Midwest Social Sciences Journal Midwest Social Sciences Journal

Volume 24 Issue 1 Article 9

11-16-2021

Transforming Criminal Justice Internships into Capstone Courses: Transforming Criminal Justice Internships into Capstone Courses:

A Response to the Challenges of the COVID-19 Crisis A Response to the Challenges of the COVID-19 Crisis

Beau Shine

Indiana University Kokomo

Kelly Brown

Indiana University Kokomo

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/mssj

Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and

the Online and Distance Education Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Shine, Beau and Brown, Kelly (2021) "Transforming Criminal Justice Internships into Capstone Courses: A

Response to the Challenges of the COVID-19 Crisis,"

Midwest Social Sciences Journal

: Vol. 24 : Iss. 1 ,

Article 9.

DOI: 10.22543/0796.241.1046

Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/mssj/vol24/iss1/9

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in

Midwest Social Sciences Journal by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please

contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected].

92

Transforming Criminal Justice Internships into Capstone Courses:

A Response to the Challenges of the COVID-19 Crisis

*

BEAU SHINE

Indiana University Kokomo

KELLY BROWN

Indiana University Kokomo

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the declaration of a national

emergency that closed universities across the nation in March 2020. With

no warning, faculty were required to change classes from face-to-face to

completely online instruction. This situation posed many difficulties,

particularly for faculty who were teaching and supervising students

completing internships. Interns were removed from their internships

abruptly as agencies and departments moved to essential personnel only.

Faculty scrambled to create online learning experiences that met academic

learning outcomes and the goals of criminal justice students enrolled in

these courses. This paper details our experiences with these challenges,

particularly as we revised criminal justice internship courses and

developed capstone courses to replace face-to-face internship experiences.

Although the challenges we faced involved criminal justice internships,

they were not unique to the major, and the approaches taken and lessons

learned are likely applicable to a host of disciplines.

KEY WORDS Internship; Capstone Course; COVID-19

Internships are a valuable part of the undergraduate criminal justice curriculum. Whether

completed as requirements for the degree or as electives, internships provide students

with personal, professional, and practical benefits (Kuh 2008; Lei and Yin 2019).

Internships, one example of a high-impact practice (HIP) in institutions of higher

education, lead to deep learning, enhanced student engagement in their learning,

persistence in college, and increased graduation rates (Kuh 2008, 2013; O’Donnell 2013).

Additionally, for many students, internships are the first practical exposure to a potential

*

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Beau Shine, 2300 S. Washington

St. KE 336, Kokomo, IN 46902; (765) 455-9327.

1

Shine and Brown: Transforming Criminal Justice Internships into Capstone Courses

Shine and Brown Transforming Internships into Capstone Courses 93

career in criminal justice. Students who have never experienced firsthand the work of the

criminal justice system such as policing, courts, corrections, and other related work are

able to utilize internships as a mechanism to evaluate their career interests and to

determine whether the career is a good fit for them. Students who complete internships

are presented with the opportunity to connect with and build relationships and networks

with criminal justice practitioners. Further, students completing internships are able to

develop soft skills that come with working in a professional environment (e.g., time

management, professional etiquette, enhanced communication; Lei and Yin 2019); thus,

internships provide hands-on integrative and collaborative learning, build connections to

the community, build professional relationships and experience, bridge the gap between

theory and practice, increase student learning of academic subject matter, allow students

to explore career options, and potentially lead to job offers upon graduation (Callanan

and Benzing 2004; Crain 2016; Finley and McNair 2013; Knouse, Tanner, and Harris

1999; Kuh, O’Donnell, and Schneider 2017; Murphy and Gibbons 2017; O’Neill 2010;

Schneider 2015; Taylor 1988).

The COVID-19 crisis created havoc for postsecondary institutions worldwide.

Virtually overnight, faculty had to transform face-to-face classes into online courses. This

created numerous challenges, particularly for faculty supervising internships. Many

students were informed that they would not be able to continue working as interns for the

agencies, departments, and courts at which they had been placed. This change was due in

part to agencies being restricted to essential employees only and in part to the concerns

that universities had about allowing internships to continue, even when agencies

approved the internships’ continuation, because of the increased risk to the students’

health and well-being. Faculty had to rush to find online alternatives to these valuable

applied-learning experiences, and administrators and faculty had to navigate the murky

bureaucratic policies and procedures of academia in a relatively short time to implement

the necessary changes.

This paper is based on one case study, our experience at one Midwestern

university, and discusses the practical and academic concerns of moving students from

internships to alternative methods of instruction while still achieving an HIP that allowed

students to achieve the course learning objectives. Although ours is one story of many

across the nation, we believe that sharing our experience and insight from the COVID-19

crisis may help others learn from how we managed the crisis and the challenge it

presented, and that we can begin a conversation to learn together how to respond should

another pandemic or other disaster require similar conversions in the future.

THE CHALLENGE

The COVID-19 pandemic created numerous concerns for academia at every level. One

such concern was the effect of the closure of university campuses and the requirement

that students and faculty learn and work remotely (Times Higher Education N.d.).

Faculty, many with no prior online teaching experience, were instructed to convert their

on-campus classes to a remote/online format in the middle of the semester. This was an

enormous challenge for all instructors and courses across campus, particularly given the

2

Midwest Social Sciences Journal, Vol. 24 [2021], Iss. 1, Art. 9

https://scholar.valpo.edu/mssj/vol24/iss1/9

DOI: 10.22543/0796.241.1046

94 Midwest Social Sciences Journal Vol. 24 (2021)

urgency of the situation; however, internships presented special challenges. Most students

completing internships during the spring semester of 2020 were told they would not be

able to complete their internships on-site; thus, faculty and administrators were required,

with little notice, to determine how to revise field-placement internships into online

learning experiences that met student learning goals, fulfilled the requirements of HIPs,

and kept students engaged.

Fortunately, much like criminal justice practitioners, educators are afforded a

certain degree of freedom in our work. In mid-March of 2020, during the COVID-19

crisis, faculty were able to work creatively with colleagues to identify revisions to the

courses that addressed academic concerns about maintaining achievement of course

learning objectives as well as students’ (particularly graduating seniors’) natural concern

and trepidation over losing valuable experience that enhanced their understanding of the

field and provided many practical benefits toward achieving their career goals. Most

students were particularly understanding, given the gravity of the situation and that

events unfolding were not due to the choices of the instructors, university administrators,

or internship-site practitioners. Students were able to see that the COVID-19 crisis had

abruptly and severely interrupted our academic and personal lives in ways that were

largely unforeseeable in the time preceding the crisis, and they were willing to work with

faculty to achieve their academic goals in ways different from those originally planned.

In short, students were largely cooperative and understanding rather than resentful and

critical of the changes that instructors had to make to classes.

THE SETTING

Our campus is a regional campus of a Big Ten university. Approximately 3200 students

were enrolled in classes during the 2019–2020 academic year. The student-to-faculty

ratio is 16:1. The campus offers more than 60 degrees, including undergraduate and

graduate degrees. With approximately 140 majors, criminal justice is one of the largest

on campus. Students enrolled in criminal justice are required to complete a capstone

experience as part of the Bachelor of Science in Criminal Justice degree requirements.

They may choose from either an internship (the most common choice) or a research

practicum, depending on their career goals and interests. Thirteen students were

enrolled in the internship course during spring semester 2020. Six of these had

completed all their required internship hours prior to the COVID crisis and the

subsequent cancellation of internships or were able to continue with their placements

after the campus was closed. Thus, seven students had to abruptly end their field

placements and complete the course online.

THE SOLUTION

The most pressing issue that the pandemic presented to the faculty supervising

internships during the 2020 spring semester was how to replace students’ lost internship

hours. The most logical response was to convert internships into online capstone

courses, as both are HIPs (Kuh 2008, 2013; Kuh et al. 2017; O’Donnell 2013). They are

3

Shine and Brown: Transforming Criminal Justice Internships into Capstone Courses

Shine and Brown Transforming Internships into Capstone Courses 95

also similar in other regards (Durel 1993; National Leadership Council 2007). For

example, both internships and capstone courses build on students’ entire college

careers, culminating in experiences that allow students to apply knowledge in the

discipline and to personally reflect on ways to creatively solve real-world problems.

Applied internships and academic capstone courses foster similar skills,

including synthesizing the knowledge gained over collegiate careers and bridging the

gap between theory and practice (Parilla and Smith-Cunnien 1997; Steele 1993). A

critical distinction between the two, however, is the practical work experience that

students gain through internships when they are placed with an agency, department, or

court in the criminal justice field and are required to complete meaningful work that

contributes to the overarching mission or goals of the agency. Students gain experience

in professional settings and learn practical and professional skills. Students in capstone

courses, in contrast, must generally produce a product (e.g., report, project, paper,

portfolio) that synthesizes, integrates, and applies the knowledge they have acquired

over the course of their academic careers. Criminal justice capstone courses allow

students to use the totality of the knowledge they have gained in criminal justice

courses to critically evaluate and creatively engineer solutions to real criminal justice

problems (Kuh 2008; Schneider 2015). The challenge, then, for criminal justice faculty

and administrators during the COVID-19 crisis in March 2020 was to revise internships

in which students could not continue to work for agencies and to provide students with

similar experiences in an online capstone course. The most logical solution was to

create alternative assignments within the capstone course that adhered to the stated

course objectives.

After consulting with stakeholders at the department and school levels, faculty

decided to replace students’ outstanding internship hours with weekly position papers.

Topics were selected to expose students to critical issues and current events in

criminal justice. When possible, topics varied according to students’ internship

assignments, so the content covered pertained to a student’s initial placement. In

general, students intern in one of the three components of the system: policing, courts,

or corrections. Weekly topics were chosen based on critical issues within each of

these components and were assigned to students based on their original placements.

For example, one week’s topics included “Broken Windows Policing & Its

Effectiveness” for policing interns, “The Impact of Race on Sentencing Outcomes in

the U.S.” for students interning with courts, and “Risk & Needs Assessment—What,

Why, and How” for corrections-related internships.

Position papers were required to be data-driven, to reference a minimum of two

scholarly articles, and to be at least 600 words in length (excluding cover page and

references). The papers required students to synthesize empirical literature on the topics

and to integrate and apply what they learned to real-world issues. This problem-

centered inquiry is at the heart of preparing students to enter a complex and uncertain

world and aligns well with the requirements of HIPs (Schneider 2015). Instead of being

assigned readings, students researched their assigned topics independently via the

university’s journal subscription database to facilitate self-regulated learning, a skill

that both academics and practitioners regard as vital in the workforce (Boekaerts 1997;

4

Midwest Social Sciences Journal, Vol. 24 [2021], Iss. 1, Art. 9

https://scholar.valpo.edu/mssj/vol24/iss1/9

DOI: 10.22543/0796.241.1046

96 Midwest Social Sciences Journal Vol. 24 (2021)

Shine and Heath 2020). It is worth noting that the number of completed internship

hours at the time of the conversion for all students enrolled in the course were fairly

similar, so the requirements for the papers were the same for all students.

Given the pass/fail grading scheme of the course, position papers were graded

liberally. A grade of C– or better demonstrated competency in and/or understanding of

course material. In addition to competent writing, minimum expectations regarding

achievement of learning outcomes on the assignments included demonstration of basic

understanding of the assigned topics and relevant scholarly research. If students failed to

meet the minimum expectations, they received feedback on errors and omissions and on

where improvements could be made. Students were required to resubmit their papers

based on the feedback. Weekly papers were assigned on Monday morning and were due

by 5:00 p.m. the following Friday. The papers were graded, and students were provided

with extensive feedback by Tuesday of the following week. In this way, students could

access the feedback while the topic was still fresh in their minds and make revisions as

needed. The course met once a week for the first five weeks of the semester, covering

professionalism, how to write a resume and cover letter, ethics in criminal justice,

interviewing skills, and careers in the private sector. Because the five meetings concluded

before the pandemic was declared, there was no need to meet as a class once courses

were moved online.

To successfully complete an internship, each student was required to submit a

resume and cover letter to the career center on campus and to meet with a career center

counselor to review these documents. Students who had not completed this requirement

before the campus was closed because of COVID-19 were still required to submit their

materials online for review, make any revisions suggested by the reviewer, and resubmit

the updated versions for final approval. Once a career center staff member replied with

final approval, the student forwarded that email to the instructor and submitted the final

version of the resume and cover letter via Canvas (our university’s learning management

system). Students submitted their research papers (a separate and lengthier assignment

than the weekly papers) online as well. Each student participated in an exit interview at

the end of the course. These interviews are standard for the internship course and are

intended to give students the opportunity to share and reflect on their internship

experiences and to provide valuable insight and perspective to internship coordinators. As

part of the transition to online, the exit interviews were conducted virtually.

EFFECTIVENESS OF COURSE TRANSFORMATION FOR SPRING 2020

Our main concern in converting the internship course to an online capstone course mid-

semester was to ensure that students successfully learned the course objectives despite the

dramatic format change. Although limited, the data that we have demonstrates that

students successfully met the course objectives in spring 2020. These data, based on the

case study model, include student course evaluations, assessments of student learning,

and exit interviews with students.

A mean of eight students completes the internship each semester (fall and spring).

Each student completing the internship course is given the opportunity to provide a

5

Shine and Brown: Transforming Criminal Justice Internships into Capstone Courses

Shine and Brown Transforming Internships into Capstone Courses 97

course evaluation. Unfortunately, the percentage of students completing the course

evaluation is small. Despite the low response rates, the course evaluations for the

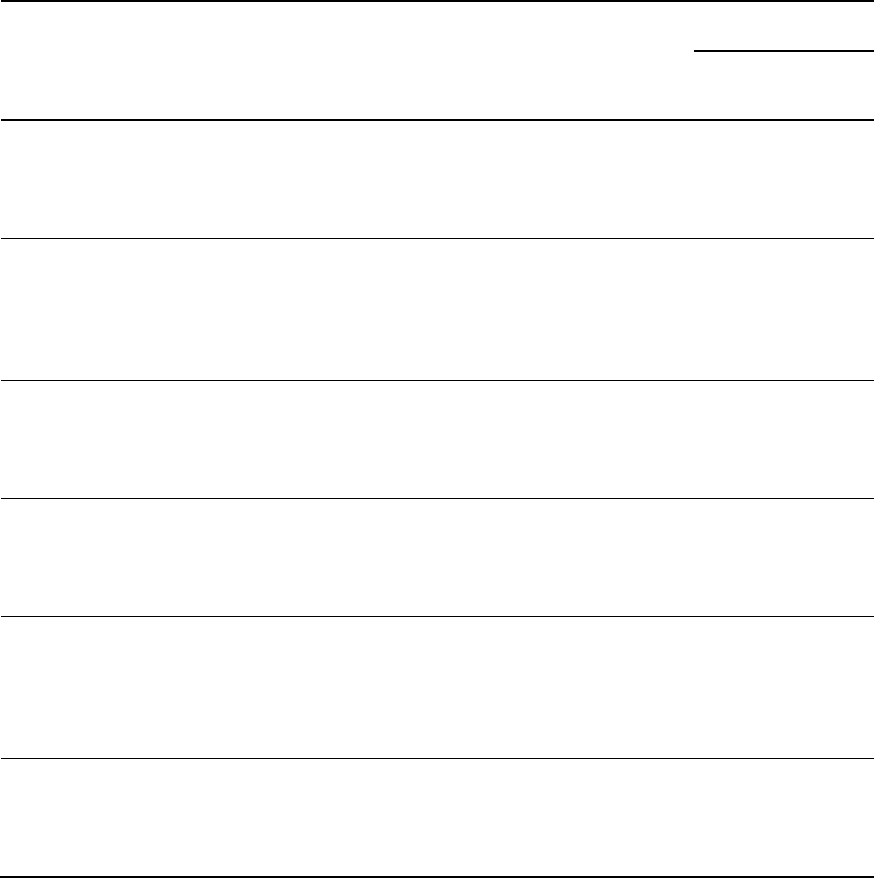

internship course from spring 2019 to spring 2021 are very positive. Table 1 shows the

mean scores of the course evaluation questions most relevant to student learning for

spring 2019 to spring 2021.

Table 1. Select Student Course Evaluation Results

Spring

2019

Summer

2019

Fall

2019

Spring

2020

Summer

2020

Fall

2020

Spring

2021

Spring

2021

Statements

J380

N = 4

(36.36%)

J380

N = 1

(16.67%)

J380

N = 3

(50.00%)

J380

N = 4

(30.77%)

J370

N = 5

(62.50%)

J380

N = 1

(25.00%)

J380

N = 2

(40.00%)

J490

N = 4

(40.00%)

Overall, I

would rate the

quality of this

course as

outstanding.

3.75 4.00 4.00 4.00 3.80 4.00 4.00 3.50

Announced

course

objectives

agree with

what is

taught.

3.75 4.00 4.00 4.00 3.80 4.00 4.00 4.00

The course

improved my

understanding

of concepts in

this field.

4.00 4.00 3.67 4.00 3.60 4.00 4.00 4.00

This course

increased my

interest in the

subject

matter.

4.00 4.00 3.67 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 3.50

Course

assignments

helped in

learning the

subject

matter.

3.75 4.00 4.00 4.00 3.80 4.00 4.00 3.75

My instructor

uses teaching

methods well

suited to the

course.

4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 3.80 4.00 4.00 3.00

The course evaluations for the internship course are provided for the three

semesters leading up to the “COVID semester” (spring 2020), when we converted the

6

Midwest Social Sciences Journal, Vol. 24 [2021], Iss. 1, Art. 9

https://scholar.valpo.edu/mssj/vol24/iss1/9

DOI: 10.22543/0796.241.1046

98 Midwest Social Sciences Journal Vol. 24 (2021)

internship into an online capstone course halfway through the semester, as are the mean

course evaluation scores for both the internship and online capstone courses for the three

semesters following the COVID semester. As can be seen in the table, there are no

significant differences in mean scores across the seven semesters.

Students were asked to indicate, on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly

agree), their level of agreement with the statements. High scores indicate positive course

evaluations, with scores above 3.0 indicating agreement with the statements and

demonstrating positive student evaluations of the course. Students in the internship

courses before spring 2020, in the internship course during spring 2020, and in both the

internship and capstone courses during spring 2020, fall 2020, and spring 2021 agreed or

strongly agreed that (1) the announced course objectives aligned with what was taught in

the course, (2) the course improved their understanding of concepts in the field, (3) the

course increased their interest in the subject matter, and (4) the teaching methods used by

the instructor were well suited to the course.

Very few responses were received to the qualitative questions (Which aspects of

the class were most valuable? Which aspects of the class were least valuable? What

could the instructor do to improve the course or his/her teaching effectiveness?) on the

student course evaluation. Furthermore, limitations to the responses were present. For

example, it was not possible to determine if the students who responded to the open-

ended questions at the end of the spring 2020 semester were students who had completed

their internship hours or those who had completed the course as a capstone course. Thus,

the responses from one student who wanted more meeting dates throughout the semester

and from another who thought “the class was well taught” are not helpful in determining

the effectiveness of the transition to online learning. Despite these limitations, it is

important to note that no students mentioned the transformation of the course from field

placements to online instruction as positive or negative; they did not mention the change

at all in the course evaluations.

Assessment of student learning is another measure of a successful transition from

internship placements to the online capstone experience. Of the course learning

objectives, the objective “apply concepts learned in the criminal justice program at IUK

to the work environment” best measures the effectiveness of our strategy for transforming

the course into an online capstone experience.

1

Assessments of student learning through

the position papers and the final research paper demonstrates that students were able to

successfully meet the internship course goal even though they completed the class as a

capstone. For example, seven students completed the position papers that were required

as part of the capstone. As part of the paper requirements, students were required to apply

theoretical concepts and empirical evidence to a contemporary problem in the criminal

justice system. All seven students successfully demonstrated achievement of these

learning goals in each of the four position papers. The students also completed a final

research paper whether they had completed the internship hours or the capstone. All

thirteen of the students completing the paper met or exceeded expectations on the

assessment by demonstrating knowledge of criminal justice concepts and their relevance

to the field. These assessments show that students achieved course goals despite the move

from field placements to a capstone experience.

7

Shine and Brown: Transforming Criminal Justice Internships into Capstone Courses

Shine and Brown Transforming Internships into Capstone Courses 99

A final measure of the success of the transformation from internship to capstone

experience comprises student responses and comments during the exit interview for the

course. Each student completing the course was required to meet with the instructor for

an exit interview. The purpose of the exit interviews is to gain a better understanding of

students’ activities and experiences with their internship providers. For students who

didn’t get the opportunity to complete their internships traditionally, questions about the

pivot to a capstone model were also asked, and although there was naturally a bit of

disappointment about not getting to complete their internships as planned, students

voiced support for the conversion, as well as appreciation for weekly paper topics related

to what they had been doing in their individual internships.

Although limited direct data exist to help us assess the effectiveness of our

approach in transitioning from in-person internships to an online equivalent experience,

the available evidence indicates that the revision of the course was successful.

Assessments of student learning, course evaluations, and informal exit interviews with

students all indicate that students successfully met the learning objectives of the course.

The evidence that our approach was successful encouraged us to continue with the online

capstone course for the summer and the following academic year as some students were

still unable to complete internships through spring 2021 because of COVID restrictions.

PREPARING FOR SUMMER AND BEYOND

In addition to making mid-semester changes to the internship course, criminal justice

faculty needed to determine how to manage summer internships. Students (including

those who were graduating in the summer) had already been enrolled in the full-semester

summer internship course when the national emergency was declared in the United

States. The university made the decision to continue with online rather than face-to-face

courses in the summer to comply with state mandates and to ensure the safety and well-

being of faculty, staff, and students. The criminal justice faculty decided that any changes

to the summer internship course should be easily and readily applicable to the following

academic year in case internships were not available to students because of continued

COVID-19–related restrictions. In fact, the capstone was not needed for fall semester, as

the only four students who needed to complete the capstone experience requirement for

the degree enrolled in the internship course rather than the capstone course. These

students were able to be placed in an agency to complete the internship. In spring 2021,

two students were able to find internship placements and four students enrolled in the

online capstone course.

Through collaboration between the instructor, the department head, and the dean

of the school, it was decided that the summer internship course should be replaced with a

capstone course. Several possible ways to offer this alternative experience to students

were considered. One possibility was to keep the internship course on the schedule, allow

students to register for the internship course, and then teach it as an online capstone. This

option was similar to what occurred in the spring but would apply to the full semester

rather than to only the last half of the semester. Another alternative was to offer a

capstone course, distinct from the internship course, and temporarily allow it to be

8

Midwest Social Sciences Journal, Vol. 24 [2021], Iss. 1, Art. 9

https://scholar.valpo.edu/mssj/vol24/iss1/9

DOI: 10.22543/0796.241.1046

100 Midwest Social Sciences Journal Vol. 24 (2021)

substituted for the internship degree requirement.

2

The former option was problematic

because the capstone course is not an actual internship. The department and school

administrators determined that it was not appropriate to have an internship listed on an

academic transcript when, in fact, the experience was not an internship. The latter option

was problematic because it required the full design (albeit built upon the work done in the

spring) of a course in less than two months. Ultimately, it was decided that the second

option, although clearly challenging, was the best option for the students, the program,

the university, and potential future employers; thus, the instructor of the internship course

designed a capstone course to be offered in the summer, and potentially in the fall, to

temporarily replace the internship requirement.

Once the summer capstone course was designed, only minor adjustments were

needed to account for the two-week difference in length between the summer and regular

academic semesters. The second iteration of the capstone course was developed and

eventually approved as a new course (J490) through remonstrance. There was not enough

time to gain approval for a new course through remonstrance in time for the summer

semester, however. As such, the summer capstone course was listed as a special topics

course for the summer semester using the upper-level special topics course number

(J370). Two criminal justice students were approved for in-agency internships in the

summer; thus, the instructor taught both the capstone course (as a topics course) and the

traditional internship course (J380) in the summer.

Decisions regarding the curriculum of the capstone course were also pressing. For

the course to be offered in the summer, the syllabus needed to be submitted for review in

April. Similar to the internship course, the capstone course required students to complete

resumes and cover letters reviewed by the career center. In addition, a 3000-word

research paper was assigned (a longer version of the 1500-word research paper required

for the internship course). Also consistent with the internship course, students were

required to attend five virtual classes. In addition to attending the required classes,

students completed an assignment related to the topics covered during each class. Finally,

students were assigned weekly position papers and were required to participate in weekly

online discussions.

The topics covered during the classes mirrored those covered in the internship

course classes, including how to dress and behave in the workplace, how to write a

resume and cover letter, ethics in criminal justice, the interview process and

interviewing tips, and careers in the private sector. To assist students with the unique

and individual time constraints posed by COVID-19, classes were held

asynchronously, with lessons posted on Monday mornings. Assignments associated

with each topic were created to ensure that students were completing and

understanding the virtual lessons. The assignments were due by 5:00 p.m. Friday of

the week that each related lesson was posted.

Weekly position papers were assigned to examine critical issues in criminal

justice. The requirements and grading scheme for the position papers were identical to

those listed for the spring semester conversion. Because the course was a traditional

criminal justice capstone course, however, topics covering every stage of the criminal

justice system were assigned, not just those associated with a student’s preferred career.

9

Shine and Brown: Transforming Criminal Justice Internships into Capstone Courses

Shine and Brown Transforming Internships into Capstone Courses 101

That said, many of the paper topics used in the spring semester conversion were utilized

for the capstone course as well.

Lastly, students were required to participate in weekly online discussions

covering key issues and current events in criminal justice. Examples of these issues

include Miranda rights and warnings, America’s response to the COVID-19

pandemic, and crime and the media. Students were provided links to supplemental

readings and videos and were instructed to answer the discussion questions and to

reply to at least one other student’s post per discussion. This gave students the

opportunity to learn with and from their peers while facilitating interpersonal

communication and engagement.

EFFECTIVENESS OF SUMMER AND FALL TRANSITION

TO CAPSTONE COURSES

As discussed earlier, the results from Table 1 demonstrate that, based on student course

evaluations, the transition from internship courses to capstone courses was effective for

the summer, fall, and spring semesters. Students in both the capstone and internship

courses agreed or strongly agreed that the course improved their understanding of

concepts in the field and increased their interest in the subject matter, and that the

instructor asked questions that challenged them to think and used teaching methods well

suited to the class. Although the mean response scores to the questions in the capstone

course were slightly lower than those in the internship (e.g., 3.75 and 4.0), the difference

is marginal. The responses were agree and strongly agree, and it is not possible to

determine how much more agreement strongly agree has than does agree or to determine

how students interpreted the distinction between the two. Agreement and strong

agreement are both indicators of a positive course experience; thus, the course

evaluations demonstrate similar student perceptions of both the internships and the online

capstone courses. Further, assessments of student learning in summer, fall, and spring

revealed that students effectively learned the stated course objectives in both the

internship and capstone courses.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 crisis created several challenges within academia as faculty were

required to abruptly move from face-to-face to online learning. Within this context,

internships presented even greater challenges as faculty struggled to provide students

removed from internships with online learning experiences that matched internships in

learning objectives and HIPs. The strategies we used to transform internships into online

capstone courses were successful. We hope that the presention of our experience in

developing and revising curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic and of the strategies

and lessons we’ve learned through this experience will enable others who are grappling

with the same issues to use our experiences to think through and develop improved

learning experiences for their criminal justice students. Further, we expect this case study

to engender discussion and encourage others to share their experiences to increase the

10

Midwest Social Sciences Journal, Vol. 24 [2021], Iss. 1, Art. 9

https://scholar.valpo.edu/mssj/vol24/iss1/9

DOI: 10.22543/0796.241.1046

102 Midwest Social Sciences Journal Vol. 24 (2021)

discipline’s overall understanding of effective teaching practices and to improve teaching

practices if future crises were to occur.

ENDNOTES

1. There were other course objectives; however, the other objectives were assessed prior

to the transition to online or as part of assignments that did not change (e.g., the

research paper) during the transformation of the mode of instruction. As such, the

learning objective noted above is the best assessment of student learning through the

transition to online.

2. The research practicum course was not offered during the summer for reasons

unrelated to COVID-19, and faculty and administrators agreed that criminal justice

students who wished to pursue careers, rather than graduate studies, upon graduation

should not be required to take a research practicum course that did not align with their

academic or career goals.

REFERENCES

Boekaerts, M. 1997. “Self-Regulated Learning: A New Concept Embraced by

Researchers, Policy Makers, Educators, Teachers, and Students.” Learning and

Instruction 7(2):161–86.

Callanan, G., and C. Benzing. 2004. “Assessing the Role of Internships in the Career-

Oriented Employment of Graduating College Students.” Education + Training

46(2):82–89.

Crain, A. 2016. “Exploring the Implications of Unpaid Internships.” NACE Journal.

Retrieved August 23, 2020 (https://www.naceweb.org/job-market/internships/

exploring-the-implications-of-unpaid-internships/).

Durel, Robert J. 1993. “The Capstone Course: A Rite of Passage.” Teaching Sociology

21(3):223–35.

Finley, A., and T. McNair. 2013. Assessing Underserved Students’ Engagement in

High-Impact Practices. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges

and Universities.

Knouse, S. B., J. R. Tanner, and E. W. Harris. 1999. “The Relation of College

Internships, College Performance, and Subsequent Job Opportunity.” Journal of

Employment Counseling 36:35–43.

Kuh, George D. 2008. High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has

Access to Them, and Why They Matter. Washington, DC: Association of

American Colleges and Universities.

Kuh, George D. 2013. “Taking HIPs to the Next Level.” In Ensuring Quality and Taking

High-Impact Practices to Scale, by G. D. Kuh and K. O’Donnell. Washington,

DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Kuh, George D., Ken O’Donnell, and Carol Geary Schneider. 2017. “HIPs at Ten.”

Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 49(5):8–16.

11

Shine and Brown: Transforming Criminal Justice Internships into Capstone Courses

Shine and Brown Transforming Internships into Capstone Courses 103

Lei, S. A., and D. Yin. 2019. “Evaluating Benefits and Drawbacks of Internships:

Perspectives of College Students.” College Student Journal 2:181–89.

Murphy, Dave, and Steve Gibbons. 2017. “Criminal Justice Internships: An Assessment

of the Benefits and Risks.” Retrieved September 22, 2020 (http://digitalcommons

.wou.edu/fac_pubs/39).

National Leadership Council for Liberal Education and America’s Promise. 2007.

College Learning for the New Global Century. Washington, DC: Association of

American Colleges and Universities.

O’Donnell, Ken. 2013. “Bringing HIPs to Scale.” In Ensuring Quality and Taking High-

Impact Practices to Scale, by G. D. Kuh and K. O’Donnell. Washington, DC:

Association of American Colleges and Universities.

O’Neill, N. 2010. “Internships as High-Impact Practice: Some Reflections on Quality.”

Peer Review 12(4):4–8.

Parilla, P., and S. Smith-Cunnien. 1997. “Criminal Justice Internships: Integrating the

Academic with the Experiential.” Journal of Criminal Justice Education

8(2):225–41.

Schneider, Carol Geary. 2015. “The LEAP Challenge: Transforming for Students,

Essential for Liberal Education.” Liberal Education 101(1/2):10–18.

Shine, Beau, and Sara E. Heath. 2020. “Techniques for Fostering Self-Regulated

Learning via Learning Management Systems in On-Campus and Online

Courses.” Journal of Teaching and Learning with Technology 9(1). Retrieved

(https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/jotlt/article/view/29014)

Steele, J. 1993. “The Laden Cart: The Senior Capstone Course.” Teaching Sociology

21(3):242–45.

Taylor, M. S. 1988. “Effects of College Internships on Individual Participants.” Journal

of Applied Psychology 73(3):393–401.

Times Higher Education. N.d. “The Impact of Coronavirus on Higher Education.”

Retrieved August 23, 2020 (https://www.timeshighereducation.com/hub/

keystone-academic-solutions/p/impact-coronavirus-higher-education#).

12

Midwest Social Sciences Journal, Vol. 24 [2021], Iss. 1, Art. 9

https://scholar.valpo.edu/mssj/vol24/iss1/9

DOI: 10.22543/0796.241.1046