Focus on the Alternative School Calendar:

Year-Round School Programs and Update on the

Four-Day School Week

Asenith Dixon

In recent years, lean economic conditions have led to state and local agency budget cuts,

including reductions to elementary and secondary education. To compensate for less state funding

and decreasing local revenues, many state legislatures have passed policy and funding bills that

give school systems more latitude in making finance and program decisions. A key area where

more flexibility is apparent is the scheduling of school calendars. One of the first responses to the

downturn in the economy was to explore the four-day school week as a money-saving measure.

Statutes in nearly half of the 16 SREB states now permit local school districts to adopt calendars

where students attend school for longer but fewer days.

With renewed focus at the state and federal level on reforming education and increasing

student learning, state policy-makers also are looking for more creative ways to arrange the instruc-

tional school year. The concept of altering the traditional school calendar is not new, but few

schools and districts across the country have embraced the idea. Those that have chosen alternative

calendars typically have similar reasons, including raising student achievement, reducing the

achievement gap among groups of students, saving money, and decreasing school overcrowding.

In the SREB region, most schools and districts that operate on an alternative calendar use

either a year-round school program or a four-day school week, although year-round schedules are

more prevalent. Year-round school calendars reorganize minimum instructional time requirements

across the school year; reduce the time students spend on summer vacation; and provide multiple

opportunities for tutoring, remediation and enrichment throughout the school year.

This Focus report provides an overview of year-round programs and examines the advantages

and challenges that are inherent to most, if not all, of these programs. It also provides an update

on actions relating to the four-day school week. Although only a small percentage of schools in

the SREB region have year-round programs in operation, it is important for education leaders and

legislators to explore whether this type of calendar contributes to stronger academic achievement

results for students.

Instructional time requirements

The trend toward a uniform school calendar began in the 1850s with the passage of federal

child labor laws, the introduction of state compulsory attendance laws and increased industrializa-

tion nationally. These circumstances produced a common school calendar of about nine months

in school and three months of summer vacation. Today, the school calendar in most areas of the

country still resembles the calendar created more than a century ago.

Other reports on this topic in the SREB Focus series include Focus on the School Calendar (2010) and Focus

on the School Calendar: The Four-Day School Week (2008).

January 2011

Southern

Regional

Education

Board

592 10th St. N.W.

Atlanta, GA 30318

(404) 875-9211

www.sreb.org

C

HALLENGE

TO

L

EAD

2

Nationwide, public school systems customarily base their calendars on a state-mandated, minimum

amount of instructional time. Defined as the time in school that is dedicated to instruction, instructional

time is measured in days and/or hours, depending on the state. Schools must meet minimum instructional

time requirements whether the school operates on a traditional or an alternative calendar.

Seven SREB states (Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and West

Virginia) define the school year using a set number of instructional days only, ranging from 178 to 180

days. Two SREB states — Maryland and North Carolina — define the school year by both a minimum

number of instructional days and a minimum number of instructional hours. Florida, Georgia, Kentucky,

Louisiana, Oklahoma and Virginia define the school year by either a minimum number of instructional

days or a minimum number of hours. Delaware is the only SREB state that defines the school year in terms

of hours alone. (See Table 1.)

In general, state boards of education have the authority to waive minimum instructional time require-

ments, among other state education statutes, if a school or local school district applies for an exemption or

waiver. State boards may waive instructional time provisions for various reasons, which typically include a

school or school district: implementing innovative school programs or special programs; bypassing statutory

school opening and closing dates; or missing numerous days due to weather, health or emergency conditions.

Recent additions in instructional time flexibility

Over the last two years, four SREB states have made changes to state statutes regarding instructional

time requirements. Both Georgia and Oklahoma previously required schools to provide students with 180

instructional days. Georgia’s House Bill 193 (2009) now allows local districts to implement an alternative

calendar of 180 days or an equivalent number of hours as determined by the state Board of Education.

Rule 160-5-1-.02(2) of the state Board sets the equivalent number of hours by grade level. The minimum

number of instructional hours ranges from 810 hours in kindergarten through grade three, to 900 hours in

grades four and five, and 990 hours in grades six through 12. Oklahoma’s House Bill 1864 (2009) changed

the school year calculation to provide either a minimum of 1,080 hours of instruction or 180 days of

instruction.

In 2010, legislatures in North Carolina and Tennessee modified instructional time requirements in the

event of unique circumstances, including severe weather conditions, energy shortages, contagious disease

outbreaks and emergencies. North Carolina’s House Bill 636 allows a school that closes for one or more full

days due to inclement weather to satisfy instructional time requirements by being in session for 1,000 hours

of instructional time, even if those hours occur in less than 180 calendar days. Tennessee’s House Bill 3100

and Senate Bill 3031 allow school systems to extend the school day by one-half hour daily for the full

school year (totaling up to 13 additional instructional days each year) to meet instructional time require-

ments missed due to severe weather, serious outbreaks of illness, natural disasters and other dangerous con-

ditions. Upon the approval of the state commissioner of education, school systems may use excess instruc-

tional time for professional development, parent-teacher conferences and other meetings.

3

Also in 2010, Maryland passed legislation that encourages schools and school districts to operate alterna-

tive calendar programs as a way to improve instructional delivery. Both House Bill 439 and Senate Bill 542

require the state Board of Education to explore the use of innovative school scheduling models (including

extended-year and year-round calendars in low-performing or at-risk public schools) and encourage schools

to use those models.

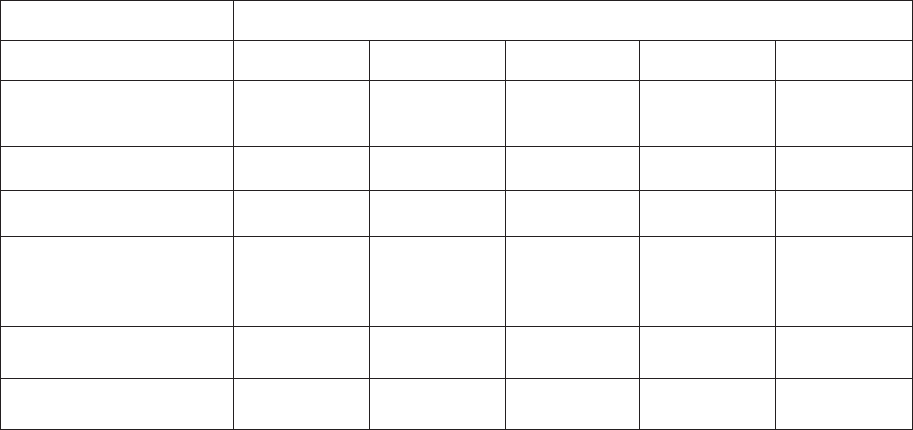

Table 1

Instructional Time Requirements in SREB States, 2010

* The General Assembly has budgeted funding to local districts for a minimum of 177 instructional days,

which equal 1,062 minimum hours of instruction.

Sources: Education Commission of the States, Market Retrieval Data Corporation, SREB state departments

of education, SREB state legislative and governors’ staffs, and state statutes.

Alabama 180

Kentucky 175* OR 1,050

Louisiana 177 OR 1,062

Maryland 180 AND 1,080

Mississippi 180

North Carolina 180 AND 1,000

Oklahoma 180 OR 1,080

South Carolina 180

Tennessee 180

Texas 180

Virginia 180 OR 990

West Virginia 180

Arkansas 178

Delaware 440 (K)

1,060 (1st-11th)

1,032 (12th)

Florida 180 OR 720 (K-3rd)

900 (4th-12th)

Georgia 180 OR 810 (K-3rd)

900 (4th-5th)

990 (6th-12th)

Days Per Year Hours Per Year

Most SREB states have some schools on alternative calendars

During the 2009-2010 school year, state departments of education in the SREB region reported that a

little more than 200 schools in 12 SREB states operated year-round programs. During the same school year,

just over 40 schools in five of those states — Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana and Oklahoma —

operated on four-day school weeks.

No schools in Alabama, Maryland, Mississippi and South Carolina operated either type of alternative

school calendar during the 2009-2010 school year.

Schools in 12 SREB states operate year-round programs

Year-round school calendars date back to 1904 when one school in Bluffton, Indiana, implemented a

four-quarter schedule to increase student achievement and school building capacity. Not long after, a few

schools across the country began to implement forms of a year-round schedule for reasons that included

remediating students and teaching English to immigrants. In many ways, the reasons given for beginning

year-round school calendar programs in schools a century ago are similar to those today.

By 2008, an estimated 7 percent of K-12 public schools nationwide (about 2,800) operated on year-

round schedules. Almost half of the schools were in California, with the remainder in 44 other states.

The estimated 206 public schools operating year-round schedules in 12 SREB states represented less than

1 percent of public schools in those states. (See Table 2.)

In general, a year-round calendar redistributes the number of instructional days more evenly across the

school year than a traditional calendar. (In fact, some year-round programs exceed minimum instructional

time requirements so that the school day, the school year — or both — may be longer than those in a tradi-

tional calendar.) Schools arrange the year into instructional terms with “intersessions,” or vacations, of two

or more weeks between terms. Schools can use intersessions as remediation and tutoring time for students

who have fallen behind and as enrichment periods for other students. The vacation break for year-round

school programs, normally from two to eight weeks, is shorter than the three-month summer vacation of

a traditional calendar.

Year-round calendars have one of two types of schedules: single-track or multi-track. Single-track is a

unified schedule in which all students and teachers attend school and take intersessions/vacations at the

same time. In comparison, multi-track arranges students and teachers into groups that attend school and

take intersessions/vacations on staggered schedules.

Single-track schedules

Numerous patterns for single-track schedules allow schools to meet or exceed minimum instructional

time requirements. The more prevalent patterns are: a 45-day instructional term, followed by a 10-day

intersession/vacation; a 45-day term and 15-day intersession/vacation; a 60-20 combination; or a 90-30.

4

5

For example, on a 45-10 schedule, students attend school for four 45-day instructional terms per year, with

10-day intersession/vacations. Those on a 60-20 schedule attend three instructional terms of 60 days, and

those on a 90-30 schedule have two 90-day instructional terms per year. The summer vacation is longer

than the intersessions but shorter than the traditional calendar’s three-month vacation. (See Table 3.)

Table 2

Estimated Number of K-12 Year-Round School Programs in SREB States,

2009-2010 School Year

1

The language in these code sections details year-round school statutes specifically.

2

Schools or school systems in these states may utilize education waiver provisions in state statutes or state

board of education regulations to implement a year-round school program.

3

Allows specific county boards of education and the Baltimore City Public Schools to operate a year-

round pilot study or program, provided the minimum instructional time requirements are met. Other

county boards of education may operate a year-round pilot study or program if funded by the local

county board.

Sources: SREB state departments of education and state statutes.

Alabama 0 None

2

Arkansas 9 §6-10-108

Florida 4 None

2

Georgia 5 §20-2-168(e)

Kentucky 27 §158.070(3)

Louisiana 7 §17:341

Maryland 0 §7-103(e)

3

Mississippi 0 None

2

North Carolina 104 None

2

Oklahoma 7 Title 70 §1-109.1

South Carolina 0 None

2

Tennessee 13 §49-6-3004(f)

Texas 17 §25.084

Virginia 9 §22.1-79.1(B)(3)

West Virginia 2 §18-5-45(r)

Delaware 2 Title 14 §1049A

Estimated Number Code Section

1

6

Multi-track schedules

Multi-track schedules organize students into groups that attend school on staggered instructional terms

with different intersessions/vacations. Each track, or group of students and teachers, in essence creates a

“school-within-a-school.” District or school leaders group students and teaching staff into three, four or five

tracks for the school year; at any one time, one group is always on vacation while the other groups are in

school. Hence, the seating capacity on multi-track schedules increases by varying percentages, depending

on the number of tracks utilized during the school year. (See Table 4.)

The three-track schedule, known as a “Concept 6 schedule,” breaks the student and teacher population

into three groups that attend school for about 170 instructional days a year. Students attend two instruc-

tional terms of about 80 to 85 days per year and have approximately 40-day intersessions/vacations. Schools

that use the three-track schedule may have to extend the school day to meet the state’s minimum instruc-

tional time requirements. Overall, the schedule can increase the school’s capacity by up to 50 percent.

The four-track schedule commonly uses a 45-15, a 60-20 or a 90-30 instructional term to interses-

sion/vacation ratio. On a 60-20 schedule, for example, students attend school for three 60-day terms per

year, with intersessions/vacations of 20 days. Students on a 45-15 schedule attend four 45-day instructional

terms separated by 15-day intersessions/vacations. Those on a 90-30 schedule attend school for two 90-day

terms, followed by 30 days of vacation or intersession activities. These schedules typically meet a state’s

minimum instructional time requirements, and the school’s seating capacity increases by no more than

33 percent.

Table 3

Single-Track Schedules

Sources: National Association for Year-Round Education and the California Department of Education.

Number of Instructional

Days

180 180 180 180 180

Length of Intersessions

(days)

3 days to

3 months

(summer)

10 15 20 30

Length of Terms (days) 45 to 90 45 45 60 90

Number of Terms 2 to 4 4 4 3 2

Number of Intersessions 4 4 4 3 2

Summer Vacation 3 months 5 weeks 5 weeks 5 weeks 4 weeks

60-20 90-3045-1545-10Traditional

Scheduling Patterns

7

The five-track schedule, called the “Orchard Plan,” uses a 60-15 ratio that increases a school’s capacity

by, at most, 25 percent. The 60-15 ratio allows up to 197 instructional days a year. The schedule permits

schools to schedule a common, three-week summer vacation for all students and staff, with additional

intersessions/vacations for each track during the school year.

A closer look at schools with year-round programs

Schools and districts in many SREB states have operated year-round school calendars for many years

and instituted the calendars for various reasons. For example, the Bardstown city school system in Kentucky

implemented a year-round calendar in 1995 with the intention of increasing student achievement and edu-

cational enrichment opportunities through innovative education programs. When the calendar was first insti-

tuted, all four schools — one elementary, one middle grades school, one high school and an early childhood

education center — moved from a traditional school calendar to a balanced 45-10, single-track schedule.

During the first five years of implementation, the district reported that the high school dropout rate

decreased from 4.5 percent to 2.7 percent, and the percentage of students from the senior class who attended

a postsecondary institution increased from 62 percent to 74 percent. In addition, disciplinary referrals

decreased while attendance increased. The school system continues to see positive results, including

decreased absenteeism and discipline referrals. The dropout rate remains around 2.5 percent.

Table 4

Multi-Track Schedules

Number of Instructional

Days

180 180 up to 197 180 180160 to 170

Capacity Change N/A Increase

by up

to 33%

Increase by

up to 25%

Increase

by up to

33%

Increase

by up

to 33%

Increase by up

to 50%

Length of Intersessions

(days)

3 days to

3 months

(summer)

15 Three 15-day

breaks and one

20-day break

20 30about 40

Length of Terms (days) 45 to 90 45 60 60 90about 80 to 85

Number of Terms 2 to 4 4 3 3 22

Number of Tracks 1 4 5 4 43

Number of Intersessions 4 4 4 3 22

Summer Vacation 12 weeks 5 weeks 3 weeks 5 weeks 4 weeks4 to 5 weeks

80/85-20

(Concept 6)

60-15

(Orchard Plan) 90-3060-2045-15Traditional

Scheduling Patterns

Sources: National Association for Year-Round Education and the California Department of Education.

8

In the SREB region, North Carolina has the most schools operating on year-round calendars (104) as

reported by the state department of education — about 4 percent of the state’s 2,500 public schools. Nearly

half are in Wake County. To accommodate rapid population growth and to maintain diversity, the Wake

County public school system began investigating year-round school programs in 1987 and launched a year-

round school pilot project in 1989.

The school system opened a 267-student magnet elementary school on a single-track, year-round calen-

dar, which was the state’s (and the nation’s) first magnet year-round school. The following year, the county

opened a multi-track, year-round elementary school for 750 students. Currently, Wake County operates

49 year-round schools, totaling about 20,000 students. These schools operate on a 45-15, four-track

schedule for 180 instructional days a year.

As a result, Wake County schools house 20 percent to 33 percent more students. The system saves on

construction costs, operating expenses and student materials. Instead of purchasing textbooks and equipment

for every student, schools save money by requiring students from different tracks to share textbooks and

school equipment (such as computers). In addition, the 15-day intersessions provide students with enrich-

ment and remedial programs.

After several years of operating a year-round schedule, Virginia’s Fairfax County school board eliminated

its multi-track, year-round program in May 2010 due to state funding decreases. The year-round calendar

had operated in 23 elementary schools and affected about 1,000 teachers, but the schools returned to a

traditional calendar in fall 2010. The school system will use $1.3 million in local funds to facilitate its tran-

sition back to a traditional calendar. However, the program change will save the school system more than

$1.9 million in local funding during the 2010-2011 school year alone.

In December 2010, the Oklahoma City school district voted to implement a year-round school calendar

in all 78 schools in the district. Before the district vote, seven schools in the district operated on a year-

round calendar to combat academic achievement losses. Due to a rise in student population, an increase

in the number of students eligible for the federal free- and reduced-priced meal program, and 17 schools

on the “needs improvement” list in the district, the board voted to expand the calendar to all schools in the

district to provide additional opportunities for learning. Beginning with the 2011-2012 school year, the

summer vacation will decrease to two months (from the current three months), and two- or three-week

intersessions will divide the school year. The number of instructional days will not change.

Benefits and challenges of year-round programs

The potential benefits and challenges of implementing a year-round school program are numerous.

Overall, the regular intersession/vacation breaks can give teachers and students time to rejuvenate, creating

more motivated and invigorated staff and students. In turn, multiple intersessions provide students with more

opportunities for remediation and enrichment, compared with the traditional calendar’s typical remediation

only during summer school. Other advantages can include salary enhancements for support staff and instruc-

tors who work extra terms, during intersessions, or as substitutes. Unfortunately, a year-round program also

can create difficulties for some families in planning extended family vacations, especially for siblings who may

not have the same school calendar. Child care options could be limited due to the unique breaks.

9

Generally, schools implement single-track or multi-track schedules for different reasons. Increasing

student achievement is the most frequent aim of the single-track schedule. The intent of the continuous

learning environment is to promote learning retention through remediation and enrichment — and decrease

the potential for summer learning loss with the shorter summer break. These characteristics may make

single-track schedules more beneficial to at-risk learners, such as students from low-income families and

English-as-a-second-language students.

In contrast, schools most often institute a multi-track schedule to lessen school overcrowding. In most

cases, a multi-track schedule expands a school’s seating capacity by 25 percent to 50 percent. Local school

districts do not bear the expense of constructing new school buildings or the increased operating expenses

associated with more and new school facilities.

Challenges to operating a multi-track schedule include transition costs due to administrative planning,

staff development, the need for storage space for teachers who share instructional space during the year, and

utility and maintenance expenses. Limited facility space and time in the schedule also can make scheduling

professional development classes, parent-teacher conferences, athletic activities and special events difficult.

Single-Track Schedule

Benefits

• Offers greater opportunity for increased student achievement

• Improves pace of instruction and learning through a continuous and balanced school year

• Helps school incorporate innovative education programs into the curriculum

• Decreases the effects of summer learning loss

• Provides more time for extra tutoring, remediation and enrichment activities throughout the year

• Offers opportunities for teacher and staff salary enhancements

• Can create more motivated teachers and students due to frequent intersessions/vacations

Challenges

• Does not accommodate large student population increases

• Students and teachers may desire a lengthier vacation or break from school

• Provides less time for extended family trips or vacations during summer

• Siblings may not have the same school calendar

• Child care options may be limited during the unique breaks

10

Year-round calendar considerations

As states renew their focus on raising student achievement during current budget challenges, many have

responded by providing flexibility to local districts, including the ability to reorganize the school calendar.

Districts have implemented alternative calendars for various reasons — most often to address student learn-

ing issues or overcrowding.

The overall impact of year-round school calendars versus traditional calendars is debatable, especially

when considering student achievement. In fact, concrete evidence does not exist to suggest that the

rearrangement of instructional time leads to greater student achievement. However, in many cases, when

a school moves to an alternative calendar, it implements other innovative education programs at the same

time. Hence, it is difficult to distinguish between the achievement results from the alternative calendar

program and those from any new education programs.

Multi-Track Schedule

Benefits

• Eases overcrowding problems

• Saves funds on building construction costs, operating expenses and materials

• Offers possibility of providing additional courses

• Decreases the effects of summer learning loss

• Provides more time for extra tutoring, remediation and enrichment activities throughout the

year

• Offers opportunities for teacher and staff salary enhancements

• Can create more motivated teachers and students due to frequent intersessions/vacations

Challenges

• Schools incur transition costs

• Increases utility and maintenance expenses

• Makes additional demands on administrative and support staff

• Requires teachers to share classrooms and requires extra storage space

• Creates difficulties in scheduling professional development

• Requires unique scheduling requirements for athletics, special events and conferences

• Students and teachers may desire a lengthier vacation or break from school

• Provides less time for extended family trips or vacations during summer

• Siblings may not have the same school calendar

• Child care options may be limited during the unique breaks

11

Yet researchers have found that as quality instructional time increases, the connection between the time

and student achievement strengthens. Moreover, the correlation grows even stronger as quality academic

learning time — the time that students are actually engaged in learning — increases. So the implementation

of a year-round calendar with increased quality instructional time in which students are actively engaged

in learning (an extended year-round school calendar) can have a positive effect on student achievement.

Furthermore, some researchers suggest that expanding the amount of instructional and academic learning

time for at-risk or low-income students may improve student learning and close achievement gaps between

those students and their peers.

Ultimately, time can be “an academic equalizer,” as stated in the 1994 Prisoners of Time report by the

National Education Commission on Time and Learning, but the potential for time to be a change agent

depends on how it is used and whether its use is serving students that are most in need of extra learning

opportunities. Schools and school districts must choose a school calendar that will better serve the needs

of their students while emphasizing efforts to boost student achievement.

Update on the four-day school week

The first public schools to implement a four-day school week were in South Dakota during the 1930s.

Recent implementation of the four-day school calendar came about in the early 1970s, primarily in response

to costs associated with the energy crisis. The four-day school week requires longer school days but fewer

overall days per school year for students.

In general, state statutes in most SREB states prohibit schools or districts from implementing a four-day

school week because of language that requires schools to meet minimum instructional day requirements.

However, as noted earlier, variations exist whereby school districts may petition state boards of education

for exemptions from instructional time requirements for special educational purposes, or in the event of a

national disaster, severe weather, a contagious disease outbreak or another type of emergency.

In 2009, the National School Boards Association estimated that approximately 100 public school dis-

tricts in 17 states nationwide were using a four-day school week, mainly in rural areas where students have

long distances to travel between home and school. Currently, seven SREB states allow schools to implement

four-day school weeks. In 2008, SREB published a Focus report on the four-day school week and at that

time, five SREB states — Arkansas, Delaware, Kentucky, Louisiana and Virginia — had provisions in state

statutes providing flexibility for schools or school districts to implement a four-day school week. In 2009,

Georgia and Oklahoma revised their statutes to permit more flexible schedules in which schools and districts

can meet instructional time requirements through either a minimum number of days or hours.

A few public schools in five of the seven states — Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana and

Oklahoma — operated on a four-day school week in the 2009-2010 school year, based on a recent survey

of state departments of education. Only a small percentage, at most 1 percent, of all public schools in these

five states utilized the four-day week. (See Table 5.)

12

A closer look at four-day programs in some SREB states

Districts implement four-day school week programs for various reasons. In many cases, schools and

school systems switch to the four-day program to save money. Both the Webster County school district in

Kentucky and the Peach County school system in Georgia switched to a four-day school week because of

state budget reductions.

State budget reductions during the 2002 school year and a projected state budget shortfall in the

2003 school year led Kentucky’s Webster County school system to approve a four-day school week in

2003. School system leaders believed the four-day school week offered them an opportunity to make budget

Table 5

Estimated Number of K-12 Four-Day School Week Programs in SREB States,

2009-2010 School Year

1

The language in these code sections authorizes the implementation of four-day school weeks specifically

or through statutes that provide hourly instructional time flexibility for schools and school systems.

Sources: SREB state departments of education and state statutes.

Alabama 0 None

Arkansas 3 §6-10-117

Florida 0 None

Georgia 6 §20-2-168(c)(1)

Kentucky 6 §158.070(1)

Louisiana 23 §17:154.1(A)(1)

Maryland 0 None

Mississippi 0 None

North Carolina 0 None

Oklahoma 5 Title 70 §1-109(E)

South Carolina 0 None

Tennessee 0 None

Texas 0 None

Virginia 0 §22.1-79.1(C)

West Virginia 0 None

Delaware 0 Title 14 §1049(a)(1)

Estimated Number Code Section

1

13

adjustments while maintaining the system’s level of academic and extracurricular programming. Webster

County schools are open from Tuesday through Friday, and teachers use Mondays for planning days, staff

meetings and professional development. Students in the school system receive at least 1,067 hours of instruc-

tional time (an average of 6.5 hours of instruction each day) during the school year, which is more than the

state minimum requirement of 1,050 instructional hours (six hours of instruction per day).

The implementation of the four-day school week in Webster County contributed to a decrease in

teacher and student absenteeism, improved student and teacher morale, reduced disciplinary infractions,

and some gains in student achievement. In 2008, Time magazine reported that from 2003 to 2008 the

school district moved up in state rankings from 111th to 53rd on standardized tests. The school district also

reported savings in teacher contract revisions, transportation expenses and operational costs, as well as a

decrease in the number of substitute teachers needed. On the other hand, many challenges arose as a result

of implementing this alternative calendar, including sustaining student achievement, child supervision out-

side of school hours, maintaining academic rigor throughout the entire school day, support staff morale and

parent buy-in.

In Georgia, the Peach County school district implemented a four-day school week (Tuesday through

Friday) in 2009 to manage state budget cuts. The change from a traditional calendar decreased transporta-

tion, cafeteria and operational expenses and allowed the school system to use the budget savings in other

areas. In spite of the budget reductions, the school system was able to save about 39 teacher positions.

As in Webster County, administrators in Peach County reported improvements in student achievement,

attendance and behavior.

In summary

In the midst of these lean budgetary times, many state legislators are providing schools and school

districts with more flexibility. Some schools and districts have used the opportunity to institute a four-day

school week program to decrease operating costs. Although the possibility of saving money is important, key

decision-makers must ensure that a calendar change fulfills their students’ needs and contributes to stronger

academic achievement results.

References

Alexander, Karl L., Doris R. Entwistle and Linda Steffel Olson. Lasting Consequences of the Summer Learning

Gap. American Sociological Review, Vol. 72, April 2007.

Bardstown City Schools’ Year Round Education Page.” Bardstown City Schools, Kentucky. Accessed at —

http://www.btown.k12.ky.us/yre/.

Blanton, Brooks. “Shorter School Weeks to Save Money.” Fox News, September 7, 2010. Accessed at —

http://liveshots.blogs.foxnews.com/2010/09/07/shorter-school-weeks-to-save-money/.

Calendar Comparisons. National Association of Year-Round Education, 2009. Accessed at —

http://www.nayre.org.

14

For more information, contact Asenith Dixon, State Services coordinator, at asenith.dixon@sreb.org; or Gale

Gaines, vice president, State Services, at gale.gaines@sreb.org. Both can be reached at (404) 875-9211.

(11S01)

Cooper, Harris. “Summer Learning Loss: the Problem and Some Solutions.” Educational Resources

Information Center (ERIC) Digest, May 2003.

Donis-Keller, Christine, and David L. Silvernail. Research Brief: A Review of the Evidence on the Four-Day

School Week. Center for Education Policy, Applied Research and Evaluation, University of Southern Maine,

February 2009.

Fairfax County Public Schools, FY 2011 Budget. Accessed at —

http://www.fcps.edu/fs/budget/documents/approved/2011/ApprovedBudget11.pdf.

Focus on the School Calendar. Southern Regional Education Board, April 2010.

Focus on the School Calendar: The Four-Day School Week. Southern Regional Education Board, August 2008.

Four-Day Week Report. Webster County Schools, Kentucky. Accessed at —

http://www.webster.k12.ky.us/4DayWeekReport/tabid/848/Default.aspx.

Johnson, Shaun P., and Terry E. Spradlin. Alternatives to the Traditional School-Year Calendar. Center for

Evaluation and Education Policy, 2007.

Kingsbury, Kathleen. “Four-Day School Weeks.” Time, August 14, 2008.

O’Brien, Eileen M. Making Time. Center for Public Education, 2006.

Palmer, Elisabeth A., and Amy E. Bemis. “Year-Round Education.” University of Minnesota’s Center for

Applied Research and Educational Improvement, November 1998.

Prisoners of Time. National Education Commission on Time and Learning, 1994.

Silva, Elena. On the Clock: Rethinking the Way Schools Use Time. Education Sector, January 2007.

Viadero, Debra. “Research Yields Clues on the Effects of Extra Time for Learning.” Education Week,

September 2008.

Year-Round Education Program Guide. California Department of Education. Accessed at —

http://www.cde.ca.gov/ls/fa/yr/guide.asp.

“Year-Round Fact Sheet.” Wake County Public School System. Accessed at —

http://www.wcpss.net/year-round.