Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for

Multidisciplinary Spine Care:

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain

7075 Veterans Blvd

Burr Ridge, IL 60527

630-230-3600

www.spine.org

© 2020 North American Spine Society

978-1-929988-65-5

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Preface

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

2

Authors & Contributors

Evidence-Based Guideline Development

Committee Co-Chairs

D. Scott Kreiner, MD

Paul Matz, MD

Diagnosis Section

Section Chair:

Daniel K. Resnick, MD, MS

Authors:

Norman B. Chutkan, MD, FACS

Adam C. Lipson, MD

Anthony J. Lisi, DC

Tom E. Reinsel, MD

Robert L. Rich Jr, MD, FAAFP; Stakeholder

Representative, American Academy of Family

Physicians (AAFP)

Contributor:

Robert C. Nucci, MD

Imaging Section

Section Co-Chairs:

Charles H. Cho, MD, MBA

Gary Ghiselli, MD

Authors:

Sean D. Christie, MD

Bernard A. Cohen, PhD

S. Raymond Golish, MD, PhD, MBA

Murat Pekmezci, MD

Walter S. Bartynski, MD; Stakeholder Representative,

American Society of Spine Radiology (ASSR)

Medical & Psychological Treatment Section

Section Chair:

Christopher M. Bono, MD

Authors:

Paul Dougherty, DC

Gazanfar Rahmathulla, MD, MBBS

Christopher K. Taleghani, MD

Terry Trammell, MD

Randall P. Brewer, MD; Stakeholder Representative,

American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM)

Ravi Prasad, PhD; Stakeholder Representative, American

Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM)

Contributor:

John P. Birkedal, MD

Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Section

Section Chair:

Charles A. Reitman, MD

Authors:

R. Carter Cassidy, MD

Dennis E. Enix, DC, MBA

Daniel S. Robbins, MD

Alison A. Stout, DO

Ryan A. Tauzell, PT, MA, MDT

Contributor:

William L. Tontz, Jr., MD

Interventional Treatment Section

Section Chair:

John E. Easa, MD, FIPP

Authors:

Jamie Baisden, MD, FACS

Shay Bess, MD

David S. Cheng, MD

David A. Provenzano, MD; Stakeholder Representative,

American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain

Medicine (ASRA)

Yakov Vorobeychik, MD, PhD; Stakeholder

Representative, Spine Intervention Society (SIS)

Contributors:

Michael P. Dohm, MD

Thomas J. Gilbert, MD

Joseph Gjolaj, MD

Matthew Smuck, MD, Stakeholder Representative,

American Academy of Physical Medicine and

Rehabilitation (AAPM&R)

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Preface

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

3

Surgical Treatment Section

Section Chair:

William C. Watters III, MD, MS

Authors:

Thiru M. Annaswamy, MD

Steven W. Hwang, MD

Cumhur Kilincer, MD, PhD

RJ Meagher, MD

Anil K. Sharma, MD

Kris E. Radcli, MD; Stakeholder Representative,

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS)

Contributor:

Jordan Gliedt, DC

Cost-Utility Section

Section Chair:

Zoher Ghogawala, MD, FACS

Authors:

Simon Dagenais, PhD, MSc, DC

Jerey A. King, DC, MS

Paul Park, MD

Daniel R. Perry, MPT, MDT

Jonathan N. Sembrano, MD

John E. O’Toole, MD, MS; Stakeholder Representative,

American Association of Neurological Surgeons

(AANS)

Padma Gulur, MD; Stakeholder Representative, Ameri-

can Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)

Contributors:

Darren R. Lebl, MD (Cost-Utility Section)

Alex Seldomridge, MD, MBA (Cost-Utility Section)

Participating Societies

(does not necessarily imply endorsement)

American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

(AAOS)

American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM)

American Association of Neurological Surgeons

(AANS)/Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS)

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)

American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain

Medicine (ASRA)

American Society of Spine Radiology (ASSR)

Spine Intervention Society (SIS)

Contributing Societies

(does not necessarily imply endorsement)

American Academy of Physical Medicine and

Rehabilitation (AAPM&R)

American Physical Therapy Association (APTA)

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Preface

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

4

Financial Statement/

Disclosures

This clinical guideline was developed and funded

in its entirety by the North American Spine Society

(NASS) with the exception that stakeholder societies

provided representatives and paid for the travel

and accommodation of their representatives to

recommendation meetings. All participating

authors have disclosed potential conicts of interest

consistent with NASS’ disclosure policy (http://

www.spine.org/DisclosurePolicy). Disclosures of all

authors and contributors are listed in the Technical

Report associated with this document.

Comments

Comments regarding this guideline may be submitted

to the North American Spine Society at guidelines@

spine.org and will be considered in development of

future revisions of the work.

Endorsements

Letters of endorsement from external societies can

be found in the Technical Report associated with this

document.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Preface

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

5

Table of Contents

I. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

II. Guideline Development Methodology and Process ..................................8

III. Glossary and Acronyms .............................................................12

IV. GuidelineDenitionandInclusion/ExclusionCriteria ...............................16

V. Summary of Recommendations ..................................................... 17

VI. Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain ..................40

A. Diagnosis .......................................................................40

B. Imaging .........................................................................60

C. Medical and Psychological Treatment ...........................................69

D. Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation .............................................101

E. Interventional Treatment .......................................................158

F. Surgical Treatment .............................................................190

G. Cost-Utility ....................................................................198

VII. Appendices ........................................................................213

A full bibliography and technical report, including the literature search parameters and evidentiary tables

developed by the authors, can be accessed at https://www.spine.org/Research-Clinical-Care/Quality-

Improvement/Clinical-Guidelines.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Introduction

6

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Objective

The objective of the North American Spine Society

(NASS) Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treat-

ment of Low Back Pain is to provide evidence-based

recommendations to address key clinical questions

surrounding the diagnosis and treatment of adult

patients with nonspecic low back pain. This guide-

line is based upon a systematic review of the evidence

and reects contemporary treatment concepts for

low back pain as reected in the highest quality clin-

ical literature available on this subject as of February

2016. The goals of the guideline recommendations are

to assist in delivering optimum, ecacious treatment

and functional recovery from nonspecic low back

pain.

Scope, Purpose and Intended User

This document was developed by the North American

Spine Society Evidence-Based Guideline Development

Committee with representation from stakeholder or-

ganizations as an educational tool to assist practi-

tioners who treat adult patients with nonspecic low

back pain. The goal is to provide a tool that assists

practitioners in improving the quality and eciency

of care delivered to these patients. The NASS Clinical

Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back

Pain outlines a reasonable evaluation of patients with

nonspecic low back pain and outlines treatment op-

tions for adult patients with this condition.

THIS GUIDELINE DOES NOT REPRESENT A

“STANDARD OF CARE,” nor is it intended as a xed

treatment protocol. It is anticipated that there will be

patients who will require less or more treatment than

the average. It is also acknowledged that in atypical

cases, treatment falling outside this guideline will

sometimes be necessary. This guideline should not

be seen as prescribing the type, frequency or duration

of intervention. Treatment should be based on the

individual patient’s need and doctor’s professional

judgment and experience. This document is designed

to function as a guideline and should not be used as

the sole reason for denial of treatment and services.

This guideline is not intended to expand or restrict a

health care provider’s scope of practice or to supersede

applicable ethical standards or provisions of law.

Patient Population

The patient population for this guideline encompass-

es adults (18 years or older) with low back pain dened

as pain of musculoskeletal origin extending from the

lowest rib to the gluteal fold that may at times extend

as somatic referred pain into the thigh (above the

knee).

Considerations:WhyThisGuidelineIsDierent

andHowExclusionofLegPainImpactsthe

Recommendations

NASS typically writes clinical guidelines based on di-

agnosis. Due to demand and the expertise of NASS

spine care specialists, NASS, in this single instance,

has opted to address low back pain as a generalized

topic rather than a specic diagnosis or code. As a

multidisciplinary organization for spine care provid-

ers, NASS was uniquely positioned to provide specialty

expertise and a real-world perspective on multidisci-

plinary spine care. It is important to keep in mind that

“low back pain” is no more a diagnosis in the spine

eld than “chest pain” is for cardiology, but rather a

generalized patient complaint that can encompass a

variety of diagnoses.

Recommendations were developed based on a specic

denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the re-

sulting literature which excluded leg pain below the

knee. Leg pain was excluded in order to address treat-

ment of nonspecic low back pain. For many sections,

the inclusion of leg pain in the literature search would

have included many specic causes of back pain, in-

cluding disc herniation and spondylolisthesis, that

would have made the focus on nonspecic low back

pain more dicult and less clear.

Without the inclusion of leg pain, these guideline rec-

ommendations address only a subset of low back pain

and its care. The inclusion and exclusion criteria used

resulted in the removal of multiple articles that may

have inuenced overall recommendations for a par-

ticular treatment or procedure. Evaluation of a par-

ticular treatment or procedure under dierent clinical

circumstances would necessitate a separate evalua-

tion of the evidence.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Introduction

7

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Due to the time needed to develop a guideline of this

size and breadth, some explanation is needed as to the

why or why not certain items can be found in the con-

tent.

Although opioids are addressed, it is in a limited

fashion. The opioid crisis as we know it today was

a phenomenon that reached crisis proportions af-

ter the guideline was already in development. In

the future, more substantial attention to this is-

sue will be merited.

This is the largest clinical guideline NASS has

ever undertaken and four years in the making.

There were 82 clinical questions and the literature

search resulted in more than 45,000 articles. Due

to the high volume of literature and the labor-

intensive nature of the review, literature search

dates are spread out in some instances (although

most were within the same month). In addition,

consideration should be given to the fact that

newer research has been published since the

literature searches have taken place.

This document is based on the evidence known at

the time of the literature review. However, evi-

dence can be incomplete or immature and recom-

mendations can change in the future where the

current evidence is thin, weak, or evolving. NASS’

future recommendations for research are a valu-

able tool when considering these areas.

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Development Methodology and Process

8

Guideline Development

Methodology

Through objective evaluation of the evidence

and transparency in the process of making

recommendations, it is NASS’ goal to develop

evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the

diagnosis and treatment of adult patients with various

spinal conditions. These guidelines are developed for

educational purposes to assist practitioners in their

clinical decision-making processes.

Multidisciplinary and Multi-Stakeholder

Collaboration

With the goal of ensuring the best possible care for

adult patients suering with spinal disorders, NASS

is committed to multidisciplinary involvement in the

process of guideline development. To this end, NASS

has ensured that representatives from research, both

operative and non-operative, medical, interventional

and surgical spine specialties have participated in the

development and review of NASS guidelines. To en-

sure broad-based representation on this topic, NASS

invited representatives from organizations whose

members are involved in the care of patients with low

back pain to serve on guideline work groups. A more

detailed description of stakeholder involvement is

included under the “Guideline Development Process”

on page 9.

Evidence Analysis Training of all Guideline

Developers

As a condition of participation, all developers com-

pleted NASS’ Fundamentals of Evidence-Based Med-

icine Training prior to participating in guideline de-

velopment. The training includes a series of readings

and exercises to prepare guideline developers for

systematically evaluating literature and developing

evidence-based guidelines. Participants are awarded

CME credit upon completion of the course.

DisclosureofPotentialConictsofInterest

All participants involved in guideline development

have disclosed potential conicts of interest to their

colleagues in accordance with NASS’ Disclosure Pol-

icy (https://www.spine.org/DisclosurePolicy) and

their potential conicts have been documented in the

Technical Report associated with this guideline. NASS

does not restrict involvement in guidelines based on

conicts as long as members provide full disclosure.

Individuals with a conict relevant to the subject

matter were asked to recuse themselves from delib-

eration. Participants have been asked to update their

disclosures regularly throughout the guideline devel-

opment process.

Levels of Evidence and Grades of

Recommendation

NASS has adopted standardized levels of evidence

(Appendix A) and grades of recommendation (Appen-

dix B) to assist practitioners in easily understanding

the strength of the evidence and recommendations

within the guidelines. The levels of evidence range

from Level I (high quality randomized controlled tri-

al) to Level V (expert consensus). Grades of recom-

mendation indicate the strength of the recommenda-

tions made in the guideline based on the quality of the

literature.

Grades of Recommendation:

A: Good evidence (Level I studies with consistent

ndings) for or against recommending interven-

tion.

B: Fair evidence (Level II or III studies with con-

sistent ndings) for or against recommending

intervention.

C: Poor quality evidence (Level IV or V studies) for

or against recommending intervention.

I: Insucient or conicting evidence not allowing

a recommendation for or against intervention.

Levels of evidence have very specic criteria and are

assigned to studies prior to developing recommenda-

tions. Recommendations are then graded based upon

the level of evidence. To better understand how levels

of evidence inform the grades of recommendation and

the standard nomenclature used within the recom-

mendations see Appendix C.

Guideline recommendations are written utilizing a

standard language that indicates the strength of the

recommendation. “A” recommendations indicate a

test or intervention is “recommended”; “B” recom-

mendations “suggest” a test or intervention and “C”

recommendations indicate a test or intervention “may

be considered” or “is an option.” “I” or “Insucient

Evidence” statements clearly indicate that “there is

insucient evidence to make a recommendation for

or against” a test or intervention. Work group con-

sensus statements clearly state that “in the absence of

reliable evidence, it is the work group’s opinion that”

a test or intervention may be appropriate.

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Development Methodology and Process

9

In evaluating studies as to levels of evidence for this

guideline, the study design was interpreted as estab-

lishing only a potential level of evidence. As an ex-

ample, a therapeutic study designed as a randomized

controlled trial would be considered a potential Level

I study. The study would then be further analyzed as

to how well the study design was implemented and

signicant shortcomings in the execution of the study

would be used to downgrade the levels of evidence for

the study’s conclusions. In the example cited previ-

ously, reasons to downgrade the results of a potential

Level I randomized controlled trial to a Level II study

II would include, among other possibilities: an un-

derpowered study (patient sample too small, variance

too high), inadequate randomization or masking of

the group assignments and lack of validated outcome

measures.

In addition, a number of studies were reviewed sev-

eral times in answering dierent questions within

this guideline. How a given question was asked might

inuence how a study was evaluated and interpreted

as to its level of evidence in answering that particular

question. For example, a randomized controlled trial

reviewed to evaluate the dierences between the out-

comes of surgically treated versus untreated patients

with lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy might

be a well-designed and implemented Level I ther-

apeutic study. This same study, however, might be

classied as providing Level II prognostic evidence if

the data for the untreated controls were extracted and

evaluated prognostically.

Guideline Development Process

Step 1: Recruitment of Guideline Members and

Involvement of Stakeholder Representatives

NASS Evidence-Based Guideline Development Com-

mittee members were solicited to participate in the

guideline development process. NASS also invited

stakeholder organizations who participate in the Spine

Summit, a multi-stakeholder meeting convened to

discuss and collaborate on projects that advance the

eld of spine care, to nominate representatives from

their respective organization to serve on the guideline

panel. Additional specialties not represented at the

Spine Summit were also solicited to participate in the

guideline to ensure broad representation of all spe-

cialties directly involved in the care of patients with

low back pain. In total, 62 volunteers participated in

this eort, including 11 stakeholder societies. Names

of guideline panelists are listed on page 2 and dis-

closures are listed in the Technical Report associated

with this document. The stakeholder groups can also

be found on page 3.

NASS spearheaded this guideline eort by providing

sta support and nancial support, including liter-

ature searches, full text articles, webinar/conference

capabilities and food and beverage and facility fees

for the in-person recommendation meetings. Stake-

holder organizations were asked to cover travel and

accommodation related expenses for their represen-

tative to attend any in-person meetings.

Step 2: Identication of Work Groups

The guideline panel consists of seven sections: Diag-

nosis, Imaging, Medical and Psychological Treatment,

Interventional Treatment, Physical Medicine and Re-

habilitation, Surgical Treatment and Cost-Utility.

Stakeholder societies were asked to rank their interest

in participating in each section and their representa-

tive was placed in their rst or second choice. Senior

and newer NASS Evidence-Based Guideline Develop-

ment members were equally placed in work groups to

ensure that groups with newer members were bal-

anced with members who have more guideline de-

velopment experience. Each work group consisted

of 7 to 11 members representing multi-disciplinary

backgrounds. The guideline panel includes represen-

tation from the elds of primary care, psychology,

neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery, physical medicine

and rehabilitation, physiatry, chiropractic care, phys-

ical therapy, anesthesiology, research, and radiology.

NASS believes that having multidisciplinary teams

involved in the guideline development process helps

to minimize inadvertent biases in evaluating the lit-

erature and formulating recommendations.

Step 3: Surveying Patients

To seek patient input to help inform the development

of clinical questions, NASS circulated an informal

Survey Monkey poll to better understand patients’

experiences with low back pain treatment. The sur-

vey link was circulated through various websites and

social media sites, including NASS’ Facebook and

Twitter pages; spine-health.com’s website, Face-

book group and blog; Low-Back Pain Patient Support

Group on Facebook; Lower Back Pain Management

Support Group on Facebook; and numerous Facebook

shares (of the survey link) on consumer and physician

proles. A total of 415 people opened the survey link,

including 413 who consented to participate in the sur-

vey and 2 who did not participate. The survey included

the following questions that allowed for check the box

and open-ended responses:

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Development Methodology and Process

10

1. What symptoms made you seek medical attention

for your current and/or any past episodes of low-

back pain?

2. Please identify the treatment(s) you received for

your current and/or any past episodes of low back

pain.

3. Based on your treatment experiences for your

current and any previous episodes of low back

pain, is there anything that you wish your health-

care provider shared with you before making your

decision to receive treatment?

4. What questions do you recommend that other pa-

tients with low back pain ask their providers when

seeking a diagnosis and treatment options for low

back pain?

Step 4: Identication of Clinical Questions

Framing questions to ask in the guideline is critical to

the guideline development process. Guideline partici-

pants were asked to submit a list of clinical questions

pertaining to their assigned section with the patient

survey as reference. Members were asked to use the

acronym “PICO” when drafting questions. “PICO”

serves to guide the development of clinical questions

that include all of the necessary components to build a

literature search: “P” for the patient/problem; “I” for

the intervention or indicator of interest (procedures,

therapies, diagnostic tests, exposure, etc.); “C” for

comparison and “O” for outcome of interest. The pro-

posed questions were compiled into a master list and

circulated to each member for review and comment.

Step 5: External Review of Clinical Question

Protocol

The draft list of clinical questions was made public-

ly available on the NASS website for a 4-week public

comment period from June 16, 2015 to July 14, 2015.

Additionally, stakeholders were invited through email

solicitations to comment on the draft questions. In

response, 27 individuals and organizations submit-

ted comment letters. Based on feedback, several re-

visions were incorporated in the guideline denition

and clinical question list. After the comment period,

an updated clinical question list with summarized

changes was posted to the NASS website and circulat-

ed to all public comment period reviewers.

Step 6: Identication of Search Terms and

Parameters

One of the most crucial elements of evidence analy-

sis is the comprehensive literature search. Thorough

assessment of the literature is the basis for the re-

view of existing evidence and the formulation of ev-

idence-based recommendations. In order to ensure

a thorough literature search, NASS has instituted a

Literature Search Protocol (Appendix D) which has

been followed to identify literature for evaluation in

guideline development. In keeping with the Literature

Search Protocol, work group members have identied

appropriate search terms and parameters to direct the

literature search. Specic search strategies, including

search terms, parameters and databases searched, are

documented in the Technical Report associated with

this document. The guideline denition and inclu-

sion/exclusion criteria are outlined on page 16.

Step 7: Completion of the Literature Search

Once each work group identied search terms/pa-

rameters, the literature search was implemented by

a medical/research librarian at InfoNOW at the Uni-

versity of Minnesota, consistent with the Literature

Search Protocol. Following these protocols ensures

that NASS recommendations (1) are based on a thor-

ough review of relevant literature; (2) are truly based

on a uniform, comprehensive search strategy; and (3)

represent the current best research evidence avail-

able. NASS maintains a search history in Endnote, for

future use or reference.

Step 8: Review of Search Results/Identication

of Literature to Review

Work group members reviewed all abstracts yielded

from the literature search and identied the litera-

ture they would review in order to address the clinical

questions, in accordance with the Literature Search

Protocol (Appendix D).

Step 9: Evidence Analysis

Members independently developed evidentiary ta-

bles summarizing study conclusions, identifying

strengths and weaknesses and assigning levels of ev-

idence. In order to systematically control for poten-

tial biases, two or more work group members have

reviewed each article selected and independently as-

signed levels of evidence to the literature using the

NASS levels of evidence. Any discrepancies in scoring

have been addressed by two or more reviewers. Final

ratings are completed at a nal meeting or web con-

ference of section workgroup members including the

section chair and a guideline co-chair. As a nal step

in the evidence analysis process, members have iden-

tied and documented gaps in the evidence to educate

guideline readers about where evidence is lacking and

help guide further needed research.

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Development Methodology and Process

11

Step 10: Formulation of Evidence-Based

Recommendations and Incorporation of Expert

Consensus

Work groups held web-conferences and face-to-face

meetings to discuss the evidence-based answers to

the clinical questions, the grades of recommenda-

tions and the incorporation of expert consensus. Ex-

pert consensus was incorporated only where Level

I-IV evidence is insucient and the work group has

deemed that a recommendation is warranted. Trans-

parency in the incorporation of consensus is crucial

and all consensus-based recommendations made in

this guideline very clearly indicate that Level I-IV ev-

idence is insucient to support a recommendation

and that the recommendation is based only on expert

consensus.

Consensus Development Process

For recommendations with a consensus grading,

voting was conducted using a modication of the

nominal group technique in which each work group

member independently and anonymously ranked

a recommendation on a scale ranging from 1 (“ex-

tremely inappropriate”) to 9 (“extremely appropri-

ate”). Consensus was obtained when at least 80% of

work group members ranked the recommendation as

7, 8 or 9. When the 80% threshold was not attained,

up to three rounds of discussion and voting were held

to resolve disagreements. If disagreements were not

resolved after these rounds, no recommendation was

adopted. After the recommendations were estab-

lished, work group members developed the guideline

content, addressing the literature supporting the rec-

ommendations.

Step 11: Internal Review of Draft Guideline

Guideline sections were reviewed by the section work

groups that developed them. The full guideline draft

was submitted to the guideline co-chairs and NASS

Research Council for review and comment. Revisions

to recommendations were considered only when sub-

stantiated by a preponderance of appropriate level ev-

idence.

Step 12: External Review of Draft Guideline

Stakeholder societies were invited to comment on

the draft guideline during an external review period

June-August 2019. Nine of 11 stakeholder societies

provided comments. Revisions to recommendations

were considered only when substantiated by a pre-

ponderance of appropriate level evidence. Responses

to external comments are available in the technical

report associated with this guideline. Prior to publi-

cation, external stakeholders were invited to be listed

as participating or contributing societies.

Step 13: Submission for Board Approval

Once any evidence-based revisions were incorporat-

ed, the drafts were prepared for NASS Board of Di-

rectors review and approval. Edits and revisions to

recommendations and any other content were con-

sidered for incorporation only when substantiated by

a preponderance of appropriate level evidence.

Step 14: Submission for Publication

Following NASS Board approval, the guidelines were

slated for publication. No revisions were made after

submission for publication, but comments have been

and will be saved for the next iteration.

Step 15: Review and Revision Process

The guideline recommendations will be reviewed ev-

ery ve years by an EBM-trained multidisciplinary

team and revised as appropriate after review and as-

sessment of relevant literature published since the

development of this version of the guideline or the

guideline will be rescinded if it will not be updated.

Use of Acronyms

Throughout the guideline, readers will see many ac-

ronyms with which they may not be familiar. A glos-

sary of acronyms is available on page 14.

NomenclatureforMedical/Interventional

Treatment

Throughout the guideline, readers will see that what

has traditionally been referred to as “nonoperative,”

“nonsurgical,” or “conservative” care is now referred

to as “medical/interventional care.” The term medi-

cal/interventional is meant to encompass pharmaco-

logical treatment, physical therapy, exercise therapy,

manipulative therapy, modalities, various types of

external stimulators and injections.

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Glossary & Acronyms

12

Glossary

Acute low back pain: Within rst 6 weeks of person’s

current LBP episode.

1

Chronic low back pain: Symptoms for current LBP

episode present for greater than 12 weeks.

2

General tness program: Exercise program not fo-

cused on specic muscle groups; by denition the goal

is to improve the overall general tness of the patient

by using a combination of aerobic conditioning with

stretching/strengthening of all major muscle groups.

Lumbar stabilization exercises: Focused on facilitat-

ing and strengthening specic muscles that directly

or indirectly control spinal joint function, especially

the abdominal, gluteal and spinal extensor muscle

groups.

Medical/interventional treatment: The term medi-

cal/interventional treatment is used in place of “non-

operative,” “conservative,” or “nonsurgical” treat-

ment. It encompasses pharmacological treatment,

physical therapy, exercise therapy, manipulative

therapy, modalities, various types of external stimu-

lators and injections.

Nonspecic low back pain: Pain in which no specic

cause or structure can be identied to account for the

patient’s perceived symptoms.

3

Radiculopathy: Dysfunction of a nerve root associated

with pain, sensory impairment, weakness, or dimin-

ished deep tendon reexes in a nerve root distribu-

tion.

4

Recurrent low back pain: Symptoms less than ½ the

days in a year occurring in multiple episodes.

5

Sciatica: Pain radiating down the leg below the knee in

the distribution of the sciatic nerve, suggesting nerve

root compromise due to mechanical pressure or in-

ammation. Sciatica is the most common symptom

of lumbar radiculopathy.

4

Specic low back pain: Pain that can be linked to a

disorder, disease, infection, injury, trauma, or struc-

tural deformity. A potential causal relationship can be

found between the diagnosis and the pain.

3

Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT): SMT is dened

as spinal manipulative therapy, manual therapy, mo-

bilization and high velocity thrusts.

Subacute low back pain: Symptoms for current LBP

episode present for 6-12 weeks.

1

Visceral diseases resulting in back pain: Pain second-

ary to diseases of the viscera. Examples: endometrio-

sis, prostatitis, aortic aneurysm.

5

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Glossary & Acronyms

13

Red Flag Conditions

4,6-7

History

Cancer

Unexplained weight loss

Immunosuppression

Intravenous drug use

Urinary tract infection

Fever

Signicant trauma relative to age

Bladder or bowel incontinence

Urinary retention (with overow incontinence)

PhysicalExamination

Saddle anesthesia

Loss of anal sphincter tone

Major motor weakness in lower extremities

Fever

Neurologic ndings persisting beyond one month

or progressively worsening

References

1. Frymoyer JW. Back pain and sciatica. N Engl J Med.

1988;318(5):291-300.

2. Von Kor M. Studying the natural history of back

pain. Spine. 1994;19(18 Suppl):2041S-6S.

3. Nordin M, Weiser S, van Doorn JW, Hiebert R. Non-

specic low back pain. In: Rom.W.N., editor. Envi-

ronmental and Occupational Medicine. 3rd ed. Phila-

delphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1998. p.

947-56.

4. Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and

treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice

guideline from the American College of Physicians

and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med.

2007;147(7):478-491.

5. Deyo RA. Early diagnostic evaluation of low back

pain. J Gen Int Med. 1986;1(5):328-38.

6. Bigos SJ, Bowyer OR, Braen GR, Brown K, Deyo R,

Haldeman S, et al. Acute low back problems in adults.

Clinical practice guideline no. 14 (AHCPR publication

no. 95-0642). Rockville, Md.: U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services, Public Health Service,

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, De-

cember 1994.

7. Forseen S, Corey A. Clinical decision support and

acute low back pain: evidence-based order sets. J

Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9(10):704-12

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Glossary & Acronyms

14

Acronyms

AAQ-II Acceptance and Action Questionnaire

ADS Allgemeine Depressions-Skala

ALIF Anterior lumbar interbody fusion

AM Active management

BDI Beck Depression Inventory

BDI-II Beck Depression inventory-II

BMI Body mass index

BMP Bone morphogenetic protein

BPI Brief Pain Inventory

CBA Cognitive behavioral approach

CBT Cognitive behavioral therapy

CCBT Contextual cognitive-behavioral

therapy

CEQ Cognitive Error Questionnaire

CLBP Chronic low back pain

CMDQ Common Mental Disorders

Questionnaire

COX-2 Cyclooxygenase-2

CPAQ Chronic Pain Acceptance

Questionnaire

CPR Clinical Prediction Rule

CT Computed tomography

DPQ Dallas Pain Questionnaire

DD Disc degeneration

DDS Descriptor Dierential Scale

DIS Diagnostic Interview Schedule Version

III-R

DSN Disc space narrowing

ED Emergency department

EEG Electroencephalogram

ESC End plate signal change

EMG Electromyography

ESI Epidural steroid injection

FABQ Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire

FD End of First Dose

FJ Facet joint

FJOA Facet joint osteoarthrosis

FJP Facet joint pain

FRI Function Rating Index

HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

HADS-D Anxiety Hospital Anxiety and

Depression Scale

HILT High-intensity laser therapy

HIZ High intensity zone

HRQOL Health related quality of life

IAS Illness Attitude Scale

IDD Internal disc disruption

IDD Intervertebral Dierential Dynamics

IPQ-R Revised Illness Perception

Questionnaire

IDET Intradiscal electrothermal therapy

IDETA Intradiscal electrothermal anuloplasty

IV Intravenous

K-ODI Korean Oswestry Disability Index

K-SF-36 Korean Short Form-36

LBP Low back pain

MDR Multidisciplinary rehabilitation

MDT Mechanical diagnosis and therapy

MMPI Minnesota Multiphasic Personality

Inventory

MPQ McGill Pain Questionnaire

MR Magnetic resonance

MRI Magnetic resonance imaging

MSPQ Modied Somatic Perception

Questionnaire

MVK Modied Von Kor Scale

NPRS Numeric Pain Rating Scale

NRS Numerical rating scale

NSAIDS Nonsteroidal anti-inammatory drugs

ODI Oswestry Disability Index

ODQ Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability

Questionnaire

OLBPQ Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability

Questionnaire

PCS Pain Catastrophizing Scale

PDI Pain Disability Index

PGADS Patient Global Assessment of Disease

Status

PGAP Progressive Goal Attainment Program

PGI-I Patient’s Global Impressions of

Improvement

PHIC Modied Patient Global Impression of

Change

PLF Posterolateral fusion

PLIF Posterior lumbar interbody fusion

PRI Pain Rating Index

PRP Platelet-rich plasma

PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

PTSD Post-traumatic stress disorder

QALYs Quality-adjusted life years

QOL Quality of life

PENS Percutaneous electrical nerve

stimulation

RCT Randomized controlled trial

RMDQ Roland Morris Disability

Questionnaire

ROAD Research on Osteoarthritis/

Osteoporosis against Disability

RTW Return to work

SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist

SEBT Star excursion balance test

SF-36 Medical Outcome Study Short Form-

36

SFMPQ Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Glossary & Acronyms

15

SI Sacroiliac

SIJ Sacroiliac joint

SIJI Sacroiliac joint injection

SIJP Sacroiliac joint pain

SIP Sickness Impact Prole

SJD Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

SMT Spinal manipulative therapy

SN Schmorl’s nodes

SPECT Single photon emission computerized

tomography

STAXI State-Trait Anger Expression

Inventory

TDR Total disc replacement

TENS Transcutaneous electrical nerve

stimulation

TLIF Transforaminal lumbar interbody

fusion

TSE Transcutaneous spinal

electroanalgesia

TSK Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

TTM Transtheoretical Model

UK BEAM UK Back pain Exercise And

Manipulation (UK BEAM)

VAS Visual analog scale

VNS Visual Numeric Pain Scale

VO Vertebral osteophytes

VRS Verbal rating scale

ZDS Zung Depression Scale

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain |

16

Denition & Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Denition

Low back pain is dened as pain of musculoskeletal

origin extending from the lowest rib to the gluteal

fold that may at times extend as somatic referred pain

into the thigh (above the knee).

Inclusion Criteria

1. Adult patients aged 18 and older

2. Patients with low back pain limited to somatic re-

ferred pain/non-radicular pain limited to above

the knee only

Exclusion Criteria

1. Patients less than 18 years of age

2. Low back pain due to:

a. Tumor

b. Infection

c. Metabolic disease

d. Inammatory arthritis

e. Fracture

3. Patients with a diagnosed deformity, including

spondylolisthesis, spondylolysis and scoliosis

4. Pain experienced below the knee

5. Extra-spinal conditions (ie, visceral, vascular,

genito-urinary)

6. Patients who have undergone prior lumbar sur-

gery

7. Presence of neurological decit

8. Back pain that is associated with widespread

multi-site pain (>2 sites)

9. Pregnancy

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

17

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Summary of Recommendations

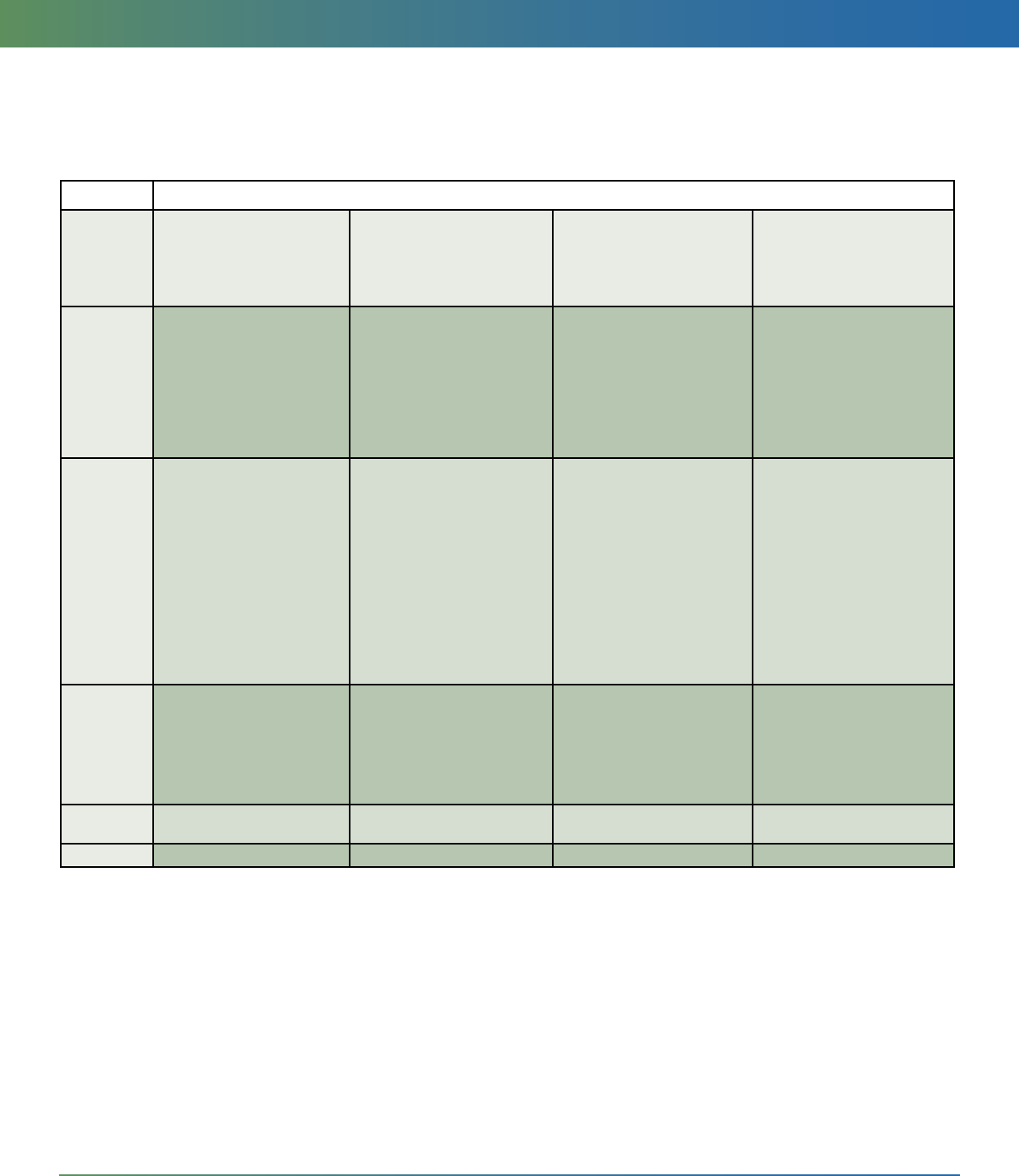

Clinical Question Guideline Recommendation

See recommendation sections for supporting text

A=Recommended; B=Suggested; C=May be considered; I=Insucient or

Conicting Evidence

Diagnosis

Diagnosis Question 1. In patients

with low back pain, are there spe-

cic history or physical examina-

tion ndings that would indicate

the structure causing pain and,

therefore, guide treatment?

a. Vertebral body

b. Intervertebral disc

c. Zygapophyseal joint

d. Posterior elements

e. Sacroiliac joint

f. Muscle/tendon

g. Central sensitization

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the

use of innominate kinematics for the assessment of sacroiliac joint pain.

Grade of Recommendation: I

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the

use of pain localization in predicting response to a diagnostic injection.

Grade of Recommendation: I

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the

assessment of centralization or peripheralization for the prediction of discog-

raphy results.

Grade of Recommendation: I

Diagnosis Question 2. In patients

with low back pain, are there histo-

ry or physical examination ndings

that would serve as predictors for

the recurrence of low back pain?

There is insucient evidence to indicate that body mass index (BMI) is a po-

tential predictor of a recurrence of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: I

It is suggested that history of low back pain is a potential predictor of a recur-

rence of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: B

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Summary of Recommendations

18

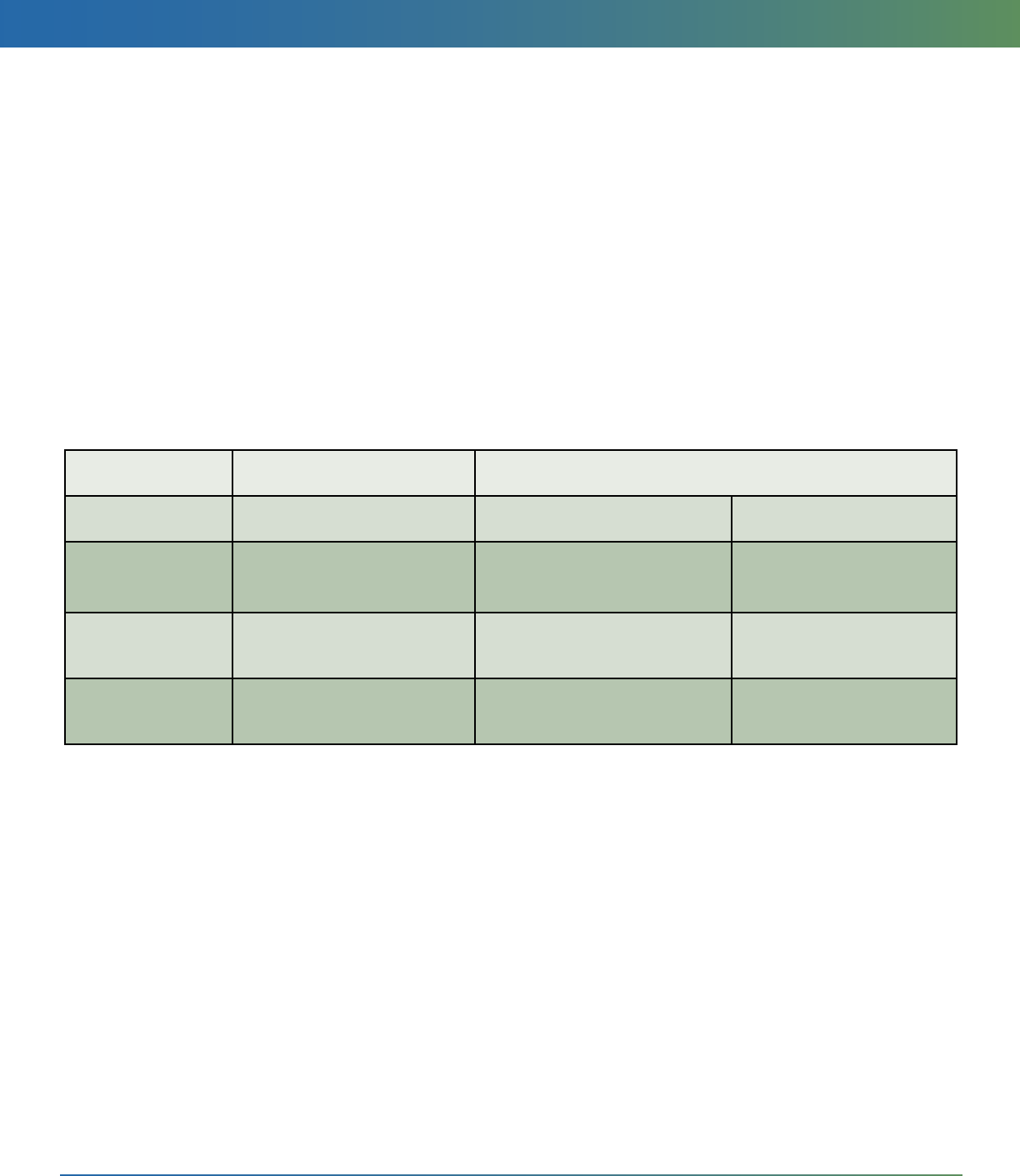

Diagnosis Question 3. In patients

with acute low back pain, are there

history or physical examination

ndings that would predict that

an episode will resolve within one

month?

Diagnosis Question 6. What are

the patient characteristics that

increase or decrease the risk of

developing chronic low back pain

after an acute episode?

Diagnosis Question 9. Does a psy-

chological evaluation assist with

identifying patients with low back

pain who are at risk for developing

chronic pain or disability?

The work group considered these

questions together as the vast ma-

jority of the literature evaluating the

conversion from acute to chronic

pain combined various demograph-

ic, social, psychological and physical

examination ndings in predictive

models.

It is recommended that psychosocial factors and workplace factors be as-

sessed when counseling patients regarding the risk of conversion from acute

to chronic low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: A

It is recommended that psychosocial factors be used as prognostic factors

for return to work following an episode of acute low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: A

It is recommended that pain severity and functional impairment be used to

stratify risk of conversion from acute to chronic low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: A

It is suggested that prior episodes of low back pain be considered a prognos-

tic factor for the conversion from acute to chronic low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: B

There is insucient evidence to assess sleep quality as a prognostic variable

to predict recovery from acute low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: I

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the

use of smoking and/or obesity as prognostic factors for the conversion from

acute to chronic low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: I

Diagnosis Question 4. In patients

with low back pain, what histo-

ry and/or physical examination

ndings are useful in determining

if the cause is nonstructural in

nature and, therefore, guide treat-

ment?

A nonstructural cause of low back pain may be considered in patients with

diuse low back pain and tenderness.

Grade of Recommendation: C

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the

use of fear avoidance behavior to determine the likelihood of a structural

cause of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: I

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the

presence of diuse back tenderness for the prediction of the presence of

disc degeneration on radiographs.

Grade of Recommendation: I

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Summary of Recommendations

19

Diagnosis Question 5. In patients

with low back pain, what elements

of the patient’s history and nd-

ings from the physical examination

would suggest the need for diag-

nostic laboratory studies?

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against

obtaining laboratory tests to assess for inammatory disease in patients with

sacroiliac joint pain.

Grade of Recommendation: I

Diagnosis Question 7. In patients

with low back pain, are there

specic ndings on a pain diagram

that help dierentiate the struc-

ture which is causing pain?

Diagnosis Question 8. Are there

assessment tools or question-

naires that can help identify the

cause of acute, subacute or chron-

ic low back pain?

A systematic review of the literature yielded no studies to adequately ad-

dress these questions.

Diagnosis Question 10. Are there

history and physical examination

ndings that would warrant ob-

taining advanced imaging studies?

A systematic review of the literature yielded no studies to adequately ad-

dress this question.

Work Group Consensus Statement:

In the absence of reliable evidence supporting an absolute indication for

advanced imaging based upon history and physical examination in the specif-

ically-dened patient population, it is the work group’s opinion that, in pa-

tients with severe and intractable pain syndromes who have failed medical/

interventional treatment, advanced imaging may be indicated. Subgroups of

patients have been shown to have a higher or lower incidence of radiograph-

ic abnormalities based upon acuity of low back pain, tenderness to palpation

and provocation maneuvers; however, the utility of these ndings in guiding

treatment is not clear.

Imaging

Imaging Question 1. What is the

association between low back pain

and spondylosis on routine radiog-

raphy?

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against an

association between low back pain and spondylosis using routine radiogra-

phy.

Grade of Recommendation: I

Imaging Question 2. Is there evi-

dence to support the use of com-

puted tomography (CT) or mag-

netic resonance imaging (MRI) for

the evaluation of low back pain in

the absence of x-ray/radiographic

abnormality?

A systematic review of the literature yielded no studies to adequately ad-

dress this question.

Imaging Question 3. In patients

with low back pain, does duration

of symptoms correlate with abnor-

mal ndings on imaging?

A systematic review of the literature yielded no studies to adequately ad-

dress this question.

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Summary of Recommendations

20

Imaging Question 4. What is the

optimal imaging protocol that

should be used in the setting of

low back pain?

4a. Are unique MRI sequences con-

sidered preferential or optimal?

There is insucient evidence that unique magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

sequences can be considered preferential or optimal.

Grade of Recommendation: I

4b. What is the history and clinical

presentation that suggests the use

of contrast enhanced imaging in

patients with low back pain?

A systematic review of the literature yielded no studies to adequately ad-

dress this question.

4c. Is there evidence to support im-

aging the lumbar spine in an oblique

plane?

A systematic review of the literature yielded no studies to adequately ad-

dress this question.

4d. What is the value of exion/

extension lms in evaluating lower

back pain?

A systematic review of the literature yielded no studies to adequately ad-

dress this question.

Imaging Question 5. In the ab-

sence of red ags, what are the

imaging (x-ray, CT or MRI) recom-

mendations for patients with acute

or chronic low back pain?

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against ob-

taining imaging in the absence of red ags.

Grade of Recommendation: I

Imaging Question 6. Are there im-

aging ndings that correlate with

the presence of low back pain?

There is insucient evidence for or against imaging ndings correlating with

the presence of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: I

Imaging Question 7. Are there

imaging ndings that contribute

to decision-making by health care

providers to guide treatment?

There is insucient evidence to determine whether imaging ndings contrib-

ute to decision-making by health care providers to guide treatment.

Grade of Recommendation: I

Medical and Psychological Treatment

Med/Psych Question 1. Is smoking

cessation eective in decreasing

the frequency of low back pain

episodes?

A systematic review of the literature yielded no studies to adequately ad-

dress this question.

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Summary of Recommendations

21

Med/Psych Question 2. In patients

with low back pain, is pharmaco-

logical treatment eective in de-

creasing duration of pain, decreas-

ing intensity of pain, increasing

functional outcomes of treatment

and improving the return-to-work

rate?

Versus:

a. No treatment

i. Risks

ii. Complications

b. Cognitive behavioral therapy

(CBT) and/or psychosocial inter-

vention alone

c. Patient education alone

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the

use of anticonvulsants for the treatment of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: I

Antidepressants are not recommended for the treatment of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: A

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the

use of Vitamin D for the treatment of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: I

Non-selective NSAIDs are suggested for the treatment of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: B

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the

use of selective NSAIDs for the treatment of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: I

It is suggested that the use of oral or IV steroids is not eective for the treat-

ment of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: B

It is suggested that the use of opioid pain medications should be cautiously

limited and restricted to short duration for the treatment of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: B

Med/Psych Question 3. In pa-

tients with low back pain, is topical

treatment (eg, cream or gel) ef-

fective in decreasing duration of

pain, decreasing intensity of pain,

increasing functional outcomes

of treatment and improving the

return-to-work rate?

There is insucient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the

use of lidocaine patch for the treatment of low back pain.

Grade of Recommendation: I

Topical capsicum is recommended as an eective treatment for low back

pain on a short-term basis (3 months or less).

Grade of Recommendation: A

Med/Psych Question 4. Following

treatment for low back pain, do

patients with healthy sleep habits

experience decreased duration of

pain, decreased intensity of pain,

increased functional outcomes

and improved return-to-work rates

compared to patients with poor

sleeping habits?

A systematic review of the literature yielded no studies to adequately ad-

dress this question.

Recommendations were developed based on a specic denition, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the resulting literature which excluded conditions

such as presence of a neurological decit or leg pain experienced below the knee, among others. Given the exclusion criteria, these guideline rec-

ommendations address a subset of low back pain care as opposed to low back pain in its entirety. This clinical guideline is not intended to be a xed

treatment protocol; it is anticipated that there will be patients who require more or less treatment than what is outlined. This clinical guideline should

not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same

results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specic procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances

presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution.

Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain | Summary of Recommendations

22

Med/Psych Question 5. In patients

with low back pain, is cognitive

behavioral therapy (CBT) and/or

psychosocial intervention and/or

neuroscience education eective

in decreasing duration of pain, de-

creasing intensity of pain, increas-

ing functional outcomes, decreas-

ing anxiety and/or depression and

improving return-to-work rate?

Cognitive behavioral therapy is recommended in combination with physical

therapy, as compared with physical therapy alone, to improve pain levels in

patients with low back pain over 12 months.

Grade of Recommendation: A