Georgia State University Georgia State University

ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University

Counseling and Psychological Services

Dissertations

Department of Counseling and Psychological

Services

10-2-2009

Quantifying Social Justice Advocacy Competency: Development Quantifying Social Justice Advocacy Competency: Development

of the Social Justice Advocacy Scale of the Social Justice Advocacy Scale

Jennifer Kaye Dean

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cps_diss

Part of the Student Counseling and Personnel Services Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Dean, Jennifer Kaye, "Quantifying Social Justice Advocacy Competency: Development of the Social

Justice Advocacy Scale." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2009.

doi: https://doi.org/10.57709/1061384

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Counseling and Psychological

Services at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Counseling and

Psychological Services Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University.

For more information, please contact [email protected].

ACCEPTANCE

This dissertation, QUANTIFYING SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCACY COMPETENCY:

DEVELOPMENT OF THE SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCACY SCALE, by JENNIFER

KAYE DEAN, was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s Dissertation Advisory

Committee. It is accepted by the committee members in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Education, Georgia

State University.

The Dissertation Advisory Committee and the student’s Department Chair, as

representatives of the faculty, certify that this dissertation has met all standards of

excellence and scholarship as determined by the faculty. The Dean of the College of

Education concurs.

_________________________ _______________________

Greg Brack, Ph.D. Julie R. Ancis, Ph.D.

Committee Chair Committee Member

_________________________ _______________________

Catherine Y. Chang, Ph.D. Michele B. Hill, Ph.D.

Committee Member Committee Member

_________________________

Date

_________________________

JoAnna F. White, Ed.D.

Chair, Department of Counseling and Psychological Services

_________________________

R. W. Kamphaus, Ph.D.

Dean and Distinguished Research Professor

College of Education

AUTHOR’S STATEMENT

By presenting this dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

advanced degree from Georgia State University, I agree that the library of Georgia State

University shall make it available for inspection and circulation in accordance with its

regulations governing materials of this type. I agree that permission to quote, to copy

from, or to publish this dissertation may be granted by the professor under whose

direction it was written, by the College of Education’s director of graduate studies and

research, or by me. Such quoting, copying, or publishing must be solely for scholarly

purposes and will not involve potential financial gain. It is understood that any copying

from or publications of this dissertation which involves potential financial gain will not

be allowed without my written permission.

_______________________________

Jennifer K. Dean

NOTICE TO BORROWERS

All dissertations deposited in the Georgia State University library must be used in

accordance with the stipulations prescribed by the author in the preceding statement. The

author of this dissertation is:

Jennifer Kaye Dean

2558 Asbury Court

Decatur, GA 30033

The director of this dissertation is:

Dr. Greg Brack

Department of Counseling and Psychological Services

College of Education

Georgia State University

Atlanta, GA 30303-3083

VITA

Jennifer Kaye Dean

ADDRESS: 2558 Asbury Court

Decatur, Georgia 30033

EDUCATION:

Ph.D. 2008 Georgia State University

Counseling Psychology

M.S. 2001 Georgia State University

Professional Counseling

B.A. 1998 Georgia State University

Psychology

PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE:

2008- Present Adjunct Faculty

Argosy University, Atlanta, GA

2007- 2008 Pre-doctoral Psychology Intern

Texas Woman’s University, Denton, TX

2006- 2007 Psychometrist

Lifespan Psychological Services, College Park, GA

2005- 2007 Graduate Teaching Assistant

Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA

2001- 2005 Graduate Research Assistant

Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA

2001- 2002 Counselor

Odyssey Family Counseling Center, Hapeville, GA

SELECTED PRESENTATIONS AND PUBLICATIONS

Dean, J, K. (2001, October). A social constructivist approach to fostering cultural

sensitivity in white counselors. Southern Association for Counselor Education and

Supervision Conference, Athens, Georgia.

Dean, J. K., Chaney, M., Singh, A. A., Suprina, J., & Birckbichler, L. (2005, April).

Hidden resources, hidden rewards: Starting a departmental AGLBIC chapter and

bringing LGBTQI-client advocacy to life. American Counseling Association Annual

Conference Atlanta, Georgia.

Dean, J. K., Hays, D. G., & Chang, C. Y. (2003, August). Cultural identity, white

practitioners, and cross-cultural counseling practices. Poster session presented at the

American Psychological Association Annual Conference, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Dean, J. K., Singh, A. A., & Hays, D. G. (2003, September). Preparing counselors for

social advocacy. Southern Association for Counselor Education and Supervision

Conference Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Dean, J. K., Singh, A. A., & Lassiter, P. (2004, April). The role of advocacy in trauma

counseling: A narrative and feminist approach. American Counseling Association

Annual Conference Kansas City, Missouri.

Hays, D. G., Chang, C. Y., & Dean, J. K. (2004). White counselors’ conceptualizations of

privilege and oppression: Implications for counselor training. Counselor Education and

Supervision, 43, 242- 257.

Hays, D. G., Dean, J. K., & Chang, C. Y. (2003, March). Addressing white privilege,

oppression, and racism: Challenges and rewards. American Counseling Association

Annual Conference. Anaheim, California.

Hays, D. G., Dean, J. K., & Chang, C. Y. (2007). Addressing privilege and oppression in

counselor training and practice: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Counseling and

Development, 85, 317-324.

Singh, A., Chung, Y. B., & Dean, J.K. (2006). Ethnic and sexual identity attitudes of

Asian American lesbian and bisexual women: An exploratory analysis. Journal of GLBT

Issues in Counseling, 1, (2).

ABSTRACT

QUANTIFYING SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCACY

COMPETENCY: DEVELOPMENT OF THE SOCIAL

JUSTICE ADVOCACY SCALE

by

Jennifer K. Dean

Social justice advocacy has been a force throughout the history of Counseling

Psychology and has been described as more critical to the field than any other time in its

long history (Toporek & McNally, 2006). Accordingly, in 2002, the American

Counseling Association endorsed the Advocacy Competencies in an effort to advance the

status of social advocacy by defining competency for counselors engaged in social

advocacy (Lewis, Arnold, House, & Toporek, 2002). However, at the writing of this

article, these competencies had not yet been operationalized. Therefore, a comprehensive

review of the multidisciplinary literature was conducted and seventy- three skills

consistent with these competencies were identified and used to further describe what it

means to be a competent social justice advocate. These skills were then used to create a

measure of social justice advocacy. Content validity of the items was addressed through

the use of expert ratings. One hundred participants were recruited to take this measure.

Exploratory factor analysis yielded a four-factor model of social justice advocacy skills:

Collaborative Action, Social/Political Advocacy, Client Empowerment, and

Client/Community Advocacy. Evidence for construct validity was found in the expected

positive correlations between the social advocacy survey and the Multicultural

Knowledge and Awareness Scale (Ponterotto et al., 2002) and the Miville-Guzman

Universal-Diverse Orientation Scale- Short Form (Fuertes et al., 2000). The resulting 43-

item survey serves as a starting point for operationalizing and assessing counselors’

competence in social justice advocacy.

QUANTIFYING SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCACY

COMPETENCY: DEVELOPMENT OF THE SOCIAL

JUSTICE ADVOCACY SCALE

by

Jennifer K. Dean

A Dissertation

Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the

Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

in

Counseling Psychology

in

the Department of Counseling and Psychological Services

in

the College of Education

Georgia State University

Atlanta, GA

2008

Copyright by

Jennifer K. Dean

2008

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am eternally grateful for the support and challenge from my teachers and

mentors. My advisor, Dr. Greg Brack, and my committee members, Drs. Julie Ancis,

Catharina Chang, and Michele Hill, are my models for academic excellence, integrity,

living a balanced life, and social justice advocacy. I am grateful for the expertise and

assistance provided by Drs. Barbara Gormley, Michele Hill, Will Liu, Karia Kelch-

Oliver, Jonathan Orr, Damafing Thomas, and Rebecca Toporek. The thoughtful

comments and questions raised by Drs. Jeff Ashby and Roger Weed and my fellow

Prospectus students were instrumental. I also want to thank my mentors, Drs. Denise

Lucero- Miller, Carmen Cruz, and the rest of the women at the Texas Woman’s

University Counseling Center who taught me first-hand the meaning of empowerment.

As for Dr. Shane Blasko, Dr. Brigitt Lamothe- Francois, Dr. Riddhi Sandil and the

Dissertation Support Group led by Dr. Barbara Gormley, you made this a relational

process for me and, therefore, helped me to maintain my sanity.

I thank my family, Linda, John, Teresa, and Andrea for always being there for me

and for teaching me the meaning of compassion and fairness. I thank David, my husband,

partner, and friend, for lovingly and patiently listening to me, helping me to put things in

perspective, and making so many sacrifices. Lastly, I thank you, Isabel. You make

everything, especially this, more meaningful.

ii

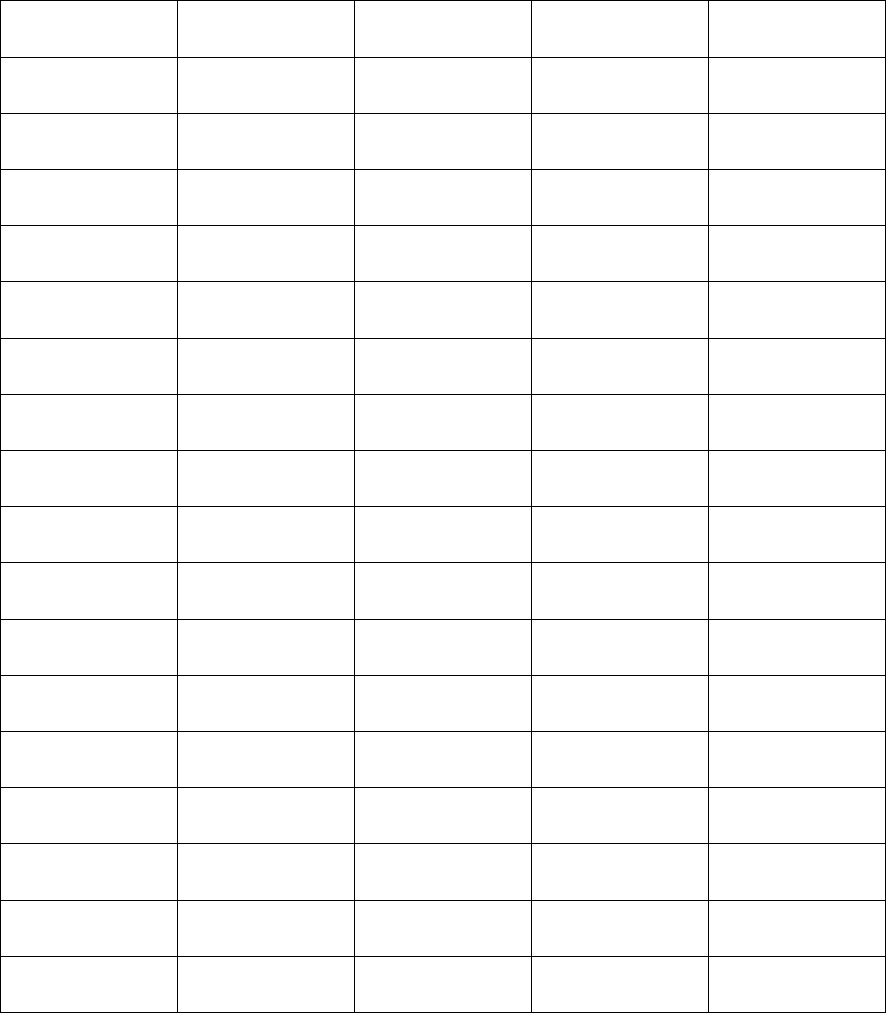

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

List of Tables ..…………………………………………………………………… iv

Abbreviations .……………………………………………………………………. v

Chapter

1 SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCACY: COUNSELING

PSYCHOLOGY’S TOOLS FOR SOCIAL CHANGE…………...

1

Introduction……………………………………………………….. 2

Conceptualizing Social Justice Advocacy………………………... 4

Advocacy Skills…………………………………………………... 5

Conclusions……………………………………………………….. 27

References………………………………………………………… 30

2 DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE SOCIAL

JUSTICE ADVOCACY SKILLS SURVEY……………………... 41

Advocacy Skills…………………………………………………... 45

Related Constructs………………………………………………... 46

Methodology……………………………………………………… 51

Results…………………………………………………………….. 60

Discussion………………………………………………………… 72

References………………………………………………………… 83

Appendixes …………………………………………………………………….. 94

iii

LIST OF TABLES

Table Page

1 Corrected Item- Total Correlations.………………………………………. 61

2 Factor Structure, Eigenvalues, and Total Variance Explained…………… 68

3 Pattern Matrix…………………………………………………………….. 69

4 Factor Correlations……………………………………………………….. 71

5 Construct Validity Correlations…………………………………………... 72

iv

ABBREVIATIONS

ACA American Counseling Association

APA American Psychological Association

EFA Exploratory Factor Analysis

GLBT Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender

MCKAS Multicultural Counseling Knowledge and Awareness Scale

MC Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale

MGUDS-S Miville-Guzman Universal-Diverse Orientation Scale- Short Form

NCHEC National Commission for Health Education Credentialing

PBJW Personal Belief in a Just World Questionnaire

SPA Scientist-Practitioner-Advocate

WHO World Health Organization

v

CHAPTER 1

SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCACY:

COUNSELING PSYCHOLOGY’S TOOLS FOR SOCIAL CHANGE

1

2

SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCACY:

COUNSELING PSYCHOLOGY’S TOOLS FOR SOCIAL CHANGE

Social justice advocacy has been described as being more critical to counseling

psychologists at this time than at any other point in its history (Fouad, Gerstein, &

Toporek, 2006; Hage, 2003; Hartung & Blustein, 2002; Ivey & Collins, 2003; Kiselica &

Robinson, 2001; Toporek & McNally, 2006). This is evidenced by several major steps

taken to institute social justice advocacy as a central professional activity, including

several recent professional publications on the topic, the endorsement of the Advocacy

Competencies by the American Counseling Association (ACA), the development of new

professional organizations (e.g., Counselors for Social Justice, Psychologists for Social

Responsibility), and a professional journal, Journal for Social Action in Counseling and

Psychology, devoted to social justice and advocacy (Foaud et al., 2006). As traditional

and individualized models of helping have been criticized for their failure to take into

account the influence of oppression on human problems (Albee, 2000; Prilleltensky,

1997), a return to counseling psychology’s social justice foundation has been called for

by a several authors (Fouad et al., 2004; Fouad et al., 2006). A social justice advocacy

approach involves working to end the effects of oppression on clients’ lives rather than

solely addressing its psychological consequences (Benjamin & Baker, 2004; Speight &

Vera, 2004). As such, it has been described as more efficient and as more relevant to a

multicultural society (Helms, 2003). Some counseling psychologists have projected that

the future of assessing counseling students’ competence will extend beyond knowledge

3

of human diversity to skills for advocacy (Fassinger & Gallor, 2006). Similarly, some

scholars are calling for social justice, which is the goal of social advocacy, to become

operationalized as a researchable construct (Crethar, 2004; Hutchins, 2006; Rivera,

2006).

In 2002, the American Counseling Association published a set of competencies

for advocacy (Lewis, Arnold, House, & Toporek, 2002). Defining competence is needed

to ensure ethical advocacy practice (Toporek, 2006). Although this is a crucial step for

ensuring competency in advocacy interventions, there is a need to operationalize these

competencies. To that end, this paper will present a review of the multidisciplinary

literature and describe the advocacy skills and behaviors that fall within the advocacy

competencies.

Working Definitions

Advocacy has been defined as “action a mental health professional, counselor, or

psychologist takes in assisting clients and client groups to achieve therapy goals through

participating in clients’ environments. Advocacy may be seen as an array of roles that

counseling professionals adopt in the interest of clients, including empowerment,

advocacy, and social action” (Toporek & Liu, 2001, p.387). Social justice advocacy

includes action aimed at the realization of a just society, which respects and is protective

of human rights, is inclusive of a plurality of interests, and is responsive to the most

marginalized members of a society (Cohen, 2001). A distinction must be made between

professional advocacy and social advocacy, whereby professional advocacy efforts refer

4

to those aimed at greater influence of the Counseling Psychology profession and social

advocacy is directed toward the achievement of social justice (McCrea, Bromley,

McNally, O’Byrne, & Wade, 2004; Toporek & Liu). Consistent with Toporek and Liu,

the term “advocacy” will refer to the roles and behaviors aimed at client empowerment,

social advocacy, and social change. The purpose of delineating these skills is to help

further the integration of advocacy training into counseling and counseling psychology’s

curriculum and practical training by describing the specific behaviors to be included in

training.

Conceptualizing Social Justice Advocacy

Advocacy Competencies

Lewis and her colleagues (2002) have articulated forty-three competencies needed

for counselors with an advocacy-orientation. The advocacy competencies are classified

along three levels: the client or student level, the organizational/school or community

level, and the sociopolitical level (see Appendix A). Along these three levels, the

competencies are split into empowerment and advocacy domains, whereby empowerment

refers specifically to acting with the client and advocacy refers to acting on behalf of a

client or client group. The competencies are divided into empowerment and advocacy

activities across these three levels. This results in six separate domains with the three

levels split into empowerment and advocacy skills, which are (1) client/student

empowerment, (2) client/student advocacy, (3) community collaboration, (4) systems

advocacy, (5) public information, and (6) social/political. In order to operationalize these

5

competencies, the literature was reviewed for advocacy behaviors, which expand on these

competencies and, thus, can guide counselors in implementing competency advocacy

practice.

Advocacy Skills

Becoming an advocate often involves the process of being personally impacted by

social injustice and becoming empowered to work toward social change targeted at this

specific issue or population (Gerstein & Kilpatrick, 2006; McWhirter & McWhirter,

2006). These can range from local grass-roots efforts to larger scale organized endeavors

conducted with professional associations such as the American Counseling Association

and the American Psychological Association. The first step in describing the skills

needed for advocacy is to examine the multidisciplinary literature for thematic content in

the types of competencies and skills needed for advocacy. A review of the

multidisciplinary literature yielded 74 specific behaviors that were organized into the

domains and competencies specified by the Advocacy Competencies (Appendix B).

Client/Student Empowerment

McWhirter (1994) defined empowerment as the following:

Empowerment is the process by which people, organizations, or groups who are

powerless or marginalized (a) become aware of the power dynamics at work in

their life context, (b) develop the skills and capacity for gaining some reasonable

control over their lives, (c) which they exercise, (d) without infringing on the

6

rights of others, and (e) which coincides with actively supporting the

empowerment of others in their community. (p. 12).

Empowerment within a social advocacy context has a specific reference to the

client’s socioeconomic, sociocultural, and sociopolitical context, rather than simply

referring to increasing clients’ self-efficacy in a more general sense (Toporek & Liu,

2001). This is similar to the distinction between personal and social empowerment made

by Cowger (1994), where personal empowerment refers to self-determination and social

empowerment refers to the possession of resources and opportunity to place a significant

role in one’s environment and in shaping that environment. Sixteen counselor behaviors

consistent with this definition of empowerment were identified in the literature. This

occurred as a result of conducting a thorough literature review of “empowerment” and

“social advocacy”, using PsychInfo, and identifying specific counselor behaviors, which

were described and were consistent with McWhirter’s (1994) definition (see Appendix

B).

Lewis and colleagues (2002) have included the ability to identify the strengths

and resources of clients as an important skill for client empowerment. Consistent with

this competency, interventions that identify and utilize client resources, such as

spirituality, religious affiliation, and kinship networks have been recommended (Vera &

Shin, 2006). Empowerment research focused upon women consumers of social services

agencies suggests that recognizing the ways in which clients already exert power within

their environments is a necessary skill for client empowerment (Trethewey, 1997).

7

Empowerment counseling has also been applied to other marginalized groups, such as the

gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT) community (Norsworthy & Gerstein,

2003).

The identification of social, political, and cultural factors affecting the client is

another competency included under client empowerment (Lewis et al., 2001). Toporek

and Liu (2001) urged counselors to recognize the intersection of multiple oppressions and

their effects on clients. Related to this competency, Kiselica and Robinson (2001) have

asserted the need for the basic skills of listening, understanding, and responding

empathically to clients impacted by social problems. These skills direct the counselor to

listen carefully for the presence of these issues in clients’ narratives and to respond to

these experiences in a therapeutic manner. Additionally, research has highlighted the

need for clinicians to examine the power relationships between clients and the institutions

with which they interact (Trethewey, 1997). Cowger (1994) also urged clinicians

explicitly to include the role of social structures when assessing clients.

Similarly, recognizing the effects of systemic or internalized oppression on a

client is also a competency for social empowerment (Lewis et al., 2002). Several

researchers have more specifically urged practitioners to assess for and attend to the

predictable psychological effects of racism on persons of color (Bryant-Davis & Ocampo,

2005; Vera & Shin, 2006; Wyatt, 1990). Therefore, counselors would need to be attuned

to symptoms which are correlated with internalized racism such as: cardiovascular and

psychological reactivity, psychological distress, depressive symptoms, increased alcohol

8

consumption, low self-esteem, a lack of socioemotional development in children, and

chronic health problems (Bryant-Davis & Ocampo). The ability to identify these effects

would entail the ability to use critical thinking to understand how multiple sources of

oppression are interlocking and how they impact clients (Aspy & Sandhu, 1999; Chen-

Hayes, 2001; Rudolf, 2003; Toporek & Liu, 2001).

Assisting clients in identifying the external barriers to their development is

another competency within the category of client empowerment (Lewis et al., 2002).

Furthermore, Cowger (1994) asserts that client problems rarely result from a single cause,

but rather from a myriad of events, therefore, clinicians need to be skilled in viewing

problems from this perspective. A related skill in this domain is the ability to assist

clients in giving meaning to the social contextual factors that impact their situations

(Cowger).

Training clients to become their own advocates is an additional competency

within the empowerment domain (Lewis et al., 2002) and some preliminary empirical

data exists to support the therapeutic effectiveness of these skills (Epstein, West, &

Riegel, 2000; Stringfellow & Muscari, 2003). Stringfellow and Muscari used formal self-

advocacy training for clients and families of those with psychiatric disabilities to serve as

their own organized advocates and noted positive psychological benefits. Although these

formal advocacy training programs were quite specific to the groups and contexts with

which these clinicians dealt, common themes, such as assisting clients in developing

communication skills needed for advocacy have been recommended (Trethewey, 1997).

9

Furthermore, connecting clients with organizations that advocate for the issues affecting

them can also aid them in accessing more formal training as an advocate.

To facilitate client empowerment, assisting clients in developing self-advocacy

plans has been recommended (Lewis et al., 2002). Developing such plans might involve

assessing clients’ understanding of laws and policies that apply to them (Toporek & Liu,

2001). This would also involve collaborating with clients in deciding upon appropriate

actions needed for environmental changes in a client’s life (Toporek & Liu).

A final competency for client empowerment is to assist clients in carrying out

their self-advocacy plans (Lewis et al., 2001). Although this is dependent upon the plan

that is created collaboratively between the client and counselor, this could involve such

actions as assisting clients in calling state and federal agents and in navigating other

bureaucracies (Toporek & Liu, 2001).

Client/Student Advocacy

Client advocacy encompasses the use of a counselor’s power to act on behalf of a

client (Lewis, Arnold, House, & Toporek, 2005). Although this differs from client

empowerment, which entails using one’s power to act with a client or group, counselors

are cautioned to balance advocacy actions with empowerment activities to decrease

dependency on the counselor when possible and, thus, prevent unintended oppression

(Lewis et al., 2005). Intervening at this level is recommended when counselors are aware

of external factors that act as barriers to development (Lewis et al., 2002). Although

client empowerment is a generally preferred mode of intervention, client-level advocacy

10

is critical when clients are “overwhelmed by a multitude of problems or so

disenfranchised or lacking in information or skills” to advocate for themselves in the

present (Kiselica, 2004, p. 848).

According to the Advocacy Competencies, the client-level advocate is able to

negotiate for relevant services and education systems on clients’ behalf (Lewis et al.,

2002). Communicating with local, state, and federal representatives on behalf of clients’

needs is one way in which counselors can serve as advocates (Toporek & Liu, 2001).

This involves the ability to communicate effectively with those in positions of power who

can improve clients’ situations (Kiselica, 1995; Kiselica & Pfaller, 1993). More

specifically, knowing one’s audience and understanding how to own one’s power in these

situations, such as identifying oneself as a constituent, voter and member of local mental

health advocacy groups when communicating with local legislators have been suggested

(Hoefer, 2006). In some situations, the counselor is urged to serve as a mediator between

clients and institutions (Dinsmore, Chapman, & McCollum, 2000).

Assisting clients in accessing needed resources is an additional competency for

client advocacy (Lewis et al., 2002). This involves forming collaborations with

professionals to meet client needs (Brabeck, Walsh, Kenny, & Comilang, 1997; Toporek

& Liu, 2001). This can also include communicating with local, state, and federal

representatives on behalf of clients’ needs to assist them in accessing needed resources

(Toporek & Liu, 2001). As a professional, one is sometimes afforded more social power

11

and other resources, such as relationships with other professionals, when interacting with

other professionals and or legislators, which can be used to benefit those with less power.

Identifying barriers to the wellbeing of individuals and groups is a competency for

the client-level advocate (Lewis et al., 2002). Being a client advocate involves evaluating

client complaints of prejudice within a counselor’s organizational context (Toporek &

Liu, 2001). A counselor must have the ability to think critically and to understand the

interlocking and multiple sources of oppression (Chen- Hayes, 2001). Lee (1998) has

also described a systemic level of awareness, which allows counselors to assess

environmental barriers on development and to become skilled in challenging these

barriers. The cognitive ability to accurately assess multiple environmental influences and

forces has been found elsewhere in the literature (Aspy & Sandhu, 1999; Rudolf, 2003).

The ability to develop initial plans of action to confront client barriers is another

indication of a competent social justice advocate (Lewis et al., 2002). Although the

literature is largely absent in regards to how to go about developing a client advocacy

action plan, collaborating with clients in deciding what environmental changes are

necessary, as one would do with a client self-advocacy plan, would also apply (Toporek

& Liu, 2001). Thus, although the literature lacks specifics with regard to developing

action plans to confront client barriers, the guidelines of collaborating with the client in

identifying barriers and strategically working to remove or work around those barriers

can help the counselor to create such plans.

12

In regard to carrying out those plans of action (Lewis et al., 2002), several

specific actions are present in the literature. The ability to effectively persuade targets of

advocacy to act on behalf of client or issue is a potential skill needed for such action

(Hoefer, 2006). The ability to speak out against inequities, such as discriminatory

processes that affect clients is also necessary (Toporek & Liu, 2001). Kiselica (2004, p.

851) has offered direction for doing so by pointing out that effectively challenging

inequities involves skilled “empathic-confrontation” in an effort to minimize

defensiveness or withdrawal and instead to engage the person being challenged.

According to Kiselica, counselors should develop empathy for the person being

challenged by understanding the systemic-contextual influences on prejudice while

sharing one’s own struggles with overcoming biases and modeling continued efforts to

behave in a more just manner. Further, the continuous assessment of the progress of one’s

advocacy interventions within the context of the client’s environment is necessary to

understand the impact of the counselor’s actions (Vacc, 1998).

The identification of potential allies for confronting these barriers is critical for

achieving social justice advocacy for an individual client and is necessary for setting the

stage for community-level advocacy (Lewis et al., 2002). Serving as a visible ally for

issues that affect clients is another way in which power as a counselor can be used to

advocate for social justice (Toporek & Liu, 2001).

13

Community Collaboration

Although communities are not traditional targets of counseling and psychological

interventions, an exclusive focus on the individual without attention to the community or

social/political group to which the client belongs and may inadvertently lead to blaming

the individual for problems. Because of this potential for blame, failure to take into

account the community context of a client has been described as an oppressive process

(Fraser, 1987). Within this vein, Vera and Shin (2006) have pressed for the need to

intervene directly in environments that place children at risk for future psychological

problems based on socially toxic environments. These actions include helping

community parents organize themselves and participate in public hearings and, when

working within the school system, organizing meetings in which parents can speak to

school administrators. Further, a collaborative approach to advocacy is necessary in

order to develop and implement community interventions with cultural awareness and

knowledge that is provided by the community group to prevent disempowerment and

failure (Goodkind, 2005).

Lewis and colleagues (2002) recognize the ability to identify environmental

factors that impinge upon students’ and clients’ development as a competency for

community collaboration. This includes obtaining information regarding the

sociohistorical context of the problems from the community (Toporek, Gerstein, Fouad,

Roysircar, & Israel, 2006).

14

Alerting community groups with common concerns to the issue for which one is

advocating is another indicator of competent empowerment work with a community

(Lewis et al., 2002). Similarly, Rudolf (2003) has recommended that the advocate

identify key stakeholders in the problem to accomplish this task. Identifying key

stakeholders urges the counselor to look beyond the client or community group and to

understand the systemic nature of problems and to work at building relationships among

the groups who are impacted by a given policy or practice.

Similarly, developing alliances with other groups working for change has been

recommended (Lewis et al., 2002). Relationship- building has been described as a vital

component to community collaboration (Thompson, Alfred, Edwards, & Garcia, 2006;

Vera, Daly, Gonzales, Morgan, & Thakral, 2006). More specifically, these authors have

stressed the importance of building an affiliation with a trusted community member or

establishment within the community one plans to work, as well as honoring that trust by

ensuring that the community work is designed to meet the needs of the community group

rather than the sole needs of the counselor or researcher. Community collaboration also

involves establishing relationships with civic organizations and businesses within the

community. Successful collaborations, such as the Heritage Project in Bloomington,

Indiana depend upon the financial support of community organizations (Thompson et al.,

2006). This project initiated by the Black residents of this community was successful in

improving the quality of their children’s educational and socialization experiences. Their

activities have resulted in increased racial consciousness and the building of a community

15

of Black activists and allies across social classes. In this example, counselors’ skills in

community collaboration mobilized a community to make major systemic changes to

promote the healthy development of its children.

Effective listening skills to gain an understanding of the groups’ goals have been

highlighted as necessary for competency as a counselor working within a community

(Lewis et al., 2002). This entails the ability to conduct formal and informal needs

assessments that are inclusive of community members’ perspectives (Vera et al., 2006).

Such accurate understanding is necessary to ensure a collaborative working relationship

with the community and to establish one’s credibility.

The competency of identifying the strengths and resources of a community also

attends to the importance of relationship building (Lewis et al., 2002). More specifically,

other authors, (i.e., Toporek & Liu, 2002), have pointed out that the counselor needs to

assess and point out strengths and resources that community members bring to the change

process. To facilitate relationship- building with community members, counselors are

urged to identify the strengths and resources of communities that its members bring to the

process of systemic change (Toporek & Liu). For example, Goodkind (2005) has

emphasized the need for mutual learning in her advocacy work with Hmong refugees.

This is accomplished through the use of Learning Circles, in which they discuss social

justice issues, share ideas and resources with one another, and plan for addressing unfair

institutional or systems collectively.

16

Once these skills are identified, the counselor needs to effectively communicate

recognition and respect for the strengths and resources of a community’s members

(Lewis et al., 2002). Other advocates have stressed the need to engage the community

and to recognize them as experts on their situations by engaging them in providing a

history of previous problem-solving attempts (Toporek, Gerstein, Foaud, Roysircar, &

Israel, 2006). Furthermore, respect can be communicated by participation in community

functions of the client populations served (Toporek & Liu, 2002).

The competent social advocate also needs to identify and offer the skills that he or

she can bring to the collaboration (Lewis et al., 2002). This can involve publishing

qualitative studies focused on giving voice to silenced communities (Goodman et al,

2004; Morrow, 2007), as well as working with community members to disseminate their

ideas to the media (Goodman et al.).

Lastly, it is important to assess the effects of the counselor’s interaction with the

community (Lewis et al., 2002). This is an area that lacks attention in the counseling

literature; therefore, no specific skills were identified for this competency.

Systems Advocacy

Acting on behalf of clients within the organizational or systems domain entails the

ability to identify environmental factors that thwart clients’ development (Lewis et al.,

2002). Toward this end, Hoefer (2006) has highlighted the need to determine who is

positively and who is negatively affected by any given organizational policy or decision

(Hoefer). If it is determined that a policy or decision is unjust or biased, the systems

17

advocate must teach his or her colleagues to recognize this (Hendricks, 1994; Williams &

Kirkland, 2001). The Advocacy Competencies also include the ability to develop a vision

to guide change in collaboration with other stakeholders (Lewis et al.). More specifically,

this can include the ability to negotiate with employers for changes in institutional policy

that are conducive to positive growth and development of clients (Brown, 1988).

The ability to analyze the sources of political power and social influence within

systems is a requirement for acting as an effective social advocate (Lewis et al., 2002).

Toporek (2001) has proposed that multicultural competence involves understanding one’s

relationship to power, not only within personal and professional contexts, but also in

institutional contexts. According to Toporek, the institutional context has often been

omitted from counselor training, so that counselors who take on roles of institutional

power are left without guidance in examining and challenging organizational policies that

adversely affect clients or students of color. Therefore, an understanding of institutional

power and one’s professional power is essential to acting as an agent of change within

systems or organizational contexts. Of importance to the study of systems advocacy in

the field of counseling is that organizations focused on human services are severely

understudied in the literature (Trethewey, 1997). Those that have been particularly

ignored and underfunded are those agencies that serve poor women (Hasenfeld, 1992).

Trethewey has examined the ways in which poor women exercise their power and effect

change within human services organization and has recommended that this be

acknowledged in any analysis of power within systems.

18

The development of a step-by-step plan for implementing the change process is

critical to ensuring that the advocacy is carried out as agreed upon by collaborators

(Lewis et al., 2002). In carrying out plans to rectify an injustice, the ability to

communicate the environmental changes needed for just treatment of clients to agencies

has been recommended (D’Andrea & Daniels, 1999; Hendricks, 1994; Williams &

Kirkland, 1971).

The ability to develop a plan for dealing with probable responses to change is also

specified as a necessary competency for social justice advocacy (Lewis et al., 2002);

however, no skills for doing so were identified in the literature. Thus, this is an area in

need of dialogue in regards to how organizations typically react to change and how an

advocate can fruitfully address those reactions.

Lewis and her colleagues have also included the need to recognize and deal with

resistance to change as a guideline for competent advocacy (Lewis et al., 2002). This may

involve contacting funding agencies when oppressive practices or inadequate services are

observed (Dinsmore et al., 2000). Further, the National Board of Certified Counselors’

(2008) code of ethics has provided guidelines regarding the termination of one’s

professional affiliations when injustice continues and when options for organizational

change have failed.

As with other levels of advocacy, an essential competency is the ability to assess

the effects of one’s advocacy efforts on the targeted system and those it serves (Lewis et

al., 2002). Likewise, Toporek and Williams (2006) have highlighted the need to examine

19

the effects of interventions, such as projects designed to reduce depression, anxiety, and

impulsive behavior in a community. They suggest the possibility that these efforts could

inhibit social justice, as these efforts may unintentionally serve as social control by

helping persons to adapt to unfair life circumstances, which they might otherwise

challenge. For example, designing programs to assist individuals in managing anger

associated with oppressive environments without addressing the environment can

actually help to maintain that oppressive system by relieving individual’s pain that may

prompt social action. Methods of critically evaluating the effects of such interventions are

clearly needed to ensure that such interventions are aimed at empowering community

members to engage in social change rather than thwarting social justice efforts.

Additionally, the ability to provide and interpret data to show the urgency for change is a

professional competency (Lewis et al.). This competency has also not yet been described

adequately in the professional literature; therefore, strategies for researching advocacy

represent an area in need of attention.

Public Information

A critical component of advocacy practice is the ability to bring attention to the

issue or concern for which one is advocating. Some psychologists have even attributed

most of the practice advances within the field to intensive efforts to educate

administrators and policymakers about the benefits of psychology (Faltz, 2001). In order

to achieve this, counselors’ recognition of the impact of oppression and other barriers to

healthy development is primary (Lewis et al., 2001). Keeping abreast of the literature

20

regarding the effects of oppression on human development is, therefore, essential (Vera

& Shin, 2006).

Furthermore, in an effort to understand which policies for which to advocate, the

identification of environmental factors that are protective of healthy development is

another competency (Lewis et al., 2002). This necessitates being familiar with the

research that not only documents the effects of oppression, but also articulates protective

factors (see Vera & Shin, 2006).

Once these factors are identified, the effective preparation of written and multi-

media materials providing clear explanations of the role of these specific environmental

factors in healthy development is needed (Lewis et al., 2002). These include the ability to

prepare press releases, to write effective letters to the editor, and to write newspaper

articles (Brawley, 1997; Rudolf, 2003). Mental health advocacy is an example of one

type of advocacy that relies on public information efforts to combat the stigma and

prejudice toward persons with mental disorders (Funk, Minoletti, Drew, Taylor, &

Saraceno, 2005). The World Health Organization (WHO; 2005) has taken the position

that ignorance about mental disorders contributes to a perspective that the government’s

primary responsibility is to protect the public from persons with mental disorders rather

than promoting access to quality treatment and protecting their human rights. In the case

of mental health advocacy, persons with mental illness and their families have undertaken

efforts at educating the public and influencing the government, which has had the added

21

mental health benefits of increased empowerment and self-esteem (Goering et al., 1998;

Wahl, 1999).

Within the public information domain, a competent advocate can communicate

information in ways that are ethical and appropriate for the target population (Lewis et

al., 2002). Health educators have long recognized this need and explain that advocates

providing public information need to be able to demonstrate proficiency and accuracy in

oral and written presentations (National Commission for Health Education Credentialing

[NCHEC], 1999). They also include the use of culturally sensitive communication

methods and techniques as a competency within this domain (NCHEC).

Competent advocates are also able to disseminate information through a variety of

media (Lewis et al., 2002). The effective use of the media has been cited several times as

a skill for social justice advocacy (Brawley, 1995, 1997; Duncan, Rivlan & Williams,

1990; Dworak-Peck & Battle, 1988). Borshuk and Cherry (2004) have recommended

using creative means to bring attention to client issues and perceived injustices. Further,

the ability to write public service announcements and to capture the attention of the

broadcast media for issues related to social justice and their impact on mental health and

human development are skills that can influence the development of social policies and

services (Brawley, 1997; Rudolf, 2003).

The ability to identify and collaborate with other professionals who are involved

in disseminating public information is also essential (Lewis et al., 2001). Effective

advocates, such as those holding leadership positions in professional organizations, have

22

articulated the need to bring about awareness of a problem or issue to other professionals

(Ritvo et al, 1999). These groups rely on accessing newsletters, professional journals,

websites, and professional meetings to educate their colleagues about the issue at hand.

Finally, the ability to assess the influence of public information efforts undertaken

is necessary to ensure the efficacy of public information (Lewis et al., 2001). Although

no specific skills for public information assessment were found in the literature,

counselors are well prepared to apply their knowledge of research methods to outcome

assessment of their efforts. Furthermore, there is a wealth of public information outcome

research instruments in use by those working in public health promotion fields designed

for both well-resourced and less resourced countries and communities (Saxena, et al.,

2007). These could be adapted to assess the efficacy of public information efforts

designed to publicize the mental health effects of oppression and the environmental

factors that are protective of healthy psychological development.

Social/Political Advocacy

An initial competency for engaging in action at this level is to first have the

ability to distinguish problems that can best be resolved through social/political advocacy

(Lewis et al., 2002). Rudolf (2003) includes training in determining the level in which

advocacy efforts would be best directed in advocacy training curriculum for pediatricians.

More specifically, she trains pediatricians in the United Kingdom to examine whether

patient barriers exists on an individual level, a public health level within community, a

public health level within city, or a public health level nationally. These levels parallel

23

the three levels of advocacy and empowerment that are described by the Advocacy

Competencies, whereby the individual level corresponds to the client level of advocacy,

the community level corresponds to the systems level, and the city and national levels

correspond to the social/political levels. To further aid in one’s ability to accurately

assess the level on which advocacy efforts are needed, it has been recommended that

counselors have an understanding of state laws and relevant policies pertaining to the

populations they are likely to see (Toporek & Liu, 2001). This knowledge is necessary in

order to understand the larger social political context in which clients’ function and can

aid the counselor in more readily identifying the macrolevel influences on client

concerns. Furthermore, staying abreast of proposed legislations and examining them for

fairness to underrepresented groups is essential to acting as a social justice advocate

(Shullman et al., 2006).

George Mason University has also instituted collaborative efforts through

partnership building at local, state, national, and international levels (Talleyrand et al.,

2006). Furthermore, professional advocacy groups have recognized the importance of

building collaborations between professional groups and funding agencies in an effort to

gain funding for training and research of psychotherapy services for clients, in addition to

advocating for reimbursement for clinicians who offer these services (Ritvo et al., 1999).

From an ecological systems theory perspective, social/political advocacy occurs at

the macrolevel and includes social policies and the larger culture in which the individual

exists (Bronfenbrenner, 1989). It has been noted that the majority of interventions take

24

place within client or organizational levels rather than within the larger social political

arena (Lewis et al., 2001; Rudolf, 2003). However, psychologists’ social justice advocacy

efforts at this broader level have resulted in major cultural shifts toward social justice. A

primary example is Mamie Clark and colleagues’ research, which documented the effects

of segregation on the self-esteem of African American children and had a strong

influence on the outcome of the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education decision (Pickren,

2004). Furthermore, the impact of psychological research regarding the detrimental

effects of conversion therapy on GLBT persons and the impact of sexual harassment in

the workplace have helped to shape laws and social policies regarding these practices

(Shullman, Celeste, & Strickland, 2006).

Once it has been determined whether a problem can best be resolved through

macrolevel advocacy, the competency to identify the appropriate mechanism for

addressing it is considered necessary (Lewis et al., 2002). This is facilitated by

understanding the political framework and processes to effect change (Rudolf, 2003). The

American Psychological Association has published documents for aiding psychologists in

understanding how to participate in the federal advocacy process and recommends that

advocates know the roles of their legislators (APA, 2006). Further, an understanding of

how to target one’s actions has been considered an additional element of this competency

in advocacy training (Rudolf, 2003).

In conducting social/political advocacy, the authors of the Competencies

underscore the importance of acting with allies (Lewis et al., 2002). They include seeking

25

out and joining with potential allies as a competency. Other advocates have urged

counselors to persuade other colleagues to become involved in social justice advocacy

and to train others in social/political advocacy (Shullman et al., 2006). In addition, they

have written about sending out electronic action alerts to colleagues regarding social

justice issues as a way of collaborating with potential allies (Shullman et al.).

Similarly, it is recommended that counselors support existing alliances for change

(Lewis et al., 2002). Forms of support can include making and/or soliciting financial

contributions to social justice groups that influence public policy (Shullman et al., 2006).

Additionally, the literature has pointed out that support for national, state, territorial, and

provincial professional organizations in their public policy serves a social advocacy in

this capacity (Shullman et al.)

A competent social justice advocate- counselor should also be trained to prepare

convincing data and rationales for change with allies (Lewis et al., 2002). From the

earliest stages, this includes orienting one’s research toward influencing public policy

toward social justice (Bingham, 2003; Enns, 1993). Also, using research data to influence

public policy has been described elsewhere as a skill (Toporek & Liu, 2001). One

specific way in which this is accomplished is through the development of research

summaries for policy makers (Shullman et al., 2006).

Competent advocate-counselors acting at the social/political level have the ability

to lobby legislators and other policy makers with allies (Lewis et al., 2002). This has been

described as working to change existing laws and regulations that negatively affect

26

clients (Toporek & Liu, 2001). On a more proactive level, social advocates work with

others to develop policy initiatives (Shullman et al., 2006). Social advocate-counselors

also engage in legislative and policy actions that affect marginalized groups (Toporek &

Liu). Such lobbying can take the form of communicating with policy makers via letters,

emails, or telephone calls to express positions on social justice issues that impact mental

health (Shullman et al.). Another form of communication with legislators, which is

underutilized by counselors, includes attending town hall meetings and/or forums

organized by legislators (Shullman et al.) Using such forums, counselors are urged to

advocate for psychological knowledge and practice to be included in public policy

debates (Shullman et al.). Lastly, knowledge of the views, responsibilities, and needs of

policymakers is essential to effective lobbying (Galer-Unti & Tappe, 2006).

Finally, the social advocate acting within the social/political arena is encouraged

to maintain open dialogue with communities and clients to ensure that social/political

advocacy efforts are consistent with initial goals (Lewis et al., 2002). This can occur in

by conducting large- scale empirical investigations of advocacy work (Sexton &

Whiston, 1998). Ensuring that social/political advocacy is consistent with the goals of

those for whom one is advocating also necessitates the support of policies that

institutionalizes the perspectives of oppressed persons, such as affirmative action

(Adams, O’Brien, & Nelson, 2006).

27

Conclusions

A review of the multidisciplinary literature on advocacy skills yielded 74 skills

that can be classified according to the advocacy competencies set forth by the ACA

(Lewis et al., 2002). These behavioral skills were taken from the social justice research

and practice literature and can help to clarify and articulate training goals needed for

social advocates, and can help to assess the impact of various training methods on

facilitating counselors’ development of advocacy skills. Additionally, the wealth of skills

related to the competencies that were documented in the literature and easily classified

according to the ACA model demonstrates that many counselors and psychologists are

practicing social justice advocacy consistent with the guidelines. Overall, it also supports

the framework used for the Advocacy Competencies.

However, there was one area in which the advocacy literature was found to be

lacking, that of outcome research for advocacy efforts. More specifically, the literature

was silent with regards to assessing the outcome of a counselor’s interaction with a

community, assessing the effects of counselors’ advocacy efforts, using research data to

show the need for change, and assessing the impact of public information efforts. This is

understandable given the relatively new attention given to social justice research;

however, this gap is a critical one in terms of being able to assess the effectiveness of

one’s advocacy efforts on both the smaller scale of individual advocacy intervention and

on a larger scale. Additionally, the competencies of developing action plans for advocacy

and dealing with responses to change were found to be in need of attention from the field.

28

Currently, few counseling and counseling psychology programs provide formal

training in advocacy, although many engage in advocacy work (Toporek, et al., 2006).

Because this is a renewed force within the field, without formally established or

researched training guidelines, it is necessary for practitioners, educators, and supervisors

to follow the example in beginning to take steps in providing training in these skills.

Working with programs that have taken the lead in advocacy, such as Boston College,

George Mason University, and Oregon State University to develop and formally assess

curriculum is one step. McCrea et al. (2004) have also suggested that professional

conferences, such as those of Division 17 have and could continue to fill gaps in training

by offering actual training in advocacy. Furthermore, Fox (2003) has stressed the

importance of training counseling psychology students who wish to practice advocacy in

critical theories. Interdisciplinary training, involving networking and exchanging ideas

with other departments, such as Community Psychology and Women’s Studies is one

way that this can be achieved. Such collaborative efforts could also help to make the

work of counseling psychologists and their contributions more visible to the university

community.

As it stands, the majority of the literature on social advocacy is theoretical in

nature, with much of this being based upon counselor-advocates’ in-the-field work (Lee,

1998; Toporek, 2006). While this is an important contribution to the field, there is a bias

within the mainstream field of psychology for quantitative measurement and research.

Some advocacy scholars eschew quantitative methods of study and advocate in favor of

29

more transformative action research strategies. However, others insist that the toolbox

must be filled with various tools and that quantitative methodology can complement more

transformative methods of research (Borshuk & Cherry, 2004). In order to speak the

language of those who hold power (i.e., funding agencies, credentialing boards,

professional organizations), advocacy needs to be measurable. Through these means, the

utility of advocacy can be empirically tested, improved upon, and used to provide

alternatives to individualistic helping models.

This paper represents one step toward the realization of the operationalization and

measurement of advocacy skills. Future research aimed at developing methods of

advocacy outcome evaluation for one’s advocacy efforts, as well as to measure these

skills and to assess training outcomes would take the field further toward the realization

of social advocacy as a researchable professional activity for counseling psychologists.

References

Adams, G., O’Brien, L. T., & Nelson, J.C. (2006). Perceptions of racism in Hurricane

Katrina: A liberation psychology analysis. Analyses of Social Issues and Public

Policy, 6, 215-235.

Albee, G. W. (2000). The Boulder model’s fatal flaw. American Psychologist, 55, 247-

248.

American Psychological Association (2002). Ethical principles of psychologists and code

of conduct. American Psychologist, 57, 1060-1073.

American Psychological Association (2006). Advancing psychology in the public

interest: A psychologist’s guide to participation in federal advocacy process.

Retrieved Sept. 12, 2006, from http://www.apa.org/ppo/ppan/piguide.html

Aspy, C. B. & Sandhu, D. S. (1999). Empowering women for equity: A counseling

approach. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Benjamin, L. T., Jr., & Baker, D. B. (2004). From séance to science: A history of the

profession of psychology in America. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson

Learning.

Borshuk, C. & Cherry, F. (2004). Keep the tool-box open for social justice: Comment on

Kitzinger and Wilkinson. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 4, 195-202.

Brabeck, M., Walsh, M. E., Kenny, M., & Comilang, K. (1997). Interprofessional

collaboration for children and families: Opportunities for counseling psychology

in the 21

st

century. The Counseling Psychologist, 25, 615-636.

30

31

Brawley, E. A. (1995). Human services and the media: Developing partnerships for

change. Langhorn, PA: Harwood.

Brawley, E. A. (1997). Teaching social work students to use advocacy skills through

mass media. Journal of Social Work Education, 33, 445-460.

Brown, D. (1988). Empowerment through advocacy. In D. Kurpius & D. Brown (Eds.)

Handbook of consultation: An intervention for advocacy and outreach (pp. 8-17).

Alexandria, VA: Association for Counselor Education and Supervision.

Bryant-Davis, T., Ocampo, C. (2005). Racist incident-based trauma. The Counseling

Psychologist, 33, 479-500.

Chen-Hayes, S. F. (2001). Social justice advocacy readiness questionnaire. Journal of

Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 13, 191-203.

D’Andrea, M. (2005). Continuing the cultural liberation and transformation of counseling

psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 33, 524-537.

D’Andrea, M. & Daniels, J. (1999). Exploring the psychology of White racism through

naturalistic inquiry. Journal of Counseling and Development, 77, 93-101.

Deetz, S. (1992). Democracy in an age of corporate colonization: Developments in

communication and the politics of everyday life. Albany, NY: State University of

New York Press.

Delgado-Romero, E. A., Galvan, N., Maschino, P., Rowland, M. (2005). Race and

ethnicity in empirical counseling and counseling psychology research: A 10-year

review. The Counseling Psychologist, 33, 419-448.

32

Dinsmore, J. A., Chapman, A., McCollum, V. J. C. (2000, March). Client advocacy and

social justice: Strategies for developing trainee competence. Paper presented at

the Annual Conference of the American Counseling Association, Washington,

DC.

Duncan, C., Rivlan, D., & Williams, M. (1990). An advocate’s guide to the media.

Washington, D.C: Children’s Defense Fund.

Dworak-Peck, S. & Battle, M. G. (1988). Perspectives. NASW News, 33, 2.

Epstein, D., West, A. J., & Riegel, D. G. (2000). The Institute for Senior Action: Training

senior leaders for advocacy. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 33 (4), 91-

99.

Faltz, C. A. (2001). Making sense of psychology’s advocacy agenda. California

Psychologist, 34, 22-23.

Fassinger, R. E. (2000). Gender and sexuality in human development: Implications for

prevention and advocacy in counseling psychology. In S. Brown & R. Lent

(Eds.), Handbook of counseling psychology (3

rd

ed., pp. 346-378). New York:

Wiley.

Fassinger, R. E. (2002). Hitting the ceiling: Gendered barriers to occupational entry,

advancement, and achievement. In L. Diamant & J. Lee (Eds.), The psychology of

sex, gender, and jobs: Issues and solutions (pp. 21-46). Westport, CT:

Greenwood.

33

Fassinger, R. E., & Gallor, S. M. (2006). Tools for remodeling the master’s house. In R.

L. Toporek et al. (Eds.) Social justice in counseling psychology (pp. 256- 275).

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Fassinger, R. E. & O’Brien, K. M. (2000). Career counseling with college women: A

scientist-practitioner-advocate model of intervention. In D. Luzzo (Ed.), Career

development of college students: Translating theory and research into practice

(pp. 253-265). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Fouad, N. A., Gerstein, L. H., & Toporek, R. L. (2006). Social justice and counseling

psychology in context. In Toporek et al. (Eds.) Social justice in counseling

psychology (pp. 1-16). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Fouad, N. A., McPherson, R. H., Gerstein, L., Bluestein, D. L., Elman, N., Helledy, K. I.,

& Metz, A. J. (2004). Houston 2001: Context and legacy. The Counseling

Psychologist, 32, 15-77.

Foucalt, M. (1978). The history of sexuality (R. Hurley, Trans.). New York: Pantheon.

Foucalt, M. (1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.).

New York: Vintage.

Fox, D. R. (2003). Awareness is good, but action is better. The Counseling Psychologist,

31, 299-304.

Fraser, N. (1987). Unruly practices: Power, discourse and gender in contemporary social

theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

34

Frost, D. M. & Ouellette, S. C. (2004). Meaningful voices: How psychologists, speaking

as psychologists, can inform social policy. Analyses of Social Issues and Public

Policy, 4, 219-226.

Galer-Unti, R. A. & Tappe, M. K. (2006). Developing effective written communication

and advocacy skills in entry-level health educators through writing-intensive

program planning methods courses. Health Promotion Practice, 7, 110-116.

Goodkind, J. R. (2005). Effectiveness of a community-based advocacy and learning

program for Hmong refugees. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36,

387- 408.

Goodman, L. A., Liang, B., Helms, J. E., Latta, R. E., Sparks, E., & Weintraub, S. R.

(2004). Training counseling psychologists as social justice agents: Feminist and

multicultural principles in action. The Counseling Psychologist, 32, 793-837.

Hage, S. (2003). Reaffirming the unique identity of counseling psychology: Opting for

the “road less traveled by.” The Counseling Psychologist, 31, 555-563.

Hartung, P. J., Blustein, D. L. (2002). Reason, intuition, and social justice: Elaborating

Parson’s career decision making model. Journal of Counseling and Development,

80, 41-47.

Helms, J. E. (2003). A pragmatic view of social justice. The Counseling Psychologist, 31,

305-313.

Hepworth, D. H. & Larsen, J. A. (1993). Direct social work practice: Theory and skills.

Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

35

Hoefer, R. (2006). Advocacy practice for social justice. Chicago: Lyceum Books.

Ivey, A. E. & Collins, N. M. (2003). Social justice: A long-term challenge for counseling

psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 31, 290-298.

Ivey, A. E. & Ivey, M. B. (2007). Intentional interviewing and counseling (6

th

ed.).

Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Kiselica, M. S. (1995). Multicultural counseling with teenage fathers: A practical guide.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kiselica, M. S. (2004). When duty calls: The implications of social justice work for

policy, education, and practice in the mental health professions. The Counseling

Psychologist, 32, 838- 854.

Kiselica, M. S. & Pfaller, J. (1993). Helping teenage parents: The independent and

collaborative roles of school counselors and counselor educators. Journal of

Counseling and Development, 72, 42-48.

Kiselica, M. S. & Robinson, M. (2001). Bringing advocacy counseling to life: The

history, issues, and human dramas of social justice work in counseling. Journal of

Counseling & Development, 79, 387-397.

Lee, C. C. (1998). Counselors as agents of social change. In C. C. Lee & G. R. Walz

(Eds.), Social action: A mandate for counselors (pp. 3-14). Alexandria, VA:

American Counseling Association and ERIC Clearinghouse.

Lerner, R. M. (2002). Concepts and theories of human development (3

rd

ed.). Mahwah,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

36

Lewis, J., Arnold, M. S., House, R., & Toporek, R. (2002). Advocacy Competencies:

American Counseling Association Task Force on Advocacy Competencies.

Retrieved May 27, 2006, from

http://counselorsforsocialjustice.org/advocacycompetencies.html

Lewis, J., Arnold, M. S., House, R., & Toporek, R. (2005). ACA presentation.

McCrea, L. G., Bromley, J. L., McNally, C. J., O’Byrne, K. K., & Wade, K. A. (2004).

Houston 2001: A student perspective on issues of identity, training, social

advocacy, and the future of counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist,

32, 78-88.

McWhirter, E. H. (1994). Counseling for empowerment. Alexandria, VA: American

Counseling Association.

McWhirter, E.H. (1997). Empowerment, social activism, and counseling. Counseling

and Human Development, 29, 1-14.

Morrow, S. L. (2007). Qualitative research in counseling psychology: Conceptual

foundations. The Counseling Psychologist, 35, 209-235.

National Board for Certified Counselors (2008). NBCC code of ethics. Retrieved on Oct.

28, 2008 from http://www.nbcc.org/ethics2.

National Commission for Health Education Credentialing, Inc. (1999). A competency

based framework for graduate-level health educators. Allentown, PA: Author.

O’Brien, K. M., Patel, S., Hensler-McGinnis, N., & Kaplan, J. (2006). Empowering

undergraduate students to be agents of social change: An innovative service

37

learning course in counseling psychology. In Toporek et al. (Eds.) Social justice

in counseling psychology (pp. 59-73). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Pickren, W. E. (2004). Fifty years on: Brown v. Board of Education and American

psychology, 1954-2004: An introduction. American Psychologist, 59, 493- 494.

Ritvo, R., Al-mateen, C., Ascherman, L., Beardslee, W., Hartmann, L., Lewis, O.,

Papilsky, S., Sargent, J., Sperling, E., Stiener, G., Szigethy, E. (1999). Report of

the Psychotherapy Task Force of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 8 (2), 93-102.

Rivera, E. T. (2006/March). The future of CSJ. CSJ Activist, 6 (2). 1-4.

Roysircar, G. (2006). A theoretical and practice framework for universal school-based

prevention. In Toporek et al. (Eds.) Social justice in counseling psychology (pp.

130-145). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Rudolf, M. (2003). Advocacy training for pediatricians: The experience of running a

course in Leeds, United Kingdom. Pediatrics, 112, 749-751.

Saxena, S., Lora, A., van Ommeren, M., Barrett, T., Morris, J., & Saraceno, B. (2007).

WHO’s assessment instrument for mental health systems: Collecting essential

information for policy and service delivery. Psychiatric Services, 58 (6), 816-821.

Sexton, T. L. & Whiston, S. C. (1998). Using the knowledge base: Outcome research and

accountable social action. In C. C. Lee & G. R. Walz (Eds.), Social action: A

mandate for counselors (pp. 241-260). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling

Association.

38

Shullman, S. L., Celeste, B. L., Strickland, T. (2006). Extending the Parsons legacy. In

Toporek et al. (Eds.) Social justice in counseling psychology (pp. 499-513).

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Smith, M. J. (1975). When I say no, I feel guilty. New York: Bantam Books.

Speight, S. L. & Vera, E. M. (2004). A social justice agenda: Ready or not? The

Counseling Psychologist, 32, 109-118.

Stringfellow, J. W. & Muscari, K. D. (2003). A program support for consumer

participation in systems change. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 14, (3), 142-

147.

Talleyrand, R. M., Chung, R. C. -Y., & Bemak, F. (2006). Incorporating social justice in

counselor training programs: A case study example. In Toporek et al. (Eds.)

Social justice in counseling psychology (pp. 44-58). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications.

Thompson, C. E., Alfred, D. M., Edwards, S. L., & Garcia, P. G. (2006). Transformative

endeavors. Implementing Helm’s racial identity theory to a school-based heritage

project. In Toporek et al. (Eds.) Social justice in counseling psychology (pp. 100-

116). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Toporek, R. L. (2000). Developing a common language and framework for understanding

advocacy in counseling. In J. Lewis & L. Bradley (Eds.), Advocacy in counseling:

Counselors, clients & community (pp. 5-14). Greensboro, NC: ERIC

Clearinghouse on Counseling and Student Services.

39

Toporek, R. L. (2001). Context as a critical dimension of multicultural counseling:

Articulating personal, professional, and instituting competence. Journal of

Multicultural Competence, 29, 13-30.

Toporek, R. L., Gerstein, L. H., Fouad, N. A., Roysircar, G. & Israel, T. (2006a).

Handbook for social justice in counseling psychology: Leadership, vision, and

action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Toporek, R. L., Gerstein, L. H., Fouad, N. A., Roysircar, G. & Israel, T. (2006b). Future

directions for counseling psychology. In R. L. Toporek et al. (Eds.) Handbook for

social justice in counseling psychology: Leadership, vision, and action, (pp. 533-

552). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Toporek, R. L. & Liu, W. M. (2001). Advocacy in counseling: Addressing race, class,

and gender oppression. In D. B. Pope-Davis & H. L. K. Coleman (Eds.), The

intersection of race, class, and gender in multicultural counseling (2

nd

ed., pp.

165-188). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Toporek, R. L. & McNally, C. J. (2006). Social justice training in counseling psychology.

Needs and innovations. In R. L. Toporek, L. H. Gerstein, N. A. Fouad, G.

Roysircar, & T. Israel (Eds.), Handbook for social justice in counseling

psychology. Leadership, vision, and action (37-43). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications.

Toporek, R. L. & Williams, R. A. (2006). Ethics and professional issues related to the

practice of social justice in counseling psychology. In R. L. Toporek, L. H.

40

Gerstein, N. A. Fouad, G. Roysircar, & T. Israel (Eds.), Handbook for social

justice in counseling psychology. Leadership, vision, and action (17-34).

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Trethewey, A. (1997). Resistance, identity, and empowerment: A postmodern feminist

analysis of clients in a human service organization. Communication Monographs,

64, 281- 301.

Vacc, N. A., (1998). Fair access to assessment instruments and the use of assessment in

counseling. In C. C. Lee & G. R. Walz (Eds.), Social action: A mandate for

counselors (pp. 179-198). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Vera, E., Daly, B., Gonzales, R., Morgan, M., & Thakral, C. (2006). Prevention and

outreach with underserved populations. In R. L. Toporek, L. H. Gerstein, N. A.

Fouad, G. Roysircar, & T. Israel (Eds.), Handbook for social justice in counseling

psychology. Leadership, vision, and action (86- 99). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications.

Vera, E. M. & Shin, R. Q. (2006). Promoting strengths in a socially toxic world:

Supporting resiliency with systemic interventions. The Counseling Psychologist,

34, 80-89.

Williams, R. L. & Kirkland, J. (1971). The White counselor and Black client. The

Counseling Psychologist, 2, 114-117.

Wyatt, G. (1990). Sexual abuse of ethnic minority children: Identifying dimensions of

victimization. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice, 21, 38- 342.

CHAPTER 2

DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE

SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCACY SKILLS SURVEY

41

42

DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE

SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCACY SKILLS SURVEY

In 2002, the American Counseling Association developed a listing of 43

competencies necessary for engagement in advocacy (Lewis, Arnold, House, & Toporek,

2002). The creation of this document has represented a much- needed step toward