Southern Illinois University Carbondale

OpenSIUC

Research Papers Graduate School

Spring 4-13-2009

Spiritually Sensitive Psychological Counseling: A

History of the Relationship between Psycholgy and

Spirituality and Suggestions for Integrating em in

Individual, Group, and Family Counseling

James B. Benziger

Southern Illinois University Carbondale, BradBenziger@yahoo.com

Follow this and additional works at: hp://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp

is Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by

an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected].edu.

Recommended Citation

Benziger, James B., "Spiritually Sensitive Psychological Counseling: A History of the Relationship between Psycholgy and Spirituality

and Suggestions for Integrating em in Individual, Group, and Family Counseling" (2009). Research Papers. Paper 1.

hp://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/1

SPIRITUALLY SENSITIVE PSYCHOLOGICAL COUNSELING:

A HISTORY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PSYCHOLOGY AND

SPIRITUALLITY AND SUGGESTIONS FOR INTEGRATING THEM IN

INDIVIDUAL, GROUP, AND FAMILY COUNSELING

by

Brad Benziger

Bachelor of Arts in English Literature

A Research Paper Submitted in Partial

Fulfillment of the Requirements for the

Degree of Master of Science in Education

Graduate Program in Counselor Education

Department of Educational Psychology

in the Graduate School

Southern Illinois University

Carbondale

May 2009

AN ABSTRACT of the RESEARCH PAPER of

Brad Benziger for the Master of Science in Counseling Degree in Educational

Psychology, presented April 10, 2009, at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale.

TITLE: Spiritually Sensitive Psychological Counseling: A History of the Relationship

between Psychology and Spirituality and Suggestions for Integrating Them in Individual,

Group, and Family Counseling

MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. Lyle White

The purpose of this study was to research the history of the relationship between

the scientific view of psychology and spiritual one in the West from Plato to the present;

to determine how and why the two views separated; and to explore ways to combine both

in counseling.

i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express my deep gratitude and admiration to Dr Lyle White, my advisor

on this research paper. I was concerned that he would not approve this undertaking, that

he might think it was too much or insufficiently evidence based. He approved it and with

his knowledgeable questions, he pushed me to go deeper and learn more than I had

imagined possible.

I also wish to thank Dr Gail Mieling, who was both my first and my last teacher at

Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, and who encouraged me from the start. She has

been my mentor as both a teacher and as my practicum and internship supervisor.

I wish to thank my father, James George Benziger (1915 – 1996) for introducing

me to God in nature, and my mother Patricia Rey Benziger (1917 – 2006) for introducing

me to God in people.

ii

DEDICATION

This paper is dedicated to my ex-wife Georgann Sketoe Benziger, who read some

of the chapters and made helpful suggestions, to my sons Ross and George Benziger, and

to my best friend Rebecca Dougan. I treasure you all.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Chapter I Introduction 1

Chapter II The History of the Relationship Between

Spirituality and Psychology from Plato to the Enlightenment 7

1. Socrates and Aristotle 7

2. Jesus 12

3. The Printing Press and the Reformation 15

4. Francis Bacon 17

5. Immanuel Kant 25

6. Auguste Comte 29

Chapter III The Relationship between Spirituality and Psychology from

the Birth of the Science of Psychology to Freud and Jung 31

1. Monism 32

2. Charles Darwin 33

3. Wilhelm Wundt 41

4. William James 43

5. Freud and Jung 51

Chapter IV The Relationship Between Spirituality and Psychology

in the 20

th

Century: Psychiatry, Behaviorism, Cognitive

and Social Psychology 59

1. Psychiatry 59

2. Behaviorism 61

iv

3. Cognitive Psychology 62

4. Kübler-Ross 63

5. Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy 64

6. Social Psychology 68

7. The Milgram Obedience Experiment 69

8. The Zimbardo Prison Experiment 71

9. My Lai 74

10 Conclusions 78

Chapter V The Relationship Between Spirituality and Psychology

in the 20

th

Century: Humanistic Psychology 80

1. Carl Rogers 80

2. Abraham Maslow 90

3. Transpersonal Psychotherapy 94

4. The Process of Humanistic Psychotherapy 95

5. The Goals and Values of Humanistic Psychotherapy 96

Chapter VI The Relationship Between Spirituality and Psychology

in the 20

th

Century: Existential Psychology 97

1. Husserl and Phenomenological Psychotherapy 98

2. Heidegger and Ontology 99

3. Martin Buber 103

4. Ludwig Binswanger 104

5. Erich Fromm 109

6. Viktor Frankl 113

7. Rollo May 116

v

8. Emmy van Deurzen 124

9. The Process of Existentialist Psychotherapy 126

10. The Goals and Values of Humanistic and Existentialist

Psychotherapy 127

11. Conclusions 132

Chapter VII Group and Family Counseling 135

1. Group Counseling

A. Group Work and Spirituality 135

B. Group Types 138

C. The History of Group Counseling 139

D. Carl Rogers and Groups 140

E. Process-focused Groups 142

F. Facilitator-participant: Equality and Dialogue in Groups 144

G. Groups and Native Americans 146

2. Family Counseling

A. Family and Spirituality 147

B. Family Therapists’ Attitudes and Beliefs 148

C. Satir and Authentic Communication 150

D. Bowen and the Well-differentiated Self 150

E. Challenges to Integrating Spirituality and Family

Counseling 152

F. One Possible Spiritual-Psychological Approach

to Family Counseling 154

3. Conclusions 166

vi

Chapter VIII Contemporary Theories that Combine

Spirituality and Psychology 168

1. Alcoholics Anonymous 169

2. Pastoral Counseling 179

3. Jung and Jungians 188

4. Developmental Counseling and Therapy 200

5. Conclusions 209

Chapter IX The True-Self 210

1. Object-Relations Theory 211

2. Carl Rogers 212

3. Carl Jung 213

4. Alice Miller 213

5. Roberto Assagioli 219

6. The True-Self as Part of a Spiritual-Psychological

Approach to Therapy 224

Chapter X The Spiritual Value of Sadness and Pain 225

1. The Value of Negative Experiences 226

2. Elio Frattaroli and a Falling Down that is Good 234

3. The Meaning of Pain 241

Chapter XI The Spiritual Value of Creativity, Conflict, and Immorality 245

1. The Value of Creativity 245

2. Constructive Conflict 245

3. Revolution 246

vii

4. Anger and Justice 247

5. Knowledge, Experience, Truth, and the True-self 250

6. Moral Deliberations and Outcomes 251

7. Existentialist Psychology’s View of Good and Evil 252

8. Evolutionary Psychology’s View of Morality 252

9. C. S. Lewis’s View of Morality 256

10. The Meaning of Immorality 262

11. A Spiritually Sensitive Approach to Morality in Counseling 262

12. Conclusions 264

Chapter XII Spiritual Health and Development 267

1. Spiritual Health Differs from Traditional

Psychological Definitions of Mental Health 267

2. Spiritual Development Differs from Traditional

Psychological Conceptualizations of Development 269

3. Spiritual Dimensions of Growth 272

4. Conclusions 284

Chapter XIII Research regarding Spirituality 286

1. Spirituality’s Correlation with Physical and

Psychological Wellness 286

2. The Meaning of Spirituality for Clients 289

3. Counselor Attitudes toward Spirituality 289

4. Demographics Relevant to a Spiritual-Psychological

Approach to Counseling 290

5. Conclusions 291

viii

Chapter XIV What I as a Counselor Have Learned from Studying the History

of the Relationship between Psychology and Spirituality 293

Research Question 1: What is the history of the relationship between

the spiritual worldview of psychology and the scientific? 294

Question 2(a): Were the scientific and spiritual views of the world

ever the same? 294

Question 2 (b): When did the scientific and spiritual views diverge? 297

Question 2 (c): What did those who held a spiritual world-view think

of those who held a scientific world-view, and vice versa? 297

Question 2 (d): Does antagonism toward religion still

dominate psychology? 298

Question 2 (e): Is the science of psychology becoming more

open to the value of spirituality? 299

Question 3 (a): What, if anything, is missing from the spiritual view

that the scientific view contributes? 299

Question 3 (b): What, if anything, is missing from the scientific view

that the spiritual view includes? 301

Question 4: Are there approaches to the study and practice of psychology

that include both the scientific and the spiritual perspectives? 303

Future Prospects for the Relationship between Spirituality and Psychology 305

Chapter XV What I Learned regarding Values and Morals in Counseling 307

Research Question 5: What are spiritual values? 307

ix

Question 6: In the practice of psychotherapy, are the spiritual and the

scientific views of human beings (a) cooperative; or

(b) complementary and supportive; or (c) distinct and

non-overlapping; or (d) at odds; or does that answer depend

on the client, the context, and the problem? 308

Moral Deliberations in Counseling as a Precursor

to Spiritual Development 314

A Binocular, Four-Dimensional Perspective 319

Conclusions 320

Chapter XVI: How I Reconciled the Spiritual and Scientific

Worldviews in my Approach to Counseling 322

1. The Nine Spiritual Competencies 323

2. Carl Rogers and Person-centered Counseling 327

Research Question 7: Is there a way to combine the spiritual and

scientific worldviews in one approach to counseling that,

based on my research, class work, and experience, I feel

comfortable recommending to clients? 337

Chapter XVII: A Spiritually Sensitive Person-Centered Approach to Counseling 339

1. Spiritually Sensitive Person-centered Counseling’s

View of the Client 340

2. The Values, Goals, and Results of Spiritually

Sensitive Person-centered Counseling 342

3. Spiritually Sensitive Person-centered Counseling’s

x

View of the Therapist/Counselor 349

4. Spiritually Sensitive Person-centered

Counselor Brian Thorne 350

5. Content vs. Process 354

6. The Process of Spiritually Sensitive

Person-centered Counseling 354

7. Spiritually Sensitive Person-centered

Group Counseling 365

8. Conclusions 370

Chapter XVIII: Concluding Thoughts: Looking Backward and Forward 371

References: 375

Appendix 1: Client-Counselor Service Agreement for

Spiritually Sensitive Person-Centered Counseling 407

Appendix 2: Permissions Received to Include Copyrighted Materials 417

Vita 419

xi

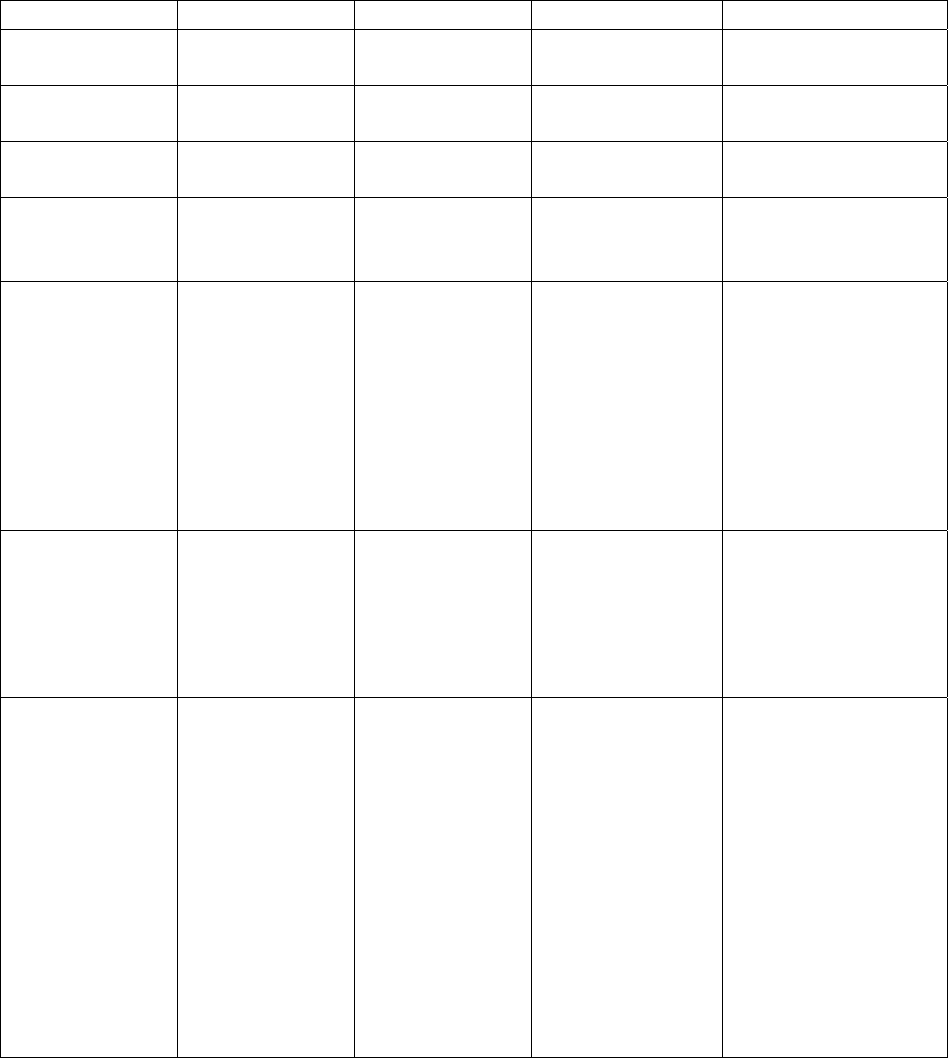

LIST OF TABLES

Page

Table 1 Forms of Verbal Interaction from Benner and Gouthro 183

Table 2 Comparison of Developmental Theories Used in

Developmental Counseling and Therapy 204

Table 3 The Seven Research Questions 293

Table 4 Materialistic Assumptions Compared to Spiritual Possibilities 302

Table 5 Values of Traditional Psychotherapy compared to Values

of Soul Care 313

Table 6 Spiritual Beliefs Common in the West 347

Table 7 Spiritual Beliefs Less Common in the West 348

xii

xiii

LIST OF FIGURES

Page

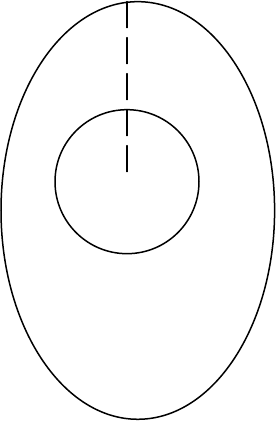

Figure 1 Circular Causality in Families 154

Figure 2 Assagioli’s Diagram of the Personality 221

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

When I first attended college in the 1960s, I was interested in psychology and

would have pursued it as a career but for the fact that psychology then looked at the

world principally through the lens of radical behaviorism or the lens of Freudian

psychiatry. Those lenses seemed too limiting to me. I believed in God and in the reality

of the soul. Freud and behaviorism made no allowance for either.

I thought then that I would not be in a position to integrate spiritual and scientific

concerns in counseling unless I became a minister or priest. I considered taking that path,

but decided against it; because, like counseling psychologist Carl Rogers (Thorne, 1992),

I did not want to tell others how to act, and because, like the 14

th

Dalai Lama, I did not

think it is necessary to believe in God or in any religion to be a good or spiritual person

(Iyer, 2008). In the 1960s, three of the most influential voices in psychology were

atheists: Freud, Skinner, and Ellis. In A Philosophy of Life (1933), Freud had argued that

God is a projection of a childish wish for protection from a cruel and uncertain world.

Religion, he wrote, is a “serious enemy” (p. 219) of the scientific Weltanschauung and a

“neurosis which the civilized individual must pass through on his way from childhood to

maturity” (p. 230). Behaviorist B. F. Skinner was an outspoken atheist who resented the

fact that he had had to attend daily chapel at Hamilton College in upstate New York as an

undergraduate (Boeree, 2008; B. F. Skinner, AllPsych On Line, 2008). In the article

Psychotherapy and Atheistic Values: A Response to A. E. Bergin’s “Psychotherapy and

Religious Values” (1980), psychologist Albert Ellis reiterated the view that, according to

Koenig, Larson, and Larson (2001), was then common in the mental health field that,

2

“the less religious they [people] are, the more emotionally healthy they will tend to be”

(Ellis, 1980, p. 637). In that intellectual climate, most psychologists did not consider

whether of not it is possible to integrate the spiritual and scientific perspectives in the

practice of psychotherapy, or how to do it.

I became a lawyer instead. Lawyers are ethically bound to do their best to obtain

whatever end their clients seek, even if that end is wrong by every independent standard.

Thus, acts and statements that would be immoral in any other profession are considered

right in the practice of law. I was never comfortable with that; so, in 2004, when my

children were grown, I returned to college and entered the Master’s program in Marital,

Couple, and Family Counseling at Southern Illinois University. When I obtain my

degree, I will have trained as an individual counselor, a group counselor, and as a family

and couples counselor. Almost all my training will have been in theories of counseling

that do not mention spirituality. No such classes are available at this university, and such

classes are not available at most public universities (Tisdell, 2003). Nonetheless, when I

graduate and begin work as a counselor, I hope to offer counseling that is both informed

by scientific research and sensitive to my clients’ spirituality. Thanks to the open-

mindedness, encouragement, and knowledgeableness of my advisor, Dr. Lyle White, I

have been able to undertake this paper, which is intended to serve as a foundation for that

counseling and as a source for others who have similar questions.

In this paper I will attempt to answer seven questions about the relationship

between the scientific view of psychology and the spiritual view:

(1) What is the historical relationship between the spiritual and the scientific

views of psychology?

3

(2) Were the scientific and the spiritual views of human beings ever the same? If

they diverged, when did they diverge? What was the nature of that separation: how did

each view the other? Does antagonism toward religion still dominate psychology, or is

the science of psychology becoming more open to the value of spirituality?

(3) What, if anything, was missing from the spiritual view that the scientific view

contributed? What, if anything, was missing from the scientific view that the spiritual

view included?

(4) Are there recognized approaches to the study of psychology and the practice

of psychotherapy that include spiritual perspectives and values? If so, how do those

approaches differ from scientific psychology?

(5) What are spiritual values? How do they differ, if at all, from materialistic,

scientific values? What are the possible goals for the client in spiritually based

counseling? How do those differ, if at all, from the goals of approaches to therapy that are

considered scientific?

(6) In psychotherapy, are the spiritual and the scientific views of human beings

(a) cooperative; or (b) complementary and supportive; or (c) distinct and non-

overlapping; or (d) at odds; or does that answer depend on the client, the context, and the

problem?

(7) Is there a way to integrate the scientific view of human beings with the

spiritual view in the practice of psychotherapy? Is it possible to design an approach that

clients will feel good about regardless of their spiritual beliefs?

I could have added an eighth question: What is spirituality? To avoid debate,

William James began The Varieties of Religious Experience by defining “religion” to

4

mean: “the feeling, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as

they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine”

(1902/2004, p. 39). I will follow his example but not his wording. For the purpose of this

study, I define, “spirituality” to mean “the recognition of the possibility and importance

of a realm of existence that is not material but is real.”

I found only three chapters in three books that addressed the historical

relationship between the spiritual and the scientific views of psychology: two chapters of

42 pages in Richards and Bergin’s A Spiritual Strategy for Counseling and

Psychotherapy (2005); one chapter of 28 pages in Miller’s Integrating Spirituality into

Treatment (1999); and one chapter of 24 pages in Miller and Delaney’s Judeo-Christian

Perspectives on Psychology (2005), for a total of less than 100 pages. In preparation for

writing this paper, I read Hunt’s The Story of Psychology (1993). It is 735 pages long. It

contains no chapter on the relationship between spirituality and psychology. Hunt largely

ignored the spiritual side of important psychologists, like James and Jung. If a

psychological theorist considered spiritual questions, Hunt portrayed that as a threat to

the progress of the science of psychology. This paper could serve, among other things, as

a spiritual companion to Hunt’s book. Because there is so little existing literature

addressing question (1), I have reported what I learned about the history of the

relationship between spirituality and psychology in depth, so that each reader of this

paper can answer each of these seven questions for herself or himself, and so that I can

return to this paper from time to time and reflect in tranquility on what my research

found.

5

In order to answer these seven questions, I will compare the spiritual with the

non-spiritual world-view throughout history. I will begin in Chapters 2 and 3 by

examining the relationship between spirituality and psychology from Plato to the birth of

psychotherapy. In Chapters 4, 5, 6, and 7, I will examine their relationship in the 20

th

Century and today: Chapter 4 will discuss psychiatry, behaviorism and cognitive and

social psychology; Chapters 5 and 6 will consider humanistic and existentialist

psychology; and Chapter 7 will address group and family counseling.

In Chapter 8, I will examine four contemporary approaches to counseling that

combine spirituality and psychology: Alcoholics Anonymous, pastoral counseling,

Jungian psychology, and developmental-wellness counseling, and I will compare each of

them to traditional, non-spiritual psychology. In Chapter 9, I will discuss the meaning of

the true-self, a concept that may be the closest traditional psychology comes to the idea of

a soul.

In Chapters 10 and 11, I will consider values that are missing from contemporary,

scientific psychology since it has attempted to separate itself from spiritual concerns. In

Chapter 12, I will compare spiritual health and development to scientific

conceptualizations of health and development.

Although Freud and Ellis thought of themselves as scientists, their assertions in

1933 and 1980 that God and religion are unhealthy were presented with no supporting

data. In Chapter 13, I will discuss recent research, which has shown a correlation between

spirituality, on the one hand, and mental health and longevity, on the other. It would have

been nice to compare research regarding the effects of spiritually based approaches to the

6

effects of traditional methods of psychotherapy from Freud to the present. But no such

research existed until recently. I found such research only from 1995 to the present.

In Chapters 14 and 15, I will summarize the answers I found to the research

questions. In Chapter 16, I will describe how, in light of my research, I was able to

reconcile the scientific worldview with the spiritual worldview in counseling. In Chapter

17, I will describe one possible integrated approach to spiritual-psychological counseling

that includes care for the spirit, soul, mind, and body, within the individual and in

relationship with others, in a way that respects the client’s worldview and is, therefore,

most likely to help the client. In Chapter 18, Concluding Thoughts, I look back to see

how well the seven research questions have served their purpose in arriving at an

approach to counseling that is sensitive to both worldviews.

In this paper I will focus on the Western philosophies and religions because I am

better acquainted with them. Inevitably I will omit many theorists, and I may interpret

some in ways that others will not agree with. Not everyone will agree with the answers I

arrive at to these seven questions. Not everyone will agree with the approach I suggest to

spiritual-psychological counseling. I look forward to learning from those who disagree as

well as from those who agree. I will continue to adapt my counseling approach to

feedback from clients and colleagues when this paper is done.

7

CHAPTER II

THE HISTORY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SPITIRTUALITY

AND PSYCHOLOGY FROM PLATO TO THE ENLIGHTENMENT

From the Ancient Greeks to Jesus

According to Hunt (1993), at the time of Homer’s Iliad, in the ninth century B.C.,

there was no word for human consciousness. “Psyche” meant merely “breath.” Ancient

Greeks believed that the gods put thoughts and emotions into human minds. Homer

envisioned an afterlife, but it was dreary and pointless. When Odysseus traveled to the

underworld, Achilles told him:

Rather I’d choose laboriously to bear

A weight of woes, and breathe the vital air

A slave to some poor hind that toils for bread

Than reign the sceptered monarch of the dead.

(Homer, p. 412)

In the Iliad and the Odyssey and in the first books of the Old Testament, few

boundaries existed between the human world and the spiritual world. The gods of ancient

Greece symbolized all the strengths and weakness of humankind, but were often

indifferent to the fate of individual humans. The one God of ancient Israel was

authoritarian and supported his chosen people in battle, although they were often

ungrateful and disobedient (Armstrong, 1994).

Socrates and Aristotle

By the time of Socrates (469 -- 399 B.C.), Plato (427 -- 347), and Aristotle (384 –

322), humans were considered to be conscious beings who could think for themselves.

8

“Psyche” now meant “soul” or “spirit,” although in Ancient Greece, there was no concept

of psychology and no word for it. Until the 1800's, psychology would remain a part of

philosophy. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle no longer deemed thoughts to come from the

gods. They developed contrasting theories regarding the origin of thoughts. Socrates and

Plato believed that some knowledge is inborn, and that we learn by remembering and by

recognizing eternal truths, which exist independently of physical existence in ideal form.

They believed that we increase our knowledge by applying deductive logic to what we

already know. They thought that the five senses are unreliable and cannot be trusted to

accurately convey outer reality to the inner mind.

In contrast, Aristotle thought that humans only learn through the use of the five

senses plus a “common” sense, which recognizes that incoming information originates

from the same common source. He believed that humans are born as blank slates, with no

innate knowledge. Aristotle thought that the soul and body were inseparable and that the

continued existence of a personal soul after the death of the body was unlikely (Brennan,

2002; Durant, 1933, pp. 83 - 84). He thought that people gain reliable knowledge only by

gathering evidence and making inductive generalizations. In The Story of Philosophy,

Will Durant wrote that he was bothered with Aristotle’s insistence on logic:

He thinks the syllogism a description of man’s way of reasoning, whereas it

merely describes man’s way of dressing up his reasoning for the persuasion of

another mind; he supposes that thought begins with premises and seeks their

conclusions, when actually thought begins with hypothetical conclusions

and seeks their justifying premises, -- and seeks them best by the observation

9

of particular events under the controlled and isolated conditions of an experiment.

(Durant, 1926, pp. 101 – 102)

This “observation and experimentation” theory of knowledge would not be explicitly

expressed until Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626).

Socrates and Plato saw their view as antagonistic to Aristotle’s. After Plato’s

death, Aristotle was twice denied appointment as head of Plato’s Academy. So Aristotle

opened his own Lyceum. Plato thought that Aristotle’s view did not take account of the

true nature of human beings, and Aristotle thought Plato was a misguided mystic. Neither

man reached across the rift. Plato and Aristotle started out as friends and collaborators.

They became competitors. They could have continued as collaborators. Each one’s

worldview could have enriched and enlarged the other’s, instead of denying the validity

of the other’s. But the all-or-nothing antagonism that arose between them has continued

to characterize conflicting views of psychology to the present day. Both points of view

reflect important aspects of human experience. It is possible to bridge the rift. Aquinas

explicitly attempted to do so, but few other authors have. There were many commentaries

on Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, but, except for the teachings of Jesus, there was almost

no original psychological thinking in Europe for the next 2000 years.

The careers of Socrates and Plato coincided with the development of democracy

in Athens and with a dawning recognition of the value of the individual’s voice and life,

as dramatized by Euripides (480 – 406) in Women of Troy (415 B.C./2004). That play is

set at the conclusion of the Trojan War, as the women and children of Troy are about to

be taken away as slaves and concubines by the conquering Greeks. It is told

sympathetically from the point of view of the women, who object, to no avail. It was

10

produced during the Peloponnesian War, and is considered a likely commentary on the

capture of the Aegean island of Melos and the slaughter and subjugation of its populace

by the Athenians (The Trojan Women, Wickipedia, 2008).

Hippocrates (460 – 377), who represents a separate stream of thought from either

Socrates or Aristotle, is considered the father of modern medicine and thus of modern

psychiatry. His views endure in the naturalistic assumptions of present, scientific

psychology that all ills can be accounted for by natural causes. He lived on the Greek

island of Cos at about the same time as Plato and Aristotle. He is mentioned by name by

Socrates in Phaedrus; and he is thought to have visited Athens at least once. There is a

possibility that he was many people bearing the same name from generation to

generation. The father of medicine does not appear to have involved himself in the debate

between Plato and Aristotle. Had he been asked to, he probably would have sided with

Aristotle, because Hippocrates turned away from the idea that illnesses were caused and

could be cured by divine action. Instead he used observation of the body as a basis of

medical knowledge and treatment. Prayers and sacrifices did not hold the central place in

his theories. He taught that all diseases, including mental illnesses, had natural causes,

and he prescribed changes in diet, drugs, and keeping the body in balance, that is,

keeping the four humors in balance. The four humors or elements were blood, phlegm,

black bile, and yellow bile. The humors were not, in fact, the cause of anything; but the

idea that there were physical causes to all diseases was progress.

Aristotle taught that the ideal was to achieve happiness in this life by living

according to the golden mean. Socrates believed that there were more important things in

life than happiness. He valued truth over happiness, especially moral truth. He believed

11

that the most important things were to grow in wisdom and character, to figure out who

one was, and to be true to one’s self, even if that meant, as it did in his case, committing

suicide. Socrates and Plato believed in an immortal human soul that pre-exists our present

life and survives it. They thought that one’s place in the afterlife has something to do

with one’s development in this. They hoped that they would be with others whose

philosophical and moral development was similar to their own, and they believed that

their souls would be happy to escape the prison of this mortal, material existence.

Socrates and Plato were dualists: they believed that the soul and body are distinct and that

the soul is more important than the body.

After Socrates and Plato, happiness in this lifetime was the prime good of the

Pagan philosophers. The Epicureans sought happiness in moderation. The stoics sought

happiness by letting go of attachment to earthly things, which is comparable to Buddhism

without a soul. Galen (130 – 201 A.D.) sought to control the emotions through reason, an

idea comparable to today’s cognitive therapy. Although western languages developed

separate words for “spirit” and “soul,” e.g. the Latin words spiritus and animus, most

writers continued to make no distinction between them. One exception was the Egyptian

Neoplatonist Plotinus (205 – 270 A.D.) who experienced mystical trances in which he

saw reality existing at four levels: (1) the supreme level of the divine One; (2) the level of

Spirit, which includes the intellect and is a reflection of the One; (3) the level of the Soul,

which can look upward toward Spirit or downward toward nature and the world of the

senses; and (4) the world of physical reality (Hunt, p. 43).

12

From Jesus to the Enlightenment

Jesus

Jesus re-introduced and greatly expanded the idea that happiness is not the point

of life. Jesus asked people to love God, to love God’s children, and to grow in soul and

spirit while they live on this earth. Each one of these goals may entail failure and pain, as

it did for Jesus and his disciples. Jesus embodied the revolutionary psychological ideas of

loving your enemies, forgiveness no matter what, mercy, and equality. Jesus further

expanded the value of the individual voice and life. He indicated that he would leave the

whole flock to search for one lost sheep (Luke 154:7). He ate and drank with “sinners and

tax collectors” (Mark, 2:16) and, which was unusual for his time, with women as equals.

His disciple Paul wrote, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, neither free nor slave, neither

male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3: 28). Paul is credited

with recommending that wives be obedient to husbands, rather than their equal. These

passages have been uncritically accepted by as well educated a Christian as C. S. Lewis

(1952). Paul did not write all of the “Epistles of Paul,” and some of Paul’s strictures for

women are “best explained as a gloss introduced into the text by the second- or third-

generation Pauline interpreters who compiled the pastoral epistles” by which time there

was

a conscious effort to restrict the roles that women had played in the first-generation

Pauline churches (Hayes, 1997, p. 247). In Reading the Bible Again for the First Time:

Taking the Bible Seriously but Not Literally, theologian Marcus Borg wrote that the

“passages speaking of the subordination of women and wives are all found in letters most

likely not written by Paul” with a couple of possible exceptions (2001, p. 262). Paul

mentioned the names of 40 persons who were actively involved in his missionary

13

enterprise; of these, 16 were women (Koester, 1997). Paul had a great deal of patriarchic

culturalization to overcome. Borg pointed out, “Paul grew up in Tarsus, where women

wore the complete chadar in public, completely covering them from head to foot

(including their faces)” (2001, p. 262). For the first three centuries after Jesus’s death,

women actively sought an equal role in the Christian church. Eventually the Catholic

Church excluded women from the priesthood as it does today (Pagels, 1979).

Christianity added a new meaning to the word “spirit.” The Holy Spirit, Spiritus

Santus, descended on the disciples at Pentecost and is an aspect of the tripartite unity of

God. Many Christians believe that they receive the Holy Spirit at baptism and that they

can call upon the Holy Spirit when they have need. Many believe that they physically feel

when the Holy Spirit enters them.

After defeating the opposing army when his troops wore the sign of the cross on

their shields, Constantine (285 – 337 AD) converted to Christianity and signed the Edict

of Milan, which ended official persecution of Christians, and, sadly, marked the

beginning of a far greater persecution of Christians by each other (Kirsch, 2004). Kirsch

attributed the increased persecution to monotheism’s comparative closed-mindedness

toward differing beliefs. Constantine also began the “transformation of Christianity from

the religion of the oppressed to the religion of the rulers and of the masses manipulated

by them. . . . Christianity, which had been the religion of a community of equal brothers,

without hierarchy or bureaucracy, became ‘the Church,’ the reflected image of the

absolute monarchy of the Roman Empire” (Fromm, 1963, p. 60). Fromm attributed these

changes to the corrupting influence of power and to the human tendency to retreat from

the revolutionary consciousness of people like Jesus into the safety of obedience. He felt

14

that mentally healthy people are those who preserve their revolutionary awareness and

continue to question authority. Constantine convened the Council of Nicaea in 325 to

formally decide what Christians believe and what would go in the Bible. Thereafter, until

around 1600, European thought was expressed mostly by writers who saw themselves as

Christian and Catholic.

From early on, many Church writers have condemned sexual promiscuity and

some have condemned all sexual expression even in marriage. They drove the sexual side

of humans into the shadows where it has exerted enormous irrational power through the

present day. Sexuality is a side of spirituality that must be recognized and included in a

complete theory of spiritual-psychological counseling.

Many Christian writers were comfortable with the abstract ideals of Plato. They

did not, however, accept Plato’s belief in the pre-existence of souls. That belief was

declared heretical. Church writers admired Aristotle’s intellect but they rejected his call

for objective evidence. The Church was the final authority on what was true or not,

including the reality of miracles. Many believed, as did Augustine (354 – 430), that

whatever humankind has learned that is useful is already contained in the Scriptures

(Hunt). A reconciliation of Aristotle and the Catholic Church was accomplished by

Thomas Aquinas (1225 -- 1274). Aquinas attempted to prove the truths of doctrine,

including the existence of God, through reason. He established a two-part epistemology:

human-beings learn as much as they can through experience and reason, but when

revelation contradicts their experience and reason, they must accept revelation. He also

believed in the dualism between the body, on the one hand, and the soul or mind on the

other.

15

The Printing Press and the Reformation

Another giant leap forward in the value of the individual’s voice and life followed

the invention of moveable type and the printing press by Johann Gutenberg in the 15

th

Century. The first book he published, from 1454 to 1456, was a Latin Vulgate version of

the Bible; that is, it was entirely in Latin, with none of the original Greek. In 1522,

Martin Luther published his German translation of the New Testament. The Catholic

Church condemned the book and ordered it burned, on the grounds that laymen were not

qualified to read the Bible and interpret it. The Church would tell the laity what to think.

Luther is still referred to by the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia as “the leader of the

great religious revolt,” and Luther’s call for “a universal priesthood of all Christians” is

still termed a call for “anarchy” (2007), which, we are told, he regretted toward the end of

his life. To avoid anarchy, the Church was, at the time, burning people at the stake.

Luther founded Protestantism and his Bible formed the standard for the German

language. In 1604, King James appointed a committee of 50 clerics and scholars to write

an English translation of the Bible. In 1611, the King James Version of the Bible was

published. It, along with King James’s contemporaries, Shakespeare and Bacon, set the

standard for the English language (Nicolson, 2003).

The Reformation would have another unforeseen long-term effect. In Medieval

Europe, a Doctorate in Theology took 10 years to earn, far longer than a degree in law or

medicine (Principe, 2006). Theologians had schooling, knowledge, and authority. After

the Reformation, anyone could interpret scripture. Although there are still theologians

with schooling and knowledge in the 21

st

Century, they no longer have authority and their

work is unknown to most people.

16

If Gutenberg had wanted to publish a book on psychology, instead of the Bible, he

could not have done so, because the word did not yet exist. According to Hunt, the term

“psychologia” was first used by a Serbo-Croatian writer named Marulic in 1520. The

same term was used by the German writer Rudolf Goeckel in 1590. The word

“psychology” was first used in English in 1653. According to the Oxford English

Dictionary (2006) it originally meant “the study or consideration of the soul or spirit.” In

English, the “soul” was thought to be the immortal part of the mind. In Latin the words

animus and anima were used more or less interchangeably to mean either soul or mind,

except that “the rational principal in man” was usually connoted by the masculine form

animus, and only rarely by anima, the feminine form (Oxford Latin Dictionary, 1982;

Simpson, 1960). Latin contained the word spiritus, which also meant spirit or soul. Latin

does not appear to have distinguished between the meaning of spirit (spiritus) and soul

(animus/anima).

The Enlightenment

Will Durant commented that, after the death of Aristotle, “for a thousand years

darkness brooded over the face of Europe. All the world waited the resurrection of

philosophy” (1933, p.106). Durant dismisses stoicism and Epicureanism, the philosophies

of Imperial Rome, as the philosophies of masters or slaves, neither of whom could afford

to be overly sensitive. When the Roman Empire passed into the Papacy, “dogma, definite

and defined, was cast like a shell over the adolescent mind of medieval Europe.” Then

in the thirteenth century, all Christendom was startled and stimulated by Arabic

and Jewish translations of Aristotle; but the power of the Church was still

17

adequate to secure, through Tomas Aquinas and others, the transmogrification of

Aristotle into a medieval theologian. The result was subtlety, but not wisdom.

(Durant, 1933, p. 116)

Durant reviewed the progress made in astronomy, magnetism, and electricity in

the 1400s and the 1500s, and described what happened next:

As knowledge grew, fear deceased; men thought less of worshipping

the unknown, and more of overcoming it. Every vital spirit was lifted

up with a new confidence; barriers were broken down; there was no

bound now to what man might do. . . . It was an age of achievement,

hope and vigor; of new beginnings and enterprises in every field; an

age that waited for a voice, some synthetic soul to sum up its spirit and

resolve. (Durant, 1933, p. 117)

Francis Bacon

That voice, according to Durant, was Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626). Bacon did not

create a new philosophy. He created a new approach to knowledge. Bacon believed that

he was building on Aristotle. Aquinas had compromised Aristotle. For Aquinas, if divine

revelation contradicted evidence and logic, divine revelation won. For Bacon, the

priorities were reversed: science and objectively measurable knowledge came first.

Bacon believed that the thinking of Europe was stuck and that a new method was

needed to move civilization forward. That method consisted of observation and

experimental testing of inductive conclusions. Patience and hard work were necessary.

Falsification advanced knowledge as much as confirmation. Bacon believed that the most

important knowledge was knowledge that had a practical application.

18

In order to observe and induce well, it was necessary to clear the mind of all old

assumptions. In The Advancement of Learning (originally published 1603 – 1605), Bacon

warned of three obstacles or “distempers of learning.” These obstacles included

fantastical learning or vain imaginations: ideas that lacked any substantial foundation and

were professed mainly by charlatans, ideas such as astrology, magic, and alchemy. The

second obstacle was contentious learning or vain altercations. This refers to intellectual

endeavor in which the principal aim is not new knowledge but endless debate. The third

obstacle was delicate learning or vain affectations; this was the valuing of style over

substance. The three distempers had two faults in common: they demanded “prodigal

ingenuity” and they yielded “sterile results.” They wasted talent. What was needed was a

program to re-channel creative energy into socially useful new discoveries (Francis

Bacon, The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2007).

In Book II of De Dignitate (his expanded version of the Advancement) Bacon

outlined his scheme for a new division of human knowledge into three primary

categories: History, Poesy, and Philosophy. Concerning this classification The Internet

Encyclopedia of Philosophy said:

Although the exact motive behind this reclassification remains unclear, one of its

main consequences seems unmistakable: it effectively promotes philosophy – and

especially Baconian science – above the other two branches of knowledge, in

essence defining history as the mere accumulation of brute facts, while reducing

art and imaginative literature to the even more marginal status of “feigned

history.” Evidently Bacon believed that in order for a genuine advancement of

learning to occur, the prestige of philosophy (and particularly natural philosophy)

19

had to be elevated, while that of history and literature (in a word, humanism)

needed to be reduced. (2007, unpaginated)

In the Novum Organon (originally published in several parts from 1608 to 1620),

Bacon wrote that people must clear their minds of four errors, or “idols,” to which all

human thinking was prone. Those errors were: Idols of the Tribe, that is, fallacies that

were natural to all humans; Idols of the Cave, errors that were peculiar to particular

individuals due to the distortion of the light as refracted within their private caves; Idols

of the Marketplace, which arose from commerce and association among human beings;

and Idols of the Theatre, which came from past dogmas and philosophers. “These I call

Idols of the Theatre, because in my judgment all the received systems of philosophy are

but so many stage-plays, representing worlds of their own creation after an unreal and

scenic fashion” (quoted in Durant, 1933, p. 145). Idols of the Theatre were most likely to

be encountered in three types of philosophy: “sophistical philosophy” in which a

philosophical system is based on a few casually observed instances; “empirical

philosophy,” in which an entire system is based on a single key insight; and

“superstitious philosophy.” Concerning “superstitious philosophy,” The Internet

Encyclopedia of Philosophy said:

This is Bacon’s phrase for any system of thought that mixes theology and

philosophy. He cites Pythagoras and Plato as guilty of this practice, but also

points his finger at pious contemporary efforts, similar to those of Creationists

today, to found systems of natural philosophy on Genesis or the book of Job.

(2007, unpaginated)

20

By condemning “superstitious philosophy,” Bacon expressly discouraged

integration of the scientific and spiritual world-views. He criticized Plato and explicitly

continued the antagonism between the Platonic world-view and the Aristotelian; he put

science at odds with religion. From now on, literate Western thinkers would have to ask

themselves which side they are on. Some will see all attempts to mix religion and science

as attempts to infect learning with the disease of superstition and as threats to the

progress of the human race. In this paper, I will continue to look for thinkers who

accepted both world-views, and see if they can provide a model for integrating

spirituality and science in contemporary psychology, and especially in contemporary

psychotherapy.

Bacon coined the phrase “knowledge is power” and he helped invent the idea of

progress: the idea that human beings are engaged in a struggle with nature which they can

“win,” and that each victory marks a step forward. Bacon lived at a time when writers

were expected to make regular obeisance to queen (Elizabeth I) and king (James I) and

God. He bowed to all three, but most of his essays were practical, not metaphysical. He

discussed the existence of God briefly in Of Atheism, where he said:

I had rather believe all the fables in the Legend, and the Talmud and the

Alcoran, than that this universal frame is without a mind. . . . A little

philosophy inclineth a man’s mind to atheism; but depth in philosophy

bringeth men’s minds about to religion. For while the mind of man looketh

upon second causes scattered, it may sometimes rest in them and go no

further; but when it beholdeth the chain of them, confederate and linked

together, it must needs fly to Providence and Deity. . . . Atheism is in

21

all respects hateful, so in this, that it depriveth human nature of the means

to exalt itself, above human frailty. (Bacon, Of Atheism, 1597/2007)

Bacon did not address psychological questions. He did make aphoristic

observations about human nature and recommended observation and study of individuals

and society. He advocated studying everything, including magic, dreams, telepathic

communications, and psychical phenomena. Durant (1933) concluded:

His philosophical works, though little read now, “moved the intellects

which moved the world” [quoting Macaulay]. He made himself the eloquent

voice of the optimism and resolution of the Renaissance. Never was any man so

great a stimulus to other thinkers. (p. 156)

Bacon defined a quality of the scientific view that the spiritual view was missing: hard-

nosed realism and an objective search for knowledge, which lead to material progress.

The next major thinker who explicitly addressed psychological questions was

Descartes (1596 – 1650). Descartes was a rationalist who started by doubting everything.

He was also a nativist; that is, he believed that the mind produces ideas that are not

derived from external sources. He believed that the idea of God is innate. And he

believed in the dualism of the body and the mind/soul. He believed that the body and soul

are separate but that they interact. Descartes feared excommunication by the Catholic

Church, and therefore moved to Protestant Holland and then to Sweden. He avoided

excommunication, but caught pneumonia in the cold of a Swedish winter and died.

Next in the development of Western psychological thought came the English

empiricists. They lived in seventeenth and eighteenth century England where they were

able to write and publish despite the fact that Thomas Hobbes was an averred materialist

22

and suspected atheist, John Locke was an advocate of religious toleration, and David

Hume was an agnostic even on his deathbed. They were called empiricists not because

they conducted empirical experiments, but because they believed that human ideas arise

from each person’s empirical interactions with their environment. Hobbes (1588 – 1679)

had served as secretary to Francis Bacon (Durant, 1933, p. 157). He believed that reality

is material and that “soul” is only a metaphor. He was accused of being an atheist, but

denied it. He thought all ideas are the motion of atoms in the nervous system reacting to

the motion of atoms in the external world. Simple thoughts arise from experience, and

complex thoughts derive from simple ones by means of a train of ideas. In Leviathan

(1651) he advocated autocratic government, such as monarchy, because without a ruling

power to enforce civilized behavior, life is inevitably “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and

short.” He thought democracies were unworkable because humans are inherently fearful

and therefore dangerous. In a state of nature, Hobbes believed people would not

recognize any natural moral law. Things that we want we call “good;” things that we

dislike we call “bad.” Hobbes believed that “there is no naturally given hierarchy

amongst human beings and therefore everybody sees himself as having a natural right to

anything which he desires even when others want it too” (Thomas Hobbes, Thoemmes

Continuum, The History of Ideas, 2006). Without strong government, humans would

attack each other in pursuit of individual power. Humans seek power to fulfill their

selfish desires and to protect themselves from the anticipated aggression of others.

Hobbes believed that all humans are born equal and will try to gain unequal advantage.

John Locke (1632 – 1704) believed that all humans are born equal and have an

obligation as children of God to care for one another. Locke argued against the divine

23

right of Kings. His position is that legitimate rulers govern with the consent of the

governed. In An Essay Concerning the True Original Extent and End of Civil

Government (1690), Locke wrote:

The state of Nature has a law of Nature to govern it, which obliges every one, and

reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind who will but consult it, that being

all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty

or possessions; for men being all the workmanship of one omnipotent and

infinitely wise Maker; all the servants of one sovereign Master, sent into the

world by His order and about His business; they are His property, whose

workmanship they are made to last during His, not one another's pleasure. And,

being furnished with like faculties, sharing all in one community of Nature, there

cannot be supposed any such subordination among us that may authorize us to

destroy one another, as if we were made for one another's uses, as the inferior

ranks of creatures are for ours. Every one as he is bound to preserve himself, and

not to quit his station willfully, so by the like reason, when his own preservation

comes not in competition, ought he as much as he can to preserve the rest of

mankind, and not unless it be to do justice on an offender, take away or impair the

life, or what tends to the preservation of the life, the liberty, health, limb, or goods

of another. (Book II Chapter 2, Paragraph 6)

Locke thought that people have no innate ideas, that humans are blank slates, or

tabula rasa, at birth. People get their ideas from sensation and reflection. They combine

simple ideas to form complex ones. He thought that it is not possible to determine if mind

is entirely physical or if there is some “thinking immaterial substance” (Locke, Essay

24

Concerning Human Understanding, Bk IV, chap 3, para. 6, 1689). Locke thought that

the idea of God is not innate because some people do not have that idea. We derive our

idea of God from “the visible marks of extraordinary wisdom and power . . . in all the

works of creation” (Essay, Bk 1, chap 4, secs 8 -- 9). He believed that our ideas of right

and wrong are not innate because history shows such a range of moral judgment; and,

therefore, morality must be socially acquired. Although Locke’s style was prolix, his

impact on world thinkers, such as Thomas Jefferson, was immense. After Locke, it was

difficult for writers and speakers to assert that some humans were not of equal value to

some others, unless they defended that position.

Bacon’s optimism that humans could figure out the universe was vindicated by

the career of Isaac Newton (1642 – 1742). Simultaneously with Leibniz, Newton

invented calculus. Newton discovered the laws of gravitation, color, and the three laws of

motion, which until the 20

th

Century were thought, along with the laws of

thermodynamics and Maxwell’s equations relating to electricity and magnetism, to

explain the entire physical universe (Hirsch, Kett, & Trefil, 1993). Newton believed in

God and thought that there was no conflict between religion and science (Seeger, 1983).

Newton took for granted that both the physical and the spiritual realms were real; that

humans sought knowledge in both; that each realm shared its knowledge and cooperated

with the other. According to historian Lawrence Principe (2006), most scientists and

theologians shared this cooperative attitude until science asserted its professionalism and

separate identity in the 19

th

Century.

Rousseau (1712 – 1778) thought even better of human nature than Locke. He

believed that humans are basically good, but that society corrupts them. Rousseau’s ideas

25

inspired the French Revolution; Locke’s the American Revolution. The conflict between

those who think humans are innately selfish and untrustworthy, as Hobbes did, and those

who think that humans are prone to reason and prosocial conduct, as Locke and Rousseau

did, continues today in differing approaches to psychotherapy. Freud believed that

monsters from the id are barely held in check by the defense mechanisms of the ego and

by the autocratic demands of the superego. Carl Rogers, on the other hand, saw humans

as wanting to do the best thing, if given the opportunity. Rogers, whose ideas are

discussed extensively in this paper, was once called “the successor to Rousseau”

(by D. E. Walker in a letter to the Journal of Counseling Psychology, referenced with

refreshing candidness by Rogers himself in A Note on “The Nature of Man,” 1957).

David Hume (1711 – 1776) thought that the idea of soul was an “unintelligible

question” not worth discussing and the idea of an after-life was “a most unreasonable

fancy” (Hunt, 1993, pp. 84 - 85). He was an associationist. He examined ways in which

humans develop complex ideas through a chain of association of simpler ideas. Our

associations are based on resemblance, contiguity in time and place, and cause and effect.

He wrote that we assume causality because one thing customarily follows another, but we

can never prove actual cause and effect. The most we can prove is correlation. This

limitation remains a difficulty for psychology today. One of the first things I was taught

on returning to school to study psychology in 2000 was: Correlation does not equal

causation.

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (1724 -- 1804) suggested that we cannot know reality through

either pure reason as the rationalists and Platonists contended or from a purely empirical

26

approach since we can never be certain that our senses are providing us with a complete

and accurate picture of other people and things, or even of ourselves. Instead, we know

reality by synthesizing our perceptions. We do this by applying categories to our

experience. We see those categories in the world that our minds are built to recognize. If

our minds did not recognize these aspects of experience, we would stumble blindly.

Those categories are: (1) quantity: unity, plurality, and totality; (2) quality: reality,

negation, and limitation; (3) modality: possibility – impossibility, existence –

nonexistence, necessity – contingency, and (4) relation: inherence and subsistence,

causality and dependence, and community. These categories are not innate ideas. Kant

“argues that the mind provides a formal structuring that allows for the conjoining of

concepts into judgments, but that structuring itself has no content. The mind is devoid of

content until interaction with the world actuates these formal constraints. The mind

possesses a priori templates for judgments, not a priori judgments (Immanuel Kant, The

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2006). Kant said that these categories allow us to

learn, but they also limit what we can know and how we can know it. Kant’s cognitive

categories are similar to Jung’s archetypes, which are also forms devoid of content.

Jung’s ideas are discussed further in Chapters 3 and 8.

Kant arrived at a rule for right action based on pure reason, without resorting to

authority. His categorical imperative requires that we act as if the maxim of our action

will become, by our will, a universal law of nature. It requires us to relate to all humanity,

whether in our own person or that of any other, always as an end and never as a means.

Kant sensed that the human mind and spirit leap upward in an ascending trajectory of

development that seems aimed for a higher spot than our natural lifespan allows us to

27

attain. Based on this and on the existence of the moral categorical imperative, which he

thought most people feel within themselves, Kant argued for the existence of God and the

immortal soul as follows:

1. The summum bonum is where moral virtue and happiness coincide.

2. We are rationally obligated to attain the summum bonum.

3. What we are obligated to attain, it must be possible to attain.

4. If there is no God or afterlife, it is not possible to attain the summum

bonum.

5. God and the afterlife must exist.

(Moral Arguments for the Existence of God, Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy, 2008)

Kant did not consider this a proof that God does exist. He considered it a proof that there

is good reason to think that God may exist. “Kant was a highly religious person, but he

felt that morality should not be reliant upon God, but upon logic” (Mellilot, p. 1, 2008).

Kant did not, therefore, attempt to integrate the spiritual world-view with the

materialistic-scientific world-view as had Aquinas. Instead he attempted to construct an

independent system based on pure reason, which would serve humans whether

God exists or not.

Contemporaneously with Kant, the Englishman Jeremy Bentham (1748 – 1832)

developed the ethics of utilitarianism. Bentham advocated a quantitative utilitarianism,

including a hedonistic calculus. He urged lawmakers to use the greatest happiness of the

greatest number as their standard for enacting legislation. At that time, it was

revolutionary to suggest that legislators should consider any interest other than their own,

28

or their family’s, or the interests of their class, in making laws. John Stuart Mill was a

disciple of Bentham. In Utilitarianism (1887), Mill tried to make utilitarianism more

palatable by suggesting a qualitative hedonism whereby an unhappy philosopher was

deemed more valuable than a happy pig. This approach was criticized as logically

inconsistent. If one happiness is better than another, then that betterness would have to be

judged by some standard external to happiness.

Kant was critical of all utilitarians. He felt utilitarianism devalued individuals

because it would justify sacrificing one person for the benefit of others if the utilitarian

calculations predicted more benefit. Such a sacrifice would treat that person as a means,

not as an end. Happiness is contingent, unstable, and highly variable from individual to

individual. One could predict that certain acts would lead to happiness and that prediction

could turn out to be completely wrong. Therefore, Kant felt that reason was a better guide

to moral action and that the immediate result of moral action might well be unhappiness.

The true measure of a moral person is if that person acts morally when it does not come

naturally and does not lead to immediate good feelings. Kant felt that there are times

when our actions, or the actions of others, lead to immediate gratification but make us

uneasy nonetheless. That uneasiness is an indication that “our existence has a different

and far nobler end, for which, and not for happiness, reason is properly intended” (Kant,

Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals, 1785). Kant wrote, “morality is not

properly the doctrine of how we should make ourselves happy, but of how we should

become worthy of happiness” (Immanuel Kant, Wikiquote, 2008). Using reason as a

guide, in order to make moral choices, may not produce personal happiness, but it will

produce character and, perhaps, ultimately, some measure of contentment.

29

Despite these intellectual feats, Kant did not think that humans can know much

about the nature of reality based on the application of reason alone. He thought of himself

as a realist and a freethinker. He believed that “our knowledge is constrained to

mathematics and the science of the natural, empirical world [and that] it is impossible to

extend knowledge to the supersensible realm of speculative metaphysics” (Immanuel

Kant, The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2008). He urged science to free itself

from the dictates of external authority and to rely on evidence.

Auguste Comte

Auguste Comte (1798 -- 1857) is the founder of positivism, also known as logical

positivism, which contends that sense perceptions and logical inferences based thereon

are the only admissible basis of human knowledge. He was also the father of sociology, a

term that he coined. He influenced the thinking of 19

th

and 20

th

Century scientists. As

recently as 1959, Carl Rogers wrote that positivism “is settled dogma” in psychology

(Rogers, 1989a, p. 232). Comte wrote that the history of science shows that each science

passes through three successive stages: the theological, when humans use supernatural

explanations of events; the metaphysical, when human use abstract ideas and obscure

forces to explain events, such as occurred during the French Revolution, which he lived

through and saw as a disaster; and the positive stage, when the true causes of natural

events are explained scientifically.

Comte saw progress through these stages as inevitable and irreversible. If the

scientific attitude could be applied to all aspects of life, this would lead to a complete and

beneficial restructuring of the social order. Sociology would discover the laws of social

dynamics that would lead to these advances.

30

Thus, at the outset of the 19

th

Century, the century in which psychology was to

emerge as a science in its own right, leading thinkers in France, Germany, and England

were advocating a separation of science and religion similar to the constitutional

separation of church and state that exists in the United States. Once again, little interest

was expressed in seeking ways to combine the scientific and spiritual views of reality into

one comprehensive theory. In the next chapter, I will look at the birth of psychology as a

science and how that affected the relationship between psychology and spirituality in the

19

th

Century and the beginning of the 20

th

Century.

31

CHAPTER III

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PSYCHOLOGY AND SPIRITUALIY FROM

THE BIRTH OF THE SCIENCE OF PSYCHOLOGY THROUGH FREUD AND JUNG

In the first half of the 19

th

Century there was an explosion of research in the

physiology of the sense organs and perception, especially in Germany. Johannes Müller

(1801 – 1858) investigated the properties of optical and auditory nerves and their

connections to the brain. In the early 1830s at the University of Leipsig, Ernst Heinrich

Weber (1795 – 1878) measured just noticeable differences. He asked subjects to lift one

weight, and then to lift a second weight, and to say which was heavier. Weber showed by

experiment that the heavier the first weight, the greater the difference required in order

for a subject to perceive the difference. However the ratio between the greater and the

smaller weight remained a constant; that is, the magnitude of the weight of the first

stimulus divided by the magnitude of the second remained the same. Weber showed that

this held true for all stimuli, e.g. differences in the brightness of two lights and

differences in the pitch of two tones. This is known as Weber’s Law, and according to

Hunt, it was “the first statement of its kind – a quantitatively precise relationship between

the physical and psychological worlds” (Hunt, 1993, p. 114).

Herman von Helmholtz (1821 – 1894) studied under Müller and went on to

investigate perception in terms of the physics of the sense organs and nervous system. He

was the first to measure the speed at which an impulse travels along a nerve. He studied

how humans perceive colors. He theorized that humans learn primarily through trial and

error, rather than by applying inbuilt categories to our sensations. He demonstrated that

this was possible by having people wear glasses that made objects appear to be positioned

32

to their left. The subjects learned to reach to the left. When the glasses were removed,

they continued to reach to the left for a short period of time until their eyes and minds re-

adjusted.

Gustav Theodor Fechner (1801 – 1887) demonstrated that geometrical increases

in the strength of a stimulus were required to produce arithmetical increases in the

strength of the corresponding sensation. For example, “in terms of energy delivered to the

ear, an average clap of thunder is many times as powerful as ordinary conversation; in

terms of decibels – a decibel is the smallest difference in loudness the human ear can

recognize – it is only twice as loud” (Hunt, 1993, pp. 123 –124). Fechner showed that, for

all sensations, the relationship between the increase in the strength of the stimulus and the

increase in the sensation perceived follows a formula now called Fechner’s Law.

Objective measures of stimulus strength already existed. But human perceptions are

subjective. Therefore some had thought, including Kant, that they could not be

objectively quantified and measured. In order to measure the strength of human

perceptions, Fechner developed three methods (borrowing and perfecting two and

inventing a third) of measurement that are still used by experimental psychologists today.

Monism

In 1845, a group of young physiologists, including some students of Weber,

formed the Berlin Physical Society “to promote their view that all phenomena, including

neural and mental processes, could be accounted for in terms of physical principles”

(Hunt, 1993, p. 114). Until now, most thinkers who had considered the mind and the

body were dualists: they thought that the mind was qualitatively different from the body,

and that mind and body could not be studied in the same way. Many believed that the

33

mind is where the physical body and the eternal, non-physical soul meet. Thomas

Aquinas, for example, thought that some of our mental functions, such as the perceptions

of our senses, are handled by a physical, perishable part of our minds, but that the higher

functions of abstract and moral thought are handled by a part of the mind that is spiritual

and will survive our deaths. The German physiologists were monists; they thought that all

human life is physical and can be studied as such. The position of the monists was

strengthened by the publication of Darwin’s The Origin of Species (1859) and The

Descent of Man (1871/1998). Darwin claimed that The Origin of Species was based on

“Baconian principles” (Francis Bacon, The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2008).

For many 19

th

Century scientists, Darwin’s work confirmed that humans are physical and

animal and nothing more.

Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin (1809 – 1882) had studied divinity at Cambridge before

embarking on the Beagle. At that time he had believed in God and in the divinity of

Jesus. Over the course of his life, his beliefs changed. Darwin started The Origin of

Species (1859) with this quotation from Bacon:

“To conclude, therefore, let no man out of weak conceit of sobriety,

or an ill-applied moderation, think or maintain, that a man can search too far or be

too well studied in the book of God’s word, or in the book of God’s works;

divinity or philosophy; but rather let men endeavor an endless progress or

proficience in both.” Bacon: Advancement of Learning. (quoted in Darwin, The

Origin of Species, 1859/1915, vol. 1, p. xii)

34

When Darwin began The Origin of Species, he believed he was researching God’s works

and describing God’s laws. By its publication he was a self-declared theist; so the last

sentence of The Origin of the Species was: “There is grandeur in this view of life, with its

several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into

one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity,

from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been,

and are being evolved” (Darwin, The Origin of Species, vol. 2, 1859/1898, pp. 305 –

306). After the death of his daughter Annie, he lost faith in a beneficent God and by age

40 he was no longer a Christian. He continued to give support to the local church and to

help with parish work, but on Sundays he would go for a walk while his family attended

church (Charles Darwin’s views on religion, Wikipedia, 2007).

By 1873 he was an agnostic and remained an agnostic, but, at his own insistence,

not an atheist, until his death. The Autobiography of Charles Darwin was published

posthumously. Quotations about Christianity were deleted by Darwin's wife Emma and

his son Francis for the stated reason that the statements were deemed dangerous for

Charles Darwin's reputation. Only in 1958 did Darwin's granddaughter Nora Barlow

publish a revised version which reinstated the omissions. The revised Autobiography (C.

Darwin & N. Barlow, 1958) included the following statements:

I can indeed hardly see how anyone ought to wish Christianity to be true; for if so

the plain language of the text seems to show that the men who do not believe, and

this would include my Father, Brother and almost all my best friends, will be

everlastingly punished. And this is a damnable doctrine. . . .

35

The old argument of design in nature, as given by Paley, which formerly seemed

to me so conclusive, fails, now that the law of natural selection had been

discovered. We can no longer argue that, for instance, the beautiful hinge of a

bivalve shell must have been made by an intelligent being, like the hinge of a door

by man. There seems to be no more design in the variablity of organic beings and

in the action of natural selection, than in the course which the wind blows.

Everything in nature is the result of fixed laws. . . . (p. 87)

That there is much suffering in the world no one disputes. Some have attempted

to explain this in reference to man by imagining that it serves for his moral

improvement. But the number of men in the world is as nothing compared with

that of all sentient beings, and these often suffer greatly without any moral

improvement. A being so powerful and so full of knowledge as a God who could

create the universe, is to our finite minds omnipotent and omniscient, and it

revolts our understanding to suppose that his benevolence is not unbounded, for

what advantage can there be in the sufferings of millions of the lower animals

throughout almost endless time? This very old argument from the existence of

suffering against the existence of an intelligent first cause seems to me a strong

one; whereas, as just remarked, the presence of much suffering agreees well with

the view that all organic beings have been developed through variation and

natural selection.

At the present day the most usual argument for the existence of an

intelligent God is drawn from the deep inward conviction and feelings which are

experienced by most persons. But it cannot be doubted that Hindoos,

36

Mahomadans and others might argue in the same manner and with equal force in

favor of the existence of one God, or of many Gods, or as with the Buddists of no

God. . . .

Formerly I was led by feelings such as those just referred to, (although I

do not think that the religious sentiment was ever strongly developed in me), to

the firm conviction of the existence of God, and of the immortality of the soul. In

my Journal I wrote that whilst standing in the midst of the grandeur of a Brazilian

forest, 'it is not possible to give an adequate idea of the higher feelings of wonder,

admiration, and devotion which fill and elevate the mind.' I well remember my

conviction that there is more in man than the mere breath of his body. But now

the grandest scenes would not cause any such convictions and feelings to rise in

my mind. It may be truly said that I am like a man who has become colour-blind,