Revised 2024

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

1 Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

American College of Radiology

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

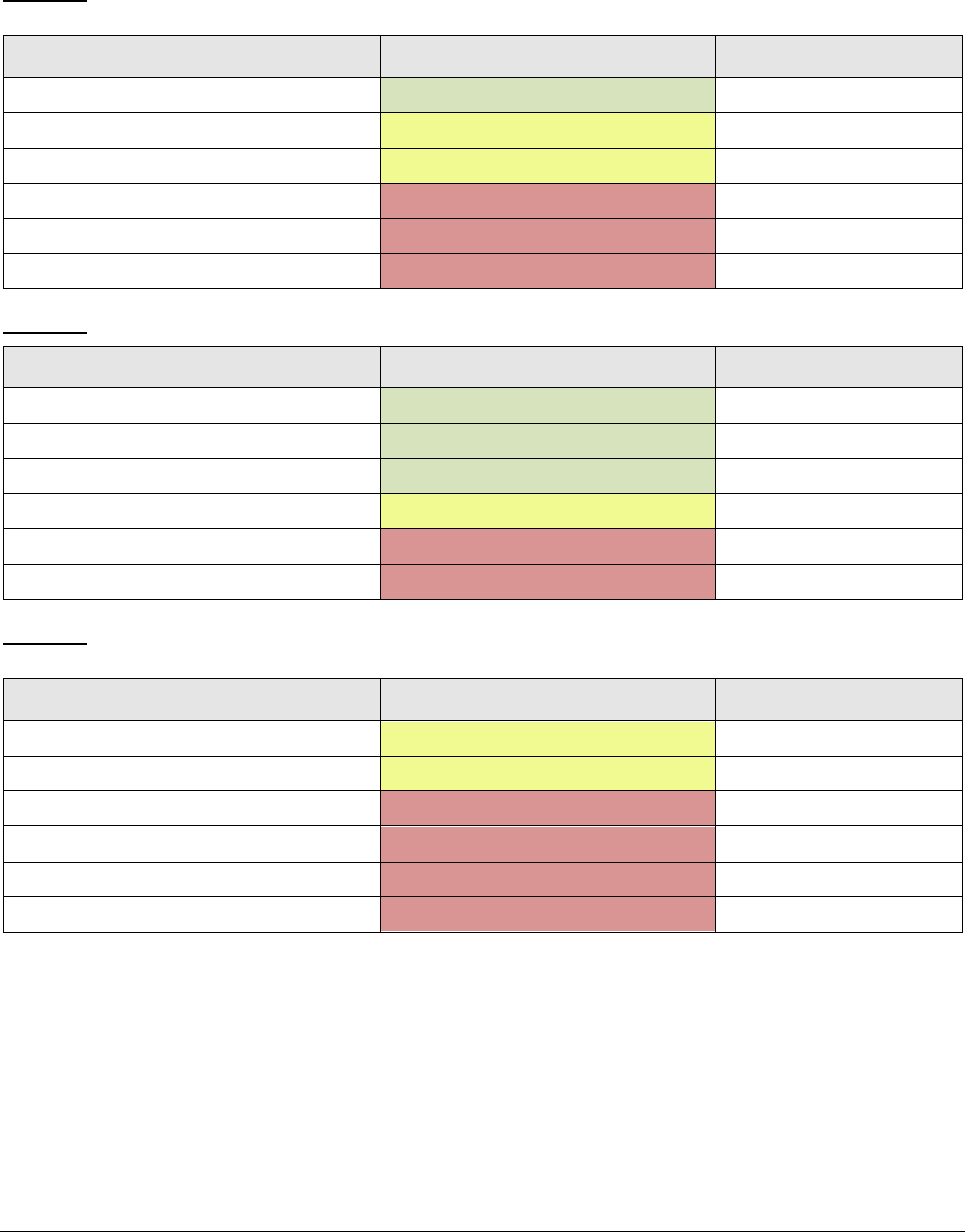

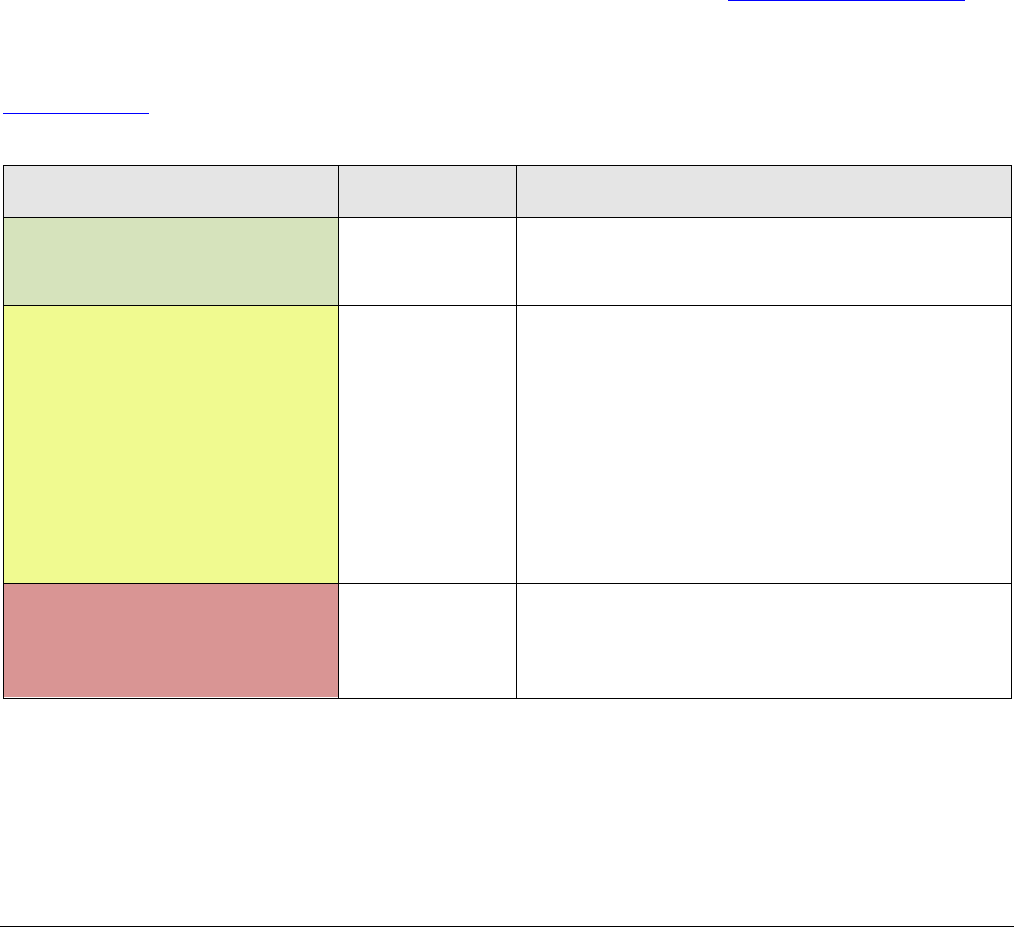

Variant 1: Adult. Altered mental status. Suspected intracranial pathology or focal neurologic deficit.

Initial imaging.

Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level

CT head without IV contrast Usually Appropriate

☢☢☢

MRI head without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate

O

MRI head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate

O

MRI head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

O

CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

☢☢☢

CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

☢☢☢

Variant 2: Adult. Altered mental status with known history of intracranial pathology. Initial imaging.

Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level

MRI head without and with IV contrast Usually Appropriate

O

MRI head without IV contrast Usually Appropriate

O

CT head without IV contrast Usually Appropriate

☢☢☢

CT head with IV contrast May Be Appropriate

☢☢☢

MRI head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

O

CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

☢☢☢

Variant 3: Adult. Altered mental status. Suspected medical illness or toxic-metabolic cause. Initial

imaging.

Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level

MRI head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate

O

CT head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate (Disagreement)

☢☢☢

MRI head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

O

MRI head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

O

CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

☢☢☢

CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

☢☢☢

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

2 Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

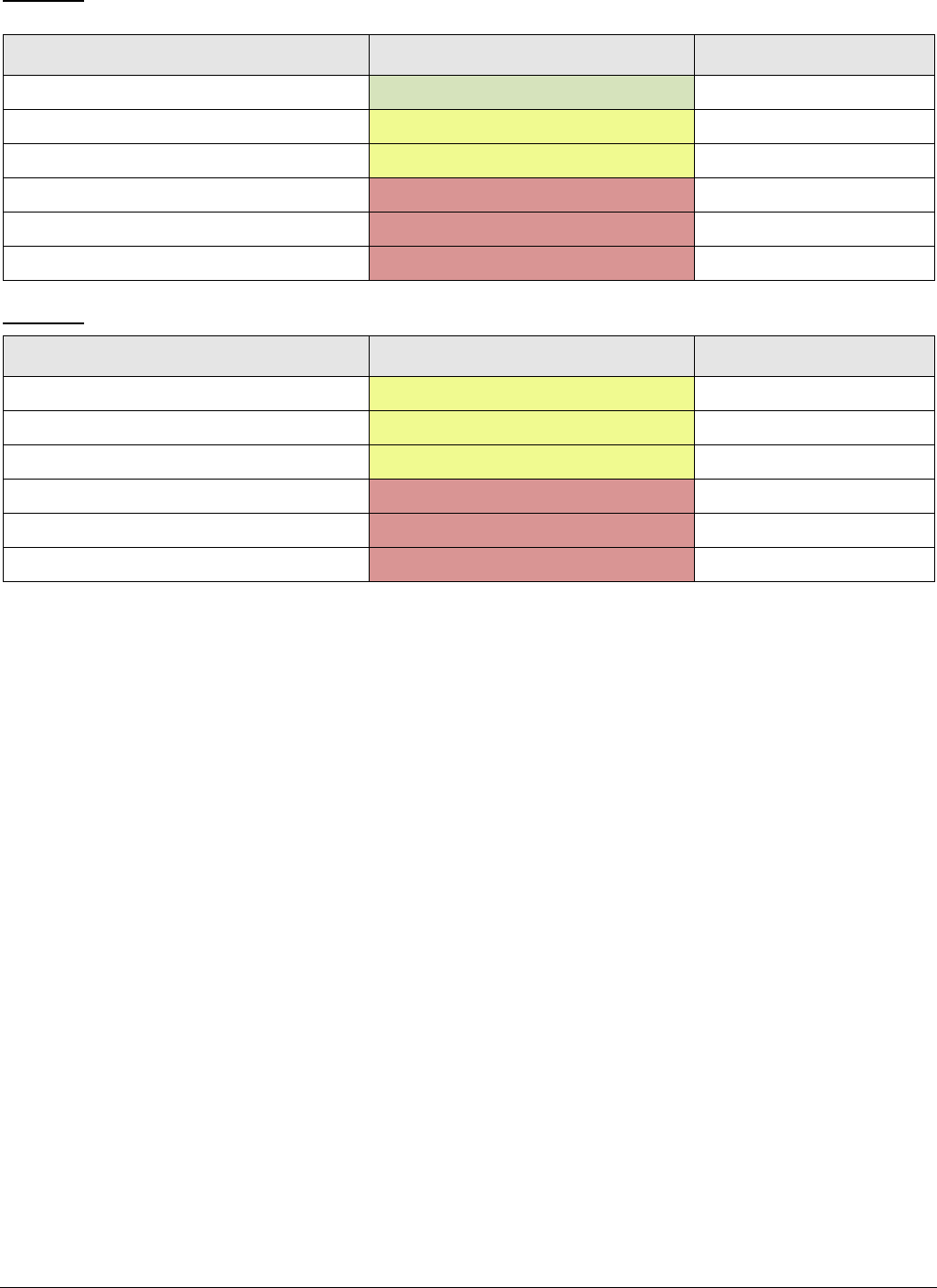

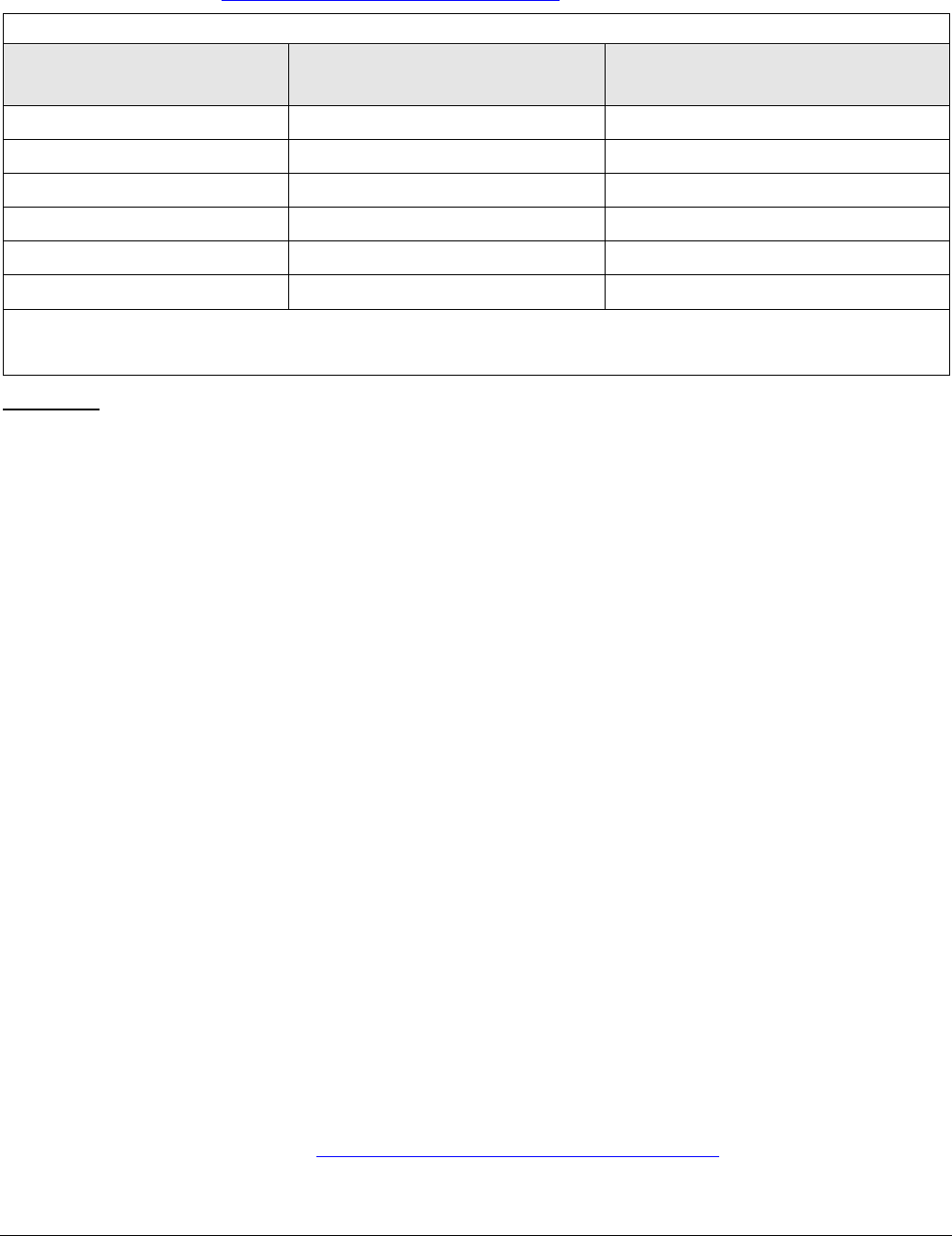

Variant 4: Adult. Altered mental status despite clinical management of known medical illness or toxic-

metabolic cause. Initial imaging.

Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level

CT head without IV contrast Usually Appropriate

☢☢☢

MRI head without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate

O

MRI head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate

O

MRI head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

O

CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

☢☢☢

CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

☢☢☢

Variant 5: Adult. New onset psychosis. Initial imaging.

Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level

MRI head without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate

O

MRI head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate

O

CT head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate

☢☢☢

MRI head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

O

CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

☢☢☢

CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate

☢☢☢

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

3 Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

ALTERED MENTAL STATUS, COMA, DELIRIUM, AND PSYCHOSIS

Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging: Bruno P. Soares, MD

a

; Robert Y. Shih, MD

b

; Pallavi S. Utukuri, MD

c

;

Megan Adamson, MD

d

; Matthew J. Austin, MD

e

; Richard K.J. Brown, MD

f

; Judah Burns, MD

g

;

Kelsey Cacic, MD

h

; Sammy Chu, MD

i

; Cathy Crone, MD

j

; Jana Ivanidze, MD, PhD

k

; Christopher D. Jackson, MD

l

;

Aleks Kalnins, MD, MBA

m

; Christopher A. Potter, MD

n

; Sonja Rosen, MD

o

; Karl A. Soderlund, MD

p

;

Ashesh A. Thaker, MD

q

; Lily L. Wang, MBBS, MPH

r

; Bruno Policeni, MD, MBA.

s

Summary of Literature Review

Introduction/Background

Altered mental status (AMS) and coma are terms used to describe disorders of arousal and content of consciousness.

AMS may account for up to 4% to 10% of chief complaints in the emergency department (ED) setting and is a

common accompanying symptom for other presentations [1,2]. AMS is not a diagnosis but rather a term for

symptoms of acute or chronic disordered mentation [1], including confusion, disorientation, lethargy, drowsiness,

somnolence, unresponsiveness, agitation, altered behavior, inattention, hallucinations, delusions, and psychosis

[3,4]. Some of the most common disorders associated with AMS are underlying medical conditions, substance use,

and mental disorders [5]. Validated assessment scales, such as the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale and Glasgow

Coma Scale, may be employed to objectively quantify the severity of symptoms [3,4]. The cause of AMS in patients

across all age groups remains undiagnosed in slightly >5% of cases. Overall mortality in patients with AMS is

approximately 8.1% and is significantly higher in elderly patients [4].

Two studies found that older patients presenting to the ED with the nonspecific chief complaint of AMS are likely

to have delirium [6]. Delirium is a defined and diagnosable medical condition under Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition, which includes inattention as a cardinal feature, may fluctuate over the

course of day with lucid intervals, and may present with subtle disturbances in consciousness compared with other

forms of acute AMS, making detection more difficult and thus easy to miss [3,6]. Delirium is considered a medical

emergency. Early detection and accurate diagnosis are extremely important because mortality in patients may be

twice as high if the diagnosis of delirium is missed [7]. Up to 10% to 31% of patients may have delirium at

admission, and it may develop in up to 56% of admitted patients [8], particularly following surgery or in the

intensive care unit [8]. Delirium is commonly precipitated by 1 or more underlying cause, including another medical

condition, intoxication, or withdrawal [9]. Management is based on treatment of the underlying cause, control of

symptoms with nonpharmacological approaches, medication when deemed appropriate, and effective aftercare

planning [3,6,10]. The economic impact of delirium in the United States is profound, with total

costs estimated at

$38 to $152 billion each year [11].

New onset psychosis is often listed as a separate subgroup under the AMS category. Delusions and hallucinations

are 2 cardinal features of psychotic symptomatology. Additional symptoms may include disorganized speech or

thought, disorganized or abnormal motor behavior including catatonia or agitation, and negative symptoms such as

diminished expression of emotions [9]. In contrast with other presentations of AMS, awareness and level of

consciousness in patients with psychosis are frequently intact [12]. If the psychotic symptoms are related to an

underlying psychiatric disorder, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or depression

with psychotic features, it is termed primary psychosis. Secondary causes of psychosis are thought to be directly

related to drug/alcohol use, withdrawal, or an underlying medical cause [1,2] and are not better explained by

delirium [9]. Medical conditions that may present with psychotic symptoms include endocrine disorders,

autoimmune diseases, neoplasms and paraneoplastic processes, neurologic disorders, infections, genetic or

a

Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California.

b

Panel Chair, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland.

c

Panel Vice-Chair,

Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York.

d

Clinica Family Health, Lafayette, Colorado; American Academy of Family

Physicians.

e

University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, Virginia.

f

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; Commission on Nuclear Medicine

and Molecular Imaging.

g

Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York.

h

San Antonio Military Medical Center, San Antonio, Texas; American Academy of

Neurology.

i

University of Washington, Seattle, Washington and University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

j

Inova Fairfax

Hospital, Falls Church, Virginia; American Psychiatric Association.

k

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York.

l

The University of Tennessee

Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee; Society of General Internal Medicine.

m

University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

n

Brigham & Women's Hospital,

Boston, Massachusetts; Committee on Emergency Radiology-GSER.

o

Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, California; American Geriatrics Society.

p

Naval Medical

Center Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Virginia.

q

University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado.

r

University of Cincinnati Medical Center,

Cincinnati, Ohio.

s

Specialty Chair, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa.

The American College of Radiology seeks and encourages collaboration with other organizations on the development of the ACR Appropriateness

Criteria through representation of such organizations on expert panels. Participation on the expert panel does not necessarily imply endorsement of the final

document by individual contributors or their respective organization.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

4 Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

metabolic disorders, nutritional deficiencies, and drug-related intoxication, withdrawal, side effects, and toxicity.

For secondary causes of psychosis, treatment is aimed at the underlying medical cause and control of the psychotic

symptoms [12]. Treatment of primary causes of psychosis involves pharmacologic management with antipsychotic

medications, psychological therapy, and psychosocial interventions [13].

This article focuses on the appropriateness of neuroimaging in adult patients presenting with AMS changes

including new onset delirium or new onset psychosis. In these cases, imaging is often expedited for initial

stabilization and to exclude an intracranial process requiring intervention. The diagnosis of delirium in the ED

setting can be missed by inadequate screening [3,14], although ED physicians are moderately accurate at

establishing the correct clinical diagnosis for the cause of AMS within the first 20 minutes of the patient encounter

[15]. The complete evaluation for underlying causes, such as chest radiography to assess for pneumonia,

electrocardiogram to assess for myocardial ischemia, electroencephalography for suspected convulsive or

nonconvulsive seizure, and lumbar puncture to assess for central nervous system infection, is beyond the scope of

this article [3,7].

AMS may be an accompanying feature of clinical presentations more appropriately handled by other ACR

Appropriateness Criteria documents, although overlap is unavoidable. For patients with suspected stroke or focal

neurological deficits also presenting with AMS, please refer to the ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

topic on

“

Cerebrovascular Diseases-Stroke and Stroke-Related Conditions” [16]. If seizure is the suspected cause of AMS,

please refer to the ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

topic on “Seizures and Epilepsy” [17]. For patients presenting

with AMS in the setting of known or suspected trauma, please refer to the ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

topic on

“

Head Trauma” [18]. For patients presenting with headaches and AMS, please refer to the ACR Appropriateness

Criteria

®

topic on “Headache” [19]. Chronic changes in mental status are typically synonymous with dementia,

occur over a time period of months to years, and are covered in the ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

topic on

“

Dementia” [20].

Special Imaging Considerations

Imaging patients with AMS and psychosis can be challenging because of limitations in the patient’s ability to follow

commands and combativeness that is due to longer examination lengths, sensitivity to motion artifact, smaller bore

sizes exacerbating symptoms in anxious or claustrophobic patients, and sounds experienced by the patient during

the examination. MRI may be delayed or unavailable because of the inability to obtain an accurate safety screening

history. Coordination of care with the patient’s managing physician and family members is frequently critical to

successful diagnostic imaging in this patient population [21,22]. To offset challenges in MRI in this patient group,

it may be helpful to tailor examinations for shorter scan times, decrease the number of sequences to answer the

specific clinical question, or use motion-reducing sequences [23].

Initial Imaging Definition

Initial imaging is defined as imaging at the beginning of the care episode for the medical condition defined by the

variant. More than one procedure can be considered usually appropriate in the initial imaging evaluation when:

• There are procedures that are equivalent alternatives (ie, only one procedure will be ordered to

provide the clinical information to effectively manage the patient’s care)

OR

• There are complementary procedures (ie, more than one procedure is ordered as a set or

simultaneously where each procedure provides unique clinical information to effectively manage

the patient’s care).

Discussion of Procedures by Variant

Variant 1: Adult. Altered mental status. Suspected intracranial pathology or focal neurologic deficit. Initial

imaging.

Identifying patients with AMS or delirium secondary to acute intracranial pathology is extremely important to guide

management and ensure early appropriate triage. This variant encompasses a select group of patients presenting

with acute mental status changes at a relatively higher risk of acute intracranial pathology.

The yield of neuroimaging studies in patients with AMS is low. A recent meta-analysis of 25 studies including a

total of 79,201 patients with atraumatic AMS showed that 94% had undergone a head CT examination, with relevant

abnormal findings in only 11% [24]. In a large study of more than 708,145 adult ED encounters, 58,783 CT head

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

5 Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

examinations were ordered, with an overall critical result yield of 8.0%. CT head examinations performed for a

complaint of AMS had a yield of 9.8% [25]. A study of 285 febrile elderly patients with AMS showed abnormal

brain imaging in 16.5%. The most common neurological diagnoses in patients admitted to the ED were intracranial

hemorrhage (ICH) and ischemic stroke [26]. Lower Glasgow Coma Scale, the presence of lateralizing sign, higher

systolic blood pressure, and lower body temperature were significantly associated with abnormal brain imaging in

febrile elderly patients with AMS [26].

The prevalence of delirium in the ED ranges from 7% to 35%. Four factors with strong associations with ED

delirium are nursing home residence, cognitive impairment, hearing impairment, and a history of stroke [27]. There

are a wide range of precipitating factors leading to delirium onset that make evaluation challenging, some of which

are life threatening. These may be related to systemic disease, such as sepsis or infection, hypoxia, metabolic

derangements, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, hyponatremia, hypothermia, acute myocardial infarction, neurologic

disease including stroke, ICH, Wernicke encephalopathy (thiamine deficiency), central nervous system infection,

seizure, surgery, trauma, drugs such as anticholinergic drugs, sedatives, narcotics, drug or alcohol withdrawal,

polypharmacy, environmental factors from restraints, stress or pain, and sleep deprivation. There is relatively little

evidence in the literature regarding appropriate use of neuroimaging with new onset delirium.

For patients who present with AMS or delirium and with suspicion for acute stroke, focal neurologic deficit, seizure,

head trauma, or headache, reference should be made to the respective ACR Appropriateness Criteria as appropriate:

the ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

topics on “Cerebrovascular Diseases-Stroke and Stroke-Related Conditions”

[16], “Seizures and Epilepsy” [17], “Head Trauma” [18], or “Headache” [19] for further guidance.

CT Head With IV Contrast

A common practice is to perform a noncontrast screening head CT followed by a more sensitive MRI brain

examination performed with and without IV contrast in the setting of AMS. In the setting of AMS, contrast-

enhanced CT examinations can be considered if intracranial infection, tumor, or inflammatory pathologies are

suspected. However, the use of contrast-enhanced head CTs as a first-line test in the acute setting does not add

significant value over noncontrast head CT examinations [28].

CT Head Without and With IV Contrast

A common practice is to perform a noncontrast screening head CT followed by a more sensitive MRI brain

examination performed with and without intravenous (IV) contrast in the setting of AMS. There is no relevant

literature to support the use of CT head without and with IV contrast in the initial imaging of this clinical scenario.

CT Head Without IV Contrast

Unless the etiology is clear and the risk of intracranial pathology is low, neuroimaging should be included in the

initial assessment of recent AMS. A noncontrast head CT is the first-line neuroimaging test of choice in this setting

and can be performed safely and rapidly in all patients [2]. Yield of acute contributory findings on CT ranged from

2% to 45% based on trial design and inclusion or exclusion criteria [2,29-33]. Subgroup analysis of patients with

AMS and no focal deficits in 1 study noted acute changes on imaging in 7.4% of patients [30]. Risk factors

associated with intracranial findings included history of trauma or falls, hypertension, anticoagulant use, headache,

nausea or vomiting, older age, impaired consciousness or unresponsiveness, neurologic deficit, and history of

malignancy [2,29-33]. However, different studies found variable levels of significance of these associations. Risk

stratification tools have been proposed to maintain sensitivity while reducing CT utilization [29]; however, they

have not been prospectively validated. Therefore, determination of the need and benefit of brain imaging in this

scenario falls on the evaluating clinician’s judgement.

The reported detection of treatment-altering findings on head CT is very low in elderly patients with new onset

delirium unless 1 of the following risk factors is present: focal neurologic deficit, history of recent falls or head

injury, anticoagulation therapy, signs of elevated intracranial pressure, or significant deterioration of consciousness

[8,38-40]. Acute pathology that resulted in a change of management was detected in a small proportion of patients

on head CT, including ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH),

encephalitis or meningitis, and cerebral tumors. Therefore, the low diagnostic yield of CT in this setting must be

weighed against the risk of possible, preventable morbidity [8,10], acknowledging that patients may not have

clinical signs on examination that predict a focal pathology [34].

MRI Head With IV Contrast

There is no relevant literature to support the use of MRI head performed only with IV contrast in this clinical

scenario.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

6 Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

MRI Head Without and With IV Contrast

MRI examinations without and with IV contrast may be performed if intracranial infection, tumor, inflammatory

lesions, or vascular pathologies are suspected.

In patients with delirium, brain MRI without and with IV contrast may be helpful for the definitive characterization

of a focal lesion identified on initial noncontrast CT or in patients with known cancer history [10].

MRI Head Without IV Contrast

MRI may prove useful in the setting of AMS as a second-line test when occult pathology is suspected and initial

head CTs are unrevealing, because of MRI’s higher sensitivity in detecting ischemia, encephalitis, or subtle cases

of SAH [29,35,36].

In a simulated decision-making study using a prospective intensive care unit cohort, a panel of neurocritical experts

first reviewed clinical information (without MRI) from 75 patients with acute disorder of consciousness patients

and made decisions about diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Review of head MRI examinations led to changes

in clinical management of 76% of patients including revised diagnoses in 20%, revised levels of care in 21%,

improved diagnostic confidence in 43%, and improved prognostications in 33% [37]. However, decisions were

revised more often with stroke (which commonly presents with focal neurological deficits) than with other brain

injuries.

Many of the abnormal findings in the literature for this topic included small ischemic infarcts [29,35,36]. Notably,

a retrospective study found that 70% of patients who had a missed ischemic stroke diagnosis presented with AMS

[33]. MRI of the brain is complementary to an abnormal head CT for the evaluation of suspected intracranial mass

lesions, intracranial infection, nonspecific regions of edema, ischemia, and cases of ICH when an underlying lesion

is suspected [38]. MRI may also be considered as a first-line test in certain situations, such as a clinically stable

patient with known malignancy, HIV, or endocarditis.

Noncontrast MRI examinations of the brain are usually sufficient in the assessment of intracranial complications

related to hypertensive emergency, including posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

In patients with new onset delirium, the reported yield of brain MRI is very low in the absence of a focal neurologic

deficit or history of recent falls. In a small proportion of patients, brain MRI did reveal acute pathology possibly

accounting for delirium, including ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, subdural hematoma, SAH, septic emboli,

encephalitis, meningitis, cerebral metastases, primary brain tumor, pineal tumor, and a large meningioma [34]. MRI

may be helpful for further evaluation of an abnormality detected on noncontrast CT in the workup of new onset

delirium, such as space-occupying lesions or infection.

Variant 2: Adult. Altered mental status with known history of intracranial pathology. Initial imaging.

For patients who present with suspected stroke, focal neurologic deficit, seizure, head trauma, or headache,

reference should be made to the respective ACR Appropriateness Criteria as appropriate: the ACR Appropriateness

Criteria

®

topics on “Cerebrovascular Diseases-Stroke and Stroke-Related Conditions” [16], “Seizures and

Epilepsy” [17], “Head Trauma” [18], or “Headache” [19] for further guidance.

CT Head With IV Contrast

Contrast-enhanced CT examinations may be considered if clinical concern exists for progression of intracranial

infection, such as abscesses or empyema, tumor, or inflammatory conditions. Advantages of CT are fast

examination times and less susceptibility to motion artifact compared with MRI. Disadvantages of CT include less

sensitivity in detection of acute ischemia and enhancement compared with MRI [30]. Overall, MRI is considered

superior in this clinical scenario.

CT Head Without and With IV Contrast

A common practice is to perform a noncontrast screening head CT followed by a more sensitive MRI brain

examination performed with and without IV contrast in the setting of AMS. There is no relevant literature to support

the use of CT head without and with IV contrast in the initial imaging of this clinical scenario.

CT Head Without IV Contrast

CT is the first-line imaging test of choice for evaluating suspected progressive ICH, mass effect, or hydrocephalus

in the emergent setting. Noncontrast head CT examinations are able to depict possible complications of a wide

variety of intracranial pathology, including progressive mass effect, increasing edema, hydrocephalus, new or

enlarging ICH, and progressive ischemia. However, the literature search did not identify any studies regarding the

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

7 Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

use of CT in the evaluation of acute or worsening mental status changes in a patient with known intracranial

pathology.

MRI Head With IV Contrast

There is no relevant literature to support the use of MRI head performed only with IV contrast in this clinical

scenario.

MRI Head Without and With IV Contrast

MRI is the imaging test of choice in the evaluation of suspected progressive inflammatory conditions, such as

multiple sclerosis or neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus. In the assessment of known ICH, MRI is

usually not required unless there is suspicion for an underlying mass or lesion or if axonal shear injury is suspected.

MRI without and with IV contrast may be performed if intracranial infection, tumor, inflammatory lesions, or

vascular pathologies are suspected.

MRI Head Without IV Contrast

MRI is complementary to CT in the evaluation of suspected progression of intracranial mass lesions, infection, and

ischemia and may be performed as a first-line test instead of CT. However, the literature search did not identify any

studies regarding the use of MRI in the evaluation of acute or worsening mental status changes in a patient with

known intracranial pathology.

Advantages of MRI include higher sensitivity for the detection of ischemia, encephalitis, subtle cases of SAH, and

enhancement of pathology compared with CT and the potential to use advanced imaging applications that may

provide critical information, such as diffusion-weighted imaging, MR perfusion, susceptibility-weighted sequences,

and MR spectroscopy. Disadvantages of MRI include longer examination time, susceptibility to motion artifacts,

and implanted devices that are not MRI safe [2].

Variant 3: Adult. Altered mental status. Suspected medical illness or toxic-metabolic cause. Initial imaging.

Acute mental status changes may be triggered by a wide range of medical conditions, including drugs and

intoxication, system or organ dysfunction, and metabolic or endocrine factors. This variant encompasses a subgroup

of patients presenting with acute mental status changes at low risk of acute intracranial pathology.

CT Head With IV Contrast

The literature search did not identify any studies regarding the use of contrast-enhanced CT relevant to this variant,

and contrast-enhanced CT examinations are not performed as a first-line test in this setting.

CT Head Without and With IV Contrast

A common practice is to perform a noncontrast screening head CT followed by a more sensitive MRI brain

examination performed with and without IV contrast in the setting of AMS. There is no relevant literature to support

the use of CT head without and with IV contrast in the initial imaging of this clinical scenario.

CT Head Without IV Contrast

ED physicians are moderately accurate at establishing the correct clinical diagnosis for the cause of AMS within

the first 20 minutes of the patient encounter [15]. A large proportion of misdiagnoses in this study were deemed

insignificant because of confusing various forms of isolated or mixed intoxication. Although CT head may be useful

in this scenario, deferring head CT imaging while observing if intoxicated patients symptomatically improve may

be a safe practice and may prevent the need for imaging in large percentage of intoxicated patients [39].

MRI Head With IV Contrast

There is no relevant literature to support the use of MRI head performed only with IV contrast in this clinical

scenario.

MRI Head Without and With IV Contrast

There is no relevant literature to support the use of MRI head without and with IV contrast in this clinical scenario.

MRI Head Without IV Contrast

There may be unique instances where a brain MRI examination may be useful in confirming a suspected clinical

diagnosis responsible for AMS, such as carbon monoxide poisoning, Wernicke encephalopathy (thiamine

deficiency) [40], drug toxicity including medications (eg, methotrexate, metronidazole) and illegal drug use, central

pontine myelinolysis, or additional metabolic disorders. However, the literature search did not identify any studies

regarding the use of MRI relevant to this variant.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

8 Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

Variant 4: Adult. Altered mental status despite clinical management of known medical illness or toxic-

metabolic cause. Initial imaging.

This is a challenging clinical scenario in which common and treatable causes of AMS have been deemed unlikely,

and a more exhaustive evaluation is required to find the precipitating cause of AMS. Clinical suspicion for a

neurologic cause of AMS may be in an intermediate category.

CT Head With IV Contrast

Contrast-enhanced CT examinations are usually not performed as a first-line test in this setting but may be

considered as a second-line test to assess abnormalities found on the screening head CT and for patients unable or

unwilling to have MRI [28]. Evidence guiding appropriate imaging recommendations in this variant is limited

because most studies in the literature search sampled undifferentiated patient populations with a broad range of risk

factors and are not directly applicable to this variant [2,29,31-33].

CT Head Without and With IV Contrast

A common practice is to perform a noncontrast screening head CT followed by a more sensitive MRI brain

examination performed with and without IV contrast in the setting of AMS. There is no relevant literature to support

the use of CT head without and with IV contrast in the initial imaging of this clinical scenario.

CT Head Without IV Contrast

For patients with AMS not responding to initial management of the suspected underlying medical cause,

neuroimaging with a noncontrast head CT is useful to evaluate for a possible neurological source of their symptoms,

including acute ICH, infarct, brain mass, hydrocephalus, or mass effect. The diagnostic yield may be low in the

absence of a focal neurological deficit or signs of trauma [2,15,30,32,39]. No prospectively validated clinical rule

or scoring system is available to help define which of these patients benefit the most from imaging. Therefore,

determining the clinical need and value of brain imaging in this scenario relies on the evaluating clinician’s

judgement. Unresponsive patients may have higher rates of acute findings on CT [32].

MRI Head With IV Contrast

There is no relevant literature to support the use of MRI head performed only with IV contrast in this clinical

scenario.

MRI Head Without and With IV Contrast

MRI examinations without and with IV contrast may be performed if intracranial infection, tumor, inflammatory

lesions, or vascular pathologies are suspected. However, the literature search did not identify any studies regarding

the use of contrast-enhanced MRI relevant to this variant.

MRI Head Without IV Contrast

MRI may prove useful as a second-line test when occult pathology is suspected and the initial head CT is

unrevealing because of MRI’s higher sensitivity in detecting small infarcts, encephalitis, and subtle cases of SAH

[29,35,36]. MRI of the brain is complementary to CT in further evaluation of suspected intracranial mass lesions,

intracranial infection, and nonspecific regions of edema and in the evaluation of certain cases of ICH for the

presence of an underlying lesion, including a hemorrhagic primary or secondary brain mass, arteriovenous

malformation, or cavernous venous malformation [38,41]. MRI may be considered as a first-line test in certain

clinical scenarios, such as a stable patient with clinically suspected occult central nervous system malignancy,

inflammatory disorder, or central nervous system infection, although the yield of MRI in this setting may be low

[35].

Noncontrast MRI examinations of the brain are usually sufficient in the assessment of intracranial complications

related to hypertensive emergency, including posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

Variant 5: Adult. New onset psychosis. Initial imaging.

This variant addresses the role of neuroimaging in the assessment for secondary causes of new onset psychosis in

the ED or inpatient setting. Some of the reported organic causes of psychosis include tumors or infarcts in specific

areas of the brain, such as the temporal lobe, systemic lupus erythematosus, encephalitis, multiple sclerosis, Wilson

disease, Huntington disease, or metachromatic leukodystrophy [42-44].

Patients with new onset psychosis who have suspected stroke, focal neurologic deficit, seizure, head trauma, or

headache should refer to the respective ACR Appropriateness Criteria as appropriate: ACR Appropriateness

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

9 Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

Criteria

®

topics on “Cerebrovascular Diseases-Stroke and Stroke-Related Conditions” [16], “Seizures and

Epilepsy” [17], “Head Trauma” [18], or “Headache” [19] for further guidance.

CT Head With IV Contrast

Contrast-enhanced CT is generally not helpful for new onset psychosis in the absence of focal neurologic deficits.

CT Head Without and With IV Contrast

There is no relevant literature to support the use of CT head without and with IV contrast in the initial imaging of

this clinical scenario.

CT Head Without IV Contrast

The reported yield of CT in detecting pathology that may be responsible for psychotic symptoms or leading to a

significant change in clinical management is very low in patients with new onset psychosis and no neurologic

deficit, ranging from 0% to 1.5% in the literature search [42,45-47]. In a very small proportion of patients, CT of

the head revealed pathology that could account for new onset psychosis, including primary and secondary brain

tumors, infarcts, moderate to large arachnoid cysts in the temporal region, and a colloid cyst causing hydrocephalus

[42,45]. The evidence-based consensus guideline from the American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical

Policies Subcommittee on the Adult Psychiatric Patient entitled “Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Diagnosis

and Management of the Adult Psychiatric Patient in the Emergency Department” found that there is inadequate

literature on the usefulness of neuroimaging for new onset psychosis without a neurologic deficit in the ED setting

and recommended individual assessment of risk factors to guide the decision for neuroimaging in these patients

[48]. The “American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia,

second edition” suggests that brain MRI is preferred, and either MRI or a head CT scan may

provide helpful

information, particularly in patients for whom the clinical picture is unclear, the presentation is atypical, or there

are abnormal findings on examination [45,49]. In contrast, 1 study from the literature search found no significant

difference in the diagnostic yield of performing CT or MRI in this setting [45].

MRI Head With IV Contrast

There is no relevant literature to support the use of MRI head performed only with IV contrast in this clinical

scenario.

MRI Head Without and With IV Contrast

Brain MRI without and with IV contrast may be performed for definitive characterization of a focal lesion identified

on initial noncontrast CT examination or in patients with suspected autoimmune disorders, such as multiple sclerosis

or neuropsychiatric lupus [44,46].

MRI Head Without IV Contrast

The reported yield of MRI in the evaluation of new onset psychosis is very low in patients with no neurologic

deficit, with significant or possible causative findings found in 0% to 2.7% of cases in the literature search

[42,45,46,50]. In a small proportion of patients, MRI of the brain revealed pathology that may account for new

onset psychosis, including encephalitis, demyelinating disease, or brain tumors [42,45]. However, a comparative

study found no significant difference in the rate of clinically relevant pathology found by MRI in patients with

psychosis compared with a matched sample of healthy control subjects [50]. The evidence-based consensus

guideline from the American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee on the Adult

Psychiatric Patient entitled “Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Diagnosis and Management of the Adult

Psychiatric Patient in the Emergency Department” found that there is inadequate literature on the usefulness of

neuroimaging for new onset psychosis without a neurologic deficit in the ED setting and recommended individual

assessment of risk factors to guide decision for neuroimaging in these patients [48]. The “American Psychiatric

Association Practice Guidelines for Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia, second edition” suggests that brain

MRI is preferred and that either

MRI or CT may provide helpful information, particularly in patients for whom the

clinical picture is unclear, the presentation is atypical, or there are abnormal findings on examination [45,49]. In

contrast, 1 study from the literature search found no significant difference in the diagnostic yield of performing CT

or MRI in this setting [45].

Summary of Highlights

• Variant 1: For adult patients with new unexplained AMS and suspected intracranial pathology or focal

neurologic deficit, a noncontrast head CT is usually appropriate as the first-line neuroimaging test of choice in

this setting and can be performed safely and rapidly in all patients.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

10 Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

• Variant 2: For adult patients with AMS in the setting of known history of intracranial pathology, head CT

without IV contrast, brain MRI without IV contrast, and brain MRI without and with IV contrast are all

considered reasonable alternatives for initial imaging evaluation. In some cases, the choice among these 3

procedures may depend on prior history/imaging of the known intracranial pathology.

• Variant 3: For adult patients with AMS in the setting of suspected medical illness or toxic-metabolic cause,

neuroimaging evaluation is not always required, although brain MRI without IV contrast may be appropriate in

certain conditions known to be associated with intracranial injury. There was panel disagreement on the relative

appropriateness/value of noncontrast head CT in this clinical scenario.

• Variant 4: For adult patients with AMS despite clinical management of their known medical illness or toxic-

metabolic cause, a noncontrast head CT is usually appropriate as the first-line neuroimaging test of choice to

evaluate for a possible neurological source of their persistent AMS.

• Variant 5: For adult patients with new onset psychosis, neuroimaging evaluation is not always required. In

patients for whom the clinical picture is unclear, the presentation is atypical, or there are abnormal findings on

examination, head CT without IV contrast, brain MRI without IVcontrast, and brain MRI without and with IV

contrast may be appropriate and are all considered reasonable alternatives for imaging evaluation.

Supporting Documents

The evidence table, literature search, and appendix for this topic are available at https://acsearch.acr.org/list

. The

appendix includes the strength of evidence assessment and the final rating round tabulations for each

recommendation.

For additional information on the Appropriateness Criteria methodology and other supporting documents go to

www.acr.org/ac

.

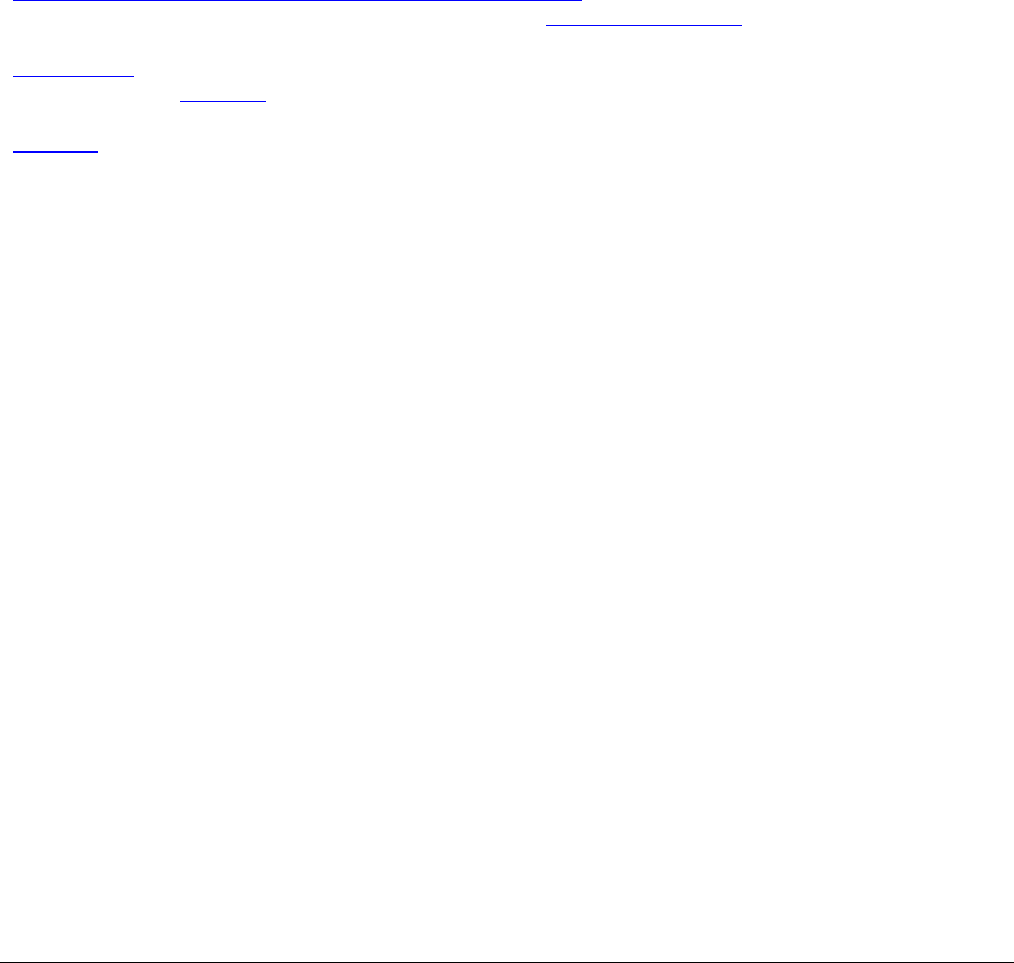

Appropriateness Category Names and Definitions

Appropriateness Category Name

Appropriateness

Rating

Appropriateness Category Definition

Usually Appropriate 7, 8, or 9

The imaging procedure or treatment is indicated in the

specified clinical scenarios at a favorable risk-benefit

ratio for patients.

May Be Appropriate 4, 5, or 6

The imaging procedure or treatment may be indicated

in the specified clinical scenarios as an alternative to

imaging procedures or treatments with a more

favorable risk-benefit ratio, or the risk-benefit ratio for

patients is equivocal.

May Be Appropriate

(Disagreement)

5

The individual ratings are too dispersed from the panel

median. The different label provides transparency

regarding the panel’s recommendation. “May be

appropriate” is the rating category and a rating of 5 is

assigned.

Usually Not Appropriate 1, 2, or 3

The imaging procedure or treatment is unlikely to be

indicated in the specified clinical scenarios, or the

risk-benefit ratio for patients is likely to be

unfavorable.

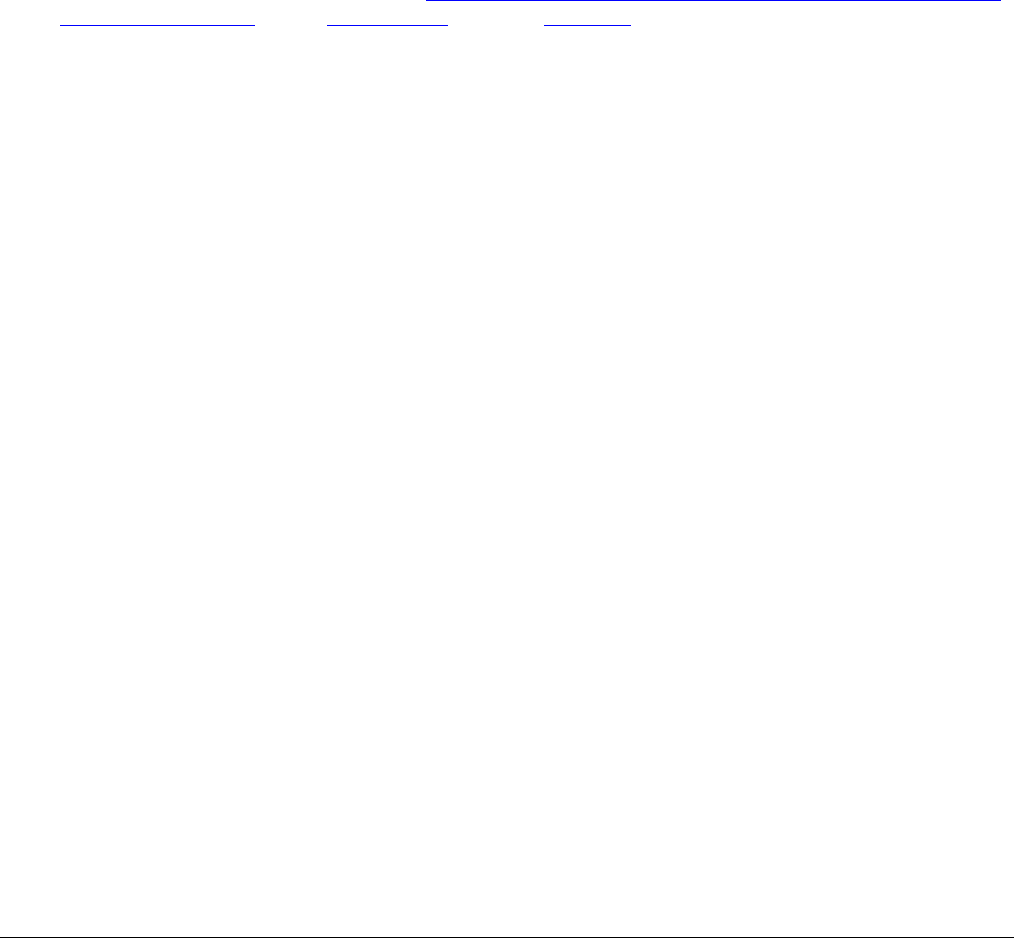

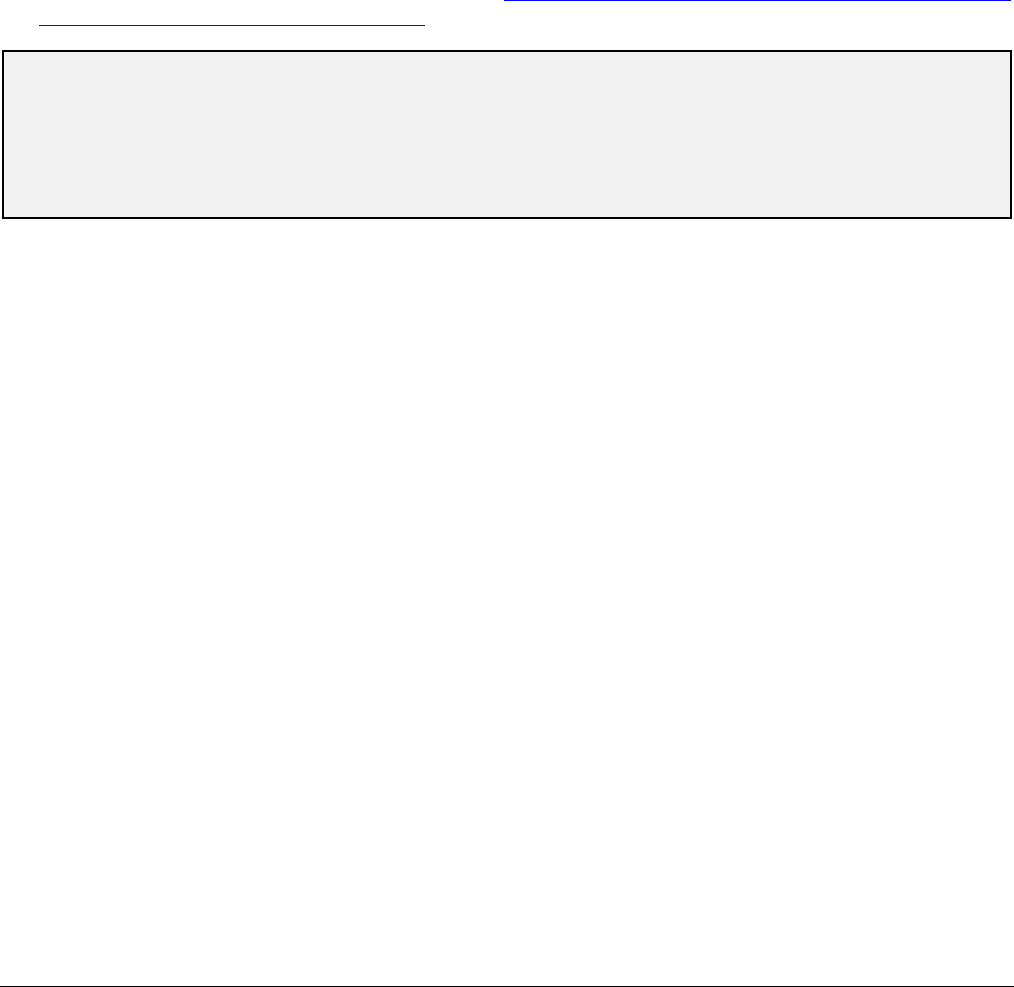

Relative Radiation Level Information

Potential adverse health effects associated with radiation exposure are an important factor to consider when

selecting the appropriate imaging procedure. Because there is a wide range of radiation exposures associated with

different diagnostic procedures, a relative radiation level (RRL) indication has been included for each imaging

examination. The RRLs are based on effective dose, which is a radiation dose quantity that is used to estimate

population total radiation risk associated with an imaging procedure. Patients in the pediatric age group are at

inherently higher risk from exposure, because of both organ sensitivity and longer life expectancy (relevant to the

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

11 Altered Mental Status, Coma, Delirium, and Psychosis

long latency that appears to accompany radiation exposure). For these reasons, the RRL dose estimate ranges for

pediatric examinations are lower as compared with those specified for adults (see Table below). Additional

information regarding radiation dose assessment for imaging examinations can be found in the ACR

Appropriateness Criteria

®

Radiation Dose Assessment Introduction document [51].

Relative Radiation Level Designations

Relative Radiation Level*

Adult Effective Dose Estimate

Range

Pediatric Effective Dose Estimate

Range

O

0 mSv 0 mSv

☢

<0.1 mSv <0.03 mSv

☢☢

0.1-1 mSv 0.03-0.3 mSv

☢☢☢

1-10 mSv 0.3-3 mSv

☢☢☢☢

10-30 mSv 3-10 mSv

☢☢☢☢☢

30-100 mSv 10-30 mSv

*RRL assignments for some of the examinations cannot be made, because the actual patient doses in these procedures vary

as a function of a number of factors (eg, region of the body exposed to ionizing radiation, the imaging guidance that is used).

The RRLs for these examinations are designated as “Varies.”

References

1. American College of Emergency P. Clinical policy for the initial approach to patients presenting with altered

mental status. Ann Emerg Med 1999;33:251-81.

2. Leong LB, Wei Jian KH, Vasu A, Seow E. Identifying risk factors for an abnormal computed tomographic scan

of the head among patients with altered mental status in the Emergency Department. Eur J Emerg Med

2010;17:219-23.

3. Han JH, Wilber ST. Altered mental status in older patients in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med

2013;29:101-36.

4. Xiao HY, Wang YX, Xu TD, et al. Evaluation and treatment of altered mental status patients in the emergency

department: Life in the fast lane. World J Emerg Med 2012;3:270-7.

5. Salani D, Valdes B, De Oliveira GC, King B. Psychiatric Emergencies: Emergency Department Management

of Altered Mental Status. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2021;59:16-25.

6. Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1157-65.

7. Wilber ST, Ondrejka JE. Altered Mental Status and Delirium. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2016;34:649-65.

8. Theisen-Toupal J, Breu AC, Mattison ML, Arnaout R. Diagnostic yield of head computed tomography for the

hospitalized medical patient with delirium. J Hosp Med 2014;9:497-501.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. 5th ed.

Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

10. Michaud L, Bula C, Berney A, et al. Delirium: guidelines for general hospitals. J Psychosom Res 2007;62:371-

83.

11. Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK. One-year health care costs associated with

delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:27-32.

12. Griswold KS, Del Regno PA, Berger RC. Recognition and Differential Diagnosis of Psychosis in Primary Care.

Am Fam Physician 2015;91:856-63.

13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Adults: Treatment and

Management: Updated Edition 2014. London: ; 2014.

14. Han JH, Schnelle JF, Ely EW. The relationship between a chief complaint of "altered mental status" and

delirium in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:937-40.

15. Sporer KA, Solares M, Durant EJ, Wang W, Wu AH, Rodriguez RM. Accuracy of the initial diagnosis among

patients with an acutely altered mental status. Emerg Med J 2013;30:243-6.

16. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

: Cerebrovascular Diseases-Stroke and Stroke-

Related Conditions. Available at: https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/3149012/Narrative/

. Accessed March 29, 2024.

17. Lee RK, Burns J, Ajam AA, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Seizures and Epilepsy. J Am Coll Radiol

2020;17:S293-S304.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

12Acute Mental Status Change

18. Shih RY, Burns J, Ajam AA, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Head Trauma: 2021 Update. J Am Coll

Radiol 2021;18:S13-S36.

19. Whitehead MT, Cardenas AM, Corey AS, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Headache. J Am Coll Radiol

2019;16:S364-S77.

20. Moonis G, Subramaniam RM, Trofimova A, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Dementia. J Am Coll Radiol

2020;17:S100-S12.

21. Fan E, Shahid S, Kondreddi VP, et al. Informed consent in the critically ill: a two-step approach incorporating

delirium screening. Crit Care Med 2008;36:94-9.

22. Hartjes TM, Meece L, Horgas AL. CE: Assessing and Managing Pain, Agitation, and Delirium in Hospitalized

Older Adults. Am J Nurs 2016;116:38-46.

23. Lavdas E, Mavroidis P, Kostopoulos S, et al. Improvement of image quality using BLADE sequences in brain

MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging 2013;31:189-200.

24. Acharya R, Kafle S, Shrestha DB, et al. Use of Computed Tomography of the Head in Patients With Acute

Atraumatic Altered Mental Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open

2022;5:e2242805.

25. Tu LH, Venkatesh AK, Malhotra A, et al. Scenarios to improve CT head utilization in the emergency

department delineated by critical results reporting. Emerg Radiol 2022;29:81-88.

26. Choi S, Na H, Nah S, Kang H, Han S. Is brain imaging necessary for febrile elderly patients with altered mental

status? A retrospective multicenter study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0236763.

27. Oliveira JESL, Berning MJ, Stanich JA, et al. Risk Factors for Delirium in Older Adults in the Emergency

Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Emerg Med 2021;78:549-65.

28. Shuaib W, Tiwana MH, Chokshi FH, Johnson JO, Bedi H, Khosa F. Utility of CT head in the acute setting:

value of contrast and non-contrast studies. Ir J Med Sci 2015;184:631-5.

29. Bent C, Lee PS, Shen PY, Bang H, Bobinski M. Clinical scoring system may improve yield of head CT of non-

trauma emergency department patients. Emerg Radiol 2015;22:511-6.

30. Khan S, Guerra C, Khandji A, Bauer RM, Claassen J, Wunsch H. Frequency of acute changes found on head

computed tomographies in critically ill patients: a retrospective cohort study. J Crit Care 2014;29:884 e7-12.

31. Lim BL, Lim GH, Heng WJ, Seow E. Clinical predictors of abnormal computed tomography findings in patients

with altered mental status. Singapore Med J 2009;50:885-8.

32. Narayanan V, Keniston A, Albert RK. Utility of emergency cranial computed tomography in patients without

trauma. Acad Emerg Med 2012;19:E1055-60.

33. Segard J, Montassier E, Trewick D, Le Conte P, Guillon B, Berrut G. Urgent computed tomography brain scan

for elderly patients: can we improve its diagnostic yield? Eur J Emerg Med 2013;20:51-3.

34. Hufschmidt A, Shabarin V. Diagnostic yield of cerebral imaging in patients with acute confusion. Acta Neurol

Scand 2008;118:245-50.

35. Hammoud K, Lanfranchi M, Li SX, Mehan WA. What is the diagnostic value of head MRI after negative head

CT in ED patients presenting with symptoms atypical of stroke? Emerg Radiol 2016;23:339-44.

36. Lever NM, Nystrom KV, Schindler JL, Halliday J, Wira C, 3rd, Funk M. Missed opportunities for recognition

of ischemic stroke in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2013;39:434-9.

37. Albrechtsen SS, Riis RGC, Amiri M, et al. Impact of MRI on decision-making in ICU patients with disorders

of consciousness. Behav Brain Res 2022;421:113729.

38. Malatt C, Zawaideh M, Chao C, Hesselink JR, Lee RR, Chen JY. Head computed tomography in the emergency

department: a collection of easily missed findings that are life-threatening or life-changing. J Emerg Med

2014;47:646-59.

39. Granata RT, Castillo EM, Vilke GM. Safety of deferred CT imaging of intoxicated patients presenting with

possible traumatic brain injury. Am J Emerg Med 2017;35:51-54.

40. Sparacia G, Anastasi A, Speciale C, Agnello F, Banco A. Magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of

brain involvement in alcoholic and nonalcoholic Wernicke's encephalopathy. World J Radiol 2017;9:72-78.

41. Lim CC, Gan R, Chan CL, et al. Severe hypoglycemia associated with an illegal sexual enhancement product

adulterated with glibenclamide: MR imaging findings. Radiology 2009;250:193-201.

42. Goulet K, Deschamps B, Evoy F, Trudel JF. Use of brain imaging (computed tomography and magnetic

resonance imaging) in first-episode psychosis: review and retrospective study. Can J Psychiatry 2009;54:493-

501.

43. Murphy R, O'Donoghue S, Counihan T, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol

Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88:697-708.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

13Acute Mental Status Change

44. Tan Z, Zhou Y, Li X, et al. Brain magnetic resonance imaging, cerebrospinal fluid, and autoantibody profile in

118 patients with neuropsychiatric lupus. Clin Rheumatol 2018;37:227-33.

45. Khandanpour N, Hoggard N, Connolly DJ. The role of MRI and CT of the brain in first episodes of psychosis.

Clin Radiol 2013;68:245-50.

46. Robert Williams S, Yukio Koyanagi C, Shigemi Hishinuma E. On the usefulness of structural brain imaging

for young first episode inpatients with psychosis. Psychiatry Res 2014;224:104-6.

47. Strahl B, Cheung YK, Stuckey SL. Diagnostic yield of computed tomography of the brain in first episode

psychosis. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2010;54:431-4.

48. American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee on the Adult Psychiatric P,

Nazarian DJ, Broder JS, et al. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Diagnosis and Management of the Adult

Psychiatric Patient in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med 2017;69:480-98.

49. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia,

second edition. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1-56.

50. Sommer IE, de Kort GA, Meijering AL, et al. How frequent are radiological abnormalities in patients with

psychosis? A review of 1379 MRI scans. Schizophr Bull 2013;39:815-9.

51. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria

®

Radiation Dose Assessment Introduction.

Available at:

https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Appropriateness-

Criteria/RadiationDoseAssessmentIntro.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2024.

The ACR Committee on Appropriateness Criteria and its expert panels have developed criteria for determining appropriate imaging examinations for

diagnosis and treatment of specified medical condition(s). These criteria are intended to guide radiologists, radiation oncologists and referring physicians in

making decisions regarding radiologic imaging and treatment. Generally, the complexity and severity of a patient’s clinical condition should dictate the

selection of appropriate imaging procedures or treatments. Only those examinations generally used for evaluation of the patient’s condition are ranked.

Other imaging studies necessary to evaluate other co-existent diseases or other medical consequences of this condition are not considered in this document.

The availability of equipment or personnel may influence the selection of appropriate imaging procedures or treatments. Imaging techniques classified as

investigational by the FDA have not been considered in developing these criteria; however, study of new equipment and applications should be encouraged.

The ultimate decision regarding the appropriateness of any specific radiologic examination or treatment must be made by the referring physician and

radiologist in light of all the circumstances presented in an individual examination.