Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business Volume 11

Contextual factors, obedience pressure, Page 1

Contextual factors, obedience pressure and accounting decision-

making

Alireza Daneshfar

University of New Haven

Shabnam Hashemiyeh Fahadani

Fairfield University

ABSTRACT

This paper discusses the factors that affect accountants’ (and auditors’) susceptibility to

obedience pressure in the workplace. Succumbing to superior obedience pressure impacts an

accountant’s ability to maintain their independence when exercising their professional judgment.

The presence of such pressure could lead to dysfunctional behavior. However, accountants’

reactions to obedience pressure vary according to several factors. The current literature has

investigated the individual-related factors effect such as personality, commitment, and gender.

Referring to transactional process theory, this paper discusses the effects of contractual factors in

addition to the effects of individual-related factors. The contractual factors can assume several

forms including the magnitude of the amount of the issue, the sensitivity of the issue, explicit

conflict with laws and regulations and professional standards, and possibility of disclosure. The

model discussed in this paper has an application for future studies to include the effects of

contractual factors in studies of obedience pressure on accountants and auditors. Application of

the model by practitioners is also discussed to better understand how accountants’ and auditors’

reactions to obedience pressure are formed. Such understanding could be beneficial to minimize

the cost of accountants’ and auditors’ dysfunctional behavior that could arise from obedience

pressure.

Keywords: obedience pressure, contextual factors, accounting decision-making, accountants,

auditors.

Copyright statement: Authors retain the copyright to the manuscripts published in AABRI

journals. Please see the AABRI Copyright Policy at http://www.aabri.com/copyright.html

Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business Volume 11

Contextual factors, obedience pressure, Page 2

INTRODUCTION

Accountants’ (and auditors’) independence to employ their professional judgment is

crucial as their expertise. Obedience pressure comes into play when accountants are under

pressure from their superiors to adversely alter their professional judgment, which could lead to

dysfunctional performance and negative outcomes. Behavioral accounting studies have widely

reported evidence of obedience pressure on accountants in the workplace, skewing their

professional judgment. Davis, DeZoort, and Kopp (2006) found that management accountants

are more probable to engage in the budgetary slack formation when obedience pressure from an

direct superior exists. These findings were consistent with findings in social psychology research

(Buchheit, Pasewark, & Straser, 2003; McNair, 1991), auditing research (e.g., Hartanto &

Kusuma, 2002; Nugrahanti & Jahjam, 2018; Putri & Laksito, 2013), and management accounting

research (Brink, Gouldman, & Victoravich, 2018; Hartmann & Maas, 2010).

However, the results of the studies that found that obedience pressure on accountants

adversely alters their professional judgment showed that the accountants’ susceptibility to

obedience pressure varies. For example, Davis et al. (2006) found that 69.35% of research

participants felt a considerable amount of pressure from their superiors and the mean of those

who indicated that it would be difficult to make a decision when there is a pressure from the

superior was 57.23. Social psychology literature also offers support for subordinates’ resistance

to obedience pressure (Brehm & Brehm, 1981).

The variability of susceptibility to obedience pressure raises the question of what factors

affect such variability. Understanding those factors would be beneficial to elevate the quality of

accountants’ professional judgment and lower the dysfunctional behavior that could be caused by

obedience pressure. To find the answer, accounting researchers have investigated the effects of

several factors that stimulus accountants’ reactions to obedience pressure such as responsibility

shifting (Davis et al., 2006), Machiavellianism (Hartmann & Maas, 2010), and gender (Collins,

1993). However, the investigated factors are factors related to accountants’ individual

characteristics. Prior studies have not presented any evidence pertaining to the factors related to

the subject matter that could influence accountants’ reactions to obedience pressure—the

contextual factors. Referring to transactional process theory (Lazarus, 1995), this paper argues

that contextual factors can influence accountants’ reactions to obedience pressure and that these

factors may interact with individual-related factors. Understanding the effect of contractual

factors could be beneficial in understanding variability in accountants’ susceptibility to

obedience pressure.

The current study’s contribution to the literature includes extending its scope to include

the factors that could explain the variability in accountants’ susceptibility to obedience pressure.

Particularly, this paper expands on the discussions offered in Davis et al. (2006) and Hartmann

and Maas (2010) that investigated the effects of individual-related factors on accountants’

reactions to obedience pressure. The second contribution of this paper is that it builds upon the

theoretical model of the pressure effect on accounting professional judgment and improves the

model by including the underlying contractual factors. This improved model will help future

researchers to consider the effects of contractual factors in their studies of obedience pressure.

The third contribution of this paper is its explanation of the inconsistencies present in prior

studies in terms of accountants’ reactions to obedience pressure. Finally, this paper has useful

practical implications for accounting and auditing managers who would like to improve their

Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business Volume 11

Contextual factors, obedience pressure, Page 3

accountants’ and auditors’ performances and mitigate the dysfunctional behavior and damages

caused by obedience pressure.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section presents a discussion of the

obedience pressure in the context of a stress model and the factors that affect accountants’

reactions to obedience pressure. Then, the paper presents a review of prior studies’ findings

about the effects of individual-related factors. The following section discusses the effects of

contractual factors and offers an improved general model of accountants’ reactions to obedience

pressure. Finally, a summary and conclusion are presented and applications for future research

and practice are discussed.

STRESS MODEL AND FACTORS AFFECTING OBEDIENCE PRESSURE EFFECT

ON ACCOUNTANTS

According to obedience theory, a person in a position of authority can influence others

due to the power nested in the organizational hierarchy (Milgram, 1974). When obedience

pressure exists, mistakes in judgment—either intentional or unintentional—can occur.

Workplace-related psychology research has shown that a certain level of pressure can have a

positive effect on performance (Spilker & Prawitt, 1997). However, the risk of encountering

negative effects of dysfunctional behavior related to pressure is perceived as high and damaging.

Obedience pressure could lead to dysfunctional behavior, which is costly to firms (Ashton,

1990).

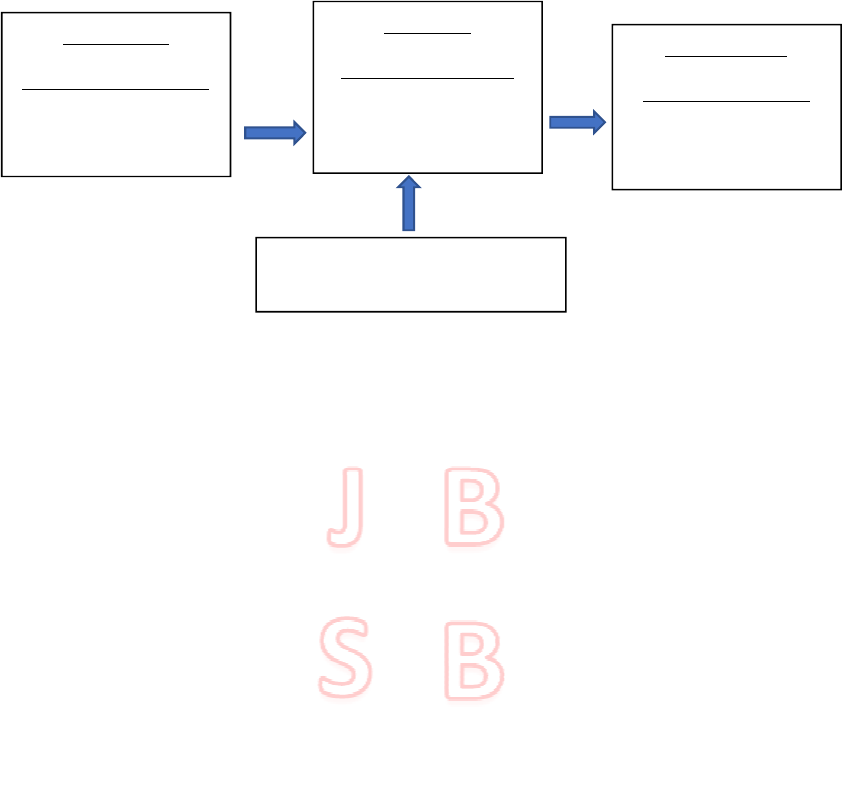

According to the general model of stress, which is presented in Figure 1, a pressure

situation has four elements: antecedent, response, consequence, and individual characteristics

(DeZoort & Lord, 1997; Summer, DeCotiis, & SeNisi, 1995; Quick & Quick, 1984). The

antecedent is a pressure stimulus, such as obedience pressure to misrepresent an account. The

response is the stress response, such as the degree of giving in to the pressure. The consequence

is a strain outcome, such as the misrepresented account. The pressure stimulus can appear in the

form of social pressure—compliance, obedience, and confirmatory—or work and business-

related pressures in general. Compliance pressure exists when an accountant is under pressure to

follow certain guideline or follow an official order. Obedience pressure can appear in the form of

a direct or indirect superior’s demand to take certain actions. Confirmatory pressure exists when

an accountant is under pressure to follow their colleagues’ behavior and conform to their actions,

which is also called peer pressure.

The fourth dimension of the model is individual characteristics, which are defined as

individual-related factors. The individual-related factors, like gender and personality, could

cause variation in individuals’ reactions to pressure. The effects of individual-related factors in

an accounting context have been the subject of several studies, which are reviewed in the next

section.

PRIOR STUDIES ON THE EFFECTS OF INDIVIDUAL-RELATED FACTORS

Several accounting studies have investigated the individual characteristics that affect

responses to obedience pressure. Clayton and Staden (2015) investigated the effect of individual

ethical judgment and found that it was not enough to eliminate the obedience pressure effect on

ethical decision-making. However, they documented that high levels of

organizational/professional commitment were effective in mitigating the effects of obedience

Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business Volume 11

Contextual factors, obedience pressure, Page 4

pressure. Lord and DeZoort (2001) investigated the effect of organizational commitment,

professional commitment, and moral development on obedience pressure. They found support

for the organizational commitment, but not for moral development and professional

commitment. Baird and Zelin (2009) investigated whether individuals that committed fraud

under obedience pressure are seen less severely than those who committed their own fraud

volition. They found support in the case of financial statement fraud, partial support in the case

of asset misappropriation, and no support in the case of corruption schemes. Hartmann and Maas

(2010) found support for the effect of Machiavellianism on subscription to obedience pressure to

involve in budgetary slack creation. They concluded the corporate controllers who were high in

Machiavellianism were more likely to give in to pressure from their superiors than controllers

who scored low.

Collins (1993) investigated the gender effect and found that female accountants who

experienced high social pressure at work had higher employee turnover. Davis et al. (2006)

found evidence of management accountants’ willingness to create budgetary slack when they

were under obedience pressure from a direct superior. Such willingness was associated with a

perceived lack of responsibility for the budget. Johnson, Lowe, and Reckers (2016) investigated

the effect of “mood” on subordinates’ ability to resist superior pressure in public accounting and

found there was willingness to comply with superiors’ unethical requests. Lord and DeZoort

(2001) found that obedience pressure increased auditors’ willingness to agree with misstated

account balances, but confirmatory pressure did not. Lord (1992) found that personal

accountability interacted with obedience pressure—auditors who were accountable for their

decisions were less probable to issue an unqualified opinion as compared to those who were

protected by a guarantee of anonymity.

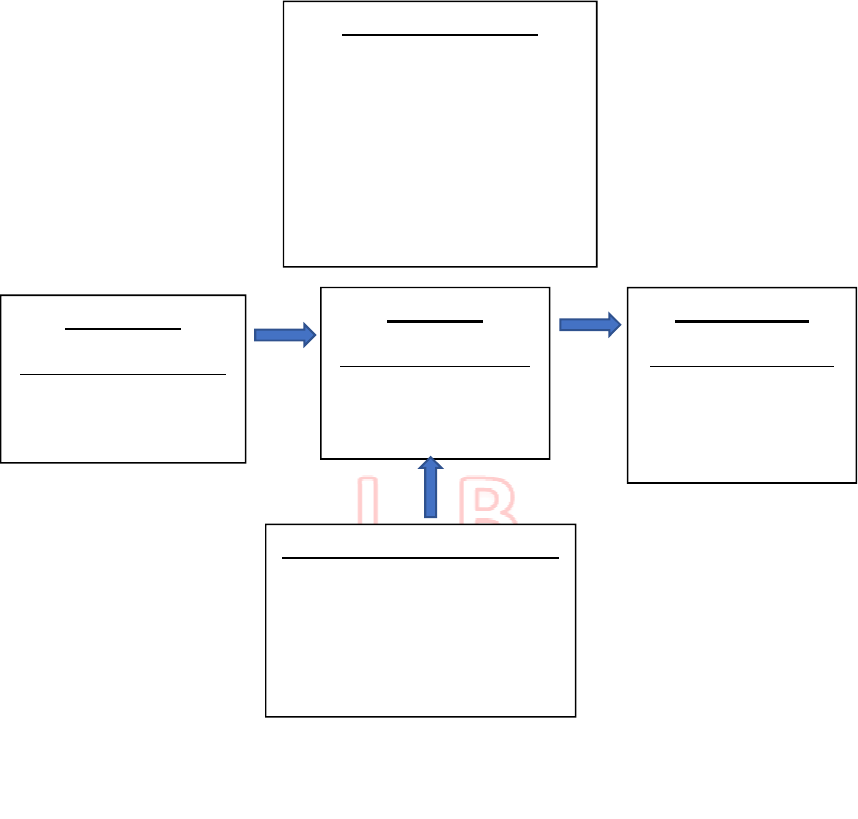

THE EFFECTS OF CONTRACTUAL FACTORS

While prior studies have presented useful information about the effects of individual-

related factors on accountants’ responses to obedience pressure, an important category of factors

has not been explained by the stress model presented in Figure 1. We define this category as

contractual factors. The contractual factors are the factors that are related to the task and the

environment in which the decision being made. According to the transactional process theory,

contractual characteristics could shape individuals’ responses to pressure and could interact with

the individual-related factors.

Transactional process theory, which is an extension of person–environment(P-E) fit

theory (Caplan, 1987), argues that stress, responses, and outcomes should be studied by

evaluating the interaction between the individual and specific pressure situations (Lazarus, 1995;

Schuler, 1982). Accordingly, the relationship between the environment in which the person

operates and the individual is dynamic, not static. According to this theory, the individual’s

perception of the pressure, along with the individual’s coping ability and skills experience, affect

their attitude and reaction to the pressure. Therefore, in addition to individual-related factors, the

underlying contractual factors can influence accountants’ reactions to obedience pressure.

Contractual factors can appear in several forms, such as the magnitude of the amount of

the issue, sensitivity of the issue, explicit conflict with laws and regulations or professional

standards, and possibility of disclosure, and can play important roles in accountants bowing to

obedience pressure. These factors are all related to the task and the environment in which the

reaction is being formed. These factors can also interact with the individual-related factors, as

Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business Volume 11

Contextual factors, obedience pressure, Page 5

individuals’ attitudes toward these factors could vary based on their personality, beliefs, and risk-

taking. An investigation of the effects of these factors could lead to a better understanding of

what actually affects accountants’ reactions to not only obedience pressure but social pressure in

general. Thus, this paper presents an improved version of the general model of stress, which was

presented in Figure 1, by expanding it to include the effect of contractual factors. The improved

model is presented in Figure 2 below.

Including the contractual factors improves and extends prior studies’ findings regarding

accountants’ reactions to obedience pressure. For example, the discussion of contractual factors

calls for revisiting the Davis et al. (2006)’s findings regarding responsibility shifting in order to

determine whether those findings still hold after considering the effects of contractual factors.

Similarly, it is beneficial to examine whether the effects of Machiavellianism and involvement in

the management activities documented by Hartmann and Maas (2010) will change when the

effects of contractual factors are considered. For example, will Machiavellians still give in to

obedience pressure when the contractual factors are unfavorable to them.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

This paper extends the discussion of the obedience pressure effect on accountants’ ability

to exercise independent professional judgment. The discussion of factors that affect accountants’

susceptibility to obedience pressure is interesting, both from theoretical and practical

perspectives, and could lead to the better management of dysfunctional behavior caused by

obedience pressure. This paper contribute to the discussion of the factors that could affect

accountants’ reactions to obedience pressure by introducing the effect of contractual factords.

These factors, in addition to individual-related factors that are discussed in the literature, can

assist researchers and practitioners in understanding the formation of accountants’ reactions to

obedience pressure. They are the magnitude of the amount, the sensitivity of the issue, explicit

conflict with laws and regulations or professional standards, and the possibility of disclosure.

Future empirical investigation of these factors could be beneficial to examine their effectiveness.

Understanding the effects of these factors would also benefit practitioners’ ability to reduce the

dysfunctional behavior of accountants and mitigate the damage that is caused by obedience

pressure. For example, it would be beneficial to know which contextual factors motivate

different individuals with different personalities and ethics to resist obedience pressure.

REFERENCES

Ashton, R. H. (1990). Pressure and performance in accounting decision settings: Paradoxical

effects of incentives, feedback and justification. Journal of Accounting Research,

28(Supplement), 148–180.

Baird, J. E., & Zelin, R. C. (2009). An examination of the impact of obedience pressure on

perceptions of fraudulent acts and the likelihood of committing occupational fraud.

Journal of Forensic Studies in Accounting & Business, 1(1), 1–14.

Brehm, J. W., & Brehm, S. S. (1981). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control.

New York, NY: Academic Press.

Brink, A. G., Gouldman, A, & Victoravich, L. M. (2018). The effects of organizational risk

appetite and social pressure on aggressive financial reporting behavior. Behavioral

Research in Accounting (in press).

Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business Volume 11

Contextual factors, obedience pressure, Page 6

Bruce M. Clayton, Chris J. van Staden. The Impact of Social Influence Pressure on the Ethical

Decision Making of Professional Accountants: Australian and New Zealand Evidence

First published: 14 December 2015

Buchheit, S. S., Pasewark, W. R., & Straser, J. R. (2003). No need to compromise: Evidence of

public accounting’s changing culture regarding budgetary performance. Journal of

Business Ethics, 42(2), 151–163.

Caplan, R. D. (1987). Person-environment fit theory and organizations: Commensurate

dimensions, time perspectives, and mechanisms. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31(3),

248–267.

Collins, K. M. (1993). Stress and departure from the public accounting profession: A study of

gender differences. Accounting Horizons, 7, 29–38.

Davis, S., DeZoort, F. T., & Kopp, L. S. (2006). The effect of obedience pressure and perceived

responsibility on management accountants' creation of budgetary slack. Behavioral

Research in Accounting, 18(1), 19–35.

DeZoort, F. T., & Lord, A. T. (1997). A review and synthesis of pressure effects research in

accounting. Journal of Accounting Literature, 16, 28-85.

Elliott, G. R., & Eisdorfer, C. (Eds.). (1982). Stress and human health: Analysis and implications

of research. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Hartanto, Y. H., & Kusuma, I. W. (2002). Pressure influence analysis obedience against

judgment auditor. Journal of Accounting and Management, (May), 1–12.

Hartmann, F. G. H., & Maas, V. S. (2010). Why business unit controllers create budget slack:

Involvement in management, social pressure, and Machiavellianism. Behavioral

Research in Accounting, 22(2), 27–49.

Johnson, E. N., Lowe, D. J., & Reckers, P. M. J. (2016). The influence of mood on subordinates'

ability to resist coercive pressure in public accounting. Contemporary Accounting

Research, 33(1), 261–287.

Lazarus, R. S. (1995). Psychological stress in the workplace. In R. Crandall & P. L. Perrewe

(Eds.). Occupational stress: A handbook (pp. 3–14). Washington, DC: Taylor and

Francis.

Lord, A. T. (1992). Pressure: A methodological consideration for behavioral research in auditing.

Auditing, 11(2), 90–112.

Lord, A. T., & DeZoort, F. T. (2001). The impact of commitment and moral reasoning on

auditors’ responses to social influence pressure. Accounting, Organization and Society,

26(3), 215–235.

McNair, C. J. (1991). Proper compromises: The management control dilemma in public

accounting and its impact on auditor behavior. Accounting, Organization and Society,

16(7), 635–653.

Meyer, M., & Rigsby, J. T. (2001). A descriptive analysis of the content and contributors of

behavioral research in accounting. Behavioural Research in Accounting, 13(1), 253–278.

Milgram, S. (1974). The dilemma of obedience. The Phi Delta Kappan, 55(9), 603–606.

Nugrahanti, T. P., & Jahjam, A. S. (2018). Audit judgment performance: The effect of

performance incentives, obedience pressures and ethical perceptions. Journal of

Environmental Accounting and Management, 6(3), 225–234.

Putri, P.A., & Laksito, H. (2013). The influence of the ethical environment, the experience of

auditors and the pressure of compliance with the quality of audit judgment. Diponegoro

Journal of Accounting, 2, 123–131

Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business Volume 11

Contextual factors, obedience pressure, Page 7

Quick, J. C, & Quick, J. D. (1984). Organization stress and preventive management. New York,

NY: McGraw-Hill.

Schuler, R. S. (1982). An integrative transactional process model of stress in organizations:

SUMMARY. Journal of Occupational Behavior 3(1), 5-20.

Shafer, W. E., Morris, R. E., & Ketchand, A. A. (2001). Effects of personal values on auditors’

ethical decisions, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 14(3), 254–277.

Shafer, W. E., & Wang, Z. (2011). Effects of ethical context and Machiavellianism on attitudes

toward earnings management in China. Managerial Auditing Journal, 26(5), 372–392.

Spilker, B. C., & Prawitt, D. F. (1997). Adoptive responses to time pressure: The effect of

experience on tax information search behavior. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 9,

172–198.

Summer, T. P., DeCotiis, T. A., & SeNisi, A. S. (1995). A field study of some antecedents and

consequences of felt job stress. In R. Crandall and P. L, Perrewe, P. L. (Eds.).

Occupational stress: A handbook. Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis.

Tsui, J. S. L., & Gul, F. A. (1996). Auditors’ behavior in an audit conflict situation: A research

note on the role of locus of control and ethical reasoning. Accounting, Organization and

Society, 21(January), 41–51.

Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business Volume 11

Contextual factors, obedience pressure, Page 8

Figure 1: General model of stress. Adapted from Davis et al. (2006), DeZoort and Lord (1997),

Summer et al. (1995), and Elliott and Eisdorfer (1982).

Antecedent

Pressure Stimulus (x)

Such as obedience

pressure.

Response

Stress Response (y)

Such as bowing to

pressure.

Consequence

Strain Outcome (z)

Biased professional

judgment.

Individual Characteristics

Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business Volume 11

Contextual factors, obedience pressure, Page 9

Figure 2: General model of accountants’ reactions to obedience pressure.

Antecedent

Pressure Stimulus (x)

Such as obedience

pressure.

Response

Stress Response (y)

Such as bowing to

pressure.

Consequence

Strain Outcome (z)

Such as biased

professional

judgment.

Individual-Related Factors

Such as gender, ethical

position, personality,

management involvement,

and responsibility shifting.

Contractual Factors

Such as magnitude of the

amount, sensitivity of the

issue, explicit conflict with

laws and regulations or

professional standards, and

possibility of disclosure.