AP

®

Human Geography

Teacher’s Guide

connect to college success

™

www.collegeboard.com

Paul T. Gray, Jr.

Russellville High School

Russellville, Arkansas

Gregory M. Sherwin

Adlai E. Stevenson High School

Lincolnshire, Illinois

AP

®

Human Geography

Teacher’s Guide

Paul T. Gray, Jr.

Russellville High School

Russellville, Arkansas

Gregory M. Sherwin

Adlai E. Stevenson High School

Lincolnshire, Illinois

ii

The College Board: Connecting Students to College

Success

The College Board is a not-for-profit membership association whose mission is to connect students

to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the association is composed of more than 5,000

schools, colleges, universities, and other educational organizations. Each year, the College Board serves

seven million students and their parents, 23,000 high schools, and 3,500 colleges through major programs

and services in college admissions, guidance, assessment, financial aid, enrollment, and teaching and

learning. Among its best-known programs are the SAT®, the PSAT/NMSQT®, and the Advanced Placement

Program® (AP®). The College Board is committed to the principles of excellence and equity, and that

commitment is embodied in all of its programs, services, activities, and concerns.

For further information, visit www.collegeboard.com.

© 2007 The College Board. All rights reserved. College Board, Advanced Placement Program, AP, AP

Central, AP Vertical Teams, Pre-AP, SAT, and the acorn logo are registered trademarks of the College

Board. AP Potential and connect to college success are trademarks owned by the College Board. PSAT/

NMSQT is a registered trademark of the College Board and National Merit Scholarship Corporation. All

other products and services may be trademarks of their respective owners. Visit the College Board on the

Web: www.collegeboard.com.

ii

iii

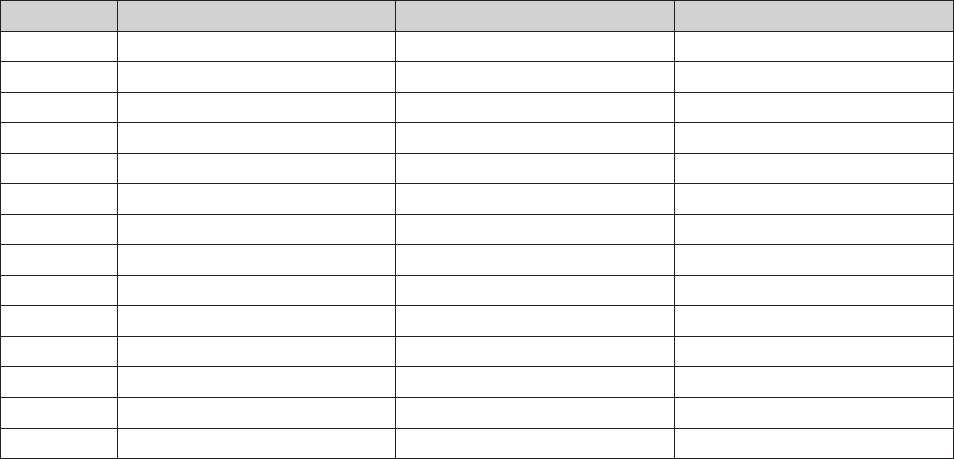

Contents

Welcome Letter from the College Board ............................................................ iv

Equity and Access .....................................................................................................vi

Participating in the AP Course Audit .................................................................. x

Preface ...........................................................................................................................xi

Chapter 1. About AP

®

Human Geography ................................................................ 1

Overview: Past, Present, Future ............................................................................................. 1

Course Description Essentials ................................................................................................ 2

Key Concepts and Skills ........................................................................................................... 4

Chapter 2. Advice for AP Human Geography Teachers ........................................ 11

Basic Start-Up Issues ............................................................................................................. 11

Teachers and Parents ............................................................................................................. 15

Relations with Other Teachers ............................................................................................. 16

Strategies and Suggestions ................................................................................................... 17

Chapter 3. Course Organization ...............................................................................23

Create Your Own Syllabus ..................................................................................................... 23

Sample Syllabus 1 ................................................................................................................... 27

Sample Syllabus 2 ................................................................................................................... 38

Sample Syllabus 3 ................................................................................................................... 51

Sample Syllabus 4 ................................................................................................................... 79

Chapter 4. The AP Exam in Human Geography ....................................................94

Exam Format ........................................................................................................................... 94

Exam Scoring .......................................................................................................................... 95

Taking the Exam ..................................................................................................................... 96

Preparing Students for the AP Exam ................................................................................... 97

After the Exam ...................................................................................................................... 101

AP Grade Reports ................................................................................................................. 101

Using the AP Instructional Planning Report .................................................................... 101

Chapter 5. Resources for Teachers ......................................................................... 102

How to Address Limited Resources ................................................................................... 102

Resources .............................................................................................................................. 103

Professional Development ................................................................................................... 108

Welcome Letter from the College Board

Dear AP® Teacher:

Whether you are a new AP teacher, using this AP Teacher’s Guide to assist in developing a syllabus for the

first AP course you will ever teach, or an experienced AP teacher simply wanting to compare the teaching

strategies you use with those employed by other expert AP teachers, we are confident you will find this

resource valuable. We urge you to make good use of the ideas, advice, classroom strategies, and sample

syllabi contained in this Teacher’s Guide.

You deserve tremendous credit for all that you do to fortify students for college success. The nurturing

environment in which you help your students master a college-level curriculum—a much better atmosphere

for one’s first exposure to college-level expectations than the often large classes in which many first-year

college courses are taught—seems to translate directly into lasting benefits as students head off to college.

An array of research studies, from the classic 1999 U.S. Department of Education study Answers in the

Tool Box to new research from the University of Texas and the University of California, demonstrate

that when students enter high school with equivalent academic abilities and socioeconomic status, those

who develop the content knowledge to demonstrate college-level mastery of an AP Exam (a grade of 3 or

higher) have much higher rates of college completion and have higher grades in college. The 2005 National

Center for Educational Accountability (NCEA) study shows that students who take AP have much higher

college graduation rates than students with the same academic abilities who do not have that valuable AP

experience in high school. Furthermore, a Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS,

formerly known as the Third International Mathematics and Science Study) found that even AP Calculus

students who score a 1 on the AP Exam are significantly outperforming other advanced mathematics

students in the United States, and they compare favorably to students from the top-performing nations in

an international assessment of mathematics achievement. (Visit AP Central® at apcentral.collegeboard.com

for details about these and other AP-related studies.)

For these reasons, the AP teacher plays a significant role in a student’s academic journey. Your AP

classroom may be the only taste of college rigor your students will have before they enter higher education.

It is important to note that such benefits cannot be demonstrated among AP courses that are AP courses in

name only, rather than in quality of content. For AP courses to meaningfully prepare students for college

success, courses must meet standards that enable students to replicate the content of the comparable college

class. Using this AP Teacher’s Guide is one of the keys to ensuring that your AP course is as good as (or

even better than) the course the student would otherwise be taking in college. While the AP Program

does not mandate the use of any one syllabus or textbook and emphasizes that AP teachers should be

granted the creativity and flexibility to develop their own curriculum, it is beneficial for AP teachers to

compare their syllabi not just to the course outline in the official AP Course Description and in chapter 3

of this guide, but also to the syllabi presented on AP Central, to ensure that each course labeled AP meets

the standards of a college-level course. Visit AP Central® at apcentral.collegeboard.com for details about

the AP Course Audit, course-specific Curricular Requirements, and how to submit your syllabus for AP

Course Audit authorization.

As the Advanced Placement Program® continues to experience tremendous growth in the twenty-first

century, it is heartening to see that in every U.S. state and the District of Columbia, a growing proportion

of high school graduates have earned at least one grade of 3 or higher on an AP Exam. In some states, more

iv

v

than 20 percent of graduating seniors have accomplished this goal. The incredible efforts of AP teachers

are paying off, producing ever greater numbers of college-bound seniors who are prepared to succeed in

college. Please accept my admiration and congratulations for all that you are doing and achieving.

Sincerely,

Marcia Wilbur

Director, Curriculum and Content Development

Advanced Placement Program

Welcome Letter

vi

Equity and Access

In the following section, the College Board describes its commitment to achieving equity in the AP

Program.

Why are equitable preparation and inclusion important?

Currently, 40 percent of students entering four-year colleges and universities and 63 percent of students at

two-year institutions require some remedial education. This is a significant concern because a student is

less likely to obtain a bachelor’s degree if he or she has taken one or more remedial courses.

1

Nationwide, secondary school educators are increasingly committed not just to helping students

complete high school but also to helping them develop the habits of mind necessary for managing the

rigors of college. As Educational Leadership reported in 2004:

The dramatic changes taking place in the U.S. economy jeopardize the economic future of students

who leave high school without the problem-solving and communication skills essential to success

in postsecondary education and in the growing number of high-paying jobs in the economy. To

back away from education reforms that help all students master these skills is to give up on the

commitment to equal opportunity for all.

2

Numerous research studies have shown that engaging a student in a rigorous high school curriculum such

as is found in AP courses is one of the best ways that educators can help that student persist and complete

a bachelor’s degree.

3

However, while 57 percent of the class of 2004 in U.S. public high schools enrolled in

higher education in fall 2004, only 13 percent had been boosted with a successful AP experience in high

school.

4

Although AP courses are not the only examples of rigorous curricula, there is still a significant

gap between students with college aspirations and students with adequate high school preparation to fulfill

those aspirations.

Strong correlations exist between AP success and college success.

5

Educators attest that this is partly

because AP enables students to receive a taste of college while still in an environment that provides more

support and resources for students than do typical college courses. Effective AP teachers work closely

with their students, giving them the opportunity to reason, analyze, and understand for themselves. As a

result, AP students frequently find themselves developing new confidence in their academic abilities and

discovering their previously unknown capacities for college studies and academic success.

1. Andrea Venezia, Michael W. Kirst, and Anthony L. Antonio. Betraying the College Dream: How Disconnected K–12 and Postsecondary

Education Systems Undermine Student Aspirations (Palo Alto, Calif.: The Bridge Project, 2003), 8.

2. Frank Levy and Richard J. Murnane, “Education and the Changing Job Market.” Educational Leadership 62 (2) (October 2004): 83.

3. In addition to studies from University of California–Berkeley and the National Center for Educational Accountability (2005), see the

classic study on the subject of rigor and college persistence: Clifford Adelman, Answers in the Tool Box: Academic Intensity, Attendance

Patterns, and Bachelor’s Degree Attainment (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 1999).

4. Advanced Placement Report to the Nation (New York: College Board, 2005).

5. Wayne Camara, “College Persistence, Graduation, and Remediation,” College Board Research Notes (RN-19) (New York: College Board,

2003).

vii

Which students should be encouraged to register

for AP courses?

Any student willing and ready to do the work should be considered for an AP course. The College Board

actively endorses the principles set forth in the following Equity Policy Statement and encourages schools

to support this policy.

The College Board and the Advanced Placement Program encourage teachers, AP Coordinators,

and school administrators to make equitable access a guiding principle for their AP programs. The

College Board is committed to the principle that all students deserve an opportunity to participate in

rigorous and academically challenging courses and programs. All students who are willing to accept

the challenge of a rigorous academic curriculum should be considered for admission to AP courses.

The Board encourages the elimination of barriers that restrict access to AP courses for students from

ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups that have been traditionally underrepresented in the AP

Program. Schools should make every effort to ensure that their AP classes reflect the diversity of their

student population.

The fundamental objective that schools should strive to accomplish is to create a stimulating AP

program that academically challenges students and has the same ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic

demographics as the overall student population in the school. African American and Native American

students are severely underrepresented in AP classrooms nationwide; Latino student participation has

increased tremendously, but in many AP courses Latino students remain underrepresented. To prevent a

willing, motivated student from having the opportunity to engage in AP courses is to deny that student the

possibility of a better future.

Knowing what we know about the impact a rigorous curriculum can have on a student’s future, it is

not enough for us simply to leave it to motivated students to seek out these courses. Instead, we must reach

out to students and encourage them to take on this challenge. With this in mind, there are two factors to

consider when counseling a student regarding an AP opportunity:

1. Student motivation

Many potentially successful AP students would never enroll if the decision were left to their own initiative.

They may not have peers who value rigorous academics, or they may have had prior academic experiences

that damaged their confidence or belief in their college potential. They may simply lack an understanding

of the benefits that such courses can offer them. Accordingly, it is essential that we not gauge a student’s

motivation to take AP until that student has had the opportunity to understand the advantages—not just

the challenges—of such course work.

Educators committed to equity provide all students in a school with an understanding of the benefits of

rigorous curricula. Such educators conduct student assemblies and/or presentations to parents that clearly

describe the advantages of taking an AP course and outline the work expected of students. Perhaps most

important, they have one-on-one conversations with the students in which advantages and expectations are

placed side by side. These educators realize that many students, lacking confidence in their abilities, will

be listening for any indication that they should not take an AP course. Accordingly, such educators, while

frankly describing the amount of homework to be anticipated, also offer words of encouragement and

support, assuring the students that if they are willing to do the work, they are wanted in the course.

The College Board has created a free online tool, AP Potential™, to help educators reach out to

students who previously might not have been considered for participation in an AP course. Drawing upon

data based on correlations between student performance on specific sections of the PSAT/NMSQT® and

Equity and Access

viii

performance on specific AP Exams, AP Potential generates rosters of students at your school who have

a strong likelihood of success in a particular AP course. Schools nationwide have successfully enrolled

many more students in AP than ever before by using these rosters to help students (and their parents)

see themselves as having potential to succeed in college-level studies. For more information, visit http://

appotential.collegeboard.com.

Actively recruiting students for AP and sustaining enrollment can also be enhanced by offering

incentives for both students and teachers. While the College Board does not formally endorse any one

incentive for boosting AP participation, we encourage school administrators to develop policies that will

best serve an overarching goal to expand participation and improve performance in AP courses. When

such incentives are implemented, educators should ensure that quality verification measures such as the AP

Exam are embedded in the program so that courses are rigorous enough to merit the added benefits.

Many schools offer the following incentives for students who enroll in AP:

• Extra weighting of AP course grades when determining class rank

• Full or partial payment of AP Exam fees

• On-site exam administration

Additionally, some schools offer the following incentives for teachers to reward them for their efforts to

include and support traditionally underserved students:

• Extra preparation periods

• Reduced class size

• Reduced duty periods

• Additional classroom funds

• Extra salary

2. Student preparation

Because AP courses should be the equivalent of courses taught in colleges and universities, it is important

that a student be prepared for such rigor. The types of preparation a student should have before entering

an AP course vary from course to course and are described in the official AP Course Description book for

each subject (available as a free download at apcentral.collegeboard.com).

Unfortunately, many schools have developed a set of gatekeeping or screening requirements that go far

beyond what is appropriate to ensure that an individual student has had sufficient preparation to succeed

in an AP course. Schools should make every effort to eliminate the gatekeeping process for AP enrollment.

Because research has not been able to establish meaningful correlations between gatekeeping devices and

actual success on an AP Exam, the College Board strongly discourages the use of the following factors as

thresholds or requirements for admission to an AP course:

• Grade point average

• Grade in a required prerequisite course

• Recommendation from a teacher

Equity and Access

ix

• AP teacher’s discretion

• Standardized test scores

• Course-specific entrance exam or essay

Additionally, schools should be wary of the following concerns regarding the misuse of AP:

• Creating “Pre-AP courses” to establish a limited, exclusive track for access to AP

• Rushing to install AP courses without simultaneously implementing a plan to prepare students and

teachers in lower grades for the rigor of the program

How can I ensure that I am not watering down the quality

of my course as I admit more students?

Students in AP courses should take the AP Exam, which provides an external verification of the extent

to which college-level mastery of an AP course is taking place. While it is likely that the percentage

of students who receive a grade of 3 or higher may dip as more students take the exam, that is not an

indication that the quality of a course is being watered down. Instead of looking at percentages, educators

should be looking at raw numbers, since each number represents an individual student. If the raw number

of students receiving a grade of 3 or higher on the AP Exam is not decreasing as more students take the

exam, there is no indication that the quality of learning in your course has decreased as more students have

enrolled.

What are schools doing to expand access and improve

AP performance?

Districts and schools that successfully improve both participation and performance in AP have

implemented a multipronged approach to expanding an AP program. These schools offer AP as capstone

courses, providing professional development for AP teachers and additional incentives and support for

the teachers and students participating at this top level of the curriculum. The high standards of the AP

courses are used as anchors that influence the 6–12 curriculum from the “top down.” Simultaneously,

these educators are investing in the training of teachers in the pre-AP years and are building a vertically

articulated, sequential curriculum from middle school to high school that culminates in AP courses—a

broad pipeline that prepares students step-by-step for the rigors of AP so that they will have a fair shot at

success in an AP course once they reach that stage. An effective and demanding AP program necessitates

cooperation and communication between high schools and middle schools. Effective teaming among

members of all educational levels ensures rigorous standards for students across years and provides them

with the skills needed to succeed in AP. For more information about Pre-AP® professional development,

including workshops designed to facilitate the creation of AP Vertical Teams® of middle school and high

school teachers, visit AP Central.

Advanced Placement Program

The College Board

Equity and Access

x

Participating in the AP Course Audit

Overview

The AP Course Audit is a collaborative effort among secondary schools, colleges and universities, and the

College Board. For their part, schools deliver college-level instruction to students and complete and return

AP Course Audit materials. Colleges and universities work with the College Board to define elements

common to college courses in each AP subject, help develop materials to support AP teaching, and receive

a roster of schools and their authorized AP courses. The College Board fosters dialogue about the AP

Course Audit requirements and recommendations, and reviews syllabi.

Starting in the 2007-08 academic year, all schools wishing to label a course “AP” on student transcripts,

course listings, or any school publications must complete and return the subject-specific AP Course Audit

form, along with the course syllabus, for all sections of their AP courses. Approximately two months after

submitting AP Course Audit materials, schools will receive a legal agreement authorizing the use of the

“AP” trademark on qualifying courses. Colleges and universities will receive a roster of schools listing the

courses authorized to use the “AP” trademark at each school.

Purpose

College Board member schools at both the secondary and college levels requested an annual AP Course

Audit in order to provide teachers and administrators with clear guidelines on curricular and resource

requirements that must be in place for AP courses and to help colleges and universities better interpret

secondary school courses marked “AP” on students’ transcripts.

The AP Course Audit form identifies common, essential elements of effective college courses, including

subject matter and classroom resources such as college-level textbooks and laboratory equipment. Schools

and individual teachers will continue to develop their own curricula for AP courses they offer—the AP

Course Audit will simply ask them to indicate inclusion of these elements in their AP syllabi or describe

how their courses nonetheless deliver college-level course content.

AP Exam performance is not factored into the AP Course Audit. A program that audited only those

schools with seemingly unsatisfactory exam performance might cause some schools to limit access to

AP courses and exams. In addition, because AP Exams are taken and exam grades reported after college

admissions decisions are already made, AP course participation has become a relevant factor in the college

admissions process. On the AP Course Audit form, teachers and administrators attest that their course

includes elements commonly taught in effective college courses. Colleges and universities reviewing

students’ transcripts can thus be reasonably assured that courses labeled “AP” provide an appropriate level

and range of college-level course content, along with the classroom resources to best deliver that content.

For more information

You should discuss the AP Course Audit with your department head and principal. For more information,

including a timeline, frequently asked questions, and downloadable AP Course Audit forms, visit

apcentral.collegeboard.com/courseaudit.

xi

Preface

What is AP Human Geography? Be prepared to answer that question again and again! AP Human

Geography was established through the efforts of a small, unique group of geographers whose vision was

ahead of their time and destined to influence generations to come. At first, those outside this close-knit

geography community struggled to understand AP Human Geography; but once teachers and students

began to explore the subject together, they came away with a new and exciting view of the world.

To truly understand the world today, it must be viewed within a spatial context. Yet, this perspective

is foreign to most high school students, especially those in North America. In the National Geographic-

Roper 2002 Global Geographic Literacy Survey, only 17 percent of Americans aged 18 to 24 could find

Afghanistan on a map. Only 13 percent could find Iraq or Iran on a map of the Middle East and Asia, and

only 14 percent could locate Israel (this survey can be found on the National Geographic Web site at www.

nationalgeographic.com/geosurvey). Obviously, this speaks volumes about the current state of geographic

education in North America. Our position, simply stated, is that although North Americans seem to have

skirted studying geography in the twentieth century, this behavior must change as we face increasing

globalization in the twenty-first century.

Today, with technology as a driving force, the world has become smaller—for example, North

America’s physical geography no longer presents a barrier to acts of war. The successes and failures of

North America are intertwined with those of the rest of the world, which makes AP Human Geography

an essential course for U.S. students. It helps them view the world from a spatial perspective. This spatial

context, or the where and why things occur, is at the core of the course.

Since its inception, the course has experienced tremendous growth, with teachers and administrators

listening intently to the tune of AP Human Geography. More than 14,000 students took the AP Human

Geography Exam in 2005 (a 35 percent increase over 2004), and that number promises to grow. We

hope that this Teacher’s Guide will foster its continued expansion by providing new teachers of AP

Human Geography with access to the resources they need for the course, and administrators with an

understanding of the course’s intent. Our goal is for new AP Human Geography teachers to be able to pick

up and thumb through this guide, find what they need, and get to work on their course. Features that may

be especially helpful include:

• The course’s goals and topics as stated in the AP Human Geography Course Description

• A discussion of the key concepts and skills in the Course Description

• Advice about creating a syllabus

• Syllabi developed by other human geography instructors

• Tips for preparing students for the AP Human Geography Exam

• Where to find more teacher resources

As you prepare your course, we encourage you to use the resources within this book, as well as those

offered by the College Board on the AP Human Geography Course Home Page on AP Central

xii

(apcentral.collegeboard.com/humangeo). Attend teachers’ workshops, join the electronic discussion group,

talk to your colleagues, and participate in the annual AP Reading. We look forward to meeting each and

every one of you!

Paul Gray Greg Sherwin

A Note from the Authors

Although we were not members of the founding AP Human Geography Development Committee, we both

quickly became involved in the course by attending College Board workshops and applying to become AP

Readers. As high school teachers, we found a network of geographers at both the high school and college

levels who were passionate about this course. With each successive meeting we gained knowledge, received

lesson plan ideas, and made professional connections with educators throughout North America. Teaching

this course has been the most enriching professional development of our careers. We have met some of the

brightest geographers in the country, who have shared their ideas and solicited ours. In turn, we have tried

to share our enthusiasm and experience with as many people as possible by speaking at workshops and

conferences throughout the country.

In addition to participating in every Reading, we are fortunate to have had many other enriching

experiences. We both joined the AP Human Geography Development Committee in 2003 and hold

leadership positions at the Readings. We believe that these experiences have helped us view the course and

exam from many different perspectives. In this book we share with you the insights we have gained over

the years, and our hope is that you, too, will catch the fever.

We are indebted to a number of people who directly and indirectly shared their wisdom, ideas, syllabi,

and experience for this publication. They provided us with direction, which is the essence of geography.

Specifically, we would like to thank Barbara Hildebrant of ETS for her guidance and patience.

We also thank the administrators at Russellville High School in Russellville, Arkansas, and Adlai E.

Stevenson High School in Lincolnshire, Illinois, for their support and encouragement as we embraced this

opportunity to promote geographic education. At Russellville High School, Principal Wesley White and

Assistant Principal Margaret Robinson have been patient and accommodating at every point. At Stevenson

High School, Dr. Timothy Kanold, Superintendent; Mr. Dan Galloway, Principal; Ms. Janet Gonzalez;

Mr. Eric Twadell; and Mr. Chris Franken have all directly supported this opportunity for professional

growth. Both schools understand that the pursuit of educational excellence benefits greatly from

encouraging professional development.

Preface

1

Chapter 1

About AP

®

Human Geography

Overview: Past, Present, Future

Patricia Gober

Arizona State University

Chair, Development Committee

Geography’s name dates back 2,200 years to the Greek scientist Eratosthenes, who combined the words geo,

“the earth,” and graphein, “to write about,” to describe a field devoted to the study of the physical structure

of Earth’s surface and the human activities upon it. Greek, and later Roman, geographers measured Earth,

developed a grid of latitude and longitude, and described patterns of climate, landforms, vegetation, people,

and culture. Geography was also practiced by the ancient Chinese and later by Muslim scholars, who

sought to explore and describe the world in physical and human terms.

The founders of modern geography, Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) and Carl Ritter (1779–1859),

used the flood of new observations about the world generated by the Age of Exploration to produce

massive syntheses describing interconnections among phenomena grouped together in rich diversity on

the surface of Earth. Their work was followed by the Age of Specialization during the nineteenth century

when geography became an independent field of study in universities, first in Germany and then spreading

rapidly to France and other European countries as well as to the United States. The pioneer of American

geography is generally acknowledged to be William Morris Davis, who was appointed instructor of physical

geography at Harvard in 1878; he later founded the Association of American Geographers in 1904.

Geography as a scientific field and course of study waxed and waned in the United States with war,

demographic forces, changing social values, competition from cognate disciplines, and the strength and

orientation of the discipline itself. The number of geography bachelor’s degrees awarded at American

colleges and universities peaked around 1970 as the first wave of the baby boom generation graduated from

college, declining thereafter as students gravitated to fields like biology, geology, and business. At its nadir

in the late 1980s, geography produced only two-thirds of the number of majors it had at its earlier peak.

Geography reemerged as a field of study in higher education in the 1990s with the public’s growing

unease about the state of geographic illiteracy. In addition, public attention shifted to environmental and

international problems, and the discovery of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and other spatial

technologies provided geographers with highly marketable skills and a pipeline to jobs in the burgeoning

information economy. In the midst of geography’s renaissance in the United States, in 1996 the College

Board, a national not-for-profit membership association dedicated to facilitating the transition from high

school to college, added geography to its Advanced Placement Program (AP).

To prepare for the course and exam, state geographic alliances offered training for potential AP

Human Geography teachers. This was no small task, as several generations of Americans lacked the formal

training needed to teach geography. Historians and social studies teachers stepped up to be taught the fine

1

2

Chapter 1

points of college-level geography. This task was particularly challenging because most college instructors

stress geography’s spatial approach and eschew subject matter as an organizing principle for their courses.

Thus, the new cadre of AP Human Geography teachers had to grapple with both the new subject matter

and the idea of geography as a new way of organizing knowledge about the world.

Now, after five years of administering exams and nine years of preparing teachers for and

educating the field about AP Human Geography, we have a clearer picture of what this course means

for geography and of the challenges that lie ahead. AP Human Geography has increased the number of

students who arrive at colleges and universities with high-level geographic training. For the first time

in several generations, geographers report that incoming majors and incoming students know and can

use rudimentary geographic ideas like site versus situation, scale, region, world systems theory, and

the demographic transition. When asked on the 2003 AP Exam, almost 22 percent of the AP Human

Geography students said they had some interest in majoring in geography. If just half of the 22 percent

in the 2003 cohort become geography majors, the discipline will have 800 additional majors, not a trivial

number for a field that typically produces only 4,000 bachelor’s degrees annually.

AP Human Geography’s growth in popularity occurs at a time when government officials, the

scientific community, and the general public increasingly look to geography’s rich tradition of synthetic

studies and knowledge about Earth to address complex, global-scale, environmental, economic, and social

problems. Geography’s new information technologies foster the integration of knowledge about land

use change, urbanization, migration, the spread of disease, human-induced climate change, ecosystem

dynamics, biodiversity, and Earth surface processes. Americans are more aware than ever that their

country’s well-being is linked to global markets, international political developments, and far-flung

environmental issues. There is, in addition, unprecedented interest in building healthy and sustainable

neighborhoods and communities at the local level. This fundamental interest in places, from global to

local, dovetails nicely with geography’s long-standing expertise in exploring, describing, and understanding

Earth’s surface in both physical and human terms. The discipline’s ideas are at the core of America’s

increasingly interdisciplinary scientific enterprise, and its content and spatial perspective are vital to a well-

informed citizenry.

AP Human Geography faces serious challenges as we strive for wider implementation. Geography

is not taught at elite private colleges like Harvard; competition for student enrollment from community

colleges is strong; and many college geographers are not aware of the significance of the course or its exam.

However, AP Human Geography represents an opportunity for geography to rejoin the mainstream of

core university subjects and expand its role in American education. The course exposes the smartest and

most motivated students in the nation to geography, produces more prepared students entering university,

and generates new geography majors. AP Human Geography teachers gain professional development

opportunities, enroll in additional college courses, mix with fellow geographers at the annual summer AP

Reading during which the AP Exams are scored, and become the cheerleaders who will help the discipline

meet its future challenges.

Course Description Essentials

What is Human Geography?

Human geography is the study of where humans and their activities and institutions such as ethnic groups,

cities, and industries are located and why they are there. Human geographers also study the interactions of

humans with their environment and draw on some basic elements of physical geography.

Few people—the general public and students alike—think about their daily experiences in geographic

terms. That is not to say that the general public or our students do not know anything geographic;

3

About AP

®

Human Geography

it is simply that they may not recognize geography when they see it. For example, looking for and thinking

about cultural imprints on the landscape, such as how Hispanic markets or religious institutions affect

their environments, is geography. Locational questions like “Why is the interstate highway where it is?” or

“Why do most Indonesians practice Islam?” are geographic questions with geographic answers. These are

just two examples of how we can use the world around us in classroom lessons.

The AP Human Geography Course

Human Geography was officially introduced into the Advanced Placement Program in the fall of 2000.

The first exam was administered in May 2001, with 3,293 students from 309 high schools accepting the

challenge. AP Human Geography has experienced steady growth since 2001, with 14,139 students from

702 high schools taking the exam in 2005. This growth translates into great news for geography education.

The direction of the course is governed by the AP Human Geography Development Committee, which is

composed of three university professors, three high school teachers, a university professor who serves as the

Chief Reader, and an assessment specialist from ETS. This team also works together to design a rigorous,

comprehensive, and equitable exam.

A number of studies are conducted to ensure that the AP Human Geography course is current, the

exam is valid, and the scores are comparable to college-level grades. Periodically, the committee develops

and administers a curriculum survey that is sent to colleges and universities that include human geography

among their course offerings. The committee reviews the responses and makes revisions to the AP Human

Geography Course Description based on the results. A college comparability study is administered to a

sample of college classes in the initial year of a new AP Exam and again every five years. In this study, a

portion of the AP Exam is administered to college students enrolled in human geography courses. Their

scores are compared with AP scores, and score boundaries are set so that an AP score of 5, for example, is

equivalent to a college grade of A.

Introduction to the Course

The purpose of the AP course in Human Geography is to introduce students to the systematic study of

patterns and processes that have shaped human understanding, use, and alteration of Earth’s surface.

Students employ spatial concepts and landscape analysis to examine human social organization and its

environmental consequences. They also learn about the methods and tools geographers use in their science

and practice.

The particular topics studied in an AP Human Geography course should be considered in light of the

following five college-level goals that build on the National Geography Standards developed in 1994. On

successful completion of the course, the student should be able to:

• Use and think about maps and spatial data. Geography is fundamentally concerned with the ways

in which patterns on Earth’s surface reflect and influence physical and human processes. As such,

maps and spatial data are fundamental to the discipline, and learning to use and think about them

is critical to geographical literacy. The goal is achieved when students learn to use maps and spatial

data to pose and solve problems, and when they learn to think critically about what is revealed—and

what is hidden—in different maps and spatial arrays.

• Understand and interpret the implications of associations among phenomena in places. Geography

looks at the world from a spatial perspective—seeking to understand the changing spatial

organization and material character of Earth’s surface. One of the critical advantages of a spatial

perspective is the attention it focuses on how phenomena are related to one another in particular

places. Thus students should learn not just to recognize and interpret patterns but also to assess the

4

nature and significance of the relationships among phenomena that occur in the same place and to

understand how tastes and values, political regulations, and economic constraints work together to

create particular types of cultural landscapes.

• Recognize and interpret at different scales the relationships among patterns and processes.

Geographical analysis requires a sensitivity to scale—not just as a spatial category but also as a

framework for understanding how events and processes at different scales influence one another.

Thus, students should understand that the phenomena they are studying at one scale (e.g., local)

may well be influenced by developments at other scales (e.g., regional, national, or global). They

should then look at processes operating at multiple scales when seeking explanations of geographic

patterns and arrangements.

• Define regions and evaluate the regionalization process. Geography is concerned not simply with

describing patterns but also with analyzing how these patterns came about and what they mean.

Students should see regions as objects of analysis and exploration and should move beyond just

locating and describing regions to considering how and why they come into being—and what they

reveal about the changing character of the world in which we live.

• Characterize and analyze changing interconnections among places. At the heart of a geographical

perspective is a concern with the ways in which events and processes operating in one place can

influence those operating in other places. Thus, students should view places and patterns not in

isolation, but in terms of their spatial and functional relationship with other places and patterns.

Moreover, they should strive to be aware that those relationships are constantly changing, and they

should understand how and why change occurs.

The course outline was constructed by the inaugural Development Committee and is revised and

updated every two years by the current committee. These revisions and adjustments are made to reflect

changes in the field or to clarify concepts or topics. They also occur as a result of issues related to student

responses to questions on the AP Human Geography Exam. The topic outline, reproduced below, is a

breakdown of these content areas paired with the percentage of the AP Exam multiple-choice questions

that cover each area. Concerted efforts are made by the Development Committee to ensure that AP Human

Geography Exam questions reflect the topics covered in the topic outline.

It is the AP Human Geography teacher’s responsibility to transform students’ daily thinking processes

into speculating, interpreting, and applying everyday experiences with preexisting knowledge through the

lens of geography. If the teacher helps students develop these thought processes, the geographic models,

theories, and concepts will naturally follow. Teachers who work closely with the Course Description will

have an easier time facilitating the development of student thought processes. Therefore, following the

topic outline is vitally important. It should also be noted that teachers should augment their instruction by

using a number of the human geography textbooks that are available in addition to their students’ assigned

classroom text. This practice ensures that students are exposed to the wide array of necessary content areas.

Key Concepts and Skills

The key concepts and skills for the AP Human Geography course are described in the seven content areas

discussed in the Course Description. In summary, these areas are:

1. Geography: Its Nature and Perspectives

2. Population

3. Cultural Patterns and Processes

Chapter 1

5

4. Political Organization of Space

5. Agricultural and Rural Land Use

6. Industrialization and Economic Development

7. Cities and Urban Land Use

Topics

Any teacher, and especially new AP Human Geography teachers, should spend a great deal of planning

time becoming familiar with the topics outlined in the Course Description. A fundamental piece of

the puzzle is how to think about geography. Geography sits at the junction of social science, physical

science, humanities, and technology. It is essential to look at the topic outline and see geography as a

way of thinking. For example, to think geographically, ask yourself, “Can I map it? What are the spatial

implications? How are places affected?” The following annotated list of the seven content areas in the

topic outline is intended to give new teachers ideas for ways to approach the teaching of these geographical

concepts and skills.

I. Geography: Its Nature and Perspectives

Although this section of the course is composed of introductory material and accounts for only 5 to

10 percent of the AP Exam, it can be challenging for AP Human Geography teachers because it contains

important geographic concepts: due to its definitional nature, the new geography teacher may have

difficulty presenting this material in a manner that students can easily grasp. However, the concepts

of location, space, place, scale, pattern, regionalization, and globalization are fundamental to the study

of geography, and this section of the course is compulsory. Subsequent sections will provide many

opportunities to apply these tools and concepts, thus reinforcing students’ understanding of them.

Students learn how to use and interpret maps and to understand the role of mental mapping.

II. Population

If a poll were taken among geography teachers, the population section would probably garner the course’s

“most popular” award. Many teachers feel particularly comfortable teaching population issues because

they cut across many disciplines. The population section allows students to revisit previous lessons

about slavery, migration, or environmental hazards, for example, but this time from a geographical

perspective. The process of migration can be demonstrated by using students’ own residential histories or

neighborhoods. The interconnections between population and other geographic topics enhance students’

understanding of today’s world. Web sites that offer teachers and students current population data provide

opportunities for students to map and/or graph population trends and issues.

III. Cultural Patterns and Processes

The geography of culture is rich with opportunities for students to explore the world on many different

scales, from local to global. Schools and communities that are ethnically, religiously, and linguistically

diverse offer many occasions for teaching about culture. There are many ways to make the cultural material

in the course come to life for students—teachers can identify for students examples of folk culture in the

local community, or use photographs to illustrate the homogeneity of the landscape caused by popular

culture. They can check signage and phone books for evidence of past migrations through the local area, or

they can visit local religious institutions. Teachers in a rural setting or a small town might want to partner

with a local arts organization or historical preservation group. The key is to use local cultural dynamics to

illustrate the concepts in the topic outline.

About AP

®

Human Geography

6

IV. Political Organization of Space

This unit allows teachers to discuss political forces that strengthen and weaken states as players on the

world stage. Teaching the political organization of space may provide some challenges for AP Human

Geography teachers because students may need to relearn the meanings of terms like nation and state.

Although colonialism, imperialism, gerrymandering, alliances, and devolution are all topics with which

students may have had some experience, those with a history background are often confused by the

differences between a nation, a state, and a nation-state, as used in geography. This part of the course

focuses on political units above, below, and beyond the state: regional alliances like the EU and NAFTA,

international cooperation, and local issues related to electoral districts, municipal boundaries, and ethnic

territories. The key to this unit mirrors that of all of the others: helping students understand these ideas

and concepts in a spatial context.

V. Agricultural and Rural Land Use

Most teachers have little or no training in teaching about agriculture, but with a bit of effort and some

creative field trips, teachers and students can become well acquainted with the geography of agriculture.

Agricultural models and movements come alive with local examples and good textbook resources. Of

course, the Web offers a great deal of information useful for instructional purposes. Where possible,

teachers should try to visit local industries that process agricultural products. They can cultivate fruitful

relationships with key people in these industries, which in turn will provide new opportunities to help

students connect models with the real world. Topics in this unit explore four basic themes: (1) the origin

and diffusion of agriculture, (2) its characteristics in different parts of the world, (3) rural land use

and settlement patterns associated with major agricultural systems, and (4) characteristics of modern

agribusiness. All of these themes emphasize concepts and models that help explain diffusion, agricultural

location (the von Thünen model), and culture.

VI. Industrialization and Economic Development

This section centers on the spatial aspects of economic systems and the geography of industrialization and

development. The concepts and models in this unit are more theoretical in nature and provide significant

challenges for students. Most high school students have a limited understanding of supply and demand, bid

rent, and other economic ideas. Students need to understand how models of economic development like

Rostow’s stages of economic growth and Wallerstein’s World Systems Theory help to explain why the world

is described as being divided into a well-developed core and a less-developed periphery. Teachers will need

to strive to connect such theories to the real world, using hands-on approaches that are essential to helping

students grasp this demanding material. This will provide them with the tools they need to understand

how models of economic development explain concepts of core and periphery, globalization, and the new

international division of labor. Students also study the impact of deindustrialization, the disaggregation of

production, and the rise of consumption and leisure activities.

VII. Cities and Urban Land Use

Students who live in an urbanized area obviously find the urban material easier to “see.” But students in

small towns can connect with urban models and concepts if their teacher downsizes the models to fit their

locale. For example, the teacher can talk about bid rent and the central business district (CBD) of a small

town. Students can compare the cost of land at the CBD and at the outskirts of town. Teachers should go

on a walking tour of their town or city with students. There are geographic treasures to find regardless of

size.

Chapter 1

7

The Topic Outline

The topic outline below is the skeleton around which each teacher fleshes out the course through the use

of textbooks, Web sites, journals, observations, and possibly fieldwork or class trips. Teachers should be

sure to note the percentage goals included in the topic outline for each of the seven content areas on the

multiple-choice section of the AP Exam. These percentages are approximate but provide guidance in

deciding how much class time to spend on each content area. Note that the topic outline is included as a

guide to topics in human geography and is not an exhaustive list of topics. The topics are updated every

two years.

Percentage Goals for Exam

Content Area (Multiple-Choice Section)

I. Geography: Its Nature and Perspectives 5–10%

A. Geography as a field of inquiry

B. Evolution of key geographical concepts and models associated with notable geographers

C. Key concepts underlying the geographical perspective: location, space, place, scale, pattern,

regionalization, and globalization

D. Key geographical skills

1. How to use and think about maps and spatial data

2. How to understand and interpret the implications of associations among phenomena in

places

3. How to recognize and interpret at different scales the relationships among patterns and

processes

4. How to define regions and evaluate the regionalization process

5. How to characterize and analyze changing interconnections among places

E. New geographic technologies, such as GIS and GPS

F. Sources of geographical ideas and data: the field, census data

II. Population 13–17%

A. Geographical analysis of population

1. Density, distribution, and scale

2. Consequences of various densities and distributions

3. Patterns of composition: age, sex, race, and ethnicity

4. Population and natural hazards: past, present, and future

B. Population growth and decline over time and space

1. Historical trends and projections for the future

2. Theories of population growth including the Demographic Model

3. Patterns of fertility, mortality, and health

4. Regional variations of demographic transitions

5. Effects of population policies

About AP

®

Human Geography

8

C. Population movement

1. Push and pull factors

2. Major voluntary and involuntary migrations at different scales

3. Migration selectivity

4. Short-term, local movements, and activity space

III. Cultural Patterns and Processes 13–17%

A. Concepts of culture

1. Traits

2. Diffusion

3. Acculturation

4. Cultural regions

B. Cultural differences

1. Language

2. Religion

3. Ethnicity

4. Gender

5. Popular and folk culture

C. Environmental impact of cultural attitudes and practices

D. Cultural landscapes and cultural identity

1. Values and preferences

2. Symbolic landscapes and sense of place

IV. Political Organization of Space 13–17%

A. Territorial dimensions of politics

1. The concept of territoriality

2. The nature and meaning of boundaries

3. Influences of boundaries on identity, interaction, and exchange

B. Evolution of the contemporary political pattern

1. The nation-state concept

2. Colonialism and imperialism

3. Federal and unitary states

C. Challenges to inherited political–territorial arrangements

1. Changing nature of sovereignty

2. Fragmentation, unification, alliance

3. Spatial relationships between political patterns and patterns of ethnicity, economy,

and environment

4. Electoral geography, including gerrymandering

Chapter 1

9

V. Agricultural and Rural Land Use 13–17%

A. Development and diffusion of agriculture

1. Neolithic Agricultural Revolution

2. Second Agricultural Revolution

B. Major agricultural production regions

1. Agricultural systems associated with major bioclimatic zones

2. Variations within major zones and effects of markets

3. Linkages and flows among regions of food production and consumption

C. Rural land use and settlement patterns

1. Models of agricultural land use, including von Thünen’s model

2. Settlement patterns associated with major agriculture types

D. Modern commercial agriculture

1. Third Agricultural Revolution

2. Green Revolution

3. Biotechnology

4. Spatial organization and diffusion of industrial agriculture

5. Future food supplies and environmental impacts of agriculture

VI. Industrialization and Economic Development 13–17%

A. Key concepts in industrialization and development

B. Growth and diffusion of industrialization

1. The changing roles of energy and technology

2. Industrial Revolution

3. Evolution of economic cores and peripheries

4. Geographic critiques of models of economic localization (i.e., land rent, comparative

costs of transportation), industrial location, economic development, and world systems

C. Contemporary patterns and impacts of industrialization and development

1. Spatial organization of the world economy

2. Variations in levels of development

3. Deindustrialization and economic restructuring

4. Pollution, health, and quality of life

5. Industrialization, environmental change, and sustainability

6. Local development initiatives: government policies

VII. Cities and Urban Land Use 13–17%

A. Definitions of urbanism

B. Origin and evolution of cities

1. Historical patterns of urbanization

2. Rural–urban migration and urban growth

3. Global cities and megacities

4. Models of urban systems

About AP

®

Human Geography

10

C. Functional character of contemporary cities

1. Changing employment mix

2. Changing demographic and social structures

D. Built environment and social space

1. Comparative models of internal city structure

2. Transportation and infrastructure

3. Political organization of urban areas

4. Urban planning and design

5. Patterns of race, ethnicity, gender, and class

6. Uneven development, ghettoization, and gentrification

7. Impacts of suburbanization and edge cities

Chapter 1

11

Chapter 2

Advice for AP Human

Geography Teachers

Every teacher knows that developing and teaching a new course can be a daunting task. Developing an

AP course presents several additional challenges, and AP Human Geography is no exception. However,

committed teachers can be successful in their efforts—and once begun, teachers will find that AP Human

Geography is a special course, one that students will sell to their younger peers because the course is simply

that good.

What makes AP Human Geography so different? Put simply, geographers view everything as

geography and geography as everything! Human geography covers diverse topics that are of interest to

most students. It delves into population, religion, urban development, agriculture, economics, politics,

disease, urban planning, and many other interesting topics that are studied through a geographic lens.

Teachers who take on the course often find that it is their most exciting and enthusiastic class. But

before getting started, several issues must be addressed to ensure success for both teachers and students.

Basic Start-Up Issues

Fitting AP Human Geography into the Curriculum

Unfortunately, most states do not require students to take any geography after the seventh grade. This

puts the prospective AP Human Geography teacher in the position of having to become an advocate and a

salesperson for the course. One of the teacher’s most difficult but vital tasks will be finding a place in the

school’s curriculum for the course.

Some teachers wedge AP Human Geography into the curriculum by demonstrating the course’s

value from a social sciences perspective. Others explain how this course fits into their school’s existing

requirements for graduation. In many cases, the course is taught as an elective. Although every teacher

knows it can be difficult to get students to sign up for new and unknown electives, selling this course as

an especially interesting elective is not the impossible task it might seem. In many schools in which it is

offered as an elective, AP Human Geography has become the most popular course in the social sciences

department. In fact, in some schools AP Human Geography outdraws AP U.S. History and AP World

History! AP Human Geography is a course that many students will want to take, given a couple of years of

successful recruiting and teaching.

Educate your school’s administrators and counselors about the value of geography in an ever-changing

and globalizing world. Geography becomes real and exciting through application and analysis. Real-world

applications allow teachers to show to administrators and parents, as well as students, that everything is

geography and geography is everything. Prospective AP Human Geography teachers can demonstrate

12

the linkages the course can provide to any social science curriculum as well as the possible community

resources that can be tapped for added context.

Most towns and all cities have a planning commission and a sewage treatment facility, the kinds of

places where concepts of urban geography come alive. Is there a museum, church, mosque, synagogue,

or Hispanic market in your area? If so, opportunities for applying the concepts of cultural geography are

readily available. Do students live in a farming area or near agricultural processing plants? Great! They can

apply the models and theories of agricultural geography to real cases. You get the idea. No matter where

one teaches, there are wonderful opportunities to apply geography. All it takes is some imagination to

demonstrate to administrators and parents that AP Human Geography is a special course and deserves a

seat at the curriculum table.

AP Human Geography is one of the most important courses students can take in their high school careers

because it prepares them to succeed in the real world. This course goes beyond rote memorization and forces

students to be analytical and evaluate problems that relate to themselves. Use your communities’ particular

issues to light the spark in your students. Push them to think spatially through maps, theories, and models.

This is a skill that employers are thirsting for. Teach the individual units but interweave them with discussions

of world issues. This course, by its nature, connects real-life issues with theories. Use outside resources

like the Internet and field trips to reinforce key points. Keep time constraints in mind but know that students

are benefiting tremendously. Find the balance between teaching to the test and learning for learning’s sake.

Geography is the key to our future. Give your students the power to open the door.

—Kelly Swanson, Johnson Senior High School,

St. Paul, Minnesota

Any teacher who truly desires to have a successful AP Human Geography course must be an

enthusiastic recruiter. Recruitment can take several forms. You can design a colorful brochure that

details what the course offers in terms of content and skills. Aim the brochure at students and parents

or guardians, with students being the primary consumers. Another approach is to create, advertise,

and then present the course at an AP Social Sciences Parent Night. Coordinating this meeting with the

other teachers in your department will help you get started with course planning while learning valuable

information from your colleagues. The best outcome of an AP Parent Night is that parents get reliable

information about the rigors of AP work and the value of the AP Human Geography course. As a result,

you will establish important communication lines with parents. Working with your school counselors is yet

another way to ensure success with a new course. Often it is a counselor who suggests that a student take a

particular course. When counselors understand AP Human Geography and the benefits it offers, they can

direct students into the course.

A typical AP Human Geography student discussion group at Russellville High School in Russellville, Arkansas.

Chapter 2

13

If your school has few or no AP courses, you’ll first have to educate everyone about the AP Program.

To impart the necessary information about the AP Program in general and the AP Human Geography

course in particular, talk with students (and counselors) at feeder schools. The students coming to your

school may not know about the opportunities the AP Program offers. If they do not know about AP, they

certainly will not know about AP Human Geography. Just remember, it is the teacher’s enthusiasm and

determination that shapes the success of the AP Human Geography course.

Starting the Course

Teachers should be ready to address administrators’ and counselors’ concerns about beginning a course

that does not directly fit into the curriculum and therefore may have low enrollment. Many schools have

scheduling policies that do not allow a course to be taught with an enrollment of fewer than 10 students.

To get the course off the ground, then, it may be necessary to ask your administrators and/or counselors

for a three-year waiver of this policy. Explain to administrators that getting an AP Human Geography

course started takes more time than it does for other new AP courses, and that the teacher needs greater

flexibility in order to build up the course’s enrollment. For example, teachers and administrators should

not be discouraged if only five students sign up the first year the course is offered. For many schools, the

tipping point seems to be between the second and third years. If the teacher is willing to lay the proper

groundwork and be an enthusiastic recruiter, enrollment in the course will rise.

I obtained a waiver from my district’s Secondary Curriculum Coordinator to begin an AP Human Geography

course and teach it with fewer than 10 students for three years. The first year I had 7 students sign up for the

course. The second year 9 students took the course. The third year 33 students took the course. Sixty-nine

students took the course the fourth year, and over 70 are signed up for the fifth year.

—Paul Gray, Russellville High School,

Russellville, Arkansas

The AP Coordinator

The AP Coordinator takes primary responsibility for organizing and administering the AP program at a

given school. The Coordinator may be a full- or part-time administrator or counselor, or a faculty member

who is not teaching an AP course. The Coordinator agrees to maintain the security of exams when

managing the receipt, distribution, administration, and return of AP Exam materials as outlined by the

College Board and the AP Program. To avoid any perceived conflict of interest, an AP Coordinator cannot

be involved in the handling of any exam materials that an immediate family or household member may

take. Questions about exam fees and security, dates and deadlines, giving exams to students with special

needs, and exam-specific policies should be directed to your AP Coordinator.

One or Two Semesters?

The question of whether the course should be taught in one semester or two is best answered by the

response, “It depends.” Block scheduling, teacher training, previous geography offerings, the age of the

students, and state mandates are just some of the possible considerations the AP Human Geography

teacher must take into account before designing the course.

Advice for AP Human Geography Teachers

14

Teaching AP Human Geography on a block schedule requires a flexible approach to creating the syllabus.

In theory, block scheduling allows teachers the time to develop more in-depth lesson plans. The 80-minute

periods are great—there is time for at least two separate activities during each day of teaching. This is critical

because each unit must be taught in approximately two to three weeks in order to meet the requirements of the

course.

The gap between the course’s end and the exam date is a reality that must be addressed so that students can

perform successfully on the exam. Unfortunately, the reality of block scheduling is that missing one class for

other school activities means the loss of more than one day of teaching. If the option is available, it is best to

teach the course in the first semester, although extra sessions throughout the second semester will need to be

scheduled to build up to the AP Exam in May. If the course is scheduled for the second semester, over a month

of vital instructional time is lost because of the timing of the exam. In this case, the course must be carefully

planned to cover all of the material that is necessary for the exam.

—Kelly Swanson, Johnson Senior High School,

St. Paul, Minnesota

I am teaching AP Human Geography on a block schedule and find that it works best when I divide the period

in half. In the first half, I introduce the topic (e.g., Language) through lecture and discussion. During the second

half of the period, students complete an activity that reinforces the lecture topic. For example, I have two

activities for the language section: an in-class supplemental reading on languages followed by a discussion

period, and data collection, with the creation of a choropleth map depicting the word used for soda pop in

different regions of the United States. Splitting the class period in half seems to minimize “down time” that

a block schedule can engender. Any leftover time (usually five minutes or less) is given to students to begin

reading their homework assignment on the next topic.

—Summer Copeland, Lyman High School,

Longwood, Florida

Almost everyone agrees that the yearlong approach is preferable to a single-semester one, and more

advantageous overall. AP Human Geography is a challenging course with concepts that will be new to

most students. The more time that is available to present the material, the better it will be for both teachers

and students. Advantages to the yearlong approach to teaching AP Human Geography include more

available time to:

• introduce, explain, and have students master complex geographic models and concepts;

• include field trips, some hands-on projects, and possibly geographic research; and

• begin intensive review sessions for the AP Exam (teachers using a yearlong format will be able to

finish the course two to three weeks before the AP Exam in May).

A school may have a schedule, however, that permits only the one-semester format. Although many

veteran teachers will testify that the one-semester approach is extremely taxing even under the best

conditions, it can work under the following circumstances:

• the teacher has at least one degree in geography (or an extremely strong background in the

discipline);

• geography is mandated in the state at several levels, with AP Human Geography being the

culminating course;

Chapter 2

15

• the students are juniors and seniors (preferably only seniors) and/or highly motivated sophomores; or

• the schedule and/or administrators dictate that AP Human Geography must be taught in one

semester.

Let us assume that the fourth bullet point above is true. How can a beginning AP Human Geography

teacher successfully teach the course in one semester? First, be comforted by the fact that many veteran AP

Human Geography colleagues started the course under identical circumstances. Seek them out and glean

from them every available resource, technique, and piece of advice. Second, carefully read this Teacher’s

Guide and implement the strategies that appeal to you. Know that condensing a two-semester syllabus

into one semester is common practice, as is scheduling after-school, evening, or weekend AP Exam study

sessions in the spring. Third, make sure to get as much training as possible. Finally, remember that the

teacher is the most important factor in determining whether an AP Human Geography course will survive

its first few years. A teacher’s enthusiasm, determination, and willingness to be a “geo-evangelist” can make

up for deficits in other areas.

Teachers and Parents

Parents and guardians are the most valuable partners and resources for any AP teacher. Parents want to

provide the support that translates into success for their AP student. The key to a successful parent–teacher

partnership is information and communication. The normal communication channels of phone calls,

conferences, and notes are effective, but other methods can provide even more opportunities and benefits.

Automated Phone Messaging Systems

If your school has an automated phone system, find out how you can use this valuable tool. The AP Human