WHAT HAPPENS

TO LOW–INCOME

HOUSING TAX CREDIT

PROPERTIES AT YEAR

15 AND BEYOND?

SUMMARY

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and Research

WHAT HAPPENS TO LOW–INCOME HOUSING TAX CREDIT PROPERTIES AT YEAR 15 AND BEYOND? SUMMARY WHAT HAPPENS TO LOW–INCOME HOUSING TAX CREDIT PROPERTIES AT YEAR 15 AND BEYOND? SUMMARY

2

e Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) Program has been

a signicant source of new multifamily housing for more than 20

years, providing more than 2.2 million units of aordable rental

housing. LIHTC units accounted for roughly one-third of all

multifamily rental housing constructed between 1987 and 2006.

As the LIHTC matures, however, thousands of properties nanced

using the program are becoming eligible to end the program’s

rent and income restrictions, prompting the U.S. Department

of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD’s) Oce of Policy

Development and Research (PD&R) to commission this study. In

the worst case scenario, more than a million LIHTC units could

leave the aordable housing stock by 2020, leading to a potentially

serious setback to eorts to provide housing for low-income

households.

is study suggests that the worst case scenario is unlikely to be

realized. Instead, the answer to the question of whether owners of

older LIHTC properties continue to provide aordable housing

for low-income renters is a qualied “yes.” Most LIHTC properties

remain aordable despite having passed the 15-year period of

compliance with Internal Revenue Service (IRS) use restrictions,

with a limited number of exceptions. ese exceptions are closely

related to the characteristics of the local housing market, as well as

to events that happen at Year 15 and are addressed in this report.

In answering this question and understanding its causes and

implications, this study focuses on properties that would have

reached Year 15 by 2009—properties placed in service under

LIHTC between 1987 and 1994. Over the course of this study,

interviews were conducted with industry participants: tax credit

syndicators, direct investors, brokers, owners, and Housing Finance

Agency (HFA) sta, as well as experts on multifamily nance and

the LIHTC program. Quantitative data, including property-level

records, HUD databases, and a survey conducted for this study of

rents of a sample of former LIHTC properties were analyzed.

e results of the analysis showed remarkably consistent impressions

of the outcomes for Year 15 properties:

• e vast majority of LIHTC properties continue to function

in much the same way they always have, providing aordable

housing at the same quality and rent levels to essentially

the same population, without major recapitalization. Some

rehabilitation of these properties occurred at or shortly after

Year 15, often in connection with a change of ownership or

renancing, but the amount of work done is not extensive

enough to be characterized as recapitalization.

• A moderate number of properties are recapitalized as

aordable housing funded by a new source of public subsidy,

typically a new round of tax credits, either at 4 or 9 percent.

ese properties underwent a substantial program of capital

improvements.

• e smallest group of properties were repositioned as market-

rate housing and ceased to operate as aordable. e risk of

such repositioning occurring is most likely in strong housing

markets.

WHAT HAPPENS AT YEAR 15?

Which of the three outcomes will be realized is linked to events

that happen at Year 15, including whether changes occur in the

property’s use restrictions, whether the property is sold to a new

ownership entity, and whether the property became nancially

or physically distressed before Year 15. e outcome may also be

aected by market conditions where a property is located.

CHANGE IN USE RESTRICTIONS

During the rst 15 years after a LIHTC property is placed in

service, owners must report annually on compliance with LIHTC

leasing requirements to both the IRS and the state monitoring

agency. After 15 years, the obligation to report to the IRS on

compliance issues ends, and investors are no longer at risk for

tax credit recapture. Beginning in 1990, however, federal law

required tax credit projects to remain aordable for the 15-year

initial compliance period plus a subsequent 15-year extended-use

period. Properties subject to an extended LIHTC use restriction

may seek to have that restriction removed. Using the Qualied

Contract (QC) process, owners may request regulatory relief from

use requirements any time after Year 15. In essence, the owner

requests the state agency to nd a buyer for the property, and the

state agency then has 1 year to nd a buyer who will maintain the

property as aordable housing. If the state is unsuccessful, then the

owner is entitled to be relieved of LIHTC aordability restrictions,

and those restrictions phase out over 3 years.

In practice, each state agency can dene its own regulations

for implementing a QC, so the process ranges from relatively

simple and straightforward to so complex and dicult—perhaps

intentionally—that the process is essentially unworkable. Further,

a number of states either require or persuade developers seeking

tax credits to waive their right to use the QC process in the future.

erefore, QC sales tend to be concentrated in a few states and are

not common.

CHANGE IN OWNERSHIP

A change in ownership for a LIHTC property can happen any

time. It is most likely to take place around Year 15, because it is in

the interest of limited partners (LPs) to end their ownership role

quickly after the compliance period ends. ey have used up the tax

credits by Year 10, and after Year 15 they no longer are at risk of IRS

penalties for failure to comply with program rules.

By far the most common pattern of ownership change around

Year 15 is for the LPs to sell their interests in the property to the

general partner (GP) (or its aliate or subsidiary) and for the GP to

continue to own and operate the property. is is overwhelmingly

the case for properties with nonprot developers but is also true in

many cases with for-prot developers. e minority of GPs who end

their ownership interest at Year 15 almost always do so by selling the

WHAT HAPPENS TO LOW–INCOME HOUSING TAX CREDIT PROPERTIES AT YEAR 15 AND BEYOND? SUMMARY WHAT HAPPENS TO LOW–INCOME HOUSING TAX CREDIT PROPERTIES AT YEAR 15 AND BEYOND? SUMMARY

3

property, almost always to a for-prot buyer. ese buyers may be

motivated by management fees, economies of scale, or the potential

for developer fees.

FINANCIAL DISTRESS AND CAPITAL NEEDS

Although the strong majority of LIHTC projects operate

successfully through at least their rst 15 years, some properties fall

into nancial distress. Poor property or asset management practices,

a problematic nancial structure, poor physical condition of the

property, and a soft rental market are the most common reasons for

the rare instances of failure.

Despite the fact that LIHTC properties tend to operate on tight

margins, the percentage of foreclosures is small, in the range of 1 to

2 percent. Owners are anxious to avoid foreclosure, because it would

be considered premature termination of the property’s aordability

and subject them to recapture of tax credits, with interest, and

forfeiture of all future tax credit benets from the property.

LIHTC properties are usually required to fund replacement reserves

annually to pay for capital repairs and renovations. ese reserves,

however, are usually insucient after 15 years to cover current needs

for renovation and upgrading. e most important determinant

of physical condition at Year 15 may be whether the property was

newly constructed or rehabilitated when it was placed in service,

and, if rehabilitated, the scope of the renovation work that was

done then. New construction and extensive rehabs are less likely

to need signicant upgrades at Year 15 than is a property which

received only moderate renovations when placed in service. Market

conditions may also aect property conditions over time. Properties

in strong markets are more likely to have high occupancy rates and

be rented at or near the maximum LIHTC rents and to generate

more operating funds that can be used for maintenance and repairs

than properties in weaker markets, and thus they enter Year 15 with

fewer deferred repair and maintenance needs.

OUTCOMES AFTER YEAR 15

After Year 15, properties take one of three paths: they remain

aordable without recapitalization, remain aordable with a major

new source of subsidy, or are repositioned as market-rate housing.

REMAIN AFFORDABLE WITHOUT

RECAPITALIZATION

All information gathered for this study shows that most LIHTC

properties that reached Year 15 through 2009 are still operating as

aordable housing, either with LIHTC restrictions in place or with

rents that nonetheless are at or below LIHTC maximum levels.

Even in the absence of use restrictions, at least two types of

properties will continue to provide aordable housing: those with

owners committed to long-term aordability (typically nonprot

owners, but also sometimes for-prot owners) and those located

where market rents are no higher than LIHTC rents.

is pattern of properties remaining aordable with their original

owners and without major recapitalization by Year 15 is common

in strong, weak, and moderate markets alike. Over the longer term,

however, developments are likely to fare quite dierently, depending

on the local market. For example, properties able to achieve high

occupancy levels and high rents—even if restricted to below-market

levels—can generate signicant cash ow and have real market

value. ese properties are more likely to eventually convert to

market rate and less likely to need new sources of subsidy to pay

for renovations.

REMAIN AFFORDABLE WITH NEW

SOURCES OF SUBSIDY

Some LIHTC properties are recapitalized as aordable housing

around Year 15 with a new allocation of tax credits. In addition to

receiving new tax credits, the property owner often renances the

mortgage, and acquires new soft debt. ese funds typically are

used to pay for renovation costs but sometimes also to acquire the

property from the original LIHTC owner.

When deciding whether to seek a new allocation of tax credits

to recapitalize a property—and accept a new period of use

restrictions—owners weigh a variety of factors. At a minimum, the

property must have some capital needs (at least $6,000 per unit) to

qualify for a new LIHTC allocation. Other factors include whether

the property needs to modernize to compete with new aordable

housing, whether an infusion of additional equity appears to be

the only way to bail out a distressed property, and whether new tax

credits and use restrictions aect protability.

State LIHTC policies also aect the decision to seek a new

allocation of tax credits. Some states reserve 9-percent LIHTCs for

aordable housing. Analysis of the HUD LIHTC database shows a

gradual rise in the second use of tax credits.

REPOSITIONED AS MARKET-RATE HOUSING

By far the least common outcome for LIHTC properties is

converting to market-rate housing after use restrictions have expired

or after a QC process or nancial failure. Foreclosure of the loan on

the property is followed by a property disposition by the lender to a

new owner who will operate the property as market-rate housing at

higher rents if the market will bear them.

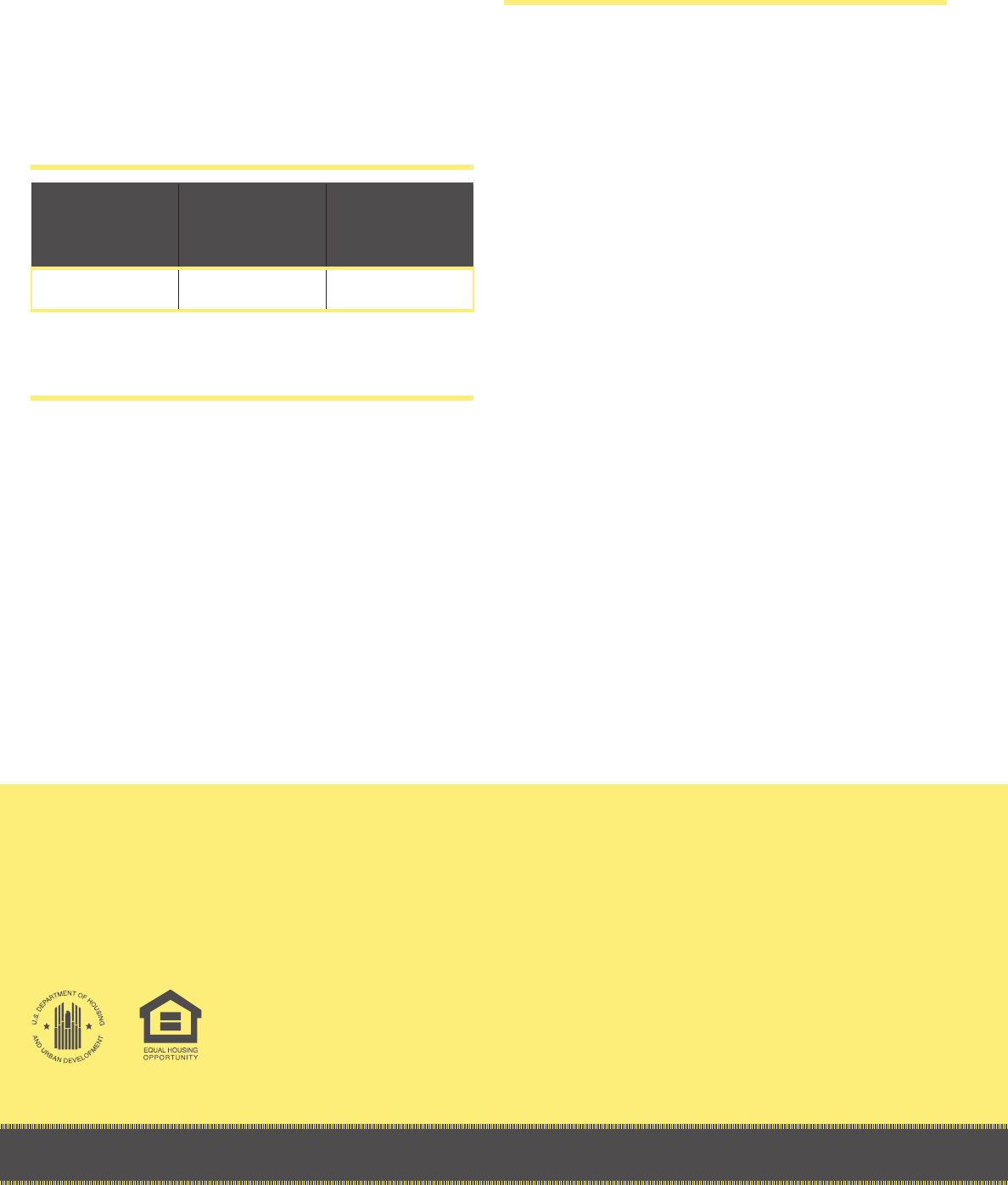

e most likely properties to have been repositioned as unaordable,

market-rate housing are those in low-poverty locations. e study

found through a survey of the rents of a sample of properties no

longer reporting to an HFA, that, even for this group of properties

that should be at particularly high risk of becoming unaordable,

WHAT HAPPENS TO LOW–INCOME HOUSING TAX CREDIT PROPERTIES AT YEAR 15 AND BEYOND? SUMMARY

4

nearly one-half had rents below the LIHTC maximum, and

another 9 percent had rents only slightly above LIHTC rents

(see exhibit below).

AFFORDABILITY OF PROPERTIES IN LOW-

POVERTY CENSUS TRACTS AND NO

LONGER MONITORED BY HOUSING

FINANCE AGENCIES

Property Rents Above

105 Percent of

LIHTC Rent

Property Rents Between

100 and 105 Percent of

LIHTC Rent

Property Rents

Below LIHTC Rent

42% 9% 49%

Source: HUD National LIHTC Database

LIHTC PROPERTIES AT YEAR 30

e properties studied have not yet reached year 30, when the

extended use restrictions for most of the properties will expire.

After Year 30, the three patterns observed at or somewhat after Year

15 are likely to continue, but with the balance shifting in favor of

the third pattern—repositioning and no longer aordable. Several

types of properties will almost certainly not be repositioned. ese

properties include those with a mission-driven owner, a location in

a state or city with use restrictions beyond Year 30, and the presence

of restrictions associated with nancing. Owners of the remaining

properties—non-mission driven owners of properties with no

use restrictions continuing beyond Year 30—are likely to make

a nancial calculation about what to do with the property that

depends on the housing market. e key consideration is whether

the location will support market rents substantially higher than

LIHTC rents.

CONCLUSIONS AND

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICYMAKERS

Most older LIHTC properties are not at risk of becoming

unaordable, the notable exceptions being properties with for-

prot owners in favorable market locations. Maintaining physical

asset quality turns out to be a larger policy issue for older LIHTC

properties than maintaining aordability. Older LIHTC properties

likely will follow one of three distinct paths: (1) some will maintain

their physical quality through cash ow and periodic renancing,

in much the same way that conventional multifamily real estate

does; (2) others will maintain their physical quality through

new allocations of LIHTC or another source of major public

subsidy; and (3) some properties will deteriorate over the second

15 years, with growing physical needs that ultimately will aect

their marketability and nancial health. An increasing number of

owners are expected to apply for new tax credit allocations, either at

9-percent or for bond nancing and 4-percent credits.

In the coming years, state HFAs will come under increasing

pressure as the large stock of LIHTC housing ages. Restricted by

nite resources, state policymakers will have to make choices. e

study results suggest that HFAs should place the highest priority on

the developments that are most likely to be repositioned to higher

market-rate rents.

In general, state policymakers should recognize that the majority

of older LIHTC properties will, over time, become mid-market

rental properties indistinguishable from other mid-market rental

housing, and that this is a good result. e report also suggests

that policymakers revise Qualied Allocation Plan standards to

encourage higher priorities for those properties that need additional

use restrictions to keep them from becoming unaordable and lower

priorities for properties in locations where low-income renters have

other alternatives.

VISIT PD&R’S WEBSITE WWW.HUD.GOV/POLICY OR WWW.HUDUSER.

ORG TO FIND THIS REPORT AND OTHERS SPONSORED BY HUD’S OFFICE OF

POLICY DEVELOPMENT AND RESEARCH (PD&R). OTHER SERVICES OF HUD

USER, PD&R’S RESEARCH AND INFORMATION SERVICE, INCLUDE LISTSERVS,

SPECIAL INTEREST AND BIMONTHLY PUBLICATIONS (BEST PRACTICES,

SIGNIFICANT STUDIES FROM OTHER SOURCES), ACCESS TO PUBLIC

USE DATABASES, AND A HOTLINE (1–800–245–2691) FOR HELP WITH

ACCESSING THE INFORMATION YOU NEED.

June 2012

REPORT PREPARED BY ABT ASSOCIATES