The evolution of the

medical workforce

THE FUTURE OF THE MEDICAL WORKFORCE 32 ANZ—MELBOURNE INSTITUTE HEALTH SECTOR REPORT

Contents

Background and key findings 4

Growth in the medical workforce 6

Is self-suciency realistic? 8

Not enough GPs, too many

non-GP specialists? 9

Doctor’s earnings 10

Bulk billing and fees rising 11

Telehealth use falling 12

Conclusions 17

References 18

4 ANZ—MELBOURNE INSTITUTE HEALTH SECTOR REPORT THE EVOLUTION OF THE MEDICAL WORKFORCE 5

BACKGROUND

During the past 18 months, many doctors have

experienced significant changes to their workload

and practice patterns. Most successfully pivoted their

working practices and business models to adjust to the

pandemic, and many have bounced back but recognise

that much has changed. Though Australia has been less

aected by COVID-19 than other countries, many issues

have been raised about flexibility and adaptation of

health care providers to ensure the appropriate supply

of medical care in ‘business as usual’ times, as well as

during future pandemics and natural disasters.

This report examines some key trends for the medical

workforce after around 20 years of expansion in supply

(Geen, 2014). In an era of increased medical workforce

supply, it is essential to ensure that additional doctors

are used to meet population needs for healthcare,

rather than reinforcing a paradox of overtreatment

and overdiagnosis for some of the population existing

alongside undertreatment for those most in need. This

includes trying to get the ‘right’ balance of the medical

workforce between urban and rural areas, between

specialties, and between generalism and specialised

care. Flexibility and adaptation are central to this, and

are key ongoing themes of the new National Medical

Workforce Strategy (Department of Health, 2019).

The Strategy has recognised the problems with the

current way the medical workforce is trained, organised

and funded, and how these diculties significantly

reduce the ability of the medical workforce to meet

population needs for healthcare.

KEY FINDINGS

• The number of doctors continues to grow, with the

number of non-GP specialists growing faster than

the number of GPs.

• Higher numbers of doctors in training and non-

GP specialists are beginning to spill over into rural

areas. More doctors are working outside of major

metropolitan areas. Growth in the number of doctors

outside major metropolitan areas outstrips the growth

inside these areas for all doctors except for GPs. This is

despite decades of policy targeted to persuade more

GPs to go rural.

• Spillovers into rural and regional areas could be

caused by increased supply and competition pushing

doctors out of major cities. There has also been

increased investment in regional training of GPs and

non-GP specialists and other policies that help pull

doctors away from major cities. In addition, spillovers

could be caused by existing non-GP specialists

spending more time in public hospitals reducing job

opportunities for newly qualified non-GP specialists in

major cities.

• A stated national policy objective is self-suciency

of the medical workforce, but the number of

international medical graduates (GPs and non-GP

specialists) continued to grow faster than the number

of domestically trained GPs and non-GP specialists

until the end of 2019. COVID-19, however, has sharply

reduced total immigration into Australia, though

medical practitioners remain on the new Priority

Migration Skilled Occupation List introduced in

late 2020.

• Specialty choice remains an issue, as applications for

GP training places fall and the number of specialists

continues to grow faster than GPs. Non-GP specialists

earned almost twice as much as GPs, with their

earnings growing twice as fast such that the gap

between GP and non-GP specialist earnings has

widened over time, probably aided by the Medicare

Fee Freeze. The earnings gap is likely to widen

further as there are no specific national policies to

address this.

• Annual fee revenue per doctor has been falling over

time. The most likely reason is that the number of GPs

and non-GP specialists (supply) has been growing

leading to more competition, whilst the number of

patients per doctor (demand) has been falling even

as the population increases. The Medicare fee freeze

and fall in growth of private hospital care could have

contributed to this.

• Whilst fee revenue has been falling, doctors’ self-

reported annual earnings (after practice costs and

before tax) have been increasing. This suggests that

doctors are managing to maintain their take home

pay by either reducing practice costs per doctor or

increasing income in other ways.

• Doctors have also been slowly changing their billing

patterns over time, with higher rates of bulk billing,

especially for non-GP specialists, as well as higher

fees charged for non-bulk billed services. This is likely

to reflect lower fees and more bulk billing for less

auent patients balanced out by higher fees for more

auent patients.

• Telehealth consultations continue to be used and

funding has been extended to the end of 2021,

but their use overall has been slowly falling. Video

consultations are still used much less than

telephone, though are more likely to be used by

non-GP specialists.

• For GPs, the proportion of attendances using

telehealth for GP Mental Health Plans and Chronic

Disease Management Plans are slightly lower than

for usual GP visits, suggesting no additional need

for telehealth for these specific patient populations.

Level A (short) telehealth consultations remain high

and are much more likely to be phone calls. Medicare

telehealth funding is expected to be continued in the

longer term where there is a need from patients, and

higher rebates for video consultations could help to

increase their use by GPs. However, there remains little

evidence on the appropriateness of telehealth.

Medical practitioners have continued to adapt to

significant increases in medical workforce supply as

well as COVID-19. Increased supply leads to more

competition, and the eects of this are beginning to be

seen as doctors spill over into rural and regional areas

and increasing pressure on fee revenue. But after 20

years, issues such as specialty choice have not been

addressed, rural practice needs continued support,

and the benefits of telehealth need to be better utilised.

6 ANZ—MELBOURNE INSTITUTE HEALTH SECTOR REPORT

ignores the costs of a general expansion in the doctor

supply and ignores the strong preferences of most

doctors to remain in major cities and auent areas that

we have found in our research (McIsaac et al., 2015;

Scott et al., 2013).

It has been dicult to implement the required

complementary policies to change career pathways,

medical training, and models of care that encourage

doctors to work in underserved areas. Though much has

been done including financial incentives, rural pathways

for GPs, as well as regional training hubs for non-GP

specialists, many of the issues have not been solved

and there remains uncertainty about their eectiveness.

There are currently no national policies to encourage

doctors to practice in disadvantaged areas within

major cities.

There is some evidence of an increase in the proportion

of doctors working outside of major cities. In 2019,

79,543 doctors were working in major cities in Australia,

compared to 23,470 outside of major cities. Since 2013,

the number of doctors working outside of major cities

has grown by 4.8 per cent - faster than the growth in the

number of doctors in major cities of 3.9 per cent over

the same period. This has contributed to a slight increase

in the percentage of all doctors working outside major

cities from 22 per cent in 2013 to 22.8 per cent in 2019.

Figure 2 shows the average annual growth in the number

of doctors working outside of major cities compared to

the growth of those in major cities. For all doctors except

GPs, growth in the number of doctors is faster outside of

major cities. For hospital non-specialists and specialists

in training, this provides evidence that training has been

successfully shifted outside of main metropolitan

tertiary hospitals which have a fixed capacity and

may have been unable to absorb the sharp increase in

medical graduates. National policies have also included

training doctors in private hospitals. The growth in the

numbers of non-GP specialists outside of capital cities

is more surprising and could reflect an oversupply of

doctors in major cities beginning to spill over into large

regional towns.

However, despite the eorts by policy makers to

persuade more GPs to go rural, the per centage of GPs

outside of major cities areas has fallen slightly from 29.2

per cent in 2013 to 28.7 per cent in 2019. This is because

the growth in the number of GPs in major cities (3.9 per

cent between 2013 and 2019) has been slightly higher

than the growth in the number of GPs outside of major

cities (3.4 per cent per year between 2013 and 2019).

This is not necessarily evidence of policy failure as it

could be that without these policies, the situation might

be much worse.

Though the number of GPs is growing, it is their

distribution that matters most to improving access to

populations most in need. Some policies have been

introduced only recently, such as rural generalist training

pathways and will not yet show an eect, but other

policies such as financial incentives have been in place

for a long time. Evidence shows that financial incentives

may not be eective (Scott et al., 2013), or if they are it is

only for GP Registrars who are the most mobile (Yong et

al., 2018) whilst financial support for locum relief may be

particularly eective (Li et al., 2014).

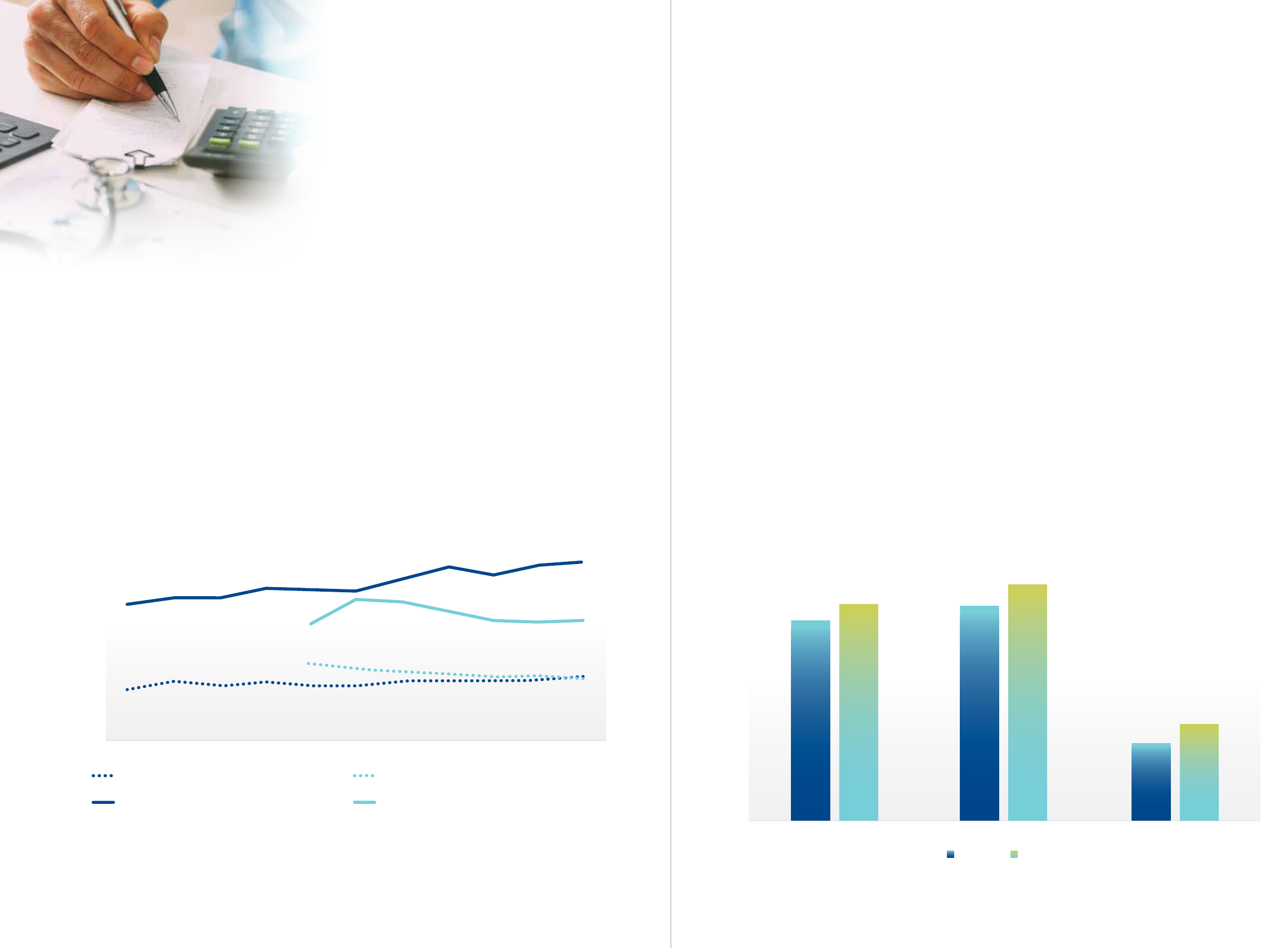

GROWTH IN THE MEDICAL WORKFORCE

For the first time, the number of doctors in clinical

practice exceeded 100,000 in 2019 (Figure 1), a growth

of 3.9 per cent over the 5 years 2014 to 2019 whilst

population growth was 1.6 per cent per year. The number

of hospital non-specialists, including interns and doctors

in training who have yet to enter specialty training,

exhibited the fastest growth of 5.5 per cent per year

over the same period.

The number of non-GP specialists continues to grow

faster (4.5 per cent per year) than the number of GPs

(3.5 per cent per year). In 2014 there were 3,143 more

specialists than GPs, and this grew to 5,283 in 2019.

This is despite the growing burden of chronic disease

and a recognised need for more generalist doctors

(with a wide range of skills across dierent disease

areas) inside, but especially outside, of major cities.

At this aggregate level, there is no evidence of increasing

generalism in the Australian medical workforce – indeed

the contrary seems to be the case.

More doctors outside of cities

The proposed solution to medical workforce

maldistribution was thought to be ‘flooding the market’

to achieve self-suciency, with a more than doubling

of medical graduates from the early 2000s, fuelling the

growth of doctor numbers in Figure 1 (Australian Health

Ministers Council, 2004). The expectation was that

excess doctors in overserved areas would eventually spill

over into underserved rural and regional areas and lower

socioeconomic status areas in major cities. Such a policy

2005

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

Number of doctors

Years

Non-GP specialists

Figure 1

Figure 2

GPs Doctors-in-training

35,000

40,000

45,000

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

2.92%

6.50%

4.27%

6.07%

4.44%

5.26%

3.88%

3.37%

Non-GP specialists

Major cities Outside major cities

Specialist-in-training Hospital non-specialists GPs

Figure 1. Number of doctors 2005 to 2019 (linear projections to 2021).

2005

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

Number of doctors

Years

Non-GP specialists

Figure 1

Figure 2

GPs Doctors-in-training

35,000

40,000

45,000

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

2.92%

6.50%

4.27%

6.07%

4.44%

5.26%

3.88%

3.37%

Non-GP specialists

Major cities Outside major cities

Specialist-in-training Hospital non-specialists GPs

Figure 2. Average annual percentage increase in the number of doctors working

outside and inside major cities (between 2013 to 2019).

Source: Health Workforce Planning Tool, Department of Health.

Source: Health Workforce Planning Tool, Department of Health. Major cities defined as Modified Monash Model 1.

Figure 5

Figure 6

74.3%

80.1%

79.8%

87.7%

Non-GP specialistsGPsAll Medicare

35.6%

28.7%

0.105

0.131

0.079

If income increased by $50,000

If procedural work increased from ‘none’ to ‘some’

If opportunities for academic work increased from

‘poor’ to ‘average’

2009-10 2019-20

domestic supply, many employers - including public

hospitals as well as medical practices – wish to maintain

flexibility in hiring IMGs to fill gaps. The fall in the

number and percentage of junior doctors who are IMGs

should eventually flow through to the qualified medical

workforce in the future provided the number of new

IMGs does not increase.

COVID-19 might have at least temporarily reduced

the pre-COVID-19 increase in IMGs, whilst overall

immigration to Australia fell by around 90 per cent

in 2020. However, doctors have been added to the

Priority Migration Skilled Occupation List since late

2020 , suggesting a continuing reliance on IMGs to fill

gaps in supply. It remains to be seen whether Australia’s

reputation as a COVID free country continues to increase

immigration to Australia in the future once international

travel restrictions are gradually lifted.

IS SELF-SUFFICIENCY REALISTIC?

A key aspect of medical workforce distribution policy

over the past 15-20 years has been self-suciency

(O’Sullivan et al., 2019). This includes not only increasing

domestic supply but at the same time reducing the

immigration of doctors from other countries to ensure

training positions and jobs are available for the increased

domestic supply.

In 2018 changes to the temporary skilled visa

program made it more dicult for visa holders to stay

permanently in Australia. In 2019, additional policies as

part of the ‘Stronger Rural Health Strategy’ included

proposals to reduce immigration intakes for GPs and

resident medical ocers (primarily working in hospitals

in major cities). This was intended to help create

opportunities for locally trained doctors in training to

practice in rural and regional areas. However, a new

Priority Migration Skilled Occupation List introduced

in 2020 during COVID-19 seems to have reversed this

policy as it includes GPs, Resident Medical Ocers,

Psychiatrists, and Other Medical Practitioners.

The reliance on international medical graduates (IMGs)

in rural and regional areas is likely to continue as long as

domestically trained doctors have strong preferences

to work in major cities. Still, COVID-19 might have

unexpectedly accelerated the policy of self-suciency

because of restrictions on international travel reducing

immigration and leaving ‘space’ for domestically trained

doctors. However, this could also potentially make it

more dicult to recruit doctors to rural and regional

areas if city doctors do not want to move.

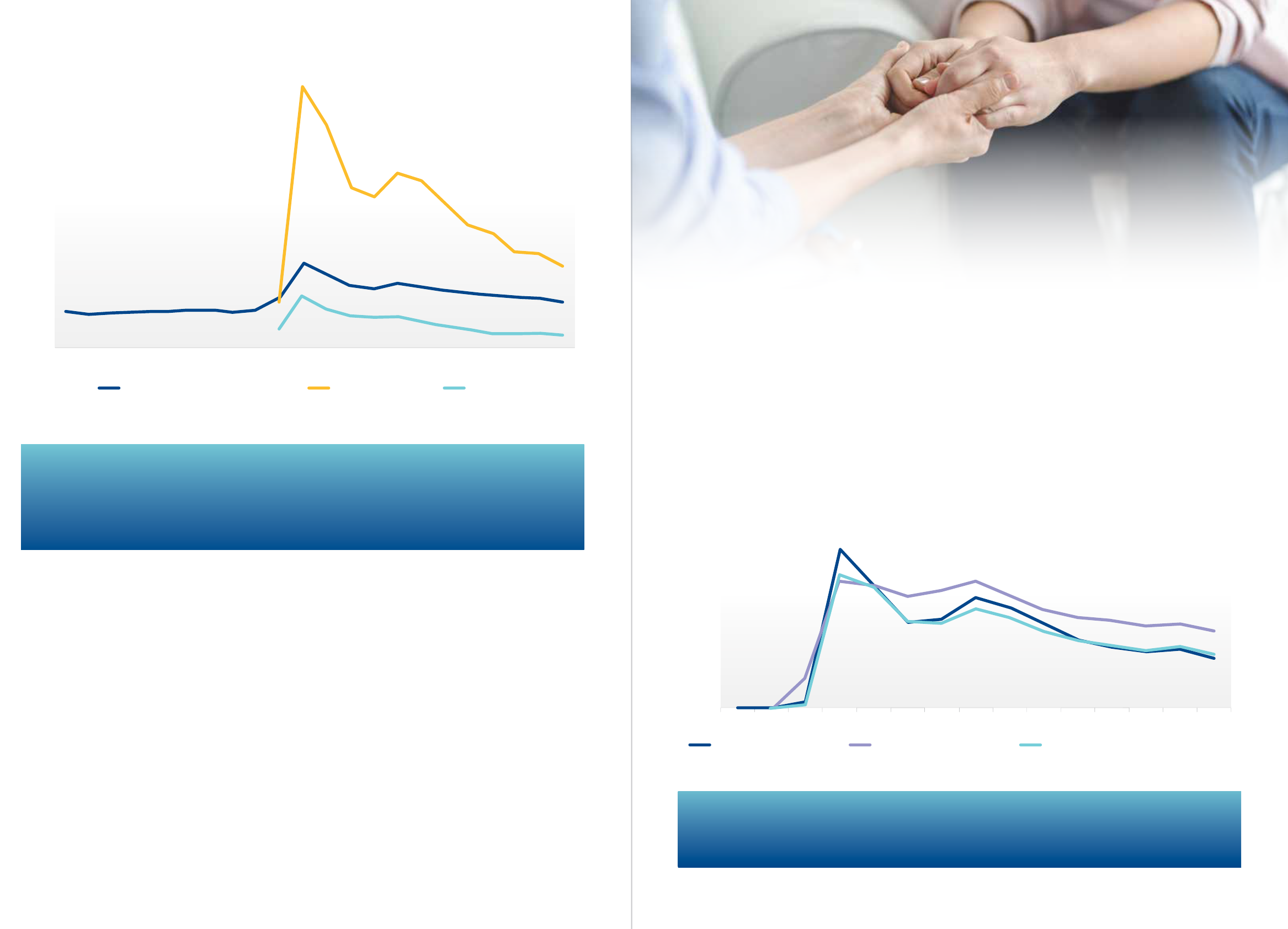

International medical graduates (IMGs) comprised 35.1

per cent of the total Australian medical workforce in

clinical practice in 2019, a fall from 37.5 per cent in 2013

because of faster growth in domestic supply rather than

falls in immigration (4.9 per cent per year compared to

2.8 per cent per year for IMGs). Figure 3 shows that the

overall number of GPs and non-GP specialists who are

IMGs has continued to increase steadily over time, by 4.5

per cent and 6 per cent respectively, whilst the number

of IMGs who are doctors in training has fallen. Combined

with increased domestic supply of doctors in training,

this has contributed to a fall in the proportion of hospital

non-specialists who are IMGs (this group includes

medical ocers) from 39.3 per cent in 2013 to 26.3 per

cent in 2019, with a similar fall in this percentage for

specialists in training (39.3 per cent to 28.1 per cent).

For both GPs and non-GP specialists, continuing

immigration means that the growth in numbers of

IMGs has been higher than the growth in the number of

Australian-trained doctors. The proportion of specialists

who are IMGs continued to increase from 30.8 per cent in

2013 to 32.9 per cent in 2019. This is because the growth

in the number of IMG non-GP specialists (6 per cent per

year) continues to outstrip the growth in the numbers of

Australian trained non-GP specialists (3.9 per cent). The

percentage of GPs who are IMGs has grown slightly from

43.1 per cent in 2013 to 44.8 per cent in 2019.

Despite some policy changes designed to reduce

immigration, IMGs continue to represent a very flexible

and cost-eective solution for employers in rural and

regional areas who often drive temporary immigration

through sponsorship of visas. Even with an increase in

NOT ENOUGH GPS, TOO MANY NON-GP

SPECIALISTS?

Figure 1 shows that a higher proportion of junior doctors

are continuing to choose non-GP specialty training, as

the number of specialists grows faster than the number

of GPs. Over the past 20 years there have been no

explicit policies designed to alter specialty choices.

More GP training places do not alter doctors’ preferences

or the relative attractiveness of general practice.

There is recent evidence that the number of GP training

places are not being filled, with falls in the numbers of

applicants for GP training (RACGP, 2020).

Our previous research has shown that relative earnings

can play a key role in specialty choice (Sivey et al.,

2012). Doctors’ annual earnings (annual income from

all medical work after practice costs but before tax) are

increasing in real terms, by an average of 1.1 per cent per

year for GPs and by 2.2 per cent for non-GP specialists.

This is similar to wage growth in the rest of the economy.

But what is the evidence that if GP earnings were

higher, more doctors would choose to become a GP?

Our previous review of evidence of medical career

choices suggest a range of factors play a role, with

advice from supervisors and senior doctors playing

a major role (Scott et al., 2014). MABEL research

found that expected future earnings was an important

factor, along with opportunities for procedural work,

hours worked, control over hours worked, on-call,

opportunities for academic work and continuity of care

(Sivey et al., 2012). Future earnings were more important

for the 33 per cent of junior doctors reporting any

educational debt.

Our research simulated that if GP earnings were to

increase by $50 000 per year (around $280,000 in

2020 prices), the percentage of junior doctors choosing

general practice would increase by 10.5 percentage

points (Figure 4). More procedural work and academic

work had similar sized eects (13.1 and 7.9 percentage

point increases) as a $50,000 increase in earnings,

suggesting that other factors matter at least as much

as earnings (Sivey et al., 2012).

Figure 5 shows that the remuneration of non-GP

specialists remains high relative to GPs. In 2018, non-

GP specialists earned almost double as much as GPs.

Importantly, this gap has widened over time.

These trends are similar if we adjust for dierences in

hours worked. In 2008 mean GPs earnings were $189,574

per year, increasing by 10.7 per cent to $209,938 in 2018.

Non-GP specialists mean annual earnings were $338,554

in 2008, with this increasing by 21.5 per cent to $411,575

in 2018 – double the rate of earnings growth for GPs.

Where earnings matter, this is making it more dicult to

persuade more junior doctors to become GPs.

Policies such as the Medicare fee freeze, where the

indexing of Medicare rebates in line with inflation

was frozen between 2014 and 2018, are likely to have

widened the gap in earnings, compounding these

issues. Though the fee freeze was applied to all doctors,

this was more likely to have adversely aected the

remuneration and morale of GPs, since they bulk-bill

more and face more competition (Gravelle et al., 2016)

compared to non-GP specialists, potentially further

widening the gap in remuneration and reducing the

attractiveness of general practice as a speciality.

More generally, policies that attempt to reduce Medicare

spending on GPs will likely mean fewer junior doctors

will end up choosing general practice training.

Figure 3

Figure 4

$450,000

$400,000

$350,000

$300,000

$250,000

$200,000

$150,000

$100,000

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

GP self-reported annual income

(before tax, after practice costs)

GP annual total fee revenue: Medicare

Non-GP specialist self-reported annual income

(before tax, after practice costs)

Non-GP specialist annual total fee revenue: Medicare

16,000

14,000

12,000

10,000

8,000

6,000

4,000

2,000

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

0

General practitioner (GP)

Hospital non-specialist

Specialist

Specialist-in-training

Figure 3. Number of doctors who are international

medical graduates, by doctor type (2013 to 2019).

THE EVOLUTION OF THE MEDICAL WORKFORCE 98 ANZ—MELBOURNE INSTITUTE HEALTH SECTOR REPORT

Source: Health Workforce Planning Tool, Department of Health.

Figure 4. The increase in the probability of junior doctors

choosing GP training under specific scenarios.

Source: Sivey et al (2012).

DOCTORS’ EARNINGS

Fee revenue per doctor falling

Figure 5 also includes data on fee revenue per doctor.

Using data from Medicare, this is the total fee revenue

from private practice each year divided by the number

of doctors. This includes revenue received from Medicare

benefits plus patients’ out of pocket costs (and for non-

GP specialists, from private health insurers who may

cover patient’s in-hospital out of pocket costs using gap

cover). Note that for GPs, fee revenue does not include

revenue paid to the practice from the Practice Incentive

Program (around 10 per cent of revenue), and so this line

is an underestimate of the level of fee revenue per GP.

Doctors may also receive other revenue not captured

here such as rent paid by pathology companies. For non-

GP specialists working across both public hospitals and

private practice, income received from public hospitals

is included in the self-reported earnings data, whilst fee

revenue includes only revenue from private practice.

Fee revenue per doctor has been falling over time after

adjusting for CPI. This downward trend remains, but is

slightly flatter, after we adjust for a fall in hours worked

over time. This squeeze in revenue could be due to a

combination of several factors. First, this could partly be

a function of the Medicare fee freeze that started in July

2014, especially for GPs, but the fall starts before that.

Second, there is evidence of a reduction in the growth

in the volume of private hospital care after 2016, when

the fall in private health insurance membership started

and debate about egregious fees and high out of pocket

costs began (Bai et al., 2020). But the fall in annual

revenue begins in 2013, before these issues started.

Third, and most likely, is that the fall of fee revenue

over time could be because of the increasing number

of doctors over time (Figure 1) leading to increased

competition. The overall number of patients and services

per patient grew between 2009-2010 and 2019-2020

(both by 1.8 per cent per year), but this growth was

much slower than the growth in the number of GPs (3.5

per cent) and non-GP specialists (4.5 per cent).

This seems to be the case: the total number of patients

using Medicare per doctor (GP plus non-GP specialist)

peaked in 2011 at 384 and fell by 1.9 per cent per year

to 327 by 2019. Similarly, the number of Medicare

services per doctor fell by 0.8 per cent, from 7,002 in

2009 to 6,320 in 2019. Supply has been increasing faster

than demand suggesting there were fewer patients to

go around.

Figure 5

Figure 6

74.3%

80.1%

79.8%

87.7%

Non-GP specialistsGPsAll Medicare

35.6%

28.7%

0.105

0.131

0.079

If income increased by $50,000

If procedural work increased from ‘none’ to ‘some’

If opportunities for academic work increased from

‘poor’ to ‘average’

2009-10 2019-20

Figure 6. Percentage of services bulk billed, 2009-2010 to 2019-2020.

Why are earnings (after practice costs) rising,

but fee revenue per doctor falling?

In the context of falling fee revenue per doctor, the

only way that doctors can maintain their self-reported

earnings (after practice costs but before tax) in Figure

5 is if practice owners are reducing costs to maintain

their take home pay, or if they are earning more medical

income from other sources.

Unfortunately, no data are routinely collected on

practice costs. Some cost reductions could have been

achieved through practices becoming larger over time

(Scott, 2017) such that the sharing of fixed costs across

more GPs could lead to lower practice costs per doctor

(economies of scale).

For non-GP specialists in Figure 5, self-reported earnings

are for work in both public hospitals and the private

sector, whilst fee revenue is only for private work

from the MBS. Figure 4 shows that the gap between

fee revenue and self-reported earnings is widening

over time, suggesting an increasing share of earnings

from their work in the public sector over time, and/

or reductions in practice costs. This is consistent with

evidence showing that non-GP specialists have been

spending a higher proportion of their time in public

hospitals since 2015 (Bai et al., 2020).

If non-GP specialists have been spending more time

in public hospitals, this also has implications for the

availability of public hospital positions for newly qualified

specialists, which might also explain the increasing share

of non-GP specialists working outside of major cities in

Figure 2. There is also anecdotal evidence that non-GP

specialists are forming into larger groups with corporate

ownership, again possibly leading to lower costs per

doctor enabling them to maintain earnings after practice

costs whilst fee revenue declines.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE MEDICAL WORKFORCE 1110 ANZ—MELBOURNE INSTITUTE HEALTH SECTOR REPORT

Source: Own calculations from ‘MBS statistics financial year 2019-2020 Geo.xls’ downloaded from: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/

Content/32CC6EB4BCC0BB1CCA257BF0001FEB92/$File/MBS%20Statistics%20Financial%20Year%202019-20%20Geo.xlsx. GP bulk-billing rate includes

out-of-hospital unreferred attendances. Non-GP specialist bulk billing rate includes specialist attendances, obstetrics, anaesthetics, and operations

(excludes pathology, diagnostic imaging, radiotherapy and therapeutic nuclear medicine).

Figure 3

Figure 4

$450,000

$400,000

$350,000

$300,000

$250,000

$200,000

$150,000

$100,000

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

GP self-reported annual income

(before tax, after practice costs)

GP annual total fee revenue: Medicare

Non-GP specialist self-reported annual income

(before tax, after practice costs)

Non-GP specialist annual total fee revenue: Medicare

16,000

14,000

12,000

10,000

8,000

6,000

4,000

2,000

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

0

General practitioner (GP)

Hospital non-specialist

Specialist

Specialist-in-training

Figure 5. Annual earnings and fee revenue of GPs and Non-GP specialists, 2008 to 2018 (weighted and adjusted for CPI).

Source: Self-reported annual income is from the Medicine in Australia: Balancing Employment of Life (MABEL) survey on annual income before tax but after practice

costs – essentially gross take home pay. This uses data from between 1,813 and 3,270 GPs per year, and from between 2,206 to 4,261 non-GP specialists per year, and

is adjusted for CPI, and also weighted to be representative of the doctor population. Fee revenue reported is from Medicare data linked to MABEL survey respondents

who consented to data linkage. For GPs, this does not include practice-level payments from the Practice Incentive Program (which would add about 10 per cent to

these figures) or other sources of income. Fee revenue data are from between 661 and 988 GPs per year, and between 713 and 943 non-GP specialists per year, and is

adjusted for CPI, and also weighted to be representative of the doctor population. The findings are very similar if we use the same doctors for the MABEL self-reported

earnings as for the fee revenue.

BULK BILLING AND FEES RISING

Against a backdrop of lower fee revenue, decisions

such as changing the fees charged, including choosing

whether to bulk bill and choosing whether to use gap

cover arrangements with private health insurers, are

important business decisions for influencing revenue

but are also decisions that impact on patients’ access

to healthcare. The balance between maintaining the

number of patients seen and what they are charged can

be dicult, more so for GPs who face more competition.

Figure 6 shows that bulk-billed services, where there

is no out of pocket cost to the patient, as a percentage

of all Medicare services have increased from 74.3 per

cent in 2009-2010 to 80.1 per cent in 2019-2020. Bulk

billing rates for non-GP specialists (including specialist

attendances, obstetrics, anaesthetics, operations) remain

much lower than for GPs (35.6 per cent compared to

87.7 per cent), though have increased at a faster rate

compared to those for GPs, by 23.9 per cent over the

period compared to 7.7 per cent for GPs.

The increase in bulk billing rates reduces revenue per

service, but this can be balanced by an increase in fees

for non-bulk billed services, as shown in Figure 7. More

auent patients are still likely to attend if fees rise,

whilst increasing bulk billing may lead to an increase

in utilisation for patients who are less well-o. There is

evidence that some doctors care about their patients’

financial circumstances (Ge et al., 2019), and that doctors

in less auent areas of Australia charge lower fees

(Gravelle et al., 2016; Johar, 2012; Johar et al., 2017).

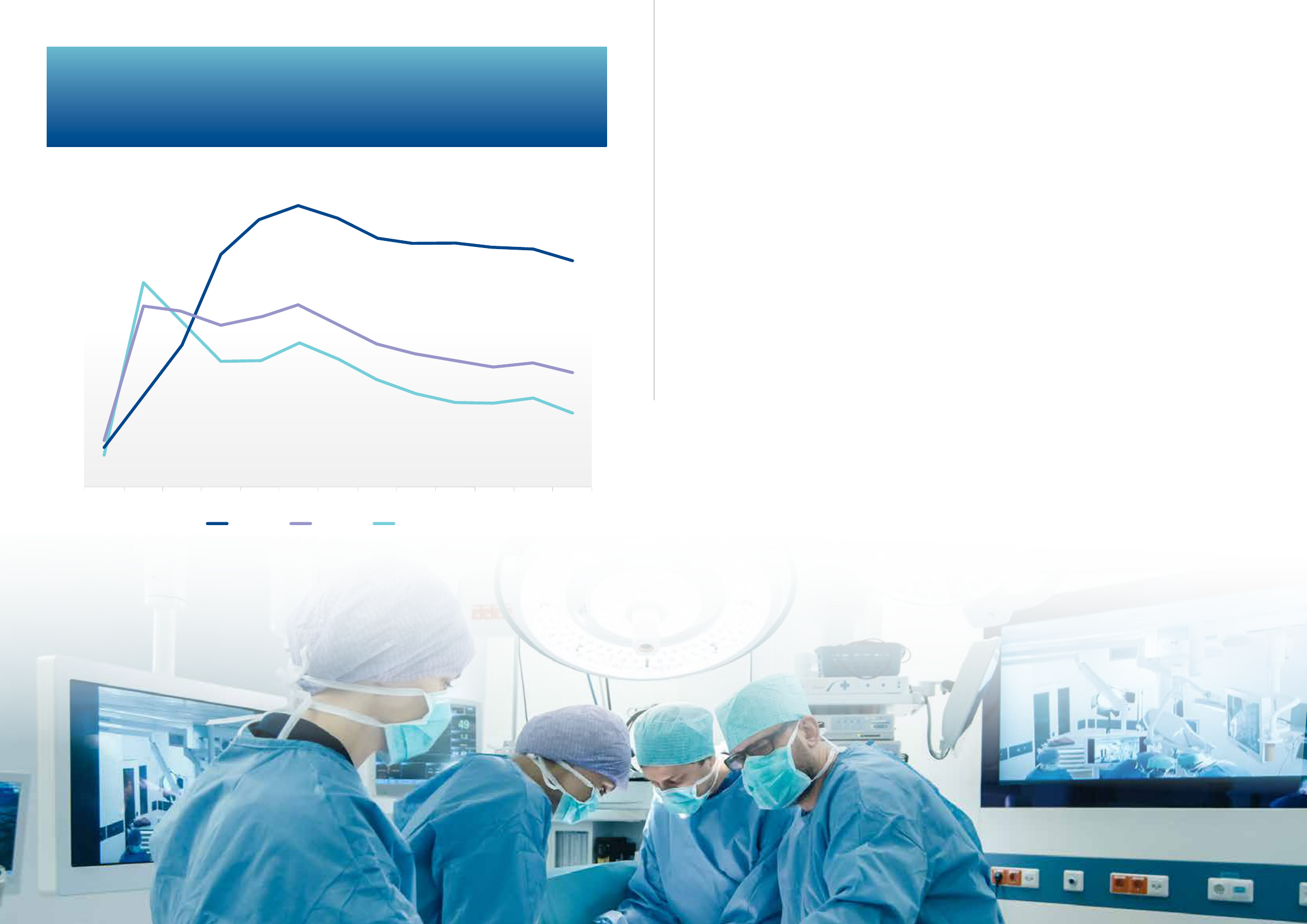

TELEHEALTH USE FALLING

During COVID-19 there were high hopes that telehealth

might become part of routine care. The rapid

introduction of telehealth brought the future slightly

closer as many healthcare providers and patients had a

taste for how this could work. Telehealth can potentially

solve not only issues arising during pandemics, but also

how to improve access to healthcare for vulnerable and

underserved populations. The use of telehealth would

also make the system more responsive and flexible to

patients’ needs.

New telehealth items were funded from March 2020 to

help protect patients and providers from COVID-19, as

well as help circumvent the fall in demand for healthcare

that led to substantial falls in income for many providers

in 2020 (Scott, 2020). Since then, the use of telehealth

has fallen overall as the pandemic in Australia has

subsided. Figures 8 and 9 show the use of telehealth

MBS items between March 2020 and March 2021.

The use of telehealth reached its peak in April 2020

when 36 per cent of all Medicare consultation items

for GPs and non-GP specialists were conducted using

telehealth. Figure 8 for GPs and Figure 9 for other

specialists show a gradual fall in the use of telehealth

since then. By March 2021, the proportion of GP

attendances using telehealth had fallen at 21.6

per cent, and to 13.4 per cent for other specialists.

These are still very large proportions at a time when

Australia is essentially free of COVID-19, but the trend

is still downward, and it is unclear when it will stabilise

and find its ‘natural’ rate. Partly this will be determined

by expectations and the exact details of policy changes

beyond 2021.

Non-GP SpecialistsGPsAll Medicare

$79.27

$63.95

$39.33

$29.35

$141.41

$123.41

Figure 7

Figure 8

0

3,500,000

7,000,000

10,500,000

14,000,000

Face-to-face Telephone Video Total unreferred attendances

Nov 19

Dec 19

Jan 20

Feb 20

Mar 20

Apr 20

May 20

Jun 20

Jul 20

Aug 20

Sep 20

Oct 20

Nov 20

Dec 20

Jan 21

Feb 21

Mar 21

2009-10 2019-20

Non-GP SpecialistsGPsAll Medicare

$79.27

$63.95

$39.33

$29.35

$141.41

$123.41

Figure 7

Figure 8

0

3,500,000

7,000,000

10,500,000

14,000,000

Face-to-face Telephone

Video Total unreferred attendances

Nov 19

Dec 19

Jan 20

Feb 20

Mar 20

Apr 20

May 20

Jun 20

Jul 20

Aug 20

Sep 20

Oct 20

Nov 20

Dec 20

Jan 21

Feb 21

Mar 21

2009-10 2019-20

Figure 10

7%

6%

4%

1%

5%

2%

3%

0%

3,000,000

2,250,000

1,150,000

750,000

0

Face-to-face

New telehealthOld telehealth Total attendances

Jun 19 Jun 20Apr 20Feb 20Dec 19Oct 19Aug 19 Aug 20 Oct 20 Dec 20 Feb 21

Old telehealth (Non-GP specialists) Non-GP specialists GPs

Nov 19

Dec 19

Jan 20

Feb 20

Mar 20

Apr 20

May 20

Jun 20

Jul 20

Aug 20

Sep 20

Oct 20

Nov 20

Dec 20

Jan 21

Feb 21

Mar 21

Figure 7. Fee charged per non-bulk-billed service, adjusted for CPI, 2009-2010 to 2019-2020.

Figure 8. Number of MBS items claimed for GP attendances, November 2019 to March 2021.

Figure 9. Number of MBS items claimed for Specialist attendances, November 2019 to March 2021.

12 ANZ—MELBOURNE INSTITUTE HEALTH SECTOR REPORT

Source: Own calculations from ‘MBS statistics financial year 2019-2020 Geo.xls’ downloaded from: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/

Content/32CC6EB4BCC0BB1CCA257BF0001FEB92/$File/MBS%20Statistics%20Financial%20Year%202019-20%20Geo.xlsx. GP data include out-of-hospital

unreferred attendances. Non-GP specialist data include specialist attendances, obstetrics, anaesthetics, and operations (excludes pathology, diagnostic imaging,

radiotherapy and therapeutic nuclear medicine). Fee charged per non-bulk billed service = (Fee charged – Benefit paid) / (All services – Bulk billed services).

Source: MBS Statistics Item Reports http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp using telehealth item numbers:

http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/news-2020-03-29-latest-news-March.

Source: MBS Statistics Item Reports http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp using telehealth item numbers:

http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/news-2020-03-29-latest-news-March.

Video consultations remain low

Though there was much promise about the increased

use of telehealth heralding advances in technology,

the vast majority of telehealth consultations used phone

calls rather than video, especially for GPs. Department

of Health guidance states that video is the preferred

method of conducting a telehealth consultation, yet the

use of video has remained stubbornly low and is falling

(Figure 8 and 9).

Figure 10 shows the proportion of attendances using

video conferencing for GPs and specialists.

Before COVID-19, non-GP specialists could already claim

MBS items for video consultations for patients in rural

and regional areas, and GPs as well could access some

items for aged care. Interestingly, Figure 10 also shows

that the proportion of specialist attendances using

these ‘old’ telehealth items seems to have increased,

compared to before COVID-19, suggesting better access

to care for patients in rural and regional areas. However,

our previous research during COVID-19 showed that the

use of new telehealth items by GPs in May 2020 was no

higher for patients in rural and regional areas compared

to those in major cities (Scott et al., 2021).

In terms of the low use of video consultations, especially

by GPs, our previous research showed that a lack of

infrastructure may be an important the reason for

this (Scott et al., 2021). A continuing lack of certainty

about the permanence of Medicare funding could have

discouraged GP practices to invest in this infrastructure

during 2020. Furthermore, our research showed that

GPs with a higher share of elderly patients were less

likely to use video consultations, presumably because

of diculties for some elderly patients, who are perhaps

those most in need, in using this technology and so

preferring the phone. The MBS rebates for video and

phone consultations are also the same, and so there

is scope to change financial incentives to encourage a

higher proportion of video consultations.

Figure 10

7%

6%

4%

1%

5%

2%

3%

0%

3,000,000

2,250,000

1,150,000

750,000

0

Face-to-face New telehealthOld telehealth Total attendances

Jun 19 Jun 20Apr 20Feb 20Dec 19Oct 19Aug 19 Aug 20 Oct 20 Dec 20 Feb 21

Old telehealth (Non-GP specialists)

Non-GP specialists GPs

Nov 19

Dec 19

Jan 20

Feb 20

Mar 20

Apr 20

May 20

Jun 20

Jul 20

Aug 20

Sep 20

Oct 20

Nov 20

Dec 20

Jan 21

Feb 21

Mar 21

Figure 11

Figure 12

50%

30%

35%

40%

45%

25%

20%

5%

10%

15%

0%

15%

30%

45%

60%

0%

Jan 20 Feb 20 Mar 20 Apr 20 May 20Jun 20 Jul 20 Aug 20 Sep 20 Oct 20 Nov 20 Dec 20 Jan 21 Feb 21 Mar 21

Mental Health telehealth GP attendances telehealth Chronic Disease Management telehealth

Mar 20 Apr 20 May 20 Jun 20 Jul 20 Aug 20 Sep 20 Oct 20 Nov 20 Dec 20 Jan 21 Feb 21 Mar 21

Level A Level B Level C+D

Figure 10. Percentage of attendances using video conferencing, June 2019 to March 2021.

Figure 11. Percentage of GP Mental Health and Chronic Disease Management Plans using telehealth,

March 2020 to March 2021.

The use of video has been much lower for GPs as a proportion of total attendances compared to

other specialists. In April 2020, 1.3 per cent of all GP attendances used video, and this had fell to

0.32 per cent by March 2021. For non-GP specialists in private practice, use has been much higher

than GPs, with 6.8 per cent of attendances using video in April 2020, falling to 2.1 per cent by

March 2021.

Data for the use of telehealth for specific populations shows that in March 2021, telehealth was

used in 14 per cent of GP Mental Health plans and 14.9 of GP Chronic Disease Management Plans.

This compares to the use of telehealth in 21.6 per cent of all GP attendances.

Use of video for specific populations

For specific population groups that could be more in

need, the use of telehealth was lower than usual GP

consultations. This is shown in Figure 11 that highlights a

declining trend in the proportion on mental health and

chronic disease items using telehealth, no dierent from

the fall in use for GP attendances overall.

Though there is a focus on higher quality video

conferencing, there also seems to be a role for short

telephone consultations, used to provide follow-up

to patients for test results or repeat prescriptions and

referrals, and for shorter acute presentations that

do not require a physical examination or non-verbal

communication. This is work that some GPs may have

undertaken before COVID-19 to an extent but did not

receive a fee, with other GPs requesting that the patient

visited the practice to receive a fee.

The further development of policy around the use

of telehealth beyond the end of 2021 needs to be

supported by more clear evidence of benefit for

population sub-groups. For GPs, encouraging the higher

use of video and the value of short consultations over

the phone seem to be clear and of benefit to patients.

There are no national data on the use of telehealth

by non-GP specialists for public hospital outpatient

appointments. The need for telehealth to remain

available for any further disease outbreaks is important,

even though there has been a steady fall in utilisation

over time.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE MEDICAL WORKFORCE 1514 ANZ—MELBOURNE INSTITUTE HEALTH SECTOR REPORT

Source: MBS Statistics Item Reports: http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp using telehealth item numbers:

http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/news-2020-03-29-latest-news-March.

Source: MBS Statistics Item Reports: http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp using telehealth item numbers:

http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/news-2020-03-29-latest-news-March.

CONCLUSIONS

The rapid expansion of the medical workforce has

led to a number of policy issues about how best to

direct the medical workforce to areas of highest need.

Twenty years after this expansion began, including the

introduction and then abolition of Health Workforce

Australia, a National Medical Workforce Strategy has

been developed to try and tackle some of these issues

(Department of Health, 2019).

The strategy has five priorities with exact details and

plans for implementation to be published: i) collaborate

on planning and design, ii) rebalance supply and

distribution, iii) reform the training pathway, iv)

building the generalist capability of the medical

workforce, and v) a flexible and responsive medical

workforce. These are lofty aims but do set out a clear

vision for where to head. If the last 20 years is anything

to go by, addressing these priorities will take time.

Australia’s fractured health care system has significantly

delayed eective national policy action to help ensure

the best use of the medical workforce.

Issues of specialty choice, rural and regional

maldistribution, and self-suciency remain very

important, with market forces continuing to dominate

doctors’ decisions about their specialty and location of

practice. Doctor’s decisions are underpinned by a largely

unaltered fee-for-service payment model that rewards

procedural work and sub-specialisation more than

generalism and holistic care.

Our analysis suggests that, 20 years later, the increase

in supply of medical practitioners is finally beginning

to spill over to rural and regional areas, though this is

not the case for GPs. This could be explained by the

increased supply and competition that is eventually

pushing doctors out of major cities, caused by the

increased investment in regional training of GPs and

non-GP specialists and other policies pulling doctors

away from major cities, or caused by existing non-

GP specialists spending more time in public hospitals

reducing opportunities for newly qualified non-GP

specialists in major cities.

Regionally-based training should continue to be an

essential part of all medical training. Self-suciency

still seems a long way o as the number of international

medical graduates continues to grow. The disruption to

immigration due to COVID-19 may make it more dicult

for rural and regional areas to fill vacant positions, but on

the other hand could also create more vacancies in major

cities that will prevent domestically trained doctors from

going rural.

The widening gap between non-GP specialists’ and

GPs’ earnings, exacerbated by the Medicare Fee Freeze,

is important context in an area where there has been

no national policy to correct the imbalance in the

numbers of GPs and non-GP specialists in Australia.

It is clear that over 20 years, the increased supply has

disproportionately been funnelled away from

primary care.

There is evidence that fee revenue per doctor is also now

falling, likely due to increased supply as the growth in the

number of doctors is higher than the growth in demand

from patients. Whilst doctors’ earnings (after practice

costs) are still increasing, falls in fee revenue per doctor

suggest that practice costs per doctor are falling and/or

income is increasing in other ways.

How doctors in private practice manage their billing

and workload is a key issue. Doctors are continuing to

increase their bulk-billing rates, especially for non-GP

specialists, to help maintain volume, whilst fees for non-

bulk billed services increase. Whilst discretion on setting

fees has provided some flexibility, there is only so much

that can be done if there are fewer patients to go around.

The impact of COVID-19 on some of these long term

trends is still unclear but has highlighted how flexible the

medical workforce (and the health care system) needs

to be to meet patients’ needs in an uncertain world.

Though patterns of disease have remained largely the

same, the introduction of telehealth has changed how

the population interacts with doctors and going back

to what it was before COVID-19 does not seem to be an

option. Flexibility and adaptation is the key to ensuring

that the population’s changing health needs are met.

16 ANZ—MELBOURNE INSTITUTE HEALTH SECTOR REPORT

Figure 11

Figure 12

50%

30%

35%

40%

45%

25%

20%

5%

10%

15%

0%

15%

30%

45%

60%

0%

Jan 20 Feb 20 Mar 20 Apr 20 May 20Jun 20 Jul 20 Aug 20 Sep 20 Oct 20 Nov 20 Dec 20 Jan 21 Feb 21 Mar 21

Mental Health telehealth GP attendances telehealth Chronic Disease Management telehealth

Mar 20 Apr 20 May 20 Jun 20 Jul 20 Aug 20 Sep 20 Oct 20 Nov 20 Dec 20 Jan 21 Feb 21 Mar 21

Level A

Level B Level C+D

Figure 12. Percentage of GP telehealth consultations which are Level A, B, C and D, March 2020 to March 2021.

Figure 12 shows that Level A (short) consultations make up almost 50 per cent of all telehealth

consultations and remain quite high in March 2021, and that the share of Level B, C and D

telehealth consultations are much lower. In March 2021 there were 225,542 Level A face to face

GP consultations, a similar level compared to before COVID-19, and 435,314 Level A GP telehealth

consultations (4,270 using video). This suggests that the telehealth consultations are additional to

what was previously undertaken.

Source: MBS Statistics Item Reports http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp using telehealth item numbers:

http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/news-2020-03-29-latest-news-March.

THE FUTURE OF THE MEDICAL WORKFORCE 1918 ANZ—MELBOURNE INSTITUTE HEALTH SECTOR REPORT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This report was funded by Australia and New Zealand

Banking Group Limited. Funding for MABEL comes

from the National Health and Medical Research

Council (2007 to 2016: 454799 and 1019605); the

Australian Department of Health and Ageing (2008);

Health Workforce Australia (2013); and in 2017 The

University of Melbourne, Medibank Better Health

Foundation, the NSW Ministry of Health, and the

Victorian Department of Health and Human Services.

This report was prepared by Professor Anthony Scott

with assistance from Mr Terence Bai of the Melbourne

Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research at The

University of Melbourne.

1. Australian Health Ministers’ Council. 2004. National

Health Workforce Strategic Framework. Australian

Health Ministers Council, Sydney.

2. Bai, T., Mendez, S., Scott, A., Yong, J., 2020. The falling

growth in the use of private hospitals in Australia.

Working Paper 18/20, The University of Melbourne,

Melbourne.

3. Department of Health, 2019. Scoping Framework

for the National Medical Workforce Strategy, 2019,

Australian Government, Canberra.

4. Ge, G., Godager, G., Wang, J., 2019. Ge, Ge & Godager,

Geir & Wang, Jian, 2019. “Do physicians care about

patients’ utility? Evidence from an experimental

study of treatment choices under demand-side cost

sharing,” , University of Oslo, Health Economics

Research Programme., Universirty of Oslo, Oslo.

5. Gravelle, H., Scott, A., Sivey, P., Yong, J., 2016.

Competition, prices and quality in the market for

physician consultations. The Journal of Industrial

Economics, 64(1), 135-169.

6. Johar, M., 2012. Do doctors charge high income

patients more? Economics Letters, 117, 596-599.

7. Johar, M., Mu, C., Van Gool, K., Wong, C.Y., 2017.

Bleeding Hearts, Profiteers, or Both: Specialist

Physician Fees in an Unregulated Market. Health

Economics, 26(4), 528-535.

8. Li, J.H., Scott, A., McGrail, M., Humphreys, J., Witt, J.,

2014. Retaining rural doctors: Doctors’ preferences

for rural medical workforce incentives. Social Science

& Medicine, 121, 56-64.

9. McIsaac, M., Scott, A., Kalb, G., 2015. The supply of

general practitioners across local areas: accounting

for spatial heterogeneity. BMC Health Services

Research, 15(1).

10. O’Sullivan, B., Russell, D.J., McGrail, M.R., Scott, A.,

2019. Reviewing reliance on overseas-trained doctors

in rural Australia and planning for self-suciency:

applying 10 years’ MABEL evidence. Human

Resources for Health, 17(1), 8.

REFERENCES

18 ANZ—MELBOURNE INSTITUTE HEALTH SECTOR REPORT

11. Scott, A., 2017. General Practice Trends. ANZ-Melbourne

Institue Health Sector Report, Melbourne Institute: Applied

Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne,

Melbourne.

12. Scott, A., 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on GPs and non-GP

specialists. ANZ-Melbourne Institute Health Sector Report,

Melbourne Institute: Aplied Economic and Social Research,

The University of Melbourne, Melbourne.

13. Scott, A., Bai, T., Zhang, Y., 2021. Association between

telehealth use and general practitioner characteristics during

COVID-19: findings from a nationally representative survey of

Australian doctors. BMJ Open, 11(3), e046857.

14. Scott, A., Joyce, C., Cheng, T., Wang, W., 2014. Medical Career

Path Decision Making: A Rapid Review. Evidence Check

Review, Sax Institute, Sydney.

15. Scott, A., Witt, J., Humphreys, J., Joyce, C., Kalb, G., Jeon,

S.H., McGrail, M., 2013. Getting doctors into the bush: General

Practitioners’ preferences for rural location. Social Science &

Medicine, 96, 33-44.

16. Sivey, P., Scott, A., Witt, J., Joyce, C., Humphreys, J., 2012.

Junior doctors’ preferences for specialty choice. Journal of

Health Economics, 31(6), 813-823.

17. Yong, J., Scott, A., Gravelle, H., Sivey, P., McGrail, M., 2018. Do

rural incentives payments aect entries and exits of general

practitioners? Social Science & Medicine, 214, 197-205.

18. Geen, L. 2014. A brief history of medical education and

training in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia, 201 (1):

S19-S22

20 ANZ—MELBOURNE INSTITUTE HEALTH SECTOR REPORT

© 2021

Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research