Header

COVER

T R A N S I T O R I E N T E D D E V E L O P M E N T

Lessons

TOD

Learned

Results of FTA’s Listening Sessions With Developers, Bankers,

and Transit Agencies on Transit Oriented Development

U.S. Department of Transportation

With Thanks To:

Federal Transit Administration

Portland, Oregon

December 2005

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Phoenix, Arizona

Charlotte, North Carolina

TOD and the American Dream

I

n the popular imagination, the American Dream brings

visions of a suburban home with a big back yard and a

car in the garage to carry “Dad” into and out of the city

for his job each day. This image recalls the postwar baby boom

that went hand in hand with the suburban boom. In 1954, an

estimated 9 million people had moved to the suburbs since

the end of World War II, lured by affordable, massproduced,

single-family homes on the peripheries of cities.

But, if demography is destiny, the prospects look

bright for a new, twenty-rst century version of the American

Dream — one shaped by transit, the development it attracts,

and a growing appetite for affordable housing in urban areas.

Population groups that covet housing very close to transit are

precisely the populations that will grow exponentially in the next

decades. They include older Americans who will comprise 35

percent of our population by 2025; immigrant families who will

account for almost one-third of population growth in the next

two decades; and the nearly 70 percent of households without

children. The Twin Cities (Minneapolis and St. Paul) alone are

on pace to add 930,000 residents in the next 25 years, and many

of the new residents will seek out housing near transit. Between

them, the cities of Minneapolis/St. Paul, Portland, Oregon,

Phoenix, and Charlotte could add over 445,000 households in

transit zones by 2025.

Skeptics will say that suburban developments that

depend on cars get built because that is how people want to

live. But communities across the nation, from Charlotte to

Portland to Washington D.C., have proven that there are many

variations on the American Dream. These communities have

demonstrated that transit-oriented development supports the

timeless essence of the American Dream: the dream of owning

a home; of living in an attractive, thriving neighborhood; of

setting down roots and feeling part of a community; of enjoying

the walk to a neighborhood coffee shop or a short train ride

to see a movie. Transit-oriented development promises to let

Americans hang a gurative sign on suburban sprawl that says,

“The American Dream: Visit Us At Our New Location.”

This booklet summarizes the results of listening sessions

that the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) has undertaken

with several cities in which new transit investments either have

taken place, or are about to be built. We hoped that by listening

to the planners, developers, and bankers in these communities,

we could learn what works, what doesn’t work, and what

facilitates the kind of community that we believe exemplies

the American Dream.

What do we mean by “TOD”?

• “TOD” is transit-oriented development

• To begin with, it is a neighborhood or community centered on a transit

station.

• It has enough density of people and activities to use the transit station to

access a variety of daily activities.

• It includes a mix of uses, including residential, retail, and commercial,

within easy walking distance of the transit station.

• The station and its neighborhood have to have good service, including

good connections with other transportation such as neighborhood buses

and bicycle trails.

• The streets around the station are easy to walk, and attractive to pedes-

trians and bicyclists.

...and what are its benets?

• A better t of the transit service into the neighborhood.

• More people using the transit system for every day activities.

• A more pedestrian-friendly, human-scale community that is safe,

relaxing, and attractive.

• A healthier, cleaner environment as more people walk and bicycle

and take public transportation.

• Preservation of farmland and green space as people use less land

to live, work and play.

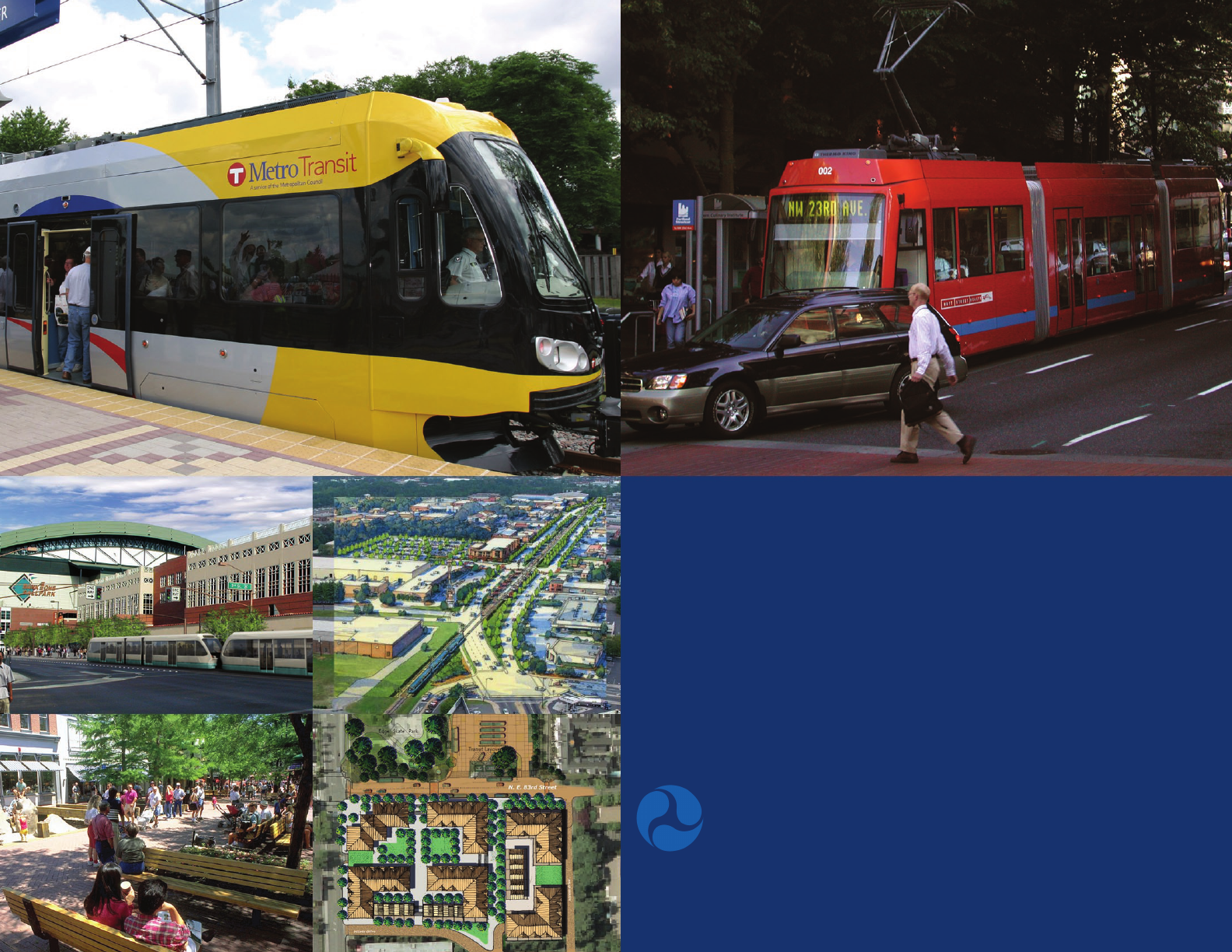

Metro Transit, Minneapolis, MN

Metro Transit, Minneapolis, MN

...and what are its benets?

FTA Listening Sessions

F

TA held listening sessions around the country to learn

about what has worked and what has not worked in start-

ing up transit-oriented developments.

We visited Portland, where the region has embraced land use and

transportation planning for many years, and where the light rail

system is large and growing. We visited Minneapolis, an older,

larger city where the rst light rail segment had just gone into rev

-

enue service. And we visited Phoenix and Charlotte, places where

the light rail systems are still under construction.

Our goal was to discover whether there are basic lessons we could

learn and pass on about fostering new, transit-supportive develop-

ment around new public transportation systems. What follows are

those basic ideas, as told to us by municipal, banking, and develop-

ment leaders in each city.

In addition to these success stories, the ideas are organized in

three broad categories: Overcoming Barriers; Promoting TOD;

and Identifying Research Opportunities. This booklet concludes

with some highlights of what FTA is doing right in TOD now and

our next steps.

Metro Transit, Minneapolis, MN

Overcoming Barriers

TOD makes inherent sense in our dispersed, congested, and hectic lives. We want to

live near many activities, including work, shopping, medical care, and entertainment.

However, most developers and bankers have been reluctant to build and invest in

such communities. For example:

• Few rms that nance development are familiar with TOD, as

such with fewer bankers, nancing is more expensive and harder

to come by.

• TOD is design-intensive, often requiring land assembly, land-

scaping, and plans for supportive infrastructure such as roads or

bike trails. These factors raise startup costs.

• Structured parking, and the amount of parking required per resi-

dence or per ofce, often raise the cost of TOD or delay imple-

mentation.

• TOD often requires holding developed property for longer terms

than single-use development – that is, for seven or ten years, as

opposed to ve, making it harder to turn a quick prot.

• Because the attractiveness of riding on and living near tran-

sit depends on the number and variety of destinations that are

reachable by transit, a limited transit network limits the appeal of

TOD.

“Creating walkable neighborhoods with attractive

transit options requires innovation and determi-

nation by developers, nancial partners, local ju-

risdictions and the transit agency. In the Portland

metro area, consumer demand for transit oriented

development is strong and growing.”

- Fred Hansen, General Manager, Tri-Met

• Some question transit’s ability to generate new economic activ-

ity, rather than simply relocate economic growth that would occur

elsewhere. This makes it difcult for elected ofcials to maintain

the long-term perspective necessary to support a transit invest-

ment that takes ten years or more to complete.

• Neighbors often oppose high-density development near their

community and it may be difcult to convince neighbors to re

-

zone nearby land for the densities needed to support high quality

development projects.

With many challenges to overcome, are any

Success Stories

TOD’s being built? Of course there are!

• The image on the right is from the Pearl District, which has become

a new 24-hour community in downtown Portland, Oregon. Loft apart

-

ments, restaurants, shops, and services have been revitalized since the

Portland Streetcar service began in July 2001.

• Down the coast, in Santa Clara County, California, the Ohlone Chyn-

oweth station was redesigned as a mixed-use community, including a

pedestrian village center, apartments, and retail space. Part of the land

used for the development provides a revenue stream to the Valley Tran

-

sit Authority.

• On the opposite coast, in Baltimore, Maryland, the metro station at

Center Square has provided the opportunity for the City to offer 30

acres for redevelopment as TOD. It will link the metro station with a

light rail station surrounded by many existing city and county ofces and

cultural attractions. The Maryland Department of Transportation held a

public design charrette to help dene the project.

• Further south, in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, Southern Bell Corpora-

tion has consolidated several of its ofces into a single TOD develop-

ment around the Lindbergh Metro station. This development includes

commercial ofces, retail, and residential space, all centered on the metro

station.

These are only a few of the projects we are working on with our part-

ners to emulate across the country.

Portland Streetcar, Portland, OR

So what do these success stories all have in

Promoting TOD

common? What does it take to promote TOD?

Proactive Planning – Local and regional entities must in-

vest in community outreach and a master plan - a signal to

the development community that the public is eager for

TOD. Participants stressed the need to take time to do the

planning process right.

Focus on Mixed-Use Development – Building commer-

cial, employment, and entertainment centers near transit

stops provides an opportunity to increase the number and

quality of destinations reachable by the transit network.

Land Assembly – Preserve and assemble parcels around

transit stations to facilitate eventual development.

Public Funding – TOD projects may be encouraged if site

preparation and related startup costs are partially nanced

with Federal, State and local funds as part of a transit project

as allowed by Federal Transit laws (Section 5302).

One Size Doesn’t Fit All – Each station’s development re-

quirements may be different, as each town or each neighbor-

hood is different.

Above, Boulder, CO.

Left, Scaleybark Road

Station, Charlotte, NC.

Promoting TOD

“Pro-active implementation. Go out, gure out what the devel-

SEPTA Trolley, Media, PA

Prepare For What You Need – Conduct a market analysis, then

request the zoning changes to meet the market.

Timing is Key – Current property values may be based on a low-

er capacity, non-transit use – make sure the property is ready for

TOD.

Placemaking Matters – Many are willing to pay a higher mar-

ket rate if improvements are visible in the environment and

streetscape, such as with trees, sidewalks, lighting, etc.

opers need in order to make the transportation there more com-

petitive and try to respond. The mayor mentioned the zoning.

Try to go out and pre-zone land for that type of development.

And most importantly, outreach education and partnerships, be-

cause without you as our partners this isn’t going to be a vision

that we accomplish… I mean, honestly, how many of you 5, 10,

20 years ago would ever think that Charlotte would get to this

point?”

- Debra Campbell, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Planning Commission

Portland Streetcar, Portland, OR

Identifying Research Opportunities

Additional Market Research – Participants want more information on the market for TOD

and what type of product is most attractive.

Documenting the economic benets of transit - Respondents believe that economic mod

-

eling from the FTA would provide an independent source of information that could break

political bottlenecks over transportation investments.

Interagency Coordination - FTA could partner with other Federal agencies to coordinate

transit, housing, and environmental policy.

Research on Land Assembly and Joint Development - Participants want more information

on how to best make land available and assemble and clean up parcels that have good potential

for TOD.

What we’re doing now...

FTA has initiated a joint project with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Devel-

opment to study how public transportation works with affordable housing.

The University Transportation Center at the University of California, Berkeley, is research-

ing performance measures to use in evaluating the success of TODs for FTA.

FTA is revising its joint development policy to clarify requirements and implement new

authority provided by the recent surface transportation authorization.

FTA is preparing a joint development web site, that will include guidance for joint devel-

opment, a listing of existing joint development projects, and contact information for cur-

rent TOD and joint development practitioners.

Header

Credits

Credits

Cover:

Top Left: Metro Transit, Minneapolis, MN

Top Right: Portland Streetcar, Portland, OR/Paul Marx, 2004

Bottom Left, Clockwise from Top Left:

Phoenix, AZ; Scarleybark Road Station, Charlotte, NC; Redmond Downtown Project, King County, WA; Boulder, CO.

1. What do we mean by TOD?/Metro Transit, Minneapolis, MN/Paul Marx, 2004

2. ...and what do we get from it?/Metro Transit, Minneapolis, MN/Paul Marx, 2004

3. FTA held listening sessions/Metro Transit, Minneapolis, MN/Metro Transit/Illustration by Tony Cho

4. Success Stories/Portland Streetcar, Portland, OR/Paul Marx, 2004

5. Promoting TOD/Boulder, CO.

6. Promoting TOD/Scaleybark Road Station, Charlotte, NC.

7. Promoting TOD/SEPTA Trolley, Media, PA/Tony Cho, 2004

8. Promoting TOD/Portland Streetcar, Portland, OR/Paul Marx, 2004

Header

Back Cover

For more information, please contact:

Ofce of Policy and Performance Management

Federal Transit Administration

400 7th St. SW, Room 9310

Washington, DC 20590

Phone: (202) 366-4050

Fax: (202) 366-7989