University of the Incarnate Word University of the Incarnate Word

The Athenaeum The Athenaeum

Theses & Dissertations

12-2016

Values Education in Bangladesh: Understanding High School Values Education in Bangladesh: Understanding High School

Graduates' Perspectives Graduates' Perspectives

Leo J. Pereira

University of the Incarnate Word

Follow this and additional works at: https://athenaeum.uiw.edu/uiw_etds

Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, and the Social and

Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Pereira, Leo J., "Values Education in Bangladesh: Understanding High School Graduates' Perspectives"

(2016).

Theses & Dissertations

. 20.

https://athenaeum.uiw.edu/uiw_etds/20

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Athenaeum. It has been accepted for inclusion

in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Athenaeum. For more information, please contact

VALUES EDUCATION IN BANGLADESH: UNDERSTANDING

HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATES’ PERSPECTIVES

by

LEO JAMES PEREIRA

A DISSERTATION

Presented to the Faculty of the University of the Incarnate Word

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

UNIVERSITY OF THE INCARNATE WORD

December 2016

ii

Copyright by

Leo James Pereira

2016

iii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The completion of my doctoral journey has been an enriching and transcending

experience in my life. Although only the name of the doctoral student is written in the document,

a number of people and organizations generously contributed in various ways to this academic

journey. Without their help, I would not have completed the journey alone. I express

thankfulness to Dr. Absael Antelo, my academic advisor, for his guidance and availability from

the time I began doctoral studies until his retirement. He was always there to listen and help.

Even when I visited him without an appointment, he never said no. I am thankful to the faculty

members for advice on doing research, writing papers, and for guiding me through this scholarly

journey. I am thankful to Dr. Carla Zainie who spent many hours reading my dissertation drafts

and doing grammatical and linguistic editing. Her encouragement was a source of my

motivation. I sincerely thank Martha Lashbrook for editing the final product of dissertation. She

did an excellent work refining the whole document.

I also want to thank the research participants in Bangladesh who graciously provided

their time and allowed me to interview them. These individuals spontaneously and candidly

shared their experiences and perspectives about values education during their time at school.

Without their help, this endeavor would not have been possible. I am grateful to the

Congregation of Holy Cross the United States Province of Priests and Brothers at Notre Dame in

South Bend, Indiana, and Moreau Province in Austin, Texas, for their assistance with various

resources. I am grateful to St. Joseph Province in Dhaka, Bangladesh, for allowing me to

undertake this study. Support, encouragement, and assistance from these provinces made it

possible to complete this academic journey.

iv

Acknowledgements—Continued

Finally, with profound gratitude, I want to thank my dissertation chair, Dr. Sharon

Herbers, and my committee members, Dr. David Fike, Dr. Daniel Dominguez, and Dr. James

Simpson, for their unconditional support and scholarly guidance. These people inspired,

mentored, and helped me through the dissertation process to achieve my goals. An additional

thanks goes to Dr. Herbers who was instrumental in transforming me into an novice scholar. Her

wisdom and patience allowed me to have confidence in myself and make the work possible.

Thank you all for your support, supervision, and motivation. I conclude with utmost gratitude to

God for connecting every resource, defying all the odds, and enabling me to accomplish the task

and achieve the goals.

Leo James Pereira

v

DEDICATION

I dedicate this dissertation to my mother who has been an example of a virtuous woman

to me. My mother was a simple housewife, worked silently but diligently her entire life, brought

up her seven children, and took care of the whole family and the household. She lived her life

based on values and inculcated necessary values in her children. She was always attentive to

needs of her children and family. She has been always there, in both good times and difficult

times, to make sure everything was alright. She has been an icon of an exemplary woman and the

source of my inspiration and strength in everything I do in life.

I dedicate this dissertation to those people who have committed their lives to promoting

values education in educational institutions and society in Bangladesh as well as developing

curriculum and training educators to cultivate values in young learners. And I dedicate it to the

teachers who practice their values in their lives and work tirelessly to instill values in their

students.

vi

VALUES EDUCATION IN BANGLADESH: UNDERSTANDING

HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATES’ PERSPECTIVES

Leo James Pereira, Ph.D.

University of the Incarnate Word, 2016

Values education is a subject that may be neglected in some educational settings. An absence of

values education may lead to dysfunction in society. Scholars have only recently become

interested in the importance of values education (Koh, 2012). Although the National Education

Policy in Bangladesh has long emphasized the inculcation of values in educational institutions

(Ministry of Education, 1974, 2010), recent research has revealed the inadequate implementation

and practice of values education (UNICEF Bangladesh, 2009).

The purpose of this basic interpretive qualitative study was to understand the high school

graduates' perspectives regarding values education and the values they learned while attending a

Catholic Church-sponsored school in Bangladesh. The research protocol comprised

semistructured, open-ended interviews and a focus group discussion with 12 participants. The

participants were purposefully selected and were interviewed in sessions lasting 40-75 minutes.

Data was analyzed using an inductive and constant comparative process.

Analysis revealed seven values education related principal themes that were relevant to

the study’s purpose and research questions. The values education related themes were: (1)

learning specific values through relationships, (2) learning values through school culture, (3)

long-term impacts of school experiences, (4) benefits of co-curricular activities, (5) necessity of

values education, (6) school's duties in implementing values education, and (7) acquired values

vii

that conflict with societal norms. In addition, analysis also provided information about the

participants’ meaningful memories and experiences during their 8 years of schooling that

connected to learning values in school.

Five recommendations were proposed for further research to gain an in-depth knowledge

of current practices in values education: (1) duplication of qualitative research with teachers as

participants, (2) a qualitative research with female or mixed participants, (3) a similar qualitative

research with participants of general schools, (4) a qualitative study with current students as

participants to understand the current practices, and (5) a quantitative study to investigate the

correlation between learning values and co-curricular activities and school programs. Three

recommendations were proposed for the institution that the participants were associated with: (1)

the findings of this study should be shared with faculty and administration, (2) the school should

assess and explore ways to enhance cultivating values and what might be done differently in

cultivating values, and (3) efforts should be made to emphasize integrating values education into

the curriculum for inculcating values in school.

viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter Page

LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... xiii

LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................................... xiv

CHAPTER 1: VALUES EDUCATION ......................................................................................... 1

Context of the Study ........................................................................................................... 1

Colonial experience of Bengal ................................................................................ 2

Crisis of values ....................................................................................................... 4

Statement of the Problem ................................................................................................... 5

Researcher's Personal Background .................................................................................... 6

Purpose of the study ........................................................................................................... 8

Necessity of values education ............................................................................................ 9

Research questions ............................................................................................................ 10

Overview of Research Methodology ................................................................................ 10

Definition of Values Education .........................................................................................11

Overview of Theoretical Framework ............................................................................... 12

Significance of the Study .................................................................................................. 12

Limitations of the Study ................................................................................................... 13

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 13

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................................... 15

Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 15

ix

Table of Contents—Continued

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

Kohlberg's Theory of Moral Development ....................................................................... 15

Historical Overview: Bangladesh and Education ............................................................ 19

British regime (1757–1947) ................................................................................. 19

Pakistan regime (1947–1971) .............................................................................. 21

Bangladesh era ..................................................................................................... 21

Values, Education, and Values Education ....................................................................... 27

Values ................................................................................................................... 27

Education .............................................................................................................. 28

Values education ................................................................................................... 28

Global need of values education ........................................................................... 30

Diversity in values ................................................................................................ 30

Core values ........................................................................................................... 31

Social and cultural values ..................................................................................... 33

Values education and school ................................................................................ 34

Values education and teachers ............................................................................. 35

Values education and cocurricular activities ........................................................ 36

Values education: A generic perspectives ............................................................ 37

Bangladesh’s cultural traits .................................................................................. 38

Values education in Bangladesh .......................................................................... 39

Educating minds and hearts .................................................................................. 41

Conclusion ....................................................................................................................... 41

x

Table of Contents—Continued

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 43

Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 43

Research Approach and Rationale .....................................................................................43

Research Design .............................................................................................................. 44

Protection of Human Subjects .......................................................................................... 45

Setting of the Study ......................................................................................................... 45

Research participants ....................................................................................................... 47

Research Instruments ....................................................................................................... 49

Data Collection Procedures .............................................................................................. 50

Interview protocol and questions ......................................................................... 50

Focus group interview .......................................................................................... 51

Data analyses Process ...................................................................................................... 52

Trustworthiness and Credibility ....................................................................................... 54

Researcher's bias ................................................................................................... 55

Triangulation ........................................................................................................ 55

Conclusion ....................................................................................................................... 56

CHAPTER 4: RESEARCH FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS ....................................................... 57

Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 57

Researcher's Field Experience ......................................................................................... 57

Findings ........................................................................................................................... 59

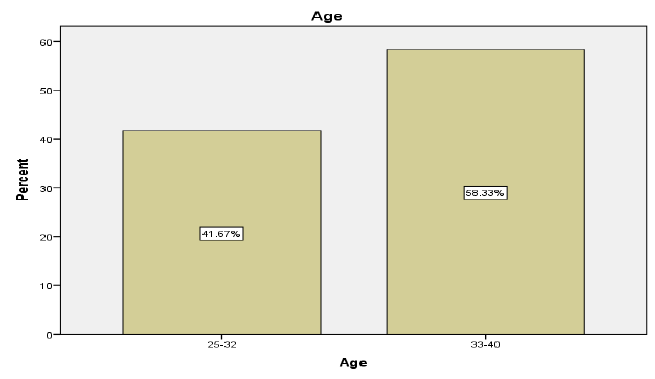

Description of participants ................................................................................... 59

Themes ................................................................................................................. 66

xi

Table of Contents—Continued

CHAPTER 4: RESEARCH FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

Summary of focus group interview .................................................................... 92

Analysis of written documents' analysis ........................................................... 95

Acquired values through theoretical lens ........................................................... 97

Summary and Conclusion .............................................................................................. 101

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION, CONCLUSION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS ..................... 103

Introduction .................................................................................................................... 103

Overview of the study .................................................................................................... 103

Findings Linking Current Research ............................................................................... 104

Learning specific values through relationships ................................................... 104

Learning values through school culture .............................................................. 107

Long-term impacts of school experiences .......................................................... 109

Benefits of cocurricular activities ....................................................................... 110

Necessity of values education ............................................................................. 111

School's duties in implementing values education ............................................. 112

Acquired values that conflict societal norms ...................................................... 116

Acquired values through theoretical lens ............................................................ 117

Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 118

Implications .................................................................................................................... 120

Recommendations .......................................................................................................... 122

Researcher's Reflection .................................................................................................. 124

xii

Table of Contents—Continued

REFERENCES .......................................................................................................................... 126

APPENDICES ........................................................................................................................... 137

Appendix A: Map of the Indian Subcontinent ............................................................... 138

Appendix B: Bangladesh’s Education Structure ........................................................... 139

Appendix C: Core and Related Values .......................................................................... 140

Appendix D: Institutional Review Board (IRB) IRB Approval Letter ......................... 141

Appendix E: Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approval Letter for Revisions ............ 142

Appendix F: Consent form to Participate in a Research Study ...................................... 143

Appendix G: Semistructured Questions for Individual Interviews ............................... 145

Appendix H: Semistructured Questions for Focus Group Interview ............................. 146

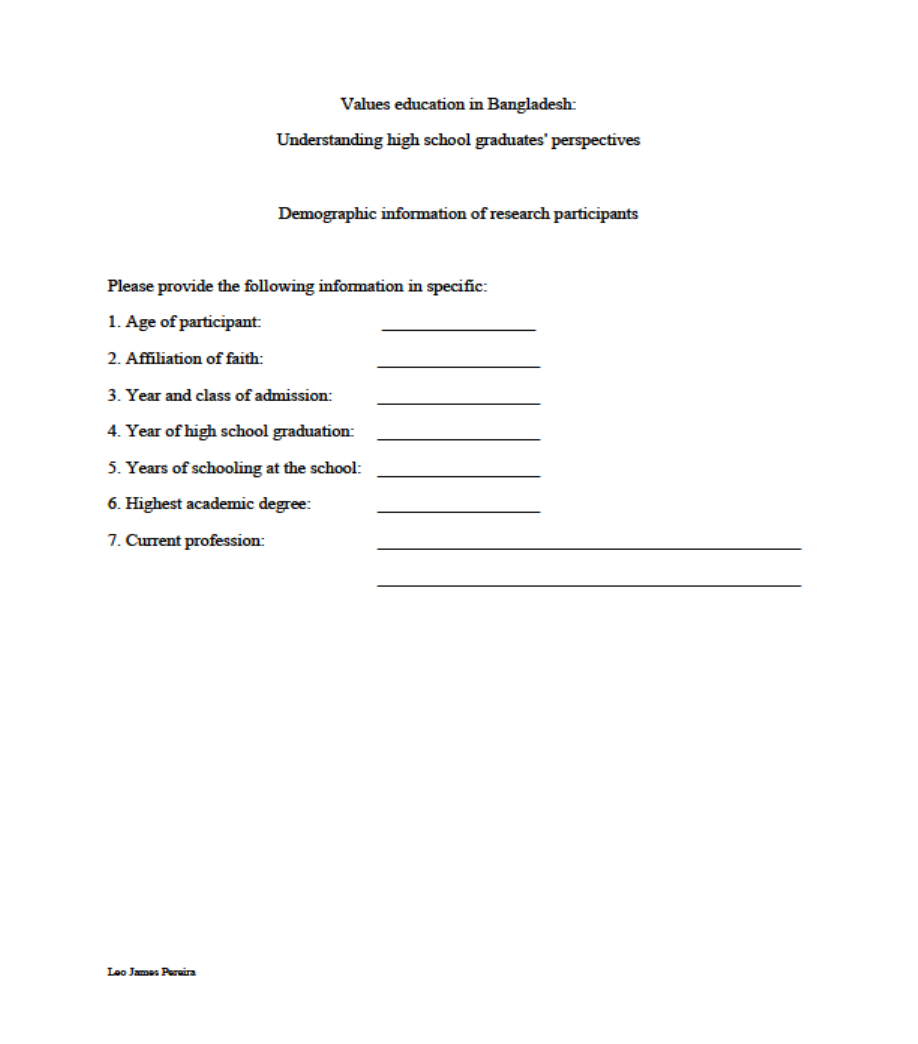

Appendix I: Demographic Survey .................................................................................. 147

xiii

LIST OF TABLES

Table Page

1. Levels and Stages of Kohlberg's Cognitive Developmental Theory ........................................ 16

2. Participants' Religious Affiliation ........................................................................................... 61

3. Participants' Academic Degrees ............................................................................................. 61

4. Learned Core Values ............................................................................................................... 72

5. Learned Shared Values ............................................................................................................ 74

6. Long-Term Impacts of Values ................................................................................................. 80

7. Cocurricular School Activities ................................................................................................. 83

8. Benefits from Cocurricular Activities ...................................................................................... 84

9. Significance of Values Education ............................................................................................ 87

10. School's Duties in Implementing Values Education .............................................................. 89

11. Acquired Values Through Theoretical Lens in Developmental Stages .............................. 99

xiv

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure Page

1. Triangulation of data ................................................................................................................ 55

2. Percentage of participants in each age group ........................................................................... 60

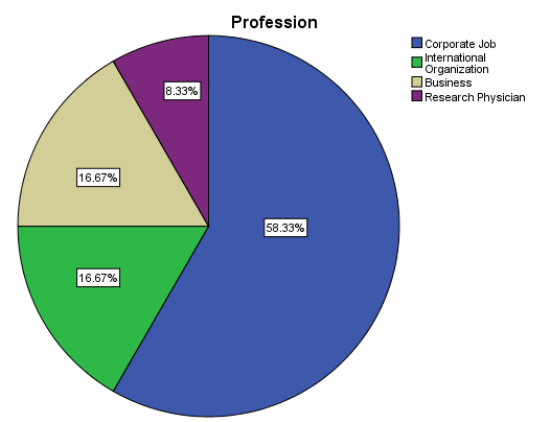

3. Percentage of participants in each professional category ........................................................ 62

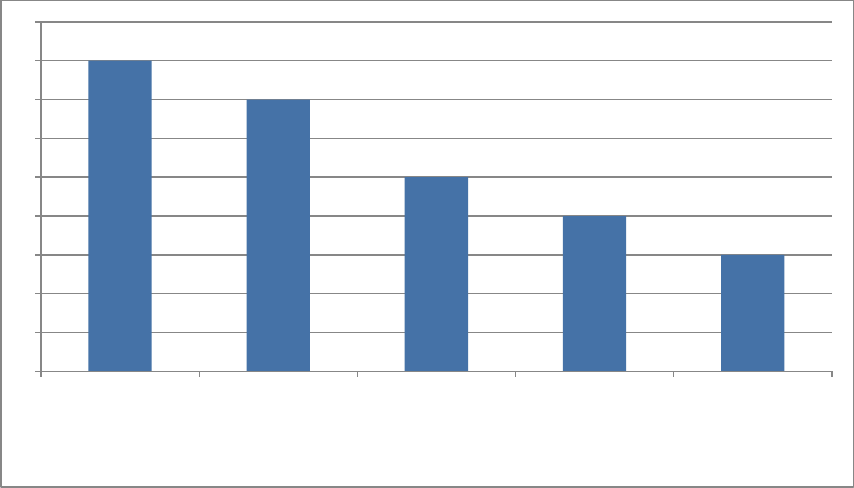

4. Specific values learned in school based on the responses of 11 participants.

Participants mentioned more than one value ........................................................................... 68

5. Ways of promoting and inculcating values based on the responses of 11 participants.

Participants mentioned more than one way ...............................................................................76

1

Chapter 1: Values Education

Context of the Study

According to Moreau (2011), “society has a greater need for people of values than it has

for scholars” (p. 1). Moreau wrote this statement on Christian Education for the educators of his

congregation in 1856 (Moreau, 2011). While serving and educating the youths in France during

the post revolution era, the members of the Congregation of Holy Cross observed the deficiency

of moral and Christian values in society. When teaching, they attempted to develop academic

excellence as well as cultivate values and believed positive values could influence knowledge for

better use. Missionaries of the Holy Cross Congregation began to work in Bengal in 1853, and

focused their efforts on educating the native people (Catta & Catta, 1943; Rodrigues, 2009).

At that time, Bengal was under British rule with a British educational system. The Indian

subcontinent (India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan) was a British colony from 1757 to 1947. Thomas

Macaulay joined the governor general's council as a law member in 1835. Macaulay met with the

regime's officers and local educators and stated that “Britain's mission was to create not just a

class of Indians sufficiently well versed in English to help the British rule their country, but one

'English in taste, in opinions, in morals and in intellects’” (Metcalf & Metcalf, 2006, p.82). The

meeting's minutes clearly mentioned the ultimate purpose of colonial education for the local

peoples. Although the British regime introduced secular and modern education to the Indian

subcontinent, their intention was not to improve the local education system, but to prepare a

native administrative class who could help the regime rule the native people. Certainly, the

British education system did not aim for improving the local people’s quality of life, creativity,

or self-reliance (Basu, 1867; Metcalf & Metclalf, 2006).

2

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

(UNESCO, 1994), education is one of the fundamental rights of all people irrespective of creed,

culture, or gender. All people have a right to education and through it to acquire knowledge,

skills, and values. One of the goals of education is to develop and impart universal, cultural and

moral values to students. It is through cultural and moral values that individuals find their

uniqueness and significance in society. Basic education is not only, a goal but also a way to

transform citizens into lifelong learners. The International Bureau of Education (IBE, 2011) and

UNESCO (1994) not only, affirmed that education is a basic right for everyone, but also

emphasized the importance of cultural and moral values of education and promoted the concepts

of global citizenship education––peace, tolerance, mutual understanding, and human rights-

related educational contents.

Conversely, in Bangladesh the colonial characteristics of education carried on, rooted

deeply in the lives of the people, and embedded in their attitudes and systems of the country. In

spite of being an independent country for decades, newer approaches to education could not

completely eliminate the colonial characteristics from education, nor could the newer approaches

liberate people from colonial thinking or make education creative and self-reliant (Basu, 1867;

Metcalf & Metcalf, 2006).

Colonial experience of Bengal. Bangladesh (ancient Bengal) went through an extensive

period of colonial rules and experiences inflicted by the discriminatory colonial policies.

Buddhist and Hindu rulers governed the territory beginning in the second millennium; Muslim

invaders ruled in the 12th century, Mughals began their rule in 1576, the British in 1757, and

Pakistan dictators in 1947. During these eras, people experienced an indigenous education

system during the early period of Indian, an Islamic education during the medieval period, and

3

an imperial education during the British era (Ali, 1999; Basu, 1867; Khan, 2011; Schendel,

2009). British policy makers designed an education policy for local people that eventually

created loyal natives who they could easily control and use to manage their own British trades

and administration. The British education policy also polarized the native people into an elite

class who worked for the regime and the masses whom they suppressed using the elites. The

British education policy aimed to deprive the natives socially, politically, and academically, and

it implemented this successfully (Waseem, 2014). In educating the natives, the regime

emphasized English literature, the English language, and Western education and provided

financial assistance to those institutions who embraced Western education accordingly. In doing

so, the regime neglected the local culture, languages, traditions, and religion-based indigenous

education. This approach affected many local traditional educational institutions and caused

them to shut down. The British regime used a tactic "divide and rule" to control and manipulate

the local people. In this way, the regime created new classes among the locals based on Western

education, loyalty, and religions (Ali, 1999).

Among all the colonial rulers, the British regime was the most systematic and impactful,

inflicting discriminations and divisions into every corner of the country, the economy, the culture

and religions, and education (Khan, 2011). Even after independence, Bangladesh retained the

British colonial education system and its aims. For many decades, this system emphasized

preparing students only for passing examinations, for low-skilled labor, and had little practical

significance. Secondary education was to prepare students with necessary skills and qualities for

professional study and life. However, a poor design, a mismanagement of resources, and an

irrelevant curriculum in secondary education hampered achieving these goals. Many students

4

failed to succeed and qualify for jobs (Ilon, 2000); conversely, it prepared people for low-skilled

jobs for being dependent, and not for excellence in life (Barua, 2007).

Crisis of values. Wars, violence, terrorisms, and political and religious hostilities seem

common realities around the world and the people are facing them every day in their lives

(Cubukcu, 2014). In past decades, criminal activities in modern society, ethical misconducts, and

unethical activities in academic institutions, including bullying, became grievous concerns within

and beyond educational institutions. Academic dishonesty, plagiarism, and cheating occurred

frequently in educational institutions in the South Asian region. Various types of academic

dishonesty during public and private examinations indicates the lack of morality formation of

students. This situation indicates the need to emphasize values education. These incidents and

situations motivated scholars and educators to discuss the topic of moral and values education in

educational institutions (Koh, 2012). Values education instills particular moral, ethical, cultural,

social, and spiritual values in children that are needed for their overall development. It also

develops character and the personality of individuals (Awasthi, 2014). Values and moral

education seems to be an important component in forming youths into responsible and concerned

citizens of the world (Cubukcu, 2014).

In Bangladesh, academic dishonesty in the form of leakage of questions of various public

examinations, cheating on tests, forging academic certificates and scholarly papers continued as

severe problems. Memorization and obtaining better grades were two of the main features of the

education system, which have persisted into the present. Students cheated and did almost

anything to obtain better grades (Lawson, 2001). Students of one university cheated on

examinations, and the authorities punished them with expulsion. Dhaka University authorities

annulled the doctorate degree of a faculty member for using fraudulent information in a doctoral

5

thesis (“DU Syndicate Suspends 102 students,” 2015). BBC News reported that in India, gross

cheating in public examinations became a matter of grievous concern (“India Students Caught

‘Cheating,’” 2015). The government alone could not stop it. Students, parents, and the

community at large needed to stand up and help stop the cheating.

For many years, Bangladesh's government tried to address these problems (Lawson,

2001). The Hamdoor Rahman Commission report of 1964, the Kudrat-E-Khuda Commission of

1974, and the National Education Commission report of 1988 stated grievous concerns about

cheating, malpractices, and corruption on examinations. The reasons for this continuous cheating

on public examinations were attributed to socio-economic and political factors, lack of

commitment and lack of values in various stakeholders in society (“Cheating in Public

Examinations,” 2001).

Statement of the Problem

In Bangladesh, the leaking out examination questions, cheating on exams, and forging

academic certificates and scholarly papers continued to exist for many years (“DU Syndicate

Suspends 102 Students,” 2015; Lawson, 2001). Cheating and forging indicated lack of respect

towards rules, policies, professions, and other individuals as well as dishonesty. Sharma (2014)

argued that society was suffering from a values crisis. The increasing level of violence and the

erosion of values had an impact on the everyday lives of many people. Disharmony grew

unobstructed and it caused an increase in frustration, hatred, and selfishness in society, especially

among youths. The gradual deterioration of values and the increase of violence based on cult and

religions have infected and affected educational institutions severely.

Sandeep (2016) and Sharma (2014) pointed out that deficiency of moral and spiritual

values was a grave crisis in society. Pride, selfishness, ego, desires, and hypocrisy, along with

6

lack of righteousness, compassion, gratitude, love, and affection deformed the society and

people's lives. Sandeep and Sharma continued that in this modern era, it seemed extremely

necessary to create a balance between knowledge, technology, religions, and humanity and

humanism.

In order to resolve the values crisis, the National Education Commission proposed to

integrate values and character education into the national education policy (Ministry of

Education, 1974). Furthermore, the National Education Policy of 2010 emphasized teaching

human values to students in all levels and added moral education with religious studies as a

subject (Ministry of Education, 2010). Both of these education policies aimed to inculcate moral,

cultural, and social values in individuals, in society, and at the national level. Even so, other than

producing the national education policies, the Ministry of Education did not do much regarding

inculcating values, morals, and ethics in students. Although the national education policy highly

emphasized inculcation of values in school, it was unknown what values students learned in

schools and the impact of those values in their lives. It was unknown how effective the national

education policy was on teaching values at the institutional level. These uncertainties formed the

need for this study. This study investigated what values high school graduates learned in a school

in Bangladesh and how these values have influenced and impacted their life experiences.

Researcher’s Personal Background

Although national education policies, various professionals, scholars, and entities

expressed a need for implementing values education in schools, in reality, current practices in

education sectors and educational institutions are different than the aims and expectations written

in the national education policies. I worked for 12 years as teacher in Grades 1 to 10 and 9 years

as an administrator in three to 12 Catholic Church-sponsored semiprivate schools in Bangladesh.

7

Semiprivate schools are registered under the Ministry of Education, and the ministry pays part of

the faculty salary, while the private sector administers the schools. I gained experiences working

with students, teachers, parents, government, and nongovernmental agencies in the areas of

curriculum and values education. Though national education policies included values education

as part of their aims and objectives, the curriculum did not incorporate values education as a

subject or course, nor was values education incorporated into textbooks until 2010. As a result,

educational institutions did not teach values education. Based on my experience, I observed that

students lacked interest and motivation to learn values or related tasks. Since values education

was not a part of the curriculum, students’ attitudes toward it was, “Why should we study values

education since it is not going to be graded?” Teachers faced difficulties in teaching and

discussing values in class due to a lack of attention and students’ cooperation. Students studied

primarily for better grades and seemed willing to do anything to achieve high grades and good

results. As an administrator, I conducted assemblies and spoke to the students about values and

quality education to motivate them but they were not attentive nor interested in learning about

values. Rather, they were more curious about various forms of academic and nonacademic

malpractices.

Yet, other experiences attracted my attention. While working in schools, I came across

many graduates (former students) who shared their stories of school life and of learning lessons

for life. Many former students claimed that whatever they became after graduating was because

of the school and their teachers; hence, they were grateful to the school and their teachers for

their learning. These contrasting points of view between the existing students and the graduates

encouraged and motivated me to understand the high school graduates’ perspectives regarding

values education.

8

Purpose of the Study

Maharajh (2014) revealed that parents were not involved in cultivating values in their

children. Because of this situation, schools were required to be more responsible and to take

additional steps in teaching values through values education. In the South Asian countries,

parents’ seemed less interested in instilling values in students. Snarey and Samuelson (2008)

studied the developmental view of moral education and found that children could think critically.

Children had abilities to make sense of experiences occurring in their lives. This only meant that

teachers were creating an environment that inspired each child to continue in their natural

advancement of moral decision making and enhancing their educational experience.

The Catholic Church came to Bangladesh (then Bengal) in the 16th century. One of the

main missions of the Catholic Church is to educate local people through educational institutions.

The Church has a strong influence in the country for imparting education that transforms the

lives of many students who attend church-sponsored educational institutions. In Bangladesh, the

Catholic Church is recognized for its effective administration in educational institutions,

rendering quality education, and contributing in the education sectors (Rodrigues, 2009).

Educational institutions are a vital part of a nation, and education is an assessor of its values

system. These institutions are charged with disseminating the nation’s tradition, culture, and

values (Sharma, 2014).

The purpose of this study was to understand the high school graduates' perspectives

regarding values education and the values they learned while attending a Catholic Church-

sponsored school in Bangladesh. This study focused on a selected group of former students who

had graduated not only from the high school but also from a university.

9

Necessity of Values Education

Realizing the utmost need of education, the Bangladesh Constitution decreed that the

state was responsible for providing free, compulsory, uniform, and universal education for all

citizens. Education would prepare its citizens properly and motivate them to serve the needs of

the society (Bangladesh’s Constitutions, 1972). Values education was the fundamental

component of education. Hence, education seemed an appropriate means to instill values in

students. Values education provided opportunities for developing various talents and skills in

students, and enhance them (Chareonwongsak, 2006).

In 1974, the first Education Commission report in independent Bangladesh also called for

the formation of character of all students. According to that report, one of the main aims of

education in the country was to form the character of pupils through inculcating values.

Teachers, parents, and educational institutions needed to work together in schools and homes to

instill values such as honesty, impartiality, diligence, sympathy, truthfulness, sense of fairness,

sense of responsibility, orderly behavior, readiness, patriotism, enlightened citizenship,

humanism, and common welfare, and to teach values, by examples, within the teaching

curriculum, and in academic, and co-curricular activities (Ministry of Education, 1974).

Similarly, the Bangladesh National Education Policy of 2010 clearly emphasized values

education. A principal aim of National Education Policy was inculcating human values, which

guided the entire policy. The education policy encouraged educators to search for ways to

cultivate values and qualities, and prepare enlightened, rationale, and ethical citizens to love and

serve the country. Curriculum included religious and moral science lessons to facilitate the

formation of students' moral character and human values (Ministry of Education, 2010).

10

Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to understand high school graduates' perspectives

regarding values education and the values they learned while attending a Catholic Church-

sponsored school in Bangladesh. In order to understand the graduates’ views regarding values

education in school and collect information, two research questions were developed:

1) What are the high school graduates’ perspectives of the values learned in a high

school in Bangladesh?

2) How have these values influenced the graduates’ life experience?

Data were collected through semi-structured individual face-to-face interviews and a focus group

interview. During the interviews, the high school graduates shared their views and experiences

about values education, values learned in school, and how these values influenced their lives

after graduating from high school.

Overview of Research Methodology

In view of the purpose, this study used a basic qualitative research approach. Qualitative

research is engaged in understanding, exploring, and analyzing the ways individuals make

meaning of her or his own reality interacting with related surroundings (Merriam, 2002; Yin,

2002). The world holds a myriad of realities that constantly changes. In basic interpretive

qualitative research, the researcher aims to understand the experience of an individual in a

particular action and setting, how that individual makes meaning of the reality. Basic interpretive

qualitative research is also interested in understanding how an individual makes sense of a

situation or trend. In basic interpretive qualitative research, the researcher is an instrument;

meaning is constructed inductively in a descriptive manner incorporating the views and

worldviews of the participants (Merriam, 2002).

11

Definitions of Values Education

In order to understand the perspectives regarding values education, it was necessary to

define values and values education. Values means importance, degree of excellence, something

(as a principle or quality) intrinsically valuable; a collection of principles or standards of

behaviors considered desirable and significant, and held in high regard by in which a person lives

(Ignaciamuthu, 2013). Values are understood as principles, fundamental convictions, ideals,

standards or life stances that function as a guide to behaviors or for making decisions or

assessing of beliefs or actions, including those associated with personal integrity and identity

(Halstead, 1996). Values seem something precious and worthwhile; therefore, one will

spontaneously suffer and sacrifice to acquire those values (Ignaciamuthu, 2013).

In addition, according to Saldaña (2013), the word ‘value’ comprises three components:

value, attitude, and belief. Value means the significance attributed to oneself, another person,

thing, or idea. Attitude means the way one thinks and feels about themselves, another person,

thing, or idea. Belief means part of a method, which embraces ones values, attitudes, and

personal knowledge, experiences, opinions, prejudices, morals, and other interpretive

perspectives of society.

In a similar way, values education is defined as an explicit effort to teach values that

students nurture and that are held important or identified by the school (Zbar, Brown, Bereznicki,

& Hooper, 2003). Values education also includes all formal and informal ways of teaching and

inculcating values in school (Maharajh, 2014). Furthermore, values education is the formation of

a student’s mind and heart. Positive values are capable of influencing knowledge and are utilized

it for the good of society (Moreau, 2011). In this study, the research participants, based on their

12

experiences and practice in life, considered certain behaviors, qualities, and life-skills as values

that made their life significant and efficacious.

Overview of Theoretical Framework

Snarey and Samuelson (2008) in their cognitive developmental approach to moral

education stated that a child has the ability to think critically. In fact, the child takes part in

constructing and making sense of her or his world. Teachers are responsible for providing

support and creating an environment that allows the child to nurture his or her normal moral

development. In this cognitive developmental approach (Fleming, 2006; Kohlberg, 1981; Snarey

& Samuelson, 2008), Kohlberg (1981) presented three levels and six stages of moral

development. In the pre-conventional level, a person is primarily self-centered and does things to

avoid punishment or maximize gains. In the conventional level, a person looks to a group, an

institution, and society for guidance as to what is right or wrong. This stage embraces multiple

characteristics of making moral choices. In the post conventional level, a person embraces

collective perspectives and thoughts about right moral actions as opposed to a general set of

moral values and principles. This study focused on the stages of moral development.

Significance of the Study

Maharajh (2014) indicated that fewer families and parents are participating in cultivating

values in children. For this reason, schools are taking up additional responsibilities for instilling

values among students through values education (Maharajh, 2014). On the other hand, it is

believed that children have the ability to think critically and to construct sense of their realities.

Teachers’ responsibility is creating an environment where students can think naturally, make

moral choices, and improve their educational experiences (Snarey & Samuelson, 2008).

13

This study focused on a selected group of high school graduates and their perspectives

about values education, their experiences of learning values at school and the impact those

values had in their lives. The findings of this study can be an example of the benefits of learning

values in school. Furthermore, this study may inspire other schools, particularly the participants’

school and its teachers, to assess their current school activities and programs and to evaluate their

roles in cultivating values in students. Interestingly, this study revealed that although values

education was not taught in the school, the participants still learned certain values through their

co-curricular activities. This finding indicates the significance and effectiveness of co-curricular

and extracurricular activities in school. The knowledge of this study will be added in the

literature of values education.

Limitations of the Study

This was a basic interpretive qualitative study. The study focused on the perspectives of a

high school graduates regarding values education. The participants were the students of a school

sponsored by the Catholic Church in Bangladesh. Thus, in this study, the participants and their

perspectives did not represent high school graduates of non-Catholic Church-sponsored schools.

In this study, the participants were male and reported their perspectives only. In addition, the

participants’ memory seemed to be a limitation. Since, the participants graduated from the school

between 1993 and 2003, it is possible that they did not recall and express everything that

happened while in school.

Conclusion

Current realities around the world indicate clearly that society needs people with values

(Sharma, 2014). Values and morality are a global need for all time. The historical context of

Bangladesh reveals the necessity of values education. Even so, current practices in education

14

sectors of the country do not ensure cultivation of values in students. On the other hand, the

current trends that comprised market, diploma, and job-orientated education became an

obstruction to quality and value-based education. Students, parents and teachers seemed inclined

to academic achievement than formation of character and personality. Failing to integrate values

in education would hamper the right education—educating for life (Awasthi, 2014).

15

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to understand the high school graduates’ perspectives

regarding values education and the values they learned while attending a Catholic Church-

sponsored school in Bangladesh. To begin, it is necessary to understand the factors, including

historical, colonial, political, cultural, educational, and deficiency of values and moral

components that contributed to the formation of values and moral education perspectives and

experiences of the high school graduates. Existing knowledge relevant to values and values

education deepens and enriches the understanding of this subject and other entities related to

teaching and learning values in an institutional setting. This chapter includes a discussion on the

following topics: (1) Kohlberg's cognitive developmental theory, which this study used as a lens

to look at values education; (2) a brief historical overview of Bangladesh and its education

system; and (3) values, education, and values education related sub topics.

Kohlberg's Theory of Moral Development

Kohlberg (1981) developed the cognitive developmental theory to moral education.

Recent research indicates that a key uniformity of moral character shows a gradual development

in the formation of intellectual principles that allows for a person to make moral judgments and

decisions. This approach is recognized as cognitive since it acknowledges that moral education

comes into play when a child uses his or her critical thinking skills to consider moral matters and

make moral decisions. A principal aim of education is the intellectual and moral development of

a person. Education creates an atmosphere in school where ethical and psychological principles

can function to develop to their highest manner and build character. Likewise, a child's thinking

16

faculties begin to exercise as basis to deal with moral matters and decisions (Kohlberg, 1966,

1975; Snarey & Samuelson, 2008).

The approach is called developmental as it perceives the aims of moral education like

movement through different moral stages (Kohlberg, 1975). In this developmental approach

(Fleming, 2006; Kohlberg, 1981), moral perceptions advanced to a higher understanding of the

issues regarding equity as the person moves through the different levels and stages. According to

Snarey and Samuelson (2008), Kohlberg perceived children as moral philosophers as they could

think critically and had the ability to create meaning of their own experiences in a sensible way.

Therefore, the teachers’ responsibility was to create an environment that encouraged normal

advancement of moral decision-making and offered a morally enhanced educational experience.

Kohlberg (1975, 1981) and Kohlberg and Hersh, (1977) stated the development of moral

decision-making progressed through three levels, and each of level consisted of two stages (see

Table 1):

Table 1: Levels and Stages of Kohlberg's Cognitive Developmental Theory

Levels

Stages

1. Pre-conventional:

Consequences of action

1. The Punishment and Obedience orientation

2. Satisfying one's own needs and occasionally the needs

of others orientation

2. Conventional: Conformity

to personal expectations and

social order, and loyalty to it

3. The Interpersonal relationships Orientation

4. Authority and social-order maintenance orientation

3. Post-conventional: Personal

and idealized principles

5. The social contract orientation – mutually beneficial

for all citizens

6. Conscience and universal-ethical-principle orientation

Note: Adapted from "Piaget, Kohlberg, Gilligan, and others on Moral Development" by J. S. Fleming, 2006.

Retrieved from http://swppr.org/Textbook/Ch%207%20Morality.pdf. And from "The cognitive-developmental

approach to moral education" in P. K. Smith & A. D. Pellegrini (Eds.), Psychology of Education: Major Themes –

The School Curriculum (Volume III), New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. And from The Philosophy of Moral

Development: Moral Stages and the Ideas of Justice (Essays on Moral Development, Volume 1), by L. Kohlberg,

1981, New York, NY: Harper & Row.

17

In general, Kohlberg's stages of moral development illustrate the gradual advancement in the

process of moral thinking and decision making as people advance through these stages.

According to Fleming (2006), achieving the postconventional level, Stages 5 and 6, is rare, even

for adults.

According to Snarey (1985), Kohlberg claimed his theory was cross-cultural and

universal. This claim of universality sparked a lot of debate and dispute (e.g., Parik, 1980;

Simpson, 1974; Kurtines & Gief, 1974). Al-Shehab (2002) stated that a large number of studies

following Kohlberg’s method and model were conducted in Western contexts and very few

studies were done in Muslim, Middle Eastern, and Asian contexts. Al-Shehab’s study, conducted

with faculty members at Kuwait University, did not seem to support Kohlberg’s claim of

universality. His findings also indicated that the use of cognitive approach of moral reasoning for

a sample of Middle Eastern Muslim faculty members was inadequate for claiming it cross-

cultural.

Similarly, Dien (1982) conducted an analysis of Kohlberg’s studies in a Chinese context,

claiming that Kohlberg's theory was culturally biased. Dien explained that the Chinese culture

has a strong collectivistic orientation. The Chinese practice Confucianism as a moral scheme,

which emphasizes harmony, reconciliation, collective decision-making, and a sense of balance in

affairs of daily life. These characteristics are not found in Kohlberg’s cognitive developmental

theory. Therefore, a strong doubt has overshadowed the applicability of Kohlberg’s theory of

moral development in cross-cultural settings.

On the other hand, Snarey (1985) looked at studies that used Kohlberg's cognitive

developmental approach and supported the claim that moral development was universal and was

applicable in cross-cultural settings. The cognitive developmental approached followed parallel

18

ethical principles in all cultural settings. In this study, Snarey (1985) administered a thorough

examination on the empirical evidences that followed Kohlberg’s model and method to check the

cross-cultural and universality claim. The author studied and reviewed 45 studies of moral

development (38 cross-sectional and seven longitudinal) administered in 27 countries over a 15-

year span. The study revealed that Kohlberg’s interview protocol was rational and culturally fair,

because the studies used research procedures that adapted to the local situations and the

interviews were conducted in the participants’ native language and settings. Snarey found that,

based on the participants’ age, sample size, and population used in the studies, Stages 1 to 4 were

basically universal and cross-culturally appropriate, whereas Stages 5 and 6 were less or not at

all. Even so, Snarey pointed out that universality claims attracted criticism, arguing that

universality and cross-cultural evidences were inconsistent with empirical studies and inadequate

too. Edwards (1986) further argued that Kohlberg's theory and method did not incorporate

adequate cultures and ethnicities for understanding how human beings make moral decisions.

Certainly, Kohlberg's theory provided one effective strategy to study the development of moral

decision-making. And Kohlberg's works' shortcomings and criticisms should not undervalue its

noteworthy achievement.

Insofar, no empirical study using Kohlberg’s cognitive developmental approach was

found in the context and cultural settings of Bangladesh. Hence, Kohlberg’s theory may not be

directly applicable to this study, but the principles, characteristics, and underlying compositions

of his theory guided this study as a theoretical lens. This study used some key principles and

characteristics of levels and stages of moral development that were grounded in a values learning

process, both formal and informal.

19

Historical Overview: Bangladesh and Education

For this study, it was necessary to understand the historical context of Bangladesh.

Schendel (2009) stated that before 1971, Bangladesh was known as East Pakistan, prior to that,

as Bengal or Eastern Bengal. Bangladesh was one of the largest deltas in the world. Water

flowing from the mountain ranges of the Himalayas created many rivers and rivulets—for

example, Padma, Meghna, Jamuna, Brahmaputra, and so forth —which flowed through and

around Bangladesh and finally into the Bay of Bengal. Over the ages, this flow of water

deposited a huge amount of silt that created the delta, which is now Bangladesh. Due to this rich

deposit of silt, the land of Bangladesh is very fertile. Characteristics of the deltaic environment

influenced the formation of character and culture of the people of Bengal.

Schendel (2009) further stated that Bangladesh was an open network for trade,

pilgrimage, political alliance, cultural exchange, and travel for the people of close and far lands.

Portuguese traders came to Bangladesh for business in 1520. Eventually, the Portuguese

established the first European settlement in 1580, followed by the Dutch in 1650, the English in

1660, and the French in 1680. The activities of European settlements influenced and broadened

to economics, to politics, and to religion. Residents then began to take on Islamic and Christian

identities.

British regime (1757–1947). In the beginning of the second millennium, the Indian

subcontinent including Bengal (current Bangladesh) was a territory of South Asia (see Appendix

A). Buddhist and Hindu rulers governed the territory. In the 1200s, Muslim armies conquered

and ruled the regions, and the Mughals began to rule in 1576. In the 1600s, the British

government established the East India Company (a mercantile company of England) within the

Indian subcontinent. In the mid-1700s, the East India Company emerged as the strongest

20

economic entity in Bengal, and later it occupied the administration (Ali, 1999; Khan, 2011;

Schendel, 2009).

Finally, in 1757, the British administration defeated Muslim ruler Nawab Siraj-ud-daula

and the longest and influential colonial regime began on the Indian subcontinent. The British

East India Company arrived in the subcontinent to trade. Later, along with the British regime,

they got involved in politics and ruled the subcontinent from 1757 to 1947. During colonial rule,

Bangladesh was a territory of the Indian subcontinent (Khan, 2011; Rahman, Hamzah, Meerah,

& Rahman, 2010; Schendel, 2009).

Education on the India subcontinent passed through various systems, beginning with

indigenous education in ancient times, an Islamic style of education during the Muslim invasion,

and colonial education under the British regime. In the British era, the regime along with the

British East India Company managed the education system for the native people. They never

planned to improve the local peoples’ quality of education in the Indian sub-continent. Rather, in

1835, the regime began to promote the English language, English literature, and the Western

culture in the subcontinent and imposed them on the local people. For this reason, the number of

English medium schools (teach Cambridge English curriculum) increased and began to teach the

English language, English literature, and the Western culture. Liberal English-language schools

based on the British model, such as , Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary

Education(IGCSE) and the Edexcel curriculum continue to exist in present-day Bangladesh

(Khan, 2011; Rahman et al., 2010; Schendel, 2009).

Pakistan regime (1947–1971). The British colonial era ended in 1947, and the Indian

subcontinent got autonomy as two independent countries based on their religious ideologies—

India, where the Hindus are majority and Pakistan, where Muslims are the majority. As a Muslim

21

dominant territory, Bangladesh became a region of Pakistan and was named East Pakistan. The

Pakistani government began to reconstruct the education system of the country. As Pakistan

obtained autonomy based on Islamic ideology, Islamic values and culture had a strong influence

in the education system, and the government made Urdu its medium of instruction throughout

the nation. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, founder of Pakistan, tried to direct education in Pakistan

toward a specific goal, which was to develop the character of future generations based on Islamic

values and culture. During the Pakistan era, several education committees and commissions

formed to reform the education system. Eventually, the regime used the committees and

commissions for political purposes. The phenomenon showed that Pakistan carried on the legacy

of colonial education characteristics coupled with colonial legacy (Khan, 2011; Nath, 2009;

Rahman et al., 2010).

Bangladesh era. The people of Bengal experienced economic, cultural, and political

suppression and discrimination from 1538 to 1971 under different regimes and entities

(Schendel, 2009). Like the previous colonial regimes, West Pakistan ruled East Pakistan

(Bangladesh) from 1947 to 1971 and continued the discriminations in social, cultural, and

educational areas in the region. Consequently, economic, socio-political, and cultural

discriminations and hardship angered and disconnected the people of East Pakistan from West

Pakistan. Thus, discriminations led the people of East Pakistan toward an independent country.

Having suffered unfair treatments from 1947, Bangladesh achieved independence from West

Pakistan in 1971 after a war of liberation (Rahman et al., 2010).

Rahman et al., (2010) added that in independent Bangladesh, the literacy rate of newly

formed country was only 17.61%. Bangladesh continued to suffer through various crises and

political turmoil, under, two military governments – from 1975 to 1981 and from 1982 to 1990.

22

The secular and ethnic Bengali identity changed to a state-based and pseudo-Islamic Bangladeshi

identity. In amendments to Bangladesh's Constitution Islam was declared as the state religion

and "absolute trust and faith in Allah" took the place of secularism. Rahman et al. indicated that

the government used education to promote- 'Bangladeshi'- nationalism. In 1982, the government

began sponsoring religion-based Madrassa education and made religious education mandatory up

to secondary education level (classes 6 to 10).

Between 1972 and 2008, the governments formed nine education commissions and

committees, and those commissions and committees prepared nine education policy reports for

Bangladesh's education system. Unfortunately, none of the education policies could be

implemented fully due to political reasons and instability (Ali, 1999; Nath, 2009; Rahman et al.,

2010). The characteristics of colonial education and its impact carried on in Bangladesh's

education system, even after independence (Metcalf & Metcalf, 2006).

Geography. Bangladesh is a South Asian country, and it is situated approximately

between 20.30º and 26.45 º north latitudes, and 88.00º and 92.56º east longitudes. Bangladesh is

bordered by India on the west and north, by India and Myanmar on the east, and by the Bay of

Bengal on the south. Bangladesh comprises an area of 148,460 sq km of area (Central

Intelligence Agency [CIA], n.d.; Rodrigues, 2009).

Demographics. As of July 2016, the population of Bangladesh is approximately 156

million (CIA, n.d.), similarly, as of 2015, literacy rate of those above 15 years of age, who can

read and write is 61.5% (CIA, n.d.). Based on ethnicity, about 98% people are Bengali and 2%

fall under various ethnic groups (CIA, n. d.). In the same way, as of 2013, based on religions,

89.1% of the people are Muslims, 10.0% are Hindus, and 0.9% are Buddhists, Christians, and

believers in tribal faiths (CIA, n. d.).

23

Christianity in Bengal. In the 1500s, Portuguese and other European traders traveled to

India for business purposes through a sea-route and landed first in Cranganore, then Cochin and

Goa. Missionaries of Franciscan, Dominican, Augustinian, and Jesuit religious orders also came

to serve the needs of European traders as well as to evangelize the local people. In Bengal, the

Portuguese were the first Christians. After the intermarriage of the Portuguese with local women,

their children became the first native Christians (D’Costa, 1988).

Portuguese traders began trading in Bengal in the 16th century and brought Christianity

through the Chittagong port. They built their first church in 1599 in Chandecan (known as

Iswaripur or old Jessore) and in Diang (Dianga) in Chittagong in 1601 (D’Costa, 1988;

Rodrigues, 2009). Portuguese Augustinian missionaries brought Catholicism to Dhaka in 1612

and built the first church in Narinda in 1628. A second church was built at Tejgaon in 1677,

followed by a third at Nagori in 1695. In 1764, a fourth church was built in Padrishibpur and

another one at Hasnabad in 1677 (D'Costa, 1988; Rodrigues, 2009).

William Carey, an influential Protestant preacher, arrived in 1793 and began his work in

West Bengal. A large number of Baptist, Protestant, and Anglican missionaries came to Bengal

from Britain, America, Australia, and New Zealand. Missionaries contributed in various ways.

Besides evangelization, churches and missionaries established and managed various educational

institutions as well as healthcare and welfare organizations for poor, underprivileged, and less-

privileged people. Catholic and non-Catholic churches have continued the commitment and

service in education, health care, and other welfare sectors (D'Costa, 1988; Rodrigues, 2009).

Catholic Church sponsored educational institutions. In Bangladesh, the Catholic Church

continues serving the people in various sectors including education. According to J. F. Gomes

(personal communication, September, 27, 2011) the Catholic Church operates about 613

24

educational institutions, including one university, two colleges, four higher secondary schools,

47 high schools, 15 junior high schools, and 544 primary schools. These educational institutions

serve Muslims, Hindus, Christians, Buddhists, and the indigenous population (Costa, 2015).

Holy Cross in Bengal. In post-revolutionary France, a drought of education, especially

education in faith emerged as a crucial need. The Congregation of Holy Cross— comprising

brothers, priests, and sisters— began teaching the local youth to meet their educational needs.

Father Basile Anthony Moreau founded the Congregation of Holy Cross in 1835 in Le Mans, and

its charisma was its education mission. Father Moreau wanted to educate the minds and hearts of

the youths. Academic excellence, knowledge, values and morals were equally important.

Students needed to be taught all aspects of knowledge with equal significance. Eventually, the

congregation began to send missionaries to various parts of the world, including Eastern Bengal

to continue their missionary work including in education ("A brief history", 2012; Catta & Catta,

1955; Grove & Gawrych, 2014; Jenkins, 2011; Moreau, 1943).

Reaching Eastern Bengal in 1853 at the invitation of Bishop Oliffe, the Vicar Apostolic

of Eastern Bengal, Holy Cross started their missionary activities in Noakhali, Dhaka, and

Chittagong. Holy Cross missionaries in Bengal conducted pastoral care, health care and

educational activities for the local people. Bengal missions required incredible sacrifices, effort,

and zeal from Holy Cross missionaries, and this legacy has continued to the present day by the

local priests, brothers, and sisters (Catta & Catta, 1955; Rodrigues, 2009).

Holy Cross institutions. The Congregation of Holy Cross's major ministry has been an

educational mission. Currently, it operates one university, one teacher training college, two

colleges (Grades 11 and 12), three higher secondary schools, nine high schools, and three

schools for underprivileged children. (Rodrigues, 2012). All of these institutions are engaged in

25

educating the hearts and minds of students through classroom instruction and co-curricular and

extracurricular activities (Students’ Handbook, 2014).

Bangladesh's education system. Prior to the British regime, Nawabs and Zamindars

ruled the Bengal region and they seemed less careful about education and it’s improvement.

Therefor, local communities promoted education. The Hindus managed tols and pathshalas

(indigenous primary education) and Brahmin pandits (faith-based teachers) used to teach. The

Muslims managed madrassas and maktabs (Islamic faith-based educational institutions) and

maulavis (faith-based teachers) used to teach Islamic ideologies (Ahmed & Khan, 2004). Ahmed

and Khan (2004) stated that during the early period of the British regime, the government did not

have much interest in the education of the local people; rather, they were more interested in the

trading industry. Observing the government's apathy, missionaries, philanthropic officials, and

merchants, both in their individual ability and private societies, made efforts to improve

education for the local people and established several schools. In the long run, the British regime

formed the General Committee of Public Instruction for the Indian subcontinent and emphasized

the English language, English literature and Western education creating a local upper class rather

than improving a local education system for the majority of people. During the Pakistan regime,

education commissions recommended that primary education be made free and compulsory and

that few changes in the structure of education be made. However, the education system carried

on the colonial characteristics (Ahmed & Khan, 2004).

Current educational practices. Bangladesh inherited its education system from the

colonial regime, both mainstream and secular education along with religion-based education. In

Bangladesh's education system, some characteristics and impacts of colonial education still

exists today. The current education system has three major stages: primary, secondary, and

26

tertiary or higher education (UNESCO, 2011). A detailed structure and levels of education of

Bangladesh education system is shown in the appendix (appendix B).

Divisions in education. Considering the curriculum, Bangladesh's education system has

three main streams: (a) general education, which begins at secondary level and includes science,

arts, business studies, and social sciences; (b) madrassa education, which is an Islamic faith-

based education that begins at the primary level; and (c) technical and vocational education,

which is a skills-based education that begins at the secondary level. In addition, there are English

medium schools that follows the British English curriculum, such as the one followed by

Cambridge and Edexcel International; English version schools that follow the national

curriculum and whose medium of instruction is English; and Cadet schools that follow the

national curriculum and are conducted by military personnel. There is also professional

education—for example, medical, technological, and so forth— in higher education levels

(UNESCO, 2011; Rahman et al., 2010). In Bangladesh's education policy, school year comprises

January to December and college and university, July to June. In school calendar, longer

holidays comprise during Islamic religious festivals (Eid-Ul-Fitr and Eid-Ul-Adha) and a brief

break during summer and Hindu religious festivals (UNESCO, 2011; Rahman et al., 2010). As

stated by Bangladesh's education policy, a school year runs from January to December, and

colleges and universities run from July to June. In a school calendar, longer holidays take place

during Islamic festivals (Eid-Ul-Fitr and Eid-Ul-Adha) and a brief break occurs during the

summer and Hindu religious festivals (Rahman et al., 2010; UNESCO, 2011).

In Bangladesh, education is considered to be one of the fundamental rights of all people

irrespective of creed, culture, and gender. All people have the right to receive an education and

through education, acquire knowledge, skills, and values. A few of the goals of education are

27

developing universal, cultural, and moral values and imparting them. Cultural and moral values

make community members important and unique. Basic education is not a goal but a way to

transform citizens into lifelong learners (UNESCO, 1994).

Values, Education, and Values Education

Values. The word ‘value’ derives from the Latin word 'valere' which means to be worth

and strong. Values are also traits that make one relatively worth, important, excellent, and

principle or quality intrinsically valuable (Ignacimuthu, 2013). They are beliefs, attitudes, or

feelings that a person is proud of and openly affirms (Halstead, 1996), and they are ideals,

customs, and institutions that arouse an emotional response, for or against them, in a given

society or a person (Stein, 1988). The literal meaning of value is something that has a price,

something precious, dear, and worthwhile. Ignacimuthu (2013) defined values as the following:

Values are a set of principles or standards of behaviour; they are regarded as

desirable, important, and held in high esteem by a particular society in which a

person lives; and the failure to hold them will result in blame, criticism, or

condemnation (p.13).

Values can be defined as codes that guide manners that convince our actions, attitudes, and

become a framework for living (UNESCO, n. d.). According to Schwartz (2012), the main

features of all values are the following: (1) values are beliefs refer to desirable goals; (2) values

transcend specific situations and actions; (3) values serve as a standard or criteria; and (4) values

are ordered by importance, and the relative importance of multiple values guides the action.

Education. A dictionary-based meaning of education is an act and a process of

transmitting and attaining general knowledge and skills and developing the commands of logic

and judgment (Stein, 1988). Education as defined UNESCO (2011) defines education as

acquiring, innovating, acclimatizing, and transmitting information, knowledge, skills, and values

based on the needs of people in society in a formal or informal setting. Furthermore, the United

28

Nations (UN, 1949) stated that education is a right, and people must have an opportunity to get

an education. The UN's declaration on education integrates values -

Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and

to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It

shall promote understanding, tolerance, and friendship among all nations, racial or

religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the

maintenance of peace (p. 6).

According to Flannery (1975), true education is aimed at total the development of a

person for the good of society. Therefore, education is not only, academic information but also a

holistic and humanistic human development. Education integrates values, skills, innovations,

culture, continuing development, and societal concerns. Education is the key component to

achieving larger goals, such as building peace, wiping out poverty, and continuing development,

and interconnectedness (UNESCO, 1994, 2011). Therefore, values and education are integrated.

Values education is the heart of education (Chareonwongsak, 2006).

Values education. Correspondingly, values education means school-centered activities

that inspire students' perceptions and awareness about values. Values education cultivates