PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal

Volume 16

Issue 1

Environmental, Societal, and Scienti>c

Investigations: Undergraduate Research During

COVID-19

Article 9

2023

Science Literacy and Popular Culture: Forensic Science Literacy and Popular Culture: Forensic

Anthropology in Application and Fiction Anthropology in Application and Fiction

Autumn L. Baker

Portland State University

Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mcnair

Let us know how access to this document bene>ts you.

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Baker, Autumn L. (2023) "Science Literacy and Popular Culture: Forensic Anthropology in Application and

Fiction,"

PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal

: Vol. 16: Iss. 1, Article 9.

https://doi.org/10.15760/mcnair.2023.16.1.9

This open access Article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-

ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). All documents in PDXScholar should meet accessibility

standards. If we can make this document more accessible to you, contact our team.

Science Literacy and Popular

Culture: Forensic

Anthropology in Application

and Fiction

McNair Research Thesis Scholar: Autumn Baker

Mentors: Dr. Michele Gamburd and Dr. Amiee Potter

September 30, 2022

Abstract

This exploratory research examines the discussion of “race” in popular cultural media in a

forensic anthropological context. The TV series Bones was used as a sample site for a cultural

comparative analysis. This research critically compares popular culture understandings of “race”

or ancestral heritage as depicted in Bones with a specific, newly developed method that forensic

anthropologists apply in actual lab procedures in combination with other methods to determine

ancestral heritage as depicted in textbooks. This research project has two phases. The first phase

is a media analysis of discussions and depictions of ancestral heritage in episodes of Bones; the

second phase uses osteology lab work with biological specimens in the Portland State University

and Portland Community College Sylvania Campus osteology collections. People may acquire

science literacy through popular culture and social media sources, and inaccurate depictions and

misapprehensions may adversely affect people’s understanding of human biological diversity

and ancestral heritage. This study contributes to the ongoing effort in biological anthropology to

undo the concept of biological “race” and to portray accurate information about how human

variation occurs on gradients or clines by examining possible influences in the public’s

understanding of science from popular media representations to create better overall science

literacy concerning human variation.

Science Literacy and Popular Culture:

Forensic Anthropology in Application and

Fiction

This study inquires if popular media presentations of forensic anthropology depict accurate

human biological science. The information depicted may influence how people understand the

biological realities of human ancestral origin or “race.” Studies have shown that bias or

misinformation in TV programming, whether accidental or intentional, influences the behavior

and opinions of the consumer audience (Ellingsen and Hernæs 2018; Jensen and Oster

2009). Science literacy concerning “race” in a forensic context is important for the general public

because incorrect assumptions about the biological nature of human variation garnered from

media representations are a part of the larger socio-cultural framework of racialism and racism

(Kondo 2018, 25-34).

The United States National Center for Education Statistics (1996, 22) defines science literacy as

"the knowledge and understanding of scientific concepts and processes required for personal

decision making, participation in civic and cultural affairs, and economic productivity." This

conception of science literacy is fundamentally influenced in the general public by sources such

as television, film, and social media (Hall 2011, 81-84). My research has focused on observing

some of the lab methods for assessing ancestral heritage that are portrayed on the TV crime

drama Bones and evaluating those sampled methods against similar forensic anthropological lab

methods to evaluate them for validity.

The purpose of this study is to explore if the TV series Bones paints an accurate portrayal of

forensic anthropological assessments of “race” or ancestral heritage. Bones, a popular TV crime

drama inspired by novels written by actual forensic anthropologist Kathy Reichs, depicts a

forensic anthropologist working in the field and the lab with other forensic pathologists,

scientists, and representatives from other branches of law enforcement (Flatow and Reichs

2012). Much of the understanding that people have about forensic anthropology’s methods,

capabilities, and practices may come from TV and film depictions on late night “true crime”

reenactments and procedural police dramas (Alduraywish, et al. 2022). In this research I have

reproduced the methodological approaches depicted in Bones to the best of my present

capabilities as a graduate student and then tested them by using a real-world discipline specific

method and dataset that most closely correspond to the fictional one to compare the analysis

techniques for creating ancestral heritage estimations in biological profiles. I focus my research

on human skulls.

Misrepresentation of specialized scientific procedures may influence opinions in the public and

judicial arenas such as in murder cases, wherein there might be an expectation of instantaneous

identification, DNA results, or other pathological evidence. This may be based upon

misinformation about what is possible or realistic for crime lab processing as seen in CSI or

Bones type crime drama television programs (Kruse 2010; Lawson 2009; Shelton, et al. 2009;

Smith, et al. 2011). Possible misapprehensions gained from pop-media fictions may contribute to

science illiteracy which may influence socially and culturally dysfunctional outcomes,

particularly in marginalized populations.

This study focused on the sampled depictions of forensic anthropological methods relating to

ascertaining the ancestral heritage of human remains on the TV crime series Bones. However,

Bones sometimes depicts non-existent “technology” such as using advanced computer holograms

to conjure the image of the victim instantly or make casual use of existing technology, such as

DNA processing, that is too expensive for many real-world crime labs (University of Nebraska

Medical Center 2022). Directors and screenwriters might use these types of fictions to allow the

show to fit in a brief timeslot and to make the drama of the show the focus for the audience. This

dramatization may cut out vital methodological processes and procedural approaches, so that

what is depicted can unintentionally misguide the viewer about what is possible or practical in a

forensic anthropological context (Taylor and Jaeger 2022, 31-36).

Literature Review

The general public’s comprehension concerning scientific processes and methods may be

attributed to a combination of a fundamental lack of science literacy and popular media,

including social media spreading disinformation or, conversely, valid information that is possibly

missing enough context to be misleading (Salmon et.al. 2015; Zarocostas 2020).

In my analysis of popular culture, I have used audience theory to examine the content of the TV

portrayals of forensic anthropological methodologies (Ruddock 2006). Audience theory seeks to

understand if the audience is a passive or active observer in the narrative and worldbuilding, and

if the audience is addressed as an individual or as a part of a larger population. I observed if there

is an inherent implication that the audience is addressed singularly, en masse, or if the narrative

itself is the target of the information (Ruddock 2006). In my analysis of Bones, I have found that

the viewer is being addressed as an active participant rather than a passive population or

individual. In other words, I believe the writers may expect the audience to be an engaged agent

with the program they are watching rather than having the program playing in a public venue as

a backdrop, like an advertisement (Taylor and Jaeger 2022, 131-135).

I have also assessed if there is an assumed level of science literacy that the target audience has.

To determine this, I have considered the framing, knowledge-gap, and cultivation theories under

the audience parent theory, which has allowed me to observe that Bones may be depicting a

culturally influenced selective view of reality which might allow the observed media to influence

social reality (Taylor and Jaeger 2022, 131-135). Depictions of an inaccurate interpretation of

social or scientific reality may allow the consumer media to influence social beliefs concerning

marginalized groups and science literacy (Gerbner and Gross 1976; Webster and Ksiazek 2012).

Human variation that manifests in superficial or phenotypic characteristics has been the basis for

racist ideologies about human categorization since the eighteenth-century, when Swedish

naturalist Carl Linnaeus first proposed a classification system for modern humans that included

four distinct categories (i.e., races): Homo sapiens americanus, asiaticus, africanus, and

europaeus, representing Indigenous Americans, Asians, Africans, and Europeans respectively.

Harvard professor Earnest Hooten (1887-1954) later reframed these cranial morphological trait

categories into three major racial groups: Negroid, Mongoloid, and Caucasoid (Christensen,

Passalacqua, and Bartelink 2019, 274-277). This racial classification was pivotal in the cultural

proliferation of scientific racism or racial essentialism that fostered the idea that character traits

such as intellect or morality were biologically based on morphological characteristics

(Christensen, Passalacqua, and Bartelink 2019, 274-277; Müller-Wille 2014, 597-606). These

superficial morphological differences have been propagandized in visual pop-culture since the

beginning of film media in the US as a tool for marginalization of othered or outsider

populations (Taylor and Jaeger 2022, 131-135).

Due to advances in DNA technology, we now know that ~90% of human genetic variation can

be found in a single population from Europe, Asia, or Africa, and only ~15% would be

contributed if the other mentioned populations were added (Foster and Sharp 2022). This means

that humans vary less genetically than other primates. It is now genetically proven that the

proportion of human genetic material that is variable is consistent across populations and that if

we add India then the percentage shrinks to ~10% (Jorde and Wooding 2004). This informs us

that humans only vary slightly on the genetic level due to a recent common ancestor, and that

only a minimal portion of this variation is continental population specific (Foster and Sharp

2022; Jorde and Wooding 2004). Biologically, humans have more genetic diversity within a

population than between populations. “Race” doesn’t exist biologically; it is a socio-cultural and

political ideology used to colonize, exploit, and marginalize people based on superficial

differences in appearance by those in positions of systematically constructed privilege and power

(Chou 2017).

Today, many biological anthropologists think of human morphological variation in terms of

clinal variation rather than “race.” Biologist Julian Huxley conceptualized clinal variation to

describe gradual and continual morphological variation in a species across a broadly dispersed

area. In contrast, the concept of “race” describes a population geographically isolated from its

parent species long enough to develop significantly distinct characteristics (Christensen,

Passalacqua, and Bartelink 2019, 274-277). Biologically and anthropologically, many scholars

now recognize that “race” does not exist in the human species outside of socio-cultural identities

(Fujimura, et al. 2014). The concept of easily categorized racial groups is based on the colonial

ideology that ancestral heritage can be assessed by a few macromorphological traits that can be

quickly and simply observed owing to extreme human variations in ancestral populations. This

construct discounts the dynamic and constantly shifting cultural, ethnic, and social realities that

form the basis of what is perceived as race in western ideology. Human variation occurs on

clines or gradients and is based on geography and environment and do not meet the biological

criteria for race (Bethard and DiGangi 2021; Yosso 2020, 5-13; Christensen, Passalacqua, and

Bartelink 2019, 274-277).

The causal effect of a misinformed science literacy might manifest as a socially shared cognitive

bias that may disallow a person or group to believe accurate information because their shared

ideology may have been initially rooted in bad information (Spalding 2020). This form of

possible cognitive bias may also manifest indirectly when an individual or population is

represented in a scene by a character’s mention, but not by on-screen presence for example,

when a character in a position of authority mentions the population as a plot device when

referencing a decedent. This may place the passive or theoretical population in an outsider

category and might simultaneously allow the majority audience to relate further to the authority

or insider representation (Kondo 2018, 25-34).

Social and cultural models of information exchange exist within a paradigm that may put the

individual and their identity first and the environment within which the information exists as

secondary. This can manifest as an individual’s demographic information being conflated with

their identity, which may remove context from personal circumstances. This may allow the

media consumer to experience the media from an impersonal perspective that centers the

narrative over its relationship to reality, but which may have detrimental effects on marginalized

populations by lacking accurate representation. In Bones, the forensic scientists possibly

represent pillars of the scientific community. They may represent authority through their

specialization and expertise, and that authority may make the information they reveal seem

trustworthy to the audience, even if the populations represented only exist within the

environment as a narrative device (Siebers 2019, 39-47).

The prospect of this study is to contribute to the ongoing effort in biological anthropology to

undo the cultural concept of biological “race” and to portray accurate information about how

human variation occurs on gradients or clines by examining possible influences in the public’s

understanding of science from popular media representations in order to create better overall

science literacy concerning human variation (Jorde and Wooding 2004). Using pop-cultural

representations of forensic anthropology procedures as a test-site, I examine how pop-cultural

depictions in Bones may present racist bias in the form of scientific bioessentialism (Dirkmaat et

al. 2008, 33-52; Soylu Yalcinkaya, Estrada-Villalta, and Adams 2017).

Methodology

This research critically assesses if pop media may expose the viewing audience to possible

misinformation of biological science by portraying inaccurate or incomplete ideas of human

skeletal variation in an authoritative manner. In my research design, I have evaluated a sample of

pop-media forensic anthropology from Bones for the validity of the methods depicted. To

achieve this goal, I have examined human skeletal variation and cranial indicators associated

with ancestral heritage while utilizing discipline standard practices of applied forensic

anthropology (Christensen and Passalacqua 2018; Byers 2018, 131-50; Christensen and

Passalacqua 2018, 127-30).

The research design has two parts. First, I observed the ways in which Bones depicts possible

ancestral biological profiles and evaluated how accurate those methods are in practice. I gathered

comparative data by watching episodes of the series Bones. I selected episodes for critical

analysis using synopses provided on the websites IMDb and Wikipedia (IMDb 2005; Wikipedia

2022). I selected episodes with the keywords “race,” “ancestral estimation,” ”biological profile,”

“ancestral origin,” or “racial identity” to locate scenes that depict ancestral estimation in

biological profiles using discipline-accepted assessment techniques (Christensen and Passalacqua

2018, 127-30). My search using those terms garnered 23 episodes, of which I discuss 3 in detail

in this essay. I worked during the summer of 2022 to locate 10 scenes with these procedures

depicted in my sample. I chose these 10 scenes at random from the 23 that came from my search

results. I watched the 10 random scenes and chose 3 to analyze because they had more

information about how the forensic anthropologist reached their conclusion about the decedent's

ancestral heritage. I have used critical theory and narrative analysis to analyze these episodes by

looking for patterns in how the script and actors address biological profile estimation (Bernard

2011; Christensen 2018, 35-41, 101-09, 127-130; Ruddock 2006; Webster and Ksiazek 2012;

White, Black and Folkens 2012, 379-426).

Second, I made the estimation that the closest approximation to the macroscopic visual

observations gathered from scenes in Bones in my sample set would be Optimized Summed

Scoring Attributes (OSSA) method (Christensen and Passalacqua 2018, 127-36). I used the

OSSA categorization method to evaluate crania in the teaching collections at Portland State

University and Portland Community College-Sylvania. The OSSA method allowed me to score

specific locations on the skull by visual assessment to estimate likely ancestral heritage. The

OSSA method scores cranial features on a scale that, when totaled, gives an approximation of

ancestral heritage. I then compared this analytic technique to the macroscopic assessment

techniques portrayed in my samples of Bones episodes. I compared how long the analysis took,

how difficult it was to perform, and how accurately the techniques could predict ancestral

heritage. Specifically, I performed macroscopic, morphoscopic analysis using the OSSA method

to estimate the ancestral heritage of the available samples (Christensen and Passalacqua 2018,

127-36). I decided not to use craniometric estimation techniques because these were not common

in my observed samples of the show and I do not have the training necessary to complete this

method of assessment accurately without expert supervision.

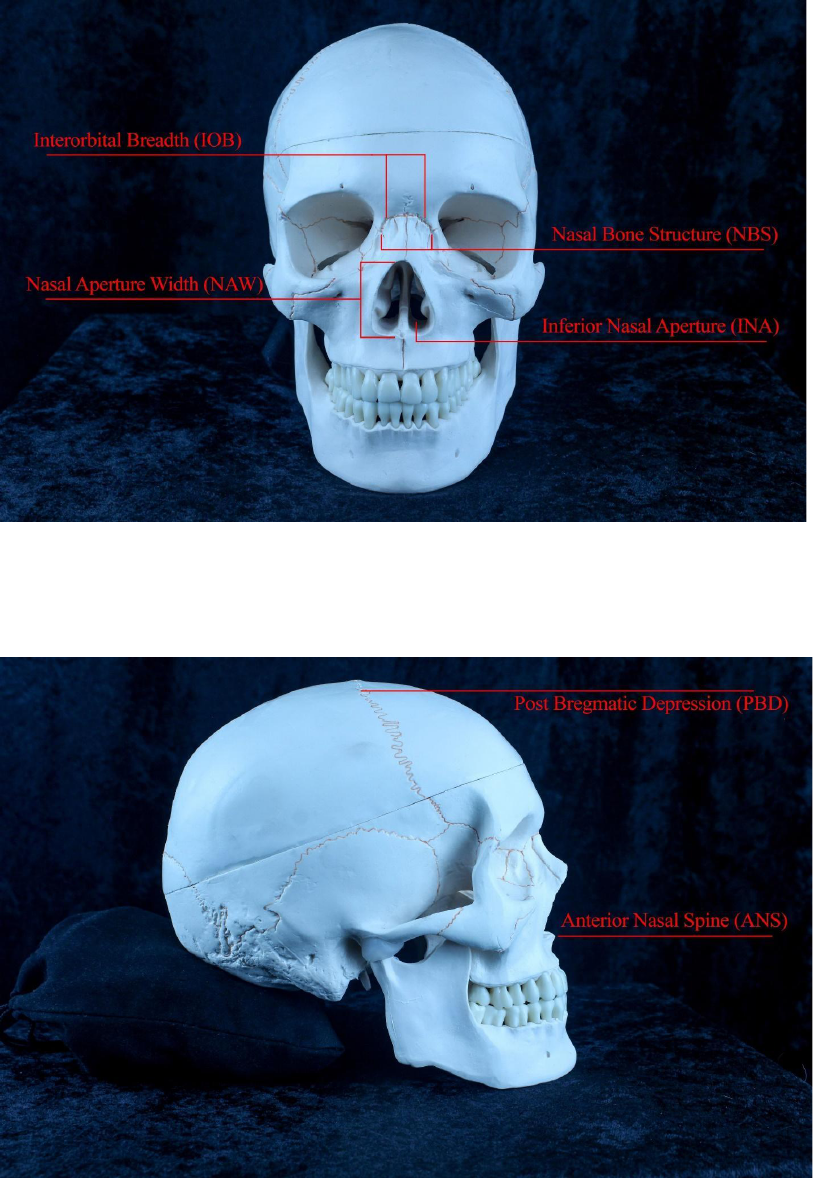

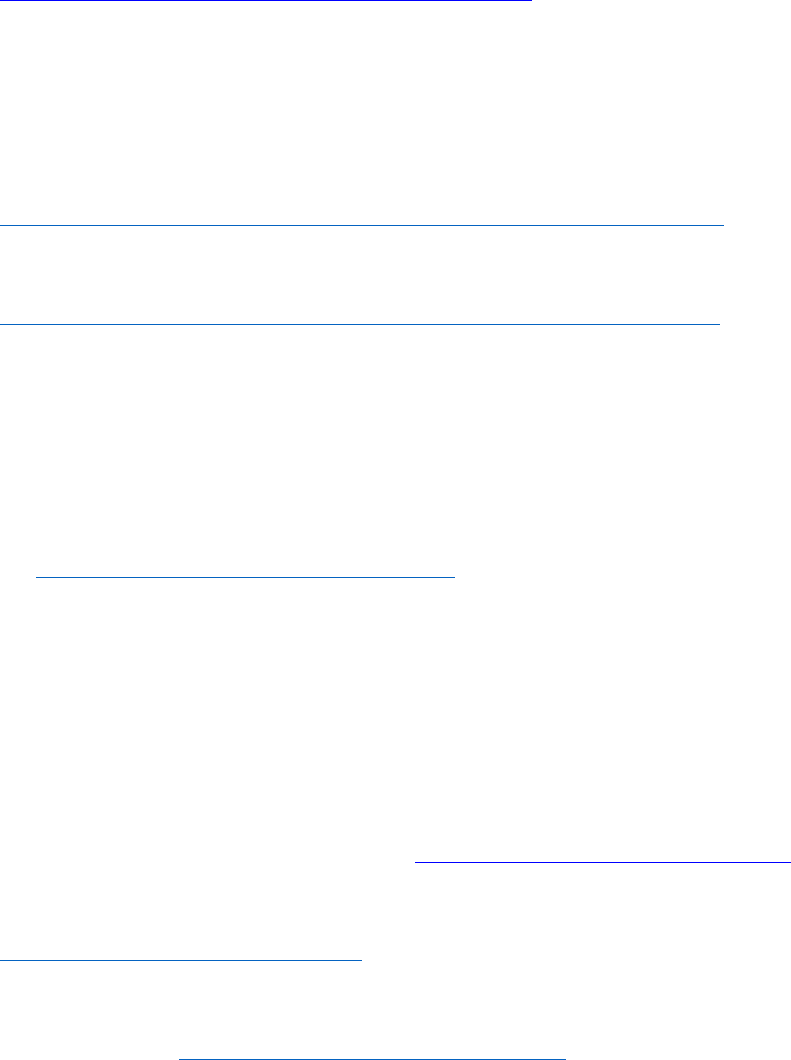

I assessed the inferior nasal aperture (INA), interorbital breadth (IOB), nasal aperture width

(NAW), nasal bone structure (NBS) (Figure 1), anterior nasal spine (ANS), and post-bregmatic

depression (PBD) (Figure 2.) In each assessment, I compared the size and shape of each

landmark to examples given in forensic anthropology lab manuals on a scale. A certain

topological configuration would earn the landmark a number on a scale and each number was

then assessed according to the OSSA chart. Each of these scores were then weighed to

extrapolate if the decedent was presumed to be either “American Black” or “American White.”

Each estimation gave me a number that was then scored according to the OSSA scaling

methodology that gave me an estimation of the ancestral heritage of samples.

Figure 1: Figure 1 depicts a front facing human cranial analog with visual indicators of OSSA locations:

interorbital breadth, nasal bone structure, nasal aperture width, inferior nasal aperture. Photo credit:

William Brown 2022

Figure 2: Figure 2 depicts a side facing human cranial analog with visual indicators of OSSA locations:

post bregmatic depression, anterior nasal spine. Photo credit: William Brown 2022

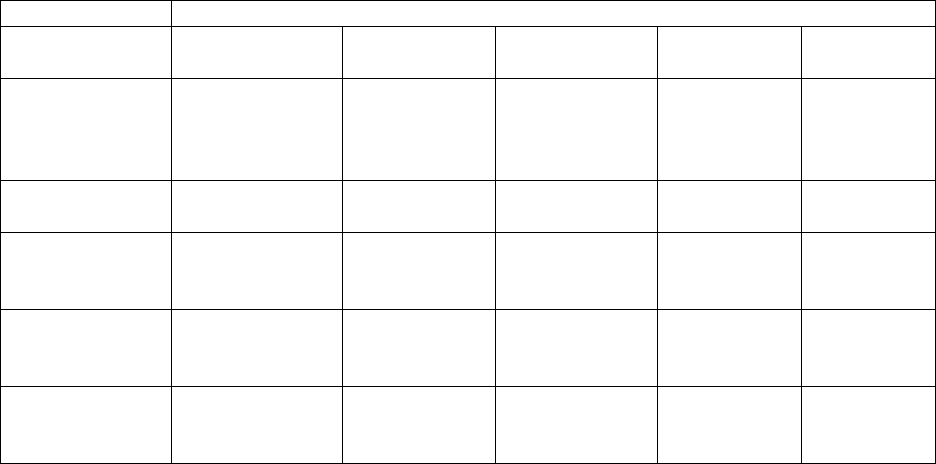

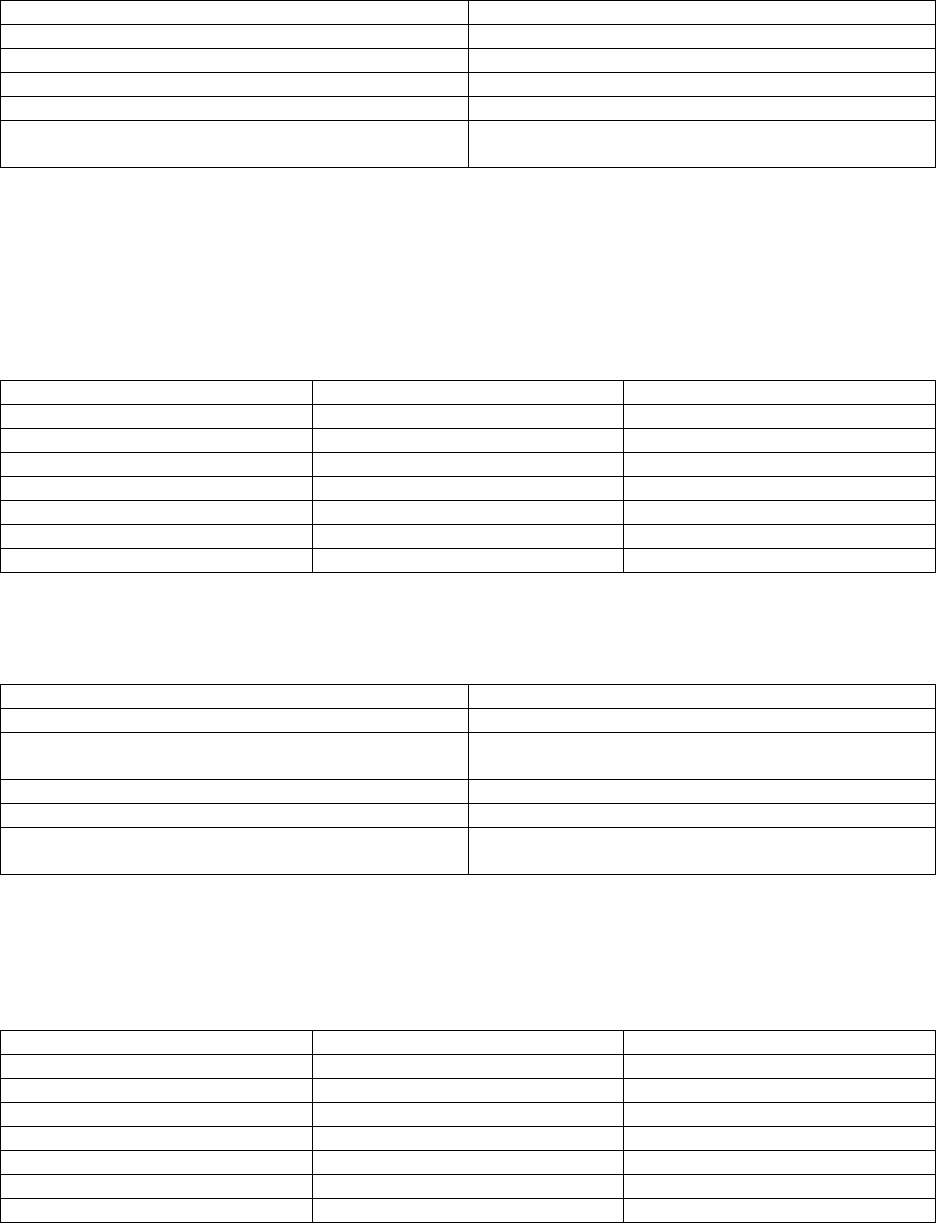

Binary Transformation of OSSA Scores:

Trait

Character expression and OSSA scores

Anterior nasal

spine (ANS)

Slight

1 =0

Intermediate

2=1

Marked

3=1

Inferior nasal

aperture (INA)

Pronounced

slope 1=0

Moderate

slope

2=0

Straight

3=0

Partial Sill

4=1

Sill

5=1

Interorbital

breadth (IOB)

Narrow

1=1

Intermediate

2=1

Wide

3=0

Nasal Aperture

width (NAW)

Narrow

1=1

Medium

2=1

Broad

3=0

Nasal Bone

Structure (NBS)

Low/Round

0=0

Oval

1=0

Marked

Plateau

2=1

Narrow

Plateau

3=1

Triangular

4=1

Post-Bregmatic

depression

(PBD)

Absent

0=1

Present

1=0

OSSA Sum of 0-3= “American Black” Sum of 4+= “American White”

Table 1: Table 1 depicts the OSSA binary transformation scoring method wherein a decedent’s ancestral

origin is estimated based on cranial topographical morphological features (Christensen and Passalacqua

2018, 127-36).

I recorded how long it took to do each of these assessments three times per sample, a standard

forensic protocol when performing such analysis. I also recorded how long it took to take

documentary photographs and follow lab safety protocols (Christensen and Passalacqua 2018,

127-36). In my analysis of the cranial human remains at the Portland State University human

osteology lab and the Portland Community College Sylvania biology lab, I was able to perform

the first steps in a macroscopic ancestral heritage estimation according to standard forensic

anthropology identification procedures. I am aware of the possibly problematic nature of

working in a post-colonial osteological collection of unknown proveniences in an institutional

setting, and I have taken special care to be respectful and conscientious of the human remains I

have examined at Portland State University and Portland Community College Sylvania campus

during this stage of my research. My comparison of the Bones methods and my assessment

methods are outlined in the data section of this study.

Data

Bones Episodes

The following information includes my observations of scenes depicting ancestral estimation in

Bones episodes. The ancestral heritage estimations are performed by a forensic anthropologist, a

forensic anthropology graduate student, and a forensic artist, with contributions from other

scientists depending upon the scene. I have analyzed the following three scenes from the ten

sample episodes I watched for this study, but I hope to examine more episodes in further depth in

future studies.

Example 1: Season 1 episode 1: Pilot

Scene at 14:35

*Team of scientists and an artist looking at 3D hologram in the Jeffersonian lab. *

Angela: “Brennan reassembled the skull and applied tissue markers.”

Dr. Brennan: “Her skull was badly damaged, but racial indicators, cheek bone dimensions, nasal

arch, occipital measurements, suggest African American.”

*Hologram populates*

Dr. Brennan: “Rerun the program substituting Caucasian values.”

*Hologram populates*

Dr. Brennan: “Split the difference. Mixed race.”

Angie: “Lenny Kravits or Vanessa Williams?”

The scene implies that some craniometric analysis may have been performed off camera, but

there is no way to determine which methods were performed (Hanson, Hart 2005). Zygomatic

(cheek) bones and the zygomatic suture placements are more similar in Caucasian and African

populations than dissimilar to other ancestral populations. There are multiple specific nasal

landmarks that can be used in determining a biological profile, but “nasal arch” is an unknown

and inaccurate term (Christensen, Passalacqua and Bartelink 2019, 271-304). “Occipital

measurements” implies that some type of craniometric analysis may have been performed off

screen, but there is no indication as to what methods were used.

Example 2: Season 6 Episode 6: The Shallow in the Deep

Scene at 3:40

*Scientists are working simultaneously in the Jeffersonian lab on bodies from a slave shipwreck

with many decedents. Skeletal remains from the shipwreck’s mass marine grave are being set on

examination tables. The forensic artist holds a slave ship’s manifesto that lists the names and

descriptions of possible decedents*

Dr. Brennan *Approaches examination table. Camera pans up the skeletal remains to show that

much of the craniofacial features are obscured by marine mussels*: “Male child under 10 years

old. One hundred and thirty centimeters. The marine mussels compromised the bone, *Points to

face* but the skull shows a mix of Negroid and Caucasoid characteristics suggesting he’d be

listed as Mulatto.”

Angela: “Got it. Polidore Nelson.”

Graduate student *At another examination table examining another decedent. Points to intact

pelvis*: “Symphyseal rim well defined. *Points to cranium* Partial ectocranial suture closure.

Female, 40’s, five feet tall.”

The scene implies that decedents from a recently discovered slave shipwreck, which housed a

mass marine grave, are being brought to the lab and assessed immediately after retrieval,

inferring that the viewer is witnessing the entire biological profile analysis process, without any

anthropometric measurements happening off screen (Kettner 2010). Contrary to what Bones

portrays in the case of Polidore Nelson, subadult skeletal remains are difficult to sex, and most

methods used on adults are not considered reliable on juveniles until after 14 years of age. One

method that is employed for sexing subadult skeletons with 81%-90% accuracy is metric

analysis of radiographs, which was not performed here. Determining ancestral origin in a

subadult decedent by visual assessment alone and without anthropometric evaluation may not be

a reliable method of determining ancestral heritage in subadult individuals, especially in admixed

populations (Christensen, Passalacqua and Bartelink 2019, 256-259).

The pubic symphysis is a good feature to examine for aging skeletal remains, however, the

graduate student in this scene estimated the age by expressing there is a well-defined rim, that

she couldn’t have seen in an intact pelvis (Brooks and Suchey 1990, 227-238). The ectocranial

suture isn’t used as an aging landmark in people under 50-60 years of age because the suture

does not fully close until approximately 80 years of age (Meindl and Lovejoy 1985, 57-66;

Ruengdit, Case, and Mahakkanukrauh 2020, 1-11). The biological profiles given in this scene are

determined by macroscopic assessments within moments of visual examination (Kettner 2010),

which would not be possible or procedurally acceptable in real life.

Example 3: Season 10 Episode 6: The Lost Love in the Foreign Land.

Scene at 2:28

*Forensic Pathologist, forensic entomologist, and forensic anthropologist are examining human

remains in a pasture. They approach a mostly fleshed, though skinless decedent. *

Dr. Brennan *Holds hand in a size gauging gesture near the decedent’s hip joint*: I’m judging

by the length of the hip axis the decedent was female of Mongoloid descent.”

Dr. Brennan *Moves hand to decedent’s mouth and runs gloved fingers over the mandibular

arcade*: “The wear on the mandibular teeth suggest she was in her late 20’s.”

Without defleshing the decedent and without using calipers for metric analysis, there is no

reasonable explanation for how Dr. Brennan can accurately gauge measurements of the hip axis

in millimeters. Dr. Brennan would be required after metric analysis to perform statistical analysis

using a database like Fordisc to come to an accurate ancestral estimation using hip axis metrics

(Meeusen, Christensen, and Hefner 2015, 1300-1304). The use of femoral neck axis length to

approximate sex in a forensic anthropological context is a method shown to be approximately

86% effective in determination when anthropometric measurements with slide calipers are used

on skeletal remains then compared to forensic discipline sex specific datasets. However, it is

considered limited due to significant intra-population variation in ancestral estimations and may

not be applied in a forensic anthropological context when other more valid skeletal landmarks

are available (Attia et al 2022; Meeusen, Christensen, and Hefner 2015, 1300-1304).

Although there are methods of determining the approximate age at death of a decedent from

tooth wear, these methods rely heavily upon visual inspection and may also include metric

analysis, neither of which Dr. Brennan performed (Alayan, Aldossary and Santini 2018, 18-21).

The validity of this method of determining approximate age at death is influenced by diet,

pathology, dental malocclusion, and other factors, and as such may not be used when other valid

methods are available (Miles 2001, 973-982).

At a crime scene, a forensic anthropologist may be present to help locate human remains,

determine if the skeletal remains are intact, identify and differentiate human skeletal remains

from animal remains, or to work in a mobile lab to process evidence. However, most of the

individuation of human remains happens in the lab after the bones have been cleaned and the

chain of custody observed per judicial procedures (Stanojevich 2016). Dr. Brennan would not

have been able to give expert witness testimony as to the biological profile of this decedent

ethically had she estimated age, sex, and ancestry in this manner (Christensen, Passalacqua and

Bartelink 2019, 256-259; Manthey and Jantz 2020, 275–87; Stanojevich 2016).

Cranial Assessment Data

Before I could analyze the crania using the OSSA method, I needed to take a number of steps to

gain permissions to access the bones through institutional authorities. I spent months emailing

and networking to get permissions. Once I had permission to use osteological collections, I also

spent time traveling, signing paperwork for the care and handling of the space, materials and

human remains, getting lab key permissions, setting out lab pads to protect the crania, and

washing hands before and after handling human remains. These preparatory steps preceded the

in-lab process of carefully handling the crania, photographing them from multiple angles, writing

down each observation, then doing it twice more on different days to recheck for accuracy. I

spent approximately 40 minutes assessing each cranium, including the time I spent taking notes.

In actual forensic lab situations, there are many factors that take time, including chain of custody

procedures, ongoing judicial processes, court permissions, cleaning the remains, and performing

multiple analysis techniques to get the most accurate and valid information for individuation as

possible (Stanojevich 2016). The Bones episodes I observed did not portray these steps and

protocols. Due to the OSSA method only allowing for a categorical approximation of ancestry of

either “American black” or “American white,” accuracy in my ancestral estimations will not be

entirely known. I did not perform biological profiles including age or sex because these factors

fall outside of the scope of this study. Further refinement of ancestral estimation could be

performed through methods such as craniometric measurements in concert with database

comparisons such as Fordisc. Fordisc is a database used by biological anthropologists to

statistically analyze human remains for biological profile approximations concerning ancestry,

sex and stature (Manthey and Jantz 2020, 275–87). The Decision Tree Modeling (DTM) method,

which uses the categorization information found from OSSA assessments to further narrow the

possible ancestral origins of decedents based on cranial features, could also be used to add one

further dimension to OSSA. However, I did not have access to these resources or sufficient

training in these techniques to make valid assessments using them at the time of this study.

In my assessments, I use the term “wormians” in place of “supernumerary sutural bones,” or

“extra numerary sutural ossifications,” which are bones that form because of extra ossification

centers along cranial suture lines in utero from a variety of causes (Pickett and Montes 2019).

The cranial data presented is in two designations. Crania with an “A” designation came from the

Portland State University osteology lab and are listed first, crania with a “P” designation came

from the Portland Community College-Sylvania biology lab and are listed second. There is no

particular order outside of these designations.

Cranium A54: Notes: Nasal aperture damaged, anterior nasal spine missing, inferior nasal

aperture damaged. Examination and documentation lasted 45 minutes.

OSSA Trait

OSSA Trait

Character/Score

OSSA Score

ANS

Inconclusive

-

INA

Inconclusive

-

IOB

2

1

NAW

2

1

NBS

4

1

PBD

Present

0

Sum

Incomplete assessment

undetermined

Table 2: Table 2 displays the morphological scores assessed from the cranium “A54” located in PSU’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

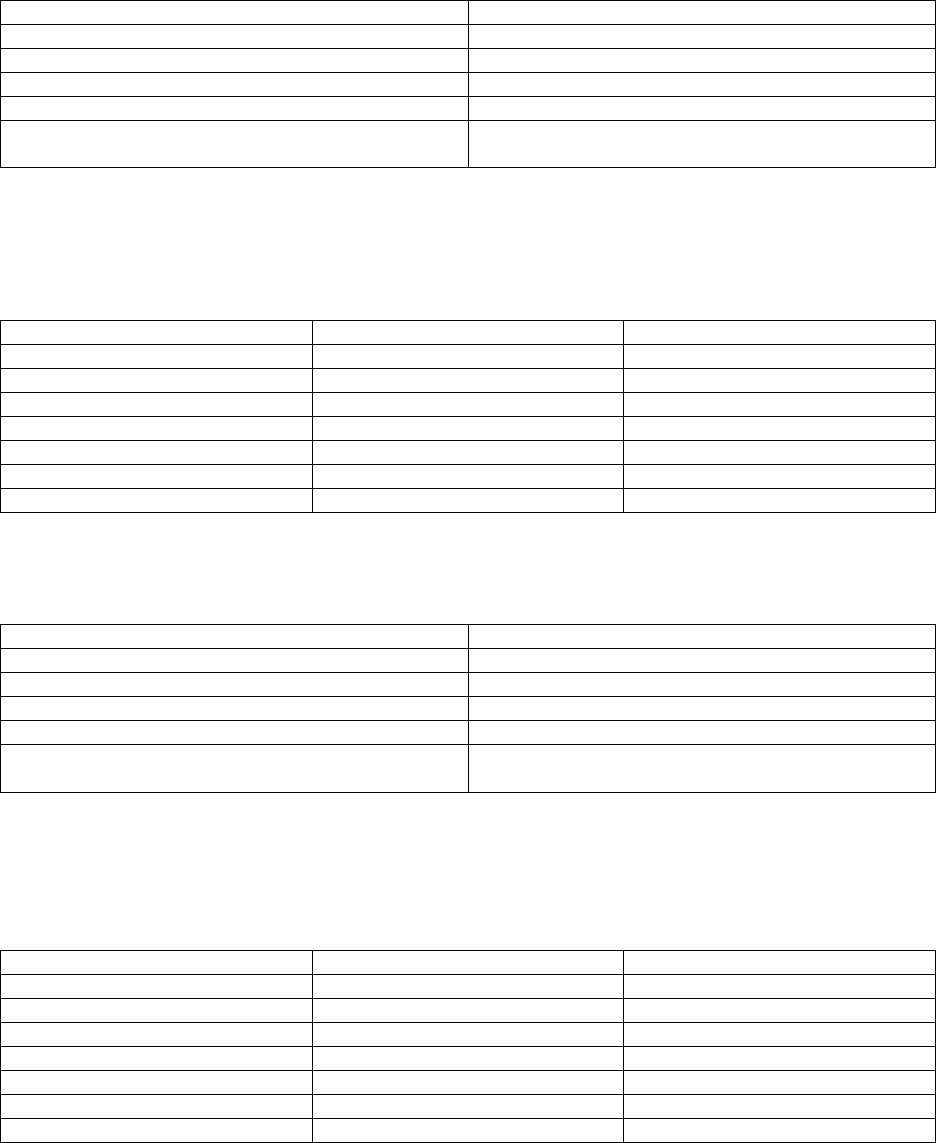

Visual macroscopic observations: Features absent or present:

Supraorbital ridge

absent

Extra occipital protuberance

robust

Extra sutural bones

absent

Mastoid process

present

Staining

Not significantly

Fractures

Left temporal bone fractured. Left zygomatic bone

fractured.

Table 3: Table 3 displays the morphological traits assessed from the cranium “A54” located in PSU’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Cranium A30: Notes: Incisors, bicuspids, and canines damaged. Presumed female with

masculinized features. Bone porosity possibly due to iron deficiency, wormians present.

Examination and documentation lasted 55 minutes.

OSSA Trait

Character/Score

OSSA Score

ANS

2

1

INA

4

1

IOB

1

1

NAW

2

1

NBS

1

1

PBD

Absent

0

Sum

10

5 Possible American “white”

Table 4: Table 4 displays the morphological scores assessed from the cranium “A30” located in PSU’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Visual macroscopic observations: Features absent or present:

Supraorbital ridge

slight

Extra occipital protuberance

absent

Extra sutural bones

wormians present but otherwise simple sutural

structure

Mastoid process

present, small

Staining

minimal

Fractures

Present, front dentition fractured, postmortem fractures

due to handling

Table 5: Table 5 displays the morphological traits assessed from the cranium “A30” located in PSU’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Cranium A43: Examination and documentation lasted 45 minutes.

OSSA Trait

Character/Score

OSSA Score

ANS

3

1

INA

3

0

IOB

2

1

NAW

2

1

NBS

1

0

PBD

Absent

0

Sum

11

3 Possible American “white”

Table 6: Table 6 displays the morphological scores assessed from the cranium “A43” located in PSU’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

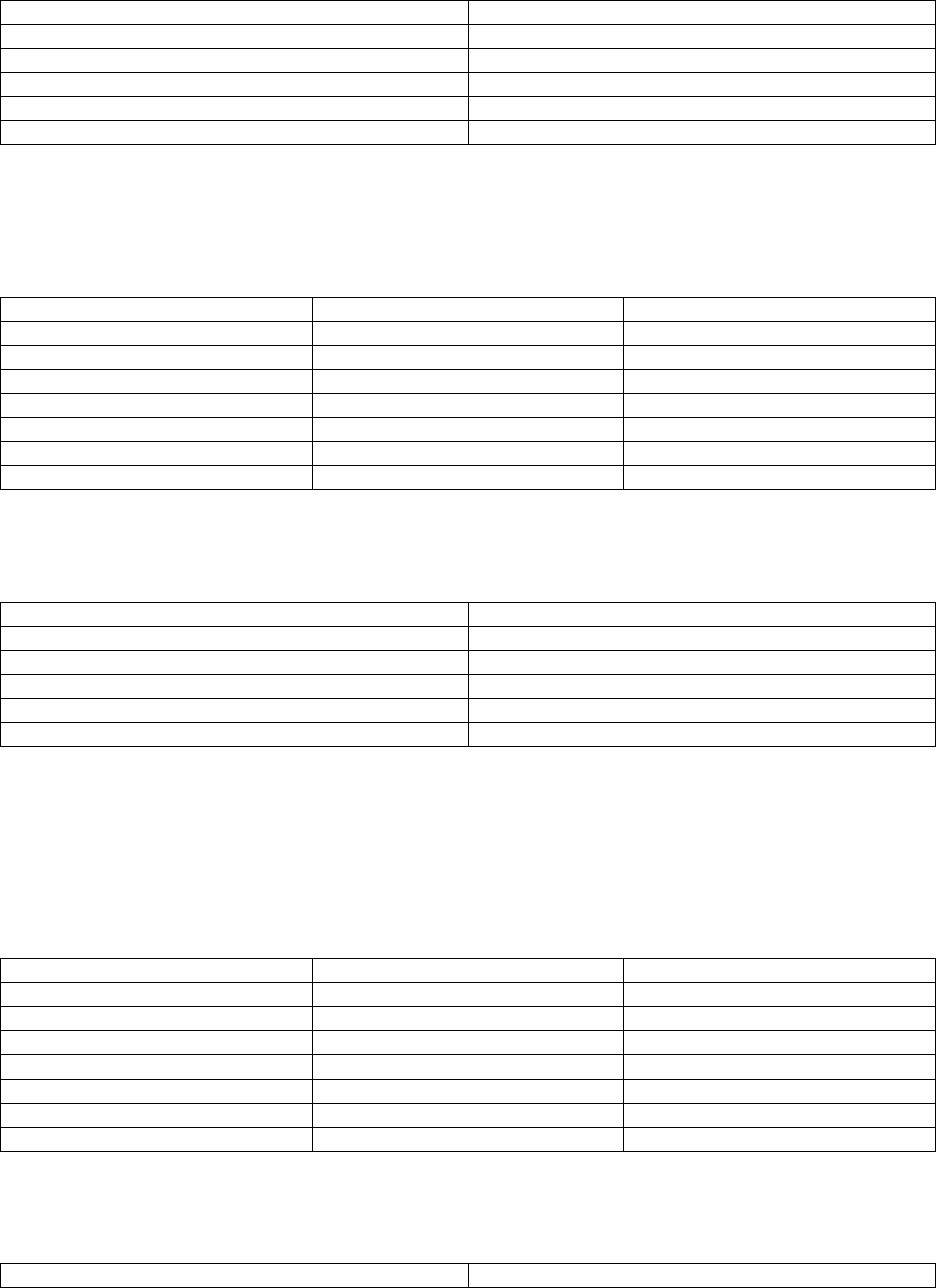

Visual macroscopic observations: Features absent or present:

Supraorbital ridge

minimal

Extra occipital protuberance

present

Extra sutural bones

present

Mastoid process

present, gracile

Staining

minimal

Fractures

left styloid process absent, teeth fractured, anterior

nasal spine fractured

Table 7: Table 7 displays the morphological traits assessed from the cranium “A43” located in PSU’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Cranium A50: Examination and documentation lasted 45 minutes.

OSSA Trait

Character/Score

OSSA Score

ANS

2

1

INA

2

0

IOB

3

0

NAW

3

0

NBS

0

0

PBD

Present

1

Sum

10

2- Possible American “black”

Table 8: Table 8 displays the morphological scores assessed from the cranium “A50” located in PSU’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Visual macroscopic observations: Features absent or present:

Supraorbital ridge

absent

Extra occipital protuberance

present

Extra sutural bones

wormians present

Mastoid process

Present, gracile

Staining

moderate

Fractures

Front dentition, mandibular angle broken off, multiple

postmortem fractures due to handling

Table 9: Table 9 displays the morphological traits assessed from the cranium “A50” located in PSU’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Cranium A63: Examination and documentation lasted 45 minutes.

OSSA Trait

Character/Score

OSSA Score

ANS

2

1

INA

2

0

IOB

2

1

NAW

2

1

NBS

0

0

PBD

Present

0

Sum

8

3 Possible American “black”

Table 10: Table 10 displays the morphological scores assessed from the cranium “A63” located in PSU’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Visual macroscopic observations: Features absent or present:

Supraorbital ridge

absent

Extra occipital protuberance

present

Extra sutural bones

wormians present

Mastoid process

present but slight

Staining

minimal

Fractures

maxilla dentition

Table 11: Table 11 displays the morphological traits assessed from the cranium “A63” as they apply to the

morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Cranium A52: Examination and documentation lasted 40 minutes.

OSSA Trait

Character/Score

OSSA Score

ANS

3

1

INA

5

1

IOB

1

1

NAW

1

1

NBS

4

1

PBD

Absent

1

Sum

14

6- Possible American “White”

Table 12: Table 12 displays the morphological scores assessed from the cranium “A52” located in PSU’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

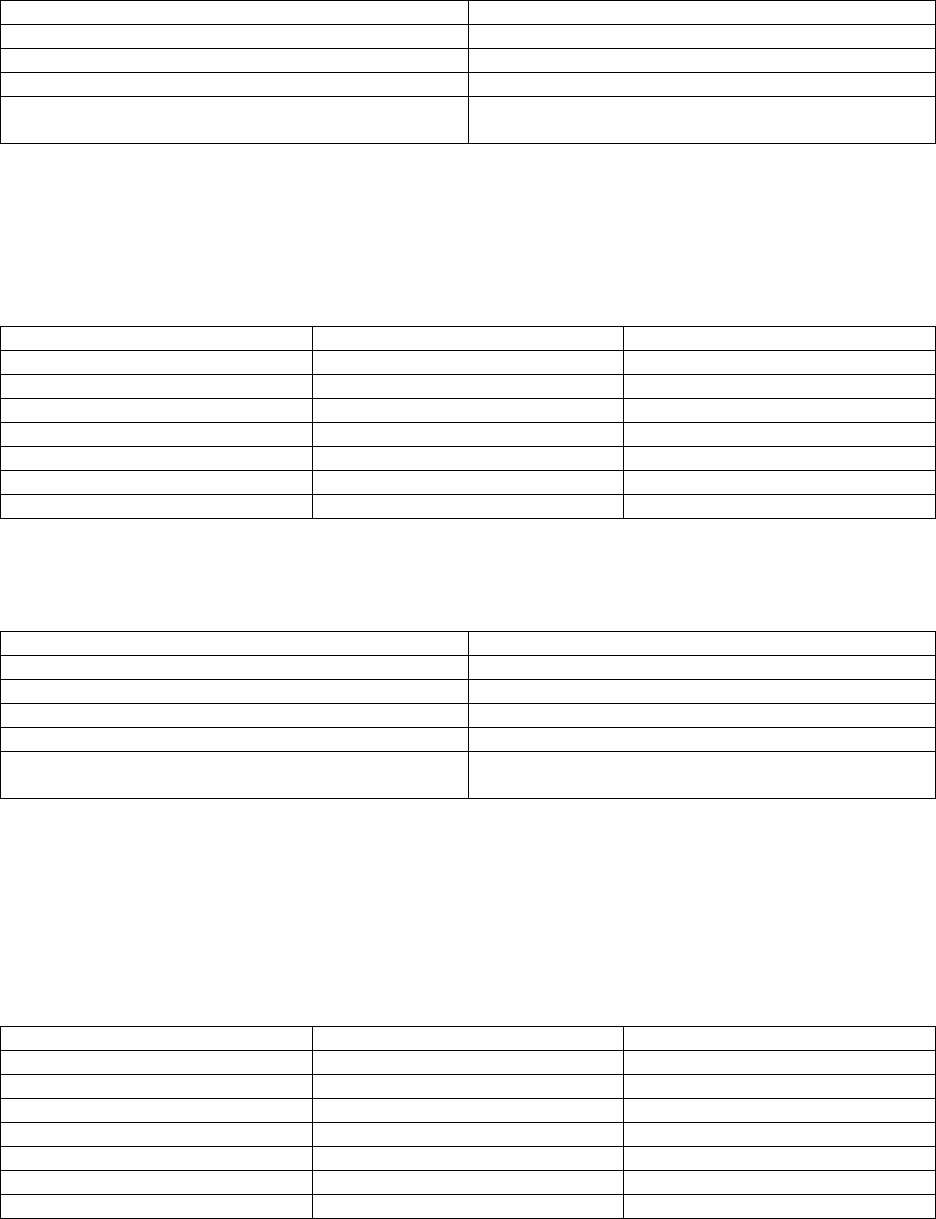

Visual macroscopic observations: Features absent or present:

Supraorbital ridge

absent

Extra occipital protuberance

present

Extra sutural bones

small wormian present

Mastoid process

present

Staining

absent

Fractures

absent

Table 13: Table 13 displays the morphological traits assessed from the cranium “A52” as they apply to the

morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Cranium P1: Notes: Cranium is partially covered in white paint, handling damage, elderly

individual, parietal foramina present, glabellar foramen present, multiple foramina in lateral

lesser wing of sphenoid bone. Examination and documentation lasted 50 minutes.

OSSA Trait

Character/Score

OSSA Score

ANS

2

1

INA

3

0

IOB

2

1

NAW

2

1

NBS

1

1

PBD

Present

0

Sum

9

4 Possible American “white”

Table 14: Table 14 displays the morphological scores assessed from the cranium “P1” located in PCC’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Visual macroscopic observations: Features absent or present:

Supraorbital ridge

minimal

Extra occipital protuberance

absent

Extra sutural bones

obliterated

Mastoid process

absent

Staining

absent

Fractures

Multiple postmortem fractures in many locations likely

due to handling

Table 15: Table 15 displays the morphological traits assessed from the cranium “P1” located in PCC’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Cranium P2: Notes: Nasal aperture damaged, maxillary teeth damaged, glue along coronal and

sagittal sutures. Examination and documentation lasted 40 minutes.

OSSA Trait

Character/Score

OSSA Score

ANS

2

1

INA

4

1

IOB

2

1

NAW

2

1

NBS

3

1

PBD

Absent

1

Sum

13

6 Possible American “white”

Table 16: Table 16 displays the morphological scores assessed from the cranium “P2” located in PCC’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Visual macroscopic observations: Features absent or present:

Supraorbital ridge

minimal

Extra occipital protuberance

present

Extra sutural bones

absent

Mastoid process

robust

Staining

absent

Fractures

Fractures to nasion and maxilla due to handling

postmortem

Table 17: Table 17 displays the morphological traits assessed from the cranium “P2” located in PCC’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Cranium P3:

Notes: Nasal aperture damaged, Maxillary and mandibular anterior dentition damaged, glue

along coronal suture, older individual. Examination and documentation lasted 40 minutes.

OSSA Trait

Character/Score

OSSA Score

ANS

3

1

INA

5

1

IOB

1

1

NAW

2

1

NBS

4

1

PBD

Absent

1

Sum

15

6 Possible American “white”

Table 18: Table 18 displays the morphological scores assessed from the cranium “P3” located in PCC’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Visual macroscopic observations: Features absent or present:

Supraorbital ridge

present

Extra occipital protuberance

present

Extra sutural bones

absent

Mastoid process

robust

Staining

absent

Fractures

Some due to handling postmortem

Table 19: Table 19 displays the morphological traits assessed from the cranium “P3” located in PCC’s osteology

collection as they apply to the morphoscopic OSSA ancestry estimation assessment.

Discussion

In my analysis of the scenes depicting the ancestral estimations in biological profiles on Bones, I

noticed that the estimations shown to the viewer were macromorphoscopic, meaning that the

fictional scientists took a large-scale look at the features of the skull without using metric

measurements. There was mention of craniometric analysis done in Example 1 when Dr.

Brennan mentions “occipital measurements,” but without mention of a specific testing

procedure, there is no way to know which method was utilized (Hanson and Hart 2005). This

means that the viewer is only shown subjective, typological, macroscopic cranial analysis for

ancestral heritage estimation in these examples. Without the craniometric analysis of a decedent

compared to a statistical dataset like Fordisc, the forensic anthropologist doing ancestral

estimation may run the risk of providing an inaccurate biological profile based on confirmation

bias while working from a list of typological macroscopic traits (Christensen, Passalacqua, and

Bartelink 2019, 274-277; Nakhaeizadeh, Dror, and Morgan 2014, 208–14).

As I based my cranial analysis methodology on what I was able to see in the episodes I sampled,

I used the OSSA method which is limited to a binary choice for ancestral estimation, i.e.,

“American Black,” or “American White.” The DTM method that works with the OSSA method

would have added “Hispanic” to the list of possible ancestral origins had I used it, however,

these three categories do not give a clear biological profile to most decedents and are based on

cultural and social ideas about race rather than clinal realities (Christensen, Passalacqua, and

Bartelink 2019, 274-277).

Although a discussion of skeletal and dental variation that occurs within and between

populations is beyond the scope of this paper, there are superficial morphologic features that

vary in shape and size observed in craniofacial and postcranial remains across populations. These

skeletal and dental features have traditionally been assessed using topographical methods to

assign race to skeletonized remains (White, Black and Folkens 2012, 379-426). However, race is

a social construct and ancestry represents relatedness, thus race and ancestry are not the same

thing. When the global distribution of human variation is considered, a gradual shift over

geographic space in trait prevalence or phenotype is best explained through clines (Christensen

and Passalacqua 2018, 127-30). Due to population histories, cultural factors, migration, and an

increase in global travel, populations that were once disparate are now in contact, which renders

datasets describing or characterizing skeletal or dental variation by population antiquated and

inaccurate (Christensen and Passalacqua 2018, 127-30; Christensen, Passalacqua and Bartelink

2019, 274-277, White, Black and Folkens 2012, 379-426).

My estimations for the 9 crania I examined were 1 undetermined, 2 possible “American black,”

and 6 possible “American white” according to the OSSA method which took me approximately

45 minutes per cranium to assess (Christensen, Passalacqua and Bartelink 2019, 274-277). Bones

had a 100% individuation accuracy rate instantaneously in the episodes I observed in this study.

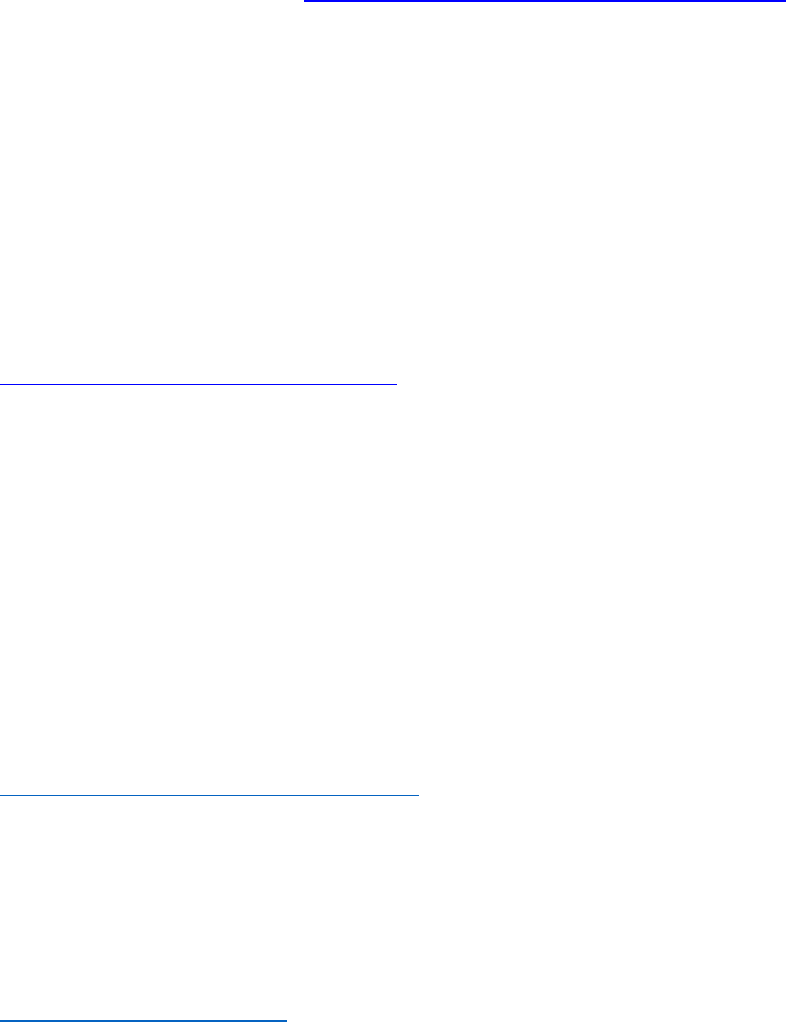

Conclusion

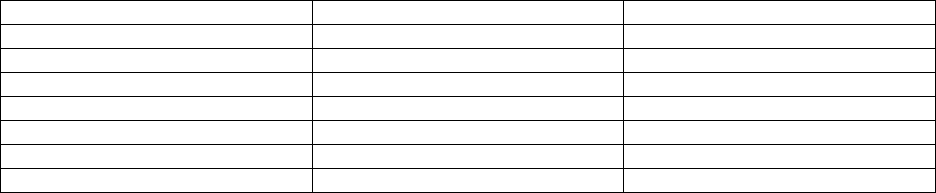

Comparative analysis of data:

Item

Bones

Me

Who performed analysis

Forensic anthropologist,

graduate students

Novice Graduate student

Method used in analysis

sample

Undefined

macromorphoscopic methods

Macromorphoscopic OSSA

method

Time to perform analysis

Instantaneous – Apx. 3

minutes

Apx. 40 minutes per each

sample

Outcome: Ancestral

estimation

Simple, without error,

immediate.

Complicated, many

overlapping features due to

admixture, cranial damage,

and typical human variation.

Unable to accurately

determine ancestral heritage.

Table 20: Table 20 compares the methods viewed in the samples of Bones against real life lab methods to

compare time to perform and accuracy of ancestral estimation using macromorphoscopic procedures.

A forensic anthropologist is a specialist in a discipline that requires as accurate a biological

profile as possible for judicial and ethical concerns. Law enforcement in the United States relies

on accurate and valid decedent individuation, including socially relevant ancestral heritage

estimation due to culturally influenced reporting and procedure advancement (Dirkmaat et al.

2008, 33-52). Accurate ancestral heritage estimations allow law enforcement to better investigate

missing persons. Due to the inaccuracy of the testing method I applied, based on the samples of

Bones I observed, I would not be able to make precise or accurate ancestry estimations on any of

the crania I analyzed in a judicial or professional context (Christensen, Passalacqua, and

Bartelink 2019, 274-277; Manthey and Jantz 2020, 275–87).

I have observed that Bones may have streamlined forensic procedures, possibly excluding

depictions of necessary paperwork, with time for procedures. In addition, Bones makes a

protagonist fill several roles, such as crime scene investigator, forensic pathologist, and homicide

detective. This kind of blending of roles in TV and film media may mislead the general public

about these specialized professions (Christensen, Passalacqua, Bartelink 2019, 3-22; Kruse 2010,

79-91; Scheufele and Krause 2019).

I have found that Bones presents forensic science that uses jargon and represents reality closely

enough that it may be believable for the lay audience, but that might leave out enough detail that

it may be misleading concerning ancestral estimation without contextual science literacy. The

fictional forensic scientists in my samples appear to be able to neatly categorize a victim into a

“race” while possibly using methods that may fall outside of forensic anthropology standards

(Christensen, Passalacqua, and Bartelink 2019, 274-277; Kruse 2010, 79-91).

For over a hundred years, film has been influencing public perceptions of everything from

politics, to consumer brand identity, to gender expression, to “race” (Snow 2003, 22). In the case

of Bones and shows like it, if a fictional forensic anthropologist can visually inspect human

remains and instantly recognize the ancestral heritage of an individual, it may tell the viewer that

there are such intrinsic and substantial biological differences in human ancestral groups that a

trained specialist would easily be able to classify the victim into culturally recognized racial

categories. In reality, there is a process of assessment that allows an expert to make an estimation

of ancestral heritage. These biological profile techniques do not account for cultural identity,

complexion, ethnicity, personal expression, or several other variables, but are important factors

in individuating a decedent for identification purposes. (Christensen, Passalacqua and Bartelink

2019, 271-304; Kruse 2010, 79-91).

This research is significant because it operates in a multi-disciplinary way that invokes both

cultural and biological anthropology and may contribute a broader socio-cultural and biological

understanding regarding where the general public may be influenced in their conceptualizations

about the biological nature of race. This is important during our moment of national self-

examination regarding racialism and racism (Dirkmaat et al. 2008, 33-52; Kondo 2018, 25-34;

Jensen and Oster 2009, 1057–94).

This preliminary research serves as an exploratory study and will provide the basepoint in future

research projects and studies using a similar framework to examine implications concerning the

dominant cultural ideologies surrounding popular media depictions of marginalized

demographics and their portrayal in medical and biological science situations, e.g., disabled,

impaired, ethnic and ancestral minority, LGBTQ+, and elderly populations (Ellingsen and

Hernæs 2018; Kondo 2018, 25-34; Jensen and Oster 2009, 1057–94; National Center for Health

Statistics 2015).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Portland State University and Portland Community College-Sylvania for

this opportunity. My prodigious and patient mentors Dr. Michele Gamburd and Dr. Amiee Potter

who worked in concert to guide me through every step of this research and paper. The

anthropology Dept. Chair Dr. Charles Klein, Dr. Natalie Vasey, and Dr. Andrew Chang for their

understanding and support. The McNair program, Dr. Toeutu Faaleava, Motutama Sipelii,

Malissa Pierce, Dr. Julia Dancis, and my fellow McNair scholars for their guidance, kindness,

and encouragement. My magnificent friends and my phenomenal partner for daily

encouragement, strength and equanimity, and lastly to the incomparable Lord Vexington for his

daily reminders stay curious. You all have my absolute and abiding gratitude!

Bibliography

Alduraywish et al. 2022. “Sources of Health Information and Their Impacts on Medical

Knowledge Perception among the Saudi Arabian Population: Cross-Sectional Study.”

Journal of Medical Internet Research. JMIR Publications Inc.: Toronto, Canada

https://www.jmir.org/2020/3/e14414/.

Alayan I, Aldossary MS, Santini A. 2018. Validation of the efficacy of age assessment by the

Brothwell tooth wear chart, using skulls of known age at death. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2018

Jan-Apr;10 (1):18-21. doi: 10.4103/jfo.jfds_15_17. PMID: 30122864; PMCID:

PMC6080168.

Attia, MennattAllah Hassan, Mohamed Hassan Attia, Yasmin Tarek Farghaly,

Bassam Ahmed El-Sayed Abulnoor, Sotiris K. Manolis, Ruma Purkait & Douglas H.

Ubelaker. 2022. Purkait triangle revisited: role in sex and ancestry estimation, Forensic

Sciences Research,

DOI: 10.1080/20961790.2021.1963396

Bernard, Russell. H. 2011. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative

Approaches. Fifth Edition. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

Wikipedia. September 6, 2022. “Bones (TV Series).” Wikimedia Foundation,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bones_(TV_series).

Byers, Steven N. 2018. Introduction to Forensic Anthropology. Fifth Edition, 131-50. Upper

Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Brooks, S and J.M. Suchey. 1990. “Skeletal age determination based on the os pubis: a

comparison of the Acsádi-Nemeskéri and Suchey-Brooks methods.” Human Evolution,

5(3): 227-238.

Chou, Vivian. 2017. How Science and Genetics are Reshaping the Race Debate of the 21

st

Century. Harvard University, The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2017/science-genetics-reshaping-race-debate-21st-

century/

Christensen, Angi, Passalacqua. 2018. A Laboratory Manual for Forensic Anthropology. 35-41,

101-09, 127-130. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Christensen, Angi M., Nicholas V. Passalacqua, and Eric J. Bartelink. 2019. Forensic

Anthropology: Current Methods and Practice, 1–22, 256-259, 274-277, 271-304, 369-

405. London: Academic Press - an imprint of Elsevier

DiGangi, Elizabeth, and Johnathan Bethard. January 18, 2021. “Uncloaking a Lost Cause:

Decolonizing Ancestry Estimation in the United States” Wiley Online Library. American

Journal of Physical Anthropology. 311-509

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajpa.24212.

Dirkmaat, Dennis C., Luis L. Cabo, Stephen D. Ousley, and Steven A. Symes. 2008. “New

Perspectives in Forensic Anthropology.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology

137, no. S47: 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20948.

Ellingsen, S., Hernæs, Ø. 2018. The impact of commercial television on turnout and public

policy: Evidence from Norwegian local politics. Journal of Public Economics.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0047272718300215

Flatow, Reichs. 2012. “Meet the brains behind “bones.” NPR. August 31, 2012.

https://www.npr.org/2012/08/31/160391684/meet-the-brains-behind-bones

Foster, M.W., Sharp, R.R. 2022. “Race, ethnicity, and genomics: social classifications as

proxies of biological heterogeneity.” Genome Res. 12, 844–850

Fujimura, Joan H., Deborah A. Bolnick, Ramya Rajagopalan, Jay S. Kaufman, Richard C.

Lewontin, Troy Duster, Pilar Ossorio, and Jonathan Marks. 2014. “Clines Without

Classes: How to Make Sense of Human Variation.” Sociological Theory 32, no. 3 208–

27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275114551611.

Gerbner, George; Gross, L. 1976. “Living with Television: The Violence Profile.” Journal of

Communication. 26 (2): 173–199

Hall, Stuart. 2011. “The Whites of Their Eyes.” Essay. In Gender, Race and Class in Media a

Text-Reader, edited by Gail Dines and Jean M. Humez, 81–84. Sage Publications

Hanson, Hart. “Pilot.” Episode. Bones 1, no. 1. New York, New York: Fox, September 13,

2005.

IMDb. September 13, 2005. “Bones.” IMDb.com, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0460627/.

Jensen, Robert, and Emily Oster. 2009.“The Power of TV: Cable Television and Women’s

Status in India.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124, no. 3: 1057–94.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40506252.

Jorde, L. B., Wooding, S. P. 2004. “Genetic variation, classification and 'race'.” Nature News.

October 26, 2004. https://www.nature.com/articles/ng1435

Kettner, Karla. December 11, 2010. “The Shallow in the Deep.” Episode. Bones 6, no. 6. New

York, New York: Fox,

Kondo, Dorinne K. 2018. Worldmaking: Race, Performance, and the Work of Creativity.

Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 25-34

Kruse, C. 2010. Producing Absolute Truth: CSI Science as Wishful Thinking. American

Anthropologist, 112(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2009.01198.x

Lawson, Tamara F., 2009. “Before the Verdict and Beyond the Verdict: The CSI Infection

Within Modern Criminal Jury Trials” (PDF) Loyola University Chicago Law Journal. 41:

132-142

Manthey, Laura, and Richard L. Jantz. “Fordisc: Anthropological Software for Estimation of

Ancestry, Sex, Time Period, and Stature.” Statistics and Probability in Forensic

Anthropology, 2020, 275–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-815764-0.00022-8.

Meeusen, R.A., Christensen, A.M. and Hefner, J.T. 2015. The Use of Femoral Neck Axis Length

to Estimate Sex and Ancestry. J Forensic Sci, 60: 1300-1304.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12820

Meindl, Richard S. and C. Owen Lovejoy. 1985. “Ectocranial Suture Closure: A Revised

Method for the Determination of Skeletal Age at Death Based on the Lateral-Anterior

Sutures.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 68(1): 57-66.

Miles. 2001. The Miles Method of Assessing Age from Tooth Wear Revisited, Journal of

Archaeological Science, Volume 28, Issue 9, Pages 973-982, ISSN 0305-

4403,https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2000.0652

Müller-Wille S., 2014. Race and History: Comments from an Epistemological Point of View.

Science, technology & human values, 39(4), 597–606.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243913517759

Nakhaeizadeh, Sherry, Itiel E. Dror, and Ruth M. Morgan. “Cognitive Bias in Forensic

Anthropology: Visual Assessment of Skeletal Remains Is Susceptible to Confirmation

Bias.” Science & Justice 54, no. 3 (2014): 208–14.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scijus.2013.11.003.

National Academies of Sciences. 1996. "2 Principles and Definitions." National Science

Education Standards. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, page 22.

https://doi.org/10.17226/4962.

National Center for Health Statistics (US). 2015. Health, United States, 2015: With Special

Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for

Health Statistics (US); 2016 May. Report No.: 2016-1232.

Pickett, Arthur T, and M. Alisha Montes. 2019. “Wormian Bone in the Anterior Fontanelle of an

Otherwise Well Neonate.” Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4741.

Ruengdit, Sittiporn, D. Troy Case, and Pasuk Mahakkanukrauh. 2020. “Cranial suture closure

as an age indicator: A review.” Forensic Science International, 307 (110111): 1-11.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.110111.

Ruddock. 2006. Understanding audiences: Theory and method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications.

Salmon, Daniel A., Matthew Z. Dudley, Jason M. Glanz, and Saad B. Omer. 2015. “Vaccine

Hesitancy: Causes, Consequences, and a Call to Action.” ScienceDirect. Elsevier.

November 25, 2015.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X15013110.

Scheufele, Krause. 2019. “Science Audiences, Misinformation, and Fake News.” Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. U.S. National Library

of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30642953/.

Siebers, Tobin. 2019. “Returning to the Social Model.” Essay. In The Matter of Disability:

Materiality, Biopolitics, Crip Affect, edited by David T. Mitchell, Susan Antebi, and

Sharon L. Snyder, 39–47. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press

Shelton, Donald E; Kim, Young S; Barak, Gregg. 2009. “An Indirect-Effects Model of Mediated

Adjudication: The CSI Myth, The Tech Effect, and Metropolitan Jurors’ Expectations for

Scientific Evidence” (PDF). Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law.

Smith, Steven M., Stinson Veronica, Patry, Marc W. 2011."Fact or Fiction? The

Myth and Reality of the CSI Effect" Court Review: The Journal of the American

Judges Association. 355. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ajacourtreview/355

Snow, Nancy. 2003. Information War: American Propaganda, Free Speech and Opinion Control

Since 9-11. New York: Seven Stories Press. pp. 22. ISBN 978-1-58322-557-8.

Soylu Yalcinkaya, Nur, Sara Estrada-Villalta, and Glenn Adams. 2018. “The (Biological or

Cultural) Essence of Essentialism: Implications for Policy Support among Dominant and

Subordinated Groups.” Frontiers in Psychology 8.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00900.

Spalding, Katie. 2021. “The Dunning-Kruger Effect: How Does It Affect Us, and Does It Even

Exist?” IFLScience. July 12, 2021. https://www.iflscience.com/brain/the-dunningkruger-

effect-how-does-it-affect-us-and-does-it-even-exist/.

Stanojevich, Vanessa. 2016. “The Role of a Forensic Anthropologist in a Death Investigation.”

Journal of Forensic Research 03, no. 06 https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7145.1000154.

Taylor, Natalie Greene, Jaeger Paul. 2022. Foundations of Information Literacy. Chicago, ALA

Neal-Schuman 31-36, 39-40, 131-135

University of Nebraska Medical Center. 2022. “Molecular Forensics.” “Molecular Forensics.”

https://www.unmc.edu/pathology/clinical/clinical-pathology/molecular-forensics.html.

Webster, James G., Ksiazek, Thomas B. 2012. “The Dynamics of Audience Fragmentation:

Public Attention in an Age of Digital Media.” Journal of Communication. 62: 39–56.

White, Black, Folkens. 2012. “Assessment of Age, Sex, Stature, Ancestry, and Identity of the

Individual” In, Human Osteology. Third Edition. Boston: Elsevier, Academic Press.

Yosso, Tara J. 2020. “Critical Race Media Literacy for These Urgent Times.” International

Journal of Multicultural Education 22 (2):5-13.

https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v22i2.2685;

Zarocostas, John. 2020. “How to Fight an Infodemic.” The Lancet 395 (10225): 676. Elsevier

Ltd. February 29, 2020.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014067362030461X.