forms for

researchers and reviewers, v.3.2 May 2007. Retrieved on 25 November 2008 from

http://www.nres.npsa.nhs.uk/rec-community/Guidance/#PIS.

National Research Ethics Service (2007) Research involving adults unable to consent for

themselves v 2 September 2007. Retrieved on 27.11.08 from

http://www.nres.npsa.nhs.uk/rec-community/guidance/#consent.

Statutory Instrument 2002 No. 1438 The Health Service (Control of Patient Information)

Regulations 2002.

US Department of Health and Human Service. (2004). Research involving human subjects:

Research Regulations and ethical guidelines. Quoting from Trials of War Criminals