9?0=9,?4:9,7:@=9,7:1<@,?4.&0>0,=.3,9//@.,?4:99?0=9,?4:9,7:@=9,7:1<@,?4.&0>0,=.3,9//@.,?4:9

*:7@80

"@8-0=

';0.4,7>>@04A0=>4?D49<@,?4.>

=?4.70

A,7@,?4:9:1,=:B9492$=0A09?4:9,8;,42949,*40?9,80>0A,7@,?4:9:1,=:B9492$=0A09?4:9,8;,42949,*40?9,80>0

80=4.,9:88@94?D80=4.,9:88@94?D

49/,%@,9!

)94A0=>4?D:1+,>3492?:9'.3::7:1!0/4.490

749/,<@,9>0,??70.347/=09>:=2

709,'30;3,=/!

)94A0=>4?D:1+,>3492?:9'.3::7:1!0/4.490

0709,>30;3,=/>0,??70.347/=09>:=2

74E,-0?30990??'!$

'0,??70347/=09>:>;4?,7

074E,-0?3-0990??>0,??70.347/=09>:=2

:77:B?34>,9/,//4?4:9,7B:=6>,?3??;>>.3:7,=B:=6>-2>@0/@45,=0

$,=?:1?30>4,9'?@/40>:88:9>:88@94?D0,7?3,9/$=0A09?4A0!0/4.490:88:9>

/@.,?4:9,7>>0>>809?A,7@,?4:9,9/&0>0,=.3:88:9>C0=.4>0'.409.0:88:9>0,7?3,9/

$3D>4.,7/@.,?4:9:88:9>9?0=9,?4:9,7$@-74.0,7?3:88:9> 04>@=0'?@/40>:88:9>';:=?>

'.409.0>:88:9>,9/?30(:@=4>8,9/(=,A07:88:9>

:B/:0>,..0>>?:?34>B:=6-090F?D:@ 0?@>69:B:B/:0>,..0>>?:?34>B:=6-090F?D:@ 0?@>69:B

&0.:8809/0/4?,?4:9&0.:8809/0/4?,?4:9

%@,9 49/,!'30;3,=/709,!,9/0990??74E,-0?3'!$A,7@,?4:9:1,

=:B9492$=0A09?4:9,8;,42949,*40?9,80>080=4.,9:88@94?D

9?0=9,?4:9,7:@=9,7:1<@,?4.

&0>0,=.3,9//@.,?4:9

*:7":=?4.70

#3??;>/:4:=245,=0

A,47,-70,?3??;>>.3:7,=B:=6>-2>@0/@45,=0A:74>>

(34>&0>0,=.3=?4.704>-=:@23??:D:@1:=1=00,9/:;09,..0>>-D?30:@=9,7>,?'.3:7,=+:=6>')?3,>

-009,..0;?0/1:=49.7@>4:9499?0=9,?4:9,7:@=9,7:1<@,?4.&0>0,=.3,9//@.,?4:9-D,9,@?3:=4E0/0/4?:=:1

'.3:7,=+:=6>')

A,7@,?4:9:1,=:B9492$=0A09?4:9,8;,42949,*40?9,80>080=4.,9A,7@,?4:9:1,=:B9492$=0A09?4:9,8;,42949,*40?9,80>080=4.,9

:88@94?D:88@94?D

:A0=$,20::?9:?0:A0=$,20::?9:?0

(34>>?@/DB,>>@;;:=?0/49;,=?-D,2=,9?1=:8?30+,>3492?:9.3,;?0=:1?3080=4.,9.,/08D:1

$0/4,?=4.>+0B:@7/7460?:,.69:B70/20:@=;,=?90=>'0,??70$,=6>,9/&0.=0,?4:9<@,?4.>0>;0.4,77D

!460$7D8;?:94,90:90>,9/,?3D+34?8,9 D99B::/$,=6>,9/&0.=0,?4:9$@-74.0,7?3'0,??70

,9/492:@9?D0>;0.4,77D(:9D:80E95@=D=00:,74?4:91:=4/>:1'0,??700>;0.4,77D094>0

:9E,70>,9/=4,9:39>?:9!094>0 :@400,/'?,=?,9/+,>3492?:9'?,?0$,=6>,9/&0.=0,?4:9

+0/,7>:7460?:?3,96,?D ,8'=0;=0>09?492?30*40?9,80>0$=:10>>4:9,7>':.40?D(:94:,9/(=4

0:1'0,??70347/=09>:>;4?,748 @9/2=09@7?@=,7,>0B:=60=1=:8,=-:=A40B!0/4.,709?0=:@=

*40?9,80>0.:88@94?D.::=/49,?:=>,9/'@>,99,,92D:@?3B,?0=>,10?D,/A:.,?0

(34>=0>0,=.3,=?4.704>,A,47,-70499?0=9,?4:9,7:@=9,7:1<@,?4.&0>0,=.3,9//@.,?4:9

3??;>>.3:7,=B:=6>-2>@0/@45,=0A:74>>

Abstract

To address Washington State’s high pediatric fatal drowning rates in Asian

children, especially Vietnamese, we conducted and evaluated a community water

safety campaign for Vietnamese American families. Working with community

groups, parks departments and public health, we disseminated three messages

(learn to swim, swim with a lifeguard, and wear a life jacket) in Vietnamese media

and at events, increased access to free/low cost swim lessons and availability of

lifeguarded settings and life jackets in the community. Parents completed 168 pre-

and 230 post-intervention self-administered, bilingual surveys. Significantly more

post-intervention compared to pre-intervention respondents had heard water safety

advice in the previous year, (OR 8.75 (5.07, 15.09)) and had used lifeguarded sites

at lakes and rivers (OR 2.3 (1.04,5.08)). The campaign also increased community

assets: availability of low-cost family swim lessons, free lessons at beaches, low

cost life jacket sales, life jacket loan kiosks in multiple languages, and more Asian,

including Vietnamese, lifeguards.

Keywords: drowning, drowning prevention, water safety, social marketing, health

disparities

Introduction

Fatal drowning rates vary among different races and ethnicities of United States

children less than 18 years. In 2017, African Americans had the highest adjusted

unintentional drowning rates per 100,000 persons (1.29) and Asian Americans, the

lowest (1.07) (Gilchrist & Parker, 2014). In the Western United States from 2013-

2017, Asians had the second highest drowning rate among 5-9 year olds, 10-14 year

olds and 15-19 year olds (Centers for Disease Control, 2020).

Centers for Disease Control data shows that in Washington State, drowning

is the second major cause of unintentional injury related death from birth to 19

years. From 2013-2017, Asians had the second highest fatal drowning rates among

5-9 year olds, 10-14 year olds and highest among 15-19 year olds. These rates are

greater than the overall crude fatal drowning rate for each of those age groups

(Centers for Disease Control, 2019; 2020). A Child Death Review (CDR) report

identified that in Washington state between 1999 to 2003, Asian/Pacific Island

children had the highest rates of drowning deaths of children less than 18 years (3.1

per 100,000), double that of white children (1.5) (Quan, Pilkey, Gomez & Bennett,

2011; Washington State Department of Health, 2004). In contrast, national

drowning rates during the same time period for children less than 18 were lowest

among Asian/Pacific Island children (1.2 per 100,000), compared to rates of 2.15

for African American, 1.93 for Native American and 1.31 for white children

(Centers for Disease Control, 2019). During this time period, several local, high

1

Quan et al.: Prevention Campaign for Vietnamese Americans

Published by ScholarWorks@BGSU, 2020

profile open water swimming-related drownings in Washington involved local

Vietnamese American school-aged children.

Our goal was to develop and conduct a community based drowning

prevention campaign based on our local experience with drownings among

Vietnamese American children. At that time, the few studies addressing drowning

and its prevention among Asian immigrants were surveys of behaviors and attitudes

of Asian New Zealanders (McCool et al., 2008; Moran, 2008). The only study of

Asian Americans reported they lacked experience, safety principles and practical

competencies around water activities compared to white peers, even when

controlling for socioeconomic status (Allen et al., 2007). No studies had

specifically addressed drowning risks and prevention amongst Vietnamese

immigrants. Since the Asian American population represents multiple ethnic and

cultural groups from wide ranging locales, specific cultural and linguistic

approaches were needed for drowning prevention in this ethnic group.

First, in 2005, we conducted focus groups of local Vietnamese American

teens and parents to understand their skills, behaviors and beliefs around

swimming, life jacket use and drowning risk. We published our findings that

participants did not take part in water sports, were unaware of the risks and lacked

water safety and swimming skills (Quan, Crispin, Bennett & Gomez, 2006). Based

on these findings, we developed a drowning prevention campaign whose objectives

were to increase awareness of drowning and drowning prevention, increase safe

behaviors around water and facilitate acquisition of water safety skills. The purpose

of this study was to describe the development, components and evaluation of a

drowning prevention campaign for a previously untargeted diverse minority

community.

Method

Setting:

Vietnamese American communities of Seattle area

In the 2000 U.S. Census, Washington State had the third largest number of

Vietnamese people nationally (50,687). Of these, 74% were foreign born and 89%

spoke another language besides English at home (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). In

the Seattle area, Vietnamese was one of the top four non-English languages spoken.

Vietnamese residents numbered 11,943 making them the third largest group of

Asians (17%) with the highest number of linguistically isolated households (49%).

Vietnamese Americans lived primarily in the Central and South Seattle districts,

which had the largest numbers of non-whites, the highest injury rates leading to

hospitalization, and the lowest socioeconomic status in the Seattle area.

2

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, Vol. 12, No. 3 [2020], Art. 4

https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare/vol12/iss3/4

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.12.03.04

Campaign Development

To develop the campaign, PRECEDE-PROCEED was used as a framework. (Green

& Kreuter, 2005; Kotler et al., 2002; Lefebvre & Rochlin, 1997). It provides a

robust structure for assessing health needs and assets by addressing predisposing,

enabling, and reinforcing factors. Key constructs we used included the following:

Social assessment of how families recreated around water and their concerns;

epidemiological assessment using the CDR data and report; educational and

ecological assessment using the CDR data and focus group report to identify

predisposing, reinforcing and enabling factors; and community assessment and

meetings with community leaders to identify administrative issues. These findings

were then used to develop the resources, messaging and focus areas for the

campaign (Table 1).

Principles of Social Marketing, which takes traditional marketing strategies

and applies them to achieving social good, including health behavior change

(Kotler et al., 2002; Lefebvre & Rochlin, 1997), were also used and included:

Audience segmentation – we narrowed our focus to Vietnamese families in the

Seattle area; use of formative research in message development – we used findings

from our focus groups with Vietnamese parents and teens; development of specific

communication channels – we communicated using Vietnamese specific media and

events; tailored messaging – we developed culturally specific and unique education

materials, photos and posters based on focus group input; incorporation and

promotion of a tangible object or service – we promoted and facilitated use of life

guarded swim areas, free lifejackets and low cost/free swim lessons and family

swim periods at local pools; and easy access and development of an appealing

location for the product or service – we provided translated resources with

culturally tailored visuals and messages at water locations, events and venues with

large numbers of Vietnamese families.

To identify participants, community assets, culturally and linguistically

appropriate strategies and ideas for how to present the drowning problem to the

community, we met with community leaders, liaisons and other collaborators such

as public health and parks and recreation. At their recommendation, we prioritized

families at Vietnamese language schools, Head Start programs that primarily serve

Asian children (Head Start is a Federal program for low-income preschool

children), church and temples’ family groups, and the Têt festival venues.

Community representatives, including Vietnamese Professionals Society, three

Vietnamese Language Schools, Denise Louie Head Start, Seattle Parks and

Recreation, Lynnwood Parks, Washington State Parks, Injury Prevention Division

of Public Health Seattle & King County, and the Injury Free Coalition for Kids of

Seattle, also participated in the evaluation process.

3

Quan et al.: Prevention Campaign for Vietnamese Americans

Published by ScholarWorks@BGSU, 2020

We chose three key drowning prevention messages for the campaign: learn

to swim, swim with a lifeguard and wear a lifejacket. Selection was guided by the

state’s CDR of drowning deaths, focus groups (Quan et al., 2006) and an

assessment of community assets such as lifeguarded swim areas.

Learn to Swim was chosen because teen focus group participants reported

lack of swim skills but asked to start lessons immediately. Parents in focus groups

reported swimming was not a recreational activity in Vietnam; they lacked swim

skills and did not own swimsuits. Moreover, parents believed children should not

learn to swim until nearly 8 years of age although they were aware that white

children learned earlier (Quan et al., 2006).

Swim with a Lifeguard was chosen because focus groups of parents and

teens reported they could not swim and lacked water rescue skills and knowledge

of local waters. Parents did not enter the water when supervising children and did

not supervise children who had learned to swim or were “old enough”. Both parents

and teenagers stated that peer pressure caused Vietnamese teenagers to swim with

white peers despite lacking skills (Quan et al., 2006).

Wear a Lifejacket was chosen because the community stated they recreated

around open water settings, i.e. lakes and rivers, and avoided swimming pools.

These messages were disseminated by posters and handouts (printed in

Vietnamese and English), in oral presentations at small (classes or church meetings)

and at large public functions such as the Têt festival, and via a multimedia campaign

(see Table 1).

Process Measures That Were Tracked

To increase community awareness:

• Held seven informational presentations at churches, temples, language

schools, and a Head Start Preschool program.

• Developed posters illustrating the three messages in Vietnamese, which

were disseminated to more than 200 community stores, clinics, and

organizations that catered to Vietnamese families.

• Published an Op Ed article written by a board member of the Vietnamese

Professionals Society in the three Vietnamese newspapers.

• Developed a bilingual brochure with Seattle Parks on how to access free

and low cost swim lessons and life jackets as well as the location of local

lifeguarded public pools and beaches.

• Provided information booths at four community health fairs.

4

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, Vol. 12, No. 3 [2020], Art. 4

https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare/vol12/iss3/4

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.12.03.04

To develop, expand, and promote use of free and low-cost swimming opportunities

and lessons:

• Hosted three free Vietnamese family water safety and swim sessions at

lifeguarded public pools with Vietnamese interpreters, attended by 25, 46,

and 140 persons.

• Worked with Seattle Parks and Recreation to translate the letters sent to

Seattle school families, which promoted use of free swim lesson vouchers

for third and fourth graders.

To increase availability and use of lifeguarded sites:

• Worked with Washington State Parks to reinstate lifeguarding at two

popular local parks; Seattle Parks reinstated lifeguards at two beaches.

• Seattle Parks and Recreation worked to increase numbers of Asian

American adolescents trained to be swim aids or lifeguards.

To increase lifejacket use:

• Increased the number of lifejacket loaner boards at city swim beaches,

added visuals of Asian children and parents borrowing lifejackets; and

translated instructions on their use into Vietnamese.

• Posted a banner promoting lifejackets featuring Asian American children at

all eight Seattle indoor public pools.

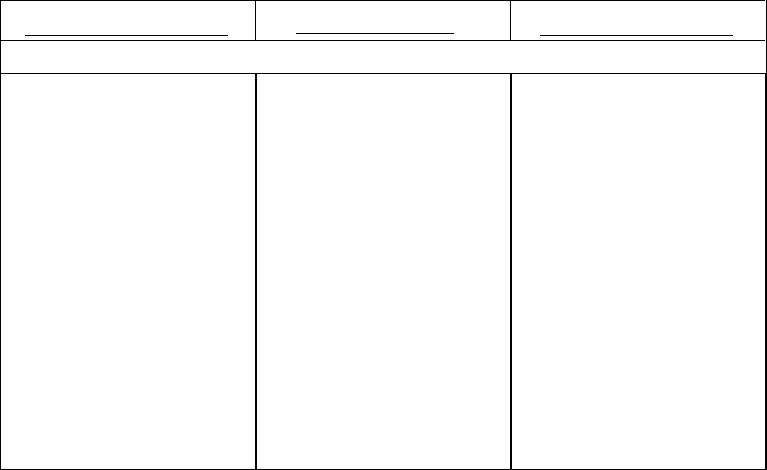

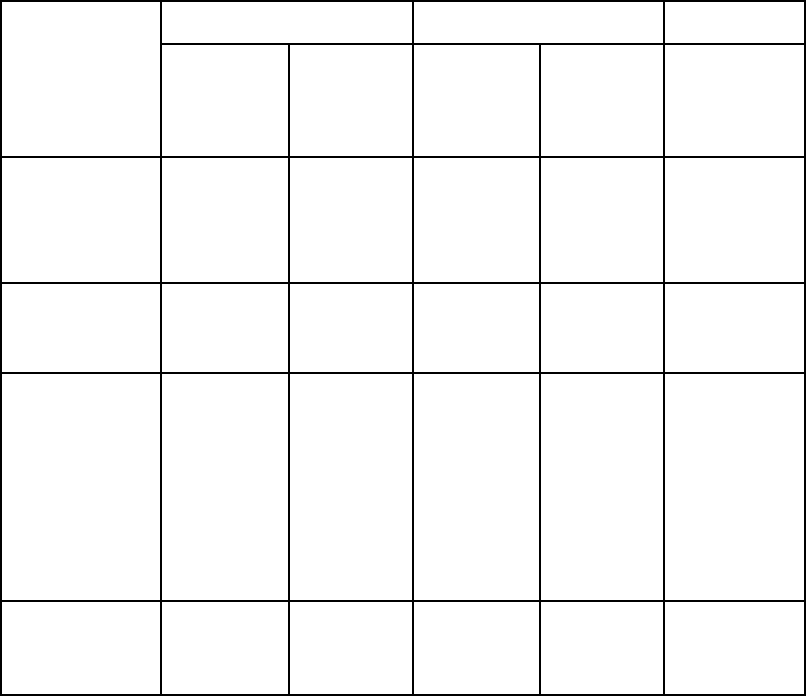

Table 1

Campaign elements incorporating Predisposing, Enabling and Reinforcing factors

Predisposing factors ͣ

Enabling factors

b

Reinforcing factors ͨ

Learn to Swim

Parents see drowning as fate

Promote free and low cost

swim lessons

Participation in dominant

culture water activities

Never perceived a need to

know how to swim

Translate information about

free lessons into Vietnamese

Tailored posters with photos

of Vietnamese families at

community locations

Swim lessons needed later

Provide free family swims

Visuals/messaging/media in

Vietnamese newspapers

Interested in water safety

Recruit Vietnamese Asian

swim aids

Provide brochure/

education sessions promoting

free/low cost swim lessons

5

Quan et al.: Prevention Campaign for Vietnamese Americans

Published by ScholarWorks@BGSU, 2020

Predisposing factors ͣ

Enabling factors

b

Reinforcing factors ͨ

Life Jacket

Life jacket is not necessary

except in a boat

Promote free life jacket loan

at all pools and beaches

Posters/handouts/media

reinforce benefits and

modeling by Vietnamese

families

Expensive

Translate life jacket loaner

board instructions and

provide visual instructions

Life jacket fashion shows for

teens

Bulky

Provide life jacket education

program and low cost sale at

Head Start schools

Free life jacket drawings at

events

Provide brochure/education

session promoting free/low

cost life jackets

LifeGuard

Parents/teens lack swim

skills

Promote life guarded

beaches/pools

Parents more assured for

child’s safety

Parents want to keep kids

safe

Recruit Vietnamese/Asian

lifeguards

Posters/handouts/media

reinforce benefits

Parents do not go in the

water to supervise

Provide brochure and

education session promoting

lifeguarded pools and

beaches

Believe that older children

need less supervision

Recognize peer pressure

among teens

ͣ Predisposing factors: Includes knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, personal preferences, existing skills and self-

efficacy towards the desired behavior

b

Enabling factors: Includes skills or physical factors such as availability and accessibility of resources or

services that help motivate desired behavior

ͨ Reinforcing factors: Includes factors that reward or reinforce the desired behavior including social support,

economic rewards, and social norms

Campaign Evaluation

We evaluated the campaign with a pre and post written survey completed by a

convenience sample of parents and addressing assessment of community assets and

process measures. This study was approved by Seattle Children’s Institutional

Review Board.

6

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, Vol. 12, No. 3 [2020], Art. 4

https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare/vol12/iss3/4

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.12.03.04

The survey was anonymous, self-administered, available in Vietnamese or

English, and took approximately five minutes to complete. Fifteen questions were

developed based on content from the focus groups, translated into Vietnamese by a

professional translation service and checked with back translation to assure

accuracy. Questions and survey design were reviewed by Vietnamese community

members, leaders, and faculty experts from Seattle Children's Research Institute.

(See Appendix 1 for the survey.)

The survey was distributed to Vietnamese parents at Têt festivals,

Vietnamese language schools, Head Start, churches, temples, and community

centers in the Seattle area. Incentives included whistles for children of parents who

completed the surveys and a small stipend for language schools who coordinated

dissemination and collection of surveys. Pre-intervention surveys were conducted

between December 2006 and March 2007, post intervention surveys between

November 2007 and April 2008.

Demographic questions included sex and age of the parent, number and ages

of children in the household and primary language spoken at home. Three questions

addressed the key messages: “Had their child 1)... had swim lessons (ever or since

the previous June)?; 2)... swum in a lifeguarded area?; and 3)... worn a lifejacket?

To determine campaign exposure, questions included “Had they heard water safety

advice in the past 6 months? If so, where?” (Open-ended format).

We evaluated three community assets before and after the campaign and

again in 2019: number of Seattle and State Parks with lifeguards, number of parks

with translated lifejacket loaner boards (i.e. in Vietnamese as well as English), and

percent of Asian American lifeguards at Seattle Parks beaches and pools.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics and calculated frequency distributions. Statistical

analysis was performed using a Pearson's chi-square test, odds ratios (OR) and 95%

Confidence Intervals (CI). STATA version 11.0 was used to generate statistics and

perform the analysis.

Results

Survey Results

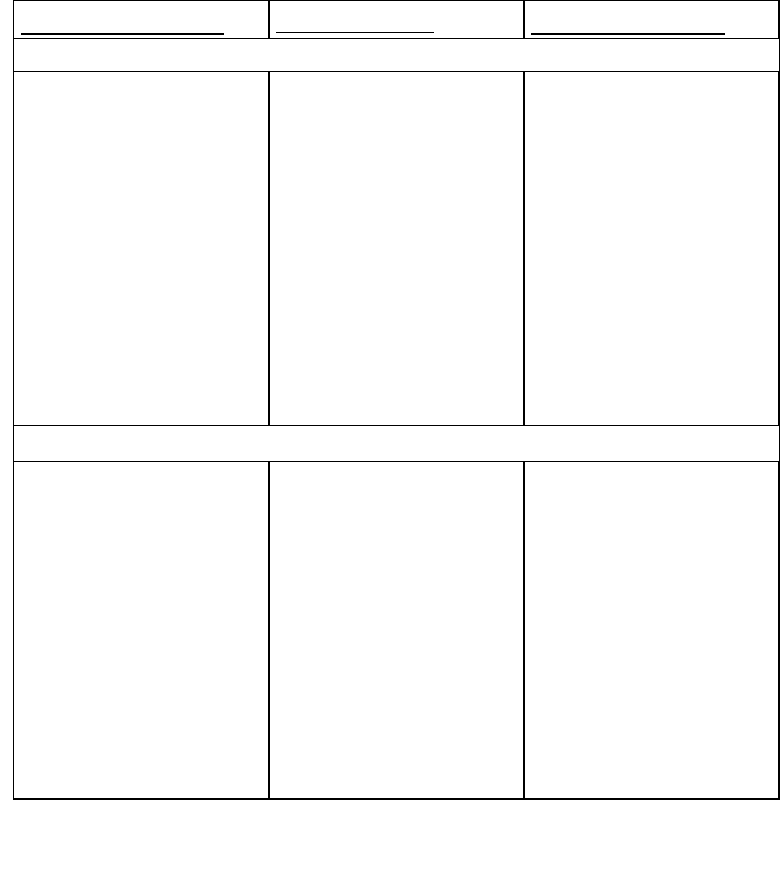

Pre- and post-intervention questionnaires were answered by 168 and 230

respondents, respectively, most of whom were female, had 1-8 children, and spoke

Vietnamese at home (see Table 2).

7

Quan et al.: Prevention Campaign for Vietnamese Americans

Published by ScholarWorks@BGSU, 2020

Table 2

Characteristics of surveyed parents

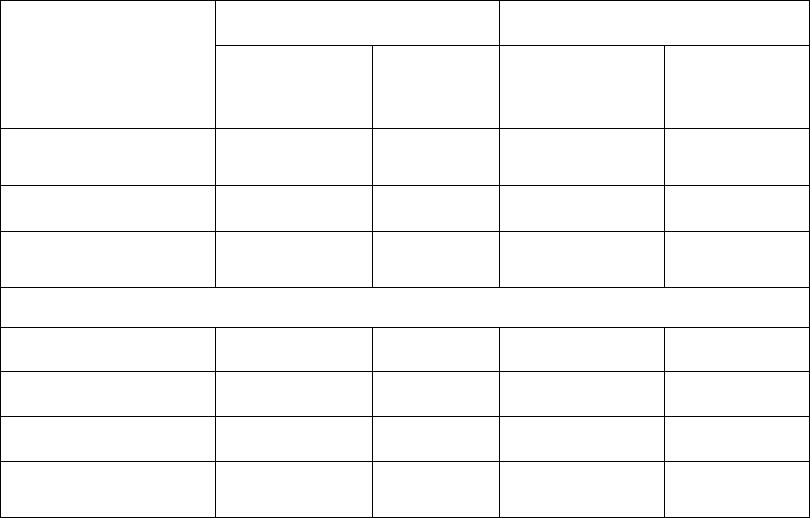

Compared to participants from the pre-intervention survey, parents

answering the post-intervention survey were significantly more likely to recall

having heard water safety advice in the prior year (84% vs 37%, OR 8.75 (95% CI

5.07,15.09), at local sites (40% vs. 0%), in the media (31% vs. 21%) or at schools

(8% vs. 2%). Additionally, they were more likely to report attending lifeguarded

sites at lakes/rivers (84% vs. 70%, OR 2.3 (95% CI 1.04,5.08). (See Table 3.)

Community assets results: Comparing 2006 to 2009, Asian Americans

comprised 10% (8/81) of lifeguards at Seattle beaches versus 7% (6/81) with one

Vietnamese; 11% (15/136) versus 17% (28/163) at Seattle Parks swimming pools,

five of whom were Vietnamese. These changes were not statistically significant.

However, in 2019, Asian Americans comprised 21.7% (74/341) of lifeguards at

Seattle parks; at one facility, 25.4% (14/55) were Vietnamese. The number of

lifeguarded Seattle Park sites has remained the same. King County Parks’

lifeguarded sites increased from zero to two but subsequently decreased to one. The

number of translated lifejacket loaner boards in Seattle has increased from one to

ten total.

Characteristics of

Surveyed Parents

PRE, Total N = 168

POST, Total N = 230

Mean (SD)

or

Percentage

Number

of

Responses

Mean (SD) or

Percentage

Number of

Responses

Mean Age in years

(SD)

41.1 (9.1)

123

42.7 (10.5)

196

Male

27%

45/166

38%

87/227

Mean Number of

Children (SD)

2.2 (1.1)

137

2.2 (1.1)

160

Language at home

Vietnamese only

57%

92

61%

137

English only

8%

13

10%

22

Vietnamese/English

35%

57

29%

67

Survey completed

in Vietnamese

46%

75/163

73%

170/230

8

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, Vol. 12, No. 3 [2020], Art. 4

https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare/vol12/iss3/4

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.12.03.04

Table 3

Results of parents’ pre and post intervention surveys

Survey

Question

PRE, Total N = 168

POST, Total N = 230

Percentage

Number

of

Responses

Percentage

Number

of

Responses

Odds Ratio

and 95%

Confidence

Intervals

Child wore a

life jacket at

lake or river

36%

27/74

50%

69/137

1.76

(0.98,3.11)

Ever enrolled

children in

swim lessons

52%

76/147

55%

120/219

1.13

(0.74,1.72)

Ensured

lifeguard

77%

72/93

67%

96/143

0.59

(0.33,1.08)

In Pool

In

River/Lake*

70%

42/60

84%

75/89

2.3

(1.04,5.08)

Saw/heard

water safety

information**

37%

48/129

84%

140/167

8.75

(5.07,15.09)

*p=.01, **p=.001

Discussion

This is one of few community drowning prevention programs evaluated, and the

first to focus on Vietnamese Americans (Bennett et al., 1999; Wallis et al., 2015;

Moran, 2017). High drowning rates and local experience with drownings of

Vietnamese American children prompted the development of a drowning

prevention campaign in the Vietnamese American community. Guided by an

evaluation of their reported beliefs and behaviors around water, the campaign used

a social marketing approach, linguistically and culturally tailored for this

community. To increase open water safety awareness, water skills of Vietnamese

youth (swimming lessons), and safe behaviors in both parents and children (use of

life jackets and life guarded sites), three campaign messages were delivered with

educational and experiential interventions. Pre- and post-intervention evaluations

9

Quan et al.: Prevention Campaign for Vietnamese Americans

Published by ScholarWorks@BGSU, 2020

showed the campaign increased community members’ awareness and significantly

increased their use of lifeguarded open water sites but not swimming lessons for

children or use of lifejackets. Importantly, community assets increased, including

numbers of available swim sessions, Asian lifeguards, and access to low cost swim

lessons and life jackets.

The reported increased use of lifeguarded sites at open water but not pools

may reflect that lifeguarded lake and river sites were lower cost and also preferred

over pools. The lack of swimming lessons may reflect the numerous barriers stated

by the focus groups, including cost, antipathy towards indoor pools and reluctance

for early initiation of swim lessons. (Quan et al., 2006). However, the free

swimming pool sessions for Vietnamese families generated interest amongst

families who were keen for their continuance. A focus on socially organized

sessions may be a way to encourage families from diverse communities to learn

skills.

Limitations

This study’s limitations were multiple. Different pre- and post-intervention groups

were convenience samples. However, the post-intervention group was larger, due

to our increasing access to the Vietnamese speaking community and differed only

in that respondents were more likely to complete the survey in Vietnamese. Our

written survey was biased toward literate groups. Parents’ reported behaviors were

not validated (Hatfield, et al., 2006). While observations would have been a

stronger study design, we were limited by the inability to determine specific Asian

type by observation. Parents surveyed may not have been representative of the

Vietnamese community; however, we surveyed parents at multiple community

venues based on community advisor recommendations. We attempted to survey a

control group in Portland, Oregon but could not find a community liaison in time

for the pre-intervention phase. Importantly, our methods and experience may not

be generalizable to non-Vietnamese Asian communities. Lastly, this campaign was

conducted ten years ago. However, a recent review of injury disparities research

between 2007 and 2017 showed few studies addressed prevention and very few

addressed Asian groups. It stated, “public health prevention campaigns to address

the disparity identified are urgently needed to fill the gaps.” (Moore et al., 2019).

Although higher rates of drowning amongst minority children are well

documented, they are poorly understood. (Gilchrist & Parker, 2014). Racial groups’

drowning risk varies by setting; the highest rates of nonfatal US drownings

typically occur in children of racial/ethnic minorities in natural waterways. (Felton

et al., 2015). The Vietnamese Americans’ drowning risks, absent recreational

swimming experience and water competence, have been similarly reported by

Asian New Zealand beachgoers; more Asian New Zealanders reported their

10

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, Vol. 12, No. 3 [2020], Art. 4

https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare/vol12/iss3/4

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.12.03.04

children had poor swim ability and saw themselves as high risk in five water

scenarios presented to them than non-Asians. (Stanley & Moran, 2017; Moran &

Wilcox, 2013). Moran concluded, “Immigrants are quickly adapting to the aquatic

lifestyle of their newly-adopted country but, these same immigrants may lack the

safety skills and knowledge to minimize the risk of harm” (Moran & Wilcox, 2013,

p.144).

Fear of drowning is an identified deterrent to recreational aquatic

involvement and an explanation for low swim skills among low income African

Americans (Pharr et al., 2018). Drowning fear was also reported by Asian New

Zealand students (Moran, 2010). The drownings of several local Vietnamese youth

could have contributed to Vietnamese American families’ avoidance of swim

lessons.

Additional risk contributors in low income and diverse neighborhoods

include lack of access to swimming pools and swim lessons and social exclusivity

(Hastings et al., 2006). Thus, we promoted swim lessons primarily in pool settings.

However, the antipathy towards unfamiliar, cold and expensive indoor pool settings

and preference for free open water sites reported by parents in focus groups, along

with this campaign’s failure to increase swim lesson participation, suggest the need

for other approaches. These might include a socially supportive experience and

swim/water safety sessions in open water.

Challenges reaching the Vietnamese community included identification of

Vietnamese community liaisons. Hatfield reported success in addressing this

inhibiting factor by using community health educators (Hatfield et al, 2006).

Implementation of the current campaign was time limited. Key elements to working

with the Vietnamese community identified in this study were language, community

liaisons and nontraditional venues for outreach, tailored messaging and emphasis

on family. Bilingual skills were critical to working with the community and its

leaders.

This campaign increased community assets for Vietnamese and other

diverse groups in the area. Several agencies made substantial policy and

programmatic changes, for example Head Start continues to provide water safety

education for its immigrant and refugee preschool families. Since exclusively

Vietnamese swim sessions required external funding sources after the campaign,

Seattle Parks and Recreation started low-cost family swim lessons for all parent

and school age child pairs. They now offer scholarship applications in Vietnamese.

Seattle Parks and Recreation has standardized their dissemination of key messages:

Learn to swim, Swim in a lifeguarded area, and Wear a lifejacket. Developing and

recruiting diverse youth as lifeguards and swim aids, they have doubled the

percentage of Asian lifeguards at their facilities. They continue to provide lifeguard

11

Quan et al.: Prevention Campaign for Vietnamese Americans

Published by ScholarWorks@BGSU, 2020

staffing at nine beach sites and have expanded free swim lessons at lifeguarded

beaches. They have also increased low cost lifejacket sales and numbers of life

jacket loan kiosks with standardized information in eight languages, including

Vietnamese. Head Start, Seattle Children's Hospital and several community groups

continue to provide water safety information and low cost lifejackets to families.

Conclusion

A unique community drowning prevention campaign for Vietnamese Americans

driven by local data and community focus groups addressed barriers and promoted

swimming lessons and water safe behaviors, including use of life guarded sites and

lifejackets. Evaluation showed the campaign increased drowning prevention

awareness and some safe behaviors, specifically use of lifeguarded sites.

Importantly, it improved community water safety assets such as access to swim

lessons, lifejackets and lifeguarded sites that continue a decade after for the entire

community.

References

Allen, M. L., Elliott, M. N., Morales, L. S., Diamant, A. L., Hambarsoomian, K.,

& Schuster, M. A. (2007). Adolescent participation in preventive health

behaviors, physical activity, and nutrition: differences across immigrant

generations for Asians and Latinos compared with Whites. American

Journal of Public Health, 97(2), 337-343.

https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2005.076810

Bennett, E., Cummings, P., Quan, L., & Lewis, F. M. (1999). Evaluation of a

drowning prevention campaign in King County, Washington. Injury

Prevention, 5(2), 109-113. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.5.2.109

Centers for Disease Control and National Center for Injury Prevention and

Control. Web-based Injury Surveillance Query and Reporting System.

(2019, December 19; 2020, January 12). CDC.

https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/

Felton, H., Myers, J., Liu, G., & Davis, D. W. (2015). Unintentional, non-fatal

drowning of children: US trends and racial/ethnic disparities. BMJ Open,

5(12), e008444. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008444

Gilchrist, J., & Parker, E. M. (2014). Racial and ethnic disparities in fatal

unintentional drowning among persons aged ≤ 29 years – United States,

1999–2010. Journal of Safety Research, 50 (September), 139-142.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2014.06.001

Green, L. W. & Kreuter, M.W. (2005). Health promotion planning: An educational

and environmental approach (4th ed). McGraw-Hill.

Hastings, D. W., Zahran, S., & Cable, S. (2006). Drowning in inequalities:

Swimming and social justice. Journal of Black Studies, 36(6), 894-917.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934705283903

12

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, Vol. 12, No. 3 [2020], Art. 4

https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare/vol12/iss3/4

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.12.03.04

Hatfield, P. M., Staresinic, A. G., Sorkness, C. A., Peterson, N. M., Schirmer, J., &

Katcher, M. L. (2006). Validating self-reported home safety practices in a

culturally diverse non-inner city population. Injury Prevention, 12(1), 52-

57. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.2005.009399

Kotler, P., Roberto, N., & Lee, N. (2002). Social Marketing: Improving Quality of

Life. Sage Publications.

Lefebvre, C., & Rochlin, L. (1997) Social Marketing. In K. Glanz, M. Lewis & B

Rimer (Eds.), Health Behavior and Health Education. (pp. 384-402).

Jossey-Bass Inc.

McCool, J. P., Moran, K., Ameratunga, S., & Robinson, E. (2008). New Zealand

beachgoers' swimming behaviours, swimming abilities, and perception of

drowning risk. International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education,

2(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.02.01.02

Moore, M., Conrick, K.M., Vavilala, M.S. (2019). Research on injury disparities:

a scoping review. Health Equity. 3:1, 504-511.

https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2019.0044

Moran, K. (2008). Rock-based fishers’ perceptions and practice of water

safety. International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, 2(2), 5.

https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.02.02.05

Moran, K. (2010). Risk of drowning: The “Iceberg Phenomenon" re-visited.

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, 4(2), 3.

https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.04.02.03

Moran, K. (2017). Rock-based fisher safety promotion: a decade on. International

Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, 10(2), 1.

https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.10.02.01

Moran, K., & Wilcox, S. (2013). Water safety practices and perceptions of “new"

New Zealanders. International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education,

7(2), 5. https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.07.02.05

Pharr, J., Irwin, C., Layne, T., & Irwin, R. (2018). Predictors of swimming ability

among children and adolescents in the United States. Sports, 6(1), 17.

https://doi.org/10.3390/sports6010017

Quan, L., Crispin, B., Bennett, E., & Gomez, A. (2006). Beliefs and practices to

prevent drowning among Vietnamese-American adolescents and parents.

Injury Prevention, 12(6), 427-429. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.2006.011486

Quan, L., Pilkey, D., Gomez, A., & Bennett, E. (2011). Analysis of paediatric

drowning deaths in Washington State using the child death review (CDR)

for surveillance: what CDR does and does not tell us about lethal

drowning injury. Injury Prevention, 17(Suppl I), i28-i33.

https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.2010.026849

Stanley, T., & Moran, K. (2017). Parental perceptions of water competence and

drowning risk for themselves and their children in an open water

13

Quan et al.: Prevention Campaign for Vietnamese Americans

Published by ScholarWorks@BGSU, 2020

environment. International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education,

10(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.10.01.04

U.S. Census Bureau (2010, July 02). The Vietnamese Population in the United

States: 2010.

http://www.vasummit2011.org/docs/research/The%20Vietnamese%20Pop

ulation%202010_July%202.2011.pdf

Wallis, B. A., Watt, K., Franklin, R. C., Taylor, M., Nixon, J. W., & Kimble, R. M.

(2015). Interventions associated with drowning prevention in children and

adolescents: systematic literature review. Injury Prevention, 21(3), 195-

204. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2014-041216

Washington State Department of Health. (2004). Child death review state

committee recommendations on child drowning prevention. Olympia,

Washington.

14

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, Vol. 12, No. 3 [2020], Art. 4

https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare/vol12/iss3/4

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.12.03.04

Appendix 1 Survey of Water Activities in the Vietnamese Community

(English version)

(Circle your answer)

1. What language do you mostly speak at home?

Vietnamese English Both

2. What is your age?

3. What is your gender?

4. Do you have children? Yes No

5. How many children?

6. What are the ages of your children?

The next questions are about one of your children between 5 and 16 years old

who played near or by the water this past summer.

7. Can he/she swim? Yes No

8. Has he/she ever taken swim lessons? Yes No

9. Since last June, has he/she ever taken swim lessons? Yes No

10. Since last June, did he/she visit a swimming pool? Yes No

11. If the answer was yes, did he/she get into the water? Yes No

12. Was a lifeguard present? Yes No

13. Since last June, did he/she visit a lake or river? Yes No

14. If the answer was yes, did he/she swim or wade? Yes No

15. If he went swimming or wading, who watched him/her when he was in the

water?

Another child An adult A lifeguard No one

16. Was a lifeguard nearby or present? Yes No

17. Did he/she use a lifejacket when in the water? Yes No

18. Do you know where you can borrow a lifejacket to wear at the beach?

Yes No

19. If yes, where would you go? (Please write in):

20. Would you attend a session about water safety at lakes and beaches?

Yes No

21. Did you hear any advice last summer about how to be safe around water?

Yes No

22. If yes, where did you hear it? (Please write)

23. If yes, what did you hear? (Please write)

24. Where would you prefer to get information on water safety? (Please write)

15

Quan et al.: Prevention Campaign for Vietnamese Americans

Published by ScholarWorks@BGSU, 2020