Global Guidelines for Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) and Poliovirus Surveillance

1

GLOBAL GUIDELINES

for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance

in the context of poliovirus eradication

Pre-

publication

version

2

GLOBAL GUIDELINES

for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance

in the context of poliovirus eradication

HOLD for WHO copyright info

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

iv

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................................... v

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................. vi

ABOUT THESE GUIDELINES ............................................................................................................. vii

INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1

1. Poliovirus and poliomyelitis ................................................................................................................. 1

2. Polio eradication .................................................................................................................................. 2

3. Polio surveillance systems .................................................................................................................. 3

PRINCIPLES of AFP surveillance ........................................................................................................ 4

1. Adopting AFP as a reportable syndrome ............................................................................................ 4

2. Testing all stool specimens in a WHO-accredited polio laboratory .................................................... 5

STRATEGIES for AFP surveillance ..................................................................................................... 6

1. Routine (passive) surveillance ............................................................................................................ 6

2. Active surveillance............................................................................................................................... 7

3. Community-based surveillance ......................................................................................................... 13

4. Supplemental strategies for special populations .............................................................................. 15

CASE ACTIVITIES for AFP surveillance ........................................................................................... 18

1. Timely detection ................................................................................................................................ 19

2. Case notification and verification ...................................................................................................... 19

3. Case investigation and validation ..................................................................................................... 20

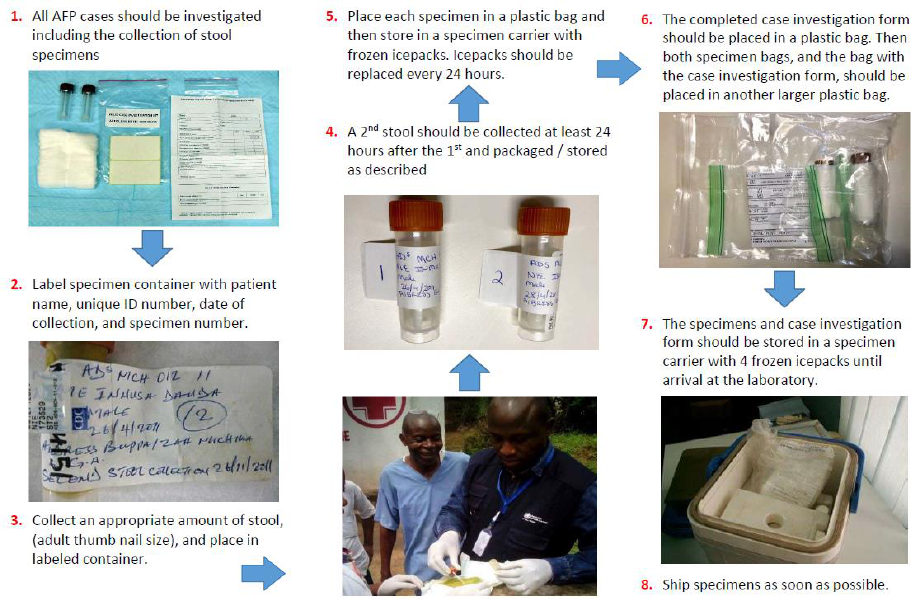

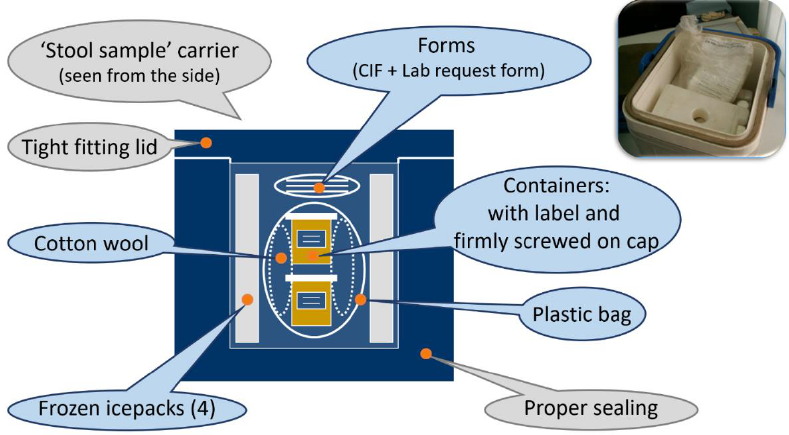

4. Stool collection and transport to the laboratory ................................................................................ 22

5. AFP contact sampling ....................................................................................................................... 24

6. Laboratory testing and reporting ....................................................................................................... 27

7. 60-day follow-up investigation ........................................................................................................... 30

8. Final AFP case classification ............................................................................................................ 31

MONITORING AFP surveillance ......................................................................................................... 34

1. Data management ............................................................................................................................. 34

2. Monitoring ......................................................................................................................................... 37

3. Evaluation ......................................................................................................................................... 41

SUSTAINING AFP surveillance .......................................................................................................... 42

1. Building a skilled workforce ............................................................................................................... 42

2. Integrating disease surveillance, the future of polio surveillance...................................................... 43

ANNEXES ............................................................................................................................................. 45

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This document reflects contributions from field, regional and global epidemiologists, laboratorians,

information system specialists and public health and gender experts in a process led by the agency

partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI): Rotary International, the World Health

Organization (WHO), the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Nations

Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

vi

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

AEFI Adverse event following immunization

AESI Adverse event of special interest

AFP Acute flaccid paralysis

AFR African Region (WHO)

AMR Region of the Americas (WHO)

AS Active surveillance

AVADAR Auto-Visual AFP Detection and Reporting

aVDPV Ambiguous vaccine-derived poliovirus

bOPV Bivalent oral polio vaccine

CBS Community-based surveillance

CIF Case investigation form

COVID-19 Coronavirus disease (2019)

cVDPV Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus

cVDPV1 Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1

cVDPV2 Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2

cVDPV3 Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 3

DG Director-general (WHO)

EI Essential immunization

EMG Electromyography

EMR Eastern Mediterranean Region (WHO)

EPID Epidemiological identification

ERC Expert Review Committee

ES Environmental surveillance

EUR European Region (WHO)

GACVS Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine

Safety

GBS Guillain-Barré syndrome

GCC Global Commission for the Certification of the

Eradication of Poliomyelitis

GIS Geographic information system

GPEI Global Polio Eradication Initiative

GPLN Global Polio Laboratory Network

GPS Global positioning system

IDP Internally displaced population

IPV Inactivated polio vaccine

ITD Intratypic differentiation

iVDPV Immunodeficiency-associated vaccine-

derived poliovirus

MOH Ministry of Health

mOPV Monovalent oral polio vaccine

mOPV1 Monovalent oral polio vaccine type 1

mOPV2 Monovalent oral polio vaccine type 2

mOPV3 Monovalent oral polio vaccine type 3

NCC National Certification Committee

NEC National Expert Committee

NGO Nongovernmental organization

nOPV Novel oral polio vaccine

nOPV2 Novel oral polio vaccine type 2

NPAFP Non-polio acute flaccid paralysis

NPEC National Polio Expert Committee

NPEV Non-polio enterovirus

OBRA Outbreak response assessment

OPV Oral polio vaccine

PID Primary immunodeficiency disorder

POLIS Polio Information System

RCC Regional Commission for the Certification of

the Eradication of Poliomyelitis

RNA Ribonucleic acid

SEAR South-East Asia Region (WHO)

SIA Supplementary immunization activity

SL Sabin-like

SOPs Standard operating procedures

tOPV Trivalent oral polio vaccine

TORs Terms of reference

VAPP Vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis

VDPV Vaccine-derived poliovirus

VDPV1 Vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1

VDPV2 Vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2

VDPV3 Vaccine-derived poliovirus type 3

VP1 Virus protein 1

VPD Vaccine-preventable disease

VRE Vaccine-related event

WebIFA Web-based information for action

WHO World Health Organization

WPR Western Pacific Region (WHO)

WPV Wild poliovirus

WPV1 Wild poliovirus type 1

WPV2 Wild poliovirus type 2

WPV3 Wild poliovirus type 3

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

vii

ABOUT THESE GUIDELINES

These Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis

(AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus

eradication are published to replace the 1996 revision

of the Field guide for supplementary activities aimed at

achieving polio eradication.

Since 1996, all regions of the World Health Organization

(WHO) and several polio-endemic countries have produced

their own AFP surveillance guidelines based on the Field guide,

which has served the programme well. These country-level

guidelines can be updated, if deemed necessary, based on

these new guidelines.

The new global guidelines outline well-established strategies

and activities for AFP surveillance to support countries in

attaining and maintaining a surveillance system sensitive

enough to detect the circulation of any polioviruses – wild polioviruses (WPVs), vaccine-derived

polioviruses (VDPVs) and Sabin-like (SL) viruses. The new guidelines also incorporate

recommendations made through a recent series of field guides and job aids that address current

surveillance-related challenges, and present new tools devised to enhance surveillance sensitivity and

increase the speed of detection of polioviruses. In addition, they introduce new indicators that

complement well-established certification standard indicators, such as those aimed at capturing the

timeliness of field activities. Overall, the guidelines stress four cross-cutting issues that remain central to

the success of the polio eradication programme: (1) the speed of poliovirus detection, (2) the quality of

surveillance at the subnational level, (3) the importance of gender equality to polio eradication, and

(4) the need for integrating polio with other vaccine-preventable disease (VPD) programmes.

These guidelines are intended for use by individuals and organizations involved in polio eradication

efforts that include: national polio surveillance and immunization programme managers and staff;

country, regional and global focal points for polio surveillance and immunization at the WHO and the

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); polio technical advisory bodies; and partners of the Global

Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI).

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

1

INTRODUCTION

Since its establishment in 1988, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) has made major progress

towards the goal of eradicating wild poliovirus (WPV). Five of six regions as defined by the World Health

Organization (WHO) have been certified as WPV-free: the Region of the Americas, the Western Pacific

Region, the European Region, the South-East Asian Region and the African Region. Of the three WPV

serotypes, the Global Commission for the Certification of the Eradication of Poliomyelitis (GCC) has

certified the global eradication of two serotypes: type 2 and type 3, last reported in 1999 and 2012,

respectively. At the time of this writing (October 2022), only WPV type 1 (WPV1) remains, with two

countries classified as endemic: Afghanistan and Pakistan.

1. Poliovirus and poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis is a highly contagious disease caused by a

human enterovirus called poliovirus. Poliovirus consists of

a ribonucleic acid (RNA) genome enclosed in a protein

shell, referred to as a capsid. Of the three serotypes of

poliovirus (types 1, 2, and 3), each have a slightly different

capsid protein. Immunity to one serotype does not confer

immunity to the other serotypes.

The virus is most often spread by the faecal-oral route through contact with the faeces of an infected

person, which occurs mostly in areas with poor water, sanitation and hygiene. It can also spread

through droplets from a sneeze or cough (oral-to-oral transmission), though this is less common and

occurs mainly in areas with relatively better hygiene and sanitary conditions. Poliovirus enters through

the mouth and multiplies in the intestine. Infected individuals shed poliovirus into the environment for

several weeks, where it can spread rapidly in the community, especially in areas of poor sanitation.

Poliovirus can interact with its host in two ways:

• Most poliovirus infections are asymptomatic or cause minor illness with mild symptoms without

affecting the central nervous system.

• Less than 1% of poliovirus infections result in paralysis by affecting the central nervous system,

a life-threatening disease called poliomyelitis.

Poliomyelitis cannot be cured but it can be prevented. Vaccination is safe, effective and inexpensive. It

is through the widespread use of the oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) that the polio eradication effort owes

its success. Unfortunately, in rare circumstances (approximately 1 in 2.7 million doses),

1

the attenuated

Sabin strains in OPV cause vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP) in the vaccine recipient or

a close contact.

In addition, in rare occasions through prolonged excretion or transmission, the vaccine virus can

genetically mutate to a form known as vaccine-derived

poliovirus (VDPV), which like WPV reflects the three

serotypes targeted by vaccines. There are three categories

of VDPVs: circulating, immunodeficiency-associated and

ambiguous. VDPVs represent a challenge to polio

eradication and are a focus of the programme in the last

mile to eradication.

2

1

See the fact sheet on types of polioviruses and vaccines, published on the GPEI website (https://polioeradication.org/wp-

content/uploads/2018/07/GPEI-cVDPV-Fact-Sheet-20191115.pdf).

2

For more on VDPVs, the GPEI website offers a short explanatory video (https://polioeradication.org/polio-today/polio-

prevention/the-virus/vaccine-derived-polio-viruses).

Annex guidance

This section provides a high-level

overview on poliovirus. Further details

can be found in Annex 1. Poliovirus.

Annex guidance

For more information on VDPVs, see

Annex 2. Vaccine-derived poliovirus

classification and response.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

2

2. Polio eradication

Following the widespread use of the poliovirus vaccine in the mid-20

th

century, the worldwide incidence

of poliomyelitis declined rapidly. In 1988, the World Health Assembly adopted the goal of global polio

eradication.

The benefits of the global eradication of polio are at least threefold:

1. Reduction in morbidity and mortality: Polio is a leading cause of disability in populations not

immunized against it. With the eradication of WPV types 2 and 3 (WPV2 and WPV3), the

incidences of infection caused by these two agents have already been reduced to zero, in

addition to preventing millions of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

2. Strengthened health systems: The polio eradication programme has enhanced the

collaboration between the surveillance systems and laboratory networks. It has helped

revitalize immunization programmes and it contributes to the strengthening of health system

planning, management and evaluation.

3. Economic impact: It is estimated that US$1.5 billion will be saved per year after the final

remaining serotype (WPV1) is eradicated and immunization against it stopped.

Polio can be eradicated because of the following characteristics:

• poliovirus has no animal reservoir;

• poliovirus survives for a limited amount of time in the environment; and

• inexpensive and effective vaccines exist to protect the population from the disease.

More than 200 countries and territories have eliminated polio through time-tested strategies by:

• attaining high essential immunization coverage (>90%) with at least three (3) doses of polio

vaccine within the first year of life;

• conducting high-quality supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) to stop outbreaks and

interrupt the spread of the virus; and

• implementing a sensitive surveillance system for poliovirus.

The following criteria will be applied for certification of WPV eradication:

3

• no WPV transmission detected from any population source for a period of no less than two (2)

years,

• adequate global poliovirus surveillance; and

• safe and secure containment of all WPVs retained in facilities, such as laboratories and vaccine

manufacturing facilities.

Global polio-free certification will be further sustained by requirements for containment of all

polioviruses and the cessation of OPV immunization to mitigate the risk of re-emergence over time.

4

3

Global Commission for the Certification of the Eradication of Poliomyelitis (GCC). Report from the 22nd meeting of the Global

Commission for Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication, 28-29 June 2022. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022

(https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/22nd-GCC-report-20220907.pdf).

4

For more on sustaining a polio-free world after the certification of global eradication, see: Global Polio Eradication Initiative

(GPEI). Polio Post-Certification Strategy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (http://polioeradication.org/wp-

content/uploads/2018/04/polio-post-certification-strategy-20180424-2.pdf). Revision in development.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

3

3. Polio surveillance systems

Different types of surveillance systems for detecting the transmission of poliovirus are critical to reach

global polio eradication, as high-quality surveillance permits the timely detection of poliovirus

transmission due to WPV, VDPVs and the circulation of Sabin-like (SL) viruses.

5

1. Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance: This globally accepted case-based syndromic

surveillance for AFP cases confirms poliovirus by testing stool specimens in polio laboratories.

AFP surveillance remains one of the cornerstones of the polio eradication effort.

2. Environmental surveillance (ES): AFP surveillance is complemented by environmental

surveillance (ES) which systematically tests sewage samples for poliovirus in specific settings.

6

3. Immunodeficiency-associated vaccine-derived poliovirus (iVDPV) surveillance: AFP

surveillance is also complemented by surveillance for iVDPVs among patients with primary

immunodeficiency disorders (PIDs), which is referred to as iVDPV surveillance.

7

These three components of polio surveillance are supported by the Global Polio Laboratory Network

(GPLN) for confirmatory testing using viral isolation, intratypic differentiation and genomic sequencing

procedures. Ready access to data from various sources that include AFP surveillance, ES, and

laboratory surveillance are supported by a comprehensive polio information system (POLIS).

Challenges to AFP surveillance in the last mile to eradication

Challenges faced by the polio eradication programme have evolved over the years. Currently, the

main challenges that affect the quality and sensitivity of AFP surveillance are attributable to a

range of factors.

• Many countries face gaps in AFP surveillance at subnational levels, especially where

surveillance coverage may be limited for reasons such as an inability to routinely access

special populations or hard-to-reach areas.

• Delays in specimen or sample shipment to WHO-accredited laboratories can result in late

confirmation of polio cases and consequent delayed outbreak response, thereby giving

poliovirus ample opportunity to spread.

• Missed opportunities for action due to the underutilization of surveillance data can create gaps

where the virus can spread before detection and response.

• Attrition, rapid staff turnover and insufficient refresher trainings affect the quality of field and

laboratory surveillance work through the loss of institutional memory, skills and competencies.

Churn within surveillance teams also affects supervision and monitoring.

• A deprioritization of polio activities and deterioration of surveillance quality and sensitivity in

countries that have been polio-free for years creates delays in detecting importations or

emergences of poliovirus, which in turn affects the promptness and effectiveness of outbreak

response.

• Across all countries, the COVID-19 pandemic (caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus) has also

negatively affected the sensitivity and timeliness of the AFP surveillance and laboratory

systems, even as the polio surveillance network itself lent crucial support to help contain

COVID-19, demonstrating it can go beyond polio surveillance to track vaccine-preventable

diseases (VPDs), emerging diseases, outbreaks or other major health events.*

*See Contributions of the polio network to the COVID-19 response: turning the challenge into an opportunity for polio transition.

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/contributions-of-the-polio-network-to-the-covid-

19-response-turning-the-challenge-into-an-opportunity-for-polio-transition).

5

Some countries also use enterovirus surveillance for the purpose of certification.

6

World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for environmental surveillance of poliovirus circulation. Geneva: World Health

Organization; 2003 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67854).

7

Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Guidelines for Implementing Poliovirus Surveillance among Patients with Primary

Immunodeficiency Disorders (PIDs), revised 2022. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 (https://polioeradication.org/wp-

content/uploads/2022/06/Guidelines-for-Implementing-PID-Suveillance_EN.pdf).

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

4

PRINCIPLES of AFP surveillance

Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance is a case-based syndromic surveillance system that has been

standardized throughout the world. The same tools, indicators and reporting systems are used in every

country. This standardized system has strengthened collaboration with immunization partners by

sharing uniform data on a weekly basis and advocating for action and support where risks and

weaknesses emerge.

A surveillance system that is specific to poliovirus is important because the characteristics of the

disease make it particularly challenging to detect:

• Only 1 in 200 wild poliovirus (WPV) infections of non-immune people results in paralysis. The

great majority of poliovirus infections are therefore “silent” as they do not cause paralysis.

• Even if a poliovirus infection causes paralysis, the clinical presentation of paralytic polio is

similar to that of other conditions, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS).

To overcome these challenges, two key measures were universally agreed to in the 1980s to improve

the sensitivity of the surveillance system:

1. adopting the syndrome of AFP as a reportable condition, and

2. laboratory confirmation of poliovirus by testing stool specimens in polio laboratories accredited

by the World Health Organization (WHO).

1. Adopting AFP as a reportable syndrome

When the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was first established, most countries were reporting

clinically confirmed polio cases. Polio was reported as just one of many diseases within disease

surveillance systems, often on an annual basis. Given the epidemiology and characteristics of polio, this

made it difficult to detect new cases and respond to outbreaks of polio both swiftly and effectively.

Many diseases may initially look like polio. A more sensitive

system was therefore needed to enable suspected new cases

to be detected, reported and investigated as rapidly as possible.

This led to the adoption of acute flaccid paralysis or

AFP as the syndrome to be reported.

8

This sensitive case-based syndromic definition captures not

only acute poliomyelitis but also other diseases that present

similarly, including GBS, transverse myelitis and traumatic

neuritis, such that each case must be investigated with

laboratory tests to confirm their causes. (Annex 1. Poliovirus

offers differential diagnoses and the clinical signs and symptoms which are used to differentiate

poliomyelitis from other diseases: asymmetric flaccid paralysis, fever at onset, rapid progression of

paralysis, residual paralysis after 60 days and preservation of sensory nerve function).

The rate of non-polio AFP case detection is a key indicator of AFP surveillance sensitivity. In the

absence of polio circulation, a sensitive surveillance system will detect at least one (1) case of non-polio

AFP each year for every 100 000 children under 15 years. Where polio is present or where polio is a

threat, this target is modified. The objective is then to detect at least two (2) cases of non-polio AFP

each year for every 100 000 children under 15 years in all at-risk and outbreak countries, and to detect

at least three (3) cases of non-polio AFP each year for every 100 000 children under 15 years in

endemic countries and outbreak-affected areas. (See Annex 3. Indicators for AFP surveillance.)

8

In the same way, smallpox eradication adopted detection and investigation of the “rash and fever” syndrome.

Defining AFP

An AFP case is defined as a child

under 15 years presenting with

sudden onset of floppy paralysis or

muscle weakness due to any

cause, or any person of any age

with paralytic illness if poliomyelitis

is suspected by a clinician.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

5

2. Testing all stool specimens in a WHO-accredited polio laboratory

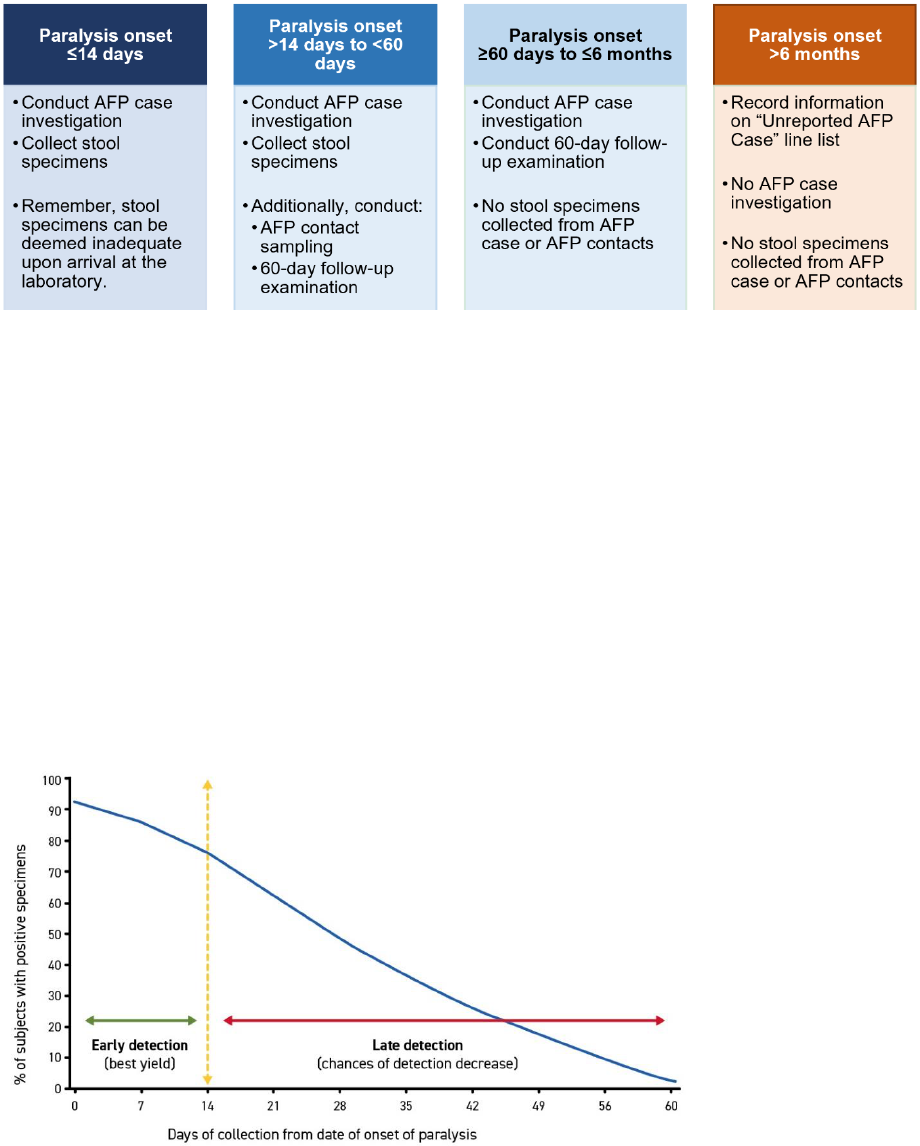

Polioviruses are primarily transmitted from person-to-person through the faecal-oral route in settings

with poor water, sanitation and hygiene. They replicate in the human intestinal system, where they are

shed intermittently in the stool of infected individuals. Shedding is most intense up to two weeks after

the onset of paralysis but can continue up

to six to eight weeks after onset.

Collecting two (2) stool specimens,

24 hours apart from each AFP case and

within 14 days of the onset of paralysis,

and then testing them in a WHO-

accredited polio laboratory is the most

reliable way to confirm the presence or

absence of poliovirus in the specimen and

thus to confirm poliovirus infection.

One of the universally accepted indications

that an AFP surveillance system is

sensitive enough to detect poliovirus is

that at least 80% of reported AFP cases

have had their stool specimens collected

adequately. The percentage of AFP cases

with adequate stools is used as the

second key indicator of AFP surveillance

sensitivity. (See Annex 3. Indicators for

AFP surveillance.)

Gold standard indicators for AFP surveillance

Non-polio AFP rate

✓ At least one (1) non-polio AFP case each year for

every 100 000 children aged under 15 years.

✓ In endemic countries and outbreak-affected areas,

at least three (3) non-polio AFP cases each year

for every 100 000 children under 15 years.

✓ In at-risk and outbreak countries, at least two (2)

non-polio AFP cases each year for every 100 000

children under 15 years.

Adequate stool specimen rate

✓ At least 80% of reported AFP cases have had

their stool specimens collected adequately.

See Annex 3 for core and non-core

AFP surveillance indicators.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

6

STRATEGIES for AFP surveillance

Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) cases are detected using three main strategies: routine (or passive)

surveillance, active surveillance (AS), and community-based surveillance (CBS).

9

Some supplemental

strategies for special populations and particular contexts also support overall AFP surveillance.

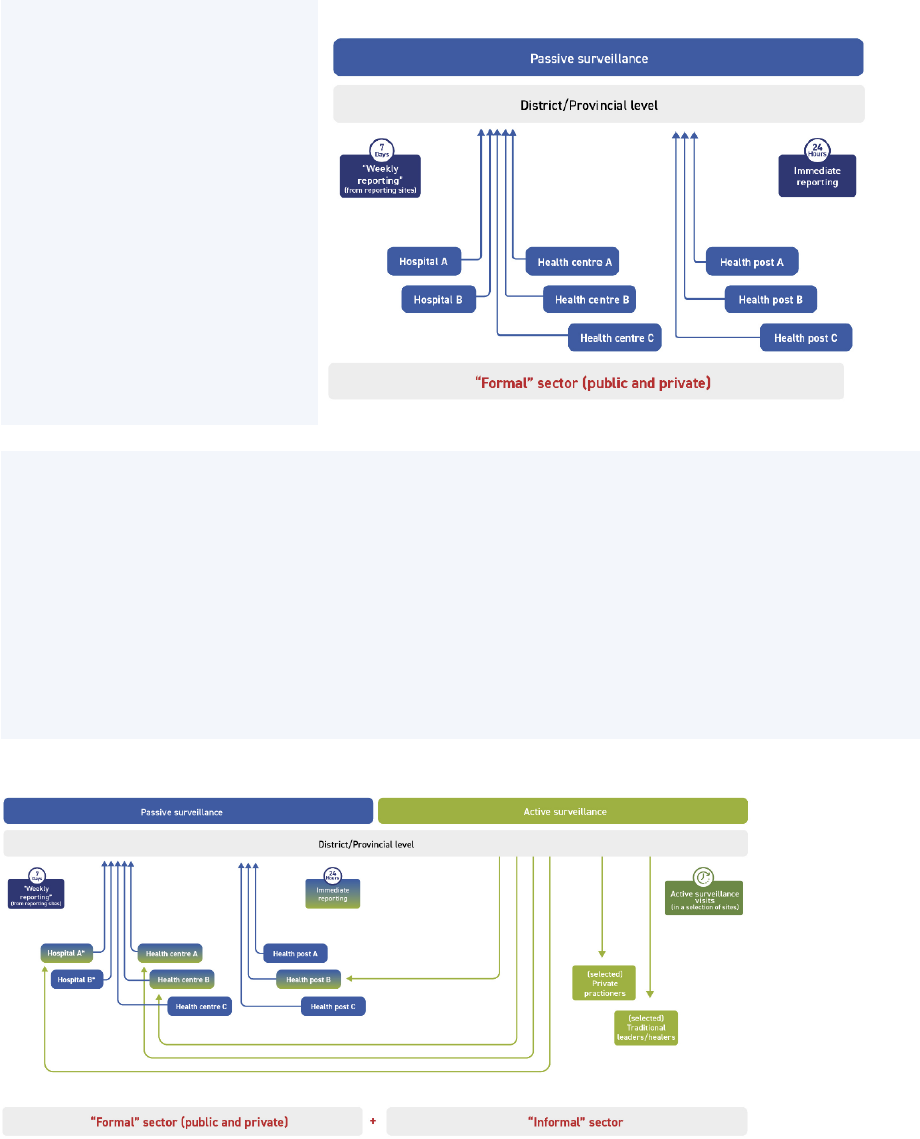

1. Routine (passive) surveillance

1.1 – What is routine (passive) surveillance?

The regular reporting of diseases or conditions of interest from reporting sites, such as health facilities

and hospitals, is called routine surveillance. It is sometimes referred to as passive surveillance because

public health authorities must rely on thousands of designated focal points from a variety of reporting

sites to detect and notify (or report) cases. It is also sometimes referred to as zero reporting as

reporting sites must report weekly, even

if no case has been detected.

In a majority of countries, routine AFP

surveillance is conducted as part of an

existing overall notifiable disease

reporting system that collects reports on

cases of a group of diseases or

conditions.

1.2 – AFP as a notifiable condition

Under routine surveillance, focal points at reporting sites are required to immediately report any AFP

case (i.e., within 24 hours) to a designated public health surveillance team for rapid investigation.

In addition to the immediate notification, surveillance focal points at reporting sites must also submit a

routine weekly or monthly report that must include “zero” ("0") if no AFP cases were seen in their site,

hence zero reporting. AFP is a rare condition, and a zero report is an important way to keep reporting

sites sensitized about the need to routinely conduct AFP surveillance.

1.3 – Monitoring routine surveillance

All countries are required to monitor the completeness and timeliness of routine AFP reporting, which

allows for the timely detection of gaps in reporting and surveillance quality. For most countries,

monitoring routine surveillance will be the same as the completeness and timeliness of notifiable

diseases reporting, as AFP is included among the list of notifiable diseases. These reports are also

submitted to and regularly scrutinized by National Certification Committees (NCCs) and Regional

Certification Commissions for the Eradication of Poliomyelitis (RCCs).

The indicators to monitor routine surveillance for AFP at the national and subnational level are:

• the percentage of designated sites submitting weekly reports (or “zero reports”), even in the

absence of cases, for a given time period (completeness); and

• the percentage of designated sites submitting weekly reports (or “zero reports”) on time, even in

the absence of cases, by the deadline (timeliness).

Surveillance teams should use this data to identify and follow up on reporting sites repeatedly failing to

report or reporting late. (See Annex 3. Indicators).

9

The PH101 Series by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides an introduction to public health

surveillance (https://www.cdc.gov/training/publichealth101/surveillance.html). See also Losos JZ. Routine and sentinel

surveillance models. East. Mediterr. Health. J 1996;2(1):46-50 (http://www.emro.who.int/emhj-volume-2-1996/volume-2-issue-

1/article6.html).

Defining routine surveillance

Also called passive surveillance or zero reporting, routine

surveillance is a process in which reporting sites are

expected to send reports to public health authorities

regularly and often weekly, regardless of whether an AFP

case has been seen.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

7

1.4 – Challenges with routine surveillance

The following challenges can be encountered with routine surveillance.

● Incomplete reporting networks may lead to delays in detection when the network is not

comprehensive enough (i.e., no sites in certain parts of the country).

● Incomplete weekly reports may occur when sites do not report as required, and the field team

has limited capacity either to follow up with “silent” reporting sites or to conduct training and

sensitization activities for all reporting sites. In these cases, active surveillance (below) provides

opportunities to strengthen routine surveillance through visits with site focal points.

● Attrition among personnel at the reporting site may lead to a lack of awareness of AFP as a

notifiable condition and a subsequent failure to identify and immediately report AFP cases.

● Declining awareness about polio and AFP reporting requirements may also create

confusion. Providers may forget the importance of reporting AFP as a syndrome as separate

and distinct from reporting polio as a diagnosis.

● Confusion between routine and active surveillance may lead to insufficient engagement of

both the formal and informal health sector. Under routine surveillance, district and provincial

surveillance teams rely on formal health sector sites to report on AFP cases; under active

surveillance, however, district and provincial

surveillance teams are actively engaged in finding

AFP cases by visiting health sites on a regular basis.

(In some settings, inquiries about AFP cases within a

routine reporting site made by the site-level focal point

are mistakenly considered “active surveillance.” Such

inquiries must be made by personnel external to the

facility to be considered active surveillance.)

2. Active surveillance

2.1 – What is active surveillance (AS)?

In countries and areas where people may not have access to health facilities, well-implemented active

surveillance (AS) has proven to be the most effective strategy for AFP surveillance.

Under AS, trained public health surveillance

staff regularly visit priority reporting sites

within the formal health sector (such as

tertiary hospitals and district hospitals) and

informal health sector (such as community

health centres run by nongovernmental

organizations [NGOs]) to identify and

investigate any unreported AFP cases and to

regularly sensitize targeted staff on polio and

AFP surveillance. To be effective, AS visits

must be done by well-qualified staff who

understand the polio eradication programme

and have good interpersonal skills.

Experience has shown that some countries have effectively used AS for AFP as

a platform for surveillance for vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) or other

outbreak-prone diseases.

Download Best Practices in Active Surveillance for Polio Eradication.

Annex guidance

For more on the differences between

routine and active surveillance, see

Annex 4. Routine and active

surveillance.

Defining active surveillance

AS is a process in which designated surveillance staff

make regular visits to the health facility; Surveillance

staff are external to the health facility. They collect

data from individual cases, registers, medical records

or logbooks at a health facility or reporting site to

ensure that no AFP case is missed.

For more on the difference between active and routine

surveillance, see Annex 4.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

8

2.2 – Setting up active surveillance

The key components of setting up an AS network are: (1) selecting, prioritizing, reviewing and updating

sites, (2) identifying focal points and building skilled surveillance staff capacity to carry out AS activities,

and (3) following a structured procedure to ensure high-quality visits.

2.2.1 – Site selection, prioritization, and updating

Selection: AS sites are drawn from the formal health sector and are a subset of the routine reporting

sites; however, they may also include some components of the informal health sector, such as

traditional health healers. In certain contexts, NGO-run facilities can also be included in the AS network,

such as where health facilities are set up in camps for refugees or internally displaced populations

(IDPs).

An analysis of where AFP reports originate will

show that the majority of children with AFP are

detected at and reported from a relatively small

number of reporting sites that are medium to

large hospitals, often referred to as secondary

or tertiary hospitals. The rationale behind this

trend is that, when faced with a health

emergency such as the sudden onset of

paralysis in a child, parents and caregivers are more likely to go to the largest accessible hospital,

bypassing local health centres and smaller hospitals.

Therefore, the primary criteria for selecting AS sites should be:

• the probability that children under 15 years of age with AFP are seen at the facility.

Additionally, AS sites should also be selected to ensure:

• the AS network is demographically and geographically well-distributed and representative of the

population in a province or district; and

• facilities within the network represent all sectors of the health system, from public and private

hospitals, to clinics and health centres, to pharmacies and even traditional healers, religious

leaders or other local community resources.

The informal health sector plays an important role, especially in locations where it represents the first

point of contact for families and communities to seek health care or advice. Informal health workers,

such as traditional medicine practitioners and faith healers who are likely to see AFP cases but do not

work within the formal health system are thus identified and sensitized to the importance of AFP and

oriented on its detection. They are then asked to contact surveillance staff upon encountering a

suspected AFP case.

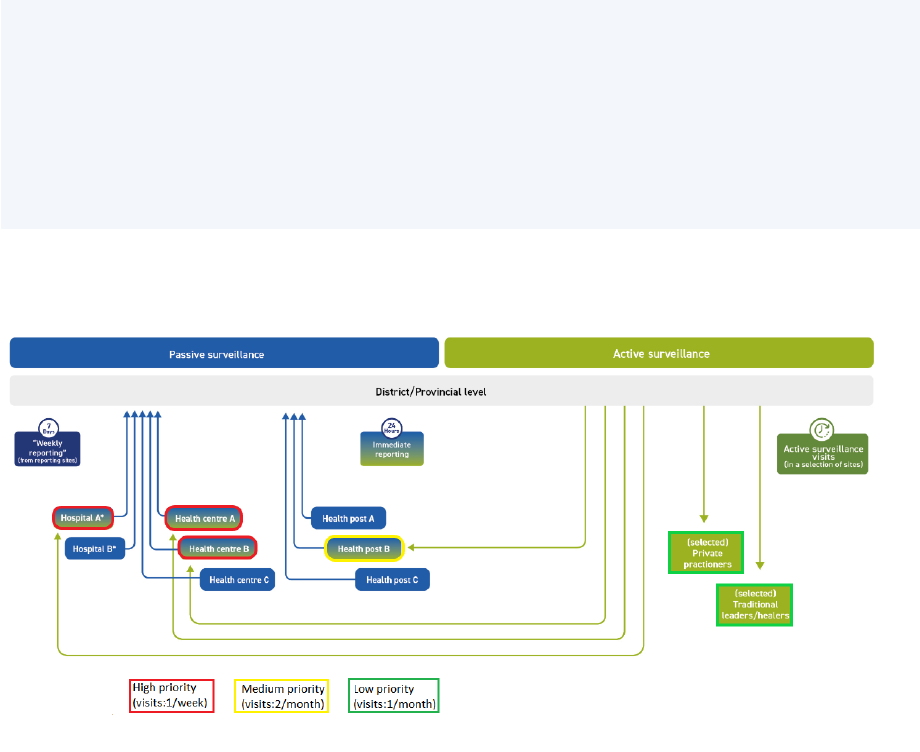

Prioritization: Once all AS sites are selected, a prioritization scheme of high-, medium-, and low-

priority sites must be applied to determine the frequency with which district and provincial surveillance

staff will conduct AS visits (Table 1). The frequency of site visits depends on the priority of the facility.

The highest priority should be given to those sites that see the most AFP cases, typically larger health

facilities and hospitals. Countries experiencing an outbreak may consider adding a fourth category

(“very high-priority sites”) under which targeted facilities are visited twice weekly. Annex 5 details

processes and procedures for AS surveillance visits.

Selecting active surveillance sites

The primary criteria for selecting health facilities for

the AS network is the probability that children under

15 years of age with AFP are seen at the facility.

AS networks include reporting sites from the formal

and the informal health sector.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

9

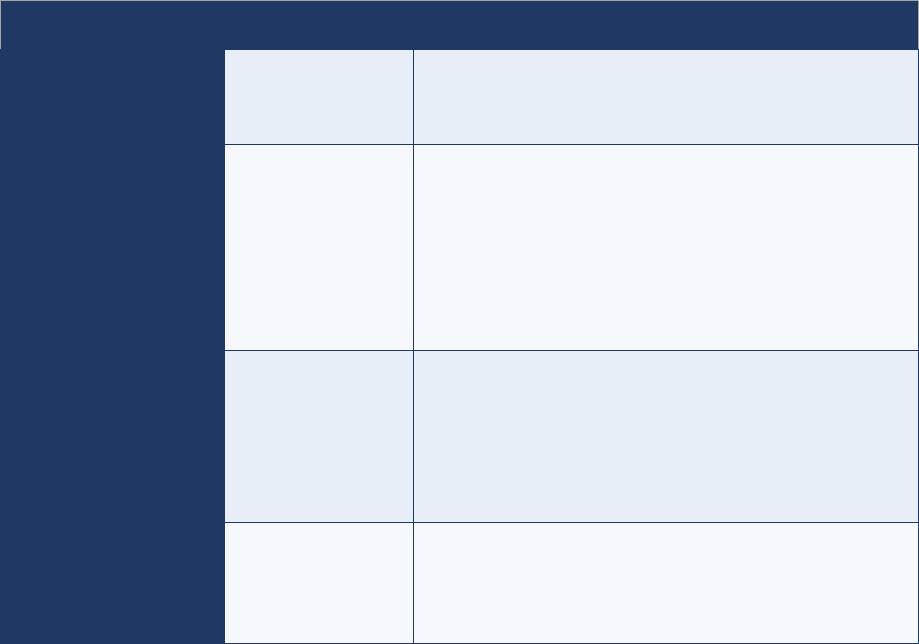

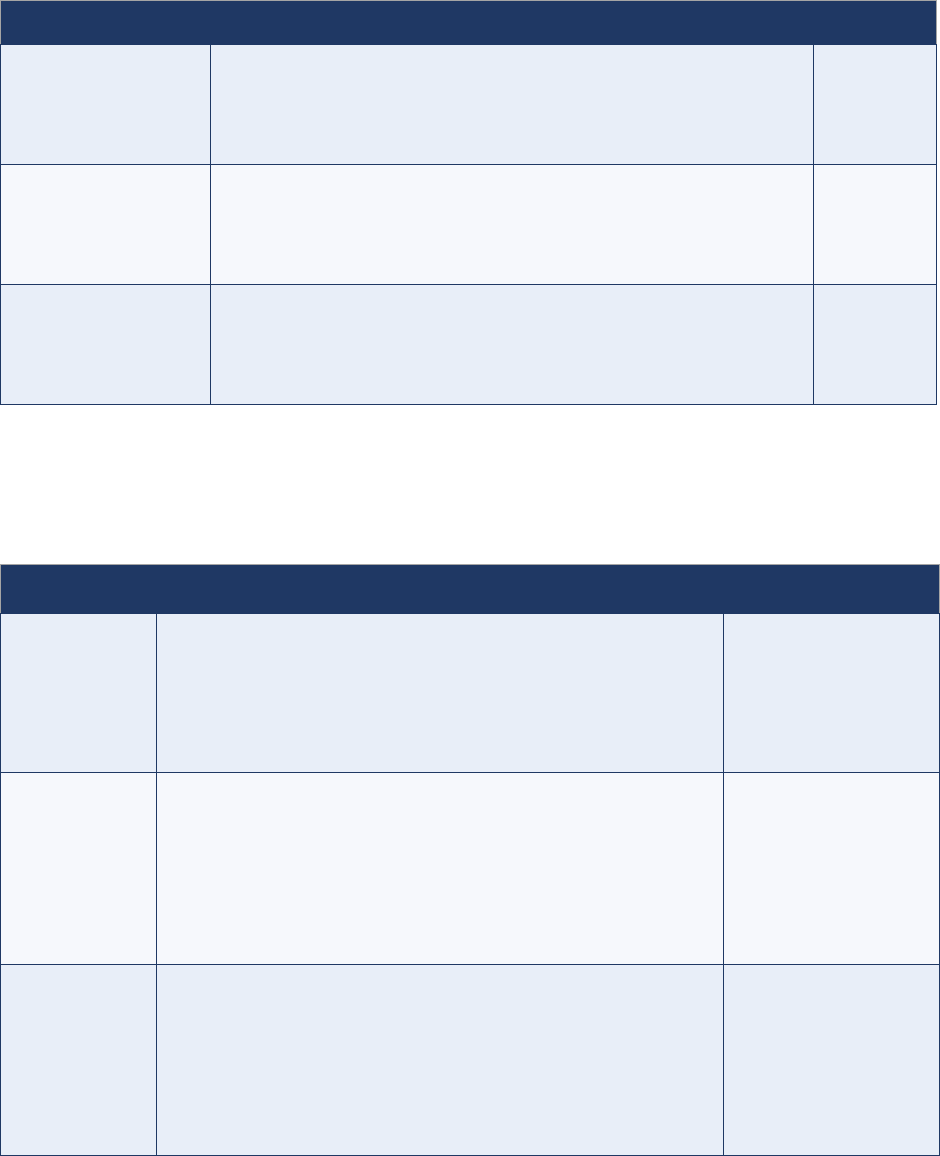

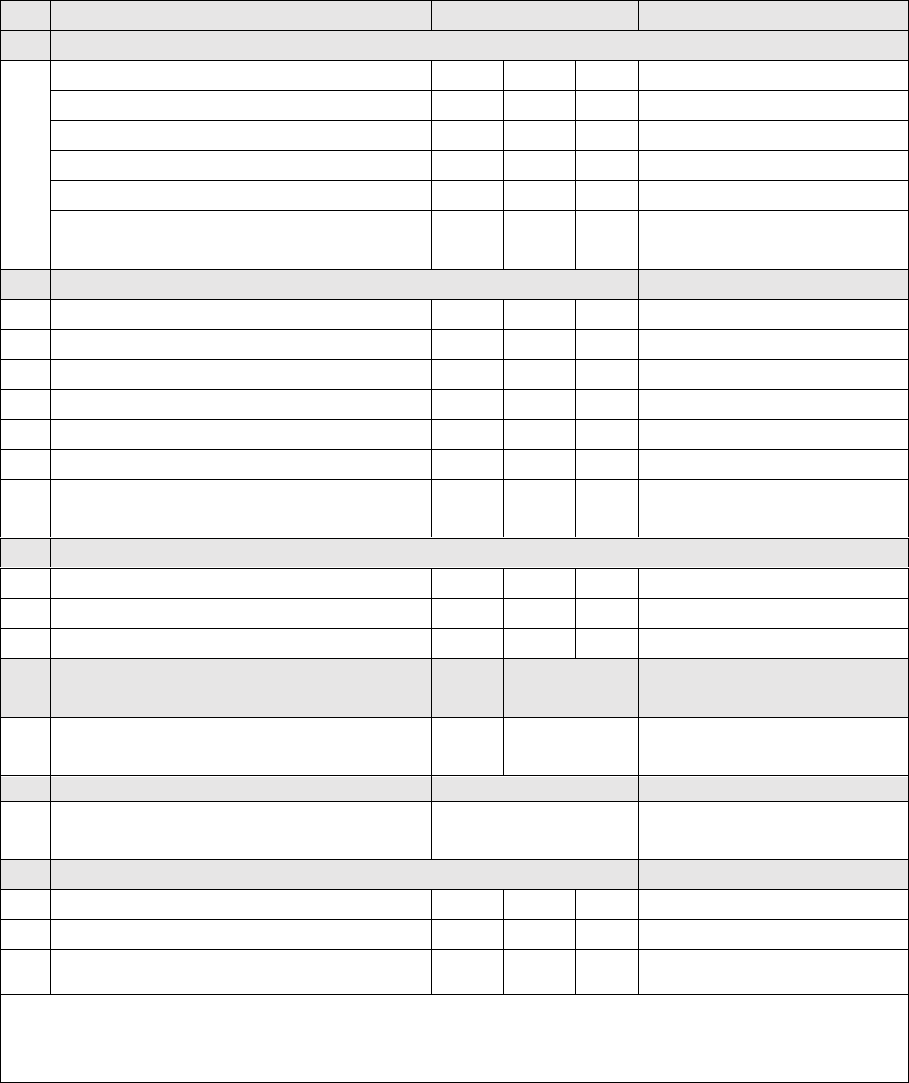

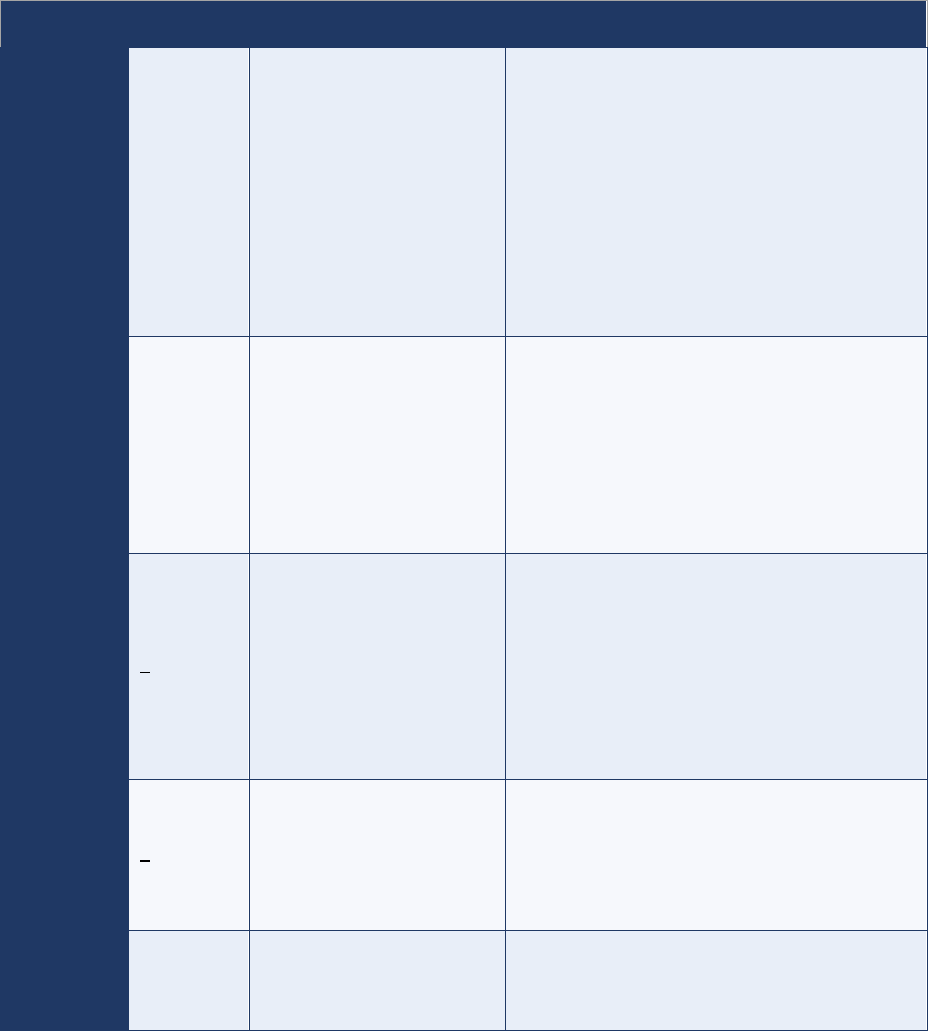

Table 1. Site prioritization scheme

Classification

Frequency of site visits

Very high-

priority sites

Very large national referral hospitals (in countries

experiencing an outbreak)

Visited twice weekly

High-priority

sites

Very large national referral hospitals (in some countries)

Visited more than once a week

All tertiary and secondary public and private hospitals

and all hospitals with paediatric departments

Visited weekly

Medium-

priority sites

Medium-sized hospitals, smaller hospitals and large

health centres (in some countries)

Traditional healers renowned for treating paralysis (in

certain communities)

Visited every two weeks

Low-priority

sites

Health posts, small health facilities, traditional healers,

pharmacies that could see an AFP case

Visited monthly

Not prioritized

Not part of the AS network, but part of the routine

surveillance network

No AS visits for AFP surveillance

AFP = acute flaccid paralysis; AS = active surveillance

Experience in polio-endemic countries has shown that, provided the prioritization

exercise is executed appropriately, the number of sites in the high-priority group

should be lowest (10–15% of the total number of AS sites), with more in the medium-

priority group (25–35%), and the remainder of sites in the low-priority group.

Updating the AS network: National, provincial and district surveillance teams should review the AS

network twice per year and make adjustments, as needed. Facilities may have closed, or new facilities

opened. In many countries, the private health sector is growing rapidly, and new facilities may be

predominantly in the private sector. Sites should be dropped from or added to the network accordingly.

Adjusting the AS site network is especially important in conflict settings, as conflict and insecurity may

disrupt the healthcare system. In such cases, public health surveillance teams need to respond by

updating and possibly expanding the AS network in those parts of the country around inaccessible

areas and in host communities receiving IDPs

or refugees, based on their health-seeking

behaviour. Where people no longer have

regular access to health facilities, surveillance

activities should be expanded to include direct

reporting from affected communities by

including IDP and refugee camps or NGOs

that provide health services (see also

Community-based surveillance and Annex 6).

2.2.2 – Site focal points and surveillance officers

Depending on a country’s size, district, provincial or national surveillance health officers will be

responsible for organizing and scheduling regular AS visits to reporting sites in their area.

In each AS site, a suitable AFP surveillance focal point must be identified or designated if not already in

place. While different groups may be considered for this function, depending on the size of the health

facility, priority should always be given to a paediatrician, if available.

Reviewing and adjusting sites

The AS network must be reviewed and updated twice

a year to account for the opening and closing of

health facilities, as well as sociodemographic

changes to the population.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

10

The AS focal point has several key roles and responsibilities that include:

• immediately notifying an identified AFP case and providing case investigation support;

• coordinating with public health staff during AS visits; and

• confirming zero reporting for routine (passive) surveillance for formal health facilities.

In the informal health sector, such as facilities held by traditional healers or private pharmacies, the

focal point by default will be the service provider, whose responsibility will be to notify immediately any

new AFP case. These establishments are typically not part of the routine surveillance system, hence

are not expected to provide reports.

2.2.3 – Site visit procedures

At the district or provincial level, public health surveillance officers will coordinate to conduct AS visits

according to the site visit calendar and prioritization scheme (Table 1 above).

Key activities for site visits

1. Meet with the facility AFP surveillance focal point to ask

whether any AFP cases were seen and provide

surveillance and polio eradication updates.

2. Visit all relevant departments and wards and review

patient registers.

• Look for missed or unreported AFP cases since the

date of the last visit. Look for “AFP” or associated

signs, symptoms, or diagnostics (Table 2). Because

AFP surveillance is a syndromic-based surveillance, it

is important to review symptoms, not diagnoses.

• Highlight directly in the register (with a coloured marker, if possible) and crosscheck the line

listing of all AFP cases (or possible AFP cases) which were found in the register.

• Date and sign all patient registers that were reviewed.

3. Follow up on any unreported AFP cases.

• If AFP cases were already reported and investigations launched, no further action is needed.

• If AFP cases were not reported, request medical records to search for details. Visit patients in

the hospital if still admitted; if discharged, obtain addresses to visit patients at home. If the

suspected case is confirmed as AFP, conduct the AFP case investigation and initiate specimen

collection (see Case investigation and validation under Case activities for AFP

surveillance, as well as Annex 8). In addition, speak to the physician or nursing staff to inquire

why the case was not reported and sensitize them to report such cases immediately. Conduct

follow-up visits to ensure that no additional AFP cases are missed and that all relevant staff has

been sensitized.

4. In addition, assess the overall status of polio-related functions during the visit.

• Take opportunities to sensitize department and ward staff on polio and AFP surveillance.

• Determine whether and when a training session may be needed, such as after staff turnover.

Experience has shown that, particularly in larger university hospitals, AS is more

efficient when performed by senior staff who have experience working with clinicians.

They can be shadowed by junior staff, who will in turn learn to build rapport with

clinicians and eventually conduct AS visits independently.

Annex guidance

Surveillance officers should always

follow standard procedures to

structure AS visits. See Annex 5.

Active surveillance visits and

Annex 7 for an example of an AS

visit form to support data collection

and monitoring.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

11

• Ensure sufficient supplies and resources are available, including forms, stool kits, and posters.

• Check immunization-related equipment and supplies, such as vaccines (oral polio vaccines

[OPVs] and/or inactivated polio vaccine [IPV]) and cold chain storage and carriers.

• Check into other VPD surveillance functions alongside AFP surveillance. As the integration of

AFP surveillance into VPD surveillance progresses, it is important to take advantage of AS

visits and search for and collect data on other VPDs or outbreak-prone diseases.

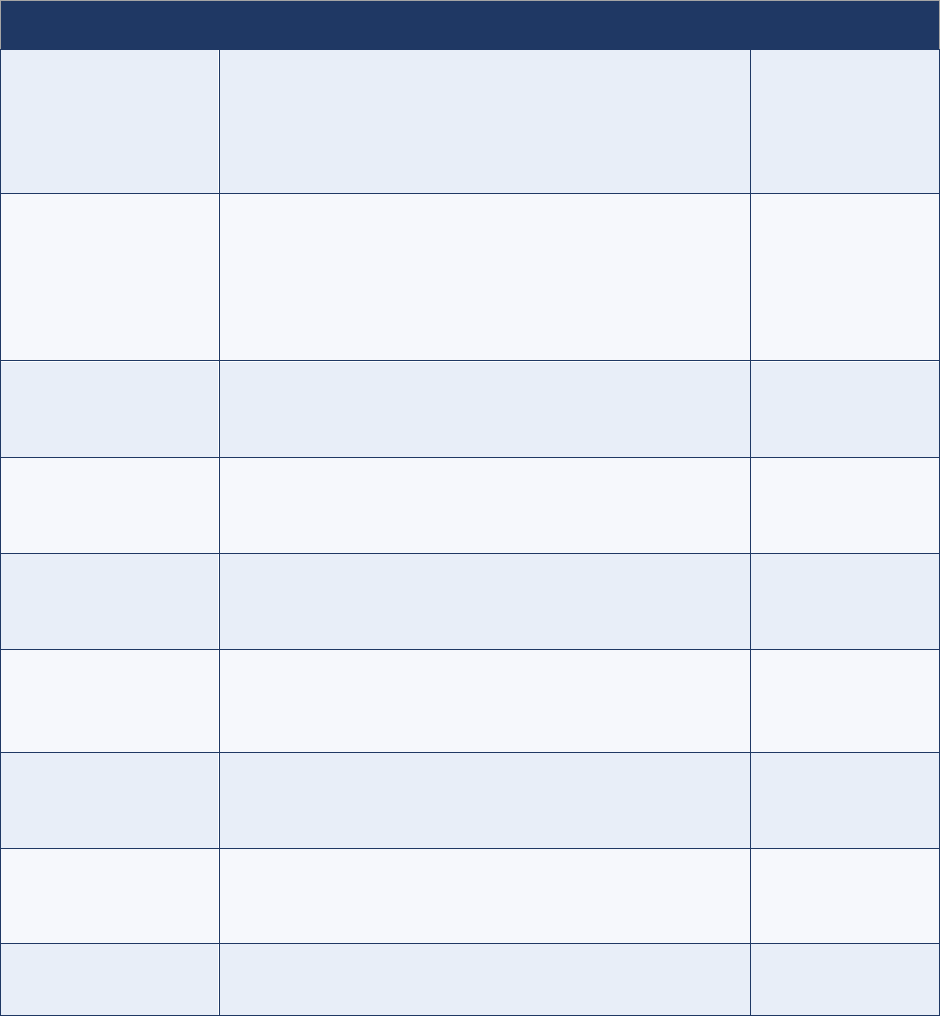

Table 2. Possible indications of an AFP case in patient registers

Disease conditions always

presenting as AFP

● Paralytic polio

● Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS)

● Transverse myelitis

● Traumatic neuritis

Disease conditions which may

initially present with AFP

● Pott’s disease (spinal tuberculosis)

● Bacterial or tuberculous meningitis

● Encephalitis

● Cerebrovascular accidents (stroke)

● Hemiplegia

Other signs and history to be

considered suspicious, indicating

that AFP may have been present

initially

● Frequent falls

● Weakness, paresis

● Abnormal gait, unable to walk, difficulty in walking

● Easy fatigability

AFP = acute flaccid paralysis; GPS = Guillain-Barré syndrome

2.3 – Monitoring active surveillance

The completeness and adequacy of AS visits must be monitored at the district, provincial and national

level. For a list of indicators used to monitor AS, see Annex 3. Indicators for AFP surveillance.

Monitoring is best accomplished by using a form that is completed by the visiting surveillance officer

and submitted after each visit to a supervisor at the provincial level. Annex 7. Examples of forms

offers a sample AS visit report. The form collects key data on all AS visits: the date, time and location,

facility visited, and a list of departments visited within large hospitals, as well as whether an undetected

AFP case was found during the visit, whether any AFP sensitization or orientation activities were

conducted, and whether supplies were provided to the facility (e.g., stool collection kits or posters).

Monitoring AS visits via mobile data and visualizing the analysed data can help

identify blind spots in the surveillance network and accelerate corrective actions.

See Monitoring AFP surveillance for more innovations in disease surveillance.

2.4 – Challenges with active surveillance

As public health teams implement AS, several challenges may arise.

Insufficient resources: After establishing the reporting network, surveillance teams often report

insufficient resources (such as not enough time, qualified staff, or means of transportation) to conduct

visits to all AS sites in the network.

• If this issue occurs, it is very important to ensure that at least all high-priority sites are visited

regularly, followed by as many medium- and low-priority sites as possible. This should be

feasible as a majority of high-priority sites (e.g., large hospitals) are in national or provincial

capitals and relatively close to the national or provincial surveillance office.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

12

• For facilities that cannot be visited, facility focal points should be contacted regularly by phone

or email, in addition to monitoring routine reports from these sites.

• Lists of sites and a calendar of visits should be reviewed or re-adjusted regularly until more

resources are made available.

Lack of attention to capital cities: AFP quality indicators from national capitals and the capital regions

of many countries tend to be surprisingly low. This is difficult to account for, as these areas usually host

large university hospitals and tertiary care facilities and large numbers of AFP cases are seen in these

areas, including cases referred from the provinces. Sensitive AFP surveillance at this level is more

important than anywhere else in the country.

• Large hospitals and high-priority tertiary care should be mapped and enrolled as reporting sites,

with subsequent AS visits planned and conducted on a regular and frequent basis.

• Visits must be conducted by surveillance officers who are trained and experienced in

sensitization and who are comfortable with medical personnel. These visits should be

accompanied by supportive supervision and monitoring for timeliness and completeness.

Inexperienced staff conducting AS visits: To successfully use AS visits for continuous sensitization

of clinicians and other hospital workers on AFP surveillance concept and practices, public health

officers must be trained on establishing rapport with medical staff, including with the chiefs of units,

some of whom may still not accept or fully understand syndromic AFP surveillance.

• Country programmes should commit to building junior staff capacity through supportive

supervision. Good mentoring and training ensure staff are well-qualified and equipped with

strong interpersonal communication skills.

• Particular attention should be given to female public health officers who may encounter gender

barriers while interacting with medical and hospital administrative staff.

Lack of access at private hospitals and facilities: AS visits can be challenging in private, military or

other sector-specific facilities. Surveillance officers should be aware of this and may need support from

higher-level officials to renegotiate access at regular intervals.

Insufficient geographic and demographic coverage or representativeness: The AS network may

possess geographic or demographic blind spots. Surveillance teams should be vigilant to identify:

• overlooked population groups that live in remote or hard-to-reach areas;

• overlooked mobile populations, such as refugees and IDPs;

• overlooked informal health sector sites, including traditional medicine or faith-based healthcare

facilities, or other healthcare sites, such as military or private facilities;

• AS sites not visited for long periods;

• AS sites not updated, thus missing newer facilities or potentially key practitioners; and

• AS sites that have closed down.

Changes can only be made through regular reviews and a thorough mapping of healthcare sites.

Special populations and the health-seeking behaviour of cases and their caregivers are also needed to

identify and address potential weaknesses and gaps in the active surveillance network (see Annex 9.

Health-seeking behaviour).

In most countries, passive and active surveillance are used in parallel.

Both systems use the same network of reporting sites, but AS takes only a subset

that are further prioritized for surveillance of AFP and classified as high-, medium-,

and low-priority sites. (See Annex 4. Routine and active surveillance.)

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

13

3. Community-based surveillance

3.1 – What is community-based surveillance?

Community-based surveillance (CBS) is a surveillance strategy in which trained community members

are engaged to report suspected AFP cases to a designated focal person based on a simple AFP case

definition.

10

What distinguishes CBS from routine and

active surveillance is that case detection

occurs outside health facilities and that

those performing case detection activities

are community members, not health

professionals.

CBS is a key method to access hard-to-reach areas and communities that are not reached by the

regular AFP surveillance system (see Supplemental strategies for special populations). CBS may

be particularly useful in settings or areas at high risk of undetected poliovirus transmission or at risk of

new outbreaks following importation or vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) emergence.

Settings conducive to CBS include:

• security-compromised areas;

• mobile populations such as nomads and seasonal workers;

• special populations that are underserved, such as refugees, IDPs, slum dwellers, ethnic

minorities, isolated religious communities or remote populations in hard-to-reach areas; and

• areas or populations relying largely on traditional medicine, where people are less likely to seek

care at a health facility.

CBS provides a link between communities and the AFP surveillance system through a designated focal

point – and it may increase community engagement in health care and acceptance of immunization and

surveillance activities.

While CBS can increase the sensitivity and timeliness of AFP case detection, it can also be resource-

intensive and should be used only where health facility-based surveillance cannot be performed or is

not functioning well. CBS methods range in resource intensity. Training, sensitization, and supervision

are minimum essential activities, and the addition of other activities comes with increased costs. Major

cost drivers include: training (initial training and

refreshers); supervision; reporting incentives or monthly

payment; and the use of digital technology, mobile

phones, or other tools (initial and recurring costs).

When considering CBS, countries should note that this

strategy may be more cost effective if used for multiple

diseases rather than a single disease.

3.2 – Setting up community-based surveillance

Initiating CBS should be carefully assessed because of its resource-intensive nature. Other

sensitization activities or adjustments to the AS network may be more efficient for closing surveillance

gaps. Programmes are advised to look first at more sustainable, cost-effective solutions.

A needs assessment must be conducted to first determine if CBS should be endeavoured. The needs

assessment explores key questions that include: How well does the current AFP surveillance system

cover or reach special populations or hard-to-reach areas? What are the real issues behind surveillance

10

Rather than the full standard AFP case definition (see Principles of AFP surveillance, section 2), a simplified AFP case

definition should be used when sensitizing community informants, such as: “Report all children with sudden presence of floppy

paralysis or weakness.”

Defining community-based surveillance

CBS is an AFP surveillance strategy that relies on

trained community members to identify cases in areas

and communities with limited access to health facilities.

Annex guidance

For more information, including steps

toward establishing CBS, see

Annex 6. Community-based surveillance.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

14

gaps? Are CBS activities currently operating for other diseases? See Annex 6 for more guiding

questions that can inform a CBS needs assessment.

Steps to establish CBS include the following activities:

1. Identify key community members, such as local and religious leaders.

2. Sensitize and brief them about polio and AFP; ask for their advice to select community volunteers.

3. Select and train volunteers on their role in CBS. Engage both male and female community

volunteers. Women can facilitate CBS in areas where access to female household heads or

members is not customary for men. Similarly, the presence of a female team member can facilitate

engaging with and accessing more traditional communities.

4. Link volunteers with a designated focal point and/or surveillance officer who will follow up and verify

AFP cases, investigate and initiate stool collection.

In some countries, CBS can be set up for the purpose of AFP surveillance only, while

in other countries, CBS is an already-existing network that is fully integrated in the

public health system for VPDs and outbreak-prone diseases, of which AFP

surveillance is only one part.

3.3 – Monitoring community-based surveillance

CBS should be carefully monitored, particularly for context-specific challenges such as hard-to-reach

populations and inaccessible areas.

Key indicators to monitor CBS include:

• percent of AFP cases reported by CBS compared with AFP cases notified by reporting sites in

the specific area; and

• percent of initial AFP case reports verified as “true AFP” versus “not AFP.”

Complete indicators are available in Annex 6. Community-based surveillance and Annex 3.

Indicators for AFP surveillance.

3.4 – Challenges with community-based surveillance

• Implementing and sustaining effective CBS can be resource intensive. The resources needed for

CBS depend upon the country context and the decisions of the surveillance team.

• Hard-to-reach areas present unique challenges for ensuring a reliable line of communication

between community informants and surveillance officers. To address this, some teams offer mobile

phones or dispense petty cash to pay for communication expenses.

• Low literacy levels within local communities may require more time and effort on the part of the

public health staff for adapting AFP surveillance training and sensitization protocols.

• Partially or fully inaccessible areas can impede monitoring and supportive supervision of CBS

informants, as well as create problems for conducting AFP case verification and investigation. If this

occurs, AFP cases may need to be brought outside inaccessible areas for investigation.

• A considerable percentage of reports of “suspected AFP” may not meet the standard AFP case

definition and may give a low yield of actual (“true”) AFP cases, which may increase the workload of

public health staff through the added time needed for verification and investigation.

For more on CBS-related challenges and solutions, see Annex 6.

CBS for polio can be also referred to as “a network of informants,” “village polio

volunteers” or “informers.” Depending on the country, community volunteers may or

may not be remunerated or financially motivated and may or may not be working full

time on polio surveillance.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

15

4. Supplemental strategies for special populations

Certain population groups are underserved or not served at all by health systems. They are also

persistently missed by surveillance efforts. While the reasons for these gaps are varied, one finding is

that persistently missed population groups often belong to high-risk mobile populations or reside in

hard-to-reach or inaccessible areas, including areas affected by insecurity and conflict. These special

population groups are particularly important for disease control and eradication programmes because

they have higher susceptibility to infection due to low immunization coverage and are therefore more

likely to transmit viruses – and more likely to be missed by surveillance systems.

Guidelines for Implementing Polio Surveillance in Hard-to-Reach Areas and Populations details some

strategies (of which CBS is one approach) for implementing surveillance among special populations,

with a focus on high-risk mobile populations.

11

4.1 – What are special populations?

Several different marginalized population groups are at

risk of being underserved or altogether missed by

surveillance efforts. These include:

● mobile populations: nomads and seasonal migrants

such as agricultural, mine, brick kiln or construction

workers;

● refugees and IDPs living in camps and in host

communities;

● populations in settled areas which are underserved

by existing health services such as cross-border

populations, slum dwellers, ethnic minorities,

islanders, fishermen and those living in hard-to-

reach areas; and

● totally inaccessible population groups, such as

those in security-compromised and conflict-affected

areas.

4.2 – Identifying and mapping special groups

By identifying, mapping and profiling unserved or underserved populations, special surveillance

strategies can ensure that such populations are covered by polio immunization and surveillance.

The following data and information are critical to better characterize and reach such groups:

● geographic location and population size for mobile groups: itineraries and routes of migration,

timing and possible seasonality of nomadic movement;

● current access to health services and health-seeking behaviour (see Annex 9. Health-seeking

behaviour);

● availability of the existing surveillance network (facility- or community-based) to detect AFP cases in

this special population;

● identification of service providers who exist in the area but are not yet participating in polio activities

(public and private, including NGOs or faith-based organizations);

● availability of options to develop communication activities targeting these special groups;

● means of communication through the availability of network coverage and/or readily available use

of cell phones for public health officers and community workers and volunteers; and

● general information, such as language, literacy, community structure in terms of leaders and

influencers.

11

Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Guidelines for Implementing Polio Surveillance in Hard-to-Reach Areas &

Populations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Guidelines-polio-

surveillance-H2R-areas.pdf).

Special populations and insecurity

While some countries have hard-to-reach

areas due to geographic barriers and

transportation issues, some countries face

particular challenges in insecure and

conflict-affected areas.

In Borno State, Nigeria, ongoing conflict and

insecurity left large parts of the population

inaccessible for a prolonged period of time,

resulting in WPV1 transmission missed for

several years and detected late in 2016.

Parts of Syria, Yemen and Iraq have

historically faced similar scenarios, where a

lack of security and safety prevents field

staff from reaching communities to conduct

immunization and surveillance activities.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

16

4.3 – Implementing a mix of surveillance strategies for each special group

Once special populations have been identified and

profiled, surveillance approaches can be specifically

tailored to ensure each group is adequately covered by

poliovirus surveillance (Table 3). A set or mix of

suggested surveillance strategies for each kind of special

population is recommended.

12

The key recommended strategies are:

1. Enhanced AFP surveillance with ad hoc AFP case search and systematic contact sampling.

• Ad hoc AFP case search in large gatherings of nomads, for example during SIAs and

during mobile outreach services (Annex 11).

• Systematic AFP contact sampling for all inadequate AFP samples, with one sample each

from three contacts of an AFP cases with inadequate samples, for example. However, in

coordination with surveillance and laboratory teams, this can be expanded to all AFP cases

from special populations (Annex 12).

2. Targeted healthy children sampling can be conducted in special populations that are at high

risk for poliovirus; however, this is not a routine strategy and can only be initiated in

coordination with and with the approval of surveillance and laboratory teams at the national and

regional levels (Annex 13).

3. Ad hoc environmental surveillance sampling sites can enhance surveillance in areas

considered at high risk of poliovirus circulation because of an outbreak or the sudden influx of

an at-risk population.

13

This strategy should only be considered after strengthening AFP

surveillance and in coordination with the laboratory.

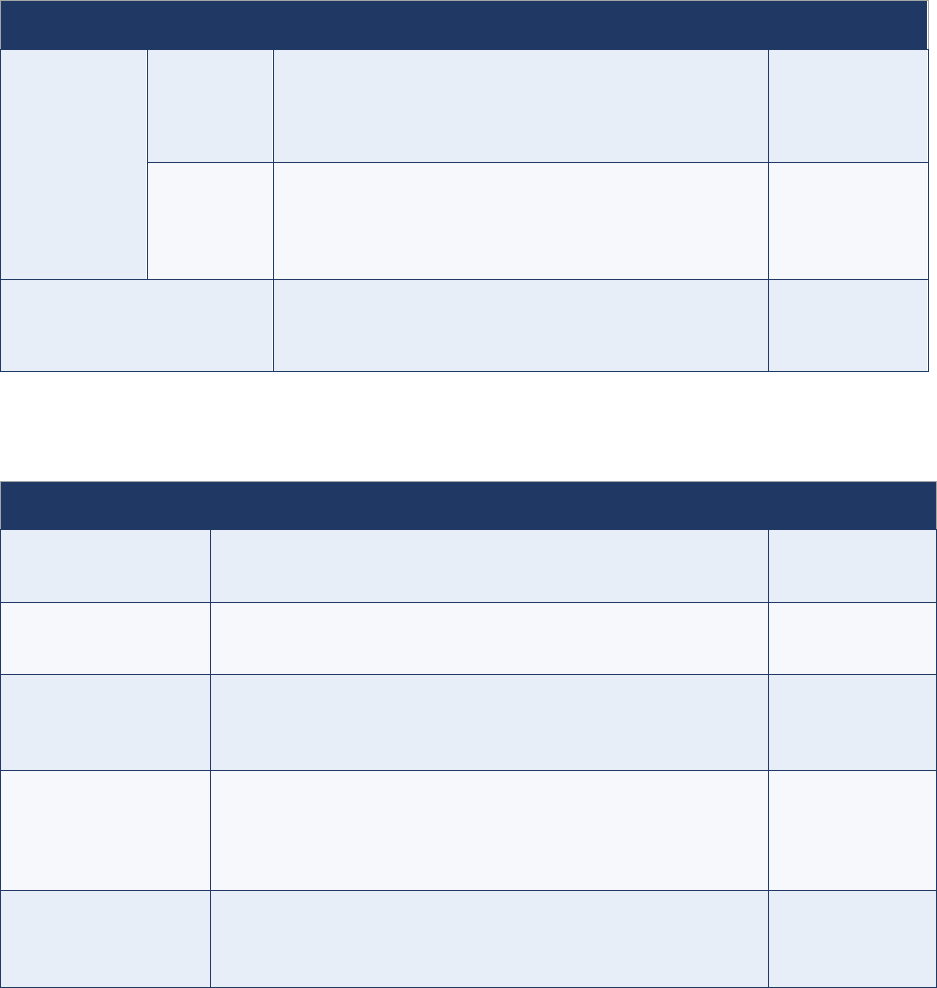

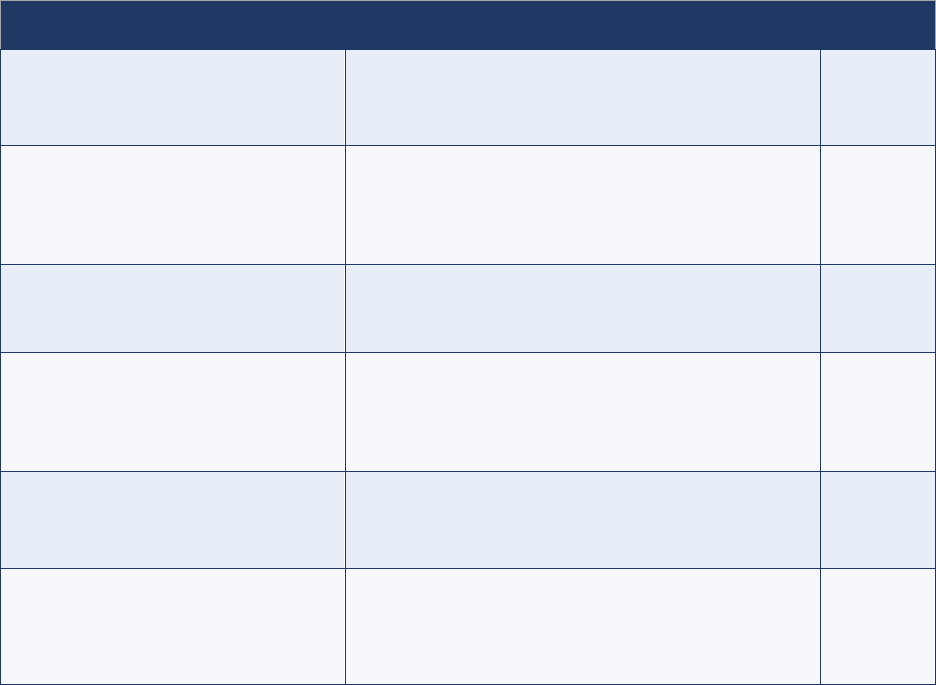

Table 3. Examples of activities by type of special populations

Population type

Activity examples

Populations living

in security-

compromised

areas

● Access mapping and analysis of population dynamics and movements; access

negotiation, if needed.

● Coordination with armed forces or groups and relevant partners.

● Review of surveillance network and establishment of CBS as appropriate, including

identifying and training appropriate focal points.

● Enhanced surveillance in parts of the country bordering inaccessible areas and

wherever IDPs come out of inaccessible areas and are received (e.g., adding to

reporting sites based on health-seeking behaviour, identification and training of local

informants).

CBS = community-based surveillance; IDP = internally displaced populations

12

Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Guidelines for Implementing Polio Surveillance in Hard-to-Reach Areas &

Populations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Guidelines-polio-

surveillance-H2R-areas.pdf).

13

Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for Polio Environmental Surveillance

Enhancement Following Investigation of a Poliovirus Event or Outbreak. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020

(https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/SOPs-for-Polio-ES-enhancement-following-outbreak-20210208.pdf).

Annex guidance

For surveillance strategies suitable to

different kinds of special populations, see

Annex 10. Special populations groups.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

17

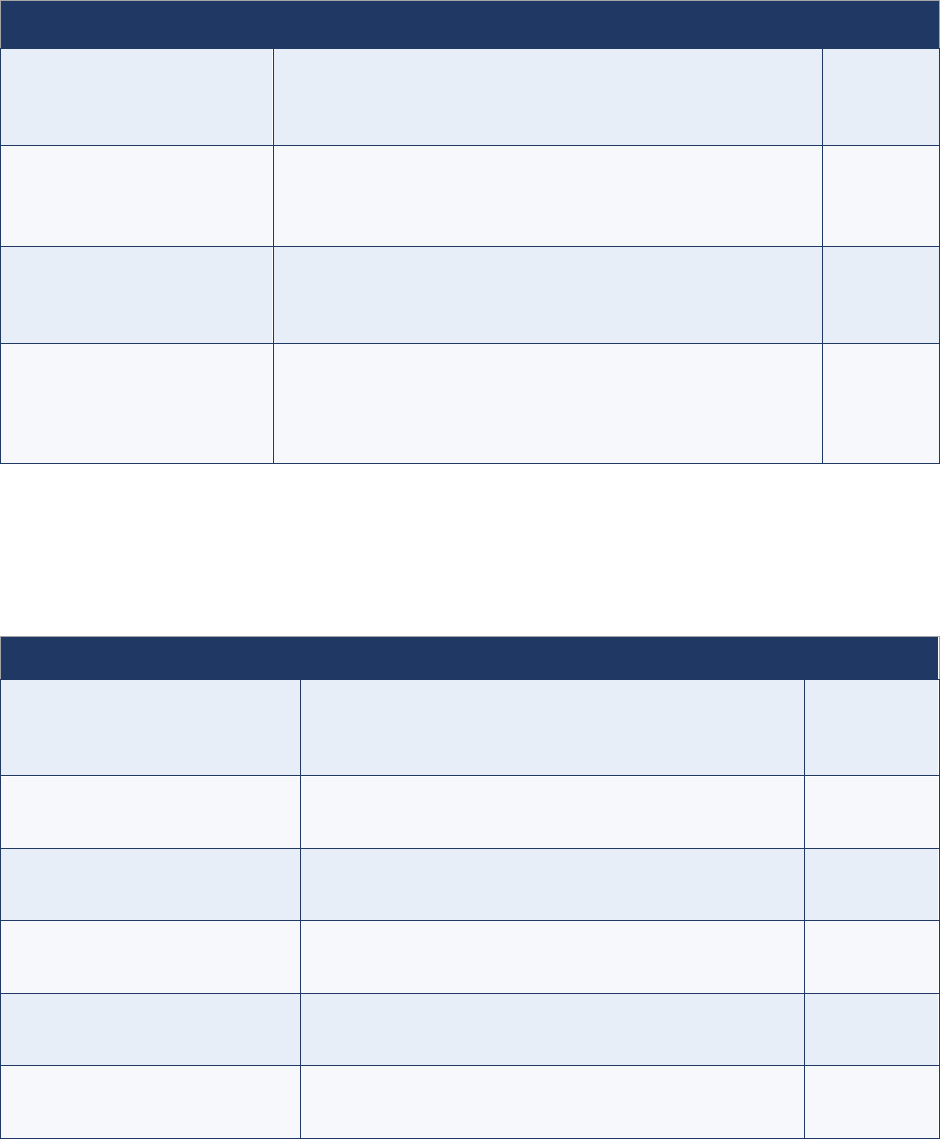

Table 3 (continued)

Population type

Activity examples

Nomadic

populations

● Mapping and profiling of nomadic groups in coordination with nomad leaders; AFP

focal points designated for each nomad group.

● Determining itineraries and migration pathways; mapping healthcare facilities and

providers, as well as veterinary services, along the route.

● AFP sensitization among providers and in public places along migration pathways

(i.e., in markets, at watering points and camps frequented by nomads); study of

nomads’ health-seeking behaviour.

● Regular contact with AFP focal points established and maintained.

● A similar approach should be used for other mobile population groups, as appropriate:

seasonal migrants; mine, brick kiln and construction workers; etc.

Refugees and IDPs

in camps

● Camp AFP focal point identified, designated and included in the AS network.

● Profile assessed of new arrivals: origin, immunization status, etc.

● Active AFP case search.

● Permanent vaccination and surveillance team installed.

Refugees and

informal IDPs in

host communities

and outside camps

● Key informants identified from the community and included in AS network (see

Community-based surveillance).

● Tracking of IDPs and refugees in the community via special “tracker teams” to support

understanding their health-seeking behaviour.

● AS network adjusted to include providers serving refugees and IDPs.

Cross-border

groups

● Mapping of official and informal border crossings, villages and settlements, special

groups, gathering places and seasonal movements; surveillance networks installed on

both sides of the border.

● Averages estimated for numbers of population moving and migrating across borders.

● Regular contact between AFP surveillance officers on both side of the border to

ensure sharing of data, cross notification, joint investigation and tracking of mobile

groups.

● Organizations working at border entry and exit points identified (e.g., immigration, port

health services and police); orientation and sensitization on polio and AFP

surveillance provided to healthcare workers on both sides.

Communities in

urban slums

● Profile of communities and their origin.

● Health-seeking behaviour studied, with adjustments to AS network.

● Active AFP case search conducted.

● Evaluation of any need to add environmental surveillance (ES) sites.

Other hard-to-

reach communities

● Mapping and profile of special populations who may live in remote areas such as

islanders and highlanders, or ethnic minorities who may not access the same health

facilities as the broader population.

● Identification of and regular contact with local key informants.

● Study health-seeking behaviour of these communities and adjust the network.

AFP = acute flaccid paralysis; AS = active surveillance; CBS = community-based surveillance; IDP = internally displaced population

The decision to develop, implement and possibly modify any of these strategies should be discussed by

all stakeholders involved at the local, national, and regional levels, including national or regional

laboratories.

4.4 – Challenges with supplemental strategies for special populations

Challenges to anticipate when implementing poliovirus surveillance in special groups are similar to

those listed for CBS. See also Annex 10. Special population groups and Annex 6. Community-

based surveillance.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

18

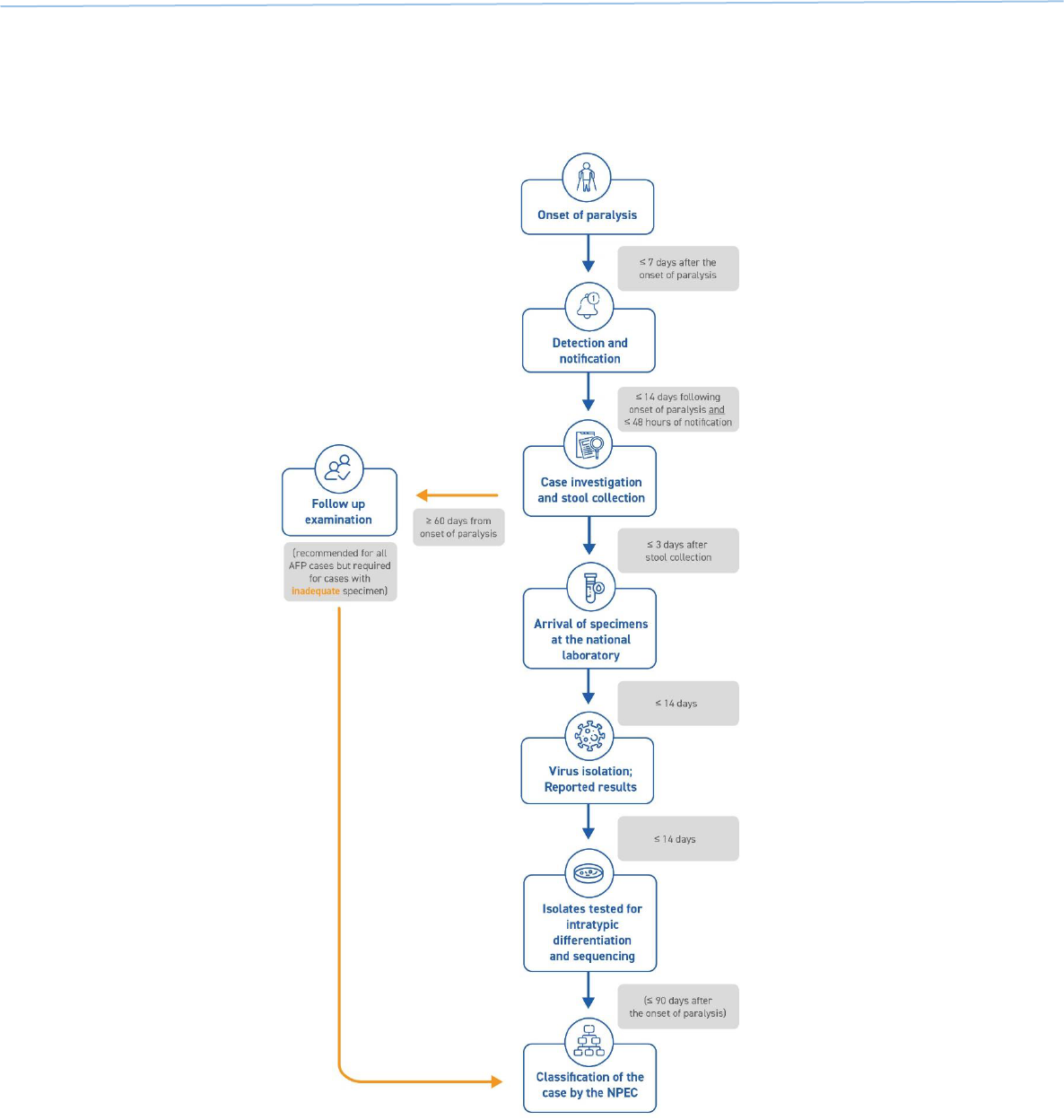

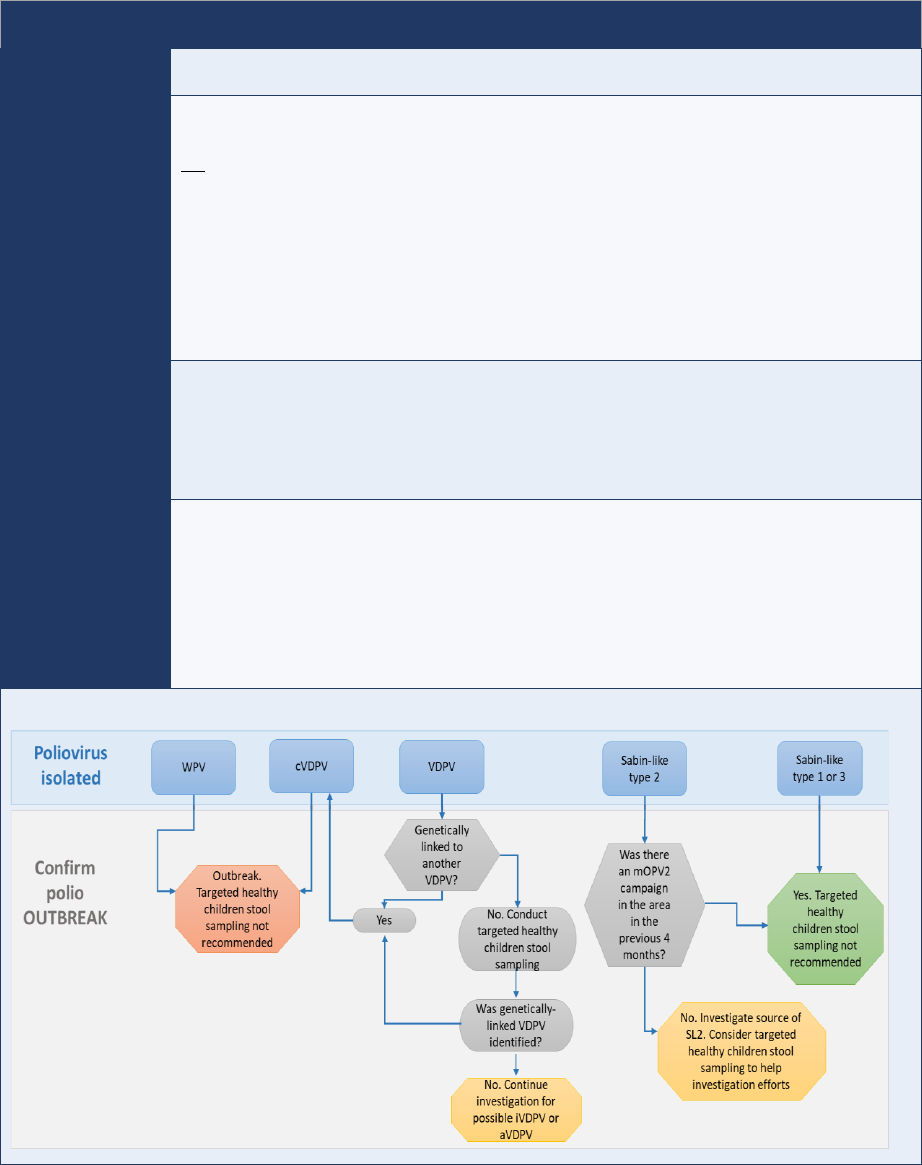

CASE ACTIVITIES for AFP surveillance

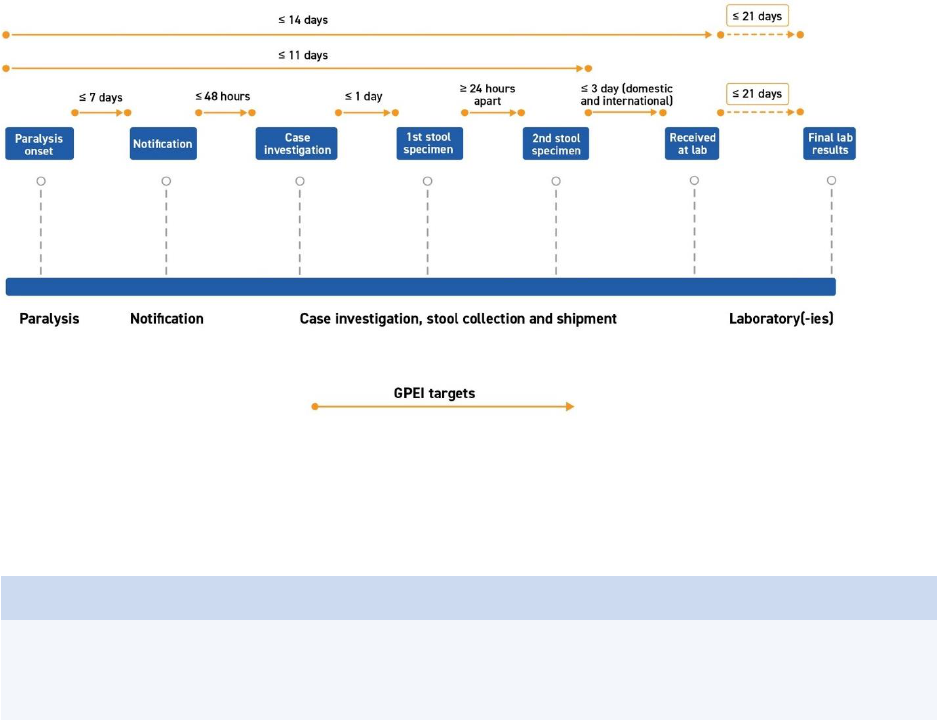

Case-related activities for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance – from the onset of paralysis in a

patient to final case classification – require timely coordination between field and laboratory surveillance

(Fig. 1). All case-related activities should progress quickly so final classification by a National Polio

Expert Committee (NPEC) takes place within 90 days of paralysis onset.

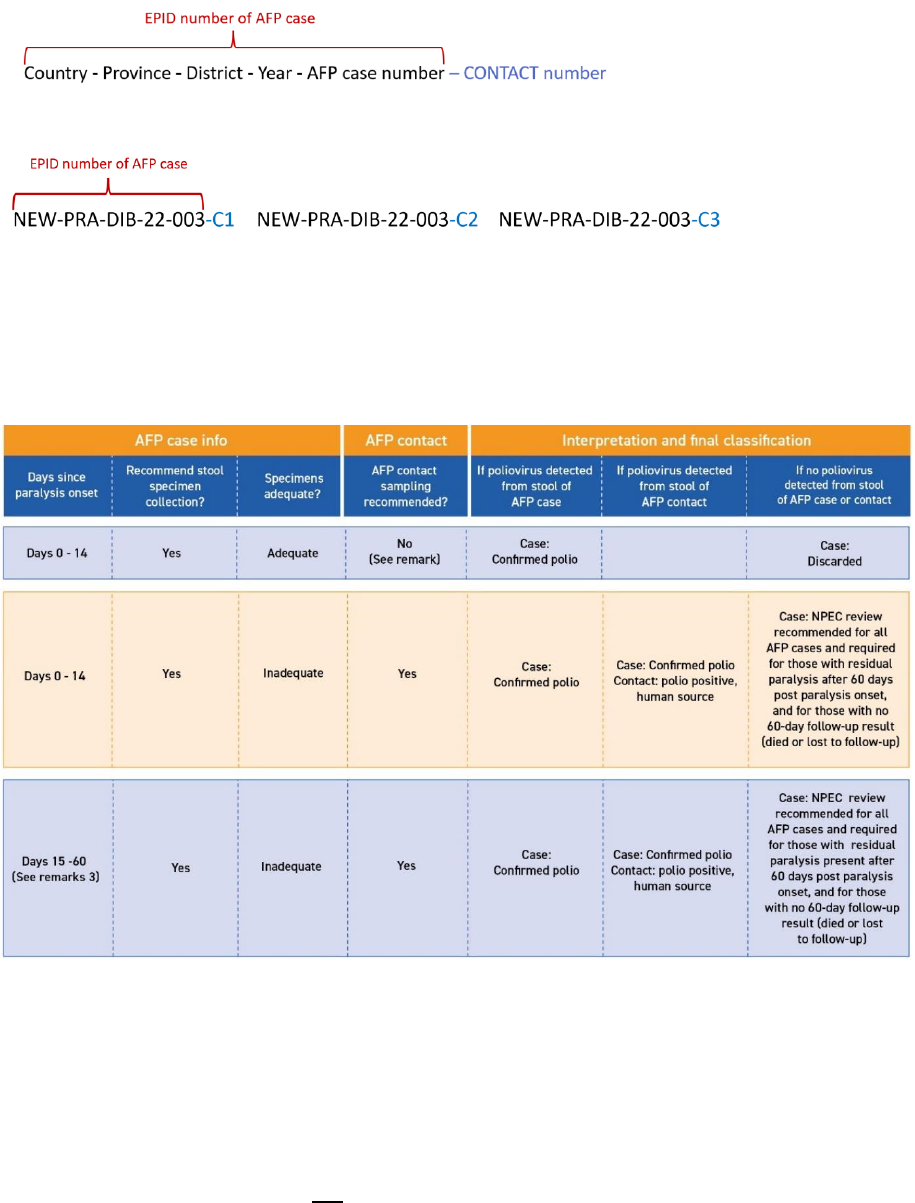

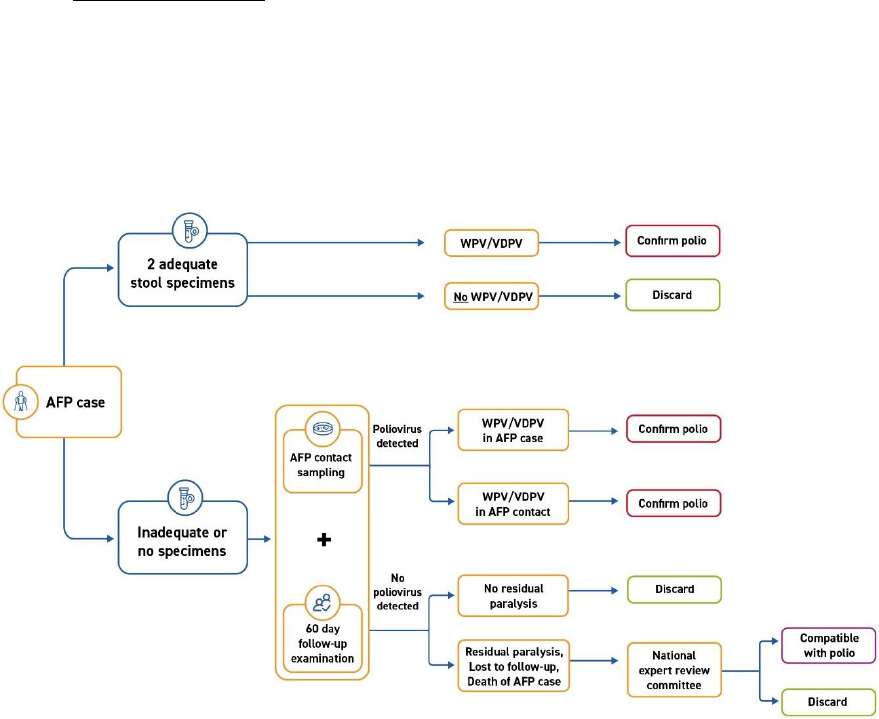

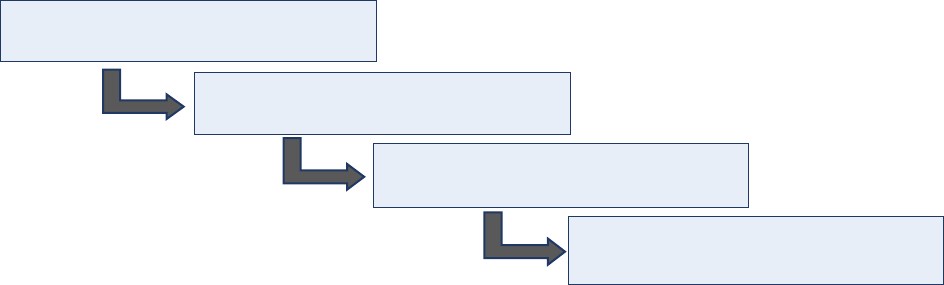

Fig. 1. Process of AFP surveillance

NPEC = National Polio Expert Committee

Source: WHO.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

19

1. Timely detection

Responding swiftly to a possible case is critical: the earlier poliovirus is detected and confirmed, the

faster outbreak response can be implemented to end transmission. The goal established by the Global

Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) under its 2022–2026 Strategy is that all polioviruses should be

confirmed and sequenced within 35 days of the onset of paralysis.

14

Given this accelerated timeline,

field and logistics activities – from onset of paralysis to the arrival of stool specimens at a WHO-

accredited polio laboratory – must be completed within 14 days (Fig. 2). Note that certification

standards and indicators remain unchanged (see Annex 3. Indicators for AFP surveillance).

Fig. 2. Timeliness of detection, 35 days (onset to final lab result)

Source: WHO.

1.1 - Reduce delays

Every stage of the process depicted above (Fig. 2) should be targeted for time-saving interventions, as

timeliness will be closely monitored (see Monitoring and Annex 3. Indicators for AFP surveillance).

2. Case notification and verification

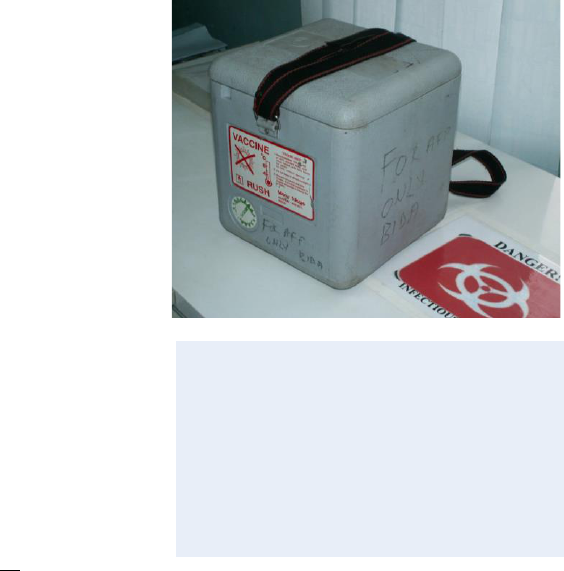

To support case verification and investigation, all supplies and materials should be prepared in advance

to allow quick deployment of the investigation team. This includes case investigation forms (CIFs),

laboratory request forms, stool specimen collection kits and stool carriers.

2.1 – Notify the case

AFP cases must be notified within seven (7) days of the onset of paralysis. A physician, health worker,

or community informant or volunteer who identifies an AFP case must report it immediately to (or

notify) the public health surveillance team at the district or provincial level.

When in doubt, always report and investigate.

14

Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Polio Eradication Strategy 2022–2026: Delivering on a promise. Geneva: World

Health Organization; 2021 (https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/345967/9789240031937-eng.pdf).

Annex guidance

Annex 14. Rapid case and virus detection highlights bottlenecks and delays that may occur at various

stages and administrative levels, their possible causes, and ways the programme can address them.

Definitions to support case investigations are found in Annex 1. Poliovirus.

Global guidelines for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in the context of poliovirus eradication

20

3. Case investigation and validation

Once reported, the case must be investigated within 48 hours of notification by a trained,

designated AFP focal point or surveillance officer who completes the CIF.

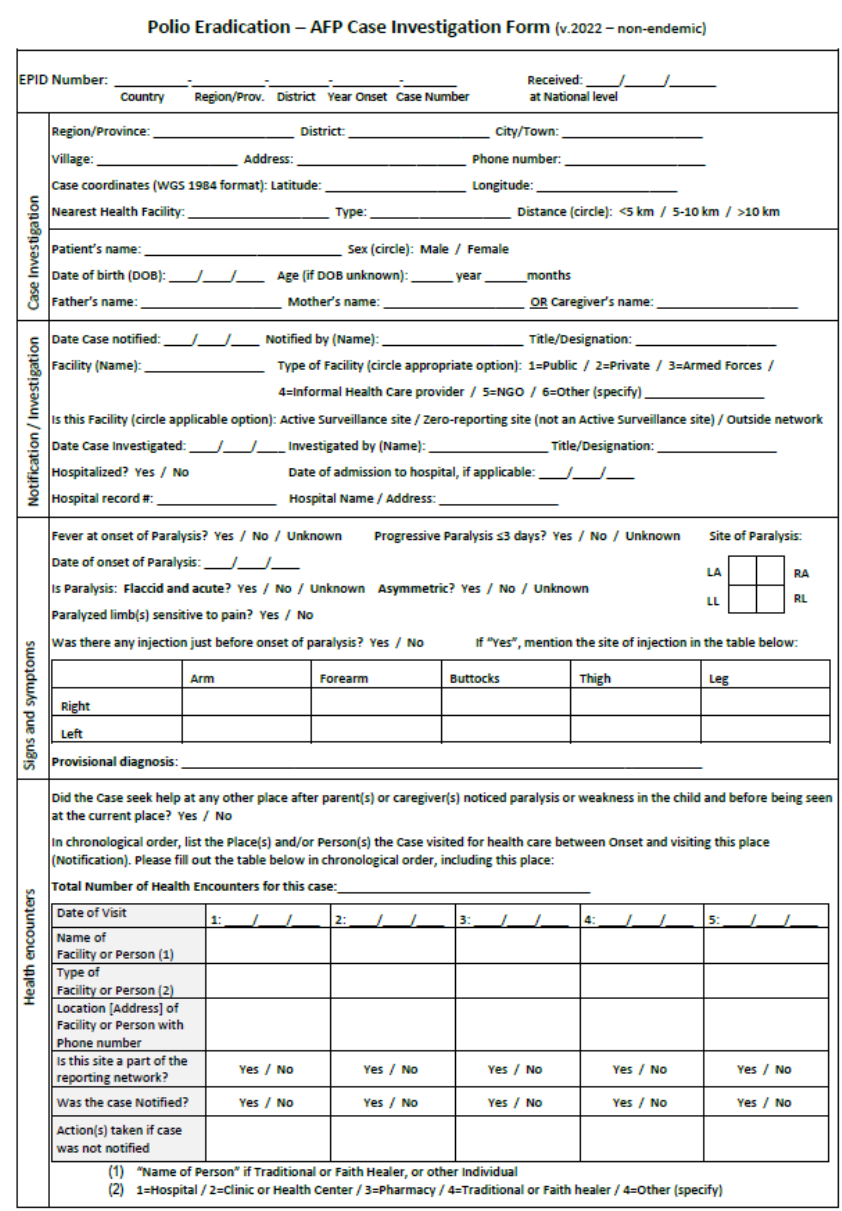

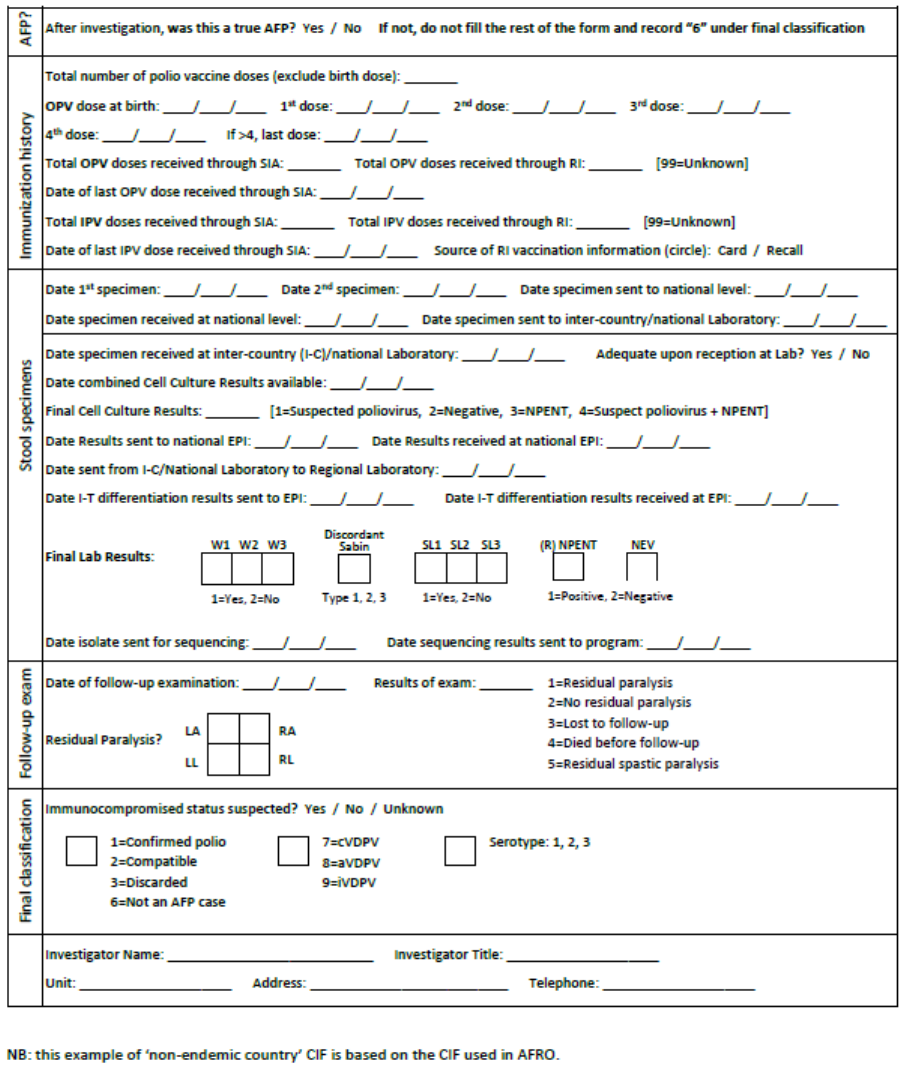

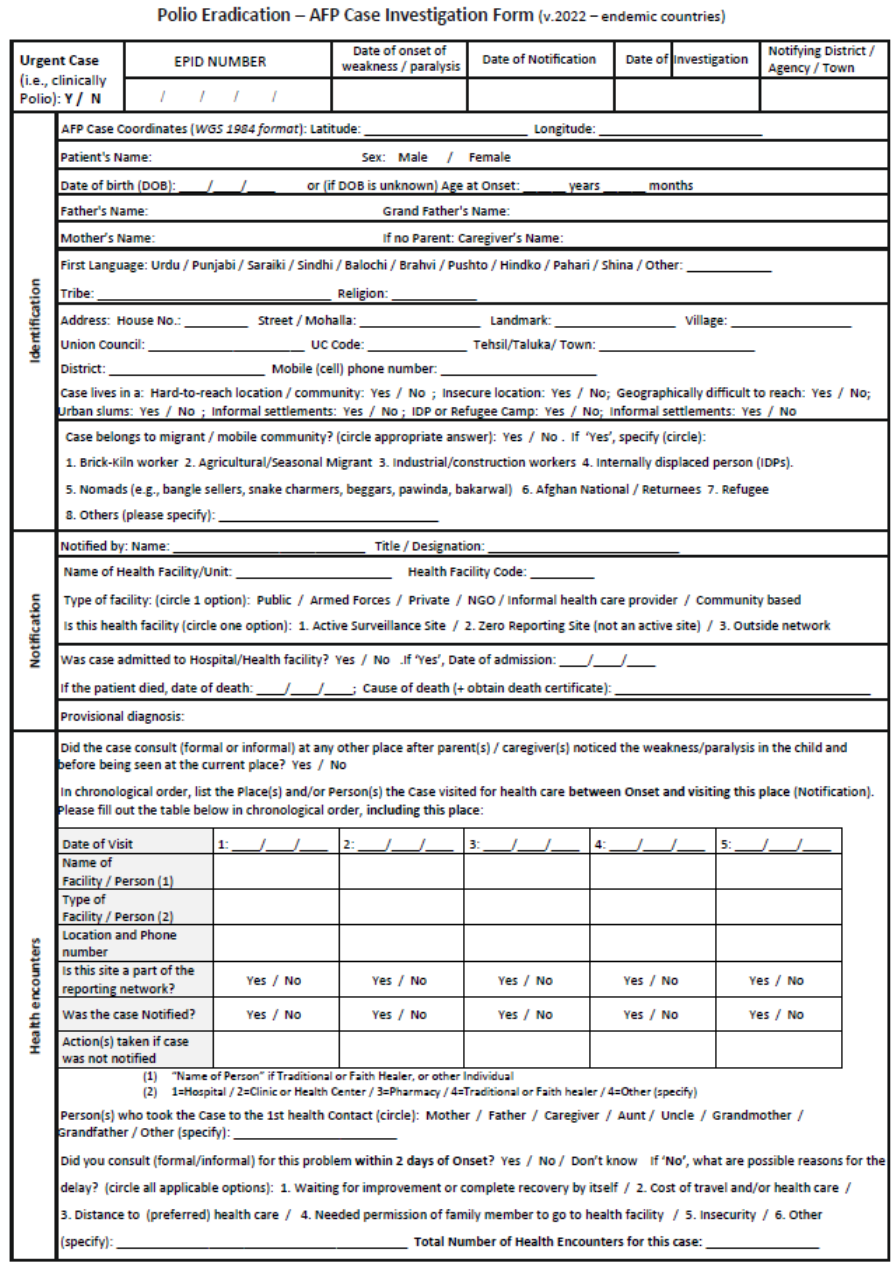

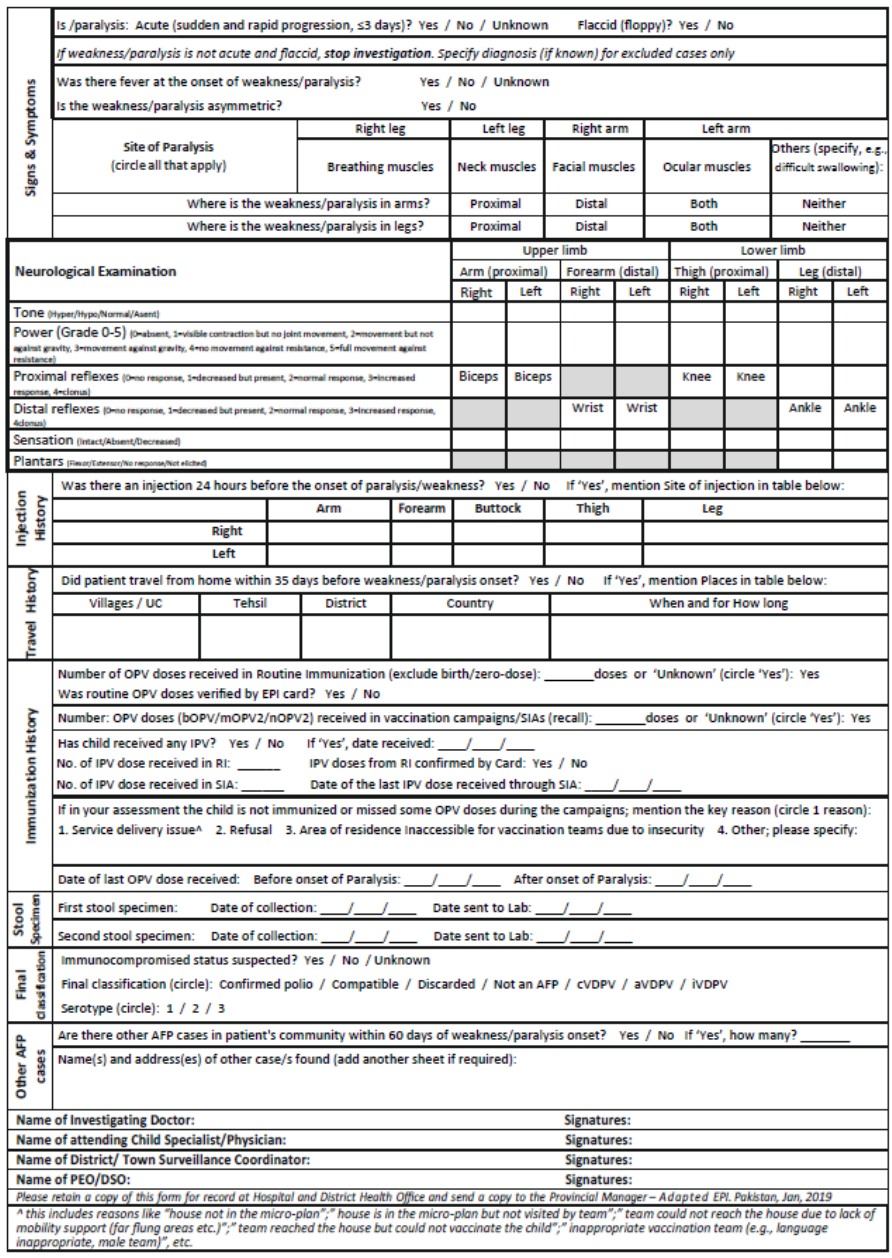

To minimize the risk of missing key information that may explain delays in detection, CIFs capture the

social profile of cases and their community, as well as health-seeking behaviour and gender-related

information. (See Annex 7. Examples of forms for modified CIFs for endemic and non-endemic

countries.)

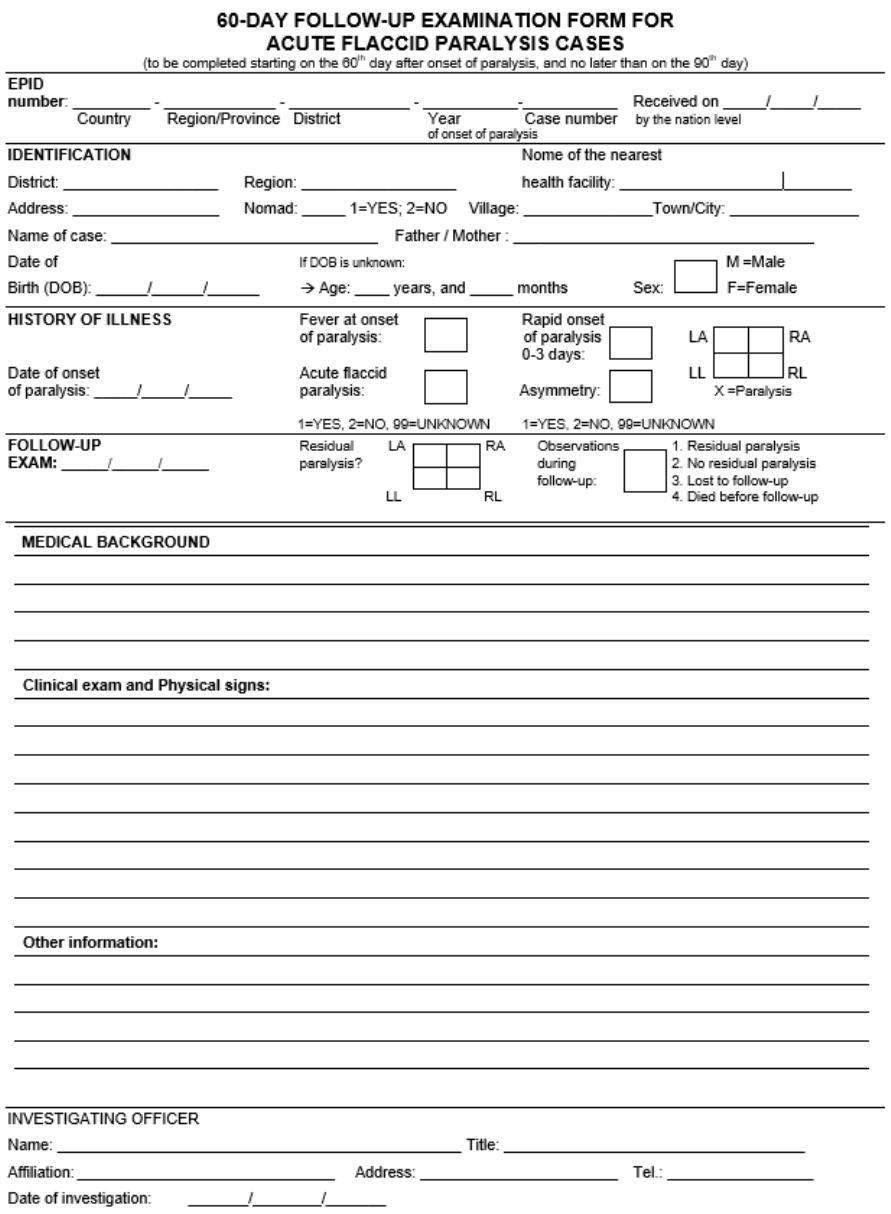

3.1 – Verify the case