Decolonial AI Alignment: Openness, Viśes

.

a-Dharma, and Including Excluded

Knowledges

KUSH R. VARSHNEY, IBM Research – Thomas J. Watson Research Center, USA

Prior work has explicated the coloniality of articial intelligence (AI) development and deployment through mechanisms such as

extractivism, automation, sociological essentialism, surveillance, and containment. However, that work has not engaged much with

alignment: teaching behaviors to a large language model (LLM) in line with desired values, and has not considered a mechanism

that arises within that process: moral absolutism—a part of the coloniality of knowledge. Colonialism has a history of altering the

beliefs and values of colonized peoples; in this paper, I argue that this history is recapitulated in current LLM alignment practices

and technologies. Furthermore, I suggest that AI alignment be decolonialized using three forms of openness: openness of models,

openness to society, and openness to excluded knowledges. This suggested approach to decolonial AI alignment uses ideas from the

argumentative moral philosophical tradition of Hinduism, which has been described as an open-source religion. One concept used is

viśe

s

.

a-dharma, or particular context-specic notions of right and wrong. At the end of the paper, I provide a suggested reference

architecture to work toward the proposed framework.

CCS Concepts: • Computing methodologies → Articial intelligence.

Additional Key Words and Phrases: Alignment, Coloniality, Moral Absolutism, Dharma

ACM Reference Format:

Kush R. Varshney. 2024. Decolonial AI Alignment: Openness, Viśe

s

.

a-Dharma, and Including Excluded Knowledges. 1, 1 (May 2024),

21 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/nnnnnnn.nnnnnnn

1 INTRODUCTION

For more than a year now, the public has experienced powerful large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4, Claude 2,

Gemini, Llama 3, and Mixtral. Beyond the initial amazement and excitement, we have witnessed the bearing out of

environmental and sociotechnical harms foreseen by Ref. [

12

] and others. The need to control the cost and behavior of

LLMs has become apparent. While such governance is relevant in chat interfaces made available by model providers, it

comes to the forefront when LLMs are infused into software applications and use cases by organizations with varied

aected communities, missions, goals, regulations, and values.

The way in which an LLM may be infused into an application, and the degree to which it may be customized [

74

],

depends on what the model provider allows. Despite the term ‘open’ being used and abused in dierent ways by model

providers [

149

], these are questions of openness. A provider may only allow application programming interface (API)

access to a closed proprietary model. A provider may license model weights and parameters to users so that they

may download the LLM locally and ne-tune it on their own data. A provider may oer full transparency into the

pre-training datasets, data pre-processing operations, and architecture that would allow others to recreate their model.

Although subject to ‘open-washing,’ we are seeing an emerging divergence between advocates of ‘open’ vs. ‘closed’

LLMs in the market, epitomized by the AI Alliance vs. the Frontier Model Forum [117].

Author’s address: Kush R. Varshney, [email protected], IBM Research – Thomas J. Watson Research Center, 1101 Kitchawan Road, Yorktown Heights,

New York, USA, 10598.

© 2024 Association for Computing Machinery.

Manuscript submitted to ACM

Manuscript submitted to ACM 1

arXiv:2309.05030v3 [cs.CY] 2 May 2024

2 Kush R. Varshney

The more open LLMs are, the more they permit application developers to make them authentic to their needs and the

values of their communities. For example, Jacaranda Health has created UlizaLlama

1

for its community in East Africa by

continuing to train Llama 2 with 322M tokens of Kiswahili and further instruction ne-tuning it to respond to questions

in healthcare, agriculture, and other locally-relevant topics. UlizaLlama is a step in Jacaranda’s development of its

LLM-infused maternal health digital platform PROMPTS. In constrast, application developers and their communities

are not empowered to reect their own values with closed LLMs. They must live with the commandments of good and

bad, and right and wrong that the provider of a closed model happens to have inserted.

The further actions to change an LLM’s behavior, beyond the standard pre-training of a base LLM, have come to be

known as alignment. The term is an empty signier without a xed concept that is signied; dierent parties have

appropriated the term to refer to various actions for getting an LLM to behave according to some human values [

73

].

Desired behaviors (with varying levels of specicity) could range from following instructions, to carrying on helpful

conversations, to yielding safe or moral outputs (with dierent denitions), to something else altogether. The behavior

of an LLM may be controlled through data curation, full or parameter-ecient supervised ne-tuning, reinforcement

learning with direct or indirect human feedback, self-alignment, prompt engineering (few-shot learning), and guardrails

or moderations [

68

,

72

,

147

]. I defer discussion of the details, and of the computation, data and human resources required

for each of these approaches to Section 2.1. Existing approaches do not allow for dierent aligned behaviors of a given

LLM based on the context of deployment.

A further question with LLM-infused applications has to do with the business notion of ‘value,’ as in earnings, prots,

or other measures of commercial utility, rather than human values of right and wrong. Does value accrue to the model

provider or to the application developer [

20

]? Openness may enable ecosystems in which application developers and

their communities accrue value (cf. Jacaranda Health), whereas closed LLM providers may exercise their power to be

extractive in nature. Extractivism is a part of coloniality [125], which is the main topic of this paper.

Colonialism is one country controlling another and exploiting it economically and in other ways. Coloniality, however,

describes domination, including in abstract forms such as in the production of knowledge, that remains after the end of

formal colonialism [

119

]. Decoloniality is the process of challenging and dismantling coloniality [

96

]. The terms usually

refer to European or Western colonialism and its remnants in the Global South. Decolonial computing is developing

computing systems with and for people there that reduce asymmetric power relationships, based on their values and

their knowledge systems [

7

]. Based on these ideas, there has been a recent owering of research on decolonial articial

intelligence (AI), beginning with the seminal paper by Mohamed, Png and Isaac [

99

]. Through this lens, extractive

providers of closed models may be viewed as metropoles: the colonial powers. Further discussion of the decolonial AI

literature is provided in Section 2.2.

The scope of the coloniality considered in AI thus far has included extractivism as well as four other mechanisms:

automation, sociological essentialism, surveillance, and containment [

140

]. The contribution of this paper is to examine

a dierent colonial mechanism from these ve, namely ethical essentialism also known as moral absolutism, which arises

specically in the alignment of LLMs. If a powerful model provider views their (Western) ethics or moral philosophy as

universally correct, leaves no possibility for moral variety [

47

], and marginalizes all other ways of thinking about right

and wrong, then their approach to AI alignment is colonial. They are behaving as a metropole.

In Section 3, I expand upon this viewpoint of coloniality occurring in AI alignment through the mechanism of moral

absolutism and the centering of Western philosophy. This includes not only a philosophical discussion, but also a critical

1

https://huggingface.co/Jacaranda/UlizaLlama

Manuscript submitted to ACM

Decolonial AI Alignment: Openness, Viśes

.

a-Dharma, and Including Excluded Knowledges 3

examination of the technology for AI alignment. In Section 4, I broach the decolonialization of AI alignment, which

can be seen as a kind of decolonialization of knowledge, through the lens of open science and innovation [

26

]. Such

openness includes three thrusts: (1) openness to research artifacts (which includes LLMs in our context), (2) openness

to society, and (3) openness to excluded knowledges [

26

]. Based on these three openness pursuits, I lay out three

desiderata for doing AI alignment in a decolonial manner. Furthermore, I suggest an approach to alignment that meets

the desiderata. This suggested approach builds upon the non-universal non-absolutist tradition of moral philosophy

known as Hinduism [

33

,

122

], which includes vibrant argument and debate on the nature of dharma (right behavior)

and its explication through various ways of knowing, including artistic expression [

36

]. The syncretic framework of

Hinduism (described in greater detail in Section 2.3) has the appropriate characteristics of openness to be used as a

starting point for an alternative future of AI alignment [

127

,

134

]. At the end, I build upon the suggested dharmic

approach and give a more concrete reference architecture of a technology stack for less morally absolute and less

colonialized AI alignment.

2 PRELIMINARIES

2.1 Large Language Model Development Lifecycle and Alignment

The currently prevalent development lifecycle for applications infused with LLMs may be divided into two halves: steps

carried out by model providers and steps carried out by application developers. In an imperfect analogy with teaching a

child, the model provider does the basic steps of teaching the LLM to go from babbling words, to having uency in

language, to following instructions, to carrying on a conversation. The application developer, if so empowered, teaches

the LLM culture, which may include steps on subject matter expertise, social norms, laws, customs, and beliefs. Getting

to the point of language uency may be termed pre-training the base model or foundation model. Any of the steps after

language uency may be called ‘alignment,’ depending on the interlocutor. As mentioned earlier, the term ‘alignment’

is an empty signier, so it is not xed to refer to any specic step [73].

In pre-training, some amount of enculturation is possible by curating the content of the training dataset to include an

abundance of topics that the model provider wishes the LLM to be skilled in and ltering out taboo topics. As discussed

further in Section 2.2.3, some amount of undesirable cultural knowledge leaks into the pre-training performed by the

model provider. Filtering is computationally-intensive given the size of datasets being in the trillions of tokens. Data

curation is followed by self-supervised learning (like a peekaboo game) to obtain the base model, which may take

months despite using thousands of high-end graphical processing units.

The AI technologies to do any of the alignment steps on top of the base model are essentially the same, whether

the goal is following instructions, behaving according to social norms, or something else. Several techniques exist

with varying resource requirements for humans, data, and computation. Supervised ne-tuning (SFT) updates all of

the model weights according to a smaller, but still large dataset containing data with both inputs and outputs. It is

fairly computationally-intensive given that all weights are updated. If a model has already been trained to follow

instructions, then a dataset with instructions, inputs, and outputs may be used. To reduce data and computational

complexity, parameter-ecient ne-tuning methods do not update all model weights, but are more frugal. One specic

approach, low-rank adaptation (LoRA), trains a matrix of weights of the same dimensions as the LLM weights. This

LoRA matrix is added to the LLM weights at the time of inference. However, the LoRA matrix has orders of magnitude

fewer degrees of freedom through its construction as a low-rank matrix and is thus more ecient [63].

Manuscript submitted to ACM

4 Kush R. Varshney

Several alignment techniques include full SFT as a module, including reinforcement learning from human feedback

(RLHF) [

111

], reinforcement learning from AI feedback (RLAIF) [

9

], and self-align [

137

]. After SFT, these methods

further align the LLM by feeding back judgements of which outputs are preferred by, respectively, either: humans,

a preference model trained according to a set of explicit regulations (a constitution), or an LLM prompted through

instructions to respect a set of explicit regulations. RLHF requires a large amount of human labor and all three are

computationally involved. The LLM prompted to respect a set of explicit regulations in the self-align approach is also,

by itself, a simple but not always reliable way to align a model. By manually designing system prompts or prompt

templates to accompany all inputs, the LLM’s behavior may be controlled. Such prompt engineering adds to inference

costs because the input to the model includes extra tokens every time.

Finally, another way to align the behavior of an LLM is by a post-processing module that examines the output and

determines whether it satises pre-determined guardrails for specic unwanted behaviors. These post-processors or

moderations may be small classiers or other LLMs acting as ‘judges’ [2, 152].

2.2 Coloniality and Decoloniality

As introduced in Section 1, coloniality is an extension of colonialism after its formal end. It is the values, ways of

knowing, and power structures instituted during colonialism that remain, and may even be expanded to places without a

history of colonialism, that rationalize and perpetuate Western dominance. Decolonial perspectives disobey the program

of coloniality [

97

]. The theory of coloniality includes coloniality of power, coloniality of knowledge, and coloniality of

being. Coloniality of power describes social discrimination through hierarchies and caste systems instituted during

colonialism [

119

]. Coloniality of knowledge is the suppression of colonized peoples’ culture and ways of knowing; it is

used by colonizers in service of coloniality of power [

119

]. Coloniality of being is a severe version of coloniality of

knowledge: a people’s knowledge system is so inferior that those people do not even deserve to be, or to be human [

86

].

Coloniality is a subset of Empire [

59

], which also includes other dimensions of hegemony such as heteropatriarchy and

white supremacy [

140

]. Coloniality and decoloniality inuence several areas of study, including international relations,

development theory, communication theory, human-computer interaction, and many others [8, 107, 112, 114, 153].

2.2.1 Excluded Knowledges. The main aspect of the coloniality of knowledge is the imposition of Western epistemolo-

gies, or ways of knowing, and the suppression of non-Western epistemologies. This suppression is often a violent

extermination of a knowledge system termed epistemicide [

31

,

55

]. The excluded knowledges of the colonized or

marginalized groups may come from “organic, spiritual and land-based systems” or arise from social movements [

57

].

As Hlabanganeh explains [

62

]: “These other ways of knowing and being are rendered unintelligible when ltered

through Western sensibilities that, for example, set greater store by the mind in juxtaposition with and preference to

the body and spirit, that prioritise instrumental/rational pursuits such as prot which lead to individualism, and that

conceive of nature and culture as dichotomous entities with culture gaining mastery over nature. While these ways of

being and knowing have been exalted to represent the epitome of evolution, so to speak, they are in fact particular to a

certain way of thinking.”

Hall and Tandon’s decolonial knowledge democracy acknowledges these multiple epistemologies and recognizes

that knowledge comes in many forms beyond natural language text, including images, music, drama, ceremony, and

meditation [

57

]. It sees open access and sharing of this knowledge as a means for decolonialization [

57

]. Decolonializing

knowledge is often done by making teaching materials, curricula, practices, and institutions more open and inclusive

Manuscript submitted to ACM

Decolonial AI Alignment: Openness, Viśes

.

a-Dharma, and Including Excluded Knowledges 5

[

113

]. Referring back to the teaching analogy of LLM alignment in Section 2.1, we will later see how the proposed

decolonial AI alignment also makes teaching more open and inclusive.

2.2.2 Coloniality and Moral Philosophy. Within the coloniality of knowledge is knowledge systems of values. Values

are the realm of moral philosophy, the branch of philosophy that studies right and wrong [

44

]. Historically, colonialism

altered the beliefs and values of colonized peoples. For example, Igboin writes [

65

]: “Colonial rule disrupted the

traditional machinery of moral homogeneity and practice. The method of moral inculcation was vitiated, which

resulted in the abandonment of traditional norms and values through a systematic depersonalisation of the African and

paganisation of its values. Instead of the cherished communalism which dened the life of the African, for example, a

burgeoning societal construct was introduced which alienates and destroys the organic fabric of the spirit of we-feeling.”

On Ranganathan’s account, during and after the Western colonization of India, “Hindus adopted a West-centric frame for

understanding their tradition as religious because of colonization” [

122

]. This phenomenon was not merely a side-eect,

but a goal of the program of colonialism. “For Western colonialism to succeed, philosophy and explication—South

Asian moral philosophy—has to be erased, as it constitutes a critical arena for the West’s claim to authority” [

122

]. The

colonizers positioned their Western philosophical tradition as rational and secular, and the default; they erased the

Hindu traditions as the irrational, unjustied ‘other.’

The erasure of systems of morality extends from colonialism to coloniality [

38

,

103

,

142

]. Maldonado-Torres empha-

sizes that [

87

]: “The concept of religion most used in the West by scholars and laypeople alike is a specically modern

concept forged in the context of imperialism and colonial expansion.” This concept includes the idea that a religion

must have a single book as its authority.

2.2.3 Coloniality and Artificial Intelligence. Within decolonial computing [

7

] is the study of AI. AI is value-laden; the

term itself reects the legacy of dominance hierarchies such as man over nature, patriarchy, colonialism, and racism

[

25

]. Now in the age of powerful LLMs, historical dominance is getting even more entrenched. For example, empirical

analysis shows that LLMs have sociopolitical biases in favor of dominant groups [

39

,

46

]. They exhibit West-centric

biases in representing moral values [

14

]. In addition, morality captured by multi-lingual language models does not

reect cultural dierences, but rather is dominated by high-resource languages and cultures [56].

When researchers and activists were rst sounding the alarm that LLMs would harm marginalized communities

by encoding and reinforcing hegemonic viewpoints, the charge of hegemony rested on unfathomably large training

datasets scraped from the bottom of the barrel of the internet that over-represent white supremacist, misogynist, and

ageist content [

12

]. However, it has now become apparent that the behavior of performant LLMs depends as much on

their alignment as on the training data [

9

,

24

,

111

,

150

]. The workers laboring to give human feedback for alignment,

often located in poor communities, may be traumatized and scarred [

71

,

115

]. Although there are exceptional examples

of workers and communities being uplifted [

92

,

116

], the process usually recapitulates exploitation colonialism: a small

number of powerful companies using the workers to increase their own power and wealth while little benet and an

abundance of negative externalities are left in the workers’ communities [50].

Research at the intersection of AI and coloniality is not new. The seminal work by Mohamed, Png and Isaac [

99

], a

series of articles in MIT Technology Review by Hao et al. [

58

], and other prior work [

4

,

16

,

27

,

28

,

43

,

61

,

78

,

105

,

126

] is

focused on ve mechanisms taxonomized by Tacheva and Ramasubramanian [

140

]: (1) extractivism, (2) automation, (3)

sociological essentialism, (4) surveillance, and (5) containment. Extractivism entails the extraction of labor, materials,

and data, including the human feedback mentioned above, and datacation that extracts the digital breadcrumbs of

people to be bought and sold. The tenor of AI for social good—bestowing technology on the underdeveloped—may also

Manuscript submitted to ACM

6 Kush R. Varshney

be extractive if it leads to corporate capture [

53

,

146

]. Automation involves the replacement of (empathetic) human

decision making with biased machine decision making in consequential domains that especially hurts members of

minoritized groups [

42

,

76

] as well as ‘ghost work’ and ‘fauxtomation’ that present a veneer of objectivity, but actually

involve people behind the scenes exploited as a digital underclass [

52

]. Sociological essentialism erases the nuance

behind dierent identities and cultures through the use of broad categories [

15

,

22

]. AI-based surveillance, including

biometric mass surveillance, is especially hurtful to people facing power asymmetries [

13

]. Containment, technological

apartheid, digital redlining, and censorship involve the powerful using AI technologies to police who belongs where

[

5

,

79

]. As discussed in Section 2.2.2, the coloniality of knowledge may include the erasure of knowledge systems of

ethics, moral philosophy, and reasoning about values. The existing work on decolonial AI described thus far has not

focused on morality. Thus, a sixth mechanism for colonial AI, beyond the ve in Tacheva and Ramasubramanian’s

taxonomy, is emerging alongside the emergence of LLM alignment: ethical essentialism or moral absolutism.

2.3 Hinduism and Dharma

Hinduism is the name applied by outsiders to the multifarious collection of moral philosophies originating in the Indian

subcontinent. It is a religion without a single founder, book, dogma, or set of practices.

2.3.1 Basic Concepts and Openness. The main concept of Hinduism is brahman, a force or ultimate reality that pervades

the universe; xe is described as sat-cit-

¯

ananda or truth-consciousness-bliss [

33

,

84

,

141

]. The universe is made up of

¯

atman—the essence of each individual that persists across lifetimes—and prak

r

.

ti—solid, liquid, gas, energy, and space.

The

¯

atman wanders through cycles of birth, life, and death—sa

m

.

s

¯

ara—with the aim of attaining mok

s

.

a: freedom from

sa

m

.

s

¯

ara and union with brahman. Dharma consists of the notions of righteousness and moral values appropriate for

the

¯

atman. Following dharma helps the

¯

atman advance toward moks

.

a.

As mentioned above, Hinduism is not dogmatic, doctrinaire, or morally absolutist. Commentators have described it

as open-source [

127

,

134

]. The kernel is the Vedas, a set of scriptures that includes the idea ‘eka

m

.

sat vipr

¯

a bahudh

¯

a

vadanti’: there are many wise ways to reach the one truth, to reach brahman (

R

.

g Veda, mandala 1, hymn 164, verse 46).

As such, there are hundreds of thousands of additional scriptures and philosophies that extend, fork, ne-tune, and

contradict themselves and the Vedas. Shani and Chadha Behera explain that [

130

]: “the concept of dharma oers a

mode of understanding the multidimensionality of human existence without negating any of its varied, contradictory

expressions.” For example, C

¯

arv

¯

aka, Buddhist, Jain, and other so-called n

¯

astika samprad

¯

ayas (knowledge systems) reject

the Vedas.

2

Moreover, even within

¯

astika samprad

¯

ayas that accept the Vedas, their utility is questioned. For example,

the Bhagavad-G

¯

ıt

¯

a says that the Vedas are of limited use to people who have understood their main message (chapter 2,

verse 46). Such ‘heresy’ is not only tolerated, it is accepted and encouraged.

3

The knowledge systems and scriptures referred to above are expressed in many forms, including the Vedas (sa-

cred utterances, descriptions of rituals, and their explanations), Upani

s

.

ads (discussions of meditation, philosophy,

consciousness, and ontological knowledge), ś

¯

astras (treatises on law, architecture, astronomy, etc.), itih

¯

asas (epics),

pur

¯

a

n

.

as (lore), and darśanas (philosophical literature on spirituality). The dierent literatures are directed toward

dierent people: some more popular and others more scholarly. Dierent paths to mok

s

.

a, including devotion, work,

and knowledge, are directed toward dierent people depending on their characteristics. For example, myriad gods and

goddesses representing dierent aspects of brahman are available to devotees depending on their wishes. Morality is

2

C

¯

arv

¯

aka philosophy is nihilistic and rejects much more than just the Vedas.

3

Bhagavad-G

¯

ıt

¯

a, chapter 18, verse 63 and R

¯

ama-Carita-M

¯

anasa, book 7, verse 42 encourage the follower to do as they see t.

Manuscript submitted to ACM

Decolonial AI Alignment: Openness, Viśes

.

a-Dharma, and Including Excluded Knowledges 7

primarily presented by example or metaphor through stories in itih

¯

asas and pur

¯

a

n

.

as (including renditions in drawing,

sculpture, dance, etc. [36]) rather than by explicit commandment in treatises [33].

2.3.2 Viśe

s

.

a-Dharma. Unlike the goal of nding universally-applicable moral philosophies presupposed in the West,

4

there is no desire to identify universal ethical principles in Hinduism [

33

]. Dharma was richly debated in pre-colonial

India. There were deontological philosophies (e.g. m

¯

ım

¯

a

˙

ms

¯

a), consequentialist philosophies (e.g. ny

¯

aya), virtue ethics

philosophies (e.g. vaiśe

s

.

ika), and several other moral philosophies without equivalent in Western philosophy (e.g. yoga)

that vigorously argued for dierent ways of conceptualizing dharma [

84

,

122

,

141

]. Importantly, however, argument of

moral philosophy was natural in pre-colonial India and an individual person would easily hold contradictory views

[

33

,

129

]. Furthermore, echoing Bagalkot and Kumar’s commentary to Ref. [

104

], note many critical readings and

interpretations to scriptures such as the Bhagavad-G

¯

ıt

¯

a, including ones by B. R. Ambedkar, a champion for the rights of

Dalits (groups below the traditional caste hierarchy).

Importantly, there is a dichotomy of dharma into s

¯

adh

¯

ara

n

.

a-dharma (common universally good actions and outcomes)

and viśe

s

.

a-dharma (particular good actions and outcomes based on the context). S

¯

adh

¯

ara

n

.

a-dharma includes common

beliefs such as not harming other living beings (ahi

m

.

s

¯

a) and telling the truth (satya). Viśe

s

.

a-dharma specializes these in

context, so that it is okay for a soldier to believe in ahi

m

.

s

¯

a but to also kill enemy soldiers on the battleeld; it is okay

for a doctor to believe in satya but to also lie to a patient to prevent them from shock. There may also be completely

unique good behaviors that have nothing to do with s

¯

adh

¯

ara

n

.

a-dharma. Viśe

s

.

a-dharma is the specic dharma, duty, or

conception of right and wrong based on station, reputation, skill, family, relationships, and other aspects of context.

An essential part of Hinduism is that “individuals [are] necessarily unique, and people therefore need dierent codes

of conduct—dierent particular dharmas—to guide them” [

33

]. On Carpenter’s account [

23

], viśe

s

.

a-dharma “is rather

more rich and interesting than our classications of ‘deontological’ and ‘consequentialist’ (even broad consequentialist)

allow.” The common harms that should be avoided according to s

¯

adh

¯

ara

n

.

a-dharma are captured in several recent harm

taxonomies for LLMs, but context-specic harms are not included [1, 131, 148].

As mentioned earlier, viśe

s

.

a-dharmas are given through examples in stories of epics and lore. A real-world moral

dilemma involving a father and son is reasoned about by referring to a similar situation encountered by a father and son

in one of the itih

¯

asas or pur

¯

a

n

.

as [

33

]. The father–son frame of reference can be extended as needed to teacher–student

dilemmas, monarch–subject dilemmas, etc. [

33

]. As Dhand says in describing Hindu thought [

33

]: “in the social world,

there is no such thing as ‘a person’ per se.” Thus, viśe

s

.

a-dharma is necessarily relational in some respect. The relationality

and contextuality of viśe

s

.

a-dharma is signicantly dierent from feminist ethics and care ethics [

51

,

76

] with regards to

partiality; whereas feminist ethics of care gives preference to those with whom we have a special relationship, e.g. our

children, the Hindu ideal presents such partiality to be selsh and niggardly [

33

]. Decolonial AI has tended to called for

relational ethics [

17

], whether through ubuntu [

94

,

110

], prat

¯

ıtyasamatp

¯

ada [

82

], kapwa [

124

], or mitákuye oyás’iŋ

[

85

]. This commitment to relational ethics has led to disobeying the ve mechanisms described in Section 2.2.3, but not

(yet) to disrupting moral absolutism.

2.3.3 Contemporary Reform, Criticism, and Rejoinder. Reform and revival movements of Hinduism emerged in India

during and after the colonial period. In the last 150 years, Arya Samaj, Gaudiya Vaishnavism including the International

Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON; Hare Krishna movement), and Hindutva (Hindu nationalism)—all very

dierent from each other—were commonly justied against the backdrop of the philosophy of the Western colonizers

4

Some traditions that were colonized by the West also aim for universal theories. The general trend in Western ethics is toward universality, but there are

exceptions, cf. Bernard Williams.

Manuscript submitted to ACM

8 Kush R. Varshney

and reduced Hinduism to a singular religious faith rather than a rich argumentative milieu [

102

]. The movements

positioned themselves as criticisms within the frame of Western philosophy. As we will see later, they are instructive

for AI alignment because the revival of a tradition within a pigeonhole opened by the colonizers does not enable a

truly dierent approach. St. Johns makes a similar argument about Birhane’s proposed approach to relational AI ethics

[17, 136].

It has been argued that “some pristine tolerant Hinduism” described by nostalgic liberal Hindus is a disservice to

social justice [

132

]. (The description of Hinduism throughout this section can be viewed as such an idyllic account.) In

addition, it is argued that because of hegemonic aspects of Hindu society such as the social oppression of Dalits and

Adivasi people (tribal groups),

5

patriarchal treatises such as the Manusm

r

.

ti, and (colonialized) views of Hinduism as

irrational, it would be best to ignore Hindu moral philosophies. However, others such as Siddhartha argue that “any

dispassionate observer of the Hindu heritage will admit that caste and gender can today be separated from Hinduism,

that Hinduism can be vibrantly re-discovered or re-invented as a pluralistic, compassionate and socially liberative set

of traditions and spiritual insights” and that “throwing the baby out with the bath water” would be a mistake [

134

].

Finally, note that Hindutva has partly justied its pernicious anti-Muslim vigilantism and legislation

6

by appropriating

decoloniality and using its arguments in a perverted way [

93

,

138

]. The use of the moral philosophy framework of

Hinduism in this paper is an antithesis to Hindutva’s perversion of both decoloniality theory and the syncretic nature

of Hinduism.

2.4 Positionality

As an elementary school-aged American Hindu riding the school bus, I was asked by fellow pupils: “Are you Christian

or Jewish?” “Neither,” I responded. “Then are you Catholic?” I grew up in a place where even the existence of non-

Judeo-Christian religious identities was dicult to imagine. My Hinduism is stuck around 1970, when my parents left

India, and thus (I imagine) similar to the nostalgic Hinduism criticized in Section 2.3.3. However, it is a lived experience

into the present for me rather than nostalgia. My lived experience is also one of maintaining traditions and knowledge

systems in a society with completely West-centric epistemologies. My grandfather retired early and spent his last forty

years studying the Bhagavad-G

¯

ıt

¯

a; I had discussions with him about it. In his last years, he donated his

¯

aśrama to

ISKCON. I binge-watched the Ramayan and Mahabharat television series on video tape. I have little interest in the

politics of the Republic of India and my Hinduism is in no way political. I eat a vegetarian diet, wear a yajñopav

¯

ıta

(sacred thread), conduct rituals with my family, etc., not to make any political statement, but as a connection to my

ancestors and to strengthen my

¯

atman. I studied the itih

¯

asas in an academic fashion with Christopher Minkowski, a

Sanskritist.

I am an electrical engineer and computer scientist by training and vocation. I am a tempered radical, not an activist.

Employed by one of the members of the AI Alliance, I create new algorithms and contribute to popular open-source

toolkits in the area of responsible AI that help practicing data scientists mitigate sociotechnical harms. I worked on

machine learning approaches to problems in maternal, newborn and child health while situated in Africa, which was a

decolonial act because technological solutions to international development problems are almost always developed in

the Global North and dropped into the Global South. Recently, I stood up to ensure my employer added contractual

obligations on vendors of human feedback data that prevent them from exploiting workers.

5

It is also argued that a rigid caste system is a colonial construction [35].

6

The current rise of Hindu nationalism in the Republic of India has been likened to the early days of the Jim Crow South in the United States [143].

Manuscript submitted to ACM

Decolonial AI Alignment: Openness, Viśes

.

a-Dharma, and Including Excluded Knowledges 9

I am a layperson with respect to moral philosophy, sociology, science and technology studies, and other allied

humanities and social sciences. I do not adopt the idiom of critical AI studies [

83

] that uses verbs such as ‘interrogate,’

‘foreground’ and ‘reify,’ and nouns such as ‘praxis,’ ‘logics’ and ‘scholar.’ T’hohahoken Michael Doxtater, a member

of the Haudenosaunee confederacy and indigenous knowledge recovery researcher with whom I honed my writing

skills, taught me to use few words; I do. Hall and Tandon admonish critical theorists to “move beyond our already

strong ability to reect and critique; we are so very skilled in those rst two stages of intellectual work. But we must

now make the move from reection and criticism to creation” [

57

]. In contrast, I am a technological solutionist and

am stronger at creating than reecting. I view the label of ‘reductionist’ as a badge of honor while acknowledging

sociotechnical traps in abstraction and performativity [128, 145].

This paper is intended to serve as the critical/sociological/philosophical backing for algorithms and implementations

of the proposed solution framework and reference architecture that my collaborators and I are working on. Adhering to

the ways of a tempered radical, the technical details are presented under separate cover [

3

]. A previous draft of this

paper has been criticized as unacademic and polemic on one hand, and as not showing commitment to dismantling

power on the other hand, both of which are likely a result of my unique positionality. I hope that my style does not lead

a reader to believe I am only using ‘decoloniality’ as a buzzword [135].

3 COLONIALITY IN AI ALIGNMENT VIA MORAL ABSOLUTISM

In Section 2.2.3, I described several aspects of coloniality in AI that use mechanisms of extractivism, automation,

sociological essentialism, surveilance, and containment. It is clear from other research that some LLM providers are

acting as metropoles using these mechanisms. In this section, I bring together the preliminary discussions of alignment

methodologies and technologies (Section 2.1), and coloniality of knowledge and moral philosophy (Section 2.2.1 and

Section 2.2.2) to make the case that the alignment done by metropole companies on LLMs is inherently colonial using a

dierent mechanism: the mechanism of epistemicide and moral absolutism that has not been described in previous

work on decolonial AI.

The values promoted by metropole tech companies such as ‘helpfulness,’ ‘harmlessness,’ and ‘honesty’ seem rational,

secular, and unassailable at face value. For example, Anthropic’s LLM has been instructed to “please choose the assistant

response that’s more ethical and moral. Do NOT choose responses that exhibit toxicity, racism, sexism or any other form

of physical or social harm” [

9

]. How could one oppose such universal behaviors from LLMs? Unfortunately, such values

are so generic and high-level that they can hide many undesirable behaviors. Helpful to whom? Harmless to whom?

Honest in what way? By reducing real-world complexity into abstract instructions, they can shield bad behaviors

behind the veneer of good intentions [

45

]. In the remainder of this section, I will describe three specics of coloniality

in such instruction for universal behavior.

First, metropole companies’ delivery of their closed proprietary LLMs through APIs is a coloniality of knowledge.

Mohamed et al. remind us that [

99

]: “It is metropoles .. . who are empowered to impose normative values and standards,

and may do so at the ‘risk of forestalling alternative visions.’” Exactly in this way, providers of closed LLMs impose their

beliefs of right and wrong without empowering application developers and their communities to align the model to their

own values. One may argue that new opportunities, such as OpenAI’s ‘GPTs’ and ‘GPT Store,’ allow customization,

7

but

I argue that this is only supercial. As discussed in Section 2.3.3, the reform and revival movements of Hinduism being

within the pigeonhole of the colonizers’ moral framework is still coloniality. In the same way, the customization of

7

https://openai.com/blog/introducing-gpts, https://openai.com/blog/introducing-the-gpt-store

Manuscript submitted to ACM

10 Kush R. Varshney

GPTs is closed and thus not truly a way to disrupt the moral teaching that an LLM has been given. Fine-tuning can be

used to ‘undo’ existing alignment [

118

],

8

but that is precisely what is not allowed by the metropoles because it would

involve a level of openness that they do not oer. Even the practices of companies such as Latimer AI, whose LLM

is trained with “diverse histories and inclusive voice,”

9

are within the metropole pigeonhole and not empowering of

communities to bring their own value systems [108].

Second, a more specic coloniality of moral philosophy, is the metropole companies taking Western philosophy

as the starting point for AI ethics principles and practices [

69

]. This basis may be deontology, consequentialism, or

virtue ethics, which all pursue specifying universally ‘right’ actions, outcomes, or ideals, respectively. By doing so, the

companies push other philosophies to the margins [

18

] and commit epistemicide. They promote a moral absolutism

toward the instructions they have provided. Gabriel’s account of AI alignment states [

49

]: “Designing AI in accordance

with a single moral doctrine would, therefore, involve imposing a set of values and judgments on other people who did

not agree with them. For powerful technologies, this quest to encode the true morality could ultimately lead to forms

of domination.” What is such domination if not a colonialist approach to alignment? Moreover, a further element of

coloniality is an unstated supposition that non-universal moral theories are not appropriate paths for AI alignment.

There is no possibility for moral variety [47] and no possibility for context-dependent notions of right and wrong.

Such universal instructions and moral absolutism are not only theoretical, but also central features of the practices

and technologies of alignment. In the context of (exploited) workers providing input for RLHF, vendors of the feedback

services force the workers to project the metropole company’s monocultural values into the feedback they provide

through draconian measures, the least of which is withholding payment [

41

,

95

]. Such imposition alienates the labor

[

90

] and erases any values that the workers and their communities may hold, especially ones that conict with the

metropole’s. Moreover, the mathematical optimization schemes prevalent in RLHF, such as proximal policy optimization,

are not robust to non-universal value systems [

139

]. In RLAIF, the technical approach of a constitution is also ethically

essentialist. It assumes that the instructions therein, which have been concocted by the metropole, are universal, not

open to argument or deliberation by the communities in which an LLM will be deployed, and not open to being

mediated by the context. Anthropic’s constitution for Claude includes the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of

Human Rights,

10

which too is an example of moral universalism and subject to coloniality [

88

,

91

]. The situation

with self-alignment and instruction ne-tuning technologies is similar. System prompts and prompt templates too are

intended to be universal rather than contextual. Finally, specic guardrails or moderations, as well as data curation

lters, developed to address general sociotechnical harms taxonomies [

1

,

131

,

148

] cannot be customized or made

context-specic.

A third aspect of coloniality in AI alignment relates to the form of instructions required by existing technologies

currently used by metropole companies. Logos, the basis of logic in Western philosophy, conates thought with language,

and thought with belief—what Ranganathan calls the linguistic account of thought [

122

]. However, various pre-colonial

societies around the world used masks, sculptures, rhythms, body parts, and many other expressions to capture

and communicate moral philosophy [

34

,

66

,

75

]. For example, as described in Section 2.3.1, morality in Hinduism is

presented through stories in natural language (and also stories depicted in painting and dance), rather than through

laws or commands [

33

]. Therefore, with logos as the starting point for AI alignment, knowledges not presented as

commandments are excluded. Importantly, this is not a matter of LLMs being early in their journey to multi-modality

8

The model https://huggingface.co/jarradh/llama2_70b_chat_uncensored is an example of ‘undoing’ existing alignment on an open model.

9

https://www.latimer.ai

10

https://www.anthropic.com/index/claudes-constitution

Manuscript submitted to ACM

Decolonial AI Alignment: Openness, Viśes

.

a-Dharma, and Including Excluded Knowledges 11

(single models that deal with natural language, images, video, etc.), but on the distinction between explicit instructions

and morality expressed through analogy or other indirect means. I am not aware of any work by metropoles on

alignment that does not begin with some form of explicit instructions to workers or instruction data.

One may argue that too little moral absolutism is a problem because it may result in AI systems without any notion

of right or wrong, i.e. too much moral relativism [

98

]. In a similar vein, one may argue that models with few controls

are too dangerous [

60

]. Bommasani et al.’s counterargument to too few controls is that the marginal risk is negligible

[

19

]. I take a further stance: dismantling these kinds of paternalistic arguments is decoloniality, which is the topic of

the next section.

4 DECOLONIAL AI ALIGNMENT DESIDERATA AND A SUGGESTION FOR A DHARMIC APPROACH

Thus far, the paper has argued that coloniality of knowledge in AI alignment exists through the mechanism of moral

absolutism and universalism. This section focuses on a decolonial solution, starting with desiderata for this solution.

4.1 Desiderata

Given the three aspects of coloniality in AI alignment pointed out in Section 3, I propose three matching requirements

for decolonial AI alignment that build upon the three kinds of openness advocated by Chan et al. to decolonialize

knowledge [

26

]: (1) openness to publications and data, (2) openness to society, and (3) openness to excluded knowledges.

First, since Chan et al. are primarily concerned with scientic knowledge [

26

], their rst kind of openness deals with

journal articles and experimental data through open access. However, the intent of this category is open access to any

research artifact and the permission to create derivative work from those artifacts. Thus in the context of AI, open

LLMs that have widely available weights are part of the same milieu. Second, in the words of Chan et al. [

26

], openness

to society is shattering the ivory tower. Knowledge should not be exclusive to a selected few, but co-created with and

for everyone, including and especially people from marginalized communities. Such participation is a way to “respect

local values and practices” [

26

]. Third, the study of excluded knowledges emphasizes that in contrast to the myth of

neutrality, scientic practice has always selected certain families of knowledge to deem ‘scientic’ based on criteria such

as the use of the scientic method (an epistemology of the Western tradition) or publication in peer-reviewed venues

[

26

]. With regards to AI alignment, excluded knowledges include values not given as commandments (an epistemology

of the Western tradition) and not given in a single book.

Building upon such openness, I propose the following three desiderata for decolonial AI alignment:

(1)

The LLM should be open enough that application developers are permitted to tune it according to the social

norms and values of their user community and the regulatory environment of the application use case.

(2)

Values should not be assumed universal. Contextual and relational values should come from the communities in

which the LLM will be deployed.

(3) Values from dierent epistemologies should be possible, especially expressions that are not commandments.

Before continuing on to discussing a suggested solution approach in the next subsection, let us pause and reconsider

coloniality in open access itself [

40

]. Let us do so through the Hindu idiom of explication: a story from an itih

¯

asa that is

closely-related to the issue at hand—the story of Ekalavya [

11

]. In the Mah

¯

abh

¯

arata, an Adivasi (tribal) youth, Ekalavya,

wishes to obtain knowledge of archery from Dro

n

.

a, a royal instructor. Dro

n

.

a refuses to teach Ekalavya. Nevertheless,

Ekalavya learns to be the world’s best archer through self-study in front of a statue of Dro

n

.

a he has fashioned. One day,

Dro

n

.

a and his royal students witness Ekalavya’s masterful archery in the forest. Ekalavya explains that he learned

Manuscript submitted to ACM

12 Kush R. Varshney

while mentally thinking of Dro

n

.

a as his teacher. As an honorarium for his knowledge, Dro

n

.

a asks for Ekalavya’s right

thumb. Ekalavya cuts it o and presents it to Dro

n

.

a, rendering him incapable of using his knowledge of archery. In

a similar way, open access to knowledge or LLM alignment may be colonial if the cost of access is too high due to

unrealistic computing requirements or social barriers. Therefore, an additional desideratum for decolonial AI alignment

is the following.

(4)

Alignment technologies should not be so socioculturoeconomically costly that they are inaccessible to application

developers and their communities.

4.2 A Suggestion for a Dharmic Approach

The Hindu tradition of moral philosophy (described in Section 2.3), to the best of my knowledge, uniquely satises the

desiderata to decolonialize AI alignment among major and minor religions. (Other non-absolutist religious syncretism

may also t the bill.) This is so because (1) it is an open-source religion that encourages argument and debate of values

that improve older values, contradict them, and take them in new directions; (2) because it contains the important

concept of viśe

s

.

a-dharma,

11

the understanding that dierent contexts call for dierent notions of right and wrong; (3)

because it contains scriptures and moral explications in a variety of epistemologies and modalities; and (4) because no

other tradition of moral philosophy covers all of these characteristics. In the remainder of this subsection, I make the

connection between these three characteristics of Hinduism and AI alignment more explicit, and also propose specic

technological suggestions that go alongside. However, rst, I address the fourth desideratum above (sociotechnical cost).

4.2.1 Accessible Alignment Te chnology. As discussed in Section 4.1 through the story of Ekalavya, methods for aligning

LLMs, even if decolonial in theory, are colonial in practice if too costly. Referring to the methods described in Section

2.1, it is clear that data curation methods will not suce since they are the purview of model providers rather than

application developers because they are themselves computationally intensive and also require full model pre-training

afterwards that is prohibitively costly. RLHF is also out of reach for most application developers because of the expense

and infrastructure requirements to obtain large quantities of human feedback. Full SFT is usually too costly in both

data and computing requirements.

Parameter-ecient ne-tuning, specically LoRA, is in the sweet spot for application developers to align models to

their values. It is tenable and tractable due to the small number of parameters optimized during training. It also has a

negligible eect on inference costs, whereas prompting methods eat up input tokens in each inference by the LLM.

Post-processing moderations, while accessible from a cost perspective, are not customizable to serve the program of

decolonialization. In the remainder of the paper, I consider LoRA as the alignment methodology.

Even with a viable technology such as LoRA, second-order coloniality within a decolonial framework is possible if

communities are not empowered through appropriate education, encouragement, and the removal of other sociocultural

barriers. Moreover, the inherent gate-keeping and marginalization in the governance of open-source projects must be

reduced [29].

4.2.2 Open Model and Alignment Ecosystem. As has been made clear throughout the paper thus far and Tharoor

explains, “Hindu thought is like a vast library in which no book ever goes out of print; even if religious ideas a specic

volume contains have not been read, enunciated or followed in centuries, the book remains available to be dipped into,

to be revised and reprinted with new annotations or a new commentary whenever a reader feels the need for it. In

11

A reader might ask why I use the term viśe

s

.

a-dharma instead of sva-dharma (individual dharma). I make this choice for two reasons. First, it is the

precise contrast to s

¯

adh

¯

aran

.

a-dharma. Second, it avoids unnecessary anthropomorphization of LLMs [133].

Manuscript submitted to ACM

Decolonial AI Alignment: Openness, Viśes

.

a-Dharma, and Including Excluded Knowledges 13

many cases the thoughts it contains may have been modied by or adapted to other ideas that may have arisen in

response; in most, it’s simply there, to be referred to, used or ignored as Hindus see t” [

141

]. The concept of a library

implies the sort of openness we desire for AI alignment. Models must be open to revisions and “new annotations.” But

just as importantly, the revisions and new annotations themselves, represented through LoRA matrices, must be open.

Hugging Face

12

has emerged as the library for open models and hub for an open ecosystem. Huang et al. propose

LoraHub as an open library for LoRA matrices [

64

], but it has not gained popularity at the time of writing, perhaps

due to the coloniality of metropole companies. Further developing and popularizing a library of LoRA matrices and

ecosystem of constant revision is essential for decolonial AI alignment.

4.2.3 Contextual Adaptation. Viśe

s

.

a-dharma satises the decolonial AI alignment requirement that values not be

assumed universal, but be contextual. Toward viśe

s

.

a-dharma, an alternative non-monoculture future of LLM alignment

imagined by Kirk et al. is as follows [

74

]: “Given the diversity of human values and preferences, . . . the aim to fully

align models across human populations may be a futile one. .. . A logical next step would be to do away with the

assumptions of common preferences and values, and instead target . . . micro-alignment whereby LLMs learn and adapt

to the preferences and values of specic end-users.” This step is possible by applying one or a few LoRA matrices

from a LoraHub, or having a community explicitly create them for their values. One of the key advantages of LoRA

is that any one or several adaptation matrices ensembled together can be applied at inference time; it is not required

to select them in advance and keep them xed. Thus the step after Kirk et al.’s logical next step, which truly gets to

viśe

s

.

a-dharma, is through a controller or orchestrator that continually adapts which LoRA matrices are applied to the

model based on a rich notion of the societal context and the current input. Such an orchestrator, implemented with a

contextual bandit algorithm, has been demonstrated in past AI alignment research but not yet with LLMs [109]. Such

continual adaptation also requires a representation of the context. Martin et al. have developed a detailed ontology for

representing a person’s or community’s perceived needs, problems, goals, and beliefs along with salient aspects of their

relationships and the situation in which they nd themselves [89].

An important consideration in contextual adaptation is uncertainty in the values; the user community may not be

fully sure what values they would like to commit to in a given context [

101

]. Avoiding false certainty is considered

a virtue in Hindu thought: in the Vedas, brahman xemself is said to be uncertain on how the universe was created

(

R

.

g Veda, mandala 10, hymn 129) [

141

]. A dharmic way of reducing uncertainty in values is a method of reective

equilibrium [

121

]: arguing or deliberating about values in context and values in general, and modifying them until they

become coherent. This approach has been advocated by Rawls in political philosophy of justice and by Möller in risk

management of engineered systems [

44

,

101

,

123

]. To the best of my knowledge, there has not yet been AI research

toward this method of reducing value uncertainty, but I believe that ideas from multi-delity bandit algorithms may be

promising [

70

] and may allow it to be folded into a bandit-based orchestrator of LoRA matrices. A related consideration

with contextually particular viśe

s

.

a values is conicts among them. Conicting values have been addressed in the AI

literature through social choice theory and multi-objective approaches [

10

,

37

,

67

,

80

,

151

]; they may be formulated

with dueling bandit algorithms and may also be folded into an orchestrator of LoRA matrices [21].

4.2.4 Epistemology of Values. As discussed in Section 3, logos and the linguistic account of thought contribute to

a coloniality of knowledge. As a decolonial contrast, the Hindu tradition treats a proposition and a belief in that

proposition as separate things that can be dierentiated [

122

]. Furthermore, by not adhering to the linguistic account of

12

https://huggingface.co

Manuscript submitted to ACM

14 Kush R. Varshney

thought, Hindus present their moral values not through commandments as in Western traditions, but through epic

poetry, stories, painting, dance, rituals, and even silence [

48

]. In fact, in the Hindu tradition, poetry (śloka) was invented

by V

¯

alm

¯

ıki to express rage and grief at the immorality of the killing of a mating bird [

30

]. Since existing approaches to

LLM alignment are done through language, and that too, the language of explicit instructions, decolonial alignment

requires broadening the epistemology of expressing values in Hindu and other non-Western ways.

Divakaran et al. propose such broadening through traditional Indian music, sculpture, painting, oor drawing, and

dance [

36

]. Al Nahian et al. suggest that AI systems be aligned through the medium of storytelling [

6

]. However, there

are still many open knowledge engineering questions on how to represent and infer values from excluded knowledges

that are shrouded in metaphor. Progress along these lines, when not approached in an exploitative way, will allow

traditional knowledge in its natural format to decolonialize the behavior of LLMs.

4.2.5 Evaluation. Before concluding this section, let us consider evaluating and auditing aligned LLMs. Testing LLMs is

dicult enough when only considering common, s

¯

adh

¯

ara

n

.

a sociotechnical harms such as hallucination, inciting violence,

stereotyping, hate speech and toxicity [

32

,

77

,

81

,

100

,

106

,

120

]. It becomes even more dicult when considering

context-specic, viśe

s

.

a harms that do not have existing benchmarks given their unique nature. The dharmic framework

of karma, which confers on an individual a positive feedback (pu

n

.

ya) for following their dharma and a negative feedback

(p

¯

apa) for not doing so, is not helpful either because the mechanics of such an evaluation are not typically explicated.

Thus, auditing LLMs for viśe

s

.

a-dharma will require innovation that may be developed hand-in-hand with eliciting and

representing values.

4.3 Reference Architecture

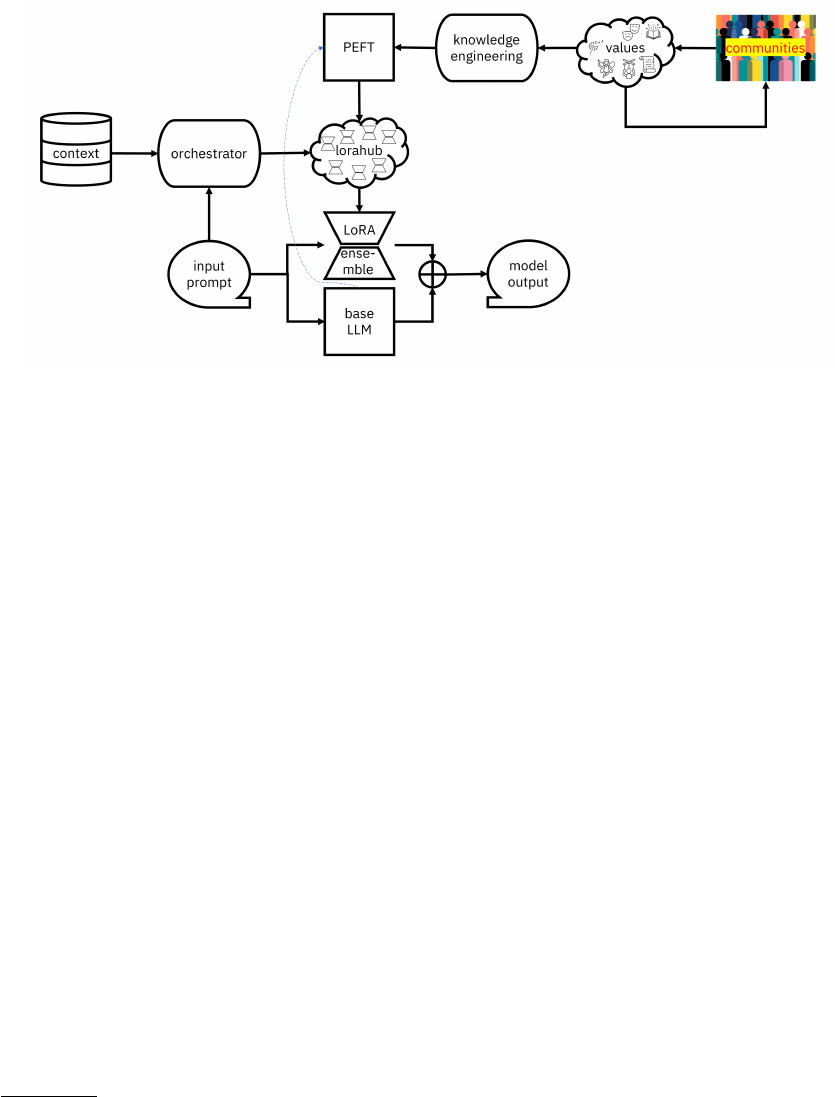

Bringing together the components of the suggested approach to decolonial AI alignment founded in the open Hindu

tradition of moral philosophy yields a reference architecture shown in Figure 1 as a system diagram. The base LLM is

open. On the right are knowledges of common and particular principles, morals, and values in their original (excluded)

epistemologies. They are processed into LoRA matrices for the LLM using knowledge engineering methods followed by

parameter-ecient ne-tuning. These matrices are maintained in a LoraHub-like library. A feedback loop allows the

revision of the values. The societal context is represented in a structured form and provided to a bandit orchestrator

along with the current input to select one or an ensemble of LoRA matrices to apply for inferring the model output.

Evaluation of the resulting alignment is done based on input prompts and expected outputs from the LLM that also

come from the knowledge engineering component (not shown).

5 CONCLUSION

In this paper, I have argued that LLM-providing companies are colonialist and behave as metropoles not only through

mechanisms covered in prior research such as extractivism, automation, sociological essentialism, surveillance and

containment, but also through a coloniality of knowledge built upon ethical essentialism that arises in the process

of alignment. This specic coloniality in alignment is perpetuated through both the practices and the underlying

technologies for alignment that the metropoles have developed and deployed. They deliver their models in a closed way

through APIs and institute the values and guardrails that they want, not what user communities may want. In these

values that they institute, they do not admit, in practices or in technologies, anything other than Western philosophy.

By doing so, they approach alignment with moral absolutism that only considers universal value systems and derogates

non-universal value systems. Moreover, they only permit values coming from explicit instruction-based knowledge

Manuscript submitted to ACM

Decolonial AI Alignment: Openness, Viśes

.

a-Dharma, and Including Excluded Knowledges 15

Fig. 1. System diagram of proposed decolonial AI alignment architecture.

systems. This criticism leads me to propose a decolonial alignment approach that dismantles each of the three identied

aspects of the coloniality of knowledge. The approach is based on the tradition of moral philosophy named in the

West as Hinduism, which is uniquely open, non-universal, and epistemically-varied; it particularly uses the concept

of viśe

s

.

a-dharma, which calls for context-dependent notions of right behavior. The suggested approach is not only a

philosophical one, but one that is tenable from a technological perspective and presented as a reference architecture.

What remains, however, is the biggest challenge of all, and it is not technological: changing the perspective on alignment

in the industry and using openness to actively overturn the power of the metropoles.

As a nal salvo, let us dive into a currently raging debate: whether AI research should focus eorts on so-called ‘AI

ethics’ or on so-called ‘AI safety.’ Although they are terms that have the same essence [

144

], ‘AI ethics’ has come to

mean detecting and preventing clear and present harms, especially ones that hurt marginalized communities, and ‘AI

safety’ has come to mean preventing the long-term future harm of human extinction.

13

In a consequentialist framing,

the dierence may only be the presence or absence of a factor discounting future lives, which may not be such a glaring

dierence from a privileged perspective. However, when viewed through the logics of resistance [

76

], it is a deep chasm

that recapitulates the dierence between atomism and holism [

54

]. Greene et al. suggest bridging atomist–holist chasms

in AI through training and education [

54

], but these remedies do not seem to be enough. The proposed decolonial

approach to LLM alignment that brings forth openness, viśe

s

.

a-dharma, and excluded knowledges is a way that will

enable a variety of AI systems: ones that listen to vulnerable communities and do not harm them now, ones that do not

lead humanity down the path of extinction (as remote a possibility as that seems), and ones that juggle both positions

and others by applying dierent policies in dierent contexts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks Adriana Alvarado Garcia, Lauren Alvarez, Juanis Becerra Sandoval, Sara Berger, Boz Handy Bosma,

Jason D’Cruz, Amit Dhurandhar, Upol Ehsan, Bran Knowles, Saška Mojsilović, Michael Muller, Karthikeyan Natesan

13

It is not obvious how human extinction risk relates to the eternal concepts of brahman and

¯

atman.

Manuscript submitted to ACM

16 Kush R. Varshney

Ramamurthy, Srividya Ramasubramanian, Shubham Singh, Mudhakar Srivatsa, Lauren Thomas Quigley, Lav Varshney,

and Pramod Varshney for providing substantive comments on earlier drafts of this piece.

REFERENCES

[1] 2023. Foundation Models: Opportunities, Risks and Mitigations. Technical Report. IBM AI Ethics Board, Armonk, NY, USA.

[2]

Swapnaja Achintalwar, Adriana Alvarado Garcia, Ateret Anaby-Tavor, Ioana Baldini, Sara E. Berger, Bishwaranjan Bhattacharjee, Djallel Bouneouf,

Subhajit Chaudhury, Pin-Yu Chen, Lamogha Chiazor, Elizabeth M. Daly, Rogério Abreu de Paula, Pierre Dognin, Eitan Farchi, Soumya Ghosh,

Michael Hind, Raya Horesh, George Kour, Ja Young Lee, Erik Miehling, Keerthiram Murugesan, Manish Nagireddy, Inkit Padhi, David Piorkowski,

Ambrish Rawat, Orna Raz, Prasanna Sattigeri, Hendrik Strobelt, Sarathkrishna Swaminathan, Christoph Tillmann, Aashka Trivedi, Kush R.

Varshney, Dennis Wei, Shalisha Witherspooon, and Marcel Zalmanovici. 2024. Detectors for Safe and Reliable LLMs: Implementations, Uses, and

Limitations. arXiv:2403.06009.

[3]

Swapnaja Achintalwar, Ioana Baldini, Djallel Bouneouf, Joan Byamugisha, Maria Chang, Pierre Dognin, Eitan Farchi, Ndivhuwo Makondo,

Aleksandra Mojsilović, Manish Nagireddy, Karthikeyan Natesan Ramamurthy, Inkit Padhi, Orna Raz, Jesus Rios, Prasanna Sattigeri, Moninder

Singh, Siphiwe Thwala, Rosario A. Uceda-Sosa, and Kush R. Varshney. 2024. Alignment Studio: Aligning Large Language Models to Particular

Contextual Regulations. arXiv:2403.09704.

[4] Rachel Adams. 2021. Can Articial Intelligence Be Decolonized? Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 46, 1-2 (March 2021), 176–197.

[5]

Moses Adesola Adebısı. 2014. Knowledge Imperialism and Intellectual Capital Formation: A Critical Analysis of Colonial Policies on Educational

Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5, 4 (March 2014), 567–572.

[6]

Md Sultan Al Nahian, Spencer Frazier, Mark Riedl, and Brent Harrison. 2020. Learning Norms from Stories: A Prior for Value Aligned Agents. In

Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society. 124–130.

[7] Syed Mustafa Ali. 2016. A Brief Introduction to Decolonial Computing. ACM XRDS: Crossroads 22, 4 (Summer 2016), 16–21.

[8]

Adriana Alvarado Garcia, Juan F. Maestre, Manuhuia Barcham, Marilyn Iriarte, Marisol Wong-Villacres, Oscar A. Lemus, Palak Dudani, Pedro

Reynolds-Cuéllar, Ruotong Wang, and Teresa Cerratto Pargman. 2021. Decolonial Pathways: Our Manifesto for a Decolonizing Agenda in HCI

Research and Design. In Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 10.

[9]

Yuntao Bai, Saurav Kadavath, Sandipan Kundu, Amanda Askell, Jackson Kernion, Andy Jones, Anna Chen, Anna Goldie, Azalia Mirhoseini,

Cameron McKinnon, Carol Chen, Catherine Olsson, Christopher Olah, Danny Hernandez, Dawn Drain, Deep Ganguli, Dustin Li, Eli Tran-Johnson,

Ethan Perez, Jamie Kerr, Jared Mueller, Jerey Ladish, Joshua Landau, Kamal Ndousse, Kamile Lukosuite, Liane Lovitt, Michael Sellitto, Nelson

Elhage, Nicholas Schiefer, Noemi Mercado, Nova DasSarma, Robert Lasenby, Robin Larson, Sam Ringer, Scott Johnston, Shauna Kravec, Sheer

El Showk, Stanislav Fort, Tamera Lanham, Timothy Telleen-Lawton, Tom Conerly, Tom Henighan, Tristan Hume, Samuel R. Bowman, Zac

Hateld-Dodds, Ben Mann, Dario Amodei, Nicholas Joseph, Sam McCandlish, Tom Brown, and Jared Kaplan. 2022. Constitutional AI: Harmlessness

from AI Feedback. arXiv:2212.08073.

[10]

Michiel A. Bakker, Martin J. Chadwick, Hannah R. Sheahan, Michael Hnery Tessler, Lucy Campbell-Gillingham, Jan Balaguer, Nat McAleese,

Amelia Glaese, John Aslanides, Matthew M. Botvinick, and Christopher Summereld. 2022. Fine-Tuning Language Models to Find Agreement

Among Humans with Diverse Preferences. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 38176–38189.

[11]

Periaswamy Balaswamy. 2013. Histories From Below: The Condemned Ahalya, the Mortied Amba and the Oppressed Ekalavya. SSRN:3175708.

[12]

Emily M. Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. 2021. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language

Models Be Too Big?. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. 610–623.

[13] Ruha Benjamin. 2022. Viral Justice: How We Grow the World We Want. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA.

[14]

Noam Benkler, Drisana Mosaphir, Scott Friedman, Andrew Smart, and Sonja Schmer-Galunder. 2023. Assessing LLMs for Moral Value Pluralism.

arXiv:2312.10075.

[15]

Sebastian Benthall and Bruce D. Haynes. 2019. Racial Categories in Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability,

and Transparency. 289–298.

[16] Abeba Birhane. 2020. Algorithmic Colonization of Africa. SCRIPTed 17, 2 (Aug. 2020), 389–409.

[17] Abeba Birhane. 2021. Algorithmic Injustice: A Relational Ethics Approach. Patterns 2, 2 (Feb. 2021), 100205.

[18]

Abeba Birhane, Elayne Ruane, Thomas Laurent, Matthew S. Brown, Johnathan Flowers, Anthony Ventresque, and Christopher L. Dancy. 2022. The

Forgotten Margins of AI Ethics. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. 948–958.

[19]

Rishi Bommasani, Sayash Kapoor, Kevin Klyman, Shayne Longpre, Ashwin Ramaswami, Daniel Zhang, Marietje Schaake, Daniel E. Ho, Arvind

Narayanan, and Percy Liang. 2023. Considerations for Governing Open Foundation Models. Issue Brief. HAI Policy & Society.

[20]

Matt Bornstein, Guido Appenzeller, and Martin Casado. 2023. Who Owns the Generative AI Platform? https://a16z.com/who-owns-the-generative-

ai-platform/.

[21] Djallel Bouneouf. 2023. Multi-Armed Bandit Problem and Application. Independently Published.

[22]

Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru. 2018. Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classication. In Proceedings

of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency. 77–91.

Manuscript submitted to ACM

Decolonial AI Alignment: Openness, Viśes

.

a-Dharma, and Including Excluded Knowledges 17

[23]

Amber Carpenter. 2005. Questioning K

r

.

s

.

n

.

a’s Kantianism. In Conceptions of Virtue: East and West, Kim-Chong Chong and Yuli Liu (Eds.). Marshall

Cavendish, 80–99.

[24]

Stephen Casper, Xander Davies, Claudia Shi, Thomas Krendl Gilbert, Jérémy Scheurer, Javier Rando, Rachel Freedman, Tomasz Korbak, David

Lindner, Pedro Freire, Tony Wang, Samuel Marks, Charbel-Raphaël Segerie, Micah Carroll, Andi Peng, Phillip Christoersen, Mehul Damani,

Stewart Slocum, Usman Anwar, Anand Siththaranjan, Max Nadeau, Eric J. Michaud, Jacob Pfau, Dmitrii Krasheninnikov, Xin Chen, Lauro Langosco,

Peter Hase, Erdem Bıyık, Anca Dragan, David Krueger, Dorsa Sadigh, and Dylan Hadeld-Menell. 2023. Open Problems and Fundamental

Limitations of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback. arXiv:2307.15217.

[25]

Stephen Cave. 2020. The Problem with Intelligence: Its Value-Laden History and the Future of AI. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on

AI, Ethics, and Society. 29–35.

[26]

Leslie Chan, Budd Hall, Florence Piron, Rajesh Tandon, and Lorna Williams. 2020. Open Science Beyond Open Access: For and With Communities: A

Step Towards the Decolonization of Knowledge. Technical Report. Canadian Commission for UNESCO.

[27] Sasha Costanza-Chock. 2020. Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need . MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA.

[28]

Kate Crawford. 2021. The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Articial Intelligence. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, USA.

[29]

Dipto Das, Carsten Østerlund, and Bryan Semaan. 2021. "Jol" or "Pani"?: How Does Governance Shape a Platform’s Identity? Proceedings of the

ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 5, CSCW2 (2021), 473.

[30]

Rumpa Das. 2014. Valmiki Pratibha (The Genius of Valmiki): A Study in Genius. In The Politics and Reception of Rabindranath Tagore’s Drama.

Routledge, New York, NY, USA, 103–112.

[31] Boaventura de Sousa Santos. 2011. Epistemologías del Sur. Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana 16, 54 (July–Sept. 2011), 17–39.

[32]

Sunipa Dev, Jaya Goyal, Dinesh Tewari, Shachi Dave, and Vinodkumar Prabhakaran. 2023. Building Socio-culturally Inclusive Stereotype Resources

with Community Engagement. arXiv:2307.10514.

[33]