22

INTRODUCTION

U

NDER THE U.S. WORLDWIDE TAX SYSTEM, U.S.-

domiciled multinational fi rms pay U.S.

income taxes on foreign earnings when

such earnings are repatriated. Deferral of U.S.

taxation until repatriation creates an incentive for

U.S. multinational fi rms to postpone, temporarily

or permanently, repatriating their foreign earnings

from low-tax countries. This incentive is com-

monly referred to as the “lock-out effect.” We

investigate the lock-out effect in the context of

the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 (the Act).

The Act became law on October 22, 2004, and

there were two primary rationales for its passage.

The first was the repeal of the extraterritorial

income exclusion that had been ruled an illegal

export subsidy by the World Trade Organization.

The second policy rationale for the Act was to

provide a general economic stimulus. The fol-

lowing quotes capture the proponents’ logic for

supporting the Act as a means of stimulating the

U.S. economy:

“Multiple studies show my repatriation provision

could bring $400 billion back into our economy

and create upward of 600,000 jobs in America in

2005,” U.S. Representative Phil English (R-PA), a

member of the House Ways and Means Committee,

who drafted the bill.

“Today more than at any time in our history, we

operate in a global economy. This vote for the Act is

about fi xing our international tax law and providing

much needed tax relief for businesses to help cre-

ate jobs,” U.S. Representative David Wu (D-OR).

“This bill provides tax relief for American busi-

nesses to further fuel economic growth and job

creation,” U.S. Representative Jo Bonner (R-AL).

Most signifi cant among the economic stimulus

provisions of the Act were a deduction for U.S.

domestic production income and a 1-year tax

holiday for repatriations of foreign earnings. This

study evaluates effects of the repatriation tax holi-

day on the lock-out effect of the U.S. worldwide

tax system.

The tax holiday provides an interesting setting

to test the lock-out effect as the Act permits fi rms

to exempt (for one taxable year) 85 percent of the

income that would have otherwise been recognized

on the repatriation of eligible foreign earnings (U.S.

Treasury Department, 2005). The 1-year window

to repatriate under the Act is defi ned either as the

year of the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 or

the year following the Act (e.g., for calendar year

taxpayers, the eligible year is either 2004 or 2005).

There is also a fi nancial reporting consequence

associated with the lock-out effect. For fi nancial

reporting purposes, Accounting Principles Board

Opinion No. 23 (APB 23) provides an opportunity

to avoid booking U.S. taxes on foreign earnings that

are not anticipated to be repatriated. Specifi cally,

if the foreign earnings are reinvested in a foreign

subsidiary indefi nitely, the earnings may be desig-

nated as permanently reinvested offshore (PRE).

Because the PRE classification is a necessary

condition to defer the recognition of U.S. taxes on

foreign earnings for fi nancial reporting purposes,

we use PRE as a proxy for the amount of foreign

earnings subject to the lock-out effect.

To investigate the lock-out effect, we develop

and test three sets of hypotheses around the imple-

mentation of the Act. First, we expect that the

cash holdings and the repatriation tax savings are

positively associated with the fi rms’ level of PRE

in the year prior to the tax holiday. We fi nd that the

level of PRE is positively associated with the tax

savings associated with the deferral of repatriation.

We also expect and fi nd that the cash holdings are

positively associated with the level of PRE prior

to the tax holiday.

Regarding our second set of hypotheses, we

expect and fi nd that the change in PRE is posi-

tively associated with the fi rm-specifi c change in

repatriation tax rate during the holiday. This result

supports the existence of a lock-out effect induced

by the U.S. tax system. We also fi nd that the change

in PRE is positively associated with the change in

THE LOCK-OUT EFFECT OF THE U.S. WORLDWIDE TAX SYSTEM:

AN EVALUATION AROUND THE REPATRIATION TAX HOLIDAY

OF THE AMERICAN JOBS CREATION ACT OF 2004

Roy Clemons, Florida Atlantic University

Michael R. Kinney, Texas A&M University

102

ND

ANNUAL CONFERENCE ON TAXATION

23

cash holdings. This result is consistent with De

Waegenaere and Sansing’s (2008) theoretical pre-

diction that fi rms that have reached their optimal

level of investment in foreign operating assets

accumulate foreign earnings as fi nancial assets until

they can be repatriated at a more advantageous tax

rate (e.g., during a tax holiday).

Regarding our third set of hypotheses, we expect

and fi nd that the change in a fi rm’s PRE following

the holiday period is positively associated with the

change in the fi rm’s repatriation tax rate from the

holiday to the post-holiday period. Firms in our

sample increased PRE in the aggregate by approxi-

mately $88 billion in the year following the tax hol-

iday. This fi nding suggests that the lock-out effect

immediately reappears in the year following the

tax holiday. However, contrary to expectations, the

change in PRE is not associated with the change in

cash holdings in the year following the tax holiday.

One potential explanation for this result is that our

proxy for cash holdings is based on multinational

fi rms’ worldwide cash holdings. Therefore even if

fi rms are increasing their foreign cash holdings in

the year following the Act, the increases may be

offset by decreases in their domestic cash holdings

in the year following the Act. More specifi cally,

spending the repatriated cash may extend into the

year following repatriation.

This study makes several contributions to exist-

ing literature. First, it documents the existence of

a lock-out effect for U.S. multinational fi rms. Sec-

ond, it provides empirical support for De Waegen-

aere and Sansing’s (2008) theoretical model which

predicts that fi rms with mature foreign operations

accumulate foreign earnings offshore in fi nancial

assets until those earnings can be repatriated at

a more advantageous tax rate (e.g., during a tax

holiday). Third, it documents a positive relationship

between the magnitude of the lock-out effect and

the tax cost associated with repatriation.

The fi ndings of this study provide information

useful to academic researchers, regulators, and

policy makers. Academic researchers will fi nd

this study useful in discerning how global fi rms’

cash holdings are associated with their worldwide

taxation. This study links the theoretical predic-

tions of De Waegenaere and Sansing (2008) with

the empirical fi ndings of Foley et al. (2007) to

suggest that fi rms operating in low tax countries

will accumulate their foreign earnings as cash once

they have reached their optimal level of investment

in foreign operating assets. Regulators will also

fi nd this study helpful in assessing the responses

of U.S. multinational fi rms to the U.S. worldwide

tax structure and possible remedies to economic

distortions caused by the lock-out effect.

The next section discusses background research

and motivates our hypotheses. The third section

explains our sample selection and research design.

The fourth section discusses descriptive statistics

and results and the fi fth section concludes.

BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

The Dividend Repatriation Tax Holiday

Internal Revenue Code section 965, part of the

American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, allowed U.S.

multinational fi rms to temporarily repatriate earn-

ings from their foreign subsidiaries at a reduced

effective tax rate. For one taxable year, fi rms could

deduct 85 percent of the repatriations of eligible

foreign earnings -- thereby incurring a maximum

effective tax rate of 5.25 percent (i.e., 15 percent

of 35 percent) on qualifying repatriations (U.S.

Treasury Department, 2005). Firms could elect the

1-year holiday period as the last tax year beginning

before the date of the enactment of AJCA (October

22, 2004) or the fi rst taxable year beginning after

that date. Therefore, all repatriations under the

tax holiday were completed by October 2006.

The following sections discuss the lock-out effect

and the incentives created by the Act in greater

detail.

The U.S. Tax Treatment of Foreign Earnings

and the Lock-Out Effect

Under the U.S. worldwide tax system, U.S.

multinational corporations defer paying U.S. taxes

on the earnings of their foreign subsidiaries until

those earnings are repatriated to the United States.

Upon repatriation, the U.S. parent is allowed a

credit against U.S. taxes for foreign taxes paid on

the repatriated earnings; and, as the foreign tax

rate decreases, the U.S. tax due upon repatriation

increases. Thus, when the subsidiary is located in a

low-tax jurisdiction, the U.S. tax savings associated

with a non-repatriation strategy are substantial. As

long as the foreign earnings of U.S. multination-

als are not repatriated, no U.S. tax is assessed

on such earnings. Firms effectively make their

foreign earnings exempt from U.S. taxes by hold-

ing them offshore permanently. This opportunity

for indefi nite deferral of the incremental U.S. tax

NATIONAL TAX ASSOCIATION PROCEEDINGS

24

assessed on repatriation of foreign earnings creates

the lock-out effect.

Prior Literature and Hypotheses

Prior empirical literature provides evidence that

the U.S. tax system creates a lock-out effect and

suggests that repatriation decisions are very sensi-

tive to the taxes that are due when foreign earnings

are repatriated. Altshuler and Newlon (1993) evalu-

ate tax return data and conclude that a 1 percent

higher repatriation tax burden is associated with

a 1.5 percent reduction in amount repatriated. To

isolate the effect of taxes on repatriation decisions,

Desai et al. (2001), examine both affi liates that

face U.S. repatriation taxes and branches that do

not face U.S. repatriation taxes. Using Bureau of

Economic Analysis data from 1982 to 1997, they

fi nd that when affi liates face a 1 percent increase

in repatriation taxes they decrease dividend repa-

triations by 1 percent, whereas branches do not

exhibit this pattern. Desai et al. (2001) conclude

that repatriation taxes reduce dividend repatriations

by approximately 13 percent noting that “these

effects would disappear if the U.S. were to exempt

foreign income from taxation.” (p. 829)

The statutory U.S. tax rate assessed on repatria-

tion is reduced by the tax rate assessed by foreign

tax authorities in jurisdictions from which the

repatriations originate. Thus, ceteris paribus, the

lower the tax rate in the foreign jurisdictions, the

greater is the net tax rate applied to the repatria-

tions. Logically, the magnitude of the lock-out is

positively associated with the magnitude of the

fi rm-specifi c net tax rate applied to repatriations.

We state our expectations formally in our fi rst

hypothesis expressed in the alternative form:

Hypothesis 1a: The level of foreign earnings

designated as permanently reinvested (PRE) is

positively associated with the net repatriation

tax rate existing prior to the tax holiday for fi rms

repatriating under the Act.

Hartman (1985) argues that the strength of the

lock-out effect is a function of the rates of return

that can be earned on new investment in the United

States versus the foreign country. To develop his

theoretical model, Hartman assumes that the U.S.

taxation of income earned in low-tax foreign

countries is inevitable and that repatriation taxes

will not infl uence the decision of when to repatriate

the earnings. Hartman demonstrates that an after-

foreign-tax dollar in repatriated earnings generates

cash fl ows for the parent fi rm of

(1)

1

1

−

−

t

t

*

,

where t is the U.S. tax rate, and is assumed to be

larger than the foreign tax rate, t*. In deciding

between reinvesting foreign earnings abroad and

repatriating, the fi rm will compare the after-tax

return associated with each option. If a firm

reinvests its foreign earnings for n years, it will

accumulate the following:

(2)

[*

(*

)

]

*

,

*

(

1

1

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

(

*

(

(

*

(

t

t

n

where r* is the pre-tax return in the foreign country

and is taxed by the foreign jurisdiction each period

at t*. Eventually, the funds will be repatriated to the

United States and taxed at the U.S. rate, t.

Alternatively, if the foreign earnings are repatri-

ated immediately, the fi rm will earn:

(3)

[(

)]

*

1

(

1

1

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

t

(

1

(

−

1

(

t

t

n

where r is the pre-tax return in the United States.

Comparing equations (2) and (3) reveals that the

level of U.S. taxation of foreign earnings will not

affect the decision between foreign reinvestment

and repatriation. The U.S. tax costs associated with

repatriations in equation (1) are incurred regardless

of whether one reinvests the earnings abroad or

repatriates them. Hartman’s (1985) model shows

that earnings should be reinvested in the location

that provides the greatest expected after-local-tax

rate of return, irrespective of the taxes owed upon

repatriation to the United States.

Hartman’s (1985) fi ndings hold if foreign earn-

ings are reinvested in operating assets, but Scholes

et al. (2008) suggest that if the foreign income

generated from operating assets is reinvested in

fi nancial assets, then the length of deferral of U.S.

repatriation taxes does matter. Foreign subsidiaries

that have reached their optimal level of investment

in operating assets may indefi nitely defer repatria-

tion to avoid the U.S. tax liability. These fi rms will

likely accumulate excessive amounts of fi nancial

assets, such as cash and marketable securities, in

their foreign subsidiaries.

Consistent with Scholes et al. (2008), Foley et

al. (2007) argue that fi rms’ cash holdings increase

102

ND

ANNUAL CONFERENCE ON TAXATION

25

when their foreign tax rates are less than U.S. tax

rates. The authors’ fi ndings suggest that foreign

subsidiaries in relatively lower tax jurisdictions

hold higher levels of cash than other foreign sub-

sidiaries of the same fi rm.

De Waegenaere and Sansing (2008) suggest that

fi rms owning foreign subsidiaries that have reached

their optimal level of investment in operating assets

and that are operating in low-tax countries are more

likely to designate their foreign earnings as PRE

and hold these earnings in the foreign subsidiary

as fi nancial assets. The following example illus-

trates the argument of De Waegenaere and Sansing

(2008). This example is borrowed from Bryant-

Kutcher et al. (2007). Assume that a foreign sub-

sidiary of a U.S. multinational invests an amount,

K, in foreign operating assets generating pre-tax

cash fl ows (and earnings) according to the func-

tion f(K) = 0.20(K) – 0.001(K

2

), so that increased

investment increases earnings, but at a decreasing

rate. Assume that the fi rm has an after-tax discount

rate equal to 4 percent, that the U.S. corporate tax

rate is 35 percent, and that the after-U.S.-tax risk-

free rate is 3.25 percent, which implies a pretax

risk-free rate of 5 percent. The fi rm faces a foreign

tax rate,

τ

F

, which is less than 35 percent. In this

case the fi rm should continue to reinvest in foreign

operating assets until the optimal investment level,

K*, is reached, where (1 –

τ

F

)f ′(K*) = 4 percent.

That is, the fi rm should keep investing in foreign

operating assets until the marginal after-foreign-

tax return on additional investment is equal to the

fi rm’s discount rate.

Further assume that two fi rms, H and L, are

operating in two foreign countries with differing

tax rates. The tax rate of Country H is 25 percent

and the tax rate of country L is 15 percent. Based

on these foreign tax rates and the fact that f ′(K) =

0.20 – 2(0.001)K, fi rm H will continue to reinvest

in foreign operating assets until K = 73, since (1

– 25%) f ′(73) = 4%, fi rm H’s discount rate. K of

73 will generate a before-tax return each year of

f(73) = 0.20(73) – 0.001(73

2

) = 9.27. Alternatively,

fi rm L will continue to reinvest in foreign operating

assets until K = 76, because (1 – 15%) f ′(76) = 4%,

which is fi rm L’s discount rate. Operating assets of

76 will generate a before-tax return each year of

f(76) = 0.20(76) – 0.001(76

2

) = 9.42.

De Waegenaere and Sansing (2008) study the

optimal repatriation strategy for a fi rm that has

reached investment level K* and will therefore

stop reinvesting future foreign earnings in foreign

operating assets. Firms that have reached K* face

two choices; they can either begin to repatriate all

future earnings as a taxable dividend to the U.S.

parent paying gross U.S. taxes at a 35 percent rate,

or reinvest the after-foreign-tax earnings in foreign

fi nancial assets that earn the risk free rate.

1

De Waegenaere and Sansing (2008) suggest that

the optimal repatriation strategy depends on the

relative size of (1) the after-foreign-tax risk-free

rate, and (2) the fi rm’s discount rate. Let R equal the

risk-free-rate and r equal the fi rm’s discount rate.

The repatriation decision depends on the relation-

ship between r and R(1 –

τ

F

). If the discount rate

is greater than the after-foreign-tax risk free rate,

so that r > R(1 –

τ

F

), the optimal decision is to

repatriate all future earnings as a taxable dividend

to the parent and to incur the 35 percent (gross) U.S.

tax. Using the example of fi rms H and L, assume

that fi rm H, with a foreign tax rate of 25 percent,

generates $20 of pretax foreign earnings, resulting

in $15 of after-tax earnings. Repatriations yield $13

to the U.S. parent after U.S. tax. Since the fi rm has

reached its optimal level of investment in operating

assets, if it retains the $15 abroad, it can reinvest

only at the 3.25 percent after-U.S.-tax risk-free rate.

This investment yields a perpetuity of 0.49 with a

present value of 0.49/0.04 = $12.19, which is less

than $13. Thus, the optimal policy for fi rm H is to

repatriate all future earnings from foreign operating

assets as a taxable dividend to the U.S. parent.

2

Alternatively, if the discount rate is less than

the after-foreign-tax risk-free rate,

3

so that r <

R(1 –

τ

F

), fi rm value is maximized if the foreign

earnings are held abroad in fi nancial assets. This is

the optimal decision despite the fact that the future

earnings from the fi nancial assets will be subject

to tax at the 35 percent U.S. tax rate. Now, assume

that fi rm L, with a foreign tax rate of 15 percent,

generates $20 of pretax foreign earnings, resulting

in $17 of after-tax earnings. Repatriation yields $13

after U.S. tax to the U.S. parent. Retaining the $17

abroad and reinvesting at the 3.25 percent after-

U.S.-tax risk-free rate yields an annual perpetuity

of 0.55 with a present value of 0.55/0.04 = $13.81,

which is more than $13. Therefore, the optimal

policy for fi rm L is to reinvest all future earnings

from foreign operating assets in foreign fi nancial

assets and not repatriate the foreign operating

earnings until a lower tax rate can be obtained for

repatriations.

NATIONAL TAX ASSOCIATION PROCEEDINGS

26

Based on the preceding examples, fi rms will

reinvest foreign earnings in foreign operations

until they reach their optimal level of investment

in foreign operations, K*. All else equal, only after

reaching K* will fi rms begin to accumulate foreign

earnings in fi nancial assets. The lock-out effect is

evidenced by accumulation of foreign earnings in

fi nancial assets. Therefore, as implied by the theo-

retical model from De Waegenaere and Sansing

(2008) and the empirical fi ndings of Foley et al.

(2007), we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1b: The level of foreign earnings

designated as permanently reinvested is positively

associated with the level of cash holdings (fi nancial

assets) prior to the tax holiday for fi rms repatriating

under the provisions of the Act.

Hartman’s (1985) theoretical model assumes

that the tax costs of repatriations are time invariant;

therefore, his model does not consider effects of a

temporary change in the tax costs of repatriations.

In the presence of the tax holiday provided by the

Act, equations (2) and (3) in Hartman’s (1985)

model, presented earlier, will no longer drop out

(Clausing, 2005). Therefore, whether the tax holi-

day was anticipated or not, fi rms experiencing the

lock-out effect of the U.S. worldwide tax system

have an incentive to repatriate more funds during

the tax holiday than they would prior to or after

the tax holiday. Therefore, we hypothesize the

following:

Hypothesis 2a: For the year of repatriation, the

change in foreign earnings designated as PRE is

positively associated with the change in the net

repatriation tax rate.

Given the assumptions of Hartman’s (1985)

theoretical model no lock-out effect exists. But, the

theoretical model of De Waegenaere and Sansing

(2007), presented earlier, demonstrates that once

fi rms reach their optimal level of investment in

foreign operating assets, K*, they may accumu-

late subsequent earnings in financial assets in

their offshore subsidiaries to avoid paying U.S.

repatriation taxes.

De Waegenaere and Sansing (2008) also model

fi rms’ behavior around tax holidays that occur in a

stochastic fashion. The authors argue that because

operating assets are costly to liquidate, all repa-

triations under a tax holiday must be in the form

of fi nancial assets. De Waegenaere and Sansing

(2008) demonstrate that fi rms experiencing the

lock-out effect will accumulate fi nancial assets in

their low-tax foreign subsidiaries to avoid paying

U.S. repatriation taxes. Furthermore, the authors

argue that only fi rms that have accumulated fi nan-

cial assets will have the cash required to repatriate

signifi cant amounts of foreign earnings that have

accumulated abroad due to the lock-out effect.

In summary, only fi rms that have accumulated

fi nancial assets due to the lock-out effect of the

U.S. tax system will have the ability to repatriate

signifi cant amounts of foreign earnings under the

one-time tax holiday. Accordingly, we hypothesize

the following:

Hypothesis 2b: The change in foreign earnings

designated as PRE is positively associated with

the change in cash holdings in the year of the tax

holiday for fi rms repatriating under the Act.

In the year following the tax holiday, we expect

that the lock-out effect will be reestablished as

the net tax rate for repatriations reverts to the rate

prior to the holiday. Also, as argued by Clausing

(2005), granting one tax holiday will cause fi rms

to anticipate future tax holidays and they will no

longer view the normal tax rate as permanent; fi rms

may thus defer repatriations in the hope of future

tax holidays. We expect the strength of the lock-out

effect will be positively associated with the change

in the net tax rate from the holiday to post-holiday

period. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 3a: The change in foreign earnings

designated as permanently reinvested is positively

associated with the change in the net repatriation

tax rate in the year following the tax holiday for

fi rms repatriating under the Act.

De Waegenaere and Sansing (2008) demonstrate

that fi rms repatriating during the tax holiday accu-

mulated fi nancial assets in their low-tax foreign

subsidiaries prior to repatriation. They then sug-

gest that, “because at a tax holiday accumulated

fi nancial assets can be repatriated at the lower

102

ND

ANNUAL CONFERENCE ON TAXATION

27

repatriation tax rate, the expectation of a future tax

holiday may affect the fi rms’ choice to reinvest its

foreign earnings from operating assets in fi nancial

assets or to repatriate them as a dividend.” (p. 11)

Following this logic, subsequent to the repatriation

tax holiday we expect fi rms will have an increased

incentive to defer the repatriation of fi nancial assets

because of their expectations of tax holidays reoc-

curring in the future. Therefore, we hypothesize

the following:

Hypothesis 3b: The change in foreign earnings

designated as permanently reinvested is positively

associated with the change in cash holdings in the

year following the tax holiday for fi rms repatriating

under the Act.

SAMPLE SELECTION AND RESEARCH DESIGN

Sample Selection

We hand collect annual fi nancial statement data

for U.S. multinational fi rms that repatriated under

the tax holiday of the Act. We identifi ed these fi rms

through two primary sources. First, we identifi ed

fi rms that disclosed repatriations under the Act in

their fi nancial statements by searching the EDGAR

database utilizing the following search string [(10Q

or 10K) and (foreign earnings repatriation) w/25

(American Jobs Creation Act of 2004)]. Second,

we identifi ed fi rms that repatriated under the Act

using the Lexis-Nexis Business Wire and News

Wire and Google searches using the key words

“foreign earnings repatriation” and “American Jobs

Creation Act of 2004.” This search identifi ed 378

fi rms that repatriated under the Act.

Fiscal years 2004 through 2006 provide a win-

dow to evaluate repatriation actions during the tax

holiday. For the sample of repatriating fi rms, we

collect permanently reinvested earnings data (PRE)

for fi scal years 2004 through 2006 from income tax

footnotes in annual reports. We exclude observa-

tions not disclosing an amount for PRE for years

t – 1, t, t + 1, where t is the year of repatriation;

this information is needed to compute the pre- to

post-Act change in PRE. As previously noted, the

PRE classifi cation is a necessary condition to defer

the recognition of U.S. taxes on foreign earnings

for fi nancial reporting purposes. The level of PRE

may be considered a proxy for the upper-bound

of the amount of earnings locked out due to the

U.S. tax system. To ensure that we are capturing

fi rms experiencing the lock-out effect, we limit

our sample to fi rms that have PRE greater than or

equal to the amount of earnings repatriated under

the Act.

4

Finally, we delete observations lacking

data suffi cient for models we use for hypothesis

testing.

After imposing all sample screens, there are 213

fi rms that have the required data to test H1a and

H1b in fi scal year 2004, 210 fi rms available to test

H2a and H2b in fi scal year 2005, and 193 fi rms

available to test H3a and H3b for fi scal year 2006.

Research Design – Determinants of PRE

Prior to the One-time Tax Holiday

We test H1a and H1b using the following ordi-

nary least squares regression in Model 1.

PRE

t–1

=

β

0

+

β

1

Repatriation tax rate

t–1

+

β

2

Cash holdings

t–1

+

β

3

Size

t–1

+

β

4

Foreign Income

t–1

+

β

5

U.S. Income

t–1

+

β

6

Capex

t–1

+

β

7

Research & Development

t–1

+

β

8

Book-to-market

t

–

1

+

β

9

Share Repurchases

t

–

1

+

ε

.

PRE equals the level of permanently reinvested

earnings scaled by total assets in the year prior to

repatriation, t – 1. The value of PRE is hand-col-

lected from the fi rms’ fi nancial statement footnotes,

and total assets are obtained from the Compustat

annual database (Data 6).

On the right-hand side, Repatriation tax rate

proxies for the net U.S. tax liability associated

with the earnings classifi ed as PRE. We obtain

footnote disclosures that provide both the U.S.

tax liability recorded during the tax holiday and

the corresponding amount of foreign earnings

repatriated during the tax holiday. During the tax

holiday, fi rms received an 85 percent reduction in

the normal U.S. tax liability for repatriated earn-

ings. Therefore, the U.S. tax rate associated with

the repatriations during the tax holiday equaled the

recognized U.S. tax liability divided by the foreign

earnings repatriated under the Act. For example if

a fi rm recorded a U.S. tax liability of $5.25 associ-

ated with a $100 repatriation, the fi rm’s repatriation

tax rate is 5.25 percent. Also, the tax recorded for

the holiday repatriation allows us to infer the tax

rate for repatriations in non-holiday years. A fi rm

recording a 5.25 percent tax rate for the holiday

repatriation would have incurred a 35 percent tax

NATIONAL TAX ASSOCIATION PROCEEDINGS

28

rate on the repatriation (i.e., 5.25 percent divided by

15 percent) in non-holiday years. H1a predicts that

the level of foreign earnings designated as PRE is

positively associated with the repatriation tax rate

prior to the tax holiday. Thus, we expect a positive

and signifi cant coeffi cient on Repatriation tax rate.

Our expectation stated in H1b is that the magni-

tude of foreign earnings designated as PRE is posi-

tively associated with the level of cash held prior

to the tax holiday. To test whether the magnitude

of PRE is positively associated with cash holdings,

we calculate cash holdings following Foley et al.

(2007). Cash holdings is the natural logarithm of

the ratio of cash to net assets (defi ned as total assets

minus cash). Using Compustat annual data, cash

holdings is calculated as the natural log of (data

item 1/(data item 6 – data item 1)). H1b predicts

the magnitude of foreign earnings designated as

PRE is positively associated with cash holdings

prior to the tax holiday.

Other right-hand side variables are included as

controls. Size is the log of total assets (data item

6) and is included to control for unspecifi ed size

effects. Foreign income is equal to pretax foreign

income scaled by total assets (data item 273/data

item 6) and, U.S. income is equal to U.S. pretax

income scaled by total assets (data item 272/data

item 6). These variables are included to control for

the effects of foreign and domestic profi tability

on PRE. Capex is equal to capital expenditures

scaled by total assets (data item 128/data item 6)

and is included in Model 1 as a proxy for current

growth. Research & Development is equal to

R&D expense scaled by total assets (data item 46/

data item 6) and is included as a control for future

growth. Book-to-market is equal to book value

scaled by market value of equity (data item 60/

(data199*data25)) and is also included in Model 1

to control for a fi rm’s growth opportunities. Finally,

we include Share repurchases, ((data item 115 –

(data item 130 – data item 175))/data item 6), as a

control for the motive to hold cash offshore. More

specifi cally, if as shown in prior research (Blouin

and Krull, 2009; Clemons and Kinney, 2008) fi rms

signifi cantly increase share repurchases in the

year of repatriation, it would suggest that the cash

repatriated under the Act was not needed to fund

domestic growth opportunities and that the cash

was held abroad to avoid the associated U.S. tax

liability on those foreign earnings consistent with

arguments of De Waegenaere and Sansing (2008)

and Desai et al. (2001).

Research Design – Determinants of the Change in

PRE in the Year of the One-time Tax Holiday

To test H2a and H2b we estimate Model 2 using

ordinary least squares:

ΔPRE

t

=

β

0

+

β

1

ΔRepatriation tax rate

t

+

β

2

ΔCash holdings

t

+

β

3

ΔShare Repurchases

t

+

β

4

Size

t

+

β

5

ΔForeign Income

t

+

β

6

ΔU.S. Income

t

+

β

7

ΔCapex

t

+

β

8

ΔResearch & Development

t

+

β

9

Book-to-market

t

+

ε

,

where ΔPRE equals the change in permanently

reinvested earnings from the year prior to the

tax holiday (t – 1) to the year of the tax holiday

(t) scaled by total assets. The values of PRE are

hand-collected from the fi rms’ fi nancial statement

footnotes, and total assets are obtained from the

Compustat annual database (Data 6).

We investigate whether ΔPRE is associated with

ΔRepatriation tax rate, which is a proxy for the

reduction in the net U.S. tax liability during the

tax holiday. Based on fi nancial statement footnote

disclosures, we obtain both the U.S. tax liability rec-

ognized under the tax holiday and the corresponding

amount of foreign earnings repatriated under the tax

holiday. The U.S. tax liability recognized by fi rms

repatriating under the tax holiday is 15 percent (i.e.,

an 85 percent reduction under the Act) of the U.S.

tax liability that would have been recorded by the

fi rms absent the tax holiday. Because the tax holi-

day liability is 15 percent of the non-holiday tax

liability, our proxy for the non-holiday tax liability

is the recognized holiday tax liability divided by

15 percent. ΔRepatriation tax rate is the difference

between the holiday and non-holiday net tax rates

and represents the tax savings on repatriations

during the tax holiday. H2a predicts that ΔPRE is

positively associated with ΔRepatriation tax rate

in the year of the tax holiday for repatriating fi rms.

Therefore, we expect a positive and signifi cant

coeffi cient for ΔRepatriation tax rate.

We also investigate whether ΔPRE is associated

with ΔCash holdings in the year of the tax holiday.

ΔCash holdings is the change in cash balance from

the year prior to the tax holiday (t – 1) to the year

of the tax holiday (t) scaled by total assets. H2b pre-

dicts that ΔPRE is positively associated with ΔCash.

Thus, we expect a positive coeffi cient for ΔCash

holdings. Finally, we expect that ΔPRE is negatively

associated with ΔShare Repurchases. Finding such

102

ND

ANNUAL CONFERENCE ON TAXATION

29

a result would further support De Waegenaere and

Sansing’s (2008) prediction that fi rms accumulate

cash in their foreign subsidiaries because they do

not have domestic investment opportunities that

provide a return superior to the foreign risk free rate.

We also include control variables in Model 2.

Size controls for unspecifi ed size effects. ΔForeign

Income and ΔU.S. Income control for the effects

of changes in foreign and domestic profi tability.

ΔCapex, ΔResearch & Development, and Book-to-

market are included in Model 2 to control for fi rms’

current and future growth opportunities.

Research Design – Determinants of the

Change in PRE in the Year Following the

One-time Tax Holiday

We test H3a and H3b by estimating Model 3

using ordinary least squares regression in the year

following the tax holiday:

ΔPRE

t+1

=

β

0

+

β

1

ΔRepatriation tax rate

t+1

+

β

2

ΔCash holdings

t+1

+

β

3

ΔShare Repurchases

t+1

+

β

4

Size

t+1

+ Β

5

ΔForeign Income

t+1

+

β

6

ΔU.S.Income

t+1

+

β

7

ΔCapex

t+1

+

β

8

ΔResearch & Development

t+1

+

β

9

Book-to-market

t+1

+

ε

.

ΔPRE is the change in permanently reinvested

earnings from the year of the tax holiday (t) to the

year following the tax holiday (t + 1) scaled by total

assets. We investigate whether ΔPRE is associated

with the return to normal repatriation tax rates in

the year following the tax holiday. We calculate

ΔRepatriation tax rate from the year of the tax

holiday (t) to the year following the tax holiday

(t + 1). H3a predicts that ΔPRE is positively

associated with ΔRepatriation tax rate in the year

following the tax holiday for fi rms repatriating

under the Act.

We also investigate whether ΔPRE is associated

with ΔCash holdings in the year following the

tax holiday. We calculate ΔCash holdings as the

change in cash from the year of the tax holiday

(t) to the year following the tax holiday (t + 1)

scaled by total assets. H3b predicts that ΔPRE is

positively associated with ΔCash holdings in the

year following the tax holiday. Thus, we expect a

positive coeffi cient on ΔCash holdings. In addition

to the variables of interest, Model 3 includes the

same control variables as Model 2 to control for

size effects, and growth factors.

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS AND RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

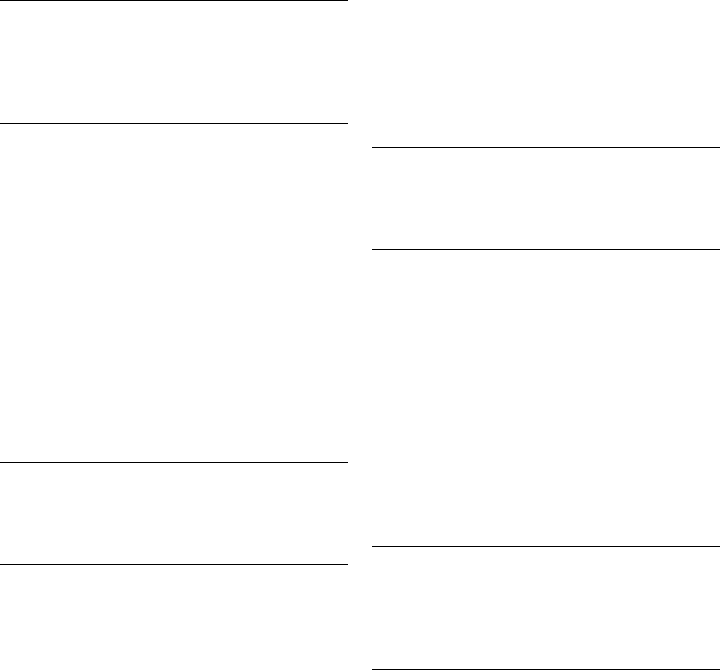

Table 1 summarizes the industry composition

of the repatriating fi rms in our sample. Firms in

manufacturing industries represent 73 percent of

the sample. Service companies comprise the second

largest group of repatriating fi rms (8 percent of the

sample), and retail companies and fi nancial service

companies are the next largest groups of repatriat-

ing fi rms (representing 5 percent and 6 percent of

the sample respectively).

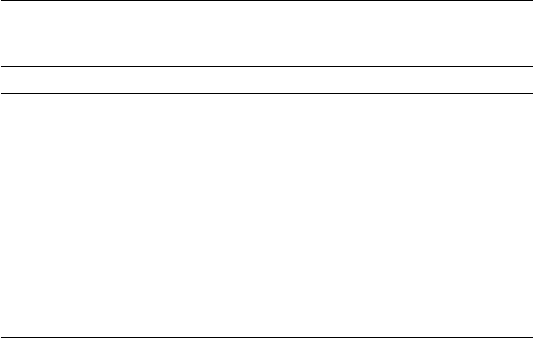

Table 2 presents descriptive data for those repa-

triating fi rms having suffi cient data available to

Table 1

Industry Distribution of Firms Repatriating under

the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004

SIC Code # of Firms:

1000-1999 Mining and Construction 5

2000-2999 Manufacturing 54

3000-3999 Manufacturing 101

4000-4999 Transportation, Communication, Electric, Gas 6

5000-5999 Wholesale, Retail 12

6000-6999 Financial, Insurance, Real Estate 13

7000-7999 Hotel, Services 18

8000-8999 Services 4

9000-9999 Public Administration 1

NATIONAL TAX ASSOCIATION PROCEEDINGS

30

calculate each specifi c metric.

5

We do not winsorize

or otherwise transform the raw data reported in

Table 2; hence, some means are heavily infl uenced

by outliers. We provide medians, minimum, and

maximum values as well as the standard error for

each variable for the data items so that the infl uence

of outliers can be inferred.

The per-fi rm average amount repatriated under

the Act was approximately $1 billion, and the aver-

age repatriation equaled 9 percent of total assets.

The median repatriation amount was $152 million

and equaled 6 percent of total assets. The sample

fi rms are large and have substantial foreign opera-

tions. Average total assets were $31.5 billion, and,

on average, foreign income amounted to 5 percent

of the fi rm’s total assets.

The data in Table 2 show sample fi rms had a

mean U.S. effective tax rate of 33 percent and a

mean foreign tax rate for repatriated earnings of 7

percent. Absent the tax holiday, fi rms would have

recognized an average U.S. tax liability of approxi-

mately $264 million on the repatriated earnings

(i.e., (.33 - .07)*1,014), but under the tax holiday

the liability was only $40 million, representing an

average U.S. tax savings of $224 million per fi rm.

On average, research and development expense

represented 4 percent of total assets, and the aver-

age book-to-market ratio was .41. Consistent with

prior research (De Waegenaere and Sansing 2008;

Foley et al. 2007), the data in Table 2 suggest that

fi rms were investing some foreign earnings in cash.

On average, fi rms were holding cash equal to 28

percent of net assets compared to cash holdings

of 10 percent of net assets for all other Compustat

fi rms — which is consistent with a lock-out effect.

The mean and median ratio of cash to PRE was

2.88 and 0.81 suggesting cash constituted a large

percentage of PRE.

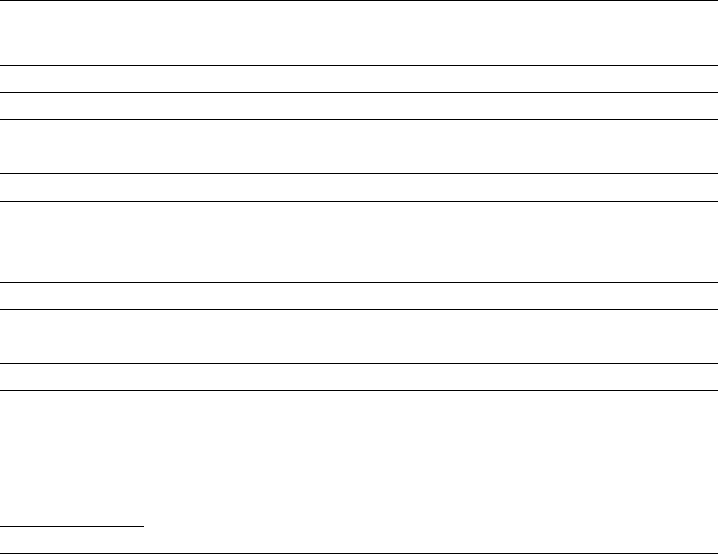

Results – Determinants of PRE

Prior to the Tax Holiday

Table 3 presents the results from estimating

Model 1 which is intended to identify determi-

nants of PRE in the year prior to the tax holiday.

Consistent with H1a, we fi nd a positive and sig-

nifi cant association between the level of PRE and

Repatriation tax rate (p-value < 0.00, one-tailed

test). This result suggests that, as a fi rm’s U.S. tax

Table 2

2004 Descriptive Statistics

Firms Repatriating under the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004

Variable Mean Std. Dev. Min. Median Max.

Repatriations

Repatriations 1,014 3,210 1 152 37,000

Repatriations/total assets 0.09 0.09 0.00 0.06 0.50

Permanently reinvested earnings (PRE)

PRE 1,802 4,675 4 367 51,600

PRE/total assets 0.17 0.14 0.00 0.13 0.67

Cash/PRE 2.88 10.19 0.01 0.81 120.60

Tax attributes

Effective tax rate (ETR) 0.33 0.78 -1.92 0.30 10.50

Foreign tax rate (FTR) 0.07 0.09 0.00 0.03 0.35

Firm characteristics

Size (total assets) 31,512 145,929 78 3,066 1,484,101

Foreign income/total assets 0.05 0.04 -0.05 0.04 0.17

Research and Development/total assets 0.04 0.04 0.00 0.02 0.19

Book-to-market ratio 0.41 0.21 0.01 0.37 1.11

Cash holdings (cash/net assets) 0.28 0.46 0.00 0.13 2.85

($ amounts in millions)

102

ND

ANNUAL CONFERENCE ON TAXATION

31

Table 3

Determinants of the Level of PRE in the Year Prior to the Tax Holiday Estimated Using OLS

Variables Predicted Sign Coeffi cient t-statistic p-value

Intercept ? 0.173*** 3.28 0.00

Size ? -0.010*** -2.41 0.02

Foreign Income ? 1.766*** 7.87 0.00

U.S. Income ? -0.342*** -2.03 0.04

Capex ? 0.099 0.38 0.70

Research & Development ? 0.061 0.28 0.78

Book-to-market ? 0.040 0.90 0.37

Cash Holdings + 0.025*** 7.31 0.00

Repatriation tax rate + 0.200*** 6.49 0.00

Repurchases ? 0.103 0.71 0.48

Adjusted R-square = 40%

*** indicates signifi cance at the 5 percent level or better for a one-tailed test when a prediction is made and a

two-tailed test when no prediction is made.

Model 1: PRE

t–1

=

β

1

Size

t–1

+

β

2

Foreign Income

t–1

+

β

3

U.S. Income

t–1

+

β

4

Capex

t–1

+

β

5

Research &

Development

t–1

+

β

6

Book-to-market

t–1

+

β

7

Cash holdings

t–1

+

β

8

Repatriation tax rate

t–1

+

β

9

Share Repurchases

t–1

+

ε

Variable defi nitions:

PRE = Permanently reinvested earnings scaled by total assets

Size = Log of total assets

Foreign Income = Foreign pretax income scaled by total assets

U.S. Income = U.S. pretax income scaled by total assets

Capex = Capital expenditures scaled by total assets

Research & Development = R&D expense scaled by total assets

Book-to-market = Book value scaled by market value of equity

Cash holdings =

Log of cash scaled by net assets, where net assets = total assets – cash

Repatriation tax rate = Tax rate related to repatriation of foreign earnings

Share Repurchases = Share repurchase scaled by total assets.

NATIONAL TAX ASSOCIATION PROCEEDINGS

32

liability due upon repatriation of foreign earnings

increases, so does the amount of foreign earnings

classifi ed as permanently reinvested offshore. This

result supports H1a and the existence of a lock-out

effect induced by the U.S. tax system.

Consistent with H1b, we fi nd a positive and

signifi cant association in Table 3 between the pre-

holiday level of PRE and Cash holdings (p-value

< 0.00, one-tailed test). This result provides addi-

tional evidence that fi rms were experiencing the

lock-out effect prior to the tax holiday as some

earnings were held offshore in cash rather than

operating assets, consistent with the predictions

of De Waegenaere and Sansing (2008).

Not surprisingly, we also find that Foreign

Income is signifi cantly and positively associated

with PRE (p-value < 0.00, two-tailed test), and U.S.

Income is signifi cantly and negatively associated

with PRE (p-value < 0.04, two-tailed test). These

results indicate that fi rms generating relatively

higher levels of foreign income have a greater

capacity to accumulate earnings offshore.

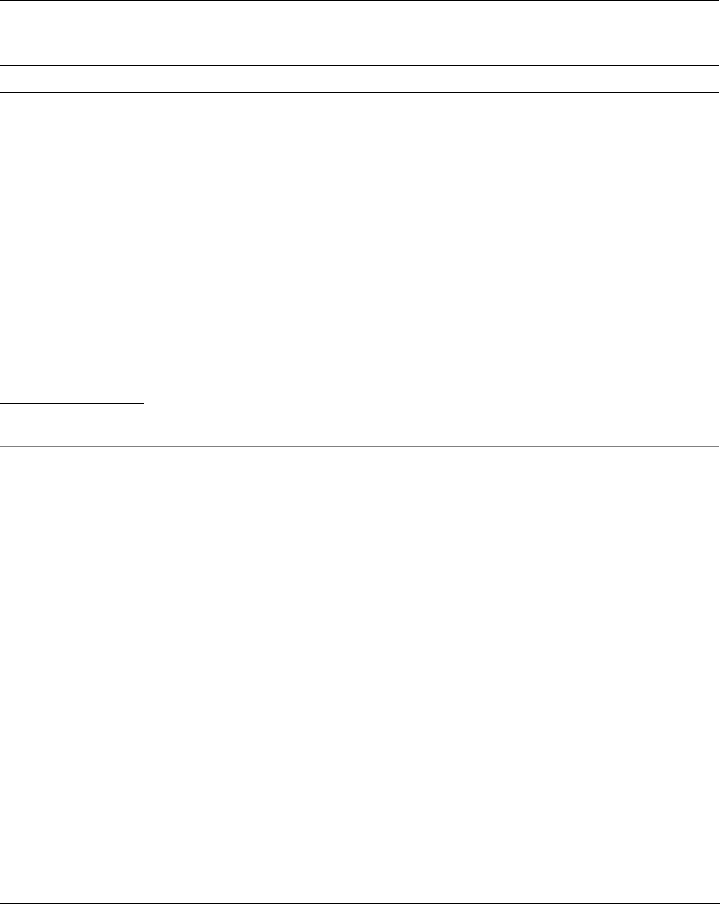

Results – Determinants of the Change in PRE

in the Year of the Tax Holiday

Table 4 presents the results from estimating

Model 2, in which we identify determinants of

the ΔPRE in the year of repatriation. Consistent

with H2a, we fi nd a positive and signifi cant asso-

ciation between ΔPRE and ΔRepatriation tax rate

(p-value < 0.00, one-tailed test). This result is

consistent with a pre-Act lock-out effect, and the

Act reducing the lock-out incentive. The evidence

in Table 4 strongly suggests that, all else equal,

fi rms experiencing the lock-out effect repatriated

their earnings when the lock-out incentive was

signifi cantly reduced.

Consistent with H2b, we fi nd a positive and

signifi cant association between ΔPRE and ΔCash

holdings in the year of repatriation (p-value < 0.02,

one-tailed test). Consistent with the predictions of

De Waegenaere and Sansing (2008), this fi nding

suggests that fi rms released the excess cash from

their foreign subsidiaries during the tax holiday.

Together, these fi ndings support H2a and H2b

and suggest that fi rms repatriating under the Act

previously accumulated foreign earnings as cash

offshore to avoid paying U.S. income tax that

would be due upon repatriation of the earnings

(i.e., the lock-out effect). Also, we fi nd that the

ΔPRE is negatively associated with the ΔShare

Repurchases (p-value < 0.01, one-tailed test) in

the year of repatriation during the tax holiday.

Consistent with the predictions of De Waegenaere

and Sansing (2008), this result suggests that fi rms

deferred repatriation prior to the tax holiday due

to the lock-out effect; however, the use of the

repatriated cash also suggests a lack of investment

opportunities in the United States.

Results – Determinants of the Change in PRE

in the Year Following the Tax Holiday

Table 5 presents the results from estimating

Model 3 to identify the determinants of ΔPRE in

the year following the holiday. Consistent with

H3a, we fi nd a positive and signifi cant association

between ΔPRE and ΔRepatriation tax rate (p-value

< 0.02, one-tailed test). Consistent with the predic-

tions of prior research (Clausing, 2005; Gravelle,

2005; De Waegenaere and Sansing, 2008) this

result suggests the tax holiday encouraged fi rms to

subsequently revert to retaining foreign earnings

abroad (i.e., behaving consistent with the lock-out

effect). Post-Act, not only do these fi rms avoid

current U.S. tax by not repatriating, but the fi rms

also have an added incentive (i.e., they now attach

a higher probability to additional tax holidays in

the future) to wait for a more favorable repatria-

tion tax rate.

Contrary to H3b, the coefficient on ΔCash

holdings in the year following repatriation is not

signifi cantly different from zero (p-value 0.24, one-

tailed test). However, our proxy for cash holdings

is based on multinational fi rms’ worldwide cash

holdings. Therefore even if foreign cash holdings

increase as expected, such increases may have

been offset by domestic cash holding decreases

in the year following repatriation. For example,

fi rms may still be spending the cash in year t + 1

repatriated under the Act in year t.

With respect to our other control variables, we

fi nd that ΔForeign Income is signifi cantly and

positively associated with ΔPRE (p-value < 0.00,

two-tailed test). This result indicates that fi rms

generating higher levels of foreign income have a

greater capacity to accumulate earnings offshore.

We also fi nd, consistent with the lock-out effect,

that a fi rm’s Book-to-market ratio is negatively

associated with the ΔPRE in the year following

the Act.

102

ND

ANNUAL CONFERENCE ON TAXATION

33

Table 4

Ols Regression of 2004 to 2005 Changes in Permanently Reinvested Earnings (PRE) for Firms

Repatriating under the Tax Holiday on Changes in the Motives for PRE

Variables Predicted Sign Coeffi cient t-statistic p-value

Intercept ? -0.095*** -3.04 0.00

Size ? 0.005 1.48 0.14

Book-to-market ratio ? 0.047 1.87 0.06

Change in Foreign Income ? 0.393 1.32 0.19

Change in U.S. Income ? 0.281 1.46 0.15

Change in Capex ? 0.596 1.58 0.12

Change in Research & Development ? 1.044*** 2.58 0.01

Change in Cash Holdings + 0.017*** 4.13 0.02

Change in Repatriation tax rate + 0.206*** 7.40 0.00

Change in Share Repurchases - -0.110*** -2.36 0.01

Adjusted R-square = 25%

*** indicates signifi cance at the 5 percent level or better for a one-tailed test when a prediction is made and a

two-tailed test when no prediction is made.

Model 2: ΔPRE

t

=

β

1 Size

t

+

β

2 ΔForeign Income

t

+

β

3 ΔU.S. Income

t

+

β

4 ΔCapex

t

+

β

5 ΔResearch & Development

t

+

β

6 Book-to-market

t

+

β

7 ΔCash holdings

t

+

β

8 ΔRepatriation tax rate

t

+

β

9 ΔShare Repurchases

t

+

ε

Variable defi nitions:

ΔPRE = Change in permanently reinvested earnings scaled by total assets (2005-2004)

Size = Log of total assets

ΔForeign Income = Change in foreign pretax income scaled by total assets (2005-2004)

ΔU.S.Income = Change in U.S. pretax income scaled by total assets (2005-2004)

ΔCapex = Change in Capital expenditures scaled by total assets (2005-2004)

ΔResearch & Dev. = Change in R&D expense scaled by total assets (2005-2004)

Book-to-market = Book value scaled by market value of equity

ΔCash holdings = Change in log of cash scaled by net assets (2005-2004)

ΔRepatriation tax rate = Change in tax rate related to repatriation of foreign earnings (2005-2004)

ΔShare Repurchases = Change in share repurchase scaled by total assets (2005-2004)

NATIONAL TAX ASSOCIATION PROCEEDINGS

34

Table 5

OLS Regression of 2005 to 2006 Changes in Permanently Reinvested Earnings (PRE) for Firms

Repatriating under the Tax Holiday on Changes in the Motives for PRE

Variables Predicted Sign Coeffi cient t-statistic p-value

Intercept ? 0.044*** 2.71 0.01

Size ? -0.002 -1.29 0.20

Book-to-market ratio ? -0.017*** -2.18 0.03

Change in Foreign Income ? 0.448*** 3.43 0.00

Change in U.S. Income ? 0.036 0.50 0.62

Change in Capex ? 0.227 1.38 0.17

Change in Research & Development ? 0.478*** 2.33 0.02

Change in Cash Holdings + 0.003 1.41 0.24

Change in Repatriation tax rate + 0.049*** 4.00 0.02

Change in Share Repurchases ? -0.033 -0.92 0.36

Adjusted R-square = 16%

*** indicates signifi cance at the 5 percent level or better for a one-tailed test when a prediction is made and a

two-tailed test when no prediction is made.

Model 3: ΔPRE

t+1

=

β

1 Size

t+1

+

β

2 ΔForeign Income

t+1

+

β

3 ΔU.S. Income

t+1

+

β

4 ΔCapex

t+1

+

β

5 ΔResearch & Development

t+1

+

β

6 Book-to-market

t+1

+

β

7 ΔCash holdings

t+1

+

β

8 ΔRepatriation tax rate

t+1

+

β

9 ΔShare Repurchases

t+1

+

ε

Variable defi nitions:

ΔPRE = Change in permanently reinvested earnings scaled by total assets (2006-2005)

Size = Log of total assets

ΔForeign Income = Change in foreign pretax income scaled by total assets (2006-2005)

ΔU.S.Income = Change in U.S. pretax income scaled by total assets (2006-2005)

ΔCapex = Change in Capital expenditures scaled by total assets (2006-2005)

ΔResearch & Dev. = Change in R&D expense scaled by total assets (2006-2005)

Book-to-market = Book value scaled by market value of equity

ΔCash holdings = Change in log of cash scaled by net assets (2006-2005)

ΔRepatriation tax rate = Change in tax rate related to repatriation of foreign earnings (2006-2005)

ΔShare Repurchases = Change in share repurchase scaled by total assets (2006-2005).

102

ND

ANNUAL CONFERENCE ON TAXATION

35

CONCLUSION

In this study, we evaluate the lock-out effect

of the U.S. tax system by examining fi rms that

repatriated under the 1-year tax holiday for repa-

triations provided by the American Jobs Creation

Act of 2004.

Hand-collecting fi nancial statement data for

a sample of fi rms repatriating under the Act, we

fi nd that repatriating fi rms behaved in a manner

consistent with a lock-out effect. Based on the

expectations from De Waegenaere and Sansing’s

(2008) theoretical model, we predict and fi nd that

fi rms change their lock-out behavior around the

tax holiday. To our knowledge this study is the

fi rst to evaluate the lock-out effect of the U.S.

worldwide tax system around a dramatic and

temporary change in the U.S. tax rate associated

with foreign earnings repatriations. Because theory

predicts that the U.S. worldwide tax system causes

a lock-out effect for foreign earnings, we predict

fi rms retained foreign earnings offshore and accu-

mulated some of those earnings as cash prior to the

tax holiday. Likewise, we also predicted that during

the tax holiday fi rms would repatriate that cash to

the United States. Furthermore, we expected that

in the year following the tax holiday fi rms would

revert to the lock-out behavior.

As predicted, we fi nd that fi rms repatriating

under the Act accumulated foreign earnings and

held some of those earnings as cash prior to the tax

holiday. This evidence is consistent with De Wae-

genaere and Sansing’s (2008) theoretical model

which predicts that fi rms repatriating under the tax

holiday accumulated foreign earnings abroad as

cash as a result of the lock-out effect. These results

are also consistent with a tax executive survey

study by Graham et al. (2008). Firms responding

to this survey indicated 75 percent of the funds

repatriated during the holiday were derived from

cash or other liquid fi nancial assets.

Also, consistent with lock-out behavior, we fi nd

that the changes in the fi rms’ U.S. repatriation tax

rates and cash holdings during the holiday are

positively associated with the change in the level

of PRE in the year of the tax holiday. Furthermore,

consistent with prior research (Blouin and Krull,

2009; Clemons and Kinney, 2008), we fi nd that

fi rms repatriating under the tax holiday signifi -

cantly increased their share repurchases. This result

is consistent with De Waegenaere and Sansing’s

(2008) prediction that fi rms accumulating cash due

to the lock-out effect lacked domestic investment

opportunities. Finally, consistent with expectations

we fi nd that the change in the U.S. repatriation tax

rates were positively associated with the change

in permanently reinvested earnings in the year

following the tax holiday, suggesting that fi rms

immediately reverted to deferring the repatriation

of their foreign earnings following the holiday.

Contrary to expectations, we fi nd no signifi cant

association between the change in permanently

reinvested foreign earnings and the change in cash

holdings in the period following the tax holiday.

This study makes several contributions to

existing literature. First, it documents the exis-

tence of a lock-out effect for U.S. multinational

fi rms. Second, it provides empirical support for

De Waegenaere and Sansing’s (2008) theoretical

model that predicts which fi rms will accumulate

foreign earnings in offshore cash before and after

the tax holiday due to the lock-out effect. Third,

it documents a positive relationship between the

magnitude of the lock-out effect and the tax cost

associated with repatriation.

Notes

1

Once the foreign subsidiary’s Subpart F income has

been subject to U.S. tax, the income may be repatriated

to the U.S. parent without triggering any additional

U.S. tax.

2

Note that this applies only to operating earnings gener-

ated after the optimal investment level, K*, has been

reached. Prior to that time all operating earnings are

reinvested in additional foreign operating assets.

3

Although the 4 percent discount rate in the example is

always greater than the after-U.S.-tax risk-free rate of

3.25 percent, the repatriation decision depends on the

after-foreign-tax risk-free rate, which, depending on the

foreign tax rate, can be higher than the discount rate.

4

Deleting fi rms with no permanently reinvested earn-

ings reduced our sample size to 307 fi rms, deleting

fi rms reporting repatriations exceeding permanently

reinvested earnings reduced the sample to 222 fi rms.

5

All variables except Repatriations are measured in the

year prior to the tax holiday. Repatriations are taken

from the year of the tax holiday.

REFERENCES

Altshuler, Rosanne and Scott T. Newlon. The Effects of

U.S. Tax Policy on the Income Repatriation Patterns of

U.S. Multinational Corporations. In Alberto Giovan-

nini, R. Glenn Hubbard, and Joel Slemrod, eds. Studies

of International Taxation. Cambridge, MA: National

Bureau of Economic Research, 1993, pp. 77-115.

NATIONAL TAX ASSOCIATION PROCEEDINGS

36

Blouin, Jennifer L. and Linda K. Krull. Bringing It Home:

A Study of the Incentives Surrounding the Repatria-

tion of Foreign Earnings Under the American Jobs

Creation Act of 2004. Journal of Accounting Research

47 (September 2009): 1027-1059.

Bryant-Kutcher Lisa, David A. Guenther, and Lisa

Hersrud. Taxes and Investment Opportunities:

Valuing Permanently Reinvested Foreign Earnings.

Eugene, OR: University of Oregon, 2007. Working

Paper.

Clausing, Kimberly A. Tax Holidays (and Other Escapes)

in the American Jobs Creation Act. National Tax

Journal 58 (September, 2005): 331.

Clemons, Roy and Michael Kinney. An Analysis of the

Tax Holiday for Repatriation Under the Jobs Act. Tax

Notes 120 (August, 2008): 759-768.

De Waegenaere, Anja M. and Richard C. Sansing. Taxa-

tion of International Investment and Accounting Valu-

ation, Contemporary Accounting Research 25 (Winter

2008): 1045-1066.

Desai, Mihir A., C. Fritz Foley, and James R. Hines Jr.

Repatriation Taxes and Dividend Distortions. Na-

tional Tax Journal 54 (December, 2001): 829-851.

Foley, C. Fritz, Jay C. Hartzell, Sheridan Titman, and

Garry Twite. Why Do Firms Hold So Much Cash?

A Tax-based eEplanation. Journal of Financial Eco-

nomics 86 (December 2007): 579-607.

Graham, John R., Michelle Hanlon, and Terry J. Shevlin.

Barriers to Mobility: The Lockout Effect of U.S.

Taxation of Worldwide Corporate Profi ts. Durham,

NC: Duke University, 2008. Working Paper.

Gravelle, Jane G. The 2004 Corporate Tax Revisions as

a Spaghetti Western: Good, Bad, and Ugly. National

Tax Journal 58 (September 2005): 347-365.

Hartman, David G. Tax Policy and Foreign Direct Invest-

ment. Journal of Public Economics 26 (February

985): 107-122.

Scholes, Myron S., Mark A. Wolfson, Merle M. Erickson,

Edward L. Maydew, and Terry J. Shevlin. Taxes and

Business Strategy: A Planning Approach (4

th

ed.).

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2008.

U.S. Department of Treasury. Treasury and IRS Announce

Guidance on Repatriation of Foreign Earnings under

the American Jobs Creation Act. Notice 2005-38,

2005-6 IRB 1 Washington, D.C., 2005.