, ,

I

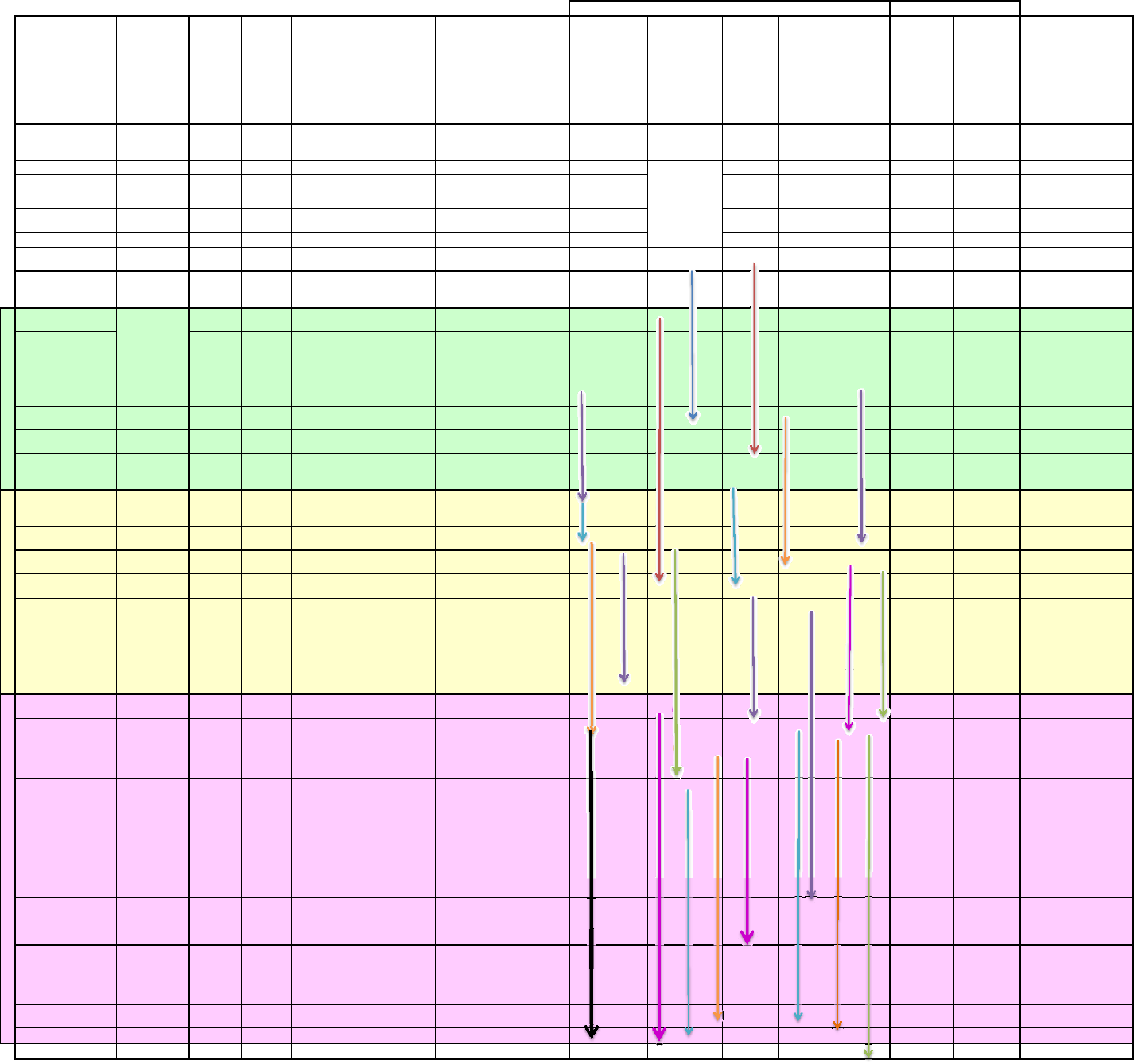

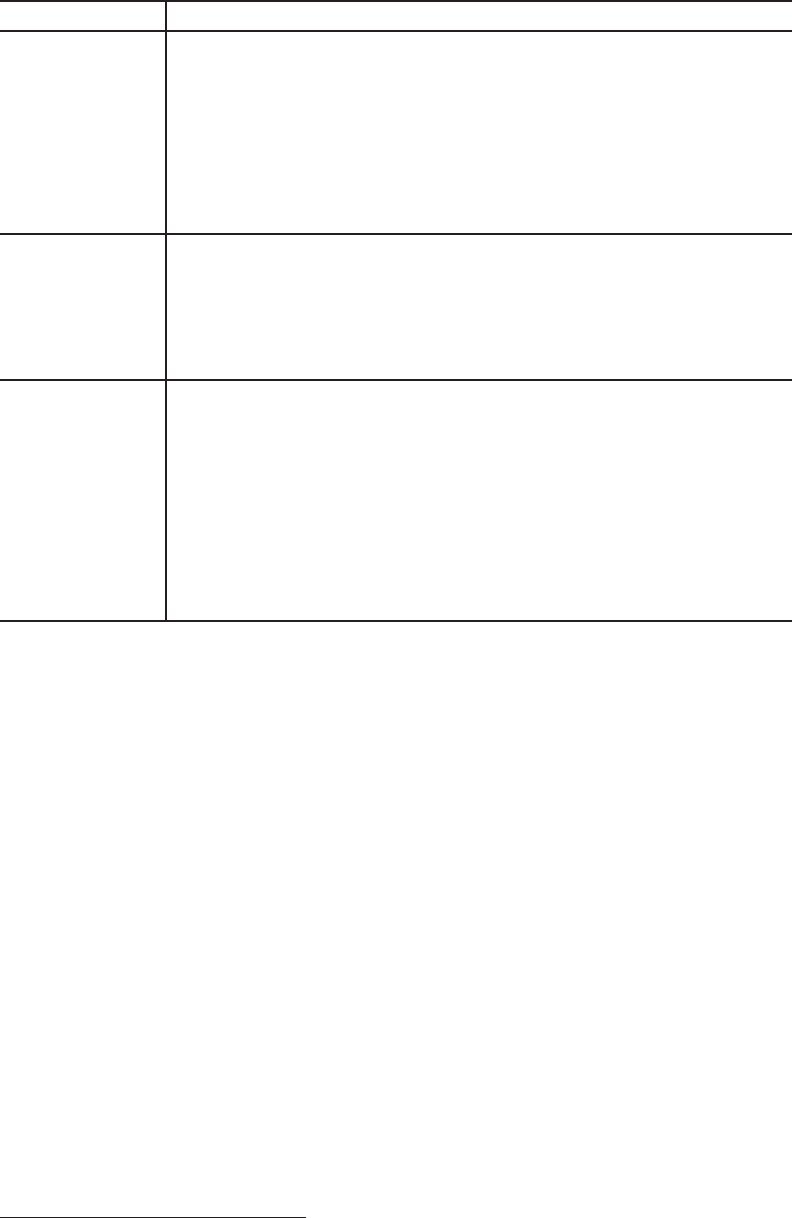

Madagascar Environmental Interventions Time Line

Mad popn Political situation

GNI per

capita and

GDP Growth

# interntl

visitors

Significant Policy measures Institutional measures

Policy oriented

Interventions

Parks and Reduce

Pressures on

resources

Governance

Health, Economics,

Infrastructure projects

Environment,

Economic

Growth, DG,

other **

Total p.capita

% of total

USAID Mad

funds

Health, food

aid, disaster

and famine

assistance**

Total p.capita

%

of to

tal

USAID Mad

funds

Other

1984 9,524,414

Ratsiraka

$

340 2% 12,000

Malagasy strategy for Conservation

and Development adopted

PL 480 funded micro‐

projects

1985 9,778,464

Ratsiraka

$310 1%

International Conference

1986 10,047,896

Ratsiraka

$290 2%

1st national survey of Mad protected

areas

1987 10,332,258

Ratsiraka

$260 1%

NEAP discussions begin with World

Bank

1988 10,631,581

Ratsiraka

$240 3%

Fonds Forestier National

1989 10,945,312

Ratsiraka

$220 4%

Ranomafana Park created DEBT for NATURE

PVO‐NGO

NRMS

1990 11,272,999

Ratsiraka

$230 3% 40,000

Madagascar Environmental Charter

and NEAP become official

Creation ONE, ANAE, ANGAP

$16.5m $1.50

%89

$2.1m $0.20

11%

35% Primary school

completion rate

1991 11,614,758 $210 ‐6%

Multi‐donor secretariat created in

DC

SAVEM $11.3m $1.00

%60

$7.6m $0.70

%40

1992 11,970,837 $230 1%

Mad signs Framework Convention

on Climate Change (FCC)

DEAP put in place; ONE becomes

operational

$41.8m $3.50

%87

$6.0m $0.50

%13

popn growth rate 2.8%;

contraceptive prevalence

rate (CPR) for modern

methods 5%

1993 12,340,943 $240 2%

KEPEM

APPROPOP

$44.5m $3.60

92%

$4.0m $0.30

8%

1994 12,724,636 Zafy $240 0%

D/G Creation Min of Env

CAP

$28.5m $2.20

%88

$3.8m $0.30

%12

USAID funds to Madagascar

EP I :

$49m*

USAID supported Interventions (projects > ~$1m)

Crisis

10 month

General Strike

Political

instability

Protected Area

Management Project

and Conservation

Through

Development at

several PAs

y

CAP

%88

%12

1995 13,121,371 Zafy $240 2% 78,000

Law on Foundations Ranomafana Park Mgmt plan

$26m $2.00

$89

$3.2m $0.20

%11

1996 13,531,083 Zafy $250 2% 83,000

Banking and currency reforms

GELOSE law

Tany Meva Created; ANGAP starts

managing Isalo PA

RARY

$15.1m $1.10

81%

$3.5m $0.30

19%

44 Protected Areas, 1.4m

ha, 2.3% total land area

1997 13,953,183

Ratsiraka

$260 4% 101,000

Forestry Law

ANGAP begins managing 7 PAs;

Madagascar delegation attends

CITES Conference

MITA

$14.5m $1.00

%80

$3.7m $0.30

20%

Contraceptive Prevalence

Rate (CPR) 10%

1998 14,385,954

Ratsiraka

$260 4% 121,000

Constitutional Revision;

Decentralization

MIRAY LDI

$19.9m $1.40

73%

$7.5m $0.50

27%

1999 14,827,223

Ratsiraka

$250 5% 138,000

Environment/Economic Growth;

MECIE

(

rev

)

ado

p

ted

PAGE

EHP JSI

$11.9m $0.80

50%

$11.9m $0.80

50%

2000 15,275,362

Ratsiraka

$250 5% 160,000

Strategy for Poverty Reduction

(PSRP)

Sustainable Financing

Commission

ILO

$13.8m $0.90

55%

$11.5m $0.80

45%

36% primary school

completion rate

2001 15,729,518

Ratsiraka

$270 6% 170,000

Provincial Governors put in place:

Rural Development Action Plan;

Gestion Contractualisée des Forêts

(GCF); Code de Gestion des Aires

Protégées (COAP)

International workshop on

Sustainable Financing

FCER RECAP

$15.3m $1.00

35%

$28.3m $1.80

65%

2002 16,189,796

Crisis

$240‐13% 62,000

Presidential decree banning fires

$11.9m $0.70

38%

$19.7m $1.20

62%

2003 16,656,727

Ravalomanana

$290 10% 139,000

Durban Vision announced; Kyoto

Protocol ratified

Durban Vision Group; Min of Env

and DEF merge

MENABE

$14.3m $0.90

35%

$26.2m $1.60

65%

CPR 18% (27% urban, 16%

rural)

2004 17,131,317

Ravalomanana

$300 5% 229,000

Regions created; Protected Areas

Code; MECIE (2); Conservation

Priority Setting exercise; Law on

Foundations Revised

BIANCO created JARIALA PTE MIARO MISONGA

BAMEX Santenet I and II

$12.5m $0.70

34%

$24.1m $1.40

66%

2005 17,614,261

Ravalomanana

$310 5% 277,000

Madagascar ratifies Kyoto Protocol;

New Forestry Policy (incl creation of

regional forest commissions)

SAPM ministerial Order; new Mining

Code; first approval of sale of carbon

credits by MoE; new Protected Areas

Code; Madagascar signs MCA

compact

FAPBM created

ERI

GDA/LARO

$11.4m $0.60

29%

$27.4m $1.60

71%

58% primary school

completion rate

:

$33.45m

EP II:

$41m +$8.9m cyclone relief

E

compact

2006 18,105,439

Ravalomanana

$300 5% 312,000

Poverty reduction stra tegy paper;

MAP; Forest fire management

system; new Tenure Policy

$12.7m $0.70

26%

$37m $2.00

74%

2007 18,604,365

Ravalomanana

$340 6%

$9.8m $0.50

17%

$48.3m $2.60

83%

Protected areas represent

3% of Madagascar's land

mass with intention to

double to 6% by 2012

2008 19,110,941

Ravalomanana

$410 7% 345,000

11.8m $0.60

21%

$43m $2.20

79%

2009

Crisis

156,000

2010

EP III

NB Recent apparent improvements in PC income are somewhat misleading when it comes to economic growth and its impact on resource use since, as pointed out in rece nt World Bank documents, almost none of this income growth has been transferred to remote rural areas where there is the most agricultural pressure on forest

resources; Dates are intended to indicate general flow of events and are not precise in terms of months or partial years; where policies are concerned there may be minor discrepancies depending on when law was voted and decrees were actually issued.

social and economic indicators from the World Bank quick query site .

* USAID Env/RD program funding (source L Gaylord personal communication)

** USAID funding levels are approximate and based on information provided by Barbara Dickinson (from USAID loans and grants Greenbook); They do not include $104m of Millenium Challenge Corporation Funds (2005‐2008)

Dates of laws vary due to imprecisions concerning when the law was actually voted, decrees promulgated, etc.

Project dates are approximate

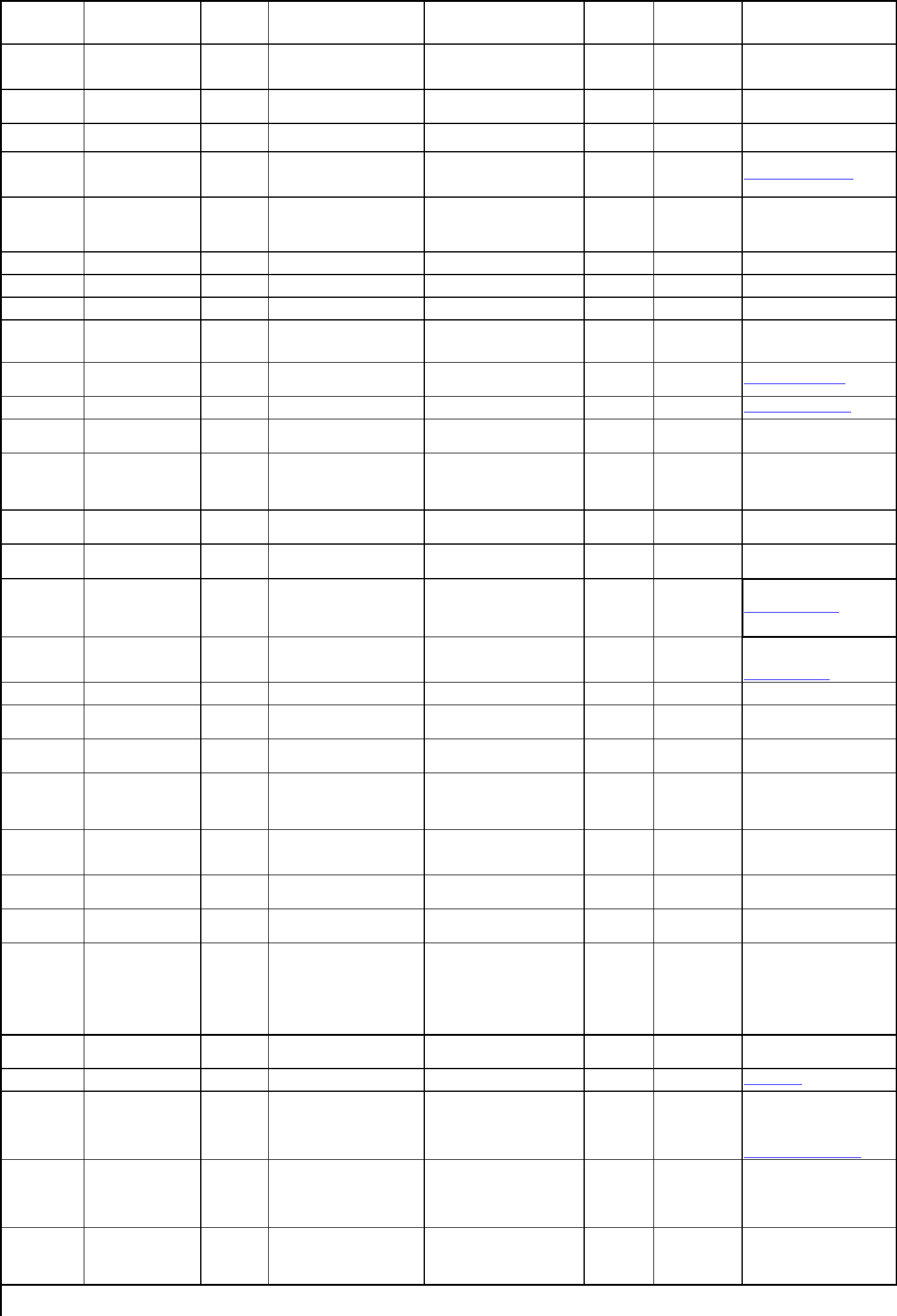

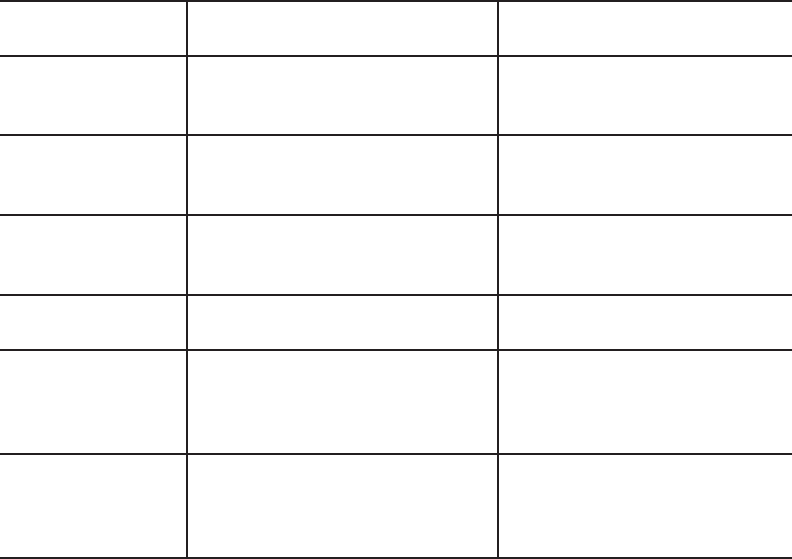

USAID Projects Madagascar 1984‐2009

This is a partial list of projects, focusing on those most closely related to environmental concerns

Project Initials Project Name Years Focus or interventions Implementing Partner(s)

Approximate

Funding level

Funded under

USAID sector or

Partner

web site

Conservation‐Development

Operational Program Grants

1988‐1994

Test linkages between conservation and

development in 4 PAs

WWF, Duke University and North Carolina

State, Missouri Botanical Garden

$4.1m

Operational Program

Grants

Debt‐for‐Nature 1989‐2002

Training nature protection agents; forest

management transfers

WWF

$2.5m from

USAID

Debt for Nature

PVO‐NGO NRMS

Natural Resources

Management Support

1989‐1995 Reinforce NGO capacity World Learning, CARE, WWF

$.21m (for

Madagascar)

centrally funded

(NGO/PVO‐NRMS)

SAVEM

Sustainable Approaches to

Viable Environmental

Management

1991‐2000

National Park Management, strengthen

ANGAP, ICDPs around 7 PAs

TRD (Institutional support to ANGAP),

PACT with major subgrants (ICDP) to WWF,

VITA, CARE, SUNY‐Stonybrook,CI, ANGAP

$26.6m +

$13.4m

Contract and

cooperative agreement

www.pactworld.org/cs/savem

KEPEM

Knowledge and Effective

Policies for Environmental

Management

1993‐1997

(implementation

delayed by the

political crisis)

Policy and Institutional strengthening :

ONE

ARD

$33m

(non‐project

assistance) + $9m

project assistance

Contract, budget

support to GoM

TRADEM

1991‐1995

Commercialization of natural resource

p

roducts

~$0.5m Agriculture and NRO

APPROPOP

Madagascar Population

Su

pp

ort Pro

j

ect

1993‐98 family planning support around ICDPs Management Sciences for Health Health

CAP

Commercial Agriculture

Promotion Pro

j

ect

1994‐1999 Economic growth poles Chemonics International $24.2m

Economic Growth

Contract

MITA (PEI‐PEII

Transition

Project)

Managing Innovative

Transitions in Agreement

1997‐1998 Support for ANGAP decentralization PACT/Forest Management Trust $3m

Environment/RD

cooperative agreement

RARY

Rary means "to weave" in

Malagasy

1996‐2000

Public debate of complex economic and

social policy questions

PACT ??? Governance www.pactworld.org/cs/rary

MIRAY

Miray means "to be united" in

Mala

g

as

y

1998‐2004

Develop national capacity to manage

p

rotected areas

PACT, WWF, CI $12.3m www.pactworld.org/cs/miray

JSI

Jireo Salama Isika 1999‐2003

child survival, nutrition, STD, family

planning at the community and service

deliver

y

level

John Snow International Research and

Training

$16.8m Health

LDI (followed by

PTE during the

transition to ERI)

Landscape Development

Interventions

1998‐2004

Eco‐regional activities to conserve the

forest corridors and improve the well‐

being of farmers living near those

corridors

Chemonics International $22m

Environment‐Rural

Development

PAGE

Environmental Management

Support Project

1999‐2002

Environmental policy and institutional

strengthening

IRG/Winrock, Harvard Insitute for

International Development

$6.2m EPIQ

EHP II

Environmental Health Project 1999‐2004

monitoring and evaluation of linked

interventions in the field

AED $1.2m

USAID/Washington

Global Health Bureau

ILO

Ilo means "light" in Malagasy 2000‐2003 Capacity building for civil society PACT, Cornell

$2.4m

(governance) +

$.57m (election

monitoring)

D/G Cooperative

Agreement

www.pactworld.org/cs/ilo

MGHC

Malagasy Green and Healthy

Communities

2001‐2007

Supported Malagasy NGO Vohary Salama;

worked on health, population,

environment, and income generation

activities

John Snow International Research and

Training

$728,000 Packard Foundation

www.voharysalama.org

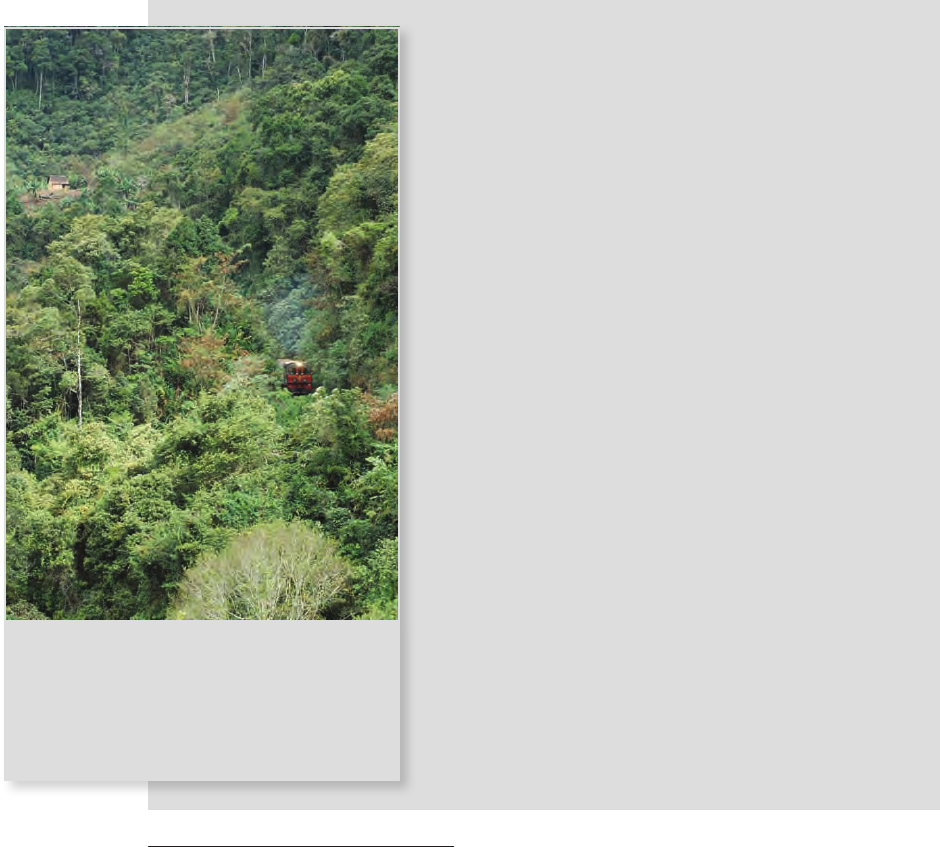

FCER

FCE Railway Rehabilitation 2001‐2005

Rehabilitate the FCE railway after 2000

c

y

clones

Chemonics International $4.7m

Supplenental cyclone

funds

RECAP

Rehabilitate CAP roads (roads

built by the CAP project)

2001‐2005

Rehabilitate farm to market roads in LDI

intervention areas after 2000 cyclones

Chemonics International $5.5m

Supplenental cyclone

funds

BAMEX

Business and Market

Expansion

2004‐2008 Economic benefits and value chains Chemonics International $5.3m

Environment/Economi

c Growth MOBIS

ERI

Eco‐Regional Initiatives 2004‐2009

Eco‐regional activities to conserve the

forest corridors and improve the well‐

being of farmers living near those

corridors

DAI $2.0m

Environment/RD

MOBIS

SanteNet I

Health Network 2004‐2008

Increasing demand, availability, and

quality of select health and FP products

and services (cte and national level)

Chemonics International 16.5m Health Contract

QMM‐USAID GDA

(LARO)

Linking Actors Regional

Opportunities

2003‐2005‐2008

Program to mitigate negative social and

environmental consequences of the

Qitfer mine

PACT, PSI, CARE

$3m QMM; $3m

USAID

Joint funding

Qitfer/USAID central

fundin

g

EMI

Extra Mile initiative 2005‐2008

Increase remote rural community

(including those adjacent to threatened

forests

)

access to FP

CARE, JSI, R&T $225,000 Health Central Funding

Menabe

Menabe Biodiversity Corridor 2003‐2010

Build forest connectivity through

management and revenue‐generating

incentives including eco‐tourism

CI $3m ??

Cooperative

Agreement through

Biodiversity Corridor

Planning and

Implementation

Program

MIARO

Protect (in Malagasy) 2004‐2009

Expansion of Protected Area Network

through co‐management

CI, with subgrants to WCS, WWF, ANGAP $6.3m

Environment/RD

Cooperative

A

g

reement

Jariala

Forest Management (in

Mala

g

as

y

)

2004‐2009

Policy and Institutional support (esp

reform of DGEF)

IRG $12.2m

Environment/RD

contract

www.jariala.org

MISONGA

Managing Information and

Strengthening Organizations

for Networked Governance

Approaches

2004‐2006

(ended 2 years

early when

money ran out)

promote civil society, improve

information flows between citizenry and

government, improve government

responsiveness, reduce corruption

PACT, CRS $8.2m initially

Environment/RD and

D/G funding

www.pactworld.org/cs/misonga

VARI

Utilizing small‐scale irrigation

systems for household and

market‐oriented agricultural

production in Anosy Region

2006‐2009

Farmer to farmer extension, technical

assistance for water management and

farming systems

CARE $.59m

Cooperative

Agreement

VAHATRA

Laying Foundation for Strong

Local Governance and

Livelihoods Security

2007‐2009

Build commune capacity around a shared

watershed, with attention on improving

environment, food security and livelihood

sitatuations.

CRS $.19m

Cooperative

Agreement

In 2005, Madagascar signed a compact with MCA for a $110m project over four years. The three focus areas were : land tenure reform, financial sector reform, and agricultural business development.

The program was terminated in 2009 due to the political crisis.

Please note : these are not official funding levels and should be considered approximate. There is no standard system in USAID for documenting project funding levels/expenditures and it was difficult to obtain comparable information.

PARADISE LOST?

LESSONS FROM 25 YEARS OF USAID

ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMS IN MADAGASCAR

Written by Karen Freudenberger

July 2010

Prepared by:

International Resources Group

1211 Connecticut Ave. Suite 700

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 289-0100

DISCLAIMER

This publication is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States

Agency for International Development (USAID.). It was prepared by International Resources Group

(IRG).The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reect the views of the

United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

CONTENTS

Foreword . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .V

A Brief History of NEAP, the Environment Programs,

Community-based natural resource management

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . VII

Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . IX

List of Acronyms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . XI

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

and USAID Interventions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

The National Environmental Action Plan ............................. 7

The Environmental Programs.............................................................................. 8

USAID Interventions ........................................... 10

Mission history .................................................................................................... 10

An overview of USAID’s environmental projects........................................ 13

Partnerships ....................................................................................................... 18

Overall major accomplishments...................................................................... 24

USAID’s approach ............................................................................................. 27

Policies and Institutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Improved, environmentally friendly policy framework.................. 31

Institutional strengthening ....................................... 33

Environmental Institutions and Structures.................................................... 33

Sustainable Financing .......................................................................................... 38

Discussion ........................................................................................................... 40

Protected Area Designation and Management . . . . . . . . . . . 43

The National Parks ............................................. 43

The Durban Vision/SAPM ........................................ 44

Operationalizing the Vision ............................................................................... 45

Discussion............................................................................................................. 47

(CBNRM): co-management....................................... 48

Discussion............................................................................................................. 51

Reducing Pressures on Resources by Surrounding Communities . 53

ICDPs ....................................................... 53

The Eco-regional approach....................................... 54

Persuading farmers to abandon tavy.......................................................................55

Fire.......................................................................................................................... 59

Discussion............................................................................................................. 60

Efforts to align conservation and livelihood objectives ................. 60

Payments for Ecosystem Services ................................................................... 62

Discussion............................................................................................................. 64

Stepping Back:Assessing Results in Terms of the Overall Impact on

Increasing Chinese (and other non-Western Investment)

Firewood and construction wood exploitation ....................... 65

Valorizing Natural Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

Commercial forest exploitation ................................... 67

Natural Products Markets ....................................... 69

Eco-tourism. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

Governance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

Problematic characteristics of malagasy governance ................... 73

Business as usual ................................................................................................. 73

Are crises normal?.............................................................................................. 75

Local Government ............................................. 76

Civil Society .................................................. 77

Characteristics of Malagasy civil society........................................................ 77

USAID efforts to strengthen civil society...................................................... 78

Civil society, politics, and fear........................................................................... 80

Governance and the environment ................................. 80

Discussion............................................................................................................. 82

Madagascar’s Natural Environment. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

The bottom line ............................................... 85

With so many positive results, why haven’t we saved the forests? ........ 86

Scaling up: the logic............................................................................................. 86

Scaling down: the reality .................................................................................... 87

The economy ....................................................................................................... 87

Is Madagascar different? ........................................ 88

Externalities .................................................. 90

Climate Change................................................................................................... 90

in Madagascar....................................................................................................... 91

U.S. politics and aid policies ...................................... 93

What Next? .................................................. 94

Three scenarios ................................................................................................. 95

Conclusion ................................................... 98

Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

FOREWORD

As my three years in Madagascar draw to a close, I am experiencing a mixture of emotions, ranging

from hope to despair. I vividly recall how I felt coming here in 2007, full of optimism and excitement

about great possibilities for Madagascar, after too many years of missed opportunities for prosperity,

progress, growth, and development. I came with a particular enthusiasm for the apparent dawning

of a new age of protecting and appreciating Madagascar’s unparalleled biodiversity, and I was

particularly eager to contribute to that momentum. Indeed, many different considerations brought

me to Madagascar, but none was stronger than my desire to contribute to safeguarding the Grand

Isle’s irreplaceable environmental treasure chest.

Today, after months of unexpected turmoil and crisis, I still maintain hope that Madagascar will

soon see a return to political stability and constitutional order. This is necessary for the sake of the

long-suffering Malagasy people, and it is also necessary for the security of Madagascar’s once again

threatened environment. These resurgent environmental threats constitute a full-blown “crisis within

a crisis,” one that threatens Madagascar’s long-term prosperity and viability at least as much as the

surrounding political crisis. The world needs to pay attention to both, before Madagascar goes

the way of Easter Island, Haiti, and other fragile, unique island environments already destroyed by

mankind.

My friend Karen Freudenberger has done a monumental job capturing in this document the

complex, rich and important work of USAID over the last 25 years. Insights from her many years

living and working in Madagascar are evident throughout this report. The achievements -- and the

shortcomings -- of the programs supported by the U.S. government are important ones to reect

upon. I hope that donors, partners and policy-makers, international and Malagasy, will ruminate on

the lessons, questions and suggestions offered in this study, in order to transform future efforts into

richer, deeper, and more durable successes.

Anyone who reads this document will see that there is still so much more work to be done. They

will also see that while we have made some gains over the years, they have been fragile. Often,

these “successes” have constituted the mere slowing of destructive processes, rather than their

permanent reversal. So we are very far from winning this critical battle to secure productive natural

resources and our globally important heritage. International NGOs, local civil society organizations,

civil servants and communities have continued to push forward and support the cause of healthy

and sustainable management of Madagascar’s wonderfully important natural resources despite

the temporary suspension of donor support, an evident lack of political will, and increasingly

difcult circumstances. They are to be lauded for their persistence and dedication. But they need

signicantly more help.

Since the coup d’état in March 2009, biodiversity-rich sites and the local communities that are

dependent upon them have been under attack by unscrupulous proteers seeking to take advantage

of a general breakdown in law and order and other governance systems to extract the country’s

natural resources, particularly its precious hardwoods and minerals. While not new, this illegal logging

has now reached unprecedented levels, with reports indicating that nearly 7000 cubic meters per

month -- or approximately 400 trees per day – are being cut in some regions. I am told that the

problem is at least 20-fold more acute than ever before.

And where there is illegal logging, there are other illegal activities. Threatened animals, including

several particularly endangered species of rare lemurs and tortoises, are being captured for export

and for food at rates that ensure their extinction in the wild, unless this trend can be reversed.

V

These plants and wildlife are found nowhere else on earth. Prots reaching local poachers and

foresters amount to mere pennies on every dollar, and the total value of lost resources is far inferior

to the cost of restoring them. Furthermore, monies gained from these illegal activities are laundered

through Madagascar’s nancial systems, further undermining local and national economies and

integrity.

We ALL need to recognize that Madagascar is being mined to death, not just for minerals but for

every resource found here. As Prince Phillip said famously 25 years ago,“Madagascar is committing

national suicide.” Sadly, this is as true today as it was then, just as USAID started it pioneering path

toward heightened environmental awareness and political engagement in support of sustainable

development here.

If continued unchecked, the current level of unsustainable resource extraction and environmental

degradation will undermine post-conict recovery and future economic growth potential for the

country. This ultimately will exacerbate poverty and food insecurity for the growing population

and accelerate the irreversible loss of biodiversity so unique to Madagascar. The ongoing illegal

logging and mineral extraction for export may signicantly limit options for future development in

agriculture, forestry, mining, and tourism, all key to promoting and achieving economic stability and

sustainability in the country.

Additionally, the ability of forests to serve their essential functions of water retention and ltration

is being impacted. There are important implications of these ecosystem services on an island

where nearly half of the population obtains water from surface water sources, and only 23 percent

of the population has access to clean drinking water. The immediate erosion of forests leads to

sedimentation of rivers and streams. And, as downstream siltation of rice and other agricultural elds

becomes more severe, the livelihoods and nutrition of Malagasy people are threatened.

The outlook for the near future is increasingly somber. The Malagasy people have difcult choices to

make to secure for themselves a more stable future. It will take courage and commitment to break

the current state of inertia. It will take vision, dedication, selessness, and a commitment to good

governance to map a sustainable future for not only a select few, but for the Malagasy nation as a

whole.

In spite of all these daunting challenges, I am encouraged to see that in many rural communities

where USAID and others have worked for years, the local populations themselves are stepping

up to defend their surrounding environment: they know more than anyone what is at stake. I am

further encouraged to see the strengthening of Malagasy civil society working in an organized fashion

for the environment: this was unknown here a quarter century ago, and is another important gain to

build upon. The U.S. government, primarily through USAID, has stood by the Malagasy people with

its humanitarian programs throughout this latest crisis. We also stand ready to resume our historic

support for programs that secure a healthy Malagasy environment for the benet of its people. If

we can restart these programs soon, perhaps it will not be too late. But this, in turn, will depend on

progress agreed to by Malagasy political leaders – progress that has been sadly slow in coming.

Niels Marquardt, US Ambassador to Madagascar, 2007-2010

VI

PREFACE

This is an opportunity I wish had not been presented to us. Following Madagascar’s unconstitutional

change in government in March 2009, USAID foreign assistance to Madagascar was thrown into

limbo resulting ultimately in the suspension of our environmental programs in Madagascar.

At the time, some existing agreements and contracts were reaching their natural conclusion and

USAID was in the process of launching a fresh set of initiatives with traditional and new partners.

The Bureau for Africa under the Biodiversity Analysis and Technical Support (BATS) program had

recently completed an Environmental Threats and Opportunities Assessment as part of a year-

long reection between USAID and its partners.This process culminated in a national stocktaking

workshop in August 2008.

Absent the suspension, the next generation of USAID support to the conservation of biodiversity

in Madagascar was poised to begin. Instead, because of the suspension, it was incumbent on us to

gather our experience before people, products, and partnerships were dissipated to the four winds.

The purpose of this assignment was to conduct a 25-year retrospective of USAID support to the

conservation of biological diversity in Madagascar, assess the current situation, and help launch a

wider discussion of how USAID might respond when and if the ability to re-engage with Madagascar

presents itself.

BATS has taken a lead role in reviewing USAID’s conservation experience in Africa, understanding

lessons learned, and charting the way forward. Reports to date include: Protecting Hard-won

Ground: USAID Experience and Prospects for Biodiversity Conservation in Africa; USAID Support

to the Community-based Natural Resource Management Program in Namibia: LIFE Program Review,

and A Vision for the Future of Biodiversity in Africa.This paper is the most recent product in that

series.

USAID recently decided to more systematically assess the impact of its programs and to make that

information more broadly available. Such transparency will facilitate exchanges of information and

allow us to learn from one another.This effort precedes that commitment but is fully consistent with

it.

International Resources Group (IRG) was one of our implementing partners in Madagascar, leading

the 2004-2009 effort in policy and institutional support. As such, it is well qualied to lead the study.

Karen Freudenberger, author of the study, has long and diverse experience in Madagascar and in

the rest of the world. A specialist in participatory research, her interviewing and research skills will

be quickly apparent to the reader.The rst draft was presented to a workshop in Washington, DC,

where a wide variety of people currently or historically active in Madagascar participated. A later

draft was reviewed by an even larger community of practitioners.

I am proud to present this paper to you.

Tim Resch, Bureau Environmental Advisor

USAID Bureau for Africa, Ofce of Sustainable Development

VII

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Just as USAID’s work in Madagascar has been the result of a massive collaborative effort, so also

has my attempt to capture the results of that effort depended on many generous collaborators.

My apologies, rst and foremost, to the many people I was not able to contact in the course of this

research, and particularly the enormous number of Malagasy colleagues who have contributed so

mightily to this cause but were not easy to nd from my current perch in Vermont. Please do not

feel slighted and be assured that I thought of you every day as I struggled with this document and

gained inspiration from your devotion and continued efforts.

To those the world over who did answer my call for help at various points, I offer you my

heartfelt thanks. And double thanks to those many who answered my emails within a day or

two, demonstrating their still active concern and interest. As I will point out in the text, the

Madagascar environment program beneted from an extraordinary depth of commitment and

collaboration. Many who worked on the program over the years helped in the preparation and

review of this document, which would not have been possible as a solitary venture. I hope I will

not miss any of you, as I cite the long list of helpful contributors: Andy Keck, Ashley Marcus, Asif

Shaikh, Carlos Gallegos, Christian Burren, Christian Kull, Daniela Raik, Doreen Robinson, Derick

Brinkerhoff, Erika Styger, Frank Hawkins, George Carner, John Pielemeier, Jean Michel Duls, Jean Solo

Ratsisompatrarivo, Jennifer Talbot, Julia Jones, Heather D’Agnes, Kristin Patterson, Leon Rajaobelina,

Lisa Steele, Lynne Gafkin, Marie de Longcamp, Michael Brown, Nanie Ratsifandrihamanana, Nirinjaka

Ramasinjatovo, Martin Nicoll, Matt Sommerville, Michael Brown, Oliver Pierson, Paul Ferraro, Paul

Porteous, Philip DeCosse, Richard Carroll, Richard Marcus, Steve Dennison,Tiana Razamahatratra,

Todd Johnson,Tim Resch,Tom Erdmann, and Tony Pryor.

In addition, a workshop in Washington early in the writing process allowed numerous people to

provide guidance. In addition to many of those named above, the following people participated in

that workshop and I thank them for their time and valuable input: Richard Carroll, David Isaak, Jaime

Cavelier, Steve Watkins, Matthew Edwardsen, Jason Ko,Terri Lukas, Natalie Bailey, Luke Kozumbo,

Doug Clark, and David Hess.

Among those I must single out for particular thanks is Lisa Gaylord who was extraordinarily

generous in answering all of my questions, at all hours of day and night, and yet let the story (which

is in many ways her story) unfold without interference or attempts to inuence its direction. Few

who worked on Madagascar’s environment program did not at one time or another spend an

evening (or many) at Lisa’s house, struggling with issues from the mundane to the monumental.This

paper might be considered the culmination of those discussions, or perhaps a palate refresher before

the next round.

I am also grateful to Mark and Annika Freudenberger who tolerated endless dinner time musings as

they helped me get the ideas sorted out.

Thank you all for caring enough to help me make this document as good and as accurate as I could.

Having said that, it will never be good enough or accurate enough.The job was immense, the story

complex, and the time and pages available far too limited to do it justice. At a certain point, I have to

decide that we’d said enough, have to count on the wisdom of readers to delve deeper and further,

and have to hope that continuing discussions will set the record straight.The errors of fact and

judgment that remain in spite of our collective best efforts are, regrettably, my own and I apologize

for them.

IX

CI

LIST OF ACRONYMS

AGEX Agences d’Exécution

(Implementing agencies, including ONE, ANGAP, etc.)

AGERAS Appui à la Gestion Régionalisée de l’Environnement et à

l’Approche Spatiale (Support to Landscape Ecology Approach)

ANAE Association Nationale d’Action Environnementale

(National Association for Environmental Action)

ANGAP Association Nationale pour le Gestion des Aires Protégées

(National Association for the Management of Protected Areas)

ANGEF Association Nationale pour la Gestion des Forêts

(National Association for the Management of Forests)

APN Agents for the Protection of Nature

ARD Associates in Rural Development

ARSIE Association du Réseau Système d’Information Environnemental

(Environmental Information system Network Association)

BAMEX Business and Market Expansion (USAID project)

CAP Commercial Agriculture Project

CBNRM Community-based Natural Resource Management

CC PTE Cercle de Concertation – Partenaires Techniques

et Financiers – Environnement

CELCO Coordination Unit (under the Ministry of Environment/DEF)

Conservation International

CIM Comité Interministériel pour l’Environnement

(Interministerial Committee for the Environment)

CLB Communauté Locale de Base

COAP Code des Aires Protégés (Protected Area Management Legislative Code)

COBA Communauté de Base (Grass-roots Community)

COMODE Conseil Malgache des Organisations Non-Gouvernementales

pour le Développement (Malagasy Council of NGOs)

CMP Comité Multi-local de Planication (Local Planning Committee)

XI

CRD Comité Régional de Développement (Regional

Development Committee)

CRS Catholic Relief Services

CSLCC President’s Council to Fight Corruption

DAI Development Alternatives, Inc.

DEAP Droits d’Entrée dans les Aires Protégés (Protected Area entrance fee)

DEF Direction des Eaux et Forêts (Malagasy Water and Forestry Service)

DfN Debt for Nature

DG Democracy and Governance

DSRP Document Stratégique sur la Réduction de Pauvreté

(Strategic Document for Poverty Reduction)

EG Economic Growth

EIA Environmental Impact Assessment

ENV/RD Environment and Rural Development

EP Environment Program

EPA Administrative Public Entity

EPIQ Environmental Policy and Institutional Strengthening

Indenite Quantity Contract

ERI Eco-regional Initiatives (USAID project)

ETOA Environmental Threats and Opportunities Assessment

ETP Ecology Training Program

EU European Union

FAPBM Fund for Protected Areas and Biodiversity in Madagascar

FAO Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations

FCE Fianarantsoa Côte Est Railway

FCER FCE Railway Rehabilitation Project (USAID project)

FER Fonds d’Entretien Routière (Road Maintenance Fund)

FFN Fonds Forestier National (National Forestry Fund)

GBF Groupe de Bailleurs de Fonds (Donors Group)

XII

GCF Gestion Contractualisée Forestière (Forest Management Contract)

GDA Global Development Alliance

GEF Global Environment Facility

GELOSE Gestion Local Sécurisée (Secured Local Management)

GIS Geographic Information System

GNP Gross National Product

GoM Government of Madagascar

GPS Global Positioning System

GRAP Plan de Gestion du Réseau des Aires Protégées

(Management Plan for Protected Areas)

GTZ Gesellschaft fur Technische Zusammenarbeit (German

Government corporation for international development

ha hectares

HAT Haute autorité de la transition (High Transitional Authority)

ICDP Integrated Conservation and Development Project

IFAD International Fund for Agricultural Development

IFC International Finance Corporation

IMF International Monetary Fund

INSTAT Institut National de la Statistique (National Institute of Statistics)

IRG International Resources Group

IUCN International Union for the Conservation of Nature

JSI Jereo Isika Salama (USAID health project)

JSI John Snow International (project implementer)

LARO Linking Actor for Regional Development Opportunity

(component of SAVEM project)

KEPEM Knowledge and Effective Policies for Environmental Management

LDI Landscape Development Interventions

MITA Managing Innovative Transitions in Agreement (USAID project)

MAP Madagascar Action Plan

XIII

MCA Millennium Challenge Account

MCC Millennium Challenge Corporation

MECIE Mise en Compatibilité des Investissements avec l’Environnement

MIARO Biodiversity Conservation Project (USAID project)

MISONGA Managing Information and Strengthening Organizations for

Network Governance Approach (USAID Project)

MinEnv Ministère de l’Environnement (Ministry of Environment)

MRPA Managed Resource Protected Areas

NEAP National Environmental Action Plan

NGO Non-governmental Organization

NHWP Nature, Health,Wealth, and Power

NRM Natural Resource Management

NWP Nature,Wealth, and Power

ONE Ofce Nationale de l’Environnement (National Environment Ofce)

PA Protected Area

PASA Participating Agencies Service Agreement

PACT Private Agencies Collaborating Together

PAGE Projet d’Appui à la Gestion de l’Environnement (USAID Project)

PFNSCM Plate-forme Nationale de la Société Civile Malgache

(National Platform for Malagasy Civil Society)

PTE Programme de Transition Eco-régional (USAID Project)

PVO-NGO NRMS Private Voluntary Organization-Non-governmental

Organization Natural Resource Management

PVO Private Voluntary Organization

QMM QIT-Fer Minerals Madagascar

REBIOMA Réseau de biodiversité de Madagascar

REDD Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation

SAGE Service d’Appui à la Gestion Environnementale

SAPM Système des Aires Protégées (System of Protected Areas)

XIV

SAVEM Sustainable Approaches for Viable Environmental

Management (USAID Project)

SO Strategic Objective

SRI System of Rice Intensication

SUNY State University of New York

TR&D Tropic Research and Development

UNDP United Nations Development Program

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

USAID U.S. Agency for International Development

USFS U.S. Forest Service

VCS Voluntary Carbon Standard

WB World Bank

WCS Wildlife Conservation Society

WWF World Wildlife Fund / World Wide Fund for Nature

ZIE Zone d’Intérêt Eco-touristique (Eco-tourism Development Zone)

XV

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) opened its Madagascar Mission in 1984 and

rapidly became one of the principal actors in developing and implementing the three Environmental

Programs (EPs) that operationalized the 1990 National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP).This

retrospective is written 25 years later (with the Environmental Program suspended due to the 2009

coup d’état) to take stock of where we have come in efforts to save Madagascar’s threatened natural

resources and to set the stage for discussions regarding future program directions.The paper focuses

specically on USAID’s environmental programs, while recognizing that USAID interventions took

place in a context that involved many different partners.

When USAID opened its doors in Madagascar, the country was coming out of a decade of serious

economic stagnation and environmental decline (some 400,000 hectares (ha) of forest were lost

each year).The NEAP sought to protect Madagascar’s biodiversity heritage (which meant, in practice,

saving the forests on which the biodiversity depended) and to improve the living conditions of the

population.

Slash-and-burn agriculture by very poor farmers is one of the primary threats to Madagascar’s

forests. As such, it was recognized early on that there was little hope of protecting forests without

also addressing (1) fundamental economic issues that maintain rural people in abject poverty and

(2) rapid population growth (close to 3% a year) that has caused Madagascar’s population to more

than double in the roughly 25 years covered by this paper. Consequently, USAID’s program has

consistently promoted synergies between the health and environment sectors. (The Madagascar

population-environment program is a worldwide model for this approach.)

USAID’s programs have, in principle, mirrored the NEAP emphasis on linking environmental

conservation and improved livelihoods. In the rst decade (1984 to 1994), USAID had robust

funding and strong economic and agricultural programs that complemented work on the

environment and social services. In 1994, after Madagascar failed to meet its structural adjustment

commitments, the Mission was demoted and suffered major funding cuts to nearly all programs

except health and population.

Environmental programs in Madagascar were spared only because of the Congressional biodiversity

earmark.The earmark has been instrumental in assuring continued funding for the environment but

has at the same time reinforced a relatively narrow biodiversity focus. In the absence of other funds,

the Madagascar program has faced consistent difculties in addressing complementary issues such as

agriculture and economic growth.While transformation of Madagascar’s economy might well have

been impossible even with more robust agricultural and economic development funding, there can

be no doubt that success on the environment front has been constrained by broader economic

development failure, particularly in Madagascar’s rural areas.

USAID’s environment programs in Madagascar roughly followed the three phases of the national

Environment Programs. EP I (1991-1996) funding totaled some $49 million. Programs focused on

(1) making the newly establish Protected Areas (PAs) work and (2) establishing the foundations for

environmental management through institutional strengthening and human resource development.

The key national environment sector institutions (The National Environment Ofce, or ONE,

and National Association for the Management of Protected Areas, or ANGAP) were established

and closely mentored during this phase.The largest project was an Integrated Conservation

and Development Project (ICDP) that funded social and economic development activities in

communities adjacent to seven national parks.

1

Evaluations highlighting the limitations of the ICDP approach (both in Madagascar and elsewhere in

the world) led to a paradigm shift in thinking toward the eco-regional approach that characterized

project interventions in EP II (1997-2002) and EP III (2003-2008).These projects focused on

identifying systemic threats to natural resources over larger landscapes (specically focusing

on alternatives to slash-and-burn agriculture), while policy interventions continued to address

institutional weaknesses and the legal framework needed to implement sustainable resource

management.Throughout the program’s history, there have been efforts to increase civil society

capacity and improve governance.

This paper reviews progress and challenges in four domains: Policy and Institutions, Protected Areas,

Reducing Pressures on Resources by Surrounding Communities, and Economic Valorization of

Natural Resources.

On the Policy and Institutions front, there has been major progress in promulgating legislation

needed to improve management of natural resources, and developing the tools needed to

operationalize improved management. Legal frameworks for forest management, environmental

impact assessment, and co-management of forest resources are among the notable advances in the

policy domain. Similarly, semi-autonomous institutions to manage the national parks and coordinate

environmental activities were established and trained. Much effort has gone into assuring sustainable

nancing for the national park system and local environment interventions through the creation of

two endowed foundations.The endowments are not yet fully funded, but they are well on the way.

While the legal framework and the toolkit to implement the environmental laws are now relatively

complete, the effective use of these tools continues to be hampered by notoriously weak and

corrupt government structures.

Protected Areas. Madagascar has had an ambitious national park system since colonial times but

at the start of EP I, there were only two publicly accessible parks. Lack of capacity at the Water and

Forestry Service (DEF) had created a de facto open access situation and many protected areas were

being deforested at an alarming rate.The creation of ANGAP (later renamed Madagascar National

Parks) and partnerships with international operators reestablished an effective park system. By EP II,

day-to-day park management responsibilities had largely been transferred to Madagascar National

Parks.

In 2003, President Marc Ravalomanana announced at the International Union for Conservation

of Nature (IUCN) conference in Durban that 6 million hectares would be put under protected

area status.This dramatic move – known as the Durban Vision – spearheaded by the international

conservation organizations, increased the area under protection from 3% to 10% of the country’s

land.While this program is still being implemented, there is widespread concern that the speed of

implementation and belated attention to concerns of local communities has created a backlash of

resentments that will be difcult to overcome.

Initial experiences with co-management (local communities and the State) of natural forests were

already underway, but the Durban Vision announcement accelerated the transfer of management

responsibilities from the State (which lacks capacity to carry out the task) to local communities.

Somewhat less than half the 6 million ha under protected area status will be under the authority of

Madagascar National Parks, while the rest will be under some sort of co-management agreement

with either local communities or the private sector.While State management of these huge

protected areas is clearly not feasible under current Malagasy conditions, co-management has also

proved to be problematic, especially when economic benets turn out to be less than what the

community expects or are perceived to be insufcient compensation for foregoing traditional slash-

and-burn agriculture.

2

Reducing Pressures on Resources by Surrounding Communities. While logging and

harvesting for fuelwood continue to motivate serious deforestation in some areas of the country,

slash-and-burn agriculture remains the biggest source of forest transformation nationwide. USAID

programs have invested signicant efforts to reduce these pressures in selected biodiversity

conservation areas. A range of alternative agricultural practices have been proposed and, while

there has been signicant variation in adoption rates, deforestation rates in the areas where project

activities have been most intense have declined. Nevertheless, these projects recognize that farm

level interventions are insufcient to effectuate changes in production practices at the scale needed

to save Madagascar’s forests.Without improved infrastructures (transport and irrigation) and national

economic policies that promote rural development, there is little chance of persuading farmers to

abandon unsustainable subsistence agriculture practices.

Several USAID initiatives have focused on valorizing natural resources. Some efforts have

been devoted to improving eco-tourism ventures and markets for natural products. While both

show potential, the magnitude of benets will ultimately depend on larger economic factors and the

State’s ability to control negative impacts. USAID projects have also worked with the government to

designate signicant forest areas as sustainable production zones, usually under private (sometimes

community) management. It is estimated that at least 2 million ha are needed to assure domestic

requirements for fuel and building wood (to date, about a third of this area has been so designated

by the Ministry of Environment).While there have been major advances in preparing the technical

and administrative approaches to implementing sustainable production zones, actual contracting has

been slow and only a tiny proportion of the sites have actually been tendered. It is thus too early to

assess the success of this approach.

This retrospective concludes that in spite of numerous project successes, Madagascar’s environment

is in signicantly worse shape now than it was 25 years ago. In 1990, Madagascar had about 11

million ha of forest and 11 million people.Today the country has about 9 million ha of forest and 20

million people. Forest clearing has slowed (from about 0.83% annually between 1990-2000 to 0.53%

annually since 2000) but more than a million hectares of forest were lost in the 15 years between

1990 and 2005. Furthermore, the remaining forests have become increasingly vulnerable: 80% of

Madagascar’s forests are now located within 1 km of a non-forest edge.

The reasons for this are humbling in their magnitude and complexity. (Anyone who tells you that

they have an easy answer to Madagascar’s environmental problems should be immediately suspect,

a caution necessary because Madagascar seems to be a magnet for people who think they have

the “magic bullet.”) Not-good-enough governance is without doubt a factor that underlies all

others. Systemic corruption, crises that have become a normal part of the political landscape, and

short-term resource management strategies that benet transient leaders but not the population at

large are pernicious characteristics that persist through changes of government.These governance

issues have insidious effects that make it difcult, if not impossible, to create the economic conditions

necessary to scale up promising environmental interventions (e.g. sustainable improvements in

infrastructure, implementation of rice pricing, and other policies favorable to the rural economy).

In the end, environmental preservation is hostage to economic development and economic

development is hostage to good governance.

We are now at a point where time is running out for the prized biodiversity Madagascar holds in its

charge.This report’s nal section lays out three broad options – scenarios – for future interventions.

It is purposefully provocative in an attempt to open up the debate and lay out issues that may

otherwise be neglected in a more conventional “stay-the-course” strategy.

3

Scenario 1: Forget it; it’s already too late and nothing we can realistically do will

save Madagascar’s remaining forest resources. This scenario proposes that USAID invest its

scarce resources somewhere else where the context is more favorable to a positive and sustainable

outcome.

Scenario 2: Keep on track – Do more of the same, but do it better. This scenario

proposes reprioritizing USAID intervention areas to identify those where we anticipate having the

greatest impact, adding signicantly more resources with assurances that funding will continue for at

least another 20 years, and developing a program around the best practices that have been identied

up until now (but with more sustained attention to economic growth and the promotion of civil

society institutions).

Scenario 3: Madagascar’s biodiversity ends justify the means – Break all the rules and

go for it. This scenario essentially recognizes that the international community values Madagascar’s

biodiversity far more highly than do its government and its people.We must therefore be prepared

to pay for its protection.This approach would require a massive commitment of international aid into

the distant future. Funds would be used for direct payments to communities that forego activities

harmful to the environment and to fund infrastructure, education, and other structural factors as

needed to help the economy transform and develop.The demands of this approach would far

surpass USAID’s capacity, but the agency might play a useful role in conceptualizing the approach and,

perhaps, implementing a discrete set of activities as needed to maintain its presence at the table.

4

INTRODUCTION

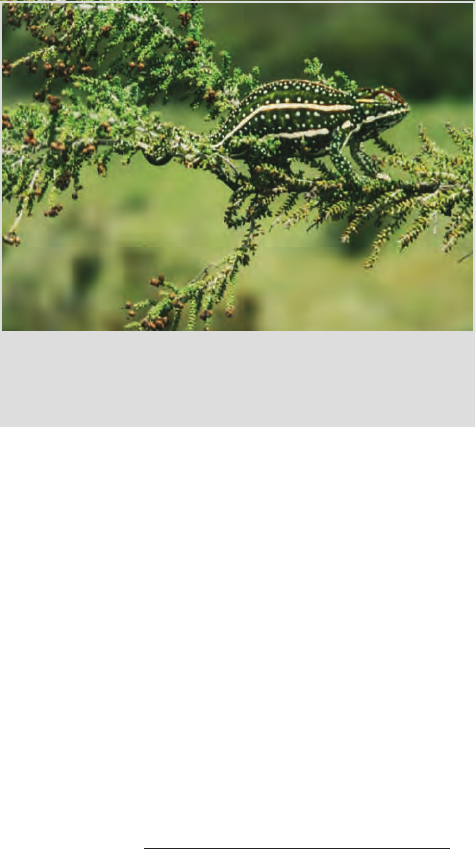

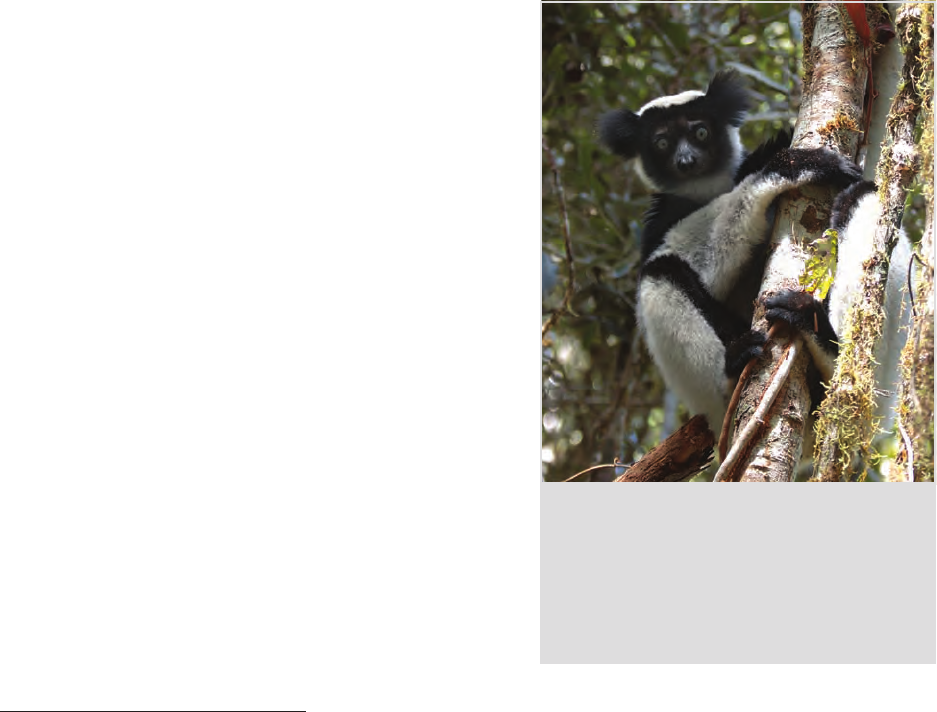

Madagascar’s biodiversity is unique: 98% of its mammals, 91% of

its reptiles, and 80% of its owering plants are found nowhere

else on earth. (Photo credit: Karen Freudenberger)

A hectare of forest lost in Madagascar has a greater negative impact on global biodiversity than a

hectare of forest lost virtually anywhere else on earth (U.S. Forest Service).

1

Concerted efforts

2

to save Madagascar’s natural forests

3

began in the mid 1980s when Madagascar

and its partners began preparing the rst Madagascar National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP).

The U.S. Agency for International Development

(USAID) opened its Madagascar Mission in 1984 and

rapidly became one of the principal actors in

developing and implementing the three successive

Environmental Programs (EPs).Twenty-ve years later,

this paper takes a step back to look at challenges

encountered, actions implemented, lessons learned, and

progress made towards conservation and development

goals.This retrospective is being written in the midst of

the third political crisis since the USAID Mission

opened (the fourth since Madagascar gained

independence).With USAID’s Environmental Program

currently suspended, we rst review the road(s) taken

to get us to where we are today before looking at

potential paths into the future.

Work toward the objectives of the NEAP has involved

uncountable numbers of actors, both Malagasy and

international.This retrospective focuses explicitly on

USAID-funded interventions with the idea of recording

the evolution of this grand and visionary experiment

and learning some of its key lessons.The focus on USAID’s effort does not mean to belittle the

interventions of other participants; indeed the commendably collaborative nature of the venture

makes it impossible in most case to attribute either results or blame to particular actors. Progress,

elusive as it is, must be celebrated regardless of its source and we must forthrightly acknowledge our

collective disappointments in order to learn their lessons.

Even for those of us who were present at or near the inception of this effort, it is stunning to recall

how much we didn’t know and how much had not yet happened a mere 25 years ago. Madagascar

had only two, barely accessible, national parks open to the public and 12,000 international visitors

1 http://www.fs.fed.us/global/globe/africa/madagascar.htm.

2 Madagascar’s environment had been of interest for centuries, as described by Andriamialisoa and

Landgrand (Andriamialisoa and Langrand 2003), who offer a fascinating history of Madagascar’s scientic

exploration going back to the 1600s.

3 While Madagascar’s environment obviously comprises vastly more than forests, the period covered by this

paper was primarily focused on forests and the biodiversity that depends on the maintenance of those

forests. Consequently, this topic receives the major emphasis here.

5

a year.We had little more than the vaguest (poorly documented) hypotheses about Madagascar’s

natural resource wealth and why it was disappearing.

4

The extent to which these and other things

have changed will be addressed in the body of this paper.

For the moment, however, we should acknowledge the veritable volcanic eruption of research,

analyses, planning documents, evaluations, and project reports that occurred in the years since

the NEAP was launched – tens of thousands of pages have been written about Madagascar’s

environment and efforts to save it (Goodman and Benstead’s magnicent 2004 tome The Natural

History of Madagascar alone runs to more than 1,700 pages).This wealth of accreted information

is cause for celebration.We have tried to keep this report reasonably short to render it accessible

to a wide gamut of readers. It cannot, in its brevity, possibly capture the richness of Madagascar’s

environmental story or even USAID’s part in it. Readers who wish to delve further are invited to

consult the “key references” for each section of the paper that go into greater depth on various

topics.Those seeking more information should note that key reference documents were chosen in

part because they have extensive bibliographies. Most of the publicly available key documents are

included on the CD that accompanies this paper.

Iharana

Sambava

Antalaha

Morombe

Toliara

Madagascar

Mahanoro

Betroka

Betioky

Bekily

Antsohihy

Antanimora

Ankazobe

Andapa

Analalava

Ambilobe

Ambalavao

Vatomandry

Morafenobe

Midongy Atsimo

Marovoay

Mandritsara

Maintirano

Madirovalo

Fenoarivo Atsinanana

Ambovombe

Ambodifototra

Ambatofinandrahana

Ambato Boeny

Antsiranana

Morondava

Ambatolampy

Ambanja

Tolanaro

Moramanga

Maroantsetra

Mananjary

Manakara

Hell-Ville

Farafangana

Arivonimamo

Antsirabe

Ambositra

Ambatondrazaka

Fianarantsoa

Toamasina

Mahajanga

Antananarivo

4 The 1988 Proposed Environmental Action Plan wrote:“Madagascar’s data base is not current and reliable

enough to allow for planning and action. Environment in particular has no indicator of the status of natural

resources and their evolution over time.This is particularly regrettable since, in the 1960s, Madagascar was

considered a model country for collection and management of basic data in the African context.There has

since been a progressive deterioration in the data system.” (World Bank; et al. 1988, 41).

6

A BRIEF HISTORY

OF NEAP, THE

ENVIRONMENT

PROGRAMS, AND USAID

INTERVENTIONS

5

In the 1980s, recognizing the critical role of both environment and economic policies in the

sustainable development of poor nations, the World Bank (WB) began to encourage African

countries to adopt more comprehensive environmental strategies. Madagascar was coming out

of a decade of serious economic and environmental decline (roughly 400,000 ha of forests were

lost every year in the decade between 1975 and 1985).The WB estimated that the economic

costs of environmental degradation (forest and soil loss, the need to rebuild infrastructures due to

erosion, diminished agricultural productivity etc.) cost the country between 5 and 15% of GNP

6

annually (WB, et al. 1988, 9). Donors at the time were also concerned that duplication of efforts and

confusion over who was doing what in the environmental eld was facilitating corruption.The NEAP

would create a framework and a mechanism for clarifying donor roles.To reinforce this message,

World Bank loans were made contingent on the promulgation of an environment plan to dene its

conservation and development priorities.

7

The Smithsonian Institution played a key and perhaps little known role in developing Madagascar’s

NEAP. As early as 1988, the Smithsonian signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the

Madagascar Ministry of Scientic Research and Technological Development to facilitate research

permits and scientic exchanges.The Smithsonian then hosted a number of the working groups

that brought together scientists, representatives of the conservation organizations, and ofcials

from the World Bank, USAID, and other policy makers to lay out the issues that would become the

framework for the NEAP (Corson 2008).

THE NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL ACTION PLAN

In 1990, after several years of preparation, Madagascar’s legislature voted for the Environmental

Charter as a foundation for the rst NEAP in Africa.The plan represented a dramatic shift away from

viewing the State’s role in environmental management primarily in terms of exclusion and policing,

5 A key document for this section is USAID/Biodiversity Analysis and Technical Support 2008.

6 This cost was assessed at $100 million to $290 million/year: 75% attributed to forest destruction, 15% due

to decreased agricultural productivity, and 10% due to increased costs for maintenance of infrastructures

(NEAP 1988, 28). Bruce Larson (Larson 1994) believes that this gure was overstated, particularly in

regards to the opportunity costs associated with agricultural land use and the conversion of forests to

agriculture.

7 The World Bank promised Madagascar about $120 million of funding for EP I on the condition that

legal and institutional changes were made, including formalizing the NEAP. The passage of the 1990

Environmental Charter fullled this requirement (Gezon 1997) (USAID/Biodiversity Analysis and Technical

Support 2008).

7

as it had been since colonial times. Instead, from the outset it joined the dual goals of protecting the

environment and improving living conditions, a principle that has been woven into every intervention

funded by USAID since.

The six objectives as dened in Madagascar’s NEAP were to:

i. Protect and manage the national heritage of biodiversity, with a special

emphasis on parks, reserves, and gazetted natural forests, in conjunction

with the sustainable development of their surrounding areas

ii. Improve the living conditions of the population through the protection

and management of natural resources in rural areas with an emphasis

on watershed protection, reforestation, and agro-forestry

iii. Promote environmental education, training, and communication

iv. Develop mapping and remote sensing tools to meet the

demand for natural resources and land management

v. Develop environmental research capacities for terrestrial, coastal, and marine ecosystems

vi. Establish mechanisms for managing and monitoring the environment.

The NEAP itself was seen as one-third of a “tripod” needed for

Madagascar to escape the vicious cycle of deepening poverty

and accelerating environmental degradation. Along with the

NEAP to address environment concerns, the other two “legs”

were (1) structural adjustment to reform basic economic

policies and (2) poverty reduction programs (including

population policies).

The Environmental Programs

To get from the general principles of the NEAP to operational

programs, in 1988 the World Bank formed a series of working

groups that mobilized about 150 Malagasy from government,

academia, and civil society alongside about 40 international

environment experts (many of whom are still involved today).

The working group proposals were then approved by the

National Assembly.The grand plan for implementing the NEAP

was divided into three successive Environmental Programs:

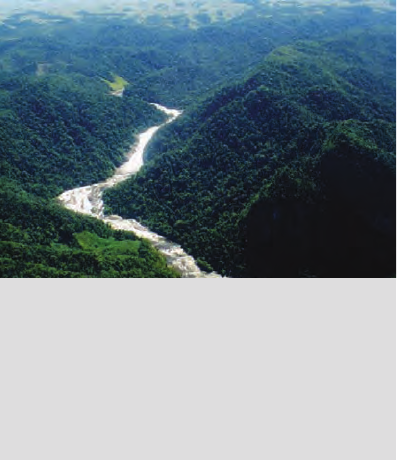

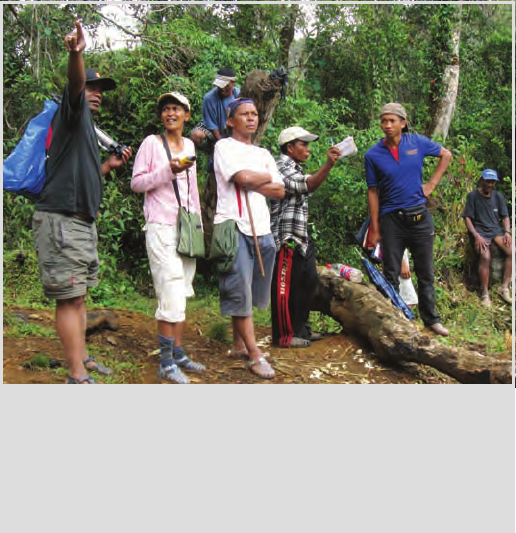

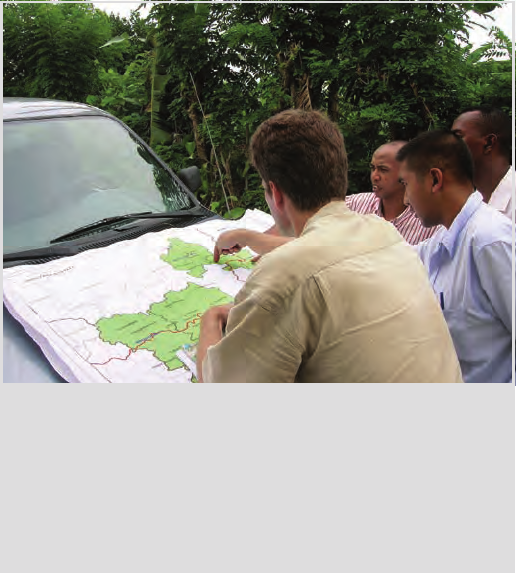

From EP I to EP II, the emphasis shifted from the

integrated conservation and development (ICDP)

approach to protecting much vaster corridors

linking national parks. (Here: the corridor between

Ranomafana and Andringitra parks.) (Photo credit:

Mark Freudenberger)

8

Table I: Madagascar’s NEAP Implementation

8

NEAP Phase Main purpose, objectives, orientation

EP I

NEAP start-up phase

• Set up institutional frameworks

• Set up program nancing

• Establish program procedures, norms, and performance criteria

• Establish environmental monitoring mechanisms

• Establish coordination mechanisms

• Conduct pilot operations and action research with a view to EP II

EP II

Action oriented phase – intensication of actions initiated in EP I

• Carry out concrete actions in biodiversity conservation,

soil conservation, cartography, and land registration

• Integrate the NEAP into the national development plan

• Reinforce program coordination

EP III

Mainstreaming Phase – environmental “reex” to become automatic

• Complete integration of NEAP into the national development plan

• Populations, collectives, ministries, and non-governmental

organization (NGOs) should be actively implementing

techniques of environmental management

• State structures should be systematically applying the

environmental concept in sector policies and programs

• National plans and programs make environment and

conservation a driver for sustainable development

The total funding (from all donors during EP I, II, and III) has been estimated at approximately $450

million for environment activities with another 50% for related programs that were not formally part

of the NEAP process but in some way contributed to it (e.g., agriculture and health interventions).

The United States contributed about $120 million to Madagascar’s environment program over this

period.

USAID/Biodiversity Analysis and Technical Support 2008, 76.

9

8

USAID INTERVENTIONS

9

Mission history

USAID’s Madagascar Mission opened in 1984

10

(though limited funding, particularly for food security

interventions, had begun as early as 1962).This occurred as Madagascar was coming out of a period

(the Second Republic, starting in 1975) when the Ratsiraka regime had advocated extreme socialism

and made foreign assistance from the west unwelcome. Facing acute debt and budgetary crises, the

Government of Madagascar (GoM) had signed its rst agreement with the International Monetary

Fund (IMF) in 1980, thereby opening the door to donor assistance.

Predating the NEAP, USAID’s rst environmental intervention (1986) was in support of an applied

research study on the country’s unique ora and fauna. Another early project looked at forest

management above irrigated rice perimeters (PL 480 funding), foreshadowing the linkage between

natural resources and food security.This was followed by a grant to World Wildlife Fund / World

Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) to carry out early integrated conservation and development work

in the Beza Mahafaly Reserve (1987) and then other operational program grants that anticipated the

integrated conservation and development (ICDP) approach, focusing on Amber Mountain, Masoala,

Ranomafana, and Andohahela.These initial grants helped prepare the Agency to play a larger role

when the NEAP was announced and donor support was solicited.The new Mission was also able

to draw on the experience of American research and conservation institutions that were already

active in Madagascar and who helped to dene the most critical issues and priority areas. By 1990,

USAID was ready to commit to a long-term environmental program, already anticipating three

implementation phases over a 15-year period.

Downsizing of the Mission and the biodiversity earmark. When EP I was launched in

1991, USAID-Madagascar was a major (Category A) Mission with more than a dozen direct hire

employees and signicant programs in agriculture/economic growth, environment, health, and

governance. At this time, the other lead institution supporting the NEAP was the World Bank, but

the Bank’s key staff people (both the Resident Representative and the EP I manager) were based in

Washington. By default, USAID became the lead actor for the Environmental Program.

The “power mission” was short-lived, however. In tacit recognition that program success was unlikely

if the basic structure of the economy was out of whack (social and economic indicators had also

plummeted during the socialist era), USAID made its continuing support contingent on Madagascar’s

adherence to a structural adjustment program.When Madagascar failed to meet the requirements,

a decision was made in 1994 to reduce U.S. assistance.The Mission was demoted to Category B

(with further “demotions” in later years) and suffered major funding cuts.The Environment Program

9 Catherine Corson’s dissertation, Mapping the Development Machine: the US Agency for International

Development’s Biodiversity Conservation Agenda in Madagascar, is a key document for this section.

10 Critical events in the recent environmental history prior to USAID’s arrival include Madagascar’s hosting

(1970) of the Second International Conference on the Rational Utilization and the Conservation of Nature

in Madagascar, the dramatic loss of forests during the 1970s when the Ratsiraka government encouraged

citizens to “take back” the natural resources previously protected by colonial laws, the 1984 passage of

Madagascar’s National Conservation Strategy (which followed IUCN guidelines), and the 1985 Second

International Conference on Conservation and Development, held in Antananarivo.We must also not

forget that estimates suggest that as many as 4 million ha of forests were decimated between 1900 and

1940 under the colonial administration due to logging, the introduction of cash crops such as coffee (which,

in taking the best land, pushed farmers to clear new elds from the forests), and wood extraction as

needed to power steam engines and build infrastructure. (Jarosz 1993).

10

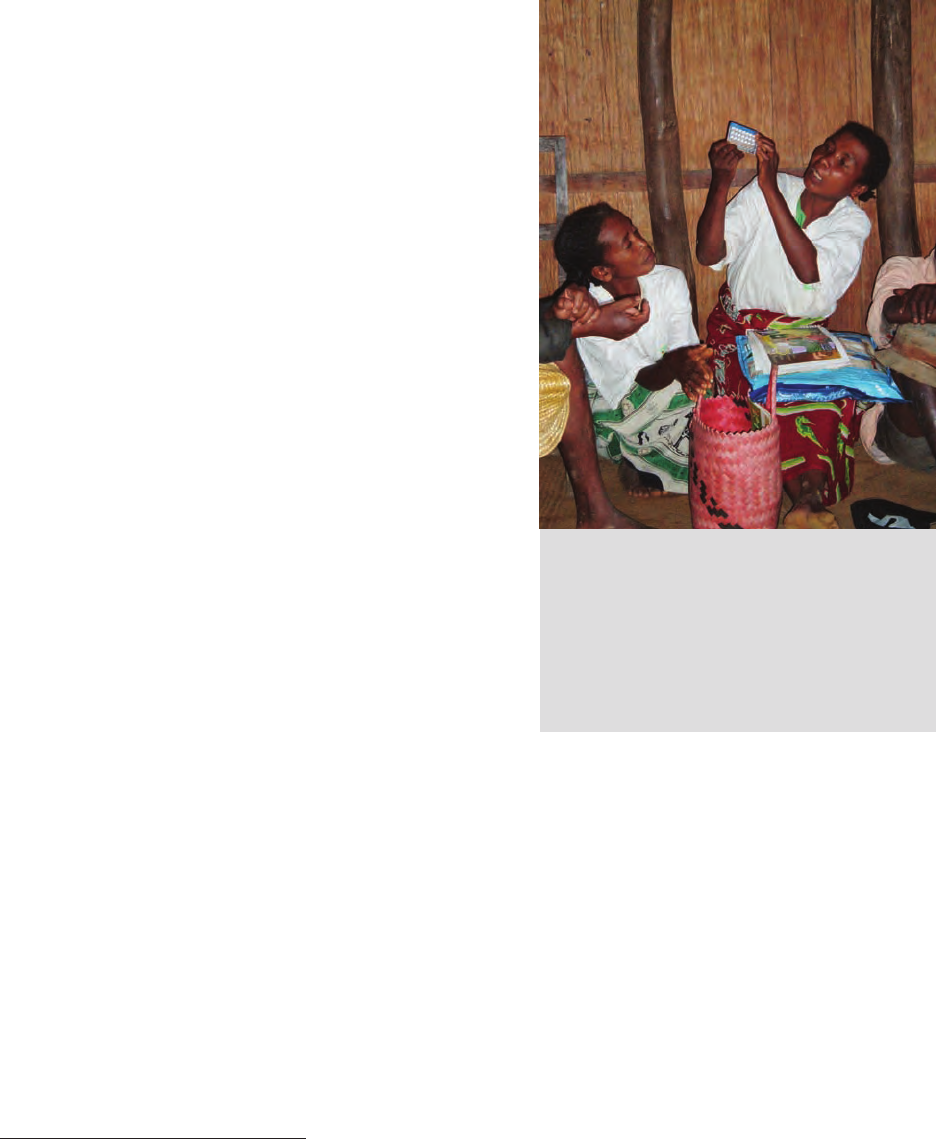

The progressive integration of population/health and

environment sector activities is one of the considerable

achievements of the Madagascar program.

Initially, there were independently planned and implemented health

activities and environment activities that both happened to be in

Madagascar. Under EP I, a deliberate decision was made to carry

out family planning interventions where USAID was nancing

ICDPs. From EP II on, family planning was not a stand alone service

program but was nested within broader health programs, and

integration of health and environment interventions took place

nationally and right down to the community level.

The integrated approach is now deeply woven into the fabric

of both environmental and health interventions in Madagascar.

Neither sector will say that the collaboration has been easy and

there are persistent references to “differences in culture” between

the two sectors, as well as a myriad of logistical and practical

considerations that arise when coordinating large and complex

projects operating on different time frames. All actors seem

to agree that the added efforts are justied, however, and are

convinced of the conceptual validity of the approach even when

the benets are difcult to quantify.

One important qualitative benet of integration has been the

reduction of gender bias in both domains: eld agents have

noticed that when environmental and health concerns are