Linda Darling-Hammond and Channa M. Cook-Harvey

Educating the Whole Child:

Improving School Climate to

Support Student Success

SEPTEMBER 2018

Educating the Whole Child:

Improving School Climate to

Support Student Success

Linda Darling-Hammond and Channa M. Cook-Harvey

ii LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Castle Redmond and Jennifer Chheang at the California Endowment for their

thoughtful guidance and input into this report. We also beneted from the feedback of a number of California

educators, researchers, community organization leaders, and advocates, including Teiahsha Bankhead,

Restorative Justice for Oakland Youth; Joseph Bishop, Center for the Transformation of Schools at UCLA;

Dwight Bonds, California Association of African-American Superintendents and Administrators; Susan Bonilla,

Council for a Strong America; Raymond Colmenar, The California Endowment; Sean Darling-Hammond,

University of California, Berkeley; Joyce Dorado, University of California, San Francisco; Laura Faer, Public

Counsel Law Center; Sophie Fanelli, Stuart Foundation; Liz Guillen, Public Advocates; Jessica Gunderson,

Partnership for Children & Youth; Thomas Hanson, WestEd; Heather Hough, Policy Analysis for California

Education; Taryn Ishida, Californians for Justice; Debbie Lee, Futures Without Violence; Sergio Luna, PICO

California; Brent Malicote, Sacramento County Ofce of Education; Kim Mecum, Fresno Unied School

District; Mary Perry, California State PTA; Glen Price, California Department of Education; Ryan Smith, The

Education Trust–West; Elisha Smith Arrillaga, The Education Trust–West; Brad Strong, Children Now; Sylvia

Torres-Guillén, ACLU of Southern California; and David Washburn, EdSource.

We appreciate LPI colleagues Lisa Flook, Roberta Furger, and Hanna Melnick for providing background research

and input to this report, and Charlie Thompson for her expert help with references and citations. In addition,

thanks are due to Aaron Reeves and Gretchen Wright for their design and editing contributions to this project,

and to Lisa Gonzales for overseeing the editorial and production processes.

This document draws upon the article “Implications for Practice of the Science of Learning and Development”

by Linda Darling-Hammond, Lisa Flook, Channa Cook-Harvey, Brigid Barron, and David Osher, and on two

articles, recently published in Applied Developmental Science, from the Science of Learning and Development

initiative on which it builds: Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Malleability, plasticity,

and individuality: How children learn and develop in context and Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., Rose, T.

(2018). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development.

We are grateful to The California Endowment for its funding of this report. Funding for this area of LPI’s work

is also provided by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, and the Stuart Foundation.

Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation, the William

and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Ford Foundation.

External Reviewers

This report beneted from the insights and expertise of two external reviewers: Mark Greenberg, Bennett Chair

of Prevention Research at Penn State University and Founding Director of the Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention

Research Center; and Ming-Te Wang, Associate Professor of Psychology and Education and Research Scientist

at Learning Research and Development Center. We thank them for the care and attention they gave the report;

any shortcomings remain our own.

The suggested citation for this report is: Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the

whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

This report can be found online at https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/educating-whole-child.

Cover photo © Drew Bird.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD iii

Table of Contents

Executive Summary.................................................................................................................................. v

Introduction

...............................................................................................................................................1

The Need for a Whole Child Approach to Education

......................................................................1

The Shifts That Are Needed

...........................................................................................................2

Key Lessons From the Sciences of Learning and Development

........................................................4

1. Development is malleable

.........................................................................................................4

2. Variability in human development is the norm, not the exception

............................................4

3. Human relationships are the essential ingredient that catalyzes

healthy development and learning

............................................................................................5

4. Adversity affects learning—and the way schools respond matters

...........................................6

5. Learning is social, emotional, and academic

............................................................................7

6. Children actively construct knowledge based on their experiences,

relationships, and social contexts

.............................................................................................8

Implications for Schools: The Critical Importance of a Whole Child

Framework and a Positive School Climate

...........................................................................................9

Why a Whole Child Approach Is Essential

................................................................................... 10

School Climate and Culture: The Foundation for Development

.................................................. 11

Strategies for Developing Productive School Environments

........................................................... 14

Building Positive Classroom and School Environments

.............................................................. 15

Shaping Positive Student Behaviors

........................................................................................... 22

Providing Supports for Student Motivation and Learning

........................................................... 27

Creating Multi-Tiered Systems of Support to Address Student Needs

...................................... 32

Policy Strategies

.................................................................................................................................... 36

Developing and Assessing Positive Learning Environments

....................................................... 37

Using School Climate Data to Diagnose School Needs

.............................................................. 38

Helping Schools Improve Climate and Culture

............................................................................ 40

Reducing Rates of Exclusionary Discipline

................................................................................. 42

Providing a Multi-Tiered System of Student Support

.................................................................. 44

Investing in Educator Preparation and Development

................................................................. 45

iv LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

Recommendations ................................................................................................................................ 50

Recommendation #1:

Focus the System on Developmental Supports for Young People .......................................... 50

Recommendation #2:

Design Schools to Provide Settings for Healthy Development ............................................... 51

Recommendation #3:

Ensure Educator Learning for Developmentally Supportive Education .................................. 52

Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 53

Endnotes ................................................................................................................................................. 54

About the Authors ................................................................................................................................. 68

List of Figures and Tables

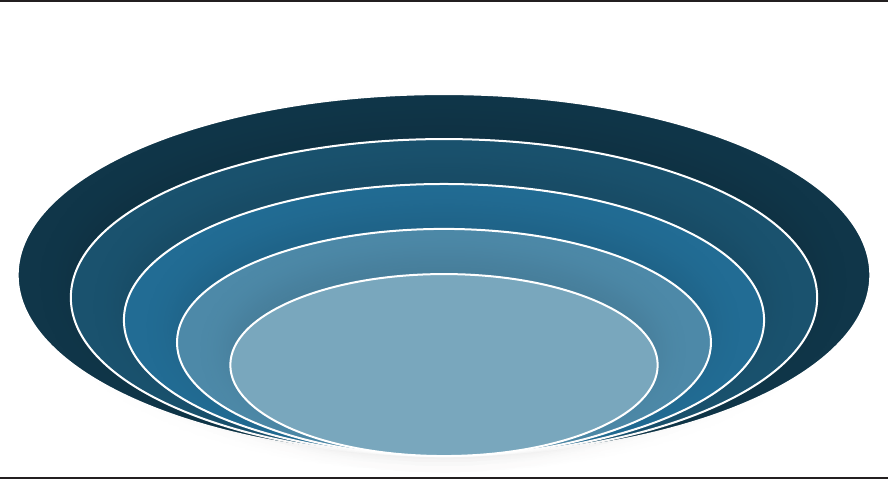

Figure 1: The Whole Child Ecosystem ..........................................................................................2

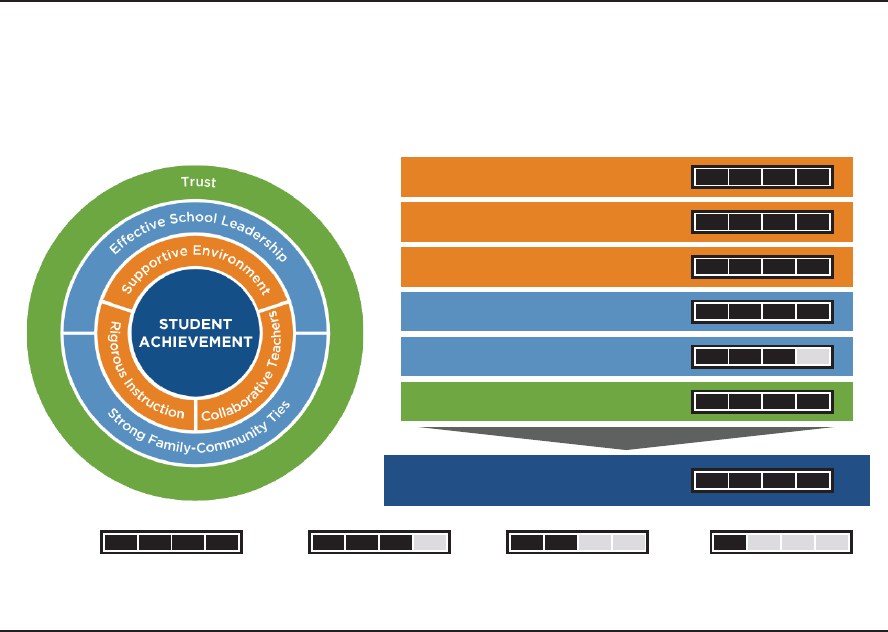

Figure 2: A Framework for Whole Child Education .......................................................................... 14

Figure 3: Sample NYC Department of Education School Quality Snapshot Summary ................... 40

Figure 4: California Principals Report Wanting More Professional Development ........................... 48

Table 1: The National School Climate Council’s 13 Dimensions of School Climate ....................... 12

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD v

Executive Summary

New knowledge about human development from neuroscience and the sciences of learning and

development demonstrates that effective learning depends on secure attachments; afrming

relationships; rich, hands-on learning experiences; and explicit integration of social, emotional,

and academic skills. A positive school environment supports students’ growth across all the

developmental pathways—physical, psychological, cognitive, social, and emotional—while it

reduces stress and anxiety that create biological impediments to learning. Such an environment

takes a “whole child” approach to education, seeking to address the distinctive strengths, needs,

and interests of students as they engage in learning.

Given that emotions and relationships strongly inuence learning—and that these are the

byproducts of how students are treated at school, as well as at home and in their communities—a

positive school climate is at the core of a successful educational experience. School climate

creates the physiological and psychological conditions for productive learning. Without secure

relationships and supports for development, student engagement and learning are undermined.

In this paper, we examine how schools can use effective, research-based practices to create settings

in which students’ healthy growth and development are central to the design of classrooms and

the school as a whole. We describe key ndings from the sciences of learning and development, the

school conditions and practices that should derive from this science, and the policy strategies that

could support these conditions and practices on a wide scale.

Key Lessons From the Science of Learning and Development

In recent years, a great deal has been learned about how biology and environment interact

to produce human learning and development. A summary of the research from neuroscience,

developmental science, and the learning sciences points to the following foundational principles:

1. Development is malleable. The brain never stops growing and changing in response to

experiences and relationships. The nature of these experiences and relationships matters

greatly to the growth of the brain and the development of skills.

Optimal brain architecture and effective learning are developed by the presence of warm, consistent

relationships; empathetic back-and-forth communications; and modeling of productive behaviors.

The brain’s capacity develops most fully when children and youth feel emotionally and physically

safe; when they feel connected, supported, engaged, and challenged; and when they have robust

opportunities to learn—with rich materials and experiences that allow them to inquire into the

world around them—and equally robust support for learning.

vi LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

2. Variability in human development is the norm, not the exception. The pace and profile of

each child’s development is unique.

Because each child’s experiences create a unique trajectory for growth, there are multiple

pathways—and no one best pathway—to healthy learning and development. Rather than assuming

all children will respond to the same teaching approaches equally well, effective teachers seek to

personalize supports for different children. Schools should avoid prescribing learning experiences

around a mythical average. When they try to force all children to t one sequence or pacing guide,

they miss the opportunity to nurture the individual potential of every child, and they can cause

children (as well as teachers) to adopt counterproductive views about themselves and their own

learning potential, which undermine progress.

3. Human relationships are the essential ingredient that catalyzes healthy development

and learning.

Supportive, responsive relationships with caring adults are foundational for healthy development

and learning. Positive, stable relationships can buffer the potentially negative effects of even

serious adversity. A child’s best performance, under conditions of high support and low threat,

differs from how he or she performs without such support or when he or she feels threatened. When

adults have the cultural competence to appreciate and understand children’s experiences, needs,

and communication, they can offset stereotypes, promote the development of positive attitudes and

behaviors, and build condence to support learning in all students.

4. Adversity affects learning—and the way schools respond matters.

Each year in the United States, 46 million children are exposed to violence, crime, abuse, or

psychological trauma, as well as homelessness and food insecurity. Experiencing these types of

adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) creates toxic stress that affects attention, learning, and

behavior. Poverty and racism, together and separately, make the experience of chronic stress and

adversity more likely. Furthermore, in schools where students encounter punitive discipline tactics

rather than supports for handling adversity, their stress is magnied. In addition to meeting basic

needs for food and health care, schools can buffer the effects of stress by facilitating supportive

adult-child relationships that extend over time; building a sense of self-efcacy and control by

teaching and reinforcing social and emotional skills that help children handle adversity, such as the

ability to calm emotions and manage responses; and creating dependable, supportive routines for

both managing classrooms and checking in on student needs.

5. Learning is social, emotional, and academic.

Emotions and social relationships affect learning. Positive relationships, including trust in the

teacher, and positive emotions—such as interest and excitement—open up the mind to learning.

Negative emotions—such as fear of failure, anxiety, and self-doubt—reduce the capacity of the

brain to process information and to learn. Students’ interpersonal skills, including their ability to

interact positively with peers and adults, to resolve conicts, and to work in teams, all contribute to

effective learning and lifelong behaviors. These skills, which build on the development of empathy,

awareness of one’s own and others’ feelings, and learned skills for communication and problem

solving, can be taught.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD vii

6. Children actively construct knowledge based on their experiences, relationships,

and social contexts.

Students dynamically shape their own learning. Learners compare new information to what they

already know in order to learn. This process works best when students engage in active, hands-on

learning, and when they can connect new knowledge to personally relevant topics and lived

experiences. Effective teachers act as mentors: setting tasks, watching and guiding children’s

efforts, and offering feedback. Providing opportunities for students to set goals and to assess their

own work and that of their peers can encourage them to become increasingly self-aware, condent,

and independent learners.

The Connection Between Whole Child Education and a Positive

School Climate

Because children learn when they feel safe and supported, and their learning is impaired when they

are fearful, traumatized, or overcome with emotion, they need both supportive environments and

well-developed abilities to manage stress. Therefore, it is important that schools provide a positive

learning environment—also known as school climate—that provides support for learning social and

emotional skills as well as academic content.

Two recent reviews of research, incorporating more than 400 studies, have found that a positive

school climate improves academic achievement overall and reduces the negative effects of

poverty on achievement, boosting grades, test scores, and student engagement. The elements of

school climate contributing most to increased achievement are associated with teacher-student

relationships, including warmth, acceptance, and teacher support. Other features include

• high expectations, organized classroom instruction, effective leadership, and teachers who

are efcacious and promote mastery learning goals;

• strong interpersonal relationships, communication, cohesiveness, and belongingness

between students and teachers; and

• structural features of the school, such as small school size, physical conditions, and

resources, which shape students’ daily experiences of personalization and caring.

Implications of the Science of Learning and Development for Schools

To support student achievement, attainment, and behavior, research suggests that schools should

attend to four major domains:

1. Supportive environmental conditions that create a positive school climate and foster

strong relationships and community. These include positive, sustained relationships that

foster attachment; physical, emotional, and identity safety; and a sense of belonging and

purpose. These can be accomplished through

• a caring, culturally responsive learning community, in which all students are well-known

and valued and are free from social identity or stereotype threats that exacerbate stress

and undermine performance;

viii LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

• structures—such as looping with teachers for more than one year, advisory systems,

small schools or learning communities, and teaching teams—that allow for continuity in

relationships, consistency in practices, and predictability in routines that reduce anxiety

and support engaged learning; and

• relational trust and respect between and among staff, students, and families enabled

by collegial supports for staff and proactive outreach to parents through home visits,

exibly scheduled meetings, and frequent positive communications.

2. Social and emotional learning that fosters skills, habits, and mindsets which enable

academic progress and productive behavior. These include self-regulation, executive

function, intrapersonal awareness and interpersonal skills, a growth mindset, and a sense of

agency that supports resilience and perseverance. They can be developed through

• explicit instruction in social, emotional, and cognitive skills, such as intrapersonal

awareness, interpersonal skills, conict resolution, and good decision making;

• infusion of opportunities to learn and use social-emotional skills, habits, and mindsets

throughout all aspects of the school’s work in and outside of the classroom; and

• educative and restorative approaches to classroom management and discipline, so that

children learn responsibility for themselves and their community.

3. Productive instructional strategies that support motivation, competence, self-

efcacy, and self-directed learning. These curriculum, teaching, and assessment

strategies feature

• meaningful work that connects to students’ prior knowledge and experiences and

actively engages them in rich, engaging, motivating tasks;

• inquiry as a major learning strategy, thoughtfully interwoven with explicit instruction

and well-scaffolded opportunities to practice and apply learning;

• well-designed collaborative learning opportunities that encourage students to question,

explain, and elaborate their thoughts and co-construct solutions;

• a mastery approach to learning supported by performance assessments with

opportunities to receive helpful feedback, develop and exhibit competence, and revise

work to improve; and

• opportunities to develop metacognitive skills through planning and management of

complex tasks, self- and peer-assessment, and reection on learning.

4. Individualized supports that enable healthy development, respond to student needs,

and address learning barriers. These include

• access to integrated services (including physical and mental health and social service

supports) that enable children’s healthy development;

• extended learning opportunities that nurture positive relationships, support enrichment

and mastery learning, and close achievement gaps; and

• multi-tiered systems of academic, health, and social supports to address learning

barriers both in and out of the classroom to address and prevent developmental detours,

including conditions of trauma and adversity.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD ix

Accomplishing this work clearly requires an intensive focus on adult development and support, so that

educators can design for and enact the practices that enable them to put these features into place.

Recommendations

This growing knowledge and practice base suggests that, in order to create schools that support

healthy development for young people, our education system needs to:

1. Focus accountability, guidance, and investments on developmental supports for

young people, including a positive, culturally responsive school climate and supportive

instruction and services.

2. Design schools to provide settings for healthy development, including secure

relationships; coherent, well-designed teaching for 21st century skills; and services that

meet the needs of the whole child.

3. Enable educators to work effectively to offer successful instruction to diverse students

from a wide range of contexts.

Recommendation #1: Focus the System on Developmental Supports for Young People

States guide the focus of schools and professionals through the ways in which accountability

systems are established, guidance is offered, and funding is provided. To ensure developmentally

healthy school environments, states, districts, and schools can

• Include measures of school climate, social-emotional supports, and school exclusions in

accountability and improvement systems so that these are a focus of schools’ attention

and data are regularly available to guide continuous improvement.

• Adopt standards or other guidance for social, emotional, and cognitive learning that

claries the kinds of competencies students should be helped to develop and the kinds of

practices that can help them accomplish these goals.

• Replace zero tolerance policies regarding school discipline with discipline policies focused

on explicit teaching of social-emotional strategies and restorative discipline practices that

support young people in learning key skills and developing responsibility for themselves

and their community.

• Incorporate educator competencies regarding support for social, emotional, and

cognitive development, as well as restorative practices, into licensing and accreditation

requirements for teachers, administrators, and counseling staff.

• Provide funding for school climate surveys, social-emotional learning and restorative

justice programs, and revamped licensing practices (including appropriate assessments)

to support these reforms. As suggested below, additional investments are needed for

multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS), integrated student services, extended learning, and

professional learning for educators to enable progress within schools.

x LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

Recommendation #2: Design Schools to Provide Settings for Healthy Development

Within a productive policy environment, schools can do more to provide the right kinds of supports

for students if they are also designed to foster strong relationships and provide a holistic approach

to student supports and family engagement. To provide settings for healthy development, educators

and policymakers can:

• Design schools for strong, personalized relationships so that students can be well-known

and supported by creating small schools or learning communities within schools, looping

teachers with students for more than 1 year, creating advisory systems, supporting teaching

teams, and organizing schools with longer grade spans—all of which have been found to

strengthen relationships and improve student attendance, achievement, and attainment.

• Develop schoolwide norms and supports for safe, culturally responsive classroom

communities that provide students with a sense of physical and psychological safety,

afrmation, and belonging, as well as opportunities to learn social, emotional, and

cognitive skills.

• Ensure integrated student supports (ISS) are available to support students’ health,

mental health, and social welfare through community school models or community

partnerships, coupled with parent engagement and restorative justice programs.

• Create multi-tiered systems of support, beginning with universal designs for learning

and personalized teaching, continuing through more intensive academic and non-academic

supports, to ensure that students can receive the right kind of assistance when needed,

without labeling or delays.

• Provide extended learning time to ensure that students do not fall behind, including

skillful tutoring and academic supports, such as Reading Recovery; summer programs to

avoid summer learning loss; and support for homework, mentoring, and enrichment.

• Design outreach to families as part of the core approach to education, including home

visits and exibly scheduled student-teacher-parent conferences to learn from parents

about their children; outreach to involve families in school activities; and regular

communication through positive phone calls home, emails, and text messages.

Recommendation #3: Ensure Educator Learning for Developmentally Supportive Education

Educators need opportunities to learn how to redesign schools and develop practices that support a

positive school climate and healthy, whole child development. To accomplish this critical task, the

state, counties, districts, schools, and educator preparation programs can:

• Invest in educator wellness through strong preparation and mentoring that improve

efcacy and reduce stress, mindfulness and stress management training, social-emotional

learning programs that benet both adults and children, and supportive administration.

• Design pre-service preparation programs for both teachers and administrators that

provide a strong foundation in child and adolescent development and learning; knowledge

of how to create engaging, effective instruction that is culturally responsive; skills

for implementing social-emotional learning and restorative justice programs; and an

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD xi

understanding of how to work with families and community organizations to create a

shared developmentally supportive approach. These should provide supervised clinical

experiences in schools that are good models of developmentally supportive practices that

create a positive school climate for all students. Administrator preparation programs should

help leaders learn how to design and foster such school environments.

• Offer widely available in-service development that helps educators continually build on

and rene student-centered practices, learn to use data about school climate and a wide

range of student outcomes to undertake continuous improvement, problem solve around

the needs of individual children and engage in schoolwide initiatives in collegial teams and

professional learning communities, and learn from other schools through networks, site

visits, and documentation of successes.

• Invest in educator recruitment and retention, including forgivable loans and service

scholarships that support strong preparation, high-retention pathways into the

profession—such as residencies—that diversify the educator workforce, high-quality

mentoring for beginners, and collegial environments for practice. A strong, stable, diverse,

well-prepared teaching and leadership workforce is perhaps the most important ingredient

for a positive school climate that supports effective whole child education.

The emerging science of learning and development makes it clear that a whole child approach

to education, which begins with a positive school climate that afrms and supports all students,

is essential to support academic achievement as well as healthy development. Research and the

wisdom of practice offer signicant insights for policymakers and educators about how to develop

such environments. The challenge ahead is to assemble the whole village—schools, health care

organizations, youth- and family-serving agencies, state and local governments, philanthropists,

and families—to work together to ensure that every young person receives the benet of what is

known about how to support his or her healthy path to a productive future.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD 1

Introduction

New knowledge about human development from neuroscience and the sciences of learning and

development demonstrates that effective learning depends on secure attachments; afrming

relationships; rich, hands-on learning experiences; and explicit integration of social, emotional,

and academic skills. A positive school environment supports students’ growth across all the

developmental pathways—physical, psychological, cognitive, social, and emotional—while it

reduces the stress and anxiety that can create biological impediments to learning. Such an

environment enables a “whole child” approach to education that addresses the distinctive

strengths, needs, and interests of students as they engage in learning.

The Need for a Whole Child Approach to Education

A whole child approach to education is one that recognizes the interrelationships among all areas

of development and designs school policies and practices to support them. These include access to

nutritious food, health care, and social supports; secure relationships; educative and restorative

disciplinary practices; and learning opportunities that are designed to challenge and engage

students while supporting their motivation and self-condence to persevere and succeed. All

aspects of children’s well-being are supported to ensure that learning happens in deep, meaningful,

and lasting ways.

Given that emotions and relationships strongly inuence learning—and that these are byproducts

of how students are treated at school, as well as at home and in their communities—a positive

school climate is at the core of a successful educational experience. School climate—“the quality

and character of school life … [shaped by its] interpersonal relationships, teaching and learning

practices, and organizational structures”

1

—creates the physiological and psychological conditions

for productive learning. When these features of school life are not supportive, student engagement

and learning are undermined.

A productive educational system grounded in

an understanding of the science of learning

and development keeps students in school

and promotes academic results by way of

meaningful and deep learning, and helps

students acquire the social and emotional skills,

habits, and mindsets necessary to be successful

in school and in life beyond. The greater

exibility that has accompanied the Every

Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) allows schools to

craft policies aimed at strengthening students’

sense of purpose and connection to school,

which in turn supports stronger achievement

and attainment.

Given that emotions and

relationships strongly influence

learning—and that these are

byproducts of how students are

treated at school, as well as at

home and in their communities—a

positive school climate is at the

core of a successful educational

experience.

2 LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

In this report, we examine how schools can use effective, research-based practices to create settings

in which students’ healthy growth and development are central to the design of classrooms and

the school as a whole. We describe key ndings from the sciences of learning and development; the

school conditions and practices that should derive from this science, including connections to the

home and community; and the policy strategies that could support these conditions and practices

on a wide scale (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

The Whole Child Ecosystem

S

t

a

t

e

P

o

l

i

c

i

e

s

a

n

d

R

e

s

o

u

r

c

e

s

H

o

m

e

a

n

d

C

o

m

m

u

n

i

t

y

S

c

h

o

o

l

/

L

e

a

d

e

r

s

h

i

p

T

e

a

c

h

e

r

s

Students

The Shifts That Are Needed

One reason for the renewed interest in a whole child approach to learning is that this perspective

on education was largely pushed aside during the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) era. For over

a decade, U.S. education policies focused on how to raise academic achievement as reected

primarily in student test scores often to the exclusion of other goals, such as student health and

welfare; physical, social, emotional, and psychological development; critical and creative thinking;

and communication and collaboration abilities. The result was too often a “drill and kill,” “test

and punish,” and “no excuses” agenda through which many of our nation’s most vulnerable

children experienced a narrowly dened, scripted curriculum and a hostile, compliance-oriented

climate that pushed many out of school.

2

Ironically, the students who would benet most from

the engagement and brain development that comes from a rich education are the least likely to

experience such schooling.

This narrow approach to education was ultimately unsuccessful in supporting meaningful gains

in academic achievement: While state test scores went up in the NCLB era, as schools taught to

multiple-choice tests measuring low-level skills under the threat of sanctions, national scores were

largely at, and U.S. performance on international tests measuring higher order skills declined in

mathematics, reading, science, and problem solving.

3

Furthermore, racial and economic gaps in

achievement and graduation rates are greater in the U.S. than in most industrialized countries.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD 3

Meanwhile, during the era of exclusively test-based accountability, many U.S. schools were not

focused on enabling students to acquire the broader life skills they need or the sense of self to

achieve their full potential. For example, a 2006 study of more than 148,000 6th to 12th graders

found that

• only 29% felt their school provided a caring, encouraging environment;

• less than half reported they had social competencies such as empathy, decision making,

and conict resolution skills (from 29% to 45%, depending on the competency); and

• 30% of high school students engaged in multiple high-risk behaviors such as substance

abuse, sex, violence, and attempted suicide.

4

These conditions contribute to school failure and high dropout rates. Research shows that

punitive approaches to instruction and student treatment undermine student motivation and

learning, and facilitate student disengagement from school. Almost three quarters of a million

students—disproportionately students of color, those with disabilities, and those from low-income

families—do not complete high school each year.

5

Graduation rates for Latinx and African American

students are 15 percentage points lower than those of White and Asian American students.

6

The failure to ensure that these students

graduate from high school negatively impacts

both students and society. High school

graduates have better economic and health

outcomes, are more likely to participate in a

democracy and their community, and are less

likely to engage in criminal activity or require

social services.

7

Graduation rates reect more

than how many students receive a diploma

each year; they are an indication of which

students are more likely to earn a living wage

and escape from poverty. Further, according to research by UCLA’s Civil Rights Project, “every

dropout costs society hundreds of thousands of dollars over the student’s lifetime in lost income.”

8

The consequences of marginalization and the subsequent exclusion of students from educational

opportunity are devastating and lasting for individuals and for society as a whole.

The prospect of signicantly better outcomes is raised by efforts to incorporate into schools what

we have learned from the sciences of learning and development, which conrms the central salience

of a whole child approach.

Research shows that punitive

approaches to instruction and

student treatment undermine

student motivation and

learning, and facilitate student

disengagement from school.

4 LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

Key Lessons From the Sciences of Learning and Development

In recent years, a great deal has been learned about how biology and environment interact to

produce human learning and development. A summary of the research

9

from neuroscience,

developmental science, epigenetics, psychology, sociology, adversity science, resilience science, and

the learning sciences points to the following foundational principles:

1. Development is malleable. People can always learn new skills from birth

through adulthood because the brain never stops growing and changing in

response to experiences and relationships. The nature of these experiences

and relationships matters greatly to the growth of the brain and the

development of skills.

Development is a lifelong process informed by experiences that begins before birth. The brain

develops rapidly during the early years, with nearly 1,000 new neural connections forming every

second, wiring important neural circuits. These connections are enhanced by good nutrition;

positive, afrming interactions and responses; experiences that support a sense of safety and trust

that enables healthy attachment; and experiences that allow for exploration of language and the

physical world. This wiring of the brain establishes a foundation for building more complex skills

and abilities in later years that are important for academics and life more generally.

Another particularly sensitive and intense period of brain construction takes place during

adolescence. During puberty, rapid changes occur in brain development, hormone levels, and

physical development. The parts of the brain associated with social and emotional functioning

mature at a fast pace, while the capacity for decision making and critical thinking emerges over time.

These abilities are most likely to develop fully when children and youth feel emotionally and

physically safe, connected, supported, engaged, and challenged, and when they have robust

opportunities to learn—with rich materials and experiences that allow them to inquire into the

world around them—and equally robust support for learning. Development occurs within concentric

circles of inuence, beginning with the family and extending to the school, the community, and

larger economic and social forces that inuence children’s development directly and indirectly.

2. Variability in human development is the norm, not the exception. The pace

and profile of each child’s development is unique.

The hallmark of development is its variability. Although development generally progresses in

somewhat predictable stages, children begin at different starting points and learn and acquire

skills at different rates and in different ways. Children of precisely the same age are at different

developmental levels in different domains. The shape of each child’s growth is unique, as a function

of biology interacting with experiences and relationships. Furthermore, a child’s best performance,

under conditions of high support and low threat, differs from how he or she performs without such

support or when he or she feels threatened.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD 5

Because each child’s developmental path is unique, there are multiple possible pathways to healthy

learning and development. Rather than assuming all children will respond to the same teaching

approaches equally well, effective teachers personalize supports and intervention for different

children. Supportive schools avoid attaching labels to children or designing learning experiences

around a mythical average. When educators try to force all children to t one sequence or pacing

guide, they miss the opportunity to nurture the individual potential of each child, and they can

cause children (as well as teachers) to adopt counterproductive views about themselves and their

own learning potential that undermine progress. Today, new advances in science hold promise of

better understanding the patterns in children’s variation and for creating learning environments

that more intentionally nurture each child’s potential.

3. Human relationships are the essential ingredient that catalyzes healthy

development and learning.

Supportive, responsive relationships with caring adults from birth into adulthood provide the

foundation for healthy development and learning. Secure relationships have biological as well as

affective signicance. Optimal brain architecture is developed by the presence of warm, consistent

relationships; positive experiences; and positive perceptions of these experiences.

10

Children’s interactions with other people and their environments are the primary process for

development. For example, when an infant reaches out for interaction through eye contact, babble,

or gesture, his mother’s ability to accurately interpret and respond to her baby’s cues affects the

wiring of brain circuits that support later skills. The same process can occur when teachers and

peers respond in supportive ways.

Cognitive scientists at MIT and Harvard have found that conversation between an adult and a child

appears to change the child’s brain, and that this back-and-forth conversation is actually more

critical to language development than merely hearing a greater number of words.

11

The researchers

found that the number of “conversational turns” was more important than the quantity of words

in accounting for differences in brain physiology and language skills among children. This nding

applied to children regardless of parental income or education.

This means that parents and teachers, as well as peers, can support children’s language and brain

development by engaging them in conversation. It also suggests that when classroom environments

allow children to engage in instructional conversations, they can actually grow more cognitively

capable and linguistically adept than when instruction is one-way, with just the teacher talking to

the class. Furthermore, teachers can enhance their students’ development and learning by being

responsive and afrming to the ideas students express.

Supportive, responsive relationships in childhood and adolescence also have an important

protective effect. Research has found that a stable relationship with at least one committed adult

can buffer the potentially negative effects of even serious adversity. These relationships, which

provide emotional security, are characterized by consistency, empathetic communications, modeling

of productive social behaviors, and the ability to accurately perceive and respond to a child’s needs.

6 LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

Because sensitivity to children’s cues is so important, culture is a critical component of the learning

environment. Adults who have the cultural competence to appreciate and understand children’s

verbal and nonverbal communication are better able to get in sync with the child and respond

appropriately. When adults do not respond unconsciously to the negative dominant narratives

about the learning capabilities of students from low-income families, students of color, and

English learners, they are more able to create classrooms in which all students can feel seen and

heard. In this way, cultural competence can help address the impacts of institutionalized racism,

discrimination, and inequality; offset stereotypes; promote the development of positive attitudes

and behaviors; and build condence to support learning in all students.

4. Adversity affects learning—and the way schools respond matters.

Stress is a normal part of healthy development and learning, but excessive stress can throw learning

and development off track and exert profound effects on children’s well-being. School practices can

either exacerbate or buffer the effects of childhood adversity. When threatened, our bodies protect

us via a stress response system. We experience a surge in hormones (cortisol and adrenaline)

that set off a range of physical responses, causing us to be more focused, vigilant, and alert.

When capable assistance arrives to help cope with the threat, the body releases another hormone

(oxytocin), which helps the body quickly return to baseline.

The stress response system functions well when threats are occasional and short-lived, and when

supportive relationships are consistently available to help the system return to a calmer state. But

when adversity is severe or prolonged, or when the counteracting effects of stable relationships are

missing, the body adapts to the continual activation of the stress response system by going on “high

alert” and staying there. This produces excessive levels of cortisol that ood the brain and other vital

organs, disrupting their normal functioning. The stress response system increases heart rate, blood

pressure, inammation, and blood sugar levels—explaining why serious adversity in childhood is

associated with so many poor health outcomes in adults, such as obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and

shortened life spans. It also helps to explain how unbuffered stress can affect educational outcomes:

Traumatic or strongly emotional events can simultaneously inuence the regulation of affect (for

example, feelings of depression or anxiety), physical phenomena (such as heart rate or adrenaline

production), attention, and cognition (for example, executive functioning and memory).

Each year in the United States, 46 million

children are exposed to violence, crime, abuse,

or psychological trauma.

12

Experiencing

these types of adverse childhood experiences

(ACEs)

13

—which also include the impact of

growing up in poverty, such as food and home

insecurity, family illness, or the detention

or incarceration of a family member—

demonstrates a connection to poor health

and educational outcomes, such as increased

absenteeism in school and changes in school

performance.

14

These types of experiences “can

affect sustained and focused attention, making

When adversity is severe

or prolonged, or when the

counteracting effects of stable

relationships are missing, the

body adapts to the continual

activation of the stress response

system by going on “high alert”

and staying there.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD 7

it difcult for a student to remain engaged in school.”

15

Further, “chronic stress can have a negative

effect on the chemical and physical structures of a child’s brain, causing trouble with attention,

concentration, memory, and creativity.”

16

Adversity happens in all communities, and healthy development does as well. However, inequality

creates increased risks. Poverty and racism, together and separately, make the experience of

chronic stress and adversity more likely. In schools where students encounter implicit bias and

stereotyping or punitive discipline tactics rather than supports for handling adversity, their stress

is magnied. Considerable research shows that exclusionary responses, such as suspensions and

expulsions, disproportionately affect students of color from low-income families and students

with disabilities, who receive harsher penalties than those received by other students who engage

in similar behaviors.

17

The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University has identied a common set of actions

schools, families, and communities can take to make it more likely that children will experience

positive outcomes in the face of signicant adversity.

18

These include

• facilitating supportive adult-child relationships that extend over time;

• building a sense of self-efcacy and control by teaching and reinforcing social and

emotional skills that help children handle adversity, such as the ability to calm emotions

and manage responses; and

• creating strong, dependable, supportive routines for both managing classrooms and

checking in on student needs.

5. Learning is social, emotional, and academic.

Emotions and social relationships affect learning. Positive relationships, including trust in the

teacher, and positive emotions, such as interest and excitement, open up the mind to learning.

Negative emotions, such as fear of failure, anxiety, and self-doubt, reduce the capacity of the brain

to process information and to learn.

In addition, children’s abilities to manage their emotions inuence learning. For example, learning

to calm oneself, regulate one’s own behaviors, and focus attention provide the foundation for

learning and the ability to persist with hard tasks and to pursue interests over a longer period

of time. Just as an air trafc control system at a busy airport safely manages the arrivals and

departures of many planes simultaneously, the brain needs this set of skills to resist distractions,

prioritize tasks, set and achieve goals, and control impulses.

Students’ interpersonal skills, including their ability to interact positively with peers and adults, to

resolve conicts, and to work in teams, all contribute to effective learning and lifelong behaviors.

These skills, which build on the development of empathy, awareness of one’s own and others’

feelings, and learned skills for communication and problem solving, can be taught.

Students’ motivation and their “metacognitive skills”—the ability to track and assess their own

learning and understanding—are also important for effective learning. These enable and encourage

students to start and persist at tasks, recognize patterns, evaluate their own learning strategies,

evaluate what works, and invest adequate effort to succeed and to transfer knowledge and skills to

8 LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

increasingly complex problems. Studies have found that adults are more satised with their jobs,

happier with their lives as a whole, and perform better at work when what they do interests them

and matters to people other than themselves. The same is true of students.

Students who have a growth mindset—that is, they believe they can improve through effort, trying

new strategies, and seeking help—are less likely to become discouraged and more likely to try

harder after encountering difculties. They are more likely to tackle tasks at the edge of their

current skills than students who believe their intelligence is xed. This can translate into stronger

performance in school and in other tasks in life as well.

Engagement and effort are supported in classrooms in which children feel they are not typecast or

stereotyped, where they see that they can improve with effort (for example, by revising their work),

where they are respected and valued by their teachers and peers, and where they are working on

things that matter to themselves and others.

6. Children actively construct knowledge based on their experiences,

relationships, and social contexts.

Students dynamically shape their own learning. Learners compare new information to what they

already know in order to create mental models. These mental models enable students to connect

facts to their past experiences and draw inferences about new situations. This process works

best when students actively engage with concepts and knowledge, and when they have multiple

opportunities to connect the knowledge to personally relevant topics and lived experiences. When

learning experiences invite students to be active participants, they gain skills in producing and

working with knowledge to create something useful. Effective teachers act as mentors: setting tasks,

watching and guiding children’s efforts, and offering feedback.

The model of teachers spoon-feeding

information to students is outdated.

Curriculum designs and instructional strategies

can optimize learning by building on each

student’s prior knowledge and experiences,

connecting those experiences to the big ideas

or schema of a discipline, and designing

tasks that are engaging and relevant so

that they spark each student’s interests and

build on what they already know. Providing

opportunities for students to set goals and to assess their own work and that of their peers can

encourage them to become increasingly self-aware, condent, and independent learners. Taken

together, such strategies can challenge and support students to perform at the edge of their

current abilities; help them transfer knowledge and skills to new content areas; and, ultimately,

improve achievement.

When learning experiences invite

students to be active participants,

they gain skills in producing and

working with knowledge to create

something useful.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD 9

Implications for Schools: The Critical Importance of a

Whole Child Framework and a Positive School Climate

While there are many contexts that matter for child development—including families,

neighborhood, and peers—schools play a central role, both directly and indirectly. They create a

developmental context that can be either supportive or nonsupportive for children, and they can

inuence how parents and peers engage with children as well. As American schools are becoming

more diverse—children of color now comprise the majority of public k–12 students—differences

in educational attainment and achievement continue to persist between Black, Latinx, and Native

American youth and their White peers. These young people are also more likely to receive punitive

discipline for similar infractions in schools than their White counterparts, and to be excluded from

schools through suspensions and expulsions, which further widens the achievement gap.

19

Given

these demographic trends and racial gaps in performance and discipline, serving these students’

educational needs is a matter of public policy importance.

The primary goal of k–12 education should be to empower individual students to reach their

full potential. Environments that are relationship-rich and attuned to students’ learning and

developmental needs can buffer students’ stress, foster engagement, and support learning.

Clearly, schools and educators, especially those in high-poverty communities, need the resources

and training to address the many challenges to school attachment and engagement by creating

responsive, supportive, and inclusive learning environments consistent with what we know from

the science of learning and development. As described in this report, the features of such an

environment include

• a caring, culturally responsive community where students are well-known and appreciated,

and can learn in physical and emotional safety;

• positive school conditions and climate, featuring relational trust and respect between and

among staff, students, and parents;

• continuity in relationships, consistency in practices, and predictability in routines that

reduce cognitive load and anxiety and support engaged learning;

• educative and restorative disciplinary practices that support students’ development of

personal and social responsibility;

• meaningful and challenging work for students that engages them in active learning

experiences that are both individualized and social, as needed;

• opportunities to exercise choice and develop intrinsic motivation for learning;

• clear expectations for achievement for students and teachers that convey ideas of worth and

potential, and information about how to meet standards;

• instruction that strategically uses a range of teaching strategies, tools, and technologies to

engage students and meet their individual needs;

• schoolwide practices and instruction that systematically develop students’ social,

emotional, and academic skills, habits, and mindsets;

10 LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

• inquiry and discovery as major learning strategies, thoughtfully interwoven with explicit

instruction and opportunities to practice and apply learning;

• opportunities to receive timely and helpful feedback, develop and exhibit competence, and

revise work to improve;

• ongoing diagnostic assessments that are developmentally guided and informed; and

• a capable and stable staff, supported by effective professional development and connected

to parents and community health and welfare resources, who work together to support

children’s healthy development and learning.

In almost every domain, research nds that the presence of these features produces stronger gains

in outcomes for those students who typically experience the greatest environmental challenges.

This is consistent with developmental science ndings that children who experience adversity

“may be more malleable—and stand to benet most—in the context of supportive, enriched

environmental supports and interventions.”

20

Why a Whole Child Approach Is Essential

A whole child approach to education is premised on the fact that children’s learning depends on

the combination of instructional, relational, and environmental factors the child experiences, along

with the cognitive, social, and emotional processes that inuence one another as they shape the

child’s growth and development.

21

Although our society and our schools often compartmentalize

these processes and treat them as distinct from one another—and treat the child as distinct from

the many contexts she or he experiences—the science of learning and development demonstrates

how tightly interrelated they are and how they jointly produce the outcomes for which educators

are responsible. According to the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD),

a whole child approach means that each student

• enters school healthy and learns about and practices a healthy lifestyle;

• learns in an environment that is physically and emotionally safe for students and adults;

• is actively engaged in learning and is connected to the school and broader community;

• has access to personalized learning and is supported by qualied, caring adults; and

• is challenged academically and prepared for success in college or further study and for

employment and participation in a global environment.

22

To achieve these goals, educators must understand how developmental processes interact and

unfold over time if they are to design supportive environments for development and learning.

Although there are general trends in development, each child develops differently as a function of

his unique qualities and his family, community, and classroom contexts. As a result, schools must be

designed to attend to the unique needs and trajectories of individual children as well as to support

patterns of development, and educators must know how to differentiate instruction and supports to

enable optimal growth in competence, condence, and motivation.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD 11

As we examine strategies schools can use, we emphasize the whole child within a whole-school

and a whole-community context. A blueprint for healthy development must address the many

components needed to enable healthy functioning. From an ecological systems framework

perspective, the school serves as an immediate context shaping children’s learning and

development through instruction, relationships with teachers and peers, and the school culture.

The connection between schools, the home, and community settings is an important additional link

for providing aligned supports for children.

School Climate and Culture: The Foundation for Development

Children learn when they feel safe and supported, and their learning is impaired when they are

fearful, traumatized, or overcome with emotion.

23

Thus, they need both supportive environments

and well-developed abilities to manage stress and cope with the inevitable conicts and frustrations

of school and life beyond school. Therefore, it is important that schools provide a positive learning

environment that provides a measure of security and support that maximizes students’ ability to

learn social and emotional skills as well as academic content.

A positive school environment, also referred to as “school climate,” greatly affects students’ ability

to learn social, emotional, and academic skills. The climate sets the tone at a school and can be seen

in the physical environment, experienced during the learning process, and felt in how people within

the school interact with one another.

24

According to the National School Climate Center,

School climate is based on patterns of students’, parents’ and school personnel’s experience

of school life and reects norms, goals, values, interpersonal relationships, teaching and

learning practices, and organizational structures.

25

The National School Climate Center outlines 13 dimensions (see Table 1) that cover all aspects of

the school environment, ranging from physical and emotional safety and the physical maintenance

of the school building and grounds to relationships, engagement, and a sense of belonging. Many of

these constructs can also be considered “conditions for learning” which enable the development of

students’ social-emotional skills. For example, students need social supports from adults and peers

that help them feel connected to the school before they are able to develop optimism or a growth

mindset. Similarly, students need to feel safe from verbal abuse and bullying in order to develop

strong social awareness and relationship skills. As students and school personnel rene their social

and emotional competence, school climate improves; likewise, a positive school climate creates the

atmosphere within which social and emotional learning can take place.

26

While a school may have a generally positive

climate, it is worth noting that studies have

consistently identied differences among

White students and students of color in their

perceptions of school climate, with youth of

color perceiving less positive school climate

experiences—for example, less favorable

experiences of safety, connectedness,

relationships with adults, and opportunities for

participation—in comparison to their White

peers.

27

As schools become increasingly racially

It is important that schools

provide a positive learning

environment that provides a

measure of security and support

that maximizes students’ ability to

learn social and emotional skills

as well as academic content.

12 LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

Table 1

The National School Climate Center’s 13 Dimensions of School Climate

Dimensions Major Indicators

Safety

1. Rules and Norms Clearly communicated rules about physical violence; clearly

communicated rules about verbal abuse, harassment, and teasing;

clear and consistent enforcement and norms for adult intervention.

2. Sense of Physical Security Sense that students and adults feel safe from physical harm in

the school.

3. Sense of Social-Emotional Security Sense that students feel safe from verbal abuse, teasing,

and exclusion.

Teaching and Learning

4. Support for Learning Use of supportive teaching practices, such as: encouragement

and constructive feedback; varied opportunities to demonstrate

knowledge and skills; support for risk-taking and independent

thinking; atmosphere conducive to dialog and questioning;

academic challenges; and individual attention.

5. Social and Civil Learning Support for the development of social and civic knowledge, skills,

and dispositions including: effective listening, conflict resolution,

self-reflection and emotional regulation, empathy, personal

responsibility, and ethical decision making.

Interpersonal Relationships

6. Respect for Diversity Mutual respect for individual differences (e.g., gender, race, culture,

etc.) at all levels of the school—student-student, adult-student, and

adult-adult—and overall norms for tolerance.

7. Social Support—Adults Pattern of supportive and caring adult relationships for students,

including high expectations for students’ success, willingness to

listen to students and to get to know them as individuals, and

personal concern for students’ problems.

8. Social Support—Students Pattern of supportive peer relationships for students, including:

friendships for socializing, for problems, for academic help,

and for new students.

Institutional Environment

9. School Connectedness/Engagement Positive identification with the school and norms for broad

participation in school life for students, staff, and families.

10. Physical Surroundings Cleanliness, order, and appeal of facilities and adequate

resources and materials.

Social Media

11. Social Media Sense that students feel safe from physical harm, verbal abuse,

teasing, gossip, and exclusion when online or on electronic devices

(for example, Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms;

by an email, text messaging, posting photo/video, etc.).

Staff Only

12. Leadership Administration that creates and communicates a clear vision, and is

accessible to and supportive of school staff and staff development.

13. Professional Relationships Positive attitudes and relationships among school staff that support

effectively working and learning together.

Source: National School Climate Center. https://www.schoolclimate.org/.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD 13

diverse, it is vital that we understand what constitutes positive school climate for youth of color—

one of the most vulnerable groups in terms of the academic and discipline gaps—as well as how to

facilitate improvements in their experiences of school climate.

Schools that effectively support their students create a learning culture and climate that are “both

responsive to the changing needs of the individual and offer the kinds of stimulation that will

propel continued positive growth.”

28

A recent report reviewed 78 school climate studies published since 2000 and found that a positive

school climate can reduce the negative effects of poverty on academic achievement. The authors

conclude that “a more positive school climate is related to improved academic achievement,

beyond the expected level of achievement based on student and school socioeconomic status

backgrounds.”

29

The most important elements of school climate contributing to increased

achievement were associated with teacher-student relationships, including aspects such as warmth,

acceptance, and teacher support.

Another extensive literature review of 327 school climate studies examined research that sought

to connect each of the climate domains to three student outcomes: academic, behavioral, and

psychological and social.

30

With regard to academic outcomes:

• A strong academic climate enabling student learning and achievement is promoted by

high expectations, organized classroom instruction, effective leadership, and teachers who

believe in themselves and promote mastery learning goals.

31

• Support for student psychological needs and academic accomplishment is reected in

higher grades, test scores, and increased motivation to learn and is associated with strong

interpersonal relationships, communication, cohesiveness, and belongingness between

students and teachers.

32

• The structural features of the school, such as school size, physical conditions, and

resources, can also impact student achievement by shaping students’ daily experiences of

personalization, a sense of caring, and the curriculum and instruction they experience.

33

The most successful schools are intentionally

organized, with policies and structures in

place to facilitate all areas of student learning,

thereby empowering educators with the

exibility, support, and opportunities to

implement practices and strategies that are

tailored to the unique needs of students. In

what follows, we discuss in more detail these

policies and structures, as well as the practices

educators can employ to build positive school

climates that will facilitate deep and meaningful

learning for students.

The most important elements

of school climate contributing

to increased achievement were

associated with teacher-student

relationships, including aspects

such as warmth, acceptance, and

teacher support.

14 LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | EDUCATING THE WHOLE CHILD

Strategies for Developing Productive School Environments

To support student achievement, attainment, and behavior, research suggests that schools should

attend to four major domains, shown in Figure 2 and described below:

1. Building a positive school climate in both classrooms and the school as a whole

2. Shaping positive student behaviors through social and emotional learning

3. Developing productive instructional strategies that support motivation, competence, and

self-directed learning

4. Creating individualized supports that address student needs, including the effects of

trauma and adversity

Figure 2

A Framework for Whole Child Education

Whole Child

academic, cognitive, ethical,

physical, psychological,

social-emotional development

Multi-tiered systems

of support (MTSS)

Coordinated access to

integrated services

Extended learning

opportunities

a

n

d

a

d

d

r

e

s

s

l

e

a

r

n

i

n

g

b

a

r

r

i

e

r

s

.

E

n

a

b

l

e

h

e

a

l

t

h

y

d

e

v

e

l

o

p

m

e

n

t

,

m

e

e

t

s

t

u

d

e

n

t

n

e

e

d

s

,

I

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

i

z

e

d

S

u

p

p

o

r

t

s

Educative and restorative

behavioral supports

Development of

positive mindsets

Integration of

social-emotional skills

i

n

t

e

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

s

k

i

l

l

s

,

p

e

r

s

e

v

e

r

a

n

c

e

,

a

n

d

r

e

s

i

l

i

e

n

c

e

.

P

r

o

m

o

t

e

s

t

h

e

s

k

i

l

l

s

,

h

a

b

i

t

s

,

a

n

d

m

i

n

d

s

e

t

s

t

h

a

t

e

n

a

b

l

e

s

e

l

f

-

r

e

g

u

l

a

t

i

o

n

,

S

o

c

i

a

l

a

n

d

E

m

o

t

i

o

n

a

l

D

e

v

e

l

o

p

m

e

n

t

Learning-to-learn

strategies

Conceptual

understanding

and motivation

Student-centered

instruction

a

n

d

d

e

v

e

l

o

p

m

e

t

a

c

o

g

n

i

t

i

v

e

a

b

i

l

i

t

i

e

s

.

C

o

n

n

e

c

t

t

o

s

t

u

d

e

n

t

e

x

p

e

r

i

e

n

c

e

,

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

c

o

n

c

e

p

t

u

a

l

u

n

d

e

r

s

t

a

n

d

i

n

g

,

P

r

o

d

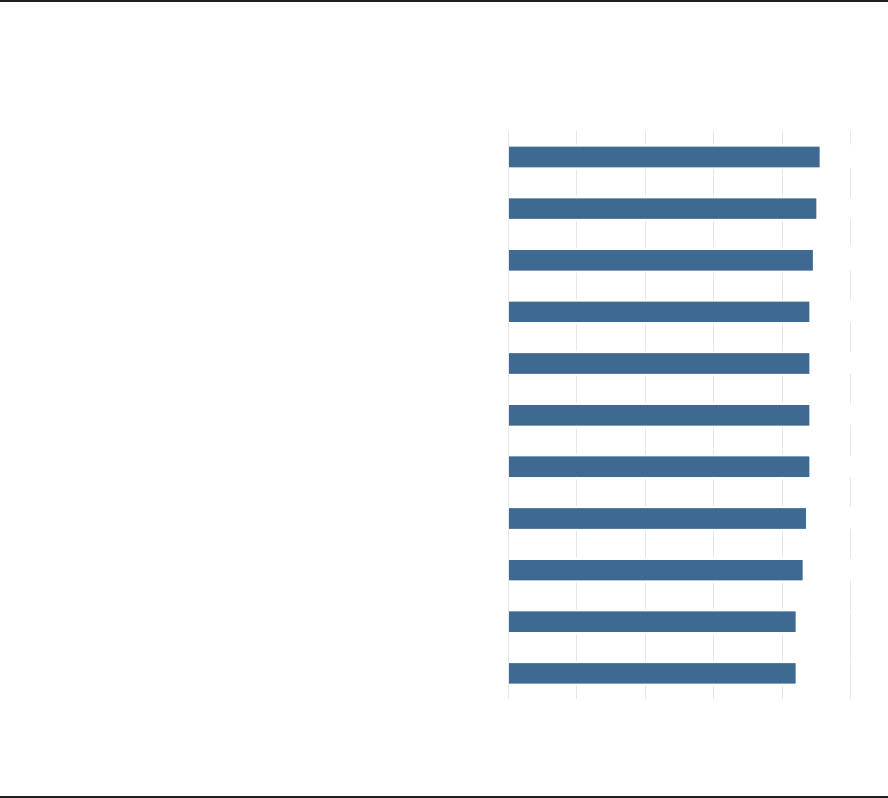

u

c