John Holahan and Michael Karpman

August 2019

AT A GLANCE

◼

Many adults are ambivalent about (neither support nor oppose) Medicare for All and other

proposals to expand health insurance coverage, though support for these proposals tends to be

greater than opposition.

◼

Young adults, nonwhite and Hispanic adults, those with low incomes, and those without private

health insurance are more likely to support than oppose Medicare for All. Those who neither

support nor oppose Medicare for All share many of these characteristics.

◼

Medicare for All supporters and opponents have different perceptions of how it will affect access

to care, with the perceptions of those who are ambivalent about the policy closer to those of

supporters.

◼

Medicare for All supporters cite universal health coverage and greater affordability as important

factors in their support. Higher taxes and concerns about wait times to see health care providers

and quality of care are more important to Medicare for All opponents.

Though support for the Affordable Care Act has grown in recent years,

1

ongoing concerns about

continuing affordability and coverage gaps, as well as political efforts to undermine the law or even

repeal it, have generated growing interest in single-payer plans, often known as Medicare for All.

Typically, a single-payer approach would establish a single government-run insurance plan in which the

entire US population would be enrolled; the costs associated with the coverage would be fully

government financed. Such approaches have been shown to significantly increase federal taxes

(Blahous 2018; Holahan et al. 2016; Liu and Eibner 2019),

2

but proponents argue that these costs would

H E A L T H R EFO R M M O N I T O R I N G S U R V E Y

What Explains Support for or

Opposition to Medicare for All?

2

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR O R O PP OS I TI O N TO M E DICA R E FO R ALL ?

be offset by eliminating employer and household premiums and cost sharing (Pollin et al. 2018).

Opponents raise concerns over access to and quality of care.

The Medicare for All approach was first given prominence in the 2016 presidential election cycle by

Senator Bernie Sanders; similar proposals have since been proposed or endorsed by several members of

Congress, including candidates competing for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination.

Given concerns about Medicare for All approaches, some propose incremental reforms. These

include increasing the Affordable Care Act’s premium and out-of-pocket cost subsidies and adding a

public plan option to all or some private insurance markets. These approaches would require smaller

increases in government revenues and be less disruptive but are less likely to achieve universal

coverage.

In this brief, we assess public support for both Medicare for All proposals and some incremental

reforms. We examine support for and opposition to Medicare for All among people with different

characteristics, as well as important factors to adults who support, oppose, or are ambivalent toward

Medicare for All.

What We Did

We used data from the March 2019 round of the Health Reform Monitoring Survey (HRMS), a

nationally representative, internet-based survey of nonelderly adults.

3

Approximately half of the 9,596

respondents who participated in the survey were randomly asked questions about whether they would

support, oppose, or neither support nor oppose four approaches for expanding health insurance

coverage. The questions were presented to respondents in a randomized order. The four approaches

were

1. making health insurance coverage more affordable by increasing the amount of subsidies to

lower the premiums and out-of-pocket costs for some health insurance plans,

2. giving all Americans the option of enrolling in a government-run health insurance plan that

would be similar to Medicare (i.e., a “public option”),

3. enrolling all Americans in a single government-run health insurance plan that would be similar

to Medicare as part of a new national health insurance program (i.e., Medicare for All), and

4. enrolling all Americans in either a government-run plan that would be similar to Medicare or a

private health insurance plan as part of a new national health insurance program.

4

The 4,793 respondents who were asked these questions were then randomly assigned to questions

designed to collect additional information about their perceptions of Medicare for All. These questions

focused on

◼

perceptions about whether the respondent’s access to care would be better, about the same, or

worse under Medicare for All;

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR OR OP P O S I TI ON T O M E DICA R E FO R AL L ?

3

◼

perceptions about whether the respondent’s out-of-pocket health care costs, premiums, and

federal taxes would be higher, about the same, or lower under Medicare for All; and

◼

factors that were important to the respondent in deciding whether to support Medicare for All.

We assessed support for all four approaches for expanding health insurance among all respondents

and by political party affiliation. We also examined support for Medicare for All by age, race/ethnicity,

educational attainment, family income as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL), census region,

and health insurance coverage at the time of the survey (i.e., private, public, and uninsured). We also

compared perceptions of how access to care and taxes would change and which factors were important

in deciding whether to support a national health insurance program among Medicare for All supporters,

opponents, and those who neither support nor oppose this approach.

Estimates of support and opposition to Medicare for All and other proposals to expand health

insurance coverage are not directly comparable to estimates from other polls, such as those conducted

by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, because of differences in the populations surveyed as well as

the response scales used in the survey questions. The HRMS included an option to select “neither

support nor oppose,” whereas other polls present a binary choice between support and opposition and

follow up to measure the intensity of that support or opposition. The inclusion of a neutral option in the

HRMS captures more ambivalence about Medicare for All and other proposals than would be suggested

by polls using a forced-choice approach, but does not fully capture weaker levels of support and

opposition.

What We Found

Many adults are ambivalent about (neither support nor oppose) Medicare for All and other proposals to expand

health insurance coverage, though support for these proposals tends to be greater than opposition.

Overall, about half of adults reported that they neither supported nor opposed increasing premium

subsidies, and a plurality neither supported nor opposed a public option, Medicare for All,

5

or a national

health insurance program including both private and public health insurance (table 1), suggesting

substantial ambivalence about these policies. That ambivalence may reflect uncertainty about the

policies or what they imply, given the relatively low levels of health insurance literacy among many

Americans (Long et al. 2014). Adults were more likely to support than oppose the two incremental

approaches (i.e., increased subsidies and the public option) and a national health insurance program

with both public and private insurance, but they were more evenly divided in their support for versus

opposition to Medicare for All.

4

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR O R O PP OS I TI O N TO M E DICA R E FO R ALL ?

TABLE 1

Support for Proposals to Expand Health Insurance Coverage among Adults Ages 18 to 64,

Overall and by Political Party Affiliation, March 2019

All adults

Democrat or

leans Democratic

Republican or

leans Republican

Increase subsidies to lower premiums and out-of-

pocket costs

Supports

30.3%

38.6%

20.9%***

Neither supports nor opposes

51.4%^^^

51.2%^^^

48.8%^^^

Opposes

16.5%^^^

8.4%^^^

28.6%^^^***

Give all Americans the option to enroll in a

government-run health plan (public option)

Supports

32.8%

42.3%

20.4%***

Neither supports nor opposes

45.0%^^^

45.7%

40.7%^^^***

Opposes

20.5%^^^

10.0%^^^

37.6%^^^***

Enroll all Americans in a single government-run

health plan (Medicare for All)

Supports

29.8%

42.3%

13.3%***

Neither supports nor opposes

40.7%^^^

43.5%

32.6%^^^***

Opposes

27.8%

12.3%^^^

52.8%^^^***

Enroll all Americans in a government-run or

private health plan as part of a new national

health insurance program

Supports

28.2%

38.3%

16.5%***

Neither supports nor opposes

46.2%^^^

48.3%^^^

38.8%^^^***

Opposes

24.1%^^

11.6%^^^

44.0%^^^***

Sample size

4,793

2,420

1,970

Source: Health Reform Monitoring Survey, quarter 1 2019.

Notes: Estimates not shown for adults whose political party affiliation is independent, undecided, other, or not reported (less than

5 percent of the sample), though these respondents are included in the estimates for all adults. Estimates not shown for the share

of adults (less than 2 percent) who did not report whether they supported or opposed each proposal.

*/**/*** Estimate differs significantly from adults who are Democrats or lean Democratic at the 0.10/0.05/0.01 level, using two-

tailed tests.

^/^^/^^^ Estimate differs significantly from share of adults who support the proposal at the 0.10/0.05/0.01 level, using two-tailed

tests.

Table 1 also shows the support by political party for various approaches designed to expand health

coverage. More than one-third (38.6 percent) of those who report being a Democrat or leaning

Democratic (hereafter collectively referred to as Democrats) supported increasing subsidies to reduce

premiums and out-of-pocket costs, versus 20.9 percent of Republicans or those who lean Republican

(hereafter collectively referred to as Republicans). On the other hand, 28.6 percent of Republicans

opposed this proposal, compared with 8.4 percent of Democrats. About half of each group neither

supported nor opposed increasing subsidies, suggesting extensive ambivalence among both

Republicans and Democrats.

When asked about giving all Americans the option to enroll in a government-run health plan (i.e., a

public option), Democrats were far more likely to express support than Republicans (42.3 percent

versus 20.4 percent). Fewer people were ambivalent about this policy than about increasing subsidies.

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR OR OP P O S I TI ON T O M E DICA R E FO R AL L ?

5

Republicans were far more likely than Democrats to oppose a public option (37.6 percent versus 10.0

percent) and were less likely than Democrats to report ambivalence toward this proposal (40.7 percent

versus 45.7 percent).

When asked about support for or opposition to enrolling all Americans in a single government-run

health plan, as would be the case under Medicare for All, 42.3 percent of Democrats expressed support

versus 13.3 percent of Republicans. On the other hand, 52.8 percent of Republicans opposed Medicare

for All versus 12.3 percent of Democrats. Democrats were more likely to neither support nor oppose

Medicare for All than were Republicans (43.5 percent versus 32.6 percent).

Republicans were less likely to oppose enrolling all Americans in a government-run or private

health plan as part of a new national health insurance program (a variant of Medicare for All) than

enrolling all Americans in a single government-run health plan (i.e., Medicare for All). Still, 44.0 percent

of Republicans opposed this approach, compared with 11.6 percent of Democrats. Democrats were

more likely to support this option than Republicans (38.3 percent versus 16.5 percent). That more

people were ambivalent about this proposal than a fully government-run plan may reflect respondents’

difficulty envisioning how this proposal would work or confusion about what the policies would be.

Young adults, nonwhite and Hispanic adults, those with low incomes, and those without private health

insurance are more likely to support than oppose Medicare for All. Those who neither support nor oppose

Medicare for All share many of these characteristics.

Table 2 shows the share of respondents who support, oppose, or neither support nor oppose

Medicare for All by selected characteristics. Considerably more people reported neither supporting nor

opposing Medicare for All than took a clear position of support or opposition. Of those with an opinion,

respondents ages 18 to 34 were substantially more likely to support than oppose (33.3 percent versus

24.1 percent). The middle age group, ages 35 to 49, were slightly more likely to support than oppose

(29.3 percent versus 25.8 percent), though this difference was not statistically significant. The oldest

group, ages 50 to 64, were more likely to oppose than support (33.5 percent versus 26.5 percent).

6

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR O R O PP OS I TI O N TO M E DICA R E FO R ALL ?

TABLE 2

Support for Medicare for All among Adults Ages 18 to 64, Overall and by Demographic,

Socioeconomic, and Geographic Characteristics, March 2019

Share that

supports (%)

Share that neither

supports nor

opposes (%)

Share that

opposes (%)

Sample size

All adults

29.8

40.7***

27.8^^^

4,793

Ages

18–34

33.3

39.8**

24.1***^^^

1,075

35–49

29.3

43.6***

25.8^^^

1,447

50–64

26.5

39.0***

33.5**^

2,271

Race/ethnicity

Non-Hispanic white

28.0

35.6***

35.3***

3,320

Non-Hispanic black

31.2

55.6***

12.3***^^^

408

Other or more than one

race, non-Hispanic

39.5

35.0

21.9***^^^

351

Hispanic

29.9

50.4***

16.1***^^^

714

Educational attainment

Less than high school

23.7

63.5***

11.1***^^^

315

High school graduate

27.2

47.3***

23.2^^^

1,111

Some college

27.8

38.8***

31.5^^

1,370

College graduate or more

education

35.6

29.5***

33.8

1,997

Family income

At or below 138% FPL

29.1

54.2***

14.9***^^^

880

139%–399% FPL

29.7

41.3***

26.6^^^

1,800

400% FPL or higher

30.3

32.2

36.4**^

2,113

Region

Northeast

29.5

42.7***

26.7^^^

874

Midwest

31.3

38.4**

28.8^^^

1,156

South

27.9

40.5***

29.8^^^

1,634

West

31.8

41.5***

24.5**^^^

1,129

Health insurance coverage

at time of survey

Private

28.7

36.6***

33.1*

3,636

Public

32.6

50.6***

15.3***^^^

659

Uninsured

36.3

47.1**

14.1***^^^

374

Source: Health Reform Monitoring Survey, quarter 1 2019.

Note: FPL is federal poverty level. Estimates not shown for the share of adults (less than 2 percent) who did not report whether

they supported or opposed each proposal.

*/**/*** Share differs significantly from share that supports at the 0.10/0.05/0.01 level, using two-tailed tests.

^/^^/^^^ Share differs significantly from share that neither supports nor opposes at the 0.10/0.05/0.01 level, using two-tailed

tests.

Non-Hispanic whites were more likely to oppose than support Medicare for All (35.3 percent versus

28.0 percent). However, non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics were significantly more likely to support

than oppose (31.2 percent versus 12.3 percent for non-Hispanic blacks; 29.9 percent versus 16.1

percent for Hispanics). A majority of both groups neither supported nor opposed. Support was also

greater than opposition among non-Hispanic adults of another race or more than one race.

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR OR OP P O S I TI ON T O M E DICA R E FO R AL L ?

7

Those who did not complete high school were more likely to support Medicare for All than oppose.

Among those with only a high school degree or some college education, the share supporting was not

statistically different from the share opposing. Those who had a college degree or more education were

also evenly split (35.6 percent supporting versus 33.8 percent opposing). The share that neither

supported nor opposed was highest among the less educated (63.5 percent) and lowest among the most

educated (29.5 percent).

The lowest-income group, with incomes at or below 138 percent of FPL, were more likely to support

than oppose Medicare for All (29.1 percent versus 14.9 percent), though more than half of this group

(54.2 percent) neither supported nor opposed. Those with incomes between 139 percent and 399

percent of FPL were equally split between support and opposition, though, again, a large percentage

(41.3 percent) had no opinion. Of those with incomes of 400 percent of FPL or higher, more opposed

than supported (36.4 percent versus 30.3 percent).

By region, the shares of people in the Northeast, Midwest, and South who supported Medicare for

All were not statistically different from the shares that opposed. Those who live in the West were

significantly more likely to support than oppose (31.8 percent versus 24.5 percent).

Those who had private insurance were slightly more likely to oppose than support (33.1 percent

versus 28.7 percent). Those who were uninsured or had public coverage (mostly Medicaid) were more

likely to support than oppose but also more likely to have no opinion.

Though slightly more people support than oppose Medicare for All (29.8 percent versus 27.8

percent; not significant), the largest percentage neither supports nor opposes. Table 2 shows that the

latter group’s demographic and socioeconomic characteristics are similar to those of Medicare for All

supporters (e.g., racial and ethnic minorities, low income, and low education levels). This suggests the

numbers could eventually tilt in favor of support.

Medicare for All supporters and opponents have different perceptions of how it will affect access to care, with

the perceptions of those who are ambivalent about the policy closer to those of supporters.

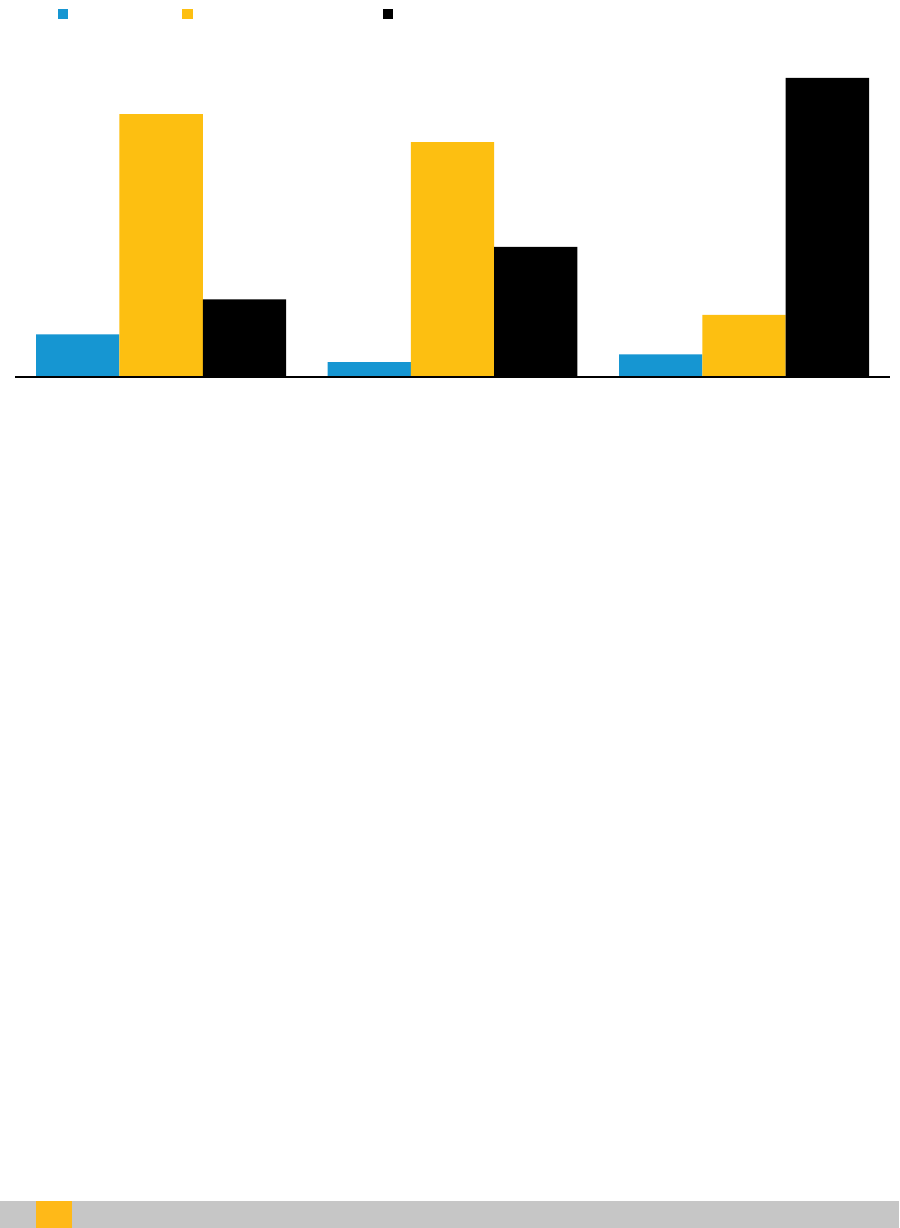

Of those who support Medicare for All, 11.0 percent thought wait times to see a doctor or other

providers would improve, 69 percent thought they would remain the same, and only about 20 percent

thought they would worsen under Medicare for All (figure 1). In contrast, 78.1 percent of Medicare for

All opponents thought wait times to see a doctor or other providers would worsen.

8

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR O R O PP OS I TI O N TO M E DICA R E FO R ALL ?

FIGURE 1

Perceptions of the Effects of Medicare for All on Wait Times to See Doctors and Other Providers,

among Adults Ages 18 to 64, March 2019

URBAN IN ST IT U TE

Source: Health Reform Monitoring Survey, quarter 1 2019.

Notes: Generally, less than 1 percent of respondents did not report their perceptions of the effects of Medicare for All.

*/**/*** Estimate differs significantly from perceptions of supporters at the 0.10/0.05/0.01 level, using two-tailed tests.

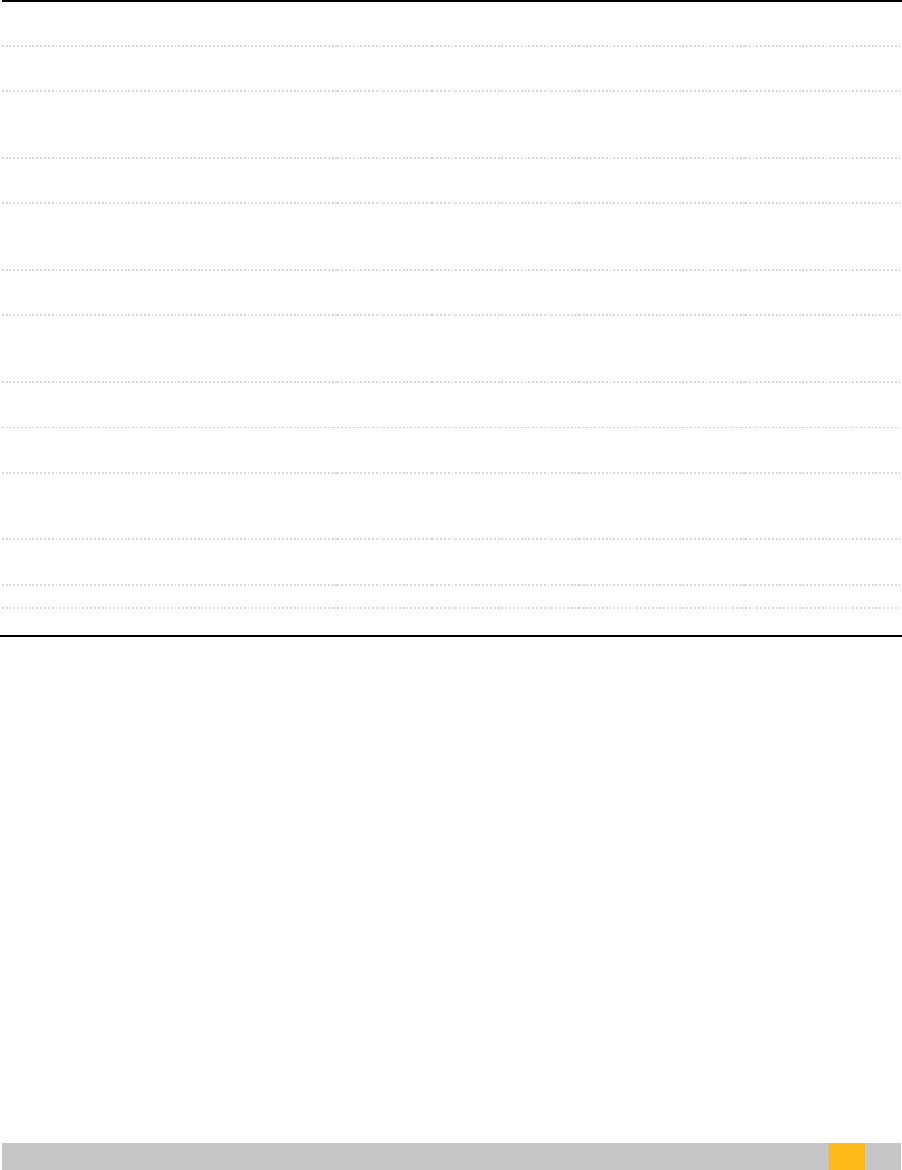

Of those who supported Medicare for All, 24.1 percent were more likely to think they would have a

better choice of providers under Medicare for All and about 62.6 percent thought provider choice

would be about the same (figure 2). For those who oppose the approach, 22.6 percent thought provider

choice would be about the same and 69.5 percent thought it would worsen.

11.0%

3.7%***

5.8%**

68.6%

61.3%*

16.1%***

20.2%

33.9%***

78.1%***

Supports Medicare for All Neither supports nor opposes

Medicare for All

Opposes Medicare for All

Better About the same Worse

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR OR OP P O S I TI ON T O M E DICA R E FO R AL L ?

9

FIGURE 2

Perceptions of the Effects of Medicare for All on Choice of Doctors and Other Providers,

among Adults Ages 18 to 64, March 2019

URBAN IN ST IT U TE

Source: Health Reform Monitoring Survey, quarter 1 2019.

Notes: Generally, less than 1 percent of respondents did not report their perceptions of the effects of Medicare for All.

*/**/*** Estimate differs significantly from perceptions of supporters at the 0.10/0.05/0.01 level, using two-tailed tests.

When asked about the quality of care under Medicare for All, 23.6 percent of those who support

the strategy thought it would improve and 67.2 percent thought it would be about the same (figure 3).

Of those who oppose Medicare for All, 69.9 percent reported that they believed quality of care would

worsen.

24.1%

6.3%***

7.5%***

62.6%

66.0%

22.6%***

13.0%

26.2%***

69.5%***

Supports Medicare for All Neither supports nor opposes

Medicare for All

Opposes Medicare for All

Better About the same Worse

10

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR O R O PP OS I TI O N TO M E DICA R E FO R ALL ?

FIGURE 3

Perceptions of the Effects of Medicare for All on the Quality of Health Care,

among Adults Ages 18 to 64, March 2019

URBAN IN ST IT U TE

Source: Health Reform Monitoring Survey, quarter 1 2019.

Notes: Generally, less than 1 percent of respondents did not report their perceptions of the effects of Medicare for All.

*/**/*** Estimate differs significantly from perceptions of supporters at the 0.10/0.05/0.01 level, using two-tailed tests.

When asked about the ability to get needed care under Medicare for All, 31.9 percent of Medicare

for All supporters thought it would get better and 57.1 percent thought it would be the same (figure 4).

Of those who oppose the approach, 72.1 percent thought it would worsen and 19.7 percent thought it

would be about the same.

23.6%

5.8%***

5.6%***

67.2%

70.3%

23.9%***

8.6%

21.9%***

69.9%***

Supports Medicare for All Neither supports nor opposes

Medicare for All

Opposes Medicare for All

Better About the same Worse

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR OR OP P O S I TI ON T O M E DICA R E FO R AL L ?

11

FIGURE 4

Perceptions of the Effects of Medicare for All on Ability to Get Needed Care,

among Adults Ages 18 to 64, March 2019

URBAN IN ST IT U TE

Source: Health Reform Monitoring Survey, quarter 1 2019.

Notes: Generally, less than 1 percent of respondents did not report their perceptions of the effects of Medicare for All.

*/**/*** Estimate differs significantly from perceptions of supporters at the 0.10/0.05/0.01 level, using two-tailed tests.

We also asked about the impact of Medicare for All on federal taxes. Of those who supported

Medicare for All, a slight majority, 52.3 percent, expected to pay higher taxes, and 33.1 percent thought

their taxes would be about the same (figure 5). In contrast, 85.8 percent of Medicare for All opponents

thought they would pay higher taxes.

31.9%

8.7%***

8.1%***

57.1%

67.0%**

19.7%***

10.1%

22.0%***

72.1%***

Supports Medicare for All Neither supports nor opposes

Medicare for All

Opposes Medicare for All

Better About the same Worse

12

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR O R O PP OS I TI O N TO M E DICA R E FO R ALL ?

FIGURE 5

Perceptions of the Effects of Medicare for All on Federal Taxes Owed,

among Adults Ages 18 to 64, March 2019

URBAN IN ST IT U TE

Source: Health Reform Monitoring Survey, quarter 1 2019.

Notes: Generally, less than 1 percent of respondents did not report their perceptions of the effects of Medicare for All.

*/**/*** Estimate differs significantly from perceptions of supporters at the 0.10/0.05/0.01 level, using two-tailed tests.

Medicare for All supporters cite universal health coverage and greater affordability as important factors in their

support. Higher taxes and concerns about wait times to see health care providers and quality of care are more

important to Medicare for All opponents.

Finally, table 3 shows responses to questions about factors that affected respondents’ support for

or opposition to Medicare for All. About 90 percent or more of Medicare for All supporters cited the

following as important factors in their decisions to support the approach: everyone would have health

insurance coverage, people would pay little to no out-of-pocket costs when they used services, people

would pay lower premiums, the health system would be simpler, and the government would have

greater ability to reduce health care costs. Another 75.6 percent reported reduced administrative

health care costs as an important factor.

52.3%

44.6%**

85.8%***

33.1%

41.7%**

9.6%***

14.3%

11.3%

2.2%***

Supports Medicare for All Neither supports nor opposes

Medicare for All

Opposes Medicare for All

Higher About the same Lower

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR OR OP P O S I TI ON T O M E DICA R E FO R AL L ?

13

TABLE 3

Important Factors in Deciding Whether to Support Medicare for All among Adults Ages 18 to 64,

Overall and by Support for Medicare for All, March 2019

All

adults

Supports

Neither supports

nor opposes

Opposes

Most people would not be able to keep

their current insurance coverage

64.2%

52.9%

66.2%***

73.6%***

Everyone would have health insurance

coverage

68.6%

91.0%

69.3%***

45.0%***

People would pay little or no out-of-

pocket costs when they use health care

services

72.8%

92.6%

72.5%***

54.1%***

Most people would pay lower

premiums

75.2%

96.2%

73.4%***

56.9%***

Higher federal taxes would be needed

to finance a national health insurance

program

67.2%

58.6%

63.3%

81.2%***

The health care system would be

simpler

72.0%

89.4%

71.1%***

56.2%***

The government would have more

control over which health care benefits

are covered by insurance

63.6%

65.0%

60.6%

66.7%

The government would have a greater

ability to reduce health care costs

74.1%

91.7%

72.4%***

59.5%***

Hospitals, doctors, and other providers

might be paid less

47.4%

44.2%

47.3%

50.1%

It might be harder to get an

appointment with a provider for a

health care visit

71.0%

62.1%

70.2%**

82.8%***

Administrative spending on health care

would be reduced

64.0%

75.6%

63.1%**

54.2%***

There might be less medical innovation

66.6%

62.2%

62.7%

77.1%***

Sample size

1,153

343

407

386

Source: Health Reform Monitoring Survey, quarter 1 2019.

Note: */**/*** Estimate differs significantly from adults who support Medicare for All at the 0.10/0.05/0.01 level, using two-tailed

tests.

Of those who opposed Medicare for All, 73.6 percent reported that an important factor in their

decision was that most people would not be able to keep their current insurance coverage, and 81.2

percent reported higher federal taxes to finance a national health program as an important factor.

Other important factors to opponents were that it might be harder to get an appointment with health

care providers (82.8 percent) and that there might be less medical innovation (77.1 percent). Opponents

were about half as likely as supporters (45.0 percent versus 91.0 percent) to report that everyone

having coverage was important in their decision about whether to support Medicare for All.

Nearly all factors in the survey were important to between 60 percent and 75 percent of

respondents who neither supported nor opposed Medicare for All.

14

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR O R O PP OS I TI O N TO M E DICA R E FO R ALL ?

What It Means

The March 2019 HRMS data showed that many Americans neither supported nor opposed a Medicare

for All or single-payer health plan. This ambivalence may partially reflect a lack of understanding of the

issues, which involve complex trade-offs that are difficult to predict. Those with an opinion were

roughly split between support and opposition. Medicare for All supporters were disproportionately

young, racial/ethnic minorities, and uninsured or publicly insured and had lower education levels and

incomes; they were also more likely to be Democrats. Opponents were disproportionately older, non-

Hispanic whites, privately insured, higher income, and Republican. Democrats were also more likely

than Republicans to support more incremental proposals, such as subsidies to low-income people and a

public option. Republican opposition to increasing subsidies, introducing a public option, or providing

universal coverage with a choice of public or private plans was weaker than their opposition to a single-

payer plan, but substantial nonetheless.

Medicare for All supporters responded that it was important that everyone have health care, that

there would be little or no out-of-pocket costs, that premiums would be lower, and that the government

would have greater ability to curb health care cost growth. They also were less likely to expect Medicare

for All to lead to less provider choice or worse quality of care. Medicare for All opponents were more

likely to be concerned about keeping their current insurance coverage, that their taxes would increase,

that it would take longer to get appointments, and that there would be less innovation in medicine.

Further, they were more likely to believe that quality of care would worsen under the approach. Those

who neither supported nor opposed Medicare for All had similar characteristics as supporters:

majorities or near-majorities of adults who were black or Hispanic, did not attend college, had low

incomes, or were uninsured or publicly insured were ambivalent toward this proposal. Their perceptions

of the effect of Medicare for All on access to care were more negative than those of supporters but were

closer to those of supporters than opponents.

This brief shows that currently there is considerable ambivalence toward Medicare for All

approaches to reforming the US health insurance system. Overall, 41 percent of respondents indicated

that they neither support nor oppose the approach. Among those presumably most in need of improved

affordability—those with low incomes and education levels, racial and ethnic minorities, and the

uninsured—support is significantly stronger than opposition, though having no opinion is still most

common. Additional premium and out-of-pocket cost subsidies and making a public option available to

consumers had levels of support similar to those of universal coverage options, though opposition to

these incremental reforms was weaker. We also found that opposition to Medicare for All was strongest

among those ages 50 to 64, non-Hispanic whites, those with higher incomes, and those with current

private coverage. In addition, opposition among Republican and Republican-leaning respondents is

considerable, making reaching political consensus challenging. However, when asked about frequently

cited concerns with Medicare for All approaches, respondents neither supporting nor opposing

Medicare for All answered more similarly to supporters than opponents, indicating some potential for

support to increase in the future and when proposals are better understood.

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR OR OP P O S I TI ON T O M E DICA R E FO R AL L ?

15

About the Series

This brief is part of a series drawing on the HRMS, a survey of the nonelderly population that explores

the value of cutting-edge internet-based survey methods to monitor the Affordable Care Act before

data from federal government surveys are available. Funding for the core HRMS is provided by the

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Urban Institute. For more information on the HRMS and for

other briefs in this series, visit www.urban.org/hrms.

Notes

1

“KFF Health Tracking Poll: The Public’s Views of the ACA,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, June 18, 2019,

https://www.kff.org/interactive/kff-health-tracking-poll-the-publics-views-on-the-aca/; Ashley Kirzinger, Bryan

Wu, and Mollyann Brodie, “KFF Health Tracking Poll – April 2019: Surprise Medical Bills and Public’s View of the

Supreme Court and Continuing Protections for People with Preexisting Conditions,” April 24, 2019,

https://www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/kff-health-tracking-poll-april-2019/.

2

Kenneth Thorpe, “An Analysis of Senator Sanders Single Payer Plan,” Emory University, January 27, 2016,

https://www.healthcare-now.org/296831690-Kenneth-Thorpe-s-analysis-of-Bernie-Sanders-s-single-payer-

proposal.pdf.

3

For more information about the design of the HRMS, visit http://hrms.urban.org.

4

Question wording for the March 2019 survey instrument can be found at http://hrms.urban.org/survey-

instrument/index.html.

5

These findings differ from recent estimates for all adults ages 18 and older reported by the Henry J. Kaiser Family

Foundation (KFF), which asked respondents whether they support or oppose Medicare for All without an option

for ambivalence. There are advantages and disadvantages to each approach. The forced-choice approach

prompts respondents to provide an opinion, even if their support or opposition to the policy is weak. Including a

neutral option gives respondents an opportunity to express ambivalence, but does not capture whether

respondents choosing this option lean toward support versus opposition.

The large share of HRMS respondents selecting the neutral option indicates significant ambivalence toward

Medicare for All, which is consistent with the wide fluctuation in support for Medicare for All in KFF polls when

respondents are presented with arguments in favor of and against this proposal. However, if one assumes that

those who are ambivalent about the proposals would report that they somewhat favor or somewhat oppose if

presented with a forced-choice question, KFF tabulations would be similar to those of the HRMS. We also find

that perceptions of the impact of Medicare for All on access to care and taxes among adults selecting the neutral

option are similar to those of adults who support Medicare for All, which is consistent with the KFF poll findings

that support for Medicare for All is greater than opposition when respondents are presented with a forced-

choice question. The estimates in this brief may also differ from the KFF estimates because of differences in age

(i.e., nonelderly adults versus all adults) and survey mode.

16

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR O R O PP OS I TI O N TO M E DICA R E FO R ALL ?

References

Blahous, Charles. 2018. “The Costs of a National Single-Payer Healthcare System.” Mercatus Working Paper.

Arlington, VA: George Mason University Mercatus Center.

Holahan, John, Matthew Buettgens, Lisa Clemans-Cope, Melissa M. Favreault, Linda J. Blumberg, and Siyabonga

Ndwandwe. 2016. The Sanders Single-Payer Health Care Plan: The Effect on National Health Expenditures and Federal

and Private Spending. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Liu, Jodi L., and Christine Eibner. 2019. National Health Spending Estimates under Medicare for All. Santa Monica, CA:

RAND Corporation.

Long, Sharon K., Genevieve M. Kenney, Stephen Zuckerman, Dana E. Goin, Douglas Wissoker, Fredric Blavin, et al.

2014. “The Health Reform Monitoring Survey: Addressing Data Gaps to Provide Timely Insights into the

Affordable Care Act.” Health Affairs 33 (1): 161–7.

Pollin, Robert, James Heintz, Peter Arno, Jeannette Wicks-Lim, and Michael Ash. 2018. Economic Analysis of

Medicare for All. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Amherst Political Economy Research Institute.

About the Authors

John Holahan is an Institute fellow in the Health Policy Center at the Urban Institute.

Michael Karpman is a senior research associate in the Health Policy Center.

W H AT E X PLAIN S S U PP O R T F OR OR OP P O S I TI ON T O M E DICA R E FO R AL L ?

17

Acknowledgments

This brief was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not

necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute,

its trustees, or its funders. Funders do not determine research findings or the insights and

recommendations of Urban experts. Further information on the Urban Institute’s funding principles is

available at urban.org/fundingprinciples.

The authors gratefully acknowledge helpful comments from Linda Blumberg, Sharon K. Long, and

Robert Reischauer.

ABOUT THE URBAN INSTITUTE

The nonprofit Urban Institute is a leading research organization dedicated to

developing evidence-based insights that improve people’s lives and strengthen

communities. For 50 years, Urban has been the trusted source for rigorous analysis

of complex social and economic issues; strategic advice to policymakers,

philanthropists, and practitioners; and new, promising ideas that expand

opportunities for all. Our work inspires effective decisions that advance fairness and

enhance the well-being of people and places.

Copyright © August 2019.

Urban Institute. Permission is granted for reproduction

of this file, with attribution to the Urban Institute.

500 L’Enfant Plaza SW

Washington, DC 20024

www.urban.org