I

n 2010 Congress enacted the Affordable Care Act, a historic and vigorously debated law designed

to dramatically overhaul the health system. Included in the Affordable Care Act are comprehensive

prevention provisions consistent with those called for by the American Public Health Association

(APHA) in its health reform agenda and supported by other leading experts in population health

and prevention.

12

The Affordable Care Act, if it is adequately funded, effectively implemented, and creatively

leveraged through public and private-sector partnerships, will mark the turning point in the fundamental

nature of our health system, initiating the transformation of our health system from one that treats sickness

to one that promotes health and wellness. This issue brief begins (Section III) by summarizing the state of

public health in the United States, including some measures of the growth of preventable diseases. Section

IV describes the major provisions of the Affordable Care Act that address prevention through: (1) investing

in public health; (2) educating the public; (3) expanding insurance coverage and requiring that health insur-

ance include recommended preventive benefits; and (4) building capacity for better prevention in the future

through demonstrations, research and evaluation.

American Public Health Association

OCTOBER 2010

Prevention Provisions

in the Affordable

Care Act

Gail Shearer, MPP

800 I Street, NW • Washington, DC 20001-3710 • 202-777-APHA • fax: 202-777-2534 • www.apha.org

Executive Summary

2

Section V identifies key implementation

issues. Federal, state and local policy makers

charged with implementing the Affordable

Care Act face challenging issues in the near

future such as: (1) deciding how to allocate

new prevention funds and protect exist-

ing funds; (2) allocating grants (federal) and

applying for grants (state and local) so that

prevention efforts are coordinated effi-

ciently; (3) learning the best ways to ensure

the accessibility of available information

about the benefits of prevention to both the

general population and hard-to-reach popu-

lations; and (4) learning how best to com-

municate with consumers and patients so

that they act on that information to prevent

disease and disability and improve health.

Successful implementation of the preven-

tion provisions of the Affordable Care Act

will require the devoted efforts of staff at all

levels of government, of all members of the

healthcare and public health professional

workforce, and of health plans and insurance

companies. It also will demand the engage-

ment of citizens, who will need to be more

educated about choices in the health system.

Section VI includes recommendations for

policymakers to: (1) leverage health reform

funding and other existing funding to ex-

pand total funds for prevention and maxi-

mize progress; (2) conduct research about

how to communicate prevention messages

most effectively to traditionally under-

served populations; and (3) improve public

health by making comparative effectiveness

research on prevention a priority and by ex-

panding successful prevention pilot projects.

This issue brief does not cover workforce

issues such as the expansion of primary care

and community health centers. These im-

portant areas will be addressed in a separate

forthcoming issue brief.

I. Introduction and

Overview

[Health reform’s] aim is to transform

America’s current sick care system into

a genuine health care system, one that is

focused on keeping us healthy and out of

the hospital in the first place.—Senator Tom

Harkin

3

Senator Harkin, a long-time leader on

preventive health care, captures in his quote

the hope that the landmark health reform

legislation enacted in 2010 will make

fundamental changes in our system so that

it prevents disease and promotes wellness.

The Affordable Care Act, signed into law on

March 23, 2010

4

, included comprehensive

initiatives that elevate the nation’s commit-

ment to preventing disease and promoting

wellness. Its provisions cut across a range of

needs that have been articulated by ex-

perts.

5

These include the establishment of a

large Prevention and Public Health Fund,

creation of a National Prevention, Health

Promotion and Public Health Council to

coordinate federal prevention initiatives,

development of new grant programs to

fund state and local initiatives at the com-

munity level, a new requirement that health

insurance policies cover recommended

preventive services, and development and

implementation of a goal-driven strategy

for prevention that will include a timeline

for measurable actions. The law also requires

that changes to insurance coverage and poli-

cy must be guided by scientific evidence,

and calls for evaluations and reports that

provide an opportunity to learn from expe-

rience and make improvements over time.

The American Public Health Association

(APHA) and the public health community

have long supported health reform that ex-

pands health insurance coverage to the mil-

lions of uninsured Americans and provides

The American Public Health Association (APHA) and the public health community have long supported

health reform that expands health insurance coverage to the millions of uninsured Americans and provides

access to care for all residents. APHA also has supported the creation of a dedicated funding stream for

prevention, wellness and public health.

6

H

ealth reform’s aim

is to transform

America’s current

sick care system into a genu-

ine health care system, one

that is focused on keeping us

healthy and out of the hospital

in the first place.

—Senator Tom Harkin

3

3

access to care for all residents. APHA also

has supported the creation of a dedicated

funding stream for prevention, wellness

and public health.

6

APHA’s 2009 Agenda

for Health Reform describes the population-

based services needed to help communities

and individuals be healthy.

4

A number of

organizations and coalitions that promote

improved public health have taken similar

positions.

7

The Affordable Care Act addresses many

of these recommendations from the public

health community and represents a bold

step for the nation in creating a system that

promotes wellness.

This issue brief addresses the provisions in

health reform that directly relate to preven-

tion. It does not deal with the many indirect

ways that health reform promotes health

and prevents disease, most notably by reduc-

ing the ranks of the uninsured who have

faced financial and access barriers to both

acute and preventive care. Nor does it cover

workforce issues, such as those related to the

expansion of primary care, the public health

workforce, medical homes, and community

health centers, all of which will play a cru-

cial role in supporting the transformation of

our health care culture to one that embraces

prevention.

At this time, there is ambiguity in the

law about the extent to which funds are

authorized and/or appropriated, creating

uncertainty about the precise amounts of

funding that will actually be available. The

law often uses language such as “there are

authorized to be appropriated such sums as

may be necessary to carry out this section”

(Section 4004), and “out of any funds in the

Treasury not otherwise appropriated, there

are appropriated $1,000,000 for fiscal year

2010 to carry out this subsection” (Section

4203). Many sections do not include any

language about funding, creating uncer-

tainty about future funding. The Congres-

sional Budget Office has published a table

of authorizations subject to appropriation

in order to clarify which provisions have

specific dollar amounts authorized (by year)

and which provisions do not yet have a

specified budget.

8

The success of the Afford-

able Care Act’s prevention and public health

initiatives will depend not only on whether

the authorized funds are appropriated, but

also on the ability to achieve changes across

many non-health care aspects of our society

through healthy environments, education, a

more nutritious food supply, and modifica-

tion of individual behaviors.

After a brief overview of the problem

of inadequate focus on prevention in the

past, this issue brief describes the major

prevention provisions in health reform

and identifies some of the key policy and

implementation issues that lie ahead. For

an implementation timeline of the public

health, prevention and wellness provisions in

the Affordable Care Act, see Appendix 1.

II. The Problem

Rising rates of preventable disease and

death, as well as international comparisons

of health outcome measures, reveal that

Americans are not as healthy as they could

be, and that they are becoming increasingly

unhealthy over time. The relatively un-

healthy population stems from many factors,

including but not limited to the health sys-

tem. Lack of access to a high-quality educa-

tion, nutritious food, adequate exercise,

and a healthy and safe environment are key

factors driving the diminishing health of the

T

he Affordable Care Act addresses recommendations from the public

health community and represents a bold step for the nation in creat-

ing a system that promotes wellness.

4

nation. In the absence of other changes, even

a complete transformation of the health sys-

tem is not sufficient to significantly alter the

growing problems of heart disease, obesity

and cancers that affect our nation’s health.

Preventable disease and death: Prevent-

able disease and death impose a large burden

in the United States. In 2009, an alarming

26.6 percent of the U.S. population was

obese,

9

8.2 percent of the adult U.S. popu-

lation had diabetes,

10

and 27.8 percent of

the adult population had high blood pres-

sure.

11

Lifestyle behaviors and choices, such

as tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity,

and alcohol consumption are primary deter-

minants of disease and death in the United

States, yet these have historically received

little attention from our health system with

respect to preventing them in the first place.

This lack of attention has resulted in an

estimated 60 percent of deaths in America

being attributed to “social or behavioral cir-

cumstances.”

12

In many cases, the unhealthy

choices that lead to poor health outcomes

are not in fact lifestyle “choices,” but rather

the consequences of economic and geo-

graphic factors that restrict or prevent access

to healthy food and safe environments in

which to exercise.

Research has shown that coronary artery

disease can be reversed with lifestyle changes

including diet, stress reduction, psychosocial

support and exercise.

13

Recent growth in the

self-reported obesity rate, a 1.1 percentage

point increase (2.4 million additional people)

between 2007 and 2009, is another indica-

tor of the growth of preventable disease

and the need for an aggressive public health

focus.

14

The World Cancer Research Fund

and American Institute for Cancer Research

found that cancers are principally caused by

environmental factors, the most important of

which are tobacco, diet, physical activity and

exposures in the workplace. Two-thirds of all

cancers can be eliminated through changes

to diet, physical activity and tobacco use.

15

It is widely recognized that as a country we

need to take steps to prevent obesity, and that

problems with “the availability of healthy

and affordable food options, eating patterns,

levels of physical activity, quality of the built

environment, social and cultural attitudes

around body weight, and reduced access to

primary care” all contribute to the preva-

lence of obesity.

16

International comparisons of health:

The United States lags far behind other

countries in key health measures, yet we

manage to spend far more per capita each

year on health care than other countries,

$7,680 per person, for a national total of

$2.3 trillion in 2008.

17

Male life expectancy

(at birth) in the United States in 2006 was

75, compared with 79 in Australia, 77 in

Austria, and 79 in Japan.

18

“Healthy life ex-

pectancy,” a measure of the number of years

a newborn can be expected to live a produc-

tive and healthy life, is 70 years in the United

The World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research found that cancers are

principally caused by environmental factors, the most important of which are tobacco, diet, physical

activity and exposures in the workplace. Two-thirds of all cancers can be eliminated through changes to

diet, physical activity and tobacco use.

16

R

esearch has shown that coronary artery disease can be reversed

with lifestyle changes including diet, stress reduction, psychosocial

support and exercise.

13

5

States, less favorable than 30 other countries

such as the United Kingdom, Spain, and

Japan, which has the highest life expectancy

of 76.

19

Infant mortality in the United States

was seven per 1,000 live births in 2009, with

36 countries (out of 193 rated) having lower

infant mortality rates.

20

A Commonwealth

Fund international comparison of health

systems placed the United States as worst in

an analysis that considered measures such as

quality, access, efficiency, equity and cost.

21

Health System Failures: Primary Care

Shortages. A central challenge to the health

system is the short supply of primary care

providers and public health professionals, and

their maldistribution across the nation. Sev-

enty percent of health leaders surveyed by

the Commonwealth Fund said that address-

ing the shortage of trained health care work-

ers was an essential, urgent part of health

reform.

22

The Institute of Medicine has

documented how demands for the health-

care workforce will grow because of the

aging of the Baby Boomers.

23

The current

shortage of primary care providers, especially

in rural areas, before Baby Boomers turn 65

and before the enactment of the Affordable

Care Act, undoubtedly means that short-

ages will intensify over the coming years

as Boomers need more health services, and

implementation of the law removes financial

barriers to seeking health care. Additionally,

the recession, the high unemployment rate,

and continued financial pressures has led to a

long-lasting crisis affecting state budgets, and

resulted in severe cuts in the workforce that

provides basic health, public health and other

services at the state and local levels.

Health System Failures: Financial Incen-

tives. Another factor contributing to the

declining population health is the health care

financing system, which is largely fee-for-

service. The U.S. health system is riddled

with financial incentives to provide medical

care to treat disease (e.g., coronary bypass

and bariatric surgery) rather than offer

primary care and guidance to address health

through basic lifestyle changes before the

disease process begins.

Focus on Children as a Proxy. The health

of the nation’s children best exemplifies our

lack of attention to prevention. The follow-

ing measures indicate how poorly our nation

is doing with respect to raising healthy

children.

Only 70 percent of pregnant women have

access to adequate prenatal care.

24

Seventy-eight percent of children be-

tween the age of 19 months and 35

months received complete immuniza-

tions in 2009 (a 42 percent increase in 10

years).

25

In 2007-2008, 19 percent of children six

to 17 years old were obese.

26

Nine percent of children have asthma,

with 400,000 of these having mild to se-

vere asthma.

27

In 2008, 25 percent of 12th graders re-

ported having five or more alcoholic bev-

erages in a row in the last two weeks.

28

An estimated 17 percent of children have

“some type of developmental disorder,”

and 21 percent have a “diagnosable mental

or addictive disorder”;

29

About 1.2 million children drop out of

high school every year, with only 70 per-

cent of freshmen ultimately graduating

from high school.

30

The Surgeon General reported a suicide

incidence of 9.5 per 100,000 for 15- to

19- year-olds in 1996.

31

There is increasing awareness that early

environmental factors before birth and in

early childhood influence health over the

long term. These disturbing measures of

the health status of children are troubling

harbingers of health status of the population

of the future.

Making the Case for Prevention: Another

way to consider the value of prevention is

to examine the “return on investment” for

prevention dollars. A report by Trust for

America’s Health estimated that investments

in community-based programs in initiatives

that encourage physical activity, good nutri-

tion and tobacco cessation can yield very

favorable returns on investment, returning an

overall $5.60 in health cost savings for every

$1 spent.

32

Health outcomes reflect the physical,

social, and demographic environments and

communities in which people live, work,

play, learn, pray and seek healthcare. Each

plays a critical role in determining the health

A

Commonwealth

Fund international

comparison of health

systems placed the United

States as worst in an analysis

that considered measures such

as quality, access, efficiency,

equity and cost.

22

6

of a population. Healthy People

33

creates a

roadmap for achieving population health

goals through interventions in a variety of

non-health and health arenas. Achieving

the goal of reducing childhood obesity, for

example, will require changes outside the

health system, such as removing junk food

from schools and taxing sodas. The Commis-

sion to Build a Healthier America, convened

by the Robert Wood Johnson Founda-

tion, recently concluded that achieving the

goal of a healthy nation will require broad

changes “in every aspect of society and daily

life.” The Commission recommendations

focused on improving early childhood health

and development, encouraging good nutri-

tion and promoting healthy communities.

34

APHA’s work to improve the health of the

nation supports changes in the workplace, in

schools and in the environment, in addition

to changes in the health system. For example,

APHA has outlined five general goals and 27

specific goals across non-health and health

sectors to reduce childhood obesity. The Pre-

vention Institute has documented the impact

of community violence on healthy eating

and activity.

35

Each of these efforts supports the intent of

addressing poor health outcomes by reaching

beyond the traditional “health care system”

of doctors, nurses and hospitals; instead, they

involve coaching (from parents and educa-

tors) about a range of things including nutri-

tion, exercise, activities; and systemic changes

to our environments.

III. Preventive Health

Provisions in the

Affordable Care Act

The Affordable Care Act addresses poor

health outcomes in a number of ways, such

as improving access to care, making care

and coverage more affordable, encouraging

preventive care, and increasing the supply of

primary care providers. Congress recognized

the need to address population health com-

prehensively, both within the health system

and through initiatives that extend to other

sectors, such as the school system.

The Affordable Care Act includes a broad

range of initiatives designed to promote

wellness and prevent disease. The prevention

provisions in the Affordable Care Act require

large implementation roles for federal, state

and local governments and the private sector.

While phased in over time, implementation

timelines are tight. Many involve multiple

divisions within the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services. Stakeholders in

the health care system—patients, consumers,

doctors, nurses, insurance companies, hospi-

tals, employers, and government employees

at the federal, state and local levels—will

all face major changes in how they interact

with the health system. For example, the

Affordable Care Act provides grants to state

and local health departments to educate

targeted populations, build the public health

infrastructure, prevent chronic disease, and

foster healthy and safe communities through

policy, systems, and environmental changes.

A second category of initiatives—public

education campaigns—are designed to pro-

mote healthy behaviors (e.g., good nutrition,

adequate exercise) and discourage unhealthy

behaviors (e.g., tobacco use). A third cat-

egory tests new approaches to improving

health, evaluates the effectiveness of these

approaches, and expands successful efforts

over time to promote healthy behavior and

healthy outcomes. Finally, a fourth category

of initiatives involves insurance coverage

requirements that are designed to assure that

various populations (e.g., Medicare benefi-

ciaries, people with private insurance cover-

age) do not face financial barriers to access-

ing evidence-based preventive care such as

cancer screenings.

In this issue brief the provisions of the

Affordable Care Act are grouped into four

categories:

investing in public health through grant

programs, contracts, support and infra-

structure that will develop a national

prevention, health promotion and pub-

lic health strategy, and coordinate federal

programs;

educating the public through educational

campaigns aimed at improving health;

learning from experience through re-

search and demonstrations; and

requiring that evidence-based preventive

health care services be covered in both

T

he Affordable Care

Act addresses this

fragmentation and

lack of coordination through

two initiatives: (1) the National

Prevention, Health Promotion

and Public Health Council,

which will coordinate and

execute a comprehensive

strategy; and (2) the Preven-

tion and Public Health Fund,

which will invest in prevention

and public health programs

to improve health and restrain

health costs.

7

public and private health coverage, with-

out cost-sharing.

A. Investments In PublIc HeAltH

The United States dedicates a mere 3

percent of its healthcare budget to disease

prevention and public health.

36

These funds

are administered across multiple federal, state

and local agencies, with no loci of coordina-

tion and review.

The Affordable Care Act addresses this

fragmentation and lack of coordination

through two initiatives: (1) the National

Prevention, Health Promotion and Public

Health Council, which will coordinate and

execute a comprehensive strategy; and (2)

the Prevention and Public Health Fund,

which will invest in prevention and pub-

lic health programs to improve health and

restrain health costs.

National Prevention, Health Promotion

and Public Health Council

38

(Section 4001,

10401): The law creates a new Council,

within HHS, to coordinate and lead the

federal government’s efforts on prevention,

wellness and health promotion, and estab-

lishes a locus of control, multi-sector coor-

dination, and accountability for advancing a

national prevention agenda. The Council is

to be chaired by the U.S. Surgeon General

and will consist of Secretaries of appropri-

ate federal departments (e.g., Health and

Human Services, Agriculture, Education,

Homeland Security, Transportation, Labor),

the Chairman of the Federal Trade Com-

mission, the Director of the Domestic Policy

Council, several other senior administration

appointees, and other members as deter-

mined appropriate.

38

The Council is charged

with making policy recommendations to the

President and Congress to advance public

health goals. It is to consider and propose

“evidence-based models, policies, and in-

novative approaches for the promotion of

transformative models of prevention, integra-

tive health, and public health on individual

and community levels across the United

States.”

A key function of the Chairperson (in

consultation with the Council) is to “de-

velop and make public a national prevention,

health promotion, public health strategy,”

within one year of enactment. The strategy

must articulate specific goals and objectives

for improving the health status of Ameri-

cans through federal health promotion and

prevention programs. It is to include “spe-

cific and measurable actions and timelines”

to implement the strategy. An annual report

to the President and relevant committees

of Congress will provide a forum for the

Council to describe activities on preven-

tion, health promotion and public health,

report on progress in meeting the goals of

Healthy People 2020, and report on the status

of federal coordination of programs. The

first report was issued on July 1, 2010. (See

Section V.)

Prevention and Public Health Fund (Sec-

tions 4002, 10401): While the National

Prevention, Health Promotion and Public

Health Council provides a mechanism to

coordinate federal programs, the new Pre-

vention and Public Health Fund provides

the resources to fund prevention and public

health initiatives. The Fund is intended “to

provide for expanded and sustained national

investment in prevention and public health

programs to improve health and help restrain

the rate of growth in private and public

health care costs.” The law provides $500

million for the Fund in FY2010, and annual

A

ffordable Care Act provides grants to state and local health depart-

ments to educate targeted populations, build the public health

infrastructure, prevent chronic disease, and foster healthy and safe

communities through policy, systems, and environmental changes.

8

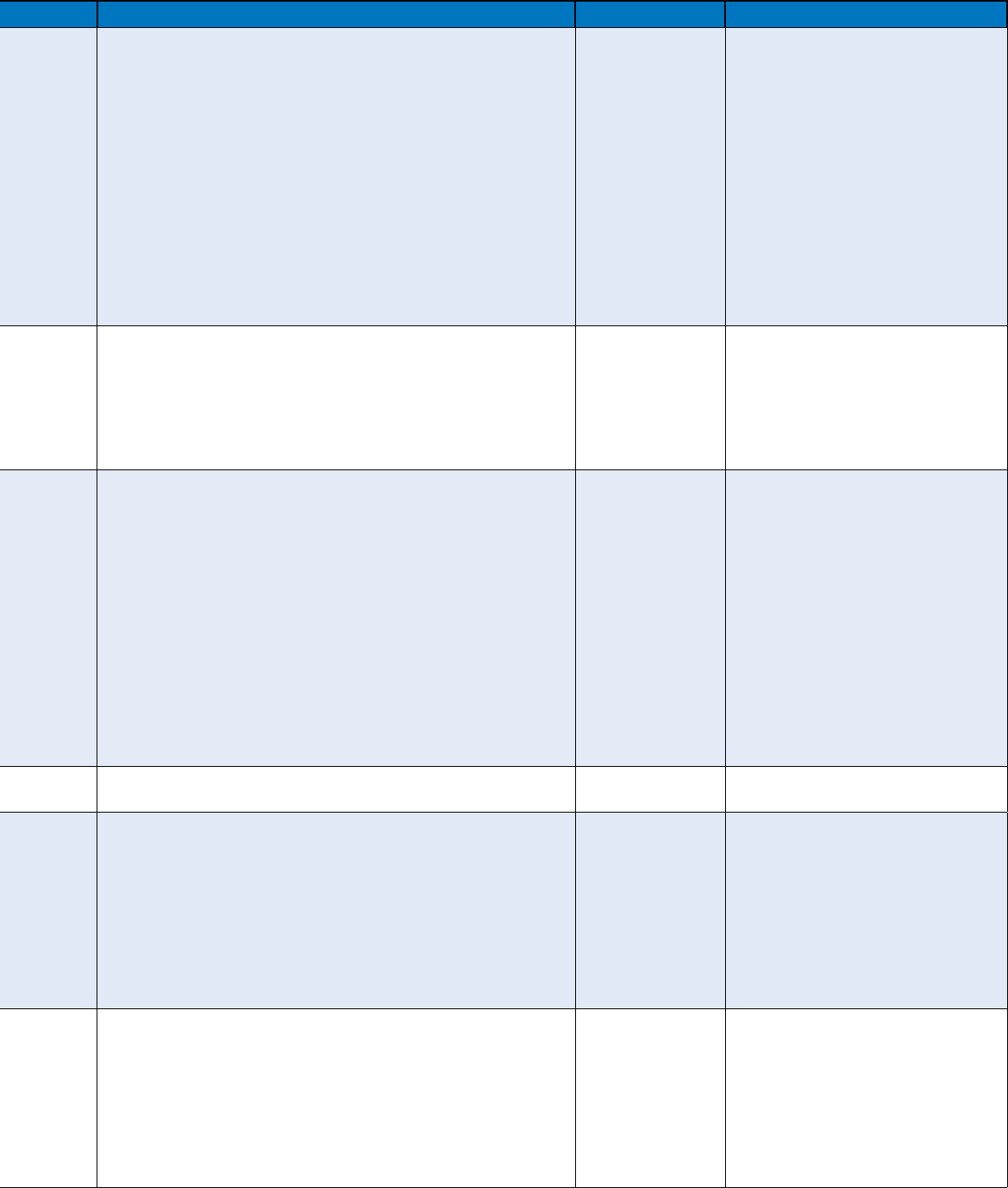

Table 1: Grant Programs to Promote Prevention

41

School-based Health Centers (Section 4101)

The Secretary of HHS will establish a grant program “to support the operation of school-based Health Centers”

grants for schools, preference to those with large number of children eligible for Medicaid

funds to support facilities and equipment, not to support personnel or pay for health services

Secretary is to develop evaluation plan and monitor quality performance of grants

appropriates $50 million per year for FY2010 to FY2013

Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Disease in Medicaid (Section 4108)

The Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will award grants to states to carry out comprehensive, evidence-based, accessible programs

to lower health risks of Medicaid beneficiaries

funds can be used, for example, for programs to cease use of tobacco products, control or reduce weight, lower cholesterol, lower blood pressure, avoid

onset of diabetes

requires various reports from states receiving grants, independent evaluation of initiatives, reports from Secretary to Congress

appropriates $100,000,000 for the five-year period beginning January 1, 2011

Community Transformation Grants (Section 4201)*

The Secretary of HHS, through the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), to award grants “for the implementation, evaluation, and

dissemination of evidence-based community preventive health activities in order to reduce chronic disease rates, prevent the development of secondary conditions,

address health disparities, and develop a stronger evidence-base of effective prevention programming”

competitive grants to state and local governmental agencies, community-based organizations, non-profit organizations, and Indian tribes for implementation,

evaluation and dissemination of evidence-based community preventive health care activities

grant recipients to provide detailed plan for the policy, environmental, programmatic and (as appropriate) infrastructure changes needed to promote healthy

living and reduce disparities

activities could include: creating healthier school environments, creating infrastructure to support active living, access to nutritious food, and tobacco

cessation

grant recipients are to evaluate impact by measuring the changes in prevalence of chronic disease risk factors of community members participating in

preventive health activities

grantees will meet at least annually to discuss challenges, best practices, and lessons learned

does not specify an amount to be appropriated (authorizes “sums as may be necessary”)

Health Aging, Living Well (Section 4202)

42

*

Secretary of HHS (through the Director of the CDC) will award grants to states, local health departments and Indian tribes:

to carry out 5-year pilot programs to provide public health community interventions, screenings, and where necessary clinical referrals for individuals who

are between 55 and 64;

interventions include efforts to improve nutrition, increase physical activity, reduce tobacco use and substance abuse, improve mental health, and promote

healthy lifestyle

grant applicants to design a strategy to improve the health of individuals between ages 55 and 64 through community-based public health interventions;

does not specific an amount to be appropriated (authorizes “sums as may be necessary”)

Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity Grant Program (Section 4304)*

The Secretary of HHS (through the CDC Director) to establish a grant program to provide:

grants to state health departments, local health departments, tribal jurisdictions, and academic centers

funding for assisting public health agencies in improving surveillance for, and response to, infectious diseases and other important public health conditions

authorizes $190,000,000 for each year between FY2010 and FY2013

Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Programs (Section 2951)

The Secretary of HHS will award grants to states, Indian tribes, and (in certain circumstances) non-profit organizations:

to fund early childhood home visitation programs;

each grantee is to measure benchmarks including maternal and newborn health, prevention of child injuries, improvement in school readiness, reduction

in crime or domestic violence;

Appropriates $100 million in FY2010, increasing steadily until FY2014 when appropriations are $400,000.

*Funds have not been appropriated for these grant programs, and they will not be implemented in the absence of future appropriations.

9

T

he prevalence of

largely preventable

diseases such as

heart disease, cancer and

diabetes has increased in

the United States. Congress

recognized the potential to

improve population health by

addressing these preventable

diseases through broad-based

public education campaigns,

and included them as a corner-

stone of reform.

authorizations increase, with total authoriza-

tions of $15 billion for FY2010 to FY2019.

The Fund is administered by the Secretary

of the Department of Health and Human

Services (HHS).

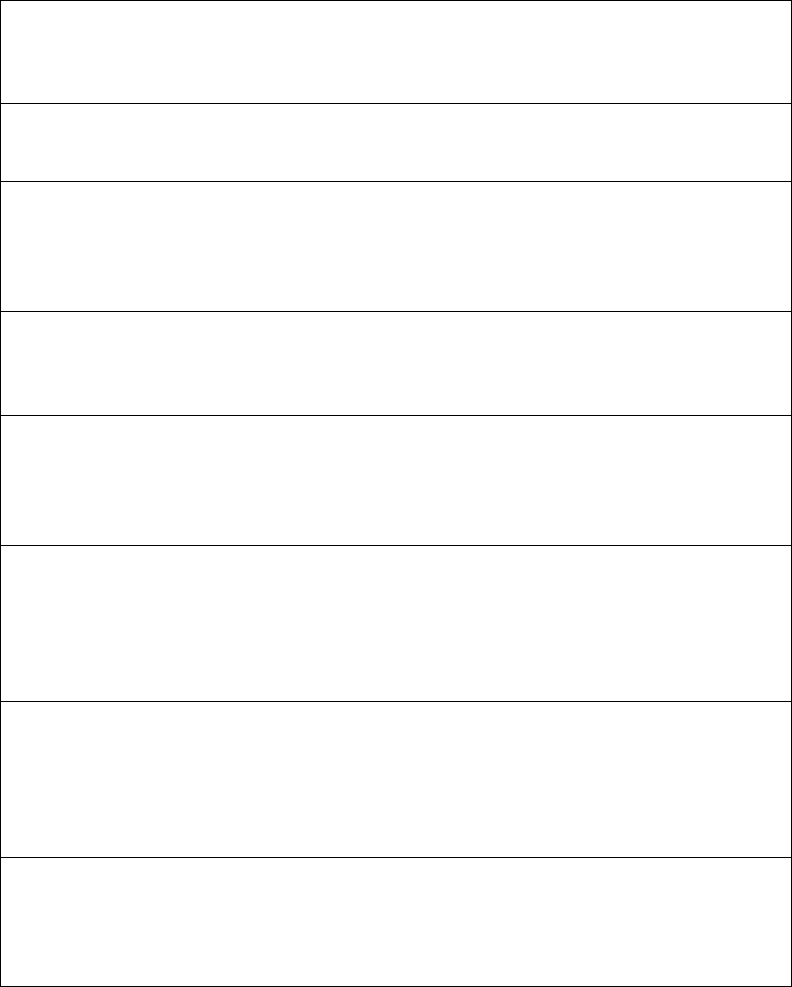

Table 1 summarizes the five major preven-

tion programs to be funded by the health

reform law, to be administered by the Secre-

tary of the HHS. The programs include:

support for the operation and expansion

of school-based health centers;

state programs to help lower health risks

of Medicaid beneficiaries;

state, local, and other organization proj-

ects to fund implementation, evaluation

and dissemination of preventive health

activities through enhancing infrastructure

and capacity (community transformation

grants);

state, local and Indian tribe pilot programs

to provide public health community in-

terventions for individuals between ages

55 and 64 (e.g., increasing physical activity

of 64-year-olds);

grants to state, local and tribal health

departments and academic centers to in-

crease surveillance and response to emerg-

ing public health issues, including infec-

tious disease (epidemiology and laboratory

capacity grant program); and

grants to state and tribal organizations, and

under certain circumstances non-profit

organizations, to provide early childhood

home visitation programs, with a require-

ment that at least 75% of the funding be

used for programs using evidence-based

models.

Each of these grant programs provides

an opportunity to address health disparities

that result in disproportionate adverse health

conditions for specific groups in the United

States.

39

The health reform law also provides

support at a more modest funding level

for important but smaller-scale preventive

programs. It provides for technical assis-

tance, through the Director of the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention, for

employer-based wellness programs (Sec-

tion 4303). For example, it provides tools

for measuring participation in workplace

wellness programs, methods for increasing

participation, and assistance for determining

the impact on participants’ health status.

41

The Act authorizes $500 million to fund the

public education campaigns of the Secretary

(described below in the next section). It au-

thorizes the Secretary of HHS to negotiate

contracts with manufacturers for vaccines,

and supports a demonstration program to

improve immunization coverage and grants

to states to increase rates for recommended

immunizations for children, adolescents and

adults (Section 4204).

b. PublIc educAtIon cAmPAIgns

As described above (Section II), the

prevalence of largely preventable diseases

such as heart disease, cancer and diabetes

has increased in the United States. Congress

recognized the potential to improve popula-

tion health by addressing these preventable

diseases through broad-based public edu-

cation campaigns, and included them as a

cornerstone of reform. The Act establishes

a well-funded “education and outreach

campaign” on preventive services that will

be included in health coverage for most

people. The public education campaigns aim

to dramatically alter behaviors that result in

60 percent of deaths attributed to “social or

behavioral circumstances” as described in the

Problem section above.

43

The Secretary of HHS is charged with

planning and implementing a national

public-private partnership that will focus on

educating the nation’s diverse population

about disease prevention and health promo-

tion. The campaign will provide information

about the importance of using evidence-

Restaurants will be required to include the nutrient content and the number of calories in food selections

on their menus, and must make additional nutritional information available upon request. In addition,

vending machine operators who own more than 20 machines are required to post signs disclosing the

number of calories in each item sold

10

based preventive services “to promote well-

ness, reduce health disparities and mitigate

chronic disease.”

44

The campaign may use

TV, radio, a Web site, and other venues to

address lifestyle choice related to appropri-

ate and adequate nutrition, exercise, tobacco

cessation and obesity reduction. The five

leading disease killers in the United States

(heart disease, cancer, stroke, respiratory

disease and Alzheimer’s disease in 2007) will

also be targeted in a public education cam-

paign, and will include an educational Web

site that includes information for health care

providers and for consumers.

A second public education campaign is to

be carried out by a non-traditional source

of health information: restaurants that are

part of a chain with 20 or more locations.

Restaurants will be required to include the

nutrient content and the number of calories

in food selections on their menus, and must

make additional nutritional information

available upon request. In addition, vending

machine operators who own more than 20

machines are required to post signs disclos-

ing the number of calories in each item sold.

The third education initiative establishes a

five-year, national public educational cam-

paign on oral health care and the prevention

of oral disease. This campaign will target

activities to children, pregnant women, the

elderly, individuals with disabilities, and

ethnic and racial minority populations. It

will convey oral health prevention messages,

including education about the importance

of community water fluoridation and dental

sealants to encourage broader provision and

use of routine dental services. This campaign

is authorized, and will be implemented only

if funds are appropriated. Section 1302 of the

Affordable Care Act specifies that oral health

services are to be included in the basic ben-

efits for children (but not adults).

c. coverIng recommended

PreventIve servIces As A HeAltH

benefIt

There are several reasons that preventive

services have not been included in health

insurance policies until recently. The relative

predictability of the cost of recommended

preventive services makes them different

(from an insurance perspective) from low-

probability illnesses and injuries that health

insurance was initially designed to cover.

Health insurance was originally designed to

be more “catastrophic” rather than “first-

dollar coverage”. Insurers would argue

that including preventive benefits simply

increased premiums to cover the expected

cost of the benefits. Additionally, health plans

and employers have little incentive to cover

preventive services that are more likely to

have an impact on a member’s or employee’s

long-term health and well-being, because

the employee might have left the employer

by the time the preventive services pay off.

However, increased employer and con-

sumer demand for coverage of services

which prevent disease and disability over the

long term, in conjunction with the evidence

of value and effectiveness, led to the change

in insurance coverage in recent years. The

scientific understanding of which preventive

services are appropriate at different stages

of life increased, with the help of the U.S.

Preventive Services Task Force. Insurers have

responded to employers’ and consumers’ de-

mand for coverage of preventive services in

otherwise high deductible health insurance

policies: 92 percent of high deductible plans

offered by employers included preventive

care without any deductible in 2009.

45

A

PHA recommended first-dollar coverage for evidence-based

clinical preventive services in its Agenda for Health Reform.47 And

in fact, the new health reform law requires that health benefits in-

clude selected preventive services with no cost-sharing both for individual and

group plans and for Medicare.

11

At the same time, there is growing aware-

ness that cost-sharing (e.g., co-payments,

deductibles) presents a financial barrier that

deters people from getting the screenings

and preventive services that are recommend-

ed for them. The continuing recession has

resulted in cutting back on routine care such

as preventive services, most likely because

of the large out-of-pocket costs involved.

46

While most employer plans include preven-

tive care without cost-sharing, individual

policies (under competitive pressure to keep

premiums low) are unlikely to do so in the

absence of a legal requirement.

Recognizing the importance of elimi-

nating financial barriers to receiving

evidence-based preventive services, APHA

recommended first-dollar coverage for

evidence-based clinical preventive services

in its Agenda for Health Reform.

47

And in

fact, the new health reform law requires

that health benefits include selected preven-

tive services with no cost-sharing both for

individual and group plans and for Medicare.

These new benefits will be required by late

2010 (six months after enactment) for indi-

viduals with new private coverage, and by

January 1, 2011, for Medicare beneficiaries.

States are encouraged to extend preventive

health services in their Medicaid programs,

paid for in large part by increased federal

payments for Medicaid.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force,

an independent panel of experts in primary

care and prevention, is based at the Agency

for Healthcare Research and Quality. Its rec-

ommendations provide the basis for preven-

tive services coverage. Specific recommenda-

tions vary by age and other factors, and the

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recom-

mends that clinicians discuss the recom-

mended preventive services with patients as

appropriate. Examples of the services recom-

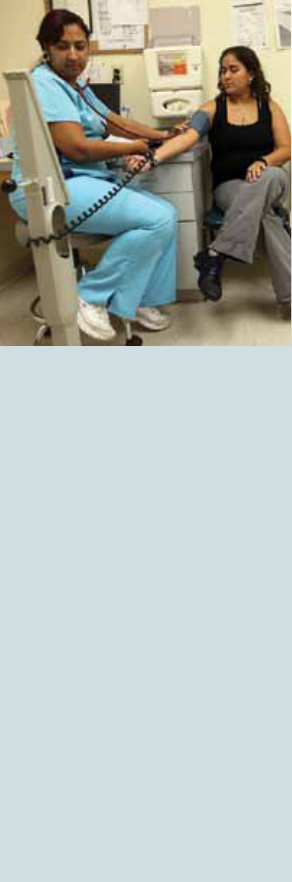

mended for adult women include screening

for breast cancer, cervical cancer, colorectal

cancer, depression, high blood pressure and

obesity.

48

Private plans: For private plans, cover-

age will be required in new plans for all

evidence-based preventive services that are

rated “A” or “B” by the U.S. Preventive

Services Task Force (Section 1001). Cost-

Table 2: Preventive Care and Public Health Research Projects

53

Individualized Wellness Plans (Sec. 4206)

Goal: Test impact of providing at-risk populations an individualized wellness plan designed to reduce risk of preventable conditions. Wellness plans would

include plans for nutritional counseling, physical activity, alcohol and tobacco cessation counseling, stress management.

Target population: At-risk individuals who use community health centers.

Implementation: Secretary of HHS to identify 10 community health centers to conduct evaluation.

Delivery of Public Health Services (Sec. 4301)

Goal: Evaluate (and report to Congress) the effectiveness of evidence-based practices relating to prevention and community-based public health interventions,

and identify effective strategies for state and local systems to organize, finance and deliver public health services.

Target population: Communities and populations that would benefit from prevention priorities identified by the National Prevention Strategy and Health

People 2020.

Implementation: The Secretary of HHS, working with the CDC, Community Preventive Services Task Force, and various private and public partners, will analyze

and report annually to Congress.

Evaluation of Community-based Prevention and Wellness Programs (Sec. 4202)

Goal: Evaluate the ability of community health interventions to improve the health of people nearing Medicare eligibility and the effectiveness of community-based

prevention and wellness programs for Medicare beneficiaries.

Target Population: People nearing Medicare eligibility (55 to 64 years old) and Medicare beneficiaries.

Implementation: The Secretary of HHS, working with the CDC and the Administration on Aging, will provide grants for the pilot study of people nearing

Medicare eligibility. The Secretary of HHS will evaluate the programs for Medicare beneficiaries.

12

sharing (i.e., deductibles and co-payments)

is explicitly prohibited. Similarly, immuniza-

tions that are recommended by the Advisory

Committee on Immunization Practices and

“evidence-informed preventive care and

screenings” for infants, children and adoles-

cents, and breast cancer screening mammog-

raphy are covered (Section 1001).

Medicare: Cost-sharing will be elimi-

nated for Medicare beneficiaries for preven-

tive services (including colorectal cancer

screening) that are rated “A” or “B” by the

Task Force.

49

Medicare beneficiaries will be

covered for an annual wellness visit. Before

the visit, beneficiaries will receive support to

help them complete a health risk assessment.

Each beneficiary will be provided with a

personalized prevention plan that includes a

health risk assessment, the establishment or

update of an individual medical and fam-

ily history, personalized health advice, and,

when appropriate, referral to health educa-

tion or preventive counseling services. Even

if recommended, health education services

are generally not covered by Medicare, with

the exception of medical nutrition therapy

for people with diabetes or kidney disease,

and diabetes education for those with diabe-

tes; outpatient mental health counseling will

continue to be covered with a 45 percent

coinsurance rate in 2010–2014.

50

Medicaid: The health reform law encour-

ages, but does not require, states to expand

preventive coverage for Medicaid ben-

eficiaries. It adds preventive services rated

“A” or “B” by the U.S. Preventive Services

Task Force and vaccines recommended by

the Advisory Committee on Immuniza-

tion Practices to the list of services that state

Medicaid programs can cover, and encour-

ages states to do so by increasing the federal

financial contribution (federal medical assis-

tance percentage, or FMAP) by 1 percent for

any states that cover these services without

any cost-sharing (Section 4106). Pregnant

women covered by Medicaid will have cov-

erage for counseling and prescription drugs

for cessation of tobacco use (Section 4107).

d. demonstrAtIon ProgrAms And

reseArcH Projects

The health reform law uses evidence of

effectiveness to make decisions and fund

educational programs. New programs will

be evaluated and adjusted based on effective-

ness evidence. The law includes a number

of research and demonstration programs

designed to improve capacity to promote

prevention and public health in the future.

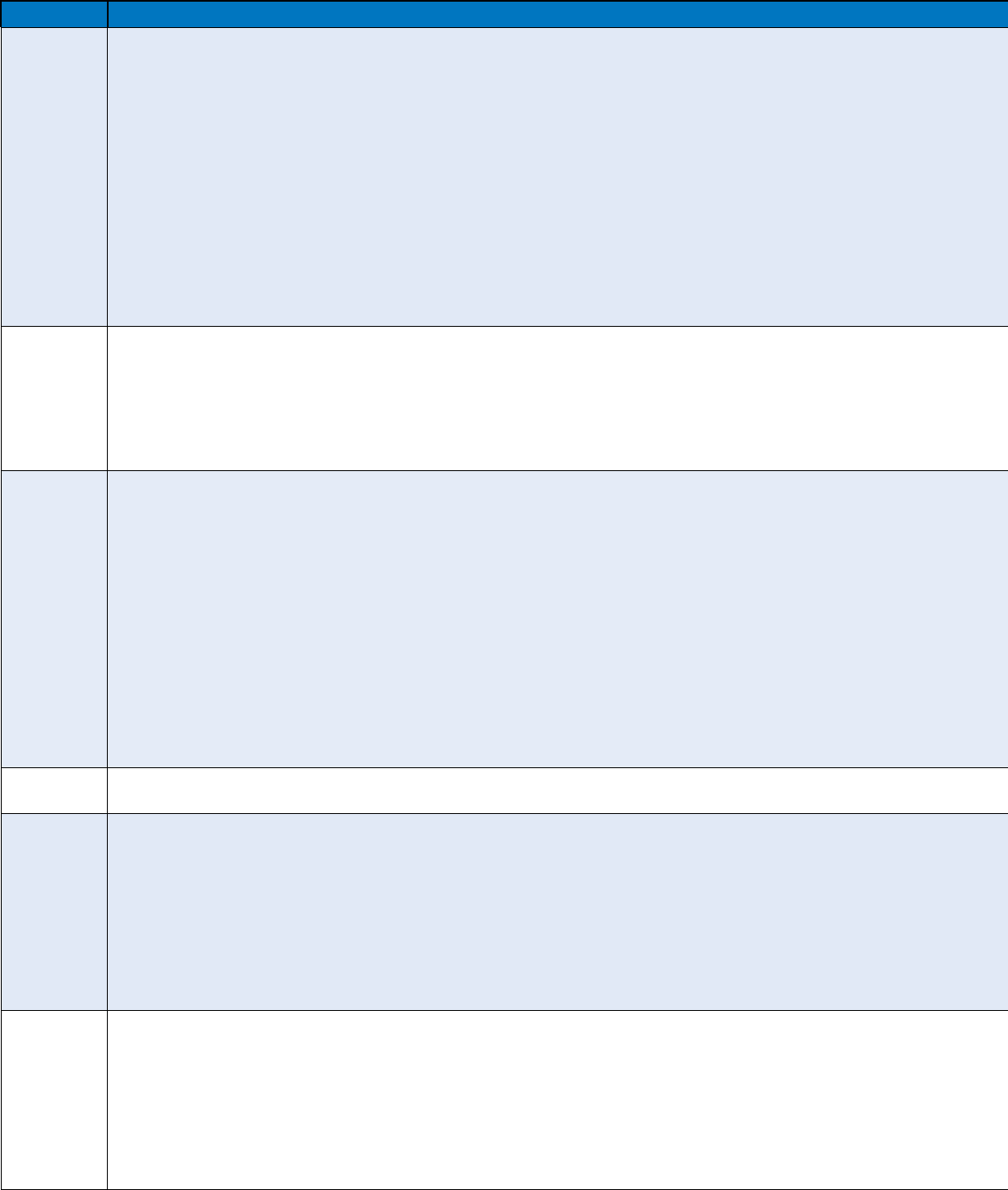

There are three major prevention-oriented

research projects in the health reform law:

(1) a demonstration project for individual-

ized wellness plans developed for individu-

als at risk of preventable conditions; (2) a

comparative analysis of effectiveness and

cost of public health interventions; and (3)

an analysis of community-based prevention

and wellness programs for the population

nearing Medicare eligibility and for Medi-

care beneficiaries. These three programs are

summarized in Table 2.

In addition, the health reform law has a

number of provisions aimed at improving

the understanding of prevention-related ac-

tivities, in concert with the needs of various

population groups. Other evaluation-orient-

ed provisions of the law include:

1. a requirement that all federal surveys col-

lect data on race, ethnicity, sex, primary

language and disability status (Section

4302);

2. the convening of a conference, through

the Institute of Medicine, that explores

many facets of pain management, includ-

ing how specific races, genders and ages

are affected, and reports to Congress (Sec-

tion 4305);

3. appropriation of funds for a previously

authorized Childhood Obesity Demon-

stration project52 (Section 4306);

4. development of methodologies for esti-

mating the budget impact of prevention

and wellness programs (since benefits of-

ten accrue beyond a 10-year budget win-

dow) by the Congressional Budget Office

(Section 4401);

5. an analysis of the impact of health and

wellness initiatives on the health status

(e.g., absenteeism, productivity) of the

federal workforce (Section 4402);

6. review of the scientific evidence of

effectiveness, appropriateness, and cost-

effectiveness of clinical preventive services

by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force,

and publication of the findings in the

S

hortages in the

primary care health

workforce, espe-

cially in underserved areas,

will grow more intense as

the number of insured adults

grows. This will require early

and aggressive attention so

that the expanded access to

care does not result in long

waiting lines at doctors’ of-

fices and clinics.

13

Guide to Clinical Preventive Services (Sec-

tion 4003);

523

and

7. review of the effectiveness, appropriate-

ness and cost-effectiveness of community

preventive interventions (including health

impact assessments and population health

modeling) and publication of recommen-

dations in the Guide to Preventive Services

by the independent Community Preven-

tive Services Task Force (Section 4003)

IV. Some Key Issues

Transforming our nation’s health system

to one that promotes health and wellness in

the first place is an iterative process, one that

requires routine assessment, evaluation and

adjustments over time. The scope of prob-

lems addressed by the legislation is ambitious

and broad, and cuts across many sectors of

the economy and across disciplines/sectors.

The ambiguity about authorizations and

appropriations ensures that there will be

scrutiny by Congress with input from many

stakeholders, and that there will be uncer-

tainty on the part of implementing agencies

about precise funding streams. Early imple-

mentation efforts are occurring at a time of

fiscal crisis in virtually all states, making it

especially difficult for state and local gov-

ernments to continue to provide existing

services at the same time that they ramp up

comprehensive health reform implementa-

tion activities. Shortages in the primary care

health workforce, especially in underserved

areas, will grow more intense as the number

of insured adults grows. This will require

early and aggressive attention so that the ex-

panded access to care does not result in long

waiting lines at doctors’ offices and clinics.

There are a number of factors that will

influence the ultimate impact of the preven-

tive provisions. First and foremost is the state

of the economy and pace of the recovery.

This directly influences the ability of state

and local governments to fund a depleted

public health workforce. Without a signifi-

cant improvement, state and local govern-

ments will be able to do little more than

hold steady, perhaps even facing further ero-

sion of their public health infrastructure and

programs. A second key factor is the need for

prevention and public health advocates to

coordinate their efforts in order to maximize

their influence in bringing about change.

More significantly, success in altering the

course of the public’s health and its grow-

ing prevalence of obesity requires substantial

lifestyle changes by individuals, communi-

ties, businesses and governments. This is a

long and arduous road, and while the United

States has made advances in many areas, we

will need comprehensive policies to support

environmental change.

The following section summarizes some

of the implementation challenges facing the

federal, state and local governments as they

implement the Affordable Care Act.

Deployment of the Prevention and

Public Health Fund: Never before has the

government invested such a large amount

of money—$15 billion over the next 10

years—in prevention through a single fund-

ing stream. The harsh reality is, however, that

the amount of money authorized is not as

large as the need. Tough choices lay ahead

to ensure that the investment successfully

“[transforms] our health system into one

that truly promotes health, not just disease

treatment.”

54

It will have a greater chance

of success if the funding represents a new

investment rather than supplants existing

prevention and public health funding.

55

One implementation issue that arose early,

with the Administration’s announcement of

how to deploy the $500 million appropriat-

ed for Fiscal Year 2010, is whether funds tar-

geted for prevention and public health could

be diverted to fund other priorities. On June

18, 2010, the Department of Health and

Human Services announced that it would

spend $250 million (half of the appropriated

funding for the year) on a one-time invest-

ment in the primary care workforce. The

other $250 million was spent on community

and clinical prevention ($126 million), the

public health infrastructure ($70 million),

research and tracking ($31 million) and

public health training ($23 million).

56

APHA

was part of a group of 90 organizations that

urged the Administration to allocate the

entire $500 million, not just $250 million,

to public health issues, not the primary

care workforce.

57

The allocation process for

the Prevention and Public Health Funds is

expected to receive increased scrutiny by

Definition

of Health

Disparities

70

“

…the difference in the

incidence, prevalence,

mortality and burden

of disease and other adverse

health conditions that exist

among specific groups in the

United States.”

14

congressional appropriations committees in

future years.

58

Assuming future Fund allocations are

entirely devoted to prevention and public

health workforce training, there will still be

difficult decisions about how to allocate the

funds among different public health initia-

tives (e.g., tobacco cessation, nutrition, physi-

cal activity), the public health infrastructure,

research and tracking, and public health

workforce training. Transparent reporting of

funding allocations, evaluation and strategic

planning is required by both the National

Health Prevention, Health Promotion and

Public Health Council and the Secretary of

the Department of Health and Human Ser-

vices. Ideally, the investment will be lever-

aged through careful coordination with state,

local and private resources and reflect the

best evidence on efficacy to have maximum

impact.

59

An amendment (to the Small Business Jobs

and Credit Act) by Senator Mike Johanns

in late summer of 2010 was the first official

congressional threat to the Prevention and

Public Health Fund. This amendment would

have repealed a provision of the Affordable

Care Act designed to raise new revenue by

decreasing non-compliance with tax laws. It

would have been funded by eliminating the

Prevention and Public Health Fund from fis-

cal year 2010 to fiscal year 2017. APHA and

other organizations opposed the amendment

and it was defeated.

60

Increased pressure to

reduce the federal deficit during the 112th

Congress is likely to result in legislative pro-

posals to cut the Fund. Preserving the Fund

as created by the Affordable Care Act will

require vigilance and coordinated strate-

gic efforts by public health and prevention

advocates. It will be important to remind

lawmakers of the economic case for preven-

tion, with an estimated $5.60 of health cost

savings for every $1 spent on certain preven-

tion initiatives.

61

Role of the National Prevention, Health

Promotion, and Public Health Council. The

White House released an Executive Order

on June 10, 2010, officially establishing the

National Prevention, Health Promotion, and

Public Health Council.

62

On July 1, 2010,

the Surgeon General released the Council’s

first annual status report.

63

The Council

is charged with coordinating and leading

the work on the federal level with respect

to prevention, wellness, health promotion,

public health system, and integrative health

care. In addition, it is to develop a broad-

ranging “national prevention, health pro-

motion, public and integrative health-care

strategy,” and make recommendations to the

President and Congress regarding tobacco

use, sedentary behavior and poor nutrition.

The Council is well-positioned to build

on the work of Healthy People 2010 and

Healthy People 2020, and has the authority

to coordinate the work of various federal

agencies in a way that is more transparent

and accountable to the public, the Adminis-

tration and Congress. The first annual report

acknowledges the importance of leading and

coordinating federal efforts on prevention.

That role will continue into the future even

after the strategy is completed and released

to the public early in 2011.

The Council’s first status report notes

the significance of its taking “a community

health approach to prevention and wellness”

and of the requirement that its recommen-

dations be grounded in science-based pre-

vention recommendations and guidelines.

64

The Council’s report reflects an understand-

ing of the need for actions, interventions and

policies that go beyond the health system

to address problems in schools, transporta-

tion and education. The report expands on

how it will determine whether interventions

are effective, listing five major strategies for

public health interventions. They are:

65

Policy: supporting policies that promote

prevention, create healthy environments,

and foster healthy behaviors (e.g., remov-

ing barriers to safe and convenient walk-

ing and bicycling).

Systems change: establishing policies

that support healthy behaviors (e.g., es-

tablish patient registries, appointment and

medication reminder systems, and incen-

tives to help monitor and control high

blood pressure and high cholesterol).

Environment: creating social and physi-

cal environments that support healthy lives

and choices (e.g., improve access to fresh

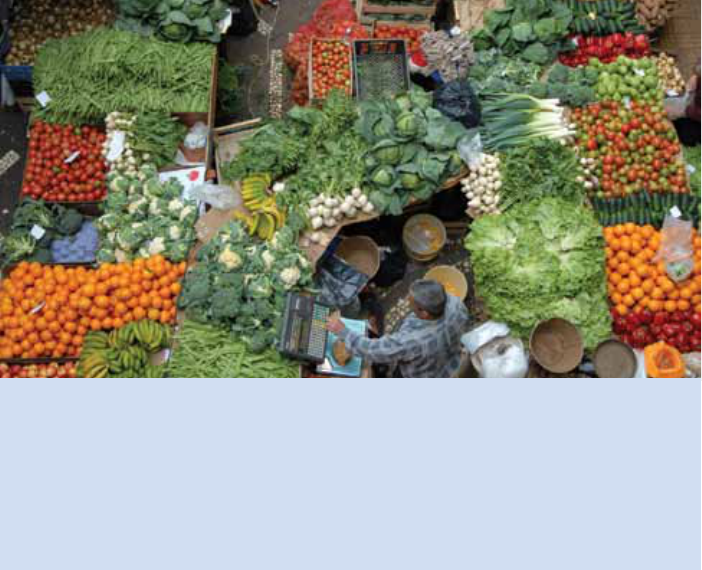

fruits and vegetables in at-risk urban and

underserved communities).

N

ational Prevention,

Health Promotion,

and Public Health

Council is to develop a broad-

ranging “national prevention,

health promotion, public and

integrative health-care strat-

egy,” and make recommen-

dations to the President and

Congress regarding tobacco

use, sedentary behavior and

poor nutrition.

15

Communications and media: Sup-

porting healthy choices and raising

health awareness, especially among

those who experience health dis-

parities, through interactive, social and

mass media (e.g., inform consumers

about options for accessing and pre-

paring healthy and affordable foods).

Program and Service Delivery:

Designing prevention programs and

services to contribute to wellness (e.g.,

provide safe and affordable opportuni-

ties for physical activity in schools).

Implementation Issues at Various

Government Entities: As noted above,

the National Prevention, Health Pro-

motion and Public Health Council will

coordinate federal prevention and public

health initiatives. The Secretary of HHS,

and agencies such as CDC, HRSA, and

AHRQ are responsible for specific initia-

tives of varying scope and complexity,

including hundreds of reports, and strate-

gic decisions on a myriad of issues such

as what criteria to use in awarding grants

to state and local governments for various

programs.

66

Each entity will face a set of

implementation challenges in balancing

research, grant-making, public education

and congressional reporting deadlines.

For example, the timing of the funding

will impact implementation. Further-

more, specific awards will receive media

scrutiny and pushback from stakeholders

who may disagree. These pressures make

it crucial that the leaders of the imple-

mentation effort, both in the Office of

the Secretary and at each implementing

agency, build highly skilled staff to lead

the implementation efforts, including staff

with proven project management skills

and expertise in the communication of

findings, recommendations and programs

to the public in an accessible and trans-

parent manner.

Efficient Use of State and Local

Resources: Implementation of the health

reform law is beginning at a time of

strains and restrictions on the budgets of

state and local governments. According

to the National Association of County

and City Health Officials, the recession

has forced state and local governments

to reduce their overall workforces by 15

percent, cutting 23,000 staff, many of

whom protect health and provide safety.

It would take tens of billions of dollars

to replace the lost staff, and the money

provided in the Affordable Care Act will

not be sufficient to restore the services

that these employees provided.

67

So while

state and local governments will mobilize

to respond to the many new grant op-

portunities, they will do so in the context

of a depleted health and public health

workforce. This will make it difficult to

create and sustain efficiencies around the

new prevention and public health op-

portunities. It will be especially difficult

for implementation efforts to reach their

full potential at the state and local levels

during the prolonged weak economy.

The states have major implementation

responsibilities, including administering

expanded Medicaid programs, revising

state high-risk pool programs, establishing

and regulating health insurance ex-

changes, and regulating and policing the

health insurance marketplace. In addition,

they are eligible to apply for grants, for

example, to help them monitor premium

increases, participate in personal respon-

P

ublic Health Council’s intervention is creating social and physical

environments that support healthy lives and choices (e.g., improve

access to fresh fruits and vegetables in at-risk urban and under-

served communities).

16

sibility education programs, and establish

insurance exchanges.

States already have established the State

Consortium on Health Care Reform, con-

sisting of the National Governors Associa-

tion, the National Association of Insurance

Commissioners, the National Association of

State Medicaid Directors, and the National

Academy for State Health Policy. Individual

states have set up organizational structures.

For example, California has established

the Health Care Reform Task Force, and

Colorado has appointed a Director of Health

Reform Implementation and an Interagency

Health Reform Implementing Board.

68

Additionally, 13 states have jointly filed

a lawsuit contending that the individual

mandate provision violates the Constitution.

The outcome of this lawsuit, and its impact

on implementation actions of these states,

threatens to delay or even derail the abil-

ity of the Affordable Care Act to meet its

potential.

69

Lessons learned from the American

Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

(ARRA). The implementation experience

with the ARRA offers some lessons for

consideration as the Affordable Care Act

is implemented. Dr. Paul Jarris, Executive

Director of the Association of State and Ter-

ritorial Health Officials (ASTHO), contends

that that the ARRA prevention funds, which

were distributed as two-year grants, were

disseminated to high-capacity proven entities

with “ready-to-go” programs. They were

allocated, in large part, to big, sophisticated

organizations, with the hope that positive

results could be demonstrated more clearly.

But to reach underserved and rural popula-

tions, the prevention funds would need to

be distributed in a way that disseminates

benefits more broadly, even though this may

divert some funds to building infrastructure

and may produce a more diffuse (and less

measurable) impact. In the long-term, mak-

ing an investment to communities where

there is the greatest need but the weakest

infrastructure is likely to have a large impact

on the improvement of public health.

Using Investment in Prevention to

Address Health Disparities: The Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality has issued

reports for the past seven years that measure

and document the extent to which dispari-

ties exist in our health system. The reports

document the level of quality (e.g., safety,

timeliness) and access to care (e.g., barriers

to care) for various racial, ethnic, income

groups, as well as priority populations such

as children and older adults. This year’s report

found that significant disparities continue to

pervade our health care system.

71

The Affordable Care Act has several

provisions that address health disparities as

a priority in awarding various grants (e.g.,

community transformation grants) (Section

4201), developing research priorities (Sec-

tion 6301), gathering accurate data (Section

4302), and evaluating community preventive

services (Section 4003). In addition, the Pre-

vention Education Campaign must address

health disparities. The challenge of reaching

individuals and groups that have tradition-

ally been least well served by our health

care system is large, and it is important that

attention be paid during implementation

to developing effective strategies that reach

underserved populations with the informa-

tion they need.

Preventive Care Benefits: The require-

ment that private group and individual

health plans include preventive care ben-

efits (recommended by the U.S. Preventive

Services Task Force) without cost-sharing

could face some implementation challenges.

First, large employers that do not currently

cover preventive services (a small percent-

age of health plans)

72

could argue that the

requirement to cover preventive services will

increase premiums. Some might argue that

the requirements to cover preventive services

will increase total health care costs, notwith-

standing research that estimates an average

return of over $5 for each dollar invested in

The Council is well-positioned to build on the work of Healthy People 2010 and Healthy People 2020, and

has the authority to coordinate the work of various federal agencies in a way that is more transparent and

accountable to the public, the Administration and Congress.

17

prevention.

73

While premiums could increase

for the small percentage of plans that do not

already include preventive care benefits, the

increase in premium will offset out-of-pock-

et costs to cover such benefits, all of which

are to be covered because they are recom-

mended based on scientific evidence.

Another implementation issue concerning

the preventive benefits in private and public

health plans is the potential controversy that

could arise over certain recommendations

offered by the U.S. Preventive Services Task

Force and the Task Force on Community

Preventive Services. The controversy over

the recommendations on mammography

provided lessons about wording recommen-

dations carefully to reflect the nuances of the

evidence, and about the need for discussing

an individual’s personal circumstances with

health care providers.

74

A third implementation issue is timing:

When will health plans incorporate the new

preventive benefits? The grandfather provi-

sion (and Administration rule) affects the

timing. Grandfather status refers to the abil-

ity of a plan to continue to be offered “as is”

to current enrollees so that people can truly

“keep the plan” they are in.

75

In general, new

private policies issued after Sept. 23, 2010,

must include the new preventive benefits.

Employer Wellness Plans: Before the en-

actment of the health reform law, 58 percent

of companies that offered health benefits

covered at least one wellness program—such

as gym membership discounts, weight-loss

programs or nutrition classes—with larger

firms more likely than smaller firms to do so.

Few firms provided financial incentives for

employers to participate in these programs.

The most common forms of incentive, used

by 10 percent of firms, were gift cards, travel,

merchandise or cash. Only 1 percent of firms

offered a lower deductible for participating

in these programs, while 4 percent offered

a discount on the employer share of pre-

mium.

76

The Health Insurance Portability and Ac-

countability Act (HIPAA), enacted in 1996,

established requirements for employer well-

ness programs that guard against employer

health plans using minimum health standards

(e.g., blood pressure levels or tobacco ces-

sation) to discriminate against people who

have existing health conditions.

77

The provisions in the health reform law

that encourage and support employer well-

ness plans have the potential to raise con-

cerns that some employees may be penalized

because they do not meet certain health sta-

tus standards. The health reform law (section

4303) provides support to employers that of-

fer wellness programs. For example, technical

assistance will be provided to help employers

increase participation and evaluate the im-

pact. In addition, the law provides grants to

employers with fewer than 100 employees to

establish wellness programs.

78

While the law

prohibits the use of assessments to require

workplace wellness programs, some ques-

tions could arise when another provision is

implemented. Section 2705 of Title I, which

prohibits discrimination against individuals

based on health status (i.e., higher premiums

or denial of coverage), allows employers to

provide financial rewards to employees who

meet certain health standards. The financial

incentive can be as high as 30 percent of

the total employee premium initially, and

can increase to 50 percent eventually, if the

Secretary of the Department of Health and

T

he Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has issued reports

for the past seven years that measure and document the extent to

which disparities exist in our health system. The reports document

the level of quality (e.g., safety, timeliness) and access to care (e.g., barriers to

care) for various racial, ethnic, income groups, as well as priority populations

such as children and older adults.

18

Human Services allows this increase. Today

the potential reward for employees is limited

to 20 percent.

79

There are a number of re-

strictions that provide an opportunity for an

employee to improve his or her performance

on a health measure, but the bottom line is

that some employees might feel that they

are financially penalized for a poor blood

pressure or cholesterol test result which

they may consider to be more genetic than

controllable through good nutrition, exercise

and modified lifestyle habits.

The Affordable Care Act (Section 4303)

requires employers to build capacity to

evaluate the affect of these programs, and the

Director of the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention to assess, analyze and moni-

tor the impact of the programs, and report

findings and recommendations to Congress.

Earlier research about disease management

programs, which share many elements of

employer wellness programs, should provide

lessons for employers and the CDC to help

shape evaluation of these programs.

80

Healthcare and Public Health Workforce:

Millions of people will be newly covered

under health reform by expanded benefits

that include preventive care. This will place

increased demands on primary care provid-

ers who focus on prevention. Massachusetts

experienced shortages in primary care doc-

tors after implementation of its health re-

form law.

81

Title V of the Affordable Care Act

calls for a Healthcare Workforce Commis-

sion that will issue reports with recommen-

dations every year, beginning April 1, 2011.

Even before health reform was enacted, the

Association of American Medical Colleges

projected that there would be a shortage of

46,000 primary care doctors in 2025.

82

The workforce issues that must be ad-

dressed go beyond the pipeline issue of train-

ing more primary care providers. Expanding

access to high-quality, high-value care—and

matching that care to a workforce with the