Rowan University Rowan University

Rowan Digital Works Rowan Digital Works

Theses and Dissertations

7-1-2019

The effectiveness of character education on student behavior The effectiveness of character education on student behavior

Katie M. Ferrara

Rowan University

Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd

Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, and the Special Education

and Teaching Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Ferrara, Katie M., "The effectiveness of character education on student behavior" (2019).

Theses and

Dissertations

. 2702.

https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/2702

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion

in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please

contact graduateresearch@rowan.edu.

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF CHARACTER EDUCATION ON STUDENT

BEHAVIOR

by

Katie M. Ferrara

A Thesis

Submitted to the

Department of Interdisciplinary and Inclusive Education

College of Education

In partial fulfillment of the requirement

For the degree of

Master of Arts in Special Education

at

Rowan University

May 8, 2019

Thesis Chair: Margaret Shuff, Ed.D.

© Katie M. Ferrara 2019

Dedication

I would like to dedicate this thesis to my husband, Michael. You have made many

sacrifices to allow me to chase my professional dreams. Thank you for supporting me

throughout my Master’s journey. All of this would be near impossible without your love

and encouragement.

ii

Abstract

Katie Ferrara

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF CHARACTER EDUCATION ON STUDENT BEHAVIOR

2018-2019

Margaret Shuff, Ed.D.

Masters of Arts in Special Education

The purpose of this study was to determine if character education in schools is

effective enough to positively increase students’ moral and ethical behaviors and values.

Students’ behaviors in grades Kindergarten through fifth across three different

elementary schools were examined. Measurements were taken prior to the

implementation of a character education program and were reexamined after the first

year. The results of the study revealed all three schools decreased in filed discipline

reports and increased in positive behaviors from the execution of character education

programs.

iii

Table of Contents

Abstract …………………………………………………………………….…. ii

List of Figures ……………………………………………………………….... v

List of Tables ………………………………………………………………...... vi

Chapter 1: Introduction ………………………………………………………... 1

Statement of the Problem ………………………………………………..... 1

Significance of the Study ………………………………………………..... 2

Purpose of the Study …………………………………………………….... 4

Key Terms ……………………………………………………………........ 5

Chapter 2: Review of Literature ……………………………………………..… 6

Positive Implications of Character Education ………………………..…… 6

Negative Implications of Character Education ……………………………. 8

Conclusion …………………………………………………………………. 9

Chapter 3: Methodology ……………………………………………………….. 11

Setting ……………………………………………………………………… 11

Schools ………………………………………………………...………… 11

Classrooms ……………………….……………………………….……... 11

Participants ……………………………………………………….……….... 12

Students …………………………………………..………..…………...… 12

Teachers ……………………………………………….………….…..….. 14

Materials ………………………………………………………..………...… 14

Measurement materials …………….……………....…...…...…………… 14

Research Design ……………………………………..…………………….... 15

iv

Table of Contents (Continued)

Procedures ………………………………………………………………. 16

Measurement Procedures ………………………….…..………………… 17

Observations …………………………………….….………………… 17

Reports …………………………………………...….………………...17

Data Analysis ………………………………………………………….... 17

Chapter 4: Findings …………………………………………………………. 18

Results ……………………………………………….……………….…. 18

Pre-implementation behaviors …………………….…………….......... 18

Intervention year 1 ………………………………….………...………. 21

Chapter 5: Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendation …………………. 28

Findings ………………………………………………………………… 28

Limitations ……………………………………………………………… 29

Implications and Recommendations ………………………………….… 29

Conclusion ……………………………………………………………… 30

References ………………………………………………………………….... 31

v

List of Figures

Figure Page

Figure 1. Pre-Implementation of Character Education Program for School A …… 25

Figure 2. Pre-Implementation of Character Education Program for School B …… 26

Figure 3. Pre-Implementation of Character Education Program for School C …… 27

vi

List of Tables

Table Page

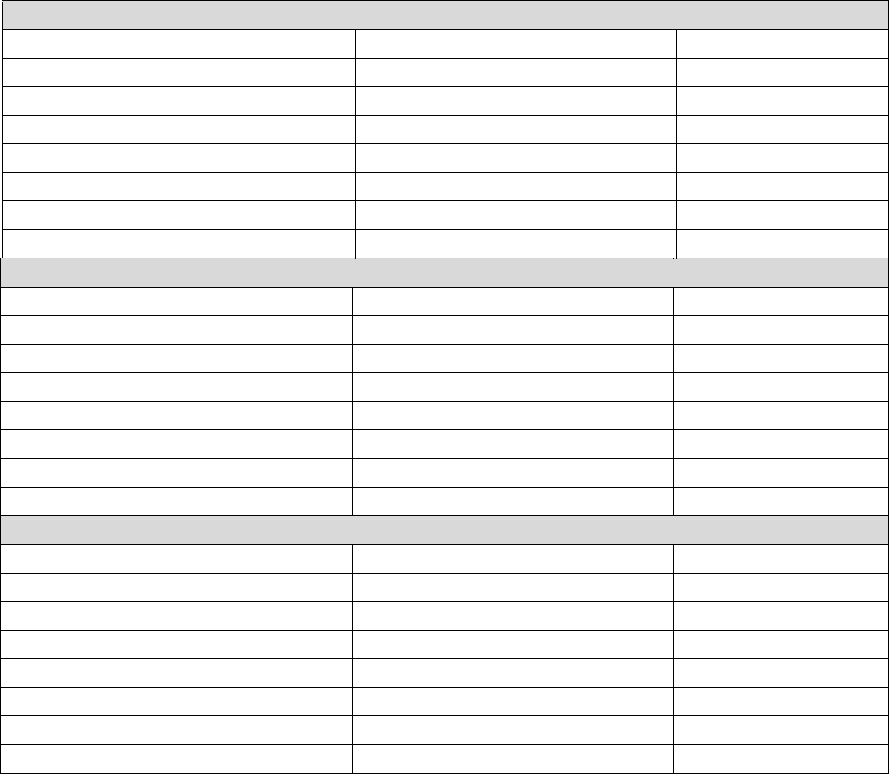

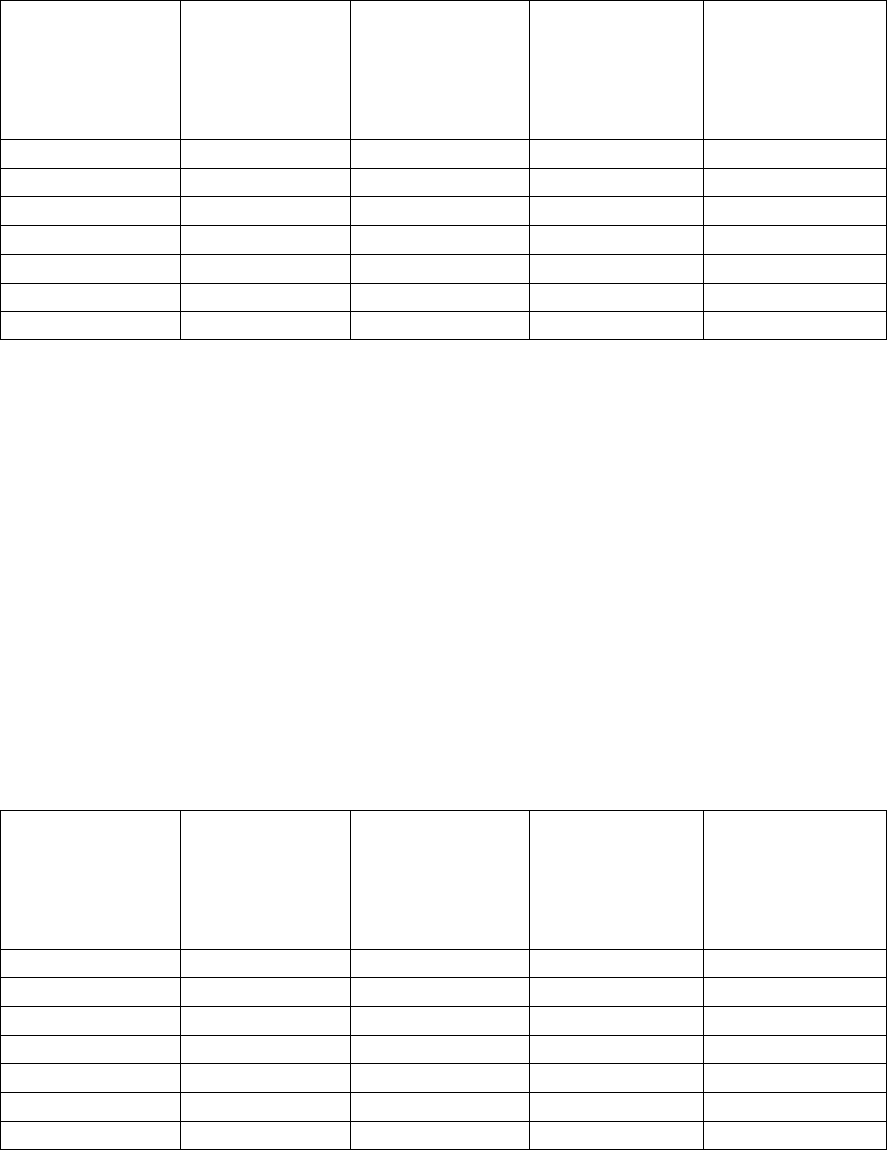

Table 1. General Participant Information …………………………………………. 13

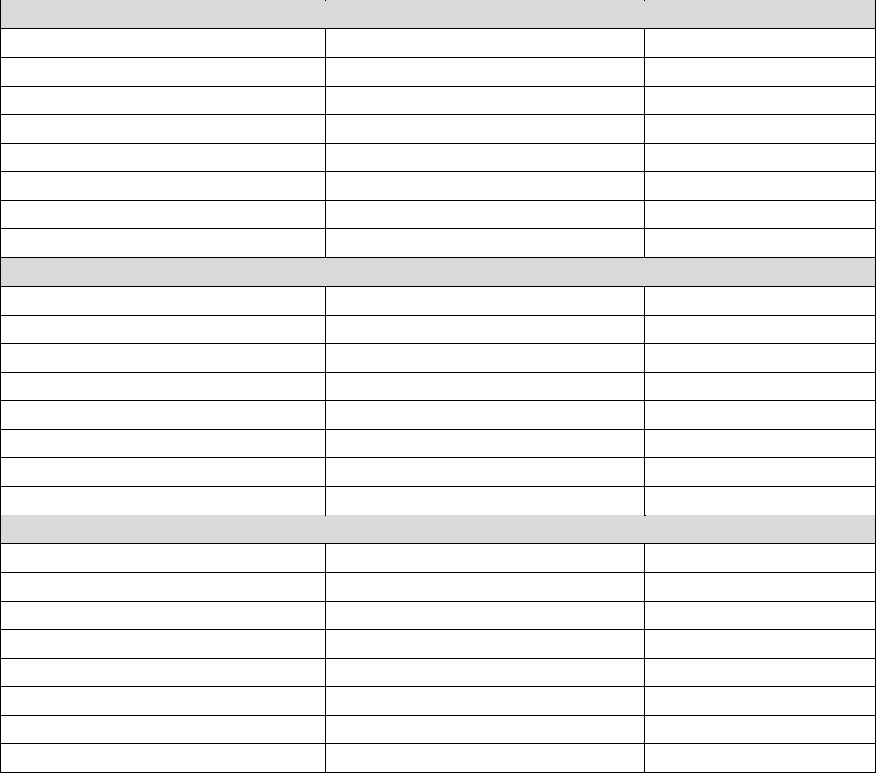

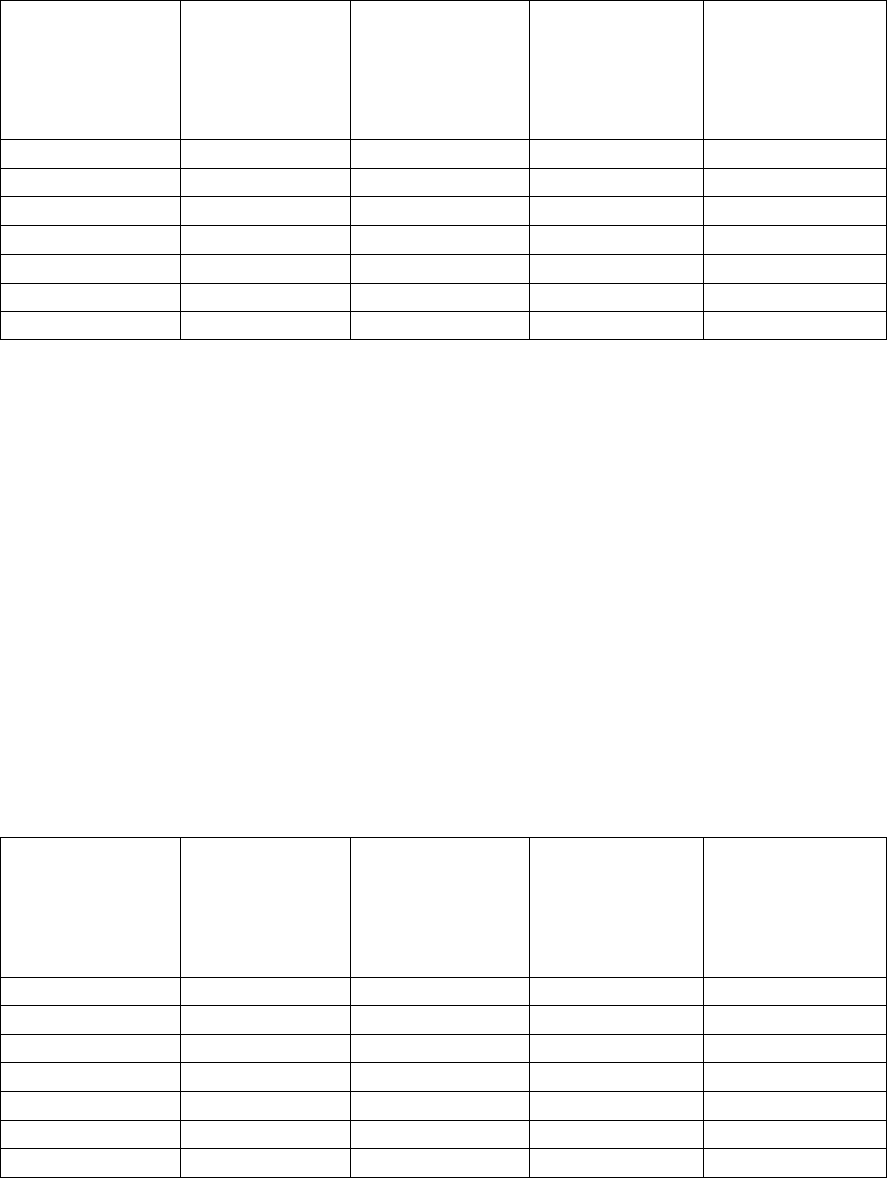

Table 2. Data Collection Table ……………………………………………………. 15

Table 3. Pre-Implementation Behaviors School A (2016-2017) …………….….… 19

Table 4. Pre-Implementation Behaviors School B (2016-2017) ……………..…… 20

Table 5. Pre-Implementation Behaviors School C (2016-2017) ……………..…… 20

Table 6. Post-Implementation Behaviors School A (2017-2018) ……………….... 22

Table 7. Post-Implementation Behaviors School B (2017-2018) ……………….... 22

Table 8. Post-Implementation Behaviors School C (2017-2018) ……………….... 23

Table 9. Pre- and Post-Implementation ………………………….………………... 24

1

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Character education is a learning process that influences all people within a

community to exhibit moral and ethical values such as respect, responsibility, and

citizenship towards self and others. Since students spend much of their time in

classrooms, schools across the country have enforced character education programs

beginning before the 20

th

century. The schools have seen this time spent in classrooms as

an opportunity to teach these core values to promote strong character and citizens among

the youth. The word “character” originates from the Greek meaning “to make a mark

on,” such as to have made an impression or to be remembered for. Having good

character refers to behaving in a positive manner and developing positive virtues and

habits. In 2008, the Character Education Partnership (CEP), defined character as “human

excellence” and focusing on “being our best and doing our best.”

Statement of the Problem

Street crime, violence, suicide, drug and alcohol abuse, bullying, teen pregnancy,

and a decline in civility are just some examples of the unfortunate events that have taken

place within schools and school communities in the United States. To address these

concerns, President Clinton addressed the nation on January 23, 1997. He called for

schools to teach students about the importance of values and good citizenship through

character education (Character Education Manifesto, 2002). After President Clinton’s

address, character education programs became state-mandated in an effort to instill

moral, positive and ethical values to support social, behavioral and emotional

development in students. However, it comes into question whether the character

2

education programs implemented in schools, in fact, replace negative behaviors. It

becomes a challenge for schools to assume the responsibility of encouraging students to

develop and maintain good character if families, neighborhoods and religious

communities are not in on the task together.

In a study completed by the National Center for Educational Statistics, more than

one out of every five students reported being bullied in 2016 (Lessne & Yanez, 2016).

Even more so, “students with specific learning disabilities, autism spectrum disorder,

emotional and behavior disorders, other health impairments, and speech of language

impairments report greater rates of victimization than their peers without disabilities

longitudinally and their victimization remains consistent over time,” (Gage & Rose,

2016). The purpose of President Clinton’s character education program initiative was to

decrease or eliminate the number of negative behavior cases. However, studies, research,

statistics, and social media have shown a continuation of these negatives behaviors.

Significance of the Study

In the early 1990s, the idea of a traditional family unit was beginning to change in

American society. Divorces, single parenting, same-sex orientation preferences, and

adoptions are just some of the examples of the changing family dynamics that were on

the rise throughout the nation. Furthermore, special education was becoming more

predominant. Students started to become diagnosed with conditions including

hyperactivity disorders, behavior and emotional disorders, autism, cognitive impairments,

and intellectual and developmental disabilities. Ironically enough, there was a nearly

300% increase in social problems faced by public education at this time such as violence,

racism, teen pregnancy, low self-esteem, and drug and alcohol abuse (Sojourner, 2012).

3

Additionally, in 1992 the National Research Council named the United States as the most

violent nation in the world. A commonality appeared in that the young people involved

in violent acts throughout the nation seemed to be alienated, did not have strong and

meaningful relationships with their parents or other adults, violent video games, had

unlimited access to the Internet, had negative influences and they were bullied in school.

Due to these rising issues and President Clinton’s demand for character reform,

schools around the nation began implementing structured character education curriculum

and programs to promote fairness, equality, integrity, honesty, respect, responsibility, and

compassion. The intention of implementing character education programs is to

disintegrate problematic behaviors such as violence, bullying, dishonesty, and

irresponsibility. However, not all of society is convinced with the character education

programs. Some believe character education is not enough to change the youth’s

negative conducts because it becomes rare that children follow the practices of what their

schools and educators preach (Snyder, Vuchinich, Eashburn, & Flay, 2012). Similarly,

according to Black (1996), “there is little positive correlation between what students learn

about good character in school and the extent to which they demonstrate good character

both in and out of school,” (p. 29).

Character education cannot simply be fulfilled in schools through reading books,

hanging up posters and banners, and using catchy slogans. Students’ behaviors will not

indefinitely change through these experimental practices. Schools need to do more than

concentrate on the cognitive side of character (Lickona, 1991). Lickona (1991) goes on

to state that students need to be committed to positive behavior and values and they need

to practice the moral actions in order to build character. Elias (2009) argued that it is

4

imperative for not only teachers, but the entire school community to carry out the

practices and framework of building character within our youth. However, character

must also be built within ourselves in order for character education to be effective and

lasting.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to determine if character education in schools is

effective enough to positively increase students’ moral and ethical behaviors and values.

In this study, I will examine the effectiveness of character education in three suburban

elementary schools in Cherry Hill, New Jersey one with a population of 304 students

(School A), the second with a population of 499 students (School B), and the last

elementary school with a population of 417 students (School C). The schools include

grades kindergarten through fifth grade classes.

School A has 19% of the student population participating in the Free and Reduced

Lunch Program and 15% receiving special education services. The average absentee rate

since enrolling in kindergarten is 28%. The Great Dream program developed by Richard

Layard, Geoff Mulgan and Anthony Seldon in 2010 was adopted by the school in the fall

of 2017 and is in its second year of implementation. The purpose was to establish a

happier and more caring community and society.

School B has 31% of the student population participating in the Free and Reduced

Lunch Program and 16% receiving special education services. The average absentee rate

since enrolling in kindergarten is 7%. The Responsive Classroom Initiative was adopted

by the school is the fall of 2015. The purpose of this program is to integrate academic

5

success and social-emotional skills (SEL) to create an environment where students do

their best learning.

School C has 33% of the student population participating in the Free and Reduced

Lunch Program and 21% receiving special education services. The average absentee rate

since enrolling in kindergarten is 13%. Lions Quest Skills for Growing is a K-5 program

that integrates social and emotional learning, character development, drug and bullying

prevention, and service-learning. The program promotes positive student behaviors that

lead to academic success.

The objective of implementing character education within schools is to improve

students’ academic achievement, behavior, school culture, peer interaction, and parental

involvement. I believe that students who receive a character education program such as

The Great Dream will increase in pro-social behaviors such as cooperation, respect, and

compassion and will replace negative behaviors such as violence, disrespect, apathy, and

underachievement.

The research question examined in this study is:

- Does character education improve student behavior?

Key Terms. For the purpose of this study, the term “character” will be used here as

having positive morals, values, and habits (Character Education Manifesto, 2002)

6

CHAPTER 2

Review of Literature

It is intended for character education to be taught in schools in order to decrease

undesirable behaviors. The purpose of such programs is to instill moral and ethical

standards to prepare students for becoming valuable members of society. The

effectiveness of character education on student behavior and the review of literature can

be presented from both positive and negative perspectives. Examining each viewpoint

will help to determine if character education can improve student behavior.

Positive Implications of Character Education

With the expectation that schools will develop, deliver and implement character

education programs, there are no set guidelines as to the exact content that is to be taught.

However, the importance of character education is highlighted as “promoting prosocial

attitudes and behavior that support the development of social competence and a

cooperative disposition,” (White & Warfa, 2011). One program that has shown positive

results is The Building Schools of Character program. This platform uses an “ecological

framework to develop an understanding of social constructs associated with a person’s

schemas of behavior and is rooted in the empirical evidence gained from developmental

research” (White & Warfa, 2011). Such programs use Vygotsky’s zone of proximal

development (SPD) to develop a child’s schemas of behaviors. The results indicated that

prosocial character education programs positively affect students’ abilities to meet the

social, emotional, and cognitive needs. Students’ on-task behaviors nearly increased

49%, while their off-task behaviors decreased 51%.

7

Social-emotional and character development programs, such as Positive Action

(PA), have also shown success in improving school quality. “The PA program is a

comprehensive, school-wide social-emotional and character development program

designed to improve academics, student behavior and character,” (Snyder, Vuchinich,

Eashburn, & Flay, 2012). The program is curriculum that consists of 140, 15-20-minute

lessons taught over the course of 35 weeks by the classroom teacher. Lessons cover a

total of 6 major concepts that include self-concept, physical and intellectual actions,

social/emotional actions for managing oneself responsibly, getting along with others,

being honest with yourself and others, and continuous self-improvement (Snyder et al.,

2012). Two studies were completed to examine the PA program utilizing quasi-

experimental designs and matched-control comparisons. Snyder and colleagues reported

that both studies showed positive effects on student achievement in academics and a

decrease in problem behaviors (e.g., suspensions, violence rates, bullying). When the

schools were examined 1-year after the implementation of the PA program, the schools’

report cards stated an improvement on standardized tests for reading and math and lower

absenteeism, suspension, and retention rates.

Moral education has become a common practice in schools across the country.

The purpose of moral education is to teach students to be honest, smart and good

(Lickona, 1991). “Through discipline, the teacher’s good example, and the curriculum,

schools have sought to instruct children in the virtues of patriotism, hard work, honesty,

thriftiness, altruism, and courage” (Lickona, 1991, p. 59). In other words, teachers

demonstrate moral education through the use of preexisting school and classroom

curriculum and instruction. For example, children can practice their reading while

8

learning about heroism and virtue. Teachers choose reading assignments that captivate

young readers and include characters who display ideal character traits. According to

Pritchard (1998), students who have moral education built into their curriculum are self-

disciplined and tend to score higher on achievement tests than students who do not

identify with positive behavior characteristics. Studies have also shown that moral

education makes it possible for all students to achieve and show greater success. “Moral

education is a recognized educational standard that introduces a noncompetitive goal for

students to aim at, a goal that is within the reach of many more students than is academic

excellence” (Pritchard, 1988).

Negative Implications of Character Education

Even if teachers do teach children to value positive characteristics, it hardly

becomes an easy task to initiate. When character education is implemented into the

school curriculum, it is expected that students will continue with what they learned and

apply it within society and social situations outside of school. Teachers cannot supervise

the students beyond the classroom. Therefore, it comes into question the significance and

the effectiveness of teaching character education if children will not oblige, or follow

through, with the values that were taught through a specified character education program

(Pritchard, 1988).

In order for a character education program to be effective, it must involve the

entire faculty, staff, parents, and community. “Cooks, custodians, and bus drivers, as

well as teachers, parents, and community must be involved if student behaviors are to be

positively affected.” However, having various individuals designating character traits,

such as “respect,” can become confusing for a child because the word has a different

9

meaning for each person. “The student receives mixed messages about the trait;”

therefore, could become lost on how to express and show respect towards themselves,

others, and property (Bulach, 2002).

Another conflict with teaching character education in schools is there could be

very little change in student behaviors because the repetition of teaching the same

character traits. “If a system has twenty-five traits to cover and they are repeated each

year, students will say, ‘We did that last year.’ They become bored with it and do not

take it seriously” (Bulach, 2002, p. 274). Although schools may be meeting the state

mandates, the character education programs can be ineffective due to the lack of student

interest and it could take time away from the regular instructional programs.

Conclusion

The hope of promoting and delivering character education within schools is to

develop “children’s rational and ethical decision-making, problem-solving, and conflict-

resolution skills,” (White & Warfa, 2011). For some, character education programs can

be deemed ineffective, time consuming, and inconsistent. However, many believe such

programs can meet students’ social, emotional, and cognitive needs. Further research on

schools’ character education programs is being conducted in order to investigate the

effectiveness on student behaviors.

The goal of this study is to determine if character education in schools is effective enough

to positively increase students’ behaviors. To conduct this research, three schools’

character education programs within the Cherry Hill Public School District will be

examined. Data of the schools’ behavior and discipline reports will be collected from the

beginning of the implementation school year to the end of the school year. Results will

10

be analyzed to determine if character education has no, some, or significant efficacy on

student behavior.

11

CHAPTER 3

Methodology

Setting

Schools. The study was conducted across three elementary schools located in a

suburban town in New Jersey. The school district consists of one preschool, twelve

elementary schools, three middle schools, and three high schools. During the 2017-2018

school year, there were approximately 10,996 students enrolled in the district. Three

elementary schools were examined during this study. The length of the elementary

school day is approximately 6 hours and 30 minutes with 5 hours and 30 minutes of

instructional periods. School A served 304 students in grades Kindergarten through fifth

grade. Out of the 304 students enrolled, 67 students were identified as receiving special

education services. There were 47 students classified as economically disadvantaged.

School B served 417 students in grades Kindergarten through fifth grade. Out of the 417

students enrolled, 88 students were identified as receiving special education services.

There were 121 students classified as economically disadvantaged. School C had 499

students enrolled in grades Kindergarten through fifth grade. Out of the 499 students that

attended, 80 students received special education services. There were 155 students

classified as economically disadvantaged.

Classrooms. The study was conducted in Kindergarten through fifth grade

general education and special education classrooms in all three schools. Schools A, B,

and C have access to SMART boards within the classrooms and libraries. The

classrooms all have Chromebooks assigned to each student. Each classroom teacher

participates in their school’s character education program and implements character

12

education lessons. The participants in the study attended the schools during the 2016-

2017 and 2017-2018 school years.

Participants

Students. A total of 1,223 students, from 3 different elementary schools within

the same school district, participated in this study. The participants ranged in age from 5

to 11 years old in grades Kindergarten through fifth grade. All students are identified as

being in general or special education, with 235 students receiving special education

services. Of the 1,223 participants, 615 are females and 608 are males. Table 1 shows

general participant information.

13

Table 1

General Participant Information

School A

Grade

Students

Age

Kindergarten

40

5-6

First

31

6-7

Second

49

7-8

Third

59

8-9

Fourth

52

9-10

Fifth

42

10-11

Special Education/Ungraded

31

5-11

School B

Grade

Students

Age

Kindergarten

55

5-6

First

64

6-7

Second

67

7-8

Third

81

8-9

Fourth

64

9-10

Fifth

63

10-11

Special Education/Ungraded

23

5-11

School C

Grade

Students

Age

Kindergarten

70

5-6

First

83

6-7

Second

79

7-8

Third

86

8-9

Fourth

85

9-10

Fifth

85

10-11

Special Education/Ungraded

11

5-11

14

Teachers. A total number of 84 teachers instructed the classes for the duration of

this study. The average years of experience in School A was 9 years with 8 staff

members holding a Bachelor’s degree and 14 holding a Master’s degree. School B’s staff

members have an average of 12 years of experience with 14 teachers having a Bachelor’s

degree and 18 teachers having a Master’s degree. The average years of experience in

School C was 12 years of experience with 11 teachers holding a Bachelor’s degree and

19 teachers holding a Master’s degree.

Materials

The materials used in this study include a laptop with internet access, electronic

chart to document and compare discipline reports according to grade level from 2016-

2017 and 2017-2018 from the 3 elementary schools, electronic access to The Great

Dream Character Education Program, electronic access to The Responsive Classroom

Initiative, and electronic access to Lions Quest Skills for Growing.

Measurement materials. A discipline report chart, shown in Figure 1, was

created to document the number of reports that were filed prior to the implementation of

a character education program within the schools. In the same chart, reports were

documented a year after the implementation of the schools’ character education

programs. The discipline reports were collected from the schools’ principals and

guidance counselors.

15

Table 2

Data Collection Table

Research Design

The research was conducted using single subject design methodology and a one-

shot experimental case study. The experimental treatment, being the character education

programs in each school, was introduced and then observed over the course of a school

year. The baseline data was collected through the collaboration of the schools’ principals

School A

Grade

Pre-Implementation

Year 1

Kindergarten

First

Second

Third

Fourth

Fifth

Special Education/Ungraded

School B

Grade

Pre-Implementation

Year 1

Kindergarten

First

Second

Third

Fourth

Fifth

Special Education/Ungraded

School C

Grade

Pre-Implementation

Year 1

Kindergarten

First

Second

Third

Fourth

Fifth

Special Education/Ungraded

16

and guidance counselors. The principals and guidance counselors provided information

regarding their discipline reports prior to the implementation of a character education

program during the 2016-2017 school year. The data collected displayed the number of

discipline reports that were filed before a character education program was put into

effect. Once a character education program was put in place at each school during the

2017-2018 academic school year, data was collected on the amount of discipline reports

that were filed. At the end of the study, data from the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018

academic school years were compared to determine if the amount of discipline reports

filed had decreased.

Procedures

The research was observed over the course of an entire academic school year,

September 2017-June 2018. Prior to the observations, each classroom teacher introduced

their school’s new character education program to their students through mini-lessons,

social activities, and presentations. To further the students’ understanding of their

school’s character education program and to motivate them to participate, principals and

guidance counselors presented whole school assemblies. The assemblies described the

school’s character education program, discussed examples of positive behaviors, and

offered incentives for displaying good character. Some of the incentives included

earning extra recess time, excused homework for a day, spend the day with the principal,

have lunch with the principal or a teacher of their choosing, sitting in the principal’s chair

for the day, etc. Follow-up lessons and discussions designed and provided by the

teachers were executed 2-3 times per week to reinforce the character education programs.

17

Measurement Procedures

Observations. Observations of student behaviors were made during school

visitations. The researcher would walk throughout the schools and randomly visit

classrooms to observe students’ behaviors towards one another. The researcher would

look for opportunities in which students were communicating politely, helping each other

without prompts, and treating each other with respect.

Reports. Each month, the researcher discussed any discipline reports that were

filed with the schools’ principals and guidance counselors. The researcher would ask for

the number of discipline reports that were filed to determine if the reports were increasing

or decreasing.

Data Analysis

Graphs were created to compare the effectiveness of each school’s character

education program. The graphs were measured and broken down according to grade

level. Comparisons were made based upon the pre-implementation and post-

implementation of a character education program. The graphs were analyzed to

determine if character education improves student behavior.

18

CHAPTER 4

Findings

This study utilized a single subject design and a one-shot experimental case to

evaluate the effectiveness of character education programs in grades kindergarten through

fifth across three different schools. During the baseline phase, discipline reports from

each school were examined. These reports were examined prior to the implementation of

a character education program in each school. During the intervention phase, every

classroom teacher in each of the three schools introduced the new character education

program to their students. The programs were implemented through mini-lessons, social

activities, and presentations.

Data was collected through observations of students’ behaviors. The researcher

walked throughout the schools and visited the classrooms to observe students’ behaviors

towards one another. Opportunities in which students were communicating politely,

helping each other without prompts, and treating each other with respect were traits that

were looked for. Each month, the researcher discussed any discipline reports that were

filed with the schools’ principals and guidance counselors. Discipline reports were

examined to determine if the reports were increasing or decreasing.

Results

Pre-implementation behaviors. Pre-implementation behaviors were assessed

using discipline reports provided by the schools’ principals and guidance counselors.

The scores were calculated per grade level and categorize according to consequence. For

each incident, the corresponding grade level received 1 point to indicate an incident had

19

occurred or had been reported. Table 2 provides student group data at School A for the

2016-2017 academic school year. Information has been documented according to grade

level and incidents that were reported. The reports were filed prior to the implementation

of a character education program.

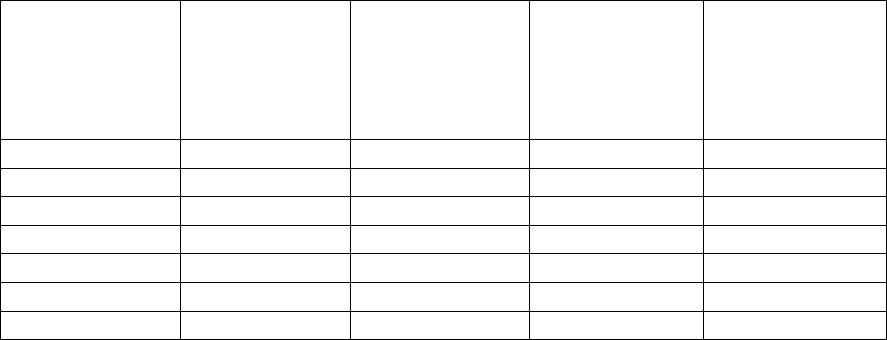

Table 3

Pre-Implementation Behaviors School A (2016-2017)

Physical fights

or attacks

Distribution,

possession, or

use of alcohol

or illegal drugs

Use or

possession of

firearm or

explosive

device

Harassment,

intimidation, or

bullying reports

or investigations

Kindergarten

7

0

0

5

First

4

0

0

6

Second

4

0

0

9

Third

6

0

0

7

Fourth

3

0

0

6

Fifth

4

0

0

7

Special Ed

4

0

0

2

Table 3 provides student group data at School B for the 2016-2017 academic

school year. Information has been documented according to grade level and incidents

that were reported. The reports were filed prior to the implementation of a character

education program.

20

Table 4

Pre-Implementation Behaviors School B (2016-2017)

Physical fights

or attacks

Distribution,

possession, or

use of alcohol

or illegal drugs

Use or

possession of

firearm or

explosive

device

Harassment,

intimidation, or

bullying reports

or investigations

Kindergarten

1

0

0

3

First

0

0

0

3

Second

4

0

0

5

Third

2

0

0

4

Fourth

2

0

0

6

Fifth

4

0

0

5

Special Ed

3

0

0

0

Table 4 provides student group data at School C for the 2016-2017 academic

school year. Similar to Tables 2 and 3, the information has been documented according

to grade level and incidents that were reported. The reports were filed prior to the

implementation of a character education program in School C.

Table 5

Pre-Implementation Behaviors School C (2016-2017)

Physical fights

or attacks

Distribution,

possession, or

use of alcohol

or illegal drugs

Use or

possession of

firearm or

explosive

device

Harassment,

intimidation, or

bullying reports

or investigations

Kindergarten

4

0

0

4

First

2

0

0

5

Second

1

0

0

3

Third

0

0

0

4

Fourth

3

0

0

2

Fifth

2

0

0

6

Special Ed

3

0

0

1

21

Intervention year 1. Post-implementation behaviors were assessed using discipline

reports provided by the schools’ principals and guidance counselors. The character

education programs were introduced, taught, and implemented for an entire academic

school year before the results were analyzed to determine their effectiveness. Similar to

the pre-implementation tables, the scores were calculated per grade level and categorize

according to consequence. For each incident, the corresponding grade level received 1

point to indicate an incident had occurred or had been reported. Table 5 provides student

group data at School A for the 2017-2018 academic school year. Information has been

documented according to grade level and incidents that were reported. The reports were

filed after the implementation of a character education program.

22

Table 6

Post-Implementation Behaviors School A (2017-2018)

Physical fights

or attacks

Distribution,

possession, or

use of alcohol

or illegal drugs

Use or

possession of

firearm or

explosive

device

Harassment,

intimidation, or

bullying reports

or investigations

Kindergarten

2

0

0

3

First

2

0

0

2

Second

3

0

0

4

Third

0

0

0

2

Fourth

0

0

0

2

Fifth

1

0

0

3

Special Ed

2

0

0

2

Table 6 provides student group data at School B for the 2017-2018 academic

school year. Information has been documented according to grade level and incidents

that were reported. The reports were filed after the implementation of a character

education program.

Table 7

Post-Implementation Behaviors School B (2017-2018)

Physical fights

or attacks

Distribution,

possession, or

use of alcohol

or illegal drugs

Use or

possession of

firearm or

explosive

device

Harassment,

intimidation, or

bullying reports

or investigations

Kindergarten

1

0

0

3

First

0

0

0

1

Second

0

0

0

3

Third

1

0

0

2

Fourth

2

0

0

4

Fifth

3

0

0

2

Special Ed

1

0

0

0

23

Table 7 provides student group data at School C for the 2017-2018 academic

school year. The information has been documented according to grade level and

incidents that were reported. The reports were filed after the implementation of a

character education program in School C.

Table 8

Post-Implementation Behaviors School C (2017-2018)

Physical fights

or attacks

Distribution,

possession, or

use of alcohol

or illegal drugs

Use or

possession of

firearm or

explosive

device

Harassment,

intimidation, or

bullying reports

or investigations

Kindergarten

0

0

0

0

First

1

0

0

2

Second

0

0

0

3

Third

0

0

0

2

Fourth

2

0

0

2

Fifth

2

0

0

2

Special Ed

1

0

0

1

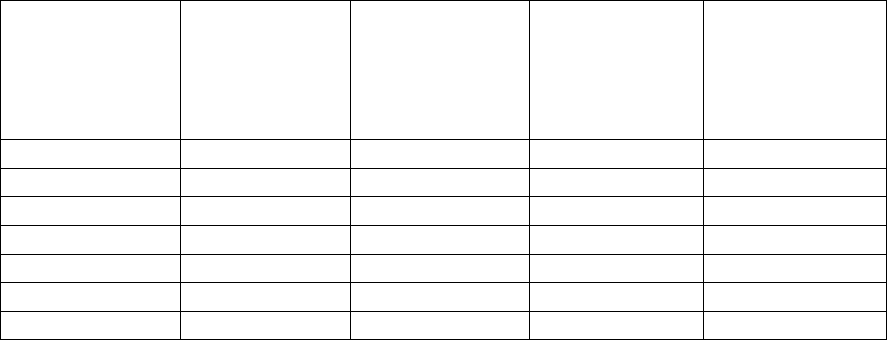

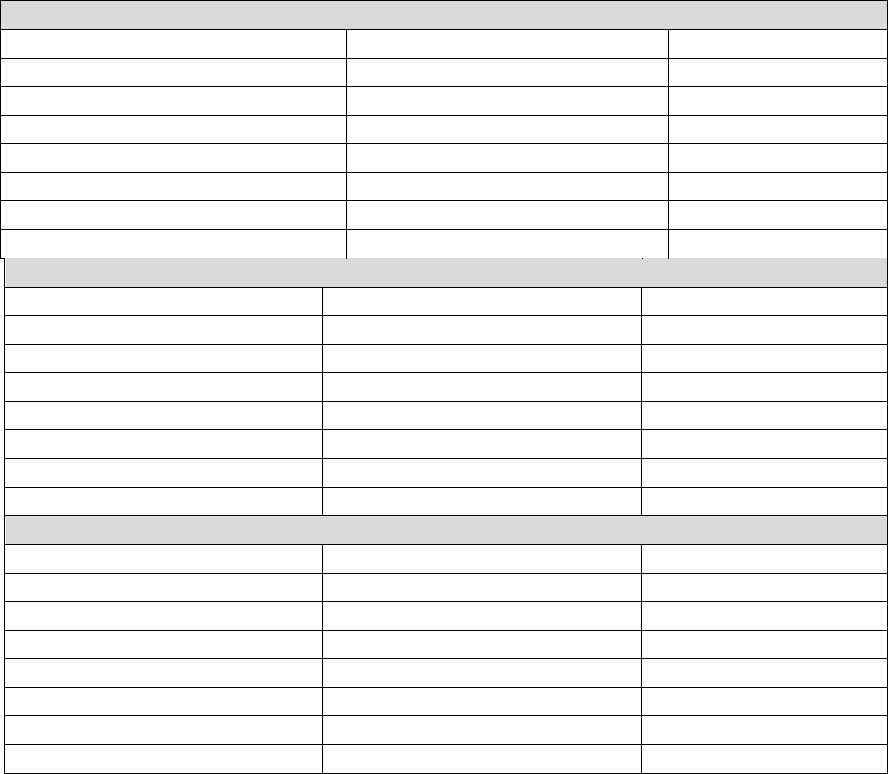

Table 8 displays a concise view of the number of discipline reports that were

filed. It compares the number of reports that were filed prior to the implementation of a

character education program to the first year a character education program was executed

within each school.

24

Table 9

Pre- and Post-Implementation

School A

Grade

Pre-Implementation

Year 1

Kindergarten

12

5

First

10

4

Second

13

7

Third

13

2

Fourth

9

2

Fifth

11

4

Special Education/Ungraded

6

4

School B

Grade

Pre-Implementation

Year 1

Kindergarten

4

4

First

3

1

Second

9

3

Third

6

3

Fourth

8

6

Fifth

9

5

Special Education/Ungraded

3

1

School C

Grade

Pre-Implementation

Year 1

Kindergarten

8

0

First

9

3

Second

4

3

Third

4

2

Fourth

5

4

Fifth

8

4

Special Education/Ungraded

4

2

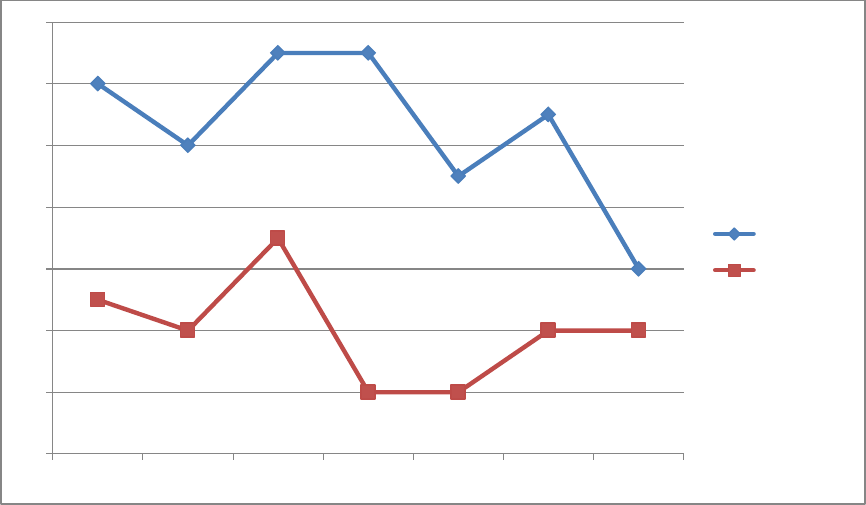

Figure 1 shows the trend of the pre-implementation and the completion of the first

year of a character education program within School A during the 2016-2017 and 2017-

2018 academic school years.

25

Figure 1. Pre-Implementation of Character Education Program for School A.

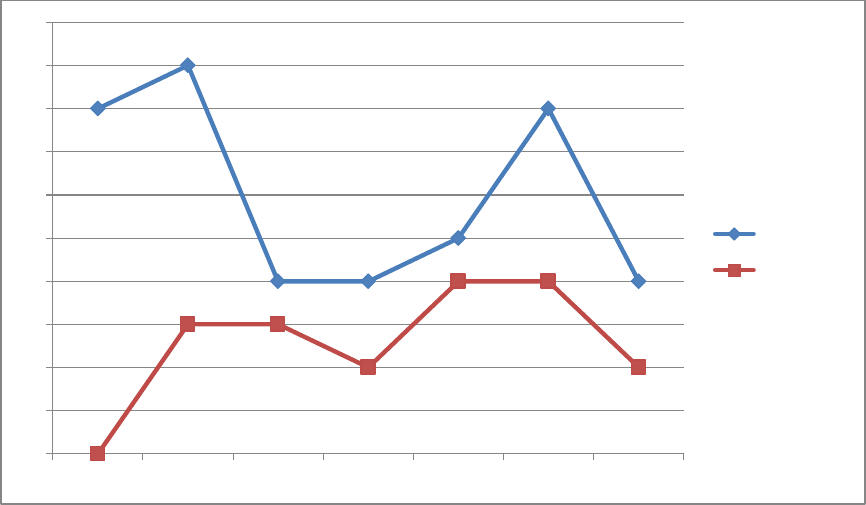

Figure 2 shows the trend of the pre-implementation and the completion of the first

year of a character education program within School B during the 2016-2017 and 2017-

2018 academic school years.

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

K First Second Third Fourth Fifth Special Ed

2016-2017

2017-2018

26

Figure 2. Pre-Implementation of Character Education Program for School B.

Figure 3 shows the trend of the pre-implementation and the completion of the first

year of a character education program within School C during the 2016-2017 and 2017-

2018 academic school years.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

K First Second Third Fourth Fifth Special Ed

2016-2017

2017-2018

27

Figure 3. Pre-Implementation of Character Education Program for School C.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

K First Second Third Fourth Fifth Special Ed

2016-2017

2017-2018

28

CHAPTER 5

Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendation

The purpose of this study was to determine if character education in school is

effective enough to positively increase students’ moral and ethical behaviors and values.

The study examined the effectiveness of character education programs in three suburban

elementary schools.

Findings

The results of the study revealed all three schools decreased in filed discipline

reports and increased in positive behaviors from the Pre-Implementation year to Year 1

of a character education program. For example, School A decreased the number of

discipline reports filed from the Pre-Implementation year to Year 1by nearly 38%.

Kindergarten went from filing 12 discipline reports to 5; First grade’s initial amount of

reports were 10 and decreased to 4; Second went from 13 down to 7; discipline reports

for Third grade began at 13 and plummeted to 2; Fourth grade had 9 and improved to 2;

Fifth grade had 11 discipline reports filed in the Pre-Implementation year and went down

to 4 filed reports in Year 1; Special Education had 6 and reduced to 4.

The results of this study corroborate with prior research that has been conducted

on the effectiveness of character education. Bulach (2018), for example, suggested

schools and school communities should be involved in a character education program,

and determined character education programs decrease bullying and incidents of violence

because students will be more sympathetic, tolerant, kind, compassionate, and forgiving

individuals. Snyder et al. (2012) reported their findings on character education. Results

determined character education showed positive effects on student achievement in

29

academics and a decrease in problem behaviors. Snyder’s findings validate the results

that were determined through this case study. Students showed a decrease in

suspensions, violence rates and bullying.

Limitations

This study had several possible limitations. One limitation may have been the

varying instruction when it came time for intervention of the character education

programs. During the intervention period, all educators were given the names of the

programs that were being used and the website or book in which they can find additional

information. However, the educators were required to find or create their own materials.

Additionally, they were to create lesson plans on how they were going to implement the

character education programs within their classrooms. These factors could have hindered

the results of the study because each educator’s instruction differed from classroom to

classroom. Furthermore, varied materials were used, making the programs’

implementation inconsistent.

The final limitation was the timeline in which the study was completed. This

study was conducted during the Fall and Spring semesters. This does not provide enough

time to truly detect the effectiveness of the character education programs. To determine

if these programs make a significant difference in student behaviors, further research

should be conducted.

Implications and Recommendations

An implication for practice includes having the teachers well trained to initiate

and follow through with the intervention of the character education programs. Teachers

should have an understanding of the programs that were being implemented within their

30

schools and know the materials and resources they have available to them. Offering

professional development opportunities for their programs would be the most effective

way to ensure teachers are properly trained and consistent in their practice.

Conclusion

The study was successful in that it revealed an increase in positive behaviors

within the elementary schools. Further research should be conducted to completely

determine the effectiveness of character education programs. Results could have been

stronger if teachers were offered additional training on how implement the character

education programs. Moreover, giving the teachers the proper materials to instruct the

students on these programs could have promoted student engagement to increase their

positive behaviors.

31

REFERENCES

Black, S. (1996). The Character Conundrum. American School Board Journal, 29-31.

Bulach, C. A. (2002). Implementing a Character Education Curriculum and Assessing Its Impact

on Student Behavior. The Clearing House, 79-83.

Character Education Manifesto. (2002). Center for Advancement of Ethics and Character.

Elias, M. J. (2009). Social-Emotional and Character Development and Academics as a Dual

Focus on Educational Policy. Educational Policy, 831-846.

Gage, N. A., & Rose, C. A. (2016). Exploring the Involvement of Bullying Among Students With

Disabilities Over Time. Sage Journals.

Lessne, D., & Yanez, C. (2016). Student Reports of Bullying: Results From the 2015 School

Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey. National Center for

Education Statistics.

Lickona, T. (1991). Educating for Character: How Our Schools Can Teach Respect and

Responsibility. New York: Bantam Books.

Pritchard, I. (1988). Character Education: Research Prospects and Problems. American

Journal of Education, 469-495.

Snyder, F. J., Vuchinich, S., Eashburn, I. J., & Flay, B. R. (2012). Improving Elementary School

Quality Through the Use of a Social-Emotional and Character Development Program: A

Matched-Pair, Cluster-Randomized, Controlled Trial in Hawai'i. Journal of School

Health, 11-20.

Sojourner, R. J. (2012). The Rebirth and Retooling of Character Education in America. Character

Education Partnership.

White, R., & Warfa, N. (2011). Building Schools of Character: A Case Study Investigation of

Character Education's Impact on School Climate, Pupil Behavior, and Curriculum

Delivery. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45-60.