Lean Six Sigma for the

Healthcare Practice

A Pocket Guide

Also available from ASQ Quality Press:

The Certified Six Sigma Green Belt Handbook

Roderick A. Munro, Matthew J. Maio, Mohamed B. Nawaz, Govindarajan

Ramu, and Daniel J. Zrymiak

Six Sigma for the Office: A Pocket Guide

Roderick A. Munro

Six Sigma for the Shop Floor: A Pocket Guide

Roderick A. Munro

Automotive Internal Auditor Pocket Guide: Process Auditing to

ISO/TS 16949:2002

Roderick A. Munro

The Certified Six Sigma Black Belt Handbook, Second Edition

T. M. Kubiak and Donald W. Benbow

Applied Statistics for the Six Sigma Green Belt

Bhisham C. Gupta and H. Fred Walker

Statistical Quality Control for the Six Sigma Green Belt

Bhisham C. Gupta and H. Fred Walker

5S for Service Organizations and Offices: A Lean Look at Improvements

Debashis Sarkar

The Executive Guide to Understanding and Implementing Lean Six

Sigma: The Financial Impact

Robert M. Meisel, Steven J. Babb, Steven F. Marsh, and James

P. Schlichting

Transactional Six Sigma for Green Belts: Maximizing Service and

Manufacturing Processes

Samuel E. Windsor

Defining and Analyzing a Business Process: A Six Sigma Pocket Guide

Jeffrey N. Lowenthal

The Certified Manager of Quality/Organizational Excellence Handbook,

Third Edition

Russell T. Westcott, editor

To request a complimentary catalog of ASQ Quality Press publications,

call 800-248-1946, or visit our Web site at http://qualitypress.asq.org.

Lean Six Sigma for the

Healthcare Practice

A Pocket Guide

Roderick A. Munro, PhD

ASQ Quality Press

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

American Society for Quality, Quality Press, Milwaukee 53203

© 2009 by ASQ

All rights reserved. Published 2009

Printed in the United States of America

15 14 13 12 11 10 09 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Munro, Roderick A.

Lean Six Sigma for the healthcare practice : a pocket guide / Roderick A. Munro.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87389-760-0 (soft cover, spiral bound : alk. paper)

1. Six sigma (Quality control standard) —Handbooks, manuals, etc.

2. Medical care—Quality control—United States—Statistical methods—

Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Health Services Administration—Handbooks. 2. Quality

Assurance, Health Care—Handbooks. 3. Efficiency, Organizational—

Handbooks. W 49 M968L 2009]

RA399.A3M66 2009

362.1068—dc22 2009000930

ISBN: 978-0-87389-760-0

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Publisher: William A. Tony

Acquisitions Editor: Matt T. Meinholz

Project Editor: Paul O’Mara

Production Administrator: Randall Benson

ASQ Mission: The American Society for Quality advances individual,

organizational, and community excellence worldwide through learning, quality

improvement, and knowledge exchange.

Attention Bookstores, Wholesalers, Schools, and Corporations: ASQ Quality

Press books, videotapes, audiotapes, and software are available at quantity

discounts with bulk purchases for business, educational, or instructional use.

For information, please contact ASQ Quality Press at 800-248-1946, or write to

ASQ Quality Press, P.O. Box 3005, Milwaukee, WI 53201-3005.

To place orders or to request a free copy of the ASQ Quality Press Publications

Catalog, including ASQ membership information, call 800-248-1946. Visit our

Web site at www.asq.org or http://www.asq.org/quality-press.

Printed in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

This book is dedicated to the Quality

Improvement Coaches (QICs) and Primary

Care Providers (PCPs) in Michigan

who have embarked on the Improving

Performance in Practice (IPIP) process.

The State of Michigan has combined the

reporting requirements of the Patient-

Centered Medical Home and the national

IPIP into one reporting process to

reduce redundancy and to focus more on

improvements in healthcare quality.

Most especially to the many overloaded,

stressed-out healthcare professionals who

may feel that they can not take on one more

task or new patient. The methodologies and

tools found in this book will help you.

(This page intentionally left blank)

vii

Contents

Acronym List ............................. xi

Preface.................................. xiii

Acknowledgments ........................ xv

Suggested Use of This Book................. xix

The DMAIC Matrix Guide................... 1

What Is Lean Six Sigma? ................... 5

Your Role in Lean Six Sigma ................ 11

What Is Variation? ........................ 17

Things You Might Be Involved With.......... 25

The DMAIC Model ........................ 29

Teams ................................... 41

The Lean Six Sigma Road Map for

the Practice ........................... 47

Summary ................................ 49

Tools.................................... 53

7S ................................... 53

Advanced Practice Quality Planning

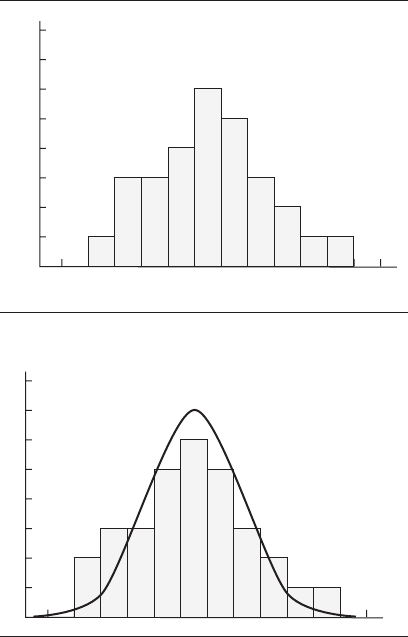

(Healthcare APQP)................... 58

Auditing (Sampling, Sampling Plans) ...... 62

Benchmarking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

Brainstorming ......................... 71

Business Operating System (BOS) for

Healthcare Organizations ............. 76

Cause-and-Effect Diagram (Fishbone

Diagram, Ishikawa Diagram) .......... 79

Check Sheets .......................... 84

Continual Improvement (Kaizen,

Kaizen Events) ...................... 89

Cost–Benefit Analysis (Cost of Quality,

Quality Cost, Cost of Poor Quality,

Return on Investment) ............... 93

Cycle Time Analysis ..................... 98

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis......... 101

Flowchart (Flow Map, Process Map,

Current State/Could Be/Should

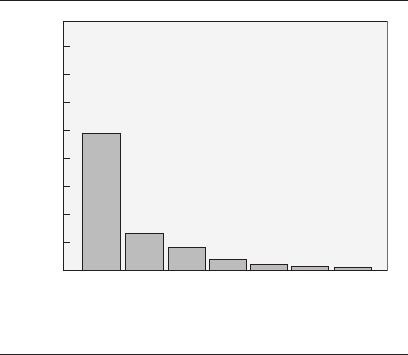

Be Map)............................ 113

Histogram ............................ 118

Kanban (Wait Time, Patient Pull-

Through)........................... 122

Lessons Learned ....................... 124

Management Involvement ............... 126

Measurement Systems Analysis (MSA) ..... 129

Mistake-Proofing (Error-Proofing,

Poka-Yoke) ......................... 133

Pareto Chart........................... 136

PDSA Cycle (Plan–Do–Study–Act) ......... 141

Practice Strategy (Future State) Project

Planning ........................... 145

Problem Solving ....................... 148

viii Table of Contents

Table of Contents ix

Process Behavior Charts (Statistical

Process Control) ..................... 152

Process Identification ................... 158

Process Improvement (PI) ................ 160

Run Chart ............................. 163

Scatter Diagram........................ 166

SIPOC Diagram......................... 170

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) .... 173

Standardization (SDCA—Standardize–

Do–Check–Adjust) ................... 175

Systems Thinking....................... 177

Team Meetings (Huddles) ............... 181

Teams (Employee Involvement,

Improvement, Self-Directed) .......... 185

Value Analysis ......................... 192

Value Stream Map (VSM) ................ 195

Variation Reduction .................... 199

Visual Controls, Aids .................... 202

Voice of the Customer (Patient

Feedback) .......................... 204

Walkaround/Walkthrough/Waste Walk .... 207

References............................... 211

Index ................................... 217

(This page intentionally left blank)

xi

Acronym List

7S—sort, set-in-order, shine, standardize,

sustain, safety, oversight

8D—eight disciplines to problem solving

APQP—healthcare advanced practice quality

planning

BOS—business operating system

C&E —cause-and-effect diagram

CI—continual improvement

COPQ—cost of poor quality

COQ—cost of quality

CPHQ—Certified Professional in Healthcare

Quality

CQIA—Certified Quality Improvement

Associate

DMAIC—define, measure, analyze, improve,

control

FMEA—failure mode and effects analysis

xii Acronym List

IPIP—improving performance in practice

IPO—input, process, output

ISO—International Organization for

Standardization

LCL—lower control limit (see “Process

Behavior Chart”)

M P CC—Michigan Primary Care Consortium

MSA—measurement systems analysis

PCMH—patient-centered medical home

PCP—Primary Care Provider

PDCA—plan–do–check–act

PDS A—plan–do–study–act

PI—process improvement

QIC—Quality Improvement Coach

ROI—return on investment

RPN—risk priority number (see “FMEA”)

SDCA—standardize–do–check–adjust

SIP OC—supplier, input, process, output,

customer

SOP—standard operating procedure

SPC—statistical process control

UCL—upper control limit (see “Process

Behavior Chart”)

VSM—value stream map

xiii

T

his book is a continuation of a series of

works started by the author, referred to as

QUIT—“Quality in Training.” It is hoped

that through this ongoing series people will be

helped in finding joy in the work that they do,

leading to healthier, happier lives.

A Zen Buddhist text on The Art of Living

states:

The Master in the art of living makes little

distinction between his work and his play,

his labor and his leisure, his mind and his

body, his education and his recreation,

his love and his religion. He hardly knows

which is which. He simply pursues his vision

of excellence in whatever he does, leaving

others to decide whether he is working or

playing. To him he is always doing both.

It will be left to the reader to decide at what point

the author is/was doing each in this text.

Preface

xiv Preface

We are discussing the concept of healthcare

quality sometimes called “quality of care and

services.” In this book, our focus is on how well

the organization performs the many activities

and functions involved in patient care. The term

“quality of care and services” is not limited to the

technical quality of care provided to patients;

“quality of care and services” is a broader, more

general category that includes not only the tech-

nical quality of care, but also includes how well

patient service needs are met.

If you would like to make comments to

the author about this book, please contact him at

authors@asq.org.

xv

A

s in any work, a lot of people were

involved in developing this book. I would

like to thank all the class participants,

suppliers, and peers that I have worked with in

the past 30 years. I continue to learn from all

your input.

I especially would like to thank Dr. Dean H.

Stamatis and Dr. Elizabeth J. Rice for their years

of friendship and their encouragement and sup-

port of this work.

Thanks also go to the staff at ASQ Quality

Press and the reviewers for their time, efforts,

and support in making this book a reality. Thanks

especially to Paul O’Mara and Matt Meinholz for

their ongoing support of this series.

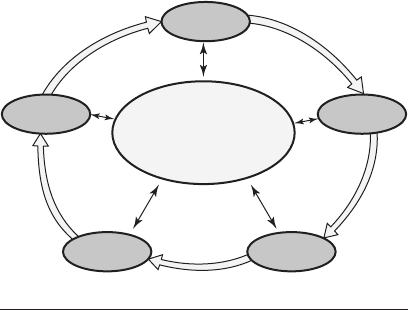

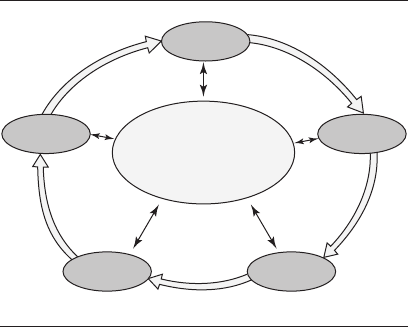

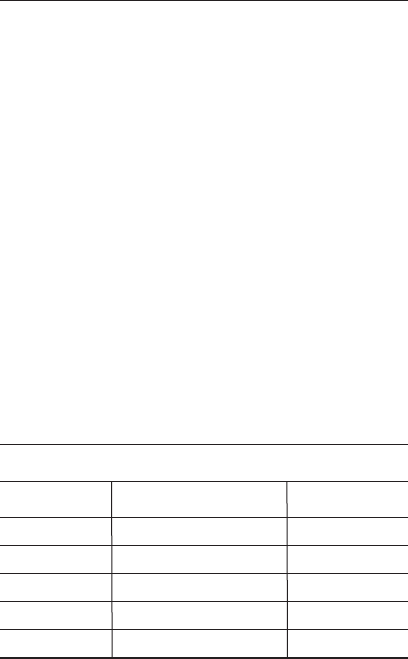

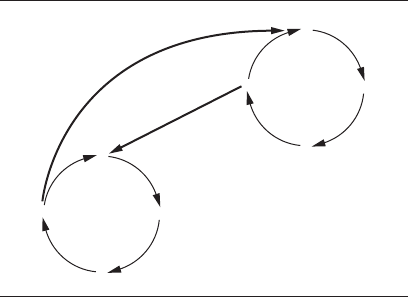

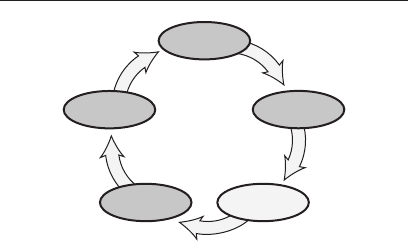

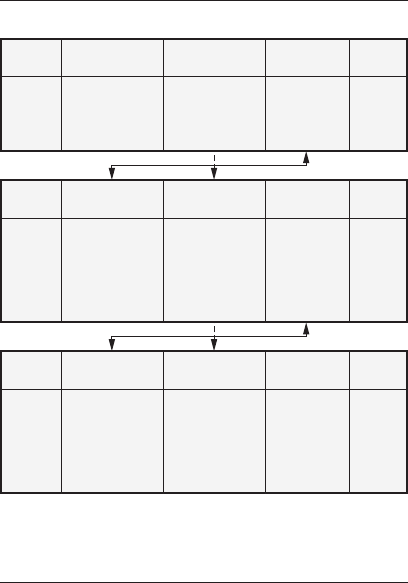

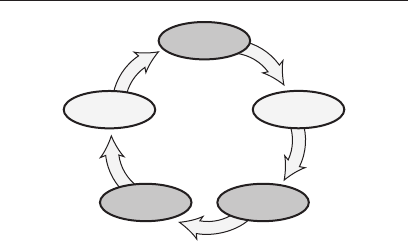

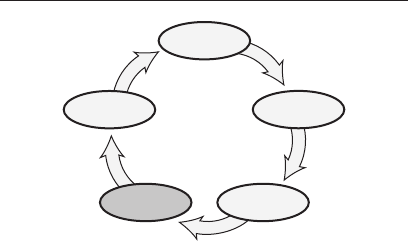

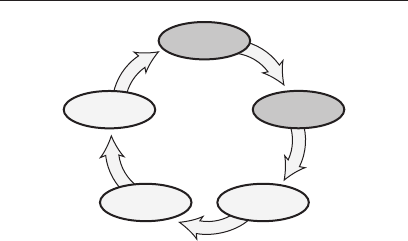

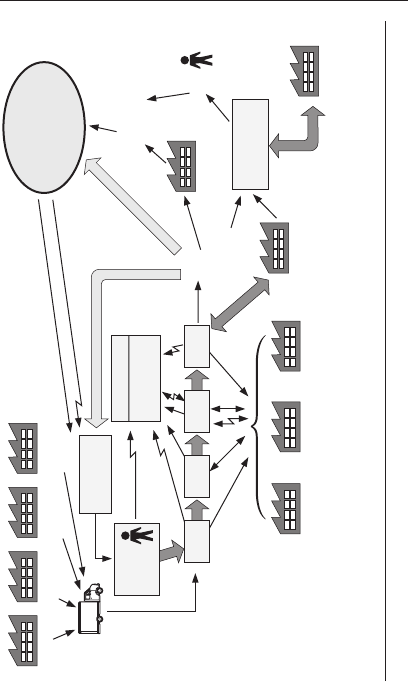

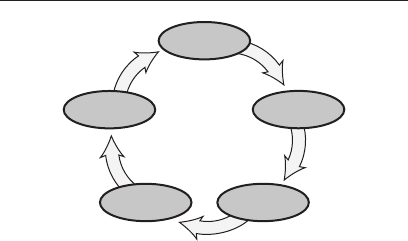

Special thanks goes to the Michigan IPIP team

of professionals. The Healthcare Improvement

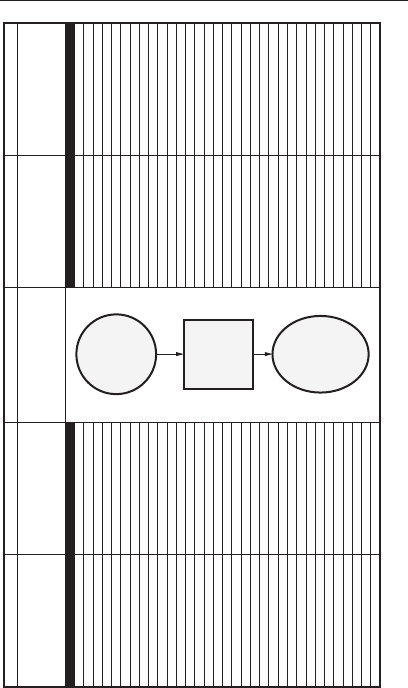

Model on page xvi is a summary of some of the

early work that has been accomplished in assist-

ing Practices toward healthcare improvements.

Acknowledgments

xvi Acknowledgments

SA

DC

PA

DS/C

Health system

professionals

Community

Facilitate the project

using best processes

“Lean” the practice

Solve problems/

breakthrough improvement

Quality and lean

professionals

Informed,

activated

patients

Project

management

Needs

assessment

Team building

7 wastes

Kaizen

Value stream

Current state

Future state

DMAIC

Process mapping

5 whys Root cause analysis

Measurement systems

FMEA

Visual controls

7S

Waste walk

Value analysis

Error-proofing

Pull systems

Quick changeover

Standardized work

Set up controls

Kanban

Scoping

Cost of poor quality

Scheduling

Brainstorming

ROI

Training

Leadership

Productive

interactions

Improved outcomes

Patient-Centered

Medical Home

Prepared,

proactive

practice team

I would like to especially acknowledge the follow-

ing individuals:

Dr. Walt Talamonti, MD, Chair, Michigan

IPIP Steering Committee

Dr. Ernest Yoder, MD, Vice Chair,

Michigan IPIP Steering Committee

Dr. Joseph Fortuna, MD, Medical

Champion

Rose Steiner, RN, Director, Michigan IPIP

Dr. Kevin Piggott, MD, Chair, IPIP

Learning Collaborative

Quality Improvement Coach team volunteers:

Lou Ann Lathrop (General Motors), Chair

John Casey (Whitehall Group)

John Katona (Delphi)

Dave Lalain (AIAG)

Victor Lloyd (St. John Health)

Rebecca Snyder (Ford Motor Company)

Advisor to Michigan MPCC/AIAG IPIP process:

Barry Klein (GlaxoSmithKline

Pharmaceuticals)

Acknowledgments xvii

(This page intentionally left blank)

xix

T

his book is for those in the Practice or

staff activities of your organization whose

customers/payers may be encouraging or

requiring you to use Lean Six Sigma in your

workplace or to simply improve the way health-

care is being provided. The book is intended to

be a basic, easy-to-read, quick and handy ref-

erence to the process improvement topics that

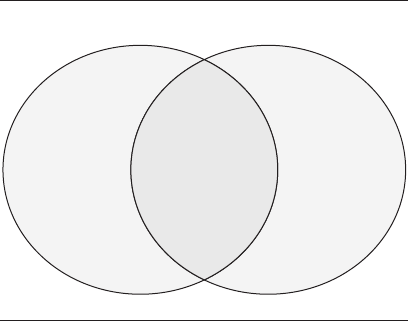

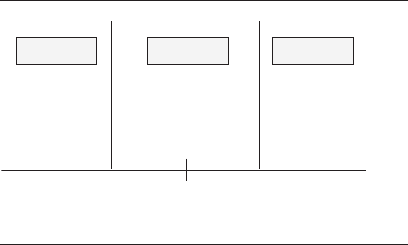

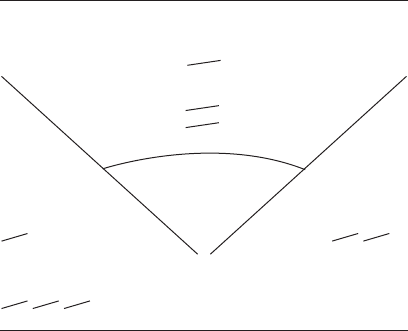

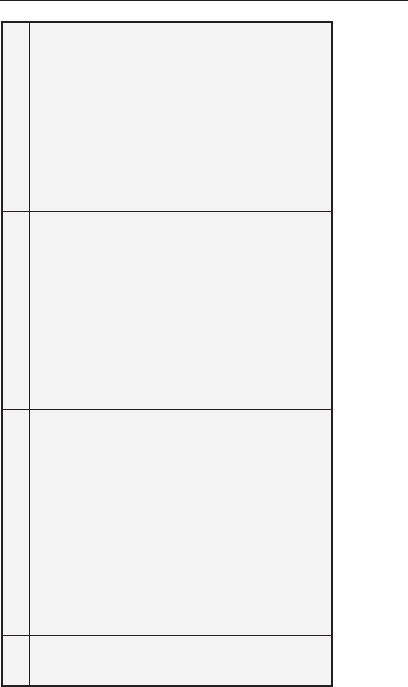

are so important in healthcare (page xx shows

a Venn diagram of tools found in this book). The

first seven sections of the book cover the basics

of Lean Six Sigma (“What Is Lean Six Sigma? ”

through “Lean Six Sigma Road Map for the Prac-

tice”) and how it can be applied and implemented

in the Practice. The tool matrix guide beginning

on page 2 has been arranged alphabetically for

ease of finding tools as needed. The remainder of

the pocket guide gives a brief description of the

various tools and methodologies used in Lean

Six Sigma. Each discussion has purposefully

Suggested Use of

This Book

xx Suggested Use of This Book

been kept short and simple to allow for a basic

understanding and includes some tips on how

or when to use the tool. If more detail is needed,

other references can be consulted to realize the

full impact of the tool.

Everyone in the organization, from the janitor

to the senior executive or Practice oversight com-

mittee, should know the basic information found

in this book. Some have felt in the past that this

type of information belonged only on the manu-

facturing floor. Today we have learned that there

is probably more opportunity within the Practice

than ever thought before (Berwick and Leape

Problem identification

Value stream map

Flowchart

Value analysis

Check sheet

Voice of the

customer

Histogram

Scatter diagram

Process

behavior chart

Measurement

systems analysis

Cycle time

Audit

Sampling

Pareto chart

Run chart

Stratification

Cause-and-effect chart

Brainstorming

Visual controls

Visual aids

7S

Problem analysis

Venn diagram of tools covered in this book.

Suggested Use of This Book xxi

1999). Especially since many healthcare practi-

tioners have received a large amount of scientific

training, the use of statistical tools to improve

processes in healthcare and quality of care and

services should be a natural combination.

Persons who can pass a designated test, either

internally created or one of many offered by var-

ious organizations, can be designated as Lean

Six Sigma Green Belts. Green Belts work with

teams to gather data and to analyze, improve,

and control the processes in the Practice. People

who become exceptionally expert in the use of

the Lean Six Sigma methods and processes and

who pass advanced testing are called Lean Six

Sigma Black Belts. Black Belts use experiments

and other advanced tools to help solve especially

difficult problems.

Your Practice may or may not have a Black

Belt (a full-time or part-time person dedicated to

doing Lean Six Sigma in your Practice). However,

everyone should become involved in continual

improvement efforts to help ensure your organiza-

tion’s survival and the improved care and health

of patients. Some process improvements can be

very simple to identify and implement while

others may take some time for the staff to fully

understand the dynamics of the issues involved.

These improvement efforts can be accomplished

by using this book and the tools within it to guide

your improvement projects.

xxii Suggested Use of This Book

In addition, you may deal with customer audit

personnel, government auditors, people desig-

nated as “rent a Black Belts,” or other coaches or

consultants to help with the advanced aspects of

Lean Six Sigma. By using all the resources that

are available, you can help your Practice stay

competitive in today’s global marketplace.

One of the biggest challenges in the Practice is

to allow time to understand the use of these tools

and to start collecting the data and information

that will be needed to make continual improve-

ment efforts a reality. Everything can be defined

as a process, and processes can be measured so

that they can be monitored for improvement. In

the past, you may not have thought about how to

measure work that is done in the Practice. Keep-

ing an open mind will be paramount to the suc-

cess of Lean Six Sigma in your Practice and to

making your work easier and more fulfilling.

Experience has shown that the journey can be

fun and rewarding for those who get honestly

involved in using the improvement tools and

methods. This effort is the “how to” of learning to

“work smarter, not harder!”

1

The DMAIC

Matrix Guide

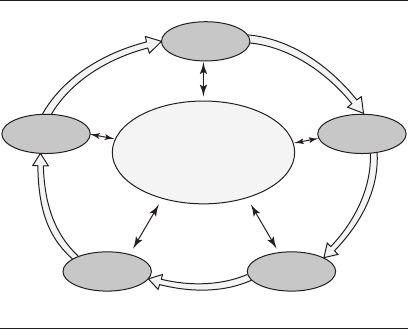

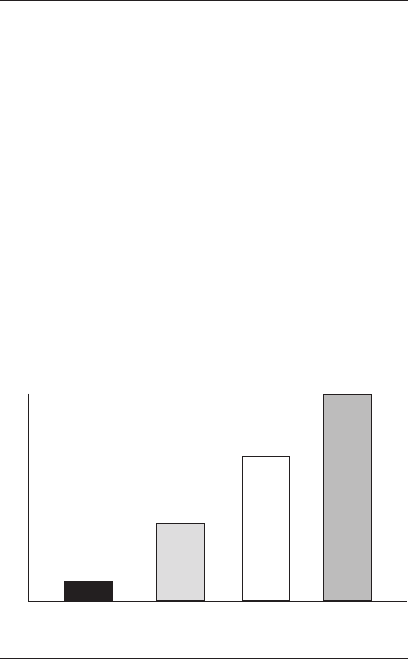

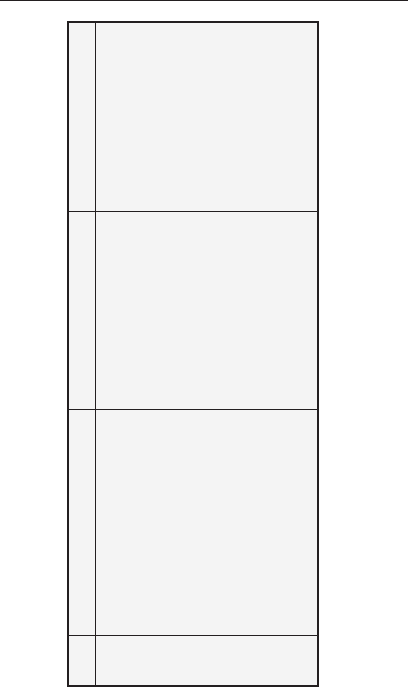

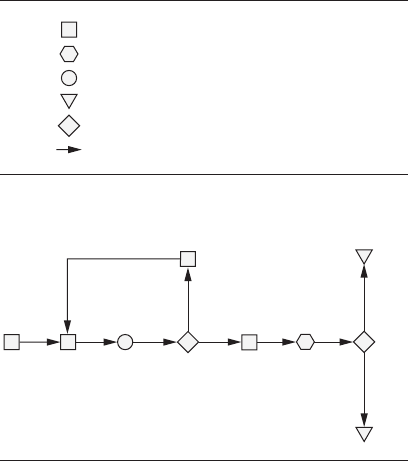

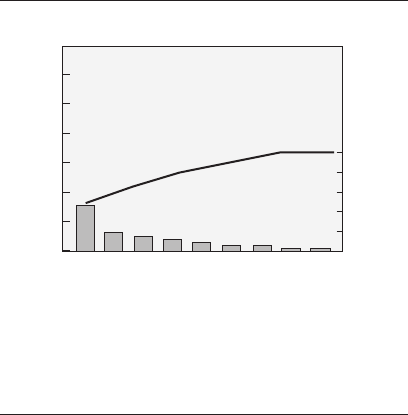

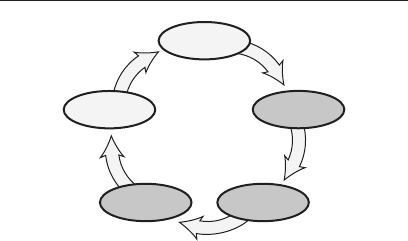

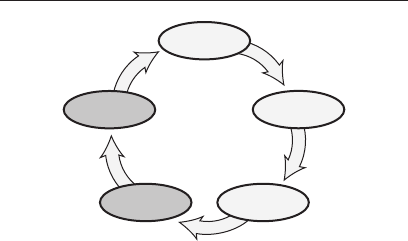

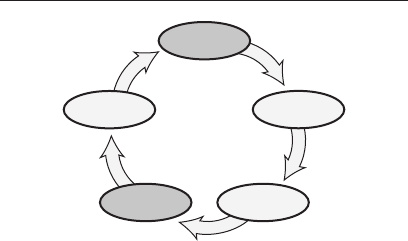

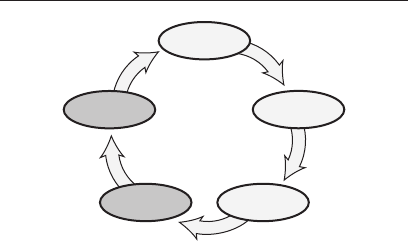

T

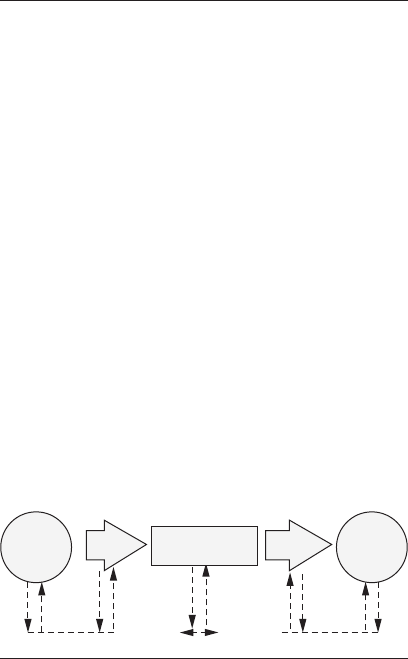

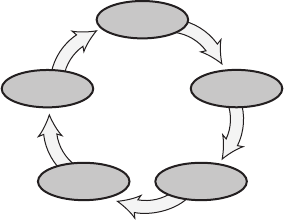

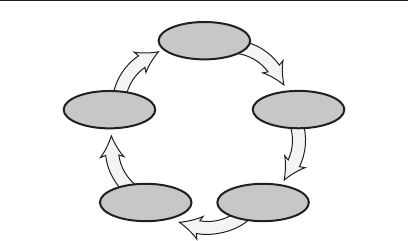

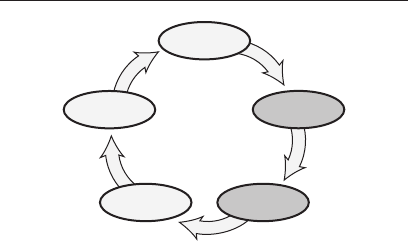

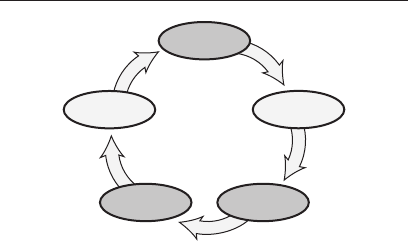

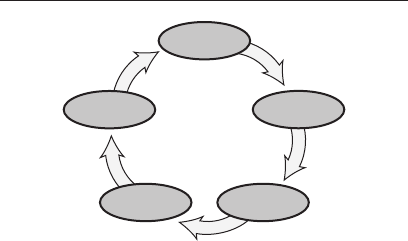

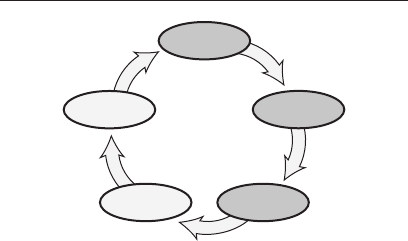

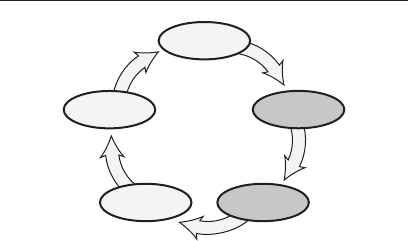

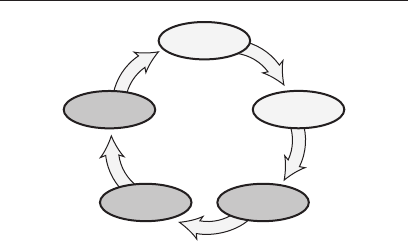

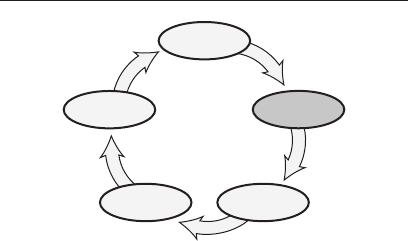

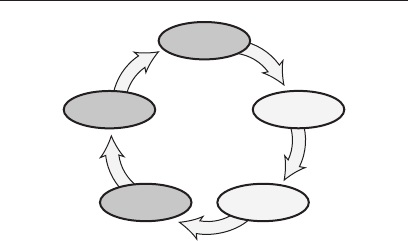

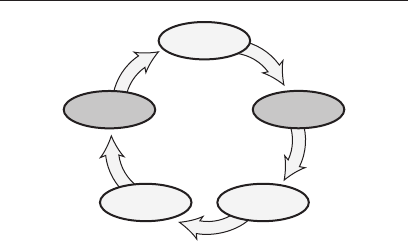

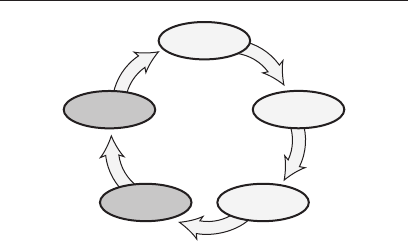

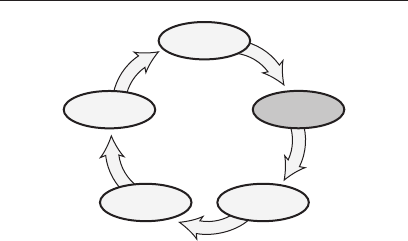

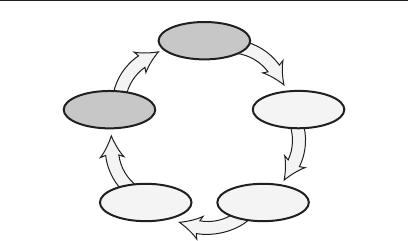

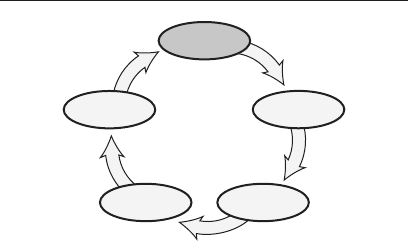

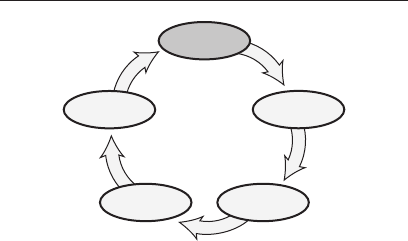

he DMAIC model (shown in Figure 1) is

referred to throughout this book. The acro-

nym stands for define, measure, analyze,

improve, and control. The reader will find the

Verify

Design

SDCA SDCA

PDSAPDSA

PDSA

MeasureControl

Improve Analyze

Define

Practice strategy

Employee involvement

Team meetings

Figure 1 The DMAIC model.

2 The DMAIC Matrix Guide

following matrix helpful as he or she matches

particular tools and approaches to particular

phases in the DMAIC process.

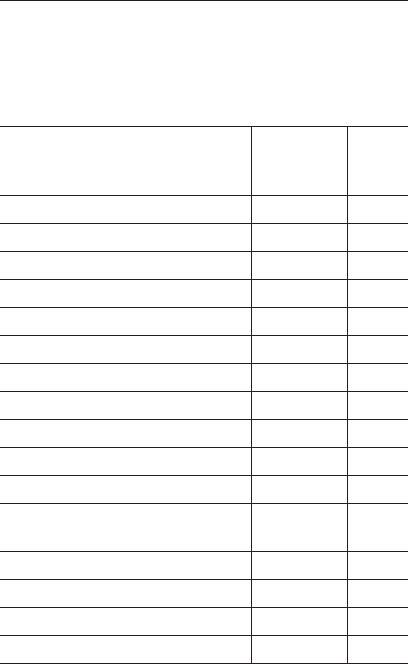

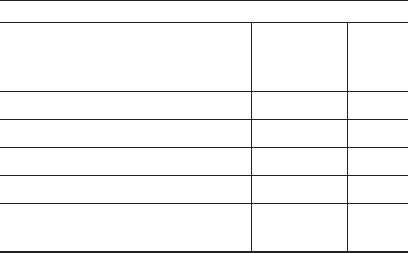

When used

in Lean

Name of tool/approach Six Sigma Page

7S DMAIC 53

Advanced practice quality planning D 58

Auditing DMAIC 62

Benchmarking MA 66

Brainstorming DAI 71

Business operating system (BOS) DMAIC 76

Cause-and-effect diagram DMA 79

Check sheets MA 84

Continual improvement AIC 89

Cost–benefit analysis DMAIC 93

Cycle time analysis DMIC 98

Failure mode and effects analysis DIC 101

(FMEA)

Flowchart DAI 113

Histogram M 118

Kanban IC 122

Lessons learned DIC 124

Continued

The DMAIC Matrix Guide 3

When used

in Lean

Name of tool/approach Six Sigma Page

Management involvement DMAIC 126

Measurement systems analysis MC 129

(MSA)

Mistake-proofing IC 133

Pareto chart M 136

PDSA cycle (plan–do–study–act) MAI 141

Practice strategy DMAIC 145

Problem solving I 148

Process behavior charts DC 152

Process identification D 158

Process improvement I 160

Run chart MC 163

Scatter diagram MAI 166

SIPOC diagram DM 170

Standard operating procedures IC 173

(SOPs)

Standardization DC 175

Systems thinking DI 177

Team meetings DMAIC 181

Teams D 185

Value analysis MAC 192

Continued

4 The DMAIC Matrix Guide

When used

in Lean

Name of tool/approach Six Sigma Page

Value stream map D 195

Variation reduction IC 199

Visual controls, aids IC 202

Voice of the customer DC 204

Walkaround/walkthrough/ DMAIC 207

waste walk

5

What Is Lean Six Sigma?

L6s

L

ean Six Sigma is a term describing the

overall concept of continual improvement

of everyday processes (Deming 1993). Con-

tinual improvement can be defined as the use of

problem-solving techniques and quick deploy-

ment to implement improvements, and then the

use of process behavior charts (Wheeler and

Poling 1998) to maintain the gains. Lean Six

Sigma is about strategic alignment, applied

learning, and culture or belief system transfor-

mation that uses four distinct but interrelated

characteristics: a strategy deployment approach,

a belief system, a statistical calculation, and a

suite of project improvement methods (Caldwell,

Brexler, and Gillem 2005). Lean Six Sigma is

being used in many organizations today in a

variety of applications (for example, schools, hos-

pitals, and private Practices). Basically, Lean Six

Sigma is about collecting data on a process and

using that data to analyze and interpret what

6 What Is Lean Six SIgma?

is happening in that process so that the process

can be improved to better satisfy the customer. A

basic process can be defined as an input, trans-

formation, and output (see Figure 2).

Lean Practice is simply the banishment of

waste. It is the elimination of waste by better

organizing and managing customer relations,

the supply chain, product development, and ser-

vice activities. Many service organizations, espe-

cially the larger ones, have been designed with

the idea of creating large service runs over short

periods of time (sometimes resulting in repetitive

checking of work done)—typically called mass

production. In Lean Practice, the organization

develops a process for processing/producing just

what is needed, as it is needed, by the patients/

customers that eliminates waste in time, energy,

effort, rechecking/verifying, inventories, mate-

rial handling, storage, and so on. This process is

also called the pull concept because the patient/

customer “pulls” what is needed from the suppli-

ers or Practice instead of the supplier making and

stockpiling large quantities until the customer

decides it wants some, as in mass production.

Transformation

(Process)

Input Output

Figure 2 The process model.

What Is Lean Six Sigma? 7

So, bringing these two concepts together we

get Lean Six Sigma for Healthcare. This is a pro-

cess that uses continual improvement techniques/

methodologies to eliminate waste in the Practice.

Waste is defined as anything that stifles health-

care staff personnel or patients, or results in

lost time, productivity, or simply sitting around

an office waiting for something to happen. But

is this really important in the way healthcare is

delivered today?

Dr. Donald Berwick has stated, “With the

rising complexity and reach of modern medi-

cine have come startling

levels of risk and harm

to patients” (Berwick and Leape 1999). Many

people who work in healthcare may not recog-

nize the things that they do as being part of a

process. Since they do not work repetitively as a

person in a factory running a machine, the Prac-

tice employee might be tempted to say, “I do not

have a process.” A process does not have to be a

repetitive task done exactly the same each and

every time. When we come into work each day,

we have general tasks that we do every day. The

specific items may change or be done in different

sequences; however, we do have procedures that

we follow to get our work done. This is what we

will be looking at and studying throughout this

guidebook.

Lean Six Sigma started at Motorola in the late

1980s as Six Sigma on the shop floor (process) and

8 What Is Lean Six SIgma?

then moved into the front office (transactional).

What we know today as Lean Six Sigma for

Healthcare has been honed with the addition

of lean methodologies at General Electric and a

growing number of other organizations. Following

a prescribed process, an entire organization starts

to look at everything that it does in the light of

reducing variation and waste—with the result

of increasing customer satisfaction. Customers

are defined as anyone from the next person who

uses the work we do (internal customer) to the

ultimate customer who uses the products or ser-

vices that our organization produces (external

customer). To assist in this process, sometimes

the supplier and customer are added to the basic

process flow (input, transformation, output),

creating the SIPOC (supplier, input, process,

output, customer) identification. This is espe-

cially useful in helping to define the boundaries

of what is to be studied (see Figure 3).

FeedbackFeedback

Transformation

(Process)

Input Output

Supplier Customer

Figure 3 The SIPOC model.

What Is Lean Six Sigma? 9

For some, the idea of improving a process

is a waste of time and should not be bothered

with (“we are already working the hardest that

we can”). Lean Six Sigma is not about working

harder, it is about working smarter! Juran (1964)

points out that the work we do is a result of the

fact that “changes creep up on us week by week,

a little bit at a time. Over a year or two, there

are 50 or 100 of these bits, which amounts to

quite a bit. The skills of the staff or managers

have not necessarily kept pace, and we wake up

to the existence of a wide gap.” This is one expla-

nation for why accidents and procedural errors

happen in healthcare today. If the root cause is

found for an accident or rejection of a product or

service, it usually can be traced back to either

many small changes that occurred in our orga-

nization or something having been omitted acci-

dentally between healthcare units.

Using Lean Six Sigma methodologies, we can

find those bits of change and decide which ones

should be fixed/modified and which ones need to

be improved. This process is not meant to be a

quick-fix (silver bullet) approach to the health-

care industry or individual patient care. The

methodical use of the tools over time will save

resources and effort (and lives) in doing our daily

jobs. This book provides an overview of the tools

and processes used in Lean Six Sigma. Detailed

explanations of the use of each tool or process can

10 What Is Lean Six SIgma?

be accessed readily in other references or on the

Internet. For many readers, this book will serve

as a quick reference to what you may already

have in your Practice that can be used by indi-

viduals and teams to improve overall processes.

11

Your Role in

Lean Six Sigma

I

n the Lean Six Sigma problem-solving pro-

cess, you may find a number of tools and

methods that you are already familiar with

and a few that are new to you. You may very well

ask, “How is this any different from what we

have done before?” The direct answer will need

to be given by your organization, and it depends

on the various programs that have already been

used. For many Practices, the Lean Six Sigma

effort is part of an ongoing evolution of how they

do their work to improve patient care. One of the

main things that you should notice is that every-

one will be more involved with problem-solving

efforts and with the everyday problems found in

patient care.

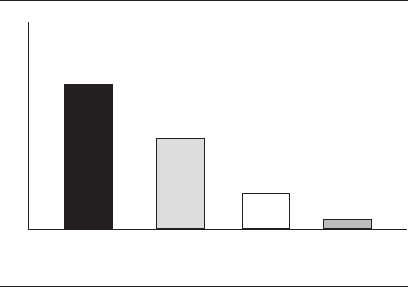

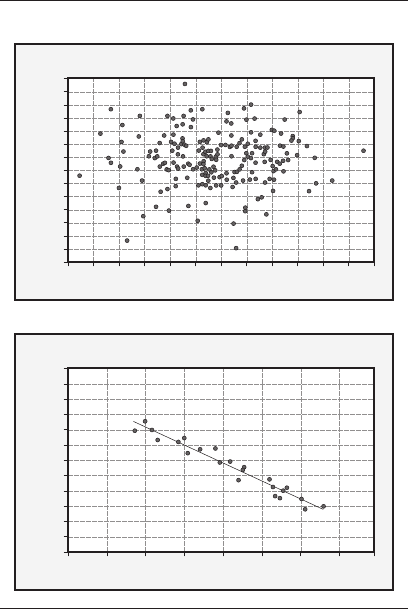

As we prepare for this exciting journey, first

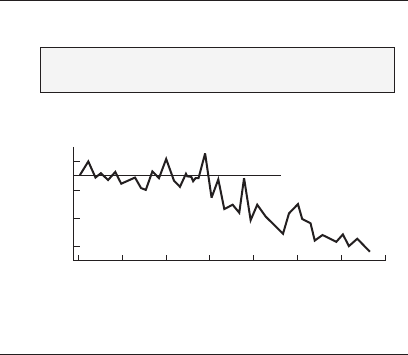

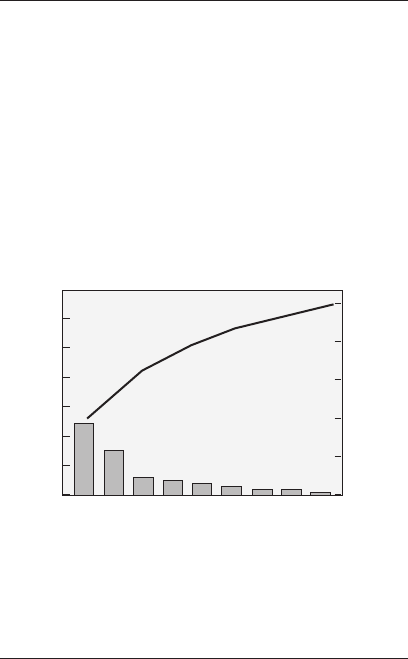

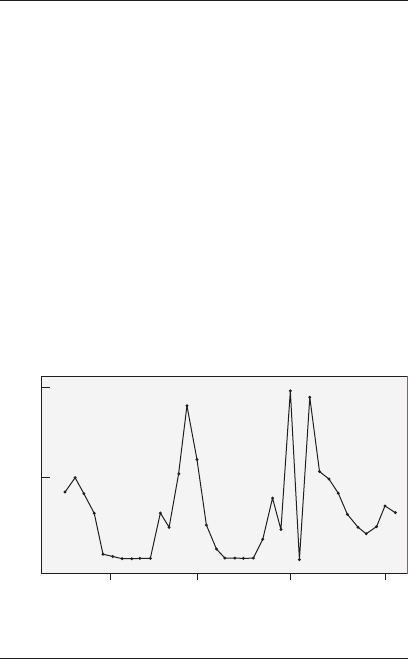

look at Figure 4. What would you predict as the

golfer’s next score if you were looking only at

the top box of numbers? Maybe a golf score

within the range 100 to 105 would be a good

12 Your Role in Lean Six Sigma

guess. Could you say anything about the golfer

in general? Now take a look at the graph of the

same numbers (this is called a run chart), and a

lot of information becomes very clear. Your new

estimated score for game number 205 might be

within the range of 92 to 97. You could also say

that up through game 180 the golfer was rela-

tively consistent, scoring around 120. But then

something happened—maybe lessons were

taken, new clubs bought, or a new grip started

to be used—and things began to improve. The

Which provides more insight?

What is your prediction for game number 205?

Game number 180 185 190 195 200 205

Golf score 112 119 102 104 100 ?

or

Golf Scores

Game number

Score

125

115

105

95

170 190185180175 195 200 205

Figure 4 More insight.

Your Role in Lean Six Sigma 13

golfer still has not stabilized from whatever hap-

pened and may improve even more. The graph

should be continued to monitor the golfer’s prog-

ress. Thus, as the saying goes, this one picture (a

run chart) is worth a thousand words. Now think

about the large number of “scores”—patient tests

or numerical values—that we have in healthcare

for a patient. The human body is also a system,

and by using some simple graphs we can work

with patients to help improve an individual’s

system (process) of health. One quick note here:

if we record a patient’s vitals in an electronic

system (that is, registry, spreadsheet, database),

then the computer can give us these graphics

with a couple of simple clicks.

During the change process, and while using

this book, you will be able to use the Lean Six

Sigma model for improvement. It has been shown

that by following a model or road map we can

usually accomplish something much quicker

than we can without a guide. Some organizations

today use a model called MAIC (measure, ana-

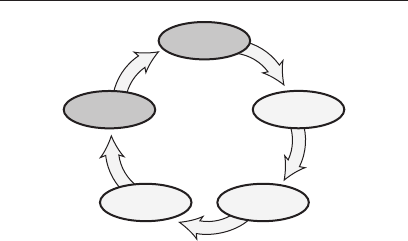

lyze, improve, control) as a road map. They refer

to this process as being able to do “magic” with-

out the G (garbage) that we find in many activi-

ties. Many organizations have added a D (define)

stage at the beginning of the model to identify

the customer process, resulting in the DMAIC

model (see Figure 5), which is commonly used in

the Lean Six Sigma approach.

14 Your Role in Lean Six Sigma

You may already use run charts, check-

lists, process sheets, standard operating proce-

dures, or any number of other such techniques in

your daily work. The use of the Lean Six Sigma

model for improvement should not replace any-

thing you’re currently doing. It should, however,

help you to review your daily work and look for

areas or methods to improve the process that

customers/patients want and need. Just because

we are doing the same things we have done

before, do our customers/patients still want the

same things from us? How many handwritten or

typed letters, memos, scripts, and so on, do you

Practice strategy

Employee involvement

Team meetings

Verify

Design

MeasureControl

Improve Analyze

Define

Figure 5 The DMAIC base model.

Your Role in Lean Six Sigma 15

see in a typical Practice today? Most work is now

done on computers and sent electronically.

We are beginning a journey of continual

improvement that can be used in our work and our

daily lives. Some of us have been on this journey

for some time while others may just be starting.

The process involves using what Deming (1993)

refers to as profound knowledge: appreciation

for a system, knowledge about variation, theory

of knowledge, and psychology. By following the

Lean Six Sigma methodology for improvement

you should see things around you work better, be

safer, and satisfy your customers more.

(This page intentionally left blank)

17

What Is Variation?

V

ariation is the basic principle that no two

things are exactly alike. There are usu-

ally many reasons for things not being

constant. Have you ever noticed while driving

that your vehicle does not stay exactly the same

distance between the white and yellow lines?

What causes this variation? Of course most of

us drive well, and the lines are on the road to

help us get to where we want to go without run-

ning into other vehicles or the ditch. But if we

could measure our vehicle’s distance between the

lines, we would find that minor drifts do occur

on a regular basis (common cause variation). If a

police officer pulls us over, however, some of the

reasons for drifting too far (special cause varia-

tion) might include these: wind velocity with a

high-profile vehicle, alcohol or drug involvement,

cell phone usage, inexperienced driver, poor

weather conditions, worn or damaged tires, or

other factors. The author was once pulled over by

18 What Is Variation?

the police because he was driving too close to the

white line. It seems that in that area, this could

only mean that the driver had been drinking

at the local casino! However, on dark, foggy

nights, the author prefers staying close to the

white line to give oncoming drivers more room on

two-lane country roads.

Similar things happen in healthcare. We have

procedures for how to do the work, but small

variations or personal preferences can and will

cause differences in the output of the process.

A common way to describe this is with the for-

mula Y = f(x), or Y equals the function of the x’s.

Graphically, this is most easily seen when using

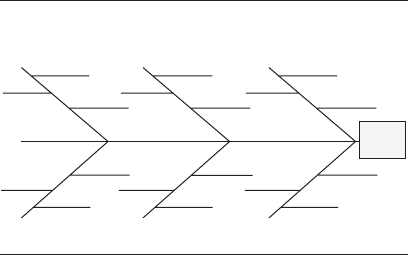

the cause-and-effect (fishbone) diagram. The

effect (the head of the fish) is the “Y” of the for-

mula, and the causes (the bones of the fish) are

the x’s. Note that this process will actually help

improve creativity in your Practice as the inputs

will become less varied and the activities can

become more robust for the customer outputs, or

patient care.

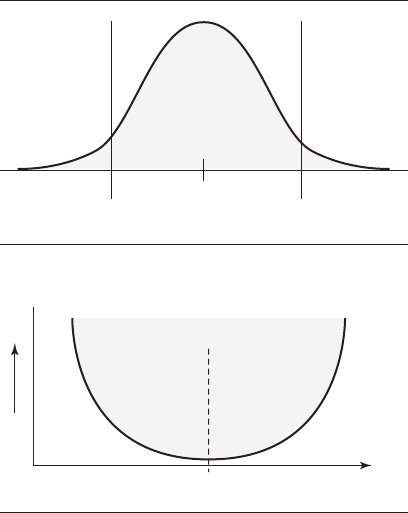

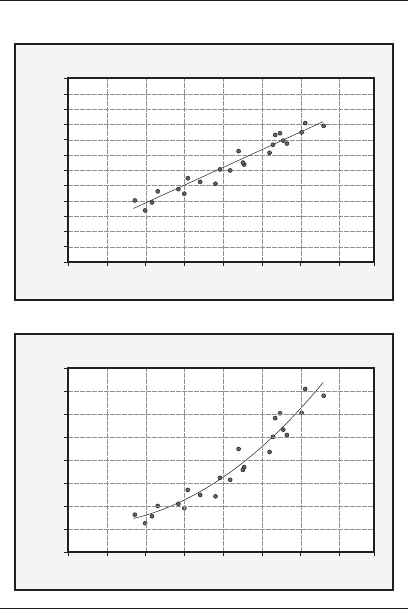

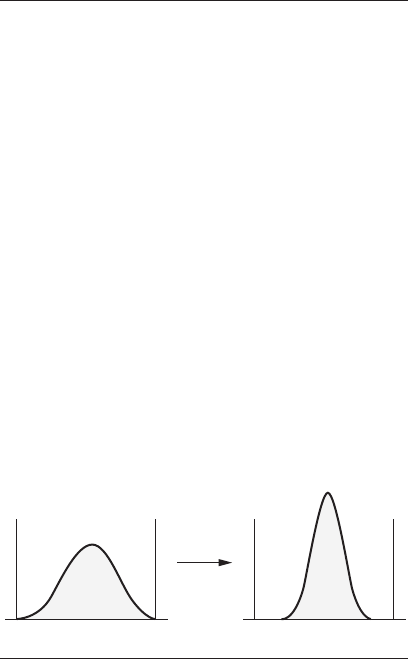

The traditional view of quality (sometimes

called the goalpost mentality—see Figure 6)

depicts the way many people regard varia-

tion when dealing with processes (for example,

blood pressure, HDL, LDL). It shows that some

processes (or items that are used) are clearly per-

formed within specifications or tolerances while

others are outside of specifications. There is no

What Is Variation? 19

relationship called out for Y = f(x), but the ques-

tion that should be asked is “What is the ‘real’

difference within the process or between a ser-

vice that is just inside the specification (a) and

another that is just outside the specification (b)?”

(See Figure 7.) Two competing services (say two

overnight delivery services) may be very simi-

lar and probably will function equally well when

used by your Practice. That is one of the reasons

companies who use this traditional model con-

tinue to provide services even if they are just out-

side the spec limits (that is, time of the actual

delivery)—because they think they can get a few

more sales to the customer and the deficiency

will not be noticed. This usually happens during

heavy office workload times when temporaries

are brought in and not trained very well.

No good Good No good

Loss No loss

Target

value

Lower

specification

limit

Upper

specification

limit

Loss

Y

Response

Figure 6 Traditional view of quality.

20 What Is Variation?

A different perspective on variation can be

seen in the Taguchi loss function model (see

Figure 8). This updated view of quality states

that all services (or processes), measured by the

x’s, should aim for a target value that is located

Target

value

Lower

specification

limit

Upper

specification

limit

ab

Figure 7 Part goodness.

Target

$

Loss

Y

Response

x

Poor Poor

Fair Fair

Good Good

Best

Figure 8 Taguchi loss function model.

What Is Variation? 21

at the middle of the specification limits (which

reflect customer expectations or healthcare spec-

ifications). In this case, services that are not

centered but similar to each other (for example

how well a report is written or the variation from

the expected wait time for a service) have nearly

the same “loss” to the customer (who may be a

manager or patient) and will not be accepted very

well if at the outer boundaries of the graph. As

the services offered move away from the target

value, the cost to the patient/customer (which

includes internal customers within the health-

care process), and thus society, increases as

issues or problems within the patient or with the

use of that service increase. The goal today is to

reduce variation (both common cause and special

cause—to be discussed later) so that the patient

feels better or the customer will see more service

delivery that is closer to the target value of what

they want versus what we can provide.

Recently, in ordering business cards from a

national office supply chain store, the author expe-

rienced a good example of poor service. The first

order was taken by a very knowledgeable sales-

person and was processed quickly and efficiently.

Then a couple of weeks later at the same store a

second order for a different card was placed. The

logistics manager for the store took the order

the second time and was totally unfamiliar

with the order process. Instead of a pleasant and

22 What Is Variation?

quick experience in ordering a simple item, the

experience was a long, drawn out, grueling effort

that left the author very frustrated and ready to

walk out of the store!

Another service example of the Taguchi loss

function is when people pay money to attend a

public seminar. The seminar is advertised to last

eight hours. If the seminar ends before the eight

hours, people may feel that they did not get their

money’s worth. If the seminar drags on beyond

the eight hours, people become upset because they

could miss their airplane, car pool, kids waiting

to be picked up, and so on. Thus, the seminar

leader must ensure that the attendees’ expecta-

tions are met within the boundaries advertised

and within the attendees’ wants and needs.

A patient may have been coming to a Practice

for a long period of time, and annual blood work

has shown that their HDL and LDL have been

within acceptable limits. Then, all of a sudden,

the numbers are not acceptable and a script is

written to help improve the numbers. However,

the cause of the just-out-of-specification num-

bers may be due to any number of variables rang-

ing from what the patient may have consumed,

contamination of the sample process, reading

of the blood work, or the instruments used to

make the measurements. However, if the annual

values of the HDL and LDL were available to the

What Is Variation? 23

doctor and patient in run chart format, then the

patient’s body process could be reviewed first to

see if there is something going on in the patient’s

life that actually requires medication, or to point

to a potential faulty reading and the need for

retesting.

Note: Be aware of the difference between

variation and variability. Variability comprises

three components: variation (discussed earlier),

instability (when a process has high amounts

of unknown [special cause] variation), and off-

target conditions (which happen when a process

is not centered between the engineering specifi-

cations) (Bajaria and Copp 1991).

(This page intentionally left blank)

25

Things You Might

Be Involved With

Y

our Practice may be using Six Sigma or

another quality methodology: lean office,

business operating system (BOS), contin-

uous improvement (CI), total quality manage-

ment (TQM), or a system known by some other

name. As a staff worker or supervisor of a pro-

cess, you will be asked by your Practice man-

agement to help implement improvement of the

activities or procedures that you work with. Your

challenge will be to look at the process with an

eye toward both simple improvements, which you

may already know need to be made (cleanliness,

too many signature requirements, information

just sitting around, recording data into a regis-

try, and so on), and how you can measure certain

factors to investigate better ways of performing

the process.

You will be asked to use the tools in this book,

and maybe others, to study your work area and

activities or procedures to look for improvement

26 Things You Might Be Involved With

ideas and ways to implement those ideas. You may

already be familiar with some of these tools; the

challenge will be in learning how to use them in

new ways to help your Practice to meet up coming

rule changes by payers, insurance programs, and

state or national programs or regulations.

Many of us find that by using a model or frame-

work we can do things more simply—“a picture

is worth a thousand words.” This is also true

when trying to improve processes. Dr. Kaoru

Ishikawa (the man who created the fishbone dia-

gram—see Figure 13, page 80) gave us a road

map to follow when first looking at a process that

needs to be improved. The words may not make

much sense right now, but as you work with pro-

cess improvement, you will come to understand

the importance of what is said here.

POINTERS IN

EXPRESSING QUALITY

1. Determine the assurance unit. (What is

to be measured?)

2. Determine the measuring method.

(How will we measure it?)

3. Determine the relative importance of

quality characteristics. (Is this key to

our process?)

Things You Might Be Involved With 27

4. Arrive at a consensus on defects and flaws.

(Does everyone agree on what is good

and bad?)

5. Expose latent deficiencies. (Look at the

process over time.)

6. Observe quality statistically. (Use process

behavior charting.)

7. Distinguish between “quality of design”

and “quality of conformance.” (Ishikawa

1976)

After we know what we can change (quality of

conformance) versus what we can not change

right now (quality of design—this is left to the

Design for Six Sigma [DFSS] process), we can

start working on our processes. Many Practice

personnel start out viewing this effort as only

more work, but many find that doing these stud-

ies actually saves them a lot of time and grief in

the future as things start to improve, work flows

better, and patients actually see results and

feel better. One question to ask yourself right

now is “How often does my process slow down or

stop because something is not working the way

it should?” Or “Is the output ever significantly

changed or even disregarded by someone down

the line (including my external customer/patient)

because something did not happen right at my

activity?” Note that this last question does not

28 Things You Might Be Involved With

ask if the business needs changed, which may

have caused the instance of variation. Working

on things that no one uses happens a lot for staff,

and dealing with this and the changing business

needs is also part of DFSS.

The next section discusses the DMAIC model,

where you will learn when to most appropri-

ately use the methods and tools presented in

this book to improve your or the patient’s pro-

cesses. As we proceed, please continue to keep an

open mind and be willing to experiment with the

tools. Be willing to look for ways to apply them in

your activities and procedures to learn as much

as you can about how a process operates. Also,

you may be expected to show patients, by use

of the graphical tools, how their health is being

affected, given the measurements that have been

taken over time. You will then be able to mod-

ify your work or instruct the patient as appropri-

ate and give your organization and your patients/

customers the best possible outcome.

29

The DMAIC Model

T

hroughout this book, you’ll find a number

of approaches and/or steps to assist you

in applying the tools or methods being

discussed. For the implementation of Lean Six

Sigma, a model has emerged that is well recog-

nized and which you’ll need to use in your Prac-

tice to show customers that Lean Six Sigma is

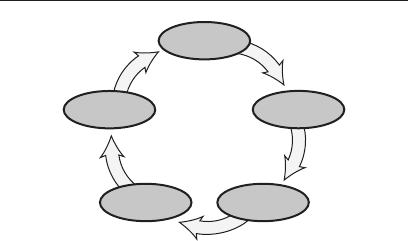

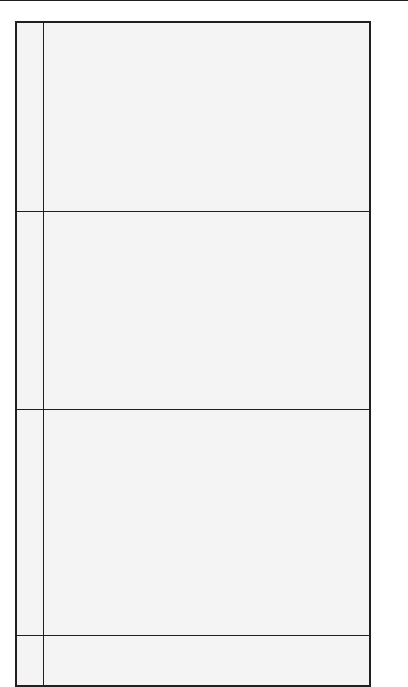

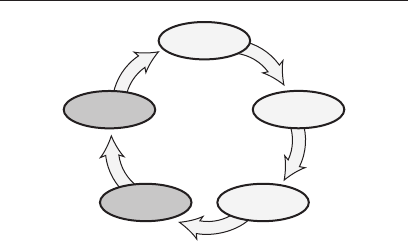

being used. The DMAIC model (see Figure 9)

stands for define, measure, analyze, improve, and

control, and is very similar to the PDSA (plan, do,

study, act) or PDCA (plan, do, check, act) models

that you may have heard of or are already using.

A key factor in each step of DMAIC is keep-

ing the focus of the Practice strategy in mind so

that all of the healthcare staff can work with the

methodology and focus the time and resources

to accomplish each of the phases and strive for

continual improvement. This is one of several

driving forces that make Lean Six Sigma differ-

ent from other quality improvement programs.

30 The DMAIC Model

Other driving forces include getting everyone in

the healthcare system involved (patients, pay-

ers, employers, and so on), getting the informa-

tion technology group to assist in supplying data

more quickly to everyone, and getting finan-

cial data in the form of cost-of-quality analysis.

Research (Stamatis 1996) is showing that many

organizations are finding more opportunity for

improvement to the bottom line in the office

than currently exists on many plant production

floors.

Practice strategy

Employee involvement

Team meetings

Verify

Design

SDCA SDCA

PDSAPDSA

PDSA

MeasureControl

Improve Analyze

Define

Figure 9 The DMAIC model.

The DMAIC Model 31

Staff personnel at all levels will be asked to

get involved with the Lean Six Sigma model and

look for continual improvement opportunities in

work areas. Basically, you will do the following:

Define Identify the issue causing

decreased customer satisfaction.

Measure Collect data from the process.

Analyze Study the process and data for

clues to what is going on.

Improve Act on the data to change the

process for the better.

Control Monitor the system to sustain

the gains.

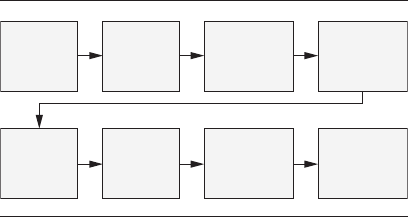

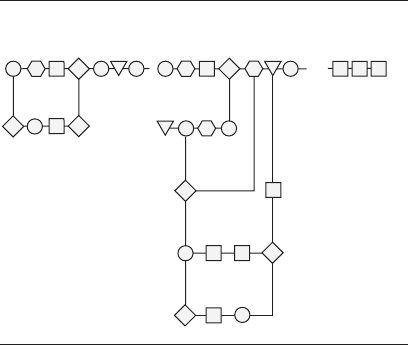

An example:

1. Select one important problem that you

have in the Practice.

2. Draw a flow diagram, or similar tool, of

the issue—how does it currently work?

3. Get concurrence from everyone who is

involved in that process that the flow

diagram is accurate. This in itself can

be a painful process of getting concurrence

and may actually solve some of the issues

as this process gets people aligned.

32 The DMAIC Model

4. Look over the flow diagram and ask

“Given what we know today, is this the

most effective way to do this?”

5. Make changes to the process as necessary

and update the process flow diagram

(note: this tool now becomes a simple job

aid, reminder, or training tool on how

that process works). Caution: be careful

about throwing technology at problems.

The process must work well first before

you computerize it. Otherwise, you

will only get the same problems as before—

only faster.

6. Now review the process and ask “What

could this process be?” or “How could this

process be more effective?”

7. Seek management approval and funding

for future changes.

8. Update the process flow diagram to match

the new flow. Train everyone in the new/

updated process flow using the flow

diagram/chart.

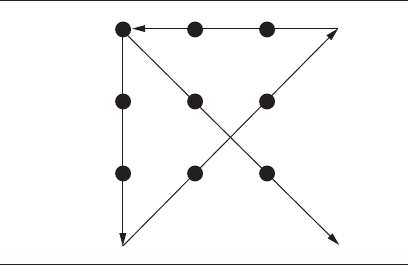

See Figure 10.

A number of tools and methods can be used in

the steps of the DMAIC model. This book gives

a quick overview of many of these items as they

relate to potential areas for improvement. More

The DMAIC Model 33

detailed information can be found in quality

control/assurance books, on the Internet, or in

quality improvement magazines or journals. The

DMAIC model uses the following tools:

Define

7S

Advanced practice quality planning

(healthcare APQP)

Auditing (sampling, sampling plans)

Brainstorming

Business operating system (BOS)

Cause-and-effect diagram (fishbone

diagram, Ishikawa diagram)

Look for

opportunities

for

improvement

Get staff

concurrence

Create

flowchart

Select

issue

Update

system

and train

staff

Future

improvements

Ask key

questions

Update

flowchart

Figure 10 Process improvement flowchart.

34 The DMAIC Model

Cost–benefit analysis (cost of quality,

quality cost, cost of poor quality, return

on investment)

Cycle time analysis

Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA)

Flowcharts

Lessons learned—review

Practice strategy

Process behavior charts

Process identification—storyboards

SDCA (standardize, do, check, adjust)

SIPOC (supplier, input, process, output,

customer) diagram

Systems thinking

Team development

Team meetings (huddles)

Value stream mapping

Voice of the customer (patient feedback)

Walkaround/walkthrough/waste walk

Measure

7S

The DMAIC Model 35

Auditing (sampling, sampling plans)

Benchmarking—start by setting the

current baseline for the process

Business operating system (BOS)

Cause-and-effect diagram (fishbone

diagram, Ishikawa diagram)

Cost–benefit analysis—start collecting

information

Cycle time analysis

Data collection—check sheets, histograms,

Pareto charts, run charts, scatter

diagrams

Identifying a data collection plan

Identifying variability—instability,

variation, off-target, cause-and-effect

diagram, process capability

Measurement systems analysis (MSA)

PDSA (plan–do –study/check–act)

Practice strategy

SIPOC (supplier, input, process, output,

customer) diagram

Stratification

Team meetings (huddles)

36 The DMAIC Model

Value analysis

Walkaround/walkthrough/waste walk

Analyze

7S

Auditing (sampling, sampling plans)

Benchmarking—how others do things

Brainstorming

Business operating system (BOS)

Cause-and-effect diagram (fishbone

diagram, Ishikawa diagram)

Check sheets

Continual improvement

Cost–benefit analysis (cost of quality,

quality cost, cost of poor quality, return

on investment)

Flowcharts

Practice strategy

Scatter diagrams

Stratification

Team meetings (huddles)

The DMAIC Model 37

Value analysis

Walkaround/walkthrough/waste walk

Improve

7S

Auditing (sampling, sampling plans)

Brainstorming alternatives

Business operating system (BOS)

Continual improvement

Cost–benefit analysis (cost of quality,

quality cost, cost of poor quality, return

on investment)

Cycle time analysis

Flowcharts

Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA)

Kanban (wait time, patient pull-through)

Lessons learned

Mistake-proofing

PDSA (plan–do–study/check–act)

Practice strategy

Problem solving

38 The DMAIC Model

Process improvement

Scatter diagrams

Standard operating procedures (SOPs)

Stratification

Systems thinking

Team meetings (huddles)

Variation reduction

Visual controls, aids

Walkaround/walkthrough/waste walk

Control

7S

Auditing (sampling, sampling plans)

Business operating system (BOS)

Continual improvement

Cost–benefit analysis (cost of quality,

quality cost, cost of poor quality, return

on investment)

Cycle time analysis

FMEA—update

Kanban

The DMAIC Model 39

Lessons learned—update

Measurement systems analysis (MSA)

Mistake-proofing

PDSA (plan–do–study/check–act)

Practice strategy

Process behavior charts

Run charts

Standard operating procedures

(SOPs)—update

Standardization (SDCA—standardize, do,

check, adjust)

Team meetings (huddles)

Value analysis

Variation reduction

Visual controls, aids

Voice of the customer (patient feedback)

Walkaround/walkthrough/waste walk

Most Practice staff members will find this pro-

cess very exciting as they will have the tools and

methods to demonstrate the improvements that

they are helping the organization to achieve.

There are times when a staff worker tries to tell

40 The DMAIC Model

a supervisor that something is wrong with a pro-

cess. Now we have the means to not only tell but

also show and demonstrate what needs to be

done. Following this process creates a road map

for continual improvement and, once started,

it is a never-ending journey. These tools and

methods have proven themselves useful every-

where: from shop floors to office settings, from

schools to hospitals, and even from churches to

the home. Also, if your Practice is currently plan-

ning on achieving ISO 9001 registration, Patient-

Centered Medical Home status, the Malcolm

Baldrige National Quality Award (or related

state-level award), or any number of other qual-

ity improvement–based awards or recognitions,

one of the baseline requirements is the ability to

demonstrate that continual improvement is actu-

ally being achieved.

41

Teams

T

he first thing we need to look at with respect

to teams is the difference between a team

and a group. A group (as in a natural work

group or department within the Practice) is a col-

lection of individuals who may be working toward

a common goal but who are not necessarily inter-

dependent. A team is a group of people who have

come together for a specific common purpose—

often to be accomplished within a specific time

frame—and has established a common definition

of what the members will be doing. Each person

understands and can discuss the common objec-

tive. Many philosophies and books are available

on teams, team building, and how to create effec-

tive teams. For example, the American Society

for Quality’s Team and Workplace Excellence

Forum has a lot of material.

An important problem many managers (those

who direct or run the Practice) face with respect

to teams is failing to ask individuals in the group

42 Teams

what they want from their experience on the

team! Lack of communication within the team

and between it and management thus causes a

vast number of failures. Finding a solution to

this should be the manager’s number one con-

cern any time groups of people come together.

Just saying the words one time is not enough for

effective communication to take place.

The second-most-important issue has to do

with the team itself. The members must be able

to answer three basic questions before they can

start and continue the process of teaming. These

questions are summed up in the acronym MCG.

M stands for “Who will be the members on the

team and why?” C stands for “Who will handle

what roles and responsibilities, and who is in

control?” G represents “What are the goals of the

team?” and ensuring that those goals are com-

municated to everyone who interacts with the

team. Each team needs to ask these three ques-

tions and ensure that its members share a com-

mon purpose.

MCG can be expanded by using another acro-

nym, SGRPI: systems, goals, roles, procedures,

and interpersonal relationships. The term systems

refers to thinking about how the team fits into

the structure of your Practice. Goals, as in MCG,

refers to what the team wants to accomplish

and communicating that to others. Roles, as in

the C of MCG, refers to the various roles involved

Teams 43

in a well-operating team and who will fill each.

Procedures refers to agreed-to and communi-

cated ground rules and logistical agreements

that the team has made with itself. Interpersonal

relationships refers to the relationships that any

team must work out in advance, as this becomes

a major issue if things are not resolved early.

People need to know how to relate to each other

and agree that they are all working for a common

purpose.

The following are some rationales for team

building from the National Training Laborato-

ries Institute (1984):

The Obvious

Goal clarity and

commitment

Surfacing control or

influence issues

Inclusion/cohesion

needs

Exploration of

working norms

Control/management

of destructive

competition

The Less Obvious

Identifying wants and

needs

Support needs

Creative

interdependence

(synergy)

Discovery of intrinsic

needs

44 Teams

Every team must go through a series of stages

toward group actualization. Five states com-

monly involved are: forming, storming, norming,

performing (producing), and ending. This process

usually takes a lot of time, and if at any point

something changes (for example, new managers,

new team members, economic conditions, a sig-

nificant emotional event experienced by one of

the existing members, and so on), the team as a

whole may need to go back to some prior stage

and repeat their efforts in order to become a top-

performing unit. Failure to follow these basic

stages is the most common reason why some

teams never achieve their full potential.

You should keep in mind several points at each

stage. Forming involves the people on the team

getting to know and trust each other. There can

be many frustrations here (for example, lack of

action, no clear assignment, poor communication,

and so on), and there is a lot for the team to work

through leading to the ultimate goal of accep-

tance and commitment of the group to becoming

a team. In storming, team members need to work

out their differences with each other. Because of

the forming activities, team members should feel

they are able to talk things out with each other

without hurting feelings or risking rejection just

because they see things differently. The pri-

mary outcome of this stage should be to clarify

the team’s major activities and develop members’

Teams 45

sense of belonging to the team. Norming occurs

when the team sets its boundaries and members

become more sensitive to each other and to the

goal or goals of the team. The team is now ready

to work on projects and enjoy a level of internal

support. In the performing stage the team can

work to full capacity to achieve its goals with

the pride that develops from performing well.

The last phase is ending. We all at various times

in our lives must deal with something coming to

an end. At the end of a team, or on losing a team

member, we want to be able to have satisfaction

with, and recognition of, a job well done.

Many managers want teams to immediately

jump into the performing stage of teamwork,

but this usually causes friction and a discon-

nect within the group, which has not been given

the opportunity to form into a team. Each team,

ideally during its formation phase, will identify

what its goal or purpose is for existing. There are

a number of team structures or types of teams:

• Cross-functional team. Members come

from various functional areas of the

organization and/or customers and

suppliers to achieve the goals of the team.

• Improvement team. Has a specific assigned

task of making one or more operational

improvements (cost, cycle time, quality) in

the Practice.

46 Teams

• Self-directed team. Operates with virtually

no management or supervisor involvement.

Its members have been given the time and

resources to accomplish the tasks assigned

to them.

• Quality circle. A team with the specific

assigned task of improving the quality of

an operation, service, or product. These

groups are commonly called improvement

teams today.

• Project team. A project-focused team that

has a specific goal to accomplish. It could

be a start-up of new activities, the launch

of a new product or service, a preventive

maintenance or cleaning program, or

other goal that may not involve a continual

improvement issue.

A team is far more than just a group of peo-

ple who happen to work in a given area. Well-

functioning teams take time to form and arrive

at their level of functionality, but once that has

taken place such teams have a lot of fun and take

pride in what they accomplish. Your overall goal

should be to develop well-functioning teams in

your Practice to achieve customer satisfaction

and continual improvement.

47

The Lean Six Sigma Road

Map for the Practice

A

s you prepare for the Lean Six Sigma

journey, you’ll do well to take a look at

the following suggested road map:

1. Develop a flowchart (or similar tool) of

a current significant process—“as is”—in

your Practice.

2. Recognize that variation exists in

everything you do—standardize the

process throughout the Practice.

3. Develop/refine measures of work for

customer satisfaction in the process.

4. Identify what the patient/customer wants

and needs—reduce variation around

this target.

5. Develop a “should be” or “preferred state”

process flow map.

48 The Lean Six Sigma Road Map for the Practice

6. Use a problem-solving methodology to

plan improvements.

7. Follow the PDSA model to deploy the

improvement.

8. Monitor the process using run charts or

process behavior charts.

9. Incorporate new technology where

appropriate.

10. Update standard operating procedures

or policies and lessons learned.

11. Celebrate successes.

12. Repeat the road map for continual

improvement—PDSA/SDCA.

49

Summary

W

e are starting a journey of continual

improvement in your Practice. The way

may be familiar to a lot of you as you

have been using the tools and methods for some

time. Others of you may be new to this path, and

through this book the author hopes to assist you

along the way. This book is designed to be a guide

rather than a detailed description of each tool

used. Follow the process, and use what seems

to be appropriate at each step. Every tool and

method will not be used each time a new study

starts. You may even find uses for these tools and

methods in different phases of the DMAIC model,

and that is encouraged. The goal of all this work

is to continually improve your procedures and

activities to satisfy your patients and customers

(both internally and externally) and increase the

effectiveness of your total Practice.

50 Summary

Here are some other points that healthcare

professionals should remember when using this

process:

1. If the method seems to be getting too

complicated, it probably is, and you should

step back to see if you can simplify what

you’re trying to study!

2. Asking patients to wait for long periods of

time is waste! Find a better way.

3. Most problems can be solved without using

designed experiments. If the process is

an old, established one and it used to work

okay, then keep asking why it isn’t now

until you find the problem!

4. Remember the KISS principle: keep it

simple (keep it simple staff, keep it simple

statistician, or keep it statistically simple)!

5. Sometimes all you need is an updated

histogram or flowchart to see the problem!

6. Never give up!

7. Have fun!

At times, your Practice might run into problems

that seemingly can not be solved, or you just don’t

have enough time and resources to handle every-

thing. It will be during those times that con-

sultants or other specialists may be called in to

Summary 51

assist with the issues at hand. Many times such

people will have advanced training in the tools

and methodologies discussed in this book. We

usually call these people “Lean Six Sigma Black

Belts,” and they may ask your team to start a

“Green Belt project.” Since that is what you are

doing with this book—Lean Six Sigma Green

Belt projects—you will be able to call yourself a

Lean Six Sigma Green Belt.

If you would like to earn a formal title in this

arena, check with a local quality practitioner or

contact the American Society for Quality (ASQ)

about the Certified Quality Improvement Asso-

ciate (CQIA) or other certification processes or

examinations for healthcare professionals. ASQ

can be reached at 800-248-1946 or http://www.

asq.org for more information.

(This page intentionally left blank)

53

Tools

Define

Measure

AnalyzeImprove

Control

7S

An old Japanese quality auditing technique,

after the initial greetings in the front office, is

to visit a rest room in the hourly working area

before conducting the rest of the audit. The

purpose of this detour, rather than to use the

facility, is to check for the cleanliness of the rest

room. The belief is that if management can not

54 7S

provide clean facilities for staff, then a number

of other processes may be at issue in the organi-

zation. Have you ever used a dirty restroom at a

gas station or a restaurant? What did you think

about how that organization handled other activ-

ities on the property?

How organized is your Practice and work

area? Is there dust, grease, food scraps, eye irri-

tants, trash, or other unclean issues in the work

space? An unclean office setting hides safety

hazards, health risks, and equipment problems,

shows a lack of pride in work, and signals a host

of other issues. If your office does look clean on

the surface, how about the way paperwork is

stored in your Practice? Does the doctor have all

of the correct files available at a single glance, or

is everything stored in patient files so that each

packet is different? How much time do patients

have to wait in the various waiting rooms in your

Practice? How about other personnel that work in

the Practice? Is everything available in a timely,

orderly manner, or is information typically miss-

ing or hard to find when needed to accomplish

the tasks at hand?

It has been researched and proven that

cleanliness/orderliness at home and work leads

to much more productive settings and more pride

in what we do. Some people feel that far too much

time is spent talking about uncleanliness and

7S 55

disorder; however, it has been shown to be one

of the more important factors contributing to

why things do not always work the way they are

supposed to. When things are not organized and

clean, the likelihood of something going wrong

increases exponentially.

The Japanese created a process referred to as

the 5S method, which work groups use to ensure

a clean, organized, and safe work environment

(see Table 1). Many work teams spend a specific

amount of time each day to ensure that their

work areas are cleaned. This has the added ben-

efit of allowing the staff who use the work area

to take a close look at their environment for signs

of future trouble.

The classic 5S includes sort, set in order, shine,

standardize, and sustain. For 7S, we are adding

safety, oversight.

Table 1 5S chart.

Japanese (S) Translation English (S)

Seiri Cleaning up Sort

Seiton Organizing Set

Seiso Cleaning Shine

Seiketsu Standardizing Standardize

Shitsuke Training & discipline Sustain

56 7S

The 5S method was created for a manufactur-

ing setting. In a medical Practice, we must also

be on high alert to ensure the safety of staff and

patients as well as the oversight of our processes.

Thus, we now have what can be called the 7S for

the healthcare Practice. These sets include:

• Sort. Review and sort work tools and

materials to ensure that all unnecessary

items are removed and to ensure

workplace organization. Look for

unnoticed dangers: unprotected moving

objects (such as file drawers), exposed

or damaged electrical wires, and other

issues that might get in the way of doing

the work safely.

• Set in order. Have a place for everything

and keep everything in its place when not

in use. People need to know where things

are supposed to be. Also, apply ergonomics

to help prevent movement injuries.

• Shine. Clean everything in the work area

inside and out regularly, inspecting each

item for signs of defects or wear or other

signs of future trouble.

• Standardize. Using the first three S’s,

establish a pattern of how things are to

be done. This is not meant to reduce

creativity, but to help ensure that things

7S 57

are done in a way that helps to reduce

variation in the process. Continually

maintain what has been accomplished

and ensure that standards are lived up to.

• Safety. The process of avoiding injuries to

patients from the care that is intended

to help them.

• Oversight. Medical oversight is the

process of reviewing care that is provided

to patients, to ensure their safety.

• Sustain. Reinforce all of the above to

ensure that this process becomes a part

of your daily work.

The task for you and your fellow staff is to clean

your work areas, address any unsafe issues that

currently exist, and prevent those that may occur

in the future. Put a red tag or other identification

on anything that should be addressed. If there is

a safety officer in your organization, ask him or

her to periodically check your work space to help

ensure a safe and clean working environment.

58 Advanced Practice Quality Planning (Healthcare APQP)

Define

Measure

AnalyzeImprove

Control

ADVANCED PRACTICE QUALITY

PLANNING (HEALTHCARE APQP)

Have you ever heard the old saying “a stitch in

time saves nine” or “an ounce of prevention is

worth a pound of cure”? How about “measure

twice, cut once”? What do these sayings mean?

Most people will answer by saying that if you

plan ahead of time, you can save time, money,

resources, and sometimes frustration. In my own

experience I have sometimes started a project

only to have the parameters change later and

have to redo work that was already done. The

idea that we can plan, as best as possible, ahead

of time to help prevent surprises and save valu-

able resources works in our jobs as well as in our

homes. Anything that is to be done can be thought

out first, or written plans can be completed to

lay out a blueprint of what we are going to do.

Advanced Practice Quality Planning (Healthcare APQP) 59

This concept is referred to as advanced practice

quality planning, or healthcare APQP.

APQP is a process whereby we first look at

the parameters of what we are going to do. Do we

have the right amount of resources or material

available? Do we have the right people to do the

job or provide the service? Do we have the right

tools or training to do the job well? Do we know

the correct way of using everything we have to

provide a safe environment for ourselves, our

patients, and other customers? All these ques-

tions, and many more, should be answered before

we start work! One of several tools you can use to

ensure that you have thought of all the elements

(causes) that will give you the desired output or

effect is the cause-and-effect diagram (see page

79). You can also think of APQP as the first step

of the PDSA cycle, where you are going to plan

before you do something.

In planning to meet future medical require-

ments, such as those espoused by the Committee

on Quality of Health Care in America in Crossing

the Quality Chasm (2001), we must ensure that

the six aims for improvement are addressed:

• Safe. Avoiding injuries to patients from

the care that is intended to help them.

• Effective. Providing services based on

scientific knowledge to all who could

benefit, and refraining from providing

60 Advanced Practice Quality Planning (Healthcare APQP)

services to those not likely to benefit

(avoiding underuse and overuse,

respectively).

• Patient-centered. Providing care that is

respectful of and responsive to individual

patient preferences, needs, and values,

and ensuring that patient values guide

all clinical decisions.

• Timely. Reducing waits and sometimes

harmful delays for both those who receive

and those who give care.

• Efficient. Avoiding waste, including waste

of equipment, suppliers, ideas, and energy.

• Equitable. Providing care that does not

vary in quality because of personal

characteristics such as gender, ethnicity,

geographic location, and socioeconomic

status.

Your organization may very well use some of

the traditional quality tools (check sheets, run