University of Windsor University of Windsor

Scholarship at UWindsor Scholarship at UWindsor

Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers

1-1-2022

“The Vehicle Was a Hockey Game”: A Holistic Approach to Aging “The Vehicle Was a Hockey Game”: A Holistic Approach to Aging

for Older Men for Older Men

Ryan Tomaselli

University of Windsor

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd

Part of the Kinesiology Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Tomaselli, Ryan, "“The Vehicle Was a Hockey Game”: A Holistic Approach to Aging for Older Men" (2022).

Electronic Theses and Dissertations

. 8732.

https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/8732

This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor

students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only,

in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution,

Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder

(original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would

require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or

thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email

(scholarship@uwindsor.ca) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208.

!

“THE VEHICLE WAS A HOCKEY GAME”: A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO AGING

FOR OLDER MEN

by

Ryan Tomaselli

A Thesis

Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies

through the Department of Kinesiology

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for

the Degree of Master of Human Kinetics

at the University of Windsor

Windsor, Ontario, Canada

2022

© 2022 Ryan Tomaselli

“THE VEHICLE WAS A HOCKEY GAME”: A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO AGING

FOR OLDER MEN

by

Ryan Tomaselli

APPROVED BY:

_____________________________________________________

C.J. Greig

Faculty of Education

_____________________________________________________

C.G. Greenham

Department of Kinesiology

_____________________________________________________

P.M. van Wyk, Advisor

Department of Kinesiology

January 25

th

, 2022

!

iii!

DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY

I hereby certify that I am the sole author of this thesis and that no part of this thesis

has been published or submitted for publication.

I certify that, to the best of my knowledge, my thesis does not infringe upon

anyone’s copyright nor violate any proprietary rights and that any ideas, techniques,

quotations, or any other material from the work of other people included in my thesis,

published or otherwise, are fully acknowledged in accordance with the standard

referencing practices. Furthermore, to the extent that I have included copyrighted material

that surpasses the bounds of fair dealing within the meaning of the Canada Copyright Act,

I certify that I have obtained a written permission from the copyright owner(s) to include

such material(s) in my thesis and have included copies of such copyright clearances to my

appendix.

I declare that this is a true copy of my thesis, including any final revisions, as

approved by my thesis committee and the Graduate Studies office, and that this thesis has

not been submitted for a higher degree to any other University or Institution.

!

iv!

ABSTRACT

The many benefits of physical activity are well established. Nonetheless, there remains a

need for qualitative research on aging and sports focused on the normalization of sport

for older adults, and the increased opportunity for sport participation in older age. Aging

and sport research, which has primarily focussed on older elite athletes, has found older

adults value health-related benefits, social interaction, and resistance of the aging process

through sport participation. However, research examining a broader scope of specific

sport participation, such as hockey, in older age may provide a distinguished

understanding of participation tied to meaning and lifestyle factors. Therefore, the

primary objectives of this study were to understand 1) how participating in hockey in

later life influences the aging experience, and 2) meaning and motivation for hockey

participation in older age. Semi-structured interviews were administrated to 10 Canadian

men aged 50 years or older who continued to participate in hockey. Through thematic

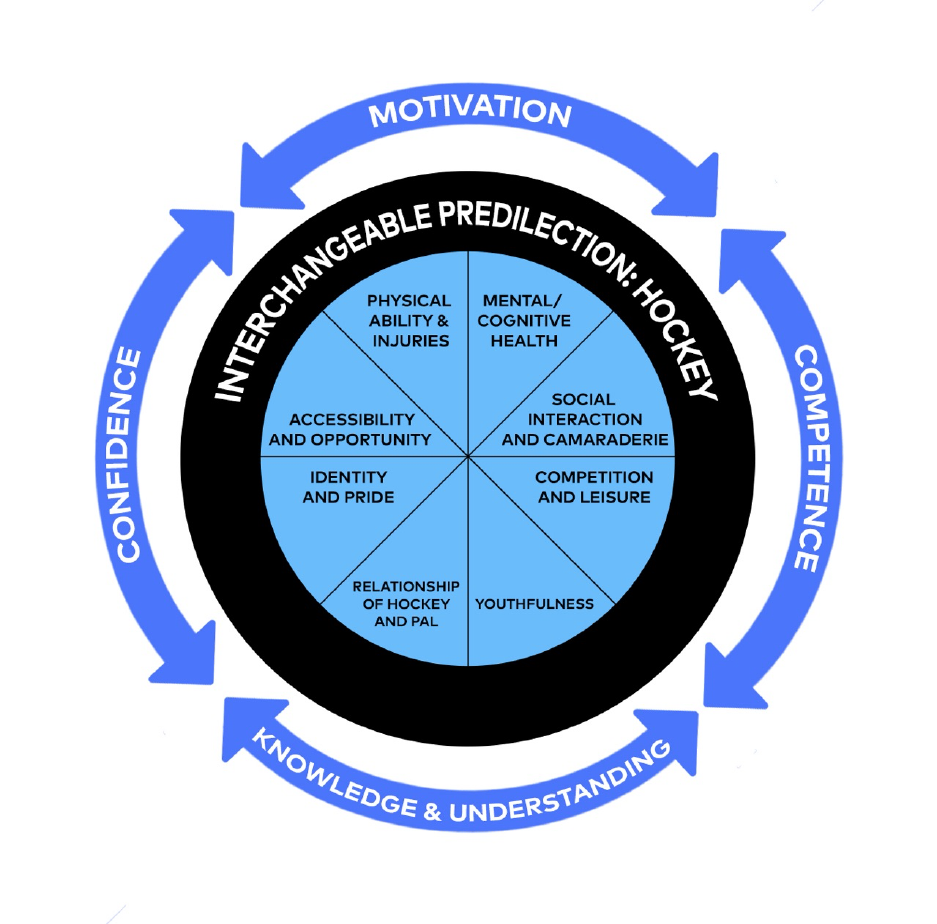

analysis of the interviews, eight themes were identified: 1) physical ability and injuries,

2) social interaction and camaraderie, 3) relationship of hockey and PAL, 4) competition

and leisure, 5) youthfulness, 6) identity and pride, 7) accessibility and opportunity, and

8) mental/cognitive health. Through the interpretation of the results, an Active Aging

Wheel of Engagement approach was presented. Overall, hockey was more than a mere

physical activity, it was a multi-faceted contributor to many aspects of these older men’s

lives as it fulfilled several of their self-perceived motivations and desires. The

participants conceptualized hockey as an all-encompassing approach to successful aging,

perceiving the sport as a healthy and integral physically active leisure in their lives, rather

than a risky and dangerous endeavor in later life.

!

v!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project would not be possible without a great deal of dedication and effort from

others. I would like to thank the following for their contributions.

Dr. Paula van Wyk – for your commitment, perseverance, and guidance. You always

seemed to have the answer I was searching for or the clarity I needed in the hardest times.

You always brought out the confidence in myself and knew humour was often the best

approach. I cannot praise your work ethic and talent as a researcher enough, but the

friendship we developed is the greatest takeaway from my experience. You were the one

who encouraged me to take this step in my life, and for that, I am forever grateful.

Drs. Christopher Greig and Craig Greenham - for your exquisite knowledge,

enthusiasm, and perspectives in the great game of hockey. Your fandom and extensive

backgrounds in hockey have been invaluable contributions to this project. Keep your

sticks on the ice!

Dr. Sean Horton – for your consistent interest and encouragement throughout the

development of this project. You have been an ever-present staple during my time as

graduate student. I am extremely fortunate to have had your wisdom and support since

day one.

Family and Friends – Thank you for always being there throughout this journey and

providing comfort and company during what has been some of the craziest years ever.

Special thanks to the participants who volunteered to share their experiences. I greatly

appreciated you taking time out of your day as well as listening to your stories. I may

need to use all of your valuable advice one day on the ice.

!

vi!

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY .............................................................................. iii

ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................v

LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. ix

LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................x

LIST OF APPENDICES .................................................................................................... xi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................... xii

NOMENCALATURE ...................................................................................................... xiii

RESEARCH ARTICLE .......................................................................................................1

1.0 Introduction ....................................................................................................................1

1.1 Purpose Statement ................................................................................................... 11

1.2 Research Questions ................................................................................................. 11

1.2.1 Central Question .............................................................................................. 11

1.2.2 Sub-Questions .................................................................................................. 11

2.0 Methodology ................................................................................................................13

2.1 Qualitative Approach .............................................................................................. 13

2.2 The Researcher’s Role ............................................................................................ 17

2.3 Participants .............................................................................................................. 18

2.4 Data Collection Procedures ..................................................................................... 20

2.5 Data Analysis .......................................................................................................... 24

2.6 Data Interpretation .................................................................................................. 26

3.0 Results ..........................................................................................................................28

3.1 The Wellness Wheel Concept ................................................................................. 30

3.2 Physical Ability and Injuries ................................................................................... 34

!

vii!

3.3 Social Interaction and Camaraderie ........................................................................ 39

3.4 Competition and Leisure ......................................................................................... 48

3.5 Youthfulness ........................................................................................................... 56

3.6 Identity and Pride .................................................................................................... 61

3.7 Accessibility and Opportunity ................................................................................ 65

4.0 Discussion ....................................................................................................................72

5.0 Literature Review .........................................................................................................89

5.1 Older Adults and Physical Activity ........................................................................ 89

5.1.1 Aging Populations ............................................................................................ 89

5.1.2 Aging and Physical Activity ............................................................................ 94

5.1.3 Aging and Sport ............................................................................................... 97

5.1.4 Opinions, Perspectives, and Experiences of Older Adults on Physical Activity

Pursuits .................................................................................................................... 102

5.1.5 The Motivation and Meaning for Sport Participation and Physical Activity

Engagement in Later Life ....................................................................................... 104

5.1.6 Addressing Heterogeneity: The Future of Physically Active Leisure for Older

Adults ...................................................................................................................... 111

5.1.7 Physical Literacy and Older Adults ............................................................... 117

5.2 Ice Hockey ............................................................................................................ 121

5.2.1 The History and Identity of Ice Hockey in Canada ....................................... 121

5.2.2 Recreational Ice Hockey ................................................................................ 127

5.2.3 Health Implications of Ice Hockey ................................................................ 130

References ........................................................................................................................136

Appendices .......................................................................................................................162

Appendix A – Semi-Structured Interview Guide ........................................................ 162

Appendix B – Demographic Questionnaire ................................................................ 164

Appendix C – Relationship of Hockey and PAL ........................................................ 166

!

viii!

Appendix D – Mental/Cognitive Health ..................................................................... 172

Appendix E – Additional information related to themes that emerged ...................... 180

Hockey Identity – the Canadian aspect: a secondary facet ..................................... 180

Hockey is dangerous and risky: a myth or misunderstanding? ............................... 182

Vita Auctoris ....................................................................................................................187

!

ix!

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Participant Demographics………………………………………………….

29

!

x!

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Active Aging Wheel of Engagement…………………………………….

32

!

xi!

LIST OF APPENDICES

Appendix A: Semi-Structured Interview Guide

Appendix B: Demographic Questionnaire

Appendix C: Relationship of Hockey and PAL

Appendix D: Mental/Cognitive Health

Appendix E: Additional information related to themes that emerged

!

xii!

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ACSM: American College of Sports Medicine

BMI: Body Mass Index

CAPL: Canadian Association of Physical Literacy

CARHA: Canadian Adult Recreational Hockey Association

CBC: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

COVID-19: Coronavirus

EU: European Union

HRmax: Maximum Heart Rate

IPLA: International Physical Literacy Association

MET: Metabolic Equivalent

NHL: National Hockey League

PA: Physical Activity

PAL: Physically Active Leisure

PL: Physical Literacy

WFCU: Windsor Family Credit Union

WHO: World Health Organization

WMG: World Masters Games

WWII: Second World War

!

xiii!

NOMENCALATURE

Active Aging: Used to describe individual or collective strategies for optimizing health,

social participation, and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age,

particularity conceptualized as policies or programs.

Anaerobic Physical Activity: Brief intense bursts of exercise, such as sprinting, where

oxygen demand surpasses oxygen supply.

Baby Boom: Increases in birth rate across a specific period of time (i.e., 1946-1965).

Body Mass Index (BMI): A term to indicate a predicted measurement of body fat using

two other factors: Weight (kg) / Height (m)

2

.

Exercise: Structured physical activity that requires effort to perform and is completed

with the purpose of improving physical fitness and overall health.

Ice Hockey: A fast contact sport played on an ice surface, generally between two teams

of six skaters, who attempt to drive a small rubber disk (puck) into the opposing net.

Light-Intensity Physical Activity: Any physical activity that is performed between 1.5-

to-3 METs and does not result in substantial increase in heart or breathing. For example,

slow walking and bathing.

Leisure: How one chooses to spend their free time. Leisure activities may be active (e.g.,

golf, fishing) or passive (e.g., reading, meditating).

Masters Sport: Individual or team competition for older adults, in which participants

compete against others (or themselves) within the same age range.

Middle-aged Adult: Although age categories can be widely debated, a middle-aged adult

typically falls within the range of 45-to-64 years. For the purposes of this study, middle-

aged adult will incorporate an individual who is 50-to-64 years of age.

!

xiv!

Metabolic equivalent (MET): A physiological measure expressing the intensity of

physical activities. One MET is the energy equivalent expended by an individual while

seated at rest.

Moderate-Intensity Physical Activity: Any physical activity that is performed between

3-to-6 METs. On a scale relative to an individual’s personal capacity, moderate-intensity

is usually a 5 or 6 on a scale of 0-to-10.

Quantitative data: The value of data in the form of counts and numbers, and is

independent from opinions, feelings, or interpretations.

Older Adult: For the purposes of the study, an older adult is defined as any individual 65

years of age or older.

Physical Activity: Any bodily movement that entails energy expenditure. Examples

include sport, exercise, and labour work.

Physical Literacy: A lifecourse approach to assess and promote physical activity,

defined by the International Physical Literacy Association (2017) as, “the motivation,

confidence, physical competence, knowledge, and understanding to value and take

responsibility for engagement in physical activities for life”.

Physical Activity Leisure (PAL): The collection of behaviours related to physical

activity that individuals engage in during their free time, including physical activity,

exercise, sport, and active leisure pursuits.

Population Aging: The increasing percentage of older adults within a population.

Recreational Ice Hockey: Formal or informal ice hockey, generally similar to the

professional game in terms of play and rules with some exceptions, but (for the purposes

of this study) is reserved for older individuals or players that have surpassed their allotted

!

xv!

time in organized ice hockey. Formal recreational hockey can be considered organized

adult leagues and tournaments that have timed games, set teams, and track scores and

statistics. Informal recreational hockey would be considered games played for ‘fun’ and

have fluid participation, also often regarded as ‘pick up’ hockey.

Sport: Activities performed within a set of rules and undertaken as part of leisure or

competition. Examples include track and field, golf, and ice hockey.

Qualitative Data: Non-numerical data that approximates and characterizes through

observations and recordings. Often derived from individual’s opinions and perspectives

of their own experiences.

Vigorous/High-Intensity Physical Activity: Any physical activity that is performed at

6.1 METS or greater. On a scale relative to an individual’s personal capacity, vigorous-

intensity is usually a 7 or 8 on a scale of 0-to-10.

!

1!

RESEARCH ARTICLE

1.0 Introduction

The world has been experiencing seeing an extraordinary shift towards an aging

population as almost every country is experiencing growth among the older segment of

their populace (United Nations, 2019). In the year 2019, one for every 11 people in the

world were aged 65 years and older, representing 9 per cent of the global population

(United Nations, 2019). Similar to global trends, projections estimate that older adult

(i.e., aged 65 years and older) Canadians will increase from 17.2 percent of the national

population in the year 2018, to as high as 23.4 percent and 29.5 percent in the years 2030

and 2068, respectively (Statistics Canada, 2019a). Two notable facts: older adult

Canadians outnumber children aged 0 – 14 years; and, the number of centenarians

(person aged 100 years and older) has surpassed 10,000 nationwide (Fitzpatrick, 2019;

Statistics Canada, 2018). The synergistic influence of key contributors is responsible for

this recent population aging, including such factors as lower fertility rates, increase in

longevity, impact of major historical events (i.e., Baby Boom), and international

migration (United Nations, 2015). Thus, the wide range of ramifications as a result of

population aging will require strategies for adapting and understanding the anticipated

changes related to economics, politics, sociality, and healthcare (Guarino, 2018; United

Nations, 2019).

Accompanied by the trend of global population aging, the average life expectancy

at birth in the world has increased, rising to 72.6 years in the year 2019 and projected to

reach 77.1 years in the year 2050 (United Nations, 2019). However, the increased

longevity of life calls to question whether quality of life is sacrificed for greater quantity

!

2!

of life as the majority of gains in life expectancy will be spent living with four or more

chronic conditions (e.g., cancer, hypertension, depression) and declining functional health

(Kingston et al., 2018; Statistics Canada, 2015a). Specifically, the difference in life

expectancy at birth and health-adjusted life expectancy at birth (expected years living in

good health) is approximately 10.5 years for Canadians, thus, emphasizing the challenge

of prolonging healthy life years (Statistics Canada, 2015a). Subsequently, there will be a

requirement for significant adjustments to negotiate with greater demands for healthcare

resources, social support systems, and income supplementation for the older portion of

the population (Parkinson et al., 2015), such as strategies encouraging behavioural

changes in relation to lifestyle choices (Peel et al., 2005). One behaviour in particular is

engaging in physical activity.

Engaging in physical activity can provide a multitude of benefits for older adults,

including prevention of chronic disease (Chodozko-Zajko et al., 2009; Warburton et al.,

2006), maintenance of physical and cognitive functioning (Chodozko-Zajko et al., 2009;

Gajewski & Falkenstein, 2016), psychosocial well-being (Chodozko-Zajko et al., 2009;

Gayman et al., 2017b), and higher rated quality of life (Acree et al., 2006; Figueria et al.,

2012). Physical activity engagement among older adults has the added benefit of

reducing expenses on healthcare resources (Azagba & Sharaf, 2014). However, older

adults remain the most inactive cohort (Azagba & Sharaf, 2014; Colley et al., 2011).

Although a reported 98 percent of the older population understand the health benefits of

physical activity, there is discrepancy between action and knowledge (Ory et al., 2003).

For example, approximately only 12 percent of older Canadians meet the Canadian

Physical Activity Guideline of 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (in

!

3!

10-minute periods/bouts) per week (Statistics Canada 2015b). Thus, the majority of this

population are exposed to the negative health outcomes of physical inactivity and

sedentary behaviour (Cunningham et al., 2020). Nonetheless, the prevalence and

promotion of sport participation for older adults has been argued as one of many possible

appropriate and cost-efficient options to improve physical activity involvement for older

adults (Dionigi, 2017).

In recent decades, sport participation in later life has been an emerging trend,

coinciding with the increased popularity of Masters Sport competition (e.g., older elite

athletes competing against others within the same age range) in particular (Gard et al.,

2017; Grant, 2001). Although older adults’ sport participation frequency and knowledge

of health-related benefits of physical activity has improved, there is also a change in

appropriateness and perceptions about sport and physical activity involvement in later life

(Gard et al., 2017). For example, stereotypes of aging are primarily negative in nature,

framing older adults as unhealthy, dependent, frail, and poorly functioning mentally and

physically members of the population (Dionigi, 2015; Shepherd & Brochu, 2020). Thus,

the ability to participate in sport and valuing of competition in later life has enabled older

adults as agents that challenge normalized ideas of aging, contributing to the evolving

and heterogeneous landscape of older adults (Dionigi, 2006b; Dionigi, 2015; Dionigi &

O’Flynn, 2007). However, the prevalence of Masters athletes and normalization of sport

participation has the potential to marginalize individuals who do not participate in this

new ‘doing’ of aging, highlighting the necessity for active aging policies and sport and

physical activity promotional strategies to incorporate factors such as financials, culture,

barriers, and history regarding older adults (Costello et al., 2011; Gard et al., 2017).

!

4!

With the increased prevalence of aging policies and strategies in response to this

paradigm shift of active aging, there is variance in their conceptualization and direction

with regards to the general purpose of optimizing health, participation, and security to

improve quality of life in older age (Lassen & Moreria, 2014; WHO, 2002). For example,

the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) active aging policy framework (WHO, 2002)

focusses on achieving a healthy lifestyle by maintaining health and active participation

through physical activity promotion across the lifespan, as further demonstrated in their

Global Action Plan on Physical Activity (WHO, 2018). In contrast, the European Union

(EU) policy on active aging (European, Commission, 2012), while still deemed healthy,

approaches active aging from a demographic and economic standpoint as it seeks to

reform retirement by increasing productivity in later life to enhance an ‘age integrated

society’ (Lassen & Moreira, 2014). Shifting the focus to Western societies, Canada’s

‘sport for life’ marketing and promotional strategy depicts sport and physical activity as

direct response to the challenge of populations aging (Canadian Sport for Life, 2019).

The surge in active aging policies has led to increased physical activity and sport

opportunities for older individuals, potentially normalizing this population’s involvement,

particularly as self-responsibility for maintenance of their own health (Gard et al., 2017;

Horton et al., 2019). Notwithstanding the promise the aforementioned strategies of

utilizing sport and physical activity may demonstrate, it is a complex and problematic

solution (Dionigi, 2017). Essentially, sport and active aging policies tend to treat physical

activity as a tool to achieve better health, but rarely consider the perspectives, beliefs,

feeling, interests, knowledge, and motivations of older adults that contribute to a more

complete understanding of this population (Dionigi, 2017).

!

5!

Rowe and Kahn (1997) suggested that engagement in meaningful and productive

activities, related to friendship, social interaction, and organized participation,

particularly in later life, is an essential component in reducing the risk of mortality and

promoting health. Judiciously, as the popularity of Masters Sport broadens, so has the

emergence of qualitative research to further comprehend the meaning of competitive

sport in later life. Through qualitative research, unique perspectives from athletes have

been explored to understand meaning and motives of Masters Sport involvement (e.g.,

Dionigi, 2002a; Dionigi, 2002b; Dionigi & O’Flynn, 2007; Dionigi et al., 2011a; Dionigi

et al., 2013a; Horton et al., 2019) as well as social policy implications for health

promotions to older adults (e.g., Gard et al., 2017; Pike, 2011).

To illustrate, through opened ended interviews with Masters athletes, perceived

benefits of competitive sport were uncovered including: test the ability of an individual,

begin sport in later life, establish relationships, regular social interaction, traveling, and

personal growth (Dionigi, 2006b, Dionigi et al., 2011a). Furthermore, Masters athletes

emphasize negotiating the aging process, expressing youthfulness, and maintaining

bodily function related to the notion of ‘use it or lose’, to conceptualize their participation

and motivation in competitive sport (Dionigi, 2002b; Dionigi, 2006b; Dionigi & O’Flynn,

2007). Although, sport in later life is often purely associated with enjoyment and social

interaction, these older athletes who are motivated by competitiveness and desire for

improvement, demonstrates the diversity in meanings of sport participation (Dionigi &

O’Flynn, 2007). It can be suggested based on these findings that sport participation is

valuable for both the physical and psychosocial health of older athletes, and the perceived

value contributes to their motivation for participation. By understanding what older adults

!

6!

gain from their involvement and also what motivates them to stay involved, current

promotional strategies may be able to evolve and improve the sport and physical activity

experience (Dionigi, 2017).

Notably, Masters athletes are typically represented by middle-to-upper classes, as

well as possessing sufficient resources to afford travel, facilities, equipment, and

healthcare, thus, potentially posing limitations to other portions of the population

(Dionigi, et al., 2013b). Additionally, Masters athletes have associated older adults that

refrain from sport participation with negative characteristics such as laziness and lack of

motivation without considering the uncontrollable (e.g., disease), societal (e.g.,

opportunity), or personal (e.g., indulgence in relaxation) reasons (Gard et al., 2017).

While the majority of research in the realm of aging, sport, and physical activity has

utilized the perspectives of Masters athletes, findings are narrowed as it disregards less

active and athletic older adults, who are often the targets of sport and physical activity

promotional strategies. Thus, there is a need to gather the perspectives of a variety of

older adults and also understand implications of promoting alternative forms of sport and

physical activity, such as leisure, less structured, and informal pursuits (Dionigi, 2017).

The heterogeneity of older adults and complexities of promoting sport and

physical activity demonstrates the need for a multitude of approaches, activities, and

modifications. The promotion of a variety of leisure and less-structured pursuits is

lagging in Western societies, despite having similar mental, social, and emotional

benefits that are provided by more structured sport and physical activity pursuits (Dionigi

& Son, 2017; Douglas et al., 2017; Dupuis & Alzheimer, 2008). Engagement in

physically active leisure (PAL), which encompasses the continuum of sport participation,

!

7!

physical activity, exercise, and active leisure in later life, varies according to several key

variables such as gender, social context, and physical activity involvement (Dionigi,

2017). For example, older males in particular tend to gravitate towards more sport

specific activities and emphasize the competitive aspects of sport compared to females

(Eman, 2012; Statokostas & Jones, 2016). Although PAL pursuits in later life,

specifically sport, offer an opportunity to broaden social networks and relationships,

social constraints such as disapproval and pressure to participate, reveal the contrasting

side of social context for older adults’ involvement (Gayman et al., 2017a). Exploring the

perspectives from a specific population, such as non-elite athletic older men in a

particular sport (formal or informal), may provide concentrated insight for sport and

physical activity promotional strategies in the context of aging and PAL.

Ice hockey is a high intensity, cardiovascular team sport that emerged in Canada

in the years 1700 – 1887 (Hardy & Holman, 2009). Ice hockey has expanded across

multiple continents and resulted in the development of professional leagues (Hardy &

Holman, 2009). Particularly within Canada, ice hockey has increased in popularity and

participation among older adults. Notably, these trends for ice hockey among older

adults, especially in Western countries, has coincided with the recent phenomenon of

population aging as this cohort of individuals have been exposed to this growth

throughout their lifecourse. Specifically, factors such as style of play, televising ice

hockey, and the 1972 Summit series, increased exposure to Canadians and seemingly

developed an idea that ‘hockey’ and ‘Canada’ are linked as far as a national identification

(Earle, 1995).

!

8!

The complication of defining the ‘Canadian Identity’ relates to Canada’s

heterogenous demographics as Quebec’s distinctiveness, First Nations people or

Indigenous populations, and immigrants from many countries are a part of the collective

identity (Dopp, 2009). However, ice hockey’s blend of physicality, skill, toughness, and

commitment along with its cold winter-esque playing conditions made it simplistic for

Canadians to embrace due to their perception as being the tough rugged people of the

north (Earle, 1995). Furthermore, ice hockey players have been considered a source of

Canadian identity in which the qualities of Canada can be tangibly and intangibly

characterized (Dopp, 2009). In addition to ice hockey being the most popular sport in

terms of participation for individuals 15 years of age and older (Statistics Canada,

2019b), it is also considered an important national symbol by more than three quarters of

Canadians (Sinha, 2015). Dopp (2009) explains that Canadians may associate national

identity with peculiar obsessions such as ice hockey, and ice hockey’s relation to national

identity stems from the absence of an all-inclusive Canadian identity, which essentially

relates to the heterogeneity of the population.

When considering biological sex at birth, the multiple characteristics

encompassing ice hockey in Canada have demonstrated to be more favourable towards

males. For example, in relation to ice hockey, males outnumber females in participation

and viewership, have higher ratings of national symbolism, and embrace the masculine

nature of the sport (Macdonald, 2014; Sinha, 2015; Statistics Canada, 2019b).

Specifically, the ice hockey milieu is an environment that male players consider

communal and a break from ‘real life’ to speak freely among other males without the

presence of social barriers (Alsarve & Angelin, 2020). Although the prevalence of

!

9!

females in ice hockey is increasing, males still dominate popularity, viewership, and

notions of identity.

Recreational ice hockey, either formal or informal, has become a popular option

for adults-to-older adults to continue, or begin, participation in the sport. In recreational

ice hockey, body checking is often prohibited, slapshots in specific cases are removed,

overall intensity is lower, and the majority of games are played for fun (Atwal et al.,

2002; Voaklander et al., 1996). The prevalence of participation in ice hockey into

adulthood and later life has popularized organizations in North America that promote and

organize competition. For example, the Canadian Adult Recreational Hockey Association

(CARHA) provides services to assist in the development and delivery of ice hockey for

adults and older adults through the organization of leagues and tournaments (CARHA

Hockey, 2020), whereas Snoopy’s hosts an annual international senior ice hockey

tournament celebrating sportsmanship, camaraderie, and competition (Snoopy’s Home

Ice, 2020). Understanding the meaning and motivation of participating in recreational ice

hockey into older age can provide valuable insight and information to these

organizations.

Despite the benefits of ice hockey participation translating consistently to those of

physical activity, the potential health risks cannot be overlooked (Kitchen & Chowhan,

2016). Hockey injuries (professional and recreational) are primarily due to body, puck,

and stick contact, often occurring in the head and knees, (Lorentzon et al., 1988;

Mosenthal et al., 2017; Voaklander, et al., 1996) and have further influenced equipment

and rule modifications (e.g., Brophy, 2013). Additionally, the risk for sudden cardiac

events increases for vigorous activities that exceed six metabolic equivalents (METs),

!

10!

and with ice hockey considered to be greater than 8 METs, older adult players could be

viewed as being in jeopardy (Warburton et al., 2006). Although the risk is understood,

older adults should not be discouraged from playing as injuries are often considered mild,

sudden cardiac events are very unlikely to occur, and regular exercise to avoid scenario

of transitioning from sedentary lifestyle to vigorous ice hockey play is beneficial (Atwal

et al., 2002; Caputo & Mattson, 2005; Mittleman, 2002). Nonetheless, ice hockey is a

sport enjoyed by middle and older aged men, especially throughout Canada, for its

synergy of exercise and camaraderie despite being a high intensity sport with the

potential for injuries occurring at time in life during which there is greater risk.

Recently, research to develop an understanding of the influence participating in

recreational hockey in older age for men was conducted. Specifically, through qualitative

interviews with older male hockey players, the value of enjoyment, pleasure, and health-

related benefits of hockey in later life were noticed (Allain, 2020). Furthermore, playing

hockey in older age allowed these older men to form their own unique hockey experience

that is different from their youth, which often did not account for health benefits and

encouraged hegemonic masculinity (Allain, 2021). Ultimately, older male hockey players

navigate age-related risk in order to receive the benefits, find enjoyment, and resist aging

stories through participation in hockey (Allain, 2020).

Thus, although there is an abundance of evidence to illustrate that injuries or ill

health incidents may occur especially among an older adult population who engages with

such sport and physical activity as ice hockey, there is still a passion, a drive, and a sense

of identity, in particular among males, to continue their participation in later life. Similar

to the need for qualitative research to investigate various aspects and attributes as to why

!

11!

Masters athletes engage in sport and physical activity in later years despite a myriad of

quantitative research, there is a need to further understand facets of engagement in ice

hockey among middle-to-older adult males.

1.1 Purpose Statement

This study used a qualitative approach to understand the meaning and motivation

of ice hockey involvement for Canadian men aged 50 years and older. The majority of

qualitative research focused on aging, sport, and more broadly PAL, has examined the

collective perspectives of Masters and elite athletes that participate in a variety of sports.

To this point, there is a dearth of research from the perspectives of non-elite athletic older

adults that make up the majority of the population. The purpose of this study is to

understand the perspectives of Canadian male ice hockey participants aged 50 years and

older to advance knowledge of aging, sport, and more broadly PAL. Additionally, this

study aimed to gather valuable information from the perspectives of participants that can

be used to enhance physical activity and sport promotional strategies and organizations,

especially those specific to ice hockey for middle-to-older aged adults.

1.2 Research Questions

1.2.1 Central Question

How does playing ice hockey influence the aging experience for Canadian men

aged 50 years and older?

1.2.2 Sub-Questions

What is the meaning and motivation of playing ice hockey into later life for

Canadian men (50

+

years)? Do cultural, historical, and societal characteristics influence

!

12!

choice of sport participation for Canadian men (50

+

years)? In the context of ice hockey,

how do Canadian men (50

+

years) illustrate the domains of physical literacy (e.g.,

understanding, knowledge, confidence, competence, etc.)?

!

13!

2.0 Methodology

My thesis aimed to gain a better understanding of experience and intentionality

with respect to why middle-to-older adult Canadian men engage in recreational ice

hockey. To ascertain the perspectives of the participants, a qualitative approach was

employed.

2.1 Qualitative Approach

In order to collect data that aimed to provide insight into the perspectives of

middle-to-older Canadian men and their physical activity pursuits, in-depth interviews

were conducted with an interpretative phenomenological approach to qualitative research

design. The interpretative aspect is the adroitness of hermeneutics. Through a

phenomenological perspective, an attempt is made to understand how people perceive

and feel about their experiences (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Patton, 2002). Thus, to

effectively describe and understand a phenomenon or phenomena (i.e., the experience

and opinions of the participants), the hermeneutic (interpretative) perspective was the

most appropriate choice to guide inquiry for this study (Wojnar & Swanson, 2007).

Although the evolution of phenomenology and hermeneutics have been unique and

independent from each other, there is a history of uniting them together as a solitary

approach (Kakkori, 2009). In essence, hermeneutic phenomenology is useful for

describing lived human experiences as it interprets how we understand and engage in the

world around us, including ourselves and others, in relation to the social, political, and

historical forces that shape our experience (Wojnar & Swanson, 2007). Therefore,

through descriptions from participants, researchers are able to culminate the experiences

!

14!

and perspectives of several individuals who have all experienced a phenomenon

(Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Briefly, a note about the ontology (i.e., how humans can acquire knowledge, or

more simply put, the ‘study of being’) and epistemology (i.e., how knowledge is created)

from the perspective of the researcher needs to be provided as it may have an impact on

the chosen theoretical perspective (i.e., hermeneutic phenomenology) application of

gaining an understanding. This study used bounded realist ontology and constructionist

epistemology as philosophical approaches. Bounded relativism understands that a shared

reality exists within a bonded group (e.g., cultural, moral, cognitive), but realities exist

differently across other groups (Moon & Blackman, 2014). Furthermore, from

constructionist epistemology, interaction between subject and object (in this case ice

hockey) gives rise to meaning and knowledge within a defined social context, focussing

on how people create meaning in and out of engaging with the realties in their own world

(Moon & Blackman, 2014).

As the phenomenology approach was the main influence guiding knowledge

acquisition for this study, the theoretical perspective will be expanded on briefly here. It

is acknowledged that this study is only adopting the underpinnings of phenomenology. A

more pure approach to phenomenology would aim to have participants describe a

phenomenon, whereas this study attempted to dive deeper into understanding the

experiences and asked participants to explain more about their relationship with ice

hockey participation and aging. Phenomenology encompasses the resources to illustrate a

phenomenon/topic that is under-represented or poorly understood within the literature

(Pascal et al., 2011). For example, Dionigi (2006a) called for qualitative research in aging

!

15!

and competitive sport due to the increasing number of older athletes with the increasing

aging population. Previous research had taken a quantitative approach or failed to

consider the experiences of older athletes, demonstrating an opportunity to use in-depth

interviews and interpretative analysis to provide alternative ways to make sense of older

athletes and their relationship with competitive sport (Dionigi, 2006a). This is not to

devalue the role of quantitative research on aging and physical activity, rather it

encourages the utilization of different paradigms to capture variations of the phenomenon

(Grant & O’Brien Cousins, 2001). Notably, research has explored the influence and

meaning of sport in the lives of older adults to understand motivation, as well as how this

cohort continues to maintain their involvement into later life (e.g., Dionigi et al., 2013a;

Dionigi & O’Flynn, 2007). Additionally, understandings on aging and sport would

benefit from phenomenological analysis of the experiences, perspectives, and opinions of

older adults in specific sports. Previous research typically utilized the combined

perspectives of older adults that participate in a variety of sports, such as athletes in the

World Masters Games, with a small portion specifically focusing on individual sports.

Shifting attention to the perspectives of older adults in specific sports can be justified

through Dionigi’s (2006a) explanation of the heterogeneous nature of older adults

competing in sports since their motives for involvement are unique and may alter

throughout life or depending on the type of sport or event. Research intended to capture

the perspectives of a specific sport should include a population with one shared sporting

experience to determine how that sport in particular is important to that population and

may differentiate from other sports.

!

16!

The perspectives and experiences of older athletes have proven to be a valuable

source of knowledge as they contributed to: an understanding that sport is, or is in the

process of being normalized for this population, the way sport policy is shaped, and how

their social relationships are viewed (Gard et al., 2017). However, the majority of

qualitative research that has been done on the topic of aging, sport, and PAL has tended

to focus on Masters Athletes (Dionigi, 2017). Thus, there is a paucity of research that

utilized a qualitative interpretative approach and involved older adults who were less

active than elite athletes (e.g., Masters athletes), despite them being often the target of

sport promotion policy and strategies. In particular, there was an opportunity to explore

the population of older adults who were considered less active in their daily lifestyle in

comparison to the archetypal older athlete (e.g., Masters athletes), but still participated in

PAL pursuits such as recreational sport (e.g., ice hockey) in later life.

Middle-to-older adult Canadian men who self-reported as participating in

recreational ice hockey may be viewed as presenting a unique scenario in the realm of

qualitative interpretive research due to the sport’s relationship with Canadian identity,

expressions of masculinity (MacDonald, 2014), and social nature (Alsarve & Angelin,

2020). With the perception that ‘Canada’ and ‘hockey’ are intertwined entities, there may

be more depth to the meaning and motivation of participation that expanded beyond the

discourses discussed for aging, sport, and more broadly PAL within other studies.

Therefore, an interpretivist approach (i.e., hermeneutic phenomenology) was considered

the most appropriate way to properly understand the experiences and intentionality of

older Canadian men engaging in recreational ice hockey, an arguably culturally derived

!

17!

and historically situated sport, and how this knowledge acquisition contributed to a

further understanding of aging and sport.

2.2 The Researcher’s Role

Particularly for qualitative methodologies, the role of the researcher as the

primary data collector and interpreter entailed the identification of personal

characteristics that may constitute an influential aspect integrated into the study. In

essence, a researcher’s past experiences, ideologies, and demographics could have

influenced the interpretation of the qualitative data in way that would be different from

another researcher’s interpretation (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Thus, it was imperative

that the researcher explicitly identify these characteristics and how they may have shaped

the interpretations made, such as leaning towards certain themes or looking for ways to

support their position (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). However, instances where the unique

background and experience of individuals have provided valuable insight towards a

certain topic or population (Humble & Cross, 2010).

This study used in-depth interviews to understand the unique perspectives of

Canadian men aged 50 years and older playing recreational ice hockey in later life.

Although I am a male in my 20s, I have a variety of experiences with the target cohort,

ranging from interacting first-hand and playing alongside them, to spectating.

Specifically, after surpassing minor/junior hockey age restrictions, I have consistently

participated weekly with older men in pick-up hockey for approximately 8 years

(COVID-19 pandemic permitting). Furthermore, I have observed the perceived positive

discourses of playing recreational ice hockey into older age such as competition and

comradery, and also the negative aspects related to injuries and sudden cardiac events.

!

18!

Therefore, through my personal experiences of participating in ice hockey for more than

20 years, I have cumulated a sufficient understanding of the physical and psychosocial

benefits of playing ice hockey and what the sport demands from the body. However, with

regards to the influence of aging related to ice hockey, I can only be considered a witness

and listener, with insufficient understanding of the mindset while continuing participation

into later life. Notably, I have noticed a difference in competition when a combination of

older and younger players participated within the same pick-up game. For example,

although most older men appeared to enjoy interacting and competing with younger

players, I perceived they desire fair play and competition against others of the same age

and skill level. Lastly, I can declare that my overall experiences and perceptions of

hockey throughout my life have been positive. I also developed educational experience

through undergraduate and graduate level university courses in the context of aging,

physical activity, and ice hockey. These educational experiences may have influenced the

interpretation process such as creating certain themes or leaning to familiar conclusions

by referring to past knowledge or learned content (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Moreover, due to my past experiences of playing ice hockey throughout my life and with

the target cohort, I brought certain biases to the study. These biases shaped the way I

viewed, understood, and interpreted the data. Nonetheless, consulting with fellow peers

(i.e., research team, advisor) was required in order to check for influence during the

interpretation process and avoid bias.

2.3 Participants

This study was conducted with individuals who resided within Southwestern

Ontario, Windsor-Essex County in particular to gather the lived experiences and

!

19!

perspectives of Canadian men aged 50 years and older engaging in recreational ice

hockey. This region was chosen as it was an area accompanied by more than 10 ice

hockey arenas, with the majority having multiple ice pads for this cohort to participate in

private rentals or organized leagues. Notably, the Windsor Family Credit Union (WFCU)

Centre indicated there were 24 hours of privately rented ice times weekly on file as of

February 2020. Private ice time rentals were considered as being outside of minor ice

hockey, organized leagues, and free skates. Although the demographics of each private

ice time rental were unknown, when asked the WFCU employees estimated adult

recreational and/or old timer ice hockey used the majority of private ice time rentals.

Additionally, Windsor, Ontario in particular hosted the 2016 Canadian Adult

Recreational Hockey Association (CARHA) Hockey tournament that gathered

approximately 2,500 participants from 14 different countries (CARHA, 2019). Therefore,

it can be justified that this region displayed popularity for adult recreational ice hockey

and promotion of sport for this cohort.

The participants were purposefully sampled in accordance to the goals and

qualifications of the study (Patton, 2002). Participants selected were required to be: male,

50 years of age or older, able to speak English, have access to and experience with a

computerized device compatible with videoconferencing software (e.g., Zoom),

preferably living within Southwestern Ontario, and participating in recreational ice

hockey for at least 1-2 years (this minimum range was considered to recognize that since

March 2020, Southwestern Ontario was in a pandemic and continued to be through the

duration of this study, and thus, there may have been changes to recreational ice hockey

that confounded experiences). Additionally, the choice of participant’s age established at

!

20!

50 years and older stemmed from both research and personal experience. Firstly, overall

functional capacity was traditionally perceived to naturally decline after the age of 50

years old (Lassen and Moreira, 2014). Secondly, from personally witnessing players who

were 50 years of age and older, there was a lower perceived functional capacity when

playing and a greater frequency of injuries compared to younger counterparts.

Additionally, expanding the age range to be beyond 65 years of age and older to

encompass individuals 50 years of age and older, offered the insight of examining

perspectives and motivations that span the middle-to-older ages. Lastly, finding a

sufficient number of participants for this study at 65 years of age and older was thought at

the onset to potentially be difficult to acquire despite its rising popularity among this

cohort.

For a qualitative study with a phenomenological approach, Creswell & Creswell

(2018) recommended a sample size of three-to-ten participants. Furthermore, the aim was

to interview six or seven participants as this range has proven prosperous in previous

research that involved older Canadian men and their perspectives related to aging and

physical activity (Deneau et al., 2019b). Participants were recruited first by circulating an

email blast (existing directory) to a group of older hockey players who may be eligible.

Secondarily, a snowball approach was used through connections within the local ice

hockey community and previous participants. However, the intention was to interview

participants until saturation (i.e., no new emerging themes) was met.

2.4 Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected after ethics clearance was received and took place in

approximately Spring 2021 (Note: ethics clearance was obtained on March 19

th

, 2021).

!

21!

This included the conduction of the open-ended interviews with participants to elicit their

views and opinions and ranged from approximately one to three hours in length (Creswell

& Creswell, 2018). In relation to the goals of the study, the value of qualitative interviews

was the ability to control the topics being discussed as well as allowing participants to

refer to past experiences (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The semi-structured guide

(Appendix A) allowed for the control of topics being discussed, as well as the freedom

for participants to share their subjective experiences. In other words, although open-

ended questions were asked, probing questions afforded the opportunity to learn more

about the individual context, and provided versatility and flexibility (Kallio et al., 2016;

Mueller & Segal, 2015). Although it was recommended that interviews take place within

an environment that was comfortable to the participant to reduce potential feelings of

discomfort that may have impeded their willingness to share information (McGrath et al.,

2019), it was always possible. Due to a global pandemic declared by the WHO regarding

the coronavirus (COVID-19) in March of 2020, in-person data collection ceased. Thus,

the interviews took place virtually via a videoconferencing software (Zoom -

professional) and were recorded with the participants’ permission for the purpose of

verbatim transcription. In order to garner responses from different participants pertaining

to the same questions through a conversational approach, the structure of the interview

had a pre-determined set of open-ended questions to follow related to aging, physical

activity, and ice hockey (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Patton, 2002). Furthermore, to

assist with data collection, I had my own personal log to record notes and important

details that arose during the interview. Creswell & Creswell (2018) recommended that

researchers take notes during interviews in the event that recording equipment fails or

!

22!

other related malfunctions. Nonetheless, recording interviews granted the opportunity to

review and confirm assumptions made during the interview process.

A potential participant was instructed to email or call the researcher if they were

interested in volunteering for this study. When first contact was made with a potential

participant, I confirmed interest and eligibility to be involved with the study. Once these

two factors had been confirmed, I ensured I had the correct email information of the

participant in order to send them a Consent Form. It was important to provide the

potential participant a Consent Form in advance of data collection to ensure they had an

appropriate amount of time to review the details of the study in order to provide informed

consent. Furthermore, during this first contact, a date and time for data collection via

video conferencing was agreed upon. In the email that contained the Consent Form, the

date and time for data collection was also confirmed. Additionally, an email that

contained the videoconferencing information was provided if needed.

At the start of the data collection videoconference, the Consent Form was

reviewed with the participant, and they were able to ask any further questions. Once the

participant voluntarily agreed to be involved with the study, they were informed that the

recording of the call began, and they were be asked to reconfirm their consent to

participate for the recording. At the start of the recording, I also stated information such

as the date, time of day, and participant ID. To ease the participant into the process of

being asked interview questions, I asked some demographic questions (Appendix B). For

example, demographic questions included age, ethnicity, employment status, marital

status, meeting the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines, frequency of recreational ice

hockey involvement, and history of chronic disease and/or previous injuries. After the

!

23!

demographic information was collected, I clarified terms (e.g., PAL) that may have been

unfamiliar to participants.

The questions in the interview aimed to capture the opinions and perspectives on

several key themes, with involvement in recreational ice hockey into later life for men as

the overlying main theme. The several key themes the interview questions encompassed

included lived experiences throughout the aging process, physical activity involvement

into later life, opinions on sport participation for older adults, the meaning and motivation

of involvement in recreational ice hockey, and specifically why ice hockey was a

preferred sport choice for this cohort. The pre-determined questions in the interview

protocol served as the primary content in order to collect the intended data. However,

probes were utilized to either ask for more information or expand on a mentioned idea

(Creswell & Creswell, 2018). For example, “Tell me more about that.” or “Could you

explain that further?” were common examples to use in unison with the primary content

questions that provided further depth into ideas.

Prior to, and just after, each interview, I recorded my own feelings and

perceptions along with making my own personal notes about the interview. This

information included whether the participant was easy to talk to, if they were hesitant to

provide information, moments of excitement and humour, and disruptions during the

interview. Although these notes were not analyzed as data for this particular study, they

aided in understanding context, situation, and potential outliers that emerged.

All interview data were transcribed verbatim during the collection of data (rather

than after all interviews are complete). This was done primarily to determine if and when

saturation was reached, and to allow for data analysis to take place at a later date and

!

24!

time. Additionally, member checking was offered to participants which would have

included the participant receive a brief document (via email) containing general

information that outlines the themes, trends, and patterns of the deidentified transcripts

(Birt et al., 2016). However, all participants declined interest in member checking, with

most conveying they would rather read a final write up of the data.

2.5 Data Analysis

I utilized a simultaneous procedure as justified by Merriam (2002), in which data

analysis commenced simultaneously as aspects such as data collection were ongoing.

Essentially, the simultaneous procedure granted the opportunity to make adjustment

during the analysis process and focus on the dynamic emergence of themes, concepts,

and categories derived from the data (Merriam, 2002). Furthermore, this process assisted

in monitoring data saturation by treating analysis as a continuous and fluid process, rather

than establishing a set start and end to the findings.

The initial step consisted of reading through the data collected and reflecting on

the meaning of what the participant was saying and the overall impression of the data;

Creswell and Creswell (2018) accentuated the importance of this process. Furthermore,

Patton (2002) provided more justification by encouraging the researcher’s interaction

with that data, such as reading it several times to assist with the identification of patterns

and themes. Following the thorough reflection opportunity, analysis of the data

continued.

This study used a thematic analysis to identify, analyze, and interpret patterns of

meaning (i.e., codes) from the qualitative data collected during the interviews (Clarke &

Braun, 2017). Thematic analysis was useful for understanding data (both coding and

!

25!

comparing) in relation to participants lived experiences, opinion, perspectives,

behaviours, and practices; providing the foundation of understanding what participants

thought, felt, and did (Clarke & Braun, 2017). In general, coding was the process of

creating themes from the data through an inductive strategy of organizing the data into

smaller segments of information. This involved associating a theme or pattern with a unit,

such as a word or phrase, for distinction (Clarke & Braun, 2017; Creswell & Creswell,

2018; Merriam, 2002). Moreover, the selected words or phrases for themes were often

based on the actual language from the participants (vivo terms; Creswell & Creswell,

2018). The themes and patterns were derived from the interviews with the participants for

comparison purposes in order to identify common themes and patterns across

participants’ interviews (Merriam, 2002). Additionally, a secondary step employed was

the use of deductive analysis which involved the use of pre-existing categories from

similar literature(s) to help guide the coding process (Patton, 2002). This latter aspect was

instrumental for determining how the data were to be presented in the current study. As

many codes and themes were yielded from that data, the research team met to discuss a

feasible approach for interpreting the data and relating it back to the existing literature.

Thus, it was acknowledged that through the production of the narrative that this led to

additional layers of analysis, the forming of varying narratives, and the connection of

themes to interpret the qualitative data, that there were multiple feasible approaches to

present how playing ice hockey influenced the aging experience for Canadian men aged

50 years and older. Ultimately, the intention was to make sense of the interviews by

aggregating the qualitative data down into a smaller number of interesting features of the

data that were relevant to the study (Clarke & Braun, 2017; Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

!

26!

2.6 Data Interpretation

The interpretation process involved several procedures to meet the goals of the

study and transition the qualitative data into meaningful findings to capture in essence,

“What were the lessons learned?” (Creswell & Creswell, 2018, p. 198). While qualitative

descriptions contributed to organizing and understanding a phenomenon, interpretation

called for attaching significance to what was found and making sense of the findings by

going beyond the descriptive data (Patton, 2002). Creswell & Creswell (2018)

recommended a rich and thick description of the findings to engage readers, properly

convey the perspectives captured, and transcend the discussion to a shared experience.

However, Patton (2002) emphasized the importance of balance between description and

interpretation in order to illuminate what was significantly important without being

overwhelming and repetitive. Using a balanced quality of description assisted with the

phenomenological interpretation of the data. From Heidegger’s hermeneutics

(interpretative) perspective, I went the basic description of concepts and ideas, such as

aging and ice hockey in the lives of middle-to-older aged men, to truly understand human

experiences (Wojnar & Swanson, 2007). Therefore, through the vehicle of detailed

descriptions and adherence to the social, political, and historical context of human

experiences, I gathered a deeper understanding of the meaning of involvement in ice

hockey in lives of the target cohort.

The additional procedures of the interpretation processes involved comparing

findings to the literature as well as discussing a personal perspective (Creswell &

Creswell, 2018). The latter of the two procedures refers back to the reflexivity of

qualitative research as it was understood the inquirer brings personal experiences, views,

!

27!

and ideologies to the interpretative process (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Patton, 2002).

Moreover, discussing the qualitative study with an external source (e.g., an advisor),

provided an interpretation beyond the researcher in the event of a misunderstanding or

notable personal bias (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The former procedure addressed the

notion that most research designs stem in various ways from previous research and

propositions (Patton, 2002), presenting the opportunity to compare findings to similar

research with a different setting. Qualitative research in the context of aging and sport

was utilized for comparing similarities and differences, which contributed to a further

understanding of this phenomenon.

Overall, the goal of this study was to gather the unique experiences of Canadian

men aged 50 years and older participating in recreational ice hockey to understand their

meanings and motivation(s) for participation. This study drew inspiration from previous

research that explored the perspectives and experience of older athletes who continued to

participate into later life. This study examined the perspective of older men who play

recreationally and/or for fun, rather than participants of notable athletic competitions such

as the World Masters Games. The stories and descriptions gathered from the target cohort

contributed to literature in aging and sport to further understand the numerous dynamics

within this area of research.

!

28!

3.0 Results

In accordance with the constructed requirements and design of this study, all ten

participants recruited were Canadian and aged 50 years of age or older and resided in

Southwestern Ontario. Overall, participants ranged from 58-to-76 years of age

(approximate mean age of 63 years). All participant identified as male and different

renditions of Caucasian Canadians. For employment, six indicated they work full-time,

two work part-time, one was retired, and one was on leave from his full-time job at the

time of the interview. With regards to health-related items, all participants self-described

themselves as being in good-to-very good health. Moreover, all participants but one

conveyed they engaged in physical activity (PA) three or more hours weekly prior to

Covid-19, with the lone participant engaged in one-to-three hours of PA weekly. With

respect to Covid-19 restrictions, eight participants indicated they were currently engaged

in PA the same amount of time as they would prior, with two participants, Lester (3+

hours to 1-3 hours) and Russ (3+ hours to less than 1 hour) seeing a decrease in their PA

engagement weekly. Additional information is presented in Table 1.0.

!

29!

Table 1.0: Participant Demographics

Alias

Year of

Birth

Highest Level of

Education

Completed

Self-described

Ethnicity

Parents

from

Canada

Marital

Status

Years

Playing

Hockey

Lester

1961

Undergrad

Italian-Canadian

No

Married

45

Greg

1963

Undergrad

Caucasian

Yes

Married

51

Charlie

1963

Doctorate

Italian-Canadian

No

Married

50

Dwayne

1963

High School

French-Canadian

Yes

Married

23

Gerald

1945

Masters

Caucasian-

Canadian

Yes

Married

60

Russ

1965

College

French-Canadian

Yes

Married

46

Dean

1961

Undergrad

Caucasian-French-

Canadian

Yes

Divorced

50

Ken

1963

Undergrad

Greek-Canadian

No

Common

Law

25

Guy

1946

Masters

Canadian

Yes

Married

65

Gordon

1950

Masters

Caucasian-

Canadian

Yes

Married

45

With respect to hockey participation, the mean number of years of playing hockey

throughout the participant’s life was 46 years, ranging from 23-to-65 years of experience.

The majority indicated they had played hockey since early childhood, while two of the

participants took up the sport in middle age. Notably, many participants that began

playing in childhood indicated pauses or interruptions during middle age due to factors

such as raising children, relocation, or occupational demands. However, such pauses in

participation were often short lived and mere products of circumstance. Furthermore,

through the interviews it was found participants played in various types of hockey

growing up such as house league, travel, and collegiate level. Hockey participation in

later life included pick-up, and league and tournament play, with the latter two often

formally incorporating varying age groups (e.g., 65+ years). It is important to note the

type of hockey the participants engaged in, with respect to this study the participants

were involved with a combination of types, because it can impact the motivation and

meaning for someone playing hockey. Specifically, participants indicated the distinct

!

30!

metaphorical naming of leagues such as The Rusty Blades, Sliver Fox, and Living Dead

as they continued to play into older age. Moreover, although some participants played

multiple times weekly with a combination of pick-up and league participation, all

participants consistently played hockey at least once weekly. For conditions and injuries

related to hockey, half of the participants specified living with one chronic condition each

which included atrial fibrillations, arthritis, sport’s hernia, depression, and post-Bends

symptoms. Notably, none of the participants relayed that their condition hampered their

hockey performance or frequency aside form Greg (post-Bends symptoms) who

explained he experienced complications with hockey and rehabilitation. Lastly, the

majority of participants indicated they experienced an injury at some point in life,

whether hockey related or not, that resulted in absences from hockey ranging from 1

month to 1 year. However, most injuries were described as mild and occurred at varying

ages, not restricted to later life, for the participants.

3.1 The Wellness Wheel Concept

Encompassed within the concept of a Wellness Wheel is the understanding of

multiple domains contributing to an individual’s attainment of ‘being’ well and healthy.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2021) defined ‘wellness’ as “an optimal state of

health of individuals and groups.” However, instead of designating the absence of disease

as being healthy, this definition accentuated the importance of fulfilling potential in

different aspects of life such as physically, psychologically, socially, spiritually,

economically, and identity (WHO, 2021). Commonly incorporated within the Wellness

Wheel is a holistic approach to measure and assess the multiple embedded dimensions

with respect to an individual or group, providing an objective evaluation of well-being

!

31!

(Hattie et al., 2004; Myers et al., 2000). The Wellness Wheel approach was an

advantageous approach when interpreting the data as it allowed for the incorporation and

exploration of heterogeneity and holistic understanding particularly focused on living a

healthy lifestyle among older adults. Notably, there was no definitive approach to the

construction of an individual’s or groups’ Wellness Wheel due to the myriad of physical,

social, and historical factors, affording the unique perceptions and experiences of an

individual to emerge (Myers & Sweeney, 2007). Therefore, through the perspectives and

experiences of older men in the current study, the concept of a Wellness Wheel was

adapted to assess how hockey participation acted as a contributing factor to fulfill

multiple dimensions of the participants lives related to achieving a state of well-being. As