Teacher Shortages and

Turnover in Rural

Schools in the US: An

Organizational Analysis

†

Richard M. Ingersoll

1

and Henry Tran

2

Abstract

Purpose: The objective of this study is to provide an overall national por-

trait of elementary and secondary teacher shortages and teacher turnover in

rural schools, comparing rural schools to suburban and urban schools. This

study utilizes an organizational theoretical perspective focusing on the role

of school organization and leadership in the causes of, and solutions to,

teacher shortages and staffing problems. Data/Methods: The study entailed

secondary statistical analyses of the nationally representative Schools and

Staffing Survey, its successor the National Teacher Principal Survey, and

their supplement the Teacher Follow-Up Survey, conducted by the

National Center for Education Statistics. Findings: The analyses document

that, contrast to urban and suburban schools, the student population and

teaching force in rural schools has dramatically shrunk in recent decades,

that despite this decrease in students, and demand for teachers, rural

schools have faced serious difficulties filling their teaching positions, and

1

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

2

University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA

†

Versions of this paper were presented at the Developing Leadership Capacity for Equitable

Rural Educator Recruitment and Retention Seminar, University of South Carolina, Columbia

(October 23–24, 2019) and the American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting

(April, 2023).

Corresponding Author:

Richard M. Ingersoll, University of Pennsylvania, 3700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Email: [email protected]

Original Research Article

Educational Administration Quarterly

1–36

© The Author(s) 2023

Article reuse guidelines:

sagepub.com/journals-permissions

DOI: 10.1177/0013161X231159922

journals.sagepub.com/home/eaq

that these teacher staffing problems are driven by high levels of preretire-

ment teacher turnover. Moreover, the data document that teacher turnover

varies greatly between different kinds of schools, is especially high in high-

poverty rural schools, and is closely tied to the organizational characteristics

and working conditions of rural schools. Implications: Research and

reform on teacher shortages and turnover have focused on urban environ-

ments because of an assumption that schools in those settings suffer from

the most serious staffing problems. This study shows that teacher shortages

and teacher turnover in rural schools, while relatively neglected, have been

as significant a problem as in other schools.

Keywords

rural schools, teacher turnover, teacher supply, demand and shortages,

school leadership, teachers’ working conditions

Introduction

Few educational problems have received more attention in recent decades

than the failure to ensure that elementary and secondary classrooms are all

staffed with qualified teachers due to perennial teacher shortages. It has

been long and widely held that teacher staffing problems

1

and shortages are

primarily due to an insufficient supply of new teachers in the face of two

large-scale demographic trends— increasing student enrollments and increas-

ing teacher retirements due to an aging of the teaching force—and that

these staffing problems have resulted in lower school performance (see,

e.g., American Federation of Teachers, 2022; García & Weiss, 2019;

Government Accountability Office, 2022; National Academy of Sciences,

1987, 2007; National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983;

National Commission on Mathematics and Science Teaching for the twenty-

first Century, 2000; National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future,

1996, 1997; National Rese arch Council, 2002; President’s Council of

Advisors on Science and Technology, 2010; U.S. Department of

Education, 2009.

The prevailing policy response to these school staffing problems has pri-

marily focused on increasing the supply of new teachers (e.g., Allen et al.,

2023; Fowler, 2003, 2008; Greene, 2019; Hirsch et al., 2001; Liu et al.,

2004; Liu et al., 2008; Randazzo, 2022; Rice et al., 2008; Theobald, 1990).

Over the decades, a wide range of initiatives have been implemented to

recruit new candidates into teaching. Among these are midcareer-change pro-

grams; alternative certification programs designed to expedite entry; overseas

2 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

teacher recruiting initiatives; and financial incentives, such as scholarships,

signing bonuses and student loan forgiveness. An example of this genre of

reform was President Obama’s “100k in 10” program initiated in 2010 to

recruit 100,000 new STEM teachers by 2020. Some of these initiatives

entail a “lowering of the bar and widening of the gate” to fill openings, result-

ing in higher levels of underqualified teachers, and some don’t. But, regard-

less of their differences, underlying this wide variety of initiatives is a

common assumption—that school staffing problems are due to an insufficient

supply of new teachers and hence the best solution is to increase the supply of

new teachers.

The Importance of Teacher Turnover

More recently, research and reform on teacher shortages has begun to recog-

nize the role of preretirement teacher turnover in teacher staffing problems.

Beginning over two decades ago we empirically documented that teacher short-

ages are not solely a consequence of producing too few new teachers, but also a

result of too many existing teachers departing long before retirement, which in

turn is largely driven by school organizational conditions. And hence the sol-

ution to shortages, suggested by the data, does not solely lie in recruiting more

new teachers, but also in improving the retention of existing teachers through

improvements in schools as workplaces (Ingersoll, 1997, 2001; Ingersoll &

May, 2012; Ingersoll & Perda, 2010; Ingersoll et al., 2019, 2022). A number

of studies have since provided support for this thesis that teacher turnover is

a leading factor behind teacher shortages (e.g., Behrstock, 2009; Simon &

Johnson, 2015; Sutcher et al., 2016; Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond,

2017, 2019; García & Weiss, 2020). The objective of this study is to extend

and utilize this perspective in an examination of teacher shortages and turnover

in rural schools.

Research on the many facets of teache r turnover—its determinants, levels, var-

iations and consequences—has seen a dramatic growth in recent decades (for

reviews, see Borman & Dowling, 2008; Guarino et al., 2006; Johnson et al.,

2005; Nguyen et al., 2020). Turnover can be beneficial for students in cases

where the departing teachers are ineffective or low performing and the entrance

of “new blood” into faculties can enhance innovation and student learning

(Grissom & Bartanen, 2019; Ingersoll, 2001; Ingersoll & May, 2012). On the

other hand, a growing number of studies have shown that turnover in teaching

can incur substantial financial costs (e.g., Alliance for Excellent Education,

2005; Barnes et al., 2007; Milanowski & Odden, 2007; Synar & Maiden, 2012;

Texas Center for Educational Research, 2000; Villar & Strong, 2007;

Watlington et al., 2010) and can have a negative impact on faculty quality,

Ingersoll and Tran 3

student achievement and school performance (e.g., Boyd et al., 2007; Clotfelter

et al., 2006; Henry & Redding, 2018; Keesler, 2010; Krieg, 2004 Levy et al.,

2010; Merrill, 2014; Ronfeldt et al., 2013; Smylie & Wenzel, 2003; Sorensen

& Ladd, 2020). Along with his research, there has also been a growing recognition

in the realm of educational policy and reform that teacher turno ver is a serious

national problem that ne eds to be addressed (Alliance for Excellent Educa tion,

2005; American Federation of Teachers, 2022; Aragon, 2016; García & We iss,

2019; National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future, 2003).

Research on Teacher Shortages and Turnover in Rural Schools

Researchers have also long held that both teacher shortages and teacher turnover

problems affect some types of schools and communities more than others. Much

of the existing research and reform has tended to focus on urban environments

because of an assumption that schools in those settings suffer from the most

serious staffing problems—especially in comparison to suburban schools

(e.g., García & Weiss, 2019; Liu et al., 2008; Quartz et al., 2008; Simon &

Johnson, 2015). In contrast, there has been far less recognition of teacher short-

ages and teacher retention challenges facing schools in rural communities.

Indeed, a number of researchers and reformers have argued that this important

and significant segment of the population of schools, students and teachers has

been relatively neglected (e.g., Lavalley, 2018; Pendola & Fuller, 2018;

Schaefer et al., 2016), and that rural education exemplifies a case of “spatial

injustice,” where inequities and deficits in key resources, such as adequate

teacher staffing, are deeply rooted in geography (Tieken, 2017).

To be sure, there have been a small but growing number of empirical

studies that have insightfully identified the particular challenges and deficits

common to rural schools that impact their ability to ensure adequate

teacher staffing and teacher retention. These include: lower salaries due to a

smaller tax base; unsafe and inadequate facilities; fewer classroom and ped-

agogical resources; more out-of-field and cross-grade teaching because of

smaller faculty sizes; less separation between personal and professional life

resulting in limited privacy; fewer job opportunities for family or significant

others; enhanced responsibility for overall caretaking of students; profes-

sional and psychological isolation due to distance from professional commu-

nities and other education institutions; as well as fewer amenities, such as

retail services and recreational activities; (for reviews, see McClure &

Reeves, 2004; Tran et al., 2020; Tran & Dou, 2019).

Researchers have also identified a particular characteristic of rural schools that

can positively impact teacher staffing and retention—the strength of community

ties. Teachers often stay in rural schools primarily on the strength of relationships,

4 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

including those with students, colleagues and administrators, as well as commu-

nity members. Because of the smaller size of most rural schools, strong bonds

often form between teachers and their colleagues and students, that result in life-

long relationships. Rural teachers’ efficacy and impact on their students can be

more visible because of the smaller community. Teachers see their students

after they graduate and become adults who work and grow their own families

in the local community (e.g., Eppley, 2015; Seelig & McCabe, 2021). These attri-

butes can be used as place -based tea cher recruitment and retention tools (Tran

et al., 2020), and research has suggested some potential success with this strategy

(Maranto, 2013). However, if smaller rural school districts consolidate, a localized

sense of community could be disrupted—undermining this key attraction of rural

schools (Duncombe & Yinger, 2010).

Such studies have illuminated the factors impacting teacher shortages and

retention in rural schools. However, much of the literature on rural teachers

focuses on single settings (e.g., Brownell et al., 2005; Seelig & McCabe,

2021) or on single states (e.g., Goff & Brueker, 2017; Kane, 2010; Maranto,

2013; Miller, 2012)—providing in-depth analyses, but not a broader portrait.

Moreover, much of this research focuses solely on rural areas and does not

entail comparisons to other types of communities (e.g., Lowe, 2006; Monk,

2007). As a result of these limitations, it remains unclear what are the overall

levels of teacher staffing problems, shortages and turnover in rural schools

across the U.S., and whether these have been the same, or different, than those

in other types of communities and locales. This study seeks to address this gap.

The Study

The objective of this study is to analyze national data to provide an overall por-

trait of teacher shortages and turnover in rural schools across the nation. Our

method is comparative; we specifically focus on rural schools and compare

them to schools in other types of locales and communities. This study is an exten-

sion of our above-described prior research on teacher turnover and shortages to

focus on teacher staffing problems in rural schools Understanding the larger

national landscape of teacher shortages and turnover in rural schools provides

a larger context for the other papers in this special journal issue on spatial injus-

tice in rural education, and is essential to understanding the sources and solutions

to the ongoing teacher staffing problems confronting rural schools—an often

marginalized and neglected segment of the teaching force.

Research Questions

There are five specific research questions we seek to address:

Ingersoll and Tran 5

1. Has the Number of Rural Schools, Students and Teachers Changed in

Recent Decades?

What do the national data indicate about demographic changes in rural

education? Have there been changes in student enrollments, and the

size and age of the teaching force in rural schools? Do these trends

differ in other communities and locales?

2. To What Extent Do Rural Schools Have Teacher Shortages and

Staffing Problems?

To what degree do rural schools suffer from difficulties staf fing

their classrooms with qualified teachers? Does this differ from

schools in other communities and locales?

3. What Is the Role of Teacher Turnover in Rural Teacher Shortages and

Staffing Problems?

What portion of the demand for new teachers, and the subsequent

staffing problems in rural schools, is accounted for by teacher turn-

over? Does this differ from schools in other communities and locales?

4. How High is Teacher Turnover in Rural Schools?

What is the overall magnitude of teacher turnover? Do the turnover

rates differ across different kinds of rural schools and how do they

compare to those of teachers in other types of communities and

locales?

5. What Are the Reasons for Teacher Turnover in Rural Schools?

What reasons do rural teachers give for their departures? Do these

differ for teachers in other communities and locales? Which particular

aspects of schools and of teachers’ jobs, especially policy-amenable

factors, are most tied to the turnover of teachers?

Theoretical Perspective

The theoretical perspective we adopt in this research is drawn from organiza-

tional theory and the sociology of organizations, occupations, and work. Our

operating premise is that in order to fully understand the causes and conse-

quences of school staffing problems, it is necessary to “put the organization

back” into the analysis (cf. Stolzenberg, 1978), and to examine these issues

from the perspective of the schools and districts where these processes

happen, and within which teachers work. In organizational theory and

research, employee supply, demand, and turnover have long been central

issues (e.g., Hom & Griffeth, 1995; Jovanovic, 1979; Mobley, 1982; Price,

1977, 1989; Meirer & Hicklin, 2007; Siebert & Zubanov, 2009). However,

there have been few efforts to apply this theoretical perspective to

6 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

understanding staffing problems in education. By adopting this perspective,

we seek to discover the extent to which staffing problems in schools can be

usefully reframed from macro-level issues, involving inexorable societal

demographic trends, such as student enrollment and teacher retirement

increases, to organizational-level issues, in volving policy-amenable aspects

of the structure, management and leadership in school districts and schools

(see Woulfin & Allen, 2022 for discussion of the use of organzational

theory to improve schools).

We developed this organizational theoretical perspective in a series of

studies, beginning over two decades ago, analyzing multiple national data

sources, especially the National Center for Education Statistics’ Schools

and Staffing Survey (SASS)/Teacher Follow-Up Survey (TFS), to empirically

evaluate the adequacy of the supply of qualified teachers, to establish the

extent of teacher shortfalls, to empirically investigate the role of teacher turn-

over in shortages, and in turn to empirically investigate the reasons for teacher

turnover (Ingersoll, 1997, 2001; Ingersoll & May, 2012; Ingersoll & Perda,

2010). We focused on those specific years over the past 3 decades that had

the most severe teacher shortages.

These analyses established that a substantial number of schools each year

report serious problems filling their teaching position openings, especially in

fields such as mathematics and science. But, our data also showed these

teacher staffing problems are not simply a result of an insufficient supply of

new teachers. We documented that there are multiple sources of the new

supply of teachers, of which a relatively minor source has been the primary

focus of research and commentary—the pipeline of newly qualified candidates

with degrees from teacher education programs. Often ignored, but far larger,

sources are those candidates in the pipeline with non-education degrees, and

the reserve pool of former teachers. Our data showed the teacher supply,

from all of the above sources combined, has been more than sufficient to

cover both student enrollment and teacher retirement increases, even in years

when teacher staffing problems and shortages have been most severe, and

even for the highest shortage teaching fields, such as math and science.

However, our data also showed that this was not the case when we

included the departures of teachers before retirement—a figure that is many

times larger than retirement departures. The data showed that much of the

hiring of new teachers prior to a school year was simply to fill spots

vacated by other teachers who departed their schools at the end of the prior

school year, and most of these departures are not a result of an aging work-

force. Rather, preretirement turnover is a primary factor behind the demand

for new hires and the accompanying difficulties schools have adequately

staffing classrooms with qualified teachers. In turn, we documented that

Ingersoll and Tran 7

teacher turnover varies greatly among different kinds of schools, serving dif-

ferent student populations, and is closely tied to the quality of leadership and

organizational conditions in schools. Hence, the data suggests that improving

teacher retention, through effective school leadership and by improving

school organizational conditions, could be an important antidote to teacher

staffing problems, and ultimately, improving school performance. From this

empirical research, we derived an alternative perspective to longstanding

dominant theory regarding teacher shortages and the perennial staffing prob-

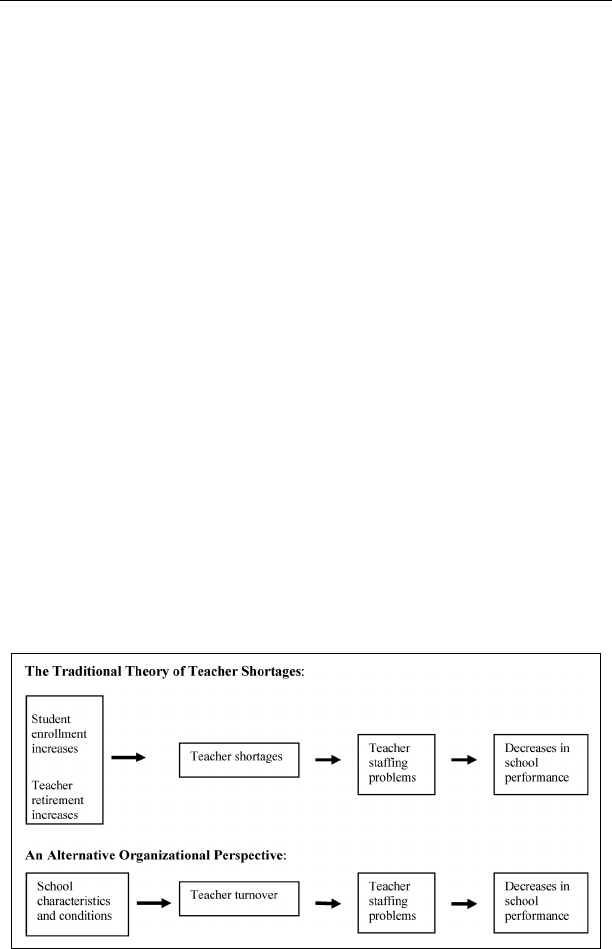

lems encountered by many schools (see Figure 1).

Over the past two decades we have extended this research and utilized this

perspective to examine teacher shortages and turnover in particular types of

schools (e.g., high-poverty) and for specific types of teachers. In particular,

we have undertaken sustained investigations of two segments of the teaching

force widely believed to face the most severe shortages—mathematics/

science teachers (Ingersoll & May, 2012; Ingersoll & Perda, 2010) and teach-

ers from under-represented racial-ethnic groups (Ingersoll & May, 2011;

Ingersoll et al., 2019, 2022). This study seeks to extend our perspective to

the case of teachers in rural schools. It is important to note that the above

two perspectives in Figure 1 are not mutually exclusive, but complimentary,

and we examine our data in light of both perspectives. Research question (1)

focuses on demographic changes in rural education, including changes in

student enrollments and the size and age of the teaching force—two trends

central to traditional theory on teacher shortages. Research questions (2–5)

Figure 1. Two perspectives on the causes and consequences of teacher staffing

problems.

8 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

utilize our organizational perspective to examine shortages and turnover in

rural schools.

In the next section, we describe our data and methods. In the following sec-

tions of this article, we present the results sequentially for each of our research

questions. We then conclude by summarizing our findings and discussing

their implications for understanding and addressing teacher staffing problems

in rural schools.

Data and Methods

The primary source of data for this study is the SASS and its successor, the

National Teacher Principal Survey (NTPS) collected by the Census Bureau

for the National Center for Education Statistics, the data collection agency of

the US Department of Education. SASS/NTPS is the largest and most compre-

hensive data source available on teachers in elementary and secondary schools.

SASS/NTPS administers questionnaires to a random sample of about 40,000

teachers, 11,000 schools, and 4,500 districts, representing all types of teachers,

schools, districts, and all 50 states. NCES has administered these surveys on a

regular basis; to date, nine cycles have been completed—1987–88, 1990–91,

1993–94, 1999–2000, 2003–04, 2007–08, 2011–12; 2015–16, 2017–18 (for

the two most recent cycles, the name of the survey was changed from the

SASS to the NTPS). The data represent teachers for kindergarten through

grade 12, part-time and full-time, and from all types of schools, including

public, charter, and private. Our analysis uses data from all cycles of SASS/

NTPS available, over the three-decade period from 1987 to 2018. Among

the strengths of the SASS/NTPS are its large sample size and its long duration.

These allow us to explore changes in the teaching force over time and to make

accurate comparisons among different types of teachers and schools (for more

information on the 2017–18 NTPS, see Taie & Goldring, 2020).

In addition, up to the 2011–12 cycle of SASS, all those teachers in the

school sample who departed from their schools in the year subsequent to

the administration of the initial SASS survey questionnaire were contacted

to obtain information on their departures. This nationally representative sup-

plemental sample—the TFS—contains about 6,000 teachers. The TFS distin-

guishes two general types of turnover. The first, often called teacher attrition,

refers to those who leave teaching altogether. The second type, often called

teacher migration, refers to those who transfer or move to different teaching

jobs in other schools. Our analysis focuses in particular on data from the most

recent TFS, administered in 2012–13, which only included public school

teachers (for more information on the 2012–13 TFS, see Goldring et al.,

2014). A possible limitation of our study is the utilization of turnover data

Ingersoll and Tran 9

from 2013, collected almost a decade ago. However, our prior analyses have

revealed that patterns of levels, variations and reasons for turnover have

showed little change since the late 1980s.

Along with collecting data on the rates of turnover, the TFS questionnaire

includes a set of items that asked teacher-respondents to indicate the reasons

for their departures from a list in the survey questionnaire. Self-report data

such as these are useful because those departing are, of course, often in the

best position to know the reasons for their departures. But, such self-report

data are also retrospective attributions, possibly subject to bias and, hence,

warrant caution in interpretation. In past analyses we have utilized the self-

report data in conjunction with multiple regression analyses of the relation-

ship between school characteristics and job conditions and the likelihood of

teachers departing (e.g., Ingersoll, 2001; Ingersoll & May, 2012; Ingersoll

et al., 2019). Those analyses showed a strong level of consistency between

the self-reported reasons for turnover, and the factors correlated with the like-

lihood of turnover, giving us some confidence in the usefulness of the self-

report data.

Our analyses focuses on teachers in public schools in rural communities or

locales and compares them with the population of teachers and public schools

in urban and suburban locales and communities. Following NCES, we utilize

the Census Bureau’s classifications of lo cales based on their degree of urban-

icity. Census and NCES twice altered the definitions of locales over the period

of SASS/NTPS data collections, an issue we account for in our data analysis

(for details on locale definitions, see U.S. Department of Education, 2002; and

Chen et al., 2011).

2

In the 2017–18 NTPS, 20.4% of public schools were clas-

sified as rural schools, employing 17.9% of all public school teachers, and

enrolling 18.8% of all public school students. The 2017–18 NTPS samples

represent 23,859 rural public schools, with 727,171 teachers and 9,544,311

students.

A possible limitation of our analysis is our use of standardized definitions

of rurality. Analysts have used differing definitions of rurality, each with

advantages and weaknesses (Hawley et al., 2016). Rurality, for example,

can be defined based on a specific community, which can capture rich contex-

tual depth, but may fail to generalize to other rural communities. On the other

hand, a standard ized definition of rurality, such as we use, allows for broad

comparisons, but may not account for variations among different rural

communities.

From the SASS/NTPS, we analyze data on trends in the numbers of

schools, students and teachers; the portion of schools with teaching job open-

ings by field, and the degree of difficulty school administrators report filling

their teaching job openings. From the TFS, we analyze data on the rates,

10 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

magnitude, variations of, and reasons f or, teach er turnov er. Given our

objective of providing a broad national portrait, we primarily present

descriptive data estimates we generated using basic statistical analytic

techniques. In addition, as background, we undertook analyses of vari-

ance to assess the t he portions of th e variation in our measures of both

teacher shortages and turnover that lie at the school level. In this

study, we do not include multivariate analyses of, for instance, the rela-

tive effects of different factors on turnover, as we have done elsewhere.

Where we report comparisons for our descriptive measures, for example

between teacher estimates for rural school teachers and urban school

teachers,weindicatewhetherdifferences ar e statisticall y significant at

a 95% level of confidence. However, it is important to note that, given

the large sample size of the SASS and NTPS, most differences

between estimates are highly statistically significant, even if the differ-

ence is small. In our discussion below, we focus on larger differences

that are of substantive significance . Beca use the TFS has a smaller

sample size, we include standa rd e rrors in our tables presenting those

data. The SASS/NTPS/TFS use a complex stratified survey design with

over- a nd unde r-sampling of par ticular s ubgroups. To obtain unbiased

estimates of the national population o f schools, students, and teachers

in the year of t he survey, the observations are w eighted by the inverse

of their probability of selection.

Results

Has the Number of Rural Schools, Students and Teachers

Changed in Recent Decades?

Prior to turning to our main topic of teacher shortages and turnover in rural

schools, we first examine the larger context of demographic changes in

rural education, including chang es in student enrollments and the size and

age of the teaching force— two trends central to traditional theory on

teacher shortages (see Figure 1).

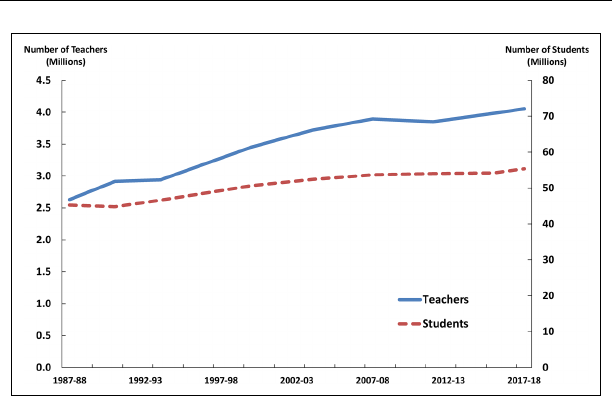

Over the past three decades total elementary and secondary student enroll-

ments in the US have steadily risen (see Figure 2). Expansion in the student

population is not new. The numbers of students grew throughout the twentieth

century, and the rate of growth began to soar in the late 1940s with the post–

World War II baby boom. Student enrollment peaked by 1970 and then

declined until the mid-1980s. In the mid-1980s, elementary and secondary

student enrollment again began to grow and has continued since (for

details, see Ingersoll et al., 2021).

Ingersoll and Tran 11

Given these overall increases in student enrollments, not surprisingly, the

data also show, that for any given year, most schools have had job openings

for which teachers were recruited and interviewed, the number of teachers

hired annually has increased, and over the past three decades the size of the

teaching force has increased. As also illustrated in Figure 2, interestingly,

the number of teachers employed has increased at a faster pace than that of

students enrolled—at over twice the rate—a striking finding we explore in

more depth elsewhere (Ingersoll et al., 2021; Ingersoll, May, et al., 2022;

Ingersoll, Merrill, et al., 2022).

Our focus here is on how these demographic changes differ by locale.

Assessing these changes by locale over time is complicated because, as men-

tioned earlier, the Census Bureau, twice altered, in 1998 and 2005, the defi-

nitions of urban, suburban and rural. Hence, it is unclear what part of the

changes in populations, by locale, are due to actual changes, or to changes

in the definitions of those locale categories. To account for the definitional

changes, we separately examine the data for the discrete periods within

which the definitions are consistent. Table 1 presents data for two periods

—1999–2004 and 2007–2018—separately by locale.

While the number of schools, the number of students, and the number of

teachers in urban and suburban communities, all increased in recent decades,

the opposite occured in rural communties. Combining the two time periods,

Figure 2. Trends in the number of elementary and secondary school teachers and

students, from 1987–88 to 2017–18.

12 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

Table 1. Trends in the Number of K-12 Public Schools, Students and Teachers, by School Locale, 1999–2018.

1999–00

school year

2003–04

school year

% Change

1999–00 to

2003–04

2007–08

school year

2011–12

school year

2015–16

school year

2017–18

school year

% Change

2007–08 to

2017–18

1.) K-12 Schools

a.) Urban 20,395 21,985 +7.8 21,455 23,563 24,777 25,379 +18.2

b.) Suburban 37,786 42,325 +12 25,805 24,261 29,109 29,656 +14.9

c.) Rural 16,500 14,952 −9.4 29,426 29,939 24,393 23,859 −18.9

2.) K-12 Students

a.) Urban 12,974,462 13,971,998 +7.7 13,023,628 14,152,564 14,938,083 15,235,699 +17

b.) Suburban 23,202,305 24,915,764 +7.4 16,812,011 16,215,457 19,400,265 20,082,857 +19.5

c.) Rural 4,636,507 4,475,753 −3.5 12,046,403 13,433,238 9,238,284 9,544,311 −20.8

3.) K-12 Teachers

a.) Urban 811,284 929,391 +14.6 882,433 958,761 1,179,747 1,032,003 +17.4

b.) Suburban 1,511,074 1,704,231 +12.8 1,200,728 1,098,415 1,512,885 1,373,527 +14.4

c.) Rural 355,293 339,037 −4.6 853,853 916,582 718,080 727,171 −14.8

13

the data show that over recent decades the number of schools in urban areas

increased by 26%, the number of students by 25%, and the number of teachers

by almost a third. There has also been a similar increase in suburban commu ni-

ties. In contrast, the number of schools in rural communities has decreased by

over 28%, the number of students by 24% and the number of teachers by

19%. Moreover, the pace of these decreases appears to have accelerated over

time, especially since 2012.

Along with student enrollment increases, traditional teacher shortage

theory also holds that an aging of the teacher force, and hence increasing

retirements, is a large factor behind shortages (see Figure 1). And, our data

analyses confirm that since the late 1980s there has, in fact, been an increase

in the mean age of teachers, in the number of teachers over age 50, and in

teacher retirements. But, the data also show this trend has changed in the

past decade. While data on teacher retirements are not available beyond

2012–13, the data on the teacher age distribution show that, since 2011–12,

the teacher aging trend began to vary by locale. Between 2012 and 2018,

the number and percent of teachers approaching retirement (age 50 or

more) increased in suburban schools, stayed steady in urban schools, but

decreased in rural schools by 23%. In short, in recent years there has not

been an overall aging of the rural teaching force.

To What Extent Do Rural Schools Have Teacher Shortages and

Staffing Problems?

Given rural schools’ above-described decrease in students, along with a

decrease in the number of older teachers, (and hence in subsequent retire-

ments), and in turn a decrease in demand for, and employment of, new teach-

ers, traditional teacher shortage theory would predict that such schools would

have less difficulty staffing their classrooms, that is, suffer less from teacher

shortages and staffing problems. In contrast, traditional shortage theory would

also expect the opposite in urban and suburban schools, with their increase in

students, along with an increase in retirement-age teachers (especially in sub-

urban schools) and hence increase in demand for, and employment of, new

teachers.

The most grounded and accurate empirical measures available of the extent

of actual teacher staffing problems and shortages in schools are data from

school administrators on the actual degree of difficulty they encounter

filling their teaching position openings (e.g., Behrstock, 2009; Ingersoll,

2001; Ingersoll & Perda, 2010). Importantly for our analysis, SASS/NTPS

collect data on the numbers of school principals reporting teaching job

14 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

openings for the upcoming school year and those that experienced diffi culties

filling those openings. The most recent data from SASS/NTPS for this indi-

cator are from the 2015–16 cycle.

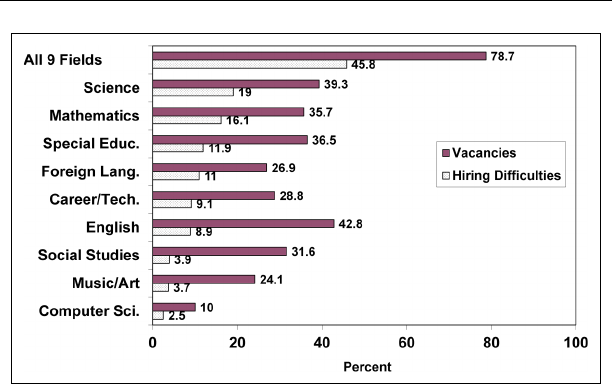

Figure 3 focuses on rural public secondary schools. It presents data on

the percent of principals reporting their school had teaching vacancies at

the start of the school year—teaching positions for which teachers were

recruited and interviewed—and the percent that reported they experienced

serious difficulty filling one or more of those vacancies. As shown in the

top row of Figure 3, overall, over three quarters of principals in rural

public secondary schools had teaching vacancies in one or more of nine

key teaching fields, and over half of those reported they had serious dif fi-

culty staffing those positions—representing 46% of all rural public second-

ary schools.

Moreover, the data also show large field-to-field differences in vacancies

and staffing difficulties in rural schools. Mathematics and science experienced

their most serious problems in rural schools. Thirty-nine percent of rural

public secondary schools had job openings for teachers in science, and

about 44% of these indicated serious difficulties filling these openings, repre-

senting 19% of rural public secondary schools. Similarly, 36% of secondary

schools had job openings for mathemati cs teachers, and about half of these

indicated serious difficulties filling these openings, representing about 16%

of all rural public secondary schools.

Figure 3. Percent rural public secondary schools with teaching vacancies and with

serious difficulties filling those vacancies, by teaching field.

Ingersoll and Tran 15

On the other hand, for some teaching fields, few schools had serious diffi-

culty filling positions. For instance, as also shown in Figure 3, in the field of

social studies, 32% of rural public secondary schools had job openings, but

only about 13% of these—representing only 4% of all rural public secondary

schools—indicated that they had serious difficulty filling those openings.

Table 2 presents the same data on teacher staffing problems, but with com-

parisons of urban, suburban and rural schools. The data reveal that levels of

staffing difficulties were very similar for both rural and non-rural schools. As

shown in the top row, overall, suburban public secondary schools were

slightly less likely to experience difficulties filling their teaching positions

—42% reported difficulties in one or m ore of the nine fields, compared to

46% for both urban and rural schools (differences at statistically significant

levels). But, in most fields there were not large differences between urban,

suburban and rural schools in the percentages of schools with staffing

problems.

In sum, the data show that, as expected, many schools have had staffing

problems. But, surprisingly, this has been just as true for rural as other

schools. Despite decreasing numbers of students, and hence demand for

teachers, many rural schools have nevertheless had difficulties staffing their

teaching positions. In short, rural schools have faced similar teacher shortages

and staffing problems as urban schools. Moreover, our analyses of these same

measures from earlier cycles of SASS, from the early 1990s, also reveal that

while levels of staffing problems have risen and fallen, these cross-field and

Table 2. Percent Public Secondary Schools with Serious Difficulties Filling Teaching

Vacancies, by Teaching Field, by School Locale.

School locale

All Urban Suburban Rural

Teaching field

All 9 fields 44.4 45.8 42.2 45.8

Science 19.9 19.3 22.6 19

Math 16.7 21.9 13.1 16.1

Special ed. 13.7 15.6 12.2 11.9

Foreign language 10.2 11.7 8.6 11

Career/technical ed. 8.6 6.1 9.6 9.1

English 6.4 6.3 3.1 8.9

Computer science 3.6 4.7 3.7 2.5

Music/art 2.9 3 2.5 3.7

Social studies 2.6 3.4 .7 3.9

16 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

cross-locale patterns in teacher staf fing problems and shortages have

remained consistent over time.

It is important to recognize that for all these locales, as shown in Figure 3

and Table 2, while the actual number of schools is substantial, it represents a

minority of schools that have had serious staffing problems in any given fi eld,

in any given year. That is, teacher shortages are limited to particular schools

and particular fields. Moreover, while there has not been large differences in

staffing difficulties, on average, across schools from rural, urban, and subur-

ban locales, there are nevertheless, large school-to-school differences. In our

background analyses of variance of these data we found that the variation in

levels of school staffing difficulties is far greater within, than between, states

and, moreover, such variation is far greater between schools than between

school districts.

3

The largest variation in the degree of staffing difficulties

and in staffing problems by location are those between different schools,

even within the same school district. Moreover, our analyses document that

the poverty level of schools is one of the strongest correlates of their

degree of staf fing difficulties; high-poverty schools are far more likely to

have serious staffing difficulties than low-poverty schools. In other words,

within the same state, locale, teacher labor market, and licensure and

pension systems, the extent of shortages varies greatly among different

schools—suggesting the usefulness of our organizational-level perspective

to understand the sources of these staffing problems—which we turn to in

the next sections.

What is the Role of Teacher Turnover in Rural Teacher Shortages

and Staffing Problems?

The above data from school administrators on the degree of difficulty encoun-

tered filling teaching job openings is a useful empirical measure of teacher

shortages and staffing problems. But, data on the extent of staffing difficulties

themselves do not indicate the sources of these difficulties. In particular, these

data do not themselves distinguish whether rural schools’ staffing problems

are primarily a result of an inadequate quantity of new teacher supply, or

high levels of teacher turnover. While the SASS/NTPS data do not allow

us to assess the former, the data do allow us to examine the latter—levels

of teacher turnover in rural schools and their role in teacher staffing problems.

Researchers have long held that elementary and secondary teaching has

relatively high rates of annual departures of teachers from schools (Lortie,

1975; Murnane et al., 1991; Tyack, 1974). To empirically compare teacher

departure rates to those in other occupations and lines of work, we analyzed

Ingersoll and Tran 17

national data from two different administrations of NCES’ longitudinal

Baccalaureate and Beyond Survey (1993–2003 and 2008–18). We found

that attrition in teaching (those leaving the occupation entirely) is lower

than in some lines of work (child-care workers, secretaries, paralegals), is

slightly higher than police officers and nurses, and far higher attrition than

some established and traditional professions, such as law, engineering, archi-

tecture (see Ingersoll et al., 2021; Ingersoll, May, et al., 2022; Ingersoll,

Merrill, et al., 2022).

However, it is important to recognize that K-12 teachers form one of the

largest occupational groups in the nation (U.S. Bureau of the Census,

2018) and hence, given their relatively high turnover levels, numerically,

the flows of teachers in and out of schools are large. To illustrate this phenom-

enon for rural schools, we analyzed data from the most recent SASS/TFS

cycle that included data on both hiring and turnover (2011–13). As shown

in Figure 4, about 90,000 teachers entered rural public schools, at the begin-

ning of the school year, and by the following school year, about 145,000—

equivalent to 162% of those just hired—departed from their schools. Thus,

during that 10–12 month period, before, during and after that school year,

there were about 245,000 teachers in job transition into, between or out of

rural public schools, representing over one quarter of the entire rural public

teaching force—a scenario akin to a “revolving door.”

While this revolving-door pattern is similar for rural, urban and suburban

schools and is consistent across the cycles of SASS/TFS, the ratio of turnover

to hiring is especially high for rural schools because of their decline in the

Figure 4. Numbers of teachers in transition into and out of rural public schools

before and after school year.

18 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

number of students and teachers, as evidenced in Table 1. Hence, the need for

new hires, and accompanying staffing difficulties, in rural schools, are not

driven by increases in student enrollments—as students in rural schools

have decreased. Rather, the data show that the hiring of new teachers in

rural schools prior to a school year is largely to fill spots vacated by other

teachers who departed their schools at the end of the prior school year.

It is important to note that the incoming and outgoing teacher flows in

Figure 4 are calculated at the level of the school. Hires and turnover refer

to those newly entering or departing a particular school. Cross-school

moves, even within districts, are counted as hires or as turnover. Total

teacher turnover as depicted in Figure 4 is fairly evenly split between its’

two major components—migration and attrition. Teacher migration, of

course, does not decrease the overall net supply of teachers, as does those

leaving for retirement and career changes, and hence does not contribute to

overall shortages from a system level of analysis. However, that does not

mean that cross-school and cross-district moving do not contribute to

teacher staffing problems in particular schools. From an organizational per-

spective, and from the viewpoint of those managing educational organiza-

tions, teacher migration and attrition have the same effect; in either case,

they result in a decrease in staff that usually must be replaced, and, at times

resulting in staf fing difficulties and staffing problems. Moreover, as we

show in the next section, cross-school moves are asymmetric; the flows to

and from schools in different locales are not evenly balanced.

In addition, a portion of those leaving teaching represent temporary attri-

tion. The latter, of course, do not result in a permanent loss of human capital

from the teacher supply and, hence, do not permanently contribute to overall

shortages. Indeed, the re-entrance of former teachers is a major source of new

supply (Ingersoll & Perda , 2010). However, like migration, that does not

mean that the departure of teachers for one or more years does not contribute

to teacher staffi ng problems. Again, from a school-level and organizational

perspective, temporary attrition results in a decrease in staff that usually

must be replaced, regardless of whether those leaving later return to that

same school or another.

We further empirically confirmed our hypothesis of a link between teacher

turnover and shortage problems using a school-level of measure of turnover.

The data show that those schools with serious teacher staffing problems (as

shown earlier in Table 2 and Figure 3), were almost twice as likely to have

had above-average turnover rates the prior year, as those schools reporting

no difficulties. And, as we will show in the next sections, most of these depar-

tures were not a result of an aging and retiring teaching force. Rather, prere-

tirement voluntary turnover is behind the majority of the demand for new

Ingersoll and Tran 19

hires, and the accompanying difficulties rural schools have adequately staff-

ing classrooms. In short, in rural schools, preretirement teacher turnover is the

primary driver behind shortages and staffing problems.

How High is Teacher Turnover in Rural Schools?

It is important to recognize that above-described overall levels of turnover

mask large differences in teacher departure rates from different types of

schools, revealing the need to disaggregate our data. The flow of teachers

out of schools is not equally distributed across states, regions, and school dis-

tricts. However, as with our background analyses of variance of the staffing

difficulties data discussed in the prior section, our background analyses of

variance of teacher turnover documented that the largest variations in

teacher departures by location, are those between different schools, even

within the same district.

4

Moreover, our analyses of the data show that

teacher turnover is concentrated—in any given year almost half of all

public school teacher turnover takes place in just one quarter of the population

of public schools. The poverty level of schools is one of the strongest

Table 3. Percent Teacher Migration and Attrition, by School Locale and School

Poverty Level.

Turnover

Migration Attrition Total

School locale and poverty level

All 8.1 (.4) 7.7 (.4) 15.8 (.6)

Urban 7.9 (.9) 9.8 (.8) 17.7 (1.)

Suburban 7.8 (.8) 7.3 (.8) 15.1 (1)

Rural 7.0 (.7) 8.4 (.7) 15.4 (.9)

Low-poverty 6.2 (1) 5.4 (.9) 11.6 (1.3)

High-poverty 12.4 (1.3) 9.6 (1.1) 22.1 (1.6)

Low-poverty suburban 6.5 (1.7) 5.3 (1.3) 11.8 (1.9)

High-poverty urban 12.1 (1.8) 7.0 (1.4) 19.1 (2.2)

Low-poverty rural 5.1 (1.6) 6.2 (1.8) 11.3 (2.4)

High-poverty rural 10.7 (2.4) 17.2 (2.9) 27.9 (3.4)

Standard errors in parentheses.

Note. High-poverty schools refer to those in which 80 percent or more of the students qualify for

the National School Lunch Program. Low-poverty schools refer to those in which less than 15

percent of the students qualify for the National School Lunch Program.

20 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

correlates of teacher turnover; high-poverty schools have significantly higher

turnover than do low-poverty schools.

As shown in Table 3, overall rural public school teacher turnover is about

average (15.4%), urban teachers have slightly higher than average rates

(17.7%), and suburban teachers have slightly lower rates (15.1%) (these dif-

ferences are of borderline statistical significance). High-poverty schools (in

which 80% or more of the students qualify for the National School Lunch

Program) have almost double the rate of turnover as do low-poverty

schools (less than 15% NSLP), and at a very high level of statistical signifi-

cance. And, schools that are both high-poverty and urban have amongst the

highest rates of turnover (19.1%).

However, strikingly, the data show that high-poverty rural public schools

have unusually high rates of turnover—almost 28% of their teachers depart

annually (12% of rural public schools were in high-poverty communities). Of

note, high-pove rty rural pub lic schools h ave higher turnov er than high-p overty

urban schoo ls, a difference at a very high level of statistical significance.

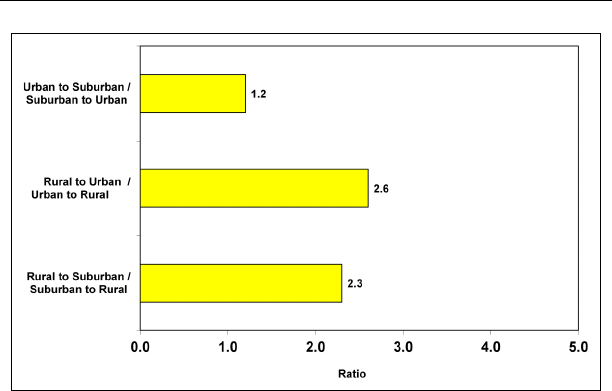

The data also show substantial, and uneven, annual teacher migration across

locales. We used the TFS data to more closely examine the characteristics of the des-

tination schools of cross-school migrants in order to discern the degree of symmetry

in teachers’ moves to and from school in different locales. We calculated ratios of the

percentage of teacher movers going from one school locale to another, to the percent-

age moving in the reverse direction. The data show that, interestingly, there is an

Figure 5. Ratio of percentages of teachers migrating in opposite directions to and

from public schools in different locales.

Ingersoll and Tran 21

annual net gain and loss for schools, according to school locale. For instance, as

shown in Figure 5, teachers who migrated were over twice as likely (ratio of 2.6)

to move from rural to urban schools, as in reverse—from urban to rural schools.

Likewise, teachers were over twice as likely (ratio of 2.3) to move from rural to sub-

urban schools, as in reverse—from suburban to rural schools. In contrast teacher

migration from urban to suburban was only slightly higher than in reverse (ratio

of 1.2). The net result is a large annual asymmetric reshuffling within the school

system of a substantial portion of the teaching force, with a net loss to rural

schools and a net gain to urban and suburban schools. These findings on migration

provide further support for our theoretical perspective that fully understanding the

staffing problems of schools requires examining them from a school level and

from the perspective of the organizations in which they occur.

What Are the Reasons for Teacher Turnover in Rural Schools?

These data raise severa l questions—what are the reasons for teacher turnover,

why do some schools have far higher turnover than others and, for our focus,

Table 4. Percent Teachers Reporting Various Reasons Were Important for Their

Turnover, by School Locale.

School locale

Urban Suburban Rural

Reasons for turnover

Retirement 15 (1.3) 24.4 (1.6) 21.7 (1.3)

School staffing action 22.7 (1.6) 22.7 (1.6) 12.8 (1.1)

Family or personal 40.5 (1.8) 46.1 (1.9) 47.7 (1.6)

To pursue other job 34.4 (1.8) 33.1 (1.8) 41 (1.6)

Dissatisfaction 53.2 (1.8) 54.8 (1.9) 61.1 (1.6)

Reasons for dissatisfaction-related turnover

Dissatisfied with the administration 59 (2.4) 57.5 (2.5) 63.1 (2.1)

Dissatisfied with accountability/testing 59.4 (2.4) 66.3 (2.4) 55.5 (2.2)

Lack of faculty influence and autonomy 48.1 (2.4) 59.1 (2.5) 50.3 (2.2)

Too many student discipline problems 47.4 (2.4) 48.7 (2.6) 45.7 (2.2)

Intrusions on teaching time 45.5 (2.4) 58.9 (2.5) 45.3 (2.2)

Unsafe or inadequate facilities or resources 50.7 (2.4) 52 (2.6) 41.7 (2.2)

Too few prof advancement opportunities 33.5 (2.3) 30.5 (2.4) 35.9 (2.1)

Dissatisfied with job assignment 39.4 (2.4) 48 (2.6) 35.5 (2.1)

Poor salary or benefits 27.5 (2.2) 24.8 (2.2) 34.3 (2.1)

Too many students 29.2 (2.2) 39.4 (2.5) 17.6 (1.7)

22 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

what are the reasons for teacher turnover in rural schools? One method of

answering these questions is to ask those who have moved or left why they

did so. We examined such self-report data drawn from items in the TFS ques-

tionnaire that asked teachers to indi cate the level of importance of 22 factors,

listed in the survey questionnaire, in their decision to move or leave. The top

panel in Table 4 presents data on the percentage of teachers who reported that

particular categories of reasons were “very” or “extremely” important in their

decision to depart on a five-point scale from “not important” to “extremely

important.”

5

Note that the percentages in the top panel of Table 4 add up

to more than 100%, because respondents could indicate more than one

reason for their departures and hence our categories are not mutually exclu-

sive. The table compares rural with urban and suburban teachers.

Overall, rural teachers were both similar and different from other teachers

in the general patterns regarding the reasons why they moved from or left their

jobs. Retirement is listed by about 22% of the total of those who departed as

an important reason for their departure. This is an important finding because,

as reviewed earlier, traditional theory on teacher shortages has long held that

an aging and retiring teaching force is a major factor behind teacher

shortages. However, the data show that retirement accounts for a relatively

small portion of departures compared to other reasons.

School staffing actions include layoffs, terminations, school closings and

reorganizations and involuntary cross-school transfers. Sometimes these staffing

actions entail migration to other schools and other times leaving teaching alto-

gether. Like retirement, these account for only a relatively small portion of

total turnover from schools—about one-fifth of urban and suburban teachers.

Rural teachers were less likely (less than 13%) and at a statistically significa nt

level, to cite this category of reasons for their departures than teachers in

other schools.

A third category of turnover—for family or personal reasons—includes

departures for pregnancy/child rearing, health problems, and family moves,

including taking a job more conveniently located. These account for more turn-

over, and at a statistically significant level, than either retirement or staffing

actions. These reasons are also probably common to all occupations, and all

types of organizations, and a normal part of worklife. Just under half of all teach-

ers cite these as reasons for their departures. Rural teachers were not more or

less likely to cite this reason than others at a statistically significant level.

A fourth category—to pursue another job—includes those who moved to

another school, those who left teaching to pursue another career, or to take

courses to improve their career opportunities within or outside the field of

education. Some of the latter are only temporary leavers, and after getting a

graduate degree or advanced credential, re-enter teaching as part of the new

Ingersoll and Tran 23

supply. Notably, rural teachers were more likely, at a statistically significant

level, to cite this category— to pursue another job—as a reason for their depar-

tures than either urban or suburban teachers.

Finally, the largest category is those who departed because they were dissat-

isfied with some aspect of the teaching job. Over half of all departing teachers

reported that job dissatisfaction was “very” or “extremely important” in their

decision to depart. Strikingly rural teachers were more likely to cite this category

(61%), at a statistically significant level, than either urban or suburban teachers.

The data indicate that over 79,000 rural teachers left teaching altogether just after

the school year. Only about 32,000 of these left because of retirement. That is,

almost three times as many indicated that job dissatisfaction was an important

factor in their decision to leave teaching, co mpared to retirement.

These data raise a further question: of those who reported dissatisfaction

with some aspect of their job as a reason to depart, what were their particular

sources of dissatisfaction. The bottom panel in Table 4 presents disaggre gated

data on ten particular factors included in this category. The data reveal that

there were large differences in the factors most likely to be cited by teachers

and also some differences between rural and other teachers.

Among rural teachers, dissatisfaction with the school administration was

the most common factor cited (63%) as important to their decision to

depart. Rural teachers were more likely to cite this reason, at a statistically sig-

nificant level, than suburban teachers. The next most frequently cited reasons

among rural teachers who departed because of dissatisfaction,

were dissatisfaction with accountability/testing (55%) and dissatisfaction with

a lack of classroom autonomy or lack of input into decision making (50%).

Compared to the above three reasons, rural teachers were less likely to

indicate that dissatisfaction with unsafe or inadequate facilities, with too

few professional advancement or leadership opportunities, and with their

job assignment, were important factors in their departures. The least likely

reasons given by rural teachers were dissatisfaction with their salaries/benefits

and dissatisfaction with the number of students/class-sizes. Only 34% of rural

teachers reported inadequate or poor salary and/or benefits were important

reasons to depart and less than one-fifth of rural departees reported dissatis-

faction with the numbers of students they taught as an important factor.

However, for both of these reasons, rural teachers differed from both urban

and suburban teachers, at a statistically significant level. Rural teachers

were more likely to cite salaries and benefits than others (NTPS data indicate

that in 2017–18, the average salary in public schools for a first-year teacher

was about $43,700, and for first-year teachers in rural schools it was about

$39,900). On the other hand, rural teachers less often reported the number

of students taught as a reason to depart than other teachers.

24 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

The data also reveal a similar pattern of reasons for both teacher migration

and attrition. A desire to pursue another job and job dissatisfaction were the

most cited categories by both movers and leavers. And for both movers and

leavers, dissatisfaction with the school administration, dissatisfaction with

accountability/testing and dissatisfaction with a lack of classroom auton-

omy/input into decision making were among the most frequently cited and

salaries and class-size were among the least frequently cited.

Conclusions and Implications

The objective of this study is to provide an overall national portrait of teacher

shortages and turnover in rural schools. Understanding the larger national land-

scape of these problems is essential to understanding the sources and solutions

to the teacher staffing challenges particular to rural schools, that researchers

have insightfully brought to light (for reviews, see ; McClure & Reeves,

2004). Tran & Dou, 2019; Tran et al., 2020) Our study revealed six findings:

The Rural School Sector is Shrinking

Our analysis began by examining larger demographic changes in rural educa-

tion, including changes in student enrollments and the size and age of the

teaching force—demographic trends central to traditional theory on teacher

shortages (Figure 1). In contrast to urban and suburban communities, over

the past couple of decades, the number of schools, students and teachers in

rural areas have decreased sharply. Moreover, unlike in urban and suburban

schools, over the past decade, the rural teaching force, overall, has gotten

younger, resulting in a decrease in the number and percent of teachers

approaching retirement age.

Many Rural Schools Suffer from Teacher Shortages

Despite a decrease in students, and accordingly a decrease in the demand for,

and employment of, teachers in rural schools, the latter are just as likely as

urban and suburban schools to have serious difficulties filling their teaching

openings. The fields of mathematics and science experienced the most

serious staffing problems in rural schools.

Many Rural Schools Suffer from a Revolving Door of Teachers

Our data indicate that teacher turnover is the primary driver of staffing prob-

lems and shortages in rural schools. The data show that preretirement

Ingersoll and Tran 25

departures of teachers are behind most of the demand for new hires, and the

subsequent staffing difficulties experienced, in many rural schools.

There Are Large Differences in Rates of Turnover Between Different

Types of Schools

Teacher turnover is especially high in high-poverty rural schools—over a

quarter of their teachers depart each year—and higher than in high-poverty

urban schools. Moreover, the data reveal large differences in the destinations

of teachers who migrated from one school to another. Movers were over twice

as likely to move from rural to urban, or rural to suburban schools, as in

reverse. The net result of this is a large annual reshuffling within the school

system of a large portion of the rural teaching force, with a net loss to rural

schools and a net gain to urban and suburban schools.

Job Dissatisfaction is the Primary Driver of Teacher Turnover

in Rural Schools

There are many factors behind school differences in teacher turnover. A major set

of factors involves teachers’ dissatisfaction with various aspects of the teaching

job. Over 60% of teachers departing from rural schools cite dissatisfaction as a

main reaso n for their departures and 41% indicate they are departing to pursue

a different or better job. These are higher levels than in urban or suburban schools.

School Organizational Conditions are Strongly Linked to Teacher

Turnover in Rural Schools

The leading factors behind dissatisfaction-related turnover in rural schools are

dissatisfaction with school administrations, dissatisfaction with accountability

and testing and dissatisfaction with a lack of classroom autonomy or lack of

input into school decision making.

Collectively, these findings, coupled with the earlier summarized research high-

lighting the particular teacher staffing challenges for rural schools, provide an

example of the spatial injustice faced by rural education—the relative disparities

in teacher staffing problems, teacher turnover, and the organizational factors

behind the latter (Tieken, 2017). According to our analysis, high-poverty rural

schools, in particular, face the most intense teacher turnover and yet the staffing chal-

lenges of rural schools receive less attention than those of their urban counterparts. It

is also important to acknowledge a possible data limitation in our study—the national

data we analyze extend to spring 2018. Currently, as of yet national data on teacher

shortages and turnover since the pandemic that began in spring 2020 have not been

26 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

released.This raises questions about whether these trends have continued into the

present, especially after the pandemic that began in spring 2020. Numerous com-

mentators have drawn attention to high levels of employee turnover across the

economy since the advent of the pandemic (e.g., Smith, 2022). Numerous reports

have also drawn attention to increased stress for teachers during the pandemic

(e.g., Wright, 2022). Future improvements in the economy could increase other

employment options for teachers, and in turn, increase in teacher turnover. This

will most likely be especially true for high-poverty rural schools. Hence, addressing

high teacher turnover could become even more important over time.

Implications

Where the quantity of teachers demanded is greater than the quantity of teachers

supplied, given the prevailing wages and working conditions, there are numer-

ous possible policy responses. Longstanding theory on teacher shortages

(Figure 1) holds that the main source of the problem is an insufficient supply

of new teachers, in the face of student enrollment and teacher retirement

increases. In turn, increasing the supply of new teachers has long been a dom-

inant reform strategy. Nothing in this study suggests these efforts are not worth-

while, but the data indicate that teacher recruitment strategies, alone, do not

directly address a major root source of teacher staffing problems—preretirement

turnover. In short, recruiting more teachers, while an important first step, will not

fully solve school staffing inadequacies if large numbers of such teachers then

depart in a few years. Decreasing the loss of those recruited by such initiatives

could prevent the loss of those investments, and also lessen the ongoing need for

creating new recruitment initiatives.

Our data analyses suggest that staffing problems in schools can be usefully

reframed from macro-level issues, involving inexorable societal demographic

trends, to organizational-level issues, involving aspects of the structure and

management of school districts and schools. From the organizational perspec-

tive of this analysis, schools are not simply victims of external demographic

trends. Rather our data suggest there is a significant role for school manage-

ment and leadership in both the genesis of, and solution to, teacher staffing

problems. From an organizational perspective, many of the reasons for

teacher turnover revealed by our data analysis are notable because they are

examples of manipulab le and policy-amenable aspects of particular districts

and schools, with implications for the management and leadership of schools.

Two of the most frequently cited organizational factors behind rural teacher

turnover – teachers’ decisionmaking influence and school accountability – are

also notable because they are central and longstanding tenets in the field of orga-

nizational theory. Experts in organizational leadership have long advocated a

Ingersoll and Tran 27

balanced approach to implementing organizational accountability and employee

authority in work settings (e.g., Drucker, 1992). In this view, accountability

and authority must go hand in hand in workplaces. Delegating autonomy or

authority to employees without also ensuring commensurate accountability can

foster inefficien cies and irresponsible behavior and lead to low performance.

Likewise, implementing organizational accountability without providing com-

mensurate autonomy and authority to employees can foster job dissatisfaction,

increase employee turnover, and lead to low performance. From this perspective,

both of these organizational structures are necessary, but neither alone is sufficient.

This balanced approach is a key characteristic underlying the theory and model of

the established professions, such as law, medicine, university professors, dentistry,

engineering (Freidson 1986). I n the professional model, practitioners are, ideally,

first provided with the training, resources, conditions, and autonomy to do the job

—and then they are held accountable for doing the job well. Translating this

balanced perspective to school settings, in prior research we have examined the

relative effects of both teachers’ decisionmaking influence and school accountabil-

ity in schools. We have documented that schools with both high levels of teacher

decisionmaking influence and strong academic standards for teachers, have both

better teacher retention and higher student achievement (e.g., Ingersoll 2003;

Ingersoll and Collins, 2019). To be sure, the data do not suggest that altering

any of the organizational conditions we examined would be easy, nor do the

data place blame on school leaders—there can be numerous financial, political,

organizational and legal barriers to improvements in schools as workplaces.

However, unlike reforms such as teacher salary increases and class-size reduction,

changing some of the organizational conditions revealed in the data, such as the

degree to which teachers have input into school-wide decisions, and the

amount of autonomy teachers hold in their classrooms, would appear to be less

costly financially—an important consideration, especially in rural settings.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publi-

cation of this article.

ORCID iDs

Richard M. Ingersoll https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7916-6454

Henry Tran

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2229-7111

28 Educational Administration Quarterly 0(0)

Notes

1. In educational research, the term shortage has typically been defined as an insuf-

ficient preparation of new teachers. This is a narrower definition than typically

used in economic supply and demand theory—which defines a labor shortage

as any imbalance where the quantity of labor demanded is greater than the quan-

tity supplied, given the prevailing wages and job conditions. In supply and

demand theory, such imbalances can result from a variety of factors, including

employee turnover. To avoid confusion between these differing definitions of

teacher shortages, here we will often use the term, teacher staffing problems,to

generically refer to the difficulties schools experience adequately staffing class-

rooms with qualified teachers.

2. Beginning with the 2007–08 SASS, Census and NCES no longer merged town

and rural as one locale; these became separate locale categories. In this study

we focus on rural and do not include town. Note that the latter is a relatively

small segment of the population of schools, students and teachers.

3. Using a one-way random effects ANOVA model, the data show that the variance

component within states is 44 times the size of the variance component between

states, and that between schools is 84 times that between districts.

4. For instance, using a 4-level logistic HLM model, estimated via MLwiN 2.20, we

partitioned the variance in teacher turnover in the 04-05 TFS. Of the total variance

in annual turnover, 77% was among schools, 16% was among districts, and 7%

was among states.

5. For the top panel of Table 3, from a list of 22 reasons, we created five categories, as

follows: (1) Retirement; (2) School Staffing Action: reduction-in-force/layoff/invol-

untary transfer; (3) Family or Personal: wanted a more conveniently located job or

moved; personal life reasons, such as pregnancy/child rearing; health; caring for

family; (4) To Pursue Other Job: to pursue another career; to take courses to

improve career opportunities within or outside the field of education; wanted to

teach at another school; (5) Dissatisfaction: poor salary or benefits; dissatisfied with

number of students; dissatisfied with job assignment; too many student discipline

problems; too many intrusions on teaching time; lack of faculty autonomy or influence

over school policies; unsafe or inadequate facilities or resources; lack of opportunities

for leadership or professional development; dissatisfied with accountability/testing;

dissatisfied with the administration.

References

Allen, N., Appleman, S., Jackson, A., & Rouse, K. (2023). Creativity from necessity:

A practical toolkit for leaders to address teacher shortages. Bellwether.

Alliance for Excellent Education. (2005). Teacher attrition: A costly loss to the nation

and to the states. Author.

American Federation of Teachers. (2022). Here today, gone tomorrow? What America

must do to attract and retain the educators and school staff our students need.

Author.

Ingersoll and Tran 29

Aragon, S. (2016). Teacher shortages: What we know. Teacher Shortage Series.

Education Commission of the States.

Barnes, G., Crowe, E., & Schaefer, B. (2007). The cost of teacher turnover in five dis-

tricts: A pilot study. National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future.

Behrstock, E. (2009). Teacher shortage in England and Illinois: A comparative history

[PhD Dissertation]. Oxford University.

Borman, G. D., & Dowling, N. M. (2008). Teacher attrition and retention: A meta-

analytic and narrative review of the research. Review of Educational Research,

78, 367–409.

Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2007). Who leaves?

Teacher attrition and student achievement. Teacher Policy Research Center, State

University of New York-Albany.

Brownell, M. T., Bishop, A. M., & Sindelar, P. T. (2005). NCLB and the demand for

highly quali fied teachers: Challenges and solutions for rural schools. Rural

Special Education Quarterly, 24(1), 9–15.

Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters

and what we can do about it? Learning Policy Institute.

Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). The trouble with teacher turn-

over: How teacher attrition affects students and schools. Education Policy

Analysis Archives, 27(36), 32 pp.

Chen, C., Sable, J., Mitchell, L., & Liu, F. (2011). Documentation to the NCES

common core of data public elementary/secondary school universe survey:

School year 2009–10 (NCES 2011-348). U.S. Department of Education,

National Center for Education Statistics. http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubs.info.

asp?pubid=2011348

Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2006, Fall). Teacher-student matching and the

assessment of teacher effectiveness. Journal of Human Resources, 41(4), 778–820.