Repatriation Taxes

∗

Chadwick C. Curtis

†

University of Richmond

Julio Gar´ın

‡

Claremont McKenna College

M. Saif Mehkari

§

University of Richmond

This Draft: April 1, 2019

Abstract

We present a model of a multinational firm to quantify the effects of policy changes

in repatriation tax rates. The framework captures the dynamic responses of the firm

from the time a policy change is anticipated through its enactment, including its long-

run effects. We find that failing to account for anticipatory behavior surrounding a

reduction in repatriation tax rates overstates the amount of profits repatriated from

abroad and underestimates tax revenue losses. We further show that policy changes

have a relatively small impact on hiring and investment decisions if firms have relatively

easy access to credit markets – as is the case for most multinational firms. Finally,

by altering the relative price of holding assets abroad, news of a future reduction in

repatriation tax rates acts as an implicit tax on repatriating funds today. We capture

and quantify this “shadow tax.”

JEL Classification: F23; H25; E60.

Keywords: Tax Reform, Repatriation Taxes, Asset Holding, Corporate Tax.

∗

We are grateful to David Agrawal, Juan Dubra, David Garraty, Erik Johnson, Marios Karabarbounis,

Rob Lester, Johannes Voget, Dave Wildasin, Ahmed Rahman, Mike Pries, Tim Hamilton, and seminar

participants at UC Santa Cruz, Banco Central del Uruguay, Bowdoin College, Federal Reserve Board, In-

ternational Monetary Fund, Instituto de Econom´ıa-FCEA, University of Alabama, Universidad Cat´olica del

Uruguay, University of Kentucky, University of Mississippi, the University of Notre Dame, University of

Richmond, dECON Facultad de Ciencias Sociales UDELAR, the 2018 Asian Meeting of the Econometric

Society, the 23rd Latin American Meeting of the Econometric Society, Virginia Association of Economists

Meeting, International Trade and Finance Association Meeting, Southern Economic Association Meetings,

Liberal Arts Macro Workshop, Asian Meetings of the Econometric Society, Georgetown Center for Economic

Research Conference, the North American Summer Meetings of the Econometric Society, and St. Louis Fed.

Previous versions of the paper circulated as “Uncertain Taxes and the Quantitative Effects of Repatriation

Tax Proposals.”

†

‡

§

1 Introduction

Prior to 2018, the U.S. government collected taxes on the worldwide profits of U.S. based

corporations. In addition to paying foreign taxes on profits earned abroad, corporations were

often also subject to U.S. taxes once these profits were repatriated to the U.S. This is known

as the repatriation tax. Many firms argued that these additional repatriation taxes deterred

them from repatriating foreign sourced income. Leading up to the enactment of U.S. tax

reforms in 2018, these foreign profits, not yet taxed by the U.S. government, stood at over $2

trillion. This large accumulation of assets abroad pushed changing repatriation tax policies

high on the legislative agenda. Motivated by long and ongoing policy discussions, as well

as past and recent repatriation tax policy reforms, we build a dynamic model to quantify

the effects of repatriation tax policy changes on firm-level variables and to understand the

mechanisms driving those responses. Can tax reforms lead to an increase in repatriated

assets? Do these reforms stimulate employment and investment? What are the associated

tax revenue costs? How are the costs and benefits of a reform influenced by protracted

legislative deliberations and policy uncertainty? The goal of this paper is to shed light on

these questions.

While the economic and tax revenue consequences of reforming repatriation tax policy are

potentially large and involve a non-trivial dynamic aspect, the literature, for the most part,

has abstracted from studying the dynamic behavior of the firm that accounts for expectations

of changes in repatriation tax policy. To the best of our knowledge, this paper presents the

first quantitative framework capturing the dynamic impacts of repatriation tax changes that

includes the anticipation effects of such reforms.

We find that accounting for the anticipatory behavior of a firm, along with the responses

after the policy change, is essential to fully understand the effects of repatriation tax policy

changes. In our model, firms respond to news of a repatriation tax policy change in advance

of the actual policy change. Conceptually, we consider news as any information that alters

the likelihood of future repatriation tax changes such as a policy proposal, the deliberation of

a policy, or the legislative lag. Receiving news of a potential future reduction in repatriation

tax rates leads to a reduction of repatriated income from abroad, an accumulation of foreign

assets untaxed by the U.S. government, and a fall in U.S. government tax revenue. At the

enactment of a repatriation tax policy change, firms repatriate back the assets withheld

during this news period – the period between the arrival of news and the policy change.

As in our baseline experiment, modeled after the temporary repatriation tax reduction in

2004-2005, firms additionally bring forward the repatriation of assets that were planned to

be remitted at a future date to the time of the policy change, causing repatriations to once

1

again fall after the implementation of the policy. As a result, policy evaluations that do not

account for a firm’s anticipation of lower future repatriation tax rates overstate the amount

of income repatriated from abroad and the effects on labor and capital, while they understate

the losses in tax revenue.

One of the primary motivations for reforming repatriation tax policy is to incentivize firms

to repatriate assets to the U.S., thereby stimulating domestic employment and investment.

We find that the effects of a reduction in the repatriation tax rate on U.S. employment and

investment crucially depend on the firm’s ability to access external credit markets. When

the cost of accessing credit is high, the firm is more dependent on internal funds to support

production activities. For such a firm, a contraction in repatriations during the news period

corresponds with a large contraction in its U.S. production, and the influx of foreign income

at the time of the policy change leads to a sizable expansion of domestic activity. Since

most multinational firms are large and relatively unconstrained in their access to credit, our

analysis indicates that a repatriation tax rate reduction has a relatively minor impact on

domestic employment and investment. Firms that are not credit constrained are able to

operate close to their optimal scale independent of whether or not they access their foreign

assets. Thus, while a policy change may result in a large inflow of foreign assets, this change

in asset flows does not affect production but primarily affects the firm’s debt position and

shareholder payouts.

Our model consists of a firm that is incorporated in the U.S., but operates and holds

assets both domestically and abroad, with the objective of maximizing dividend streams

paid to U.S. shareholders. Within each country, the firm decides on the levels of capital and

labor required for production, its holdings of liquid financial assets, and the amount of debt

to carry in the U.S. Across geographies, profits originating from abroad and repatriated back

to its U.S. parent are subject to a repatriation tax levied by the U.S. government. Thus,

repatriation taxes play a key role in the across-geography allocation decision. We use this

framework to quantify the impact of repatriation tax changes on the firm’s decisions within

and across geographies.

Our baseline experiment studies the effects of a temporary repatriation tax rate reduction

that is anticipated a year in advance of its implementation. While we consider a range of

repatriation tax policies, this experiment is motivated and disciplined by the American Jobs

Creation Act of 2004 (AJCA), which granted a one-time “tax holiday” on repatriated assets

in 2005. In our model, during the news period the firm reduces the rate of repatriations from

abroad and accumulates foreign assets to maximize its tax savings from the tax holiday. This

reduced flow of assets into the U.S. leads to a small contraction in domestic production and

to losses in U.S. tax revenue. At the enactment of the policy, the accumulated foreign assets

2

flow into the U.S.; the firm then uses the additional inflow of assets to primarily pay U.S.

shareholders, and reduce its debt.

We show that during the period between when a proposal is presented and its (potential)

approval, there is a change in the relative cost of repatriating funds. The period of delibera-

tion can be thought of as a wedge that distorts the firm’s decision relative to the status quo

without these announcements. We capture and quantify this wedge, generated by the news

itself, which we refer to as a “shadow tax.” By altering the intertemporal cost of repatriating

foreign assets, news of a future tax reduction has both an income effect – higher expected

future disposable income induces the firm to repatriate income for dividend payments today

– and a substitution effect – repatriating funds today is relatively more expensive than in

the future.

Prior to 2018, repatriation rates were set as the larger of zero and the difference between

U.S. and foreign tax rates, and by 2017 the top marginal U.S. corporate income tax was

the highest among OECD countries. U.S. repatriation taxes were recently eliminated from

legislation under the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017. However, calls for repatriation tax reform

preceded these reforms by many years. Following the enactment of the AJCA, bills were

introduced to congress nearly every year requesting temporary and/or permanent reductions

in repatriation tax rates. To study the effects of changes in expectations about repatriation

tax reforms that such protracted discussions may introduce, we additionally model news

with uncertainty surrounding when and if a repatriation tax change will occur. We show

that uncertainty in the timing of the policy change generates a ‘wait-and-see’ effect. If the

firm deems that future repatriation tax reform is likely but they are unsure when it will

occur, they steadily accumulate foreign asset holdings, which can persist over a long time

horizon. Even though the intent of the many proposals was to attract offshore assets held

by U.S. firms, the discussions of such proposals arguably had the opposite effect of inducing

firms to further accumulate assets abroad while they await a resolution of policy.

An innovation of our dynamic analysis is the inclusion of the anticipation, or new effects,

of repatriation tax reform. In this regard, we complement models analyzing the impacts of

repatriation taxes such as the static analysis of repatriation/investment decisions from an un-

certain arrival of a tax holiday of De Waegenaere and Sansing (2008), Altshuler and Grubert

(2003)’s theory of tradeoffs between investment and repatriation decisions of multinational

corporations, and the structural model of the relationship between firm-level cash holding

and repatriation tax rates in Gu (2017). In an influential paper, Hartman (1985) argues that

if tax rates on multinational firms were constant across time, the level of repatriation tax

rates would have no impact on the repatriation decisions of mature firms because these taxes

would be unavoidable. In our model, in the absence of an actual policy change, a reduction

3

in repatriations and an increase in the stock of foreign asset holdings only occurs if firms

expect a future repatriation tax reduction.

1

Spencer (2017) investigates the aggregate ef-

fects of a permanent repatriation tax reform. Our papers complement each other in that his

equilibrium environment can draw conclusions on the aggregate and welfare consequences of

permanent repatriation tax changes, whereas our paper focuses on the dynamics surrounding

reforms, including firm level responses to news of a reform. Moreover, our study provides

a richer firm-level environment which allow us to focus on portfolio allocation – cross and

within country – and study the mechanisms and adjustments occurring at the firm level.

Our contribution can also be viewed as a counterpart to the empirical literature looking

at the effects of repatriation tax policy change from the AJCA such as Dharmapala, Foley,

and Forbes (2011), Blouin and Krull (2009) and Faulkender and Petersen (2012). As external

validation of our model, we find that our policy experiments of a one-time repatriation tax

reduction capture the salient features found in these empirical studies.

2

Our paper follows the large literature on fiscal policy news shocks such as House and

Shapiro (2006), Yang (2005), Leeper, Richter, and Walker (2012), and Beaudry and Portier

(2007). We investigate a specific fiscal policy shock – repatriation tax changes – and evaluate

the tax revenue consequences and firm-level responses to the shock across a set of variables.

In this regard, our analysis is closest to the news and uncertainty of future tax policy studied

in Mertens and Ravn (2011) and Stokey (2016). Stokey presents a model with tax uncertainty

that can generate an investment boom after the resolution of the policy. In that environment,

firms reduce investment in new projects and accumulate liquid assets as a ‘wait-and-see’

policy until the uncertainty is settled. We differ from Stokey in two ways. First, ours is

a quantitative study. This allows us to map some objects in our framework to the data.

Second, we allow for firms to access financial markets. Our framework generates similar

dynamics to Stokey but that behavior crucially depends on the firm’s ability to access credit

markets. In our model, allowing the firm to access external and internal financing dampens

the investment effects of news of a policy change. Specifically, in the news period, the

firm finances domestic operations with external financing while simultaneously accumulating

liquid assets abroad.

In the DSGE model of Mertens and Ravn (2011), the economy experiences a contraction

of output and investment in anticipation of a tax cut and then an expansion of these variables

1

Following this literature, we abstract from corporate inversions. We only consider the dynamic effects of

repatriation tax changes rather than long-term decisions of corporate headquarter relocation that, arguably,

may arguably arise from repatriation tax policy. See Gu (2017) for a model analyzing tax revenue estimates

from U.S. inversion law changes.

2

Further, to support our modeling strategy of accounting for policy news, we provide empirical and

narrative evidence suggesting that firms received and responded to information on the passage of the AJCA

prior to its introduction in Congress.

4

once the tax cut is implemented, regardless of whether it was anticipated or not. Whereas

firms in Mertens and Ravn (2011) adjust domestic inputs in response to a tax cut, our focus

on international firms provides an additional margin of adjustment. In our benchmark model,

responses to output and investment to either an anticipated or unanticipated reduction in

the repatriation tax rate are small due to the firm’s ability to borrow and alter asset flows

between domestic and foreign operations. This is consistent with the investment dynamics

found in the empirical literature of the most recent U.S. repatriation tax change under the

AJCA (Dharmapala, Foley, and Forbes, 2011; Faulkender and Petersen, 2012).

2 Model Economy

In this section, we present a dynamic model to capture the effects of changes in repatriation

tax policy. The model economy consists of a multinational firm that is owned by households

and a government that levies taxes on various income sources. The multinational firm is

incorporated in the U.S. but operates and holds assets both in the U.S. and overseas. The

firm faces corporate income taxes in both jurisdictions and repatriation taxes on any income

earned by its foreign operations that are remitted back to the U.S. Thus, a key decision for

the firm consists of a portfolio choice problem of optimally allocating assets between its U.S.

and foreign subsidiary. Since our focus is primarily on how a firm internally reallocates its

assets in response to repatriation tax changes, we do not model the debt vs. equity choice

for external financing. Instead, we assume that the firm only has direct access to one type

of external financing – debt.

3

2.1 Firm

The multinational firm’s objective is to maximize the present discounted value of the stream

of utility from dividend payments, d

t

, to its infinitely lived shareholders. The firm’s objective

function is

E

0

"

∞

X

t=0

β

t

U((1 − τ

d

)d

t

)

#

where τ

d

is the capital gains tax on dividends, U(·) is the flow utility derived from the

after-tax dividend payments with U

0

(·) > 0, U

00

(·) ≤ 0, and β is the subjective discount

factor.

4

3

Furthermore, we focus on firms that already operate across geographies and focus instead on changes

in the scale of cross-border production activities.

4

The curvature in the utility function is important as it generates a motive to smooth dividend payments

over time rather than an erratic stream of payments. We could alternatively generate smooth dividends by

5

t

t+1

Observe the

repatriation tax

rate path, and

the technology

level (z)

Choose how

much to

transfer (T)

between

countries

Choose what fraction

of assets to allocate to

production/financial

assets (A

P

, A

B

)

Hire inputs

(K, L) and

produce

Pay dividends (d)

from gross returns on

production/financial

assets

Begin period

with asset

holdings

(AUS , AF)

End period

with asset

holdings

(A´US , A´F)

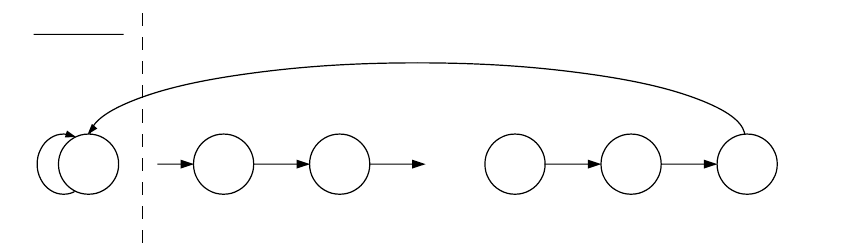

Figure 1: Timeline of Events

The firm enters each period with assets held in the U.S., A

US

, and abroad, A

F

. A

firm observes the current and expected time path of repatriation tax rates as well as the

exogenous total factor productivity level on its U.S. and the foreign subsidiary, z

US

and

z

F

, respectively. Within each period, the firm sequentially makes the following decisions

illustrated in Figure 1. i) First, the firm chooses how to allocate assets between production

and financial assets within each geographical location and decides its debt position. ii) Next,

using assets allocated to production, it hires labor, rents capital, and produces. iii) Finally,

the firm decides how many assets, T, to transfer between its U.S. and foreign operations and

pays dividends. Assets, A

0

US

and A

0

F

, are carried over into the next period. We continue by

formally introducing these decisions.

Within-Geography Asset Allocation Decision

Within each geography, the firm enters the period with internally held assets carried over

from the previous period and decides how to allocate its assets between productive activities

and holding them as interest bearing financial assets. In the U.S., firms can hold financial

assets (A

B

US

> 0) or supplement its assets by taking on debt (A

B

US

< 0). The firm faces a

portfolio allocation problem with the aims of maximizing after tax returns. Formally, the

firm’s intra-period decision for its U.S. based operations is

Π

US

= max

A

P

US

,A

B

US

R

P

US

+

1 + (1 − τ

US

)r

B

A

B

US

(1)

subject to

having risk-neutral investors who are subject to dividend adjustment costs.

6

A

P

US

+ A

B

US

≤ A

US

(2)

A

P

US

≥ 0 (3)

A

B

US

∈ (∞, −∞) (4)

The first term in Equation (1) gives the post-tax returns from assets allocated to production;

the second term is the after-tax returns to financial assets (if A

B

US

> 0) or debt (if A

B

US

< 0),

with r

B

as the interest rate and τ

US

as the U.S. corporate income tax rate. We assume that

the interest rate on borrowed funds, r

B

, is a function of the firm’s global debt-asset ratio. If,

however, financial asset holdings are positive then the interest rate is given by r. Formally:

r

B

=

(

r + ψ

h

exp

|A

B

US

|

A

US

+

˜

A

F

− 1

i

if A

B

US

< 0

r if A

B

US

≥ 0

(5)

where ψ > 0 is the elasticity parameter of debt. This debt-elastic interest rate allows

the firm to leverage its total (U.S. plus foreign) asset holdings to reduce domestic debt

costs. Including a debt-elastic interest rate serves two purposes. First, it ensures there is no

arbitrage opportunity as the firm always faces a debt-elastic interest rate of borrowing that

is higher than the returns it gets on financial assets. Second, it induces stationarity in this

type of model when interest rates are exogenous. Without this, the model’s steady state

depends on the initial debt position and the dynamics feature a random walk component.

5

The firm’s foreign subsidiary faces a nearly identical problem of allocating assets to

maximize gross returns net of the corporate taxes abroad. The only difference is, for clarity

in the analysis, we assume the foreign subsidiary cannot take on debt, i.e. the debt decision

of our model firm is confined to the U.S.

6

The foreign intra-period decision is

Π

F

= max

A

P

F

,

˜

A

B

F

R

P

F

+ [1 + (1 − τ

F

)r] A

B

F

(6)

subject to

A

P

F

+ A

B

F

≤ A

F

(7)

A

P

F

≥ 0 (8)

A

B

F

≥ 0 (9)

5

See, for instance, Schmitt-Groh´e and Uribe (2003).

6

In the Online Appendix, we relax this assumption and show that results are robust to relaxing this

assumption.

7

where the variables are defined similarly as before, but with F subscripts denoting the

decision of the foreign subsidiary.

Production Decisions

Within each geographical location, the firm uses the assets it allocates to production to

hire labor, L, and rent capital, K. The firm’s aim is to maximize the profits of its production

units:

R

P

i

= max

K

i

,L

i

(1 − τ

i

)

Y

i

− wL

i

− r

K

K

i

+ A

P

i

(10)

subject to:

Y

i

= e

z

i

K

α

i

L

η

i

(11)

A

P

i

≥ wL

i

+ r

K

K

i

(12)

z

0

i

= (1 − ρ

z

i

)¯z

i

+ ρ

z

i

z

i

+

z

i

(13)

z

i

∼ N

0, (σ

z

i

)

2

(14)

where i = {US, F }, τ

i

is the country-specific corporate income tax rate, and Y

i

denotes

output. The parameters z

i

, α, and η represent the level of technology, capital share in

production, and labor share in production, respectively. Finally, w is the constant wage rate

and r

K

= r + δ is the capital rental rate with depreciation rate δ.

7

Repatriation and Dividend Decisions

At the end of the period, the firm simultaneously chooses how many assets to transfer

between foreign and U.S. operations, T , the amount of dividends paid to shareholders, and

the amount of assets to carry over to the next period. Consistent with U.S. regulations, all

dividend payments by domestically based corporations must be paid through the U.S. parent

company.

The repatriation tax rate, τ

R

, consists of two components and it is given by

τ

R

= τ +

R

(15)

where τ is the repatriation tax rate set by the U.S. government and

R

is a stochastic

component measuring firm-level idiosyncrasies that may impact the tax rate. Consistent

with the legal environment of U.S. corporations, the repatriation tax rate set by the U.S.

government, τ, is the greater of 0 and the U.S. corporate income tax rate less tax credits

7

The assumption of constant input prices greatly simplifies our analysis. Including positively-sloped

labor supply curves as in Bloom (2009) would dampen the labor responses which would not significantly

change our main results.

8

for taxes paid to the foreign country on overseas earnings, τ = max{0, τ

US

− τ

F

}. The firm-

level idiosyncratic component encompasses many firm-specific idiosyncrasies with respect to

the repatriation tax rate that we do not model, including special tax deductions, earnings

stripping, transfer pricing, R&D credits, income loss deductions, etc.

8

If the firm transfers assets from overseas to the U.S. (T > 0), it must pay repatriation

taxes which results in a net transfer of (1 − τ

R

)T . However, if the transfer is from the U.S.

to overseas (T < 0), then there are no repatriation taxes due and the full amount T is

transferred abroad. This one-sided repatriation tax friction is consistent with: i) prior to

2018, on average U.S. corporate tax rates were higher than those abroad, and thus tax credits

overseas left transfers from the U.S. untaxed, and ii) many countries have a territorial tax

system whereby income earned abroad by domestic firms are not subject to domestic taxes.

9

Given the asymmetry of taxation on transferring assets across geographies, the stock of

assets carried over to the next period are

A

0

US

= Π

US

− d +

e

T (16)

A

0

F

= Π

F

− T (17)

where

e

T =

(

(1 − τ

R

)T if T ≥ 0

T if T < 0

(18)

While the production-side profit maximization problem is a static one, the dividend

decision is dynamic. The multinational firm’s ultimate objective is to maximize the present

value of the stream of utility derived from dividend payments to its shareholders. The

problem can be written recursively:

V (A

US

, A

F

, τ, z

US

, z

F

) =

max

A

0

US

,A

0

F

,T,d

U((1 − τ

d

)d) + βE [V (A

0

US

, A

0

F

, τ

0

, z

0

US

, z

0

F

,

0

R

) |τ, z

US

, z

F

,

R

] (19)

subject to (1)–(18).

8

The sources of heterogeneity are thus generated by idiosyncratic shocks

R

,

z

U S

, and

z

F

rather than,

say, industry competition.

9

For instance, leading up to 2018 the top U.S. marginal corporate income tax was the highest among

OECD countries, and in 2011, over 75 percent of OECD countries had a territorial tax system (Matheson,

Perry, and Veung, 2013).

9

3 Calibration and the Stochastic Steady State

This section first explains how we discipline the model’s parameters. It then describes some

of the model’s primary mechanisms by highlighting its properties in the stochastic steady

state.

3.1 Calibration

We parameterize the model so it matches moments of economic aggregates, country-specific

tax rates, and firm-level data for U.S.-based multinationals. The calibration characterizes the

model in the stochastic steady state where the time period is one quarter. We specify values

for 19 parameters. We begin by assigning preference parameters, common technological

parameters, and parameter values informed by U.S. aggregates. Of the remaining values, 5

are tax parameters and 8 are jointly calibrated.

We assume preferences are logarithmic

10

and the subjective discount factor is β = 0.993.

11

For simplicity, we set the common firm-level parameters to be the same across the two

countries. Since the ratio of labor to capital share in U.S. data is approximately 2, the labor

share, η, is set at 0.5, while the capital share, α, is set at 0.25. This gives an average marginal

cost markup of 33 percent.

The real interest rate on financial assets is set to match the quarterly real interest rate

on the 10 year U.S. T-bond for the period 2000Q1–2014Q4, r = 0.0045 (0.018 annually).

We calculate this as r =

1+i

T −bond

1+E[π]

− 1 where the expected inflation rate, E[π], is the average

inflation in the previous 4 quarters based on the PCE core price index. The capital rental

rate is set as the real interest rate plus depreciation. Letting depreciation δ = 0.02, r

K

=

r + δ = 0.0245.

We are then left with 13 parameters that are more specific to our model economy, which

are set to match relevant moments in the data. These are shown in Table 1.

The values chosen for tax parameters in the model come from four sources: U.S. and

foreign corporate income taxes, taxes paid by households on dividends, and repatriation

taxes. The tax rate on dividends is set to τ

d

= 0.15. This is the U.S. capital gains tax on

long-term assets of the highest 4 tax income brackets in the 2010s (post 2003).

The remaining tax parameters are set to match firm-level data of U.S. multinationals.

We construct firm-level data by matching firm and year specific U.S. marginal corporate

income tax rates from Graham (1996) with corresponding observations in the Compustat

10

In the Online Appendix we perform sensitivity analysis on σ, including the case with linear utility

(σ = 0).

11

This implies a steady state interest rate on debt of 2.06 percent per year in our model.

10

Table 1: Parameter Values

Moments Data Model Parameter

Tax parameters

U.S. marginal corporate income tax rate 0.302 0.302 τ

US

= 0.302

Ave. foreign corporate income tax rate 0.171 0.171 τ

F

= 0.171

U.S. capital gains/dividends tax rate 0.15 0.15 τ

D

= 0.15

Ave. U.S. repatriation tax rate 0.131 0.131 τ = τ

US

− τ

F

= 0.131

Across period variation in firm-level repatriation tax rates ±0.032 ±0.032

R

∼ U(−0.032, 0.032)

Jointly calibrated to firm-level multinational data

Debt to net asset ratio 0.32 0.32 ψ = 0.0009

Ave. number of employees (thousands) 10.22 10.22 w = 0.588

Foreign generated share of total income 0.41 0.41 z

F

= −0.095 (z

US

= 0)

Persistence of U.S. real income 0.76 0.76 ρ

z

US

= 0.889

Persistence of Foreign real income 0.66 0.66 ρ

z

F

= 0.705

Standard deviation of real U.S. output 0.104 0.104 σ

z

US

= 0.019

Standard deviation of real Foreign output 0.105 0.105 σ

z

F

= 0.026

Industrial Database.

12

We restrict our sample to the 2006–2013 period to avoid having the

tax policy changes from the AJCA affecting our estimate of repatriation tax rates absent a

temporary policy change. We further restrict our sample to firm-year entries with positive

foreign and domestic sales and positive foreign taxes.

For a firm i at time t we calculate the repatriation tax rate in the firm-level data as the

maximum of 0 and the difference between the marginal U.S. corporate income tax rate and

the average foreign corporate income tax rate.

13

For firms that face a positive repatriation

tax rate, that is

Repatriation T ax Rate

i,t

=

US Marginal T ax

i,t

−

F oreign Income T ax

i,t

F oreign P retax Income

i,t

.

The average repatriation tax rate in our sample is τ = 0.131. This value is similar to van’t

Riet and Lejour (2014) who estimate the U.S. repatriation tax rate to be between 14.6 and

16.7 percent. Further, splitting up the components of the repatriation tax rate, we have the

average U.S. marginal tax as τ

US

= 0.302 and the mean foreign corporate income tax rate

as τ

F

= 0.171.

Repatriation tax rates by firms in our sample are quite variable from one period to the

next. This may be due to various idiosyncrasies such as tax deductions from losses, various

tax credits, changes in a firm’s marginal tax bracket, and other factors affecting tax rates.

12

The marginal tax rate data is updated through 2013. These tax rates are reported after accounting for

interest deductions and accounts for the dynamics of the tax code such as net operating loss carry forwards

and back, alternative minimum taxes, and investment tax credits.

13

We argue this is an appropriate measure of the repatriation tax because the U.S. tax obligations are

determined by the worldwide averaging of the foreign tax rate. It is also important to note that this may not

necessarily be the repatriation tax rate firms effectively pay (they may choose to not repatriate any income,

for example), but an estimate of the tax rate they would pay if they were to repatriate foreign income.

11

We capture such idiosyncrasies in our model with the stochastic variable

R

. To parameterize

the distribution of

R

, we first assume it to be uniformly distributed. We then calculate the

difference of the 2

nd

highest and 2

nd

lowest repatriation tax rate for the 2006–2013 period

and divide it by each firm’s average repatriation tax rate in this interval.

14

The median value

across firms is 0.489. This gives the bounds on of ±0.032 (0.064/0.131 = 0.489). Formally,

τ

R

= 0.131 +

R

with

R

∼ U(−0.032, 0.032).

The remaining parameters are jointly calibrated to match firm-level cross-sectional and

time-series moments. We again draw upon the firm-level data used in calculating the tax

rate parameters above. Our approach is to discipline the technology shock processes at the

firm level. This requires a longer time-series, so we expand the sample to include 1990–2013.

To maintain consistency with the firms used in the sample to calculate tax rates, a firm again

must have positive U.S. and foreign sales and have a calculated repatriation tax rate. After

this selection, firms must have at least 15 observations. We then calculate real U.S. and

foreign income by firm, deflating the observations by the GDP deflator. Finally, we restrict

observations to have less than an absolute value of 25% change in real income from one-year

to the next to avoid relatively large outliers in our estimation.

Unfortunately, the Compustat data does not separate use of labor and capital by location,

so we infer the model technology processes in the U.S. and abroad by matching moments

of foreign and domestic income. We normalize the technology level in the U.S. to z

US

= 0

(e

z

US

= 1) and z

F

= −0.095 is calibrated to match the median share of foreign to total

income, 0.43. To find the persistence and standard deviation of the AR(1) shock processes,

we first separately normalize the U.S. and foreign firm-year income observations by the

average income in the sample. To remove the trend components and aggregate shocks from

our income series, for each firm and location – U.S. and abroad – we regress a firm-specific

time trend and a year dummy on (normalized) income. We then subtract the predicted from

the observed values to retrieve a stationary firm-level income series. Using this, ρ

z

US

= 0.889

and ρ

z

F

= 0.705 are calibrated to match the median of firm-specific autocorrelations in the

model with the median firm-level income autocorrelations in the data, being 0.76 and 0.66

respectively. We then calibrate the standard deviations of the technology shock processes

in the model as σ

z

US

= 0.019 and σ

z

F

= 0.026 which matches the corresponding median

firm-specific moments the model with the median firm-level standard deviation of income in

the data.

15

Finally, the parameter regulating the elasticity of the interest rate with respect to debt,

14

In this calculation, we require each firm to have 8 continuous observations. We do not use the highest

and lowest observations to avoid potential outliers in our calculations.

15

The model is quarterly while the Compustat data is annual, so we convert the standard deviations to

a quarterly frequency.

12

ψ, is calibrated to match the mean ratio of debt to net assets minus debt, 0.32. We finish

by calibrating w = 0.588 which equates the median firm size in the model, defined as the

number of employees, with that in the data – 10.22 (thousands in the data).

Because of the importance of capturing the non-linearities of the firm’s problem, we rely

on global solution methods. The Appendix discusses the solution method in detail.

3.2 Model in the Steady State

Many of the key insights emerging from our quantitative exercise are best understood by

looking into the steady state properties of the model. Here, we first highlight the impact of

repatriation taxes on asset allocation decisions. We show that foreign liquid asset holdings are

growing in the level of the repatriation tax rate, quantitatively matching previous empirical

findings. We then explore the role of asset holdings on firm-level production decisions which

provides a basis for understanding our dynamic exercises.

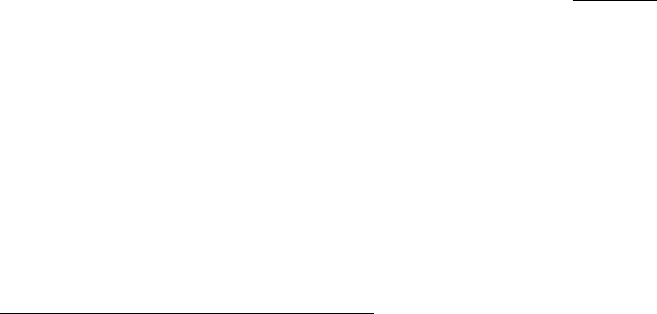

3.2.1 Repatriation Tax Rates and Foreign Assets

Many policymakers voiced concern that high repatriation tax rates encouraged firms to hold

onto foreign earnings – particularly liquid assets – as a vehicle for tax avoidance. Foley,

Hartzell, Titman, and Twite (2007) (henceforth FHTT) empirically document this relation-

ship and find that the amount of foreign liquid asset holdings by U.S. multinationals is

growing in the level of repatriation tax rates faced by the subsidiaries. Here, we compare

this empirical relationship in FHTT with the quantitative implications of our model.

FHTT use confidential firm-level BEA data on foreign subsidiaries of U.S. multinationals

in 4 benchmark surveys from 1982–1999. Their measure of liquid asset holdings by foreign

subsidiaries is the natural log of liquid assets (referred to as “cash”) held abroad divided by

the firm’s net assets (total assets less foreign cash), ln

Cash

Net Assets

. They regress this on the

employment-weighted-effective repatriation tax rate and firm-level controls. This repatriation

tax rate measure is calculated the same way we estimate it in our calibration, except it is

additionally weighted by the share of employees in foreign subsidiaries to total employees

of the firm. The coefficient estimate on the employment-weighted-effective repatriation tax

rate in their specification is 6.83.

16

To obtain the model counterpart of this empirical estimate, we simulate the model econ-

omy at its stochastic steady state at various repatriation tax rates between 0.05 and 0.35,

i.e. τ ∈ {0.05, 0.1, ..., 0.35}.

17

For each tax rate, we simulate 200,000 firms. Consistent with

16

This coefficient is significant at the 5 percent level; see Table 5, Column 3 in Foley, Hartzell, Titman,

and Twite (2007).

17

0.35 is the highest repatriation tax rate a firm could face prior to the U.S. tax reforms in 2017.

13

0 0.05 0.1 0.15

Effective Repatriation Tax Rate (Employment Weighted)

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

Estimate from Foley et al. (2007)

Model predicted values

Figure 2: Foreign Liquid Asset Holdings and Effective Repatriation Tax

Rates (Employment Weighted)

Notes: We follow the estimation in Foley, Hartzell, Titman, and Twite (2007), regressing foreign

ln

Cash

Net Assets

on the employment-weighted-effective repatriation tax rate and controls using our

simulated model data at the firm-level. The predicted values are generated by holding the control

variables at their conditional means. All values are centered at zero by subtracting the mean predicted

value. The slope of the dashed line follows the corresponding coefficient estimate in Foley, Hartzell,

Titman, and Twite (2007) (Table 5, Column 3).

FHTT we calculate, for each firm, the employment-weighted-effective repatriation tax rate.

We then regress ln

Cash

Net Assets

on the this weighted repatriation tax rate and the firm-level

controls used in FHTT.

18

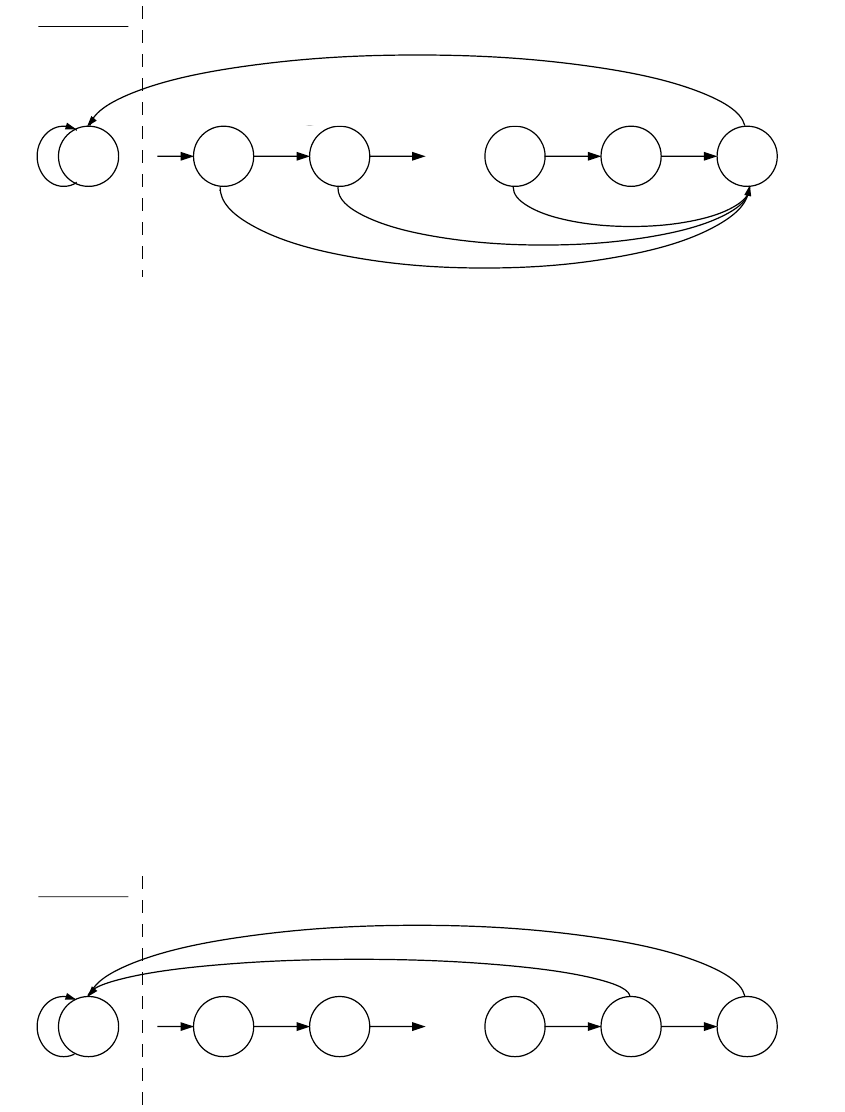

Using the regression estimates from our simulated data, we generate predicted values

of ln

Cash

Net Assets

, holding the control variables at their conditional means. Figure 2 plots

the predicted values of ln

Cash

Net Assets

against the employment weighted repatriation tax rate

at evenly spaced intervals. In the figure, the predicted values are centered around zero by

subtracting the mean predicted value of ln

Cash

Net Assets

from each estimate. For comparison,

the dashed line follows the slope coefficient estimate in FHTT.

Given we did not target this empirical relationship, this exercise (in addition to exercises

in forthcoming sections) provides confidence in the external validity of our framework. More-

over, it also highlights an important channel through which repatriation taxes in the model

provide firms with a motive to hold financial assets abroad. In the model, the stochastic

18

There are three control variables in FHTT for which our model does not have a counterpart: dividend

dummy (due to concave utility, firms always pay dividends in our model), R&D expenditures, and investment.

Details on this regression are in the Online Appendix.

14

element in repatriation tax rates,

R

, induces firms to accumulate foreign financial assets

to await tax saving from a lower realization of

R

(therefore a lower τ

R

). Given positive

borrowing costs, when the underlying repatriation tax rate τ is high, the marginal utility of

shareholders from dividends is also relatively high. In this case, the marginal benefit of tax

saving from a lower realization of

R

is likewise high, leading firms to defer repatriations to

await such a realization. Additionally, recall that in the model foreign asset holdings reduce

domestic debt costs. Repatriation taxes thus induce firms to hold assets up to the point

where the marginal returns on after-tax repatriations equals the marginal cost of debt.

3.2.2 Asset Allocation and Production

Next, we look at the policy functions to understand the production and debt decisions

of the firm. We numerically solve for the policy functions for various levels of the debt-

elastic interest rate parameter ψ, holding firm-level productivity parameters, z

US

and z

F

,

and foreign asset holdings, A

F

, at their mean levels. We interpret ψ as the ease of access to

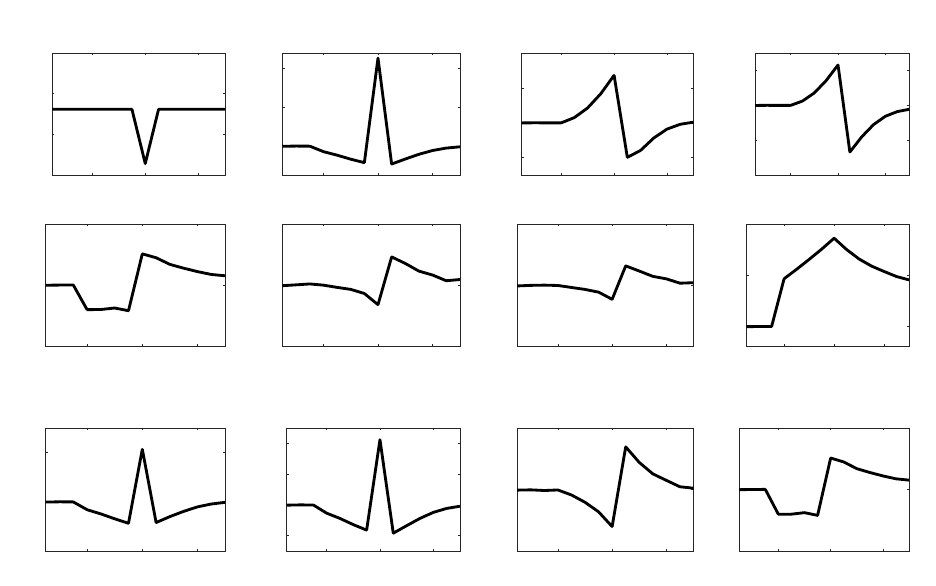

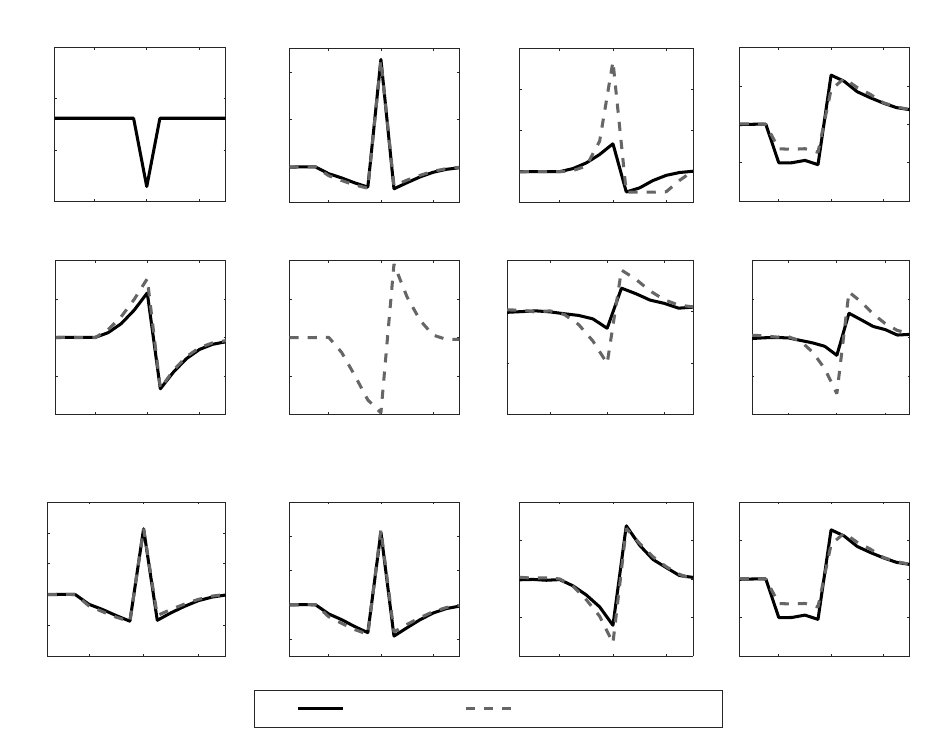

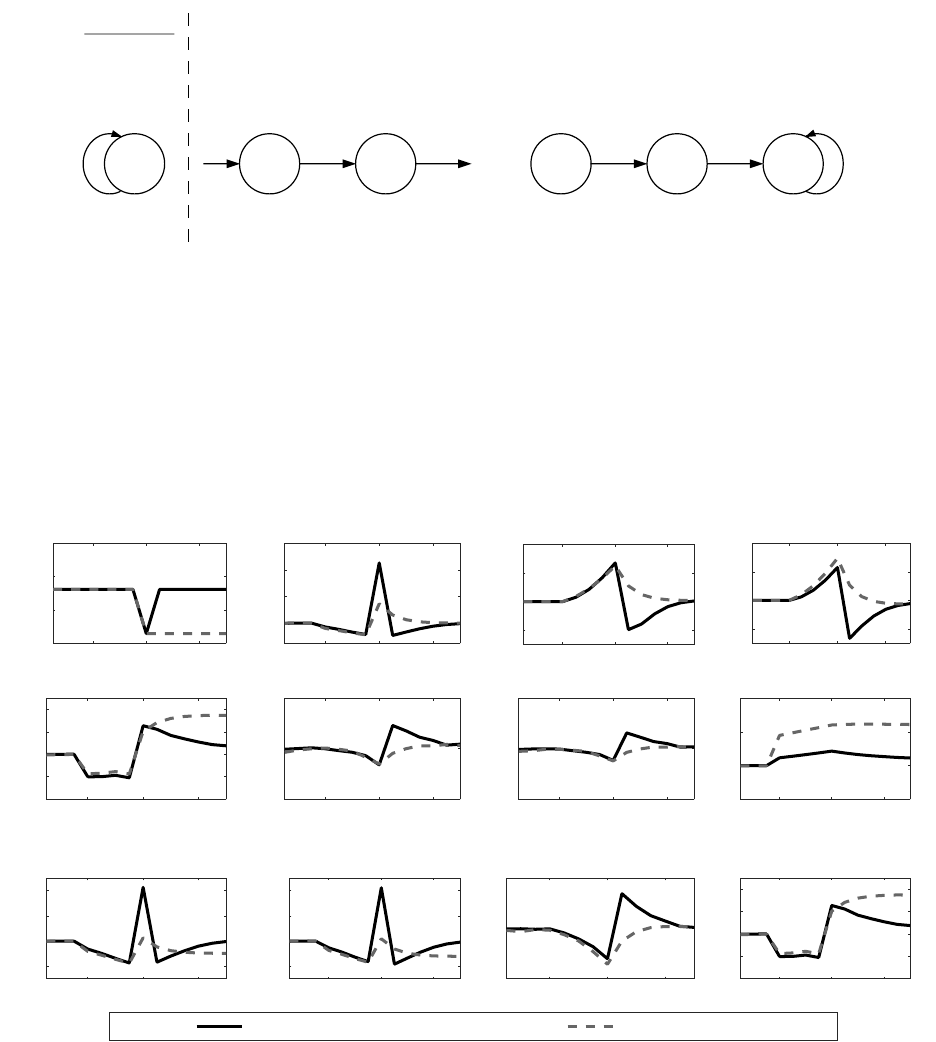

external credit markets. Figure 3 plots the policy functions for U.S. operations of internally

held assets, A

US

, against assets devoted to production, A

P

US

, financial asset holdings, A

B

US

,

and U.S. profits. Here A

B

US

< 0 indicates debt.

We let A

∗

US

denote the level of productive assets when the returns to production equal

the interest rate offered by financial asset holdings.

19

When A

US

< A

∗

US

the firm allocates

all of its internally held assets to production as these offer a relatively higher return. Once

A

US

≥ A

∗

US

, production is at its maximum scale and, because of diminishing returns to scale

in production, all assets A

US

> A

∗

US

are held in interest bearing financial assets.

Looking first at the baseline parameterization of ψ, the total amount of assets devoted

to production is relatively unaffected by the amount of internally held assets A

US

. This

is because the firm may borrow to supplement its productive assets when the returns to

production exceed its borrowing costs (i.e. A

B

US

< 0 when A

US

< A

∗

US

). Profits, although

growing in A

US

, are not substantially impacted by the level of internally held assets due to

the firm’s ability to access debt. Contrast this to the cases when it is more costly to access

external credit (or impossible when ψ = ∞).

20

When internally held assets A

US

< A

∗

US

the

amount of assets devoted to production – and thus profits – are lower than the baseline case.

This is because it is more costly to supplement the shortfall in assets devoted to production

with debt.

These policy functions are instructive when understanding the model exercises of a re-

19

See Equation (20) in the Appendix for the solution to A

∗

U S

.

20

We note that the policy functions of foreign operations mirror the policy functions shown here when

ψ = ∞.

15

0

0

0

0

Figure 3: Policy Functions and Access to External Credit

duction in repatriation tax rates, which, we will see, lend to an influx of foreign assets and

hence an increase in A

US

. As our policy functions illustrate, even large changes in A

US

in

our baseline case will have relatively small impacts on assets devoted to U.S. production

and, by extension, use of capital and labor.

4 Quantitative analysis

This section presents our model dynamics from a temporary repatriation tax rate reduction

– a tax holiday – where the firm receives news of the policy change in advance. We then

compare our model predictions with the empirical findings on the effects of the tax holiday

around the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004. We show that the model is consistent

with this empirical literature and that it can account for a substantial share of the observed

repatriated assets before, during, and after the policy change. Following this, we examine the

importance of news, uncertainty, and access to external credit markets on firm-level behavior

stemming from a repatriation tax policy change.

16

4.1 Baseline Exercise

Our baseline experiment considers a tax holiday that reduces the repatriation tax rate faced

by multinational firms for one period from a steady state level of τ

H

to τ

L

. We further

assume that firms receive news of the tax holiday T periods in advance of its enactment.

This choice for the baseline tax policy is motivated by the American Jobs Creation Act of

2004 (AJCA), the only repatriation tax holiday in U.S. history. The AJCA contained several

tax incentives, including a one-time allowance for firms to bring back assets from abroad at

a reduced repatriation tax rate. For our baseline exercise, consistent with the AJCA, we

reduce repatriation tax rates for one-period from τ

H

= 0.131 to τ

L

= 0.0643.

21

In this exercise, the firm knows with certainty that a tax holiday will occur 4 periods

in advance of the actual tax holiday occurring, i.e. T = 4. Such policy lags are typical for

fiscal policy changes and are crucial to quantifying the full effects of a tax holiday. In our

subsequent discussion, we refer to these policy lags – the periods between when the firm

begins anticipating a future tax holiday and when it is implemented – as the news periods.

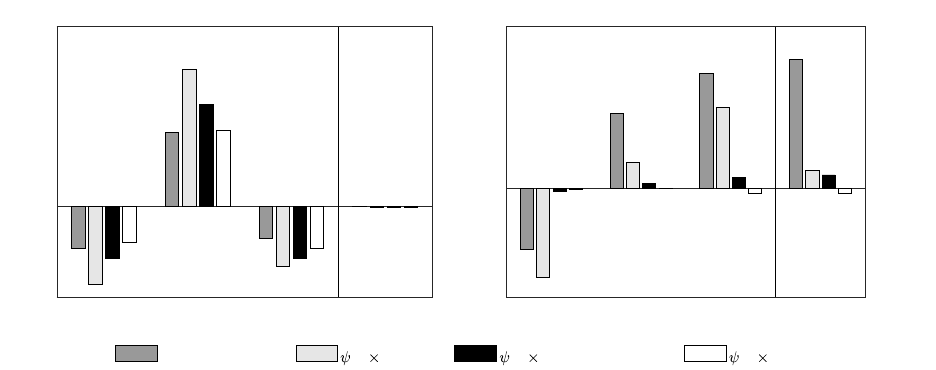

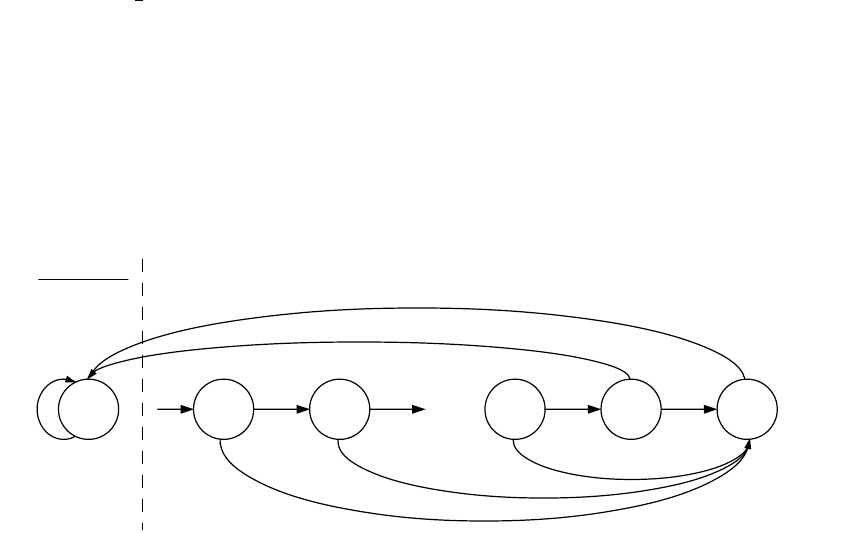

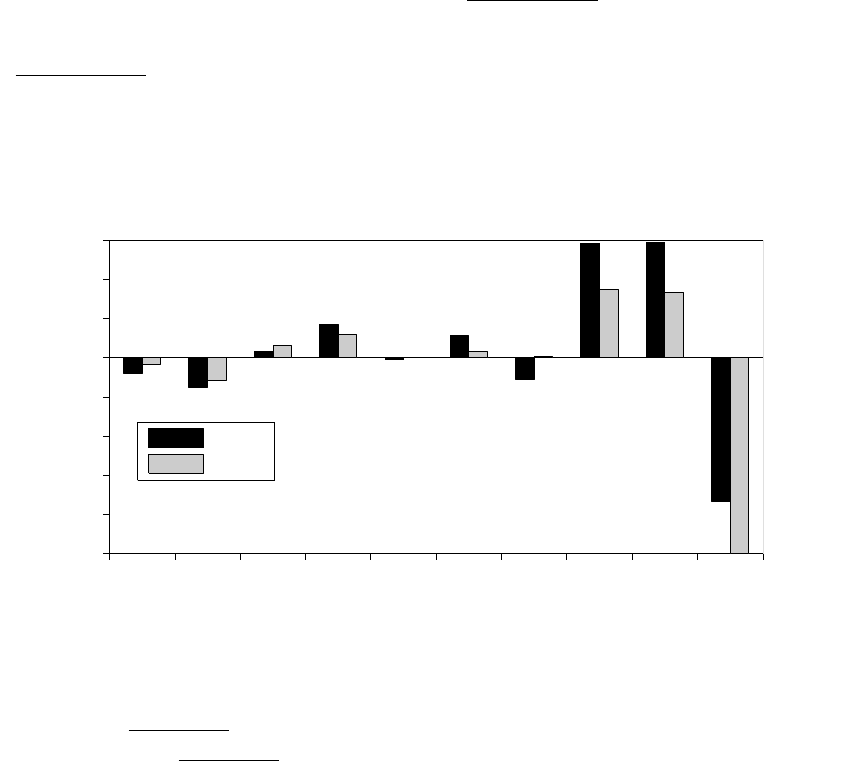

Figure 4 presents the responses to news of, and implementation of, a tax holiday per

our baseline policy. The plots are the average responses of the multinational firms that we

model, and there is not economy-wide aggregation. Throughout, panels and results labeled

as “U.S.” refer to the average responses to U.S. variables. Panel A gives the firm-level

responses and panel B gives the responses for the U.S. government’s tax revenue collected

from these firms. The units are percentage deviations from the original stochastic steady

state with the exception of the repatriation tax rate graph, which shows the actual time-

path for the repatriation tax rate. The tax holiday is implemented at period 0 and the firm

receives news of it 4 quarters in advance (period -4).

It is most instructive to discuss our results by dividing the effects of our baseline repa-

triation tax holiday into three separate sub-intervals: the news period (pre-realization, from

periods -4 to -1), the period of the tax holiday (at-realization, period 0), and the periods

thereafter (post-realization, period 1 onwards). On receiving news about an imminent future

tax holiday, during the news period the firm cuts back on repatriations from their foreign

subsidiary as they await more favorable repatriation tax rates. This leads to an accumu-

lation of financial assets abroad. In the U.S., the firm compensates for this reduction in

transfers by issuing debt. However, since borrowing is not costless, the U.S. operations are

21

Under the AJCA, firms were allowed a maximum tax rate on overseas earnings of 5.25 percent on 85

percent of repatriated funds. The remaining 15 percent of funds faced their ‘normal’ repatriation tax rate,

0.131. The average repatriation tax rate on our model firms in the tax holiday is thus 0.85 × 0.0525 +

0.15 × 0.131 = 0.0643. Kleinbard and Driessen (2008) note that additional tax credits toward the effective

tax rate on funds receiving tax breaks under the AJCA was 3.65 percent rather than 5.25 percent. Since we

do not explicitly model additional foreign tax credits, we use the 5.25 percent rate in our calculation.

17

-4 0 4

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

Repatriation tax rate

-4 0 4

0

200

400

Repatriations

-4 0 4

-100

0

100

200

Foreign financial assets

-4 0 4

-100

-50

0

50

U.S. debt

-4 0 4

-5

0

5

Dividends

-4 0 4

-1

0

1

U.S. labor and capital

-4 0 4

-1

0

1

U.S. output

-4 0 4

0

0.5

1

Firm value (V)

-4 0 4

-20

0

20

All sources

-4 0 4

-100

0

100

200

Repatriations

-4 0 4

-1

0

1

Corporate income

-4 0 4

-5

0

5

Dividends

Panel A: Firm-level responses

Panel B: US tax revenue by source

Figure 4: Responses to an Announced Temporary Reduction in Repatriation Taxes

Notes: News of tax reduction is received 4 quarters in advance. Except for the repatriation tax rate, units are in percent

deviation from initial steady state.

unable to fully make up for the entire fall in assets and thus have to cut back on dividend

payments and assets devoted to production. The fall in U.S. capital and labor is quite small

at approximately 3/10 of 1 percent.

In the period of implementation, the firm takes advantage of the one-time tax holiday

and repatriates a large amount of foreign assets to the U.S. The amount of repatriated assets

contains not only the financial assets the firm accumulated abroad during the news period,

but to take maximum benefit of the tax holiday the firm also brings forward planned future

transfers to the period of implementation. The U.S. operations then use this large inflow of

funds from abroad to pay higher dividends, reduce debt, and increase production.

After the tax holiday period, the firm reduces transfers and reaccumulates assets abroad

toward returning to their steady state level. In the U.S., the firm uses the large influx of

assets from the tax holiday period to temporarily sustain higher dividend payments, higher

production, and debt reduction.

Next, with respect to share value and dividend payments, the announcement of a tax

holiday signals a lower tax obligation in the future, which causes an instant increase in the

firm’s value at the time of the news. The value of the firm continues to rise within the

18

news period up to the realization period, after which it slowly returns to steady state as

the tax-savings from the tax holiday are eventually paid out as dividends. Further, during

the news period, even though dividends are cut back they are still positive. When the firm

foresees a future tax reduction, they accumulate foreign financial assets while simultaneously

issuing domestic debt to smooth out dividend payments. This behavior is consistent with

the observation that several companies (Apple Inc., Ford Motor Co., Caterpillar Inc., for

instance) have relied on bond issuance to finance dividend payments while simultaneously

amassing large sums of untaxed assets abroad.

On the U.S. government side, in Panel B, the collection of tax revenues on repatriated

assets, corporate income, and dividends mirror the transition path of their respective tax

sources.

22

The responses of tax revenues from corporate income and dividends are small

relative to that of transfers. Since the firm uses debt to smooth out U.S. production and

dividend payments, the magnitude of the impact from transfers is the primary force governing

the changes in tax revenues from all sources.

4.2 The American Jobs Creation Act of 2004

Our baseline calibration was informed by the actual tax rate reduction from the AJCA,

leading to a natural benchmark from which to judge the validity of our framework. Here we

compare our baseline results directly with the main findings from the empirical literature

that evaluates the impact of the AJCA.

23

Our model is able to explain key empirical findings

surrounding the AJCA. We also present suggestive evidence that firms both anticipated

and reacted to the tax holiday provision in the AJCA well before it was signed into law.

Furthermore, the effects of policy lasted for several quarters after the end of the tax holiday.

This evidence lends support to the importance of accounting for the full dynamics in any

analysis of repatriation tax policy reform.

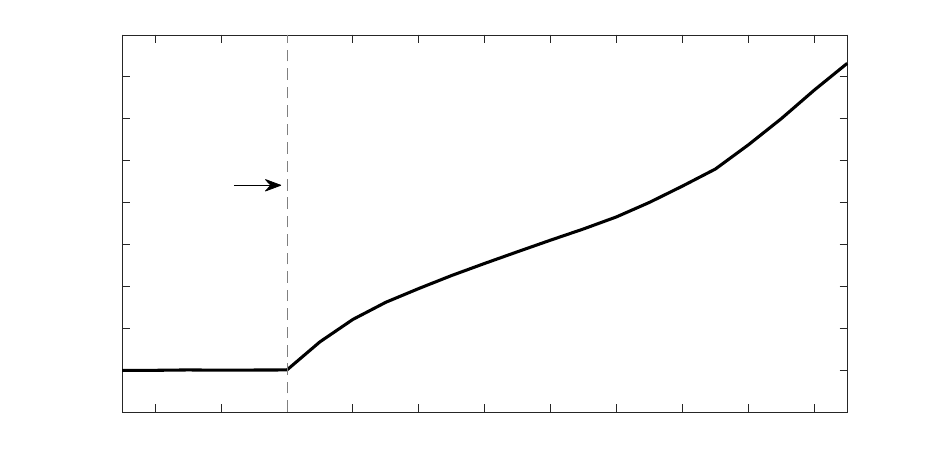

It is estimated that under the AJCA tax holiday approximately $312 billion of qualified

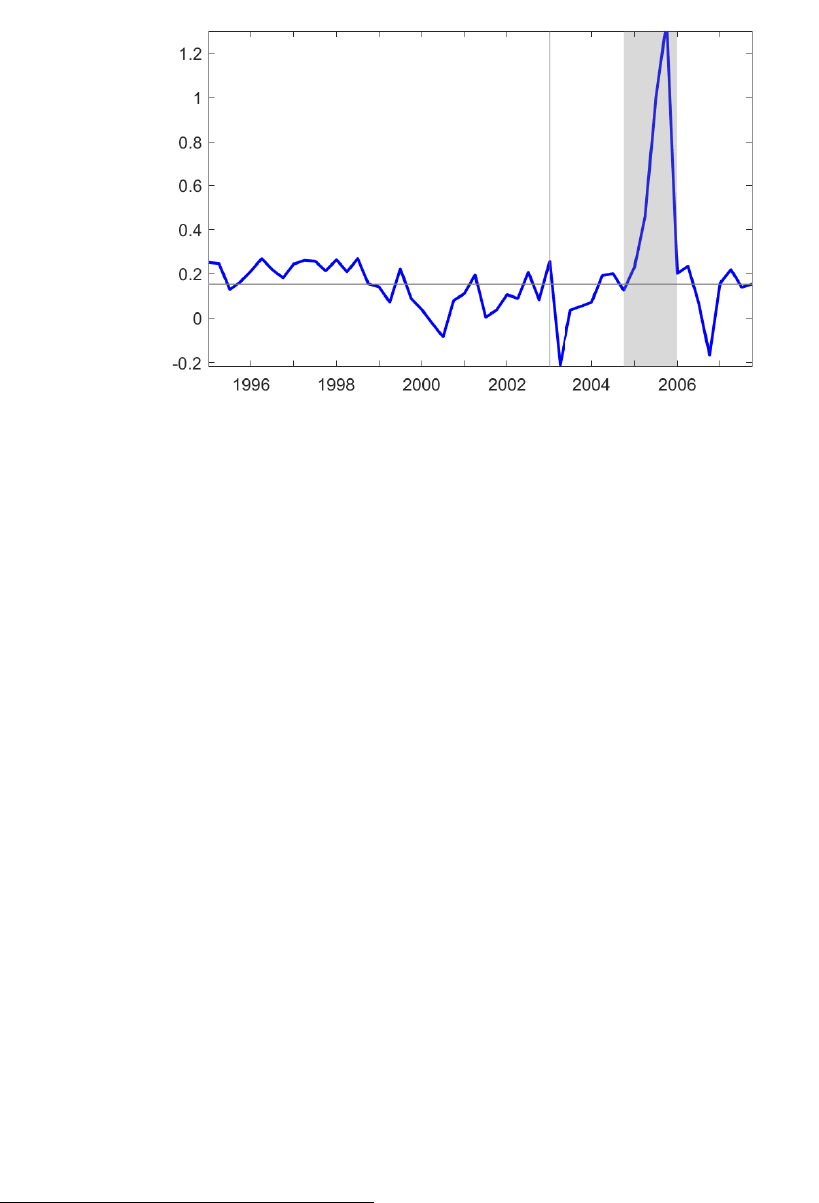

earnings were repatriated to the U.S. (Redmiles, 2008). Figure 5 shows net repatriated

dividends from foreign subsidiaries to U.S. based parent companies as a share of foreign

corporate profits in the years around the AJCA. The shaded area is the effective period of the

tax holiday

24

and the horizontal line - at 15% – is the average from 1995-2003. Net repatriated

22

Our model does not incorporate profit shifting – attributing U.S. value added to foreign affiliates – for

tax purposes (see Guvenen, Mataloni Jr, Rassier, and Ruhl (2017)). If our model included opportunities for

profit shifting, profit shifting could increase if firms anticipate a repatriation tax rate reduction. While this

would not affect real variables, it may amplify the responses to tax revenues.

23

A summary of this literature is in the Online Appendix. This literature, surprisingly, generally does

not consider the anticipatory effects of repatriation tax policy changes.

24

Due to misalignment of fiscal to calendar years, some firms were allowed tax breaks on repatriated

income extending into 2006Q1.

19

Figure 5: Transfers: Net Repatriations of U.S. Incorporated Companies

as a Share of Foreign Profits

Notes: Constructed using Balance of Payments data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

dividends as a share of corporate profits had never exceeded 26% prior to the enactment of

the law, but reached 130% in the final quarter of the tax holiday before sharply falling below

its average level just following the repatriation tax holiday. The fall in repatriations after the

tax holiday was anticipated by policy makers. The Joint Committee on Taxation predicted

firms would shift repatriated earnings they would otherwise have repatriated in future years

to the tax-holiday period to get more favorable rates (Kleinbard and Driessen, 2008). This

is the same mechanism that causes repatriations to fall after the tax holiday in our model.

Despite the influx of liquidity during the tax holiday, the general consensus in the lit-

erature is that the AJCA’s objective of stimulating employment and investment were not

met. Dharmapala, Foley, and Forbes (2011) find that repatriations had no significant im-

pact on U.S. investment or employment, as did Clemons and Kinney (2008) with regards to

investment.

25

Faulkender and Petersen (2012) echo these findings and show that financially

unconstrained firms, which repatriated 73% of all qualified funds, did not alter domestic

employment or investment.

26

Additionally, under the AJCA, funds receiving tax breaks were prohibited from being

used for shareholder payouts (dividends and share buybacks). However, in an evaluation of

the proposed tax holiday released a year prior to the AJCA, a Congressional Research Service

report noted that due to the fungibility of internal funds, firms could channel the repatriated

25

Further, of the top 15 repatriating corporations, 10 actually reported a decrease in U.S. jobs from

2004-2007 (Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, 2011).

26

However, Faulkender and Petersen (2012) also document that financially constrained firms did increase

investment, but still not employment, in response to the act. We return to this point in Section 4.5.

20

funds from a tax holiday to investment while switching domestic funds to shareholder payouts

(Brumbaugh, 2003). Studies on the AJCA have, in fact, found that the tax holiday was

associated with an increase in payments to shareholders (Blouin and Krull, 2009; Clemons

and Kinney, 2008). Dharmapala, Foley, and Forbes (2011) estimate that a $1 increase

in repatriation during the AJCA tax holiday corresponded with a $0.60–$0.92 increase in

shareholder payouts. In our model we can do a similar calculation. Relative to the steady

state, in the five-year window around the tax holiday (including the news period) in our

model, a $1 increase in after tax repatriations corresponds with a $0.74 increase in dividend

payouts. This is in the middle of the range found by Dharmapala, Foley, and Forbes (2011).

Studies on the impacts of the AJCA have primarily focused on its impact only at and

after its enactment. However, we argue that to correctly quantify the effects of the AJCA,

one must also account for any anticipatory effects that may have occurred, i.e. the impacts

during the news period. In the case of the AJCA, there were a series of earlier bills beginning

in February 2003 that did not pass through congress but contained the tax holiday provisions

that were later incorporated in the AJCA.

27

In the time leading up to the AJCA, there is evidence that these earlier bills did lead

to anticipation of the tax holiday. For example, in 2003 Lehman Brothers’ tax accounting

analyst Robert Wilkens indicated that legislation allowing companies to repatriate foreign

earnings was “gaining momentum” and was likely to be passed into law in early 2004 (Cor-

porate Financing Week, 2003). Other examples of anticipation of the tax holiday include

Simpson and Wells (2003) who discuss firms’ lobbying efforts for a tax holiday in 2003 citing

provisions that would eventually be enacted in the AJCA and Sullivan (2004) who question

if foreign income shifting in the years leading up through 2002 are related to tax holiday

proposals in congress. Oler, Shevlin, and Wilson (2007) find that in 2003, well before the

introduction and passage of the AJCA but when a future tax holiday seemed likely, stock

prices had started reflecting potential tax savings from a tax holiday. This is a result that is

mimicked by our model; stock prices rise in the news period in anticipation of a future tax

holiday (see Figure 4).

In our model, expectations of a reduction of repatriation tax costs lead firm to reduce

repatriations until the policy’s resolution. We find that the behavior of firms, in the period

before the AJCA, was consistent with that anticipatory effect. Returning to Figure 5, the

27

Lobbying efforts had long called for tax breaks on repatriated income, but the call for a tax holiday

gained legitimacy in February 2003 with the introduction of the Homeland Investment Act of 2003 to the

House of Representatives, the Invest in America Act of 2003 presented to the House in March, and the Invest

in the USA Act of 2003 introduced in the Senate in the same month. These bills included similar provisions

for the tax holiday included in the AJCA of 2004. Under the AJCA of 2004, 85 percent of repatriated

earnings would qualify for tax exemptions, the same as in the Invest in the USA Act of 2003. A later bill

introduced in November 2003, The American Jobs Creation Act of 2003, also contained similar language.

21

Table 2: Cumulative Percent Deviation from Average Net

Repatriations as a Share of Foreign Profits (Quarterly Rate)

Sub-Period

News Period AJCA Post-AJCA

(2003Q2-2004Q3) (2004Q4-2006Q1) (2006Q2-20017Q1)

Data -63.65 258.08 -53.43

Model -49.72 106.02 -61.89

notes: Figures are percent deviation of net repatriations as a share of foreign profits relative

to their average. In the data, this is the average from 1995Q1-2003Q1. In the model the

average is the steady state level of the corresponding measure. Figures are expressed as

quarterly rates.

vertical line in 2003Q1 marks the time the first bill leading up to the AJCA was introduced

(the Homeland Investment Act of 2003 ). The following quarter, net repatriated dividends

fell to their lowest point in the 13 year sample.

Table 2 compares our model findings with repatriation behavior in the data. We calculate

– in both the empirical and in the simulated data – the percent deviation of net repatriations

as a share of foreign profits from its average level. We then cumulate it into 3 sub-periods:

6 quarters of the news period beginning with the introduction of the Homeland Investment

Act of 2003, 6 quarters of the effective period of the AJCA, and 4 quarters after the policy.

All of the numbers are expressed as quarterly rates. For consistency in the comparison, we

rerun our baseline model but alter its timing to be consistent with the AJCA – a 6 quarter

news period and a 6 quarter tax holiday.

Quantitatively, the model matches the data very closely in the news period and in the time

following the tax holiday. During the tax holiday, in both the data and model, repatriations

are significantly higher with the model capturing over 40 percent of this observed increase

during the AJCA. Overall, even though not constructed to explain the AJCA, our model is

able to account for various features of the data and the empirical results surrounding the

AJCA.

4.3 Discussion On General Equilibrium

While our focus is to understand the mechanisms driving within and cross-country asset

allocation of the firm in response to a change in repatriation taxes, before proceeding it

is important to note the limitations of our study when drawing aggregate implications.

Specifically, by lacking general equilibrium, our model economy does not capture indirect

effects that may occur via price adjustments and/or changes in resource allocation.

In our model, as firms adjust their demand for inputs in response to the policy change,

22

input prices would adjust from changes in economy-wide demand. Likely, these price adjust-

ments in factor inputs would also serve to dampen the responses to labor/capital and output

in comparison to the already relatively small responses in our baseline model. Moreover, in

general equilibrium the asset flows into the U.S. in response to a tax holiday would make

consumers wealthier – from an influx of dividends and/or higher factor payments – and result

in an increase in demand for goods and services. Again, we would argue changes in factor

payments due to repatriations would be relatively small, causing the income and demand

change from this channel to be small. Dividend payments in our model, on the other hand,

fall in anticipation of, and increase at the time of, the tax change. The total effects from this

channel would rely on how large the tax saving on dividends is and how large of a portion

dividend payments from multinational firms make up of total household income.

In the end, the aggregate responses would also depend on the extent to which wealth

effects are assumed in household preferences. What is clear, however, is that the aggregate

and welfare effects of repatriation taxes would necessitate a general equilibrium to be prop-

erly quantitatively evaluated. When we consider a permanent reduction in repatriation tax

rates, the general equilibrium effects would be more important to incorporate as there may

exist long-run efficiency gains following a permanent reduction in distortionary taxes.

28,29

Our framework, nevertheless, highlights important mechanisms at the firm level that are

consistent with the empirical literature that such a framework should capture.

4.4 News Effects

Policy analysis generally focuses on the effects of a repatriation tax policy change only at

and after its enactment. For example, assessments of the AJCA such as the Joint Committee

on Taxation (2004) estimated the tax holiday provision in the AJCA would result in $2.8

billion in revenue gains during the holiday and over $6 billion in losses over the next 9 years.

The news period was not included in the assessment of the AJCA. In this section, we show

that the responses in the news period are large and, to ensure an accurate assessment of

any policy change, the entire dynamics surrounding the policy change should be taken into

account.

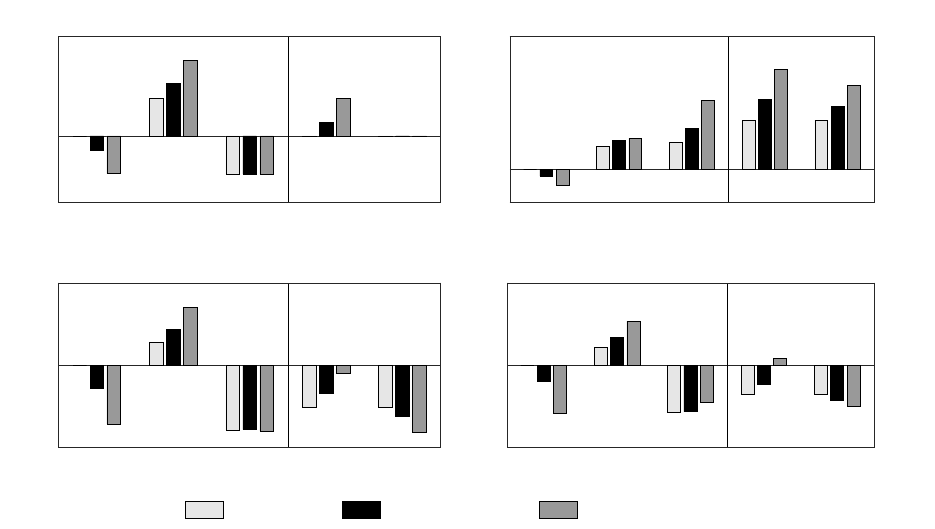

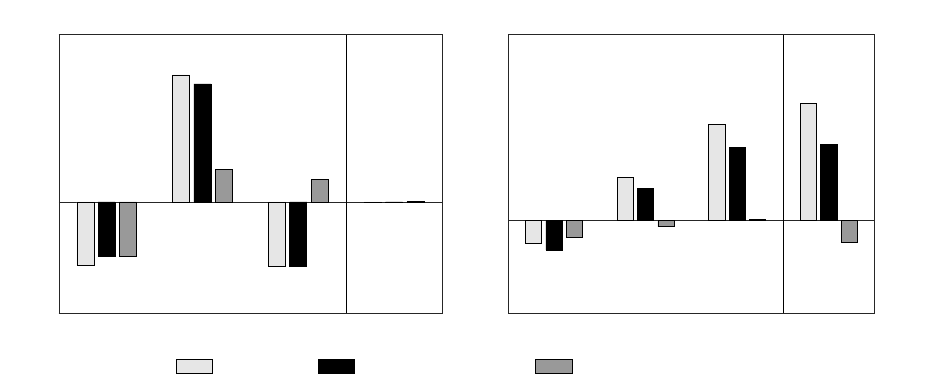

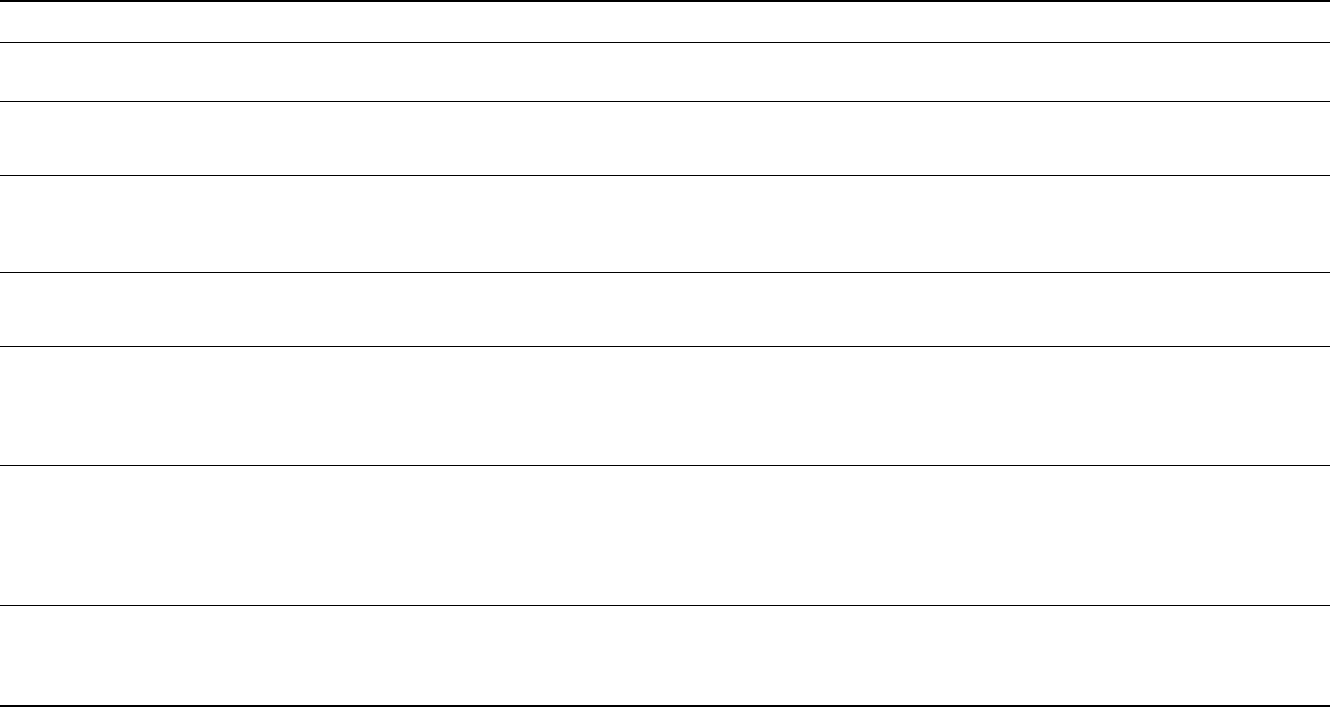

Figure 6 reports the cumulative responses of a tax holiday for several variables of interest.

Each plot also subdivides the cumulative responses into three sub-periods: pre-realization,

at-realization, post-realization. Additionally, we also report just the post-news cumulative

28

See, for example, Spencer (2017) for a general equilibrium model with permanent repatriation tax

changes.

29

Section OA5 of the Online Appendix considers a permanent reduction in repatriation taxes (and a

further discussion of general equilibrium effects from this permanent change) as well as the permanent tax

reform from the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017.

23

Repatriations

Pre At Post Post-news Total

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

Realization period Cumulative

U.S. labor and capital

Pre At Post Post-news Total

-0.005

0

0.005

0.01

0.015

0.02

Realization period Cumulative

U.S. repatriation tax revenue

Pre At Post Post-news Total

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

Realization period Cumulative

U.S. tax revenue: all sources

Pre At Post Post-news Total

-0.4

-0.2

0

0.2

0.4

Realization period Cumulative

no news news period=1 news period=4 (baseline)

Figure 6: Cumulative Responses to a Tax Holiday

Notes: The cumulative effects are shown news periods for when there is no news period and when the news period is 1 and 4

quarters long. The figures subdivide the cumulative responses in the three realization periods: Pre-realization, At-realization,

and Post-realization. This also shows the Post-news cumulative (sum of At- and Post-realization periods) and the total response

(sum of all subperiods). Units are quarterly gain/losses to that variable relative to the steady state at the time of the news.

response (the sum of the at-realization and post-realization responses) to highlight the im-

plications of a policy analysis that focuses only on the responses at and after a policy change.

For the figure, the units are quarterly gains/losses to that variable relative to the steady state

at the time of the news. For example, a cumulative value of -1 to tax revenues indicates

that total tax revenue losses are equal to 1 quarter’s worth of steady state tax revenues.

We further show the results for three simulations differing in the length of the news period:

when there is no news period and when the news period is 1 and 4 quarters long.

Consider first the cumulative impacts in the baseline case, i.e. news period is equal to 4.

On net, repatriations fall in the news period, rise during the tax holiday, and fall thereafter. If

an assessment of the tax holiday on repatriations only considers the total effects at and after

its implementation, it shows a net gain of over 2 quarter’s worth of steady state repatriations.

When all periods are taken into account, including the news period, cumulative repatriations

are negligible: the policy change merely shifts the timing of transfers, which would have been

repatriated anyway, to the time of the tax holiday.

In the baseline case, there are cumulative gains to U.S. capital and labor. The total gains

to these variables are 1.3 percent of their quarterly steady state levels. If the news period

24

is not taken into account, these gains are overstated. On the government side, there are

net losses to U.S. tax revenues. However, looking at this set of firms, the tax holiday would

appear to be approximately revenue neutral if the news period were not taken into account.

Furthermore, we find that the longer the news period the larger the losses to U.S. tax

revenue. A longer news period allows the firm to take maximum advantage of the tax holiday

by holding back a large amount of assets during the news period and then repatriating a

large amount during the tax holiday. This larger repatriation in turn leads to an overall

larger cumulative gain in the U.S. capital and labor, but at the same time also leads to

a larger revenue loss by the government. Thus, there is a tradeoff between the length of

advanced notice and policy outcomes: a longer news period leads to higher cumulative gains

to employment but at the expense of larger tax revenue losses – although it should be noted

that the gains for labor and capital are quantitatively small while the losses in U.S. tax

revenue are relatively large. Put differently, if news periods are not taken into account

when analyzing the behavior of firms taking advantage of the tax holiday, policymakers may

overestimate the stimulative effects of the policy and underestimate the costs in terms of tax

revenue losses by multinational firms.

4.5 Access to External Credit Markets

In this section we show that the magnitude of the response in a firm’s production activities,

given by firm-level capital and labor, is highly dependent on the level of access they have to

external credit.

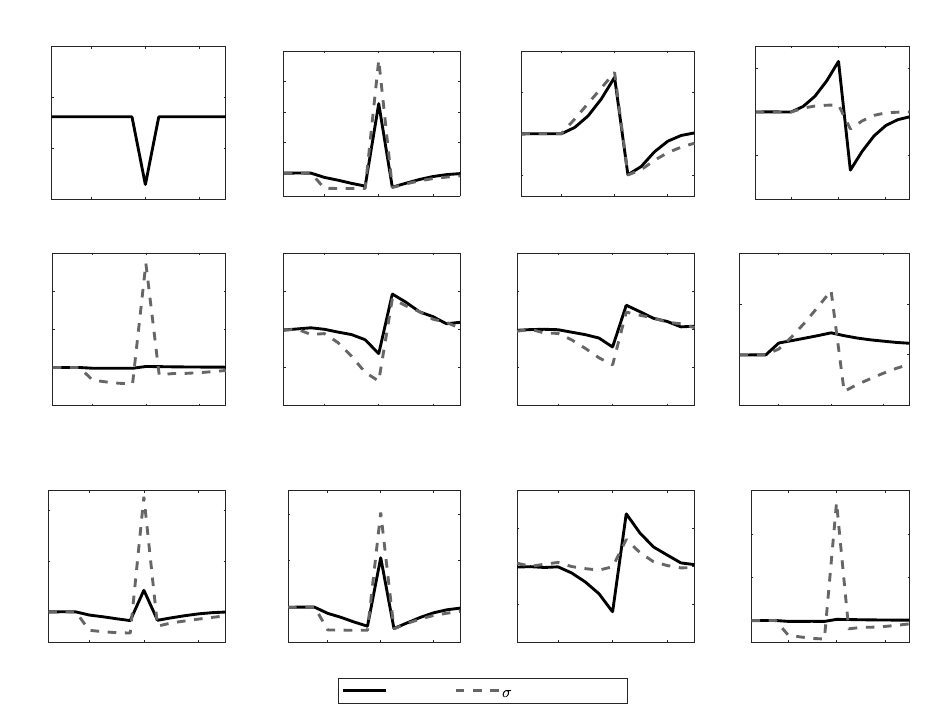

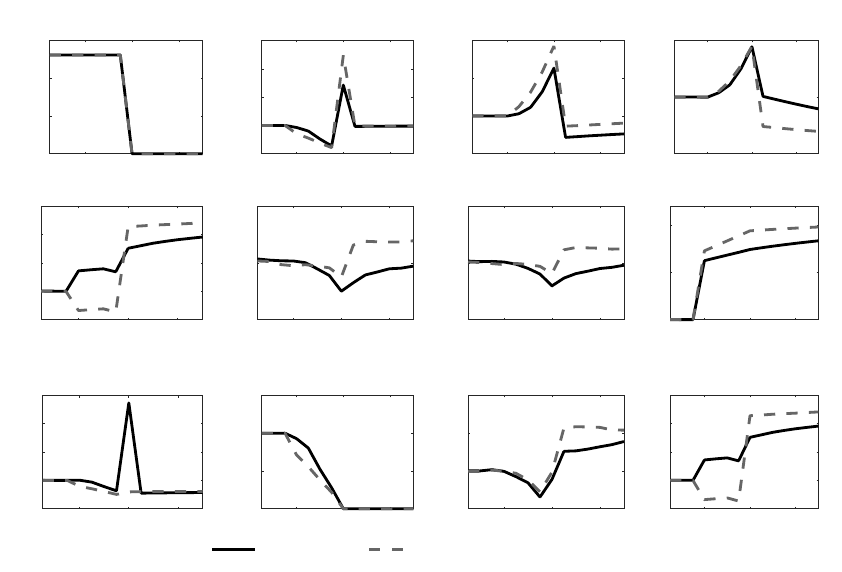

Figure 7 shows the cumulative impacts of a one-period tax holiday under various values of

the parameter governing the ease with which firms can access to credit markets, ψ. Each fig-

ure subdivides the responses into the pre-realization, at-realization, and the post-realization

periods. The cumulative response is the sum of the three sub-periods. Again, the units are

in quarterly gains/losses of that variable relative to the steady state. As in the baseline, the

temporary tax holiday reduces τ from 0.131 to 0.0642.

When the firm cannot access credit markets or the cost of borrowing is high, it relies

heavily on internal funds and thus the marginal value of an additional dollar in tax saving

from the upcoming tax holiday is high. Consequently, during the news period a credit

constrained firm aggressively cuts back transfers in order to take the maximum benefits of

the tax holiday. The curtailing of transfers, in combination with the lack of access to cheap

credit, causes U.S. labor and capital to fall much more during the news period than in the

baseline case. On the other hand, a firm that has access to less costly borrowing also reduces

transfers in order to take advantage of the tax holiday. However, because they can borrow to

25

offset this fall in transfers, there is little net effect on U.S. labor and capital for these firms

during the news period. In comparison, there are large fluctuations in labor and capital for

a credit-constrained firm at and after the tax holiday. These results are easy to understand

within the intuition provided by the policy functions shown in Section 3.2.2. In the presence

of low costs to external credit, firms are able to use debt to keep production close to its

optimal scale when internally held domestic assets (A

US

) fall due to the withholding of

transfers in the news period. Likewise, the scale of production is largely unchanged once the

policy change is implemented and foreign assets flow into the U.S. (A

US

increases).

The labor and capital responses from our baseline model follow the empirical literature of

the AJCA. The majority of the firms receiving tax benefits from the act were not financially

constrained and therefore did not alter the scale of their U.S. operations (Dharmapala, Foley,

and Forbes, 2011; Faulkender and Petersen, 2012). Our baseline results reinforce these

findings. However, Faulkender and Petersen find that a subset of firms that were financially

constrained at the time of the AJCA did increase investment (but not employment) because

of the act. When analyzing the periods at and after the tax holiday, our model likewise

predicts that financially constrained firms increase capital use after the holiday to a larger

degree than financially unconstrained firms.

In general, our analysis shows why the ability of a firm to borrow can be very important

when understanding the effects of future policy changes. For instance, Stokey (2016) shows