ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK

RENEWABLE ENERGY

FINANCING SCHEMES

FOR INDONESIA

NOVEMBER 2019

ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK

RENEWABLE ENERGY

FINANCING SCHEMES

FOR INDONESIA

NOVEMBER

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO)

© 2019 Asian Development Bank

6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines

Tel +63 2 8632 4444; Fax +63 2 8636 2444

www.adb.org

Some rights reserved. Published in 2019.

ISBN 978-92-9261-832-2 (print), 978-92-9261-833-9 (electronic)

Publication Stock No. TCS190522

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS190522

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies

ofthe Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent.

ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any

consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they

are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.

By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country”

inthis document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area.

This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO)

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. By using the content of this publication, you agree to be bound

bytheterms of this license. For attribution, translations, adaptations, and permissions, please read the provisions

andterms of use at https://www.adb.org/terms-use#openaccess.

This CC license does not apply to non-ADB copyright materials in this publication. If the material is attributed

toanother source, please contact the copyright owner or publisher of that source for permission to reproduce it.

ADB cannot be held liable for any claims that arise as a result of your use of the material.

Please contact pubsmarketing@adb.org if you have questions or comments with respect to content, or if you wish

toobtain copyright permission for your intended use that does not fall within these terms, or for permission to use

theADB logo.

Corrigenda to ADB publications may be found at http://www.adb.org/publications/corrigenda.

Note:

In this publication, “$” refers to United States dollars.

Cover design by Francis Manio.

Contents

Tables, Figures, and Boxes vi

I. Introduction and Background

II. Current Situation

III. Challenges

IV. Definition of Design Parameters and Design Options

A. Viability Gap or Lack of Profitability

B. High Transaction Costs, Risks of Project Development, andLimited

CapacitybyDevelopers and Financial Institutions

C. High Perceived Risk by Banks and Other Financial Institutions

V. Evaluation and Recommendations on Financing Instruments for

IdentifiedFinancial Intervention Needs

A. Viability Gap Funding

. Option Viability Gap Funding : Fixed Tari

. Option Viability Gap Funding : Fixed Premium

. Option Viability Gap Funding : Competitive Auction of Power

Purchase Agreements

. Option Viability Gap Funding : Competitive Auction of Premium

. Option Viability Gap Funding : Investment Grant

. Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations

B. Project Development Funding

. Option Project Development Funding : Technical Assistance and

Capacity Building

. Option Project Development Funding : Project Development Grants

. Option Project Development Funding : Project Development

Risk Finance

. Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations

C. Credit Enhancement Fund

. Option Credit Enhancement Fund : Guarantee

. Option Credit Enhancement Fund : Onlending or Credit Line

. Option Credit Enhancement Fund : Colending, Syndication, A/B Loans

. Option Credit Enhancement Fund : Stand-Alone Debt Fund

. Option Credit Enhancement Fund : Interest Rate Subsidy

. Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations

Renewable Energy Financing Schemes for Indonesia

iv

VI. Brief Summary of Similar Schemes Applied in Other Countries

A. Introduction

B. Global Energy Transfer Feed-in Tari, Uganda

. Background

. Description of the Scheme

. Governance Structure and Funding Sources

. Relevance and Lessons for Indonesia

C. Private Finance Advisory Network, Global

. Background

. Description of the Scheme

. Governance Structure and Funding Sources

. Relevance and Lessons for Indonesia

D. Renewable Energy Performance Platform, Sub-Saharan Africa

. Background

. Description of the Scheme

. Governance Structure and Funding Sources

. Relevance and Lessons for Indonesia

E. Competitive Bidding of Long-Term Premium Tari, Finland

. Background

. Description of the Scheme

. Governance Structure and Funding Sources

. Relevance and Lessons for Indonesia

F. Accelerating Renewable Energy in Central America

. Background

. Description of the Scheme

. Governance Structure and Funding Sources

. Relevance and Lessons for Indonesia

G. Turkey Sustainable Energy Financing Facility, European Bank for

Reconstruction and Development

. Background

. Description of the Scheme

. Governance Structure and Funding Sources

. Relevance and Lessons for Indonesia

VII. Governance Structure of the Energy Resilience Fund

A. Introduction

B. Governance and Organizational Structure of the Energy Resilience Fund

VIII. Concept Design of the Viability Gap Fund

A. Description of the Instrument

B. Eligibility Criteria

C. Determination of the Premium Tari

D. Competitive Bidding Process, Ranking, and Contract Award

E. Timing and Volume Considerations

F. Sanctions and Incentives

v

Contents

IX. Concept Design of the Project Development Fund

A. Description of the Instrument

B. Eligibility Criteria

C. Main Terms and Conditions of the Project Development Fund

D. Selection Process

E. Timing and Volume Considerations

F. Technical Assistance Linked to the Project Development Fund

X. Concept Design of the Credit Enhancement Fund

A. Description of the Instrument

B. Eligibility Criteria

C. Main Terms and Conditions of the Credit Enhancement Fund

D. Selection Process

E. Timing and Volume Considerations

F. Technical Assistance Linked to the Credit Enhancement Fund

XI. Capitalization Structure and Potential Sources of Funding

A. Viability Gap Funding

. Type of Viability Gap Funding

. Sizing of Viability Gap Funding

. Sources of Viability Gap Funding

B. Project Development Funding

. Type of Project Development Funding

. Sizing of Project Development Funding

. Potential Sources of Project Development Funding

C. Credit Enhancement Funding

. Type of Credit Enhancement Funding

. Sizing of Credit Enhancement Funding

. Potential Sources of Credit Enhancement Funding

D. Summary

XII. Conclusions

A. General

B. Viability Gap Fund

C. Project Development Fund

D. Credit Enhancement Fund

E. Other Approaches

XIII. References

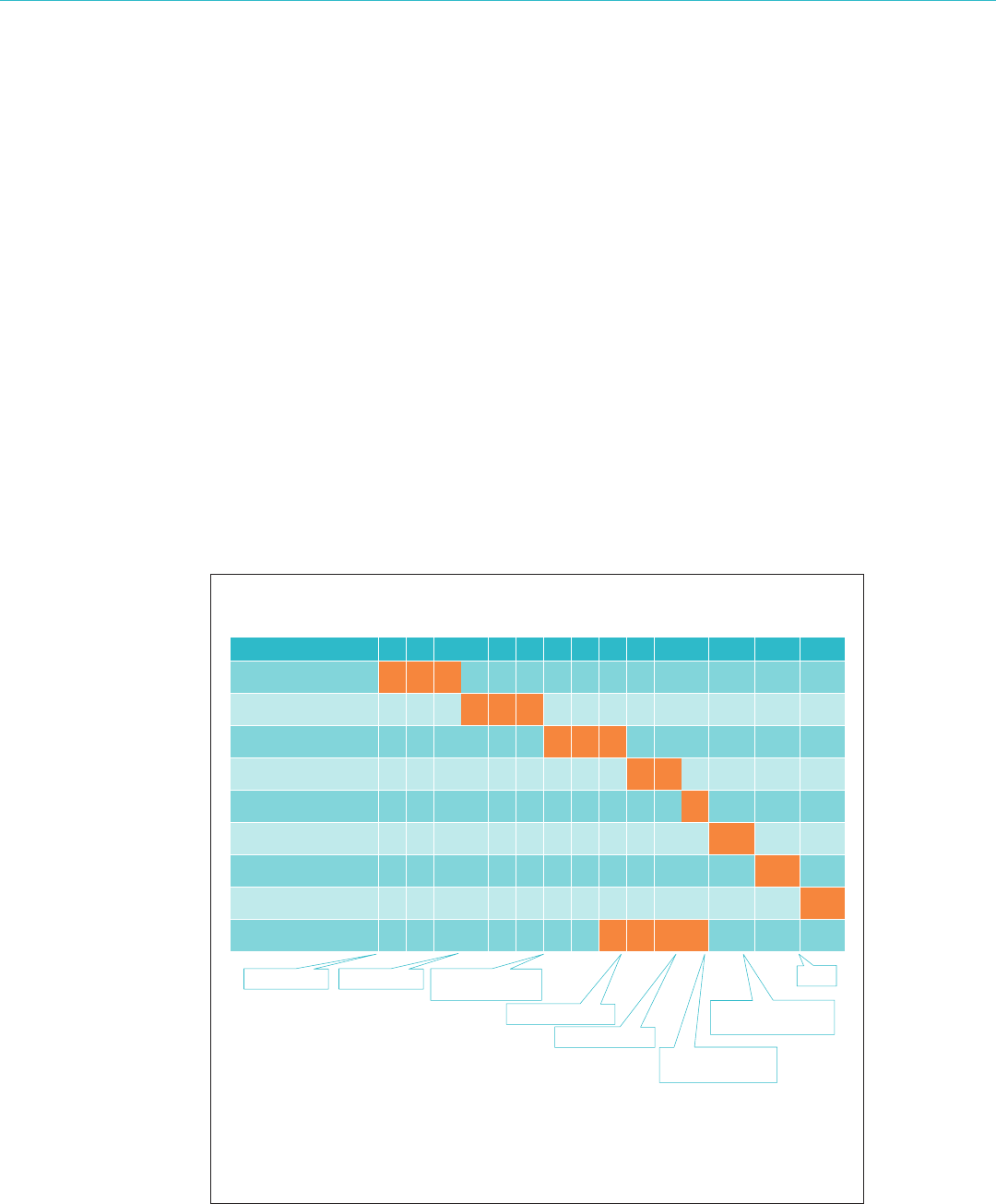

Tables, Figures, and Boxes

Tables

Summary of Similar Schemes in Other Countries Included in the Review

Illustrative Timeline for One Bidding Round

Illustration of Potential Viability Gap Fund Sizing at Dierent Assumptions on

Support per Megawatt-Hour and Targeted Cumulative Capacity

Basic Structuring and Capitalization of the Project Development Fund

Basic Structuring and Capitalization of the Credit Enhancement Fund

Summary of the Capitalization vis-a-vis Components of the

Energy Resilience Fund

Figures

Development of Power Demand and Installed Generation Capacity

Development of the Power Generation Mix in Indonesia in –

Investment Barriers and Relevant Stakeholders to Address Them

Proposed Three Types of Financial Interventions, and

Potential Solutions for Each

Governance Structure and Organization of the GET FiT Program

Main Level Governance and Organizational Structure of the

Energy Resilience Fund, Option

Main Level Governance and Organizational Structure of the

Energy Resilience Fund, Option

Main Level Governance and Organizational Structure of the

Energy Resilience Fund, Option

Illustrative Example of Bid Premium Tari Levels in a Bidding Process

Deal Process of the Project Development Fund

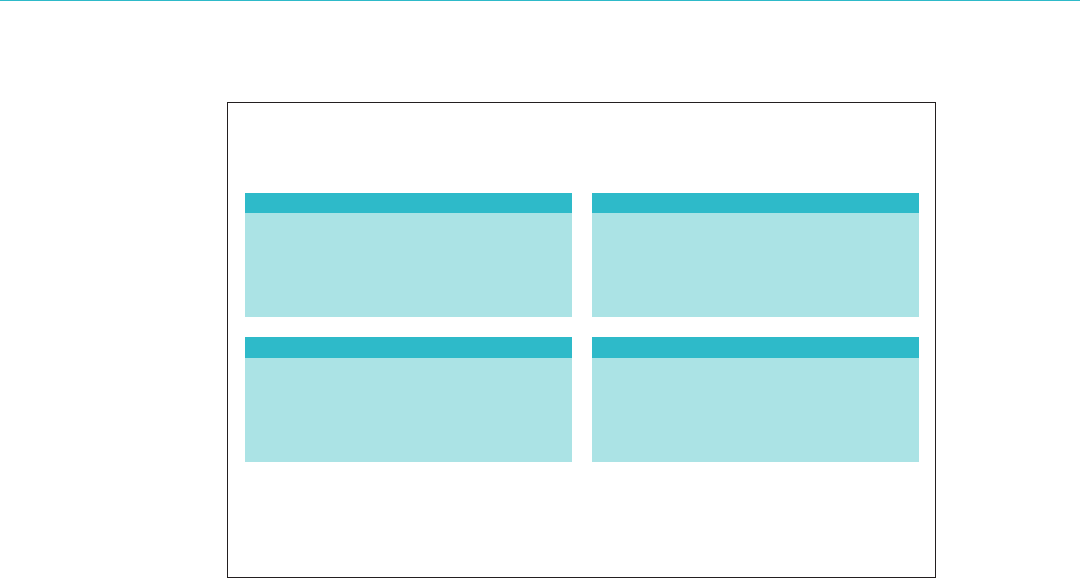

Summary of the Three Funding Windows of the Energy Resilience Fund

Boxes

Recommendation for the Viability Gap Fund Window of the Energy

Resilience Fund

Recommendation for the Project Development Fund Window of the

Energy Resilience Fund

Recommendation for the Credit Enhancement Fund Window of the

Energy Resilience Fund

I. Introduction and Background

T

he Government of Indonesia is exploring alternatives to introduce new energy

eciency and clean energy technology regulations that are of high importance

to the Sustainable and Inclusive Energy Program of the Asian Development Bank

(ADB). In particular, the government is looking at new financing and incentive models to

increase the deployment of clean and ecient technologies.

The increase and promotion of renewable energy generation resources are the priorities

of the government under the National Energy Policy and the Medium-Term Development

Plan –. However, recent policy changes have led to mixed results for renewable

energy development as the rules, regulations, and financial incentives enacted by the

government created an uneven playing field for renewable depending on the location, and

created questions over the long-term bankability and viability of projects. The high cost of

financing and the low power purchase agreement (PPA) taris are serious concerns and

roadblocks to renewable energy development in the country, which is why the government

intends to provide financial incentives for renewable energy developers via an Energy

Resilience Fund (ERF).

ADB has commissioned a study and a proposal by an independent consultant on possible

financing schemes for such an ERF, the rules and criteria governing access to the ERF, and

supporting the drafting of an initial concept for the ERF. An important premise for the

assignment is to avoid a complex financial structure and aim at a time-limited support

scheme that helps jump-start the development of renewable energy generation resources

and can be implemented on a fast-track basis.

It is important to understand that the ERF in this context does not have to mean a separate

new fund entity and structure, but the proposed ERF concept(s) can also be embedded

into one or more existing or planned structures in Indonesia.

The tasks of this study include but are not limited to the following:

(i) presentation of options for an ERF based on international experiences and a

review of Indonesia’s current situation;

(ii) suggestions for a basic structure and rules and criteria for access to the ERF; and

(iii) draft concept paper for an easy establishment and use of funding scheme.

This report summarizes the analysis, findings, and recommendations by the consultant

regarding a possible scope, structure, institutional design, as well as functioning and

Renewable Energy Financing Schemes for Indonesia

2

operation of an ERF. The report also discusses the potential sources of funding, based

on the nature and sizing of the financing instruments included in the ERF concept.

The current situation is described in chapter II. The data and analysis are based

on available reports and statistics concerning the Indonesian energy sector and

finance sector as well as bilateral discussions with various stakeholders. Most

of these stakeholder discussions were held during a fact-finding mission on

–August.

The barriers faced by renewable energy power generation projects in Indonesia are

idenfitifed and summarized in chapter III. Some of the barriers can be addressed by

various financing instruments, whereas some of them are of such nature that the

means of intervention other than financing have to be used. Therefore, many but not

all barriers can be addressed by the ERF concept presented in this report, but if other

issues are not addressed, the financing instruments alone might not help to jump-

start the renewable energy power generation market.

Chapter IV categorizes the barriers faced and identifies the main types of

financial interventions available to address such barriers. These interventions

include (i)viability gap funding, (ii) project development funding, and (iii) credit

enhancement funding.

Description and analysis of pros and cons of possible financing instruments for

each type of financial intervention are provided in chapter V. The list of financial

instruments identified and evaluated in the chapter is not exhaustive (theoretically,

there could be an indefinite number of instruments), but it makes an attempt to list

the main instruments mostly used to address similar investment barriers in renewable

energy markets in other countries. Chapter V also makes a suggestion on preferred

financial instrument(s) for each type of financial intervention needed.

Chapter VI includes a review of similar schemes in other countries. The chapter

takes the suggestions in chapter V as a starting point, and provides successful

real-life examples of each proposed financial instrument from other countries.

The description and evaluation of instruments and experiences in other countries

also include an assessment to which extent these experiences are applicable in the

context of Indonesia.

Chapter VII makes a proposal for institutional setup, governance structure,

organization, and a rough assessment of needed resources and expertise of the ERF.

The more detailed concept for each of the three funding windows of the ERF

(Viability Gap Fund [VGF], Project Development Fund [PGF], and Credit

Enhancement Fund [ECF], and the technical assistance embedded in these) is

presented separately for each funding window in chapter VII to chapter X. The

concept design addresses the following topics separately for each proposed window

(or financing instrument):

Introduction and Background

3

(i) description of the instrument,

(ii) eligibility criteria,

(iii) main terms and conditions of the instrument,

(iv) solicitation and selection process,

(v) timing and volume considerations, and

(vi) technical assistance needs.

Chapter XI addresses the challenges to capitalize the ERF and potential sources of

funding. Since the funding instruments are fundamentally dierent from each other

(especially the VGF), this discussion is split in separate subchapters for each of the

three instruments. The discussion includes the type of funding needed for each

financing instrument, volume and sizing aspects, as well as potential sources available

for each type of funding and possible blending of dierent types of financing within

the ERF.

W

ith its over million people, Indonesia has the fourth largest population

in the world. At the same time, the per capita power consumption is low,

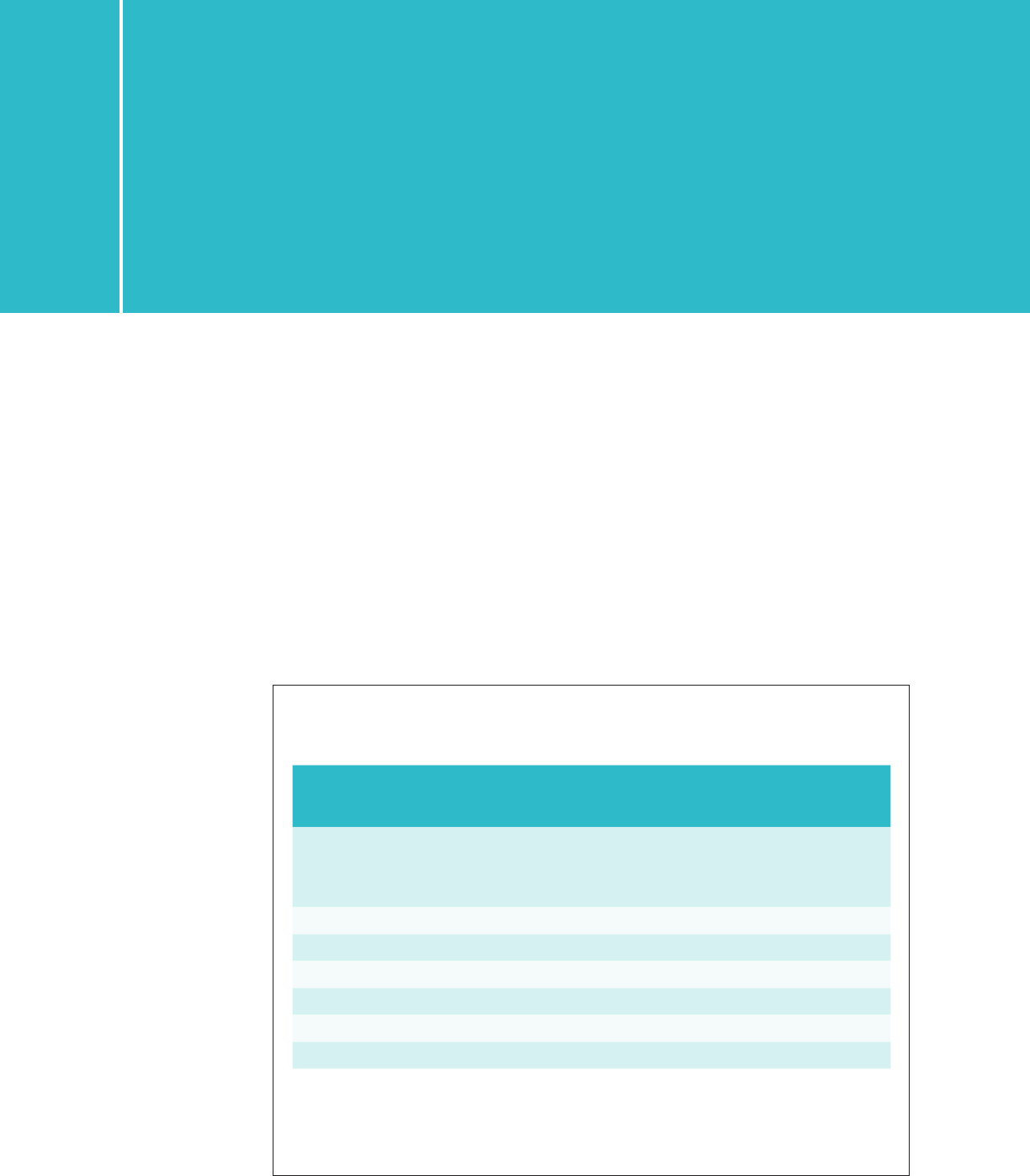

about megawatt-hour (MWh) in , leading to total power demand of

terawatt-hours (TWh), total installed capacity of about gigawatts (GW) and power

generation of about TWh, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC ).

The economy of Indonesia is estimated to grow at per annum in the next years (The

Economist ). At the same time, the growth of power consumption is estimated to be as

high as ., leading to more than doubling of electricity demand to TWh by and

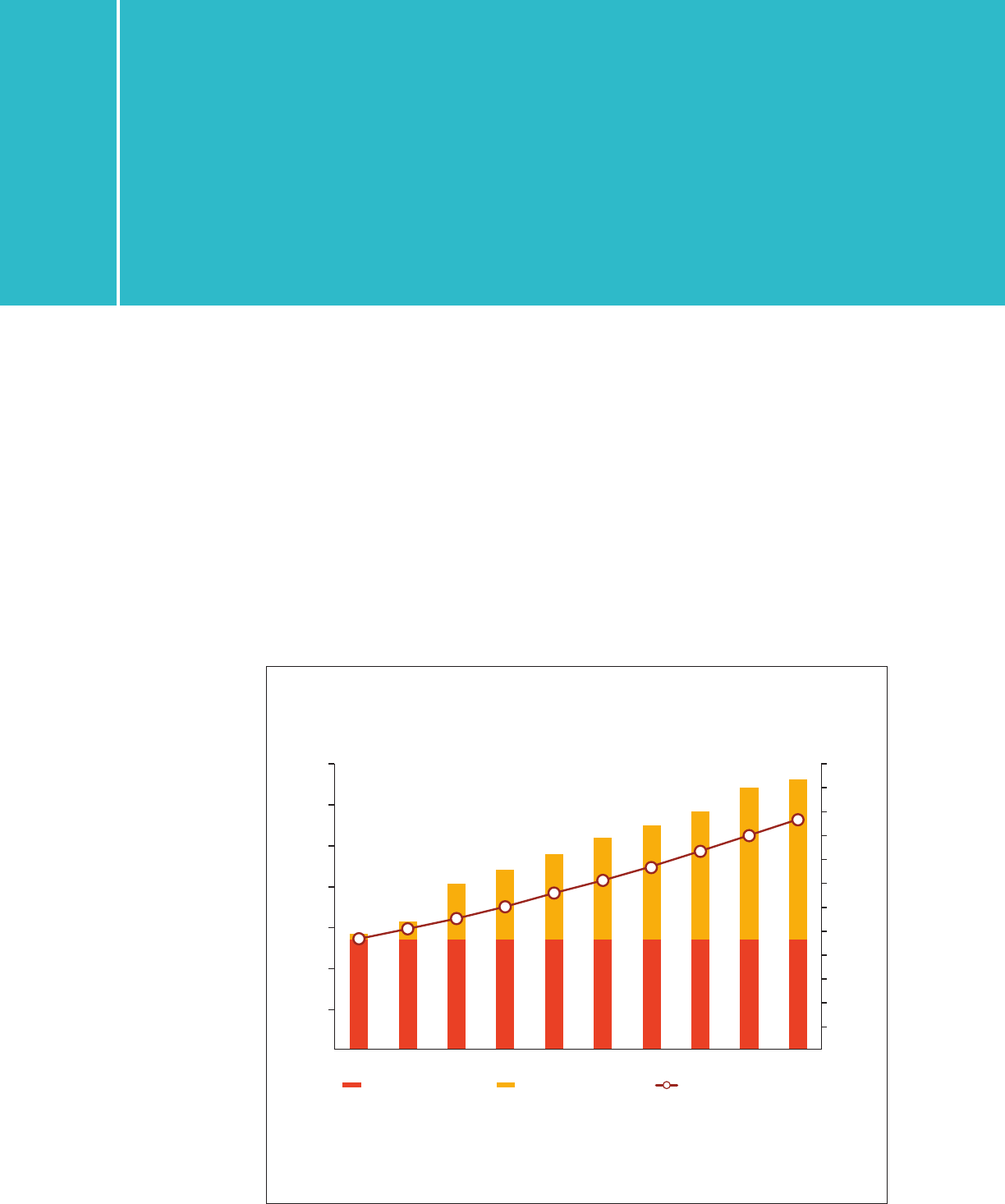

installed power generation capacity to GW as shown in Figure (PT Perusahaan Listrik

Negara ). In other words, by the power consumption will increase by about

TWh and the installed capacity by GW.

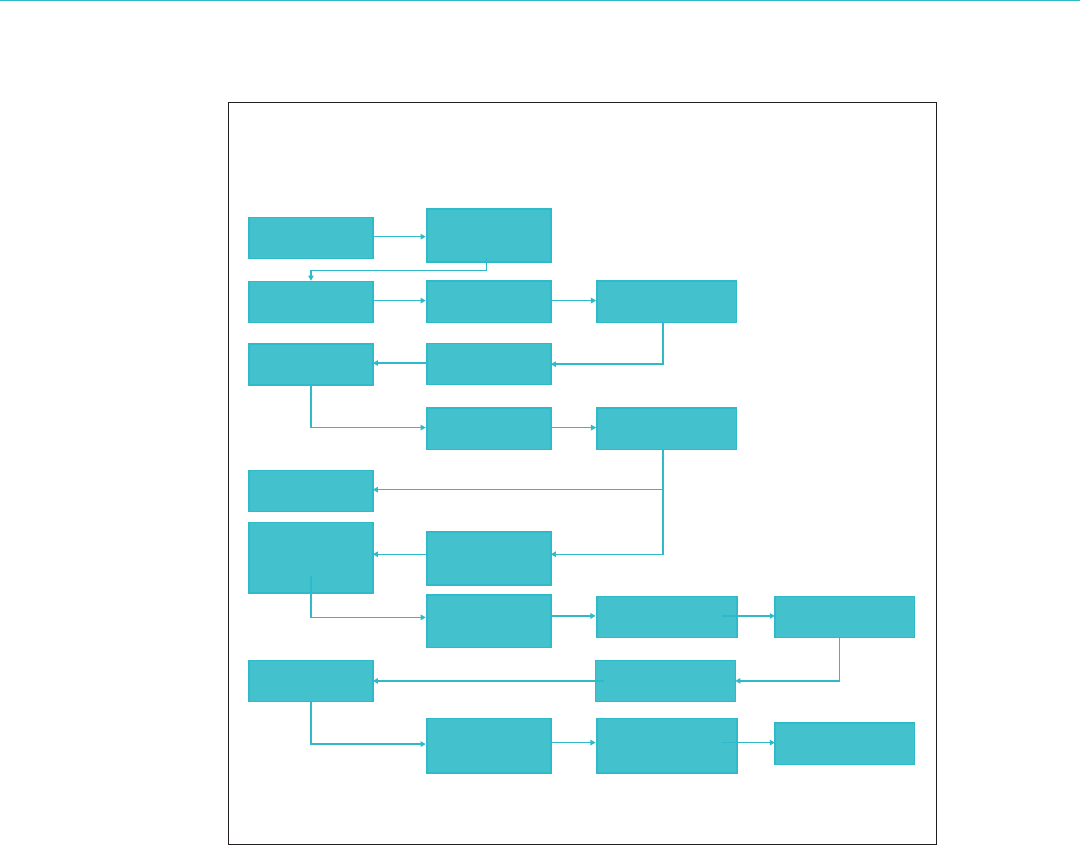

Figure 1: Development of Power Demand and

Installed Generation Capacity

(–, according to Rencana Umum Penyediaan Tenaga Listrik)

GW gigawatt, GWh gigawatt-hour, MW megawatt, TWh terawatt-hour.

Sources: State electricity company PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara () and

PricewaterhouseCoopers ().

Total capacity (GW)

TWh

140 600

550

500

450

400

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

120

100

80

60

40

20

2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 2026

Electricity demand (GWh)Existing capacity (MW) Additional capacity (MW)

II. Current Situation

Current Situation

5

Another challenge in the power sector in Indonesia is the rapid increase of the use of

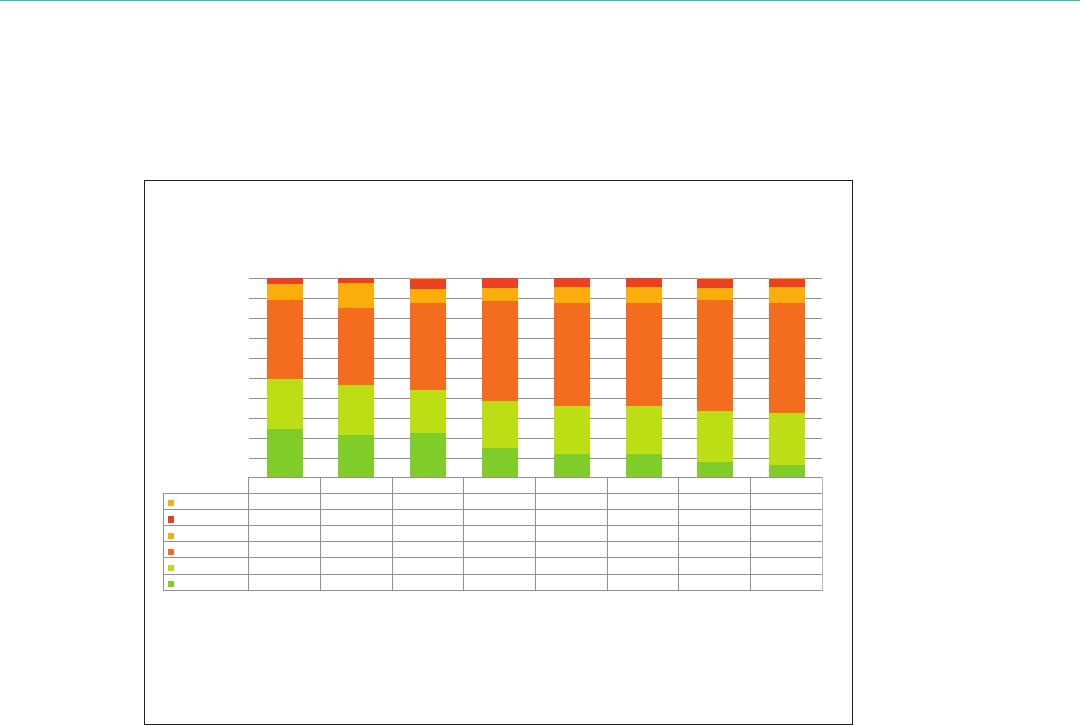

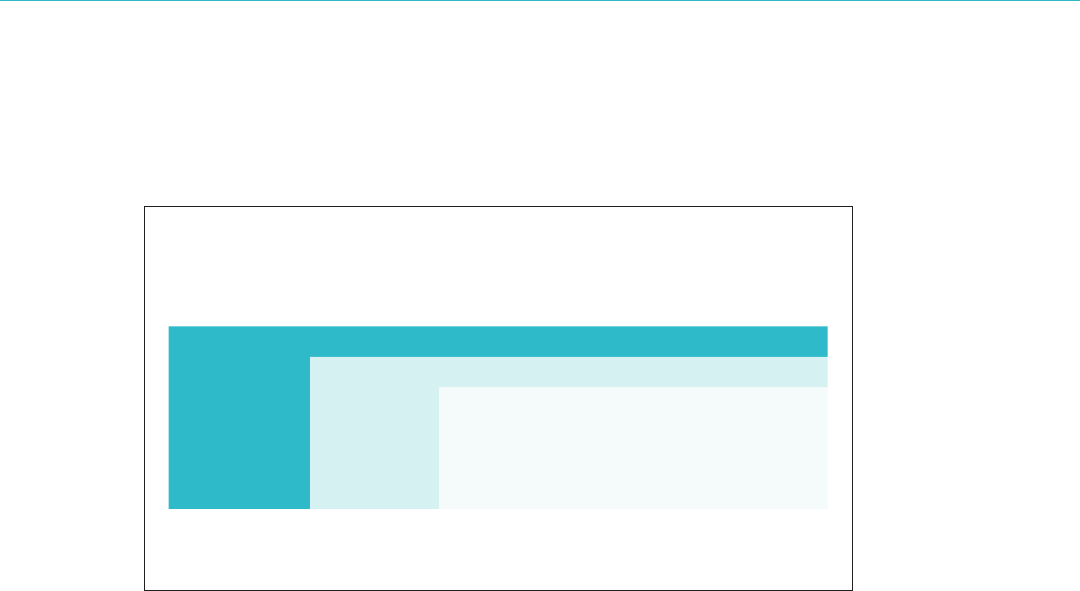

coal and generally high dependence on fossil fuels, as shown in Figure .

Although Indonesia is committed to a greenhouse gas emission reduction target

from the baseline in its Nationally Determined Contribution to the Paris climate

agreement under the United Nations Framework on Climate Change (UNFCCC),

and has a conditional commitment to reduction with international climate

finance (IRENA ), it has not been able to remarkably increase the share of

low-carbon power generation in its power generation mix. Instead, the share of coal

has increased from below to about today, and the share of all fossil fuels in

power generation mix has remained close to during the whole decade.

Increasing the share of renewable energy in the total energy mix would be good not

only for Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emission reduction targets but also for gross

domestic product, employment, trade balance, and welfare. According to IRENA

(), accelerated renewable energy deployment to double the share of renewable

energy in the energy mix from to could increase Indonesia’s gross

domestic product by .–. in compared with baseline, mainly as a result

of higher overall levels of investment in the energy sector. Indonesia’s trade balance

could improve by .–. by . The number of renewable energy-related

jobs in Indonesia could increase to . million by , respectively, compared with

about , in . At present, more than of renewable energy jobs are

in the labor-intensive palm oil-based biodiesel industry, but mobilizing investment

in the electricity and industry sectors, for example, would lead to diversification of

renewable energy-related jobs in Indonesia. The increased share of renewable energy

would also lead to positive social and environmental impacts, such as reduction of

Other NRE

Geothermal

Hydro

Coal

Gas

Oil

100%

0.00%

3.00%

8.00%

39.00%

25.00%

25.00%

0.00%

3.00%

12.00%

38.00%

25.00%

22.00%

0.07%

5.13%

6.80%

44.06%

21.00%

22.95%

0.11%

4.85%

6.39%

50.27%

23.41%

14.97%

0.16%

4.42%

7.73%

51.58%

23.56%

12.54%

0.11%

4.44%

6.70%

52.87%

24.07%

11.81%

0.20%

4.34%

5.93%

56.06%

24.89%

8.58%

0.24%

4.33%

7.88%

54.69%

25.89%

6.97%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Figure 2: Development of the Power Generation

Mix in Indonesia in 2009–2016

NRE new and renewable energy.

Sources: PricewaterhouseCoopers () and Laporan Kinerja Direktorat Jendaral

Ketenagalistrikan ().

Renewable Energy Financing Schemes for Indonesia

6

local pollution and related negative health impacts and environmental and material

degradation.

However, renewable energy power generation is facing a number of challenges that

are prohibiting project development pipeline from being implemented. For example,

currently, there are small-scale renewable energy projects and project developers

under the independent power producer (IPP) scheme that have signed a PPA with

the PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN, State Electricity Company), but which face

challenges to implement the projects. Some of these challenges are attributable to

the resources and capabilities of the project developers to develop bankable projects,

but it is also widely accepted that the PPAs signed between IPPs and the PLN are not

bankable. One reason in many cases is the very low-price level, but also other terms

and conditions are posing prohibitive challenges to raise financing to implement

these projects. Also, PLN’s lack of experience in managing variable renewable energy

generation as part of the power mix is seen as a challenge by some stakeholders.

These challenges are identified and discussed more in the next chapter.

Further, based on the stakeholder discussions during the fact-finding mission, it is

not likely that, in the short term, the existing or new PPAs signed by the PLN would

be modified to have cost-reflective taris making the internal rates of return (IRRs)

of the projects sucient to make them bankable. It was also considered unrealistic

by various stakeholders to propose a new regular competitive auction scheme for

renewable energy, whereby the PLN would invite bids and award bankable long-term

PPAs through IPP or public–private partnership (PPP) schemes. Therefore, in the

near future, any fund structure should be based on the current state of unoptimal

and (at least in many cases) non-bankable PPAs with too low prices. According

to stakeholder meetings during the fact-finding mission, the same applies to the

concessions under the electrification scheme, which is another current and important

part of the renewable energy project pipeline in Indonesia.

Reflecting the current situation against the design criteria for the contemplated

Renewable Energy Fund (REF), specifically that the REF should “avoid a complex

financial structure and aim at a time-limited support scheme that helps jump-start

the development of renewable energy generation resources and can be implemented

on a fast-track basis,” it can be concluded that:

(i) the REF concept should not assume project development and PPA

procedures, nor the terms of PPAs, as currently applied by PLN to be

changed, but the REF should work in the current context;

(ii) the same applies to other renewable energy sectors, including concessions

under the electrification scheme;

(iii) therefore, the most feasible way forward to jump-start the renewable energy

market with a time-limited support scheme implemented on a fast-track

basis is to create “PPA- and concession-external” interventions only;

(iv) jump-starting the market fast also indicates that the intervention should

target the existing project pipelines—instead of proposing to create new

project pipelines, which is time consuming;

Current Situation

7

(v) even if the current project pipelines consist mostly of small-scale projects

(such as IPP and electrification schemes), this seems to be a needed step

to help create and mobilize the renewable energy market in Indonesia, and

also beneficial from PLN’s perspective to gain experience and track record to

manage variable renewable energy generation in its power system;

(vi) therefore, the REF concept proposed in this report could also be called

“phase interventions”;

(vii) if the proposed “phase interventions” in this report are implemented and

turned out to be eective, the target, scope, and resources of the REF can be

expanded in the next phase to provide more funding to a larger number of

larger projects;

(viii) therefore, one of the first steps of jump-starting the market is likely to be

a demonstration and piloting phase in the range of MW and less than

TWh of new generation, while the needed scale of tens of gigawatts should

be targeted in the next phases; and

(ix) therefore, the objective of the REF is building the market and capabilities as

much as adding new renewable energy capacity, which should be clearly seen

in the structure, modalities, and resource allocation of the REF.

he main challenges for financing renewable energy power generation investments

have been analyzed in earlier studies and identified as:

(i) low taris, making renewable energy investments unprofitable in many cases;

(ii) high interest rates of loans, further reducing the returns of typically capital-

intensive renewable energy investments;

(iii) high collateral requirements and absence of project finance, making it dicult to

raise debt financing for renewable energy investments;

(iv) build–own–operate–transfer (BOOT) structure in PPAs, instead of build–own–

operate structure;

(v) project scale of small and medium-sized projects increases the project

development and transaction costs, and related risks in relation to investment cost,

creating challenges to do high-quality project development work, which reduces

options in financial structuring and arrangements (especially project finance);

(vi) capacity of project developers (technical and financial) and financial institutions

(technical) is too limited on average, making it challenging to develop high-

quality projects by developers, and evaluating projects and structuring finance by

financiers;

(vii) local content requirements make it challenging to design projects in a cost-

ecient way; and

(viii) uncertainty related to requirements, timelines, and outcomes of licensing and

permitting procedures create unreasonably high risks for project developers.

Removing or mitigating the above investment barriers requires work by and cooperation

between multiple stakeholders in various forms. In fact, removing a single barrier often

requires more than just one intervention by one stakeholder. Therefore, also a potential

REF could help overcome many but not all of the challenges, and not all of them alone.

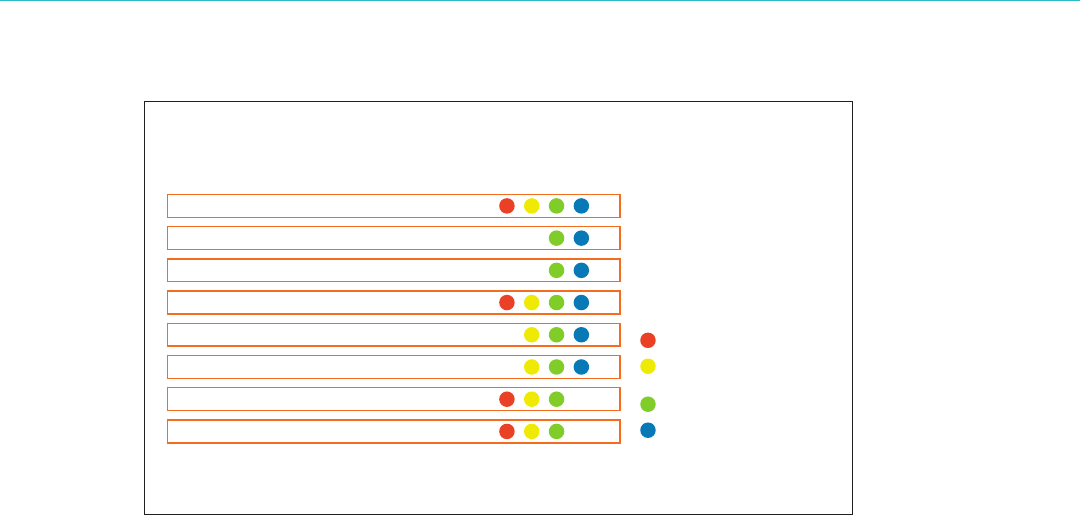

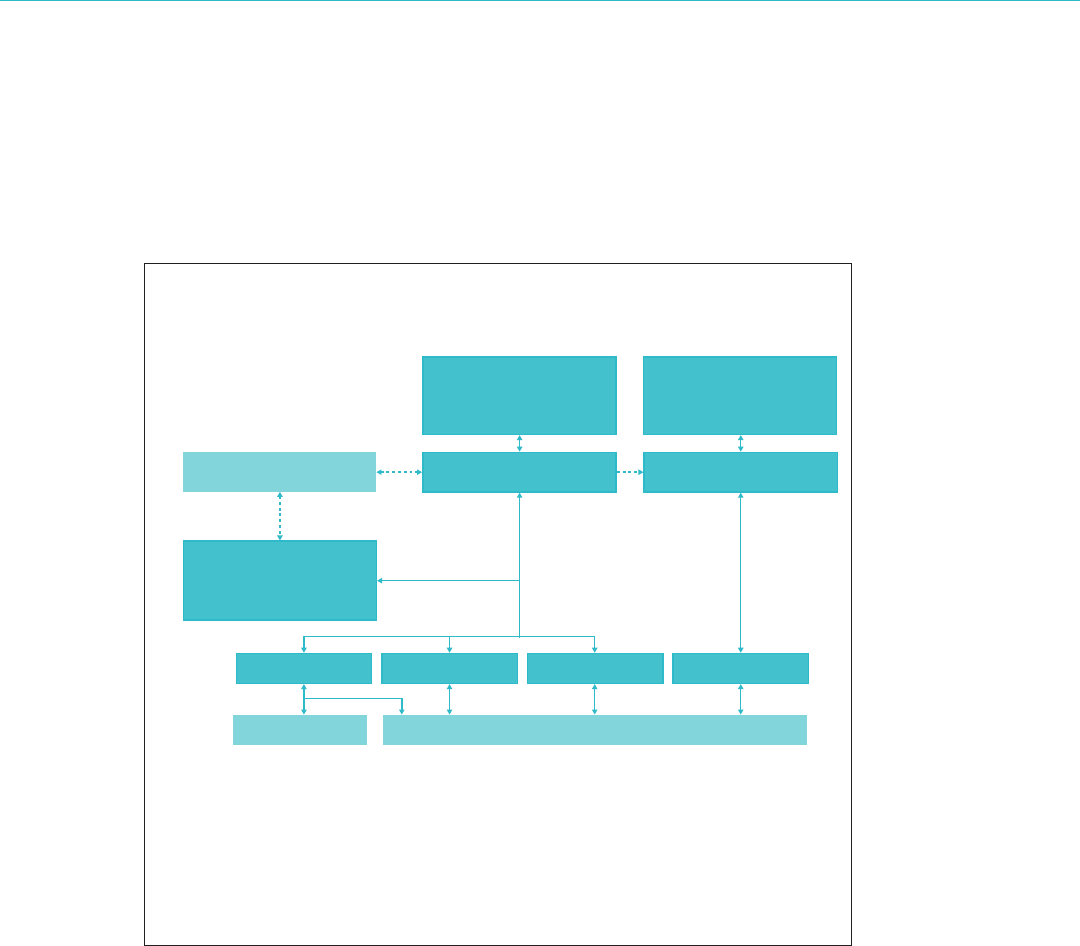

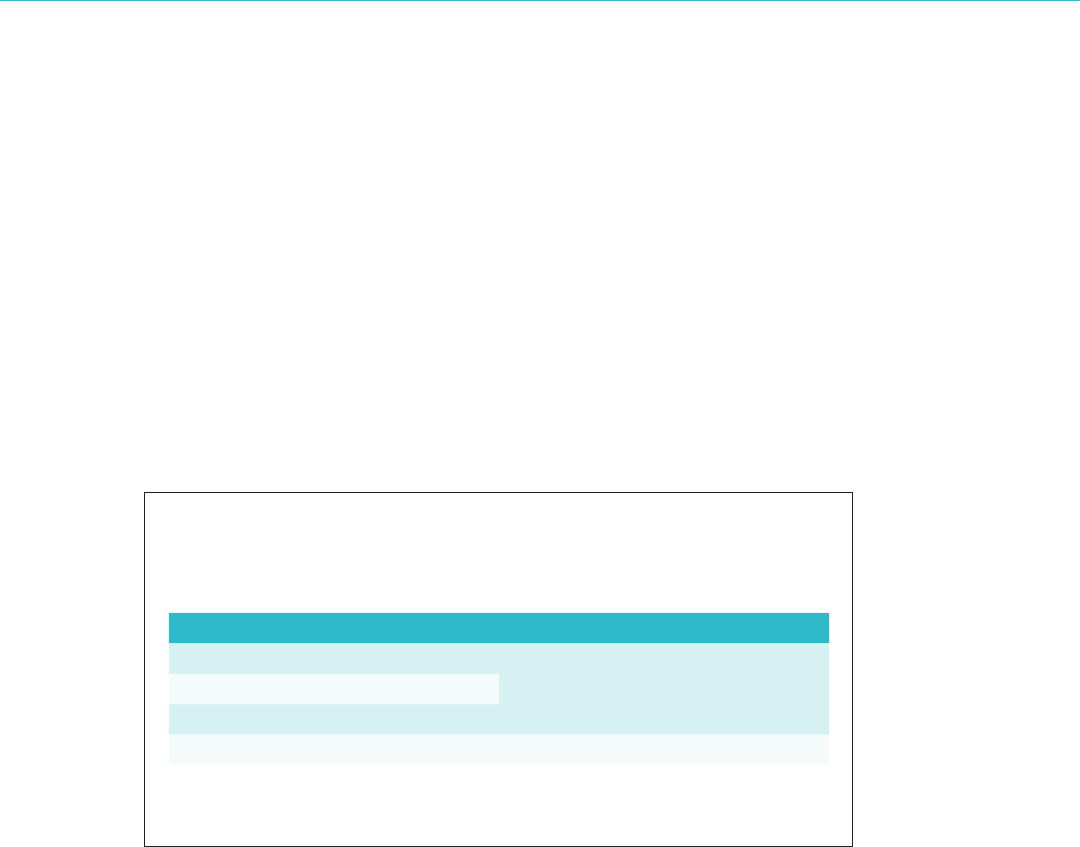

Figure summarizes the relevant investment barriers, and the primary stakeholder groups

needed to address each of them.

Financial institutions—private or public—are not capable of eciently solving challenges

related to local content, license, and permit issues. These need to be addressed by the

government and regulators, preferably in cooperation with project developers and sponsors.

In contrast, the first six challenges can be directly addressed by financial interventions

and institutions, especially public financial institutions, and in close cooperation with the

government and the power utility in most cases.

III. Challenges

T

Challenges

9

Theoretically, some of these barriers would be most eciently addressed by

improving the investment frameworks to reduce the real underlying risks and

internalize external costs and benefits. However, in a second-best world, such barriers

may exist, therefore justifying the need for financial interventions. This does not

mean that the government, electricity utility, regulators, developers, sponsors, banks,

and other stakeholders should not work toward developing a better investment

framework to reduce the need for specific financial interventions and direct subsidies.

In fact, as mentioned, one of the main objectives of the proposed ERF concept is to

help the relevant stakeholders build capabilities and improve market and investment

frameworks.

The proposed ERF concept seeks to find solutions to mitigate, or contribute positively

to the mitigation of, the following investment barriers labeled with blue dot in

Figure:

(i) typically, too low tari (e.g., PPAs or concessions), making the internal rate of

return (IRR) of renewable energy investments too low for investors;

(ii) high interest rates of debt, leading to high cost of finance of projects,

therefore reducing the (equity) IRR further and making the investments less

attractive to investors;

(iii) high collateral requirements by banks, making it dicult to raise debt in the

absence of large balance sheets by developers and project sponsors;

(iv) BOOT structure of PPAs limiting the potential revenue-generation period of

projects;

(v) project scale and related high development and transaction costs in relation

to size of the total investment, combined with generally high-risk profile of

project development; and

(vi) limited financial and technical capacity of project developers, and limited

technical capacity, experience, and track record of financial institutions.

1. Tariff

2. Loan interest

3. Collateral

4. Build–operate–own–transfer

: Government

: PT Perusahaan Listrik Negar

a

(State Electricity Company)

: Developer/investor

: Financial institutions

5. Project scale

6. Project developer and financial institution capacity

7. Local content

8. License and permits

Figure 3: Investment Barriers and Relevant Stakeholders

to Address Them

Source: ADB.

Renewable Energy Financing Schemes for Indonesia

10

The following section will elaborate each of these challenges separately and present

potential solutions to them. The list of financial instruments or approaches is not

exhaustive since, theoretically, there could be an indefinitive amount of financial

interventions. The objective is to list all the main instruments that are mostly used

to address similar barriers in various countries around the world. The defined design

parameter that is “easy-to-implement” also justifies using experiences and lessons

from existing and tested solutions in other countries as much as possible.

S

ome of the listed barriers share same features and/or causes. Therefore, it may be

feasible to try to cluster the barriers. This enables both finding suitable financial

interventions and reducing the amount of the financial interventions; some of the

barriers can be addressed by one type of intervention. The identified barriers that can be

targeted through financial interventions can be grouped into three, which will be discussed

in this chapter:

(i) viability gap or lack of profitability,

(ii) lack of technical and financial resources during project development stage, and

(iii) lack of debt finance at reasonable terms and conditions.

A. Viability Gap or Lack of Profitability

In Indonesia, the renewable energy power taris in grid-connected projects depend on the

location and are generally set at maximum or of the prevailing tari in the same

region as applied by the PLN. In many cases, this tari level is too low to provide suciently

high return for project sponsors on their investment. In addition, the definition of

“maximum tari” means that PLN, as the otaker, has certain level of freedom to negotiate

these taris case by case, making the pricing process intransparent and the resulting PPA

prices dicult to estimate beforehand by developers. These are fundamental issues that

have to be solved by defining a tari level that is sucient for project sponsors to make an

investment decision, and the level of which is established in a clear and transparent way.

The main approaches to address the viability and profitability issues in other countries are:

(i) fixed feed-in tari,

(ii) fixed premium,

(iii) competitive auctioning of long-term PPAs,

(iv) competitive auctioning of a top-up premium on top of predetermined tari or

market price, and

(v) investment grants.

Among the most fundamental dierences is the award or selection process. Traditionally,

during the previous decade, the “first come, first served” approach was more popular, i.e.,

developers and sponsors whose projects met certain predetermined eligibility criteria were

automatically granted the predetermined fixed feed-in tari or premium tari, or were

awarded this tari after case-by-case evaluation against such eligibility criteria.

IV. Definition of Design Parameters

and Design Options

Renewable Energy Financing Schemes for Indonesia

12

In this decade, dierent types of competitive auctioning procedures have come to

dominate the selection and award processes of PPAs and premium taris, both in

developed and developing country renewable energy markets. Typically, auctioning

is arranged so that the lowest bids until the targeted volume is contracted will be

awarded a bankable long-term PPA at the price (/MWh) the bidder indicated in

its bid (pay-as-bid). Subsequently, the national utility or other market operator is

required (as the counterparty to the PPA) to o-take the power generated by the

project at the specified pay-as-bid price.

In rarer cases, the competitive auctioning has concerned a premium that is paid on

top of the prevailing tari or PPA or a wholesale power market price. In such schemes,

the awarded projects will sell the power in the market (or under the PPA) according

to normal regulations or the market price and will receive a premium on top of the

market price or prevailing regulated tari (i.e., primary revenue stream). The reasons

for auctioning the premium instead of the total price of electricity have been twofold

in dierent countries.

First, premium taris have been seen as less market-distorting in more privatized and

competitive electricity markets where the market price fluctuates and the producers

have to continuously respond to the price signal provided by the changes in supply

and demand balance. If the renewable energy producers were awarded a fixed-

price PPA (instead of a premium on top of the market price), the renewable energy

producers would have no market price risk and not need to take the fluctuations

in supply and demand and the resulting price fluctuations into account; thereby

lowering the average market price, increasing the price volatility in the market, and

causing market distortions. This is one of the reasons why, for example, Finland chose

to go for competitive auctioning of long-term premium rather than PPA for renewable

energy projects.

Second, in some cases, it may be useful to clearly and transparently separate the

subsidy or incentive component from the base power price or tari. This is related

to the funding of the scheme. Again, for example, in Finland where the additional

cost is charged to taxpayers, it has been seen important to distinguish clearly the

subsidy component from the market price component (in addition to aiming for

less market-distortion). Similarly, in some developing countries where development

finance institutions may provide funding to support such schemes, it is important

to distinguish the base tari or PPA price and the premium component clearly, and

in an unambiguous manner since the funding for these revenue streams come from

dierent sources.

Of the PPA auctions, there is a vast amount of increasingly encouraging examples,

and, in fact, it has become globally the main approach to award PPAs and determine

price levels in the renewable energy sector. Of the premium auctions, the Global

Energy Transfer Feed-in Tari (GET FiT) scheme of German development

cooperation through Kreditanstalt für Wiederauau (KfW, Credit Institute for

Reconstruction) in Uganda and Zambia, as well as the auctioning scheme to be

implemented in Finland in are good examples, and will be described in more

detail later in this report.

Definition of Design Parameters and Design Options

13

Investment grants have been more popular in the early days of renewable energy

technologies and are still used often in the context of newer and still unproven

technologies. However, investment grants are less typical when promoting mature

renewable energy technologies; the profitability is typically stimulated by enhancing

the cash flows of the project rather than contributing to the initial investment cost

directly. But both systems exist and, in some cases, are even used as a combination, as

will be shown later.

B. High Transaction Costs, Risks of Project Development,

andLimited Capacity by Developers and Financial Institutions

Renewable energy investments are often (although not always) smaller compared

with conventional power generation projects. More often, the renewable energy

projects are in the range of single- and double-digit MW of installed capacity,

whereas the conventional power generation projects are in the range of double- or

three-digit MW of installed capacity, or more. For example, in project finance (also

known as non- or limited-recourse lending), smaller banks often have a lower limit

of million– million for projects, and in larger banks the lower limit can be in

the range of million– million because of high transaction costs of project

finance. Also, since permitting and other regulations tend to be less clear for newer

renewable energy tehchnologies than they are for conventional power generation

investments, the relative risks, project development, and transaction costs tend to

be higher and lead times longer, reducing the incentive for project development, and

increasing the required returns (i.e., cost of capital) and, therefore, the levelized cost

of electricity for renewable energy investments.

Also, renewable energy project developers tend to be more diverse, many of them

being small and medium-sized enterprises with limited financial (and sometimes

also technical) capacity to produce high-quality documentation and develop

high-quality projects that are solid enough to obtain needed permits, licenses, and

financing.

The identified challenges can be bundled in a broad group of project development

stage barriers and related financial challenges. In the context of renewable energy

project development, typical financial interventions that have been used to address

these challenges are the following:

(i) Technical assistance and capacity building, i.e., by providing external

experts free of charge to help not only project developers but also lenders

and regulators in project development process; this provision of external

expertise can be both direct project-specific support and more general or

programmatic activity, such as training and education.

(ii) Provision of grant funding for project developers, which help them to

develop higher-quality projects and related documentation, especially by

using external experts (technical, financial, legal, and others) to produce

bankable resource analyses and production estimates, grid studies,

environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs), technical design

Renewable Energy Financing Schemes for Indonesia

14

documents, financial models and plans, drafting bankable agreements, and

other required documentation.

(iii) Provision of risk finance for project developers to help them do the same.

Project development support has often been based on provision of technical

assistance and cash grants on a discretionary basis after case-by-case evaluation.

However, more recently, (i) more competitive selection procedures (e.g., so-called

“challenge funds”), as well as (ii) use of more financial instruments and reimbursable

grants can be observed.

C. High Perceived Risk by Banks and Other Financial Institutions

High perceived risk by lenders can result in higher required returns (i.e., interest rates)

and stricter risk mitigation measures (including collateral, liquidity, and covenants).

In this case, the main barriers resulting from high perceived risk are high interest rates

required and short tenors allowed by financial institutions (Barrier ) and excessive

collateral requirements (Barrier ). In addition to real risks, these issues can result

from (i) lack of information, understanding, and track record; (ii) lack of or conflicting

incentives; and (iii) lack of competition among financial institutions because of

shallow domestic capital market.

In some stakeholder meetings, it has been observed that the banking sector in

Indonesia is generally much more accustomed to corporate (balance sheet) finance

and less to project finance.

In this context, typical financial interventions that have been used to address lending

challenges are:

(i) providing partial guarantees for lenders either covering part of all credit risks,

or covering certain specific risks;

(ii) colending between development finance institutions (who may have more

experience and/or higher risk tolerance) and commercial lenders;

(iii) onlending whereby development finance institutions provide credit lines for

commercial lenders on softer or concessional terms, who then can blend

this funding with their own commercial funding when exending debt for

renewable energy investing;

(iv) a debt fund operating as an independent lender, which may or may not invest

together with commercial lenders;

(v) interest rate subsidy or interest rate buy-down as a direct subsidy for banks

and project sponsors to pay part of the interest rate required by the banks

that is seen excessive from projects’ perspective, thereby lowering the cost of

capital of renewable energy investments; and

(vi) capacity building for financial institutions to help them understand

renewable energy investments and to support them in investment appraisal

and financial structuring.

The aforementioned approaches may enable private financial institutions to

(i)extend debt to renewable energy investments at reasonable terms and conditions

Definition of Design Parameters and Design Options

15

even in the existence of high perceived risk and (ii) gain experience, build capacity,

and track record to provide debt with limited or no support in further lending to

similar investments. There are remarkable dierences between the approaches.

Guarantees on one hand are indirect funding, i.e., in the base case the funds are not

disbursed at all, just committed to cover potential losses borne by lenders. Colending

and onlending as well as stand-alone debt fund are direct financing in the sense that

the funds are actually disbursed and used to implement projects, and become part

of the renewable energy project’s balance sheet, and will be gradually repaid with a

return. Finally, the interest rate buy-down is a direct subsidy instead of a financing

instrument. In contrast to guarantees and lending, it is not repaid or released and it

will not generate returns; it is “lost money” by definition from the ERF’s point of view.

This can also be seen as a rough order of prioritization between these instruments:

the better functioning, deeper, and more liquid debt capital market, the more it

usually makes sense to provide guarantees in the first place and let the debt capital

market reprice the debt and do the lending. If the capital market is too shallow,

illiquid, or otherwise nonfunctional, the case for direct colending and onlending, or a

stand-alone debt fund, may become more relevant. Finally, if nothing else works, and

a direct subsidy intervention is needed, the interest rate subsidy may be an option.

However, it is recommendable and usually more cost ecient first to seek ways to

reduce the real and perceived risk and incentivize the market to reduce the interest

rates.

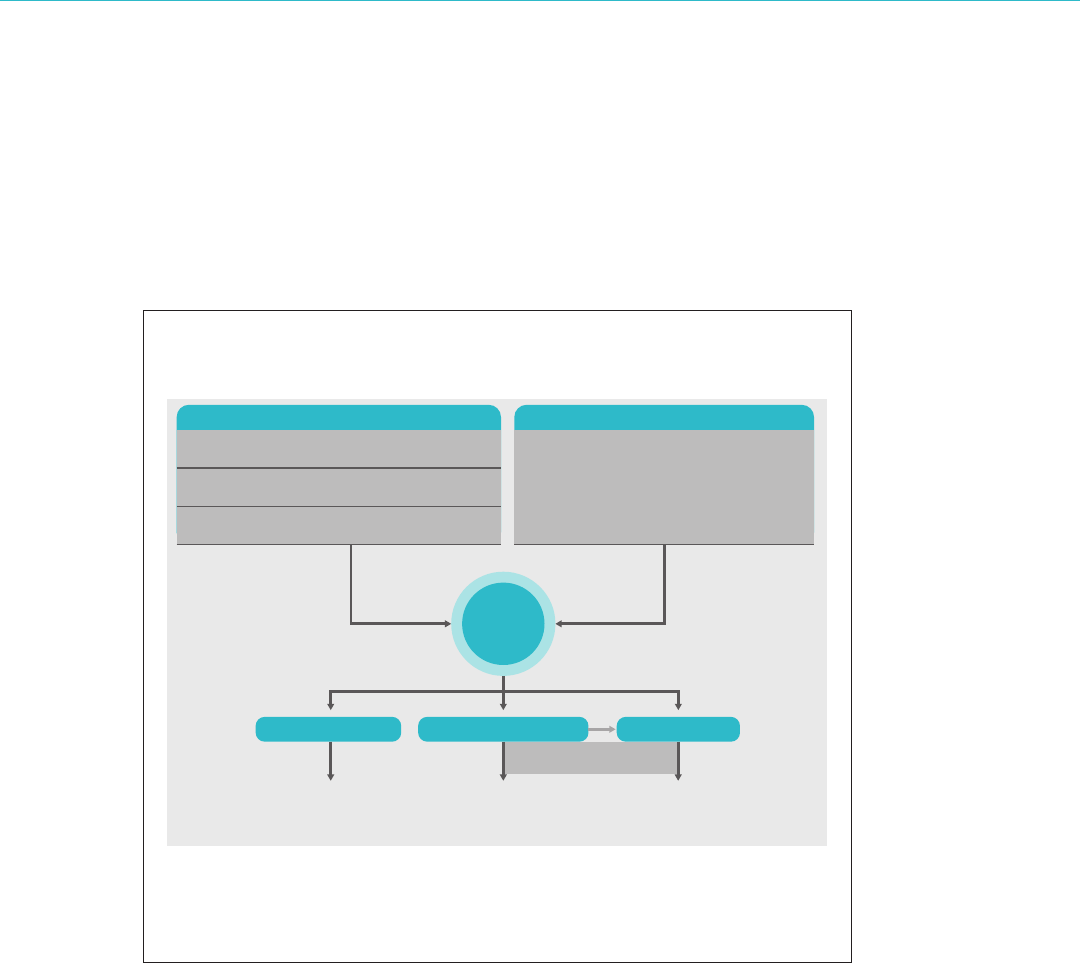

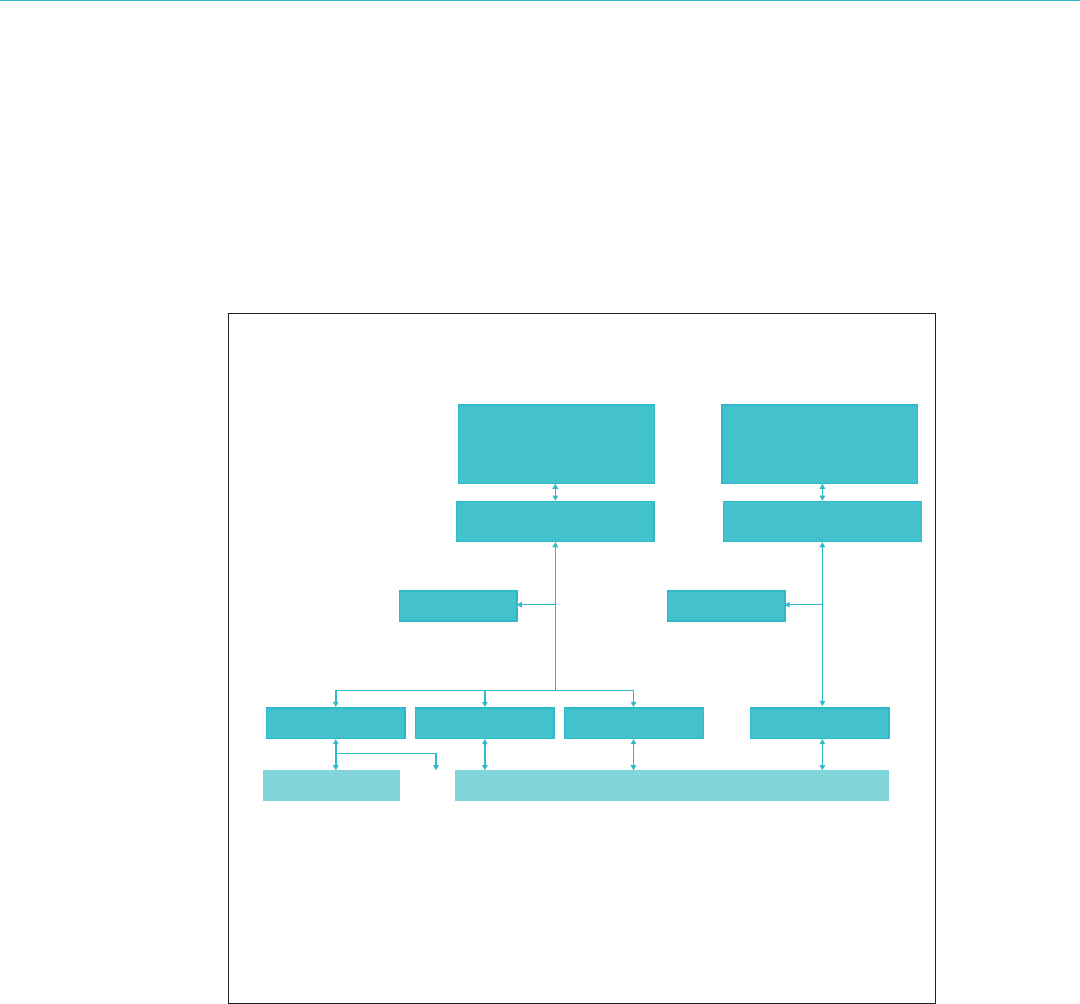

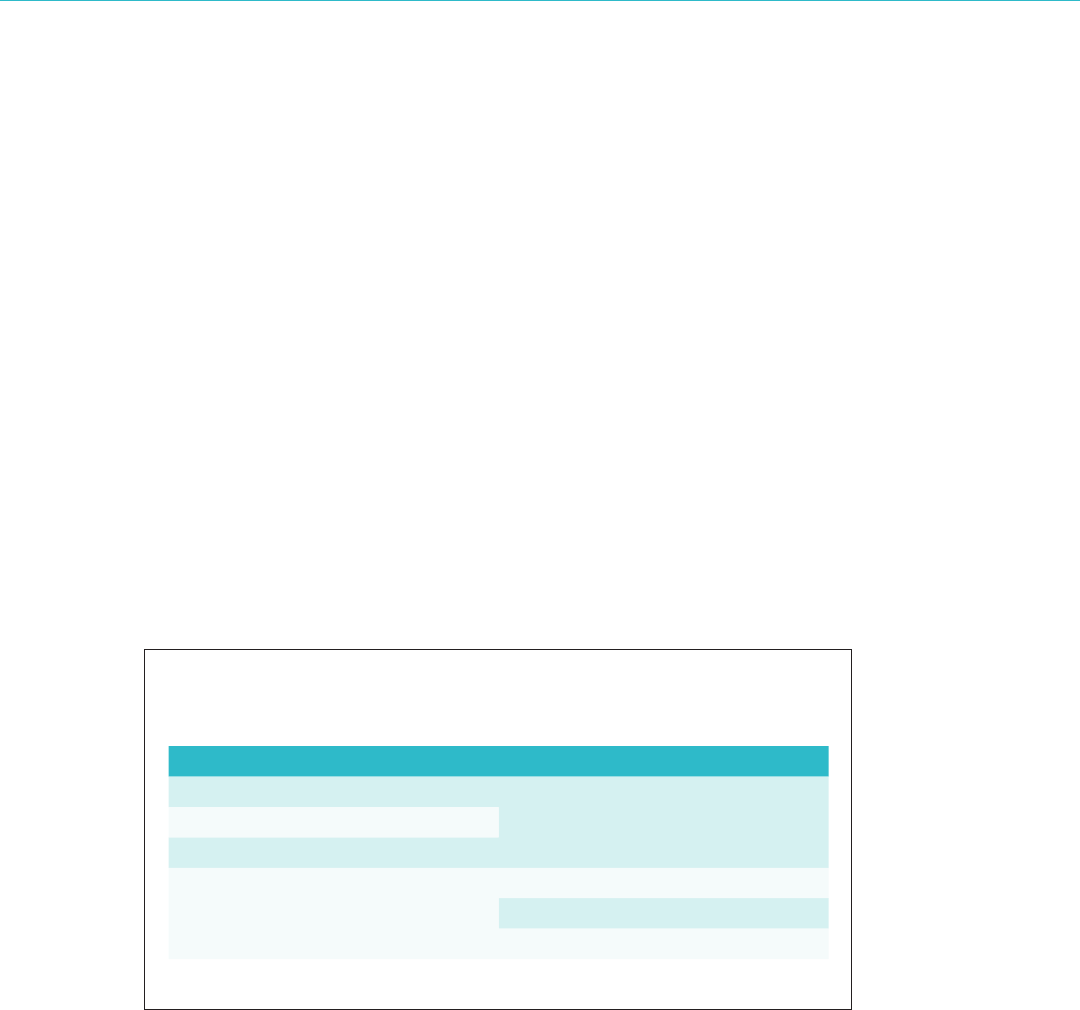

B

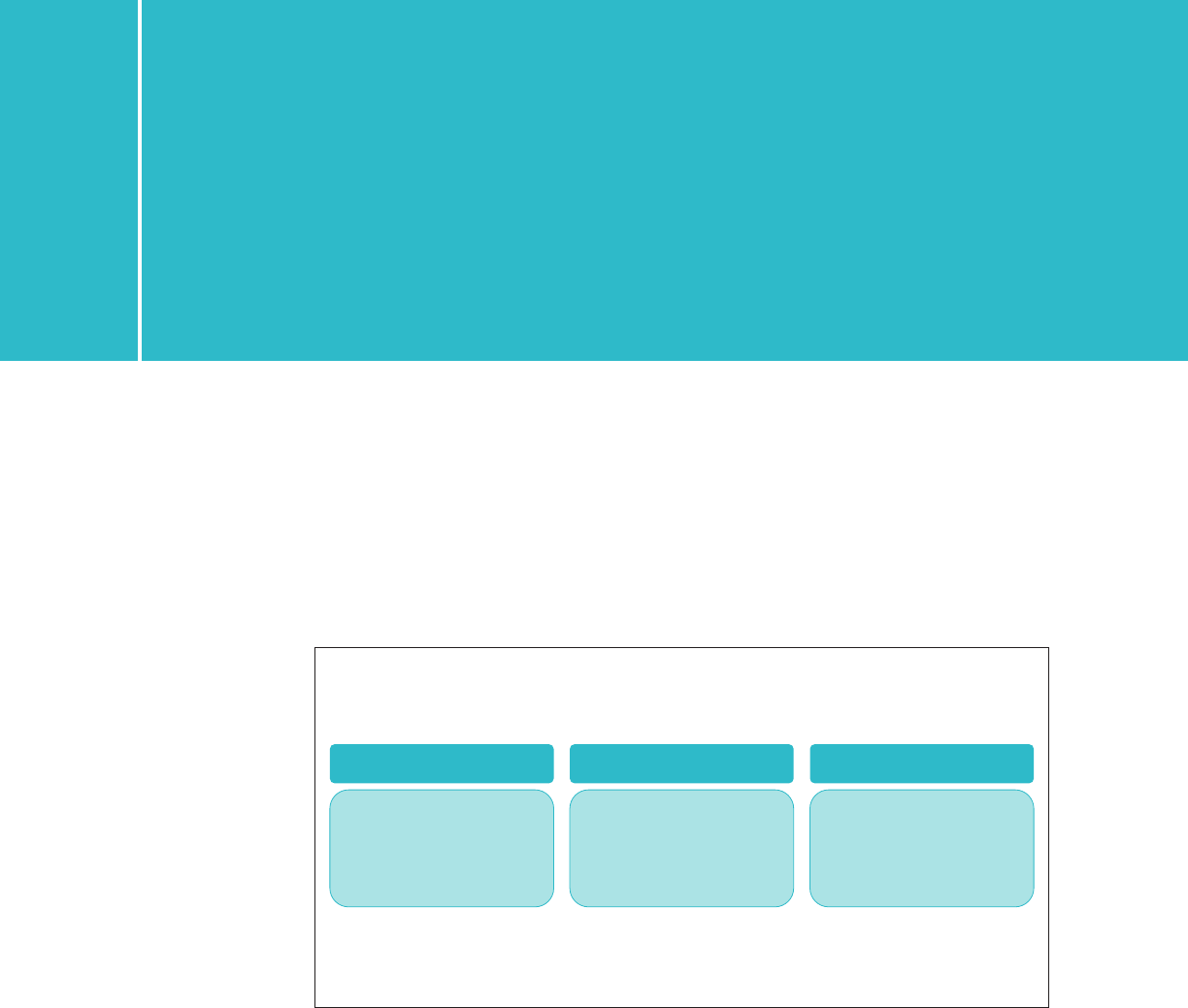

ased on the previous section, the main options for financial inverventions can be

summarized as shown in Figure . It is proposed to establish three funding

instruments/sub-funds under the ERF to address the specific barriers. In this

chapter, the pros and cons of the main options, as listed under each sub-fund, are

evaluated, and recommendations for preferred instrument(s) for each sub-fund will be

proposed.

A. Viability Gap Funding

. Option Viability Gap Funding : Fixed Tari

Pros:

• successful in initially establishing renewable energy markets “from scratch” in many

countries

• incentivizes investors and lenders by securing long-term stable cash flow as long as

the perceived technology risk is low, i.e., the technology is considered proven

• incentivizes project development by providing predetermined tari level and

eligibility criteria for developers; developers know already in project development

stage that their project will be eligible for the tari, which will also make it easier

to secure financing, if they are able to carry out the needed studies and obtain the

needed land-use rights, permits, licenses, and agreements

• usually simple, transparent, and clear

Figure 4: Proposed Three Types of Financial Interventions,

and Potential Solutions for Each

PPA power purchase agreement.

Source: ADB.

Viability Gap Funding

1. Fixed tariff

2. Fixed premium

3. Competitive auction of PPAs

(i.e., tariff)

4. Competitive auction of premium

5. Investment grant

Project Development Funding

1. Technical assistance and

capacity building

2. Project development grants

3. Project development risk finance

Credit Enhancement for

Investments

1. Guarantee

2. Onlending/credit line

3. Colending

4. Stand-alone debt fund

5. Interest rate subsidy

6. Technical assistance and

capacity building

V. Evaluation and Recommendations

on Financing Instruments

for Identified Financial

Intervention Needs

Evaluation and Recommendations on Financing Instruments for Identified Financial Intervention Needs

17

Cons:

• setting taris is challenging; the political process often results in unoptimal level

• too low tari will not encourage project development and investment, and can

put the sector in a standstill

• too high tari overstimulates the sector, leading both to high cost for the

government in the form of excessive taris, encouraging implementation

of projects in unoptimal locations as projects can be profitable even in low-

resource locations, and possibly leading to bottlenecks in supply chains and

increase of development and implementation costs

• political risk related to tari levels and their stability in future can be

questionable, especially if the energy or fiscal policies are unstable more

generally

• dicult to take into account the development of the cost-competitiveness

of technologies; sometimes an annual percentage reduction of taris for new

projects is applied, but this cannot be accurately matched with the actual cost

development of technologies

• would be a parallel and duplicate procedure for the current regulations in

Indonesia, not complementing the existing ones

. Option Viability Gap Funding : Fixed Premium

Pros:

• may be less distorting in a competitive or liberalized electricity market where

prices fluctuate based on demand and supply, and where the generators have

market price risk

• may be better than fixed tari for the renewable energy sector in the long-term

by incentivizing the renewable energy generators in market integration (both

in terms of managing potential price risk as well as technical power system

integration)

• makes the subsidy component in power pricing more transparent

• provides investors and lenders with higher revenues, but same market risk as for

other forms of generation

• incentivizes project development by providing preset eligibility criteria for

developers; developers know already in project development stage that their

project will be eligible for the tari, which will also make it easier to secure

financing, if they are just able to get the needed land-use rights, permits, and

licenses

• usually simple, transparent, and clear

• can work as a complementary mechanism to an existing market or revenue

mechanism

Cons:

• compared with fixed taris, riskier for investors and lenders in markets where

underlying market prices tend to fluctuate, leading to higher cost of capital, and

sometimes even non-bankability of the projects because of too high expected

cash flow volatility

Renewable Energy Financing Schemes for Indonesia

18

• in markets with price risk, leads to higher required subsidy, especially as

renewable energy-based power generation is generally more capital intensive

than conventional power generation

• setting taris is challenging; the political process often results in nonoptimal

level

• too low tari will not encourage project development and investment, and can

put the sector into a halt

• too high tari overstimulates the sector, leading both to high cost for the

government in form of excessive taris, and encourages implementation of

projects in nonoptimal locations as projects can be profitable even in low-

resource locations

• political risk related to tari levels and their stability in the future can be

questionable, especially if the energy or fiscal policies are unstable more

generally

• dicult to take into account the development of the cost-competitiveness

of technologies; sometimes a fixed percentage reduction of taris for new

projects is applied, but this cannot match with the actual cost development of

technologies

• if the price setting procedures (through PPAs or fixed taris) are intransparent

and speculative, the combination with a premium can cause unnecessary

subvention; i.e., taris are negotiated lower by the o-taker than in the base

case, in anticipation of higher premium or subsidy provided by the government

or VGF

• in practice, has not be very widely used compared with fixed taris

. Option Viability Gap Funding : Competitive Auction of Power

Purchase Agreements

Pros:

• provides the investors and lenders with long-term cash flow certainty in the

same way as fixed tari scheme, therefore lowering the cost of capital and

improving the bankability of projects

• after some unsuccessful and nonoptimal implementations in s (such

as in the United Kingdom), and after the “golden age of feed-in taris”

in –, competitive auctions of PPAs have been implemented

increasingly successfully in increasing number of countries to promote

renewable energy investments within this decade; a vast amount of good

practices and success stories is available to be learned and applied

• many renewable energy developers, investors, and lenders are already

knowledgeable and experienced in PPA auction systems and can participate

routinely

• leads to more ecient price setting than fixed taris by compelling the

developers and investors to reveal their true competitive price level

• tracks automatically the changes in cost-competitiveness of renewable

energy technologies; a competitive setting prices of subsequent auctions are

adjusted by the bidders to take into account lowered investment costs, higher

productivity, and lower cost of capital of renewable energy technologies as they

develop further

Evaluation and Recommendations on Financing Instruments for Identified Financial Intervention Needs

19

• allocates resources more eciently; projects in better locations and with better

designs will be more competitive than those less professionally developed and

located in less-attractive areas

• better government control than in fixed tari and premium: it is possible

to define a maximum price to cap the cost of the scheme, and possible for

government to control the volume by capping the capacity to be contracted at

a time and during a specified period

Cons:

• riskier for project developers and, therefore, does not provide as strong

incentive for project development as fixed taris (or premium) since there is

no similar certainty of cash flow as in these schemes. The developer or sponsor

needs to compete against other market players.

• requires more market and renewable energy sector understanding from the

regulator and the government in order to design a good scheme than fixed tari

and premium schemes

• requires more resources to plan, implement, and monitor the system than fixed

tari and premium schemes

• risk of opportunistic behavior; if the sanctions of nondelivery or delays are low

or do not exist at all, can lead to extremely low pricing and unviable projects,

which will finally not be implemented (as what happened in the United

Kingdom’s Non-Fossil Fuel Obligation scheme in s)

• even appropriate sanctions in some countries have led to such a high level

of competition and aggressive pricing that policy makers and regulators have

become concerned about the viability of winning projects

• the bankability of a competitive auction system depends largely on the

creditworthiness of the o-taker and the bankability of the PPA; if one of these

are inadequate, some form of external support is required

• as a separate viability gap funding measure, duplicates the existing regulations

and solicitation procedures instead of complementing them

. Option Viability Gap Funding : Competitive Auction of Premium

Pros:

• similar to competitive auctioning of PPAs regarding ecient price setting,

adapting to cost changes, governance requirements, and government control

• similar to fixed premium schemes regarding the market integration especially

in more liberalized, open, and competitive electricity markets with fluctuating

prices, and regarding making the subsidy component more transparent

• can work in context where the expected price level is higher than the prevailing

market price or general tari level, therefore complementing rather duplicating

existing PPA solicitation and negotiation procedures

• if the price setting procedures (through PPAs or fixed taris) are intransparent

and speculative, the combination with a premium can cause unnecessary

subvention; i.e., taris are negotiated lower by the o-taker than in the base

case, in anticipation of higher premium or subsidy provided by the government

or a viability gap scheme

Renewable Energy Financing Schemes for Indonesia

20

Cons:

• much less used than competitive auctions of PPAs, therefore less experiences

and lessons from schemes in other countries; however, examples can be found

in Finland, Uganda, and Zambia

• not suitable in cases where renewable energy is expected to be cheaper than

the prevailing market price or general tari; in such case, the auction should

lead to winning contracts at zero premium requested, unless negative premium

is allowed. In order to materialize the cost-competitiveness of renewable

energy, the scheme should be based on PPA auction (enabling bids lower than

the market price/regulated tari)

. Option Viability Gap Funding : Investment Grant

Pros:

• from investor perspective, lower risk; allocates more risk from investors to

the government or VGF since all cash is received upfront before the actual

generation takes place, while the other schemes are more results based, i.e.,

rewarding according to the actual generation

• helps in financial arrangements directly and decreases the absolute amount

of financing required as the funds are made available at the time of initial

investment or construction stage already, whereas the other schemes support

the financial arrangements of initial investment only indirectly

• in theory, if the government or VGF’s cost of capital (and, therefore, discount

factor applied) is lower than that of investor, investment grant would be

cheaper for the former, and more valuable for the latter; lower total amount of

subsidy would be required

• simple scheme from governance point of view

• vast amount of experiences and lessons from other countries

• typical instrument when supporting the demonstration and commercialization

of new technologies

• can complement existing PPA solicitation procedures and other prevailing

price setting mechanisms, rather than duplicating them and creating a parallel

market.

Cons:

• upfront funding transfers risk from investor to government or viability gap

scheme; less of a problem for proven low operational expenditure technologies

such as solar, wind, and hydro, which will most likely maximize their generation

in all scenarios, but can be an issue in case of bioenergy projects where

generation could be lower than expected (or project totally terminated)

because of high cost of unavailability of biofuel, or biofuel could be replaced by

fossil fuels

• requires substantial upfront disbursements from the government or VGF in a

relatively shorter term than in the other schemes where the cost acculumates

over longer term; could be an issue from the budgeting perspective

• although the funds are disbursed faster, rules and monitoring of

implementation must be in place also afterwards to ensure that the projects are

implemented and operated according to the initial eligibility criteria

Evaluation and Recommendations on Financing Instruments for Identified Financial Intervention Needs

21

• if the price setting procedures (through PPAs or fixed taris) are intransparent

and speculative, the combination with investment grant can cause unnecessary

subvention; i.e., taris are negotiated lower by the o-taker than in the base

case, in anticipation of higher grant/subsidy provided by the government/VGF

. Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations

Currently, the revenues of renewable energy investments are based on a predefined

tari structure that, on the other hand, in many cases, is negotiable and therefore

uncertain, and with a cap that in many cases is too low for investors to generate

sucient returns. On the other hand, in some locations, the tari levels could be

sucient to justify an investment. The electricity market is noncompetitive, primarily

a single-buyer market, where market-based (supply and demand balance) price

fluctuations do not exist.

As there is no competitive electricity market and related price risk, market integration

(or avoidance of distortion) is not as important as in countries with liberalized and

competitive electricity market. Also, as long as the underlying power price (through

PPA or concession taris) is not predefined, there is a risk that a premium (either

fixed or competitive) or an investment grant can lead to “game-playing” where

unnecessarily low taris/PPA prices emerge, with the anticipation of a viability

gap funding scheme to cover larger part of the revenues of projects. Therefore,

the scheme should be such that it gives the developers an incentive to always

maximize the tari in the PPA or other primary revenue streams determined in PPA

negotiations (IPP scheme), concession taris (electrification scheme), or other.

Based on the fact-finding mission, currently it seems not possible to propose changes

to the current PPA or concession procedures, and therefore a PPA or a fixed tari

scheme would need to be separate from the current procedures, and therefore

would create a parallel market, which is not feasible. Probably, it would also require

regulatory changes. Therefore, only way forward would be to work on the basis of the

current PPAs and concessions and create a VGF mechanism (see Box ) that would

complement rather than duplicate/circumvent the current system. In practice, PPA

auctions or fixed taris are not an option, and the remaining options are premium

(fixed or auctioned) and investment grant.

Production-based premium or investment grant on top of the primary revenue stream

would make the subsidy element more transparent for the government and funders of

the VGF. Such scheme could be justified if the underlying power price was suciently

transparent, and not aected by anticipated existence of a subsidy scheme. Also, it

would be able to work independently from the current PPA or concession procedures

by PLN and the government, complementing them instead of intervening them or

creating a duplicate/parallel procedure.

Further, in some locations, if it is likely that some project types would be competitive

against/cheaper than prevailing tari levels, in some cases a premium should result to

zero, and in fact theoretically be negative in order to materialize the cost-eciency of

renewable energy in best locations. Therefore, since the tari levels and profitabilities

Renewable Energy Financing Schemes for Indonesia

22

between renewable energy projects can be expected to vary considerably, seeking to

establish an ecient and competitive price premium for renewable energy projects

would be reasonable. Projects that have a signed PPA, concession, or similar revenue

stream will be able to calculate the lowest additional premium level they would need

to make their projects profitable. Therefore, such projects could bid for premiums in a

competitive process.

B. Project Development Funding

. Option Project Development Funding : Technical Assistance and

Capacity Building

Pros:

• The provider of the technical assistance and capacity building, such as the PDF

in this case, has more control on the procurement and provision of the services.

For example, it is possible to have a list of accredited service providers from

which project developers can select, or the PDF can use competitive process to

select suitable service providers.

Box 1: Recommendation for the Viability Gap Fund Window of the

Energy Resilience Fund

Based on the aforementioned considerations, it is proposed that competitive

auctioning of premium payments would be selected for the main instrument of the

viability gap funding, being available for projects that already have secured a clear

and fixed revenue stream.

This secured, clear, and fixed revenue stream can mean power purchase agreements

signed by developers under the independent power producer or IPP scheme, or

developers with a concession and explicit power price under the electrification

scheme. This would give the project developers an incentive to negotiate power

purchase agreements or PPAs (or other revenue streams) as high as possible,

therefore enabling competitiveness in a subsequent (possible) competitive bidding

of a premium tari. Such scheme would also not require formal changes or linking to

the existing regulations and power purchase agreement solicitation procedures, but

would complement them and work independently in the current context.

The auction could either aim at maximal cost-eciency, having all projects bidding

in same process, or, for example, there could be location-specific priorities (or

prioritization of certain technologies). In the latter case, the auctioned volume

would be allocated separately for dierent areas (or technologies), depending on

which areas (or technologies) are prioritized for new generation capacity. This could

lead to very dierent price levels in dierent regions (or technologies).

When considering splitting the total allocation, the level of competition needs to

be carefully evaluated. For example, if there are very few eligible bidders in a certain

region, it may not enable sucient competition between bidders.

Source: ADB.

Evaluation and Recommendations on Financing Instruments for Identified Financial Intervention Needs

23

• The scope and costs of the technical assistance and capacity building, and

therefore the budget of the PDF, can be known and planned better beforehand.

• The fund manager can be able to use/direct the use of funds more strategically

from the sector point of view as a whole, therefore aiming at broader benefits

than just project level support.

Cons:

• The procedure may not be flexible enough from the project developers’ point of

view, if they are not able to procure the services they need by themselves, from

wherever they want. The eligible service providers might not include exactly the

type of expertise as required by a developer from time to time.

• Timing of the services may not go exactly as wished by the developer, if the

fund manager is actively involved, which may be an issue since timing can be

critical in project development.

• May require deeper involvement and, therefore, resources from the fund

manager to coordinate and manage the technical assistance/capacity building

and can therefore also lead to delays and bottlenecks.

• In practice, this is grant funding, i.e., once the service provider has been paid for

services, the money is used and lost from the PDF perspective.

. Option Project Development Funding : Project Development Grants

Pros:

• Providing grants is relatively straightforward, and project evaluation, award, and

disbursements can be done eciently, enabling higher volume.

• Possibility to standardize the process (e.g., web-based online procedures,

standard nonnegotiable agreements) can also make it easier for developers to

apply funding

• It can be possible to arrange eciently – calls for proposals per annum with

several projects approved per call, resulting in a large number of approved

grants per annum.

• Grant funding is attractive to developers and sponsors for obvious reasons;

no repayment obligations, no risk of default, and larger impact on profitability

compared with financial instruments.

• For the above reasons, grant financing does not only improve the bankability

of the project or equity IRR but, unlike financial instruments, grant funding

improves the underlying project IRR.

• Usually, grant funding is flexible also from the developers’ point of view. They

can procure services freely from capable service provider they want and when

needed, as long as rules are met (such as procurement rules imposed by the

ERF).

Cons:

• Compared with financial instruments/risk finance, where there is possibility for

repayment and even returns, grants are inecient from the ERF’s perspective

since, once used, the money is used and lost, with no option to reinvest, which

can lower the eectiveness and leverage eect of grants compared with

financial instruments.

Renewable Energy Financing Schemes for Indonesia

24

• When using grants in a context where, at least, some private finance can be

available, there is a risk of market distortion, over-subsidizing, and crowding

out of private finance. Therefore, project award should be done carefully in this

sense, but is challenging in practice.

• Grant funding usually does not require as much from developers than risk

finance. In the latter case, the evaluation, comments, and requirements are

often tougher, thus often also improving the overall quality of the project. In

some cases, it could be argued that grant funding has been “too lazy money.”

. Option Project Development Funding : Project Development Risk Finance

Pros:

• Risk finance (meaning in practice equity, quasi-equity, or mezzanine loans)

can be more ecient from a broader perspective, i.e., be able to leverage more

other finance, including private finance. Once a project development stage

mezzanine loan is being repaid with interest (either in installments or at the

financial close of the project) the funds can be reinvested in a new project. This

can make the use of public funds more ecient.

• Depending on the risk profile/strategy of the PDF, it can aim at

o taking a lot of risk, thereby losing its capital gradually, but being able to

recover and reinvest some of its funds more than once;

o aiming at self-suciency and cost-neutrality, i.e., the returns will cover its

operating costs and losses, and the capital will be preserved in the long term; or

o being close to a commercial financial investor, pricing its financing to

account for high risk and high administrative costs of the fund, and aiming at

generating positive post-fees net returns.

• Risk finance can and needs to be tailored for the purpose, meaning that the

project development status, available funding, expected schedule, and risks

can be taken into account to structure the project development funding in the

most meaningful way for the project. This will not only serve the interests of the

project and the PDF, but can also help mobilize other finance, including private

investors.

• Use of financial instrument can be less market-distorting than use of grants.

Financial instruments can and should also be tailored from the financial market

situation perspective too, meaning that, in more commercial cases, where

private finance may also be involved, also the project development funding

should apply more commercial features to avoid crowding-out eect, whereas

in financially less-viable projects, where private funding is very unlikely, the

project development funding can take softer forms.

• When investing in form of a financial instrument (in contrast to grants), there

are often stricter due diligence process, stricter agreements, requirements,

covenants, and other control mechanisms in place for the financier (i.e., PDF

in this case). Although this may be seen critically by the project developer, it

can improve the quality of the project and project development, and forces the

developer to be clear, transparent, and professional in their procurement, use of

money, and documentation.

Evaluation and Recommendations on Financing Instruments for Identified Financial Intervention Needs

25

Cons:

• Since investing in form of financial instrument(s) requires more tailoring and

structuring, the transaction costs tend to be higher than in grant facilities, and

respectively the volume of funded projects may be lower than in case of a grant

facility. In contrast, this may reduce the eectiveness and leverage of the PDF.

• If project development funding provided by PDF is repayable (possibly with

interest), the cash flow to repay the project development funding is away from

cash flow for other purposes. Therefore, compared with grants or technical

assistance, it inevitably reduces the project IRR and equity IRR of the project,

and it also aects negatively certain debt-related ratios such as debt service

coverage ratio, meaning that the borrowing capacity of the project is reduced

respectively. However, project development funding, and especially PDF’s likely

minor share of it, is typically small compared with the investment cost of the

project itself. Therefore, in many cases, this impact is not remarkable, but needs

to be addressed, however.

• Managing the financial investments requires more eort than monitoring

of the use of disbursed grants. Especially, equity can be burdensome since

(i) the shareholder role and possible board membership brings additional

responsibilities in decision-making; and (ii) the exit of the equity investment

needs to be separately planned and executed (in contrast to repayment of a

loan), which can turn out to be very dicult or even impossible. Also managing

a loan portfolio requires careful monitoring that debt servicing of projects

happens as in loan agreements, but as long as there are no defaults of other

special events, the debtor does not need to be involved with the portfolio

companies, and in fact has no access to decision-making.

. Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations

Traditionally, the project development funding support has been based on technical

assistance and grant funding, which are attractive for the developers as well as

straightforward, easy, and cost-ecient to manage. On the other hand, grant funding

may be an inecient use of public funds in cases where there is a business case, and

therefore does not achieve as high as possible leverage eect since, once money is

used, it is lost from the funders’ point of view. In the worst case, such grant finance

may crowd out private commercial finance that would be available but will not be

used since developers prefer “free and easy money” from grant facilities. Recently, an

increasing amount of more market-based approaches and financial instruments have

been used. However, even in one country and within one category of projects, there

will be a lot of variation between individual projects, some being better able to absorb

funding at commercial terms, while some will still require clearly subsidized funding.

Therefore, it may be advisable for the PDF to seek commercial financing options to

promote project development activities, while also preserve the option to provide

softer grant financing in cases where the projects’ capability to absorb commercial

finance is more limited. From instrumentation/structuring point of view, both grants

and financial instruments can be structured in a more or less commercial way.

For example, the PDF could be formally a grant facility, but to the extent possible

Renewable Energy Financing Schemes for Indonesia

26

distribute “reimbursable grants,” possibly carrying an interest, meaning that, in case

the project is successful, it would repay the grant, possibly with an interest/multiple,

at the financial close, or the grant could be converted to a short-term loan, repayable

during the operational phase from project cash flows. In this case, even if the funding

was legally a grant, it would be structured as risk finance such as mezzanine loan/

quasi-equity. Alternatively, the PDF could provide grants and risk financing. The

practical dierence between these could eventually be limited, depending much on

the detailed legal specifications of these (see Box ).

This approach would enable more sophisticated tailoring opportunities on the project

level funding. It would also lead to additional management resource requirements for

the PDF. In such case, in contrast to more traditional grant finance, the PDF should

have more personnel resources, including people with specific expertise in project

development and financial structuring. This would both increase the transaction

costs and reduce the volume of projects that can be taken through the PDF on an

annual basis.

Therefore, the choice and detailed specifications of the PDF instrument depend

greatly on the volume and timing targets of the ERF. If the size and volume targets of

the ERF are large, it may be more ecient to (at least partly) formulate the PDF as a

grant facility, possibly based on frequent online call for proposals (CfP) procedure. To

the extent the volume targets of the ERF allow, it is recommendable that the PDF at

least consider ways to use financial instruments and aim at higher leverage and less

market distortion.

Bilateral first come, first served approach may be challenging from public funding

point of view, which often prefers/requires competitive procedures such as calls for

proposals. However, the former approach is preferred if financial instruments are

used. The latter does not enable tailored structuring and the needed level of project

evaluation and due diligence as required when using financial instruments. There are