Before devoting herself fully to her art and poetry practice, Abigail

Reyes studied and worked as a secretary. This experience deeply

influenced her approach to artmaking and is particularly visible

in Plana. The piece is composed of sheets of paper with repeated

lines from a secretarial-training typing manual which are held

together by embroidery and suspended overhead. Objects and tools

associated with work viewed as women’s professions, seldom seen

in public, are thus transformed into a way of openly voicing the

inequities of that work.

Reyes’s practice draws on research including studies of soap

operas, significant in Latin American popular culture, oen featur-

ing a character of “the secretary,” as well as interviews with women

who worked in such positions. These accounts, combined with her

own, become testimonies to the struggles and abuse intrinsic

to power structures that require a submissive, depersonalized, and

disciplined feminized body to accomplish their aims. Reyes reclaims

the poetry at the heart of repetition, and finds through such systems

her own way out of abusive experiences. “My intention is to

reflect from all these places,” the artist has said, “on the inequalities

that continue to exist in the workplace, for secretaries, but also

for professions considered as women’s jobs, and their problems.”

Underscoring the mechanical repetition and almost military order

required in this profession, the artist shows how these skills can

also become tools for endurance.

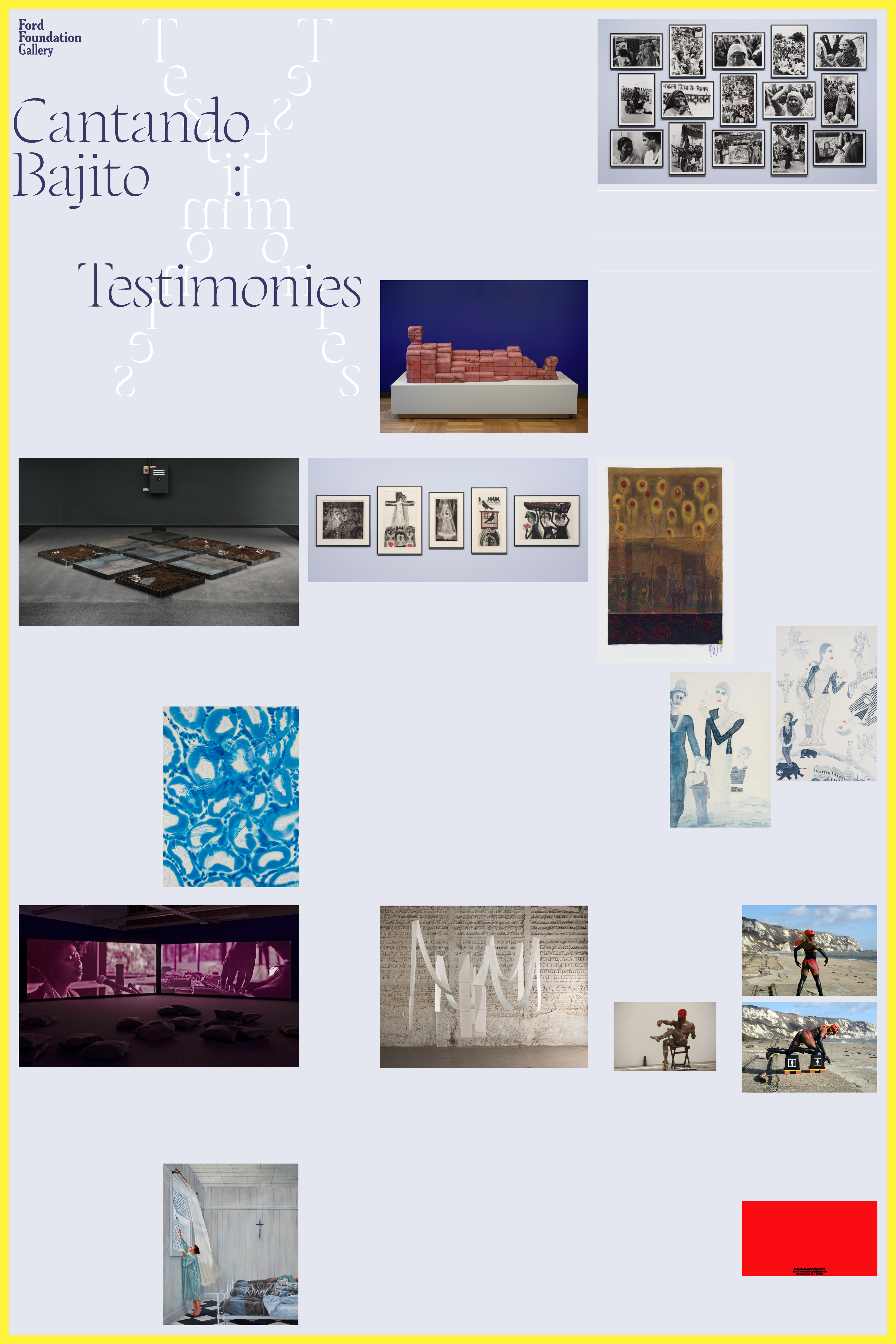

Sheba Chhachhi is a photographer and installation artist who inves-

tigates questions of gender, eco-philosophy, violence, and visual cul-

tures. An activist/photographer through the 1980s–90s, Chhachhi’s

works bring together her artistic vision, her feminism, and decades

of involvement in the women’s movement in India. In From the

Barricades, Chhachhi revisits her archive of documentary images made

between 1980 and the late 1990s to explore how both the self and the

collective are formed through protest and resistance.

The photographs begin with images from the anti-dowry

movement in New Delhi, which peaked in the early 1980s, gaining

momentum aer the dowry-related femicides of Shashi Bala and

Jaswanti. The anti-dowry campaign led to legislation, the establish-

ment of women’s cells in the city, as well as building social stigma

around the practice. Other images depict Indian women’s demon-

strations and awareness campaigns against other forms of oppres-

sion, such as rape, religious fundamentalism, domestic violence, and

state violence. Key figures of Indian women’s rights activism appear

in Chhachhi’s photographs, such as Shahjahan Apa (1936–2013),

the mother of a dowry victim who campaigned against dowry and

co-founded a shelter for survivors of gender violence; Shanti and

Devi, activists with Action India, a foundational organization of the

autonomous women’s movement; Moloyashree Hashmi, a performer

who co-founded the Jan Natya Manch New Delhi street theater

company; and Maya Krishna Rao, a theater and street performer,

educator, and activist.

Lalitha Lajmi was born into a family of artists in Kolkata, India,

in 1932. She studied the intricate art of intaglio and etching in

evening classes and set up a printing press in her kitchen in the early

1970s. Working late into the night by electrical light, she created sin-

gular prints that showcase her unique use of grisaille and sepia tones.

Lajmi’s creativity and talent were not limited to printing, as she went

on to produce oil paintings and watercolors. Her works narrate an

intimate and layered history of an Indian woman artist living and

working in the years following India’s independence.

Lajmi balanced her career with family responsibilities and

teaching art. Drawing inspiration from her own life, her largely

autobiographical artwork contemplates gender roles and patriarchy.

Metaphorical images of dream sequences, relationships, and

performances recur across her works. The performer figure in these

works, oen portrayed as a clown, represents gendered roles she per-

formed in her own domestic life. The motif of the mask signals the

concealment of one’s true identity, feelings, and aspirations

while performing.

TOP ROW LEFT TO RIGHT:

Exhibition on patriarchy,

community fair,

Landworkers’ Union,

Mehrauli, 1983

Sit-in at Nangloi police

station, Jaswanti’s dowry

death, New Delhi, 1981

Satinder of Trilokpuri,

widowed in anti-Sikh

violence, women’s

meeting resisting

communal violence, 1985

Anti-dowry

demonstration, India

Gate, New Delhi, 1982

Shahjahan Apa, mother

of dowry victim, public

testimony, Boat Club,

New Delhi, 1981

MIDDLE ROW LEFT TO RIGHT:

Maya Rao performing in

Om Swaha, anti-dowry

street play, Mehrauli,

1980

Dalit leader speaking

at Women’s Tribunal on

violence against women,

Lucknow, 1997

International Women’s

Day procession, Karol

Bagh, New Delhi, 1983

Anti-dowry

demonstration, New

Delhi, 1981

Jaswanti’s mother, public

testimony, Nangloi police

station sit-in, New Delhi,

1981

BOTTOM ROW LEFT TO RIGHT:

Shanti and Devi, feminist

health workers meeting,

Action India oce, New

Delhi, 1991

International Women’s

Day March protesting

violence against women,

New Delhi, 1987

In the community,

protesting sexual child

abuse in the home, New

Seemapuri, New Delhi,

1992

Moloyashree performing

in Aurat (Woman) street

play by Jan Natya Manch,

New Delhi, 1981

Shanti, Action India,

storytelling with painted

scroll, consciousness-

raising on patriarchy

in the community,

Dakshinpuri, New Delhi,

1990

SHEBA CHHACHHI

(Ethiopia, b. 1958, lives and

works in India)

From the Barricades, 198097

Archival pigment prints

SYLVIA NETZER

(United States, b. 1944)

Glen-Gery Olympia, 2004

Carved brick and encaustic

MARCH 5

MAY 4, 2024

SHEBA CHHACHHI

GABRIELLE GOLIATH

LEONILDA GONZÁLEZ

LALITHA LAJMI

KENT MONKMAN

TULI MEKONDJO

SYLVIA NETZER

ABIGAIL REYES

DIMA SROUJI

KEIOUI KEIJAUN THOMAS

CURATED BY:

ISIS AWAD, ROXANA FABIUS,

BEYA OTHMANI

WITH CURATORIAL

ADVISORY GROUP:

MARÍA CARRI, ZASHA

COLAH, MARIA CATARINA

DUNCAN, KOBE KO,

MARIE HÉLÈNE PEREIRA,

MINDY SEU, SUSANA

VARGAS CERVANTES

Maternal Exhumations II contemplates colonial violence towards

feminized bodies, looking specifically at archeological excavation

as a colonial practice in Palestine. The work stems from Srouji’s

research into archives of the first excavations led by American

and British archeologists around Sebastia, a small village in the

Palestinian West Bank. Srouji found that Palestinian women were

part of the workforce who excavated the land during these early-

20th-century missions. The artist took interest in how Palestinian

women were instrumentalized for political gain even as they

were being stripped of their land and subjected to colonial control.

Srouji’s installation aims to reinterpret and reclaim looted

Palestinian archeological artifacts, now housed in Western insti-

tutions, by creating forgeries of them in collaboration with profes-

sional forgers and glassblowers in Palestine. These artifacts are glass

vessels and toilet flasks, historically used by women in cleansing

and healing rituals. Placed in a grid of soil as though just excavated,

Srouji brings aention to the deep connection between Indigenous

Palestinian women and their land, emphasizing the rich evidence

of feminine life found within the earth. The installation offers

an homage to these women through imagining the vessels’ return

to the soil.

DIMA SROUJI

(Palestine, b. 1990, lives and

works in London)

Maternal Exhumations II, 2023

Steel trays, glass vessels, soil

The glass vessels were

produced by the Twam family

workshop in Jaba’, Palestine

Sylvia Netzer is a sculptor and professor whose career spans

more than fiy years and has transcended conventional media cate-

gories. Defining herself as a sculptor, she challenged established

notions in the field, working with clay and ceramics since the 1970s

when the material was seen as belonging to the world of cra.

Bringing ideas like modularity and repetition from the field of mini-

malist sculpture to her ceramics practice allowed Netzer to create

large-scale installations.

Though her artmaking is systematic and methodical in its

replication of molds and forms, it also focuses on the personal, on

her experience as a woman, and, in particular, as a large woman

who has been excluded and rejected from value systems. Her vision-

ary installations considered issues of body image and perception

when discussions of body positivity were not on the horizon of

the mainstream. Her striking blend of self-referential humor and

formal innovation gives her figures a uniquely engaging presence.

Glen-Gery Olympia, a monumental work in the form of a reclin-

ing woman composed of hand-carved terracoa bricks, is a clear

example of how Netzer combines both the personal and the sys-

tematic. Giving her personal experience space and size, grounded

in embodiment, Netzer’s work shows art’s unique power to share

understanding of others’ experiences of being.

KENT MONKMAN

(Canada, b. 1965)

I am nipiy, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

GABRIELLE GOLIATH

(South Africa, b. 1983)

This song is for . . ., 2019–

2-channel video installation

KENT MONKMAN

(Canada, b. 1965)

Compositional Study

for The Sparrow, 2023

Acrylic on canvas

ABIGAIL REYES

(El Salvador, b. 1984)

Plana, 2014

Rice paper, typed text

TULI MEKONDJO

(Angola, b. 1982, lives and

works in Namibia)

Omalutu etu, omeli medu eli/

Our bodies are within this soil,

2022

Image transfer, resin, acrylic

ink, cotton embroidery thread,

and rusted cotton fabric

on canvas

The Cree word “nipiy” means water in English. Floating blissfully

and eternally in water as if in space is Monkman’s gender-fluid alter

ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, a key figure in many of Monkman’s

tongue-in-cheek paintings.

Kent Monkman is an interdisciplinary Cree visual artist who

lives and works between New York City and Toronto. Monkman

is a member of Fisher River Cree Nation in Treaty 5 Territory

(Manitoba). Monkman reclaims the underrepresented historic and

contemporary experiences of Indigenous people by inserting and

intervening within canonical Western European and American art

history in shocking and oen cheeky ways. Across painting, film/

video, performance, and installation, Monkman’s work explores and

comments on themes of violence, colonization, joy, sexuality, and

resilience. A leading figure in many of Monkman’s interventions is

his gender-fluid alter ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, seen here, who

reverses the colonial gaze to challenge received notions of history

and Indigenous peoples.

Gabrielle Goliath generates in her practice spaces that sensitively

address gendered and sexualised violence. On entering the gallery

dedicated to This song is for . . . , audiences encounter a collection of

dedication songs, each chosen by a survivor of rape. These are songs

of personal significance to the survivors, evoking memories and

feelings. However, at particular moments in each song — and oen

comfortingly familiar ones — the notes are disrupted like a broken

record or a repeating scratch in memory.

As collaborators on the project, the survivors shared not only

their songs, but also a color of their choosing and a wrien reflec-

tion. The artist then worked closely with women- and gender-queer-

led musical ensembles to reinterpret and re-perform the songs.

Color and voice, both channels for visceral emotional meaning,

are entwined in Goliath’s platform for testimony that transcends

words, accessing deeper layers of understanding. In moments of

musical rupture, visitors witness a frozen present, sharing in testi-

monies of trauma entangled with personal and political claims to

life, dignity, hope, faith, and even joy.

Boarding or residential schools played a major role in the ethnic

cleansing or “civilizing” of Indigenous people. Almost one third of

these schools were administered by the Christian church. Monkman

paints a grim depiction of a child so close to freedom, represented

by a curious sparrow, yet just as far away from it.

Kent Monkman is an interdisciplinary Cree visual artist who

lives and works between New York City and Toronto. Monkman

is a member of Fisher River Cree Nation in Treaty 5 Territory

(Manitoba). Monkman reclaims the underrepresented historic and

contemporary experiences of Indigenous people by inserting and

intervening within canonical Western European and American art

history in shocking and oen cheeky ways. Across painting, film/

video, performance, and installation, Monkman’s work explores and

comments on themes of violence, colonization, joy, sexuality, and

resilience. A leading figure in many of Monkman’s interventions is

his gender-fluid alter ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, who reverses

the colonial gaze to challenge received notions of history and

Indigenous peoples.

LEONILDA GONZÁLEZ

(Uruguay, 19232017)

Novias revolucionarias

(Revolutionary brides), 196869

LEFT TO RIGHT: I, V, II, XI, IV

Woodcut

Leonilda González grew up in rural Uruguay during the first half of

the 20th century. There, she gathered most of her visual motifs and

connected with her drive to effect social change through art. She

chose printmaking as her main medium, and xylography in particu-

lar, because she believed its replicable and accessible qualities would

help her communicate with a larger audience.

To this end, she co-founded the “Club de Grabado de

Montevideo,” a graphic arts collective and school. This club would

go on to play an essential role in what would be called “el movi-

miento de la cultura independiente” (independent culture move-

ment), a group of member-funded arts institutions stepping in as

alternatives to governmental cultural organizations. At the height

of this movement, González made the series Novias revolucionar-

ias, which encapsulates both her signature tone—a combination

of irony, sarcasm, and anger—and her graphic mastery, using

contrast, Byzantine-inspired abstraction of bodies and faces, and

black-and-white.

The series presents multiple bride characters seen at the

moment of their wedding. When their presumed marital life of

love and happiness is supposed to begin, González represents them

as angry and performing acts of protest and rejection of a system

that will “imprison” them. Years later the works would be read

as images of opposition to the military dictatorship in Uruguay,

which González spent in exile.

Mekondjo is a Namibian artist whose practice addresses the search

for restitution and repair in the shadow of Namibia’s violent

colonial past. Drawing on colonial archives extracted from Namibia

during the German colonial period (1884–1920) and the illegal occu-

pation by South Africa (1965–1990), the artist conjures the presence

of Namibian women who labored as domestic workers during these

eras. Imagining a reversal of the colonial gaze, her canvas performs

a transformative healing and honoring of interrupted female

ancestral lineages. At the same time, the work also questions how

individuals and their lineages are recognized, or not, depending on

their gender. Through fiber-based burning, washing, embroidering,

and mending techniques, Omalutu etu, omeli medu eli / Our bodies are

within this soil draws connections between land, ancestry, and history

and channels their renewing life force.

LALITHA LAJMI

(India, 19322023)

LEFT TO RIGHT:

Performing . . . . , 2013

Performers . . . . , 2011

Watercolor

Keioui Keijaun Thomas is a New York-based artist. She creates live

performance and multimedia installations that address Blackness

outside of a codependent, binary structure of existence. Her

performances combine rhapsodic layers of live and recorded voice,

slipping between various modes of address to explore the pleasures

and pressures of dependency, care, and support.

The two images on view from 2019 were created while Thomas

was in residency in Folkestone, UK. The site where the artist is pic-

tured is adjacent to a slave port infamous for launching The African

Queen, a slave-trading ship, in 1792. The tracks beneath the artist’s

body are what remains of the road taken by the ruling class to reach

the coast, while avoiding the public in major cities. Thomas makes

a powerful juxtaposition between the past and present; the owned

body, and the free self, by posing defiantly atop two gendered blocks

referencing slave auction blocks.

Currently, Thomas is exploring the affective and material con-

ditions of Black and trans identity, expanding her ongoing practice

of world-building to create spaces of safety, joy, and healing through

her iterative multimedia project, Magma & Pearls, which spans over

four years of the artist’s career.

KEIOUI KEIJAUN

THOMAS

(United States, b. 1989)

Partitions of Separation

and Trespassing: Section

1. Selective Seeing, Part

2. Looking While Seeing

Through, Section 2.

Painted Images, Colored

Symbols, Part 3. Sweet

like Honey, Black like

Syrup, Human Resources

Los Angeles (HRLA),

Los Angeles, CA, 2015

C-print

Photo by Hector Martinez

Snatched n’ Tucked, Field

Day, Party Streamer,

Ocean Dancer aka Video

Vixen aka Hoe 4Life,

(Cheer, Leading), 2019

C-print

Photo by Andrea

Abbatangelo

Drop Me In The Sea,

Fishy (REALNESS),

Shopping Basket aka

Auction Block

aka Stripper Stage, Bricky

(Femme-hood), 2019

C-print

Photo by Andrea

Abbatangelo

BLACK BODIES,

20182021

Closed-captioned video,

hot-red, 1 loop with

voice/audio, 1 loop

without voice/audio

SYLVIA

NETZER

SHEBA

CHHACHHI

DIMA

SROUJI

GABRIELLE

GOLIATH

KEIOUI

KEIJAUN

THOMAS

KENT

MONKMAN

KENT

MONKMAN

LEONILDA

GONZÁLEZ

TULI

MEKONDJO

LALITHA

LAJMI

ABIGAIL

REYES

Cantando Bajito: Testimonies is the first movement

of a series of three exhibitions.

Translated into English as “singing softly,” the

exhibition series title is drawn from a phrase

used by Dora María Téllez Argüello, a now-liberated

Nicaraguan political prisoner, to describe the sing -

ing exercises she did while she was incarcerated

in isolation. Helping her to conserve her voice and

defeat the political terror she endured, Téllez’s

quiet singing became a powerful strategy for

survival and resistance. Conceived in three move-

ments, Cantando Bajito features artists who

explore similar forms of creative resistance in the

wake of widespread gender-based violence.

The exhibitions address rising threats against

bodily autonomy leveled toward feminized bodies,

from the overturning of Roe and attacks on

abortion rights, to violence against trans people

through bans of gender-arming therapy and

non-prosecution of homicides. Argentinian fem-

inist Verónica Gago has called these attacks on

the progress of feminist movements an aggressive

counteroensive—one that aims to break down

personal and collective freedoms. The exhibitions

attend to this violence from a place of resistance,

support, and joy rather than a place of victimhood.

Legal scholar Yanira Zúñiga Añazco uses

the term feminized bodies, in contrast to just the

female body, writing that: “The female body is con-

ceived as the opposite of the sovereign territory—

the male body—and, consequently, it is treated

as a territory to occupy. The same occurs, by exten-

sion, with other bodies, those that do not accom-

modate themselves to the ideal male body, which

is, therefore, feminized.”

1

Throughout this project,

we have chosen to use the term feminized body to

refer to a state of embodied vulnerability without

conforming to specific gender norms. Furthermore,

in using the term feminized body, we also reflect

on an understanding of vulnerability defined

not only by gender but also by social, material,

and geopolitical relations.

Cantando Bajito: Testimonies features a wide

range of artworks that foreground and build on

strategies used to confront this violence, to imag-

ine new forms of existing and thriving through

and beyond it. The artworks reveal the methods

individuals use to navigate violence, including

the value of the testimonial, community-building,

moving together in space, and subversive, even

humorous, gestures that provide sustenance and

pleasure. Grounded in a concept of testimony as an

act that bears witness publicly, not limited to the

spoken or written statement, Testimonies consid-

ers artworks as testimonial objects that carry

a political memory of feminized bodies. Our under-

standing of these objects reflects that of scholar

Marianne Hirsch, who defines them as carrying

memories while also creating a form of embod-

ied transmission within them.

2

They testify to the

historical context and the material quality of the

moments in which they were produced.

The vocal aspect of testimony is a central thread

running among the featured artworks, encom-

passing many bodily forms of expression such as

speaking, singing, protesting, taking of space in

silence, and other voiced acts, all used to seek

individual and collective survival, mobilization, and

resistance in the face of oppression and violence.

In Testimonies, we foreground the performance of

voice as a metaphor to celebrate its power as “an

expression of embodied uniqueness,”

3

a rehearsal

of language outside of patriarchal norms, and an

armation of agency.

Feminist postcolonial author and filmmaker

Assia Djebar has explored the theme of the voice

as being in a kind of entrapment, under the

silencing eect of forces such as patriarchal lan-

guage and oppressive societal structures. In her

writing and films, Djebar consistently experi-

mented with forms of language that allow the voice

to find its fullest reach and expression. In a text

she wrote about women filmmakers, for example,

Djebar describes filmmaking as an expression of

a desire to speak: “It is as though ‘shooting’ means

for women a new mobility of voice and body,”

she writes. “As a result, the voice takes wings and

dances. Only then, eyes open.”

4

As such, Testimonies brings together artworks

that seek ways of allowing the voice to find

its full mobility, to shed light, and to act against

multiple silencing forces. In Testimonies, artists

contemplate various sources and manifestations

of violence towards feminized bodies, whether

in the form of direct physical or psychological

violations, political oppression, exploitative labor,

land confiscation, or exclusionary representations

and language, to name just a few. They find ways

of resisting these violences in the poetic. All art-

works in the exhibition testify to the value of the

poetic as a means of sustenance, echoing the

words of American feminist writer Audre Lorde in

her influential essay Poetry is Not a Luxury: “For

women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital

necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of

the light within which we predicate our hopes

and dreams toward survival and change, first made

into language, then into idea, then into more

tangible action.”

5

In approaching artworks as testimonies and

poetic rehearsals of non-patriarchal forms of

expression, we also found the concept of speak-

ing nearby as conceived by filmmaker and author

Trinh T. Minh-ha, to be very close to the central

ideas explored by the artworks. Speaking nearby,

as Minh-ha explains, is “a speaking that does not

objectify, does not point to an object as if it is

distant from the speaking subject or absent from

the speaking place. A speaking that reflects on

itself and can come very close to a subject without,

however, seizing or claiming it.”

6

This is particu-

larly reflected by the strategies devised by artists

such as Dima Srouji, Tuli Mekondjo and Gabrielle

Goliath. Their work questions systems that render

feminized bodies invisible, and seeks to channel

destinies that have been violently suppressed and

marginalized. Similarly, Lalitha Lajmi’s autobi-

ographical watercolors and Leonilda González’s

prints address gender roles by opening up spaces

of imaginative subversion, while Sheba Chhachhi’s

intimate photographic archive of the Indian fem-

inist movement testifies to moments of women’s

protest, and creates a visual memory of bodies

in movement and solidarity. Abigail Reyes and

Sylvia Netzer perform personal acts of resistance

towards systemic oppression on the individual

level by engaging in repetitive processes that give

new meanings and space to bodily experience.

This is again evident in Keioui Keijaun Thomas’s

video that performs the ongoing violence endured

by Black bodies, and specifically feminized Black

bodies, through simple yet powerful solid color,

text, and sound. Kent Monkman’s approach of

re-painting canonical artworks of colonial violence

on Indigenous communities to insert glimmers of

hope, joy, and resilience within an otherwise bleak

and one-sided history, also embodies that strategy.

When putting together the collection of works

in the exhibition, we were guided by the concept of

aesthetic vulnerability coined by sociologist Leticia

Sabsay based on recent performative actions by

feminist movements in Argentina that show the

political potential of bodies facing precarity and

insecurity together en masse.

7

Rallying against the

aesthetics of cruelty so apparent in the violence of

our everyday, these bodies are “moved by desire,”

rather than fear.

In a similar way, a recent song titled “Algo

Bonito” released by Puerto Rican artists iLe and Ivy

Queen, who is known as the Queen of Reggaeton,

not only attests to the violence experienced by

feminized bodies but reacts to it from a place of

forceful defense, of warmth and community.

Ivy Queen exclaims: Nunca he creído que callaíta

me veo mas linda, which can be translated as

“I never believed that keeping quiet makes me

look prettier.” This is followed by the line: Cuando

escupo es como fuego y ácido, meaning “when

I spit it’s like fire and acid.” Spitting here serves in

place of speaking, causing a voice to be heard,

and as such it carries the power of a testimony of

burning, of acknowledging, of transmitting,

of preventing, of honoring, of being the trigger of

transformation. The fierce and warm protection

reflected by the song is akin to the spirit of

this exhibition, which creates a space for joining

together, a celebration of the power, hope, and

joy of collective resistance.

ABOUT THE CURATORS

ISIS AWAD

is a curator, writer, and poet from Cairo, Egypt. She

is the Founding Director of Executive Care*, a self-as-organization

curatorial practice at the service of trans and queer artists

of color from performance and nightlife. She also helps organize

national conferences aiming to find solutions for youth homeless-

ness as Events Manager with the nonprofit organization, Point

Source Youth. She was Exhibitions and Development Manager at

Participant Inc in New York from 2018–19, and MFA Exhibition

Coordinator at The Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at

Bard College from 2021–2022. Her writing has been published by

The Brooklyn Rail, ArtAsiaPacific Magazine, Art Papers, BOMB Magazine,

Topical Cream, and Movement Research Journal.

ROXANA FABIUS is a Uruguayan curator and art administrator

based in New York City. Between 2016 and 2022 she was Executive

Director at A.I.R. Gallery, the first artist-run feminist cooperative

space in the U.S. During her tenure at A.I.R. she organized pro-

grams and exhibitions with artists and thinkers such as Gordon

Hall, Elizabeth Povinelli, Jack Halberstam, Che Gosset, Regina José

Galindo, Lex Brown, Kazuko, Zarina, Mindy Seu, Naama Tzabar

and Howardena Pindell among many others. These exhibitions,

programs and special commissions were made in collaboration with

international institutions such as the Whitney Museum, Google

Arts and Culture, The Feminist Institute, and Frieze Art Fair in

New York and London. Fabius has served as an adjunct professor

for the Curatorial Practices seminar at the Center for Curatorial

Studies, Bard College, and Tel Aviv University. She has also taught

at Parsons at The New School, City University of New York,

Syracuse University, and Rutgers University.

BEYA OTHMANI is an art curator and researcher from Algeria

and Tunisia, dividing her time between Tunis and New York.

Currently, she is the C-MAP Africa Fellow at the Museum of Modern

Art (MoMA), New York. Her recent curatorial projects include

the Ljubljana 35th Graphic Arts Biennial and Publishing Practices

#2 at Archive Berlin. Previously, she took part in the curatorial

teams of various projects with sonsbeek20→24 (2020), the Forum

Expanded of the Berlinale (2019), and the Dak’Art 13 Biennial (2018),

among others, and was a curatorial assistant at the Berlin-based

art space, SAVVY Contemporary. Some of her latest curatorial

projects explored radical feminist publishing practices, post-colonial

histories of print-making, and the construction of racial identities

in art in colonial and post-colonial Africa.

ABOUT THE FORD FOUNDATION GALLERY

Opened in March 2019 at the Ford Foundation Center for Social

Justice in New York City, the Ford Foundation Gallery spotlights

artwork that wrestles with difficult questions, calls out injustice,

and points the way toward a fair and just future. The gallery func-

tions as a responsive and adaptive space and one that serves the

public in its openness to experimentation, contemplation, and

conversation. Located near the United Nations, it draws visitors

from around the world, addresses questions that cross borders, and

speaks to the universal struggle for human dignity.

The gallery is free and open to the public Monday through

Saturday, 11 a.m.–6 p.m. It is accessible to the public through the

Ford Foundation building entrance on 43rd Street, east of

Second Avenue. www.fordfoundation.org/gallery

ABOUT THE FORD FOUNDATION

The Ford Foundation is an independent organization working to

address inequality and build a future grounded in justice. For more

than 85 years, it has supported visionaries on the frontlines of social

change worldwide, guided by its mission to strengthen democratic

values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international coopera-

tion, and advance human achievement. Today, with an endowment

of $16 billion, the foundation has headquarters in New York and 10

regional offices across Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle

East. Learn more at www.fordfoundation.org.

FORD FOUNDATION GALLERY

320 East 43rd Street

New York, NY 10017

www.fordfoundation.org/gallery

1 Yanira Zúñiga Añazco, “Body, Gender and Law. Notes for a

Critical Theory of the Relationships Between Body, Power and

Subjectivity,” Ius et Praxis 24, no. 3 (2018): 209-254. hps://dx.doi.

org/10.4067/S0718-00122018000300209.

2 Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory. (New York,

New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

3 Adriana Cavarero, For More Than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy

of Vocal Expression. (Stanford, California: Stanford University

Press, 2005).

4 ‘A Woman’s Gaze, Assia Djebar, 1989’, SABZIAN.BE, accessed

16 January 2024, hps://www.sabzian.be/text/a-woman%

E2%80%99s-gaze.

5 Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider : Essays and Speeches, Crossing Press

Feminist Series. (Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press, 1984), 37.

6 Nancy N. Chen, “‘Speaking Nearby:’ A Conversation with Trinh

T. Minh–ha,” Visual Anthropology Review 8, no. 1 (March 1992):

82-91, hps://doi.org/10.1525/var.1992.8.1.82.

7 Leticia Sabsay, “The Political Aesthetics of Vulnerability and

the Feminist Revolt,” Critical Times 3, no. 2 (2020): 179–199,

hps://doi.org/10.1215/26410478-8517711.

Printed on the occasion of the exhibition Cantando Bajito:

Testimonies (March 5May 4, 2024). Ford Foundation Gallery would

like to extend a very special thanks to our many partners

and collaborators.

EXHIBITION LENDERS: Dev Lajmi, Sumesh Sharma, Gallery Art & Soul

(Mumbai), Hales Gallery (New York), Museo Nacional de Artes

Visuales (MNAV) Uruguay, and all artworks courtesy of the artists

INSTALLATION AND PRODUCTION: Karl Tremmel, Brian McLaughlin,

Kris Nuzzi, Zee Toic, David Jacaruso & Kevin Siplin—

Art Crating Inc., Jeremy Kotin, Kris Rumman

EQUIPMENT AND FABRICATION: Laumont Photographics, Muscato Frames,

Pochron Studios, PRG Gear, Serett Metalworks, Stretch Shapes

INTERNATIONAL SHIPPING: Lucie Poisson, Meg Worman—ESI Fine Art

GRAPHIC DESIGN: Julie Cho, Alice Chung, Karen Hsu—Omnivore, Inc.

WRITER AND COPYEDITOR: Emily Anglin

PHOTOGRAPHY: Sebastian Bach, Jane Kratochvil

VINYL PRODUCTION AND INSTALLATION: Full Point Graphics

SPECIAL PROJECT COORDINATORS: Margrit Olsen, Kim Sandara,

Elizabeth Skalka

PRINTER: Masterpiece Printers

PHOTO CREDITS: Installation photos of works by Sylvia Netzer,

Sheba Chhachhi, Leonilda González, Lalitha Lajmi by Sebastian Bach

All works by Sheba Chhachhi © Sheba Chhacchi

Tuli Mekondjo—Courtesy of the artist and Hales Gallery, London

and New York. Photo by JSP Art

Abigail Reyes—Courtesy of the artist and La ERRE, Guatemala City

Gabrielle Goliath—Gina Folly

Dima Srouji—George Baggaley

Keioui Keijaun Thomas—Hector Martinez, Andrea Abbatangelo

Leonilda González works are courtesy of: