Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for

Children at Risk Children at Risk

Volume 2

Issue 2

Teen Pregnancy

Article 8

2011

Does Immediate Access to Birth Control Help Prevent Pregnancy? Does Immediate Access to Birth Control Help Prevent Pregnancy?

A Comparison of Onsite Provision Versus Off Campus Referral for A Comparison of Onsite Provision Versus Off Campus Referral for

Contraception at Two School-Based Clinics Contraception at Two School-Based Clinics

Peggy Smith

Baylor College of Medicine

Gabrielle Novello

Mariam R. Chacko

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Smith, Peggy; Novello, Gabrielle; and Chacko, Mariam R. (2011) "Does Immediate Access to Birth Control

Help Prevent Pregnancy? A Comparison of Onsite Provision Versus Off Campus Referral for

Contraception at Two School-Based Clinics,"

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for

Children at Risk

: Vol. 2: Iss. 2, Article 8.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58464/2155-5834.1043

Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol2/iss2/8

The Journal of Applied Research on Children is brought

to you for free and open access by CHILDREN AT RISK at

DigitalCommons@The Texas Medical Center. It has a "cc

by-nc-nd" Creative Commons license" (Attribution Non-

Commercial No Derivatives) For more information, please

contact [email protected].tmc.edu

Does Immediate Access to Birth Control Help Prevent Pregnancy? A Comparison Does Immediate Access to Birth Control Help Prevent Pregnancy? A Comparison

of Onsite Provision Versus Off Campus Referral for Contraception at Two School-of Onsite Provision Versus Off Campus Referral for Contraception at Two School-

Based Clinics Based Clinics

Acknowledgements Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments: This article was supported in part by a grant from St. Luke’s Episcopal Health

Charities, the Simmons Foundation and Maternal Child Health Bureau/Leadership Education in

Adolescent Health Grant - 2 T71 MC00011

This article is available in Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk:

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol2/iss2/8

Introduction

Unplanned teen pregnancy and parenting continue to be issues

throughout the United States. In 2010, the national birth rate was 39.1 per

1,000 women aged 15-19.

1

The teen birth rate in Texas is particularly high

at 63.4 per 1,000, the third highest rate in the country. In Houston and

Harris County, Texas, teen birth rates of of 85 to 116 per thousand in

some zip codes are higher than the Texas rate in most areas, and in many

places in Houston and Harris County, teen birth rates are greater than 100

per 1,000 females.

2

High birth rates are indicative of even higher

pregnancy rates, as not all pregnancies are carried to term. In fact, Texas

has the fourth highest teen pregnancy rate in the nation at 101 per 1,000

teens ages 15-19, versus the national rate of 84 per 1,000.

3

This rate is

projected to increase by 13% by the year 2015, resulting in a projected

rate of 127 per 1,000.

4

Furthermore, the city of Houston has a high rate of

repeat pregnancies. In 2008, Houston had a repeat pregnancy rate of

23%, compared with other major cities in the U.S., which ranged from 12%

to 28%.

5

Minority groups, in particular blacks and Hispanics, are

disproportionately at-risk for teen pregnancy. Hispanics have the highest

teen birth rates in the country, followed by black teens. It is estimated that

52% of Hispanic girls and 50% of black girls under 20 years of age will

become pregnant, as opposed to 19% of non-Hispanic white girls.

6,7

For

teenage girls aged 15-19 in 2006, the birth rate among Hispanics was 83

per 1,000 and 64 per 1,000 among blacks, compared with 27 per 1,000

among non-Hispanic whites.

8

In Houston, this disparity is particularly

pronounced. Texas Department of State Health Services reported that in

2003, 66% of all teen births were to Hispanic mothers and 23% were to

black mothers, while 11% were to white mothers.

9

The costs associated with teen childbearing are significant and

could potentially impact a school’s approach to teen pregnancy. Not only

does teen childbearing negatively affect mother and child, there are

significant consequences for the nation, states and districts. A 2008

analysis by The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned

Pregnancy indicated teen childbearing cost U.S. taxpayers at least $10.9

billion each year, with the majority of costs incurred because of births to

teens 17 years and younger.

10

The public sector costs of teen childbearing

include lost tax revenues because of lower earnings from teen parents,

higher costs of public assistance to families with teen parents, and higher

costs of child welfare and health care for children born to teen mothers.

Furthermore, with approximately only 40% of teen mothers graduating

from high school, school districts with high teen pregnancy rates have a

1

Smith et al.: School-Based Birth Control Policy Comparison

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

significantly increased risk of losing average daily attendance funding, as

well as enrollment funding.

11

A number of strategies have been employed with the goal of

reducing teenage pregnancy, with many taking place within schools.

Approximately 95% of all youth aged 5-17 was enrolled in school in 2008,

making the school system an ideal avenue through which to provide

pregnancy risk-reduction strategies.

12

The developmental period during

which students are in school is also conducive to introduction of

pregnancy prevention interventions, with the majority of students in school

at pre-sexual initiation or just post-sexual initiation phase. Educational

interventions, including abstinence-only, abstinence-plus and

comprehensive sex education curricula, have had some success in

helping to prevent teen pregnancy.

13

For students at high risk for teen

pregnancy, however, education curricula are not always enough. High-risk

youth tend to fall in lower socioeconomic groups and often do not have

regular access to primary and reproductive healthcare facilities.

Government funded and non-profit school-based health centers have

been established to provide these students with increased access to

reproductive health services in order to help them avoid unintended

pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV. However, there

is often variation among these clinics in the services provided. For

example, many school-based clinics prohibit the dispensing of hormonal

birth control on-site.

Evidence shows that when hormonal birth control is not dispensed

on-site, teenage family planning clients take longer to come in to the clinic

for follow-up visits, are less likely to choose a birth control method during

their first or second visit and to select a consistent birth control method

over time.

14

-16

Ultimately, the delay or complete lack of access to

hormonal birth control on site at school-based clinics may have

deleterious effects on reproductive health outcomes among teens.

Zimmer-Gembeck, Doyle and Daniels

14

found that female teens who

visited school-based family planning clinics that initiated an on-site

dispensing policy were significantly more likely to select a contraceptive

method when compared to teens who visited the clinic before the on-site

dispensing policy was instituted. In addition, clients were more likely to

return for additional family planning visits after the on-site policy was

established. Sidebottom, Birnbaum and Stoddard

15

found that under a

voucher system for hormonal contraceptives in Minneapolis school-based

clinics, only 41% of students received all requested contraceptives. In

comparison, after a policy change to dispense hormonal contraceptives

on-site, 99% of students received all requested contraceptives. Ethier et

2

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 2 [2011], Iss. 2, Art. 8

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol2/iss2/8

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1043

al.

16

found that female students who had access to a school-based health

center were more likely to have received pregnancy and disease-

prevention care, used hormonal contraception and emergency

contraception at last sexual encounter than female students who were

unable to access a school-based health center.

A limitation of existing studies is a lack of information on the overall

effects of these different dispensing policies on reproductive health

outcomes. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to compare the impact of

different policies for access to hormonal contraceptives among low-

income teens at two comparable school-based clinics. Specifically, the

objective of this exploratory comparison was to determine whether or not

receipt of hormonal contraception on site at a school-based clinic affected

subsequent pregnancy rates among student patients.

Methods

Program Description

The school-based adolescent clinics are under the aegis of an academic

medical institution and operate in collaboration with a metropolitan

independent school district. The primary health care model used at two

school clinics is comprehensive, focuses on both teenage girls and boys

and incorporates elements of prevention, intervention and education

through meaningful collaboration with school and other community

partners. The clinics’ primary goal is to provide access to preventive

health care services to uninsured students through delivery of on-site

medical, gynecological, nutritional, and mental health services. Written

parental consent is obtained at initial entry into the clinic and preferably at

the beginning of the academic year. As part of this goal, the clinics attempt

to reduce pregnancy rates through standardized screening for sexual

activity and risk of pregnancy at every clinic visit. Brief contraceptive

counseling for teens who engage in sexual activity is also provided. The

clinic in one school (School A) has been in existence since 2005. The

contraceptive dispensing policy at School A’s clinic is on site, where those

seeking birth control can receive free and confidential contraceptive

services (including hormonal contraception using the same-day or Quick

Start method, emergency contraception and condoms) at the clinic

(supported by Title X funding). The other school clinic (School B) has been

in existence since 2007 and uses a referral policy, by which students

cannot receive hormonal contraception, emergency contraception or

condoms on the school campus and must travel to another affiliated teen

clinic to receive free hormonal contraception. However, Well Woman

examinations are conducted, and STI testing and treatment is provided.

3

Smith et al.: School-Based Birth Control Policy Comparison

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

The contraceptive service policy was determined by the principal of each

school based on political and personal factors.

Participants

The schools are located in comparable inner city urban

neighborhoods. The majority of students was of Hispanic ethnicity and had

no private health insurance coverage. The number of students enrolled in

School A in 2008-2009 was 1928 and in 2009-2010 1891; School B in

2008-2009 was 2606 and in 2009-2010 was 2763. The number of

unduplicated visits made by students to the School A clinic in 2008-2009

was 988 and in 2009-2010 was 980. Visits to the School B clinic in 2008-

2009 were 988 and in 2009-2010, 1253. Over 80% of students who

attend both school clinics participate in the federal free and reduced lunch

program, an indicator of low-income status.

Data Collection

Using a retrospective chart review and an electronic database

review (AHLERS Integrated System), patients seen in both clinics from

9/2008-12/2009 for primary care and reproductive health symptoms were

reviewed. Charts of all female patients seen during this time period were

reviewed by a research assistant. Charts of sexually active females were

identified and the following data was extracted: demographic data, history

of prior pregnancy, record of providing birth control counseling, the

outcome of the counseling; documentation of interest in seeking hormonal

contraception; evidence of a return visit and dispensing of hormonal

contraception in school clinic A; and a referral appointment to an affiliated

teen clinic off campus and evidence of appointment kept and hormonal

contraception dispensed in school clinic B. Whenever possible, the nurse

practitioner at clinic B and who worked at more than one clinic site

referred students to herself at the referral clinic site. Outcome measures

included positive pregnancy test results at any point during or after birth

control use. The authors made the assumption that since these students

had sought services at the school clinic, they would likely utilize their

school clinic or the referral clinic to seek pregnancy testing. The clinics

were known for their ability to provide confidential pregnancy testing and

facilitate prenatal care for pregnant girls. Patients were tracked via the

electronic database system through 3/31/2010.The data collected was

second checked by the authors. Human Subjects approval was obtained

from the institution to review medical records and electronic data (Protocol

#H26846).

4

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 2 [2011], Iss. 2, Art. 8

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol2/iss2/8

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1043

Data Analysis

Data were entered in IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0. Data analysis

included calculation of mean age, frequency of students with a prior

history of pregnancy, appointments kept, hormonal contraception started ,

mean duration of follow up period, positive pregnancy tests. The duration

of the observation period for a participant in each setting was determined

as the time between the first visit, when contraceptive counseling was

conducted, through 3/31/2010. An independent t-test was used to

compare the mean duration of the observation period between School

clinics A and B. Fisher’s Exact Test was used to compare the

appointment-keeping rate and the type of hormonal contraceptive method

dispensed between school clinics A and B, In addition Fisher’s Exact Test

was used to compare the overall pregnancy rates and the association

between a prior history of pregnancy and pregnancy rates.

Results

School A clinic: As seen in Table 1 (see Appendix), of 79 students who

requested hormonal contraception the mean age was 17.5 years (range

15 to 22 years); 68% >

18 years, 77% were Hispanic, and 21% (16/79)

reported prior pregnancy. As seen in Table 2, all 79 students (100%)

returned for onsite hormonal contraception (65% pill and 35% long acting

progestin injection by appointment within one week. The mean duration of

the observation period for participants in this setting was 13 months

(range 4-19 months).

School B clinic: As seen in Table 1, of the 40 students who

requested and were referred for hormonal contraception, the mean age

was 17.5 years (range 14 to 20 years); 52% were >

18 years, 88% were

Hispanic, and 7.5% reported prior pregnancy. As seen in Table 2, only

50% (20/40) kept their appointment for hormonal contraception. The time

taken to follow up for these appointments ranged from the same day to

126 days (mean 7.25 days); 75% (15/20) were seen within 7 days and

85% (17/20) were seen within 14 days. The remaining three students took

39 to 126 days to keep their appointment. Pills were dispensed to 85%

(17/20) and 15% (3/20) received long acting progestin injection. The mean

duration of the observation period for participants in this setting was 11.9

months (range 4-19 months).

A significantly higher frequency of students kept their appointments

for hormonal contraception at School A clinic as compared to School B

clinic (p <0.05). The difference between the mean duration of the

observation period and type of birth control used (pills versus long acting

progestin injection) between School clinics A and B was not statistically

5

Smith et al.: School-Based Birth Control Policy Comparison

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

significant. Combining the data of both schools, the overall pregnancy rate

for students in both clinics was 10.9% (13/119). There was no statistically

significant difference between the mean age of students who did and did

not have a documented positive pregnancy test (18. 0 vs. 17.5 years). As

seen in Table 2, the pregnancy rate was significantly higher at the school

that referred its students for contraception compared to the school with

onsite services (p< 0.05). The pregnancy rate was also significantly higher

for students without a prior history of pregnancy in the school with a

referral policy for contraception (21.6%) versus the school with onsite

contraceptive services (4.7%) (p< 0.05).

Discussion

This study was a preliminary attempt to evaluate outcomes of differing

policies regarding the provision of hormonal birth control at school-based

health clinics. The main findings were: (1) the follow up appointment rate

for hormonal contraception among students who sought birth control at a

school clinic was significantly higher at the school clinic with onsite

contraceptive services compared to the school clinic with a referral policy

for contraception. In addition, at the school clinic with a referral policy of

those who kept their appointments, the majority (85%) were able to keep

their appointment within 14 days; (2) the school clinic with a referral policy

for contraception had a significantly higher pregnancy rate than the school

clinic with on-site contraceptive services and; (3) the pregnancy rate was

also significantly higher for students without a prior history of pregnancy in

the school with a referral policy for contraception compared to the school

with onsite contraceptive services.

The first finding in this study helps to strengthen other published

studies that found the provision of on-site access to birth control was more

likely to promote birth control use.

14-16

It also appears that at least half the

students are able to follow through with appointments when a successful

referral mechanism is in place. However, it is concerning that almost half

of the students were unable to follow through, despite indicating their

interest in seeking hormonal contraception. In this context, it is likely that

these students had difficulty accessing the offsite services that were

offered for multiple reasons. We can speculate that the challenges

included difficulty with arranging appointments to initiate and obtain refills

for hormonal contraception, lack of transportation and inability to seek

confidential services on one’s own after school.

The difference in pregnancy rates between the two schools was

significant and highlights the potential for easy access to affordable

reproductive services and a wide range of contraceptive services in a

6

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 2 [2011], Iss. 2, Art. 8

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol2/iss2/8

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1043

school clinic to positively affect health outcomes among high-risk

populations. Reduced compliance with oral contraceptive pills (as

compared to injectable long acting progestin) may have negatively

affected the pregnancy rates at both school clinics. This is supported by

data that demonstrate higher compliance rates and lower pregnancies

rates with injectable long acting progestin involving same day or Quick

Start method as compared to oral contraceptive pill use.

17

In addition, the

availability of condoms and emergency contraception or method switching

may have lowered the pregnancy rate at the school with onsite hormonal

contraceptive services. Finally, pregnant girls may have dropped out of

both schools and use of other medications interfering with oral

contraceptive pills may have affected rates in both locations.

Unfortunately, these data are not retrievable.

A prior history of pregnancy appeared to encourage seeking of

hormonal contraception and thus affected the outcome measure at both

school clinics. This finding suggests that these teen and young adult

mothers were motivated to prevent further pregnancies and wanted to

graduate from high school.

18

In contrast, the pregnancy rate was

significantly higher for students without a prior history of pregnancy in the

school with a referral policy for contraception compared to the school with

onsite contraceptive services. Improving access to hormonal

contraception for sexually active high school females without a prior

history of pregnancy who are motivated to prevent unintended pregnancy

is important. Our research supports the need for a greater focus by

communities on prevention of unintended pregnancy among high school

students with no prior history of pregnancy. Evidence exists that school

enrollment functions as a protective factor in the reduction of risk

behaviors. This is especially true for high school settings in which sexual

risk-taking related to unintended pregnancy has significant consequences

for the completion of secondary education and the matriculation to

colleges and universities.

19

However, college aspirations may not be

protective against initiation of sexual activity in neighborhoods with a high

concentration of poverty.

20

It would be logical that school-based clinics

collaborate with high schools that predominantly enroll students from low

income neighborhoods to address this adolescent health issue.

The provision of comprehensive adolescent-focused health care,

components of on-site medical services should include medical services,

case management and social support, and accessibility and convenience

to enhance the possibility that adolescents will obtain and use prescriptive

and long acting methods of hormonal contraception (LARC) to prevent

unintended pregnancy. The convenience of on-site service is especially

7

Smith et al.: School-Based Birth Control Policy Comparison

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

important for time-sensitive emergency contraception. This preventive

method, by being available to students, maximizes pregnancy prevention

services for teens who otherwise would not have access to a private

physician or are under 18 years of age and could not receive the method

without a prescription.

In fact, individual school policy as well as school district policy

appears to be a major factor determining the prohibition of on-site

contraceptive dispensing among school-based health centers across the

country, as 30% and 74% of prohibitions were determined by these

factors, respectively.

21,22

One may wonder if those in the educational field

and parents are either unwilling or unable to see the consequences of

unintended pregnancy on the educational attainment of their students.

The low number of students seeking hormonal contraceptive

services over a 12-month period is striking, especially at the school clinic

with onsite contraceptive services. Several factors may be at play here.

Per school district policy. all adolescents who received services at both

school clinics must have a signed parental consent. Because students

know this, it may be a barrier to seeking confidential contraceptive

services (even prior to an initial clinic visit) by all students, including those

who have parental permission and those unwilling or unable to obtain

parental permission. In addition, the school clinic with a referral policy for

contraception had been in existence for two years at the time of this study

and may not have been familiar to many students and parents. Some

students could have also had private providers or gone to other health

facilities such as a federally qualified health center.

Limitations

The major limitations of this study are the retrospective chart review

method for data collection, the small sample size in the school with a

referral policy for contraception and the limited number of variables

extracted for data analysis. The small sample size also precluded

multivariable analysis to control for confounding variables. In addition,

important variables such as condom use and emergency contraception

were not tracked during the study period. Finally, cultural values

surrounding pregnancy at younger ages among certain minority immigrant

populations are shown to affect pregnancy rates and were not controlled

for in the statistical analysis.

6,7

However, the schools were comparable in

terms of ethnicity.

8

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 2 [2011], Iss. 2, Art. 8

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol2/iss2/8

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1043

Recommendations

Health professionals and community leaders may need to accept the

additional responsibility of informing the public school community of the

value of providing reproductive health care services on campus to at-risk

adolescents at the high school level. While historically schools have been

seen as the source of added value services to students who receive

education under their purview, broad endorsement of providing medical

care as well is not universal. One strategy to advance this concept is to

redefine health care from the point of view of access. Therefore, a

potential strategy for advocating for comprehensive school-based clinics

can be embedded in the concept of the medical home. The medical home

model implemented in a teen clinic or family planning clinic setting can be

an efficient way to deliver both well and sick child care for communities

with large numbers of uninsured youth.

23

Creating a medical home within

a school venue can be an efficient way not only to initiate and complete

series of vaccinations, for instance, but also to involve parents through the

consenting process required for the care of minors. Using the medical

home model can also provide a forum for the detection and treatment of

sexually transmitted infections, the prevention and screening of HIV, and

the prevention of unintended pregnancy through contraceptive dispensing

and counseling in this at-risk group. Therefore, the authors recommend

the collaboration between schools and teen-focused clinics to create a

medical home for high-risk teens. Recently enacted national legislation

has yet to be interpreted as to whether or not such recommendations can

be practically actualized on a broad scale.

Conclusions

This was a preliminary attempt to evaluate outcomes of differing policies

regarding the provision of hormonal birth control at school-based health

clinics to students seeking hormonal contraception. Results indicate that

the school clinic with a referral policy for contraception had a significantly

higher pregnancy rate than the school clinic with on-site contraceptive

services. Further study with a larger sample size is necessary. This study

has implications for reproductive health policy, especially as directed

toward high-risk teenage populations.

9

Smith et al.: School-Based Birth Control Policy Comparison

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

References

1. Child Trends. Facts at a glance: A fact sheet reporting national,

state, and city trends in teen childbearing. Publication 2011-10.

2011.

2. Texas Department of State Health Services, Bureau of Vital

Statistics, 2008. Harris County Teen Birth Rates (Instant Atlas):

Accessed August 16, 2011. http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/tprc/tprc-

default-inner.aspx?id=10662

3. Guttmacher Institute. US Teenage Pregnancies, Births and

Abortions: National and State Trends and Trends by Race and

Ethnicity. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/USTPtrends.pdf.

Accessed July 12, 2011.

4. Sayegh MA, Castrucci BC, Lewis K, Hobbs-Lopez A. Teen

pregnancy in Texas: 2005 to 2015. Matern Child Health J.

2010;14:94-101.

5. Child Trends. Percentage of all teen births that are repeat births,

and number of births to mothers under 20, in large cities*, 2008.

National Center for Health Statistics, 2008. Natality Special

Research File. 2011.

6. National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. Teen Pregnancy

and Childbearing among Latino Teens.

http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/pdf/FastFacts_TPC

hildbearing_Latinos.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2011.

7. National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. Teen Pregnancy

and Childbearing among Black Teens.

http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/pdf/FastFacts_TPC

hildbearing_Blacks.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2011.

8. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for

2006. National Vital Statistics Reports, 57(7). Hyattsville, MD:

National Center for Health Statistics; 2009.

9. City of Houston. The state of health in Houston/Harris County.

http://www.houstontx.gov/health/HoustonHealth/StateOfHealth2007

.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed September 9, 2010.

10. National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. Counting it up: The

Public Cost of Teen Childbearing. Available at:

http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/costs/default.aspx. Published

2011. Accessed July 12, 2011.

11. Hoffman, S.D. (2006). By the numbers: the public costs of teen

childbearing. National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy:

Washington, DC.

10

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 2 [2011], Iss. 2, Art. 8

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol2/iss2/8

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1043

http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/costs/pdf/report/1-

BTN_Front_Matter.pdf. Accessed September 9, 2010.

12. US Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, Current Population

Survey (CPS), October Supplement, 1970–2008.

http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/2010/section1/table-ope-1.asp.

Accessed September 9, 2010.

13. Kirby D. The impact of schools and school programs upon

adolescent sexual behavior. J Sex Res. 2002;39(1):27-33.

14. Zimmer-Gembeck, MJ, Doyle L, Daniels JA. Contraceptive

dispensing and selection in school-based health centers. J Adolesc

Health. 2001;29:177-185.

15. Sidebottom A, Birnbaum AS, Nafstad SS. Decreasing barriers for

teens: evaluation of a new teenage pregnancy prevention strategy

in school-based clinics. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1890-1892.

16. Ethier KA, Dittus, PJ, DeRosa CJ et al. School-based health center

access, reproductive health care, and contraceptive use among

sexually experienced high school students. J Adolesc Health.

2011;48:562-565.

17. Rickert VI, Tiezzi L, Lipshutz J, et al. Depo Now: Preventing

unintended pregnancies among adolescents and young adults. J

Adolesc Health. 2007;40:22-28.

18. Kern SEU, Pullmann MD, Walker SC, et al. Adolescent use of

school-based health centers and high school dropout. Arch Pediatr

Adolesc Med. 2011;165: 617-623.

19. Hoffert, SL, Reid L, Mott FL, The Effects of Early Childbearing on

Schooling over time.Fam Plann Perspect. 2001; 33:259-67.

20. Cubbin C, Brindis CD, Jain S, Santelli J, Braverman P.

Neighborhood poverty, aspirations and expectations, and initiation

of sex. J Adolesc Health; 2010;47;399-406.

21. The Guttmacher Report on Public Policy. School - Based Health

Centers and the Birth Control Debate- Special Analysis. October

2000. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/pdf. Accessed July 12,

2011.

22. Santelli JS, Nystrom RJ, Brindis C, et al. Reproductive health in

school-based health centers: findings from the 1998-99 census of

school-based health centers. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32:443-451.

23. Schaffer SJ, Fontanesi J, Rickert D, et al. How effectively can

health care settings beyond the traditional medical home provide

vaccines to adolescents? Pediatrics, 2008;121(Supp 1):S35-S45.

11

Smith et al.: School-Based Birth Control Policy Comparison

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

Appendix

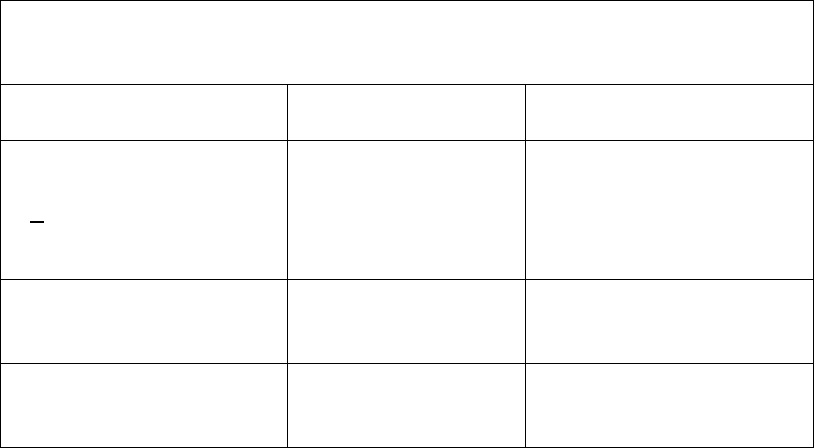

Table 1. Characteristics of Students Seeking Hormonal

Contraception

September 2008 – December 2009 at two school clinics

Characteristics

School

A

clinic

(N=79)

School

B

clinic

(N=40)

Age:

(years)

Mean(range)

> 18 years (%)

17.5 (15-22)

53 (68)

17.5 (14- 20)

21 (52)

Race/Ethnicity:

Hispanic (%)

60 (77)

35 (88)

Prior Pregnancy (%) 16 (21.9)

[95% C.I. 12% -

30%]

3 (7.5)

[95% C.I. 1% -20%]

12

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 2 [2011], Iss. 2, Art. 8

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol2/iss2/8

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1043

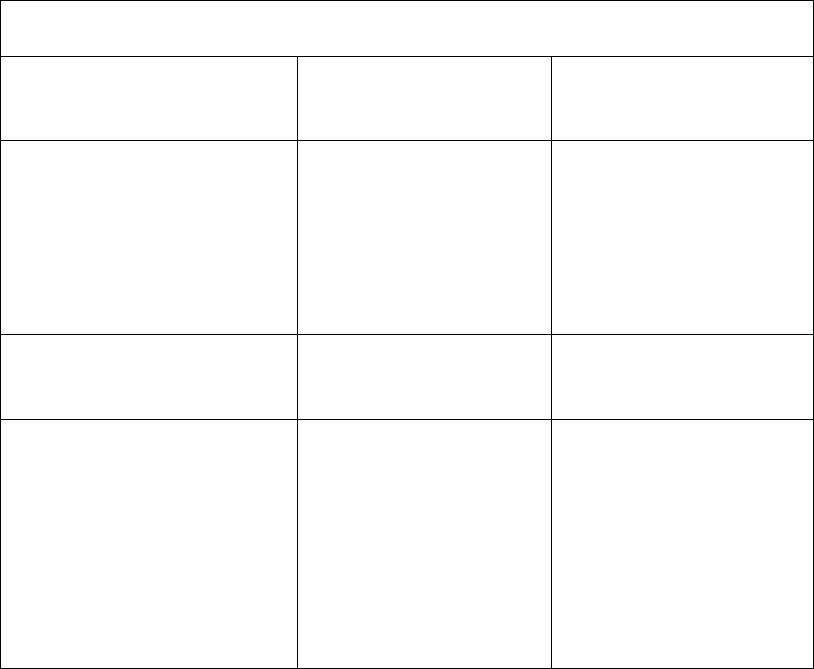

Table 2.

Comparison between two school clinics for

Appointments

Rates, Method Type and Pregnancy Rates

School

A

clinic

(N=79)

(%)

School

B

clinic

(N=40)

(%)

Contraception

Appointment

Observation period

Mean/(range)

months

79 (100)

13.3(4-19)

20 (50)*

11.9(4-19)

Method

received

Oral Contraceptive Pill

Long acting

progestin

51 (65)

28 (35)

17 (85)

3 (15)

Pregnancy rate

No prior history of

Pregnancy

Received

contraception

5 (6 )

[95% C.I. 2% -14%]

4 (4.7)

[95% C.I. 0.9% -13%]

5 (6) [95% C.I. 2% -

14%]

8 (20)*

[95% C.I. 9% -35%]

8 (21.6 )*

[95% C.I. 9% -38%]

3 (15) [95% C.I. 3% -

37%]

*p<0.05

13

Smith et al.: School-Based Birth Control Policy Comparison

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011