»

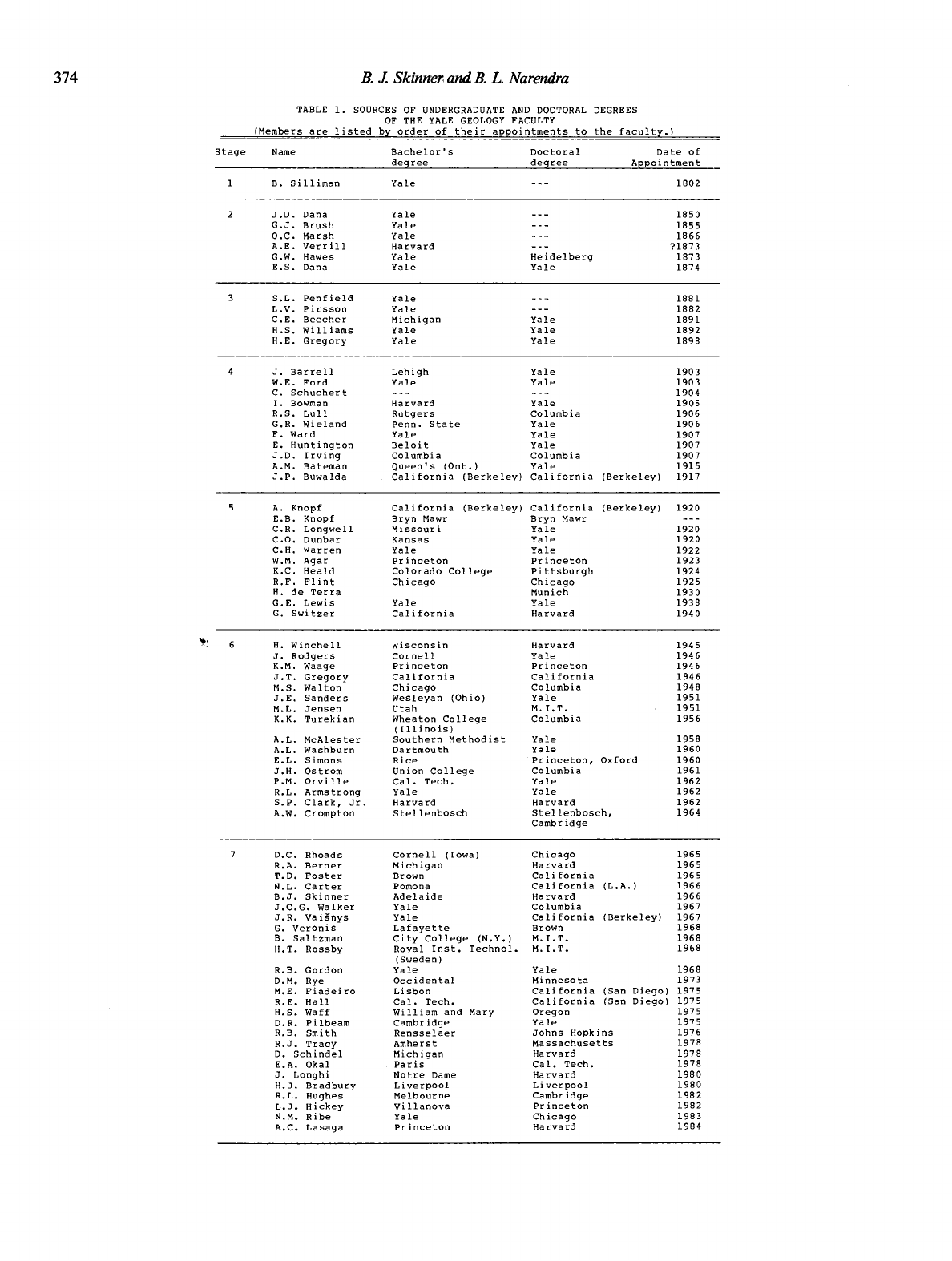

Geological Society of America

Centennial Special Volume 1

1985

Rummaging

through

the attic;

Or,

A brief history of the geological

sciences

at Yale

Brian J. Skinner

Department of Geology and Geophysics

Yak University

P.O.

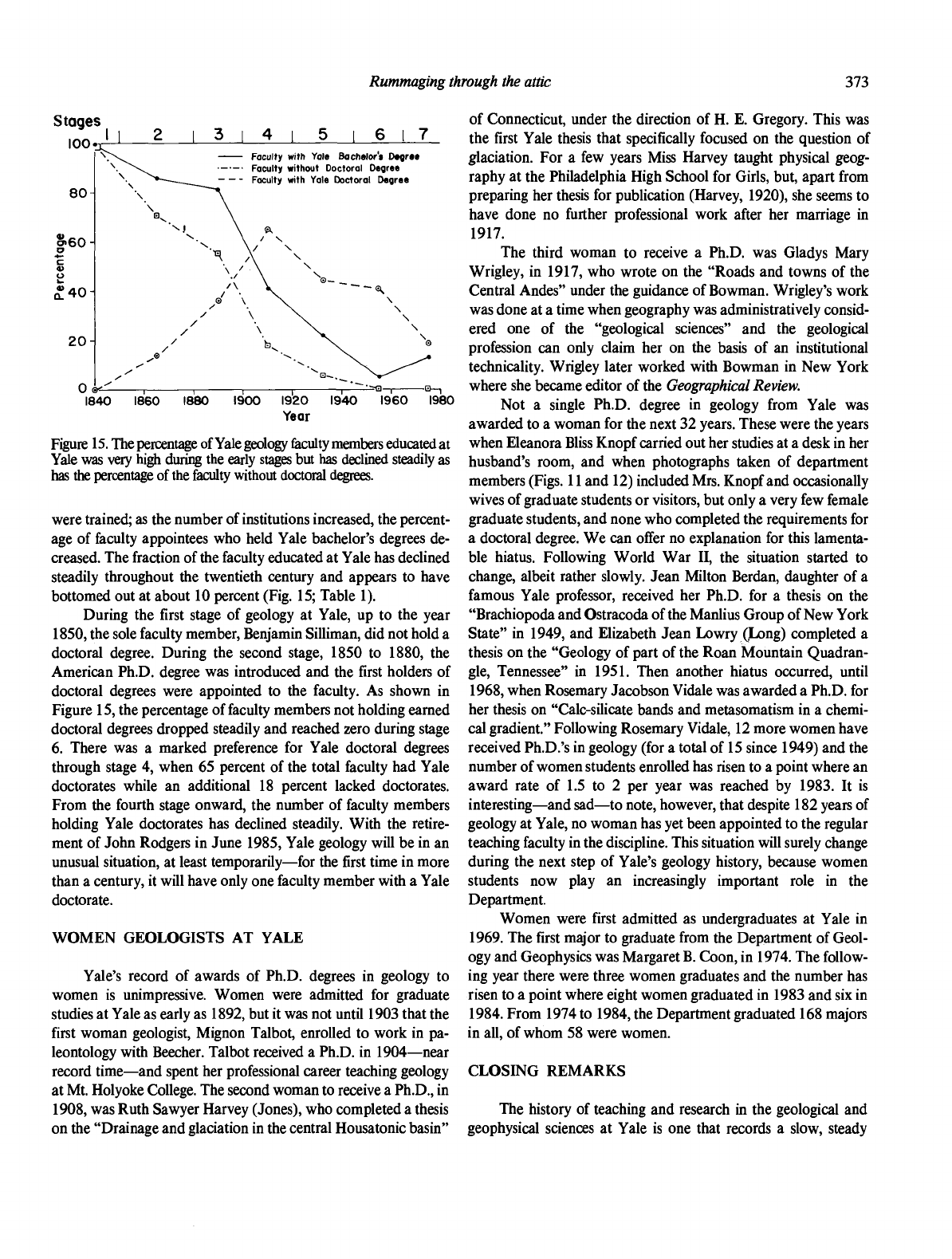

Box 6666

New

Haven,

Connecticut 06511

Barbara

L.

Narendra

Peabody Museum of Natural History

Yak University

P.O.

Box 6666

New

Haven,

Connecticut 06511

ABSTRACT

Commencing with the appointment of Benjamin Silliman as Professor of Chemistry

and Natural History in 1802, the history of instruction and research in the geological

sciences at Yale can be conveniently divided into seven generation-long stages. Each

stage was characterized by a group of faculty members whose interests and personalities

imparted a distinct flavor and character to the institution; as those faculty members left,

retired, or died over a decade-long period of change, responsibility for geological studies

passed to a new generation.

The first stage began with the appointment of

Silliman;

the second started in 1850

as Silliman's career drew to a close and J. D. Dana, his son-in-law, was appointed to the

faculty, and brought the first Ph.D. degrees in the United States. The third stage com-

menced

in

1880,

and the fourth beginning in

1900,

brought the

first

faculty appointments

specifically for graduate instruction. The fifth and sixth stages saw the formative moves

that welded different administrative units together, leading to today's Department of

Geology and Geophysics. Stage seven, commencing

in

1965,

includes the present (1984),

but holds the seeds of stage eight.

The increasing diversity of research activities in geology has led to a doubling of the

number of geological faculty employed at Yale approximately every 50 years. The

number of Ph.D's awarded has increased at a parallel rate. We suggest the size of the

faculty will probably double again by the year 2035 and that production of Ph.D's will

probably rise to a rate of 12 to 15 a year.

355

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

356

B.

J. Skinner and

B.

L. Narendra

ii

I!

t f

M

ft s

1 2 I £ Sis'" k •

CD

II

o o

Iff

£

S:

w

<I se o

or x <

s

ro

o

00

CvJ

to

O)

f

CO

•S B.

s

s5s

.a « -

4 IS

1 2 g

J*"

U —>

™2 *

oo X O

3

E

2 a: I

8

"8

3 «

•a .=

3 S -

•ass-g

fsa"fi

Is

|

.£

!>

9

— oc

pi

s — si

o

M

OS..

-00

S

£*%

^ —

%-a

8

8E.2

o S

B,

2

04

£

H 2 "

Ml

• <S to

r: w -g

2 fs"5

x o £-

o

S

D

5

5 <=

O «0

• -5

00 (j

ui

* •go

" J «

o u o

I

s

i

—

•

(¬

ill

ill

a 5 ~

ed

00 O

i a

_i

o c

CJEJ

oo

IT A H

E

—

^

3 <N O

^ L'tJ

•S

«

19

3 ^ £

^ «

w

(/) e_>

c

^ §

o S

||

§

1

•8

J

§

u

c

| c2

i

w

8*1

w «i 2

S 3 §

=

o o

I

>,.s

o

O

CM

c

CS

0£ ° o

u

J *

I**

x

fa ^

o «J O

All

8

S UT ed

< |«

j J a

•q-

ON =

- - B.

> 3

|i

IS s

s-g 8

c

« O

« « o

2 i §

2 ^

•32

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

Rummaging

through the

attic

357

INTRODUCTION

Yale was one of the first institutions in the United States

where geology was taught; the subject has been offered continu-

ously since 1804, and as a separate discipline since 1812—the

longest unbroken run, so far as we know, of any institution in the

country. A study of the history of geology at Yale shows that any

account must focus on the individuals who have worked at the

institution—how they interacted and how their interests and ac-

tivities changed the science and the institution. The story of the

development of geology at Yale shows how individuals shape an

institution, and could apply to dozens of other distinguished

universities.

Geology was first taught at Yale in the first decade of the

19th century, but records show that even earlier there was re-

search and teaching by Yale people in topics that would today be

considered geology. In the 18th century, for example, it was a

popular occupation for the mathematically inclined to calculate

almanacs estimating the positions of the Moon and the planets

and, especially, predicting the dates of eclipses. Today this would

be called planetology, much of which is housed under the title of

geology. Evidence of a marked interest in another aspect of

planetology—meteors, fireballs, and comets—appears in a pam-

phlet prepared by Yale President Thomas Clap and published

posthumously (Clap, 1781), which records his conclusion that

fireballs are a class of comets that circle the Earth in highly

eccentric orbits. Clap's conclusion was incorrect, but his enthusi-

asm for science and improvements in the teaching of mathematics

were influential on the future of the sciences at Yale.

In 1801 President Timothy Dwight appointed a professor of

mathematics and natural philosophy (physics)—the first of sev-

eral faculty appointments that would place science on a secure

and permanent footing at Yale. For his second appointment in

1802,

he chose a recently graduated student who was then enter-

ing on a legal career; Dwight prevailed on him to abandon the

law and become a teacher. The student, Benjamin Silliman

(1779-1864), had never had a course in chemistry, mineralogy,

or any other subject allied directly to geology, but he accepted

Dwight's offer and, at the age of

23,

was appointed Professor of

"Chymistry" and Natural History. Silliman immediately set to

work learning the subjects he was to teach by attending lectures

in chemistry given by Professor James Woodhouse in the Medi-

cal School of the University of Pennsylvania. While in Philadel-

phia, he also attended lectures by Caspar Wistar on anatomy and

surgery, took a private course in zoology given by Benjamin

Barton, and made social contact with Joseph Priestley. Beyond

some professional advice and assistance offered by Dr. John

Maclean, Professor of Chemistry at Princeton, the Philadelphia

experience was the only formal training in science that Silliman

had when he presented his first course in chemistry to Yale Col-

lege students in 1804-1805. The course consisted of 60 lectures,

with mineralogy introduced at appropriate points. Silliman knew

only too well that he was not really prepared for a career in either

chemistry or natural history, so in 1805 he journeyed to England

and Scotland where he spent a year inspecting mines, visiting

various institutions, and studying in Edinburgh. While in Edin-

burgh, he became interested in the Vulcanist-Neptunist debate,

which was then at its peak. He attended lectures by Dr. John

Murray, an avowed Wernerian-Neptunist, and Dr. Thomas

Hope, an avowed Huttonian-Vulcanist. Though more impressed

by Murray, he struggled with the conflicting philosophies, re-

maining ". . . to a certain extent, a Huttonian, and abating that

part of the rocks which the igneous theory reclaims as the produc-

tion of fire,... as much of a Wernerian as ever" (Fisher, 1866,

v. 1, p. 170). His earliest paper on the geology of New Haven

(Silliman, 1810), written soon after his return from Scotland,

makes interesting reading because it reflects the conflict in his

mind and his attempts to resolve it. As he carried out this earliest

geological investigation of the New Haven region, he was accom-

panied on horseback by interested local citizens, including Noah

Webster, whom Silliman described as being "in the meridian of

life"

and "among the most zealous of my companions. . . ."

(Fisher, 1866, v. 1, p. 216).

By the fall of 1806, Silliman was ready for a full-time teach-

ing role. He was the founder of both the geological and chemical

sciences at Yale, and more important for our story, one of the

founding fathers of geology in North America.

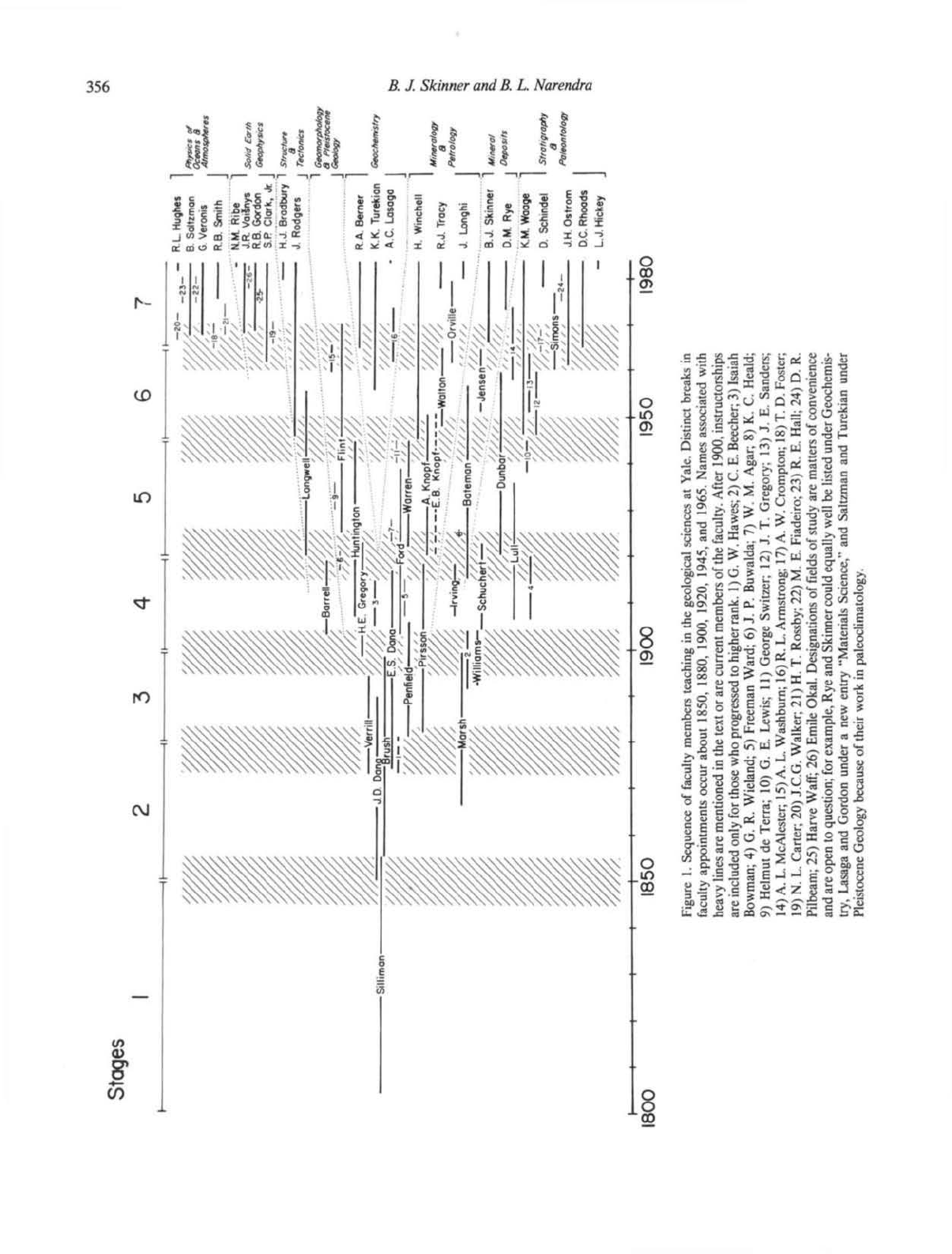

Geological activities at Yale can be readily divided

into seven stages: the first started about 1800 and covered the

long career of Silliman and the early work of his distinguished

student and son-in-law, James Dwight Dana (1813-1895). The

second stage began about 1850, as Silliman's teaching career

drew to a close. Two events of major importance marked the

opening of this second stage. The first was the founding of a

scientific school under the direction of Benjamin Silliman, Jr. and

John Pitkin Norton; the other was the appointment of Dana to

the faculty of Yale College. The third stage opened 30 years later,

about 1880, by which time G. J. Brush had directed the Sheffield

Scientific School to considerable prominence and the Peabody

Museum of Natural History had been founded. Subsequent steps

came in more-or-less generation-long gaps of 20 to 25 years.

Each step began with a group of distinguished faculty members

who were appointed over a period of about eight to ten years, and

imparted to the institution a special flavor determined by their

particular interests. As members of the group retired or died,

responsibility passed to a new generation and a new pattern

started to emerge. Distinct changes occurred about 1880, 1900,

1920,1945, and 1965. It is now apparent that the Department of

Geology and Geophysics has entered yet another stage of genera-

tional refurbishing in the 1980s; future histories will probably

mark 1985 as the midpoint of the change. The dates of change are

not exact—"about 1900" really means the time span from a few

years before 1900 to a few years after 1900. An examination of

Fig. 1 (adapted from an earlier diagram by Jensen, 1952) reveals

that the seven steps are quite distinct.

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

358

B.

J. Skinner and

B.

L

Narendra

STAGE

I: THE

YEARS BEFORE

1850

When Benjamin Silliman started teaching chemistry at Yale,

geology was not even a recognized discipline in most of the major

academic institutions

of

Europe

and

North America.

As

illustra-

tive material became available, Silliman expanded

his

classes

in

geology and mineralogy.

His

first

course, initiated

in

1807, was

a

private

one

based

on

early mineralogical acquisitions.

In 1812,

with

the

famous mineral collection

of

Colonel George Gibbs

available

for his use, he

separated

the

geology

and

mineralogy

lectures from

his

chemistry course

and

started

a new

course

re-

quired of all Yale seniors (Narendra. 1979). By the time Silliman

died

in

1864, geology had risen to such prominence that 33 states

had founded geological surveys (Merrill, 1920),

and

many geo-

logical topics—such as continental glaciation—captured the pub-

lic imagination. The growth of the subject in North America

was

in

no

small measure aided

by

Silliman's elegant bearing (Fig.

2),

powers

of

persuasion,

and

gifted teaching.

But

Silliman

had ac-

quired respectable scientific skills

as

well.

His

student, Amos

Eaton, said, "Silliman

...

gives

the

true scientific dress

to all the

naked mineralogical subjects which

are

furnished

to his

hand"

(Eaton, 1820,

p.

ix). Silliman was a founding officer,

in

1819,

of

the first national organization for geologists,

the

American Geo-

logical Society, and he attracted

to

Yale many students and post-

graduates

who

became leaders

of

the fledgling science.

In 1818

Silliman founded

the American Journal of Science,

providing

a

publication outlet for scientists in

all

fields. That journal has been

published

at

Yale, without

a

break,

to the

present day.

Silliman's effect on Yale as an institution was enormous.

His

leadership, forceful ideas,

and

organizational skills provided

the

momentum

in the

development

of

the physical sciences that

led

directly, albeit some years after

his

death,

to

Yale's becoming

a

university rather than

a

college.

STAGE

2: THE

YEARS BETWEEN ABOUT

1850

AND ABOUT

1880

Two events mark

the

opening of stage

2. The

first

was the

appointment,

in 1850, of

James Dwight Dana

(Fig. 3) as

Silli-

man's successor. Dana graduated from Yale College in 1833

and

grew

to

great prominence during

the

next

20

years

as a

result

of

his scientific papers

and

contributions arising from his participa-

tion

in the

United States Exploring ("Wilkes") Expedition

(1838-1842). Dana was also famous

for

his

System of

Mineral-

ogy,

first published

in 1837, and his Manual of Mineralogy,

which first appeared

in 1848. By

1849,

as

Rossiter (1979)

has

observed,

he

was only

36

but had already accomplished far more

than most geologists did in a lifetime. Aside from being one of the

most distinguished geologists

in

North America, Dana

was

also

Silliman's son-in-law. His appointment

as the

Silliman Professor

of Natural History

in 1850

(changed

to

Silliman Professor

of

Geology

and

Mineralogy

in

1864)

was

necessary

to

keep

him in

New Haven rather than lose him

to

Harvard, and it is not hard

to

imagine the role Silliman might have played behind the scenes

in

Figure

2.

Benjamin Silliman.

A

portrait painted

bv

Samuel

F. B.

Morse

in 1825. (Courtesy, Yale Art Gallery).

order

to

bring about

the

newly endowed chair. Silliman con-

tinued

to

teach geology until Dana had completed his expedition

reports and was ready

to

take over the lecturing role

in 1856.

The second event that marked

the

opening of stage

2

was

a

result of Silliman's practice of accepting postgraduates for special-

ized instruction

(for

which

no

degree

was

given),

a

practice

he

started before

1820. His son,

Benjamin Silliman,

Jr.,

continued

the practice

by

teaching applied chemistry

to

some

of

his father's

special students, starting

in

1842. This

in

turn

led to the

opening

in

1847 of

what

was

initially called

the

Yale School

of

Applied

Chemistry, directed

by the

younger Silliman

and

John Pitkin

Norton.

The

school received

no

financial assistance

and

little

encouragement from Yale. Later named

the

Sheffield Scientific

School after

a

wealthy benefactor, the institution developed into a

successful technical college that awarded

its own

undergraduate

degree

for

professional training

in the

applied sciences.

In 1852

the new degree, the Bachelor of Philosophy (Ph.B.), was awarded

to

a

group that contained members destined

for

greatness

in

geology. Perhaps the most distinguished was George Jarvis Brush

(1831-1912; Fig. 4), Professor of Metallurgy from 1855

to

1871,

then Professor of Mineralogy and Director of the Sheffield Scien-

tific School. Another

was

William

P.

Blake (1826-1910),

a

prominent mining engineer, whose reports about Alaska are sup-

posed

to

have

had a

considerable influence

on U.S.

Secretary

of

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

Rummaging

through

the attic

359

Figure 3. James Dwight Dana. A photograph from an album of a

member of the class of 1865. Yale College.

State Seward when he considered the purchase of Alaska. Blake

later became Professor of Geology and Director of the School of

Mines at the University of Arizona. Yet another of the illustrious

1852 degree recipients was William H. Brewer (1828-1910),

who worked on the California State Survey, was briefly Professor

of Natural Science at the University of California, and then be-

came Professor of Agriculture in the Sheffield Scientific School

from 1864 to 1903.

When the School of Applied Chemistry was founded, it was

administratively enclosed within a new "Department of Philo-

sophy and the Arts," Yale's first formal graduate department.

Master's degrees had been awarded on a somewhat casual basis

since the first commencement in 1702, and degrees were also

given for professional training in the Schools of Medicine, Law,

and Divinity. The new Department, forerunner of today's Grad-

uate School of Arts and Sciences, differed in that it awarded

degrees for research. In 1861 the first three Ph.D. degrees in the

country were awarded—one went to A. W. Wright (later a Pro-

fessor of Chemistry and Molecular Physics at Yale), whose topic

of research was the same as that of President Clap a century

earlier—the velocity and direction of meteors entering the Earth's

atmosphere. In 1863

J.

Willard Gibbs (later Professor of Mathe-

matical Physics at Yale) received his Ph.D. for a thesis on the

form of teeth in spur gears. The thesis has not had any influence

on geology or geologists, but Gibbs's later work in chemical

Figure 4. George Jarvis Brush. A photograph from the archives of the

Pea body Museum.

thermodynamics has had a profound impact on most branches of

geology. The first Ph.D. in geology was awarded to William

North Rice in 1867 for a thesis discussing the Darwinian theory

of the origin of species.

Among the many students attracted to Yale by its scientific

atmosphere was Othniel Charles Marsh (1831-1899; Fig. 5), a

member of the Massachusetts Peabody family, whose sons tradi-

tionally went to Harvard. Arriving in 1856, he was graduated

from Yale College in 1860, did two years of graduate study in the

Sheffield Scientific School, then went to Germany where, with

the encouragement of the younger Silliman and J. D. Dana, he

pursued his interests in vertebrate paleontology. Marsh managed

to convince his wealthy uncle, George Peabody, to provide a gift

of $150,000 to found a museum of natural history at Yale. The

gift was awarded in 1866, the same year in which Marsh was

appointed Professor of Paleontology, the first such professorship

in America. The first building to house the Peabody Museum of

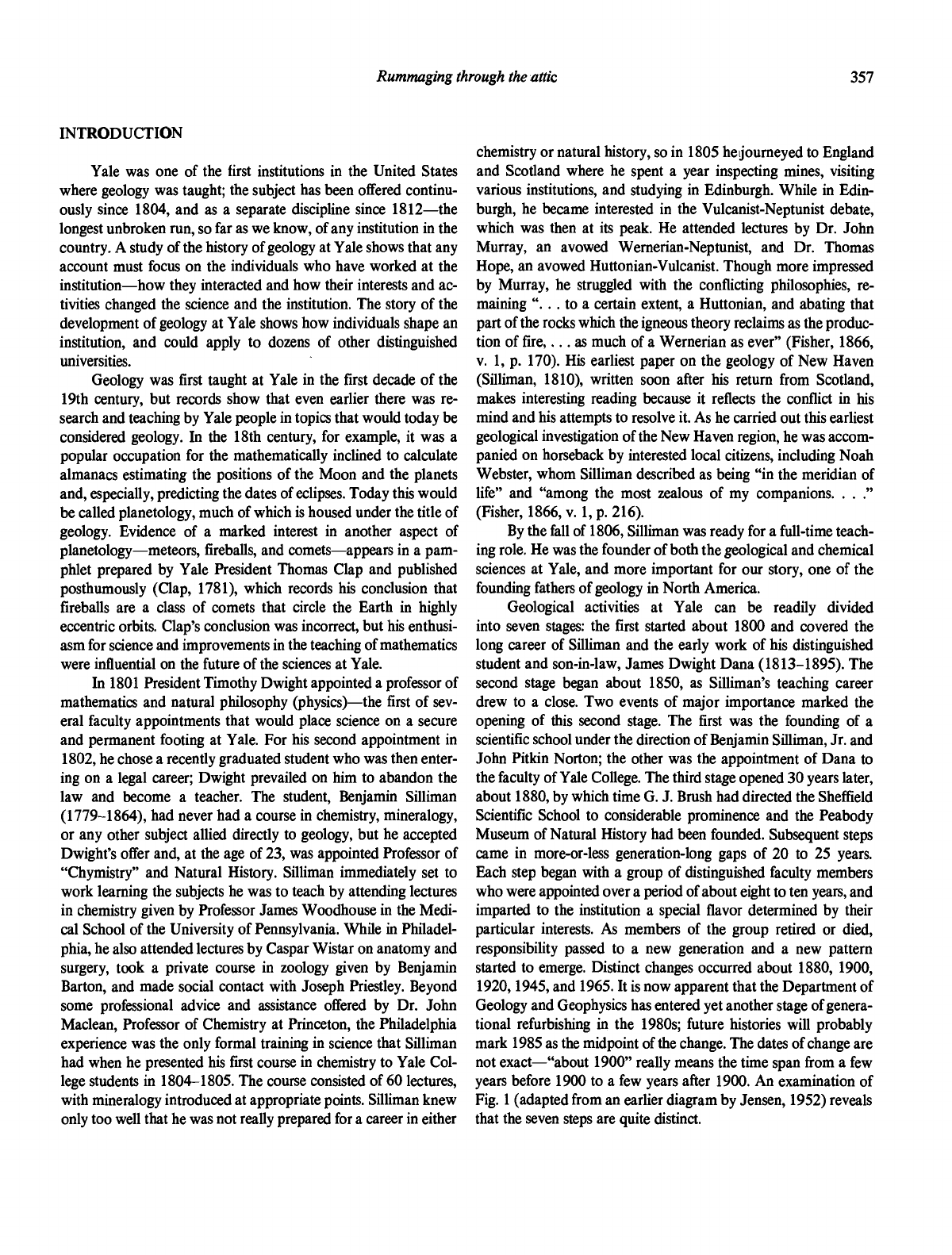

Natural History was completed in 1876. Marsh had started his

paleontological expeditions to the western states (Fig. 6) several

years earlier—the first was in 1870—so by the time the museum

was opened it housed not only collections of materials previously

acquired by Yale, but a wealth of new material ready for study.

Marsh's famous studies on extinct reptiles and other animals

arose from this material, as did his work on toothed birds and the

evolution of the horse, which particularly interested Darwin and

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

360

B.

J. Skinner and

B.

L

Narendra

Figure

5.

Olhniel Charles Marsh.

A

photograph taken

in

1872

by

Wil-

liam Notman. From the archives

of

the Peabody Museum.

Thomas Huxley (Schuchert

and

LeVene, 1940). Marsh's work

marked

the

beginning

of a new

line

of

geological activities

at

Yale—vertebrate paleontology.

Another among

the

students

who

were attracted

to

Yale

sciences during the period from 1850 to 1880 was Clarence King

(1842-1901), who graduated from the Sheffield Scientific School

in

1862.

King's early geological activities were mainly

in the

West,

and

from

1867 to 1877 he was

Director

of

the

U.S.

Geo-

logical Survey

of

the Fortieth Parallel, working

in

the area

now

embraced

by the

states

of

Nevada, Utah,

and

Colorado.

His

greatest scientific interest was probably

the

origin and geological

history of the North American Cordillera, but more important

for

geology

as a

profession

was his

appointment,

in 1879, as

first

Director

of

the newly founded

U.S.

Geological Survey.

He was

the first

of

many Yale geologists

to

join

and

serve that distin-

guished institution. King stressed

the

scientific

as

well

as the

practical side of geology, and the U.S. Geological Survey follows

his tenets to the present day. The importance of the U.S. Geologi-

cal Survey to the development of geology in both North America

and

the

rest

of

the world can hardly

be

overestimated.

As the second stage drew toward its close

in

1880, a change

of major importance occurred within

the

complex institution

called Yale. Some years earlier,

J. D.

Dana

and

others

had be-

come champions

of the

move toward making Yale

a

university

rather than

an

undergraduate college with appendages

in

profes-

sional schools. However, there

was

continued resistance

in the

conservative administration to any plan which would place other

units

of the

academic community

on an

equal footing with

the

College and its rigorous discipline

of

young male minds through

the traditional memorization

and

recitation

of

classical subjects.

Perhaps this regimentation

had

been necessary

in

earlier years

when some

of

the students were really children

and the

faculty

had

to act in

loco

parentis;

Benjamin Silliman,

for

example,

was

13 when

he

entered Yale

in 1792. But

times

had

changed,

and

Harvard, under President Charles William Eliot,

was

directing

the change. Eliot presented

his

ideas

for a

curriculum revision

in

his inaugural address

in

1869;

in the

preparation

of

that address

he

was

advised

by G. J.

Brush

and

Daniel Coit Gilman (B.A.,

1852*),

both officers

of

the Sheffield Scientific School (Morison,

1936).

Gilman later became first president both of the University

of California and of The Johns Hopkins University. Eliot set forth

a plan whereby Harvard would become

a

university

in

which

graduate degrees were

to be

offered

in

many departments

and in

which training

and

research

in the

sciences were

to be

given

special emphasis. When Harvard made such

a

move, could Yale

fail

to

react?

Eliot's plan temporarily

led to a

near-total abandonment

of

required courses

for

undergraduates

at

Harvard. Yale's curricu-

lum reform began

in the

1870s, when electives were allowed

in

Yale College

for the

first time.

By 1887 an

extensive elective

system existed

and

Yale had officially become

a

university (Pier-

son,

1952).

STAGE

3: THE

YEARS FROM ABOUT

1880

TO ABOUT

1900

By

1880,

Yale's activities

in the

geological sciences were

located in four administratively separate units—Yale College, the

Sheffield Scientific School,

the

Graduate School,

and the

Pea-

body Museum.

In the

College,

a

general geology course

was

offered

by J. D.

Dana using his

Manual of Geology

(first edition

in 1862) as a text.

It

is interesting

to

look

at

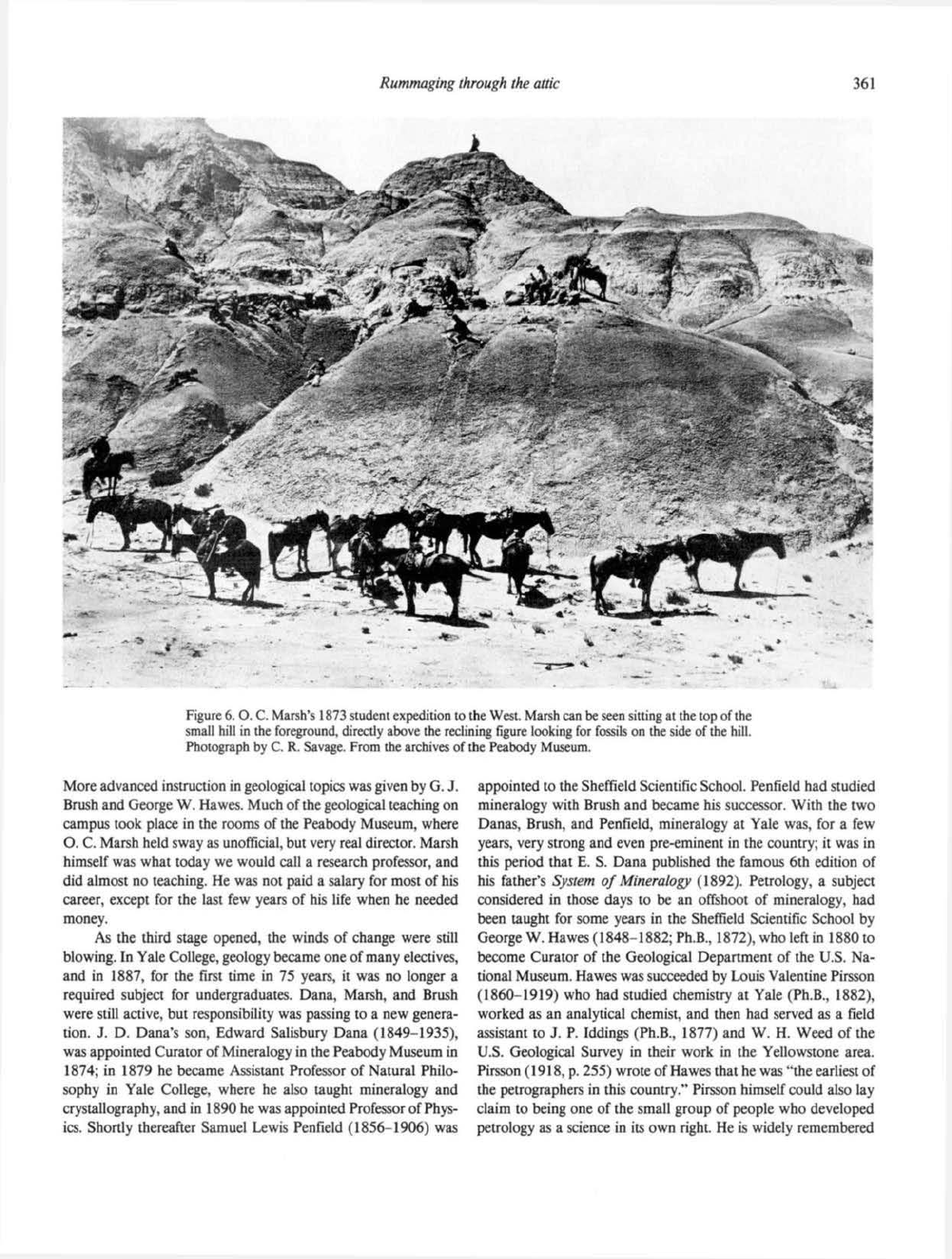

the exam Dana gave

students in 1884 (Fig. 7). The questions have

a

decidedly modern

ring to them and one wonders if students today could handle such

an exam

in

two hours. It

is

especially interesting to see Question

4

concerning the sources of heat that cause geological changes. This

was some years before the discovery of radioactivity, when ques-

tions such

as the

heat generated

by

gravitational compression

were being widely debated. Dana obviously taught

a

course that

was current.

In

the

Sheffield Scientific School, students followed

one of

several prescribed programs

of

study,

the

choice depending

on

their proposed profession. Basic geology

was

taught, oddly

enough,

by

Addison Emery Verrill, Professor

of

Zoology (using

Dana's textbook)

and was

required

for

most

of the

programs.

•Degrees

arc

understood to be Yale degrees

unless

otherwise indicated.

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

Rummaging

through the

attic

361

Figure 6. O. C. Marsh's 1873 student expedition to the West. Marsh can be seen sitting at the top of the

small hill in the foreground, directly above the reclining figure looking for fossils on the side of the hill.

Photograph by C. R. Savage. From the archives of the Peabody Museum.

More advanced instruction in geological topics was given by G. J.

Brush and George W. Hawes. Much of the geological teaching on

campus took place in the rooms of the Peabody Museum, where

O. C. Marsh held sway as unofficial, but very real director. Marsh

himself was what today we would call a research professor, and

did almost no teaching. He was not paid a salary for most of his

career, except for the last few years of his life when he needed

money.

As the third stage opened, the winds of change were still

blowing. In Yale College, geology became one of many electives,

and in 1887, for the first time in 75 years, it was no longer a

required subject for undergraduates. Dana, Marsh, and Brush

were still active, but responsibility was passing to a new genera-

tion.

J. D. Dana's son, Edward Salisbury Dana (1849-1935),

was appointed Curator of Mineralogy in the Peabody Museum in

1874;

in 1879 he became Assistant Professor of Natural Philo-

sophy in Yale College, where he also taught mineralogy and

crystallography, and in 1890 he was appointed Professor of Phys-

ics.

Shortly thereafter Samuel Lewis Penfield (1856-1906) was

appointed to the Sheffield Scientific School. Penfield had studied

mineralogy with Brush and became his successor. With the two

Danas, Brush, and Penfield, mineralogy at Yale was, for a few

years,

very strong and even pre-eminent in the country; it was in

this period that E. S. Dana published the famous 6th edition of

his father's System of Mineralogy (1892). Petrology, a subject

considered in those days to be an offshoot of mineralogy, had

been taught for some years in the Sheffield Scientific School by

George W. Hawes (1848-1882; Ph.B., 1872), who left in 1880 to

become Curator of the Geological Department of the U.S. Na-

tional Museum. Hawes was succeeded by Louis Valentine Pirsson

(1860-1919) who had studied chemistry at Yale (Ph.B., 1882),

worked as an analytical chemist, and then had served as a field

assistant to J. P. Iddings (Ph.B., 1877) and W. H. Weed of the

U.S. Geological Survey in their work in the Yellowstone area.

Pirsson (1918, p. 255) wrote of Hawes that he was "the earliest of

the petrographers in this country." Pirsson himself could also lay

claim to being one of the small group of people who developed

petrology as a science in its own right. He is widely remembered

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

362

B.

J. Skinner and

B.

L. Narendra

YALE COLLEGE.

1884.

DECEMBER EXAMINATION—SENIOR CLASS.

Geology.

Ton, 2 HOUBS.

1.

What are fragmental rocks and the sources of their

materials

?

2.

The chemical constitution and organic sources of limestones.

3.

The relation between the transporting power of rivers and

their velocity; the geological effects of transportation.

4.

Sources of the heat concerned in producing geological

changes.

5. The distribution of the dry land of North America at the

close of Archaean time; the mountains that then existed.

6. Evidence as to the time of elevation of the Rocky

Mountains.

7. When appeared the first fishes; the first amphibians; the

first mammals ?

8.

What are mountains of eircumdenudation and how were

they made ?

9. Distribution of coal areas in North America; the age of

the coal beds of the Rocky Mountains.

Figure 7. The examination of 1884 given to the class in introductory

geology in Yale College by J. D. Dana. The numbers at the bottom of

the page were written by the student who took

the

exam.

as the P of the CIPW system of normative calculations [Cross,

Iddings, Pirsson, and H. S. Washington (B.A., 1886)]. In many

respects, however, Pirsson reinforced the mineralogical strengths

of Yale's geological activities

so,

as they neared the ends of their

careers, J. D. Dana, a generalist, and O. C. Marsh, a paleontolo-

gist, were the two who gave breadth to the field. Fortunately,

Pirsson became increasingly interested in some of the larger geo-

logical problems and in 1893 he was relieved of

his

teaching in

mineralogy so he could take over the course of basic geology

from Verrill (Cross, 1920). In 1915, Pirsson and Charles Schu-

chert published their course notes, which became the first in a

long series of physical and historical geology texts authored by

Yale geologists. The forefather of them all was Dana's Manual of

Geology, used both at Yale and around the country for more than

a generation. Verrill and Pirsson not only used Dana's text, they

knew the man himself and taught the line of reasoning used in his

book. In a sense, the many physical and historical geology texts

from Yale faculty are one of the institution's major products.

The staff at Yale may have been small during the final years

of the 19th century, but its prestige was high. Both J.

D*'Dana

and Marsh were on the committee of the National Academy of

Sciences that recommended the founding of the

U.S.

Geological

Survey to

Congress.

Marsh was President of the Academy for 12

years (1883-1895), and Dana became the second President of

the Geological Society of America, succeeding James Hall in

1889.

J. D. Dana stopped teaching in 1890 and a new cycle of

change was underway. Unfortunately, the first steps were falter-

ing. Henry Shaler Williams (1847-1918) was appointed in 1892

and succeeded Dana in 1894 as Silliman Professor of Geology in

Yale

College.

After Williams graduated from the Sheffield Scien-

tific School in

1868,

he completed a

Ph.D.

(1871), taught briefly

in Kentucky, and was then called to the chair of geology at

Cornell, where he was responsible for the founding of the society

of Sigma Xi. He became famous for his studies of the Devonian

strata of the eastern United States and for his development of

methods of stratigraphic correlation. He would seem to have been

an ideal appointee, but unfortunately his few years at Yale were

unhappy

ones.

Reportedly Williams was not as interesting a lec-

turer as Dana, and he suffered by comparison (Cleland, 1919).

Problems caused by the assignment of faculty to different admin-

istrative units on campus also seemed to get in Williams's way,

as later correspondence from H.

E.

Gregory to Williams suggests:

". . .it is certainly due to you that the agitation was started and

that our faculty began to

see

clearly the danger of the relationship

between the schools as they did" (Gregory, 1906,

p.

148).

In 1904, Williams returned to Cornell. Only one other ap-

pointment was made before a great faculty expansion started at

the turn of the century—that of Charles Emerson Beecher

(1856-1904), appointed Assistant in Paleontology in the Pea-

body Museum in 1888. Beecher, an invertebrate paleontologist,

had studied at the University of Michigan and worked in Albany

with James Hall; after he came to Yale he completed a thesis on

fossil sponges and was awarded a

Ph.D.

degree in

1889.

This led

to his appointment as a faculty member (Professor in 1897) in the

Sheffield Scientific School, and he succeeded Marsh as unofficial

director of the Peabody Museum. Beecher seems to have been the

first senior faculty appointee to teach paleontology on a regular

basis;

unfortunately he died suddenly and unexpectedly in 1904,

the same year in which Williams resigned. Marsh had died in

1899,

so, as Yale entered its third century of instruction, it was

rich with paleontological collections but devoid of faculty

members to teach from them.

The number of students trained at Yale during the 20 years

from 1880 to 1900 was not especially large, but those Yale

graduates went on to play major roles in the development of

science in the United States. One of the most significant was

Arthur L. Day, who graduated from the Sheffield Scientific

School in 1892 and then received his Ph.D. in physics from the

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

Rummaging

through the attic

363

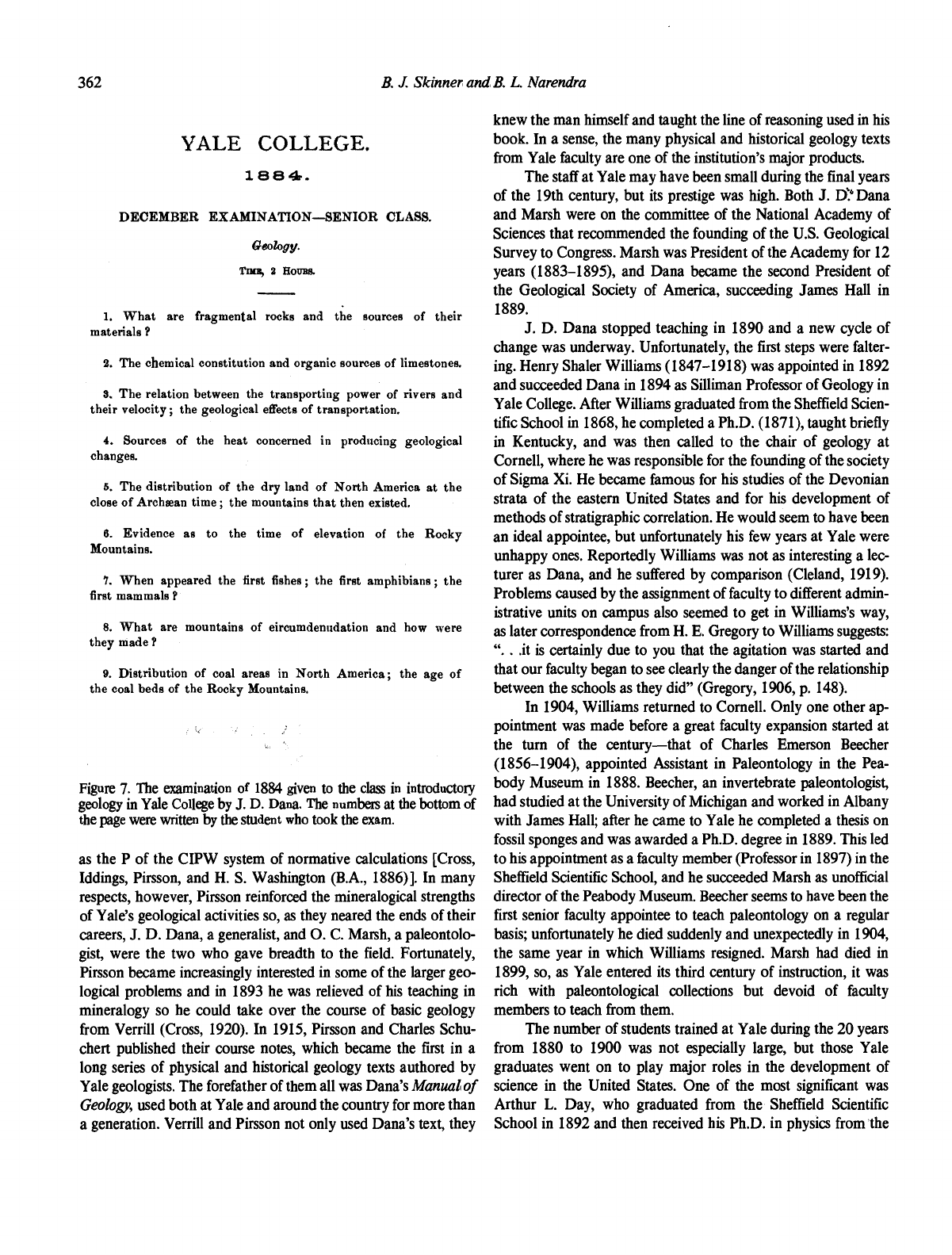

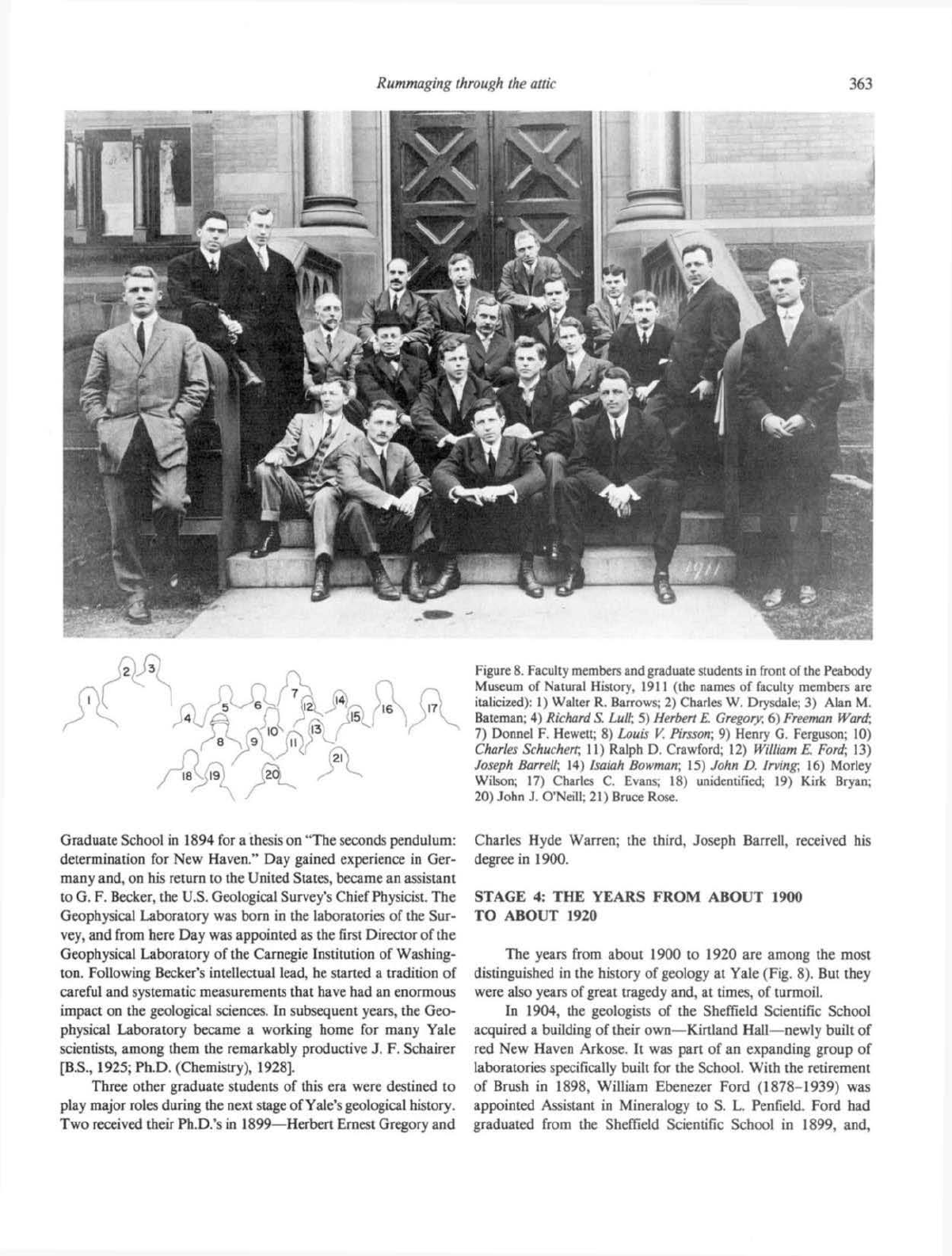

Figure 8. Faculty members and graduate students in front of the Peabody

Museum of Natural History, 1911 (the names of faculty members are

italicized): 1) Walter R. Barrows; 2) Charles W. Drysdale; 3) Alan M.

Bateman; 4) Richard

S.

Lull: 5) Herbert

E.

Gregory, 6) Freeman Ward;

7) Donnel F. Hewctt; 8) Louis V. Pirsson; 9) Henry G. Ferguson; 10)

Charles Schuchert, II) Ralph D. Crawford; 12) William E Ford; 13)

Joseph Barrel!; 14) Isaiah Bowman; 15) John D. Irving, 16) Morley

Wilson; 17) Charles C. Evans; 18) unidentified; 19) Kirk Brvan;

20) John J. O'Neill; 21) Bruce Rose.

Graduate School in 1894 for a thesis on "The seconds pendulum:

determination for New Haven." Day gained experience in Ger-

many and, on his return to the United States, became an assistant

to G. F. Becker, the U.S. Geological Survey's Chief Physicist. The

Geophysical Laboratory was born in the laboratories of the Sur-

vey, and from here Day was appointed as the first Director of the

Geophysical Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution of Washing-

ton.

Following Becker's intellectual lead, he started a tradition of

careful and systematic measurements that have had an enormous

impact on the geological sciences. In subsequent years, the Geo-

physical Laboratory became a working home for many Yale

scientists, among them the remarkably productive J. F. Schairer

[B.S.,

1925; Ph.D. (Chemistry),

1928].

Three other graduate students of this era were destined to

play major roles during the next stage of Yale's geological history.

Two received their Ph.D.'s in 1899—Herbert Ernest Gregory and

Charles Hyde Warren; the third, Joseph Barrell, received his

degree in 1900.

STAGE

4: THE YEARS FROM ABOUT 1900

TO

ABOUT 1920

The years from about 1900 to 1920 are among the most

distinguished in the history of geology at Yale (Fig. 8). But they

were also years of great tragedy and, at times, of turmoil.

In 1904, the geologists of the Sheffield Scientific School

acquired a building of their own—Kirtland Hall—newly built of

red New Haven Arkose. It was part of an expanding group of

laboratories specifically built for the School. With the retirement

of Brush in 1898, William Ebenezer Ford (1878-1939) was

appointed Assistant in Mineralogy to S. L. Penfield. Ford had

graduated from the Sheffield Scientific School in 1899, and.

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

364

B.

J. Skinner and

B.

L. Narendra

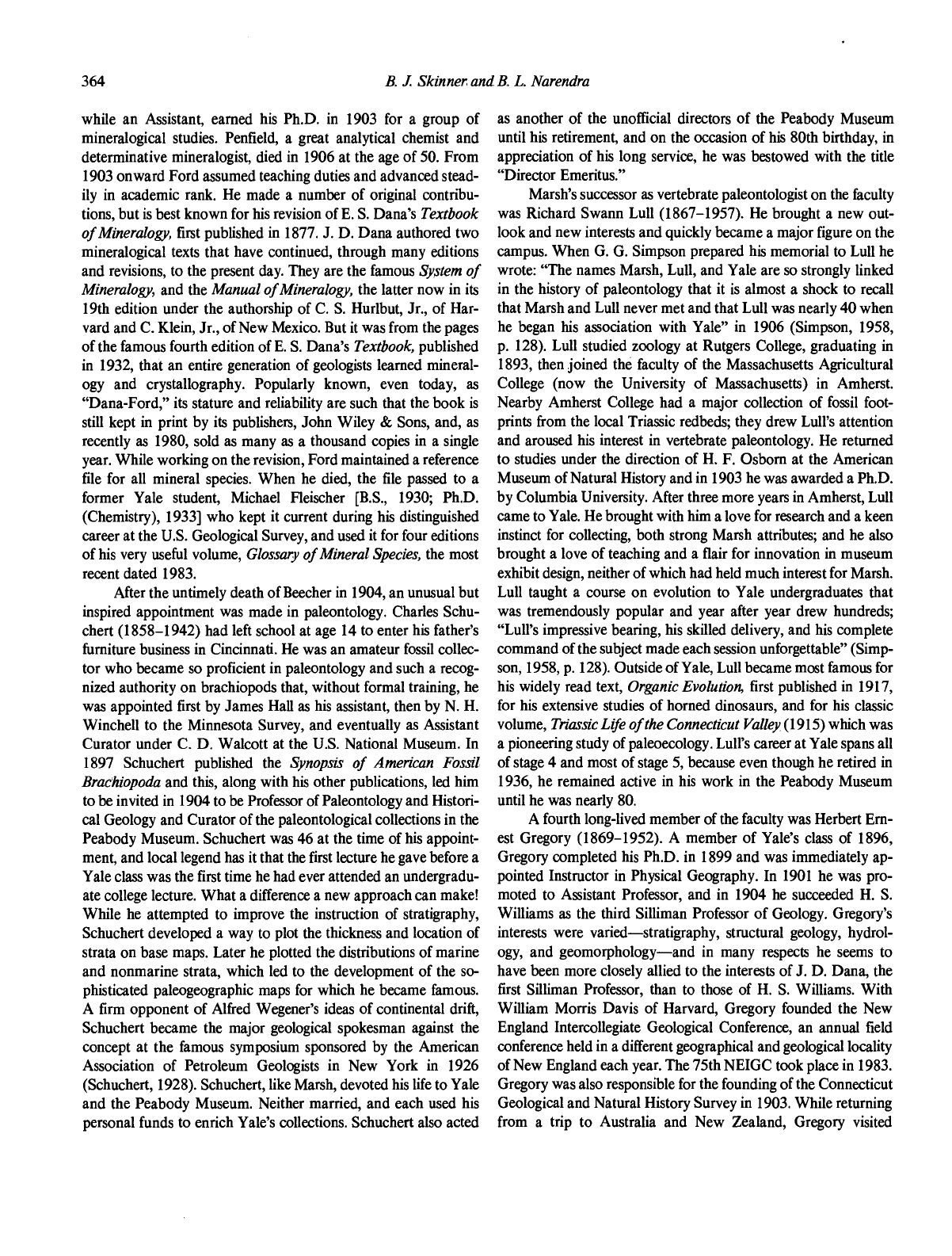

while an Assistant, earned his Ph.D. in 1903 for a group of

mineralogical studies. Penfield, a great analytical chemist and

determinative mineralogist, died in 1906 at the age of 50. From

1903 onward Ford assumed teaching duties and advanced stead-

ily in academic rank. He made a number of original contribu-

tions,

but is best known for his revision of

E.

S. Dana's Textbook

of Mineralogy, first published in 1877. J. D. Dana authored two

mineralogical texts that have continued, through many editions

and revisions, to the present day. They are the famous System of

Mineralogy,

and the

Manual of Mineralogy,

the latter now in its

19th edition under the authorship of C. S. Hurlbut, Jr., of Har-

vard and C. Klein, Jr., of New Mexico. But it was from the pages

of the famous fourth edition of

E.

S. Dana's Textbook, published

in 1932, that an entire generation of geologists learned mineral-

ogy and crystallography. Popularly known, even today, as

"Dana-Ford," its stature and reliability are such that the book is

still kept in print by its publishers, John Wiley & Sons, and, as

recently as 1980, sold as many as a thousand copies in a single

year. While working on the revision, Ford maintained a reference

file for all mineral species. When he died, the file passed to a

former Yale student, Michael Fleischer [B.S., 1930; Ph.D.

(Chemistry), 1933] who kept it current during his distinguished

career at the U.S. Geological Survey, and used it for four editions

of his very useful volume, Glossary of Mineral Species, the most

recent dated 1983.

After the untimely death of Beecher in 1904, an unusual but

inspired appointment was made in paleontology. Charles Schu-

chert (1858-1942) had left school at age 14 to enter his father's

furniture business in Cincinnati. He was an amateur fossil collec-

tor who became so proficient in paleontology and such a recog-

nized authority on brachiopods that, without formal training, he

was appointed first by James Hall as his assistant, then by N. H.

Winchell to the Minnesota Survey, and eventually as Assistant

Curator under C. D. Walcott at the U.S. National Museum. In

1897 Schuchert published the Synopsis of American Fossil

Brachiopoda and this, along with his other publications, led him

to be invited in 1904 to be Professor of Paleontology and Histori-

cal Geology and Curator of the paleontological collections in the

Peabody Museum. Schuchert was 46 at the time of his appoint-

ment, and local legend has it that the first lecture he gave before a

Yale class was the first time he had ever attended an undergradu-

ate college lecture. What a difference a new approach can make!

While he attempted to improve the instruction of stratigraphy,

Schuchert developed a way to plot the thickness and location of

strata on base maps. Later he plotted the distributions of marine

and nonmarine strata, which led to the development of the so-

phisticated paleogeographic maps for which he became famous.

A firm opponent of Alfred Wegener's ideas of continental drift,

Schuchert became the major geological spokesman against the

concept at the famous symposium sponsored by the American

Association of Petroleum Geologists in New York in 1926

(Schuchert, 1928). Schuchert, like Marsh, devoted his life to Yale

and the Peabody Museum. Neither married, and each used his

personal funds to enrich Yale's collections. Schuchert also acted

as another of the unofficial directors of the Peabody Museum

until his retirement, and on the occasion of his 80th birthday, in

appreciation of his long service, he was bestowed with the title

"Director Emeritus."

Marsh's successor as vertebrate paleontologist on the faculty

was Richard Swann Lull (1867-1957). He brought a new out-

look and new interests and quickly became a major figure on the

campus. When G. G. Simpson prepared his memorial to Lull he

wrote: "The names Marsh, Lull, and Yale are so strongly linked

in the history of paleontology that it is almost a shock to recall

that Marsh and Lull never met and that Lull was nearly 40 when

he began his association with Yale" in 1906 (Simpson, 1958,

p.

128). Lull studied zoology at Rutgers College, graduating in

1893,

then joined the faculty of the Massachusetts Agricultural

College (now the University of Massachusetts) in Amherst.

Nearby Amherst College had a major collection of fossil foot-

prints from the local Triassic redbeds; they drew Lull's attention

and aroused his interest in vertebrate paleontology. He returned

to studies under the direction of H. F. Osborn at the American

Museum of Natural History and in 1903 he was awarded a Ph.D.

by Columbia University. After three more years in Amherst, Lull

came to Yale. He brought with him a love for research and a keen

instinct for collecting, both strong Marsh attributes; and he also

brought a love of teaching and a flair for innovation in museum

exhibit design, neither of which had held much interest for Marsh.

Lull taught a course on evolution to Yale undergraduates that

was tremendously popular and year after year drew hundreds;

"Lull's impressive bearing, his skilled delivery, and his complete

command of the subject made each session unforgettable" (Simp-

son,

1958, p. 128). Outside of Yale, Lull became most famous for

his widely read text, Organic Evolution, first published in 1917,

for his extensive studies of horned dinosaurs, and for his classic

volume, Triassic Life of the Connecticut

Valley

(1915) which was

a pioneering study of paleoecology. Lull's career at Yale spans all

of stage 4 and most of stage 5, because even though he retired in

1936,

he remained active in his work in the Peabody Museum

until he was nearly 80.

A fourth long-lived member of the faculty was Herbert Ern-

est Gregory (1869-1952). A member of Yale's class of 1896,

Gregory completed his Ph.D. in 1899 and was immediately ap-

pointed Instructor in Physical Geography. In 1901 he was pro-

moted to Assistant Professor, and in 1904 he succeeded H. S.

Williams as the third Silliman Professor of Geology. Gregory's

interests were varied—stratigraphy, structural geology, hydrol-

ogy, and geomorphology—and in many respects he seems to

have been more closely allied to the interests of J. D. Dana, the

first Silliman Professor, than to those of H. S. Williams. With

William Morris Davis of Harvard, Gregory founded the New

England Intercollegiate Geological Conference, an annual field

conference held in a different geographical and geological locality

of New England each year. The 75th NEIGC took place in 1983.

Gregory was also responsible for the founding of the Connecticut

Geological and Natural History Survey in 1903. While returning

from a trip to Australia and New Zealand, Gregory visited

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

Rummaging

through the

attic

365

Figure 9. Joseph Barrell. A photograph published originally in the

Bul-

letin of the Geological Society of America (v. 34, 1923, PI. 2).

Hawaii and found that the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Honolulu

was in need of both a new director and a major revitalization.

Welcoming reaffirmation of the historic ties forged by Yale-

educated missionaries in the early 1800s, the Yale Corporation

and the Bishop Museum Trustees designed an arrangement

whereby the Director of the Bishop Museum should also hold the

rank of Professor at Yale. Gregory became Director of the Bishop

Museum in 1920, and for a few years divided his time between

New Haven and Honolulu, until he established his residence

permanenUy in Hawaii. He continued to hold the Silliman Pro-

fessorship until his retirement in 1936, but by then he had not

taught at Yale for at least a decade.

Another paleontologist, who began his Yale association by

collecting fossils in the West for Marsh, was George Reber Wie-

land (Ph.D., 1900). Lecturer in Paleobotany from 1906 to 1920,

with nonteaching research appointments thereafter, Wieland is

best known for his work on fossil cycadophytes, but he was also

active and productive in the study of dinosaurs and fossil turtles

(Nelson, 1977).

The careers of E. S. Dana, Ford, Lull, and Schuchert were

all long and distinguished; they spanned the time from the end of

the 19th century to the middle years of the 20th. It was these four

men,

together with Pirsson and Gregory, who carried forward the

traditions and methods of their Yale forebears of the 19th cen-

tury. It is fortunate that they were so long-lived and so active.

because the careers of two other faculty members were sadly cut

short—those of Joseph Barrell and J. D. Irving.

According to H. E. Gregory (1923), Joseph Barrell

(1869-1919; Fig. 9) was the first person appointed to the geolog-

ical faculty at Yale to carry out the program of organized grad-

uate course work that had been authorized by the University in

1902.

Prior to that time, graduate instruction had apparently been

largely an extension of undergraduate instruction. From 1902

onward, the Ph.D. degree would not only entail completion of

research and a satisfactory thesis, but, increasingly, formal courses

as well. Barrell received a B.Sc. from Lehigh University in 1892

and a degree in mining (E.M.) in 1893. He then instructed in

mining and metallurgy at Lehigh for four years and completed a

geological study of the highlands of New Jersey, for which he

received an M.Sc. in 1897. This prepared him to work with

Pirsson, Penfield, and Beecher at Yale from 1898 to 1900, when

he received a Ph.D. for a thesis on the geology of the Elkhorn

District, Montana. He then returned to Lehigh for three more

years.

He was appointed Assistant Professor of Structural Geol-

ogy at Yale in 1903 and Professor in 1908, a post he retained

until his tragic early death from spinal meningitis in 1919.

Barren's interests were eclectic, and he published major pa-

pers on such topics as isostasy, geologic time (he believed the

earth to be at least 1.5 billion years old), the influence of climate

on the nature of stratified rocks, the nature and relationship of

marine and continental environments of deposition, volume

changes during metamorphism, and the planetesimal hypothesis

of the origin of planets. He was apparently an extraordinarily

acute and demanding teacher of graduate students, but too de-

manding for most undergraduates. Among his peers and col-

leagues he seems to have been held in great affection but also in

great awe; in Barren's memorial, Gregory wrote (1923, p. 22)

that "he possessed many attractive human traits, but his intellec-

tual power was so obvious and so continuously displayed that 20

years of intimacy has left me an impression of a mind rather than

of a man." Geologists often overlook Barrell because he died

young and because his interests ranged so widely, but as G. L.

Thompson (1964, p. 11) remarked, "many modern ideas are

essentially his but since these ideas involved the basic fundamen-

tals of geology, few people realize that Barrell was the originator."

The second important appointee primarily for graduate in-

struction was John Duer Irving (1874-1918), a petrologist and

economic geologist who was appointed Professor of Geology and

Mineralogy in the Sheffield Scientific School in 1907. Irving had

studied at Columbia, where he received his Ph.D. in 1899. He

was teaching at Lehigh University when a small group of people

gathered in Washington, D.C. to form a not-for-profit member-

ship corporation in order to publish a new journal. Economic

Geology. Irving became its first editor, and when he moved to

New Haven he brought the editorial responsibility with him.

Though the journal has no formal connection with Yale, it has

been housed and edited there ever since—after Irving, by A. M.

Bateman and today by B. J. Skinner. In July 1917, having ob-

tained a leave of absence from Yale, Irving left for France to serve

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

366

B.

J. Skinner and

B.

L. Narendra

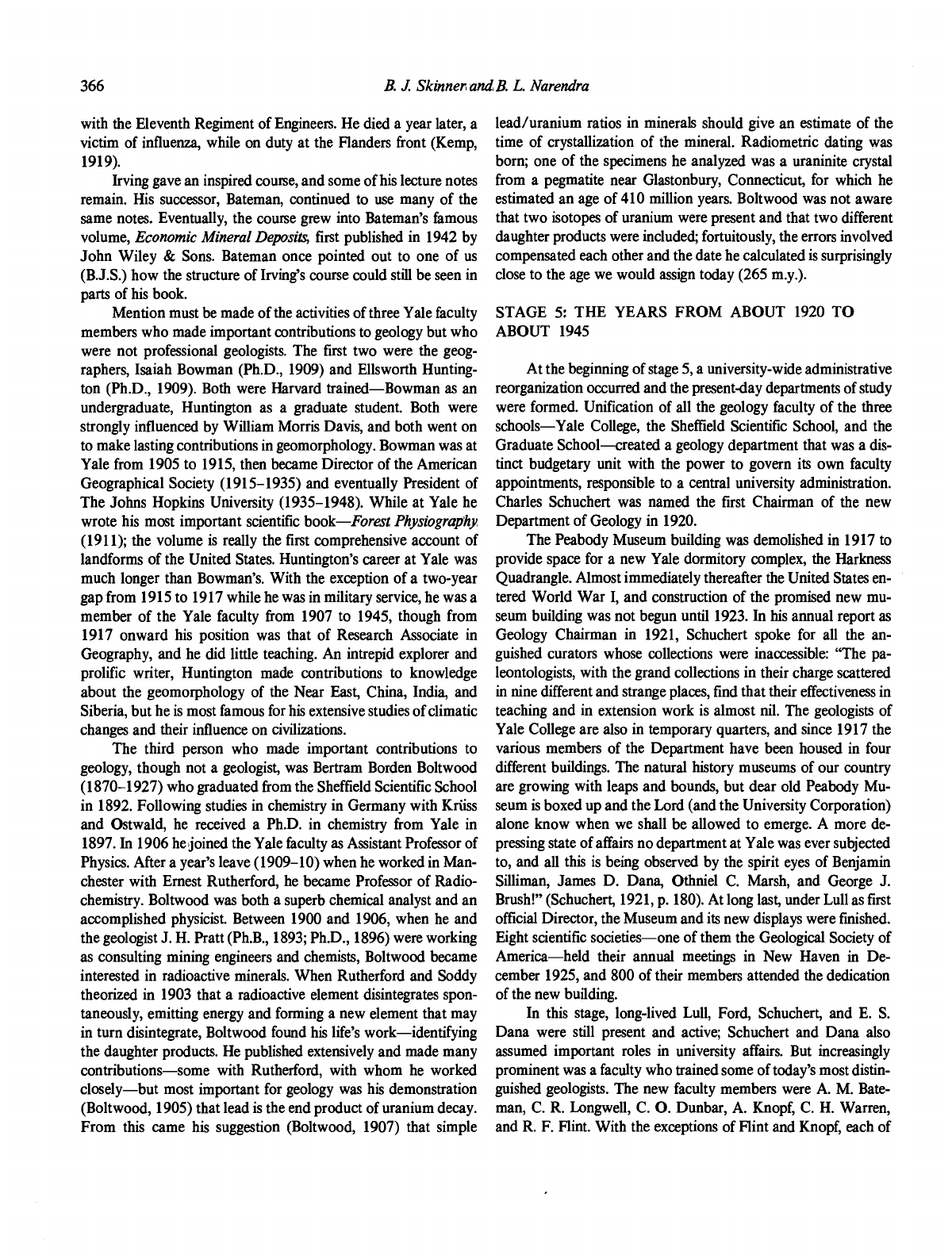

with the Eleventh Regiment of Engineers. He died a year later, a

victim of influenza, while on duty at the Flanders front (Kemp,

1919).

Irving gave an inspired course, and some of his lecture notes

remain. His successor, Bateman, continued to use many of the

same notes. Eventually, the course grew into Bateman's famous

volume, Economic Mineral Deposits, first published in 1942 by

John Wiley & Sons. Bateman once pointed out to one of us

(B.J.S.) how the structure of Irving's course could still be seen in

parts of his book.

Mention must be made of the activities of three Yale faculty

members who made important contributions to geology but who

were not professional geologists. The first two were the geog-

raphers, Isaiah Bowman (Ph.D., 1909) and Ellsworth Hunting-

ton (Ph.D., 1909). Both were Harvard trained—Bowman as an

undergraduate, Huntington as a graduate student. Both were

strongly influenced by William Morris Davis, and both went on

to make lasting contributions in geomorphology. Bowman was at

Yale from 1905 to 1915, then became Director of the American

Geographical Society (1915-1935) and eventually President of

The Johns Hopkins University (1935-1948). While at Yale he

wrote his most important scientific

book—Forest

Physiography

(1911);

the volume is really the first comprehensive account of

landforms of the United States. Huntington's career at Yale was

much longer than Bowman's. With the exception of a two-year

gap from 1915 to 1917 while he was in military service, he was a

member of the Yale faculty from 1907 to 1945, though from

1917 onward his position was that of Research Associate in

Geography, and he did little teaching. An intrepid explorer and

prolific writer, Huntington made contributions to knowledge

about the geomorphology of the Near East, China, India, and

Siberia, but he is most famous for his extensive studies of climatic

changes and their influence on civilizations.

The third person who made important contributions to

geology, though not a geologist, was Bertram Borden Boltwood

(1870-1927) who graduated from the Sheffield Scientific School

in 1892. Following studies in chemistry in Germany with Krtiss

and Ostwald, he received a Ph.D. in chemistry from Yale in

1897. In 1906 he joined the Yale faculty as Assistant Professor of

Physics. After a year's leave (1909-10) when he worked in Man-

chester with Ernest Rutherford, he became Professor of Radio-

chemistry. Boltwood was both a superb chemical analyst and an

accomplished physicist. Between 1900 and 1906, when he and

the geologist J. H. Pratt (Ph.B., 1893; Ph.D., 1896) were working

as consulting mining engineers and chemists, Boltwood became

interested in radioactive minerals. When Rutherford and Soddy

theorized in 1903 that a radioactive element disintegrates spon-

taneously, emitting energy and forming a new element that may

in turn disintegrate, Boltwood found his life's work—identifying

the daughter products. He published extensively and made many

contributions—some with Rutherford, with whom he worked

closely—but most important for geology was his demonstration

(Boltwood, 1905) that lead is the end product of uranium decay.

From this came his suggestion (Boltwood, 1907) that simple

lead/uranium ratios in minerals should give an estimate of the

time of crystallization of the mineral. Radiometric dating was

born; one of the specimens he analyzed was a uraninite crystal

from a pegmatite near Glastonbury, Connecticut, for which he

estimated an age of 410 million years. Boltwood was not aware

that two isotopes of uranium were present and that two different

daughter products were included; fortuitously, the errors involved

compensated each other and the date he calculated is surprisingly

close to the age we would assign today (265 m.y.).

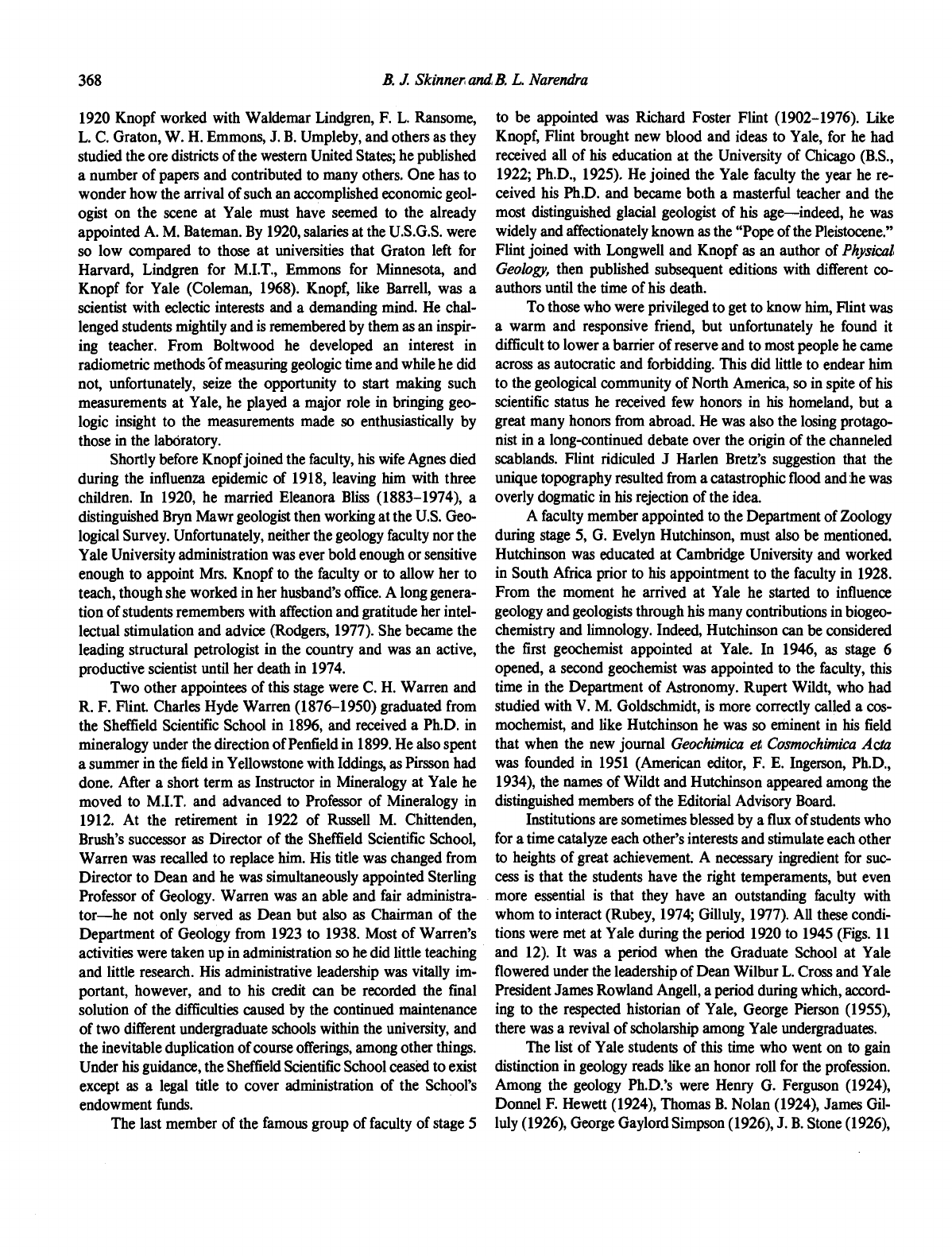

STAGE 5: THE YEARS FROM ABOUT 1920 TO

ABOUT 1945

At the beginning of stage 5, a university-wide administrative

reorganization occurred and the present-day departments of study

were formed. Unification of all the geology faculty of the three

schools—Yale College, the Sheffield Scientific School, and the

Graduate School—created a geology department that was a dis-

tinct budgetary unit with the power to govern its own faculty

appointments, responsible to a central university administration.

Charles Schuchert was named the first Chairman of the new

Department of Geology in 1920.

The Peabody Museum building was demolished in 1917 to

provide space for a new Yale dormitory complex, the Harkness

Quadrangle. Almost immediately thereafter the United States en-

tered World War I, and construction of the promised new mu-

seum building was not begun until 1923. In his annual report as

Geology Chairman in 1921, Schuchert spoke for all the an-

guished curators whose collections were inaccessible: "The pa-

leontologists, with the grand collections in their charge scattered

in nine different and strange places, find that their effectiveness in

teaching and in extension work is almost nil. The geologists of

Yale College are also in temporary quarters, and since 1917 the

various members of the Department have been housed in four

different buildings. The natural history museums of our country

are growing with leaps and bounds, but dear old Peabody Mu-

seum is boxed up and the Lord (and the University Corporation)

alone know when we shall be allowed to emerge. A more de-

pressing state of affairs no department at Yale was ever subjected

to,

and all this is being observed by the spirit eyes of Benjamin

Silliman, James D. Dana, Othniel C. Marsh, and George J.

Brush!" (Schuchert, 1921, p. 180). At long last, under Lull as first

official Director, the Museum and its new displays were finished.

Eight scientific societies—one of them the Geological Society of

America—held their annual meetings in New Haven in De-

cember 1925, and 800 of their members attended the dedication

of the new building.

In this stage, long-lived Lull, Ford, Schuchert, and E. S.

Dana were still present and active; Schuchert and Dana also

assumed important roles in university affairs. But increasingly

prominent was a faculty who trained some of today's most distin-

guished geologists. The new faculty members were A. M. Bate-

man,

C. R. Longwell, C. O. Dunbar, A.

Knopf,

C. H. Warren,

and R. F. Flint. With the exceptions of Flint and

Knopf,

each of

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

Rummaging

through

the attic

367

these appointees had received all or

a

major portion of his profes-

sional education

at

Yale,

lt

would seem that Yale found

it

diffi-

cult

to

look beyond

its own

graduates when

new

appointments

were

to be

made.

The first appointment

of

the

new era

actually occurred

be-

fore

1920.

Alan Mara Bateman (1889-1971)

was a

Canadian

who graduated from Queen's University

and had

already gained

a good deal

of

field experience when he arrived at Yale in 1910

to

study with Irving. During

the

summers

of 1911 and 1912 he

worked for the Geological Survey of Canada

on

the Fraser River,

British Columbia,

and

from this work came

his

thesis

on the

"Geology

and ore

deposits

of the

Bridge River district, British

Columbia,"

for

which

he

received a Ph.D.

in

1913. Bateman

was

then invited to join

the

famous Secondary Enrichment Investiga-

tion inspired by L.

C.

Graton, then at the U.S. Geological Survey,

which included members

of

academia, industry,

and the

Geo-

physical Laboratory.

The

work continued

for a

number

of

years

and

led to

many important papers—especially concerning

the

deposits

at

Kennecott, Alaska (White, 1974).

In 1915

Bateman

was appointed Instructor in Geology; when Irving left for military

training

in

1916, Bateman was appointed Assistant Professor.

He

continued to work at Yale until his death, rising through the ranks

and finally becoming

the

Silliman Professor

of

Geology

in 1941.

Following Bateman's appointment

and the

deaths

of

Pirs-

son,

Irving,

and

Barrell, there were three appointments

in 1920:

Longwell, Dunbar,

and

Knopf.

Chester

Ray

Longwell

(1887-1975) entered Yale

as a

graduate student

in 1915 but

service

in the U.S.

Army interrupted

his

studies,

and he did not

complete

his

thesis

on the

geology

of the

Muddy Mountains

of

Nevada until 1920.

He

was appointed

to the

Yale faculty

in the

same year

and

advanced steadily, becoming Professor

in 1929.

Longwell's main interest continued

to be

western geology, espe-

cially

the

western overthrust belt which

his

thesis

did

much

to

define. He was an excellent teacher and such major figures

in the

geological world

as W. W.

Rubey

and

James Gilluly were

among the graduate students he influenced.

He

was also an excel-

lent teacher

of

undergraduates

and

taught elementary physical

geology

at

Yale. Following Pirsson's death

he

inherited

the

physical geology portion

of

the Pirsson

and

Schuchert

Textbook

(1929),

which eventually became

the

famous Longwetl,

Knopf,

and Flint version

of Physical Geology

(1948).

The second appointee

of 1920 was

Carl Owen Dunbar

(1891-1979; Fig. 10), successor to Beecher and Schuchert. Dun-

bar studied geology

at

Kansas where

he

came under

the

strong

influence

of W. H.

Twenhofel (B.A.,

1908;

Ph.D., 1912),

who

was

a

great admirer

of

Schuchert

and

encouraged Dunbar

to do

graduate work under

him.

Dunbar received

his Ph.D. in 1917,

after which

he did a

year

of

postgraduate study with Schuchert

and then spent

two

years

as an

instructor

at the

University

of

Minnesota.

In

1920

he

returned as Assistant Professor

of

Histori-

cal Geology

and

Assistant Curator

of

Invertebrate Paleontology,

becoming Professor

of

Paleontology

and

Stratigraphy

in 1930.

Dunbar's broad professional interests centered

on the

fusuline

foraminifera

and

their

use in

stratigraphic correlation.

As a

Figure

10.

Carl

O.

Dunbar

and

John Rodgers.

A

photograph taken

in

1956.

(Courtesy

of

K.

M.

Waage).

teacher

he

was demanding and meticulous and

had a

great influ-

ence

on the

students

he

came

in

contact with—especially

the

graduate students.

He

also was an important textbook writer.

He

collaborated first with Schuchert

in

revision

of

the historical side

of

the Textbook of Geology

(Schuchert

and

Dunbar, 1933),

which he later rewrote as the highly influential

Historical Geology

(1949).

He

then revised this book again with

K. M.

Waage

(1969).

Perhaps even more influential

at the

graduate level

was

the book Dunbar co-authored with John Rodgers

in

1957,

Prin-

ciples of

Stratigraphy,

a

classic text that grew

out of a

jointly

taught course.

As

Director

of

the Peabody Museum

he

initiated

the construction

of the

museum's first dioramas. Probably

the

best known exhibit produced during

his

directorship

is the 110

foot-long Pulitzer Prize-winning mural,

"The Age of

Reptiles,"

painted

by

Rudolph Zallinger.

The third appointee

of 1920 was

Adolph Knopf

(1882-1966).

Knopf,

a

petrologist, was successor

to

Pirsson.

All

of

his

training

was at the

University

of

California

at

Berkeley

where

he was

strongly influenced

by the

teaching

of

Andrew

Lawson. Knopf received

a

B.S.

in

Mining Geology

in 1904 and

throughout

his

life made important contributions

to

economic

geology. First

and

foremost, however,

he was a

petrologist

and

field geologist. In 1905 he started working with

the

U.S. Geologi-

cal Survey

and

spent

six

field seasons

in

Alaska, during which

time (1909)

he

completed

his Ph.D.

thesis. Between

1910 and

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

368

B.

J.

Skinner and

B.

L. Narendra

1920 Knopf worked with Waldemar Lindgren, F. L. Ransome,

L.

C. Graton, W. H. Emmons, J. B. Umpleby, and others as they

studied the ore districts of the western United States; he published

a number of papers and contributed to many others. One has to

wonder how the arrival of such an accomplished economic geol-

ogist on the scene at Yale must have seemed to the already

appointed A. M. Bateman. By 1920, salaries at the U.S.G.S. were

so low compared to those at universities that Graton left for

Harvard, Lindgren for M.I.T., Emmons for Minnesota, and

Knopf for Yale (Coleman, 1968).

Knopf,

like Barrell, was a

scientist with eclectic interests and a demanding mind. He chal-

lenged students mightily and is remembered by them as an inspir-

ing teacher. From Boltwood he developed an interest in

radiometric methods of measuring geologic time and while he did

not, unfortunately, seize the opportunity to start making such

measurements at Yale, he played a major role in bringing geo-

logic insight to the measurements made so enthusiastically by

those in the laboratory.

Shortly before Knopf joined the faculty, his wife Agnes died

during the influenza epidemic of 1918, leaving him with three

children. In 1920, he married Eleanora Bliss (1883-1974), a

distinguished Bryn Mawr geologist then working at the U.S. Geo-

logical Survey. Unfortunately, neither the geology faculty nor the

Yale University administration was ever bold enough or sensitive

enough to appoint Mrs. Knopf to the faculty or to allow her to

teach, though she worked in her husband's office. A long genera-

tion of students remembers with affection and gratitude her intel-

lectual stimulation and advice (Rodgers, 1977). She became the

leading structural petrologist in the country and was an active,

productive scientist until her death in 1974.

Two other appointees of this stage were C. H. Warren and

R. F. Hint. Charles Hyde Warren (1876-1950) graduated from

the Sheffield Scientific School in 1896, and received a Ph.D. in

mineralogy under the direction of Penfield in 1899. He also spent

a summer in the field in Yellowstone with Iddings, as Pirsson had

done. After a short term as Instructor in Mineralogy at Yale he

moved to M.I.T. and advanced to Professor of Mineralogy in

1912.

At the retirement in 1922 of Russell M. Chittenden,

Brush's successor as Director of the Sheffield Scientific School,

Warren was recalled to replace him. His title was changed from

Director to Dean and he was simultaneously appointed Sterling

Professor of Geology. Warren was an able and fair administra-

tor—he not only served as Dean but also as Chairman of the

Department of Geology from 1923 to 1938. Most of Warren's

activities were taken up in administration so he did little teaching

and little research. His administrative leadership was vitally im-

portant, however, and to his credit can be recorded the final

solution of the difficulties caused by the continued maintenance

of two different undergraduate schools within the university, and

the inevitable duplication of course offerings, among other things.

Under his guidance, the Sheffield Scientific School ceased to exist

except as a legal title to cover administration of the School's

endowment funds.

The last member of the famous group of faculty of stage 5

to be appointed was Richard Foster Flint (1902-1976). Like

Knopf,

Flint brought new blood and ideas to Yale, for he had

received all of his education at the University of Chicago (B.S.,

1922;

Ph.D., 1925). He joined the Yale faculty the year he re-

ceived his Ph.D. and became both a masterful teacher and the

most distinguished glacial geologist of his age—indeed, he was

widely and affectionately known as the "Pope of the Pleistocene."

Flint joined with Longwell and Knopf as an author of Physical

Geology, then published subsequent editions with different co-

authors until the time of his death.

To those who were privileged to get to know him, Flint was

a warm and responsive friend, but unfortunately he found it

difficult to lower a barrier of reserve and to most people he came

across as autocratic and forbidding. This did little to endear him

to the geological community of North America, so in spite of his

scientific status he received few honors in his homeland, but a

great many honors from abroad. He was also the losing protago-

nist in a long-continued debate over the origin of the channeled

scablands. Flint ridiculed J Harlen Bretz's suggestion that the

unique topography resulted from a catastrophic flood and he was

overly dogmatic in his rejection of the idea.

A faculty member appointed to the Department of Zoology

during stage 5, G. Evelyn Hutchinson, must also be mentioned.

Hutchinson was educated at Cambridge University and worked

in South Africa prior to his appointment to the faculty in 1928.

From the moment he arrived at Yale he started to influence

geology and geologists through his many contributions in biogeo-

chemistry and limnology. Indeed, Hutchinson can be considered

the first geochemist appointed at Yale. In 1946, as stage 6

opened, a second geochemist was appointed to the faculty, this

time in the Department of Astronomy. Rupert Wildt, who had

studied with V. M. Goldschmidt, is more correctly called a cos-

mochemist, and like Hutchinson he was so eminent in his field

that when the new journal Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta

was founded in 1951 (American editor, F. E. Ingerson, Ph.D.,

1934),

the names of Wildt and Hutchinson appeared among the

distinguished members of the Editorial Advisory Board.

Institutions are sometimes blessed by a flux of students who

for a time catalyze each other's interests and stimulate each other

to heights of great achievement. A necessary ingredient for suc-

cess is that the students have the right temperaments, but even

more essential is that they have an outstanding faculty with

whom to interact (Rubey, 1974; Gilluly, 1977). All these condi-

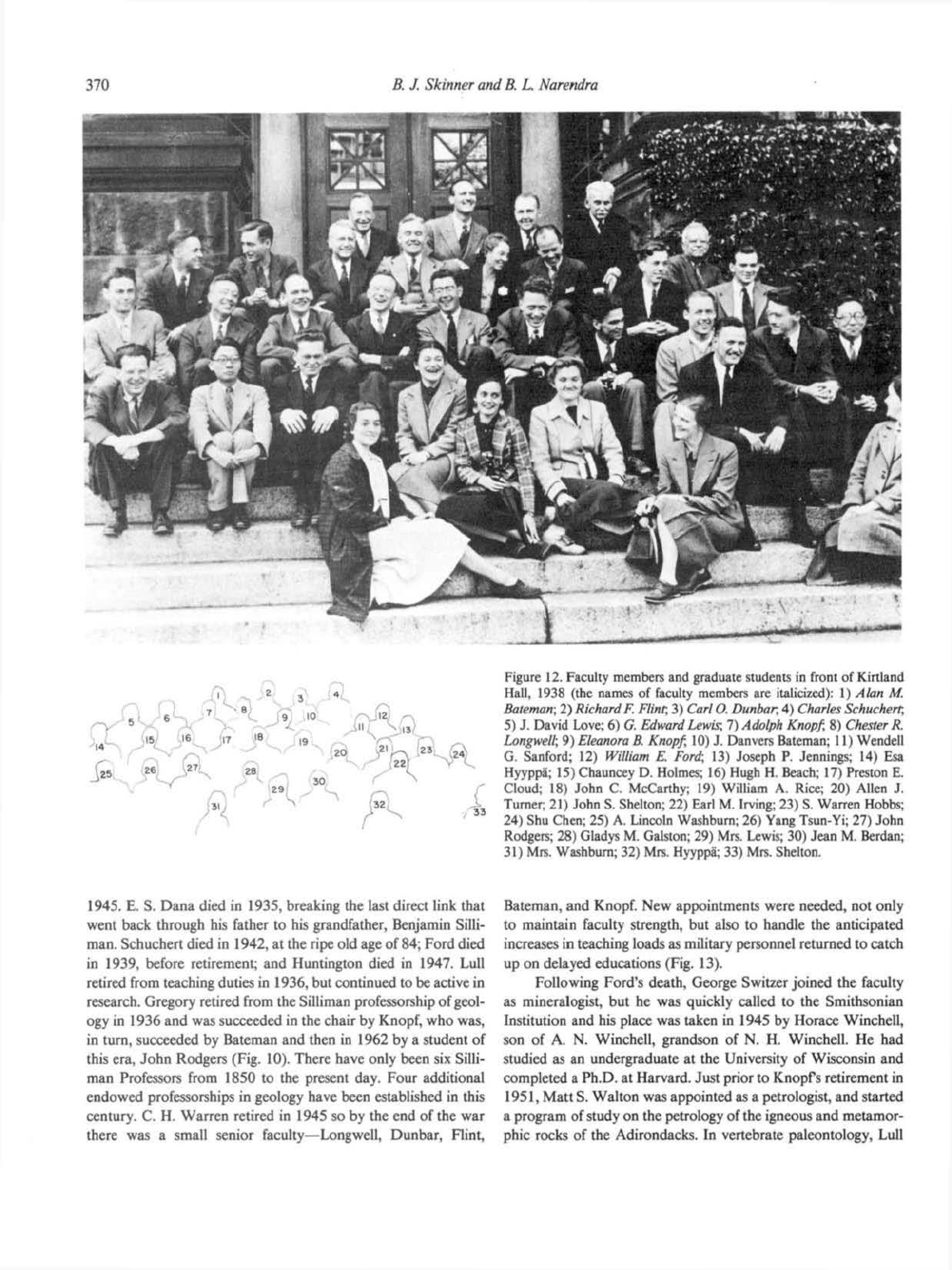

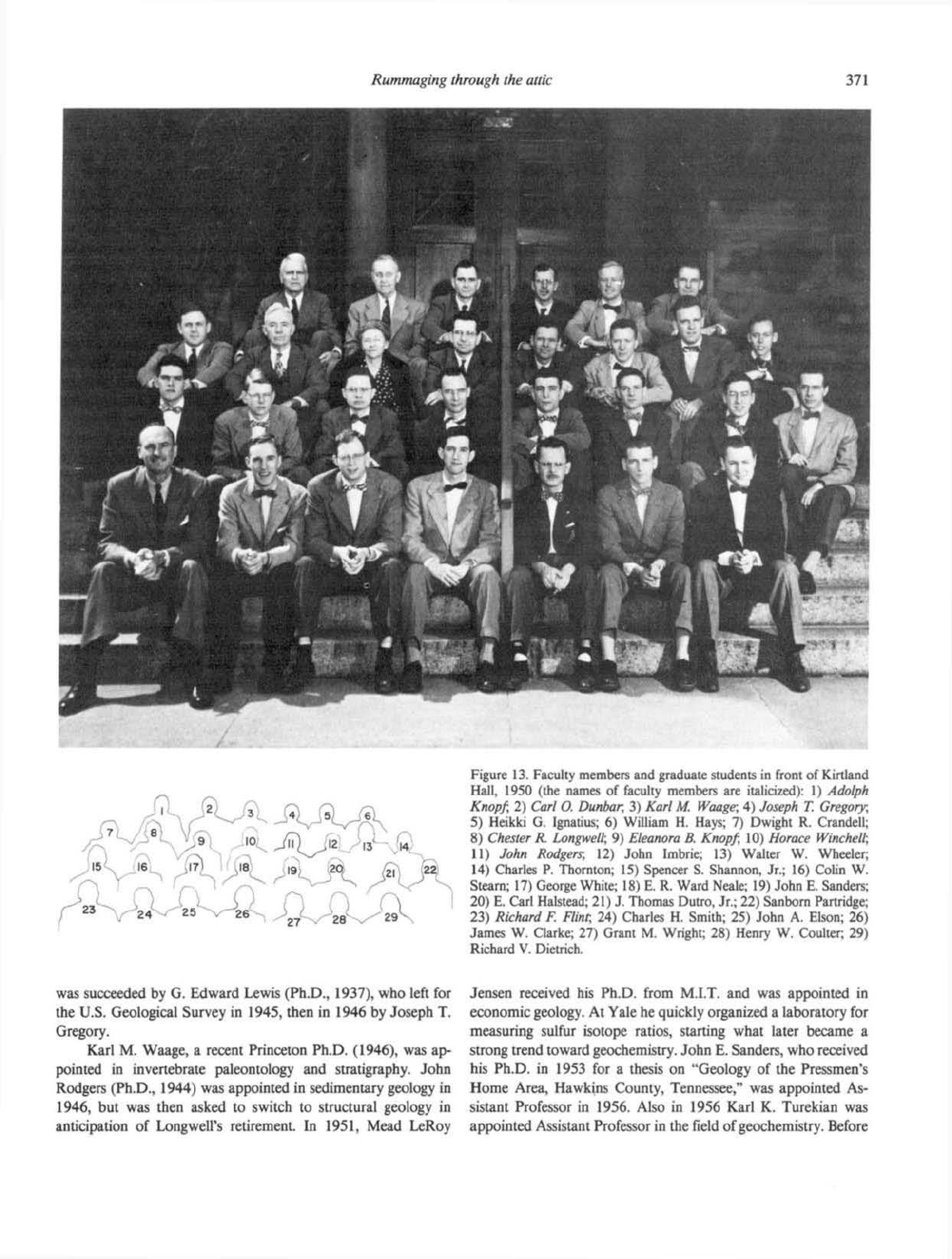

tions were met at Yale during the period 1920 to 1945 (Figs. 11

and 12). It was a period when the Graduate School at Yale

flowered under the leadership of Dean Wilbur L. Cross and Yale

President James Rowland Angell, a period during which, accord-

ing to the respected historian of Yale, George Pierson (1955),

there was a revival of scholarship among Yale undergraduates.

The list of Yale students of this time who went on to gain

distinction in geology reads like an honor roll for the profession.

Among the geology Ph.D.'s were Henry G. Ferguson (1924),

Donnel F. Hewett (1924), Thomas B. Nolan (1924), James Gil-

luly (1926), George Gaylord Simpson (1926), J. B. Stone (1926),

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3731786/9780813754130_ch24.pdf

by Yale University, ronald smith

on 07 February 2019

Rummaging through the attic

369

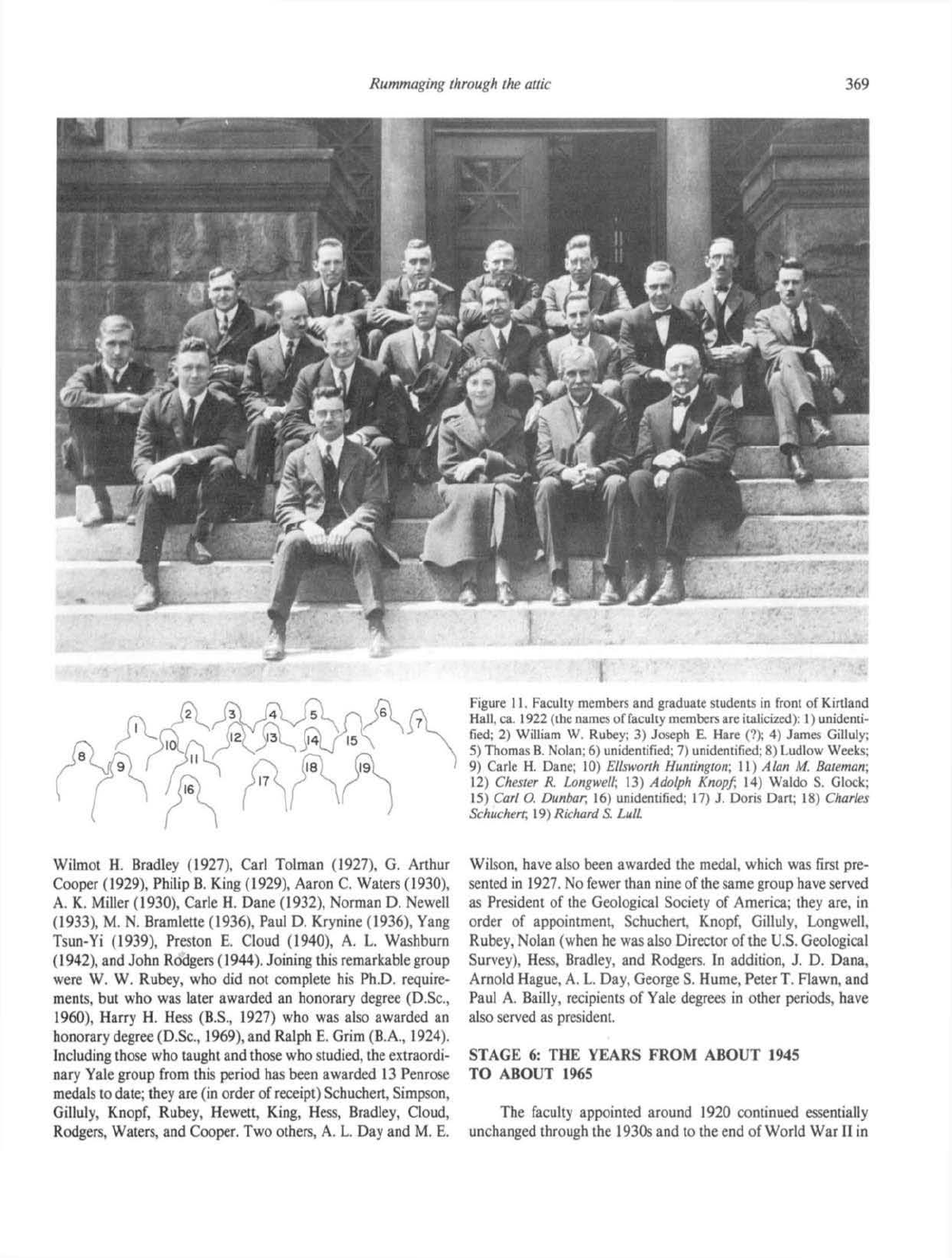

Figure 11. Faculty members and graduate students in front of Kirtland

Hall, ca. 1922 (the names of faculty members

arc

italicized): l)unidcnti-

fied; 2) William W. Rubey; 3) Joseph E. Hare (?); 4) James Gilluly;

5) Thomas

B.

Nolan;

6) unidentified; 7) unidentified; 8) Ludlow Weeks;

9) Carle H. Dane; 10) Ellsworth Huntington; 11) Alan M Bateman;

12) Chester R. Longwell; 13) Adolph

Knopf,

14) Waldo S. Glock;

15) Carl O. Dunbar, 16) unidentified; 17) J. Doris Dart; 18) Charles

Schuchen, 19) Richard

S.

Lull

Wilmot H. Bradley (1927), Carl Tolman (1927), G. Arthur

Cooper (1929), Philip B. King (1929), Aaron C. Waters (1930),

A. K. Miller (1930), Carle H. Dane (1932), Norman D. Newell

(1933),

M. N. Bramlette (1936), Paul D. Krynine (1936), Yang

Tsun-Yi (1939), Preston E. Cloud (1940), A. L. Washburn

(1942),

and John Rodgers (1944). Joining this remarkable group

were W. W. Rubey, who did not complete his Ph.D. require-

ments, but who was later awarded an honorary degree (D.Sc,

1960),

Harry H. Hess (B.S., 1927) who was also awarded an

honorary degree (D.Sc, 1969), and Ralph E. Grim (B.A., 1924).

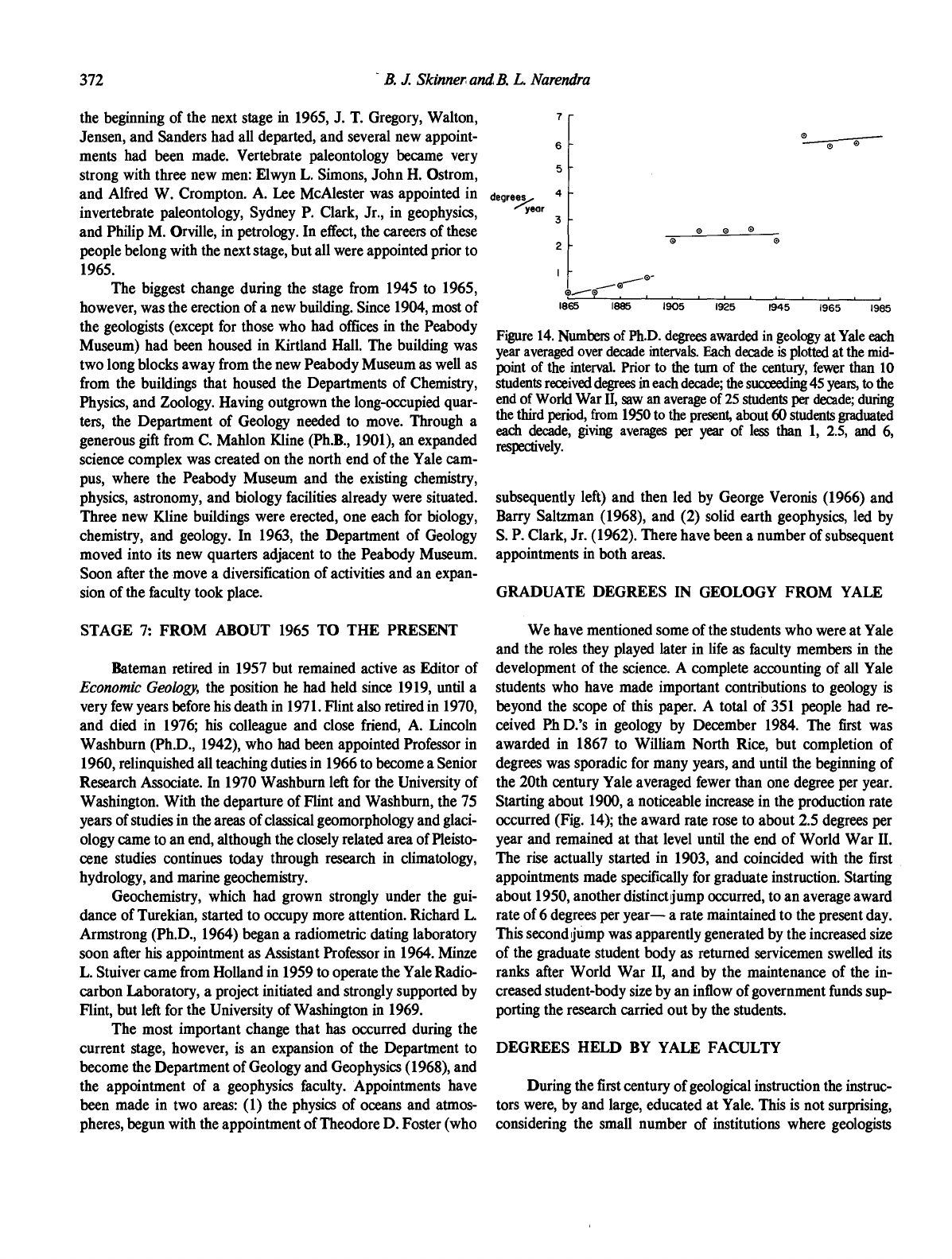

Including those who taught and those who studied, the extraordi-

nary Yale group from this period has been awarded 13 Penrose