Waivered recruits: An evaluation of

their performance and attrition risk

Lauren Malone • Neil Carey

with contributions by

Yevgeniya Pinelis • Dave Gregory

CRM D0023955.A4/Final

March 2011

Public release version

This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue.

It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy.

Approved for public release. Specific authority: N00014-05-D-0500.

Copies of this document can be obtained through the Defense Technical Information Center at www.dtic.mil

or contact CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123.

Copyright 2011 CNA. All Rights Reserved

This work was created in the performance of Federal Government Contract Number N00014-05-D-0500. Any copyright

in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in DFARS 252.227-7013 and/or DFARS

252.227-7014.

Approved for distribution: January 2011

Anita Hattiangadi

Marine Corps Manpower Team

Resource Analysis Division

Photo credit line: Company C recruits conquer Basilone's Challenge, one of the last obstacles they must

overcome before calling themselves U.S. Marines. Photographer’s Name: Pfc. Michael Ito

Date Shot: 8/25/2010

i

Contents

Executive summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Background. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

This study . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Existing literature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Differences in Services’ waiver regulations . . . . . . . . . 9

Historical trends in the number of waivers . . . . . . . . . 10

Performance of waivered recruits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Army . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Navy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Marine Corps . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

A DoD-wide study . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Implications of previous research for this study. . . . 17

Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Characterizing waivered and nonwaivered recruits . . . . . . . 23

Determinants of attrition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Average attrition rates: how do waivered groups

compare? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Are recruits with multiple waivers riskier accessions? . . . 34

Does attrition vary by waiver type?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Army . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Navy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Marine Corps . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Air Force. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

How might the Services reduce attrition probabilities

for waivered recruits? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Army . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Navy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Marine Corps . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

ii

Air Force. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

Time to E5 promotion: waivered recruits vs. their

nonwaivered counterparts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Policy recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

Identify objectives and determine the most

relevant risks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

Minimize risks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

Eliminate the use of DAT waivers . . . . . . . . . . . 70

Consider providing commanders of recently

accessed Servicemembers with waiver

information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

More carefully screen those with “risky”

waiver combinations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

Regularly identify those waiver populations

with additional screening potential. . . . . . . . . . 72

A way to reduce the size of the waivered population . . . . 74

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

Appendix A: Demographic characteristics of

waivered and nonwaivered populations, by Service . . . . . 81

Appendix B: Geographic distributions of waivered and

nonwaivered recruits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

Appendix C: Analysis of those with multiple waivers . . . . . . 89

Comparing populations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

Do particular waiver combinations result in

higher risk? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

Appendix D: “Fast to E5” occupations and results . . . . . . . 97

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

List of figures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

List of tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

1

Executive summary

In this report, we examine the characteristics, performance, and attri-

tion risk of waivered recruits in each of the Services and compare

them with their nonwaivered counterparts. Our goal is to first identify

what, if any, risks the accession of waivered recruits creates for the Ser-

vices and then identify ways to mitigate these risks. The Services have

historically relied on enlistment waivers to increase the size of their

potential applicant pool because there are deserving people with a

desire to serve who have made mistakes or do not meet all of the stan-

dard qualifications.

The current recruiting climate is good—unemployment rates are

high and overall propensity to serve appears to be rising—causing

some to question the need and rationale for waivers. The Department

of Defense (DoD), however, believes that waivers should continue to

be a part of the recruiting and accession processes; DoD’s concern is

to minimize the risks taken by the Services in doing so. In this light,

OSD-Accession Policy asked CNA to evaluate whether the Services’

current use of enlistment waivers leads to recruitment of quality per-

sonnel and whether, once accessed, waivered recruits impose any

additional risks to the Services.

Our comparison of the demographic characteristics of recruits

reveals that waivered recruits, in all Services, are more likely than

their nonwaivered counterparts to be male, older, and Tier II (i.e.,

holders of nontraditional high school degrees). The waivered popu-

lation also has a greater proportion of whites (thus, a smaller propor-

tion of minorities) and is more likely to be married. When comparing

the military characteristics at accession of these two populations, we

find that waivered recruits, on average, spend less time in the delayed

entry program than their nonwaivered counterparts (highly corre-

lated with the fact that waivered recruits tend to be direct ships) and,

with the exception of the U.S. Air Force (USAF), tend to access at

lower paygrades. Finally, we find that waivered recruits are more likely

2

to come from the East North Central region and less likely to come

from the Pacific and Mid-Atlantic regions than their nonwaivered

counterparts. These geographic differences likely highlight the varia-

tion in recruiting difficulties that exist in different areas of the United

States. We use these demographic and geographic differences

between waivered and nonwaivered recruits in each of the Services to

inform our analysis of attrition and military performance.

Our comprehensive analysis of the attrition risk of waivered recruits

reveals that, in most cases, waivered recruits attrite at lower rates than

Tier II/III recruits, suggesting that they are, in fact, not the riskiest

accessions. We identify which waivered groups have the highest inher-

ent attrition risk, after controlling for a variety of demographic and

military characteristics. These findings tell us which waivered groups,

in each Service, have higher risk based on behavioral and unobserv-

able characteristics—characteristics that the Services have little

power to influence. For each Service, we choose a few waivered

groups in which there is potential to screen on observable character-

istics, and we identify ways in which the Services could reduce attri-

tion within these populations. All of these findings are highly Service-

specific and vary depending on whether the aim is to reduce 6-, 24-,

or 48-month attrition.

Finally, we evaluate the performance of waivered recruits relative to

nonwaivered recruits. Using time to E5 promotion as our principal

metric, we compare the prevalence of “fast” promoters in a select

number of occupational specialties for each of the Services, and then

compare this with the nonwaivered population. When separating the

populations by waiver type, those without waivers are in no cases

among the Services’ top performers, as measured by time to E5 pro-

motion. This reveals that many waivered recruits become high-quality

Servicemembers and, therefore, may not be the Services’ greatest

accession “risks.”

Overall, we find that waivered recruits are not inherently risky and are

often better performers, with lower attrition risk, than Tier II/III

recruits. There are, however, still ways in which the Services could

minimize the “riskiness” of the waivered population. For example,

each Service has a number of waiver combinations that are most likely

3

to lead to early attrition; additional screening or mentoring of these

recruits could potentially decrease their attrition risk.

Our analyses have allowed us to identify, within each Service, the

types of waivered recruits that impose the greatest risk, although these

findings depend on how the Services choose to define such risk.

Thus, moving forward, each Service must identify its objectives,

expectations, and most appropriate risk measures before determin-

ing how best to manage its waivered recruits.

4

This page intentionally left blank.

5

Introduction

Background

Each year, the Services require thousands of new recruits to support

the military's capabilities and long-term force health. The Services’

primary recruiting pool consists of 17- to 24-year-olds from a cross sec-

tion of society. The ideal recruit would be physically and mentally fit,

would meet height and weight standards, and would have no history

of serious legal problems or family issues. But the Services waive some

of these criteria because, among these youth, there are some who war-

rant the opportunity to serve. Roughly one in four young Americans

is too overweight to serve, and another third have other health prob-

lems that keep them from qualifying for service, such as diabetes,

asthma, or hearing impairments [1]. About 25 percent of young

adults lack a high school diploma or do not score high enough on the

Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) to qualify for

enlistment. Roughly 10 percent of young Americans have had legal

problems, such as a felony or serious misdemeanor offenses. Others

are ineligible for medical reasons or because they are single custodial

parents.

All told, it is estimated that only a quarter of American 17- to 24-year-

olds meet military qualification standards [1]. This figure, however,

masks considerable variation by Service, gender, and ethnicity. Taking

into consideration education, test score, weight, dependents, drug,

and legal qualification standards, one study estimates that less than 15

percent of black men could meet USAF standards, but 32 percent

could meet USMC standards; the corresponding numbers for white

men would be 31 percent for the Air Force and 46 percent for the

Marine Corps, respectively [2].

To compensate for the small percentage of recruits who meet all

entry criteria, the Services allow some portion to enter with marks on

their record that would otherwise disqualify them for service. Making

6

these exceptions requires an enlistment waiver.

1

For example, Ser-

vices can waive their usual requirements in such areas as physical fit-

ness (e.g., weight waiver), family status (e.g., a dependent waiver), or

legal matters (e.g., having a misdemeanor or felony waiver). Over the

years, each Service has developed and maintained its own waiver cat-

egories and standards. The Services have adjusted the categories and

their definitions over time in response to recruiting conditions and

policy decisions.

The selective use of waivers helps the Services to meet their recruiting

missions and, it is hoped, allows them to recruit deserving young

Americans who will make good military personnel. Past research has

shown that in some cases waivered recruits do as well as, or better

than, those who enter without waivers [3, 4]. Using waivers saves the

Services money by enlarging the supply of those potentially eligible

for service, but it costs the Services when waivered recruits attrite and

don't fulfill their service obligations. Reference [5], for example, esti-

mated that the annual cost of first-term non-end-of-active-service

(non-EAS) attrition in the Marine Corps exceeded $100 million in

1993.

This study

OSD-Accession Policy asked CNA to investigate whether there are

ways that the Services can minimize the risk of early attrition associ-

ated with waivered recruits. This study comes at a time of high unem-

ployment and a rising propensity to serve in the military, making it

the first time in 35 years when all the Services have been able to meet

their recruiting missions [6]. During this good recruiting climate,

policy-makers are asking whether the considerable resources that

DoD allocates to recruiting and retention programs are really neces-

sary. Annual funding for these programs more than doubled from

2004 to 2008, increasing from $3.4 billion to $7.7 billion [7].

1. Others refer to these as moral or moral conduct waivers. We use the

terms waivers or enlistment waivers throughout this document.

7

If there are categories of waivered recruits that perform as well as

nonwaivered recruits, selective waiver use could compensate for

potential budget cuts in recruiting and retention programs. Further-

more, even in today’s environment, there are a few specialties that

still face shortages of available, qualified Servicemembers to fill them

(e.g., ones that require high technical aptitude or specialized lan-

guage skills). In addition, the Services cannot expect current recruit-

ing success to continue when the economic situation improves. As a

result, OSD would like answers to such long-term questions as the fol-

lowing:

• In each Service, are there accession-related characteristics asso-

ciated with lower risk of early attrition for those accessed with

enlistment waivers?

• Could changes in the way that recruits with waivers are accessed

in each Service reduce the risk of early attrition?

• Are there other personal characteristics, such as high Armed

Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) scores or Tier I status, that

are associated with lower risk of early attrition for recruits

accessed with enlistment waivers?

• Could changes in accession policies reduce the risk of early

attrition?

In the past, the Services have had fairly heterogeneous waiver criteria.

These differences have historically made it difficult to make cross-

Service comparisons of the behavior of those accessed with any par-

ticular type of enlistment waiver. DoD, however, has required that the

Services standardize the reporting of enlistment waivers to OSD.

Under the Directive Type Memorandum (DTM), which took effect in

2008, the four major categories of waivers are conduct, dependent,

drug, and medical waivers [8].

This study involves two major tasks, each of which we address in this

research memorandum (inclusive of both waiver and no-waiver data

before the 2008 DTM). Within each Service:

1. We compare the performance of recruits accessed with and

without waivers.

8

2. We examine whether the presence of certain accession/per-

sonal characteristics can predict success for those with enlist-

ment waivers (e.g., does being a Tier I recruit compensate for

having a misdemeanor conviction?).

Throughout this report, we compare our findings relevant to the

waivered population with those relevant to Tier II/III recruits. We

make these comparisons in an effort to illustrate that, although

public perception is often that waivered recruits are among the poor-

est performers and are the most likely to attrite, Tier II/III recruits

are in fact a “riskier” population.

In this study, we conduct only intra-Service analysis. That is, we evalu-

ate the attrition risk and performance of waivered recruits as com-

pared with their nonwaivered counterparts within each Service, but

we do not make cross-Service comparisons. This is because, before

FY09, each Service had its own criteria regarding the behaviors and

characteristics that would necessitate a waiver. In the Marine Corps,

for example, any recruit who admits to one-time marijuana use

requires a drug waiver. This is not true in any of the other Services. As

a result, the percentage of USMC accessions with drug waivers is

much higher than in the other Services. Simply comparing the popu-

lations with drug waivers in the Marine Corps and the Navy, for exam-

ple, would lead to inaccurate conclusions. In other cases, the Services

were using different waiver codes to represent the same waiver type,

increasing the possibility for data misinterpretation.

In the next section, we review the existing literature in this area and

highlight our contributions. Then, we discuss the data sources used

in our analysis. The remaining sections focus on characterizing

waivered recruits (and how they differ from their nonwaivered coun-

terparts), analyzing their attrition behavior (and how this differs by

waiver type), and comparing their likelihood to be fast promoters to

the rank of E5 with that of nonwaivered recruits. Finally, we provide

policy recommendations and conclusions.

9

Existing literature

Over the last 20 years, enlistment waivers have been the subject of

many studies, newspaper pieces, and journal articles. This section

provides a high-level overview of these works as they relate to three

issues: (1) differences in the Services’ waiver regulations, (2) number

of waivers granted by Service, and (3) performance of waivered

recruits. The purpose of this overview is to help inform our analyses

of data on the performance of waivered and nonwaivered recruits for

FY99 to FY08.

Differences in Services’ waiver regulations

As mentioned earlier, each Service historically had its own enlistment

waiver standards, which made it difficult to compare the waivered

populations across Services and time. A 1999 Government Account-

ability Office (GAO) study summarizes some of the explicit differ-

ences across the Services’ waiver policies (see table 1) [9].

According to the GAO, as table 1 shows, for each offense, there was

at least one Service that used criteria different from the others. The

Navy (USN) and Air Force (USAF) allowed felony waivers for recruits

having more than one felony, whereas the Army (USA) and Marine

Corps (USMC) did not. But the Army and Marine Corps were differ-

ent from each other, too. The Army, for example, required a waiver

for two or more serious (not minor) offenses, whereas the Marine

Corps required a waiver for even one such offense. In short, no two

Services had exactly the same regulations regarding enlistment

waivers. This suggests that our initial analyses, which include data

only from those years before the implementation of the DTM, must

focus on comparing waiver types within each Service, rather than

across Services.

10

Historical trends in the number of waivers

The percentage of waivered accessions has varied considerably from

year to year and across the Services. As reviewed in [9], in FY90, across

the four Services, the percentage of recruits issued waivers was high-

est in the Marine Corps, at 60 percent, and lowest in the Air Force, at

2 percent. By 1994, however, the Services began to converge: waivered

recruits made up 29 percent of USMC accessions, 16 percent of USN

accessions, 6 percent of USAF accessions, and 5 percent of USA acces-

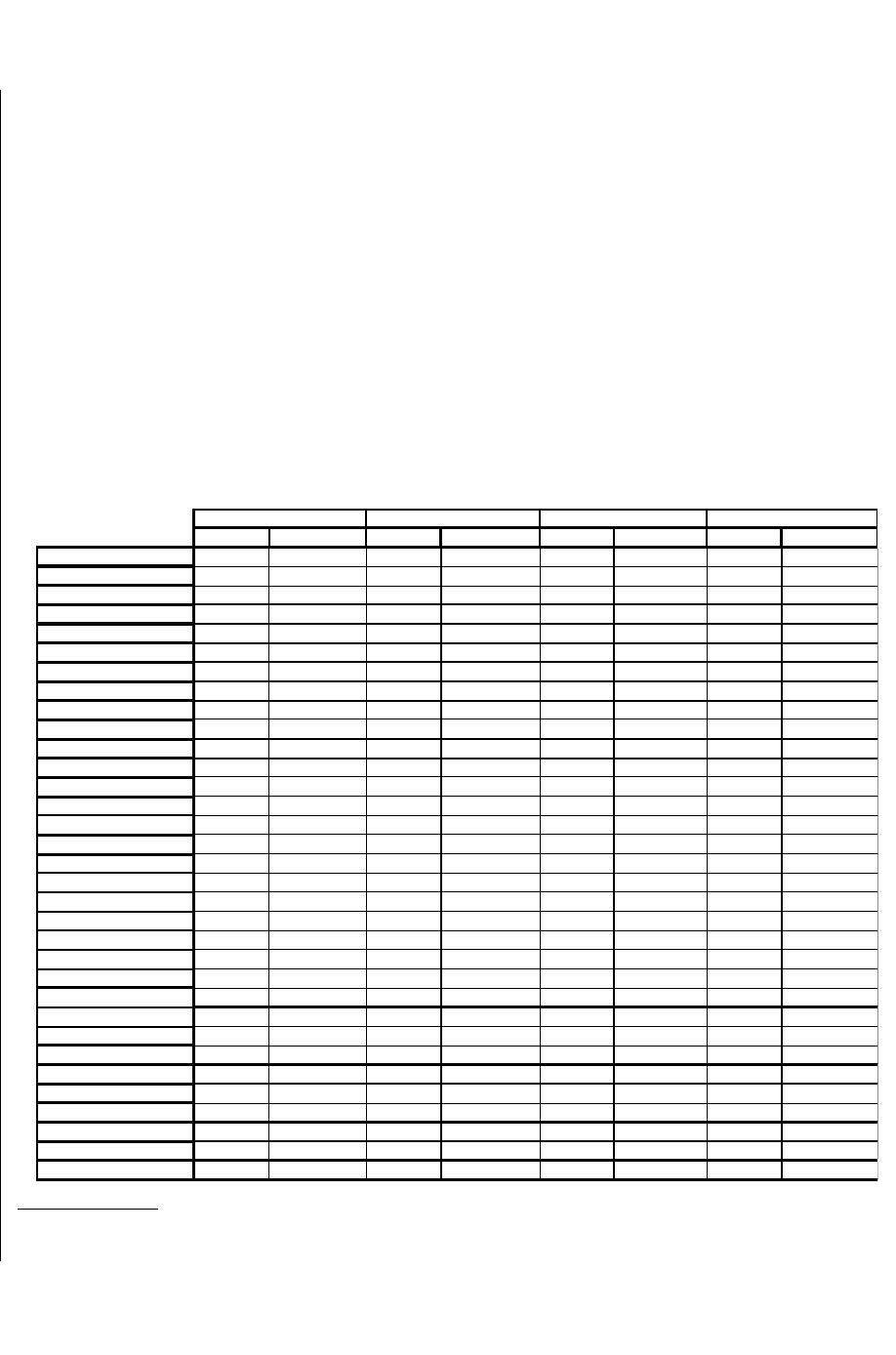

Table 1. Number of offenses requiring an enlistment waiver, by Service

a

Offense USA USN USMC USAF

Felony 1; no waiver allowed for

more than 1.

1 or more. 1; no waiver

allowed for

more than 1.

1 or more.

Serious

mis-

demeanor

2; no waiver allowed for 5

or more.

1 or 2; no waiver

allowed for 3 or

more.

1 to 5; no

waiver allowed

for 6 or more.

1 or more.

Minor

mis-

demeanor

Category not used. 3 to 5; no waiver

allowed for 6 or

more.

Category not

used.

1 or more.

Minor

non-

traffic

3 or more; 3 convictions

for a combination of mis-

demeanors and minor

non-traffic offenses.

3 to 5; no waiver

allowed for 6 or

more.

2 to 9; no

waiver allowed

for 10 or more.

Depending on seriousness

of offense: 1 or more; 2 in

the last 3 years; or 3 or

more in a lifetime.

Serious

traffic

Category not used. Category not used. 2 or more; no

waiver for 6 or

more.

Category not used.

Minor

traffic

6 or more where fine

exceeded $100 per

offense.

Within 3 years

before enlistment,

6 or more in any

12-month period or

10 or more in total.

5 or more. Depending on seriousness

of offense: 2 in last 3

years or 3 or more in life-

time; 6 or more or 5

minor traffic and 1 minor

non-traffic-related offense

in any 1-year period in

past 3 years.

Drug 1 arrest for drug posses-

sion or use, no waivers for

sale of drugs, those with

history of drug use coded

as medical waivers.

11 or more inci-

dents of marijuana

use, prior depen-

dence on any drug,

2 or more drug-

related offenses.

1 or more uses

of marijuana or

other drugs, to

include experi-

mentation.

15 or more incidents of

marijuana use, any illegal

use of amphetamines,

other stimulants, barbitu-

rates, or steroids.

a. Sources: [9] and additional input from the Services’ recruiting commands.

11

sions. We might guess that the Marine Corps issued more waivers than

the other Services in the early 1990s (because of the first Gulf War)

and fewer during the military drawdown of the mid-1990s. The main

reason for these sizable differences, however, is likely that the Marine

Corps is the only Service to require a drug waiver for admission of

one-time marijuana use. The Army and Navy also decreased the per-

centage of waivers in the early 1990s. The Air Force followed an oppo-

site trend by increasing the number of waivers in the early 1990s

(from 2.0 to 6.7 percent of accessions).

These trends demonstrate that the Air Force might be quite different

from the other Services in its need for, and use of, waivered recruits.

The Air Force is the most selective of the four Services in terms of

aptitude test scores. Based on these scores, the smallest percentage of

the youth population is eligible to serve in the Air Force, in compari-

son to the other Services [2]. The civilian economy was growing fairly

rapidly during the 1990s, so the Air Force likely competed with the

civilian sector for high-aptitude recruits. The other three Services, in

contrast, were trying to shrink during the early and mid-1990s in reac-

tion to the end of the Cold War. These overall trends suggest that

each Service has its own patterns and should be analyzed separately.

Performance of waivered recruits

We briefly summarize past findings on the performance of waivered

recruits in the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps.

2

We then discuss the

one previous study that considers all four services. This section ends

with conclusions about what this previous work means for our current

analyses.

Army

A 2008 Naval Postgraduate School thesis by Distifeno looked at the

effects of enlistment waivers on Soldiers’ first-term attrition [10]. This

study found that the success of waivered recruits varied depending on

2. Likely because of the relatively small size of the USAF waivered popula-

tion, we found no studies evaluating the performance of waivered

recruits in the Air Force.

12

when success was measured. For example, Distifeno found that attri-

tion rates for waivered Soldiers were lower than for nonwaivered Sol-

diers at the beginning of the first term, but they were higher at the

end of the first term. This study also found differences in attrition

rates based on the type of offense waivered. Specifically, Distifeno

found that recruits with serious traffic and minor non-traffic-related

waivers had lower attrition rates, especially early attrition rates.

Recruits with serious non-traffic-related and felony waivers (for such

offenses as aggravated assault, breaking and entering, and carjack-

ing) seemed to be driving the general conduct waiver attrition pat-

tern—lower attrition rates at first, but higher attrition rates by the end

of the first term.

Distifeno also reported that waivered Army recruits had more disci-

plinary problems and faced more courts-martial than nonwaivered

recruits. Apparently, the pattern of pre-enlistment offenses mattered

because the study found that recruits with a pattern of minor offenses

were more likely to misbehave than those who had only a single major

offense.

Other Army studies have shown that waivered recruits can have vary-

ing levels of success. A 2008 study, for example, examined the perfor-

mance of 276,231 USA recruits from FY03 to FY06. Nearly 18,000 of

these recruits had enlistment waivers. According to the Associated

Press (in an ArmyTimes article [4]), the study found that Soldiers with

enlistment waivers had higher rates than their nonwaivered counter-

parts of desertion, misconduct, court-martial appearances, and alco-

hol rehabilitation failure:

• Desertion (4.3 vs. 3.6 percent)

• Misconduct (6.0 vs. 3.6 percent)

• Court-martial appearances (1 vs. 0.7 percent)

• Alcohol rehabilitation failure (0.3 vs. 0.1 percent).

However, the article also stated that the Soldiers with waivers:

• Were more likely to reenlist (28.5 vs. 26.8 percent)

• Promoted faster to sergeant (34.7 vs. 39 months, on average)

13

• Had a lower rate of dismissal for personality disorders (0.9 vs.

1.1 percent)

• Had a lower rate of dismissal for unsatisfactory performance

(0.3 vs. 0.5 percent).

These Army findings have two implications. First, it is important to

look at the attrition rates of waivered recruits at multiple points in

time because short-term and long-term results may be quite different.

Second, a thorough assessment of the performance of waivered

recruits should consider both negative performance indicators (e.g.,

desertion and misconduct rates) and positive indicators (e.g., speed

to promotion).

Navy

There have been many studies on the performance of waivered USN

recruits; we discuss two in this subsection. Reference [11] looked at

the attrition rates of USN waivered recruits from FY95 to FY96. Using

both logistic regression and classification trees in its analyses, the

study found that:

[enlistment] waivers do have a significantly higher rate of

unsuitable attrition than that of recruits without [enlist-

ment] waivers … [and] that recruits who are not high

school graduates and receive [an enlistment] waiver are the

most likely unsuitable attrition losses.

Reference [12] examined 36-month attrition for recruits in all Ser-

vices who completed the National Guard Youth ChalleNGe Program.

The authors found the following:

1. Heavy smokers, recipients of General Education Development

(GED) certificates, and high school dropouts were most likely

to attrite.

2. Although a USN waiver predicted attrition, it was not as strong

a predictor as being a heavy smoker, a GED recipient, or a high

school dropout.

3. Number of months in the delayed entry program (DEP) was a

significant predictor of 36-month attrition—shorter periods in

14

DEP were associated with greater attrition, whereas longer DEP

periods were associated with lower attrition.

4. The effect of having a waiver varied considerably across the Ser-

vices. The marginal effect of an Army waiver was very small (0.5

percentage point), but the effect for the Navy was considerably

larger (5.6 percentage points).

Marine Corps

In his Naval Postgraduate School thesis, Etcho analyzed the relation-

ship between demographic characteristics, enlistment waivers, and

first-term “unsuitability attrition” in the Marine Corps [13].

3

Etcho

defines unsuitability attrition as Marines who serve fewer than 4 years

of active duty and are separated for "failure to meet minimum behav-

ioral or performance criteria.” Examples of unsuitability attrition

include fraudulent enlistment, motivational problems, behavior dis-

order, financial irresponsibility, unsatisfactory performance, miscon-

duct, and drug use.

4

This study used data from the Defense Manpower Data Center

(DMDC) for USMC cohorts FY88 through FY91; each cohort ranged

from 28,000 to 34,000 recruits per year. Waivered recruits included

those who had prior involvement with law agencies (minor and seri-

ous traffic offenses, non-traffic-related offenses, serious offenses, and

felony offenses) or past drug or alcohol abuse. At the time of Etcho's

3. CNA has analyzed the performance of waivered USMC recruits several

times in the past, but results were presented in informal memoranda

and briefings (i.e., they are not citable).

4. Separation codes, however, have been found to be unreliable in gen-

eral. In the case of FY99–FY09 bootcamp separations, for example, 60

different separation codes were used, but 5 codes represented 91 per-

cent of the separations. This suggests that data entry may be inaccurate

or that it may be difficult to distinguish different separation reasons. In

addition, losses often occur for more than one reason, but only one

code can be used, and there is no predefined hierarchy. As a result, it is

unclear which code should be used, and this decision is left to the data

entry clerk [14].

15

study, about 60 percent of all USMC accessions were receiving enlist-

ment waivers.

The study found that the demographic groups with the highest pre-

dicted probability of unsuitability attrition for the combined USMC

cohorts were:

• Nongraduates of high school

• Recruits from mental categories IV, IIIB, or IIIA (in that

order)

5

• Black recruits.

Demographic characteristics associated with lower probability of

unsuitability attrition included:

• Hispanic recruits

• Male recruits

• Younger recruits.

The study also analyzed which categories of enlistment waivers were

the most (and least) likely to have unsuitability attrition. The catego-

ries of recruits most likely to attrite for unsuitability were those with:

• Felony waivers

• Drug waivers

• Less than three minor non-traffic-related waivers

• Serious offense waivers

• Alcohol waivers.

However, the study did not find a significant relationship between

other categories of enlistment waivers, such as those for three or

more minor non-traffic-related offenses.

5. These mental categories are based on AFQT scores. Specifically, cate-

gory IV recruits are those who scored between 10 and 30 on the AFQT,

while IIIB includes those scoring between 31 and 49, and IIIA includes

those scoring between 50 and 64.

16

Based on these findings, the study recommended that the Marine

Corps deny enlistment to anyone with a felony conviction. It also rec-

ommended denial of enlistment to anyone who would require a

waiver for serious offenses, drug/alcohol use, or less than three

minor non-traffic-related offenses. In FY08, however, implementing

all but the minor offense restriction would have reduced accessions

from 36,546 to 23,630 recruits (35 percent)—mostly because of the

Marine Corps’ use of drug waivers.

The study found that the strength of the relationship between waiver

category and attrition varies depending on the type of waiver granted.

Recruits with felony waivers were much more likely to attrite than

those with alcohol waivers, for example. This study suggests that our

work must distinguish the performance of recruits in different waiver

categories and must quantify the strength of the relationship between

waivers status and performance outcomes.

A DoD-wide study

In 2004, Putka et al. of the Human Resources Research Organization

evaluated the effects of moral waivers on attrition and “in-service devi-

ance” in each of the Services [15]. They found that 18-month attri-

tion rates were higher for those with moral conduct waivers, with

Service-by-Service variation in which types of waivered recruits were

most likely to attrite. While Drug/Alcohol Test Positive (DAT) waivers

were highly predictive of attrition behavior in all Services, adult

felony and serious non-traffic-related waivers were important predic-

tors in the Army, and waivers for marijuana use and serious non-

traffic-related waivers were significant in the Navy. The authors also

found marijuana use waivers and serious non-traffic-related waivers to

be significant predictors of 18-month attrition in the Marine Corps.

In the Air Force, however, only adult felony waivers were found to

have a positive impact on 18-month attrition. Their tests of in-service

deviance were conducted only for the Marine Corps and the Army.

Putka et al. found a higher prevalence of deviances among waivered

recruits in the Marine Corps, but no significant difference in the

Army.

17

Implications of previous research for this study

This brief overview of previous research shows that there are several

important factors to consider in our analyses of the effects of waivers

on military performance. Specifically, our analyses:

1. Should be primarily within Service since waiver policies were

different between Services until 2008

2. Should consider both short-term and long-term effects of

waiver status on performance because groups that perform well

in the short term do not always perform well in the long term

3. Should include both positive and negative effects of waiver sta-

tus, preferably using the same metric, because waivers have

been associated with both positive and negative performance

4. Should compare the performance of waivered recruits with

that of other relevant recruits, such as those who lack a tradi-

tional high school diploma

5. Should consider the effect of multiple waivers on performance

since previous research has not addressed this issue.

Keeping these insights in mind, the next sections describe our

research sample, methodology, and findings.

18

This page intentionally left blank.

19

Data

The data in this study are from four source files. DMDC provides

three: the accession file based on Military Entrance Processing Com-

mand (MEPCOM) transactions, the active-duty master file (quarterly

snapshots), and the active-duty transaction file. We supplement the

analysis using data from CNA’s military personnel files.

From the MEPCOM accession file, we extract data for FY99 through

FY08 for each Service. Any information about a Servicemember col-

lected at accession comes from this file, including AFQT score,

months spent in DEP, race/ethnicity, age, and waivers. We include

only non-prior-service (NPS) accessions because it is important to be

able to track Servicemembers’ careers and estimate their service

lengths. In addition, our analysis relies only on whether a recruit has

any waiver or a particular type of waiver, not a count of the number of

waivers he/she has.

6

Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of waivered

recruits accessed with any type of waiver in each Service. Throughout

the sample period, we see that the percentage of waivered recruits

generally fell in the Marine Corps, the Navy, and the Air Force, while

increasing in the Army.

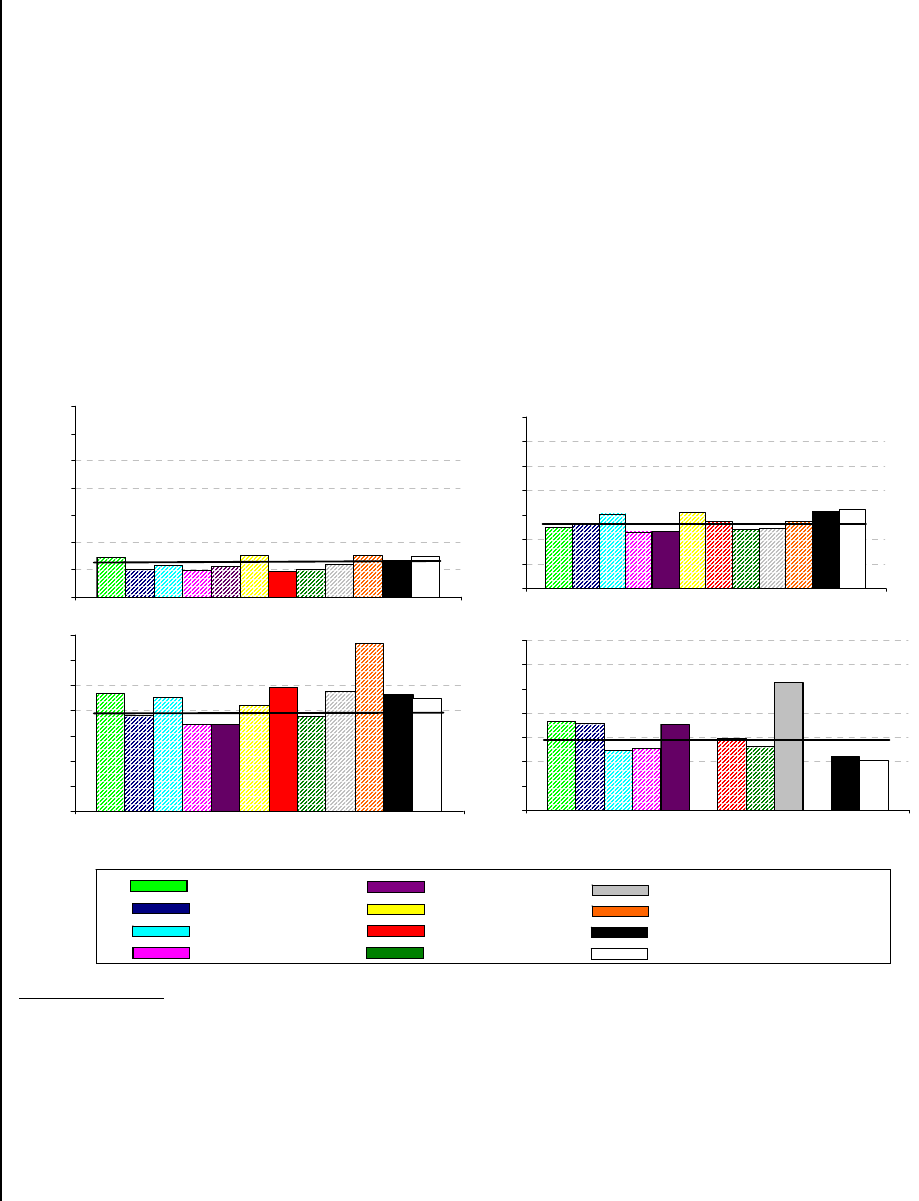

Figure 2 shows intra-Service time trends by waiver type. We find sig-

nificant variation within each branch. The increase in USA waivered

accessions, for example, can be explained mainly by the increased

prevalence of serious and physical waivers. Figure 2 also shows that

the higher percentage of waivered recruits in the Marine Corps is

mainly a result of its stricter drug policy. Roughly 30 percent of USMC

accessions have required a drug/alcohol waiver over time.

6. The MEPCOM file contains separate DEP and accession waivers, and a

maximum of three data fields for each. MEPCOM advised us that, in the

case of the multiple waivers, some of the waivers that were recorded in

a recruit’s DEP section were carried over to his/her accession waiver

section—in essence, resulting in double-counting for that recruit.

20

The remaining data components for the study are the active-duty

master file, the active-duty transaction file, and CNA’s military per-

sonnel files. The active-duty master file tracks NPS accessions quar-

terly through time, so we can identify if (and when) a recruit attrited.

The active-duty transaction file provides loss reasons, which were used

to help define attrition. Not all losses are “bad losses” and thus should

not be considered attrites. We did not want to categorize, for exam-

ple, those enlisted members who are “lost” because of a transition to

officer training programs or because they reached their end of active

obligated service (EAOS).

Figure 1. Percentage of waivered recruits by Service: FY99 through FY08

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

Accession FY

Percentage of recruits with at least one

waiver

USA USAF USMC USN

21

Figure 2. Trends in waivered accessions FY99 through FY08, by waiver type

a

a. At the Navy’s request, education waivers are reported separately for that Service (they are included in the “other waiver” category

for all other Services).

Army

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

20%

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

FY of accession

Percentage of recruits with a

waiver

Air Force

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

20%

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

FY of acce s sion

Percentage of recruit s with a

waiver

Marine Corps

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

FY of access ion

Percen tag e of recruit s with a

waiver

Navy

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

20%

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

FY of accession

Percentage of recruits with a

waiver

Physical

Ment al

Drug / Alcohol

Test Positive

Dependents

Adult Felony

Juvenile Felony

Ser ious

Edu c at i o n

Other

Army

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

20%

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

FY of accession

Percentage of recruits with a

waiver

Air Force

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

20%

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

FY of acce s sion

Percentage of recruit s with a

waiver

Marine Corps

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

FY of access ion

Percen tag e of recruit s with a

waiver

Navy

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

20%

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

FY of accession

Percentage of recruits with a

waiver

Physical

Ment al

Drug / Alcohol

Test Positive

Dependents

Adult Felony

Juvenile Felony

Ser ious

Edu c at i o n

Other

22

This page intentionally left blank.

23

Characterizing waivered and nonwaivered

recruits

In this section, we compare the average characteristics of waivered

and nonwaivered recruits in each Service. We compare how they

differ on a variety of demographic and military characteristics, includ-

ing education, marital status, age, gender, time spent in DEP, and

paygrade at accession. In addition, we compare the geographic areas

from which these populations originate. We find a variety of signifi-

cant differences in the characteristics of waivered and nonwaivered

recruits—differences that we ultimately consider when we compare

performance metrics and attrition behavior across these groups.

We present differences across the groups that have any waiver vice no

waiver, and we do not differentiate by waiver type. As expected, the

groups are systematically different; these findings motivate our analy-

sis of behavioral differences in the two populations. Table 2 summa-

rizes our findings for a number of demographic characteristics.

7

Across Services, waivered recruits are more likely to be male, married,

older, and white than their nonwaivered counterparts.

As noted in table 2, we also find that waivered recruits are less likely

to hold traditional high school diplomas and more likely to be Tier II

recruits. They also are more likely to be Tier III in the Army, while less

likely in the Navy, and the difference was insignificant in the Air Force

and Marine Corps. Figure 3 displays the percentages of waivered and

nonwaivered recruits in each Service that are not Tier I (i.e., that are

either Tier II or Tier III).

7. Appendix A shows the values for these variables and the magnitude of

differences across the waivered and nonwaivered populations.

24

The percentage of Tier II/III is higher in the waivered population in

all Services, though only barely so for the Air Force. The main reason

for the large and significant difference between the percentages of

Tier II/III recruits in the waivered and nonwaivered populations in

the Navy is that the Navy grants education waivers to nearly half of its

Tier II/III recruits. Over the sample period, while the Navy granted

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of waivered vice nonwaivered recruits, by Service

Characteristic USA USAF USMC USN Waivered recruits are

Gender More likely

male

More likely

male

More likely

male

More likely

male

More likely male

Age Older Older Older Older Older

Ethnicity More likely

white

More likely

white

More likely

white

More likely

white

More likely white

Marital status More likely

married

More likely

married

More likely

married

More likely

married

More likely married

High school degree

graduate (HSDG)

Less likely Less likely Less likely Less likely Less likely

Nontraditional HSDG

a

More likely More likely More likely More likely More likely

Tier II More likely More likely More likely More likely More likely

Tier III More likely No diff. No diff. Less likely Inconclusive

a. Nontraditional HSDGs have a homeschool or adult education diploma, or have completed 1 semester of college.

Figure 3. Percentages of waivered and nonwaivered Tier II/III recruits, by Service (FY99–FY08)

0

5

10

15

20

25

Army Navy Marine

Corps

Air Force

Percentage

Waivered

Non-waivered

25

roughly 15,000 education waivers, the corresponding numbers in the

Army, Marine Corps, and Air Force were 14, 445, and 13, respectively.

Service-specific trends in the percentage of yearly accessions who are

Tier II/III are presented in figure 4. In all years, Tier II/III accessions

were highest in the Army, followed by the Navy, Marine Corps, and

Air Force.

We also find, as shown in figure 5, that waivered recruits, on average,

spend less time in DEP than their nonwaivered counterparts. This dif-

ference, which is consistent and significant in all of the Services, is

likely correlated with the fact that waivered recruits are more likely to

be shipped directly to basic training. That is, in all Services, the per-

centage of waivered recruits that access during the JJAS (June, July,

August, September) trimester is smaller than the corresponding per-

centage in the nonwaivered population. They are less likely to be

recruited as far in advance as traditional high school diploma gradu-

Figure 4. Percentages of Tier II/III recruits, by Service and accession FY (FY99–FY08)

a

a. The significant decline in the percentage of Tier II/III recruits in the Army from 1999-2000 is as reported in the

Enlisted Master File. We note that the precipitous drop seems unlikely and may indicate data entry errors. Results

specific to FY99 for the Army should thus be interpreted with caution.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

Accession FY

Percentage

Army

Nav y

Marine Corps

Air Force

26

ates and, therefore, spend significantly less time in DEP. This also

may suggest that, in all Services, if ship dates are approaching and

incoming cohorts are still insufficient, there is more flexibility and an

increasing number of those who would require a waiver are accepted.

Finally, we examine whether waivered recruits are more or less likely

than nonwaivered recruits to come from particular regions of the

country.

8

We find, overall, that waivered recruits are more likely to

come from the East North Central region and less likely to come from

the Pacific and Mid-Atlantic regions than their nonwaivered counter-

parts. These findings are consistent across all Services. In addition,

for all Services except the Marine Corps, waivered recruits are more

likely to come from the West South Central, West North Central, and

Mountain regions. With the exception of the Marine Corps, waivered

recruits also are underrepresented in the South Atlantic and East

South Central regions. As evidenced by these trends, recruiting is

Figure 5. Average number of months spent in DEP (FY99–FY08)

8. Appendix B contains our methodology and detailed findings.

2.9

5.2

5.6

4.9

1.9

3.9

4.2

4.0

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

USA USN USMC USA F

Months in DEP

No w aiv er

Waiver

27

more difficult in some areas of the country than others. As a result,

recruiters in some regions find it necessary to make more “exceptions

to policy” via waivers to meet their recruiting missions.

These findings suggest a variety of theories as to how the performance

of waivered and nonwaivered recruits may differ, which will be

explored in this study. On one hand, the fact that waivered recruits

tend to be older and married, for example, suggests that they may

have more stability in their personal lives, potentially allowing them

to devote more energy to their careers and, hence, be less likely to

attrite. On the other hand, they tend to have nontraditional high

school diplomas, a characteristic that is correlated with poorer per-

formance and higher attrition. In addition, waivered recruits’ higher

likelihood to access at the rank of E1 in the Army and Marine Corps

indicates that they are not among the highest performers at boot-

camp (see appendix A).

9

Similarly, the fact that waivered recruits

spend less time in DEP suggests that they may have higher attrition

risk.

10

The fact that these groups have differing demographic, geographic,

and military characteristics suggests that they also may differ in unob-

servable ways. Taste for long-term service or career stability, political

affiliation, and overall personal motivation are but a few examples.

Such differences would likely cause members of these groups to

behave differently. Knowledge of how these groups differ is used to

inform the analysis in the remaining sections, where we estimate attri-

tion probability and performance metrics for both the waivered and

nonwaivered populations.

9. Those recruits with stellar bootcamp performance are often accessed at

the rank of E2. In addition, some in the nonwaivered population are

promised the E2 rank prior to arrival at bootcamp.

10. For a discussion of the relationship between time in DEP and attrition,

see [16].

28

This page intentionally left blank.

29

Determinants of attrition

In this section, we compare the attrition behavior of waivered and

nonwaivered recruits. Early attrition—defined as early termination of

a Servicemember’s contract—occurs for a variety of reasons, includ-

ing involuntary discharge, early retirement, and involuntary separa-

tion. As discussed earlier, we do not consider a Servicemember to

have attrited if his or her loss was for a “good” reason, such as transi-

tion to the officer corps, reaching EAOS, or a reduction in force.

11

The Services view early attrition as problematic and costly because

they fail to receive the full return on their training investments and,

in a time of high demand, must replace attriting Servicemembers. In

this section, we evaluate how the attrition behavior of waivered

recruits differs from that of their nonwaivered counterparts, and we

explore feasible methods for narrowing any gap. We begin by com-

paring average attrition rates across the waivered and nonwaivered

populations. We then present findings on which waiver types are the

most likely to attrite and whether, after controlling for other observ-

able characteristics, recruits with certain waivers are still significantly

more likely to attrite. Finally, we determine the predictors of attrition

given a particular waiver type. This will allow us to advise the Services

as to how to minimize attrition risk within their waivered populations.

Average attrition rates: how do waivered groups compare?

Here, we evaluate the validity of the assumption that waivered recruits

attrite at higher rates than their nonwaivered counterparts. After con-

trolling for demographics and other characteristics, we calculate—at

various points in time—the marginal effect of particular waivers on

attrition. This lets us evaluate whether waivered groups share

unobservable characteristics that affect their attrition risk. We also

11. While a reduction in force may not be considered a “good” thing, it is

certainly legitimate because it is beyond the Servicemember’s control.

30

estimate the expected probability of attrition for each waivered

group.

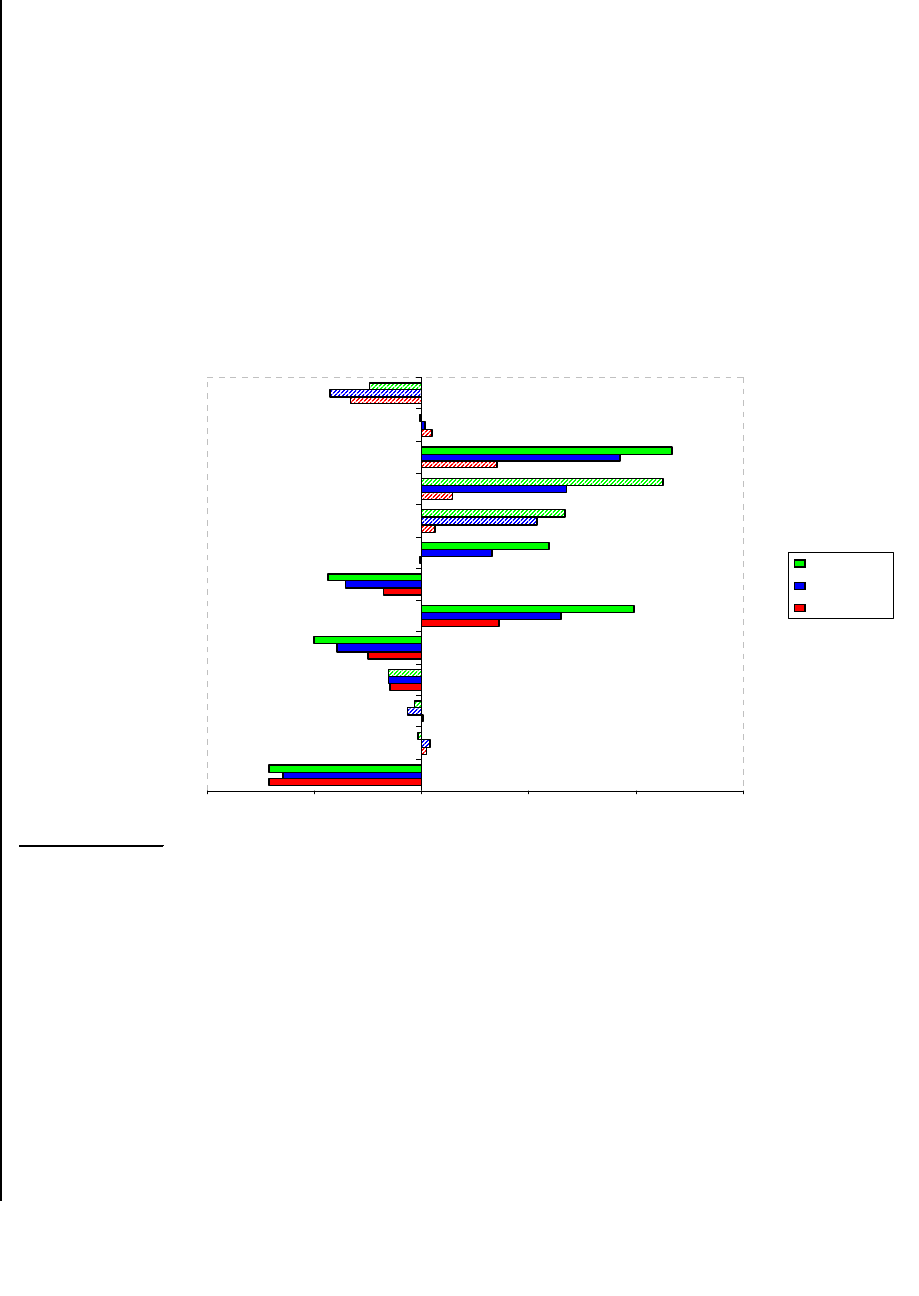

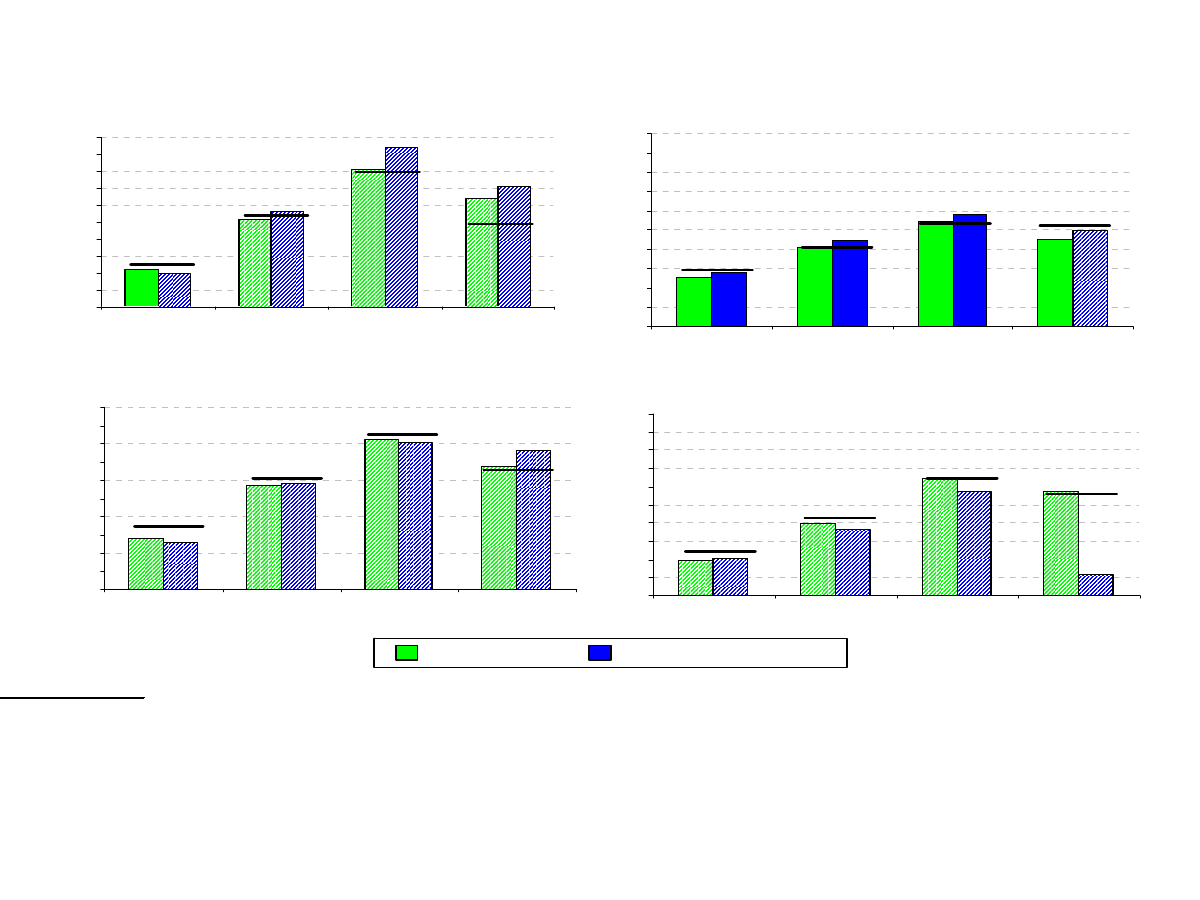

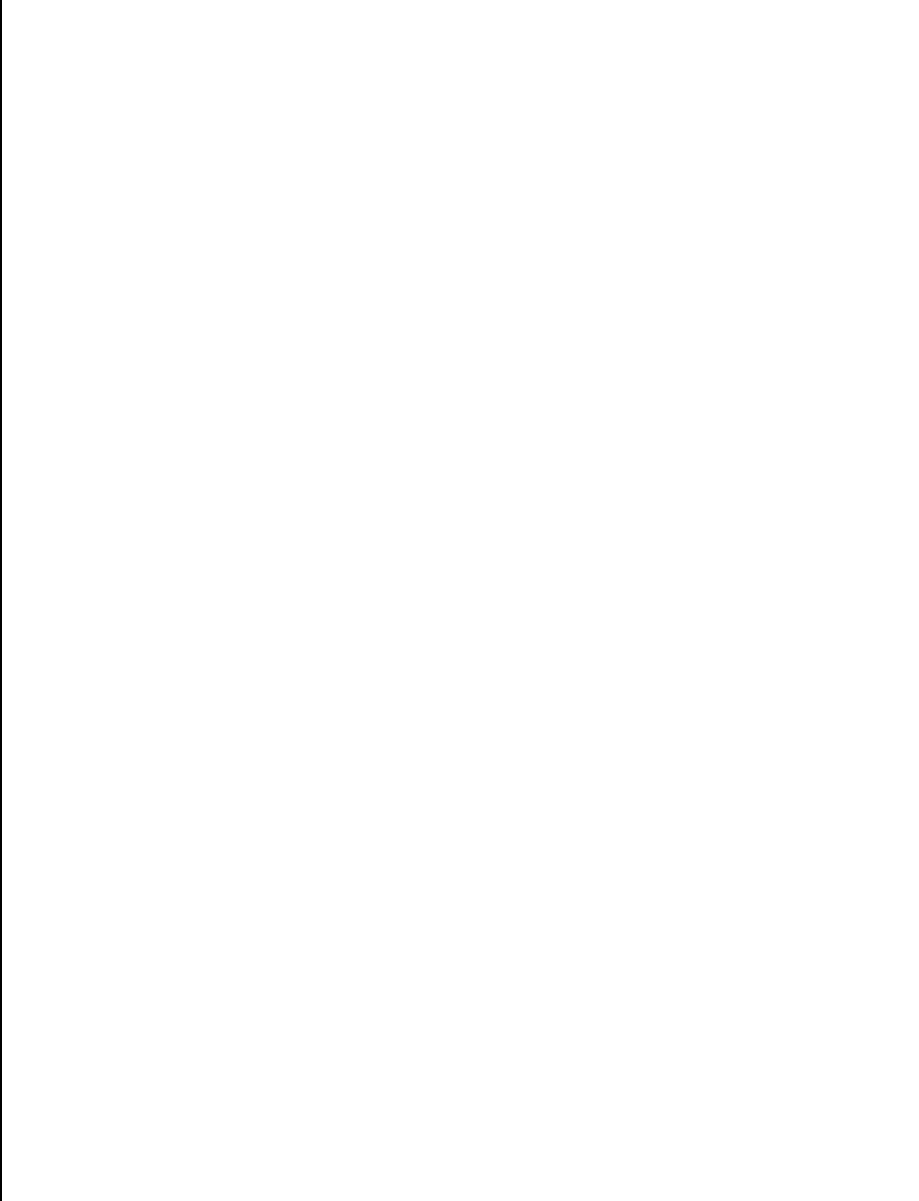

Figures 6 through 9 show average attrition rates at various points in

time (from 6 to 48 months) for the waiver subpopulations in each Ser-

vice.

12

In all Services, and for all waiver groups (including those with-

out waivers), attrition rates increase with time. That is, the percentage

of those who attrite by 48 months is greater than the percentage of

those who attrite by 36 months, which is greater than the percentage

of those who attrite by 24 months, and so on, down to those who

attrite by 3 months (while in bootcamp). This is to be expected; the

likelihood of a Servicemember attriting increases with time in service.

There are differences, however, among the Services, as to which

waivered groups tend to be the most and least likely to attrite. In the

Army, for example, those with a drug/alcohol, DAT, or aptitude

waiver (for recruits with insufficient ASVAB scores) are the most

likely to attrite. Those with adult felony waivers have the lowest attri-

tion, followed by those without waivers (see figure 6). In the Navy,

attrition is highest for DAT and education waivers; attrition is lowest

for those with no waiver, followed by physical and adult felony waivers

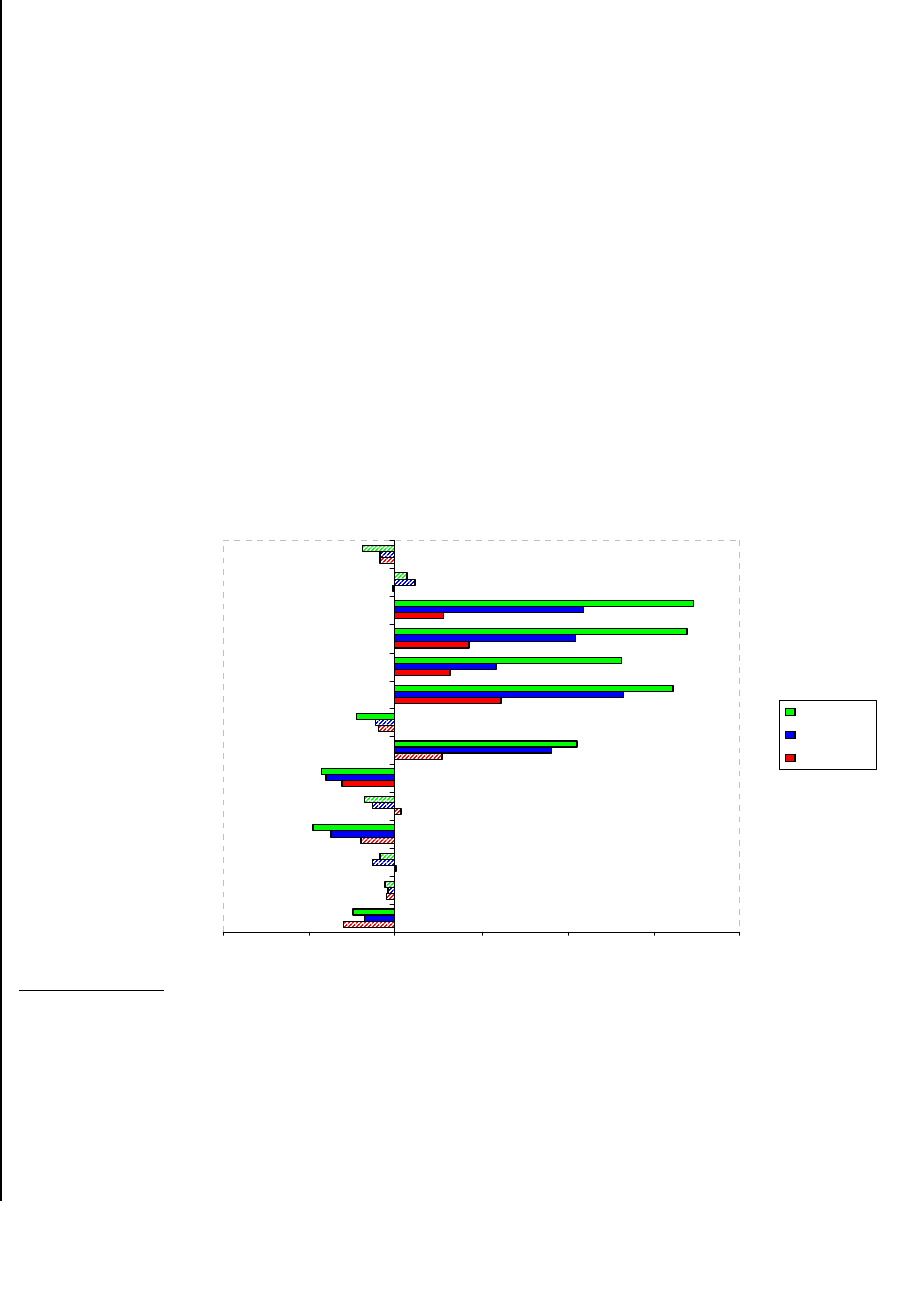

(see figure 7). In the Air Force, those with aptitude waivers tend to

have the highest attrition, whereas those with a physical waiver,

dependents waiver, or no waiver are the least likely to attrite (see

figure 8).

Finally, in the Marine Corps, those with DAT, aptitude, or adult

felony waivers are the highest attriters (see figure 9). Those accessed

without waivers are the lowest attriters at all points in time. Note that

recruits accessed without waivers do not necessarily have the lowest

attrition risk in each Service. In addition, Tier II and III recruits, in

most cases, have average attrition rates as high as, or higher than,

those in the waivered population. There are a few exceptions. Those

accessed with DAT waivers, for example, are more likely than Tier II

or III recruits to attrite by 48 months in the Army and Navy, and by 6

months in the Air Force. In addition, those with drug/alcohol waivers

12. For the calculation of 48-month attrition, we include only those whose

contracts were for at least 4 years.

31

Figure 6. Attrition by waiver category: Army

Figure 7. Attrition by waiver category: Navy

a

a. Education waivers are included in our analysis for the Navy only, at its request. This waiver was not issued suffi-

ciently in the other Services to warrant its inclusion.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Physical

Aptitude

Drug / Alcohol

DA test positive

Dependents

Adult felony

Juvenile felony

Serious

Other

No waiver

Tier II/III

Tier II/III with no waiver

Tier II/III with waiver

6 Months

24 Months

48 Months

waiver types

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Physical

Aptitude

Drug / Alcohol

DA test positive

Dependents

Adult felony

Juvenile felony

Serious

Other

No waiver

Tier II/III

Tier II/III with no waiver

Tier II/III with waiver

6 Months

24 Months

48 Months

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Physical

Aptitude

Drug / Alcohol

DA test positive

Dependents

Adult felony

Juvenile felony

Serious

Other

No waiver

Tier II/III

Tier II/III with no waiver

Tier II/III with waiver

6 Months

24 Months

48 Months

waiver types

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Physical

Aptitude

Drug / Alcohol

DA test positive

Dependents

Adult felony

Juvenile felony

Serious

Other

Education

No waiver

Tier II/III

Tier II/III no waiver

Tier II/III with waiver

6 Months

24 M onths

48 M onths

waiver types

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Physical

Aptitude

Drug / Alcohol

DA test positive

Dependents

Adult felony

Juvenile felony

Serious

Other

Education

No waiver

Tier II/III

Tier II/III no waiver

Tier II/III with waiver

6 Months

24 M onths

48 M onths

waiver types

32

Figure 8. Attrition by waiver category: Air Force

Figure 9. Attrition by waiver category: Marine Corps

a

a. As of mid-FY09, the USMC is no longer accepting recruits who require a DAT waiver.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Physical

Aptitude

Drug / Alcohol

DA test positive

Dependents

Adult felony

Juvenile felony

Serious

Other

No waiver

Tier II/III

Tier II/III no waiver

Tier II/III with waiver

6 Months

24 Months

48 Months

waiver types

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Physical

Aptitude

Drug / Alcohol

DA test positive

Dependents

Adult felony

Juvenile felony

Serious

Other

No waiver

Tier II/III

Tier II/III no waiver

Tier II/III with waiver

6 Months

24 Months

48 Months

waiver types

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Physical

Aptitude

Drug / Alcohol

DA test positive

Dependents

Adult felony

Juvenile felony

Serious

Other

No waiver

Tier II/III

Tier II/III no waiver

Tier II/III with waiver

6 Months

24 Months

48 Months

waiver types

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Physical

Aptitude

Drug / Alcohol

DA test positive

Dependents

Adult felony

Juvenile felony

Serious

Other

No waiver

Tier II/III

Tier II/III no waiver

Tier II/III with waiver

6 Months

24 Months

48 Months

waiver types

33

in the Army have higher 24- and 48-month attrition rates than those

in the Tier II/III population.

Although these attrition differences across waivered groups may pro-

vide insights on quality differences of recruits within each Service,

these trends should not be compared across Services because of sig-

nificant variations in Service waiver policies. It cannot, for example,

be concluded that recruits with a drug/alcohol waiver in the Army are

of worse quality than those with a drug/alcohol waiver in the Marine

Corps. Although tempting to jump to this conclusion (since 48-

month attrition rates for Servicemembers with drug/alcohol waivers

are greater than 50 percent in the Army but 25 percent in the Marine

Corps), this assumes that a recruit accessed into the Marine Corps

with a drug/alcohol waiver would require the same waiver in the

Army. Because of differential waiver policies, this is not the case.

Figure 10 tells a similar story to that of figures 6 through 9. It displays

the difference in average attrition probabilities for the waivered and

nonwaivered populations in each Service. (These values are calcu-

lated as the mean 6-, 24-, and 48-month attrition rates for those with

any waiver minus the corresponding attrition rate for those without,

regardless of the number of waivers or waiver type.)

Figure 10. Difference in attrition probabilities (waivered minus nonwaivered)

a

a. All differences displayed are significant, except Air Force 6-month attrition and Army 24-month attrition.

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

6-month

attrition

24-month

attrition

48-month

attrition

Army

Navy

Marine Corps

Air Force

34

We find that waivered recruits in the Army have lower attrition rates

at 6 months, but higher at 48 months, than their nonwaivered coun-

terparts. Conversely, waivered recruits attrite more frequently at all

time intervals in both the Navy and Marine Corps. Finally, Air Force

waivered recruits have higher 24- and 48-month attrition rates, but

there is no significant difference at 6 months. These attrition rate dif-

ferences will be explored in greater detail later, when we evaluate

whether variation in attrition behavior can be explained entirely by

individual characteristics (such as gender, race/ethnicity, paygrade at

accession, and AFQT score) or is the result of other observable or

unobservable characteristics.

Are recruits with multiple waivers riskier accessions?

The attrition rates presented thus far focus exclusively on whether a

Servicemember has any waiver and on whether he or she has a partic-

ular type of waiver, without making any distinction between those who

have only one waiver and those who have multiple waivers. We also

evaluate whether those with multiple waivers are more likely to be

either a greater attrition risk or a poorer performer than those with

only one waiver. We conduct both an aggregate analysis—comparing

the average attrition rates and E5 promotion rates of those accessed

with one, two, or three or more waivers—and a more detailed analy-

sis, in which we compare these same metrics across the ten most

common waiver combinations within each Service.

13

In sum, there are a few waiver combinations (highlighted in italics in

what follows) that we find to be particularly risky in each Service, and

some stand out as not imposing that much additional risk:

13. Appendix C contains a detailed description of our methodology and

findings. As previously mentioned, MEPCOM acknowledges that some

waivers may be double-counted (as both a DEP waiver and an accession

waiver). Because of this, we may have counted some recruits who have

only one waiver as having two. In an effort to avoid these potential

errors, we focus on waiver pairs. If a waiver was double-counted, the

same waiver type should appear twice on the recruit’s record. By focus-

ing on recruits with more than one waiver type, we avoid the potential

for data error.

35

• Army

— Medical and serious: lower 24- and 48-month attrition, higher

percentage are fast to E5

14

— DAT and serious: less likely to attrite at 6 months, more likely

at 48

• Navy

— Serious and education: higher 24- and 48-month attrition

— Other and education: higher 6-, 24-, and 48-month attrition

— Dependents and serious: more likely to be fast promoters

• Marine Corps

— Drug/alcohol and medical: higher attrition at all intervals and

less likely to promote fast

— Drug/alcohol and DAT: higher attrition at all intervals

— Medical and serious: higher attrition at all intervals

— Dependents and drug/alcohol: higher attrition at all intervals,

but more likely to promote fast

• Air Force

— Medical and aptitude: higher attrition at all intervals and less

likely to promote fast to E5

— Adult felony and serious: more likely to be fast promoters, but

no significant attrition difference.

The Services should keep this information in mind when determin-

ing which waiver combinations to prioritize (in terms of accessions)

and which should require additional screening.

14. A detailed discussion of our methodology for determining whether a

Servicemember promoted “fast to E5” is discussed in appendix D and

documented in [17].

36

Does attrition vary by waiver type?

In this subsection, we estimate the effect of being in a certain waiver

group on the probability of attrition (at 6, 24, and 48 months), after

controlling for a variety of other factors that are known to determine

a recruit’s attrition risk. Specifically, we control for a variety of demo-

graphic and military characteristics, including geographic region of

origin, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, number of children, AFQT

score, months spent in DEP, education, gender, and FY of accession.

We also control for whether a recruit has more than one waiver since

we found that those with multiple waivers do behave differently than

those with only one waiver. We then estimate the effect of a recruit

being in a particular waiver group (or having any waiver) on attrition

probabilities, taking all of these factors into consideration.

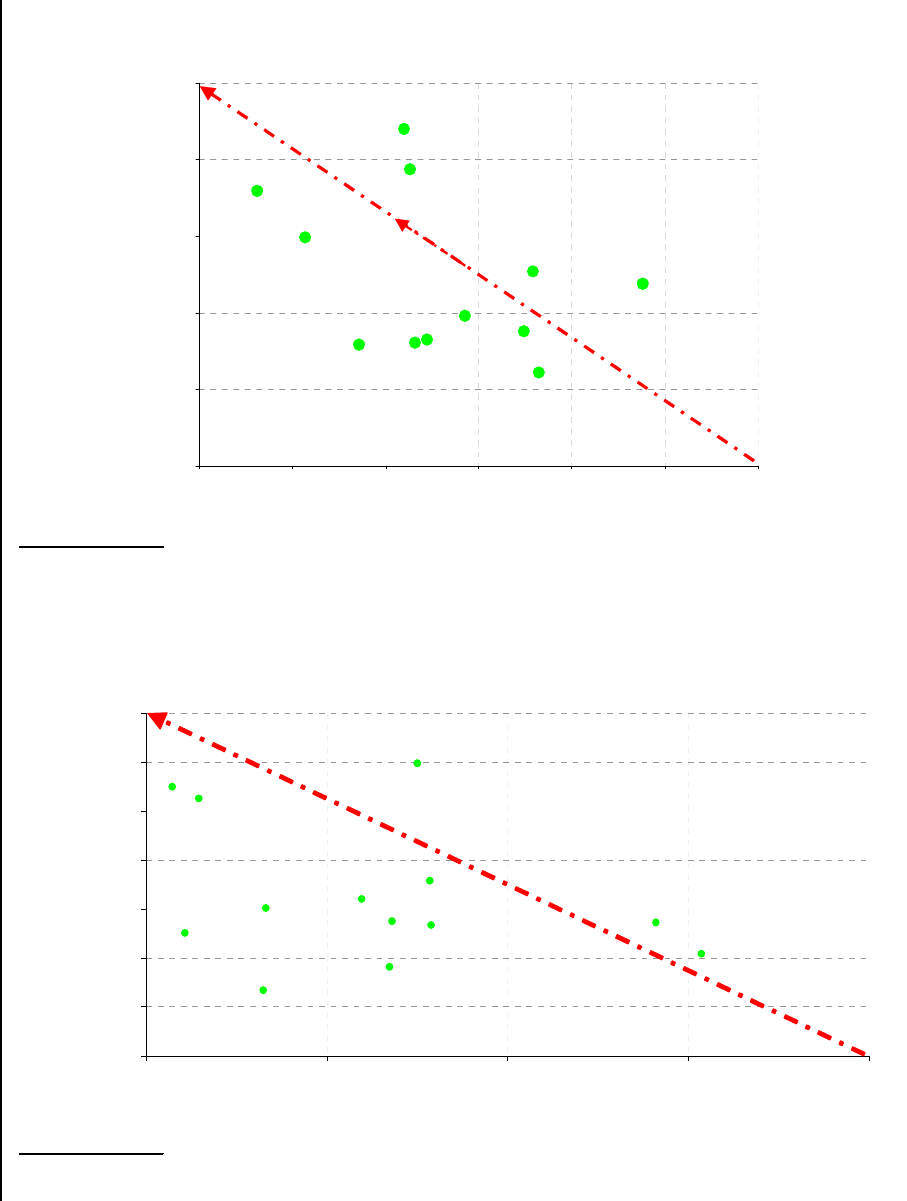

Army

Figures 11 through 14 present the independent effects of particular

waiver types. The marginal effects presented are the effect from being

in a particular waiver group (or having a particular characteristic) on

the probability of attrition, all else equal. The ultimate question this

estimation strategy answers is: after controlling for all of these observ-

able characteristics, are members of certain waiver groups still more

likely than their nonwaivered counterparts to attrite? That is, do

members of a particular waiver group share unobservable, behavioral

characteristics that influence their attrition probability?

Figure 11 presents Army findings. The effect of waiver status on short-

term, or 6-month, attrition is—in most cases—negative. Soldiers

accessed with an adult felony waiver are, all else equal, 2.4 percentage

points less likely to attrite by 6 months than their nonwaivered coun-

terparts. Similarly, those accessed with a juvenile felony, serious,

dependents, drug/alcohol, or DAT waiver are all significantly less

likely to attrite by 6 months than those in the nonwaivered popula-

tion. Conversely, those with aptitude or physical waivers have higher

short-term attrition rates, all else equal. The most significant contri-

butions of waiver status on attrition probabilities, however, are for the

24- or 48-month attrition rates of those with a dependents waiver, and

for the 48-month attrition rates of those with a DAT or drug/alcohol

37

waiver. Although those with a dependents waiver are significantly less

likely than their nonwaivered counterparts to attrite at all time inter-

vals, those with a DAT or drug/alcohol waiver are significantly more

likely to attrite by 48 months. For example, all else equal, Soldiers

accessed with a DAT waiver are 12 percentage points more likely to

attrite by 48 months than the nonwaivered. In addition to the mar-

ginal effects of waiver type, these figures also present the effects of

being a Tier II/III recruit (relative to Tier I) and accessing in the

October–January (ONDJ) or February–May (FMAM) trimesters (rel-

ative to JJAS). These are included simply as a comparison, to illustrate

how the marginal effect of waiver status compares with that of other

variables related to attrition. In the Army, the effects of having a

dependents, drug/alcohol, or DAT waiver on 48-month attrition are

significantly greater than these other effects. These findings suggest

that, on average, Army recruits with a dependents waiver have an

inherently low attrition risk, whereas those accessed with a DAT or

drug/alcohol waiver have an inherently high attrition risk.

38

Note that the findings in figures 6 and 11, although different, are not

inconsistent. These two approaches answer somewhat different ques-

tions. The fact, for example, that the independent effect of a having a

dependents waiver is negative and significant (suggesting that, all else

equal, those in this waiver group have a lower attrition probability) is

not inconsistent with the fact that the average attrition probabilities

for this group (refer back to figure 6) are slightly higher than those

in the nonwaivered population. This simply means that the main

attrition drivers in that population are the observable characteristics

we control for, not unobservable, behavioral characteristics associated

with waiver status. This suggests that this (as well as other groups with

these differential effects) is potentially an area for improved screen-

ing. We will discuss this further in a later section.

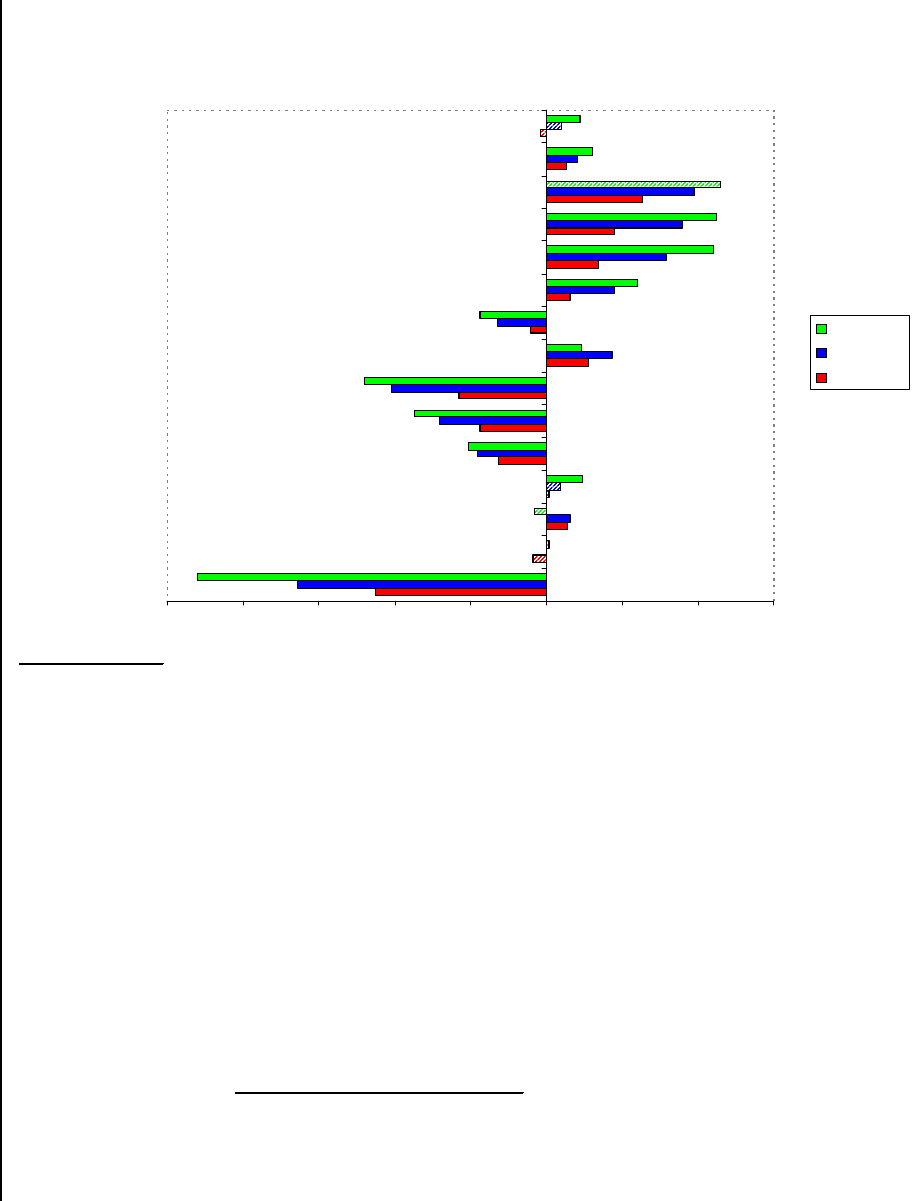

Figure 11. Marginal effects of waivers on 6-, 24-, and 48-month attrition rates: Army

a

a. These marginal effects are the resulting percentage-point changes in the probability of attrition from having a par-

ticular characteristic, all else equal. Marginal effects for each waiver type are the independent effect of that waiver

type relative to accessing without a waiver. Similarly, ONDJ and FMAM marginal effects represent the effect from

accessing in these trimesters relative to JJAS, and the Tier II/III effect is that relative to Tier I. Hatch-marked bars

denote statistical insignificance. All other findings are significant at the 5-percent level or better.

-10 -5 0 5 10 15

ONDJ

FMAM

Tier II/III

Other

Physical

Aptitude

DAT

Drug/Alcohol

Dependents

Serious

Juvenile Felony

Adult Felony

Percentage point impact

48 month

24 month

6 month

Less likely to attrite More likely to attrite

39

Navy

In the Navy, the marginal effect of a particular waiver type on attrition

probabilities, all else equal, is almost always positive, as revealed in

figure 12. The only negative effects are for 6-month attrition, and the

size of these effects is small, generally 1 percentage point or less. The

most sizable effects of waiver status on attrition occur for those with a

serious or DAT waiver. Those with serious waivers, for example, are

4.4 and 7.2 percentage points more likely to attrite by 24 and 48

months, respectively, than their nonwaivered counterparts. The inde-

pendent effect of a DAT waiver on these medium- and long-term

attrition measures is 9.5 and 15 percentage points, respectively. We

conclude, therefore, that those accessed with DAT waivers have inher-

ently high attrition risk. This also is revealed by the fact that the effect

of being in this waiver category on 24- and 48-month attrition rates is

equal to or greater than the effect of being a Tier II/III recruit.

Figure 12. Marginal effects of waivers on 6-, 24-, and 48-month attrition rates: Navy

a

a. These marginal effects are the resulting percentage-point changes in the probability of attrition from having a par-

ticular characteristic, all else equal. Marginal effects for each waiver type are the independent effect of that waiver

type relative to accessing without a waiver. Similarly, ONDJ and FMAM marginal effects represent the effect from

accessing in these trimesters relative to JJAS, and the Tier II/III effect is that relative to Tier I. Hatch-marked bars

denote statistical insignificance. All other findings are significant at the 5-percent level or better.

-4-20246810121416

ONDJ

FMAM

Tier II/III

Other

Physical

Aptitude

Education

DAT

Drug/Alcohol

Dependents

Serious

Juvenile Felony

Adult Felony

Percentage point impact

48 month

24 month

6 month

40

Within the Navy, average attrition rates by waiver type were greatest

for those with education or DAT waivers, as illustrated in figure 7.

These rates are comparable to those of the Tier II/III population

(regardless of waiver status). This suggests that, once accounting for

both observable and unobservable (associated with waiver type) char-

acteristics, those accessed into the Navy with either education or DAT

waivers pose the greatest attrition risk.

Marine Corps

We find similar results within the Marine Corps, presented in figure

13. As with the Navy, DAT waivers have the greatest independent effect

on attrition probabilities. Those accessed with a DAT waiver, for

example, are 5 and 8.4 percentage points more likely to attrite by 24

and 48 months, respectively.

15

They also have the highest average

attrition rate of all waiver types, as was displayed in figure 9. The aver-

age attrition rates of those accessed with DAT waivers are comparable

to those of the Tier II/III population, suggesting that they are an

equally high attrition risk. With the exclusion of those requiring DAT

waivers from the Marine Corps accession pool, the overall attrition

risk of the waivered population should decline, as the independent

effect of all other waiver types is much smaller, at less than 5 percent.

In addition, there are no other waiver groups whose average attrition

15. As of mid-FY09, the Marine Corps is no longer accessing recruits who

require a DAT waiver.

41

rates approach those of the Tier II/III population, as was displayed in

figure 9.

Air Force

Finally, figure 14 reveals the independent effects of waiver status on

attrition at 6, 24, and 48 months for the Air Force. The marginal

effects of waiver status in the Air Force are small—less than 5 percent

for all waiver types and all attrition rates. The effect of having a DAT

waiver is large, but insignificant, because the Air Force granted only

13 DAT waivers over the entire sample period. As figure 14 shows, the

independent effect of being a Tier II/III recruit is much greater than

any of the waiver effects: Tier II/III recruits are more likely to attrite

at 48, 24, and 6 months, by 14, 12, and 4 percentage points, respec-

Figure 13. Marginal effect of waivers on 6-, 24-, and 48-month attrition rates: Marine Corps

a

a. These marginal effects are the resulting percentage-point changes in the probability of attrition from having a par-

ticular characteristic, all else equal. Marginal effects for each waiver type are the independent effect of that waiver

type relative to accessing without a waiver. Similarly, ONDJ and FMAM marginal effects represent the effect from

accessing in these trimesters relative to JJAS, and the Tier II/III effect is that relative to Tier I. Hatch-marked bars

denote statistical insignificance. All other findings are significant at the 5-percent level or better.

-10-5 0 5 1015

ONDJ

FMAM

Tier II/III

Other

Physical

Aptitude

DAT

Drug/Alcohol

Dependents

Serious

Juvenile Felony

Adult Felony

Percentage point impact

48 month

24 month

6 month

Less likely to attrite More likely to attrite

42

tively, than a comparable Tier I recruit. Due to the small size of the

Air Force DAT population, this suggests that the Tier II and III pop-