Brain-Eating Ameba

Developed by

Jewel B. Moses, PhD Arcot M. Saibaba, PhD

Southeast Middle School Newton High School

Hopkins, South Carolina Covington, Georgia

This lesson plan was developed by teachers attending the Science

Ambassador Workshop. The Science Ambassador Workshop is a career

workforce training for math and science teachers. The workshop is a Career

Paths to Public Health activity in the Division of

Scientific Education and

Professional Development, Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology,

and Laboratory Services, Office of Public Health Scientific Services,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC Science Ambassador Workshop

2013 Lesson Plan

Acknowledgements

This lesson plan was developed in consultation with subject matter experts from the Division of

Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic

Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Jennifer Cope, MD, MPH

Medical Epidemiologist

Jonathan Yoder, MSW, MPH

Epidemiologist

Scientific and editorial review was provided by Ralph Cordell, PhD and Kelly Cordeira, MPH from

Career Paths to Public Health, Division of Scientific Education and Professional Development, Center

for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, Office of Public Health Scientific Services,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Suggested citation

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Science Ambassador Workshop—Brain-eating

Ameba. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2013. Available at

http://www.cdc.gov/scienceambassador/lesson-plans/index.html.

Contact Information

Please send questions and comments to scienceambassador@cdc.gov.

Disclaimers

This lesson plan is in the public domain and may be used without restriction.

Citation as to source, however, is appreciated.

Links to nonfederal organizations are provided solely as a service to our users. These links do

not constitute an endorsement of these organizations nor their programs by the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the federal government, and none should be

inferred. CDC is not responsible for the content contained at these sites. URL addresses listed

were current as of the date of publication.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply

endorsement by the Division of Scientific Education and Professional Development, Center

for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC, the Public Health Service, or

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The findings and conclusions in this Science Ambassador Workshop lesson plan are those of

the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC).

Contents

Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 1

Learning Outcomes ................................................................................................................................. 2

Duration .................................................................................................................................................. 2

Procedures ............................................................................................................................................... 3

Day 1: Introduction to Parasites, 45 minutes ........................................................................................ 3

Preparation ......................................................................................................................................... 3

Materials ............................................................................................................................................. 3

Online Resources ............................................................................................................................... 3

Activity ............................................................................................................................................... 4

Day 2: Parasitic Environments, 45 minutes ......................................................................................... 5

Preparation ......................................................................................................................................... 5

Materials ............................................................................................................................................. 5

Online Resources ............................................................................................................................... 5

Activity ............................................................................................................................................... 6

Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 7

Assessments ............................................................................................................................................ 7

Educational Standards ............................................................................................................................. 8

List of Appendices ................................................................................................................................. 10

Appendix 1A: Waterborne Disease Case Study, Scenario Worksheet ................................................ 11

Appendix 1B: Waterborne Disease Case Study, Scenario Worksheet Answer Key .......................... 12

Appendix 2A: Waterborne Disease Case Study, Graphic Organizer .................................................. 13

Appendix 2B: Waterborne Disease Case Study, Graphic Organizer Answer Key .............................16

Appendix 3A: Waterborne Disease Case Study, Laboratory Exploration ......................................... 19

Appendix 3B: Waterborne Disease Case Study, Laboratory Exploration Answer Key .....................22

Appendix 4: Waterborne Disease Case Study, Public Awareness Campaign ..................................... 26

Appendix 5A: Brain-Eating Ameba Quiz .......................................................................................... 27

Appendix 5A: Brain-Eating Ameba Quiz, Answer Key .................................................................... 28

1

Brain-Eating Ameba

Summary

Swimming is a fun summer activity, but it can

increase your risk for contracting certain waterborne

diseases. Naegleria fowleri (N. fowleri) is among

many organisms that live in recreational waters, such

as ponds and lakes, and is commonly referred to as

the brain-eating ameba. It is a single-celled,

bacteria-eating organism that can be found in warm

fresh water around the world. It is a free-living

ameba that lives in the environment and does not

need a human host to complete its life cycle.

Fortunately, infections caused by N. fowleri are rare

and the risk for diseases is very low. During the

summer of 2013, only four cases were reported in

the United States and during the 10 years from 2005

to 2014, a total of 35 cases were reported, despite

millions of recreational water exposures each year.

By comparison, during the 10 years from 2001 to

2010, >34,000 drowning deaths occurred in the

United States. N. fowleri usually infects people when

contaminated water enters the body through the

nose. You cannot become infected from swallowing

water contaminated with N. fowleri.

This lesson plan demonstrates how microorganisms

normally found in environments, such as the bottom

of warm freshwater ponds and lakes can cause illness

when they enter the human body. Students engaged in

this lesson plan will learn about N. fowleri (the

scientific name of the brain-eating ameba), where it

lives, how it can cause infection, and how persons can

protect themselves from this infection. Students will

also have the opportunity to identify other organisms

living in local freshwater reservoirs, such as ponds

and lakes. At the end of the lesson, students should

have an enhanced understanding of the environment’s

role in disease transmission and ways to reduce the risk for contracting waterborne infections.

This material is suitable for use in high school biology or environmental science classes and can be

included as part of lessons on aquatic ecosystems. Before studying this lesson, students should have a

basic understanding of the following six kingdom classifications: Archaebacteria, Eubacteria, Protista,

Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia. Student prior knowledge of anatomy of the human nose and brain would

also be helpful.

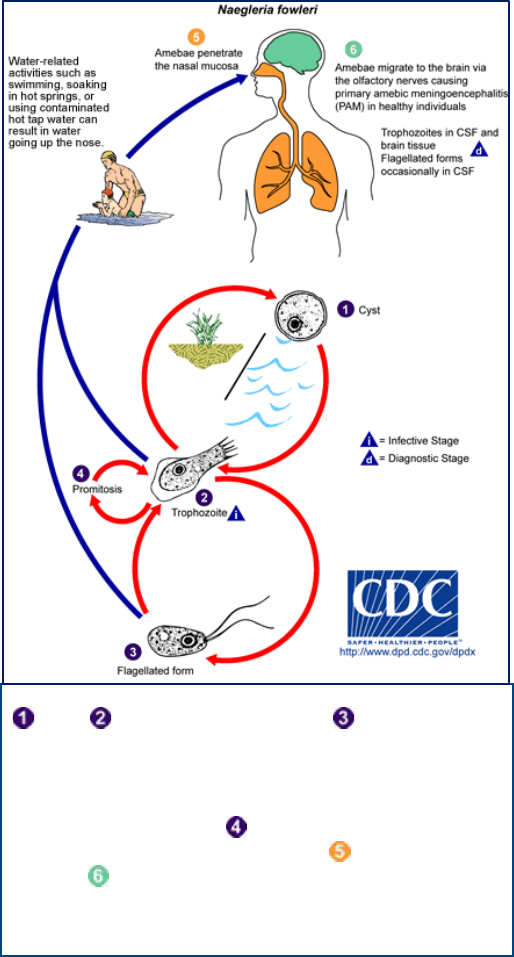

Figure 1. Naegleria fowleri has 3 stages in its life cycle:

cysts, ameboid trophozoites, and flagellates. The

only infective stage of the ameba is the ameboid trophozoite.

Trophozoites are 10–35 µm long with a granular appearance

and a single nucleus. The trophozoites replicate by binary

division during which the nuclear membrane remains intact (a

process called promitosis) Trophozoites infect humans or

animals by penetrating the nasal tissue and migrating to

the brain via the olfactory nerves causing primary amebic

meningoencephalitis (PAM).

Source:

http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/pathogen.html

2

Learning Outcomes

After completing this lesson, students should be able to

• explain how freshwater organisms, such as the brain-eating ameba (N. fowleri), are affected by

environmental variations (e.g., temperature, nutrient availability, geography, and life-cycle stages);

• describe limitations of epidemiologic and laboratory evidence; and

• use critical thinking to construct an evidence-based explanation as to why an N. fowleri infection

might occur.

Duration

This lesson can be conducted as one 90-minute lesson or divided into two 45-minute lessons.

3

Procedures

Day 1: Introduction to Parasites, 45 minutes

Preparation

Before Day 1,

• Review the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Internet site regarding N. fowleri. See

the Online Resources section that follows.

• Schedule computer laboratory or library time or reserve student laptop cart.

• For the Waterborne Disease Case Study, make one copy per student of Appendix 1A, Scenario

Worksheet; and Appendix 2A, Graphic Organizer.

• Collect water samples from a local untreated water source (preferably a lake or a pond) or prepared

slides of organisms that would be in lake or pond water, including protista (flagellates, amebae

heliozoans, and ciliates), bacteria, algae, rotifers, hydra, worms, and arthropods. Students will use

these water samples on Day 2 to prepare wet mounts or use prepared slides for microscopic analysis.

Note: Surface water often has a relatively low concentration of organisms; because you likely will

require a higher concentration to be able to see much with a light microscope, try to collect the

sample from a greater depth, preferably near the bottom. Alternatively, collect prepared slides of

organisms that would be in lake or pond water, including protista (flagellates, amebae, heliozoans,

and ciliates), bacteria, algae, rotifers, hydra, worms, and arthropods.

Materials

• Appendix 1A, Scenario Worksheet

Description: This case study engages student curiosity as they investigate the cause of infection in a

male aged 14 years.

• Appendix 2A, Graphic Organizer

Description: Students use this worksheet to organize their notes.

• Computers with Internet access.

Online Resources

• CDC Internet site http://www.cdc.gov

Description: To determine the correct pathogen responsible for the victim’s death in the case study,

students research the three ameba options (Dientamoeba fragilis, Acanthamoeba, and N. fowleri) by

entering the terms into CDC’s search function.

• CDC Internet site on N. fowleri: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/index.html

Description: Students will use this website to complete their graphic organizer.

• Matthews S, Ginzl D, Walsh D, et al. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis—Arizona, Florida, and

Texas, 2007. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2008;57:573–7.

URL: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5721a1.htm?s_cid=mm5721a1_eURL.

Description: The original case study of an Arizona male aged 14 years infected with N. fowleri.

4

Activity

1. Read the Appendix 1A scenario aloud. Challenge students to determine the ameba (Dientamoeba

fragilis, Acanthamoeba, or N. fowleri) responsible for the infection described in the case study by

using http://www.cdc.gov and other search functions. After students discover that N. fowleri is

responsible for the infection, pose the question, “What are some dangers of swimming in untreated

water?” Talking points for this discussion can include

a. N. fowleri infections can be serious, but they are rare; although there is no need to be scared

of swimming in local lakes and ponds to avoid N. fowleri, it is best to practice simple

prevention measures, such as keeping head above water or using nose clips.

b. More common dangers related to swimming in fresh water include

• infections, such as leptospirosis, swimmer’s itch (cercarial dermatitis), giardiasis,

cryptosporidiosis, cholera, shigellosis, and norovirus and infections of Escherichia

coli, including E. coli O157:H7;

• wound infections;

• diving hazards and other water-related injuries; and

• drowning.

c. The majority of infections and dangers related to swimming in fresh water can be prevented.

2. Assign Appendix 2A, Graphic Organizer. Direct students to research N. fowleri environment,

nutrients, portal of entry into the human host, and patient symptoms using the CDC Internet site on

N. fowleri at http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/index.html.

5

Day 2: Parasitic Environments, 45 minutes

Preparation

Before Day 2,

• Review Internet resources and microscope procedures and safety.

• Make copies of Appendix 3A, Laboratory Exploration; Appendix 4, Public Awareness Campaign;

and Appendix 5A, Brain-Eating Ameba Quiz.

• Schedule computer laboratory or library time or reserve student laptop cart.

• Retrieve water samples collected on Day 1 and prepare microscopes for the laboratory.

Materials

• Appendix 5A, Brain-Eating Ameba Quiz

Description: This test gauges student knowledge of the brain-eating ameba.

• Water samples from a local untreated water source (preferably a lake or a pond) or prepared slides of

organisms that would be in lake or pond water, including protista (flagellates, amebae, heliozoans,

and ciliates), bacteria, algae, rotifers, hydra, worms, and arthropods

Description: Students use these water samples to prepare wet mounts or will use prepared slides for

microscopic analysis.

• Compound microscopes

• Laboratory gloves

• Computers with Internet access

• Appendix 3A, Laboratory Exploration

Description: This worksheet is used for the laboratory activity.

• Appendix 4, Public Awareness Campaign

Description: This worksheet is used for the laboratory activity.

Online Resources

• Pond Life Identification Kit

URLs:

http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/index.html?http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/pond/index.html

and

http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/index.html?http://www.microscopy-

uk.org.uk/pond/protozoa.html.

Description: These Internet sites provide images and descriptions of key features of certain common

freshwater organisms, including protista.

• Recreational Water Illnesses and Prevention Tips

URL: http://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/swimming/rwi/illnesses/index.html.

Description: This Internet site contains information regarding recreational water illnesses and how to

avoid them.

6

Activity

1. Assign students Appendix 5A, Brain-Eating Ameba Quiz. Students should complete the short quiz

on their own and then review the answers as a class.

2. Review laboratory and microscope procedures, including microscope parts, magnification, and

focusing techniques; safe handling of the water samples; and wet-mount preparation.

3. Divide the class into pairs or groups of 3 for the microscope activity. Have each group analyze the

water sample assigned to them and identify organisms living in the sample. Have students draw each

organism on Appendix 3C, Laboratory Exploration. Using the Pond Life Identification Kit, have

students determine the scientific name of each organism.

4. Ask students to state the most common organism group found in their sample and to estimate the

number of amebae found in their sample. As a class, discuss potential reasons why the number of

amebae differs from group to group. Use this example to discuss why no method exists that

accurately and reproducibly measures the number of amebae in the water.

5. Prompt students to answer questions 3–5 in their group. Discuss the answers.

6. For homework, instruct students to design a public health awareness campaign using a most-wanted-

type poster or a brochure that illustrates how to reduce the risk for acquiring their assigned

waterborne disease. See Appendix 4.

7

Conclusion

Students use a public health scenario to learn about limnology, microbiology, and public health. By

examining the life cycle of N. fowleri, students examine how environmental variation in the lake, such

as temperature, nutrient availability, and geography, can affect the life cycle of an organism. Then,

students learn how life-cycle changes can increase the risk for human infection leading to the disease

called primary amebic meningoencephalitis. However, since no data exist to accurately estimate the true

risk, students use critical thinking to formulate hypotheses that account for limitations in epidemiology

and the laboratory.

Assessments

• Appendix 1A, Scenario Worksheet

Learning Outcomes Assessed:

- Explain how freshwater organisms, such as the brain-eating ameba (N. fowleri), are affected by

environmental variations (e.g., temperature, nutrient availability, geography, life-cycle stages).

- Describe limitations of epidemiological and laboratory evidence.

- Use critical thinking to construct an evidence-based explanation as to why a case of brain-eating

infection may occur.

Description: This case study engages student curiosity as they investigate the cause of infection in a

male aged 14 years.

• Appendix 5, Brain-Eating Ameba Quiz

Learning Outcome Assessed:

- Explain how freshwater organisms, such as the brain-eating ameba (N. fowleri), are affected by

environmental variations (e.g., temperature, nutrient availability, geography, and life-cycle

stages).

Description: This quiz of five multiple-choice questions gauges student knowledge of the brain-

eating ameba and should take approximately 10 minutes to complete.

8

Educational Standards

In this lesson, the following CDC Epidemiology and Public Health Science (EPHS) Core Competencies

for High School Students

1

, Next Generation Science Standards

*

(NGSS) Science & Engineering

Practices

2

, and NGSS Cross-cutting Concepts

3

are addressed:

HS-EPHS1-2. Discuss how epidemiologic thinking and a public health approach is used to transform a

narrative into an evidence-based explanation.

NGSS Key Science & Engineering Practice

2

Obtaining, Evaluating and Communicating Information

Critically read scientific literature adapted for classroom use to determine the central ideas or

conclusions and/or to obtain scientific and/or technical information to summarize complex

evidence, concepts, processes, or information presented in a text by paraphrasing them in

simpler but still accurate terms.

NGSS Key Crosscutting Concept

3

Cause and Effect

Empirical evidence is required to differentiate between cause and correlation and make

claims about specific causes and effects.

HS-EPHS2-4. Use patterns in empirical evidence to formulate hypotheses.

NGSS Key Science & Engineering Practice

2

Asking Questions & Defining Problems

Ask questions that arise from careful observation of phenomena, or unexpected results, to

clarify and/or seek additional information, that arise from examining models or a theory, to

clarify and/or seek additional information and relationships, to determine relationships,

including quantitative relationships, between independent and dependent variables, and to

clarify and refine a model, an explanation, or an engineering problem.

NGSS Key Crosscutting Concept

3

Patterns

Empirical evidence is needed to identify patterns.

HS-EPHS3-5. Make a claim about causality with consideration of a mathematical analysis of empirical

data and Bradford Hill’s Criteria for Causality.

NGSS Key Science & Engineering Practice

2

Engaging in Argument from Evidence

Make and defend a claim based on evidence about the natural world or the effectiveness of a

design solution that reflects scientific knowledge and student-generated evidence.

NGSS Key Crosscutting Concept

3

Systems and System Models

Models can be used to predict the behavior of a system, but these predictions have limited

precision and reliability due to the assumptions and approximations inherent in models.

*

Next Generation Science Standards is a registered trademark of Achieve. Neither Achieve nor the lead states and partners

that developed the Next Generation Science Standards was involved in the production of, and does not endorse, this product.

9

1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Science Ambassador Workshop—Epidemiology and Public Health

Science: Core Competencies for high school students. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC;

2015. Not currently available for public use.

2

NGSS Lead States. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States (Appendix F–Science and Engineering

Practices). Achieve, Inc. on behalf of the twenty-six states and partners that collaborated on the NGSS. 2013. Available at:

http://www.nextgenscience.org/sites/ngss/files/Appendix%20F%20%20Science

%20and%20Engineering%20Practices%20in%20the%20NGSS%20-%20FINAL%20060513.pdf

3

NGSS Lead States. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States (Appendix G–Crosscutting Concepts).

Achieve, Inc. on behalf of the twenty-six states and partners that collaborated on the NGSS. 2013. Available at:

http://www.nextgenscience.org/sites/ngss/files/Appendix%20G%20-

%20Crosscutting%20Concepts%20FINAL%20edited%204.10.13.pdf.

.

10

Appendices: Supplementary Documents

11

Appendix 1A

Waterborne Disease Case Study

Scenario Worksheet

Name: __________________________________ Date: ________________

Directions: Read the following case study on a waterborne disease. Next, use the CDC Internet site

(http://www.cdc.gov) to determine if the ameba responsible for the victim’s death might have been

Dientamoeba fragilis, Acanthamoeba, or Naegleria fowleri.

In Arizona, an adolescent male aged 14 years was enjoying the last of his summer days swimming in a

northeastern Arizona lake. He was observed diving and splashing in shallow water. The water

temperature on that day, September 8, was 86.3°F (30.2°C), and the air temperature was 108.0°F

(42.2°C). Approximately 1 week later, on September 14, he experienced a severe headache, stiff neck,

and fever. On September 16, he was hospitalized with possible meningitis (inflammation of the

meninges of the brain). From a spinal tap, doctors observed an ameba in his cerebrospinal fluid by using

a microscope. Note: The meninges are three layers of tissue that surround the brain and spinal cord to

protect the central nervous system.

1. What is the name of the ameba responsible for the victim’s death?

2. How might have infection occurred?

3. List at least three factors that led you to your answer in Question 1.

12

Appendix 1B

Waterborne Disease Case Study

Scenario Worksheet Answer Key

Name: ___________________________________ Date: ________________

Directions: Read the following case study on a waterborne disease. Next, use the CDC Internet site

(http://www.cdc.gov) to determine if the ameba responsible for the victim’s death might have been

Dientamoeba fragilis, Acanthamoeba, or Naegleria fowleri.

In Arizona, an adolescent male aged 14 years was enjoying the last of his summer days swimming in a

northeastern Arizona lake. He was observed diving and splashing in shallow water. The water

temperature on that day, September 8, was 86.3°F (30.2°C), and the air temperature was 108.0°F

(42.2°C). Approximately 1 week later, on September 14, he experienced a severe headache, stiff neck,

and fever. On September 16, he was hospitalized with possible meningitis (inflammation of the

meninges of the brain). From a spinal tap, doctors observed an ameba in his cerebrospinal fluid by using

a microscope. Note: The meninges are three layers of tissue that surround the brain and spinal cord to

protect the central nervous system.

1. What is the name of the ameba responsible for the victim’s death?

Answer: Naegleria fowleri. Note: Students should be able to deduce which ameba was responsible

by the characteristics given in the scenario and the information provided on the CDC Internet site:

http://www.cdc.gov/. For more details, see question 3.

2. How might have infection occurred?

Answer: Infection might have occurred as a result of swimming in the northeastern Arizona lake.

Students can also consider some of the other possible sources before coming to this conclusion,

including bodies of warm freshwater, such as lakes and rivers; geothermal (naturally hot) water, such

as hot springs; warm water discharge from industrial plants; geothermal (naturally hot) drinking

water sources; swimming pools that are poorly maintained, minimally chlorinated or unchlorinated;

water heaters; and soil.

3. List at least three factors that led you to your answer in Question 1.

Answer: Explanations might include the following: infection might have occurred as a result of

swimming in a lake in a U.S. state with a high number of case reports (5–9 cases); the optimal water

temperature range for the growth of the brain-eating ameba is 45°C–55ºC; average time of symptom

onset is typically 5 days (range, 1–7 days); average time from symptom onset to death is 5.3 days

(range, 1–12 days); early signs and symptoms include fever and headache; later signs and symptoms

include neck stiffness and seizures; amebae in the trophozoite morphology were observed in the

spinal fluid.

13

Appendix 2A

Waterborne Disease Case Study

Graphic Organizer

Name: __________________________________ Date: ________________

Directions: Complete the case study graphic organizer.

After Naegleria fowleri (N. fowleri) was found in trophozoite form in the spinal fluid, the boy was

diagnosed with primary amebic meningoencephalitis. To become more familiar with this waterborne

disease, use this worksheet to organize your notes into five sections: (1) scientific name and life-cycle

overview, (2) the cause-and-effect association between the environment and parasites, (3) diagnostics

and treatment strategies, (4) surveillance and epidemiology, and (5) risk communication challenges. Use

N. fowleri as an example in each section. Use the CDC Internet site on N. fowleri at

http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/index.html to find information; take notes with a partner.

Scientific name and life-cycle overview

What is the common name for N. fowleri?

Describe or illustrate the life cycle of the brain-eating ameba.

14

Cause-and-effect association between the environment and parasites

How can the environment affect a parasite’s life cycle?

State examples of environmental factors that can affect a parasite’s life cycle:

What is the optimal temperature for growth of the brain-eating ameba?

How does the brain-eating ameba cause disease?

What is primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM)?

15

Diagnostics and treatment strategies

What are some diagnostic strategies for brain-eating amebic infection and PAM?

What are the treatment options for brain-eating ameba infection/PAM?

Surveillance and epidemiology

How many cases of PAM were reported during 1962–2014?

Who is most likely to be infected with this brain-eating ameba?

When is the most common time of the year to become infected with this brain-eating ameba?

Where is exposure to the brain-eating ameba most likely to occur?

Environmental prevention challenges

What are certain environmental concerns regarding N. fowleri infection?

16

Appendix 2B

Waterborne Disease Case Study

Graphic Organizer Answer Key

Name: __________________________________ Date: ________________

Directions: Complete the case study graphic organizer.

After Naegleria fowleri (N. fowleri) was found in trophozoite form in the spinal fluid, the boy was

diagnosed with primary amebic meningoencephalitis. To become more familiar with this waterborne

disease, use this worksheet to organize your notes into five sections: (1) scientific name and life-cycle

overview, (2) the cause-and-effect association between the environment and parasites, (3) diagnostics

and treatment strategies, (4) surveillance and epidemiology, and (5) risk communication challenges. Use

N. fowleri as an example in each section. Use the CDC Internet site on N. fowleri at

http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/index.html to find information; take notes with a partner.

Scientific name and life-cycle overview

What is the common name for N. fowleri?

Answer: Brain-eating ameba

Describe or illustrate the life cycle of the brain-eating ameba.

Answer: N. fowleri has three stages in its life cycle: ameboid trophozoites, flagellates, and cysts. The

only infective stage of the ameba is the ameboid trophozoite. Trophozoites are 10–35 µm long, with a

granular appearance and a single nucleus. The trophozoites replicate by binary division during which

the nuclear membrane remains intact (a process called promitosis). Trophozoites infect humans or

animals by penetrating the nasal tissue and migrating to the brain through the olfactory nerves,

causing primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM).

Source: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/pathogen.html

17

Cause-and-effect association between the environment and parasites

How can the environment affect a parasite’s life cycle?

Answer: Trophozoites can turn into a temporary, nonfeeding, flagellated stage (10–16 µm long) when

stimulated by adverse environmental changes, such as a reduced food source. If the environment is

not conducive to continued feeding and growth (e.g., cold temperatures and scarce food), the ameba

or flagellate forms a cyst. The cyst form is spherical and 7–15 µm in diameter. It has a smooth, single-

layered wall with a single nucleus. Cysts remain resistant to environmental stresses to increase their

chance of survival until better conditions occur.

Source: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/pathogen.html

State examples of environmental factors that can affect a parasite’s life cycle:

Answer: Examples include cold temperatures or food scarcity.

What is the optimal temperature for growth of the brain-eating ameba?

Answer: N. fowleri grows best at higher temperatures up to 115°F (46°C). Although the ameba might

not be able to grow well, N. fowleri can still survive at even higher temperatures for limited periods.

The trophozoites and cysts can survive from minutes to hours at 122°F–149°F (50°C–65°C), with the

cysts being more resistant to these higher temperatures. Although trophozoites are killed rapidly by

refrigeration, cysts can survive for weeks to months at cold temperatures, but they appear to be

sensitive to freezing temperatures. Consequently, colder temperatures are likely to cause N. fowleri to

encyst in lake and river sediment, which offers more protection from cold and freezing water

temperatures.

Source: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/pathogen.html

How does the brain-eating ameba cause disease?

Answer: The ameba infects humans when contaminated water enters the body through the nose. It

then travels up the olfactory nerve to the brain, where it causes PAM. Contaminated water can come

from different types of untreated water sources.

What is primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM)?

Answer: Answers will vary. PAM is an acute disease that rapidly leads to death in approximately all

cases. Only 3 of 133 U.S. patients have survived the infection. On average, humans die <10 days after

exposure to the ameba. The disease presents much like bacterial meningitis, which can lead to delayed

diagnosis and treatment. In approximately 25% of cases, the trophozoites were observed in the

cerebrospinal fluid while the patient was still alive, but more often, the diagnosis is not made until

after the patient dies and an autopsy is performed. In those cases, the ameba is usually observable in

tissue sections of the brain.

18

Diagnostics and treatment strategies

What are some diagnostic strategies for brain-eating amebic infection and PAM?

Answer: Answers will vary. Diagnostic strategies include (1) direct visualization (motile trophozoites

observed in the cerebrospinal fluid), (2) immunohistochemistry (antibody staining of the amebae in

tissue), (3) polymerase chain reaction testing (detecting ameba DNA), and (4) culture (amebae grown

by using bacteria as a food source and incubating at high temperature).

What are the treatment options for brain-eating ameba infection/PAM?

Answer: Treatment includes a combination of antibiotics and an investigational drug (miltefosine).

The documented survival rate when using the combination or cocktail of antibiotics is 2% (3 of 133

cases). Miltefosine has been used in other ameba infections and appears to improve survival rates.

Surveillance and epidemiology

How many cases of PAM were reported during 1962–2014?

Answer: The number of cases of PAM reported during 1962–2014 was 133, with a range of 0–8

infections/year.

Who is most likely to be infected with this brain-eating ameba?

Answer: Male children. The median age of patients reported is 11 years, and 77% were male.

When is the most common time of the year to become infected with this brain-eating ameba?

Answer: The most common months of illness onset are July and August, with a range of April–

November.

Where is exposure to the brain-eating ameba most likely to occur?

Answer: The most probable water exposure sources are lakes, ponds, and reservoirs (untreated fresh

water). Texas and Florida have the highest number of reported cases in the United States.

Environmental prevention challenges

What are certain environmental concerns regarding N. fowleri infection?

Answer: A major concern is that as water temperatures increase worldwide, the geographic range of

brain-eating ameba is anticipated to shift northward. Another concern is moderate chlorine resistance,

which affects water treatment as a prevention measure.

19

Appendix 3A

Waterborne Disease Case Study

Laboratory Exploration

Name: __________________________________ Date: ________________

Directions: In groups of 3–4, complete the case study laboratory exploration.

Assume that the samples provided are from the northeastern Arizona lake where the boy with brain-

eating ameba was swimming. Pretend you are a team of microbiologists. Each team will receive a

sample to observe. With your team, create wet-mount slides of your water sample. Use the microscopes

to explore organisms in your sample. In the spaces below, draw the organisms you see. Be sure to

include the magnification level. Next, to identify the scientific name of the organism, use the Pond Life

Identification Kit at http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/index.html?http://www.microscopy-

uk.org.uk/pond/index.html and http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/index.html?http://www.microscopy-

uk.org.uk/pond/protozoa.html.

Table 1: Organisms in your sample

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

20

Picture:

Organism: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

21

Questions

1. What was the most common organism found?

2. Approximately, how many amebae were in your sample?

3. If N. fowleri was not found in the lake samples in the case of the Arizona male, it might still have

been possible for infection to be caused by N. fowleri.

a. Explain why the male was diagnosed with primary amebic meningoencephalitis likely caused by

N. fowleri.

b. Why was swimming in the lake the likely cause of N. fowleri infection?

4. If N. fowleri were present in the lake samples in the case of the Arizona boy, explain why more

people were not infected. Hint: consider the organism’s life cycle and influencing environmental

factors (e.g., climate, water pH, nutrient availability, and spatiality).

5. Explain why CDC does not recommend testing rivers and lakes for N. fowleri.

6. N. fowleri infections are rare. During 2005–2014, a total of 35 infections were reported in the United

States. Of those cases, 31 persons were infected by contaminated recreational water. What are some

more likely dangers related to swimming in recreational water, such as a lake?

22

Appendix 3B

Waterborne Disease Case Study

Laboratory Exploration Answer Key

Name: __________________________________ Date: ________________

Directions: In groups of 3–4, complete the case study laboratory exploration.

Assume that the samples provided are from the northeastern Arizona lake where the boy with brain-

eating ameba was swimming. Pretend you are a team of microbiologists. Each team will receive a

sample to observe. With your team, create wet-mount slides of your water sample. Use the microscopes

to explore organisms in your sample. In the spaces below, draw the organisms you see. Be sure to

include the magnification level. Next, to identify the scientific name of the organism, use the Pond Life

Identification Kit at http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/index.html?http://www.microscopy-

uk.org.uk/pond/index.html and http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/index.html?http://www.microscopy-

uk.org.uk/pond/protozoa.html.

Table 1: Organisms in your sample

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

23

Picture:

Organism: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

Picture:

Organism Group: _________________________

Magnification: _________________________

24

Questions

1. What was the most common organism found?

Answer: Answers will vary.

2. Approximately, how many amebae were in your sample?

Answer: Answers will vary.

3. If N. fowleri was not found in the lake samples in the case of the Arizona male, it might still have

been possible for infection to be caused by N. fowleri.

a. Explain why the male was diagnosed with primary amebic meningoencephalitis likely caused by

N. fowleri.

Answer: The laboratory test results from the spinal fluid confirmed that the male was infected with

N. fowleri. He presented with early symptoms of primary amebic meningoencephalitis, such as

fever and headache, within the average time of symptom onset. He later presented with neck

stiffness.

b. Why was swimming in the lake the likely cause of N. fowleri infection?

Answer: Answers can include: Swimming in warm freshwater lakes is the most common type of

exposure that leads to the brain-eating ameba infection. However, the water temperature on that

day, September 8, 2007, was 86.3°F (30.2°C), which was not within the optimal water temperature

range for the growth of N. fowleri (45ºC–55ºC).

Note: Consider discussing what epidemiologists might do at this stage. For example,

epidemiologists would systematically identify other cases in the area and look at the distribution

(e.g., person, place, and time) and possible determinants of infection (i.e., other sources of

infection, including bodies of warm freshwater, such as lakes and rivers; geothermal water,

including hot springs; warm water discharge from industrial plants; geothermal drinking water

sources; swimming pools that are poorly maintained, minimally chlorinated or unchlorinated; water

heaters; and soil) across cases.

4. If N. fowleri were present in the lake samples in the case of the Arizona boy, explain why more

people were not infected. Hint: consider the organism’s life cycle and influencing environmental

factors (e.g., climate, water pH, nutrient availability, and spatiality).

Answer: Multiple factors are needed that must come together at the same time to result in infection.

N. fowleri infects person when water containing the ameba enters the body through the nose, and N.

fowleri must be in an infective life-cycle stage. Life-cycle stages are influenced by environmental

factors that affect an organism’s ability to feed, grow, and survive. Humans will not be infected if

the water ingested does not contain the ameba, if life cycle conditions are not ideal for infection, or if

the water is ingested other than through the nose.

5. Explain why CDC does not recommend testing rivers and lakes for N. fowleri.

Answer: The ameba is naturally occurring and no established relationship between detection or

concentration of N. fowleri and risk for infection is known.

25

6. N. fowleri infections are rare. During 2005–2014, a total of 35 infections were reported in the United

States. Of those cases, 31 persons were infected by contaminated recreational water. What are some

more likely dangers related to swimming in recreational water, such as a lake?

Answer: Drowning; infection (e.g., leptospirosis, swimmers itch [cercarial dermatitis], giardiasis,

cryptosporidiosis, cholera, shigellosis, norovirus, and Escherichia coli infections, including E. coli

O157:H7 infections); wound infections (e.g., the flesh-eating bacteria Aeromonas); diving hazards

and other water-related injuries. (Answers will vary.)

26

Appendix 4

Waterborne Disease Case Study

Public Awareness Campaign

Name: __________________________________ Date: ________________

Directions: Create a public awareness campaign through a most-wanted–type poster or a brochure that

illustrates how to reduce the risk for acquiring a particular waterborne disease.

1. Choose and circle a recreational water illness from the following

• “Crypto” (Cryptosporidium)

• Giardia

• Hot tub rash

• Legionella

• Swimmer's ear (otitis externa)

• Head lice

• Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

• Pinworm

2. Complete the graphic organizer below by using the CDC Internet site concerning Recreational Water

Illnesses and Prevention Tips: http://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/swimming/rwi/illnesses/index.html.

What is it?

Why should you be

concerned about it?

How is it spread in

aquatic facilities?

How do you protect

yourself and your

family?

3. Use your graphic organizer to create a public awareness campaign through a most-wanted–type

poster or a brochure that illustrates how to reduce the risk for acquiring a particular waterborne

disease.

27

Appendix 5A

Brain-Eating Ameba Quiz

Name: __________________________________ Date: ________________

Directions: Circle the best answer for each question.

1. The scientific name of the brain-eating ameba is . . .

a. Haemophilus influenzae.

b. Escherichia coli.

c. Naegleria fowleri.

d. Salmonella typhi.

2. From the case study, this pathogen is detected in . . .

a. skin.

b. hair.

c. bones.

d. cerebrospinal fluid.

3. Which of the following is NOT a morphologic stage of this pathogen’s life cycle?

a. Cyst

b. Polyp (Answer)

c. Trophozoite

d. Flagellate

4. The optimal temperature range for the growth of this pathogen is . . .

a. 45ºC –55ºC.

b. 10ºC –20ºC.

c. 25ºC –45ºC.

d. 75ºC –90ºC.

5. Which of the following can reduce your risk for becoming infected with PAM?

a. Avoid swimming in lakes and ponds during periods of high water temperature.

b. Hold your nose shut, use nose clips, or keep your head above water when taking part in water-

related activities in bodies of warm fresh water.

c. Avoid disrupting the sediment (digging or stirring) while taking part in water-related activities in

shallow, warm freshwater areas.

d. All of the above.

28

Appendix 5B

Brain-Eating Ameba Quiz Answer Key

Name: __________________________________ Date: ________________

Directions: Circle the best answer for each question.

1. The scientific name of the brain-eating ameba is . . .

e. Haemophilus influenzae.

f. Escherichia coli.

g. Naegleria fowleri. (Answer)

h. Salmonella typhi.

2. From the case study, this pathogen is detected in . . .

e. skin.

f. hair.

g. bones.

h. cerebrospinal fluid. (Answer)

3. Which of the following is NOT a morphologic stage of this pathogen’s life cycle?

e. Cyst

f. Polyp (Answer)

g. Trophozoite

h. Flagellate

4. The optimal temperature range for the growth of this pathogen is . . .

e. 45ºC –55ºC. (Answer)

f. 10ºC –20ºC.

g. 25ºC –45ºC.

h. 75ºC –90ºC.

5. Which of the following can reduce your risk for becoming infected with PAM?

e. Avoid swimming in lakes and ponds during periods of high water temperature.

f. Hold your nose shut, use nose clips, or keep your head above water when taking part in water-

related activities in bodies of warm fresh water.

g. Avoid disrupting the sediment (digging or stirring) while taking part in water-related activities in

shallow, warm freshwater areas.

h. All of the above. (Answer)