e Journal of Undergraduate Research

Volume 12 Journal of Undergraduate Research,

Volume 12: 2014

Article 2

2014

A Lile Goes a Long Way: Pressure for College

Students to Succeed

Jennifer R. Davis

South Dakota State University

Follow this and additional works at: h9p://openprairie.sdstate.edu/jur

Part of the Educational Psychology Commons

8is Article is brought to you for free and open access by Open P7IRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information

Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in 8e Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized administrator of Open P7IRIE: Open Public

Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact michael.biondo@sdstate.edu.

Recommended Citation

Davis, Jennifer R. (2014) "A Li9le Goes a Long Way: Pressure for College Students to Succeed," !e Journal of Undergraduate Research:

Vol. 12, Article 2.

Available at: h9p://openprairie.sdstate.edu/jur/vol12/iss1/2

PRESSURE ON COLLEGE STUDENTS 1

A Little Goes a Long Way: Pressure for College

Students to Succeed

Author: Jennifer R. Davis

Faculty Sponsor: Tyler M. Miller, Ph. D.

Department: Psychology

ABSTRACT

When college students begin college they experience pressure from multiple sources. For

example, they experience pressure from their parents to succeed, from their professors, and

pressure from themselves to do well in classes. This pressure could lead to high anxiety and

possibly even poor performance in classes. Prior research that has examined the impact of

anxiety on performance includes the Yerkes-Dodson law and the Processing Efficiency

Theory. Both argue that anxiety increases the performance to a point, but then performance

decreases again with too much pressure. The Processing Efficiency Theory also includes

motivation. This motivation increases the drive to succeed and perform at a higher level. In

the current study I manipulated the pressure participants felt as they completed a memory

test to examine pressure as an influence on memory performance. Furthermore, I also

analyzed how trait-anxiety interacts with pressure (as measured by the State Trait Anxiety

Inventory). College students (n = 67) were separated into either a no pressure condition or a

pressure condition and completed a memory test. Results showed a trend for participants

with low trait-anxiety to have increased memory performance in the pressure condition.

These results follow the Processing Efficiency Theory and the Yerkes-Dodson law. In other

words, perhaps participants had better memory in the pressure condition because they were

motivated to do well. Future research identifying the optimal amount of pressure for the

best performance is suggested.

Keywords: anxiety, pressure, memory, processing-efficiency theory, performance.

PRESSURE ON COLLEGE STUDENTS 2

INTRODUCTION

College students experience pressure in school every day by their parents, professors and

even from themselves to succeed in their classes. That pressure may lead to anxiety.

Anxiety is the most common mental illness in the United States, with the onset occurring

most often between the ages of 18 and 22 years old (Andrews & Wilding, 2004). Anxiety is

especially high amongst college freshman (Vye & Welch, 2007). For college students,

pressure from peers to socialize, parents to succeed in school, and an internal drive to

succeed, along with being in a new environment, could lead to high anxiety and poor

performance in classes (Cassady and Johnson, 2002). Research that has examined the

effects of anxiety on performance has used the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger,

1983). This standardized assessment splits anxiety into state-anxiety and trait-anxiety.

State-anxiety is feelings of nervousness that can be attributed to the present situation. Trait-

anxiety is feelings of nervousness that can be attributed to a person’s personality

characteristics (Spielberger, 1983).

According to Eysenck (2013), performance is based on one’s level of state-anxiety. The

STAI contains a total of 40 items, 20 items to measure state-anxiety and 20 items to

measure trait-anxiety. A typical item to measure state-anxiety is “I feel nervous and

restless,” and the participant answers on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost

never) to 4 (almost always). The STAI has a Cronbach alpha coefficient of .90

(Spielberger, 1983). State-anxiety could be brought on by experience of pressure such as

the type of pressure college students experience to do well in classes. This type of anxiety

could be associated with the autonomic nervous system response to stress, also known as

the “fight or flight” response (Viljoen, Claassen & Mare, 2013).

Furthermore, Sarason (1984) states that participants who feel anxiety also experience

cognitive interference in the form of preoccupying and concerning ideas, known as “task-

irrelevant thoughts.” For example, these intrusive thoughts take cognitive resources away

from the task and the participant is left with fewer available cognitive resources to

complete the task. Conversely, those who report lower anxiety levels have fewer “task-

irrelevant thoughts” (Derakshan & Eysenck, 2009). A concept known as stereotype threat

could explain why people have these thoughts. Stereotype threat is when someone has a

PRESSURE ON COLLEGE STUDENTS 3

negative belief about themselves and they are worried that they will confirm this negative

stereotype about themselves or their own group (Steele & Aronson, 1995). In other words,

if participants begin an experiment thinking that they are going to fail, they are more likely

to perform poorly (Chung, B. G., Ehrhart, M. G., Ehrhart, K. H., Hattrup, K. & Solamon,

J., 2005). The negative stereotypes that participants have of themselves are the task-

irrelevant thoughts.

The Yerkes-Dodson law (1908) has been used to examine the relationship between anxiety

and performance. In concordance with the Yerkes-Dodson law, an individual’s

performance levels will follow a standard bell curve in relation to the amount of pressure

applied. Therefore, performance on a difficult task is low with slight amount of pressure,

high with an intermediate amount of pressure, and low with a high amount of pressure. The

results of Yerkes’ and Dodson’s experiment showed that there was an optimal amount of

pressure that increased performance in rats (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). The results found by

Yerkes and Dodson that lead to the development of the Yerkes-Dodson law have been

examined and replicated many times over the past century (Diamond, 2005; Dodson, 1915;

Salehi, Cordero & Sandi, 2010). However, the Yerkes-Dodson law does not include a

motivational element, where the drive to succeed effects performance level. The processing

efficiency theory (PET), which does include a motivational element, could help explain

why participants perform better under medium pressure conditions. The processing

efficiency theory states that the more pressure a participant experiences, the more effort the

participant will exert to perform well up to an optimal amount of pressure (Eysenck and

Calvo, 1992).

Since the Yerkes-Dodson law states that performance levels follow a bell curve pattern as

the level of stress increases than an excessive amount of stress leads to performance

detriments. The idea that performance decreases with pressure has been illustrated and

replicated many times. For example, a study by Horikawa and Yagi (2012) identified 59

college soccer players that had high or low anxiety group based on their responses on the

STAI. Next, they had them take penalty kicks while their coach pressured them to shoot

better or did not give any instruction. The results indicated that both high and low anxiety

groups’ performance deteriorated under pressure.

PRESSURE ON COLLEGE STUDENTS 4

In contrast, a study by Walkenhorst and Crowe (2009) showed that a little pressure can

actually increase performance. They tested 60 participants that were either high or low

anxiety groups based on their STAI responses. They then randomly assigned each

participant to a high or low worry group. The high worry condition participants were

instructed to sit for fifteen minutes and worry about any topic of their choice and then take

a visual patterns test, whereas the low worry group just took the memory test. Results found

that low trait-anxiety participants performed best when they were in the high worry

condition. This pattern of results is noteworthy because it does not fit with the Yerkes-

Dodson law that participants’ performance on a task decreases with pressure. Furthermore,

participants in the high worry condition would have had task-irrelevant thoughts, which

then would have taken away cognitive resources from doing well on the task (Sarason,

1984; Derakshan & Eysenck, 2009). However, the Processing Efficiency Theory could

explain this pattern of data because it argues that the participant’s motivation to succeed

would increase with some pressure resulting in improved performance (Eysenck & Calvo,

1992).

The purpose of this study is to examine whether manipulated pressure on college students

will affect their memory performance on a cued-recall test. I hypothesized that overall,

participants with high trait-anxiety will have worse memory performance compared to

participants with low trait-anxiety. Furthermore, I hypothesized that pressure will

negatively affect all participant memory performance, with pressure having the most

deleterious effects for participants with high trait-anxiety.

METHOD

There was 67 participants selected from the South Dakota State University Psychology

Department research participation pool (50 female, M age = 18.76). This experiment used a

2 Condition (no pressure and pressure) x 2 Anxiety (high trait-anxiety and low trait-

anxiety) between subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) design. Participants were

randomly assigned to Condition and completed the trait portion of the State Trait Anxiety

Inventory (Spielberger, 1983). Based on participants’ responses, I created a low trait-

anxiety group and a high trait-anxiety group using a median split. I selected the memory

PRESSURE ON COLLEGE STUDENTS 5

test items from a norming study completed by Grimaldi, Pyc and Rawson (2010) based on

the probability they were recalled during Trial 1 of the norming study. The average

probability of recall on trial one was .23, but items from the entire range were selected (.04-

.49 probability of recall).

PROCEDURE

Participants were first given an information sheet about the study and agreed to participate.

Immediately after agreeing to participate, all participants completed the trait portion of the

State Trait Anxiety (STAI). After completing the trait-anxiety portion of the STAI,

participants in the no pressure condition heard, “You are about to study some easy word

pairs, try to the best of your abilities.” Participants in the pressure condition heard, “You

are about to study some very difficult word pairs and your performance on the memory test

will be indicative of your other abilities such as performance in classes, overall GPA, and

expected earnings in the workplace.” The participants were then shown 40 Lithuanian-

English word pairs each for 10 seconds (e.g., durys-door) using Superlab (Cedrus, 2013).

After participants viewed all 40 word pairs they began the memory test in which they were

given a sheet of paper with all 40 Lithuanian words and were asked to provide the English

equivalent (e.g., durys - ). Participants attempted to recall the word pairs for 6 minutes.

Finally participants were asked to complete a series of demographic questions. In the

debriefing, participants were informed that the purpose of the study was to find out whether

manipulated pressure on college students affected their memory performance.

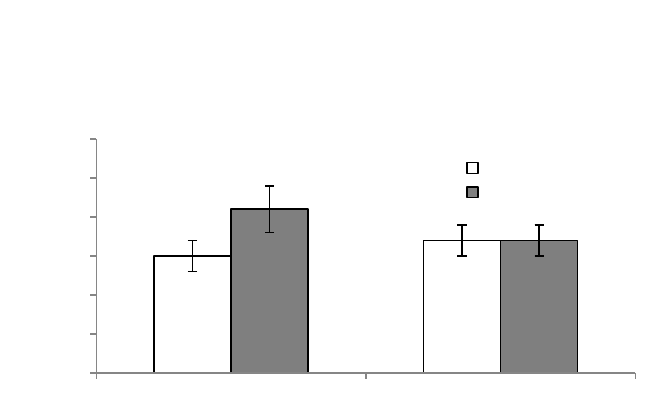

RESULTS

I conducted a 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Condition (no pressure and

pressure) and Anxiety (high trait-anxiety or low trait-anxiety) as the between subjects

independent variables and memory performance as the dependent variable. The results

revealed that there was no main effect of the Condition, F(1,63) = 1.82, MSE =0.01, p

=0.18, η

2

p

= 0.03. In other words, participant memory performance in the no pressure

condition (M = 0.16, SE = 0.02) was no different than participant memory performance in

the pressure condition (M = 0.19, SE = 0.02). Similarly, participant memory performance in

PRESSURE ON COLLEGE STUDENTS 6

the low trait-anxiety group (M = 0.18, SE = 0.02) was no different than participant memory

performance in the high trait-anxiety group (M = 0.17, SE = 0.01; F(1,63) = 0.31, MSE =

0.01, p = 0.58, η ²

p

= 0.01. Finally, there was no interaction between the pressure condition

and trait-anxiety, F(1, 63) = 1.44, MSE = 0.01, p = 0.23, η ²

p

= 0.02. Students who have

high trait-anxiety were no more likely to perform well on a memory test than students with

low trait-anxiety, regardless of condition (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The percent correct on the memory test, comparing trait-anxiety and pressure

condition. The error bars depict standard error

DISCUSSION

The goal of this research was to determine whether manipulating pressure on participants

would affect their performance on a memory test. The high trait-anxiety participants had

similar memory performance regardless of the pressure condition. The expectation was that

the memory performance would be higher in the low pressure group; however there was a

slight indication that pressure improved memory performance for people with low trait-

anxiety. As such, it is possible that those with low trait-anxiety needed some pressure to be

motivated to perform at a higher level, which follows the Processing Efficiency Theory and

Yerkes-Dodson law in that the optimal amount of pressure results in increased

performance. If this law was valid for pressure on students in college in real classroom

settings, then one could infer that some pressure would be better than no pressure.

Some potential limitations of this experiment include external validity and the anxiety

measurement. Putting pressure on an individual in a controlled environment is much

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

Low Trait Anxiety High Trait Anxiety

Proportion Correct

No Pressure

Pressure

PRESSURE ON COLLEGE STUDENTS 7

different than applying real life pressure, such as a parent or a professor in a natural

situation, thus reducing external validity. Additionally, the state portion of the State Trait

Anxiety Inventory was not used in this experiment. Future research in this area should use

the state portion of the assessment to check if the pressure manipulations are effective at

increasing state anxiety. It is possible that participants in the current experiment were not

anxious for various reasons including that they were not listening to the instructions that

were intended to cause the anxiety or that participants were not affected by the low severity

of the pressure. Another check of state-anxiety could have been participant’s subjective

reports, but no reports were collected. For example, I could have asked participants how

they perceived the pressure put on them.

Participant’s trait-anxiety level in the current sample was low, which may have skewed the

results. The State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, 1983) ranges in scores from 20 to

80, so the mean should be 50, but in this sample both the mean and median were 37, which

is much lower than the ideal mean. Increasing sample size to have a more representative

sample would allow one to make better conclusions about how pressure and anxiety

interact to influence memory performance.

Although some studies concerning anxiety focus on physiological responses to stress or

pressure, this study focused on the cognitive effects of anxiety. Cognitive effects of

anxiety, including task-irrelevant thoughts, affect college students and have deleterious

effects on memory performance and performance on other tasks (Derakshan & Eysenck,

2009). In this study the task-irrelevant thoughts could have been focused on the fact that

results of the memory test were “indicative of performance in classes, overall GPA, and

expected earnings in the workplace.” Although the results were not statistically significant

there was a trend that high pressure led to increased performance on the memory test. This

could be explained by the Processing Efficiency Theory (PET), stating that the more

pressure a participant experiences, the more effort the participant has to exert to perform

well.

Although people may be tempted to decrease anxiety, my results and results from previous

research (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908; Eysenck and Calvo, 1992) suggest that there is an

PRESSURE ON COLLEGE STUDENTS 8

optimal amount of anxiety, stress or pressure for performance on a given task, including

memory. Future research should identify optimal amount of pressure to increase

performance on a variety of tasks in more naturalist settings such as the college classroom.

REFERENCES

Andrews, B. and Wilding, J. M. (2004), The relation of depression and anxiety to life-stress

and achievement in students. British Journal of Psychology, 9, 509–521.

doi: 10.1348/0007126042369802

Cassady, J. C. and Johnson, R. E. (2002). Cognitive Test Anxiety and Academic

Performance. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27, 270-295.

doi: 10.1006/ceps.2001.1094

Cedrus Corporation. (2013). SuperLab (version 4.0) [software]. Available from

http://www.superlab.com

Chung, B. G., Ehrhart, M. G., Ehrhart, K. H., Hattrup, K. & Solamon, J. (2005). A new

vision of stereotype threat: Testing its effects in a field setting. Academy of

Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, 1-6.

doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2005.18778670

Derakshan, N. & Eysenck, M. W. (2009). Anxiety, processing efficiency, and cognitive

performance: New developments from attentional control theory. European

Psychologist, 14(2), 168-176. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040. 14.2.168

Diamond, D. M. (2005). Cognitive, endocrine and mechanistic perspectives on non-linear

relationships between arousal and brain function. Nonlinearity in Biology,

Toxicology and Medicine, 3, 1-7. doi: 10.2201/nonlin.003.01.001

Dodson, J. D. (1915). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation in

the kitten. Journal of Animal Behavior, 5(4), 330-336. doi: 10.1037/h0073415

PRESSURE ON COLLEGE STUDENTS 9

Eysenck, M. W. (2013). The impact of anxiety on cognitive performance. In S. Kreitler

(Ed.) Cognition and motivations: Forging an interdisciplinary perspective (pp.

96-108). New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press.

Eysenck, M. W. & Calvo, M. G. (1992). Anxiety and performance: The processing

efficiency theory. Cognition and Emotion, 6, 409-434.

Gago, D. & Martins, R. M. (2013). Effects of pleasant visual stimulation on attention,

working memory, and anxiety in college students. Psychology & Neuroscience,

6(3), 351-355. doi: 10.3922/j.psns.2013.3.12

Grimaldi, P. J., Pyc, M. A. & Rawson, K. A. (2010). Normative multitrial recall

performance, metacognitive judgments, and retrieval latencies for Lithuanian-

English paired associates. Behavior Research Methods, 42(3), 634-642

Horikawa, M. & Yagi, A. (2012). The relationships among trait anxiety, state anxiety and

the goal performance of penalty shoot-out by university soccer players. Plos

ONE, 7(4). doi:10.1371.journal.pone. 0035727

Salehi, B., Cordero, M. I., Sandi, C. (2010). Learning under stress: The inverted-U-shape

function revisited. Learning and memory, 17, 522-530. doi: 10.1101/lm.1914110

Sarason, I. (1984). Stress, Anxiety, and Cognitive Interference: Reactions to Tests. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 929-938.

Spielberger C.D. (1983) Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Mind

Garden, Menlo Park, CA

Steele, C. M. & Aronson, J. A. (2004). Stereotype threat does not live by Steele and

Aronson (1995) Alone. American Psychologist, 59(1), 47-48. doi: 10.1037/0003-

066X.59.1.47